Abstract

Infections caused by multidrug resistant bacteria represent a therapeutic challenge both in clinical settings and in livestock production, but the prevalence of antibiotic resistance genes among the species of bacteria that colonize the gastrointestinal tract of ruminants is not well characterized. Here, we investigate the resistome of 435 ruminal microbial genomes in silico and confirm representative phenotypes in vitro. We find a high abundance of genes encoding tetracycline resistance and evidence that the tet(W) gene is under positive selective pressure. Our findings reveal that tet(W) is located in a novel integrative and conjugative element in several ruminal bacterial genomes. Analyses of rumen microbial metatranscriptomes confirm the expression of the most abundant antibiotic resistance genes. Our data provide insight into antibiotic resistange gene profiles of the main species of ruminal bacteria and reveal the potential role of mobile genetic elements in shaping the resistome of the rumen microbiome, with implications for human and animal health.

Subject terms: Microbiology, Agriculture

Here, the authors combine in silico analysis of 435 genomes of ruminal bacteria and archaea with transcriptomics and in vitro assays to investigate the distribution, expression and mobility of antibiotic resistance genes within the ruminal microbiota, finding that the tet(W) gene is under positive selective pressure.

Introduction

Without immediate action to tackle the current and escalating threat of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), it is estimated that resistant infections may kill one person every 3 s by the year 2050, raising the death toll worldwide to 10 million annually1. This antibiotic-resistance crisis can be linked to several issues, including the overuse of these compounds for medical and agricultural purposes, inappropriate antibiotic prescribing, and limited discovery/development of novel and effective antibiotics2. The widespread use of antibiotics in the agricultural sector plays an underrepresented role in the AMR context. Large amounts of antimicrobials are frequently used in livestock to prevent diseases and promote animal growth3. More than 2 million kilograms of medically important antibiotics were sold in the USA for use in cattle in 2017, which corresponded to 42% of the total used in food-producing animals, and ruminants have been recognized as a potential reservoir of antibiotic-resistance genes (ARGs)4,5.

The rumen ecosystem is colonized by a complex and genetically diverse microbiota, in which dense populations of microbes often exist in close proximity within biofilms6. Therefore, mechanisms that lead to horizontal acquisition of novel genes could provide competitive advantage for resource competition and facilitate the exchange of genetic material between members of the rumen microbiota and also with allochthonous species that occupy the same site in the ruminant gastrointestinal tract (GIT)7–10. In addition, feeding antimicrobials through ruminant diets can select for resistant organisms, potentially modifying the autochthonous ruminal microbiota11. These findings corroborate with recent analyses of the ovine rumen resistome, which identified resistances to 30 known antibiotics, including high abundance of genes for daptomycin and colistin resistance, two clinically relevant antibiotics5.

Ruminants represent a major source of animal protein for human consumption worldwide (through milk and meat production), and cattle are raised in close proximity with humans, such as in rural areas, particularly in lower-middle-income nations, where a great proportion of the livestock farms are small, family-owned properties. Nonetheless, little is known about the occurrence and distribution of ARGs among the bacterial species of the core rumen microbiome. Recently, hundreds of reference genomes of cultured ruminal bacteria and archaea have been made available through the Hungate Project (http://www.hungate1000.org.nz/), representing ~75% of the genus-level bacterial and archaeal taxa present in the rumen12. We therefore hypothesized that genome mining of the Hungate genomic resources could reveal the distribution and genetic context of ARGs within major ruminal species represented in the core rumen microbiome.

As such we analyzed 435 genomes of ruminal bacteria and archaea to search for ARGs using different computational approaches. Identified ARGs were also evaluated for selective pressure, genetic organization, association with mobile genetic elements, as well as their expression in different rumen metatranscriptome data sets. The resistant phenotype was confirmed for some cultured representative ruminal bacteria from the sequenced Hungate1000 collection using in vitro testing and a novel integrative and conjugative element (ICE) associated with tetracycline resistance was identified in the genomes of rumen bacteria. Our findings shed light on the distribution and frequency of ARGs among the main species of bacteria colonizing the rumen, thereby improving our understanding of the mechanisms underlying antibiotic resistance within this microbial ecosystem.

Results

Detection of ARGs in ruminal microbial genomes

The number and classes of ARGs detected in rumen microbial genomes using ResFinder13, Resfams14, and ARG-ANNOT15 varied according to differences in specificity, sensitivity, and search method used by each computational tool. ResFinder identified a total of 141 acquired ARGs distributed in 72 rumen microbial genomes and across 11 antibiotic classes (Table 1). ARG-ANNOT detected 754 genes from 10 distinct antibiotic classes in 93 genomes of rumen bacteria, while Resfams predicted 3148 sequences related to the resistance of 9 classes of antibiotics in 430 rumen microbial genomes (Table 1; Supplementary Fig. 1). The most abundant ARGs detected by all three bioinformatic tools were related with resistance to beta-lactams (726 genes), glycopeptides (510), tetracycline (307), and aminoglycosides (193).

Table 1.

In silico detection of ARGs in ruminal microbial genomes

| General features | ResFinder | ARG-ANNOT | Resfams |

|---|---|---|---|

| ARGs detected | 141 | 754 | 3148 |

| Genomes with ARGs | 72 | 93 | 430 |

| ARGs by antibiotic class/function | |||

| Aminoglycosides | 10 | 26 | 157 |

| Beta-lactams | 11 | 446 | 269 |

| Colistin | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fosfomycin | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Fluoroquinolones | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| Fusidic acid | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Glycopeptides | 22 | 76 | 412 |

| MLS | 22 | 44 | 44 |

| Nitromidazole | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Oxazolidinone | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Phenicols | 3 | 10 | 19 |

| Rifampicin | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sulfonamides | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Tetracyclines | 61 | 130 | 116 |

| Trimethoprim | 1 | 14 | 0 |

| ABC efllux | – | – | 1749 |

| RND efllux | – | – | 165 |

| Othersa | – | – | 215 |

| ARG’s by taxonomic category | |||

| Actinobacteria (n = 32) | 7 | 11 | 164 |

| Bacteroidetes (n = 50) | 30 | 67 | 199 |

| Fibrobacteres (n = 2) | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Firmicutes (n = 313) | 89 | 233 | 2502 |

| Fusobacteria (n = 1) | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Proteobacteria (n = 22) | 15 | 443 | 244 |

| Spirochetes (n = 5) | 0 | 0 | 27 |

| Euryarchaeota (n = 10) | 0 | 0 | 6 |

MLS Macrolides, Lincosamides, Streptogramins

aARGs that could not be ranked in any of the above antibiotic classes/functions; (−) these ARGs are not included in the ResFinder and ARG-ANNOT data sets

Resfams detected the majority of the aminoglycosides and glycopeptides-resistance genes, while ARG-ANNOT identified the most beta-lactam-resistance genes in the rumen bacterial genomes. Fluoroquinolone, fosfomycin, nitroimidazole, and trimethoprim were the antibiotic classes with the lowest number of ARGs identified using ResFinder, Resfams, and ARG-ANNOT. These putative ARGs were more prevalent among members of the phyla Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Actinobacteria, but their abundances varied according to the bioinformatic tool used for ARG detection (Table 1; Supplementary Fig. 2).

