Abstract

Hyperthyroidism may be caused by the development of primary or metastatic thyroid carcinoma. The aim of the present study was to collect recently reported cases of hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma in order to analyze its pathological characteristics, diagnostic procedures and treatment strategies. A PubMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/) search was performed for studies published between January 1990 and July 2017. Full-text articles were identified using the terms, ‘hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma/cancer’, ‘malignant hot/toxic thyroid nodule’, or ‘hyperfunctioning papillary/follicular/Hürthle thyroid carcinoma’. Original research papers, case reports and review articles were included. Among all thyroid carcinoma cases included in the present study, the prevalence of follicular thyroid carcinoma (FTC) was ~10%; however, the prevalence of FTC among hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinomas was markedly higher (46.5% in primary and 71.4% in metastatic disease). The size of hyperfunctioning thyroid tumors was considerably larger compared with that of non-hyperfunctioning thyroid tumors, with a mean size of 4.25±2.12 cm in primary hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinomas. In addition, in cases of metastatic hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma, tumor metastases were widespread or large in size. The diagnosis of primary hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma is based on the following criteria: i) No improvement in thyrotoxicosis following radioactive iodine (RAI) treatment; ii) development of hypoechoic solid nodules with microcalcifications on ultrasound examination; iii) increase in tumor size over a short time period; iv) fixation of the tumor to adjacent structures; and v) signs/symptoms of tumor invasion. The diagnosis of metastatic hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma should be considered in patients suffering from thyrotoxicosis who present with a high number of metastatic lesions (as determined by whole-body scanning), or a history of total thyroidectomy. Surgery is the first-line treatment option for patients with primary hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma, as it does not only confirm the diagnosis following pathological examination, but also resolves thyrotoxicosis and is a curative cancer treatment. RAI is a suitable treatment option for patients with hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma who present with metastatic lesions.

Keywords: thyroid carcinoma, hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma, malignant hot thyroid nodule, hyperthyroidism, metastasis

Introduction

Thyroid carcinoma coexisting with hyperthyroidism is an uncommon occurrence (1), as low thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels can suppress the development and growth of differentiated thyroid carcinoma cells. The majority of nodules in patients with low TSH levels are considered to be benign (NCCN, British Thyroid Association) (1); however, an increasing number of thyroid carcinoma cases are diagnosed in patients with Graves' disease, toxic goiter and functioning thyroid adenoma (2). These thyroid carcinomas may be embedded in or adjacent to a larger hot nodule, and the majority are non-functional. However, previous studies have reported that hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma may present as autonomous functioning thyroid nodules (AFTN) within the thyroid gland, or as functioning lesions in metastatic foci (3–5). In addition, Als et al (3) identified 19 patients with toxic thyroid carcinoma in 2002, while Mirfakhraee et al (5) identified a solitary hyperfunctioning thyroid nodule harboring thyroid carcinoma and reported 76 cases of malignant hot thyroid nodules based on a literature search. Hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinomas are capable of absorbing iodine, as well as synthesizing and releasing thyroxine. Patients with hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinomas may therefore present with clinical thyrotoxicosis. It is considered that this type of hyperthyroidism may be caused by hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma. However, as the incidence of hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma is very low, diagnosis may be delayed and the subsequent choice of treatment may be unsuitable. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to improve our understanding of hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma in order to prevent misdiagnosis and to identify the most effective treatment strategies.

Materials and methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

A literature search of PubMed for studies published in English between January 1990 and July 2017 was performed using the terms, ‘hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma/cancer’, ‘malignant hot/toxic thyroid nodule’, or ‘hyperfunctioning papillary/follicular/Hürthle cell thyroid carcinoma’, followed by a review of the identified articles. Hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma was divided into primary and metastatic. The inclusion criteria for studies involving primary hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma were as follows: i) Thyroid carcinoma, papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC), follicular thyroid carcinoma (FTC) or Hürthle cell carcinoma (HCC); ii) clinical hyperthyroidism with symptomatically or biochemically diagnosed thyrotoxicosis; iii) AFTN, hot or warm nodules (as determined by scintigraphy) and other thyroid tissues with suppressed uptake (99mTc, and/or 131I or 123I); iv) thyroid carcinomas of an identical size to hot or warm nodules, or the absence of hyperplasia in non-cancerous thyroid tissues on pathological analysis. Studies involving cases where the size of the thyroid carcinoma was not identical to that of the hot or warm nodules on scintigraphy, or those where this information was not included, were excluded from the present study, as these tumors may be embedded in hot benign nodules and be non-functional. The inclusion criteria for studies involving metastatic hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma were required to meet aforementioned points i, ii and iii; or i, ii and iv; or a minimum of points i, ii and vi of the following: i) Thyroid carcinoma, PTC, FTC or HCC confirmed by bioptic analysis of the metastatic lesions or thyroid nodule; ii) clinical hyperthyroidism; iii) hyperthyroidism that persists or develops following total thyroidectomy; iv) increased 99mTc, and/or 131I or 123I uptake in the metastatic lesion as determined by scintigraphy. Studies involving cases of persistent euthyroidism following total thyroidectomy were also excluded, as this may indicate functioning but not hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma.

Study selection

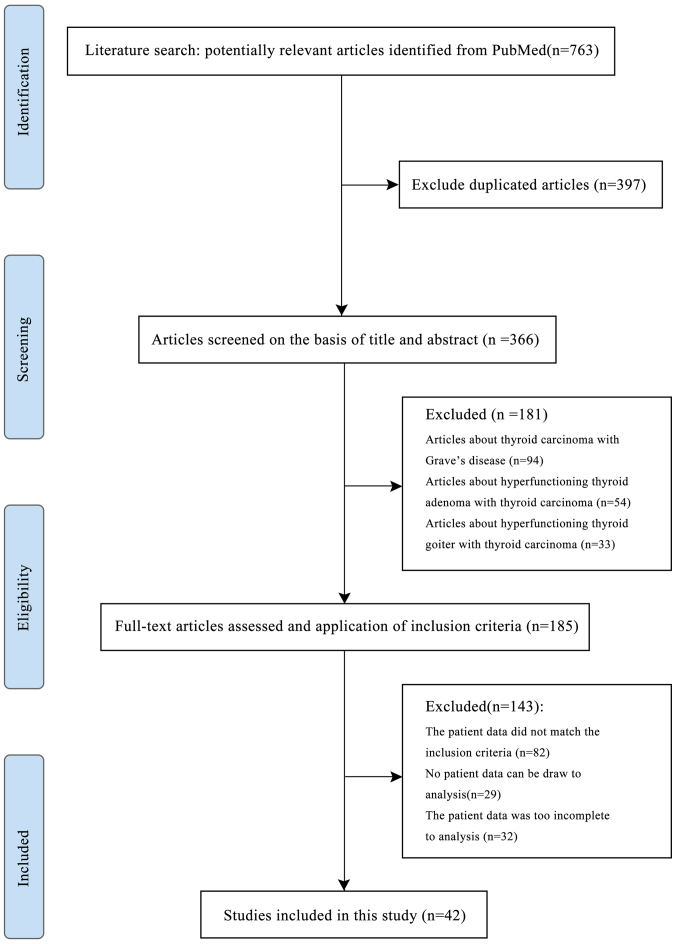

Since the incidence of hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma is very low, the number of cases found on PubMed was small, and the majority of the cases had incomplete data. Of the 763 articles retrieved from PubMed using our search strategy, 397 were duplicated and 324 did not meet the inclusion criteria. Finally, the remaining 42 articles were included in the present study. A detailed flowchart of the study selection process is presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the screening process for study selection.

