Abstract

Background

There are increasing rates of internalising difficulties, particularly anxiety and depression, being reported in children and young people in England. School-based, universal prevention programmes are thought to be one way of helping tackle such difficulties. This protocol describes a four-arm cluster randomised controlled trial, investigating the effectiveness of three different interventions when compared to usual provision, in English primary and secondary pupils. The primary outcome for Mindfulness and Relaxation interventions is a measure of internalising difficulties, while Strategies for Safety and Wellbeing will be examined in relation to intended help-seeking. In addition to the effectiveness analysis, a process and implementation evaluation and a cost-effectiveness evaluation will be undertaken.

Methods and analysis

Overall, 160 primary schools and 64 secondary schools will be recruited across England. This corresponds to 17,600 participants. Measures will be collected online at baseline, 3–6 months later, and 9–12 months after the commencement of the intervention. An economic evaluation will assess the cost-effectiveness of the interventions. Moreover, a process and implementation evaluation (including a qualitative research component) will explore several aspects of implementation (fidelity, quality, dosage, reach, participant responsiveness, adaptations), social validity (acceptability, appropriateness and feasibility), and their moderating effects on the outcomes of interest, and perceived impact.

Discussion

This trial aims to address important questions about whether schools’ practices around the promotion of mental wellbeing and the prevention of mental health problems can: (1) be formalised into feasible and effective models of school-based support and (2) whether these practices and their effects can be sustained over time. Given the focus of these interventions on mirroring popular practice in schools and on prioritising approaches that present low-burden, high-acceptability to schools, if proved effective, and cost-effective, the findings will indicate models that are not only empirically tested but also offer high potential for widespread use and, therefore, potentially widespread benefits beyond the life of the trial.

Trial registration

ISRCTN16386254. Registered on 30 August 2018.

Keywords: Adolescent, Young person, Children, Cluster randomised controlled trial, Mental health, Wellbeing, School-based

Background

Well-established estimates in the United Kingdom suggest that one in eight children and young people experience mental health problems [1] and that these may be with associated with costly long-term consequences [2–4]. In the absence of effective or widespread processes for identifying those who experience mental health problems, or those likely to be at risk of such difficulties in the future, there has been an increasing focus on universal approaches to supporting children’s mental health and wellbeing. These universal interventions can act as a means to prevent the emergence of mental health problems and to intervene early in the emergence of any difficulties [5, 6]. Schools are often viewed as a universal point of access to children and young people, offering an important opportunity to embed prevention and early intervention programmes [7, 8]. A number of reviews point to the effectiveness of school-based mental health programmes for the prevention and early intervention [9], especially for depression [10], anxiety [11] and behaviour problems [12]. While existing evidence makes a good case for the effectiveness of universal school-based interventions [11, 13], a number of areas require further clarity.

Firstly, with the exception of a small number of UK-based programmes [14, 15], the basis for current practice in the UK is often research evidence originating from other countries, predominantly the US, with social and emotional learning (SEL) programmes such as Incredible Years [16] and PATHS [17] being highly popular. Other than the Incredible Years programme, which has been rigorously tested in a UK setting [18], rigorous and consistent evidence for SEL programmes’ effectiveness is sparse. Additionally, there are indications that some programmes do not always translate well when implemented beyond their countries of origin [19, 20].

Secondly, a scoping review of existing practice indicates a heterogeneous range of mental health support offered in schools, much of which is either novel, not based on tried and tested programmes, or involves a high level of adaptation from existing evidence-based approaches [21, 22]. However, reasons for adaptation are often logical; these programmes, which have not been designed for the UK school context, frequently require tailoring for suitability and feasibility, which may be beneficial to outcomes. However, such adaptation also carries a risk of significantly ‘watered-down’ implementation, which limits impact [23].

Three interventions were selected by the Department for Education in England to be developed for the current trial. The basis for selection was that these either: (a) were popular approaches being adopted by schools and, therefore, likely to have high acceptability and feasibility, as well as potential for wider adoption if found to be effective; or (b) showed early promise but currently lacked a robust evidence base, specifically regarding implementation in schools. The interventions were: (1) Mindfulness Practices, (2) Relaxation and (3) Strategies for Safety and Wellbeing, based on the principles of ‘Protective Behaviours’(PB). These interventions were piloted in a feasibility study [24] prior to this cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT). Learning from this resulted in: (a) more activities being provided for each intervention, (b) distinct age-appropriate resources for primary or secondary school teachers to use and deliver and (c) a greater distinction between ‘mindfulness practices’ and ‘relaxation’.

Mindfulness Practices

Mental health interventions incorporating mindfulness elements have proven effective in treating and preventing various psychological and physical difficulties [25]. Most research that has been conducted thus far included adult samples; however, there is increasing evidence for the beneficial effects of mindfulness-based interventions (MBI) in youth [26, 27]. More specifically, MBI in youth have been shown to significantly increase positive affect, optimism, attention and social-emotional competence while decreasing dysfunctional behaviour and emotion dysregulation [28]. A number of recent reviews of MBIs in youth have highlighted their impact on cognitive and socio-emotional outcomes [29] including mental health and positive wellbeing, noting that the effects appear to be strongest for emotional problems. Although mindfulness has a rapidly growing evidence base, and a large-scale trial is already taking place in UK secondary schools [30], many of the approaches investigated involve intensive programmes requiring extensive staff training and scheduling in school-based classes. Brief approaches to implementing mindfulness practices could provide a feasible alternative for busy schools.

Relaxation

Relaxation and mindfulness exercises have long been suggested to incorporate similar underlying processes and thus lead to similar outcomes. However, more recent research has emphasised the significant differences between these two concepts [31]. Relaxation exercises differ from mindfulness exercises in that with the former the individual is asked to focus specifically on relaxation, such as through deep breathing and muscle relaxation, whereas in mindfulness the individual is asked to pay attention to the present moment in a non-judgmental way, such as through meditation [32]. A study conducted by Jain and colleagues [33] relating to a relaxation intervention and a mindfulness intervention found that in adults both interventions led to a significant decrease in distress, while positive mood increased. When applied to young people, there is evidence that both mindfulness and relaxation techniques (RT) can reduce emotional difficulties [34–36].

The effect of RT has been frequently studied in both adults and young people suffering from various acute or chronic medical conditions, such as cancer or asthma [37, 38]. Research investigating the effects of RT with respect to different psychopathological conditions has been lacking. However, there is consistent evidence for the alleviating effects of progressive muscle relaxation on anxiety, stress and depression symptoms in clinical and non-clinical populations [39–41], and for autogenic training on stress and anxiety symptoms [42], and guided imagery on depression, anxiety and stress in psychiatric patients [43].