Phylogenetic distribution of ARGs

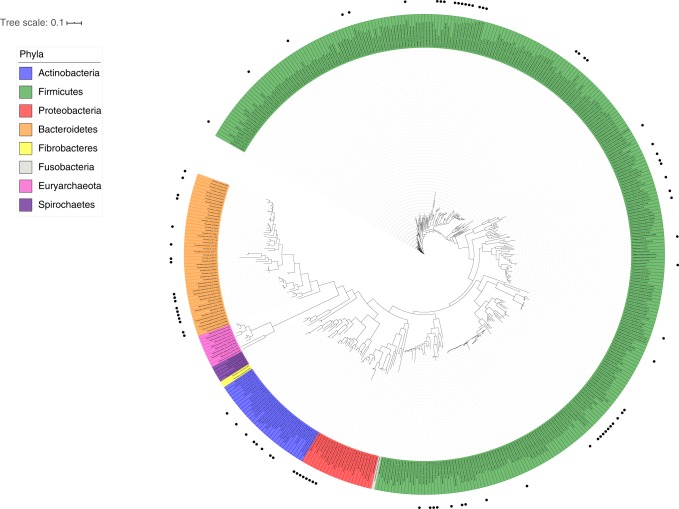

Although ARGs were widely distributed across the genomes of ruminal bacteria (Fig. 1), resistance to specific antibiotic classes were more prevalent in some bacterial taxa, especially at the family and genus level. Members of the Proteobacteria phylum showed a high proportion of genomes harboring resistance genes, with ARGs being detected in all genomes of the Enterobacteriaceae family. In the Bacteroidetes and Actinobacteria phyla, ARGs were concentrated in the genus Bacteroides and Bifidobacterium, respectively. In the Firmicutes phylum (which corresponded to the largest number of genomes analyzed in this study), resistance genes were detected across members of the Lachnospiraceae (Lachnosclostridium, Clostridium, and Blautia) and Veillonellaceae (Selenomonas, Megamonas, and Megasphaera) families, as well as in all species of the genus Enterococcus and among strains of Staphylococcus epidermidis. No antibiotic-resistance genes were detected in genomes belonging to the Spirochetes, Fibrobacteres, Fusobacteria, and Euryarchaeota phyla using Resfinder and ARG-ANNOT, but it should be noted that the number of genomes representing these taxa were much lower compared with the other phyla analyzed in this study. Although Resfams detected some potential ARGs in these microbial taxa, the majority were ABC efflux pumps. The ABC efflux pumps represent one of the largest protein families in microorganisms, contributing not only to reduce the intracellular concentrations of toxic compounds but also to the influx of substrates and other nutrients, and are not necessarily related to antibiotic resistance16.

Fig. 1.

Antibiotic-resistance distribution in ruminal microbes. The 16S rRNA gene sequences used to construct the tree were obtained from the Hungate1000 collection and aligned using RDP Aligner. The phylogenetic tree was generated with the Maximum-Likelihood method using FastTree (1000 replicates), and visualized and annotated using iTOL. Black circles outside the tree represent the genomes, in which ARGs were identified from at least two bioinformatics tools applied in this study

The distribution of the ARGs in ruminal microbial genomes was represented by the antibiotic class and according to the 16S rRNA gene phylogeny (Fig. 2). Majority of the genomes (69.2%) showed resistance to one antibiotic class, with a dominance of tetracycline-resistance genes, which were distributed in bacterial genomes within the phyla Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, and Bacteroidetes. Phylogenetic analysis of the most abundant tetracycline-resistance genes (tet(W), tet(Q), and tet(O)) revealed that tet(W) was highly conserved across different taxa of ruminal bacteria, with a minimum sequence identity of 94.9 and 99% coverage in at least 28 ruminal bacterial genomes (Supplementary Figs. 3–5).

Fig. 2.

Distribution of ARGs in species of ruminal bacteria. The distribution of the resistance genes detected by at least two bioinformatic tools used in this study is presented in front of the tree as filled colored boxes. The 16S rRNA gene sequences used to construct the tree were obtained from the Hungate1000 collection and aligned using RDP Aligner. The tree was generated with the Maximum-Likelihood method using FastTree (1000 replicates) and visualized and annotated using iTOL. Only bootstrap values >0.7 are shown

Moreover, as shown in Fig. 2, metronidazole and fosfomycin resistance were only identified in the genus Prevotella and in two strains of Staphylococcus epidermidis, respectively. Staphylococcus epidermidis together with Citrobacter sp. NLAE-zl-C269 were the only species harboring resistance genes to quinolones. Escherichia coli PA-3 was the single ruminal genome showing the highest number of ARGs (n = 5), including tetracycline resistance, beta-lactam resistance, aminoglycoside resistance, trimethoprim resistance, and sulfonamide resistance. Bacteroides ovatus NLAE-zl-C500 was the only species in Bacteroidetes-possessing genes for sulfonamide resistance. Beta-lactam-resistance genes were concentrated in the family Enterobacteriaceae, in the genus Bacteroides, and in two clades harboring the genera Selenomonas, Staphylococcus, Succiniclasticum, and Bacillus. Proteus mirabilis NLAE-zl-G534 and Proteus mirabilis NLAE-zl-G285 shared the same pattern of resistance to tetracycline and phenicol, while Staphylococus epidermidis AG42 and Staphylococus epidermidis NLAE-zl-G239 harbored highly homologous resistance genes for beta-lactams, quinolones, and fosfomycin.

