Abstract

There is a lack of knowledge and understanding of the term exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) among health professionals. The purpose of this review was to examine the best available literature on mothers' understanding of the term EBF. A systematic search of eight electronic databases (Medline, Embase, CINAHL, CDSR, CENTRAL, Cab Abstracts, Scopus and African Index Medicus) was conducted (Protocol registration in PROSPERO: CRD42015019402). All study designs were eligible for inclusion. Studies were included if they: (1) involved mothers aged 18 years or older; (2) assessed mothers' knowledge/understanding/awareness of the term ‘EBF’; (3) used the 1991 WHO definition of EBF and (4) were published between 1988 and 2015. Two reviewers retrieved articles, assessed study quality and performed data extraction. Of the 1700 articles identified, 21 articles met the inclusion criteria. Quantitative findings were pooled to calculate a proportion rate of 70.9% of mothers who could correctly define EBF, although the range varied between 3.1 and 100%. Qualitative findings revealed three themes: (1) EBF was understood by mothers as not mixing two milks; (2) the term ‘exclusive’ in EBF was incorrectly understood as not giving breast milk and (3) mothers believing that water can be given while exclusively breastfeeding. Research investigating aspects of self‐reported EBF may consequently be unreliable. A standardised tool to assess mothers' knowledge of EBF could provide more accurate data. Public health campaigns should emphasise EBF to target mothers, while addressing the education of health professionals to ensure that they do not provide conflicting advice.

Keywords: exclusive breastfeeding, mothers, knowledge, awareness, understanding

Introduction

The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) as when ‘an infant receives only breast milk, no other liquids or solids are given – not even water, with the exception of oral rehydration solution, or drops/syrups of vitamins, minerals or medicines’ (World Health Organization 2016). Despite the well‐recognised benefits, EBF prevalence is poor worldwide; with the Global Nutrition Report indicating the global baseline EBF rate was 38% between 2008 and 2012 (Global Nutrition Report, 2015 2015). In low and middle‐income countries (LMIC), less than 40% of infants younger than six months of age are estimated to be exclusively breastfed (WHO, 2016). This is a concern considering that EBF is especially important in LMIC where poverty, under nutrition and disease burden are common because of limited resources and economic, environmental and cultural influences (Caulfield et al. 2006). There is evidence to suggest that in high‐income counties (HIC) the risk of acute respiratory infections and diarrhoea is also substantially reduced when an infant is breastfed exclusively (Wright et al. 1989; Ip et al. 2007). In spite of this, EBF prevalence varies globally with statistics in some HIC estimated to be 11.3% and as low as 1% (Centers For Disease Control And Prevention (CDC) 2007; World Health Organization 2014).

According to two recent collaborative reviews (Ip et al. 2007; Kramer and Kakuma, 2009), the definitions of EBF were found to be considerably different across all included studies, with the majority failing to differentiate between infants exclusively breastfed and infants partially breastfed. One study incorporated non‐nutritive supplements, such as water, sugar and herbal teas in their definition of EBF (Okolo et al. 1999). However even the minimal use of supplements has been shown to have an increased risk of gastrointestinal infections and mortality in infants (Arifeen et al. 2001; Kramer and Kakuma, 2004).

There is also a lack of knowledge and understanding of the term EBF among health professionals (Chopra et al. 2002; Shah et al. 2005; Taneja et al. 2005; Piwoz et al. 2006; Marais et al. 2010; Laanterä et al. 2011; Du Plessis & Pereira 2013) because of an apparent lack of consistency of definitions of breastfeeding terms (Labbok & Krasovec 1990). Considering that health professionals provide new mothers with breastfeeding information (Lewallen et al. 2006), if health professionals do not fully understand the meaning of EBF, they may subsequently communicate, confusing, mixed messages to mothers.

Although much research has investigated health professionals' knowledge and understanding of infant feeding practices (Mcintyre & Lawlor‐smith 1996; Chen et al. 2001; Chopra et al. 2002; Shah et al. 2005; Taneja et al. 2005; Piwoz et al. 2006; Tennant et al. 2006; Marais et al. 2010; Zakarija‐Grković & Burmaz 2010; Laanterä et al. 2011), there is limited research on mothers' understanding of EBF. To the authors' knowledge, no systematic review has examined mothers' understanding of the term EBF. Therefore, a systematic review was conducted to address this gap in the research with the aim to systematically evaluate the best available literature on mothers' understanding of the term EBF.

Key messages.

There are misconceptions among mothers about EBF, which has implications for interpreting findings from current research and for reporting on EBF practices and policy making.

In‐depth questioning on EBF should therefore be stressed in field‐research to ensure good quality data on EBF.

The WHO EBF indicator lacks sensitivity therefore overestimating the proportion of exclusively breastfed infants.

The questionnaire suggested to calculate the WHO indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices could be used as a starting point to develop a validated tool for assessing EBF practices.

Methods

The systematic review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) checklist (PRISMA, 2009). Preliminary literature searches within three databases (Medline, Embase and Google Scholar) were conducted in March 2015 to provide an initial overview of the literature and to aid with developing the overall search strategy. The systematic review protocol was registered in PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42015019402). The protocol can be accessed at: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/register_new_review.asp?RecordID=19402&UserID=11187.

Search strategy

A systematic search of published literature was conducted in March 2015 using key search terms (Table 1) within eight electronic scientific databases including: Medline, Embase, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Cab Abstracts, Scopus and African Index Medicus. No language restrictions were imposed. The reference lists of included studies were hand searched and experts in the relevant field were contacted to identify any additional relevant papers not identified in the database search.

Table 1.

Full list of search terms used in the database search strategy

| Participants | Outcome | Breastfeeding | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers | Knowledge | Breastfeeding | ||

| OR | AND | OR | AND | OR |

| ‘m#m’.tw. | Understanding | ‘Breastfeeding’.tw. | ||

| OR | ||||

| Awareness | ||||

| OR | ||||

| ‘Definition’.tw. |

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The review examined studies that: (1) involved mothers aged 18 years or older; (2) assessed mothers' knowledge/understanding/awareness of the term EBF; (3) used the 2001 WHO definition of EBF (WHO, 1991) and (4) were published between March 1988 and March 2015. The cut‐off year of March 1988 was selected as it was at this date that the term EBF originated (Labbok & Krasovec 1990). Studies were excluded if they: (1) reported on health care professionals' knowledge/understanding of the term EBF; (2) assessed any other type of definition of EBF or where EBF was not clearly defined; (3) reported on breastfeeding alone and not EBF and (4) reported findings in a thesis, dissertation, book, conference abstract or unpublished literature.

Two independent reviewers (RS and DM/JH) reviewed the title and abstract of each article for relevance against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The full texts of potentially eligible articles were retrieved and independently assessed by the two reviewers to determine eligibility. Any disagreements for an article's inclusion were resolved through discussion between the two reviewers and if a consensus could not be reached, a third reviewer was consulted (DM/JH). Additional data were requested from study authors if it would determine study eligibility.

Quality appraisal

Two reviewers (RS and DM/JH) independently assessed the study quality of each included study using an 11‐item standardised quality appraisal tool (see Supporting information: Appendix 1) (Guyatt et al. 1993a,1993b). The quality appraisal tool assessed risk of bias and study quality in regards to the study aims, recruitment, participant description, measurement outcomes, data collection, and results and data analysis. Each domain was coded as either a tick for being clearly present, a ‘U’ for unclear and a cross for absent. Any difference in ratings was resolved through discussion between the two reviewers, or a third reviewer was consulted if a consensus could not be reached. Each domain was considered independently as recommended by the PRISMA (PRISMA, 2009).

Data extraction

Two independent reviewers (RS and DM/JH) performed data extraction using an adapted data extraction form created from a standardised tool from the Cochrane Collaboration for Randomised Controlled Trials (The Cochrane Collaboration 2015). The two reviewers discussed any discrepancies and consulted a third reviewer (DM/JH) if a consensus could not be reached. The extracted data provided details on: author details (name, date, year), the study methods (aims, inclusion criteria, assessment measures i.e. questionnaires), participants (number, age of mother, age of infants, socio‐economic status, marital status, educational and employment status, breastfeeding status and health status), description of the setting (country, setting i.e. clinic/hospital based), drop‐out rates where applicable, study findings, limitations of the study and authors' conclusions.

