Abstract

Technology has the ability to foster social engagement, but a sizable divide exists between older and younger adults in the use of social communication technologies. The goal of the current study was to gain a better understanding of older adults’ perspectives on social communication technologies, including those with higher adoption rates such as email and those with lower adoption rates such as social networking sites (e.g., Facebook, Instagram). Semi-structured group interviews were conducted with either users or non-users of social networking sites to gain insight into issues of adoption and non-adoption of social communication technologies. The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology model (UTAUT) was adapted and used to categorize the interview content. We found support for a benefit-driven account of social communication technology acceptance and usage, with participants most frequently discussing the degree social communication technologies would or would not help them attain gains in social connectedness, entertainment, and/or information sharing. However, the UTAUT was not sufficient in fully capturing the group-interview content, with additional categories being necessary. For instance, trust in social networking sites (privacy and security concerns) was frequently discussed by both users and non-users. The current results broaden theories of technology acceptance by identifying facilitators and barriers to technology use in the older adult population.

Keywords: social networking sites, social communication technology, older adults, email, technology acceptance, UTAUT

Maintaining a socially engaged lifestyle exerts a positive impact on health and well-being (see Thoits, 2011). Technology can act as a facilitator of social engagement, especially for older adults who may be experiencing barriers to maintaining a socially active lifestyle (e.g., due to reduced mobility, lack of transportation). The past few decades have seen the proliferation of various social communication technologies, including email, social networking sites (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, Instagram), and video conferencing software (e.g., Skype). Although the adoption of social communication technologies has been increasing among older adults in recent years, an intergenerational digital divide still exists (Anderson, 2015; Friemel, 2016). With regard to social networking sites (e.g., Facebook, Twitter), only 35% of older adults (aged 65 and above) report using these social communication technologies, in comparison to nearly 90% of younger adults (Perrin, 2015). If older adults are to benefit from the social engagement enabled by these technologies, we need to understand the factors that contribute to their adoption and use.

Social networking sites in particular have rapidly increased in adoption rates over the past decade, with sites such as Facebook and Twitter becoming an increasingly integrated form of communication within individuals’ social lives. Though varied in their features and communication goals, social networking sites are defined as “web-based services that allow individuals to (1) construct a public or semi-public profile within a bounded system, (2) articulate a list of other users with whom they share a connection, and (3) view and traverse their list of connections and those made by others within the system” (Ellison, 2007, p. 211). Although these technologies are becoming an increasingly common form of social communication among all age groups (Perrin, 2015), prior research has primarily focused on the adoption and use of social networking sites in younger adult samples (e.g., Ellison, Steinfield, & Lampe, 2007). A gap in knowledge exists in understanding the use of these technologies by older adults.

Benefits of Social Communication Technologies for Older Adults

Many older adults face challenges that can negatively impact their levels of social engagement. These include, but are not limited to, physical challenges such as disease and reductions in mobility (e.g., Blagojevic, Jinks, Jeffery, & Jordan, 2010; Bohannon, 1997; Fulop et al., 2010), cognitive challenges such as memory decline (Fisk et al., 2009), as well as financial challenges such as living on a fixed income (e.g., Social Security, pensions). All of these challenges can make maintaining interpersonal social relations and participating in social activities more difficult compared to individuals not experiencing these challenges. Technology is a tool that holds the potential to reduce social engagement barriers for older adults (Bixter, Blocker, & Rogers, 2018; Quan-Haase, Mo, & Wellman, 2017). Social communication technologies allow older adults to communicate with family and friends regardless of the geographical distance that may exist between them and to participate in other social activities, such as sharing information on a common interest. These technologies also provide the ability for communication and other social information to be documented and stored for the individual to subsequently access and consult. This functionality has the potential to compensate for cognitive challenges such as memory-related impairments that can affect an individual’s ability to retain complex interpersonal information and relationships. Finally, social communication technologies are typically free to join, providing a no-cost tool for individuals wishing to interact with others in their social network more frequently.

Most of the research that investigated the effects of social communication technology use has focused on younger adults (e.g., Ellison et al., 2007; Jung, Pawlowski, & Kim, 2017; Subrahmanyam, Reich, Waechter, & Espinoza, 2008). Yet in the few studies that did include older adults, benefits of social communication technology use emerged. In a sample of adults (19-76 years old), Facebook non-users reported higher levels of loneliness compared to users of the social networking site (Sheldon, 2012). Furthermore, a qualitative study that consisted of an internet-based social networking intervention found that the use of a social networking site resulted in older adults reporting less loneliness (Ballantyne, Trenwith, Zubrinich, & Corlis, 2010. Chopik (2016) also found that higher use of social communication technologies (e.g., email, social networking sites, tele-video, instant messaging, smartphones) was related to a variety of benefits in older adults, including better self-rated health, fewer chronic illnesses, and higher subjective well-being. Each of these relationships between social communication technology use and better health outcomes was mediated by the reduction in loneliness associated with social communication technology use.

Use of social networking sites is associated with feelings of social well-being in older adults (Yu, Mccammon, Ellison, & Langa, 2016), a sense of social connectedness (Sinclair & Grieve, 2017), reduces the negative impact functional disability has on well-being (van Ingen, Rains, & Wright, 2017), and relieves stress (for a review, see Leist, 2013). Cognitive benefits have emerged as well. Following the completion of an 8-week Facebook training intervention group, older adults exhibited higher levels of executive functioning compared to both a no-intervention control group and an active control group (an online diary group; Myhre, Mehl, & Glisky 2017). Given research findings of the psychological and well-being benefits that result from older adults utilizing social communication technologies, it is critical to determine the factors that contribute to older adults’ decisions to adopt these technologies.

Predictors of Social Communication Technology Use in Older Adults

Models of technology acceptance provide insight into individual differences in the adoption of technology, including characteristics such as age. Perhaps the most comprehensive is the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology model (UTAUT; Venkatesh, Morris, Davis, & Davis, 2003). The UTAUT was designed to integrate and update aspects of prior models of technology acceptance and it predicts technology adoption better than other models (e.g., Ling, Downe, Ahmad, & Lai, 2011; Venkatesh et al., 2003). The UTAUT integrates elements from prior well-known models of technology acceptance and consists of the following four core constructs: (1) whether using a technology is believed to lead to gains in performance (performance expectancy); (2) the degree a technology is easy to use (effort expectancy); (3) whether an individual believes important others think the individual should be using the technology (social influence); and (4) the extent an individual believes an organizational or technical infrastructure exists to aid in using the technology (facilitating conditions). The UTAUT has been used to account for the acceptance or use of a variety of technologies, including internet banking (Martins, Oliveira, & Popovič, 2014), electronic medical records by healthcare professionals (Wills, El-Gayar, & Bennett, 2008), and digital learning environments by teachers (Pynoo, Devolder, Tondeur, van Braak, Duyck, & Duyck, 2011).