ARGs genetic context

The genetic locus of the tet(W) genes as well as their flanking regions were analyzed to investigate their mobility potential. For this, the 28 genomes harboring tet(W) genes detected by ResFinder were evaluated in sequences of up to 4000 bp within the scaffold where tet(W) was located. Genes encoding a putative methyltransferase protein were detected adjacent to or located immediately upstream or downstrem of the tet(W) gene in 18 genomes. From these, the gene encoding the protein under the accession number D1PK82 [https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/D1PK82] was the most prevalent, and showed 98.9–100% sequence identity across the genomes of ruminal bacteria. In seven of these genomes, a gene encoding the Maff-2 protein, which is known to be involved in bacterial resistance to tetracycline, was also found flanking the tet(W) gene. Genes encoding transposon proteins (e.g., TnpW, TnpV, Tnp, TnpX, and ISPsy9) were identified flanking the tet(W) gene in 10 ruminal microbial genomes, and 22 out of the 28 genomes harboring tet(W) genes also had genes encoding proteins potentially involved in bacterial conjugation, such as relaxases, plasmid mobilization proteins (e.g., MobC), and conjugation proteins (e.g., TraE, TraG/TraD). In addition, genes enconding phage proteins (e.g., PhiRv2) were detected in the flanking regions of the tet(W) genes in ten ruminal microbial genomes (Supplementary Data 1). Nonetheless, the scaffolds carrying the tet(W) genes lacked complete mobile elements showing the structural organization commonly found in plasmids, phages, and transposons.

A more detailed analysis of the sequences flanking the tet(W) gene revealed that at least seven genomes contained the complete machinery required for a functional ICE, despite the fact that no such genetic elements were found when the bacterial genomes were screened for using ICEberg17. The genetic organization of the ICEs identified in the genomes of ruminal bacteria, as exemplified for Blautia schinkii DSM 10518 (Fig. 3a), contained putative genes encoding for conjugation proteins (e.g., TraE), secretion proteins (e.g., VirD4), proteins controlling the cellular cycle (e.g., RepA, DnaI, σ70), and recombinases, in addition to other accessory proteins commonly found associated with these mobile elements (e.g., ATPases, methyltransferases, transposons, and phage-related proteins). The hypothesis that a novel ICE (named here as ICE_RbtetW_07) could be mediating tetracycline resistance in the genomes of rumen bacteria was reinforced by the presence of conserved elements (reversed organization in three genomes) in the ICE carrying the tet(W) genes on ruminal bacterial chromosomes (Fig. 3b). Moreover, phylogenetic analyses indicated that the ICE_RbtetW_07 had low sequence homology to other integrative conjugative elements previously reported (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Fig. 3.

ICE_RbtetW_07 structure and conservation. a ICE_RbtetW_07 structure in Blautia schinkii DSM 10518. The genes of the ICE are represented by arrows classified and colored in modules according to their function. The essential modules of the ICE machinery are represented in orange, blue, and pink, for mobilization, recombination, and regulation genes, respectively. The ICE is located in scaffold 17 (nucleotide positions from 88079 to 111915) of the Blautia schinkii DSM 10518 genome. b Alignment of the ICE_RbtetW_07 from ruminal bacterial genomes Blautia schinkii DSM 10518, Butyrivibrio hungatei DSM 14810, Lachnoclostridium aminophilum DSM 10710, Lachnoclostridium citroniae NLAE-zl-G70, Lachnoclostridium lavalense NLAE-zl-G277, Pseudobutyrivibrio sp. NOR37, and Pseudobutyrivibrio sp. OR37. Lines connecting blocks with identical colors represent the aligned regions, and show synteny or gene rearrangements. The tet(W) gene is represented in blue in the center of the figure

Detection of the ICE_RbtetW_07 in B. schinkii DSM 10518

To confirm the presence of the ICE carrying the tet(W) genes in rumen bacteria, Blautia schinkii DSM 10518 was grown in the batch culture, and a fragment of 4794 bp covering the region from the virD4 gene to the tet(W) gene was PCR amplified from the genomic DNA (Fig. 4). The amplicon was subjected to shotgun sequencing performed on the MiSeq with 300 cycles using the next-Flex Illumina workflow, and the assembled reads confirmed the genetic organization of the ICE (type IV secretion system gene adjacent to the tetracycline-resistance gene) predicted in the Blautia schinkii DSM 10518 genome (accession number PRJNA223460, [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/223460]) with 100% of nucleotide identity and 99.7% of coverage (Supplementary Data 2).

Fig. 4.

PCR detection of the ICE_RbtetW_07 in Blautia schinkii DSM 10518. The expected amplicon size of the region from the virD4 gene to the tet(W) gene was 4794 pb. L: 1 kb HyperLadder, N: negative sample, and B: Blautia schinkii DSM 10518

Selection pressure analysis of tet resistance genes

Because the tetracycline-resistance genes tet(W), tet(Q), and tet(O) were highly abundant and broadly distributed in the genomes of ruminal bacteria, we investigated if these genes are evolvable and if genetic variants are being selected for in the genomes of ruminal bacteria. For this purpose, the number of non-synonymous per synonymous substitutions (dN/dS ratio) was calculated to determine the codon substitution rate, which could indicate the evolution of the gene in ruminal microbial genomes. Our analysis confirmed the presence of positive selection pressure in the tet(W) gene, with a dN/dS ratio > 1 for 36 out of the 639 amino acid residues in the protein (Fig. 5a). Sites showing positive selection were mainly clustered in three distinct regions of the TetW protein, located between amino acids positions 141–265, 310–341, and 600–639, with an average dN/dS ratio per site of 1.9, 2.6, and 3.1, respectively. For the tet(Q) and tet(O) genes, our analysis indicated 25 and 17 amino acid sites with positive selection pressure, respectively (Fig. 5b, c). Nonetheless, the overall dN/dS ratio calculated for these genes was <1, and the likelihood ratio test data (LRT) for the substitution models did not present statistically significant difference at 95% confidence level, indicating absence of positive selection for tet(Q) and tet(O) genes. To confirm that the tet(W) gene is under positive selection, neutrality tests were applied in these ARG sequences. The results of Tajima’s D (D = −1.65) and Fu and Li test (D* = −2.22. p < 0.05; F* = −2.39, p < 0.05) corroborate with our previous findings.

Fig. 5.

