Abstract

Objectives:

We used focus groups to understand cigar product features that increase the appeal of blunts (hollowed out cigars filled with marijuana) among adolescents and young adults.

Methods:

With a standardized focus group guide, we assessed cigar use behaviors and perceptions among lifetime cigar users (N = 47; 8 focus groups separated by sex and age group [adolescents, young adults]) in 2016. We analyzed data related to blunts.

Results:

Overall, 85.5% of the participants had smoked a blunt in the past 30 days (38% used daily). Participants perceived that cheap cigar brands were used primarily for blunts. Cigar product features that made them useful for blunts included wide availability, easy accessibility (easy to bypass underage purchasing restrictions), attractive flavors, inexpensive cost, perforated wrappers that make cigars easy to open, and ability to remove the inner wrapper (also referred to as “cancer paper”) to reduce the risk of harm.

Conclusions:

Various product features of cigars make it easy for adolescents and young adults to manipulate them to create blunts. Tobacco regulations that include restrictions on product characteristics, as well as enforcement of prohibition of sales of cigars to underage minors are needed. Youth also need to be educated about harms of blunt use.

Keywords: blunts, cigars, adolescents, young adults, qualitative study

United States (US) national data indicate that past 30-day cigar use (which includes little filtered cigars, big premium cigars, and cigarillos) among adolescents decreased from 11.6% in 2011 to 7.7% in 2016.1 Despite the decrease in prevalence of use, it is still the third highest used tobacco product among adolescents following e-cigarettes and cigarettes.1 Furthermore, a growing body of evidence suggests that the prevalence of cigar use among adolescents may be underestimated because questions used to assess cigar use often do not use brand names that adolescents often use to refer to the product.2-4 Moreover, adolescents who use cigars for blunts (ie, hollowing out the tobacco in the cigar, replacing it fully or partly with marijuana, and rolling it back to the original shape5,6) do not identify themselves as cigar users.7,8

Cigar use is not safe and it is not a safer alternative to cigarette smoking.9,10 Like cigarettes, cigars are a combustible tobacco product that cause various cancers and coronary heart diseases.9,10 However, cigars have not been subjected to strict regulations like cigarettes, and such gaps in regulations allow for a diverse range of cigar products on the market, such as premium large cigars, inexpensive machine-made cigars that are medium-sized cigarillos (usually unfiltered and which sometimes come with plastic or wooden tips), and littles cigars, which are essentially indistinguishable from cigarettes.11 These inexpensive cigars like cigarillos or little cigars are widely available and have features that are appealing to youth, such as enticing flavors and packaging.12,13 Cigars also are widely used by youth to co-use tobacco and marijuana by creating blunts; about two-thirds of adolescent cigar users14 and nearly half of young adult cigar users report that they are using cigars to create blunts.15

Blunt use also is not without health risks. Even when all of the filler tobacco is removed, blunt users are still exposed to nicotine through cigar wrappers that contain nicotine. One analysis showed that cigar wrappers contained nicotine levels ranging from 1.2 mg to 6.0 mg.16 Blunt use is especially concerning given the additive adverse health effects of co-use of tobacco and marijuana than use of either substance alone.17,18 For instance, co-use of tobacco and marijuana is associated with other substance use and psychological disorders17,19 and increased use and greater dependence on both nicotine and marijuana among adolescents and adults.20-22 Additionally, relative to joint use (marijuana wrapped in a cigarette paper that does not contain nicotine), blunt use exposes users to greater carbon monoxide and health risks, such as increased heart rate.23,24

Existing qualitative studies conducted among adolescents and young adults have shed some light on perceptions and use behaviors related to blunts.5,25-28 The existing studies indicate that blunts may be popular among youth because cigars used to create blunts are inexpensive and they are widely available in local stores.29 Furthermore, the process of creating and smoking blunts often occurs as a social activity among adolescents and adults.5,30 Blunts also are marketed heavily by popular celebrities, which also appeals to youth.5,31 Existing evidence from adult cigar users has further provided insight into the unique product characteristics of cigars that make them particularly useful to create blunts.25 For instance, certain cigar brands have perforated lines on the wrappers or have wrappers that can be easily unrolled to facilitate blunt making, and these cigar brands are perceived to be used exclusively for blunts.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has the authority to regulate cigars, along with other tobacco products as of 2016.32 Many of the cigar product features that appeal to youth can be regulated under this new law. Thus, information on the appeal and use behaviors of cigars for blunt creation among adolescents and young adults is critical to help the FDA develop evidence-based regulations to prevent youth cigar and blunt use. Our goal in the current study was to use qualitative information from focus groups conducted with adolescent and young adult cigar users to identify specific cigar features that enhanced their appeal for creating blunts. We examined cigar product features used for blunt creation, such as cigar types, brands, as well as the role of flavors, filler tobacco and wrappers. We also assessed perceptions related to blunt use, including comparative harm perceptions to other marijuana use methods (eg, joints).

