Abstract

While it is known that specific nuclei of the brain, for example hypothalamus, contain glucose‐sensing neurons thus their activity is affected by blood glucose level, the effect of glucose modulation on whole‐brain metabolism is not completely understood. Several recent reports have elucidated the long‐term impact of caloric restriction on the brain, showing that animals under caloric restriction had enhanced rate of tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) cycle flux accompanied by extended life span. However, acute effect of postprandial blood glucose increase has not been addressed in detail, partly due to a scarcity and complexity of measurement techniques. In this study, using a recently developed noninvasive MR technique, we measured dynamic changes in global cerebral metabolic rate of O2 (CMRO2) following a 50 g glucose ingestion (N = 10). A time dependent decrease in CMRO2 was observed, which was accompanied by a reduction in oxygen extraction fraction (OEF) with unaltered cerebral blood flow (CBF). At 40 min post‐ingestion, the amount of CMRO2 reduction was 7.8 ± 1.6%. A control study without glucose ingestion was performed (N = 10), which revealed no changes in CMRO2, CBF, or OEF, suggesting that the observations in the glucose study was not due to subject drowsiness or fatigue after staying inside the scanner. These findings suggest that ingestion of glucose may alter the rate of cerebral metabolism of oxygen in an acute setting. Hum Brain Mapp 36:707–716, 2015. © 2014 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Keywords: glucose, cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen, cerebral blood flow, cerebral venous oxygenation, oxygen extraction fraction, T2‐Relaxation‐Under‐Spin‐Tagging MRI

INTRODUCTION

Previous research on the relationship between blood glucose level and the brain has elucidated the important role of several specific structures. For example, hypothalamus is intimately involved in satiation and feeding behavior. It also interacts with other organs such as pancreas and liver to regulate blood glucose level by releasing neurohormones. However, the effect of glucose concentration on the brain may not be limited to these region‐specific ones. As the brain's only substrate for energy production, glucose concentration may have a general physiological effect on brain metabolism and energetics, whether through an independent mechanism or via pathways downstream of hypothalamus activity. While it was traditionally assumed that the brain's metabolic rate should be under homeostatic control and that the concentration of blood glucose should not significantly influence brain metabolism, glucose effect in cortical regions has received increasing attention recently, partly because of several reports suggesting that caloric restriction can mitigate brain atrophy in aging and extend life span [Colman et al., 2009; Lin et al., 2013]. While the life span outcomes in these studies require a long‐term setting, studies of acute effect of blood glucose level may provide important insights on possible mechanisms because of easier control of confounding factors. Given some suggestions that caloric restricted subjects have a greater oxygen metabolic rate [Lin et al., 2013], study of acute effects can help to determine whether these long‐term consequences are causes or effects in the cascade.

Positron emission tomography (PET) using fluorodeoxyglucose radiotracer has been used widely to measure cerebral metabolic rate of glucose (CMRglu) and its application in studies of postprandial glucose effect has been performed. An increase in CMRglu was reported by Tsuchida et al. [Tsuchida et al., 2002]. In contrast, Ishizu et al. reported a reduction of CMRglu in certain brain regions [Ishizu et al., 1994]. A third study by Hasselbalch et al. did not show any changes [Hasselbalch et al., 2001]. Therefore, the findings on glucose metabolic rate in the literature are not conclusive. Moreover, CMRglu does not provide the entire information on the brain's energy consumption as it is also related to cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2).

MRI studies have also been performed to investigate the acute effect of glucose on the brain. Several reports have used hemodynamic markers such as cerebral blood flow (CBF) and Blood‐Oxygenation‐Level‐Dependent (BOLD) MRI signal to examine the influence of glucose ingestion or infusion on the brain, and identified regional increases and decreases in selective regions [Liu et al., 2000; Matsuda et al., 1999; Page et al., 2013; Shapira et al., 2005; Smeets et al., 2007; Tataranni et al., 1999]. However, these effects cannot be directly interpreted as brain metabolism changes due to the complex interplay between neural and vascular responses under physiologic challenges. Thus, a more desirable approach is to simultaneously measure the entire set of parameters including CMRO2, CMRglu, CBF, and oxygenation extraction fraction (OEF) in the same experimental session.

The primary reason that such a study has not been performed previously is due to technical limitations. Existing techniques to measure OEF and CMRO2 rely on the use of 15O‐based PET imaging that requires an onsite cyclotron (unlike CMRglu measurement where the cyclotron can be offsite) and the injection/inhalation of three radiolabeled tracers as well as dynamic sampling of arterial blood [Mintun et al., 1984]. The complexity of the procedures sometimes limits the scope of application and the repeatability of the measurement. Recently, we have developed a novel method that can provide a noninvasive (no exogenous tracer or agent) and reliable (coefficient of variation less than 4%) measurement of CMRO2 on a standard 3T MRI [Liu et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2009, 2011b]. While a global measure only, this method is capable of providing dynamic measurement of postprandial metabolic change at a temporal resolution of 5 min, which represents the state‐of‐the‐art in terms of noninvasive assessment of brain oxygen metabolism. As the glucose effect on brain physiology, if any, is expected to be global, this technique is well suited to examine the question under investigation.