Selection pressure analysis in tetracycline-resistance genes. The dN/dS ratio was calculated for the tet(W) (a), tet(Q) (b), and tet(O) genes (c) using JCoDA. The lines in each panel represent dN/dS scores by site. The phylogenetic tree generated by JCoDA for dN/dS analysis was reconstructed using the aligned protein sequences of the ARGs and Maximum-Likelihood approach with 100 replicates. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

Confirmation of resistance phenotypes

To validate the resistance phenotype that was computationally predicted in the genomes of ruminal bacteria, 26 pure cultures matching the genomes analyzed in silico were selected for further in vitro characterization. Our in silico analysis predicted 57 resistance determinants in the ruminal bacteria that were selected for in vitro testing. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC values) were determined using the Epsilometer test (E-test) method18, and 18 resistance phenotypes were confirmed in vitro (Supplementary Table 1). From this, eight ARGs (~44.0%) were detected/confirmed both in silico and in vitro by all approaches used in this study (Supplementary Fig. 7). ARG-ANNOT predicted 14 ARGs in the 26 cultures of ruminal bacteria tested in vitro, and 10 resistance phenotypes (71.4%) were confirmed in the E-test assays. ResFinder and Resfams predicted 14 and 53 ARGs in the bacterial cultures, and resistance to 9 (64.3%) and 17 (32.1%) of these antibiotics were confirmed phenotypically (Supplementary Fig. 7). Therefore, resistance phenotypes predicted by ResFinder and ARG-ANNOT agreed, for the most part, with the in vitro results, while Resfams predicted several resistance mechanisms that could not be confirmed by other computational or in vitro methodologies used in this study.

In addition, tetracycline resistance was detected simultaneously by at least three approaches in 69% of the genomes and bacterial cultures, providing further evidence that tetracycline resistance is widespread in the rumen ecosystem. Moreover, some resistance phenotypes were confirmed by our in vitro assays even when the presence of resistance determinants were predicted by only one bioinformatic tool. This was observed for vancomycin resistance in Clostridium and Lachnoclostridium strains and in Lactobacillus ruminis DSM 20403, for beta-lactams in Mitsuokella jalalundinii DSM 13811 and Selenomonas ruminantium DSM 2872, for aminoglycosides in Bifidobacterium pseudolongum DSM 20092 and for macrolides in Prauserella rugosa DSM 43194 (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Concordance between antibiotic resistance detected in silico and in vitro. Twenty six bacteria were analyzed both in silico and in vitro in this study. Colors represent the approach used to predict the ARG or to detect the resistance phenotype of each bacteria. BLA (beta-lactam); AMG (aminoglycoside); TET (tetracycline); VAN (vancomycin); CHL (Chloramphenicol); MAC (macrolide); CLD (clindamycin)

Expression of ARGs in metatranscriptomes

To confirm if the ARGs detected in ruminal microbial genomes are expressed in the rumen ecosystem, we aligned the genes conferring resistance to the five most abundant antibiotic classes (aminoglycoside, beta-lactam, macrolide, tetracycline, and vancomycin) detected in rumen bacterial genomes to 15 rumen metranscriptome data sets of dairy and beef cattle and sheep. At least one resistance gene from each antibiotic class was expressed in one or more metatranscriptomes (Fig. 7). In general, tetracycline-resistance genes presented the highest level of expression, mainly the tet(O), tet(Q), tet(W), and tet(37) gene. Moreover, individual genes varied in their expression levels between different data sets, being more prevalent in sheep and beef cattle. Some of the ARGs identified in the ruminal microbial genomes, such as strA, cepA, ermB, tet(B), and vanC, among others, were not expressed in any of the metatranscriptome data sets investigated in this study (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Expression levels (RPKM) of ARGs in ruminal metatranscriptomes. Beef and dairy cattle and sheep data sets were analyzed, and only ARGs that were expressed in at least one metatranscriptome are represented. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

Discussion

The hypothesis that livestock animals represent a reservoir of ARGs is not new, and previous studies have demonstrated that bacteria isolated from fecal samples of monogastrics and ruminants harbor genetic elements that can confer resistance to clinically used antibiotics19. However, less attention has been given to the occurrence of ARGs in the rumen ecosystem and their potential to be transferred to commensal and pathogenic bacteria. Microorganisms colonizing the rumen also disseminate to the environment through animal saliva during rumination and due to the flow of rumen microbial biomass to the omasum, abomasum and to the distal parts of the GIT, being released through fecal discharge into the soil20.

In this work, we investigated the occurrence and distribution of ARGs in hundreds of ruminal microbial genomes made available through the Hungate1000 project12. Our results indicate that ARGs are widely distributed among ruminal bacteria, with genes conferring resistance to tetracycline being frequently detected in the genomes of several species. The regions flanking the tetracycline-resistance genes showed a conserved pattern in an apparently novel integrative and conjugative element (ICE), suggesting dissemination of antibiotic resistance through horizontal gene transfer in the rumen microbiome. In addition, we show evidence of positive selective pressure on the tet(W) gene, which may contribute to the selection of genetic variants of this gene, conferring ribosome protection against tetracycline antibiotics in ruminal bacteria.

Tetracyclines are broad-spectrum antibiotics that inhibit protein synthesis in susceptible bacteria21 and have been used in human and veterinary medicine to fight bacterial infections and to promote the growth of food-producing animals, improving feed efficiency and animal performance22. The growth-promoting activity of tetracyclines in livestock was first reported in 1949 when feeds supplemented with dried Streptomyces aureofaciens mash were administrated to poultry23. However, the long-term use of subtherapeutic doses of tetracyclines has been associated with increased levels of bacterial resistance in the GIT of food-producing animals24, which led countries such as the USA and members of the European Union to ban the use of tetracyclines as growth promoters since 197525. The prevalence of tetracycline-resistance genes among ruminal bacteria has a potential negative impact in livestock health given that tetracyclines account for up to 24% of the antibiotics used to treat respiratory, uterine, or locomotion diseases in Europe26.

In our study, tet(W), tet(Q), and tet(O) were the main tetracycline-resistance genes identified by ResFinder, but tet(W) was the most abundant gene, being distributed in 28 genomes of ruminal bacteria with high similarity of nucleotide sequences. Since ResFinder is an online platform that uses whole-genome sequencing data to identify acquired AMR genes in bacteria13, the tet(W) gene was selected for further analysis with an aim to investigate if it could be horizontally transferred among ruminal bacteria.