Results

Primary hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma

The literature search identified 43 cases of primary hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma between 1998 and 2017 (Table I) that fulfilled the inclusion criteria (3,5–28); the full-text versions of the majority of articles published before 1998 were unavailable. The mean age of patients was 50.1±19.0 years (range, 11–79 years) and the female:male ratio was 2.31 (30:13). All patients presented with clinical hyperthyroidism. Biochemical thyrotoxicosis was confirmed in all patients, apart from 11 cases, 5 of which presented with low TSH and normal T3 and T4 levels, and 6 cases with incomplete information. Thyroid scintigraphy analysis (99mTc and/or 131I or 123I) was performed in all but 2 patients, and indicated the presence of hot or warm nodules with suppressed uptake in the remainder of the thyroid gland as AFTN. All 43 cases presented with at least one of the following characteristics, indicating that the hyperfunctioning nodule was in fact the thyroid carcinoma: i) Pathological tumor size identical to the size of the nodule as determined by preoperative thyroid scintigraphy analysis; or ii) the thyroid tissue adjacent to the carcinoma was atrophic or normal. The majority of the cases presented with a single hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma, apart from 2 cases; patient 23 presented with two hyperfunctioning FTCs, and patient 31 presented with 4 hyperfunctioning PTCs. The mean tumor size was 4.25±2.12 cm. A total of 4.7% of the tumors were ≤1.0 cm in size, 11.6% were >1 to ≤2.0 cm, 39.5% were >2 to ≤4.0 cm and 44.2% were >4.0 cm. Details on the preoperative ultrasound parameters were mostly unavailable; however, based on the available information, there were no characteristic findings indicative of thyroid carcinoma (Table I). The results of fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of the thyroid performed on 15 patients identified differentiated thyroid carcinoma (DTC) or suspected DTC in 10 cases, no diagnosis by cytology in 4 cases, and no malignant characteristics in 1 case. In terms of histological subtype, 20 cases (46.5%) were FTC, 21 cases were PTC [including 7 follicular variant PTC (FVPTC)] and 2 cases were HCC.

Table I.

Reported cases of primary hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma.

| A, Study ID, patient characteristics and findings on examination | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | First author | Year | Age, years | Sex | Tumor growth | Pertechnetate | Chemical thyrotoxicosis | FT3 (pmol/l) | FT4 (pmol/l) | TSH (uIU/ml) | AFTN size (cm) | Tumor size (cm) | US | FNA | Pathology | (Refs.) |

| 1 | Appetecchia | 1998 | 23 | F | 3.5→ 4.0 cm | AFTN | Chemical | 11.55↑ | 25.52↑ | 0.11↓ | 3.5/4 | 4 | Inhomogeneous nodule | Gross PTC, 4 PTC, 3 microfoci PTC | (6) | |

| 2 | Mircescu | 2000 | 11 | F | Yes, hyperfunctioning nodule | Chemical | 75↑ | 0.03↓ | 4.5 | 4 | Enlarged with numerous cystic lesions | PTC 4.0 cm, cystic | (7) | |||

| 3 | Bourasseau | 2000 | 47 | M | Yes, hot, solitary | Chemical | ↑ | N | 0.05↓ | 3.5 | 3.5 | Solitary | Suspicious | PTC | (8) | |

| 4 | Bourasseau | 2000 | 36 | M | Yes, hot, solitary | No | N | N | 0.025↓ | 2.5 | 2.5 | Solitary | No diagnostic | FTC | (8) | |

| 5 | Bourasseau | 2000 | 56 | M | Yes, hot, solitary | Chemical | ↑ | 0.03↓ | 5.5 | 5.5 | Solitary | No | FTC | (8) | ||

| 6 | Bourasseau | 2000 | 39 | F | Yes, warm | Chemical | ↑ | ↑ | 0.004↓ | 1 | 1 | Multinodular | Suspicious | PTC | (8) | |

| 7 | Bourasseau | 2000 | 33 | F | Yes, hot | No | N | 0.005↓ | 3 | 3 | Multinodular | Not diagnostic | PTC | (8) | ||

| 8 | Camacho | 2000 | 49 | F | Yes, Hot, AFTN | Chemical | 15.7↑ | 0.04↓ | 3.5 | 3.5 | No | FTC with hemorrhagic central portion | (9) | |||

| 9 | Als | 2002 | 54 | M | Hot, AFTN | Uncertain | 8.5 | 8.5 | No | FTC | (3) | |||||

| 10 | Als | 2002 | 62 | F | Uncertain | Uncertain | No | PTC | (3) | |||||||

| 11 | Als | 2002 | 50 | M | Hot, AFTN | Uncertain | 10 | 10 | No | FTC | (3) | |||||

| 12 | Als | 2002 | 62 | M | Hot, AFTN | Chemical | ↑ | N | ↓ | 8 | 8 | No | FTC | (3) | ||

| 13 | Als | 2002 | 71 | F | Hot, AFTN | Chemical | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | 4 | 4 | No | FTC | (3) | ||

| 14 | Als | 2002 | 69 | F | Hot, AFTN | Chemical | ↑ | N | ↓ | 6 | 6 | No | FTC | (3) | ||

| 15 | Als | 2002 | 55 | F | Hot, AFTN | Uncertain | ↓ | 5.5 | 5.5 | No | FTC | (3) | ||||

| 16 | Als | 2002 | 79 | F | Hot, AFTN (suppression) | Chemical | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | No | FTC | (3) | ||||

| 17 | Als | 2002 | 65 | M | Hot, AFTN | Chemical | ↑ | N | ↓ | 6.5 | 6.5 | No | FTC | (3) | ||

| 18 | Als | 2002 | 56 | M | Hot, AFTN | Chemical | ↑ | N | No | FVPTC | (3) | |||||

| 19 | Als | 2002 | 75 | M | Hot, AFTN | Chemical | ↑ | N | ↓ | 5.5 | 5.5 | No | FTC | (3) | ||

| 20 | Als | 2002 | 77 | F | Hot, AFTN | Chemical | ↑ | N | ↓ | 4 | 4 | No | PTC | (3) | ||

| 21 | Als | 2002 | 71 | F | Hot, AFTN | Chemical | ↑ | ↓ | 6 | 6 | No | FTC | (3) | |||

| 22 | Als | 2002 | 74 | F | Hot, AFTN | Chemical | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | 7 | 7 | No | FTC | (3) | ||

| 23 | Fuhrer | 2003 | 59 | M | Hot, AFTN right, WBS: no uptake in lung | No | N | N | 0.01↓ | 3.5 | 3.5 | One solid with calcification, one solid | Lung FNA: FTC | FTC ×2 | (10) | |

| 24 | Wong | 2003 | 67 | F | Yes, hot, AFTN | Chemical | ↑ | ↓ | 2.5 | 3 | No feature of carcinoma | Hürthle cell carcinoma | (11) | |||

| 25 | Gozu | 2004 | F | Yes, hot 5.0 cm, 2.0 cm hypoactive | Chemical | 9.11↑ | 1.89↑ | 0.005↓ | 5 | 5 | No | PTC (intracystic) | (12) | |||

| 26 | Majima | 2005 | 59 | F | AFTN | Chemical | 4.4↑ | 2.7↑ | 0.01↓ | 1.5 | 1.5 | Hypoechoic with cystic degeneration, calcification | PTC | PTC | (13) | |

| 27 | Bitterman | 2006 | 57 | F | Hot in right, cold in left | Possibly | ? | ? | ? | 6 | 6 | Multinodular | Not diagnostic | FTC | (14) | |

| 28 | Bitterman | 2006 | 59 | F | Hot, 5 cm AFTN | Possibly | ? | ? | ? | 5 | 5 | Solitary nodule | No | FTC | (14) | |

| 29 | Niepomniszcze | 2006 | 64 | F | Yes, AFTN | Chemical | 0.02↓ | 6 | 6 | no | FTC | (15) | ||||

| 30 | Uludag | 2008 | 36 | M | 1.4→ 1.8 cm (11 months) | AFTN | No | N | N | 0.05↓ | 1.4 | 1.5 | Hypoechoic nodule | PTC | PTC | (16) |