Although the UTAUT has not been directly applied to understand the use of social communication technologies in older adults, prior research has used other technology acceptance frameworks. For example, Braun (2013) explored the factors that predict the intention to use social networking sites among older adults utilizing the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM; Davis, 1989). According to this framework, the intention to use a technology can be predicted by the following two core constructs: perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. Perceived usefulness refers to the degree an individual believes using a technology would enhance his or her performance. Perceived ease of use refers to the degree an individual believes using a technology would be relatively free of effort. Braun (2013) had participants complete a questionnaire that measured the constructs of TAM as they applied to social networking sites. These scores were then used to quantitatively predict intention to use social networking sites. Perceived usefulness was the strongest unique predictor among a sample of older adults (for similar findings, see Lüders & Brandtzæg, 2017). Perceived ease of use and social pressures to use social networking sites did not independently predict intention to use. Given that intention to adopt predicts adoption and use, these findings suggests that a critical factor in social communication technology adoption is the extent that an older adult perceives the technology to provide a particular benefit or utility to his or her life (for other examples of related benefit-driven effects on technology adoption in older adults, see Liu, 2015, 2016; Maier, Laumer, & Eckhardt, 2011; Melenhorst, Rogers, & Bouwhuis, 2006; Mitzner et al., 2010).

The Braun (2013) study provided initial insights into older adults’ adoption of social networking sites, but it was based on the more limited TAM that does not include all of the constructs in the UTAUT. Perceived usefulness in the TAM does closely map onto the performance expectancy construct of the UTAUT and perceived ease of use in the TAM is closely related to the effort expectancy construct of the UTAUT. Yet, to obtain a more comprehensive assessment of the facilitators and barriers to adoption of social networking technologies, the full UTAUT model might be more informative (relative to the TAM). However, there are reasons to expect that even UTAUT is insufficient in accounting for all of the major contributions to the adoption and use of social communication technologies by older adults. For example, social communication technologies often involve the sharing of personal information (e.g., photos, status updates, locations). Privacy and security concerns affect older adults’ opinions of technologies that involve the sharing or collection of personal information (Chakraborty, Vishik, & Rao, 2013; Melenhorst, Fisk, Mynatt, & Rogers, 2004). This is often observed in technologies that involve the sharing of medical information, with various extensions of the UTAUT being necessary to capture feelings of trust older adults hold towards the particular technology (Cimperman, Brenčič, and Trkman, 2016; Hoque & Sorwar, 2017). Furthermore, other factors influence older adults’ acceptance and use of computer-related technologies, such as self-efficacy and anxiety (Czaja et al., 2006). Though some of these factors were not relevant for the domains originally tested by UTAUT (Venkatesh et al., 2003), extensions of the model are often necessary to accommodate both the technological domain (e.g., social communication technologies) and the profile of the targeted group (e.g., older adults) in fully capturing the factors contributing to technology acceptance and use.

Overview of Current Study

We designed the current study to gain a deeper understanding of the potential facilitators and barriers to the adoption of social communication technologies by older adults. We examined perceptions about a more widely-adopted technology (email), and technologies that are less widely-adopted by older adults compared to younger age groups (social networking sites). We conducted semi-structured group interviews that directly probed the opinions and perspectives of older adults on these social communication technologies. The group interviews allowed us to gain rich details about older adults’ attitudes related to technology adoption factors. One particular goal was to gain a better understanding of older adults’ perceptions of less widely-adopted social communication technologies, such as social networking sites. To understand issues of adoption and non-adoption of social networking sites the interviews included both users and non-users of these sites, though all participants were users of the internet and email. It was critical that certain factors were controlled for in participants, such as the motivation or ability to use either the internet or electronic communication more generally. Because all participants demonstrated an ability to use a social communication technology to interact socially with others (i.e., email), we were better able to isolate the factors that contribute to the use or non-use of social networking sites in particular.

The current study utilized the UTAUT (Venkatesh et al., 2003) framework to account for the factors that emerged from the group-interview data. In addition, we looked for themes raised by the older adults that were not included in UTAUT. Thus, insight from these group interviews not only provide a qualitative evaluation of the UTAUT model in the domain of social communication technologies, but also can aid the design and further modification of these technologies to increase the acceptance rates in the older adult population.

Method

Participants

A total of 28 community-dwelling older adults from the Atlanta metropolitan area were recruited for group interviews. Prescreening ensured that all participants were active users of the internet and email, and were either active users or non-users of social networking sites. To be classified as a user of a social networking site, the individual had to have a profile on a popular social networking site (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, or LinkedIn), and had to have accessed the site at least once during the previous month. There were six interview groups, with half of the groups consisting of users of social networking sites and the other half consisting of non-users. Groups ranged in size from four to six individuals, producing a total of 12 participants who were users of social networking sites and 16 participants who were non-users.

Sample size was determined by the concept of data saturation (Fusch & Ness, 2015; Trotter, 2012) and by prior qualitative research. Prior guidelines for qualitative approaches include sample sizes of 20 to 30 participants (Creswell, 1998; Dworkin, 2012). Moreover, in a review of 561 studies that used qualitative approaches (Mason, 2010), the median sample size was calculated as 28. Hence, 28 participants were decided to be an acceptable sample size to achieve data saturation.

The mean age of the sample was 72.44 (SD = 4.32; range: 61 to 78) and 57% of the sample was female. The racial/ethnic breakdown of the sample was as follows: 71% non-Hispanic White/Caucasian, 14% Black/African-American, 11% Hispanic, and 4% no reported primary racial group. Participants were compensated $30 for their involvement in the study. The sample was well educated (89% had at least some college), varied in marital status (18% single, 36% married, 29% divorced, and 18% widowed), and lived independently (79% lived in their own home/apartment/condominium). On average, participants reported their health as good, very good in relation to other people their age, and that health problems seldomly stood in the way of doing things they wanted to do.

Materials

Interview Script

The interviews consisted of three parts. Part one focused on email. Part two focused on social networking sites, including Facebook, Twitter, online health support/forums, LinkedIn, Instagram, and Pinterest. For each of the above listed technologies or sites, groups were asked to “Think about all aspects of [the technology] and everything you have heard about it.” Then, participants were asked “Have or would you use it?”, “What do or would you use it for?”, “What do you like about it?”, “What do you dislike about it?”, and whether they had “Any other comments or ideas about it?”.

Part three of the group interview consisted of questions relating to social networking sites more generally. Participants were asked to discuss: “What are the features that you look for in a social networking website?”, “What are some features of social networking websites that you find are unnecessary?”, “Do you ever find that you are frustrated or confused or would be frustrated or confused when using certain social networking websites?”, “What causes you to feel this way?”, “Do you feel that using social networking websites is/would be difficult?”, “Did somebody help you or would someone be able to help you in using a social networking website?”, and “Have you helped somebody else in using a social networking website?”.

Questionnaires

Prior to the group interview, participants completed a series of questionnaires. The questionnaires were designed to gather background information about the participants as well as about their experiences with various technologies. These measures included:

Demographics and Health Questionnaire (Czaja et al., 2006).

Participants self-reported demographic information (e.g., gender, age, education, marital status, race/ethnicity, type of housing) and their subjective health status.

Technology Experience Profile (Barg-Walkow, Mitzner, & Rogers, 2014).

Participants self-reported how often they used various technologies over the previous 12 months. These included communications, computer, everyday health, recreational, and transportation technologies. Participants rated whether they used a technology on a four-point scale from “Not Used” to “Used Frequently,” with an additional option of “Not Sure what the technology is.” The questionnaire then contained items asking about participants’ use of the internet.

Email and Social Networking Site Questionnaire.

A questionnaire was developed to measure participants’ use or non-use of email and social networking sites. Participants self-reported whether they used email or various social networking sites, as well as the frequency of use. Participants were then asked to state whether various reasons a person would use or not use email or social networking sites applied to them. For example, participants were asked about privacy and security concerns, such as “I am concerned about privacy on social networking websites” and “I am concerned about security on social networking websites.” Participants rated whether they had used or not used email or social networking sites for these reasons on the following scale: (1) Yes, (2) No, (3) Not sure, and (4) N/A.

Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Ease of Use Questionnaire.

A questionnaire modified from Davis (1989) was developed to measure both perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use towards social networking sites. The questionnaire consisted of 12 items. Six of the items measured perceived usefulness, with an example item being “I would find a social networking website useful in my daily life.” The remaining six items measured perceived ease of use, with an example item being “I would find a social networking website easy to use.” Participants made responses on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = Extremely Unlikely, 7 = Extremely Likely).

Participants completed the Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Ease of Use Questionnaire both before and after the group interviews. Because the current paper does not focus on (pre-post interview) changes in perceived usefulness or perceived ease of use towards social networking sites in response to the group interview, these data are not presented.

Procedure

Participants provided informed consent upon arriving to the laboratory. They then completed the following questionnaires: Demographics and Health, Technology Experience, Email and Social Networking Sites, and Perceived Usefulness and Ease of Use.

Prior to the group interviews, participants were provided with a sheet of paper that contained brief descriptions of all the social communication technologies asked about during the interviews. Each member of the group then introduced themselves to the rest of the group and shared their favorite hobby or activity as an ice breaker before discussing social communication technologies.

The semi-structured interviews were directed by one of two trained interviewers. Following part two of the group interview, participants were given a 10-minute break. Following the group interviews, participants once again completed the Perceived Usefulness and Ease of Use Questionnaire. Participants were then thanked, debriefed, and compensated for their time. The entire procedure took approximately three hours to complete.

Results

Overview of Coding and Analysis of Group-Interview Data

The audio recordings of the six group interviews were professionally transcribed verbatim with personal information omitted. Transcripts were then segmented into units of analysis by two coders. A segment was defined as a speaker turn in the group discussion. However, if one group member’s discussion content was briefly interrupted by either the interviewer or another group member, the discussion content before and after the interruption was combined into a single segment.

Segments were then analyzed based on the coding scheme in Table 1. The coding scheme included four constructs from the UTAUT model (Venkatesh et al., 2003) that influence the use of technology: performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, and facilitating conditions. Performance expectancy was divided into two coding categories, dependent on whether the technology (email or social networking sites) was helpful or not helpful in attaining gains in terms of social connectedness, entertainment, and/or information sharing. Moreover, an impeding conditions category was added to the current coding scheme. Additional categories were added to the coding scheme based on their predicted relationships with the adoption and use of technology. These included two categories relating to trust in the technology (privacy and security), self-efficacy, anxiety, and two categories relating to affect towards the technology (positive and negative affect). Two additional categories needed to be added to the coding scheme to fully capture the content of the group interviews: perception of content and current knowledge/skills. The former refers to the perception an individual has of the content included in email or a social networking site as being uninteresting, irrelevant, or inappropriate. Current knowledge/skills refer to knowledge or skills that affect use and/or perception of email or a social networking site. The current knowledge/skills category differs from the self-efficacy category in that the latter refers to an individual’s belief in his or her capacity to produce expected results when interacting with email or a social networking site, whereas the former refers to a current level of knowledge or skills that stems from familiarity/unfamiliarity with the technology.

Table 1.

Coding scheme used for organizing the qualitative data

| Categories | Definition | Adapted Definition Relevant to Social Communication Technologies |

|---|---|---|

| From UTAUT | ||

| Performance Expectancy | The degree to which an individual believes that using the system will help him or her to attain gains in job performance (Venkatesh et al., 2003) | The degree to which an individual believes that using the social communication technology will or will not help him or her attain gains in terms of social connectedness, entertainment, and/or information sharing |

| Effort Expectancy | The degree of ease associated with the use of the system (Venkatesh et al., 2003) | The degree of ease associated with the use of the social communication technology for the purposes of social connectedness, entertainment, and/or information sharing |

| Social Influence | The degree to which an individual perceives that important others believe he or she should use the new system (Venkatesh et al., 2003) | The degree to which an individual perceives explicit or implicit social pressure and/or encouragement to use or not use the social communication technology |

| Facilitating and Impeding Conditions | The degree to which an individual believes that an organizational and technical infrastructure exists to support use of the system (Venkatesh et al., 2003) | The degree to which an individual believes that an adequate foundation (e.g., friends, family, tech support) and appropriate technical resources exist to support the use of the social communication technology |

| Additional | ||

| Trust - Privacy | The unauthorized collection, disclosure, or other use of personal information as a direct result of electronic commerce transactions (Wang, Lee, & Wang, 1998) | The degree to which a social communication technology ensures that a user (self or other) has control over the public exposure of their information and content |

| Trust - Security | Protection against a circumstance, condition, or event with the potential to cause economic hardship to data or network resources in the form of destruction, disclosure, modification of data, denial of service, and/or fraud, waste, and abuse (Kalakota & Whinston, 1996) | The degree to which a social communication technology ensures that the user’s personal information and data are protected from the possible malicious effects due to phishing, fraud, and/or cyber harassment |

| Perception of Content | Information perceived as too much, too little, uninteresting, irrelevant (Prakash, 2016) | The perception of the content of a social communication technology as uninteresting, irrelevant, and/or inappropriate |

| Current Knowledge/Skills | Knowledge and skill level that affects use and/or perception of the technology (Prakash, 2016) | Current knowledge or skill level that affects use and/or perception of a social communication technology |

| Self-Efficacy | The degree to which an individual believes in his or her capacity to execute behaviors necessary to produce specific performance attainments (Bandura, 1977, 1997) | The degree to which an individual believes in his or her capacity to produce expected results when interacting with a social communication technology |

| Anxiety | The degree to which an individual’s exposure to a situation induces feelings of tension, worried thoughts and physical changes like increased blood pressure (Kowalski, 2000) | The degree to which an individual’s exposure to and use of a social communication technology induces feelings of tension, worried thoughts and physical changes like increased blood pressure |

| Affect (Positive and Negative) | Positive feelings (e.g., happiness, elation, enjoyment) or negative feelings (e.g., sadness, frustration, boredom, anger, hate, disgust) associated with email use (Prakash, 2016) | Positive feelings (e.g., happiness, elation, enjoyment) or negative feelings (e.g., sadness, frustration, boredom, anger, hate, disgust) associated with social communication technology |

Notes. UTAUT = Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology model (Venkatesh et al., 2003).

To establish inter-rater reliability, two coders first independently coded two of the group interviews, then discussed discrepancies and modified the coding scheme as needed to fully capture the themes that emerged in the data. The two coders then independently coded all six group interviews. A reliability metric was determined based on the percent of segments for each group interview that the two coders agreed upon. Categories were not mutually exclusive, so a segment could contain instances from multiple categories. For a segment to be agreed upon by the two coders, there needed to be complete similarity in the categories the two coders marked as being contained in the segment. This represents a conservative test of reliability because partial agreement was never awarded to a segment. The percent agreement for a group interview was determined by calculating the percent of segments for that group interview that the two coders fully agreed upon (for a similar method, see Rogers, Meyer, Walker, & Fisk, 1998; Stewart & Shamdasani, 1990). Although there is no definitive standard in the literature, multiple experts have suggested 80% agreement as a reasonable level of reliability (Bradley, Curry, & Devers, 2007; Miles & Huberman, 1994). The mean percent agreement across all six group interviews was 86% (range: 80% to 91%). All discrepancies were subsequently discussed and resolved by the two coders.

Overview of Group-Interview Results

Email.