In this study, we used the above technique to examine the potential changes in CBF, venous oxygenation (Y v), OEF, and CMRO2 following an ingestion of 50 g glucose. The convenience of the method afforded us to investigate changes in these parameters continuously in a time dependent manner. In addition, we compared these dynamic changes with those in a control experiment to confirm that the effects can be attributed to the increase in glucose concentration in the blood.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. Each subject gave informed written consent before participating in the study. Twenty healthy subjects were recruited from the University campus through flyers. Ten subjects (25 ± 4 years old, range from 21 to 35, five males and five females, two Caucasians, one Latino and seven Asians) participated in the glucose ingestion study and the other 10 (27 ± 4 years old, range from 23 to 30, six males and four females, four Caucasians, one Latino, one African American and four Asians) participated in a control study. The participants were carefully screened and did not report neurological, psychiatric, endocrine disorders, or diabetes according to self‐completed questionnaires. The participants did not have MR contraindications such as metal implants, pacemaker, neurostimulator, body piercings, or claustrophobia. There was not a significant difference in age, gender, or ethnicity between the glucose ingestion and control groups.

Experimental Procedures

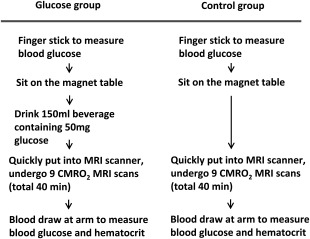

For both glucose ingestion and control studies, participants were required to abstain from food and beverages except for water from 10:00 p.m. the previous night to the beginning of the experiment on the next morning, around 7:30 a.m. Figure 1 illustrates the procedures at the research facility. Fasting state blood glucose concentration was measured using a drop of finger blood with a blood glucose meter (Precision Xtra Blood Glucose & Ketone Monitoring System, Abbott Diabetes Care, Alameda, CA). Then, the participant entered the MR scanner room.

Figure 1.

Diagram of experimental procedures for the glucose ingestion and control study. The glucose ingestion and control experiments used different participants. For the participant in the glucose ingestion study (left column), following consenting and MR screening, a baseline blood glucose level was determined using a finger glucose meter. The subject was then taken into the magnet room and was asked to sit on the magnet table. While sitting on the magnet table, they drank the glucose beverage and were then quickly put into the scanner. Following the MRI scans, they were taken out of the magnet room and, in the control room, a blood sampling was performed. This concluded the study participation, and the subject was discharged. For the participant in the control study (right column), all procedures were identical except that the subject did not drink the beverage.

While sitting on the scanner table, the participant of the glucose ingestion study drank 150 ml glucose tolerance beverage (Thermo Scientific, Middletown, VA) containing 50 g glucose, and was then immediately put inside the magnet bore. We used a fixed amount of glucose instead of a weight‐specific one so that our results can be easily compared to previous literature on this topic [Liu et al., 2000; Matsuda et al., 1999; Page et al., 2013; Smeets et al., 2005], which used a similar approach. The fixed‐amount approach is also the most widely used test in standardized clinical glucose challenge and glucose tolerance tests. The metabolic effects of a 50 g dose of oral glucose are reliable because the digestive absorption of glucose is both efficient and consistent. MR imaging started promptly and a series of nine CBF/Y v/CMRO2 measurements were performed continuously (total duration 40 min). The first set of CBF/Y v/CMRO2 measurement was obtained within 7.4 ± 0.3 (mean ± standard error) minutes after taking the glucose beverage, which is considered the baseline value given the relatively small change in blood glucose level at this early time point [Page et al., 2013; Smeets et al., 2007]. We used this procedure instead of the repositioning scheme (i.e., remove from and enter scanner again) so that data fluctuation due to repositioning inconsistency is minimized and this allows us to perform continuous measurements without gap. The MRI session was followed immediately by a blood sampling (5 ml) in the basilica vein of the arm. A part of the blood was used for the post‐MRI blood glucose measurement using the blood glucose meter. The remaining blood was used to measure macrovascular hematocrit (Hct), which is needed for accurate estimation of cerebral Y v from the MRI measure of T2 [Lu et al., 2012]. The sample was placed in a potassium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid coated tube, and then transferred to capillary tube for centrifuge (Hemata STAT II, Separation Technology, Inc., Altamonte Springs, FL) analysis. Arterial oxygen saturation was measured on the finger with pulse oximetry (Invivo, Gainesville, FL).

The control study was performed to test the possibility that the physiologic changes observed in the glucose study was due to nonglucose related effects such as drowsiness or fatigue caused by lying inside scanner for 40 min. The procedures for the control study were identical to the glucose study except that the participant did not drink glucose beverage (Fig. 1).

Theory for the Measurement of Global CMRO2

Our approach to estimate CMRO2 was based on the Fick principle, similar to previous techniques [Kety and Schmidt, 1948]. The difference between this technique and the previous studies is that our method can measure these parameters in a noninvasive manner with short and simple procedures. CMRO2 can be calculated using:

| (1) |

where CMRO2 is in units of µmol/100 g/min, CBF is in units of ml/100 g/min, Y a and Y v (in percentage, %) are oxygenation in arterial and venous blood, respectively, and C h represents the oxygen carrying capability of hemoglobin and is 8.97 µmol O2/ml blood at typical Hct of 0.44 [Guyton and Hall, 2006]. The actual value of C h used in our calculation was subject‐specific based on the individually determined Hct.

Among the parameters needed to compute CMRO2, the most challenging task has been the measurement of Y v. We have recently developed and validated a technique, T2‐Relaxation‐Under‐Spin‐Tagging (TRUST) MRI, to estimate global Y v in the sagittal sinus [Lu and Ge, 2008; Lu et al., 2012]. This technique was found to be highly reproducible and can be conducted within 1.2 min [Liu et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2011b]. TRUST MRI is based on the principle that blood oxygenation has a known relationship with the blood T2 [Golay et al., 2001; Oja et al., 1999; Silvennoinen et al., 2003]. This technique uses the spin tagging method to isolate pure venous blood signal from surrounding tissue and measures the T2 value of blood, which can be converted to Y v via a calibration plot [Lu et al., 2012]. The term of (Y a − Y v)/Y a is further defined as oxygen extraction fraction (OEF).