| 31 | Nishida | 2008 | 62 | F | 4 hot AFTN in both lobes | Chemical | 5.2↑ | 2.39↑ | 0.007↓ | 2.0, 1.5, 0.6,1.5 | 2.0 | Multinodular | PTC | PTC ×4 | (17) | |

| 32 | Bommired-dipalli | 2010 | 63 | M | Enlarging (5 months) | Yes, AFTN right | Chemical | N | 2.1↑ | 0.01↓ | 4 | 4 | Solid mass | FVPTC? | FVPTC, LN, FVPTC | (18) |

| 33 | Azevedo | 2010 | 47 | F | Enlarging (2 years) | Yes, high iodine uptake AFTN | Chemical | 2.75↑ | 0.05↓ | 2.6 | 3 | Solid nodule | PTC suggestive | FVPTC | (19) | |

| 34 | Giovanella | 2010 | 68 | F | AFTN, no cold area in nodule | Chemical | 7.6↑ | N | 0.006↓ | 5.3 | 5.3 | Hypoechoic nodule | No | FTC | (20) | |

| 35 | Tfayli | 2010 | 11 | F | Yes, predominant AFTN | Chemical | 1.14 | ↓ | 3.5 | 3 | Non-homogenous nodule | Not, diagnostic TC not excluded | PTC | (21) | ||

| 36 | Karanchi | 2012 | 43 | F | AFTN | Chemical | 12.7↑ | 3.1↑ | 0.01↓ | 6.5 | Solid nodule | No | Hürthle cell carcinoma | (22) | ||

| 37 | Nair | 2012 | 38 | M | Hot, AFTN right lobe whole | Chemical | 6.12↑ | 2.9↑ | 0.003↓ | 3.8 | 3 | Hypoechoic with scattered microcalcification | NO | PTC with multifocal microPTC | (23) | |

| 38 | Ruggeri | 2013 | 15 | F | 2.5→ 3.5 cm (6 months) | Yes, AFTN | Chemical | 5.0↑ | 20.15↑ | 0.001↓ | 3.5 | 3.5 | Isoechoic, peripheral halo, blood flow, regular margin | No | FVPTC | (24) |

| 39 | Mirfakhraee | 2013 | 29 | F | 2.4→ 2.7 cm (2 years) | Yes, AFTN | No | N | N | 0.005↓ | 2.7 | 2.5 | Solid, isoechoic, internal Hypervascularity | No | FTC | (5) |

| 40 | Gabalec | 2014 | 15 | F | Hot, AFTN | Chemical | 30.4↑ | 0.01↓ | 4.5 | 4 | Heterogenous, well-demarcated nodule | Follicular neoplasia? | FVPTC | (25) | ||

| 41 | Kuan | 2014 | 60 | F | No mention | Hot, AFTN right lobe whole | Chemical | 7.71↑ | 7.75↓ | 0.005↓ | 8 | 8 | Hypoechoic, avascular, nodule | Follicular neoplasia, FTC? | FVPTC | (26) |

| 42 | Rees | 2015 | 16 | F | Yes, 2.6 cm uptake | Chemical | 14.3↑ | 39.4↑ | 0.03↓ | 4 | 4 | Hyperechoic, hypervascular nodule | DTC? | FVPTC | (27) | |

| 43 | Kadia | 2016 | 37 | F | Enlarging (3 months) | – | Chemical | 23.3↑ | 0.13↓ | 3.6 | 3 | Isoechoic, well-defined homogeneous solid nodule | NO | PTC encapsulated variant | (28) | |

| B, Treatment and outcome | ||||||||||||||||

| No. | First author | Treatment | Pretreatment effect | Surgery outcome | RAI effect and prognosis | Metastatic | (Refs.) | |||||||||

| 1 | Appetecchia | Thyroidectomy + bilateral neck dissection + RAI | Triamazole to euthyroid | Hypothyroid, but anterior cervical tumor residual | No thyrotoxicosis or recurrence | (6) | ||||||||||

| 2 | Mircescu | Right loboisthmectomy/total (2 months) + RAI | Methimazole + blocker | No mention | 8 months, no residual uptake | (7) | ||||||||||

| 3 | Bourasseau | Thyroidectomy | No mention | No mention | No | (8) | ||||||||||

| 4 | Bourasseau | Thyroidectomy | No mention | No mention | No | (8) | ||||||||||

| 5 | Bourasseau | Thyroidectomy | No mention | No mention | No | (8) | ||||||||||

| 6 | Bourasseau | Thyroidectomy | No mention | No mention | No | (8) | ||||||||||

| 7 | Bourasseau | Thyroidectomy | No mention | No mention | No | (8) | ||||||||||

| 8 | Camacho | Thyroidectomy + RAI | No mention | No mention | 3 years, no thyrotoxicosis or recurrence | (9) | ||||||||||

| 9 | Als | Surgery + RAI | Uncertain | Uncertain | 117 months | Yes | (3) | |||||||||

| 10 | Als | Surgery + RAI + PR | Uncertain | Uncertain | 82 months | Yes | (3) | |||||||||

| 11 | Als | Surgery + RAI + PR | carbimazole | Uncertain | 18 months | Yes | (3) | |||||||||

| 12 | Als | Surgery + RAI | Uncertain | Uncertain | 190 months | Yes | (3) | |||||||||

| 13 | Als | RAI + surgery + RAI | Uncertain | Uncertain | 68 months | Yes | (3) | |||||||||

| 14 | Als | Surgery + RAI + PR | Uncertain | Uncertain | 28 months | Yes | (3) | |||||||||

| 15 | Als | Surgery + RAI + PR | Uncertain | Uncertain | 93 months | Yes | (3) | |||||||||

| 16 | Als | RAI + surgery + RAI | Uncertain | Uncertain | 46 months | Liver and sacrum | (3) | |||||||||

| 17 | Als | Surgery + RAI + PR | Uncertain | Uncertain | 107 months | Yes | (3) | |||||||||

| 18 | Als | Surgery + RAI | Uncertain | Uncertain | 208 months alive | No | (3) | |||||||||

| 19 | Als | Surgery + RAI | Uncertain | Uncertain | 181 months | No | (3) | |||||||||

| 20 | Als | Surgery + RAI | Uncertain | Uncertain | 45 months | Uncertain | (3) | |||||||||

| 21 | Als | Surgery + RAI + PR | Uncertain | Uncertain | 44 months | Yes | (3) | |||||||||

| 22 | Als | Surgery + RAI | Uncertain | Uncertain | 76 months alive | Yes | (3) | |||||||||

| 23 | Fuhrer | Total thyroidectomy + RAI - thoracic surgery (8 months) | Euthyroid | Hypothyroid with RAI | Hypothyroid, 8 months thyrotoxicosis control good | Yes | (10) | |||||||||

| 24 | Wong | Lobectomy/total thyroidectomy + RAI | No mention | No mention | No mention | (11) | ||||||||||

| 25 | Gozu | Lobectomy/total thyroidectomy + RAI | Euthyroid | Hypothyroid (6 weeks) | 1 year, no thyrotoxicosis or recurrence | (12) | ||||||||||

| 26 | Majima | Lobectomy | No mention | Hypothyroid (3 months) | No | (13) | ||||||||||

| 27 | Bitterman | Loboisthmectomy + nodule excision/total thyroidectomy | PTU, no clinical improve | Disease-free 1.5 years | No | (14) | ||||||||||

| 28 | Bitterman | Left lobectomy | PTU, intolerance several months | No mention | No | (14) | ||||||||||

| 29 | Niepomniszcze | Lobectomy/total thyroidectomy + RAI | No mention | No mention | 6 months, no thyrotoxicosis or recurrence | (15) | ||||||||||

| 30 | Yazici | RAI→total thyroidectomy + CND | No mention | No recurrence or residual disease | Thyrotoxicosis control, but size increase | (16) | ||||||||||