Data synthesis

For quantitative studies, characteristics and findings were synthesised narratively, summaries were presented as percentage of mothers who understood EBF and a pooled proportion rate was calculated. For qualitative studies, thematic analysis was conducted by identifying common themes from the results reported and according to the primary outcomes of the research. Common themes were clustered and categorised into three themes which related to misunderstanding of the term ‘EBF’.

Results

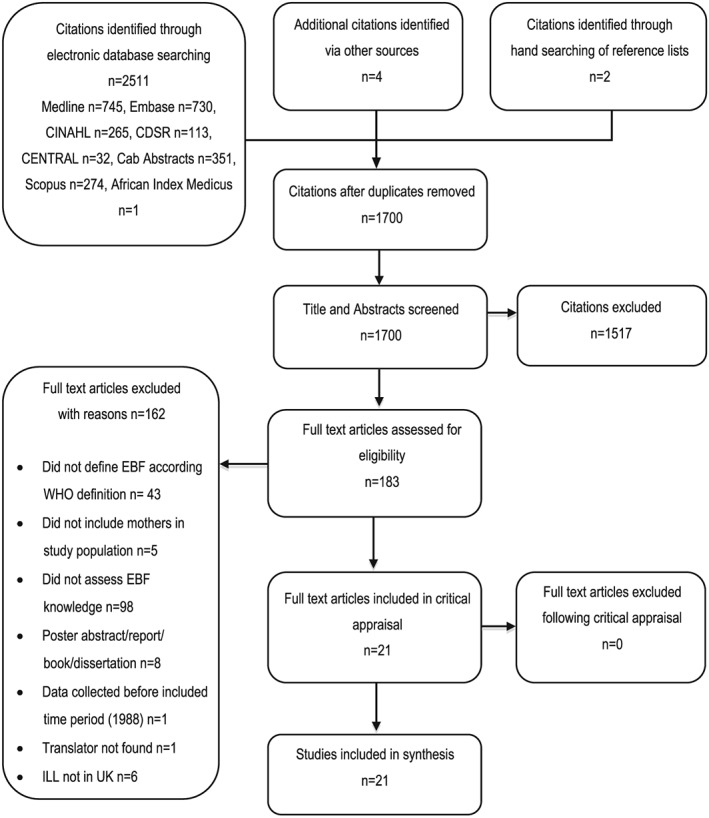

The initial database search, hand search and additional sources search yielded 1700 articles after duplicates had been removed (Fig. 1). Articles not complying with the inclusion criteria were excluded during the title and abstract screening phase (n = 1517). Full texts were retrieved for the remaining 183 citations, of which 162 were excluded primarily as they did not use the WHO EBF definition (WHO, 1991) or did not assess mothers' knowledge of the definition of EBF. In total, 21 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review.

Figure 1.

Method of determining studies to be included in the review. CINAHL = Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; CDSR = Cochrane Register of Systematic Reviews; CENTRAL = Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials; ILL = Inter Library Loans.

Characteristics of included studies

The majority of included studies were cross‐sectional in nature (n = 13) (Ogbonna & Daboer 2007; Petrie et al. 2008; Uchendu et al. 2009; Marais et al. 2010; Ukegbu & Ukegbu 2010; Oche et al. 2011; Abul‐Fadl et al. 2012; Alade et al. 2013; Ukegbu & Anyikaelekeh 2013; Adeyemi & Oyewole 2014; Danso 2014; Desai et al. 2014; Onah et al. 2014) with the remainder of studies either qualitative (n = 7) (Murray et al. 2008; Otoo et al. 2009; Nankunda et al. 2010; Ostergaard & Bula 2010; Ukegbu et al. 2011; Nor et al. 2012; Nduna et al. 2015) or a Randomised Control Trial (RCT) (n = 1) (Aksu et al. 2011) (Table 2). Publication dates ranged from 2007 (Ogbonna & Daboer 2007) to 2015 (Nduna et al. 2015). All studies were conducted in low and middle‐income countries (LMIC) (n = 21), predominantly in Africa (n = 19). A large number of studies were carried out in Nigeria (n = 9) (Ogbonna & Daboer 2007; Uchendu et al. 2009; Ukegbu & Ukegbu 2010; Oche et al. 2011; Ukegbu et al. 2011; Alade et al. 2013; Ukegbu & Anyikaelekeh 2013; Adeyemi & Oyewole 2014; Onah et al. 2014).

Table 2.

Characteristics of studies included in the review (n = 21)

| Study ref (study type; year data collected) | Setting | Country | Population | Study aim | Method | Drop out rate | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abul‐Fadl et al. 2012 (Cross sectional; 2008) | Clinic based | Egypt | 1052 mothers, 61.7% urban, 30.2% rural, 8.1% slum. 53% ≥ 9 years education, 34.2% no/little education. 62.2% housewives, 37.8% employed. Infants aged 6–24 months, currently breastfeeding. | To evaluate the knowledge, attitudes and practice of Egyptian mothers towards the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding. | Questionnaires and interviews | N/A | Study limited to convenience sampling method. |

| Adeyemi & Oyewole 2014 (Cross sectional; 2006) | Clinic based | Nigeria | 62 mothers (demographics not available as they were not separated for the mothers who defined EBF). | To furnish information that could be used to improve the delivery of nutrition education to mothers of young children attending a primary health care centre. | Pre‐tested semi‐structured self administered questionnaire | N/A | Possible reporting bias for BF practices. |

| Aksu et al. 2011 (RCT; 2008) | Hospital based | Turkey | 30 mothers (control group) mean age 23 ± 4.6 years. 43.3% primary education or less, 43.3% secondary education, 13.3% university graduates. 205 employed, 80% unemployed. Vaginal birth of 1 healthy infant born at 37 or > weeks. Aydin Resident, Turkish speaking. No drugs which may affect BM. Intention to BF, no history of chronic disease, non‐smoker. | To determine the effects of breastfeeding education/support offered at home on day 3 postpartum on breastfeeding duration and knowledge. | Questionnaires | 0% | Intervention was not blinded for those obtaining the outcomes. Small sample size. |

| Alade et al. 2013 (Cross sectional; N/R) | Household based | Nigeria | 410 mothers, mean age 27.4 years (range 13–49 years). Lactating with infants < 6 months 95.4% married, 59.3% Muslim; 94.9% Yoruba; 35.4% had only completed primary education; 39.5% were traders and 24.1% farmers, 3.9 % civil servants. | To investigate the antecedent factors for EBF among lactating mothers in Ayete, south‐east Nigeria. | Pre‐tested semi‐structured questionnaire (including a 14 point knowledge scale) | N/A | Low generalisability |

| Danso 2014 (Cross sectional: N/R) | Community based | Ghana | 1000 Professional working mothers aged 20–40 yrs, 71% aged 36–35 years, full time employment and high educational attainment. Infants 6–24 months. | To examine the practice of EBF among professional working mothers in Ghana. | Questionnaires | N/A | Did not state how question was asked/assessed, low generalisability to mothers not in full‐time employment, unsure if questionnaire is valid/reliable or was pre‐tested, did not state response rate. |

| Desai et al. 2014 (Cross sectional; 2011) | Clinic based | Zimbabwe | 295 mothers, mean age 26.1 ± 8.5 yrs, mean education 9.6 ± 1.9 years. 19.2% HIV +ve, 76.3 HIV −ve, 4.5% unknown HIV status. Infants <6 months. | To uncover barriers to breastfeeding exclusivity. | Survey questionnaire | N/A | Not representative as sample obtained from immunisation services. |