Global CBF is measured by a phase‐contrast (PC) quantitative flow technique applied at the feeding arteries at the base of the brain [Haccke et al., 1999]. PC MRI utilizes the phase of an image to encode the velocity of moving spins and has been validated for angiogram and quantitative flow measurements [Bakker et al., 1999; Evans et al., 1993; Zananiri et al., 1991]. Y a in Eq. (1) is measured with the pulse oximetry.

Using these experimental measures and Eq. (1), one can estimate global CMRO2.

MRI Experiment

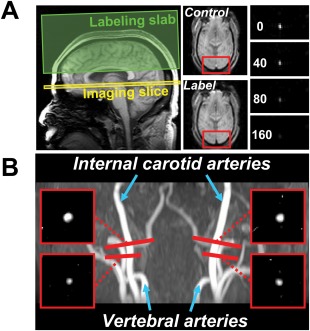

MRI scans were performed on a 3 Tesla MRI system (Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands). The pulse sequences and planning schemes for the CMRO2 measurement were detailed previously [Liu et al., 2013]. Briefly, we first performed an axial 3D time‐of‐flight (TOF) angiogram covering from the third cervical spine to the bottom of pons, to visualize the brain's feeding arteries, internal carotid arteries (ICA), and vertebral arteries (VA). During the angiogram scan, the TRUST imaging slice was planned to be parallel to anterior‐commissure posterior‐commissure line with a distance of 20 mm from the sinus confluence where the superior sagittal sinus (SSS), straight sinus, and transverse sinus join (Fig. 2A). This positioning scheme was previously shown to provide a robust estimation of Y v [Liu et al., 2013]. While the TRUST scan was performed, four PC MRI scans were planned with the slices placed perpendicular to each of the left/right ICA and left/right VA arteries, providing an estimation of CBF (Fig. 2B). One TRUST and four PC scans provide a complete dataset for CMRO2 estimation. The TRUST and PC MRI were repeated for another eight times to obtain a time course of CMRO2.

Figure 2.

Slice positioning and representative image data of MRI scans performed for the CMRO2 estimation. (A) TRUST MRI for the measurement of global venous oxygenation. Left panel: locations of imaging slice and labeling slab. The labeling slab covers the distal portion of the SSS. The imaging slice aims to cover a proximal segment. Middle panel: Representative control and label images from the TRUST scan. Red box indicates an ROI containing the SSS. Right panel: Difference image (i.e., control‐label) inside the ROI containing the SSS. Four difference images are shown, corresponding to increasing effective TE values. The signal intensity decreases with longer TE. (B) PC MRI for the measurement of global CBF. The background image is a TOF angiogram showing left/right internal carotid and VA. The red bars indicate the locations of imaging slices in PC MRI scans. Each scan was placed to be perpendicular to the target artery. The locations of PC MRI on ICA correspond to where they enter the brain. The locations of PC MRI on vertebral arteries are slightly outside the skull, to achieve a perpendicular angle. The resulting PC MRI images are shown in the small red boxes at the corners. For convenience, only the portion of the image that contains the target vessel is shown. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com.]

Imaging parameters of the TRUST MRI were: TR = 3000 ms, TI = 1022 ms, voxel size = 3.44 × 3.44 × 5 mm3, four different T2‐weightings with eTEs of 1 ms (gap between RF pulses < 0.6 ms, as short as attainable), 40, 80, and 160 ms, with a τ CPMG = 10 ms, scan duration = 1.2 min. The labeling slab was 100 mm in thickness and was positioned 22.5 mm above the imaging slice. The PC MRI used: single slice, voxel size = 0.45 × 0.45 × 5 mm3, FOV = 230 × 230 × 5 mm3, maximum velocity encoding = 80 cm/s, four averages, scan duration of one PC MRI scan was 0.5 min. Including scan preparation time, the time to collect each CMRO2 dataset is approximately 4 min. Parameters of TOF angiogram were TR/TE/flip angle = 20 ms/3.45 ms/18°, FOV = 120 × 120 × 60 mm3, voxel size = 1.0 × 1.0 × 1.5 mm3, number of slices = 80, one 60 mm saturation slab positioned above the imaging slab. Scan duration = 50 sec. A T1‐weighted magnetization‐prepared rapid gradient‐echo (MPRAGE) scan was also performed to provide an estimation of brain volume.

Data Processing

Data processing of the TRUST and PC MRI followed methods used previously [Lu and Ge, 2008; Lu et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2009]. Briefly, for the TRUST MRI data (Fig. 2A), after motion correction and pair‐wise subtraction between control and tag images, a preliminary region‐of‐interest (ROI) was manually drawn to include the SSS. To further define the venous voxels, four voxels with the highest signals in the difference images in the ROI were chosen as the final mask for spatial averaging. The venous blood signals were then fitted to a monoexponential function to obtain T2. The T2 was in turn converted to Y v via a calibration plot obtained by the in vitro blood experiments under controlled oxygenation, temperature, and Hct conditions [Lu et al., 2012].