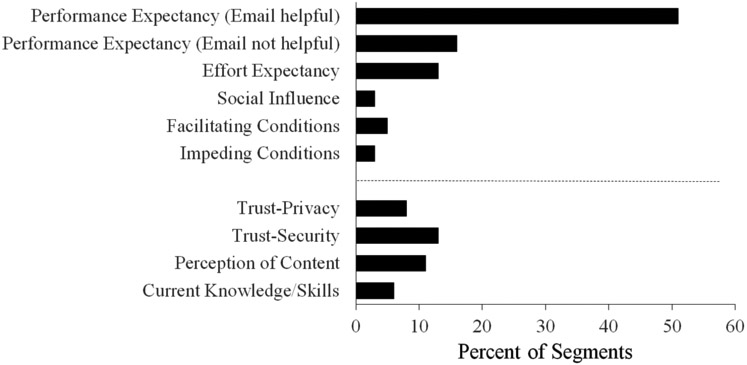

Participants were all frequent users of email. As a result, the analyses and frequency scores pertaining to email derive from the discussion content of all six group interviews. There were 126 segments from the six group interviews that contained discussion content regarding email. A frequency score for an individual category in the coding scheme was calculated as the percent of relevant segments that contained an instance of that particular category (see Figure 1). This meant that the frequency score could range from 0% to 100% for each category, with 100% meaning that an instance of a category in the coding scheme occurred in every relevant segment. Table 2 includes recurring themes that emerged from the discussion content captured by the categories in the current coding scheme, as well as example quotes that provide textual support for each category and theme.

Figure 1.

The frequency that each category occurred in the segments relating to email. Categories were not mutually exclusive, so a segment could contain instances from multiple categories (i.e., each category could have a frequency ranging from 0% to 100%). Categories derived from the UTAUT model are presented above the dashed line; additional categories are presented below the dashed line.

Table 2.

Recurring themes that emerged from the group-discussion content regarding Email

| Categories | Themes | Example Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| From UTAUT | ||

| Performance Expectancy (Email helpful) | time-effectiveness |

“I like the instantaneous response factor. I mean, I can stay in touch with someone even if they're too busy to respond. I just like the fact that I’m not always intruding on their time because eventually they will respond by email” “It’s faster. That’s the thing, it’s a lot faster than waiting for a paper in the mail. That’s a plus of it.” “I particularly like the fact that you can contact your doctor and get a response back within 48 hours. It’s usually a very short time.” |

| goal-effectiveness | “I love it for keeping in touch with my tennis team. If we’re rained out, we need a fourth, something happens …the courts are wet. That’s very useful.” | |

| geographic –irrelevance | “I use my email to keep in touch with my brothers and sisters because we all live in a different state. My daughter travels for [a] living so I use it to communicate with her and to catch up with old friends that I haven’t talked to for a long time.” | |

| information-documentation | “A lot of stores now, instead of or in addition to a paper receipt, will ask if you want an email. I keep all the emails and have a folder of receipts in my email which prevents me from throwing it in the trash and wanting it later.” | |

| Performance Expectancy (Email not helpful) | technology-related issues | “And sometimes, I will want to forward an email to somebody but they don’t get it because their filters are so strict” |

| goal-ineffectiveness | “I also prefer the phone. In the hierarchy of communication, face-to-face is the best. You always get more accomplished face-to-face. Second level is telephone. You can hear tones. You can get more communication from phones.” | |

| Effort Expectancy | technology-related | “I’ve noticed that it has been a lot easier to unsubscribe to some of the mail that you get. Before, it really was a pain in the butt but now I find it pretty simple to unsubscribe.” |

| goal-related | “It just makes everything so much easier. It’s quicker, and… makes everything easier to get to a lot of people.” | |

| Social Influence | “I have no grandchildren, so that has not forced me to stay and keep in touch because I know I have a lot of contemporaries that [their grandchildren] force them into it.” | |

| Facilitating and Impeding Conditions | “Well, don’t ever open anything on Gmail or whatever that is an ad. …I use Norton, and it makes better judgments on the sites…And you never go to an ad. I never go to an ad. Just go to things that are Norton approved.” | |

| Additional | ||

| Trust-Privacy | “The worst part about spam is you go someplace, they ask for your email address, you do it, you give it to them, but then they have all their affiliates, and they pass your email address to their affiliates and then you’ve got tons of spam.” | |

| Trust-Security | “Well, worst thing now is the security because that if you open an email from somebody that you don’t know there’s [a] 75% chance there’s some kind of virus associated with it…and it’ll completely take control of your computer.” | |

| Perception of Content | undesired or unsolicited content | “One of the things I don’t like about [email] is spam. You get a lot of stuff on there that you don’t really want. And then, of course some of it is my own creation, I’ll say well I’m interested in something so then I get a thousand emails on life fishing or sport, sports-related things.” |

| Current Knowledge/Skills | “In the junk department in email, on my computer, I haven’t figured out a way to delete. Say you’ve got 500 of those or a 1000 of those, and there should be an easy way to just…delete them all.” |

Notes. UTAUT = Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology model (Venkatesh et al., 2003).

Social networking sites.

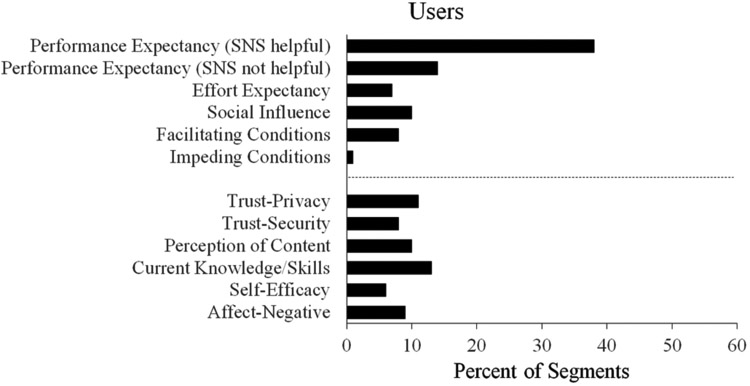

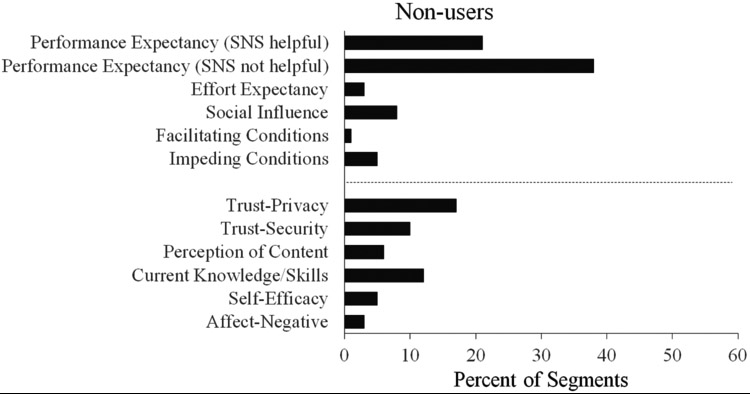

Participants comprised two groups: users and non-users. This afforded the ability to assess whether the modified UTAUT coding scheme differentially captured the discussion content of users and non-users of social networking sites. The analysis of group discussion content pertaining to social networking sites proceeded in a similar fashion as the email analyses described above. Relevant segments contained discussion content regarding social networking sites. This produced 151 and 172 segments for the users and non-users, respectively. Frequency scores for categories in the coding scheme were calculated as the percent of relevant segments that contained an instance of a particular category (see Figure 2). As a result, frequency scores could range from 0% to 100% for each category, with 100% meaning that an instance of a category in the coding scheme occurred in every relevant segment. Table 3 includes recurring themes that emerged from the discussion content captured by the categories in the current coding scheme, as well as example quotes that provide textual support for each category and theme.