Our analyses suggest that the tet(W) gene of several species of ruminal bacteria are located on an ICE with a unique modular pattern, not previously reported for tetracycline resistance (ICE_RbtetW_07). The organization of the ICE structure is characterized by a core region containing essential modules for conjugation, recombination, and regulation27. The conjugation machinery often contains relaxases and secretion systems to mediate the transfer of DNA between donor and recipient cells. The recombination module usually contains genes encoding integrases, excisionases, and recombinases, while genes encoding proteins involved in DNA transcription are found in the regulation module. Moreover, several accessory genes, including methyltransferases, transposons, phages, and plasmid related proteins, in addition to the ARGs, can be present in an ICE structure27. At least one essential gene from each module and several accessory genes were detected in the flanking region of the tet(W) gene in seven ruminal microbial genomes analyzed in this study, suggesting that ICEs could be mediating the horizontal transfer of tetracycline-resistance genes between ruminal bacteria. Some essential genes of integrative and conjugative elements were also found in other genomes of rumen bacteria harboring the tet(W) gene, but the genetic structure of these elements appeared incomplete. The structure of ICE_RbtetW_07 was conserved in the genomes of ruminal bacteria, and the presence of the tet(W) gene on the ICE was confirmed in the genome of Blautia schinkii DSM 10518 by PCR amplification and shotgun sequencing. ICEs are known to be frequently transferred between distant bacterial taxa28, and our analysis suggest that these genetic elements might have great mobility in the rumen ecosystem. If this is indeed the case, there is a potential threat of these genetic elements to be transferred to bacterial pathogens in the GIT of ruminants and into the environment.

Some groups of microorganisms, such as the Enterobacteriaceae, are frequently associated with the horizontal transfer of ARGs29,30. The enrichment of ARGs appears to be a common feature in the mobile resistome of Proteobacteria from both the animal and the human gut microbiome31. This may be associated with the frequent use of antibiotics targeting Enterobacteriaceae to control infections in the respiratory, urinary, and GIT of humans and livestock, thus selecting for resistant strains5. Our in silico results demonstrated that members of the Proteobacteria phylum that inhabit the rumen can harbor multiple ARGs, as exemplified by the genome of E. coli PA-3, a ruminal isolate that contains five genes conferring resistance to four distinct antibiotics. Although generic Escherichia coli populations are often not so abundant in the rumen (<106 cells/ml), cattle are considered a natural reservoir for pathogenic strains of E. coli32,33. In addition, management and nutritional practices, such as feeding the animals a high-grain diet, can cause significant increases in ruminal and fecal populations of E. coli and influence the abundance and diversity of ARGs in the ruminal resistome33,34.

Furthermore, a complete operon for vancomycin resistance (vanC) was found in the genomes of Enterococcus casseliflavus and in Enterococcus gallinarum SKF1, which makes these species intrinsically resistant to this antibiotic35. Vancomycin is one of the last-option antibiotic used to treat infections caused by Gram-positive bacteria36, but little is known about vancomycin resistance in ruminal bacteria. Our analyses predicted resistance to vancomycin in Clostridium, Lachnoclostridium, and Blautia, and in vitro experiments confirmed these phenotypes in Blautia schinkii DSM 10518, Lachnoclostridium aerotolerans DSM 5434, Clostridium intestinale DSM 6191, and Clostridium lundense DSM 17049. However, our transcriptomic analysis indicated that the expression of vancomycin-resistance genes in the rumen microbiome is low. In addition, vancomycin has limited use for therapeutic purposes in animals, and vancomycin analogs have been restricted as growth promoters in livestock36.

Overall, our in vitro assays confirmed 31.6% of the resistance phenotypes predicted by computational approaches. Nonetheless, 64.3% and 71.4% of the resistance phenotypes based on the ARGs predicted by ResFinder and ARG-ANNOT, respectively, were confirmed in vitro. These results show concordance between these different approaches, despite the fact that some predicted ARGs might not be functional in vitro. In addition, our transcriptomic analyses showed higher expression of tetracycline-resistance genes and low expression of other classes or ARGs (such as beta-lactams and aminoglycosides) in the rumen data sets, which also agreed with the resistance phenotype observed in vitro for the pure cultures of ruminal bacteria. Therefore, the results presented here, based on genomic, transcriptomic and phenotypic data, increase the confidence that ARGs are distributed among different species of ruminal bacteria, and that these genes are expressed by members of the microbial community in vivo. Nonetheless, additional studies will be needed to evaluate the effects of animal ageing, production systems, and nutritional practices, including antibiotic feeding, on the expression, and potential transit of the ARGs detected in this study across the GI tract of cattle.

Taken together, our results provide insights that characterize the antibiotic resistance in species of ruminal bacteria. Our findings demonstrate that ARGs, in particular the genes for tetracycline resistance, are prevalent among ruminal bacteria and subjected to positive selection pressure. Moreover, analysis of the flanking regions of the tet(W) genes provided evidence that this gene can be disseminated horizontally through ICE transfer. Given the fact that the rumen ecosystem also harbor a highly dense and diverse microbiota that maintain complex ecological associations, and the capacity of microorganisms to exchange DNA through direct (conjugation) and indirect mechanisms (transformation, transduction), the GIT of ruminants should be considered as a relevant source of antibiotic-resistance genes. The evidence of a new ICE (ICE_RbtetW_07) carrying the tet(W) gene emphasizes this idea and presents a risk for both animal and human health, due to the capacity of these genetic elements to disseminate into the environment. This hypothesis is also supported by the observation of non-phylogenetically related bacteria harboring the same resistance genes, and the expression of the same ARGs in ruminal metatranscriptomes data sets from beef and dairy cattle and sheep. In addition, our results highlight the importance of using multiple computational tools to search for ARGs in genomic data and demonstrate the relevance to validate these results in vitro and/or in vivo.

Methods

Collection of genomic data and identification of ARGs

The sequence files of 435 ruminal microbial genomes (425 bacteria and 10 archaea), from the Hungate1000 project, were downloaded in FASTA format from the NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome) and the JGI (Joint Genome Institute, http://genome.jgi.doe.gov) websites (Supplementary Data 3). Putative ARGs in the bacterial and archaeal genomes were predicted using three bioinformatics tools (ResFinder v2.1, Resfams v1.2, and ARG-ANNOT Nt V3, see below) that vary in sensitivity and specificity and apply distinct databases and search methods to detect putative ARGs in nucleotide sequences.

We initially prospected the bacterial and archaeal genomes using the ResFinder v2.1 database (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/ResFinder/)13 against all antibiotic classes available for analysis of acquired ARGs, which included aminoglycosides, beta-lactams, colistin, fluoroquinolones, fosfomycin, fusidic acid, glycopeptides, MLS (macrolides, lincosamides, and streptogramins), nitroimidazole, oxazolidinone, phenicols, rifampicin, sulfonamides, tetracyclines, and trimethoprim. For homology-based screening, the minimum gene identity and sequence length were set to 70 and 60%, respectively, in relation to the reference-resistance gene.