There are few studies investigating the impact of solely RT on children’s mental health, with some evidence indicating positive effects on anxiety and stress [40]. Relaxation also forms a common thread in many school-based interventions aimed at improving internalising symptoms, including school-based cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and Mindfulness programmes [44].

Strategies for Safety and Wellbeing (SSW)

The development of SSW stemmed from emerging practice in some UK schools around teaching practical approaches to personal safety, known as ‘Protective Behaviours’ (PB). The PB model was developed in the US in 1970 as an anti-victim programme for children, adolescents and adults [45]. The overarching aim of SSW is to increase skills for children around safety, mental health and wellbeing and how to access sources of support. Specifically, pupils are taught to identify (1) what feels safe/unsafe, (2) support networks, (3) coping and help seeking strategies, as well as to (4) recognise and understanding feelings and (5) challenge stigma around mental illness. This is broken down into an 8-week programme. Weeks 1–2 cover the topic ‘It’s safe to talk about mental health’ and weeks 3–5 cover ‘What is safety and knowing when you are not safe?’. Week 6 focusses on ‘Speaking about safety – who could you speak to?’, week 7 focusses on ‘Staying safe in friendships’, while week 8 finishes with ‘Safe ways to manage emotions and network review’. This fits with Personal, Social, Health and Economic Education (PSHE) guidance [46] in the following ways: pupils should be taught to (1) understand how and when they feel unsafe, (2) identify support networks, (3) identify how and from whom to seek help, (4) identify how to recognise and talk about emotions and (5) challenge stereotypes.

Although it has been observed that PB has been applied to schools in the UK [47], there is currently no peer-reviewed evidence for the effectiveness of PB programmes.

Aims and hypothesis

To date, a mixed picture has emerged, which outlines some potential benefits for Mindfulness Practices and Relaxation, and the need to develop an evidence base for SSW. A scoping exercise, conducted by the Department for Education in England, concluded that all three should be tested to contribute to the UK evidence base for effective interventions to improve mental health in children and young people.

Effectiveness measurement

Primary aims

To examine whether Mindfulness Practices are more effective than usual school-based provision in reducing internalising difficulties in young people

To examine whether Relaxation is more effective than usual school-based provision in reducing internalising difficulties in young people

To examine whether SSW is more effective than usual school-based provision in increasing intended help-seeking behaviour among young people around mental health

Primary hypotheses

H1 Young people receiving Mindfulness Practices will report lower internalising difficulties at 3–6 and 9–12 months’ follow-up than those who receive the usual school curriculum

H2 Young people receiving Relaxation will report lower internalising difficulties at 3–6 and 9–12 months’ follow-up than those who receive the usual school curriculum

H3 Young people receiving SSW will report increased intended help-seeking around mental health at 3–6 and 9–12 months’ follow-up than those who receive the usual school curriculum

Secondary aims

To examine the cost-effectiveness of the interventions compared to Usual Practice in terms of the primary outcome measure and paediatric quality of life.

Cost effectiveness research questions

Are Mindfulness Practices and Relaxation cost-effective when compared to Usual Practice in terms of internalising difficulties and quality of life?

Is Strategies for Safety and Wellbeing cost-effective when compared to Usual Practice in terms of intended help seeking and quality of life?

Implementation and process evaluation research questions

What is the state of participating schools’ existing provision for supporting mental health and wellbeing and their relationship with local mental health services, and does the nature of provision change over the course of the trial?

To what extent does implementation follow the guidelines of the specified interventions, e.g., in terms of fidelity and dosage?

What is the relationship between implementation variability (e.g., in terms of different levels of fidelity) and intervention outcomes?

What are the experiences of schools (pupils and staff) in delivering/receiving Relaxation, Mindfulness Practices and SSW?

Methods and analysis

The methodology outlined in this protocol follows a similar procedure to that of the AWARE trial [48] in relation to recruitment strategy and the economic evaluation. Both the INSPIRE trial (which this paper describes) and the AWARE trial are being conducted by the same team as part of a wider programme. The Additional file 1 provides an overview of enrollment, intervention and assessment timelines for INSPIRE.

Design

INSPIRE (INterventions in Schools for Promoting Wellbeing: Research in Education) is a four-arm cluster RCT including three intervention conditions (Mindfulness Practices, Relaxation and SSW) and one wait-list control (Usual Provision).

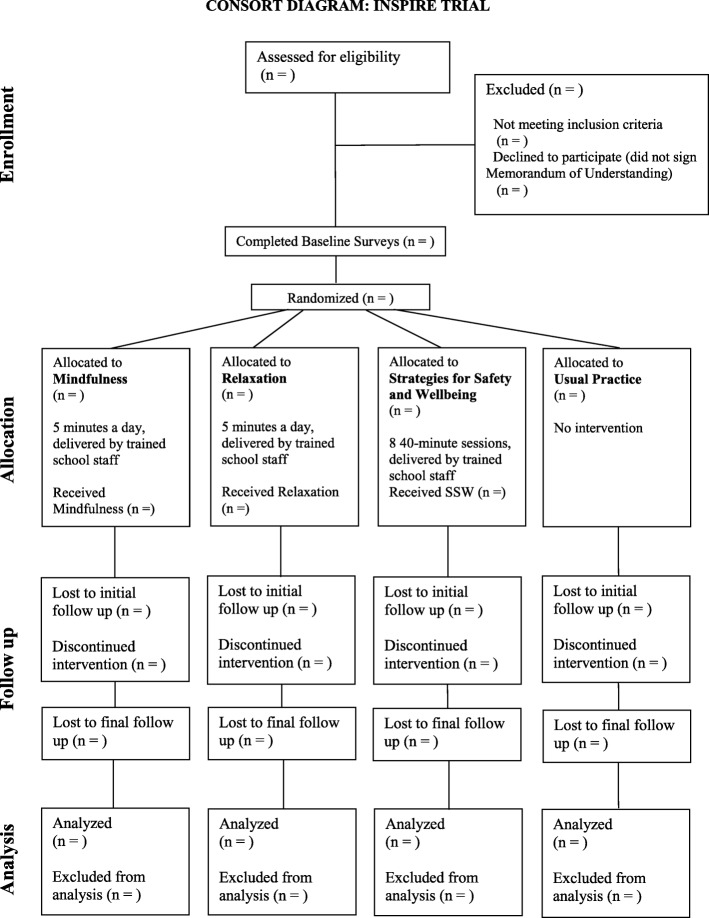

Interventions are delivered to whole school classes as part of the school curriculum. Assessment is undertaken at baseline (prior to intervention randomisation), and then 3–6 months and 9–12 months after interventions have been delivered. Figure 1 outlines a Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) Diagram showing the overall trial design.