Figure 2.

The frequency that each category occurred in the segments relating to social networking sites for both users (Figure 2A) and non-users (Figure 2B). Categories were not mutually exclusive, so a segment could contain instances from multiple categories (i.e., each category could have a frequency ranging from 0% to 100%). Categories derived from the UTAUT model are presented above the dashed line; additional categories are presented below the dashed line. *SNS = social networking sites.

Table 3.

Recurring themes that emerged from the group-discussion content regarding Social Networking Sites

| Categories | Themes | Example Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| From UTAUT | ||

| Performance Expectancy (SNS helpful) | information-sharing | “I mainly use it [Twitter] in the early morning. When I get up in the morning, I look and see the newspeeds…It just gives you a quick hit about other places to go to get information if you see something that looks interesting.” (User) |

| connection-forming | “Online health forums. I did mention one that’s on Facebook…it’s called hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and that basically started online. My stepdaughter told me about this some years ago, and this particular online forum may be the reason I’m standing here talking to you today. Because I got in touch with the people with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.” (User) | |

| connection-strengthening | “I also found that my next-door neighbor uses Twitter. She just had a kid, two kids actually, and I got to know her better through Twitter than just going over and saying hello.” (User) | |

| Performance Expectancy (SNS not helpful) | time-ineffectiveness | “I don’t need to know all that information that’s thrown in there…I think the older you get, you kind of prioritize your hobbies, your things, what you have time for, what you don’t. [Social networking] is definitely not in my scope.” (Non-user) |

| goal-incongruity | “But I don’t use Facebook for a couple of reasons…I don’t want to be that connected. I mean, I get email and the telephone and texting. And that’s enough.” (Non-user) | |

| Effort Expectancy | technology-related | “Trying to know how the darn thing works. Uploading pictures is one thing which you can figure out after a while but Facebook has gotten so complex.” (User) |

| Social Influence | work-related | “I use LinkedIn every day because all my hiring companies and potential clients are on LinkedIn. So, I’m on that regularly, and I use that several hours a day.” (User) |

| personal-related | “My sister was the one that suggested I go on. She said that your relatives are on there all the time. And she was right, they are.” (User) | |

| Facilitating and Impeding Conditions | “Well, in my community too, they offer instructions for the residents, and we have two residents who are very computer savvy so they help often.” (User) | |

| Additional | ||

| Trust-Privacy | “The bad thing about Facebook is if you read, or post something…now not only do your friends, but their friends, their friends, their friends, and their friends [see it]. And that is why…you have to be so careful what you say out there because there’s no telling where it’s going in the universe.” (User) | |

| Trust-Security | “A lot of these criminals are very sophisticated and very smart, and they know how to use these social networks to find out information about you.” (User) | |

| Perception of Content | undesired or unsolicited content | “I only want to have less spam. It’s [the] only one problem.” (User) |

| inappropriate content | “And sometimes in the case of young people, it’s the language…It is really inappropriate language.” (User) | |

| trivial content | “There’s too much interchange of …trivialities of life going on there with a lot of these social networking [sites]. And… I’m not saying it’s not a step in the right direction- Too progressing. But I just think a lot of it’s unnecessary.” (Non-user) | |

| Current Knowledge/Skills | “I don’t understand what you could do with it. I’ve never had that education in it. If I understood it more, and how I could productively use it, if that was possible, I might be interested.” (Non-user) | |

| Self-efficacy | “Twitter…I think it gets too complicated for my brain.” (User) | |

| Negative Affect | technology-related | “However, you cannot eliminate parts of things. I mean, if I have to eliminate that total contact to get rid of all of those other people that are linked to it, and I find that annoying.” (User) |

| content-related | “I just found it irritating, you know, because people that post, post, post, post, post. So, you know, I said that before so I end up blocking them. It’s just, it’s irritating to me.” (User) |

Notes. UTAUT = Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology model (Venkatesh et al., 2003). SNS = social networking sites. User = user of a social networking site. Non-user = non-user of a social networking site.

UTAUT Categories

We first report results for the four core constructs of UTAUT. These include performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, and facilitating and impeding conditions. For each construct, we present the results for discussion dealing with email and social networking sites separately. For results regarding social networking sites, we also report any thematic differences that emerged between the group interviews of users vs. non-users.

Performance Expectancy

Email.

The group-interview discussions often focused on the usefulness participants saw in email. Specifically, the performance expectancy category in which participants mentioned how email helps them attain gains in terms of social connectedness, entertainment, and/or information sharing occurred in over half of the relevant segments relating to email. This discussion largely consisted of the following four themes concerning email: time-effectiveness, goal-effectiveness, geographic-irrelevance, and information-documentation.

For the time-effectiveness theme, participants repeatedly discussed how communicating through email was more effective in saving time compared to other forms of communication. Goal-effectiveness refers to instances where participants believed email was better able to achieve goals of social communication compared to other forms of communication. These goals could range from coordinating an event amongst multiple people to achieving clarity during communication. Geographic-irrelevance refers to instances where participants mentioned how email helped them remain in communication with relatives and friends regardless of the geographic distance that separated them. Finally, email allows individuals to send and store information electronically. The information-documentation theme consisted of instances where participants mentioned how this aspect of email was useful for their particular needs.

Though participants discussed more frequently how email is helpful in attaining gains in terms of social connectedness, entertainment, and/or information sharing, there were still many instances where participants mentioned that email was not helpful in attaining these gains. This group-interview discussion largely consisted of the following two themes: technology-related issues and goal-ineffectiveness.

Technology-related issues refer to aspects of the technology itself that may prevent social communication from occurring. The issue most often discussed was the fact that recipients of emails do not always receive them. Goal-ineffectiveness refers to instances where participants believe that other forms of communication were better able to achieve goals of social communication compared to email. For instance, a goal may be the need to communicate with others to accomplish a specific task at hand, or something more general such as communicating with others without disrespecting the other party. In sum, whereas some participants mentioned email being useful for less personal instances of communication (e.g., confirmation of a plane ticket), the goal of maintaining personal relationships (e.g., with family and friends) was believed by these participants to be better achieved through forms of communication other than email.

Social networking sites.

Similar to email, the group-interview discussions often focused on the perceived usefulness of social networking sites. However, users and non-users differed in that the former were more likely to mention how social networking sites would help them in attaining gains in terms of social connectedness, entertainment, and/or information sharing. Specifically, for the users, the following three themes emerged from their group interviews: information-sharing, connection-forming, and connection-strengthening. For the first theme, participants often mentioned that a main reason they used social networking sites was because it helps them better gather and share information. The connection-forming theme refers to instances where users mentioned that social networking sites had led them to form new connections in their social network that otherwise would not exist. These connections could be based on a shared topic of interest (e.g., a specific health-related issue) or connections based on similar skills or other work-related qualities. Finally, the connection-strengthening theme refers to instances where users mentioned that social networking sites had strengthened already existing connections in their social networks.