METHODS

Participants

We conducted 8 focus groups (N = 47; 42.6% female participants, 53.2% adolescents, 46.8% young adults, range of participants per group = 4 to 8) among ever cigar users (ie, lifetime cigar users), separated by sex and age group (ie, 2 male adolescent, 2 female adolescent, 2 male young adult, and 2 female young adult groups) in New Haven County, Connecticut (a large, mixed urban-suburban-rural county 90 miles northeast of New York City), February-July 2016. The mean age of adolescents was 16.36 (SD = 0.91); the mean age of the young adults was 20.91 (SD = 1.51). The sample was 29.8% white, 19.1% black, 14.9% Hispanic, and 36.2% mix/other races. Race/ethnicity did not differ by sex and age group.

Procedures

Detailed focus group study procedures could be found in Kong et al.12 In brief, adolescent cigar users were recruited in 2 high schools in Connecticut using flyers in schools, as well as in-person recruitment sessions held during lunch periods. Prior to any study procedures, a letter detailing the study was sent to all high school parents instructing them to contact the researchers if they declined their child’s participation in the focus groups (no parents declined). Both adolescents and parents were informed that although adolescent’s cigar use would not be revealed to anyone other than the research team, there was a possibility that the school staff and students may find out about the adolescent’s cigar use status and their participation in the study because the focus groups were held in the schools at the end of the school day. Young adults (ages 18-25) were recruited through Facebook and Craigslist advertisements, as well as flyers in the community. Young adult focus groups were held in a conference room in our office building. All those who were interested were screened over the phone. To be eligible, adolescents and young adults had to report ever using a cigar product in their lifetime and agree to participate in a focus group to discuss cigar use and perceptions. All participants provided verbal assent (if younger than 18 years old) and consent (if 18 years and older) before participating in the focus group.

The overall goal of the focus groups was to assess perceptions and cigar use. The standardized focus group guide also had broad questions to assess blunt use, eg, How do you use cigars to create blunts? How is blunt smoking different from other forms of marijuana smoking? Although we used these questions as a guide, we also asked follow-up questions to probe if more information or clarification was needed. In the current study, we analyzed the data on the use of cigars for blunts and perceptions related to blunts.

At the end of the focus groups, participants completed a brief, anonymous questionnaire that assessed demographic information, such as sex, age, race/ethnicity, and cigar and blunt use behaviors (ie, number of days of cigar use with and without adding marijuana and cigar brands used in the past 30 days).

Participants were paid $25 for their participation in the hour-long focus groups and refreshments were provided. In addition, participants were debriefed after the focus groups that the goal of the research was to improve understanding of cigar use and perceptions, that we did not support the use of tobacco products due to known health risks, and that our research was funded by the National Institutes of Health and not by the tobacco companies.

Data Analysis

Audio-recordings were transcribed verbatim by a transcriptionist, and all transcripts were checked by another research staff. The qualitative analysis was conducted using Atlas.ti7 (Version 7.1.8). The transcripts were coded by 3 independent coders (2 research assistants and the first author).

Deductive and inductive approaches guided our analysis. We first took a deductive approach and coded themes determined a priori based on the focus group guide (eg, cigar brands used to make blunts, how cigars are used to make blunts, reasons for blunt use, comparative perceptions of smoking marijuana using blunts relative to other marijuana smoking methods). Then, we used an inductive approach based on participant responses to identify new emergent themes (eg, terms used to refer to blunts, the role of flavors in blunt creation, harm perceptions regarding the inner wrapper, the role of tobacco filler in blunt creation).

The responses to the anonymous questionnaire were analyzed using SPSS 24. We conducted descriptive and bivariate analyses to characterize demographic characteristics, as well as cigar and blunt use behaviors in the past 30 days. Based on the responses to the past 30-day use of cigars with and without manipulation into blunts, participants were coded as users of cigars and blunts, cigars only, blunts only, or no product.