| Marais et al. 2010 (Cross sectional; 2005) | Clinic based | South Africa | 64 mothers, English/Afrikaans speaking. Infants < 6 months attending clinic ≥2 times, currently breastfeeding. | To investigate knowledge levels and the attitudes of health care workers and mothers alike and practices inhibiting the continuation of EBF by mothers attending private BF clinics. | Quantitative – Interviewer– administered questionnaires. | 49% | High subject attrition. Reasons for non‐participating subjects not determined therefore may bias results – related to non‐compliance to the 10‐steps. BF clinics from 1 private hospital group therefore not representative. |

| Murray et al. 2008 (Qualitative; NR) | Clinic based | South Africa | 89 Mothers with infants < 6 months. Afrikaans, English, Xhosa speaking. 52 from urban, 37 from rural. | To determine the comprehensibility of the preliminary PFBDG for infants younger than 6 months. | 20 × FGD | N/A | Convenience sampling – not representative |

| Nankunda et al. 2010 (Qualitative; 2005–2006) | Community based | Uganda | 11 mothers aged 18–45 years (mean 34 yrs) resident, good reputation within community, literate and numerate in local language, attained ≥ 7 years formal education, personal BF experience. | To describe the experience of establishing individual peer counselling including training and retaining peer counsellors for EBF in the Uganda site of the Promoting Infant Health and Nutrition in Sub‐Saharan Africa. | Questionnaires | N/A | No control group. Small sample size. Not realistic for population. No blinding – the training team also performed the evaluation. |

| Nduna et al. 2015 (Qualitative; N/R) | Community based | Zimbabwe | 10 mothers. Breastfeeding experience and breastfed ≥ 2 children. | To describe factors that enable and hinder EBF in a rural district of Zimbabwe based on mothers' own lived breastfeeding experiences. | Interviews | N/R | Small sample size. Low generalisability. |

| Nor et al. 2012 (Qualitative; 2006) | Community based | South Africa | 17 mothers, mean age 24 years, 7 HIV +ve, 9 HIV −ve, 1 unknown HIV status. | To explore mothers' perceptions and experiences of infant feeding within a community based peer‐counselling intervention promoting exclusive breast or formula feeding. | Qualitative – semi‐structured interviews | N/A | Research quality dependent on the individual skills of researcher and possibly more easily influenced by researcher's personal biases. |

| Oche et al. 2011 (Cross sectional; N/R) | Community based | Nigeria | 179 Mothers, semi‐urban, mean age 29 ± 10.3 yrs, 34% formal education, 5% tertiary education, 61% housewives, 12% civil servants. Breastfeeding or stopped BF ≤2 years. | To gather information about the knowledge and others factors that influence the practice of EBF in Kware, Nigeria. | Pre‐tested structured interview‐administered questionnaire | N/A | Did not explore other cultural determinants of BF, which may have had influence on EBF. A score of >50% was graded as adequate knowledge of EBF. |

| Ogbonna & Daboer 2007 (Cross sectional; N/R) | Household based | Nigeria | 470 mothers, mean age 27.5 ± 5.1 yrs. 47.2% secondary education, 21.3 tertiary. 40% housewives, 28.1% traders. Infants 6–12 months. | To determine the current level of knowledge and practice of nursing mothers on EBF and the factors that influence them. | Pre‐tested structured interview‐administered questionnaire | N/A | Did not state how question was asked/assessed, low generalisability. |

| Onah et al. 2014 (Cross sectional; 2012) | Clinic based | Nigeria | 400 mothers, lower SES, no more than secondary education, with healthy infants ≤ 6 months. | To describe the feeding practices of infants below months of age and determine maternal and socio‐demographic factors that influences the practice of EBF among mothers in South‐east Nigeria. | Pre‐tested interviewer administered questionnaire | N/A | May be subjective to recall bias and miss reporting by participants and interviewers. |

| Ostergaard & Bula 2010 (Qualitative; 2008–2009) | Hospital and clinic based | Malawi | 21 mothers aged 18–40 yrs with infants 7–12 months. Intention to practice EBF for 6 months. | To explore the challenges which HIV positive women in Malawi face when they have to decide how to feed their infants. | Individual in‐depth interviews and observation | N/A | Low generalisability |

| Otoo et al. 2009 (Qualitative; 2006) | Clinic based | Ghana | 35 mothers aged 19–49, 7.2 ± 3.6 yrs formal education, with infants' ≤ 4 months. 32 employed, 3 unemployed, 17 were traders. | To explore Ghanaian women's knowledge and attitudes toward EBF. | 4 × FGD | N/A | FGDs conducted in peri‐urban community so results may vary from mothers in rural and urban communities. Low generalisability |

| Petrie et al. 2008 (Cross sectional; 2004) | Clinic based | South Africa | 36 mothers. 30.6 % < 25 years, 22.2% 25–29 years, 47.2% > 30 years (18–39 age range). 55.6% < 6 months postpartum 44.4 5 pregnant. 63.9% unemployed. 47.2% education level between grades 11 and 12, 8.3% reported no education, 8.3% tertiary education. | To determine the knowledge, attitudes and practices of women regarding the PMTCT programmes at Vangaurd Community Health Centre. | Questionnaires | N/R | Low generalisability |

| Uchendu et al. 2009 (Cross sectional; 2006) | Clinic based | Nigeria | 184 mothers. Infants ≥6 months, born after 1992 in hospital where EBF promoted. | To evaluate mothers' perceptions of EBF and determine the relationship between such views and their practices. | Structured questionnaires | 8% | Low generalisability |

| Ukegbu & Ukegbu 2010 (Cross sectional; N/R) | Community based | Nigeria | 353 rural mothers, 34.3% aged 20–24, 28.5% aged 30–34, 2.27% aged 35–39 years. 67% secondary education, 35.8% farmers, 30.1% housewives, 9.7% traders. Currently breastfeeding. | To determine the knowledge, attitude and practice of breastfeeding and identify factors associated with introduction of others foods within the first 6 months of life. | Pre‐tested questionnaire | N/A | Did not state how question was asked/assessed, low generalisability. |

| Ukegbu et al. 2011 (Qualitative; 2006–2007) | Clinic based | Nigeria | 35 mothers | To identify the factors influencing breastfeeding practices among mothers in Anambra State, Nigeria. | 4 × FGD | N/R | No description of inclusion criteria. |

| Ukegbu & Anyikaelekeh 2013 (Cross sectional; N/R) | Clinic based | Nigeria | 240 urban mothers, 71.3% aged 26–35, 7.9% primary education, 42.9% secondary, 49.2% tertiary, 37.5% employed in civil service, 21.7% housewives. Vaginal delivery of healthy full term babies' ≥2.5 kg. | To assess knowledge, attitude and practice of EBF and maternal factors associated with its practice in an urban area in southeast Nigeria. | Questionnaires | 9.40% | Sample size not equal to sample size initially calculated therefore inability to generalise data. |

N/R = not reported; N/A = not applicable; EBF = exclusive breastfeeding; BF = breastfeeding; FGD = focus group discussions; PFBDG = Paediatric food based dietary guidelines; PMTCT = prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission.

The number of participants in the studies ranged from 10 (Nduna et al. 2015) to 1052 (Abul‐Fadl et al. 2012). The studies included mothers who had infants between zero and 24 months old (n = 12) (Ogbonna & Daboer 2007; Murray et al. 2008; Petrie et al. 2008; Otoo et al. 2009; Uchendu et al. 2009; Marais et al. 2010; Ostergaard & Bula 2010; Abul‐Fadl et al. 2012; Alade et al. 2013; Danso 2014; Desai et al. 2014; Onah et al. 2014), and the age of infants was not mentioned in nine studies (Nankunda et al. 2010; Ukegbu & Ukegbu 2010; Aksu et al. 2011; Oche et al. 2011; Ukegbu et al. 2011; Nor et al. 2012; Ukegbu & Anyikaelekeh 2013; Adeyemi & Oyewole 2014; Nduna et al. 2015). Two studies (Ostergaard & Bula 2010; Aksu et al. 2011) included mothers who intended to breastfeed, five (Marais et al. 2010; Ukegbu & Ukegbu 2010; Oche et al. 2011; Abul‐Fadl et al. 2012; Alade et al. 2013) who were currently breastfeeding and two (Nankunda et al. 2010; Danso 2014) with personal breastfeeding experience. Twelve studies (Ogbonna & Daboer 2007; Murray et al. 2008; Petrie et al. 2008; Otoo et al. 2009; Uchendu et al. 2009; Ukegbu et al. 2011; Nor et al. 2012; Ukegbu & Anyikaelekeh 2013; Adeyemi & Oyewole 2014; Desai et al. 2014; Onah et al. 2014; Nduna et al. 2015) did not mention current breastfeeding status.