For each PC MRI data (Fig. 2B), a ROI was manually drawn on the targeted artery of each PC MRI scan based on the magnitude image. The operator was instructed to trace the boundary of the targeted artery without including adjacent vessels. The phase signals, that is, velocity values, within the mask were summed to yield the blood flow of each artery. The sum of flow in all four arteries then yielded total CBF to the brain (in ml/min) without accounting for brain volume. To obtain the unit volume CBF values, the total flow was normalized to the parenchyma volume (i.e., gray matter + white matter), which was obtained from tissue segmentation (FSL software, FMRIB Software Library, Oxford University, UK) of the high‐resolution T1 image. Finally, the CBF value was divided by the tissue density of 1.06 g/ml [Herscovitch and Raichle, 1985], resulting in CBF in the unit of ml/100 g/min.

Statistical Analysis

Time course data of CMRO2, CBF, Y v, and OEF was assessed with linear mixed‐effect model using time as a fixed‐effect variable and subject as a random‐effect variable. This model uses data from both the glucose and the control groups to investigate parametric changes over time within each group as well as the differences of the rate of changes between groups. Paired t tests were used to compare parameter values of CMRO2, CBF, Y v, and OEF measured at the first time point to those at the last time point. Differences between glucose and control groups were tested using two‐sample t test. A P < 0.05 is considered a significant effect.

RESULTS

Body mass index (BMI) was 20.7 ± 2.5 kg/m2, and 22.9 ± 4.8 kg/m2 for the glucose group and the control group, respectively. There was not a significant difference in BMI between these two groups (Two‐sampled t test, P > 0.5). Blood glucose levels of the glucose group were 90.0 ± 2.2 mg/dl (mean ± standard error) at fasting state and 141.7 ± 7.5 mg/dl at 40 min after glucose ingestion, showing a significant increase (P < 0.005, paired t test). In the control group, blood glucose levels were 84.9 ± 2.6 mg/dl and 89.0 ± 2.3 mg/dl before and after the MRI session, respectively, with no significant changes (P = 0.21). There were no significant differences between the groups in their baseline blood glucose levels (P = 0.15, two‐sample t test).

Figure 2A, B show representative images from the TRUST and PC MRI, respectively. Baseline (at the first time point) physiological variables were not different between the two groups (Table 1), including CMRO2 (P = 0.50, two‐sample t test), CBF (P = 0.50), Y v (P = 0.11), and OEF (P = 0.18). Other parameters such as Y a and Hct were also comparable between the two groups. Y a were 98.9 ± 0.2 % and 98.5 ± 0.3 % (P = 0.51) for the glucose ingestion and control groups, respectively. Hct were 39.2 ± 1.0% and 39.9 ± 1.5% (P = 0.73) for the glucose ingestion and control, respectively.

Table 1.

MRI measured parameters (mean ± standard errors across subjects) at the first time point (i.e., 7 min after glucose) and the last time point (i.e., 40 min after glucose)

| Condition | CMRO2 (µmol/100 g/min) | CBF (ml/100 g/min) | Y v (%) | OEF (%) | Blood glucose (mg/dl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose ingestion group | |||||

| Pre glucose | 175.3 ±9.0 | 61.0 ± 3.0 | 63.0 ± 1.4 | 35.9 ± 1.6 | 90.0 ± 2.2 |

| Post glucose | 161.9 ± 9.0 | 60.0 ± 2.2 | 65.4 ± 1.2 | 33.5 ± 1.4 | 141.7 ± 7.5 |

| P value | 0.0009 | 0.58 | 0.016 | 0.016 | <0.0001 |

| Control group | |||||

| Pre MR scan | 167.6 ± 6.5 | 58.1 ± 2.7 | 59.8 ± 1.3 | 38.8 ± 1.4 | 84.9 ± 2.6 |

| Post MR scan | 166.7 ± 6.2 | 58.0 ± 2.8 | 59.6 ± 2.1 | 39.0 ± 2.1 | 89.0 ± 2.3 |

| P value | 0.80 | 0.87 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.21 |

P values indicate the significance of difference between two time points using paired t test.

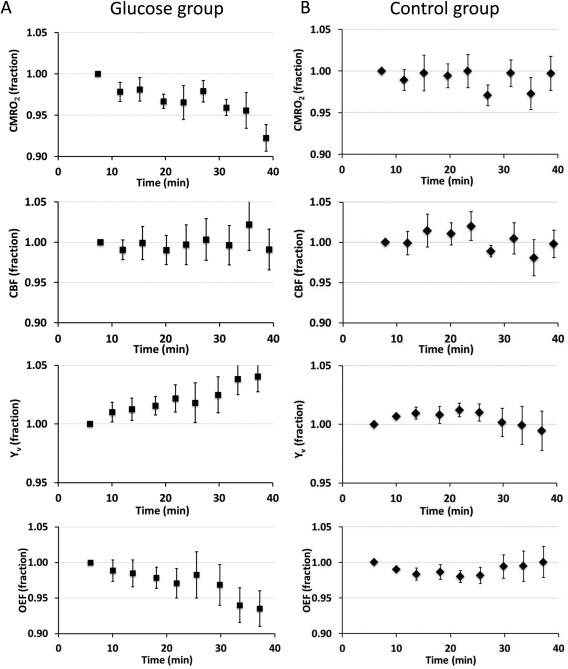

Time courses of the physiologic parameters were used to investigate the dynamic changes associated with postprandial blood glucose increase. Figure 3A shows CMRO2, CBF, Y v, and OEF values in the glucose ingestion group as a function of time. The values have been normalized against the first time point of each individual for the purpose of display. Mixed linear model analysis on the original data revealed that CMRO2 decreased significantly with time (P < 0.001). This reduction was accompanied by a significant decrease in OEF (i.e., an increase in Y v, P = 0.008) in the absence of apparent CBF changes (P = 0.91). In the control group data (Fig. 3B), no significant time dependence was observed in any of the physiologic parameters (P > 0.05 from mixed‐effect model). When analyzing the glucose ingestion and control data in a single model, we found a significant effect of the interaction term, group × time (P = 0.027), on CMRO2, again confirming that CMRO2 in the glucose ingestion group has a time dependence, relative to the control data. OEF (therefore, Y v) also showed a group × time (P = 0.046) interaction. No interaction effect was observed in the CBF data (P = 0.96). No interaction effect was observed for arterial vessel cross‐sectional area (P = 0.98).