Fig. 1.

Consolidate Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram

Site recruitment

Recruitment of schools began in March 2018 and will close in July 2019. Based on specification from the Department for Education, this study aims to recruit Year-7 and Year-8 pupils (aged 11–13 years) in 64 secondary schools and Year-4 and -5 pupils (aged 8–10 years) in 160 primary schools across England. Within each secondary school, three Year-7 and three Year-8 classes will be required to take part. Primary schools will work with up to four classes (minimum one Year-4 and one Year-5 class).

Schools will be recruited via a range of different networks and mailing lists, including bought data on English schools (school mailings), the Schools in Mind network hosted by the Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families (AFNCCF), AFNCCF associates and collaborators, the National Institute for Health Research, Public Health England, school commissioners and local authority leads. The project will also be advertised in education publications and on various social media platforms.

Incentives for schools to take part, include:

£1000 remuneration in recognition of administrative commitments

The opportunity to introduce whole-class mental health and wellbeing interventions with support from leading experts in child mental health

The chance to receive free mental health and wellbeing training for selected school staff

An evaluation feedback report for your school

Contributing to the wider evidence base on what works for school-based mental health support and how it can best be delivered

A letter of thanks from the Department for Education acknowledging the school’s important role in this project

Participant recruitment

Following recruitment of schools, participants in relevant year groups are recruited in two stages. Schools first select delivery groups in each year who will receive an intervention (if allocated). Following this, schools send letters to parents/carers of pupils in these delivery groups. The letter provides information about the study and explains parents/carers’ right to opt their child out of the evaluation. The letter also explains that pupils will only be involved in the study if they assent online before completing the baseline survey. Finally, young people must assent by reading through an online information sheet and ticking boxes agreeing to take part. If they do not assent, they cannot be part of the trial. The first young person joined the trial on the 17 September 2018.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Schools are eligible to participate if:

They are a primary school (state-funded/academy/independent) willing to deliver an intervention to one or two Year-4 classes, and one or two Year-5 classes in their school

They are a secondary school (state-funded/academy/independent) willing to deliver an intervention to three Year-7 classes and three Year-8 classes in their school

They are willing to be allocated to Mindfulness Practices, Relaxation, SSW or continue with usual provision

They are willing to allocate 5 min per day for young people to practise these skills for the spring term if allocated to Mindfulness Practices or Relaxation

They are willing to allocate eight 40-min lessons to deliver the programme over the spring term if allocated to SSW

They are able to send staff to a regional training session, if required

They are in England

Young people are eligible to take part if:

-

8.

Their parents/guardians do not withdraw consent

-

9.

They provide assent

Schools are not eligible to take part if:

They are a non-mainstream specialist school (e.g., pupil referral unit)

They are unable to commit to the study requirements above

They are already taking part in similar trials (e.g., MYRIAD [30])

They are outside of England

Young people are not eligible to take part if:

Their parents do not provide consent for them to take part

They do not assent to take part

They are not in specified year groups

While privately funded schools are invited to express interest in the project, they will only form < 2% of the total sample. Single-sex schools are also eligible to take part but will be limited to < 5% of the sample.

Interventions

Across the active arms of the trial, schools are required to select staff to attend and deliver the interventions. There are no criteria for this role and this can include, but is not limited to: teachers, senior school leaders, teaching assistants, or special educational needs coordinators (SENDCos).

Each of the interventions was developed by a group of experts, consisting of psychologists, researchers, the Programme Director of Mental Health and Wellbeing Schools and a Headteacher Quality Assurance Panel. Teachers who delivered interventions as part of the pilot [24] also provided feedback which was incorporated into interventions delivered in the full trial. Logic models for the interventions are found in the Additional files 2 and 3.

Mindfulness Practices

This Mindfulness intervention was developed for the trial by the AFNCCF Schools Programme (lead developer: Dr. Rina Bajaj). It is based on the concept of mindfulness as defined by Kabat-Zinn: ‘paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally’ [32], and draws on a number of existing mindfulness models including the RAIN approach [49] and the two-component model of mindfulness [50]. The Mindfulness intervention consists of mindful breathing exercises and other activities focussed on self-awareness of sensations, emotions and thoughts. The exercises are divided into three types: (1) those focussing on the mind; (2) those focussing on the body; (3) those focussing on the world.

School staff complete a half-day face-to-face training course delivered by two AFNCCF professionals that focusses on practising mindfulness exercises. A mindfulness manual – either a primary or secondary school-specific version – is provided. Both manuals contain 21 different activities, as well as suggestions for recommended apps and interactive online games. Mindfulness is delivered to school classes in classrooms for around 5 min each school day at a time chosen by the deliverer, from January to April in the first instance, and this is the period in which implementation is monitored. However, schools are encouraged to continue to practice for 1 year.

Relaxation

This Relaxation intervention was also developed for the trial by the AFNCCF Schools Programme (lead developer: Dr. Rina Bajaj). The intervention consists of relaxation exercises focussing on two main themes: (1) deep breathing and (2) progressive muscle relaxation. School staff complete a half-day face-to-face training course focussing on experiential exercises, delivered by AFNCCF professionals. Manuals containing 20 different activities are provided (primary and secondary school versions). These manuals also include recommendations of apps, videos and interactive online games.

Similar to the Mindfulness model, relaxation exercises are delivered in classes for around 5 min each school day, at a time chosen by the deliverer. School staff alternate every week between deep breathing and progressive muscle relaxation activities. Relaxation is delivered to school classes in classrooms from January to April in the first instance, as this is the period in which implementation is monitored. However, schools are encouraged to continue to practise for 1 year.

Strategies for Safety and Wellbeing

SSW was also developed by the AFNCCF schools programme (lead developer: Dr. Rina Bajaj), who consulted with experts in PB interventions. School staff complete a half-day face-to-face training course with the lead developer. The training focusses on covering the psychoeducational content of an 8-week session plan with lessons adapted for primary or secondary school pupils. The eight sessions are as follows:

It is safe to talk about mental health

You are never too young to talk mental health (primary schools)/We all have mental health (secondary schools)

What is safety?

Early warning signs – noticing our bodies

Early warning signs – noticing our feelings and thoughts

Developing our safety networks

Safe friendships

Safe ways of managing emotions

Each session lasts for approximately 40 min and is delivered once a week for 8 weeks.

Usual Practice

Schools allocated to the Usual Practice group are not required to deliver a specific mental health intervention during the programme (June 2018 to January 2021), but may already do so as part of their usual whole-school provision around mental health. All participating schools will complete the Usual Provision Survey at the end of the project (second follow-up) so we are able to track changes in mental health and wellbeing provision. At the end of the project, schools in the Usual Practice arm will select from a suite of training available at the AFNCCF and send up to six staff members on their chosen training.