In five studies (Ogbonna & Daboer 2007; Ukegbu & Ukegbu 2010; Oche et al. 2011; Abul‐Fadl et al. 2012; Ukegbu & Anyikaelekeh 2013) the majority of mothers worked as housewives, and six studies also indicated mothers worked as traders (Ogbonna & Daboer 2007; Otoo et al. 2009; Ukegbu & Ukegbu 2010; Alade et al. 2013), farmers (Ukegbu & Ukegbu 2010; Alade et al. 2013) and in the civil service (Oche et al. 2011; Alade et al. 2013; Ukegbu & Anyikaelekeh 2013). In one study (Danso 2014) all mothers were in professional employment (i.e. education, health and banking). The nature of employment was not described for 13 studies (Murray et al. 2008; Petrie et al. 2008; Uchendu et al. 2009; Marais et al. 2010; Nankunda et al. 2010; Ostergaard & Bula 2010; Aksu et al. 2011; Ukegbu et al. 2011; Nor et al. 2012; Adeyemi & Oyewole 2014; Desai et al. 2014; Onah et al. 2014; Nduna et al. 2015). In 13 of the studies (Ogbonna & Daboer 2007; Petrie et al. 2008; Otoo et al. 2009; Nankunda et al. 2010; Ukegbu & Ukegbu 2010; Aksu et al. 2011; Oche et al. 2011; Abul‐Fadl et al. 2012; Alade et al. 2013; Ukegbu & Anyikaelekeh 2013; Danso 2014; Desai et al. 2014; Onah et al. 2014) all mothers had completed some form of education (primary, secondary or tertiary), but the remaining studies (n = 8) (Murray et al. 2008; Uchendu et al. 2009; Marais et al. 2010; Ostergaard & Bula 2010; Ukegbu et al. 2011; Nor et al. 2012; Adeyemi & Oyewole 2014; Nduna et al. 2015) did not report on educational attainment. In one study (Abul‐Fadl et al. 2012), however, one third of mothers had completed very little or no form of education.

The majority of studies assessed EBF knowledge via questionnaires (n = 15) (Ogbonna & Daboer 2007; Petrie et al. 2008; Uchendu et al. 2009; Marais et al. 2010; Nankunda et al. 2010; Ukegbu & Ukegbu 2010; Aksu et al. 2011; Oche et al. 2011; Abul‐Fadl et al. 2012; Alade et al. 2013; Ukegbu & Anyikaelekeh 2013; Adeyemi & Oyewole 2014; Danso 2014; Desai et al. 2014; Onah et al. 2014) and/or interviews (n = 8) (Ogbonna & Daboer 2007; Marais et al. 2010; Ostergaard & Bula 2010; Oche et al. 2011; Abul‐Fadl et al. 2012; Nor et al. 2012; Onah et al. 2014; Nduna et al. 2015). Three studies (Murray et al. 2008; Otoo et al. 2009; Ukegbu et al. 2011) used focus group discussions (FGD).

Quality appraisal

The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed (Table 3). A main area of strength was that all studies addressed a clear focused issue. The vast majority had clearly defined the population (n = 19), used appropriate methods to address the issue (n = 20), and results and data analysis were presented (n = 20) and were sufficiently rigorous (n = 19). An area of weakness for the majority of studies related to subject recruitment as 11 studies (Ogbonna & Daboer 2007; Uchendu et al. 2009; Marais et al. 2010; Nankunda et al. 2010; Ukegbu & Ukegbu 2010; Aksu et al. 2011; Ukegbu et al. 2011; Abul‐Fadl et al. 2012; Adeyemi & Oyewole 2014; Desai et al. 2014) did not explicitly state how participants were recruited or participants were not recruited in a truly random way, therefore increasing the risk of selection bias. Two studies (Murray et al. 2008; Abul‐Fadl et al. 2012) used convenience sampling so the findings may not be generalisable. There was an increased risk of selection bias as many of the studies were clinic based (n = 12); recruiting mothers who attended the clinics and missing those who had not. Four studies (Uchendu et al. 2009; Ukegbu & Ukegbu 2010; Ukegbu et al. 2011; Nduna et al. 2015) did not report detailed population demographics, and one study (Ukegbu & Ukegbu 2010) reported a different number of participants in the abstract to the main article. The risk of participation bias is increased if the sample population is not clearly defined, as there could be differences between mothers who were invited to participate in the study and mothers who enrolled.

Table 3.

Quality appraisal of the included studies (n = 21)

| Study: | Clear focused issue addressed? | Appropriate method used? | Subject recruitment | Population clearly defined? | Measures accurately measured to reduce bias? | Data collection | Participant no. | How are the results presented? | Data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | Clear statement of findings? | Results generalisable? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abul‐Fadl et al. 2012 | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ |

| Adeyemi & Oyewole 2014 | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ |

| Aksu et al. 2011 | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ |

| Alade et al. 2013 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ |

| Danso 2014 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ |

| Desai et al. 2014 | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ |

| Marias et al, 2010 | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ |

| Murray et al. 2008 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ |

| Nankunda et al. 2010 | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ |

| Nduna et al. 2015 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ |

| Nor et al. 2012 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ |

| Oche et al. 2011 | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ |

| Ogbonna & Daboer 2007 | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ |

| Onah et al. 2014 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ |

| Ostergaard & Bula 2010 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ |

| Otoo et al. 2009 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ |

| Petrie et al. 2008 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ |

| Uchendu et al. 2009 | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ |

| Ukegbu & Ukegbu 2010 | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ |

| Ukegbu et al. 2011 | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ |

| Ukegbu & Anyikaelekeh 2013 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ |

Another domain that scored poorly for seven studies (Ogbonna & Daboer 2007; Uchendu et al. 2009; Ostergaard & Bula 2010; Oche et al. 2011; Ukegbu et al. 2011; Alade et al. 2013; Danso 2014) related to whether ‘study methods were accurately assessed to reduce bias’. Measurement bias among those studies is likely to be increased because of the methods in which EBF knowledge was evaluated. The domain assessing ‘generalisability of results’ indicated a major limitation in all studies as many were conducted in specific geographical areas, with relatively small sample sizes; therefore findings are unlikely to be generalisable. The majority of studies reported on mothers who had breastfed before or were currently breastfeeding at the time of the study and therefore they may not be representative of the knowledge of mothers who had not breastfed. A question on ethical approval was not included within the quality appraisal tool; however, all studies apart from one (Ukegbu & Ukegbu 2010) reported ethical approval.

Defining EBF correctly

The percentage of mothers who knew the meaning of or could correctly define EBF (Table 4) varied greatly, ranging from 3.1% (Marais et al. 2010) to 100% (Danso 2014). The pooled proportion rate of mothers who could correctly define EBF was 70.9%. Five studies (Aksu et al. 2011; Abul‐Fadl et al. 2012; Alade et al. 2013; Adeyemi & Oyewole 2014; Desai et al. 2014) reported that between 50 and 58.1% of mothers knew the meaning of or could correctly define EBF. However, for seven studies (Ogbonna & Daboer 2007; Uchendu et al. 2009; Nankunda et al. 2010; Ukegbu & Ukegbu 2010; Ukegbu & Anyikaelekeh 2013; Danso 2014; Onah et al. 2014), the percentage of mothers who knew the meaning of EBF was higher, ranging from 72.7% (Nankunda et al. 2010) to 100% (Danso 2014). Five of these studies were conducted in Nigeria (Ogbonna & Daboer 2007; Uchendu et al. 2009; Ukegbu & Ukegbu 2010; Ukegbu & Anyikaelekeh 2013; Onah et al. 2014) and the remaining conducted in Ghana (Danso 2014) and Uganda (Nankunda et al. 2010). In contrast, three studies reported findings as low as 30% in Nigeria (Oche et al. 2011) and 11.1% (Petrie et al. 2008) and 3.1% (Marais et al. 2010) in South Africa.