RESULTS

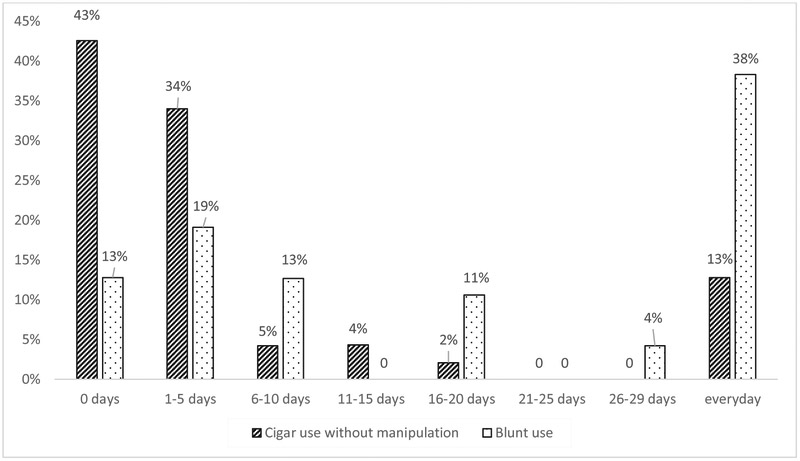

The survey data showed that past 30-day use of cigars (without manipulation) and blunts varied among participants: 44.7% used cigars and blunts, 40.8% used only blunts, 12.8% used only cigars, and 2.1% did not use either cigars or blunts. Frequency of use in the past 30 days also varied; blunts were used more frequently than cigars (Figure 1). Female participants smoked cigars without manipulation more frequently in the past 30 days than male participants (10.45 days [SD = 13.58] vs 2.37 days [SD = 4.34]), but there were no sex differences in the days of blunt use (Table 1). The frequency of days of cigar use and blunt use did not differ by age group.

Figure 1.

Days of Cigar Use and Blunt Use in the Past 30 Days

Table 1.

Cigar/Blunt Use Characteristics Stratified by Age Group and Sex

| Adolescents (N = 25) |

Young Adults (N = 22) |

Statistics, p value |

Female Participants (N = 20) |

Male Participants (N = 27) |

Statistics, p value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cigar/Blunt Use Status | χ2 = 4.86, p =.182 |

χ2 = .879, p = .830 |

||||

| No Cigar/Blunt Use (%) | 4.0% | 0% | 0% | 3.7% | ||

| Only Cigar Use (%) | 4.0% | 22.7% | 15.0% | 11.1% | ||

| Only Blunt Use (%) | 48.0% | 31.8% | 40.0% | 40.7% | ||

| Cigar and Blunt Use (%) | 52.4% | 45.5% | 45.0% | 44.4% | ||

| Blunt Use Days (M, SD) | 18.29, 12.42 | 15.0, 13.40 | t= .865, p = .392 |

17.63, 13.19 | 16.07, 12.84 | t = −.401, p = .691 |

| Cigar Use Days (M, SD) | 3.36, 6.97 | 8.59, 12.46 | t = −1.80, p = .078 |

10.45, 13.58 | 2.37, 4.34 | t = −2.91, p = .006 |

The themes identified from the focus groups were consistent across age group and sex and are described in the following section. Table 2 lists all main themes and subthemes listed in this section, as well as example quotation(s) for each.

Table 2.

Example Quotations Based on Themes Related to the Use of Cigars for Blunts

| Main Themes | Subthemes | Example Quotations | Sex/age group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Terms Used for Blunts | N/A | “I usually call them by the brand name. Like yea, Swishers or Dutch Master or whatever.” | Male young adult |

| Cigar Product Features That Are Useful for Blunts | Cigars Used Primarily for Blunts | “It’s mostly like weed and stuff that they use it for. They don’t really use the cigar just to really smoke the cigar.” | Female adolescent |

| “I don’t know a lot of people who smoke them with the tobacco in them, like almost everybody I know smokes them with like weed in them. So obviously, I feel like if they advertised it would be like advertising weed indirectly.” | Female adolescent | ||

| Cigar Brands Used for Blunts | “Well, no those are two different things basically. Like we use Entourage and Games to roll up, like no one uses a Black to roll up.” | Female adolescent | |

| The Role of Cigar Wrappers in Blunts | “You cut it straight down, and most, some dutches, they’ll have like a line, if you look around there will be a line, it will be easier for you to crack, not that you’re cracking, you dump all the guts out and put in the weed and roll it up.” | Male adolescent | |

| “It’s (referring to ZigZag) for beginners, you don’t have to crack them.” | Female young adult | ||

| The Role Of Cigar Flavors in Blunts | “Personally like I said, I only taste it on my lips. I don’t taste it when I’m smoking it and when I’m smoking all I smell is the weed” | Female adolescent | |

| “It’s like you’re smoking like grape flavored weed.” | Female young adult | ||

| Harm Perceptions Regarding the Inner Wrapper | “You get cancer from it, it’s pretty self-explanatory.” | Male adolescent | |