| 31 | Nishida | Total thyroidectomy | Thiamazole, 5 months to euthyroid | No recurrence and residual disease (1 year) | No | (17) | ||||||||||

| 32 | Bommireddipalli | Total thyroidectomy + RAI | No | No mention | 1 year, TG↑LN +, 1.5 year, LN biopsy + | Yes | (18) | |||||||||

| 33 | Azevedo | Total thyroidectomy + RAI | Methimazole 2 months to euthyroid | True hypothyroidism (2 months) then RAI | 3 years + 2 years no thyrotoxicosis or recurrence | (19) | ||||||||||

| 34 | Giovanella | Right loboisthmectomy + RAI | No | Hypothyroid | 3.4 years, negative | (20) | ||||||||||

| 35 | Tfayli | Lobectomy/total thyroidectomy + RAI | No mention | No mention | 1 year, no thyrotoxicosis or recurrence | (21) | ||||||||||

| 36 | Karanchi | Hemithyroidectomy/total thyroidectomy (1 year) + RAI | No control | Euthyroid (2 weeks) | No | (22) | ||||||||||

| 37 | Nair | Total thyroidectomy + CND + LND + RAI (4 weeks + 6 months) | Carbimazole to euthyroid | No mention | TG 1 year high, LN metastases | Yes | (23) | |||||||||

| 38 | Ruggeri | Surgery | Methimazole to euthyroid | No mention | No | (24) | ||||||||||

| 39 | Mirfakhraee | Left lobectomy | No mention | Euthyroid (6 months) with no recurrence of cancer | No | (5) | ||||||||||

| 40 | Gabalec | Hemithyroidectomy/total thyroidectomy + CND + RAI | Triamazole | No mention | To hypothyroid state | (25) | ||||||||||

| 41 | Kuan | Total thyroidectomy | No mention | No mention | No | (26) | ||||||||||

| 42 | Rees | Left lobectomy + RAI | Carbimazole to euthyroid | No mention | Wel-controlled | (27) | ||||||||||

| 43 | Kadia | Left lobectomy | methimazole + blocker | Euthyroid (2–4 weeks) | No | (28) | ||||||||||

M, male; F, female; AFTN, autonomous functioning thyroid nodule; US, ultrasound; FNA, fine-needle aspiration; PTC, papillary thyroid carcinoma; FTC, follicular thyroid carcinoma; FVPTC, follicular variant papillary thyroid carcinoma; LN, lymph node; RAI, radioactive iodine; PR, preoperative radioactive iodine; CND, central neck dissection; LND, lateral neck dissection; TG, thyroglobulin; WBS, whole-body scanning.

Of the 15 patients pretreated with anti-thyroid drugs, the results indicated disease control to euthyroid in 8 patients, unknown outcome for 4 patients, no disease control in 2 patients and drug intolerance in 1 patient. Thyroid surgery was performed in all patients. In all patients with available information on disease outcome (n=9), thyrotoxicosis was well-controlled by surgery. Radioactive iodine (RAI) treatment was performed preoperatively in 3 patients who had been initially diagnosed with benign AFTN, and postoperatively in 20 patients. As long-term follow-up data were absent for the majority of the patients, and as patients were treated with RAI within a short time period following surgery, it was difficult to evaluate the effect of RAI alone on those patients. However, the available data indicated that only few (14 cases in 43 cases) suffered recurrence of thyrotoxicosis or carcinoma within a short follow-up period [44.5 months (6–208 months)] following thyroid surgery and RAI.

Metastatic hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma

Following a literature search, a total of 28 cases of metastatic hyperfunctioning thyroid cancer were identified (Table II) (3,4,29–44) according to the aforementioned inclusion criteria. All patients had either clinical thyrotoxicosis with biochemical data indicating hyperthyroidism, or been diagnosed as thyrotoxicosis. In addition, all cases (apart from case 56) had a high 99mTc, and/or 131I or 123I uptake in distant lesions, as demonstrated by whole-body scanning. All patients presented with multiple or large metastases to the bone, lungs, liver or mediastinum. The largest metastatic lesion was observed in the liver of patient 62 (17.0 cm). The mean patient age was 61.2±10.8 years, and the female:male ratio was 1.8 (18:10). Histopathological examination revealed that 20 cases were FTC, 5 cases were PTC (including 1 FVPTC), 1 case was insular TC, and 1 case was an unknown type of DTC. A total of 14 patients with metastatic hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma had undergone thyroidectomy, while the remaining 14 patients had no history of thyroidectomy. Thyroid scans were performed in 13 of the 14 cases with no thyroidectomy history, and the results of 6 cases indicated none to normal uptake, cold regions in the thyroid gland and the presence or absence of cold nodules. The remaining 7 cases were diagnosed with AFTN. Thyroid FNAs were performed in 5 cases with no history of thyroidectomy: DTC (1 PTC and 1 FTC) was diagnosed in 2 cases, follicular cells were identified in another 2 cases, and no malignant cells were detected in the remaining case. Biopsies of the metastatic lesions were performed in 3 cases, and the results indicated metastatic DTC. Therefore, of the 14 patients without thyroidectomy, 4 were diagnosed with metastatic hyperfunctioning thyroid cancer, 2 as suspicious and 8 as uncertain.

Table II.

Reported cases of metastatic hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma.

| A, Study ID, patient characteristics and findings on examination | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | First author | Year | Age, years | Sex | Thyroid-ectomy history | Thyroid scan | Whole body scan | Thyroto-xicosis | FT3 (pmol/l) | FT4 (pmol/l) | TSH (uIU/ml) | TG (ng/ml) | Metastatic location | Thyroid FNA | Biopsy on metastasis | Pathology | (Refs.) |

| 44 | Girelli | 1990 | 66 | F | No | Normal, uptake cold nodules | High uptake in distant lesions | Clinical | 0.01↓ | 5,300 | Bone | PTC | Metastatic | PTC PTC | (29) | ||

| 45 | Mizukami | 1994 | 64 | F | No | Hot AFTN 4.0 | High uptake in distant lesions | Clinical | ↓ | Bone | Microfo-llicular | No | FTC | (30) | |||

| 46 | Russo | 1997 | 60 | F | No | Hot AFTN two | High uptake in distant lesions (after surgery) | Clinical | 2.8↑ | N | 0.06↓ | 513 | Lung | No | No | Insular TC | (31) |

| 47 | Salvatori | 1993 | 79 | F | No | Cold areas | High uptake in distant lesions | Clinical | 10.4↑ | 3.8↑ | 0.06↓ | 382 | Lung | FTC | No | FTC | (32) |

| 48 | Als | 2002 | 61 | M | No | Hot AFTN | High uptake in distant lesions | Clinical | Uncertain | No | No | FTC | (3) | ||||

| 49 | Als | 2002 | 65 | F | No | Hot AFTN | High uptake in distant lesions | Clinical | Uncertain | No | No | FTC | (3) | ||||

| 50 | Als | 2002 | 71 | F | No | Hot AFTN | High uptake in distant lesions | Clinical | ↑ | ↓ | Uncertain | No | No | FTC | (3) | ||

| 51 | Als | 2002 | 62 | F | No | Hot AFTN | High uptake in distant lesions | Clinical | ↓ | Uncertain | No | No | FTC | (3) | |||

| 52 | Als | 2002 | 63 | M | No | Hot AFTN | High uptake in distant lesions | Clinical | N | ↓ | Uncertain | No | No | PTC | (3) | ||

| 53 | Sundaraiya | 2009 | 68 | M | No | Cold nodule | High uptake in distant lesions | Clinical | 42.6↑ | 100↑ | ↓ | Rib | No | Rib FTC | FTC multifocal | (33) | |

| 54 | Damle | 2012 | 65 | M | No | – | High uptake in distant lesions | Clinical | 0.03↓ | 300 | Lung, bone | Follicular neoplasm | No | FTC | (34) | ||