In contrast to users, non-users were more likely to mention how social networking sites would not be helpful in attaining gains in terms of social connectedness, entertainment, and/or information sharing. For the non-users, the following two themes emerged from their group interviews relating to social networking sites: time-ineffectiveness and goal-incongruity. For the first theme, participants often mentioned that using social networking sites would be a waste of time and that other activities would be more beneficial in terms of entertainment and information-gathering. The goal-incongruity theme refers to instances where non-users mentioned that the use of social networking sites was incongruous with their current goals. For example, individuals may not desire additional connections in their social network with their current goal being to maintain already existing connections that do not require social networking sites.

Effort Expectancy

Email.

Two themes were identified from the group-discussion content that were captured by the effort expectancy category: technology-related and goal-related. The former refers to the ease of use of email itself or a particular function contained within email. That is, the degree that individuals found email easy to use or that carrying out a function within email was an easy process to accomplish. For instance, one participant mentioned that even though sometimes desired emails are diverted to a spam folder, it was not a problem because “you can easily bring them over” to your inbox folder. In other instances, it was mentioned that the ease of carrying out a function can change over time, either due to increased familiarity with the technology or because the technology itself has been updated. Goal-related effort expectancy refers to the fact that individuals stated that it was easier to accomplish a certain goal using email compared to other forms of communication. An example would be that email was an easier communication method to distribute information to a lot of people. Moreover, coordinating events can be more easily handled through email or a subcomponent of email (such as a shared calendar) than a series of telephone calls.

Social networking sites.

The group-discussion content relating to social networking sites mainly consisted of technology-related as opposed to goal-related effort expectancy. That is, whereas email was often described as being easier to accomplish particular goals (e.g., coordinating events) than other forms of communication, the discussion content relating to social networking sites often focused on the ease or complexity associated with the technology itself. This discussion content occurred at a higher frequency for users than non-users, with the former encountering difficulties through their use of a specific site. Furthermore, in contrast to email, where certain functions were described as becoming easier to execute over time, certain functions of social networking sites, or the site itself (e.g., Facebook), were often described as becoming increasingly more complex over time.

Social Influence

Email.

Though social influence was not mentioned at a high enough frequency in the group interviews to identify recurring themes, participants did mention a few instances where the degree of their use of email was influenced by other people. Participants who were still employed mentioned having to use email for work, with email becoming a preferred method of communication for many segments of participants’ work-related social network. A lack of social influence was sometimes stated as a reason for which email was either not adopted or not used in a frequent manner. For instance, one participant mentioned that they were not as frequent of an email user as some of their contemporaries because they did not have grandchildren to exert pressure on them to use email as a method of communication.

Social networking sites.

The nature of the discussion content captured by the social influence category for social networking sites was similar to the influences mentioned for email. That is, for participants who were still employed, work-related social influence had an impact on their use of a particular social networking site (usually LinkedIn). For personal-related matters, the extent that relatives or close friends were using a social networking site had an influence on individuals’ adoption or continued use of the site. Sometimes this influence was explicit in that a relative or close friend directly suggested that a participant would benefit from using a specific site.

Social influence also contributed to some participants’ non-use of a social networking site. For example, one non-user stated that the reason they do not use Twitter was because “a friend whose opinion I respect highly” had spoken unfavorably of the site. Furthermore, participants who were users of one social networking site but not another mentioned a lack of social influence or pressure towards the non-used site. One participant mentioned that “I don’t know anybody my age who uses it [Instagram] at all.”

Facilitating and Impeding Conditions

Email.

Participants did mention a few instances where their use of email was aided by others. Facilitating conditions mainly consisted of help participants had received in modifying their email system to avoid undesirable content (e.g., spam and ads). Spam and ad content in email was frequently discussed negatively in the group interviews (see the perception of content category below). Assistance to manage such content from multiple sources, including family members and technical resources (e.g., an antivirus program), was noted as facilitating email use.

Social networking sites.

The category of facilitating conditions was mentioned at a higher frequency by the users compared to the non-users. Although the resource that was most often mentioned as a facilitating condition by users was a relative (usually their children), participants did mention a few cases where non-relatives helped them in either the adoption of a social networking site or aiding in the continued use of a site. Impeding conditions mainly consisted of participants believing that there was a lack of resources (usually technical resources) available for them. For instance, one current non-user of Facebook who had created a profile a few years back was quickly dismayed that a large number of people the participant did not know appeared on their Facebook page. The participant contacted Facebook to inquire about the issue but never received a response. The participant then mentioned that “in less than a week I closed out the account and I’ve never wanted one since.” Another non-user mentioned that they had never come across a book that described how to use social networking sites.

Additional Categories

The UTAUT categories were not sufficient to classify all of the group-discussion content for either email or social networking sites, necessitating additional categories. Next, we discuss the content from the additional categories that occurred with a frequency above 5% of the relevant segments for email or social networking sites. These categories included trust (privacy and security), perception of content, current knowledge/skills, self-efficacy, and negative affect. Similar to above, we present the results for discussion dealing with email and social networking sites separately. For results regarding social networking sites, we also report any thematic differences that emerged between the group interviews of users vs. non-users.

Trust (Privacy and Security)

Email.

A perceived lack of control over email content as well as worries over security threats were commonly-held concerns. Perceived lack of control sometimes referred to aspects of the technology itself, such as the fact that individuals did not have control over the ability of someone else to forward an email they sent without their knowledge. However, in other instances, it was the fact that email addresses can be passed around and used to generate unsolicited interaction or communication.

The participants believed that security threats are carried out by clever or sophisticated individuals, are extremely destructive in consequence, and are widespread in occurrence. Comments in Table 2 illustrate each of these points. Their worries over perceived security threats have had negative effects on their use of email. Participants explicitly mentioned that they have limited their use of email because they feared identity theft or other security-related issues. This limiting of email usage does not just impact the extent of social communication with relatives and friends, but also influences e-commerce and other online business transactions.

“I want to buy my tickets online and they are a lot cheaper …if you get them online. If you wanted to buy sometimes different kind of clothes, it’s much cheaper to do it online. And I guess because of identity theft I just don’t want to put my stuff out there.”

“I do have email… I have a reluctance about giving out my information for doing business and transactions …I just like doing things the old-fashioned way. I still use a telephone.”

Social networking sites.

The data highlight that trust is a major issue related to social networking site use, at least as it relates to issues of privacy and security. Although the privacy and security categories occurred at higher frequencies for the non-users than the users, both mentioned similar concerns related to trust in social networking sites. In some instances, this referred to certain aspects of the site, such as the possibility that other people could access individuals’ content (e.g., pictures) and pass it along without the individual’s knowledge or control. In other instances, participants disliked the fact that the social networking site provider itself had control over individuals’ content. Related to perceived security threats, the group-interview discussions once again revealed that participants believed these threats are carried out by clever/sophisticated individuals and are extremely destructive in consequence.

For the non-users, issues of privacy and security were sometimes explicitly mentioned as a determining factor in their non-adoption of social networking sites. Moreover, if the non-users could be convinced that these privacy and security concerns were no longer warranted, they would be more open to adopting and using social networking sites.

These privacy and security concerns mentioned during the group interviews were also reflected in participants’ responses on the Email and Social Networking Site Questionnaire. For the two items related to concerns about privacy and security on social networking sites, 88% and 94% of non-users, respectively, responded that they have not used a social networking site for these reasons in the past. Though these two numbers were lower for users than non-users, they were both above 50% (58% and 75%, respectively).

Perception of Content

Email.