Figure 3.

Time courses of relative changes in CMRO2, CBF, Y v, and OEF. The y‐axis values have been normalized against the values of the first time point on an individual basis. Thus, they are shown in fractions and the first time point does not have an error bar. (A) Data from the glucose ingestion group (mean ± SE). Time point “0” indicates the time when the subject finishes the beverage and enters the scanner. (B) Data from the control group. Time point “0” indicates the time when the subject enters the scanner. It can be seen that the glucose ingestion group showed a clear time‐dependence in CMRO2, Y v, and OEF, whereas the control group showed no time‐changes in any of the parameters. Error bar indicates standard error of mean across subjects.

Table 1 shows the values of CMRO2, CBF, Y v, and OEF at the first (7 min after taking glucose beverage) and last (40 min after taking glucose beverage) time points of the MRI session. In the glucose ingestion group, global CMRO2 decreased by 7.8 ± 1.6% or 13.4 ± 2.8 µmol/100 g/min (P < 0.001, paired t test) comparing the last time point to the first time point, suggesting that postprandial blood glucose increase suppressed brain oxidative metabolism. Global CBF was unchanged (P = 0.58) following glucose ingestion. This reduced oxygen consumption in the presence of unaltered blood supply resulted in a reduction in OEF (P = 0.016). No significant differences were observed in the control group for any of the physiologic parameters. Comparing the last time point in the glucose group to the last time point in the control group, CMRO2 was significantly lower (P = 0.01, two‐sample t test of the relative values), suggesting that the effect observed in the glucose ingestion study is not due to confounding factors such as drowsiness or fatigue caused by staying in the magnet for a long time.

DISCUSSION

This study assessed the effect of postprandial blood glucose increase on cerebral metabolism of oxygen in humans. Our data suggest that whole brain CMRO2 decreases in a time dependent manner following 50 g glucose ingestion. At 40 min post‐ingestion, the CMRO2 reduction was approximately 7.8 ± 1.6%. The OEF was also reduced, but CBF was unchanged. The control group data showed minimal time dependence, suggesting that the reduction in cerebral oxygen metabolism observed in the glucose ingestion data was not due to subjects becoming drowsy after being inside the MRI for a while. Collectively, this study demonstrates that postprandial blood glucose increase has a significant effect on global brain physiology aside from the well‐known regional effect on neural activity of certain nuclei.

Physiological Considerations

Many previous studies have examined the effects of glucose concentration on neuronal and glial activities under in vitro settings (for a review, see [Fox et al., 1988a]). High glucose concentration may have several detrimental effects on the central nervous system (CNS). Glucose may cause neurotoxicity via oxidative stress, which is promoted by glucose through a combination of free‐radical generation and impaired free‐radical scavenging. Oxidative stress has been shown to impair cellular function such as axonal transport [Tylenda et al., 1988]. Another effect of high glucose concentration is the glycation of proteins, which may destabilize biological processes and disrupt intracellular signaling [Powers et al., 1988]. Moreover, hyperglycemia may be particularly detrimental to lactate and pyruvate oxidation in glia, compared to that in neurons [Baum et al., 1988].

For human studies, the effects of postprandial hyperglycemia on glucose metabolism (but not oxygen metabolism) have been measured by PET. As mentioned earlier, the results were not entirely consistent, with increased [Tsuchida et al., 2002], decreased [Ishizu et al., 1994], and unchanged [Hasselbalch et al., 2001] glucose metabolism reported in different studies. Using MRI, the effect of postprandial blood glucose increase on CBF and BOLD signal has been investigated previously. The observed changes in hypothalamus, brain nuclei thought to be responsible for satiety and feeding behavior, are relatively consistent across reports, which generally reported signal decreases in hypothalamus following glucose ingestion [Gautier et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2000; Page et al., 2013; Smeets et al., 2005; Smeets et al., 2007; Tataranni et al., 1999]. Outside the vicinity of hypothalamus, the brain's response to glucose intake is less clear and the reports in the current literature are more divergent. Tataranni and colleagues identified insular cortex, limbic and paralimbic areas, deep brain nuclei, and cerebellum as regions with decreased CBF on glucose intake; but also observed CBF increasing regions including ventromedial prefrontal cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and parietal lobule [Gautier et al 2000; Tataranni et al 1999]. Page et al. [2013] conversely, only observed CBF decreasing regions, but no regions with increased CBF [Page et al., 2013].