| 55 | Damle | 2012 | 62 | M | No | No uptake | High uptake in distant lesions | Clinical | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | 300 | Bone | No | Metastatic FTC | (34) | |

| 56 | Gardner | 2014 | 66 | F | No | Diffuse reduction | No WBS | Clinical | 25.1↑ | 37.9↑ | 0.006↓ | Lung, bone | No malignant cells | FVPTV | (35) | ||

| 57 | Kunawudhi | 2016 | 43 | F | No | Cold | High uptake in distant lesions | Clinical | 32.55↑ | 6.34↑ | 0.026↓ | Bone, liver | No | No | FTC | (36) | |

| 58 | Abs | 1991 | 57 | F | Partial thyroid-ectomy | Normal | High uptake in distant lesions | Clinical | 0.6↓ | 640 | Mediasti-num | FTC | (37) | ||||

| 59 | Lorberb-oym | 1996 | 67 | F | Total thyroid-ectomy | High uptake in distant lesions | Clinical | 273↑ | 15.7↑ | 0.1↓ | Hemipelvis | FTC | (38) | ||||

| 60 | Yoshimura | 1997 | 61 | M | Total thyroidectomy + RAI + hip replacement | High uptake in distant lesions | Clinical | 46.1↑ | 105.3↑ | 0.05↓ | 329 | Pelvis | FTC | (39) | |||

| 61 | Salvatori | 1993 | 69 | F | Partial thyroidectomy | Low uptake | High uptake in distant lesions | Clinical | 3.8↑ | 10.4↑ | 0.06↓ | 48,680 | Lung | DTC | (32) | ||

| 62 | Guglielmi | 1999 | 58 | F | Subtotal thyroidectomy | High uptake in distant lesions | Clinical | 18.4↑ | 44.5↑ | 0.1↓ | 3,686 | Liver, lung | Liver FTC | FTC | (40) | ||

| 63 | Basaria | 2002 | 74 | M | Total thyroidectomy 8 years | High uptake in distant lesions | Clinical | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | 2,280 | Mediastinum and lung | PTC | (41) | |||

| 64 | Orsolon | 2008 | 66 | M | Total thyroidectomy | High uptake in distant lesions | Clinical | 4.5↑ | 1.6 | <0.1↓ | >10,000 | Bone, lung | FTC | (42) | |||

| 65 | Tan | 2009 | 39 | F | Total thyroidectomy + hip replacement + RAI | High uptake in distant lesions (FDG) | Clinical | 27.9↑ | 4.41↑ | 0.01↓ | 1,000 | Pelvic mass | FTC | (43) | |||

| 66 | Nishihara | 2010 | 59 | F | Total thyroidectomy + EBRT | High uptake in distant lesions | Clinical | ↑ | ↑ | 0.01↓ | 8,000 | Multiple bone and lung | FTC | (44) | |||

| 67 | Qiu | 2015 | 45 | M | Total thyroidectomy | High uptake in distant lesions | Clinical | 13.42↑ | 33.9↑ | 0.04↓ | Bone | FTC | (4) | ||||

| 68 | Qiu | 2015 | 75 | M | Total thyroidectomy | High uptake in distant lesions | Clinical | 9.35↑ | 27.18↑ | 0.24↓ | Lung | PTC | (4) | ||||

| 69 | Qiu | 2015 | 43 | F | Total thyroidectomy | High uptake in distant lesions | Clinical | 7.23↑ | 29.14↑ | 0.22↓ | Bone | FTC | (4) | ||||

| 70 | Qiu | 2015 | 51 | F | Total thyroidectomy | High uptake in distant lesions | Clinical | 9.51↑ | 31.73↑ | 0.02↓ | Bone, lung | FTC | (4) | ||||

| 71 | Qiu | 2015 | 54 | F | Total thyroidectomy | High uptake in distant lesions | Clinical | 7.83↑ | 32.15↑ | 0.01↓ | Bone | FTC | (4) | ||||

| B, Treatment and outcome | |||||||||||||||||

| No. | First author | Pretreatment antithyroid drug | Treatment | Surgery outcome | Response to RAI | (Refs.) | |||||||||||

| 44 | Girelli | Thyrotoxicosis to subhyperthyroidism | Total thyroidectomy + RAI | Persistent | Hyperthyroidism persisting 6 months after RAI | (29) | |||||||||||

| 45 | Mizukami | Unknown | RAI | – | Persistent after 2 RAI | (30) | |||||||||||

| 46 | Russo | Unknown | Subtotal thyroidectomy/1 year total + RAI 2 | Mild hyperthyroidism | Hypothyroid, TG remains high (2 years) | (31) | |||||||||||

| 47 | Salvatori | Effect not shown | Total thyroidectomy + RAI | Improved only 1 month | Hyperthyroidism persisting 4 months after RAI | (32) | |||||||||||

| 48 | Als | Unknown | RAI + surgery + RAI | Persistent | 27 months, died | (3) | |||||||||||

| 49 | Als | Unknown | RAI + surgery + RAI | Persistent | 39 months, died | (3) | |||||||||||

| 50 | Als | Unknown | Surgery + RAI | Persistent | 229 months, died | (3) | |||||||||||

| 51 | Als | Unknown | Surgery + RAI | Persistent, possible improvement | 10 months, died | (3) | |||||||||||

| 52 | Als | Unknown | Surgery + RAI | Persistent | 71 months, died | (3) | |||||||||||

| 53 | Sundaraiya | Effect not shown | Total thyroidectomy + RAI | Persistent | 3 months RAI hypothyroid with tumor control | (33) | |||||||||||

| 54 | Damle | Thyrotoxicosis difficult to control | Subtotal thyroidectomy + RAI | Improved only 2 months | 5 years of no recurrence of thyrotoxicosis | (34) | |||||||||||

| 55 | Damle | Thyrotoxicosis difficult to control | RAI | – | 3 years of no recurrence of thyrotoxicosis | (34) | |||||||||||

| 56 | Gardner | Thyrotoxicosis difficult to control | Total thyroidectomy + RAI | Died of thyroid storm 12 days postoperatively | – | (35) | |||||||||||

| 57 | Kunawudhi | Effect not shown | Total thyroidectomy + right LND + RAI + EBRT | Persistent | 2 years, progressive disease | (36) | |||||||||||

| 58 | Abs | Thyrotoxicosis difficult to control | Rib biopsy + RAI, good | RAI 9 years, no metastases | (37) | ||||||||||||

| 59 | Lorberboym | Pretreatment to euthyroid +EBRT to hypothyroid | Pretreatment + EBRT + RAI | 4 weeks RAI hypothyroid | (38) | ||||||||||||

| 60 | Yoshimura | No mention | RAI + pretreatment | Rapid improvement 1.5 years survival | (39) | ||||||||||||

| 61 | Salvatori | Effect not shown | RAI | Hyperthyroidism persisting 6 months after RAI | (32) | ||||||||||||

| 62 | Guglielmi | Failure to control thyrotoxicosis | ILP + RAI | 1.5 years good control | (40) | ||||||||||||

| 63 | Basaria | Good control | Pretreatment + RAI | 3 months hypothyroid | (41) | ||||||||||||

| 64 | Orsolon | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | (42) | ||||||||||||

| 65 | Tan | Worsening | Removal of pelvis mass and partial bone | Thyrotoxicosis disappeared | Resistant to RAI | (43) | |||||||||||

| 66 | Nishihara | Unknown | RAI low multiple | 10 months after RAI, toxicosis control, but tumor progression, 8 years of survival | (44) | ||||||||||||

| 67 | Qiu | Unknown | RAI + palliative resection | Effect not clearly shown | |||||||||||||

| 68 | Qiu | Unknown | RAI | Effect not clearly shown | (4) | ||||||||||||

| 69 | Qiu | Unknown | RAI + palliative resection | Effect not clearly shown | (4) | ||||||||||||

| 70 | Qiu | Unknown | RAI + palliative resection | Effect not clearly shown | (4) | ||||||||||||

| 71 | Qiu | Unknown | RAI | Effect not clearly shown | (4) | ||||||||||||

M, male; F, female; RAI, radioactive iodine; EBRT, external beam radiation therapy; AFTN, autonomous functioning thyroid nodule; FNA, fine-needle aspiration; PTC, papillary thyroid carcinoma; FTC, follicular thyroid carcinoma; FVPTC, follicular variant papillary thyroid carcinoma; TC, thyroid carcinoma; DTC, differentiated thyroid carcinoma; LND, lateral neck dissection; ILP, interstitial laser photocoagulation; TG, thyroglobulin; LN, lymph node.