Study measures

The following measures will be completed prior to the intervention and follow-up will take place at 3–6 and 9–12 months post intervention. All questionnaires will be completed online.

Pupils

Primary outcome measures

Secondary outcome measures

The secondary outcome measures across all interventions include:

Mental health first aid [53]

Paediatric Quality of Life (Child Health Utility-9D; CHU9D) [54]

Positive wellbeing: Huebner Life Satisfaction Scale (LSS) [55]

In addition, secondary school pupils will be asked further questions:

School staff

Similar to pupils, school staff participating in the project (those who are nominated by the school to deliver the intervention) will complete measures around mental health literacy [61–65] prior to the intervention. Follow-up will take place at 3–6 and 9–12 months post intervention and all questionnaires will be completed online.

Measures for economic evaluation

As part of the assessment, pupils will complete:

A Client Service Receipt of Inventory (CSRI; adapted for the study population) [66]

A Service Information Schedule (SIS) [67]

In addition to this, school staff delivering the interventions and school finance officers will provide the following data informing the calculation of an intervention cost: time spent preparing and delivering the intervention, staff member salary band, staff member full-time equivalent working hours, staff member pension contributions and national insurance contributions as a percent of their annual salary, and any other staff overheads.

Implementation and process monitoring measures

Usual Provision Survey

Before intervention delivery, and again 1 year later, a senior leader in each school will be asked to complete a survey online regarding current whole-school mental health provision.

Implementation surveys and outcome measures

School staff that deliver an intervention will complete one online implementation survey per delivery group at the end of the initial delivery period. Questions will cover six key aspects of implementation, namely fidelity, quality, dosage, participant responsiveness, reach and adaptations. Within this, three aspects relating to the social validity of the intervention (acceptability, feasibility and utility) will also be assessed using a standardised questionnaire [68]. The survey will also capture other aspects related to dosage and the time of day that the intervention was delivered.

Qualitative data and observations

Qualitative implementation and process data will be collected at two time points. The first time point will take place at mid- to late-implementation of each of the interventions. Twelve schools will be recruited from the main sample as qualitative case study schools; one school per intervention in each of the four areas of England (north west, north east, south west, south east). This will not include Usual Practice schools. Case study schools will be recruited via expression of interest, to maximise the likelihood of engagement with the qualitative research, and sampled based on variation in their usual provision around mental health, drawing on data from two items in the first Usual Provision Survey:

Please identify, in the last 2 years, the activities and approaches that have been used in your school and indicate who has delivered/provided these activities

-

How significant are the following potential barriers to providing effective

mental health support within your school?

While the case study schools could be selected on multiple bases, these contextual factors are those of particular interest to the trial, in terms of how they could affect the implementation and take-up of the interventions within the schools.

Face-to-face or telephone interviews will be conducted with two to three members of staff (including a school senior leadership team member and a staff member delivering the intervention) and one to two focus groups will be conducted face-to-face with pupils (with approximately four to five pupils in each focus group) at each school. Pupils will be selected via expression of interest, and up to 10 will be invited to participate due to risk of attrition or pupils declining to take part. Learning from the feasibility study [24] indicated that this sample size would yield a large amount of rich qualitative data, while still being manageable in terms of the research team’s capacity.

The interviews/focus groups will be semi-structured, enabling the research team to guide the conversation according to their topics of interest, while at the same time allowing participants to raise issues around these topics that are pertinent to them. All interviews/focus groups will be audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

The topics that the interviews with staff will cover include:

Experiences of delivering the interventions and receiving training to deliver the interventions

Perceptions of the barriers and facilitators to delivery

Perceptions of impact

Suggestions for improvement of the interventions

Barriers and facilitators to the sustainability of the interventions

The topics that the focus groups with pupils will cover include:

Experiences of taking part in the interventions

Perceptions of impact and helpful aspects of the interventions

Suggestions for improvement of the interventions

A session of the intervention at each school will also be observed by the research team to gather contextual information about what the interventions look like on the ground. Field notes will be taken during the observation on the process of delivery, the layout of the room, and the atmosphere during delivery. Individual pupil or staff responses will not be recorded.

The second time point will take place approximately 9–12 months after Time 1. At Time 2, we will conduct approximately five follow-up visits with five of the schools from Time 1 at which, according to implementation monitoring survey data, the interventions have been particularly well embedded to explore long-term impact and facilitators to (ongoing) implementation from staff and pupil perspectives. This will involve face-to-face or telephone interviews with one to two members of staff and one face-to-face focus group with pupils at each school. We will also explore potential barriers to long-term impact and implementation through a telephone interview with a staff member at approximately three schools at which, again according to implementation monitoring survey data, the interventions have not been particularly well embedded.

Furthermore, as schools that express interest in taking part as a case study are likely to be the more engaged schools, at the second time point we will also conduct a small number of telephone interviews with staff at schools that have engaged less with the trial in general. This will allow us to gather data on the barriers that they may have experienced to engaging with the trial and could include schools that have dropped out of the trial.

Randomisation of schools

To ensure approximate distribution across conditions, randomisation will be carried out by Kings Clinical Trials Unit (KCTU). Due to recruitment rates the trial is split into two cohorts. Randomisation of schools will take place in two batches (first cohort: 22 and 23 October 2018; second cohort planned for 21 and 22 October 2019). In both randomisations minimisation will be used to take into account regional representation (four recruitment hubs); deprivation as indicated by free school-meal (FSM) eligibility (tertiles of sample FSM rates); current mental health provision (Mindfulness, Relaxation, Strategies for Safety and Wellbeing, other structured lessons; none); and urban/rural situation of school. Only the statistician, quantitative data analyst and economist are blind to intervention allocation.

Data management

All quantitative data will be stored on the University of Manchester’s secure server. The Data Manager (JS), along with the Research Assistants (EA and RM) will be responsible for cleaning and coding the data. Qualitative data (audio files and transcripts) will be stored on the AFNCCF’s secure server. The Qualitative Research Lead (ES), supported by the Trials Manager (DH), Research Officer (AM) and Research Assistants (RM and EA), will be responsible for data storage, and checking transcripts and ensuring their accuracy.

Sample size

The trial will be analysed on class-level, controlling for school- and class-level clustering, due to the delivery of the intervention within classes. The design for the current trial is a between-school trial. To increase the efficiency of the design, we will use a single set of control schools as a comparator for all three interventions. The schools will be randomised to four groups (Usual Practice, Mindfulness Practices, SSW, Relaxation); around two to three of the schools in each arm will be primary schools and one to three will be secondary schools to accommodate the different numbers of classes and class sizes within each school type.