The software Resfams v1.2 was used to search for conserved structural domains of antibiotic-resistance function in protein sequences of ruminal bacteria14. The protein sequences of the analyzed genomes were downloaded in the FASTA format from the NCBI or JGI websites and when these sequences were not found, the online interface Prodigal v1.2 (http://compbio.ornl.gov/prodigal/server.html) was used to convert nucleotide to protein sequences using the Standard Bacteria/Archaea translation table code.

Genomes of ruminal microorganisms were also analyzed using the ARG-ANNOT database (http://en.mediterranee-infection.com/article.php?laref=283&titre=arg-annot-)15. Sequences of the ARGs in the ARG-ANNOT database (ARG-ANNOT Nt V3) were used for similarity analysis against the ruminal microbial genomes using BLASTn37 on the Galaxy platform38. The alignment parameters were minimum sequence identity of 70%, sequence length cutoff of 60%, and E-value < 10–6.

Phylogenetic analysis and distribution of ARGs

To evaluate if the ARGs grouped according to the evolutionary history of the microbial species, phylogenetic trees were reconstructed using the 16S rRNA gene sequences from the genomes analyzed in this study. The 16S rRNA gene sequences were obtained from the Hungate1000 collection12. Next, all the sequences were organized in a single txt file and aligned using the RDP Release 11.5 aligner in the Ribosomal Database Project website (RDP, https://rdp.cme.msu.edu/)39. FastTree v2.1 (http://www.microbesonline.org/fasttree/)40 was used to infer Approximately-Maximum-Likelihood phylogenetic trees using default settings. The generated output file (.tree) was visualized and annotated on the Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) interface v4 (https://iTOL.embl.de/)41.

To evaluate sequence conservation of the ARGs that were identified in silico as described above, the sequences of the most frequent genes conferring resistance were extracted from the ruminal microbial genomes, and aligned as described below. To extract the sequences of the resistance genes, all genomes were annotated by Prokka v1.1242 using the Galaxy platform (minimum contig size of 200 and E-value < 10–6). To obtain the location of the resistance genes in the bacterial genomes, the ResFinder v2.1 database was aligned against the annotated genomes using the BLASTn tool on the Galaxy platform. Minimum query coverage and sequence identity were 60 and 70%, respectively, with a threshold E-value < 10–6. The sequence of the resistance genes identified in the previous alignment were extracted using the SAMtools software v1.9 (http://SAMtools.sourceforge.net/)43, and the most abundant ARGs were aligned using MUSCLE version 3.8.3144. The phylogenetic reconstruction was based on the Maximum-Likelihood method using FastTree v2.1, and iTOL v4 graphical interface was used to represent the phylogenetic trees, as described above.

Genetic context of ARGs

To assess potential mechanisms of ARG mobility, the genetic elements flanking the resistance genes in a scaffold were investigated using the software Artemis45. When these flanking elements were annotated as hypothetical protein, sequence function was predicted on the UNIPROT website (http://www.uniprot.org/)46, using BLASTn, UniProtKB as the target database and default settings. Putative mobile genetic elements flanking the resistance genes were searched using different computational tools. ISfinder (https://www-is.biotoul.fr/)47 was used to screen for transposons and/or integrons, and phage sequences were confirmed using PHASTER (http://phaster.ca/)48. The genomes that harbored proteins with predicted plasmid functions near the resistance genes were further analyzed against the Enterobacteriaceae and Gram-positive database of PlasmidFinder 2.0 (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/PlasmidFinder/)49, using a threshold for minimum sequence identity of 70% and minimum coverage of 60%. Finally, ICEberg 2.0 (http://db-mml.sjtu.edu.cn/ICEberg/)17 was used to identify ARGs carried by integrative and conjugative elements (ICE). Scaffolds harboring selected ARGs were used as query sequences (FASTA format) in the WU-BLAST2 search tool in ICEberg, using BLASTn as the search program and ICE nucleotide sequence as the sequence database. All the other parameters were kept as default settings.

Conservation and in vitro confirmation of a novel ICE

To evaluate the genetic conservation of the integrative and conjugative elements identified in the genomes of ruminal bacteria, the nucleotide sequences of these ICEs were aligned using progressiveMAUVE50. In addition, a phylogenetic tree was reconstructed in MEGA X software using Muscle to compare the sequences of the novel ICE with other ICEs available in the ICEberg database. Phylogenetic reconstruction was performed using the Maximum-Likelihood method with 100 replicates.

To confirm the presence of a novel ICE in the genome of ruminal bacteria, PCR amplifications were performed using Blautia schinkii DSM 10518. Primers were designed to amplify a 4794 pb DNA fragment that included the region from gene virD4 to gene tet(W). Briefly, the bacteria was grown in anaerobic media at 39 °C for 72 h. Genomic DNA was extracted using the Qiagen DNA extraction kit (Manchester, UK). PCR amplification of the region of interest was carried out in 25 µl volumes as follows: 12.5 µl 2x MyTaq HS Red Mix, 1 µl each of 20 µM primers drawn in this study (RbtetW07_F: ATGAAAAAGCAGCTTGACATCAAAAAGC and RbtetW07_R: TTACATTACCTTCTGAAACATATGGCGC), 8 µl of nuclease-free water, and 2.5 µl of 50 ng template DNA. The cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 60 s, 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s, annealing at 58 °C for 15 s, and extension at 72 °C for 3 min, and a final extension step at 72 °C for 5 min. The size and integrity of PCR products were visualized and assessed by agarose gel electrophoresis using a 1% (w/v) agarose in TAE buffer (40 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 20 mM acetic acid, 1 mM EDTA, BioRad Ltd., Hemel Hempstead, UK). The PCR product was subjected to shotgun sequencing performed on the MiSeq with 300 cycles using the next-Flex Illumina workflow at the Queen’s University of Belfast Genomics Core Technology Unit (Belfast, UK) to confirm the presence of the predicted integrative and conjugative element. Quality filtering of the reads was performed using Trimmomatic software v0.2751, and sequences were assembled using SPAdes 3.10.152. The sequence was aligned to the ICE coding sequence in the genome of Blautia schinkii DSM 10518, using Clustal Omega53.