The results demonstrated that, of the 13 patients who underwent pretreatment with anti-thyroid medication, 6 experienced difficulties or were unable to control thyrotoxicosis, while only 3 patients became euthyroid. The outcome of thyrotoxicosis in the remaining 4 patients was uncertain. Total or subtotal thyroidectomy was performed in 12 of 14 cases without a history of thyroidectomy. One patient succumbed to thyroid crisis at 12 days post-surgery. Following surgery, thyrotoxicosis persisted in 8 patients, while a transient improvement was observed in 3 patients. All patients underwent multi-dose RAI, apart from 2 patients (patient 56 succumbed to the disease and the outcome of patient 64 is unknown). Following RAI, the majority of the patients exhibited a significant improvement in hyperthyroidism and good cancer control; however, thyrotoxicosis in patient 44 persisted for up to 6 months. Patients 55 and 58 experienced no recurrence of thyrotoxicosis or cancer during a follow-up period of 3 or 9 years, respectively following RAI treatment. Of particular note, patient 65 developed RAI resistance 4 years after the first dose of RAI. This patient's thyrotoxicosis was caused by pelvic metastasis, which was cleared following surgical removal of the pelvic mass.

Discussion

Thyroid carcinoma coexisting with hyperthyroidism is rare and is more commonly encountered among younger, female patients (5). Diagnosis relies on clinical and histopathological correlation. On histopathological examination, the lack of hyperplastic thyroid tissue often suggests a hyperfunctioning thyroid cancer (28).

The results of the present study have several implications, as discussed below. First, the prevalence of different histological subtypes of hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma was investigated in the present study. The results indicated that 46.5% of primary hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinomas and 71.4% (20/28) of metastatic hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinomas were of the FTC subtype. Mirfakhraee et al (5) reported that 36.4% (28/77) of solitary hyperfunctioning thyroid nodules harboring a thyroid carcinoma, in which the majority are primary hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinomas, were of the FTC subtype. Qiu et al (4) reported that the prevalence of FTC in functioning metastatic thyroid carcinoma was 60.5% (23/38), of which 5 cases were hyperfunctioning. By comparison, the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) cancer registry program (1974–2013) (45), which records all histological thyroid cancer cases as a single group, indicates that the prevalence of FTC is 10.8% and that of PTC is 83.6%. Therefore, there appears to be a higher prevalence of FTC among patients with hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma, and a particularly high prevalence among patients with metastatic disease. This suggests that hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma may be more likely to occur in either primary or metastatic FTC when compared with PTC. The reason for this is unknown. The results presented by Qiu et al (4) indicate that the prognosis of patients with metastatic hyperfunctioning FTC is worse compared with that for patients with PTC.

Tumor size is an additional important factor to consider for hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma. In the present study, the mean tumor size of primary hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma was observed to be 4.25±2.12 cm. These results are consistent with those presented by Mirfakhraee et al (5), who reported a mean tumor size of 4.13±1.68 cm in malignant hot nodules (the majority of which were hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinomas). By comparison, the SEER cancer registry program (1974–2013) (45) reports that 28.6% of thyroid carcinomas are ≤1.0 cm in size, 26.0% are >1.0 to ≤2.0 cm, 23.0% are >2.0 to ≤4.0 cm, 9.6% are >4.0 cm and 13.0% are unknown. Pazaitou-Panayiotou et al (2) conducted a well-organized review, which demonstrated that the majority of non-functioning thyroid carcinomas that coexist with Graves' disease, toxic nodule goiter or hyperfunctioning adenoma, are microcarcinomas (35.0–88.0%). In addition, similar characteristics were observed in these metastatic hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma patients. It is considered that large primary or metastatic tumors may synthesize excessive thyroid hormones more readily, which may cause hyperthyroidism. Somatic mutations in TSH receptor genes may explain the hyperthyroidism caused by thyroid cancer. These mutations activate the intracellular cAMP cascade, induce hormone production and, ultimately, lead to hyperthyroidism (28,46). Pringle et al (47) observed that thyroid-specific knockout of PrkarIa leads to hyperthyroidism and thyroid cancer in mice. Moreover, they suggested that another genetic mutation may be implicated in metastasis, apart from PrkarIa mutation in the thyroid (47). As DTC cells have similar functions to normal thyroid follicular cells, such as TSH-dependence, absorption of iodine and secretion of thyroglobulin, DTC cells may also secrete thyroxine. When autoregulation mechanisms are impeded, such as in Graves' disease, large DTCs may secrete excessive amounts of thyroxine resulting in hyperthyroidism. These results also indicate that debulking surgery may play a key role in the treatment of this rare disease.

As regards the diagnosis of hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma, it is difficult to distinguish malignant from benign AFTN, as they share common characteristics, such clinical thyrotoxicosis with hot nodules on thyroid scintigraphy. However, the following factors may help determine whether thyrotoxicosis is the result of primary hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma: i) No improvement in thyrotoxicosis following RAI treatment (patient 30 in the present systematic review) (16); ii) ultrasound results indicating the presence of hypoechoic solid nodules with microcalcifications (patients 23 and 37 in the present systematic review) (10,23); and iii) tumor growth over a short time period (patient 32 and 43 in the present systematic review) (18,28). Additional risk factors for malignancy were also reported, such as age (<20 or >60 years), male sex, a family history of DTC, a previous history of head or neck irradiation, tumor fixation to adjacent structures and symptoms of tumor invasion (3,5). Most importantly, AFTN should not be considered to rule out the possibility of malignant thyroid tumor. The applicability of thyroid FNA in differentiating malignant from benign AFTN is limited. This is because ~50% of primary hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinomas are FTCs, which are difficult to distinguish from follicular adenoma by FNA. However, if follicular neoplasms in the thyroid nodule are detected by FNA, combined with high uptake in distant lesions on whole-body scan images and thyrotoxicosis, a diagnosis of metastatic hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma, FTC or FVPTC should be considered. Of the 5 metastatic hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma patients who underwent FNA, 2 cases were DTC (1 PTC and 1 FTC) and 2 cases were follicular neoplasms; therefore, these 4 patients were diagnosed with metastatic hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma. FNA may therefore facilitate the diagnosis of hyperfunctioning metastatic thyroid carcinoma. In 13 of 14 patients with no history of thyroidectomy who underwent thyroid scans, 6 cases demonstrated no increased uptake in the thyroid gland. For these patients, and for patients who develop thyrotoxicosis following total/subtotal thyroidectomy, a diagnosis of metastatic hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma should be considered and a whole-body scan should be performed with other additional imaging methods in order to identify metastatic lesions. Core needle aspiration and pathological analysis by H&E staining may also facilitate the diagnosis of primary or metastatic thyroid carcinoma. Hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma will require diagnosis by FNA or core needle aspiration and whole-body scanning, as well as confirmation of clinical thyrotoxicosis.