While cluster effects of emotional distress on school level are usually small [69, 70], no data on class-level clustering were available. To our knowledge, so far no study has looked into school-level intra-class correlations (ICCs) of help-seeking. We conducted a pilot study with N = 2289 students nested within 113 classes within 17 schools and we found ICCs of .05 for the SMFQ and of .03 for the GHSQ (with upper borders of bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals of .12 for the GHSQ and .13 for the SMFQ). The following sample size calculation is based on an ICC of ρ = .15, which is still conservative given the estimates found in the pilot (for a significance level of p = .05 and statistical power of β = .80).

Pre-test values of the outcome measures will be used as predictors of within-school variance. Since pre- and post-tests tend to be correlated, a conservative estimate of R2 = .20 was used. Since only a small effect due to the intervention is expected, MDES = .20 was selected as the target effect size. On average, we assume primary schools to have two classes (with N = 25 students each) and secondary schools to have six classes (N = 20 students each). Finally, since the analysis of the primary outcome only compares each active treatment individually against the control arm, no correction of error rates was performed for these pre-planned directed hypotheses [71].

Accommodating the setting of a delivery from four different study areas, we aim to recruit 56 schools per arm (40 primary; 16 secondary with six classes each). Given this number of classes, the MDES without controlling for any additional variables in the full sample is MDES = .129 (MDES = .190 in primary and MDES = .177 in secondary schools only). Including pre-tests leads to an MDES = .127 for the full sample (and MDES = .186 in primary and MDES = .173 in secondary schools). The statistical analyses will be undertaken by an independent statistician (JB) at the University of Dundee.

Statistical analysis of the primary outcome

A detailed statistical analysis plan will be written prospectively, but the sample size calculation was based on estimating three mixed models, each comparing an active treatment with the control arm. The mixed model will allow for school-level clustering; control for baseline levels in the primary outcome; and the minimisation variables (see above). An intervention will be evaluated as potentially effective if the point estimate of the coefficient for the dummy variable coding the difference between intervention and control arm indicates a group difference in the hypothesised direction for the outcome and the cluster-bootstrapped 95% confidence interval does not include zero. The primary outcome tested for the Mindfulness Practices and Relaxation arms is the SMFQ; and for SSW the primary outcome is the GHSQ; all three at 3–6 months’ follow-up. The analysis will be intent-to-treat. This analysis will be undertaken using R [72]. The potential impact of missing data will be evaluated in a sensitivity analysis using fully conditional specification [73].

Economic evaluation

Service use and costs

A Service Information Schedule will be designed to facilitate micro-costing of the interventions. Information on services and supports used by the young people in the study will be collected using a specially adapted version of the CSRI [66]. From these data, we will investigate whether patterns of service use and associated costs differ, and explore whether any differences are driven by individual characteristics or baseline level of need.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

To assess whether the interventions are cost-effective relative to Usual Practice, cost-effectiveness and cost-utility analyses will be undertaken for change in (a) the primary outcome measure for each intervention and (b) quality-adjusted life years (derived from the CHU9D) [54]. We will employ an analytical approach that allows for adjustment for confounders, the likely non-normal distribution of cost data, the joint analysis of cost and outcome measures and the potential effects of clustering. Results will be presented as cost-effectiveness acceptability curves [74] plotting the probability that the intervention will be considered cost-effective compared to treatment as usual against different levels of willingness to pay for an improvement in outcome. Sensitivity analyses will be undertaken by varying assumptions used to calculate the intervention cost. Potential sub-group analyses will be identified post hoc.

Process and implementation analysis

Descriptive statistics will be used to document usual school provision and how this changes over the course of the project, as well as to document the implementation of Relaxation, Mindfulness Practices and SSW. Additionally, for examining implementation, we will compare ‘intervention as delivered’ from our survey data with ‘intervention as planned’. Where applicable, the latter can be used to determine the proportion of participating schools that can be deemed to have achieved at least a minimum standard of intervention delivery (e.g., ‘on treatment’ status). To assess the relationship between implementation variability and outcomes, multi-level modelling will be used, in which we fit the implementation data noted above (or on treatment status derived from said data) as explanatory variables at the school or class level, to assess the extent to which they are predictive of intervention outcomes at the pupil level.

Qualitative interviews and focus group transcripts will be analysed using thematic analysis [75], using the NVivo version 12 [76] data analysis software package. Up to three members of the research team will initially code or assign relevant extracts of the transcripts to broad overarching categories, derived ‘top-down’ from the research questions (e.g., suggestions for improvement). The researchers will then break down the data (transcript extracts) coded within these overarching categories into themes and subthemes, derived ‘bottom-up’ from the data. A fourth member of the research team will then re-code 10–20% of the transcripts using the themes and subthemes derived from the data by the other members of the team. The purpose of the latter step is to help the original researchers to refine and reflect on their themes and subthemes, with the additional researcher suggesting edits or additions where necessary.

Patient and public involvement

Young people provided input into the development and refinements of the interventions, including what techniques and activities should be included, as well as input into the design of the booklets. In relation to research, young people provided input into what questions were included in the final questionnaires for young people and will be involved in disseminating reports and findings.

Trial status

Recruitment for schools opened in March 2018 and will stay open until July 2019. The first young person joined the trial on 17 September 2018. The last participants will be followed up at the 1-year follow-up in January/February 2021. A timeline for the trial is available as Additional file 4.

Protocol

V1, 14 January 2019. Substantial changes to the protocol will be communicated from the Trials Manager to relevant parties (e.g., ISRCTN). The protocol follows Standard Protocol items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) reporting [77].

Supplementary information

Additional file 1. INSPIRE Trial Timeline.

Additional file 2. Logic model for Mindfulness and Relaxation.

Additional file 3. Logic model for Strategies for Safety and Wellbeing.

Additional file 4. Reporting checklist for protocol of a clinical trial.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Education for Wellbeing advisory group for providing comments on earlier versions of the manuscript.

Roles and responsibilities

JD is the Principal Investigator. NH is the Implementation Lead. DH is the Trials Manager. JS is the Data Manager. ES is the Qualitative Lead. AM is Research Officer/School Liaison Lead. RM and EA are Research Assistants. JB is the Trials Statistician. PP provides expertise around measures and statistical analysis. BM provides expertise on evaluating mindfulness practices. EB is the Health Economist.