Table 4.

Number of mothers correctly defining EBF (n = 15)

| Study: | Participant no. | No. of participants who answered correctly | Primary outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abul‐Fadl et al. 2012 | 1052 | 526 | 50% of mothers knew that EBF entails feeding babies on no other solid food/liquids other than breast milk. |

| Adeyemi & Oyewole 2014 | 62 | 36 | 58.1% mothers correctly defined EBF. |

| Aksu et al. 2011 | 30 | 15 | 50% of mothers could correctly define EBF. |

| Alade et al. 2013 | 410 | 209 | 51% of mothers were able to state the meaning of EFB correctly. |

| Danso 2014 | 1000 | 1000 | 100% of mothers were able to define EBF according to WHO definition. |

| Desai et al. 2014 | 295 | 159 | 54% of mothers knew the meaning of EBF. |

| Marais et al. 2010 | 64 | 2 | 3.1% of mothers could completely and correctly define EBF, mean score of 5/8. |

| Nankunda et al. 2010 | 11 | 8 | 72.7% of mothers could define EBF correctly (After training 9/11 could define EBF). |

| Oche et al. 2011 | 179 | 54 | 30% of mothers had adequate knowledge of EBF. |

| Ogbonna & Daboer 2007 | 470 | 387 | 82.3% of mothers correctly defined EBF. |

| Onah et al. 2014 | 400 | 328 | 82% mothers correctly defined EBF; 382/400 (95.3%) heard of EBF; 54/400 (13.5%) incorrectly defined; 18/400 (4.5%) gave no response. |

| Petrie et al. 2008 | 36 | 4 | 11.1% explained the term EBF correctly, 50% indicated they did not know what EBF meant and attempted no explanation. Of the 14 who explained it correctly, 6 (16.7%) thought it meant not to breastfeed at all. |

| Uchendu et al. 2009 | 184 | 173 | 94% of mothers gave the correct definition of EBF. |

| Ukegbu & Ukegbu 2010 | 353 | 270 | 76.7% of mothers knew definition, 2.3% did not and 21% were unsure. |

| Ukegbu & Anyikaelekeh 2013 | 240 | 220 | 91.7% of mothers correctly defined EBF. 6.3% were not sure, 2.1% thought the definition was feeding infants breast milk and water for first 6 months. |

EBF = exclusive breastfeeding; WHO = World Health Organisation; no = number.

Themes related to misconceptions about the term EBF

Two of the six qualitative studies indicated that mothers knew the meaning of EBF (Otoo et al. 2009; Ukegbu et al. 2011) (Table 5). However, four studies reported that mothers did not understand the term EBF, which could be categorised into three themes. The first theme identified from one study (Nor et al. 2012) was that EBF was understood as ‘not mixing two milks’ and did not exclude the addition of other foods and liquids. Quotes from mothers in this study (Nor et al. 2012) to illustrate the theme include:

‘We must not give the baby two milk things, the baby must drink only one thing’

‘I am only breastfeeding her…I started giving her the tin (infant formula) when she was one month old…. even when I mixed it with infant porridge she would just not eat it’.

Table 5.

Themes identified from qualitative studies (n = 6)

| Study: | Theme: | Primary outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Murray et al. 2008 | 2 and 3 | The majority of participants did not understand the term EBF or had no idea what it could mean. ‘Regularly breastfeeding’; ‘bottle feeding’; ‘not necessarily breastfeeding’ and ‘breastfeeding and something else’ were some of the explanations provided for the term. Some mothers were unclear if EBF could include food and fluids (water and tea), majority understood EBF to mean not to give breast milk or give with other liquids. |

| Nduna et al. 2015 | 3 | Mothers did not understand what constitutes of EBF. The concept remains elusive to mothers. Mothers who gave their infants water and breast milk considered themselves to have exclusively breastfed. |

| Nor et al. 2012 | 1 and 3 | EBF understood as ‘not mixing two milks’ (specifically breast with formula milk). The mother's idea of EBF did not exclude the mixing of other foods and liquids. EBF was described as only drinking one type of milk. |

| Ostergaard & Bula 2010 | 2 and 3 | Mothers able to paraphrase definitions of EBF. But still indicated supplementary feeding to infants. Unclear perception on what the ‘E’ stands for in EBF term. |

| Otoo et al. 2009 | No theme | Almost all knew what EBF was. Those who were not convinced about EBF defined it correctly also. |

| Ukegbu et al. 2011 | No theme | Most mothers knew that EBF means giving the baby breast milk only for the first 6 months of life. |

The second theme that emerged from two of the studies (Murray et al. 2008; Ostergaard & Bula 2010) related to the actual wording of EBF, with ‘exclusive’ being understood as the opposite, that is ‘excluding’, not giving breast milk or to give breast milk with other fluids. Mothers also stated that EBF meant ‘not necessarily breastfeeding’, ‘breastfeeding and something else’, ‘regularly breastfeeding’ or mothers could not define what EBF meant (Murray et al. 2008). The second study (Ostergaard & Bula 2010) reported similar findings where all mothers could paraphrase what EBF meant, however they misunderstood what the ‘E’ stood for in the abbreviation EBF. One mother stated:

‘I managed to practice EBF for six months and only gave gripe water when my baby was crying a lot due to stomach pain. I also gave traditional drugs…nothing else but breast milk’

The third theme was related to mothers misinterpreting that it is acceptable to give water while exclusively breastfeeding. This theme emerged from four of the qualitative studies (Murray et al. 2008; Ostergaard & Bula 2010; Nor et al. 2012; Nduna et al. 2015) where mothers gave their infants water but considered themselves to have exclusively breastfed. In one study (Nduna et al. 2015), mothers considered themselves to be practicing EBF as long as they did not give solids to their infants even though they were regularly feeding infants water. One mother demonstrated this in the following quote:

‘I would prepare for them some water to drink…There was no other food apart from water and breast milk…A baby brought up with breast milk and water is far much better than one who gets food on top of breast milk’.

The mothers in this study believed infants needed water to ‘quench thirst’. The misinterpretation that it is acceptable to give water while exclusively breastfeeding was also reported in the remaining four studies (Murray et al. 2008; Ostergaard & Bula 2010; Nor et al. 2012).

Discussion

This systematic review is the first to investigate mothers' understanding of EBF. The pooled rate of 70.9% suggests a moderate to high understanding of EBF among mothers. The findings of the review indicate, however, that the understanding of the term EBF is extremely diverse among mothers, varying between 3.1 and 100% of mothers who could correctly define EBF. The themes that emerged suggest there are several misunderstandings of the term.

Mothers confused ‘exclusive’ from the term to mean ‘not’ to give breast milk (Murray et al. 2008; Petrie et al. 2008), to give breast milk accompanied with other fluids (Murray et al. 2008), to regularly breastfeed (Murray et al. 2008) and to not mix two types of milk (specifically formula and breast milk) (Nor et al. 2012). Although some mothers correctly paraphrased the definition of EBF, many were unclear of what the ‘E’ in the abbreviation denotes (Ostergaard & Bula 2010). The studies were conducted in South Africa (Murray et al. 2008; Petrie et al. 2008; Nor et al. 2012) and Malawi (Ostergaard & Bula 2010), which may indicate a poorer knowledge of EBF among mothers in these countries. This is of concern considering the high prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) in Malawi and South Africa and the association of mother to child transmission of HIV with mixed breastfeeding (De Cock et al. 2000; Wojcicki et al. 2015). Overall, these findings highlight a clear issue about the ‘wording’ and ‘terminology’, specifically the word ‘exclusive’ used by health professionals and the public health sector to promote EBF.