Selective pressure on identified ARGs

Sequences of the most prevalent ARGs detected in ruminal microbial genomes were selected to evaluate if these genes are under selection pressure. Selective pressure on the ARGs was estimated by the number of non-synonymous and synonymous substitutions (dN/dS) using the software JCoDA54. JCoDA uses ClustalW to align the nucleotide sequences and Phylogenetic Analysis using Maximum Likelihood (PALM) to calculate the dN/dS ratio. Analyses were performed using nucleotide sequences in the FASTA format as input sequences and the universal (default) genetic translation code. The alignment option was set to ClustalW, and phylogenetic trees were reconstructed by the Maximum-Likelihood method with 100 replicates using protein sequences in the Phylip-sequential format. The dN/dS was calculated by site (amino acid) using the Bayes Empirical Bayes (BEB) model, which takes into account the uncertainties of model parameters, avoiding the generation of false positives54. The selective pressure on the antibiotic-resistance genes were confirmed by two neutrality tests, the Tajima test (performed in MEGAX55) and Fu and Li test (DnaSP v656).

In vitro analysis of the predicted resistance phenotypes

To evaluate if the ARGs detected in the ruminal microbial genomes conferred the predicted resistance phenotype in vivo, 26 cultures of ruminal bacteria that had their genomes analyzed for the presence of ARGs were tested in vitro to confirm these phenotypes. Cultures stored at −80 °C were activated twice in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth at 39 °C for 24 h under anaerobic conditions before each experiment. For the antibiotic susceptibility test, the optical density (OD600nm) of the cultures was adjusted to obtain a cell count of ~108 CFU ml−1 (equivalent to 0.5 McFarland scale). Subsequently, cultures were spread on the surface of solid BHI media using swabs. E-test strips (Biomérieux, Basingstoke, UK; Fannin, Dublin, Ireland) of the antibiotics to be tested were distributed on the surface of the inoculated medium, and the plates were incubated anaerobically at 39 °C for another 24 h. Only antibiotics to which resistance was predicted in silico were evaluated in vitro using pure cultures of ruminal bacteria. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of each antibiotic was determined at the intersection of the inhibition zone with the E-test strips57. All experiments were performed with three biological replicates. Reference values from the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) breakpoint table were used to interpret the MIC results58. In the case of a few antibiotics where breakpoint values were not available for the tested species, MIC interpretations were based on breakpoint values published for the most closely related organism.

Metatranscriptomic analyses

The metatranscriptome data sets were downloaded in the FASTQ format from the NCBI Sequence Read Archive SRA (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra)59. Fifteen ruminal data sets representing cattle from distinct production systems (dairy and beef) and from sheep were selected for the analysis (Supplementary Table 2). FastQC software v0.11.5 (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc) was initially applied for quality control checks on raw sequence data using a Phred quality score of 20 to filter high-quality bases. However, because most reads were discarded using this criteria, gene expression was evaluated using raw sequence data.

In this study, the most abundant group of ARGs identified in the ruminal microbial genomes was selected to verify their expression in the metatranscriptomic data sets. These genes were predicted to encode resistance to aminoglycosides (aadE, ant(6)-Ia, aph(3’)-III, strA, strB), beta-lactams (cepA, blaACl−1, blaSED1, blaDHA-2, blaZ), macrolides (ermB, erm(G), mef(A), Isa(A), IsaC), tetracycline (tet(32), tet(40), tet(A), tetA(P), tet(B), tetB(P), tet(D), tet(J), tet(M), tet(O), tet(Q), tet(W), tet(37), and vancomycin (vanC, vanD, vanH-D, vanR-C, vanR-D, vanS-C, vanS-D, vanT-C, vanX-D, vanXY-C, vanY-D, vanZ-F). The Bowtie2-build tool was used to index the DNA sequences of the resistance genes, while Bowtie260 was employed to align these sequences to the metatranscriptomic data sets. The expression level of each gene was calculated by the number of uniquely mapped reads per kilobase in a gene per million mappable reads (RPKM)61 using a cutoff value of 0.362.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES; Brasília, Brazil), Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG; Belo Horizonte, Brazil), and the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq; Brasília, Brazil). We are also grateful for RCUK Newton Institutional Link Funding (172629373).

Author contributions

Y.N.V.S., H.C.M., and S.A.H. conceived the project. Y.N.V.S. and A.J.S.M. completed the laboratory work under the supervision of H.C.M. and S.A.H. Y.N.V.S., M.F.S., and F.G.S. analyzed the data and generated figures. S.A.H. provided the anaerobic cultures analyzed in the study. L.B.O. assisted Y.N.V.S. with the in vitro experiments. L.B.O., M.F.S., and S.A.H. provided valuable ideas into the project from the time of conception. Y.N.V.S. and H.C.M. wrote the paper with imput from all co-authors.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are included in the paper and/or its Supplementary Information files. Data underlying Figs. 5, 7 and Supplementary Figs. 1, 2, and 7 are provided as a Source Data file.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Sharon Ann Huws, Email: s.huws@qub.ac.uk.

Hilário Cuquetto Mantovani, Email: hcm6@ufv.br.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-019-13118-0.

References

- 1.O’Neill, J. Tackling drug-resistant infections globally: final report and recommendations. https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/160518_Final%20paper_with%20cover.pdf (2016).

- 2.Ventola CL. The antibiotic resistance crisis: part 2: management strategies and new agents. P. T. 2015;40:344–352. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elliott, K. A., Kenny, C. & Madan, J. A global treaty to reduce antimicrobial use in livestock. https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/global-treaty-reduce-antimicrobial-use-livestock.pdf (2017).