Authors’ contributions

NH, EA, RM and ES lead on decisions for the process and implementation strand of the project and contributed to the writing of this section of the protocol. EB leads on decisions for the economic strand of the project and contributed to the writing of this section of the protocol. JB leads on statistical and study design elements of the project, contributed to the writing of the sample size calculation and analysis plan, and contributed to the writing of these sections of the protocol. PP leads on measures and their psychometric properties as well as mediation and moderation analysis. JS leads on decisions relating to data management and contributed to the writing of this section of the protocol. DH, supported by AM, leads on decisions relating to trial management, wrote the first draft of the protocol, and contributed to edits and amendments in subsequent drafts. DH also leads on ethical procedures and contributed to writing this section of the protocol. BM provided input and expertise into mindfulness practices and measures for them and contributed to edits on this section. JD is the Principle Investigator, conceptualised the overall trial design, has final sign decision sign-off, and contributed to the writing of this protocol. A Measures Group consisting of PP, JD, DH, AM, NH, EA, RM, JS, EB and JB finalised measures for the trial. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was commissioned and funded by the Department for Education. The Department selected the interventions to be trialled and also chairs an Advisory Group that the researchers report to regarding the progress and quality of the research. However, the department had no role in the design of this study and will not have any role in the analyses, interpretation of the data, or decision to submit results. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department for Education. JD was (in part) supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) North Thames at Bart’s Health NHS Trust. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Availability of data and materials

An anonymised quantitative dataset generated and/or analysed during the current study will be available in 2022 once the study has finished. A decision regarding storage location is yet to be finalised, please contact the Principal Investigator or Trials Manager for further information.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval for this study was granted from University College London (UCL) Research Ethics Committee (6735/009 and 6735/014). Research data will be processed and stored in line with the General Data Protection Regulation. Schools that express an interest in taking part, and are deemed eligible, will be required to have a member of their senior leadership team sign a Memorandum of Understanding, and data-sharing agreement.

Pupil data

Consent for pupils to take part will require different processing depending on the data being collected. For outcome (effectiveness) data, opt-out consent will be used when sending letters to parents/carers of pupils who have been selected by schools to take part. Parents/carers who wish to opt out their children will be asked to return an opt-out form to the research team. A survey password will not be created for pupils that are opted out, and this is flagged to schools in a timely manner to prevent these pupils from taking part in the surveys. GDPR-compliant data deletion processes will be enforced when pupils are opted out after taking part in the surveys.

Pupils whose parents have not opted out of the evaluation will be given the option to assent to take part through reading an online information sheet and ticking an online assent form. Pupils who start the survey can stop and/or opt out at any time. Pupils who do not tick the assent form will not be allowed to complete the survey. All information sheets outline confidentiality procedures for collecting, processing, and storing data. Teachers are asked not to look directly at pupils’ screens when they are filling out answers. They are also provided with a crib-sheet of the more difficult words in the survey that young people may struggle with, in order for them to assist pupils from the front of the classroom.

Other survey data

Opt-in consent will be required for all other data, including all surveys completed by staff.

Qualitative data

Opt-in consent will be required for all interviews and focus groups. All individuals will be required to read an information sheet, detailing what will happen, and for those that are happy to proceed, to sign a consent form.

For pupils under the age of 16 years, schools will send letters home to pupils’ parents/guardians, and those that are happy for their young people to take part will be required to sign a consent form. Prior to focus groups taking place, pupils will be required to read an information sheet, and tick an assent form stating that they are happy to take part. Those who do not assent will not take part.

Observations

As no individual or personal data will be collected for observations, consent/assent will not be required.

Monitoring of adverse events (AEs)

AEs, defined as a negative, emotional and behavioural occurrence, or sustained deterioration in a research participant, will be captured as part of the study. This includes serious adverse events (SAEs) which are a threat to life: suicidal ideation, suicidal intent, hospitalisation due to psychiatric of use of substances, death including suicide. Other adverse events: violent behaviour, self-harm, or any other event that an individual feels it is important to report, will also be captured. School safeguarding leads will judge whether they believe the AE is likely related to the intervention.

The ongoing conduct and progress of this study is monitored by an independently chaired Data Monitoring Committee (DMC). On becoming aware of SAEs, the Principal Investigator or Trials Manager will report all SAEs, or AEs which are likely to be related to the intervention or research, to the DMC within two working days. AEs thought to be unlikely related to the intervention or research should be reported within five working days and will be collated and reported quarterly to the DMC. The UCL Research Ethics Committee will also be informed of AEs and SAEs using the same mechanisms. School and research safeguarding protocols will be followed as standard in addition to the reporting and documenting of AEs. The DMC is responsible for making recommendations to the Department for Education regarding the stopping or continuing of the trial.

Trial sponsor. The trial is sponsored by UCL.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

These measures were included in baseline primary surveys as they are thought to be potential moderators. However, these are removed at follow-up due to data burden for primary schools.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s13063-019-3762-0.

References

- 1.Sadler K, Vizard T, Ford T, Marchesell F, Pearce N, Mandalia D, et al. Mental health of children and young people in England, 2017. London: NHS England; 2017.

- 2.D’amico F, Knapp M, Beecham J, Sandberg S, Taylor E, Sayal K. Use of services and associated costs for young adults with childhood hyperactivity/conduct problems: 20-year follow-up. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;204(6):441–447. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.131367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glied S, Neufeld A. Service system finance: implications for children with depression and manic depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:1128–1135. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(01)01131-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenberg PE, Sisitsky T, Kessler RC, Finkelstein SN, Berndt ER, Davidson JR, et al. The economic burden of anxiety disorders in the 1990s. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(7):427–435. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v60n0702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kieling C, Baker-Henningham H, Belfer M, Conti G, Ertem I, Omigbodun O, et al. Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action. Lancet. 2011;378(9801):1515–1525. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60827-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel V, Flisher AJ, Hetrick S, McGorry P. Mental health of young people: a global public-health challenge. Lancet. 2007;369(9569):1302–1313. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60368-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aviles AM, Anderson TR, Davila ER. Child and adolescent social-emotional development within the context of school. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2006;11(1):32–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2005.00365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langford R, Bonell CP, Jones HE, Pouliou T, Murphy SM, Waters E, et al. The WHO Health Promoting School framework for improving the health and well-being of students and their academic achievement. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;4(4):CD008958. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008958.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roanes M, Hoagwood K. School-based mental health services: a research review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2000;3(4):223–241. doi: 10.1023/A:1026425104386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calear AL, Christensen H. Systematic review of school-based prevention and early intervention programs for depression. J Adolesc. 2010;33(3):429–438. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neil AL, Christensen H. Efficacy and effectiveness of school-based prevention and early intervention programs for anxiety. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(3):208–215. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson SJ, Lipsey MW. School-based interventions for aggressive and disruptive behavior: Update of a meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(2):S130–S143. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shochet IM, Dadds MR, Holland D, Whitefield K, Harnett PH, Osgarby SM. The efficacy of a universal school-based program to prevent adolescent depression. J Clin Child Psychol. 2001;30:303–315. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3003_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Humphrey N, Lendrum A, Wigglesworth M. Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning (SEAL) in secondary schools: national evaluation. London: Department for Education; 2010.