This work provides additional evidence of an altered brain metabolic rate using MRI‐based CMRO2 measure. We found that CMRO2 was suppressed by a modest amount on an ingestion of 50 g glucose. A whole‐brain‐averaged increase of 7.8% is considered sizable, given that a strong visual stimulation (e.g., checkerboard) only induces a CMRO2 elevation of about 5% [Fox et al., 1988b]. There are a few explanations for this observation that are not mutually exclusive. One is that neurons and/or glia may switch the mode of energy production from predominantly aerobic to partly anaerobic. That is, the brain may increase the rate of glycolysis but decrease the rate of oxidative phosphorylation, thereby reducing oxygen consumption, often referred to as Crabtree effect [Prescott et al., 1988]. Crabtree effects were originally reported in yeast, but have also been observed in several human cell types such as leukocytes, synovial membrane, reticuloeytes, thrombocytes, and certain tumor cells [Prescott et al., 1988]. Certain degree of Crabtree effect may also be present in neurons and glia. However, it should be noted that, as glycolysis is much less efficient in energy production compared to oxidative phosphorylation, one can calculate that the rate of glucose consumption that would have to at least double to fully compensate for the observed (7.8%) reduction in CMRO2. Therefore, even with the Crabtree effect, the total amount of energy that the brain uses is most likely reduced during the postprandial period. This reduced brain energy consumption may be attributed to oxidative stress through free‐radical generations, as elucidated by previous in vitro studies [Fox, 1988; Tylenda et al., 1988], in particular in glial cells [Baum et al., 1988]. Another possibility is that endocrine signals (e.g., insulin, leptin) secondary to blood glucose concentration change may have effects on CNS. Several studies have revealed molecular evidences that insulin can cross brain‐blood‐barrier to act on CNS to control energy balance [Baura et al., 1993; Mayer and Thomas, 1967]. A final potential mechanism is that, in fasting state, the brain may start to use small amount of ketone bodies for fuel source when the blood glucose level is low [Frayn and Humphreys, 2011; Tataranni et al., 1999]. Oxidative metabolism of ketone is known to consume more O2 for the same amount of ATP production due to the absence of the anaerobic glycolysis step [Ito and Quastel, 1970]. Utilizing ketone as energy substrates when blood glucose is low causes CMRO2 to be higher at fasting. Note that these mechanisms may co‐exist to result in the reduced CMRO2 observed in this study.

This study has primarily focused on metabolic and vascular responses to glucose ingestion. We did not perform a continuous measurement of blood glucose concentration, to minimize subject discomfort and reduce motion. For similar reasons, we did not continue experiments beyond 40 min post‐ingestion. Therefore, we were not able to conduct an examination of the temporal relationship between blood glucose change and brain metabolic change. However, by making qualitative comparison between our CMRO2 time‐course and blood glucose curve reported in the literature [Grufferty and Fox, 1988], it appears that the change in CMRO2 is delayed by at least 10 min relative to that in blood glucose level.

This study observed a reduction in CMRO2 while CBF is minimally affected, which is not consistent with the neurovascular coupling principle well known in neural activation studies. We note that CBF is not solely regulated by oxidative metabolism and that there may be other signaling pathways that can regulate CBF. For example, one possible pathway is that lactate production via glycolysis could increase NADH:NAD + ratio, which in turn activates nitric oxide pathway and consequently results in a CBF increase [Lin et al., 2010]. Therefore, metabolic products of the additional glycolytic activity may have a direct vasodilatative effect on CBF, resulting in an apparently unchanged CBF despite a reduction in CMRO2 during postprandial glucose increase. We also note that examples of “uncoupling” between CMRO2 and CBF have been noted in several other physiological challenges. For example, during hypercapnia, CBF is known to be elevated while CMRO2 is either decreased or unchanged [Chen and Pike, 2010; Xu et al., 2011a]. In caffeine ingestion, CBF is reduced while CMRO2 is either elevated or minimally affected [Griffeth et al., 2011]. Therefore, CMRO2 and CBF are not always linearly or even positively correlated during physiological challenges when more than one vasoactive pathways are in play. In fact, this is the reason why simple vascular measure such as CBF is not suitable for studying metabolic effects of physiological challenges.

Technical Considerations

The CMRO2 method used in this study was based on the Fick principle of arteriovenous differences in oxygen contents, in which the contributing parameters were measured individually [Xu et al., 2009]. This principle has been known for decades, but its implementation in humans has been challenging. The main technical obstacle was the difficulty of estimating venous oxygenation quantitatively and reliably. With a recent TRUST MRI technique that was developed by our laboratory, the quantification of global venous oxygenation becomes more feasible [Lu and Ge, 2008]. The TRUST technique has been validated in humans against a gold‐standard pulse oximetry method [Lu et al., 2012]. Compared to other T2‐based oximetry methods [Golay et al., 2001; Oja et al., 1999], a key advantage of the TRUST sequence is that, by conducting a subtraction between control and labeled images, the static tissue signal is canceled out thus partial voluming effect is minimal. Another parameter in the Fick principle, CBF, was determined with a PC MRI technique. PC MRI has previously been validated under both in vitro and in vivo conditions [Bakker et al., 1999; Evans et al., 1993; Zananiri et al., 1991].

The changes in CMRO2 in this study were around 7.8%. To detect a change of this magnitude, the reproducibility of the measurement needs to be considered. The CMRO2 technique used in this study was previously shown to have a coefficient of variation (CoV) of <4%, which appears to be sufficient for this detection [Liu et al., 2013]. We also avoided the subject repositioning in our experimental design, which is useful in controlling additional errors associated with repositioning discrepancies. Our technique is also relatively fast (less than 5 min per measurement) and does not use any exogenous agent, which allowed us to repeat it nine times within our MRI session. This permitted us to obtain a time course of the physiological parameters (Fig. 3), rather than just a two‐point (i.e., pre and post) comparison.