EBF may be interpreted incorrectly by mothers because of inaccurate EBF messages conveyed by health professionals to mothers at health centres, antenatal clinics and hospitals (Nor et al. 2012). Health professionals' play an important role in conveying breastfeeding information to mothers (Lewallen et al. 2006); however, evidence suggests that some health professionals misunderstand EBF (Chopra et al. 2002; Cantrill et al. 2003; Shah et al. 2005; Taneja et al. 2005; Marais et al. 2010), such as encouraging supplementary feeding while exclusively breastfeeding. This highlights the need to ensure that breastfeeding training for health professionals is adequate, which requires a greater emphasis on what constitutes EBF. Educating health professionals and mothers at both prenatal and antenatal clinic levels is one way to address the misunderstanding of EBF.

Disparities in terminology between different languages may also explain mothers' lack of understanding of the EBF term. In some countries where English is not the first language, the translation of ‘exclusive’ may have slightly different meanings and mothers could be interpreting it differently to what the WHO definition implies. The word ‘exclusive’ can also be defined as ‘excluding’ (Oxford dictionary of English 2010); therefore, EBF could be interpreted as ‘excluding’ breastfeeding and may be a reason why some mothers thought EBF meant to not breastfeed (Murray et al. 2008; Petrie et al. 2008). Language barriers in understanding the term ‘EBF’ could be addressed with a more precise term for EBF, such as ‘fed only on breast milk’ or as suggested by South African authors (Du Plessis and Pereira, 2013) in the formulation of paediatric food‐based dietary guidelines for the country: ‘Give only breast milk, and no other foods or liquids, to your baby for the first six months of life’. Another suggestion to bridge this language gap could include consumer testing of the terminology with users, in this case mothers/women, across various languages and cultural groups. The use of media and especially social media to ‘normalise’ the ‘tested’ terminology to the public as well as standardisation of terms used globally and across the sector is important so that the public are hearing the same term wherever they are and have been primed on the meaning by social marketing strategies. There are also other WHO terms that are not widely used or understood in the public domain, for example ‘complementary feeding’ (Newby et al. 2014). Knowledge of other WHO terms related to infant feeding, as well as EBF, among different languages, is therefore an area of research that could be assessed in future studies.

Another major finding of the review was that mothers regularly gave water to infants but still considered themselves to be exclusively breastfeeding. Giving gripe water or glucose water was common as it was deemed a traditional practice (Murray et al. 2008; Ostergaard & Bula 2010; Ukegbu & Anyikaelekeh 2013; Nduna et al. 2015). Mothers believed infants aged less than six months needed water to quench their thirst or sooth them when they were distressed. Similar findings have been shown in the literature (Das & Ahmed 1995; Tarek et al. 2011). This finding is of concern; as feeding an infant under six months old with water can put them at risk of diarrhoea and malnutrition, especially in LMIC, where safety of water sources is a concern (Wright et al. 1989; Ip et al. 2007).

Giving water to infants less than six months appeared to be influenced by the advice given to mothers from influential members of the family, such as grandmothers or mothers‐in‐law. Mothers had an inadequate understanding of EBF when grandmothers were their main source of information (Oche et al. 2011). However mothers had a better understanding of EBF when they received information and advice from antenatal clinics, some of which were accredited Baby Friendly Hospital (Ogbonna & Daboer 2007; Uchendu et al. 2009; Ukegbu & Ukegbu 2010; Ukegbu & Anyikaelekeh 2013; Onah et al. 2014). It is essential that mothers are able to follow a safe and optimal feeding method for their infants and avoid being influenced by incorrect information from family members. Public campaigns and initiatives could benefit from promoting EBF toward all women, including grandmothers, in order to target all who are influential on mothers' feeding choices (Goosen et al. 2014).

Studies that found most mothers knew the correct meaning of EBF reported results ranging from 72.7 (Nankunda et al. 2010) to 100% (Danso 2014). The literature suggests positive associations between women's educational level and their knowledge and practice of EBF (Ameer et al. 2008). In one study with mothers from Ghana who were in professional full‐time employment, 100% of mothers could define EBF, which may be because of the mothers' high level of education (Danso 2014). Breastfeeding is socially acceptable in Ghana and seen as the ‘norm’ so mothers may be more likely to breastfeed (Aidam et al. 2005).

The majority of studies that reported that most mothers knew the correct meaning of the term ‘EBF’ were conducted in Nigeria (Ogbonna & Daboer 2007; Uchendu et al. 2009; Ukegbu & Ukegbu 2010; Ukegbu & Anyikaelekeh 2013; Onah et al. 2014). The percentage of mothers who could define EBF ranged between 82 (Onah et al. 2014) and 91.7% (Ukegbu & Anyikaelekeh 2013). The high proportion of mothers who could define EBF may have resulted from EBF advice and education through the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative during antenatal and postnatal clinics in Nigeria (Ogbonna & Daboer 2007; Uchendu et al. 2009; Ukegbu & Ukegbu 2010; Ukegbu & Anyikaelekeh 2013; Onah et al. 2014).

A major flaw regarding the measure of assessing EBF knowledge was apparent in one of the studies reviewed (Oche et al. 2011). EBF knowledge was assessed through two aspects: duration of EBF and feeding the infant with breast milk only. To score ‘adequately’ the mothers only had to achieve a score of 50% on this question, meaning they only needed to answer one of the two aspects of the EBF definition correctly. The study implied that 30% of mothers knew the definition of EBF, yet 30% of mothers could have answered correctly for the ‘duration’ aspect, but incorrectly for the ‘breast milk only and nothing else’ aspect and vice versa. This finding may have consequently over reported how many mothers understood the definition of EBF, defined as ‘feeding the infant with breast milk only’. This ‘scoring’ issue is also evident in other literature concerning mothers' knowledge of EBF. Tarek et al. (2011) assessed EBF knowledge through a closed‐ended question in a questionnaire. The question asked for an EBF definition; however, mothers only had to mention ‘for six months’ to score correctly and did not have to mention exclusivity of breast milk. This question assessed mothers on the recommendation of EBF rather than the actual definition and is subject to potential measurement biases. This highlights a need to develop a validated tool that can assess EBF knowledge in a consistent and accurate way. See Box 1 which suggests key consideration aspects for future research regarding mothers' misconceptions of the term EBF.

Box 1: Key consideration aspects for future research regarding mothers' misconceptions of the term EBF.

The use of EXCLUSIVE should be reconsidered as mothers' misconceptions especially relate to this word. Translations of the term and within different cultural contexts should be investigated.

Emphasis needs to be placed on the fact that giving water results in non‐exclusive breastfeeding as mothers still believe that giving water is ‘allowed’ when exclusively breastfeeding.

A standardised tool to assess mothers' knowledge and understanding of EBF, based on the WHO definition (not including duration), is required for any research related to EBF.

Mothers' understanding of the term EBF needs to be investigated in high income countries.

Research implications

Mothers' misunderstanding of the wording of ‘EBF’ could have implications for research reporting on EBF practices, prevalence and trends, when self‐report measures have been used to assess EBF. If mothers reported they were exclusively breastfeeding, yet they were also giving supplementary fluids to their infant (Ostergaard & Bula 2010), the number of mothers truly exclusively breastfeeding is likely to be overestimated. For example, in Malawi, EBF prevalence is higher than most countries in the world at approximately 71.4% (Indexmundi 2014); however, EBF prevalence tend to be based on household surveys or similar measures involving self‐report methods. If mothers do not understand the true meaning of EBF, then the true prevalence of EBF may be lower than reported. Research which has investigated the barriers and facilitators of EBF for mothers is also likely to be inaccurate. This is a concern globally considering the extensive literature base that exists on practices, prevalence, trends and barriers of EBF, which could be incorrect if subjective measures have been employed.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first systematic review to examine whether mothers understand the term EBF. The review involved an exhaustive search of available and relevant literature using a comprehensive search strategy across eight databases, starting from when the term EBF originated and with no language restrictions imposed.