Drug management is considered more suitable for primary hyperthyroidism with Graves' disease. However, based on our clinical experience, favorable clinical benefits may be achieved with early surgery in cases with secondary hyperthyroidism caused by nodular goiter or thyroid adenoma. Furthermore, surgery can effectively cure patients with hyperthyroidism with non-functioning thyroid carcinomas. For the treatment of hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma, the primary aim is to control hyperthyroidism, as well as the cancer itself. Therefore, surgery, particularly total thyroidectomy, is the first-line treatment option for patients with primary hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma, as it does not only confirm the diagnosis following pathological examination, but also resolves thyrotoxicosis and cures the cancer. Of the 43 patients in the present study, all except 4 patients diagnosed preoperatively by FNA, were diagnosed with thyroid carcinoma following thyroid surgery. In addition, all 43 patients developed euthyroidism/hypothyroidism within a short time-period following surgery. However, total thyroidectomy may not be the optimal first-line treatment option for patients with hyperfunctioning metastatic lesions with non-functioning primary thyroid carcinoma (as indicated by no increased uptake on thyroid scintigraphy). This is because a total thyroidectomy is unable to control thyrotoxicosis and may even lead to deterioration, as the majority of hormones are produced by metastatic lesions. Of the 5 cases who had undergone total or subtotal thyroidectomy, postoperative thyrotoxicosis persisted in 3 patients, transient improvements were observed in 1 patient, and the remaining patient succumbed to thyroid crisis 12 days after surgery. In addition, the significance of total thyroidectomy in terms of 131I therapy was markedly lower in patients with low thyroid bed 131I uptake and intense 131I uptake in distant metastatic lesions. However, for patients with functional primary and metastatic tumors, total thyroidectomy may be the optimal primary treatment option, as it eliminates the hot primary thyroid carcinoma, which produces a certain amount of thyroid hormones, removes the thyroid gland and reduces the 131I dose required to treat the metastatic lesions. In addition, total thyroidectomy and subsequent pathological diagnosis may be particularly useful for patients who have not undergone a preoperative FNA.

RAI is necessary for treating hyperfunctioning metastatic lesions in patients with thyroid carcinoma (4); it is a first-line treatment option for patients with a history of thyroidectomy or for those with no increased uptake in the thyroid gland. To avoid a possible thyroid storm, pretreatment with antithyroid medication is required. Fractionated RAI (as for patient 66 in the present systematic review) (44), or minimal invasive local ablation may also be considered (as for patient 62 in the present systematic review) (40). If the metastatic lesion is resistant to RAI and the functioning lesion resectable, surgery may be considered as a treatment option. This was demonstrated in patient 65 (43), whose thyrotoxicosis disappeared following surgical removal of the functioning pelvic mass. However, it is difficult to evaluate the efficiency of RAI following surgery in patients with primary functioning thyroid carcinoma without metastasis. As the majority of primary hyperfunctioning thyroid tumors were large, and metastasis was reported during follow-up post-surgery, RAI was considered as a treatment option following surgery in patients with primary hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma (12,19).

In conclusion, the results of the present study indicated that the size of hyperfunctioning thyroid tumors is markedly larger, and primary or metastatic FTC is more commonly hyperfunctioning compared with PTC. FNA or core needle aspiration together with whole-body scanning may play a key role in the diagnosis of clinical thyrotoxicosis. In addition, surgery and RAI are the preferred treatments for primary and metastatic hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma, respectively. However, there were certain limitations to the present study: We evaluated studies using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale and the scores of the studies ranged 2–4. Considering that the number of hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinomas is small and most studies are published as case reports, a risk of bias may exist and the results must be interpreted with caution.

Acknowledgements

JL gratefully acknowledges the support of Shanghai Jiao Tong University K.C. Wong Medical Fellowship Fund (2017) and Program of Foreign Visiting Studies of Young Teachers in Shanghai Colleges and Universities (2017). The authors would like to thank Xiaoyun Xu for proofreading the article.

Funding

The present study was funded by the Shanghai Jiao Tong University K.C. Wong Medical Fellowship Fund (2017) and the Program of Foreign Visiting Studies of Young Teachers in Shanghai Colleges and Universities (2017).

Availability of data and materials

All the datasets generated and analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

JL conceived the study and drafted and wrote the manuscript, YW and DD collected the data, MZ analyzed and interpreted the data and provided the clinical suggestion. All the authors have read and approved the final version of this manuscript for publication.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All the authors declare that they have no competing interests to disclose.