| “It’s just more of a known fact that people say oh just take that off, don’t forget that.” | Male adolescent | ||

| “I don’t really know what it is but I know a lot of people peel off the inner layer, peel it off because they say it’s better for you and that that inner layer is the cancer paper part so they just use the outside of the leaf.” | Female adolescent | ||

| The Role of Tobacco in Blunts | “I have to agree with both of them because cigarettes you smoke the tobacco, but in a dutch you actually take it out which is like less chemicals and stuff.” | Female young adult | |

| “I used to spliff it a lot with like clove cigarettes. It was like a very nice combination I found. And you could kind of smoke them in public and people would give you a side eye but it’s a clove cigarette.” | Male young adult | ||

| “Like it gets the same effect from a cigarette while you’re smoking [blunts] or after you smoke [blunts], it gives you the cigarette high on top of the already high you are, so it kind of like just keeps you at that level.” | Female young adult | ||

| Use of Blunts Relative to Other Marijuana Use Methods | Easy Accessibility | “I’m seventeen but I know a lot of times my friends will buy them for me or I have older sisters. But there are some places they’ll be like, Oh, you’re eighteen?’ .And you tell them, ‘yes’. They’ll be like, ‘okay.’” | Female adolescent |

| Social Reasons | “Everyone…I would say from athletes to honor students…nerds that just hit the books and like everybody [uses blunts].” | Male adolescent | |

| “It’s just around you like the most, you don’t you see a lot of people with papers.Like, I don’t see a lot of people with papers [referring to cigarette papers], everybody, they got a dutch.” | Male adolescent | ||

| Presence of Blunts On Social Media | “I looked up [on YouTube] how to roll like, not, like, normal stuff. Like did, like, a cross joint. Like a tulip [referring to names of different blunt rolling methods].” | Male adolescent | |

| Presence Of Blunts In Music Videos | “In music videos, right. They sometimes like be waving up the dutch, like for example, like Backwoods that’s what they mostly use now, like celebrities.” | Male adolescent | |

| Easy Accessibility | “Dutches are easier to get than papers [ie, cigarette paper].” | Male adolescent | |

| Easy to Roll | “And it’s [referring to cigarette paper] harder to use too. Some people like, even for me I’ve rolled them sometimes good sometimes bad. Some days, I’m like you know what? Forget it I am just going to go back to dutch, I can’t roll papers.” | Male young adult | |

| Burns Slow | “Cigars burn slower so. So when you’re smoking, it’s like your high lasts long because you’re getting high and you’re still smoking…” | Female young adult |

Terms Used for Blunts

Participants used various terms to refer to blunts (eg, “dutch, cigar brand names) and blunt use (eg, “smoking). Participants in all focus groups understood and used the term “blunts.” Although the focus groups included adolescents and young adults currently residing in Connecticut, one young adult participant originally from Ohio and another young adult participant from California reported using different terms to refer to blunts (eg, “shells” used by male young adult from Ohio).

Cigar Product Features that are Useful for Blunts

Each step of blunt creation underscored cigar product features useful for creating and smoking blunts, as well as some misperceptions regarding these components. The methods to create blunts using cigars is described as the following:

“I crack the dutch. I take the tobacco out. After I take off the cancer paper, I lick it and then I start breaking the weed up in it. Then I just roll it up and lick it and dry it off, light it and smoke. ”

Male adolescent

Type of Cigars Used for Blunts

Cheap cigars sold at local stores were used to create blunts. Participants perceived that these cigars were manufactured and used exclusively for this purpose. The top cigar brands used by participants were Garcia y Vega Game (referred to as “Games”), followed by Dutch Masters, Entourage, and Black and Mild (Figure 2). Participants reported that all cigar brands, except for Black and Mild, were used to create blunts. Survey data showed that past 30-day blunt users were less likely than cigar only users to use Black and Mild (17.5% vs 66.7%, χ2 (1, N = 47) = 6.93, p = .008). There were no differences in other brands used between blunt users and cigar users.

Figure 2. Cigar Brands Used in the Past 30 Days.

Note. The percentages do not add to 100% because multiple brands could be reported.

The Role of Cigar Wrappers in Blunts

The first step in creating a blunt was to break the cigar in half using the fingers or sharp objects like a knife. Some cigar wrappers had perforated lines on the wrappers and some cigar wrappers could be easily unrolled like a “candy cane” that made it easy to break open. These features were seen as appealing because it allowed anyone without experience to create blunts.