- 4.Aarestrup FM. The livestock reservoir for antimicrobial resistance: a personal view on changing patterns of risks, effects of interventions and the way forward. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2015;370:1–13. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hitch TCA, Thomas BJ, Friedersdorff JCA, Ougham H, Creevey CJ. Deep sequence analysis reveals the ovine rumen as a reservoir of antibiotic resistance genes. Environ. Pollut. 2018;235:571–575. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huws SA, et al. Addressing global ruminant agricultural challenges through understanding the rumen microbiome: past, present, and future. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:2161. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubino F, Carberry C, Kenny D, McCabe MS, Creevey CJ. Divergent functional isoforms drive niche specialisation for nutrient acquisition and use in rumen microbiome. ISME J. 2017;11:932–944. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shoemaker NB, Wang GR, Salyers AA. Evidence for natural transfer of a tetracycline resistance gene between bacteria from the human colon and bacteria from the bovine rumen. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1992;58:1313–1320. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.4.1313-1320.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shterzer N, Mizrahi I. The animal gut as a melting pot for horizontal gene transfer. Can. J. Microbiol. 2015;61:603–605. doi: 10.1139/cjm-2015-0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toomey N, Monaghan A, Fanning S, Bolton D. Transfer of antibiotic resistance marker genes between lactic acid bacteria in model rumen and plant environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;75:3146–3152. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02471-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cameron A, McAllister TA. Antimicrobial usage and resistance in beef production. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2016;7:1–22. doi: 10.1186/s40104-016-0127-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seshadri R, et al. Cultivation and sequencing of rumen microbiome members from the Hungate1000 collection. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018;36:359–367. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zankari E, et al. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012;67:2640–2644. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gibson MK, Forsberg KJ, Dantas G. Improved annotation of antibiotic resistance determinants reveals microbial resistomes cluster by ecology. ISME J. 2015;9:207–216. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta SK, et al. ARG-ANNOT, a new bioinformatic tool to discover antibiotic resistance genes in bacterial genomes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014;58:212–220. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01310-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Awady R, et al. The role of eukaryotic and prokaryotic ABC transporter family in failure of chemotherapy. Front. Pharm. 2016;7:1–15. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bi D, et al. ICEberg: a web-based resource for integrative and conjugative elements found in Bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D621–D626. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sader HS, Pignatari AC. E test: a novel technique for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Sao Paulo Med. J. 1994;112:635–638. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31801994000400003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karikari AB, Obiri-Danso K, Frimpong EH, Krogfelt KA. Antibiotic resistance of Campylobacter recovered from faeces and carcasses of healthy livestock. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017;2017:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2017/4091856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muurinen J, et al. Influence of manure application on the environmental resistome under finnish agricultural practice with restricted antibiotic use. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017;51:5989–5999. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b00551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chopra I, Roberts M. Tetracycline antibiotics: mode of action, applications, molecular biology, and epidemiology of bacterial resistance. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2001;65:232–260. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.65.2.232-260.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daghrir, R. & Drogui, P. Tetracycline antibiotics in the environment: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 11, 209–227 (2013).

- 23.Stokstad EL, et al. The multiple nature of the animal protein factor. J. Biol. Chem. 1949;180:647–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Michalova E, Novotna P, Schlegelova J. Tetracyclines in veterinary medicine and bacterial resistance to them. Vet. Med. 2004;49:79–100. doi: 10.17221/5681-VETMED. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwarz S, Chaslus-Dancla E. Use of antimicrobials in veterinary medicine and mechanisms of resistance. Vet. Res. 2001;32:201–225. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2001120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Briyne N, Atkinson J, Pokludova L, Borriello SP. Antibiotics used most commonly to treat animals in Europe. Vet. Rec. 2014;175:325. doi: 10.1136/vr.102462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cury J, Touchon M, Rocha EPC. Integrative and conjugative elements and their hosts: composition, distribution and organization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:8943–8956. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cury J, Oliveira PH, de la Cruz F, Rocha EPC. Host range and genetic plasticity explain the co-existence of integrative and extrachromosomal mobile genetic elements. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018;35:2230–2239. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Colavecchio A, Cadieux B, Lo A, Goodridge LD. Bacteriophages contribute to the spread of antibiotic resistance genes among foodborne pathogens of the Enterobacteriaceae family—a review. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:1–13. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rozwandowicz M, et al. Plasmids carrying antimicrobial resistance genes in Enterobacteriaceae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018;73:1121–1137. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu Y, et al. The bacterial mobile resistome transfer network connecting the animal and human microbiomes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016;82:6672–6681. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01802-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Callaway TR, Elder RO, Keen JE, Anderson RC, Nisbet DJ. Forage feeding to reduce preharvest Escherichia coli populations in cattle, a review. J. Dairy Sci. 2003;86:852–860. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(03)73668-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Diez-Gonzalez F, Callaway TR, Kizoulis MG, Russell JB. Grain feeding and the dissemination of acid-resistant Escherichia coli from cattle. Science. 1998;281:1666–1668. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5383.1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Auffret MD, et al. The rumen microbiome as a reservoir of antimicrobial resistance and pathogenicity genes is directly affected by diet in beef cattle. Microbiome. 2017;5:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0378-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gold HS. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci: mechanisms and clinical observations. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001;33:210–219. doi: 10.1086/321815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wijesekara PNK, Kumbukgolla WW, Jayaweera J, Rawat D. Review on usage of vancomycin in livestock and humans: maintaining its efficacy, prevention of resistance and alternative therapy. Vet. Sci. 2017;4:1–11. doi: 10.3390/vetsci4010006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Afgan E, et al. The Galaxy platform for accessible, reproducible and collaborative biomedical analyses: 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W3–W10. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cole JR, et al. Ribosomal database project: data and tools for high throughput rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D633–D642. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. FastTree 2 – approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PloS ONE. 2010;5:1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: an online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W242–W245. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li H, et al. The sequence alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carver T, Harris SR, Berriman M, Parkhill J, McQuillan JA. Artemis: an integrated platform for visualization and analysis of high-throughput sequence-based experimental data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:464–469. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.UniProt Consortium, T. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;45:D158–D169. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Siguier P, Perochon J, Lestrade L, Mahillon J, Chandler M. ISfinder: the reference centre for bacterial insertion sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D32–D36. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arndt D, et al. PHASTER: a better, faster version of the PHAST phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W16–W21. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carattoli A, et al. In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014;58:3895–3903. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02412-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Darling ACE, Mau B, Blattner FR, Perna NT. Mauve: multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res. 2004;14:1394–1403. doi: 10.1101/gr.2289704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bankevich A, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012;19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sievers F, Higgins DG. Clustal Omega, accurate alignment of very large numbers of sequences. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014;1079:105–116. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-646-7_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Steinway SN, Dannenfelser R, Laucius CD, Hayes JE, Nayak S. JCoDA: a tool for detecting evolutionary selection. BMC Bioinforma. 2010;11:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018;35:1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rozas J, et al. DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017;34:3299–3302. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nagy E, Justesen US, Eitel Z, Urban E, Infection ESGOA. Development of EUCAST disk diffusion method for susceptibility testing of the Bacteroides fragilis group isolates. Anaerobe. 2015;31:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.European Committee of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. http://www.eucast.org (2017).

- 59.Leinonen R, Sugawara H, Shumway M. & International Nucleotide Sequence Database, C. The sequence read archive. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D19–D21. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mortazavi A, Williams BA, McCue K, Schaeffer L, Wold B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:621–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Warden CD, Yuan Y-C, Wu X. Optimal calculation of RNA-Seq fold-change values. Int. J. Comput. Bioinfo. Silico Model. 2013;2:285–292. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are included in the paper and/or its Supplementary Information files. Data underlying Figs. 5, 7 and Supplementary Figs. 1, 2, and 7 are provided as a Source Data file.