- 15.Hallam S. An evaluation of the Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning (SEAL) programme: promoting positive behaviour, effective learning and well-being in primary school children. Oxford Rev Educ. 2009;25(3):313–330. doi: 10.1080/03054980902934597. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Webster-Stratton C, Jamila Reid M, Stoolmiller M. Preventing conduct problems and improving school readiness: evaluation of the incredible years teacher and child training programs in high-risk schools. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49(5):471–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01861.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Domitrovich CE, Cortes RC, Greenberg MT. Improving young children’s social and emotional competence: a randomized trial of the preschool ‘PATHS’ curriculum. J Prim Prev. 2007;28(2):67–91. doi: 10.1007/s10935-007-0081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ford T, Hayes R, Byford S, Edwards V, Fletcher M, Logan S, et al. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the Incredible Years® Teacher Classroom Management Programme in primary school children: results of the STARS cluster randomised controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2019;49(5):828–842. doi: 10.1017/S0033291718001484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Humphrey N, Lendrum A, Ashworth E, Frearson K, Buck R, Kerr K. Implementation and process evaluation (IPE) for interventions in educational settings: A synthesis of the literature. London: EEF; 2016.

- 20.Wigelsworth M, Lendrum A, Oldfield J, Scott A, ten Bokkel I, Tate K, Emery C. The impact of trial stage, developer involvement and international transferability on universal social and emotional learning programme outcomes: a meta-analysis. Cambridge J Educ. 2016;46(3):347–376. doi: 10.1080/0305764X.2016.1195791. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolpert M, Deighton J, Patalay P, Martin A, Fitzgerald-Yau N, Demir E, et al. Me and my school: findings from the national evaluation of Targeted Mental Health in Schools. Nottingham: DFE. Nottingham; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vostanis P, Humphrey N, Fitzgerald N, Deighton J, Wolpert M. How do schools promote emotional well-being among their pupils? Findings from a national scoping survey of mental health provision in English schools. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2013;18(3):151–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2012.00677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Durlak JA, DuPre EP. Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41(3–4):327. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stapley E, Moore A, Hayes D, Humphrey N, Mansfield R, Santos J, et al. Education for Wellbeing ‘Pilot Findings’. London: Evidence Based Practice Unit (EBPU); 2018.

- 25.Chiesa A, Anselmi R, Serretti A. Psychological mechanisms of mindfulness-based interventions: what do we know? Holist Nurs Pract. 2014;28(2):124–148. doi: 10.1097/HNP.0000000000000017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mendelson T, Greenberg MT, Dariotis JK, Gould LF, Rhoades BL, Leaf PJ. Feasibility and preliminary outcomes of a school-based mindfulness intervention for urban youth. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2010;38(7):985–994. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9418-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zoogman S, Goldberg SB, Hoyt WT, Miller L. Mindfulness interventions with youth: a meta-analysis. Mindfulness (NY) 2015;6(2):290–302. doi: 10.1007/s12671-013-0260-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schonert-Reichl KA, Lawlor MS. The effects of a mindfulness-based education program on pre-and early adolescents’ well-being and social and emotional competence. Mindfulness (N Y) 2010;1(3):137–151. doi: 10.1007/s12671-010-0011-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maynard BR, Solis MR, Miller VL, Brendel KE. Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Improving Cognition, Academic Achievement, Behavior, and Socioemotional Functioning of Primary and Secondary School Students. Campbell Systematic Reviews 2017: 5. Campbell Collaboration. 2017.

- 30.Kuyken W, Nuthall E, Byford S, Crane C, Dalgleish T, Ford T, et al. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a mindfulness training programme in schools compared with normal school provision (MYRIAD): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2017;18(1):194. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-1917-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baer RA. Mindfulness training as clinical intervention: a conceptual and empirical review. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2003;10:125–143. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bpg015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2003;10(2):144–156. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bpg016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jain S, Shapiro SL, Swanick S, Roesch SC, Mills PJ, Bell I, Schwartz GE. A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation versus relaxation training: effects on distress, positive states of mind, rumination, and distraction. Ann Behav Med. 2007;33(1):11–21. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3301_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vohra S, Punja S, Sibinga E, Baydala L, Wikman E, Singhal A, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for mental health in youth: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2019;24(1):29–35. doi: 10.1111/camh.12302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldbeck L, Schmid K. Effectiveness of autogenic relaxation training on children and adolescents with behavioral and emotional problems. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(9):1046–1054. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000070244.24125.F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larson HA, Yoder AM, Johnson C, El Rahami M, Sung J, Washburn F. Test anxiety and relaxation training in third-grade students. Eastern Education Journal. 2010:13.

- 37.Luebbert K, Dahme B, Hasenbring M. The effectiveness of relaxation training in reducing treatment-related symptoms and improving emotional adjustment in acute non-surgical cancer treatment: a meta-analytical review. Psychooncology. 2001;10(6):490–502. doi: 10.1002/pon.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Georga Georgia, Chrousos George, Artemiadis Artemios, Panagiotis Pelekasis P., Bakakos Petros, Darviri Christina. The effect of stress management incorporating progressive muscle relaxation and biofeedback-assisted relaxation breathing on patients with asthma: a randomised controlled trial. Advances in Integrative Medicine. 2019;6(2):73–77. doi: 10.1016/j.aimed.2018.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dolbier CL, Rush TE. Efficacy of abbreviated progressive muscle relaxation in a high-stress college sample. Int J Stress Manag. 2012;19(1):48. doi: 10.1037/a0027326. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rasid ZM, Parish TS. The effects of two types of relaxation training on students’ levels of anxiety. Adolescence. 1998;33(129):99–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vancampfort D, Correll CU, Scheewe TW, Probst M, De Herdt A, Knapen J, De Hert M. Progressive muscle relaxation in persons with schizophrenia: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Clin Rehabil. 2013;27(4):291–298. doi: 10.1177/0269215512455531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ernst E, Kanji N. Autogenic training for stress and anxiety: a systematic review. Complement Ther Med. 2000;8(2):106–110. doi: 10.1054/ctim.2000.0354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Apóstolo JLA, Kolcaba K. The effects of guided imagery on comfort, depression, anxiety, and stress of psychiatric inpatients with depressive disorders. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2009;23(6):403–411. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stallard P, Simpson N, Anderson S, Carter T, Osborn C, Bush S. An evaluation of the FRIENDS programme: a cognitive behaviour therapy intervention to promote emotional resilience. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90(10):1016–1019. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.068163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Flandreau WP. Protective behaviors: anti-victim training for children, adolescents and adults. 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Depatment for Education, Relationships, Education, Relationships and Sex Education (RSE) and Health Education. Statutory guidance for governing bodies, proprietors, head teachers, principals, senior leadership teams, teachers. London: Department for Education; 2019.