References

- 1.Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, Doherty GM, Mandel SJ, Nikiforov YE, Pacini F, Randolph GW, Sawka AM, Schlumberger M, et al. 2015 American thyroid association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: The American thyroid association guidelines task force on thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2016;26:1–133. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pazaitou-Panayiotou K, Michalakis K, Paschke R. Thyroid cancer in patients with hyperthyroidism. Horm Metab Res. 2012;44:255–262. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1299741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Als C, Gedeon P, Rösler H, Minder C, Netzer P, Laissue JA. Survival analysis of 19 patients with toxic thyroid carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:4122–4127. doi: 10.1210/jc.2001-011147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qiu ZL, Shen CT, Luo QY. Clinical management and outcomes in patients with hyperfunctioning distant metastases from differentiated thyroid cancer after total thyroidectomy and radioactive iodine therapy. Thyroid. 2015;25:229–237. doi: 10.1089/thy.2014.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mirfakhraee S, Mathews D, Peng L, Woodruff S, Zigman JM. A solitary hyperfunctioning thyroid nodule harboring thyroid carcinoma: Review of the literature. Thyroid Res. 2013;6:7. doi: 10.1186/1756-6614-6-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Appetecchia M, Ducci M. Hyperfunctioning differentiated thyroid carcinoma. J Endocrinol Invest. 1998;21:189–192. doi: 10.1007/BF03347300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mircescu H, Parma J, Huot C, Deal C, Oligny LL, Vassart G, Van Vliet G. Hyperfunctioning malignant thyroid nodule in an 11-year-old girl: Pathologic and molecular studies. J Pediatr. 2000;137:585–587. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.108437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bourasseau I, Savagner F, Rodien P, Duquenne M, Reynier P, Guyetant S, Bigorgne JC, Malthièry Y, Rohmer V. No evidence of thyrotropin receptor and G(s alpha) gene mutation in high iodine uptake thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid. 2000;10:761–765. doi: 10.1089/thy.2000.10.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Camacho P, Gordon D, Chiefari E, Yong S, DeJong S, Pitale S, Russo D, Filetti S. A Phe 486 thyrotropin receptor mutation in an autonomously functioning follicular carcinoma that was causing hyperthyroidism. Thyroid. 2000;10:1009–1012. doi: 10.1089/thy.2000.10.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Führer D, Tannapfel A, Sabri O, Lamesch P, Paschke R. Two somatic TSH receptor mutations in a patient with toxic metastasising follicular thyroid carcinoma and non-functional lung metastases. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2003;10:591–600. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0100591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong CP, AuYong TK, Tong CM. Thyrotoxicosis: A rare presenting symptom of Hurthle cell carcinoma of the thyroid. Clin Nucl Med. 2003;28:803–806. doi: 10.1097/01.rlu.0000089667.15648.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gozu H, Avsar M, Bircan R, Claus M, Sahin S, Sezgin O, Deyneli O, Paschke R, Cirakoglu B, Akalin S. Two novel mutations in the sixth transmembrane segment of the thyrotropin receptor gene causing hyperfunctioning thyroid nodules. Thyroid. 2005;15:389–397. doi: 10.1089/thy.2005.15.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Majima T, Doi K, Komatsu Y, Itoh H, Fukao A, Shigemoto M, Takagi C, Corners J, Mizuta N, Kato R, Nakao K. Papillary thyroid carcinoma without metastases manifesting as an autonomously functioning thyroid nodule. Endocr J. 2005;52:309–316. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.52.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bitterman A, Uri O, Levanon A, Baron E, Lefel O, Cohen O. Thyroid carcinoma presenting as a hot nodule. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:888–889. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niepomniszcze H, Suárez H, Pitoia F, Pignatta A, Danilowicz K, Manavela M, Elsner B, Bruno OD. Follicular carcinoma presenting as autonomous functioning thyroid nodule and containing an activating mutation of the TSH receptor (T620I) and a mutation of the Ki-RAS (G12C) genes. Thyroid. 2006;16:497–503. doi: 10.1089/thy.2006.16.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uludag M, Yetkin G, Citgez B, Isgor A, Basak T. Autonomously functioning thyroid nodule treated with radioactive iodine and later diagnosed as papillary thyroid cancer. Hormones (Athens) 2008;7:175–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03401510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishida AT, Hirano S, Asato R, Tanaka S, Kitani Y, Honda N, Fujiki N, Miyata K, Fukushima H, Ito J. Multifocal hyperfunctioning thyroid carcinoma without metastases. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2008;35:432–436. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bommireddipalli S, Goel S, Gadiraju R, Paniz-MondolFi A, DePuey EG. Follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma presenting as a toxic nodule by I-123 scintigraphy. Clin Nucl Med. 2010;35:770–775. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3181e4dc7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Azevedo MF, Casulari LA. Hyperfunctioning thyroid cancer: A five-year follow-up. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2010;54:78–80. doi: 10.1590/S0004-27302010000100013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giovanella L, Fasolini F, Suriano S, Mazzucchelli L. Hyperfunctioning solid/trabecular follicular carcinoma of the thyroid gland. J Oncol. 2010;2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/635984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tfayli HM, Teot LA, Indyk JA, Witchel SF. Papillary thyroid carcinoma in an autonomous hyperfunctioning thyroid nodule: Case report and review of the literature. Thyroid. 2010;20:1029–1032. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.0144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karanchi H, Hamilton DJ, Robbins RJ. Hürthle cell carcinoma of the thyroid presenting as thyrotoxicosis. Endocr Pract. 2012;18:e5–e9. doi: 10.4158/EP11142.CR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nair CG, Jacob P, Babu M, Menon R. Toxic thyroid carcinoma: A new case. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:668–670. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.98047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruggeri RM, Campenni A, Giovinazzo S, Saraceno G, Vicchio TM, Carlotta D, Cucinotta MP, Micali C, Trimarchi F, Tuccari G, et al. Follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma presenting as toxic nodule in an adolescent: Coexistent polymorphism of the TSHR and Gsα genes. Thyroid. 2013;23:239–242. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gabalec F, Svilias I, Plasilova I, Hovorkova E, Ryska A, Horacek J. Follicular variant of papillary carcinoma presenting as a hyperfunctioning thyroid nodule. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2014;36:e94–e96. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000000036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuan YC, Tan FH. Thyroid papillary carcinoma in a ‘hot’ thyroid nodule. QJM. 2014;107:475–476. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hct204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rees DO, Anthony VA, Jones K, Stephens JW. Follicular variant of papillary thyroid carcinoma: An unusual cause of thyrotoxicosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-207091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kadia BM, Dimala CA, Bechem NN, Aroke D. Concurrent hyperthyroidism and papillary thyroid cancer: A fortuitous and ambiguous case report from a resource-poor setting. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9:369. doi: 10.1186/s13104-016-2178-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Girelli ME, Casara D, Rubello D, Pelizzo MR, Busnardo B, Ziliotto D. Severe hyperthyroidism due to metastatic papillary thyroid carcinoma with favorable outcome. J Endocrinol Invest. 1990;13:333–337. doi: 10.1007/BF03349573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mizukami Y, Michigishi T, Nonomura A, Yokoyama K, Noguchi M, Hashimoto T, Nakamura S, Ishizaki T. Autonomously functioning (hot) nodule of the thyroid gland. A clinical and histopathologic study of 17 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;101:29–35. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/101.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Russo D, Tumino S, Arturi F, Vigneri P, Grasso G, Pontecorvi A, Filetti S, Belfiore A. Detection of an activating mutation of the thyrotropin receptor in a case of an autonomously hyperfunctioning thyroid insular carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:735–738. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.3.3838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salvatori M, Rufini V, Corsello SM, Saletnich I, Rota CA, Barbarino A, Troncone L. Thyrotoxicosis due to ectopic retrotracheal adenoma treated with radioiodine. J Nucl Biol Med. 1993;37:69–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sundaraiya S, Dizdarevic S, Miles K, Quin J, Williams A, Wheatley T, Zammitt C. Unusual initial manifestation of metastatic follicular carcinoma of the thyroid with thyrotoxicosis diagnosed by technetium Tc 99m pertechnetate scan: Case report and review of literature. Endocr Pract. 2009;15:458–462. doi: 10.4158/EP08300.CRR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Damle NA, Bal C, Kumar P, Soundararajan R, Subbarao K. Incidental detection of hyperfunctioning thyroid cancer metastases in patients presenting with thyrotoxicosis. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:631–636. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.98028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gardner D, Ho SC. A rare cause of hyperthyroidism: Functioning thyroid metastases. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014;(pii) doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-206468. bcr2014206468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kunawudhi A, Promteangtrong C, Chotipanich C. A case report of hyperfunctioning metastatic thyroid cancer and rare I-131 avid liver metastasis. Indian J Nucl Med. 2016;31:210–214. doi: 10.4103/0972-3919.183616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abs R, Verhelst J, Schoofs E, De Somer E. Hyperfunctioning metastatic follicular thyroid carcinoma in Pendred's syndrome. Cancer. 1991;67:2191–2193. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910415)67:8<2191::AID-CNCR2820670831>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lorberboym M, Mechanick JI. Accelerated thyrotoxicosis induced by iodinated contrast media in metastatic differentiated thyroid carcinoma. J Nucl Med. 1996;37:1532–1535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoshimura Noh J, Mimura T, Kawano M, Hamada N, Ito K. Appearance of TSH receptor antibody and hyperthyroidism associated with metastatic thyroid cancer after total thyroidectomy. Endocr J. 1997;44:855–859. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.44.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guglielmi R, Pacella CM, Dottorini ME, Bizzarri GC, Todino V, Crescenzi A, Rinaldi R, Panunzi C, Rossi Z, Colombo L, Papini E. Severe thyrotoxicosis due to hyperfunctioning liver metastasis from follicular carcinoma: Treatment with (131)I and interstitial laser ablation. Thyroid. 1999;9:173–177. doi: 10.1089/thy.1999.9.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Basaria S, Salvatori R. Thyrotoxicosis due to metastatic papillary thyroid cancer in a patient with Graves' disease. J Endocrinol Invest. 2002;25:639–642. doi: 10.1007/BF03345090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Orsolon P, Giachetti M, Lupi A, Salgarello M, Malfatti V, Zanco P. Pre-therapy hyperfunctioning follicular thyroid carcinoma evaluation with I-131 whole-body scan and with F-18 FDG PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2008;33:882–886. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e31818bf1ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tan J, Zhang G, Xu W, Meng Z, Dong F, Zhang F, Jia Q, Liu X. Thyrotoxicosis due to functioning metastatic follicular thyroid carcinoma after twelve I-131 therapies. Clin Nucl Med. 2009;34:615–619. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3181b06b2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nishihara E, Amino N, Miyauchi A. Fractionated radioiodine therapy for hyperthyroidism caused by widespread metastatic follicular thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid. 2010;20:569–570. doi: 10.1089/thy.2009.0460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lim H, Devesa SS, Sosa JA, Check D, Kitahara CM. Trends in thyroid cancer incidence and mortality in the United States, 1974–2013. JAMA. 2017;317:1338–1348. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salih AM, Kakamad FH, Nihad H. Hyperfunctioning papillary thyroid carcinoma: A case report with literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;26:202–204. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pringle DR, Yin Z, Lee AA, Manchanda PK, Yu L, Parlow AF, Jarjoura D, La Perle KM, Kirschner LS. Thyroid-specific ablation of the Carney complex gene, PRKAR1A, results in hyperthyroidism and follicular thyroid cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2012;19:435–446. doi: 10.1530/ERC-11-0306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All the datasets generated and analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.