The overarching theme of the perception of content category was undesired or unsolicited content. This content mainly referred to spam and ads, which participants repeatedly mentioned being sources of negative attitudes towards email. Sometimes the nature of the spam was what was troublesome, with one participant mentioning the fact that so many spams are “sexually oriented.” In other instances, the nature of the information contained in spam was not what was troublesome (e.g., related items based on previous purchases or inquiries), but the high frequency of spam or the fact that the content was not solicited was what participants disliked.

Social networking sites.

For the users, the group-interview discussion that was captured by the perception of content category consisted of the following three themes: undesired or unsolicited content, inappropriate content, and trivial content. Similar to email, undesired or unsolicited content in regards to social networking sites mainly consisted of spam and ads. However, there were instances of undesired or unsolicited content coming from the site itself that participants disliked, such as the frequent reminders from Facebook about how long it has been since their last login. Inappropriate content referred to profanity and revealing pictures that participants had observed on a social networking site, usually posted by members of a younger generation. Finally, trivial content referred to content that is publicly communicated amongst users on a social networking site that participants perceive as uninteresting or irrelevant in nature. One participant described how someone in their network would continually provide status updates stating that they “went to the store” today or “that their car was acting up.” For the non-users, the group-interview discussion that was captured by the perception of content category mainly consisted of the trivial content theme.

Current Knowledge/Skills

Email.

Participants mentioned instances where their present inability to execute a behavior within email was due to a current lack of knowledge or skills. The behaviors that participants discussed being unable to execute were usually specific in nature (e.g., attaching a photograph to an email) and not general behaviors required to use email (e.g., signing up for a new email account, replying to an email).

Social networking sites.

The behaviors that users discussed being unable to execute were usually localized in nature and not general behaviors required to use social networking sites (e.g., creating a profile, connecting with friends). For instance, one user of Facebook mentioned that they were not too knowledgeable about how to share photos through the site. In contrast to users, non-users were more likely to mention that they had a general lack of knowledge about social networking sites. This included a lack of knowledge about the use and capabilities of these sites as well as the steps required to adopt the technology. Moreover, non-users mentioned that this lack of knowledge mainly stemmed from the fact that they never received any type of education on the uses and capabilities of social networking sites.

Self-Efficacy

Social networking sites.

There occurred instances where participants suggested that a particular social networking site, or a function contained within the site, would not be within their capacity to adopt or execute. These self-efficacy beliefs occurred for non-users of social networking sites as well as users of one site but not another. There were also instances in which participants mentioned that adopting or using a social networking site would be within their capacity to learn or accomplish, but that their failure to adopt a site so far was due to other reasons. One non-user stated that they would have the ability to figure out how to use a social networking site if they “had an interest and there was a reason to.”

Negative Affect

Social networking sites.

The discussion relating to social networking sites contained a higher frequency of codes in the negative affect category, as compared to the email discussion. Interestingly, this higher frequency was observed in users of social networking sites. An examination of this discussion by users revealed that the negative affect was elicited from two different types of sources: technology-related or content-related. For the former, participants mentioned being “frustrated,” “annoyed,” or “being driven crazy” by certain features or functions of a social networking site, often functions that were perceived to be difficult to execute. In instances of content-related negative affect, negative emotions were elicited by the informational content participants observed being communicated on the social networking site.

Discussion

The UTAUT and Social Communication Technology Use in Older Adults

The qualitative content analysis of the group interviews that used an extended UTAUT framework (Venkatesh et al., 2003) revealed that the category most frequently discussed for both email and social networking sites was performance expectancy. We defined performance expectancy as the degree to which an individual believes that using the social communication technology will or will not help him or her attain gains in terms of social connectedness, entertainment, and/or information sharing. Performance expectancy is the construct of the UTAUT model which is often the strongest quantitative predictor of technology acceptance and use (e.g., Kijsanayotin, Pannarunothai, & Speedie, 2009; Taiwo & Downe, 2013). Furthermore, as it relates to technology acceptance among older adults, previous research suggested that a critical factor in whether an older adult adopts or uses a technology is the extent that the older adult perceives the technology providing a particular benefit or utility to his or her life (e.g., Liu, 2015; Melenhorst, Rogers, & Bouwhuis, 2006). Our findings support the idea that such a perspective extends to the acceptance and use of social networking sites.

The other UTAUT categories were discussed less frequently during the group interviews. However, some themes within these other UTAUT categories did emerge from the group discussion. As it relates to effort expectancy, older adults discussed the degree of ease associated with various technology-related issues for both email and social networking sites. For email, older adults also discussed the degree of ease associated with goal-related issues. As an example, participants mentioned how email made coordinating group events much easier than other methods of communication (e.g., making a series of phone calls to all members of the group).

Older Adult Users and Non-users of Social Networking Sites

Behavioral intention to use social networking sites for both older adult adopters and non-adopters was influenced by utilitarian outcomes (Maier et al., 2011). Utilitarian concern is captured by the performance category in the UTAUT. Although performance expectancy was discussed most frequently by both users and non-users of social networking sites, the two differed in the extent that they viewed social networking sites as being helpful in achieving goals. Whereas users were more likely to discuss reasons why a social networking site is or would be helpful for accomplishing their goal of maintaining social connectedness, non-users were more likely to discuss reasons why a social networking site would not be helpful. This reversed pattern of results was reflected in the different themes that emerged from the group discussions. Under the performance expectancy (helpful) category, users discussed the following three themes: information-sharing, connection-forming, and connection-strengthening. Information-sharing refers to participants believing a social networking site helps them better gather and share information; the connection-forming theme refers to instances where users mentioned that social networking sites had led them to form new connections in their social network that otherwise would not exist; the connection-strengthening theme refers to instances where users mentioned that social networking sites had strengthened already existing connections in their social networks.

In contrast, under the performance expectancy (not helpful) category, non-users discussed the following two themes: time-ineffectiveness and goal-incongruity. For time-ineffectiveness, participants mentioned that using a specific social networking site would be a waste of time and that other activities would be more beneficial in terms of entertainment and information-gathering. The goal-incongruity theme refers to instances where participants mentioned that the use of a social networking site was incongruous with their current goals. These results help provide a more detailed description of the factors that contribute to the use or non-use of social networking sites. For example, using a TAM (Davis, 1989) framework, Braun (2013) found that factors such as perceived usefulness significantly predicted intention to use social networking sites (for similar results, see Alarcón-Del-Amo, Lorenzo-Romero, & Gómez-Borja, 2012). The current qualitative results extend these prior findings by identifying which aspects of social networking sites older adults find beneficial or not beneficial towards achieving their goals. Future research that attempts to quantitatively predict social communication technology use in older adults will be aided by including items that directly measure the themes identified in the present study.

Extensions of the UTAUT

The original constructs of the UTAUT were not sufficient in completely capturing the discussion content of the group interviews. Extensions of the model are often necessary to accommodate both the technological domain and the profile of the targeted group in fully capturing the factors contributing to technology acceptance and use (Cimperman, Brenčič, and Trkman, 2016; Hoque & Sorwar, 2017). Two additional categories that were often discussed by participants in the current study were privacy and security. Older adults expressed concerns over a perceived lack of control over information shared on social networking sites. Moreover, they believed that security threats were numerous in occurrence and potentially destructive in nature. Both users and non-users expressed similar concerns regarding privacy and security, suggesting that concerns over these issues are pervasive among older adults. In fact, some non-users mentioned that privacy and security concerns were critical factors in their decisions to not join a social networking site. These results support previous research that has found privacy and security to be widely-held concerns in older adults’ opinions on internet-based technologies (e.g., Boise, Wild, Mattek, Ruhl, Dodge, & Kaye, 2013; Jung, Walden, Johnson, & Sundar, 2017). Furthermore, these results highlight that designers and proprietors of social communication technologies have not done a sufficient job in assuaging privacy and security concerns held by older adults, even older adults who are active users of these technologies. Thus, it may be beneficial for technology acceptance models to more regularly incorporate trust into their framework, especially as an increasing number of devices are used to communicate personal information through the technology.