- 47.Fardon J. Protective behaviours. In: Simons M, editor. Northamptonshire TAMHS (Targeted Mental Health in Schools Project). Northampton: Northamptonshire Children and Young People's Partnership; 2011.

- 48.Hayes D, Moore A, Stapley E, Humphrey N, Mansfield R, Santos J, et al. A school based interventions study examining approaches for wellbeing and mental health literacy of pupils in year nine in England: study protocol for a multi-school, cluster randomised control trial (AWARE) BMJ Open. 2019;9:e029044. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ameli R. 25 lessons in mindfulness: now time for healthy living. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bishop SR, Lau M, Shapiro S, Carlson L, Anderson ND, Carmody J. Mindfulness: a proposed operational definition. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2004;11(3):230–241. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bph077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Angold A, Costello EJ, Messer SC, Pickles A, Winder F, Silver D. Development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 1995;5:237–249. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilson CJ, Deane FP, Ciarrochi J, Rickwood D. Measuring help-seeking intentions: properties of the General Help-Seeking Questionnaire. Can J Couns. 2005;39:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hart LM, Mason RJ, Kelly CM, Cvetkovski S, Jorm AF. ‘Teen Mental Health First Aid’: a description of the program and an initial evaluation. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2016;10(1):3. doi: 10.1186/s13033-016-0034-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stevens K. Developing a descriptive system for a new preference-based measure of health-related quality of life for children. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(8):1105–1113. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9524-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huebner ES. Initial development of the Student’s Life Satisfaction Scale. Sch Psychol Int. 1991;12(3):231–240. doi: 10.1177/0143034391123010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Evans-Lacko S, Little K, Meltzer H, Rose D, Rhydderch D, Henderson C, Thornicroft G. Development and psychometric properties of the Mental Health Knowledge Schedule. Can J Psychiatr. 2010;55(7):440–448. doi: 10.1177/070674371005500707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Evans-Lacko S, Rose D, Little K, Flach C, Rhydderch D, Henderson C, Thornicroft G. Development and psychometric properties of the Reported and Intended Behaviour Scale (RIBS): a stigma-related behaviour measure. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2011;20(3):263–271. doi: 10.1017/S2045796011000308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Milin R, Kutcher S, Lewis SP, Walker S, Wei Y, Ferrill N, et al. Impact of a mental health curriculum on knowledge and stigma among high school students: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55(5):383–391. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Deighton J, Tymms P, Vostanis P, Belsky J, Fonagy P, Brown A, Martin A, Patalay P, Wolpert W. The development of a school-based measure of child mental health. J Psychoeduc Assess. 2013;31(3):247–257. doi: 10.1177/0734282912465570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sun J, Stewart D. Development of population-based resilience measures in the primary school setting. Health Educ Res. 2007;7(6):575–599. doi: 10.1108/09654280710827957. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fortier A, Lalonde G, Venesoen P, Legwegoh AF, Short KH. Educator mental health literacy to scale: from theory to practice. Adv Sch Ment Health Promot. 2017;10(1):65–84. doi: 10.1080/1754730X.2016.1252276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jorm AF, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Christensen H, Rodgers B, Pollitt P. ‘Mental health literacy’: a survey of the public’s ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Med J Aust. 1997;166:182–186. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb140071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mcluckie A, Kutcher S, Wei Y, Weaver C. Sustained improvements in students’ mental health literacy with use of a mental health curriculum in Canadian schools. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(1):379. doi: 10.1186/s12888-014-0379-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kutcher S, Wei Y, Coniglio C. Mental health literacy: past, present, and future. Can J Psychiatr. 2016;61(3):154–158. doi: 10.1177/0706743715616609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kutcher S, Wei Y, McLuckie A, Hines H. Successful application of mental health and high school curriculum guide in the Toronto District School Board (TDSB) Toronto: Increasing student mental health knowledge and decreasing stigma; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Beecham J, Knapp M. Costing psychiatric interventions. In: Thornicroft G, editor. Measuring mental health needs. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2001. pp. 200–224. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sleed M, Beecham J, Knapp M, McAuley C, McCurry N. Estimating the unit costs for Home-Start support. London: Unit Costs of Health and Social Care; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Weiner BJ, Lewis CC, Stanick C, Powell BJ, Dorsey CN, Clary AS, et al. Psychometric assessment of three newly developed implementation outcome measures. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):108. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0635-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gutman L, Feinstein L. Children’s well-being in primary school: pupil and school effects [wider benefits of learning research report no. 25]. Centre for Research on the Wider Benefits of Learning, Institute of Education, University of London; 2008.

- 70.Hale DR, Patalay P, Fitzgerald-Yau N, Hargreaves DS, Bond L, Görzig A. School-level variation in health outcomes in adolescence: analysis of three longitudinal studies in England. Prev Sci. 2014;15(4):600–610. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0414-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wason JM, Stecher L, Mander AP. Correcting for multiple-testing in multi-arm trials: is it necessary and is it done? Trials. 2014;15(1):364. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.R Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Enders CK, Du H, Keller BT. A model-based imputation procedure for multilevel regression models with random coefficients, interaction effects, and nonlinear terms. Psychol Methods. 2019. 10.1037/met0000228. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 74.Van Hout Ben A., Al Maiwenn J., Gordon Gilad S., Rutten Frans F. H. Costs, effects and C/E-ratios alongside a clinical trial. Health Economics. 1994;3(5):309–319. doi: 10.1002/hec.4730030505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Braun Virginia, Clarke Victoria. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.QSR Q. Nvivo 8 qualitative data analysis software. Victoria, Australia: QSR International Pty Ltd. 2008.

- 77.Chan A-W, Tetzlaff J, Altman D, Laupacis A, Gøtzsche P, Krleža-Jerić K, et al. SPIRIT 2013 Statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(3):200–207. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. INSPIRE Trial Timeline.

Additional file 2. Logic model for Mindfulness and Relaxation.

Additional file 3. Logic model for Strategies for Safety and Wellbeing.

Additional file 4. Reporting checklist for protocol of a clinical trial.

Data Availability Statement

An anonymised quantitative dataset generated and/or analysed during the current study will be available in 2022 once the study has finished. A decision regarding storage location is yet to be finalised, please contact the Principal Investigator or Trials Manager for further information.