A key limitation of the systematic review is that the findings are based on outcomes that were often not the ‘main objective’ of the studies or on anecdotal reports within the study findings. The findings of the systematic review must be interpreted with caution considering the heterogeneity among the included studies. All of the included studies were conducted in LMIC, which may bias findings to this context and not be generalisable to HIC. Publication bias should also be considered, as some electronic journals were not accessible, resulting in six full text articles that were unable to be located through inter‐library loans (Supporting information: Appendix 2). Although 12 articles were translated into English, one Croatian article was excluded, as a translator was not found and the full text was unable to be located through inter‐library loans (Supporting information: Appendix 2). This is a limitation of the review, considering Croatia is considered a HIC (Country Income Groups (World Bank Classification) & Country and Lending Groups 2011).

Source of funding

Funding was received from the Graduate School, College of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Aberdeen. JH is supported by funding from the Rural and Environment Science and Analytical Services Division (RESAS) programme of the Scottish Government.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor statement

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the review. RS conducted the review as first reviewer and drafted the article. DM and JH contributed as second reviewers during title and abstract screening, full text reading, data extraction and quality appraisal. DM and JH also provided critical feedback for revision of the article. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published.

Supporting information

Appendix 1: Critical appraisal tool

Appendix 2: List of articles unavailable through inter‐library loans/translator not available

Supporting info item

Acknowledgments

We thank the Public Health Nutrition Research Group at the University of Aberdeen for all their support and advice. We also thank the Librarians at the Medical Library, University of Aberdeen, for their advice with developing the search strategy and their assistance with inter library loans.

Still, R. , Marais, D. , and Hollis, J. L. (2017) Mothers' understanding of the term ‘exclusive breastfeeding’: a systematic review. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 13: e12336. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12336.

References

- Abul‐Fadl A.M., Shawky M., El‐Taweel A., Cadwell K. & Turner‐Maffei C. (2012) Evaluation of mothers' knowledge, attitudes, and practice towards the ten steps to successful breastfeeding in Egypt. Breastfeeding Medicine: The Official Journal of the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine 7 (3), 173–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adeyemi O.A. & Oyewole O.E. (2014) How can we really improve childcare practices in Nigeria? Health Promotion International 29 (2), 369–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aidam B.A., Perez‐Escamilla R., Lartey A. & Aidam J. (2005) Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding in Accra, Ghana. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 59 (6), 789–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aksu H., Küçük M. & Düzgün G. (2011) The effect of postnatal breastfeeding education/support offered at home 3 days after delivery on breastfeeding duration and knowledge: a randomized trial. Journal of Maternal‐Fetal and Neonatal Medicine 24 (2), 354–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alade O., Titiloye M.A., Oshiname F.O. & Arulogun O.S. (2013) Exclusive breastfeeding and related antecedent factors among lactating mothers in a rural community in Southwest Nigeria. International Journal of Nursing 5 (7), 132–138. [Google Scholar]

- Ameer A., Al‐Hadi A. & Abdulla M. (2008) Knowledge, attitudes and practices of Iraqi mothers and family child‐caring women regarding breastfeeding. East Mediterranean Health Journal 14 (5), 1003–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arifeen S., Black R.E., Antelman G., Baqui A., Caulfield L. & Becker S. (2001) Exclusive breastfeeding reduces acute respiratory infection and diarrhea deaths among infants in Dhaka slums. Pediatrics 108 (4), E67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arimond M. & Ruel M.T. (2002) Progress in Developing an Infant and Child Feeding Index: An Example Using the Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2000. International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Cantrill R.M., Creedy D.K. & Cooke M. (2003) An Australian study of midwives' breast‐feeding knowledge. Midwifery 19 (4), 310–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield L.E., Richard S.A., Rivera J.A., Musgrove P. & Black R.E. (2006) Stunting, wasting, and micronutrient deficiency disorders (eds Jamison D.T., Breman J.G., Measham A.R. et al), Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. 2nd edition Washington (DC): World Bank; 2006. Chapter 28. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11761/ [Accessed 15/08/15]. [Google Scholar]

- Centers For Disease Control And Prevention (CDC) (2007) Breastfeeding trends and updated national health objectives for exclusive breastfeeding – United States, birth years 2000–2004. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 56 (30), 760–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C.H., Shu H.Q. & Chi C.S. (2001) Breastfeeding knowledge and attitudes of health professionals and students. Acta Paediatrica Taiwanica = Taiwan er ke yi xue hui za zhi 42 (4), 207–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopra M., Piwoz E., Sengwana J., Schaay N., Dunnett L. & Sanders D. (2002) Effect of a mother‐to‐child HIV prevention programme on infant feeding and caring practices in South Africa. South African Medical Journal Cape Town Medical Association of South Africa 92 (4), 298–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Country Income Groups (World Bank Classification) , Country and Lending Groups (2011) The World Bank Group. Available at: http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-classifications/country-and-lending-groups. [Accessed 11/03/16].

- Danso J. (2014) Examining the practice of exclusive breastfeeding among professional working mothers in Kumasi metropolis of Ghana. International Journal of Nursing 1 (1), 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Das D.K. & Ahmed S. (1995) Knowledge and attitude of the Bangladeshi rural mothers regarding breastfeeding and weaning. Indian Journal of Pediatrics 62 (2), 213–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Cock K.M., Fowler M.G., Mercier E., De Vincenzi I., Saba J., Hoff E. et al (2000) Prevention of mother‐to‐child HIV transmission in resource‐poor countries: translating research into policy and practice. JAMA 283 (9), 1175–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai A., Mbuya M.N.N., Chigumira A., Chasekwa B., Humphrey J.H., Moulton L.H. et al (2014) Traditional oral remedies and perceived breast milk insufficiency are major barriers to exclusive breastfeeding in rural Zimbabwe. Journal of Nutrition 144 (7), 1113–1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Plessis L.M. & Pereira C. (2013) Commitment and capacity for the support of breastfeeding in South Africa. South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition 26 (S), 120–128. [Google Scholar]

- Global Nutrition Report (2015) Actions And Accountability To Advance Nutrition And Sustainable Development. International Food Policy Research Institute. 2015. Washington, DC. Available at: https://www.ifpri.org/publication/global-nutrition-report-2015. [Accessed 17/06/2015] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Goosen C., McLachlan M.H. & Schubl C. (2014) Factors impeding exclusive breastfeeding in a low‐income area of the Western Cape province of South Africa. Africa Journal of Nursing and Midwifery 16 (1), 13–31. [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt G., Sackett D. & Cook D. (1993a) Users' guides to the medical literature, II: how to use an article about therapy or prevention, A: are the results of the study valid? JAMA 270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt G.H., Sackett D.L., Cook D.J., Guyatt G., Bass E., Brill‐Edwards P. et al (1993b) Users' guides to the medical literature: II. How to use an article about therapy or prevention a. Are the results of the study valid? JAMA 270 (21), 2598–2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indexmundi (2014) (last update), Malawi: Exclusive Breastfeeding. Available: http://www.indexmundi.com/facts/malawi/exclusive-breastfeeding [Accessed 15/07/2015, 2015].

- Ip S., Chung M., Raman G., Chew P., Magula N., Devine D. et al. (2007) Breastfeeding and maternal and infant health outcomes in developed countries. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment 153, 1–186. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer M. & Kakuma R. (2009) Optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012 (8), CD003517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer M.S. & Kakuma R. (2004) The optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding In: Protecting Infants through Human Milk, Vol. 554, pp 63–77. Springer: US. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laanterä S., Pölkki T. & Pietilä A. (2011) A descriptive qualitative review of the barriers relating to breast‐feeding counseling. International Journal of Nursing Practice 17 (1), 72–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labbok M. & Krasovec K. (1990) Toward consistency in breastfeeding definitions. Studies in Family Planning 21 (4), 226–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewallen L.P., Dick M.J., Flowers J., Powell W., Zickefoose K.T., Wall Y.G. et al (2006) Breastfeeding support and early cessation. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing 35 (2), 166–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marais D.B., Koornhof H.E., Du Plessis M.L., Naude C.E., Smit K., Treurnicht R., et al (2010) Breastfeeding policies and practices in healthcare facilities in the Western Cape Province, South Africa 23(1).