The control group study was important to rule out the confounding factor that the observed CMRO2 change may be caused by drowsiness due to being inside the MRI scanner. The significant effect of the group × time interaction term when using all data (glucose ingestion and control groups) in a single model analysis provided a strong support that the effect observed is attributed to the glucose ingestion. This is also consistent with results when analyzing the data separately that the glucose ingestion group showed significant time dependence yet the control data did not.

A limitation of this study is that the method used does not provide spatial information of CMRO2. Instead, it measures a whole‐brain averaged value only. Therefore, it was not feasible to delineate which brain regions have contributed to this whole‐brain result. It is, therefore, possible that both increases and decreases of CMRO2 are present in the brain in a region‐specific manner, but the decreasing effect was dominant. Another limitation is that the groups were not blinded and the subject knows which study group they were assigned to. It would have been useful to apply a low calorie sweetener in the control experiment to match the sensation. Another possible approach is to use a masking flavor in both test and control experiments so that differences in sensation between experiments can be attenuated [Page et al., 2013]. A final limitation of this study is that we did not measure insulin sensitivity of the test and control participants, thus group differences in subject characteristics are in principle possible. However, given that we specifically screened the subjects for diabetes and that their fasting glucose level was comparable (90.0 ± 2.2 mg/dl and 84.9 ± 2.6 mg/dl for test and control groups, respectively, P = 0.15), the likelihood that the two groups have different insulin sensitivity is low.

CONCLUSIONS

This study investigated effects of postprandial blood glucose increase on cerebral oxidative metabolism and vascular parameters. We found that CMRO2 decreased after 50 g of glucose intake. This was accompanied by a reduction in OEF while CBF was unchanged. These changes were not found in the control study, suggesting that the reduced CMRO2 in the glucose ingestion study was not due to subject drowsiness or fatigue after being inside MRI for a while.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to express gratitude to Yamei Cheng, Sal Pena, and Rani Varghese for assistance with the experiments. The authors are also grateful to Heather Mackey for proofreading the manuscript.

Disclosure/Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Bakker CJ, Hoogeveen RM, Viergever MA (1999): Construction of a protocol for measuring blood flow by two‐dimensional phase‐contrast MRA. J Magn Reson Imaging 9:119–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum BJ, Roberts MW, Brahim JS, Fox PC (1988): The National Institute of Dental Research Clinical Dental Staff Fellowship. J Dent Educ 52:535–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baura GD, Foster DM, Porte D, Jr. , Kahn SE, Bergman RN, Cobelli C, Schwartz MW (1993): Saturable transport of insulin from plasma into the central nervous system of dogs in vivo. A mechanism for regulated insulin delivery to the brain. J Clin Invest 92:1824–1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JJ, Pike GB (2010): Global cerebral oxidative metabolism during hypercapnia and hypocapnia in humans: Implications for BOLD fMRI. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 30:1094–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colman RJ, Anderson RM, Johnson SC, Kastman EK, Kosmatka KJ, Beasley TM, Allison DB, Cruzen C, Simmons HA, Kemnitz JW, Weindruch R (2009): Caloric restriction delays disease onset and mortality in rhesus monkeys. Science 325:201–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans AJ, Iwai F, Grist TA, Sostman HD, Hedlund LW, Spritzer CE, Negro‐Vilar R, Beam CA, Pelc NJ (1993): Magnetic resonance imaging of blood flow with a phase subtraction technique. In vitro and in vivo validation. Invest Radiol 28:109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox PC (1988): Divine or 'natural'. Hosp Pract (Off Ed) 23:16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox PT, Mintun MA, Reiman EM, Raichle ME (1988a): Enhanced detection of focal brain responses using intersubject averaging and change‐distribution analysis of subtracted PET images. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 8:642–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox PT, Raichle ME, Mintun MA, Dence C (1988b): Nonoxidative glucose consumption during focal physiologic neural activity. Science 241:462–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frayn KN, Humphreys SM (2011): Metabolic characteristics of human subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue after overnight fast. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 302:E468–E475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier JF, Chen K, Salbe AD, Bandy D, Pratley RE, Heiman M, Ravussin E, Reiman EM, Tataranni PA (2000): Differential brain responses to satiation in obese and lean men. Diabetes 49:838–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golay X, Silvennoinen MJ, Zhou J, Clingman CS, Kauppinen RA, Pekar JJ, van Zijl PC (2001): Measurement of tissue oxygen extraction ratios from venous blood T(2): Increased precision and validation of principle. Magn Reson Med 46:282–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffeth VE, Perthen JE, Buxton RB (2011): Prospects for quantitative fMRI: Investigating the effects of caffeine on baseline oxygen metabolism and the response to a visual stimulus in humans. Neuroimage 57:809–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grufferty MB, Fox PF (1988): Milk alkaline proteinase. J Dairy Res 55:609–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyton AC, Hall JE (2006): Respiration In: Guyton AC, Hall JE, editors. Textbook of Medical Physiology, 11th ed Saunders, Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Haccke EM, Brown RW, Thompson MR, Venkatesan R (1999): MR Angiography and Flow Quantification. Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Physical Principles and Sequence Design. New York, NY: Wiley Periodicals. [Google Scholar]