Other categories added to the current coding scheme related to the content contained or being communicated through the technologies, including negative affect and perception of content. Though instances of negative affect mentioned by participants were elicited by a variety of factors, including stemming from difficulties with the technology itself, many of the instances of negative affect were in response to content that is shared through social communication technologies. Similarly, the perception of content category referred to instances where participants believed the content of a social communication technology was uninteresting, irrelevant, and/or inappropriate (also see Prakash, 2016). These results highlight the fact that individuals can have opinions and attitudes towards different aspects of social communication technologies, such as opinions about the technological platform itself as well as about the information that is shared through the technology. The information that an individual is exposed to through a social communication technology will vary from person to person, based on things such as friend networks and the groups or pages one chooses to follow. As a result, it can be difficult to predict how an individual will respond to a social communication technology such as a social networking site, because there is no standard user experience for the technology. However, individual older adults, particularly older adults who are non-users or recent adopters of a social communication technology, may not be aware of the amount of control they have in customizing the information they are exposed to through the technology. These capabilities of social networking sites must be made clearer to older adults, so that they can alter and improve the content being communicated on their site. Thus, providing instructional support could not only provide older adult users with the support they desire, but could also improve their self-efficacy using the social networking site and reinforce continued usage over time.

In the context of social communication technology use, privacy and security concerns were frequently discussed by older adults, providing a rationale for including these factors as extensions of the UTAUT. However, any extension of a model must be weighed against the effectiveness and generalizability of a more parsimonious model. Constructs that are added to a model to more reliably predict behavior in one domain will not necessarily be relevant for behavior in other domains. For instance, the adoption of a technology that does not include the sharing or storing of personal or sensitive information may not depend on trust in the technology. That is, the extension of a model will depend on context and the characteristics of a targeted population. The UTAUT was recently updated (UTAUT2; Venkatesh, Thong, & Xu, 2012) to predict technology acceptance and use in consumer contexts (e.g., Morosan & DeFranco, 2016; Slade, Williams, & Dwivedi, 2014). Additional constructs were incorporated into the model such as price value, habit, and hedonic motivation. As social communication technologies are usually free to join, with any associated costs mainly stemming from the technologies that support them (e.g., computers, smartphones, internet connection), and as older adults may be non-users of such technologies, constructs such as price value and habit are likely not relevant factors regarding technology acceptance and use for this population. The qualitative results of the group interviews provide direction for which factors and extensions of the UTAUT are more likely to predict older adults’ adoption and use of social communication technologies.

Acceptance of Different Social Communication Technologies by Older Adults

By including questions regarding email in the interviews, we were able to explore older adults’ opinions on social communication technologies at different stages of adoption. The patterns of discussion content regarding email paralleled the discussion content of the user groups towards social networking sites. For example, participants were more likely to discuss reasons why email would be helpful in achieving their goals of maintaining social connectedness, entertainment, and/or information sharing. This contrasted with how non-users discussed social networking sites, which indicates that older adults perceive different social communication technologies to have varying levels of utility or benefits. This is not just the case between different technologies such as email and social networking sites, but also between different social networking sites themselves.

Though users of social networking sites were more likely to discuss reasons why social networking sites would be helpful in achieving their goals, they still discussed reasons why these sites would be or are not helpful. In many of these instances, participants were talking about a specific site that they did not use or with which they had limited experience. This means that just because an older adult has expressed the desire or intention to join and actively use one social networking site, it does not follow that that desire will necessarily transfer to another social networking site. Designers of social networking sites must keep this in mind when trying to expand their older adult user base. That is, the benefits associated with a social networking site must be made clear to potential users, and it cannot be assumed that because an individual is receptive to one social networking site, or social networking sites more generally, that individual will be easily receptive to a new site.

Conclusions

When discussing their perceptions and attitudes towards various social communication technologies (e.g., email, social networking sites), older adults most frequently discussed whether the technologies would or would not provide benefits toward their lives. Discussed less frequently were concerns that older adults would not be able to use the technologies if they so desired to. Well-established technology acceptance models (e.g., TAM, UTAUT) include constructs that account for this discussion content, however these models will not always account for the major factors that contribute to the adoption or use of a particular technology. The current results demonstrated that for the use of social communication technologies by older adults, additional constructs such as trust in the technology and the perception of content communicated through the technology contribute to attitudes toward the technology. Future work will be needed to quantitatively measure these constructs to explore how they add incremental validity to the prediction of social communication technology adoption and use. This will then allow the ability to explore what variables moderate these predictive relationships, which will help inform any intervention, product development, or design implementation aimed at increasing the adoption rate of social communication technologies in the older adult population (e.g., Coelho, Rito, & Duarte, 2017).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (NRSA) Institutional Research Training Grant 2T32AG000175-26A1, Grant P01 AG17211 under the auspices of the Center for Research and Education on Aging and Technology Enhancement (CREATE; www.create-center.org) from the National Institutes of Health (National Institute on Aging), and the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Community Living) Grant 90RE5016-01-00l. We appreciate the contributions of Jackie Gilberto to this project.

References

- Alarcón-Del-Amo M-D-C, Lorenzo-Romero C, & Gómez-Borja M-A (2012). Analysis of acceptance of social networking sites. African Journal of Business Management, 6(29), 8609–8619. 10.5897/AJBM11.2664. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M (2015). Technology Device Ownership: 2015. Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Ballantyne A, Trenwith L, Zubrinich S, & Corlis M (2010). ‘I feel less lonely’: What older people say about participating in a social networking website. Quality in Ageing and Older Adults, 11(3), 25–35. 10.5042/qiaoa.2010.0526. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. http://dx.doi.Org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1997). Self-Efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: W. H. Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Barg-Walkow LH, Mitzner TL, & Rogers WA (2014). Technology Experience Profile (TEP): Assessment and Scoring Guide (HFA-TR-1402). Atlanta, GA: Georgia Institute of Technology, School of Psychology, Human Factors and Aging Laboratory. [Google Scholar]

- Bixter MT, Blocker KA, & Rogers WA (2018). Enhancing social engagement of older adults through technology In Pak R and McLaughlin A (Eds.), Aging, Technology and Health. Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Blagojevic M, Jinks C, Jeffery A, & Jordan KP (2010). Risk factors for onset of osteoarthritis of the knee in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 18(1), 24–33. 10.1016/j.joca.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohannon RW (1997). Comfortable and maximum walking speed of adults aged 20-79 years: Reference values and determinants. Age and Ageing, 26(1), 15–19. 10.1093/ageing/26.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boise L, Wild K, Mattek N, Ruhl M, Dodge HH, & Kaye J (2013). Willingness of older adults to share data and privacy concerns after exposure to unobtrusive in-home monitoring. Gerontechnology, 11(3), 428–435. doi: 10.4017/gt.2013.11.3.001.00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley EH, Curry LA, & Devers KJ (2007). Qualitative data analysis for health services research: Developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Services Research, 42(4), 1758–1772. https://doi.Org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun MT (2013). Obstacles to social networking website use among older adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 29, 673–680. https://doi.Org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.12.004. [Google Scholar]