- Mcintyre E. & Lawlor‐smith C. (1996) Improving the breastfeeding knowledge of health professionals. Australian Family Physician 25 (9 Suppl 2), S68–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G; The PRISMA Group (2009) Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6 (7): e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray S., Tredoux S., Viljoen L., Herselman M. & Marais D. (2008) Consumer testing of the preliminary Paediatric Food‐Based Dietary Guidelines (PFBDG) among mothers with infants younger than 6 months in selected urban and rural areas in the Western Cape. South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition 21 (1), 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- Nankunda J., Tylleskar T., Ndeezi G., Semiyaga N. & Tumwine J.K. (2010) Establishing individual peer counselling for exclusive breastfeeding in Uganda: implications for scaling‐up. Maternal & Child Nutrition 6 (1), 53–66 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nduna T., Marais D. & Van Wyk B. (2015) An explorative qualitative study of experiences and challenges to exclusive breastfeeding among mothers in rural Zimbabwe. ICAN: Infant, Child, & Adolescent Nutrition 7 (2), 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Newby R., Brodribb W., Ware R.S. & Davies P.S. (2014) Infant feeding knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs predict antenatal intention among first‐time mothers in Queensland. Breastfeeding Medicine 9 (5), 266–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nor B., Ahlberg B.M., Doherty T., Zembe Y., Jackson D. & Ekstrom E.C. (2012) Mother's perceptions and experiences of infant feeding within a community‐based peer counselling intervention in South Africa. Maternal & Child Nutrition 8 (4), 448–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oche M.O., Umar A.S. & Ahmed H. (2011) Knowledge and practice of exclusive breastfeeding in Kware, Nigeria. African Health Sciences 11 (3), 518–523 29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogbonna C. & Daboer J.C. (2007) Current knowledge and practice of exclusive breastfeeding among mothers in Jos, Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Medicine: Journal of the National Association of Resident Doctors of Nigeria 16 (3), 256–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okolo S.N., Adewunmi Y.B. & Okonji M.C. (1999) Current breastfeeding knowledge, attitude, and practices of mothers in five rural communities in the Savannah region of Nigeria. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics 45 (6), 323–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onah S., Osuorah D.I.C., Ebenebe J., Ezechukwu C., Ekwochi U. & Ndukwu I. (2014) Infant feeding practices and maternal socio‐demographic factors that influence practice of exclusive breastfeeding among mothers in Nnewi South‐East Nigeria: a cross‐sectional and analytical study. International Breastfeeding Journal 9 (6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostergaard L.R. & Bula A. (2010) “They call our children “Nevirapine babies?””: a qualitative study about exclusive breastfeeding among HIV positive mothers in Malawi. African Journal of Reproductive Health 14 (3), 213–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otoo G.E., Lartey A. & Perez‐Escamilla R. (2009) Perceived incentives and barriers to exclusive breastfeeding among peri‐urban Ghanaian women. Journal of Human Lactation 25 (1), 34–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxford dictionary of English (2010) In: Oxford Dictionary, 3rd ed. Oxford University Press: Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Petrie K., Schmidt S., Schwarz C., Koornhof H. & Marais D. (2008) Knowledge, attitudes and practices of women regarding the prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission (PMTCT) programme at the Vanguard Community Health Centre, Western Cape – a pilot study. South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition 20 (2), 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Piwoz E.G., Creed De Kanashiro H., Lopez De Romana G., Black R.E. & Brown K.H. (1995) Potential for misclassification of infants' usual feeding practices using 24‐hour dietary assessment methods. The Journal of Nutrition 125, 57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piwoz E.G., Ferguson Y.O., Bentley M.E., Corneli A.L., Moses A., Nkhoma J. et al (2006) Differences between international recommendations on breastfeeding in the presence of HIV and the attitudes and counseling messages of health workers in Lilongwe, Malawi. International Breastfeeding Journal 1 (1), 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRISMA Checklist . (2009) Transparent reporting of Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses2014‐last update. Available: http://www.prisma-statement.org. [Accessed 07/06/2015, 2015].

- Shah S., Rollins N.C., Bland R. & CHILD HEALTH GROUP (2005) Breastfeeding knowledge among health workers in rural South Africa. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics 51 (1), 33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taneja D., Misra A. & Mathur N. (2005) Infant feeding – an evaluation of text and taught. Indian Journal of Pediatrics 72 (2), 127–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarek A., Hatem H. & Alqader A.A. (2011) Determinants of initiation and exclusivity of breastfeeding in Al Hassa, Saudi Arabia. Breastfeeding Medicine 6 (2), 59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennant R., Wallaceba L.M. & Law S. (2006) Barriers to breastfeeding: a qualitative study of the views of health professionals and lay counsellors. Community Practitioner 79 (5), 152–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Cochrane Collaboration (2015) (last update) Data Collection Form, Intervention Review – RCT's only. Available at: http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:o2JDIGgCqkEJ:hiv.cochrane.org/sites/hiv.cochrane.org/files/uploads/Data%2520extraction%2520form_RCTs.docx+&cd=2&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=uk&client=safari. [Accessed 10/06/15].

- Uchendu U.O., Ikefuna A.N. & Emodi I.J. (2009) Exclusive breastfeeding – the relationship between maternal perception and practice. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice 12 (4), 403–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ukegbu A.U., Ebenebe E.U., Ukegbu P.O. & Onyeonoro U.U. (2011) Determinants of breastfeeding pattern among nursing mothers in Anambra State, Nigeria. East African Journal of Public Health 8 (3), 226–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ukegbu P.O. & Anyikaelekeh J.U. (2013) Influence of maternal characteristics on exclusive breastfeeding practice among urban mothers in Umuahia, Nigeria. Malaysian Journal of Nutrition 19 (3), 311–323. [Google Scholar]

- Ukegbu P.O. & Ukegbu A.U. (2010) Breastfeeding practices among rural mothers in Imo State, Nigeria. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture and Environment 12 (1), 68–77. [Google Scholar]

- Wojcicki J.M., Nxumalo N.C. & Masuku S. (2015) Preventing mother‐to‐child transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus in Southern Africa. Acta Paediatrica 104 (12), 1211–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (1991) Indicators for assessing breast feeding practices. Division Of Child Health And Development. WHO Document WHO/CDD/SER 91, 14. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2008a) Indicators for Assessing Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices: Part I. World Health Organization; Geneva. Switzerland: [Online]. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241596664_eng.pdf?ua=1. [Accessed 12/2/16]. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2008b) Indicators for Assessing Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices: Part 3. World Health Organization; Geneva: Switzerland. [Online]. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241596664_eng.pdf?ua=1 [Accessed 12/2/16]. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2014) (last update) The World Health Organization global data bank on infant and young child feeding Geneva: World Health Organization Available at: http://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.main.NUT1730?lang=en [Accessed 09/05/15].

- World Health Organization (2016) Exclusive Breastfeeding. Available at: http://www.who.int/elena/titles/exclusive_breastfeeding/en/ [Accessed 12/02/16].

- Wright A.L., Holberg C.J., Martinez F.D., Morgan W.J. & Taussig L.M. (1989) Breast feeding and lower respiratory tract illness in the first year of life. Group Health Medical Associates. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 299 (6705), 946–949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakarija‐Grković I. & Burmaz T. (2010) Effectiveness of the UNICEF/WHO 20‐hour course in improving health professionals' knowledge, practices, and attitudes to breastfeeding: before/after study of 5 maternity facilities in Croatia. Croatian Medical Journal 51 (5), 396–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zohoori N., Popkin B.M. & Fernandez M.E. (1993) Breastfeeding patterns in the Philippines: a prospective analysis. Journal of Biosocial Science 25, 127–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1: Critical appraisal tool

Appendix 2: List of articles unavailable through inter‐library loans/translator not available

Supporting info item