- Hasselbalch SG, Knudsen GM, Capaldo B, Postiglione A, Paulson OB (2001): Blood‐brain barrier transport and brain metabolism of glucose during acute hyperglycemia in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86:1986–1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herscovitch P, Raichle ME (1985): What is the correct value for the brain–blood partition coefficient for water? J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 5:65–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizu K, Nishizawa S, Yonekura Y, Sadato N, Magata Y, Tamaki N, Tsuchida T, Okazawa H, Miyatake S, Ishikawa M, Kikuchi H, Konishi J (1994): Effects of hyperglycemia on FDG uptake in human brain and glioma. J Nucl Med 35:1104–1109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T, Quastel JH (1970): Acetoacetate metabolism in infant and adult rat brain in vitro. Biochem J 116:641–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kety SS, Schmidt CF (1948): The effects of altered arterial tensions of carbon dioxide and oxygen on cerebral blood flow and cerebral oxygen consumption of normal young men. J Clin Invest 27:484–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin A‐L, Fox PT, Hardies J, Duong TQ, Gao JH (2010): Nonlinear coupling between cerebral blood flow, oxygen consumption, and ATP production in human visual cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:8446–8451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin A‐L, Coman D, Jiang L, Rothman D (2013): Caloric Restriction Enhances Oxidative Brain Metabolism in Healthy Aging Detected by 1H[13C]MRS. In: Processings of the 21th annual scientific meeting of International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, Salt Lake City, UT. p 0118. [Google Scholar]

- Liu P, Xu F, Lu H (2013): Test‐retest reproducibility of a rapid method to measure brain oxygen metabolism. Magn Reson Med 69:675–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Gao JH, Liu HL, Fox PT (2000): The temporal response of the brain after eating revealed by functional MRI. Nature 405:1058–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Ge Y (2008): Quantitative evaluation of oxygenation in venous vessels using T2‐relaxation‐under‐spin‐tagging MRI. Magn Reson Med 60:357–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Xu F, Grgac K, Liu P, Qin Q, van Zijl P (2012): Calibration and validation of TRUST MRI for the estimation of cerebral blood oxygenation. Magn Reson Med 67:42–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda M, Liu Y, Mahankali S, Pu Y, Mahankali A, Wang J, DeFronzo RA, Fox PT, Gao JH (1999): Altered hypothalamic function in response to glucose ingestion in obese humans. Diabetes 48:1801–1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer J, Thomas DW (1967): Regulation of food intake and obesity. Science 156:328–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintun MA, Raichle ME, Martin WR, Herscovitch P (1984): Brain oxygen utilization measured with O‐15 radiotracers and positron emission tomography. J Nucl Med 25:177–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oja JM, Gillen JS, Kauppinen RA, Kraut M, van Zijl PC (1999): Determination of oxygen extraction ratios by magnetic resonance imaging. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 19:1289–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page KA, Chan O, Arora J, Belfort‐Deaguiar R, Dzuira J, Roehmholdt B, Cline GW, Naik S, Sinha R, Constable RT, Sherwin RS (2013): Effects of fructose vs glucose on regional cerebral blood flow in brain regions involved with appetite and reward pathways. JAMA 309:63–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers WJ, Fox PT, Raichle ME (1988): The effect of carotid artery disease on the cerebrovascular response to physiologic stimulation. Neurology 38:1475–1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott JR, Fox PJ, Akber RA, Jensen HE (1988): Thermoluminescence emission spectrometer. Appl Opt 27:3496–3502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapira NA, Lessig MC, He AG, James GA, Driscoll DJ, Liu Y (2005): Satiety dysfunction in Prader‐Willi syndrome demonstrated by fMRI. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 76:260–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvennoinen MJ, Clingman CS, Golay X, Kauppinen RA, van Zijl PC (2003): Comparison of the dependence of blood R2 and R2* on oxygen saturation at 1.5 and 4.7 Tesla. Magn Reson Med 49:47–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeets PA, de Graaf C, Stafleu A, van Osch MJ, van der Grond J (2005): Functional MRI of human hypothalamic responses following glucose ingestion. Neuroimage 24:363–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeets PA, Vidarsdottir S, de Graaf C, Stafleu A, van Osch MJ, Viergever MA, Pijl H, van der Grond J (2007): Oral glucose intake inhibits hypothalamic neuronal activity more effectively than glucose infusion. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 293:E754–E758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tataranni PA, Gautier JF, Chen K, Uecker A, Bandy D, Salbe AD, Pratley RE, Lawson M, Reiman EM, Ravussin E (1999): Neuroanatomical correlates of hunger and satiation in humans using positron emission tomography. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:4569–4574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchida T, Sadato N, Nishizawa S, Yonekura Y, Itoh H (2002): Effect of postprandial hyperglycaemia in non‐invasive measurement of cerebral metabolic rate of glucose in non‐diabetic subjects. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 29:248–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tylenda CA, Ship JA, Fox PC, Baum BJ (1988): Evaluation of submandibular salivary flow rate in different age groups. J Dent Res 67:1225–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F, Ge Y, Lu H (2009): Noninvasive quantification of whole‐brain cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2) by MRI. Magn Reson Med 62:141–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F, Uh J, Brier MR, Hart J, Jr. , Yezhuvath US, Gu H, Yang Y, Lu H (2011a): The influence of carbon dioxide on brain activity and metabolism in conscious humans. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 31:58–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F, Uh J, Liu P, Lu H (2011b): On improving the speed and reliability of T(2) ‐relaxation‐under‐spin‐tagging (TRUST) MRI. Magn Reson Med 68:198–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zananiri FV, Jackson PC, Goddard PR, Davies ER, Wells PN (1991): An evaluation of the accuracy of flow measurements using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). J Med Eng Technol 15:170–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]