The Role of Cigar Flavors in Blunts

Cigar flavors enhanced the experience of creating blunts and the smoking experience. Some participants reported that picking out new cigar flavors was the favorite part of the blunt creation process. Participants reported enjoying the sweet aroma when they first opened the package and when they tasted the wrapper as they licked it to create a blunt. They also reported tasting the sweet flavor when they first started puffing the blunt but not while they smoked the blunt. Some reported that the mix of marijuana and cigar flavors enhanced the marijuana flavor.

Harm Perceptions Regarding the Inner Wrapper

All participants reported removing the inner wrapper that holds the tobacco together (referred to as the “cancer paper”) when creating blunts. All participants reported removing the “cancer paper” to reduce harm and that the notion of the cancer paper was “a known fact;” however, no one recalled the source of this information.

The Role of Tobacco in Blunts

Most participants removed the tobacco from the cigar while creating blunts because of the perception that the tobacco in the cigar tastes “bad” and for reducing health risks. However, some also reported mixing tobacco with marijuana (ie, “spiffing”). The tobacco used for “spiffing” was sometimes obtained from other tobacco products, such as clove cigarettes or cigarettes. The reasons provided for “spiffing” included “boosting the high” and to “make the weed burn longer.” Some participants also reported smoking a cigarette after smoking a blunt to “boost the high. ”

Use of Blunts Relative to Other Marijuana Use Methods

When asked about their reasons for using blunts relative to other marijuana use methods, participants typically compared blunts to joints. The majority preferred to smoke marijuana using blunts versus other marijuana use methods (eg, joints). Relative to blunts, joints were perceived to be healthier and less harsh. On the other hand, blunts were preferred because of greater availability of cigars and convenience of obtaining cigars. Participants reported purchasing cigars at convenience stores and gas stations; even among underage minors, obtaining them was easy. Many reported that the store clerks did not check their IDs when they tried to purchase cigars. Some reported that clerks were less likely to check their IDs when buying cigars than when buying cigarettes.

Participants also preferred the social aspects of creating and using blunts. Participants reported that most of their peers used blunts and their first blunt use was with friends/siblings/cousins. Peers were the common source of learning how to create blunts, but some also used YouTube videos to learn novel ways to roll a blunt. In addition to peers, other appealing aspects of blunts were the promotion of use by celebrities on social media (eg, Instagram, Snapchat, Twitter) and music videos. Other reasons for the preference for blunts versus joints included their being easier to roll, fitting more marijuana because they were larger, and burning slower and lasting longer.

DISCUSSION

The focus groups with adolescent and young adult cigar users identified appealing features of cigars that were important for creating and smoking blunts. Cigar product features important for blunts were appealing flavors, wrappers that were easy to open, and wrappers that were larger than cigarette wrappers used for joints (which allowed for more marijuana and slower burning time). Other appealing aspects were wide availability of cigars (eg, sold at local convenient stores and gas stations at a low price), convenience of obtaining cigars (eg, easy to bypass restrictions on underage purchasing of cigars), and the social aspects of creating and smoking blunts.

While all participants used the term “blunts,” they also used other terms. Terms such as “smoking” and specific cigar brand names were used interchangeably to refer to smoking blunts, cigars without manipulation, and cigarettes. Thus, it was important to clarify throughout the focus groups the product to which participants were referring. Our findings corroborate the findings from existing literature that suggest that when assessing cigar use, more detailed information, such as brand names, is needed.2,4,7,28,31,33-36 Our findings also expand previous research by suggesting that when assessing cigar use, the use of cigars without manipulation or the use of cigars by manipulating them into blunts should be considered.

Similar to a previous qualitative interview study indicating that adults perceived cheap cigars were created solely for blunt use,25 both adolescents and young adults in our study shared this perception. We also observed that participants were using many different cigar brands (ie, 11 unique cigar brands were used in the past 30 days) for blunt use. Although our participants reported using most cigar brands for blunts, interestingly, as with adults in a previous study,25 our adolescent and young adult participants did not use Black and Mild to create blunts. Also, interestingly, whereas most cigar brands identified in this study corresponded to the brands used by adolescents in Massachusetts in the early 2000s, there were some notable differences.33 For instance, Soldz et al33 observed that adolescents preferred to use Phillies the most, but our focus group participants did not report using Phillies. Interestingly, the term “blunts” stem from the brand name “Phillies Blunt.”

Our focus group participants reported also using other brands such as Entourage and Zigzag, which were not reported in the Soldz et al study. These differential findings could suggest evolving trends in brand marketing over time and over region. Certain brands may have features that are appealing to youth and these features should be explored. For instance, youth find the perforated wrappers or wrappers that peel appealing because they allow the cigar to be taken apart easily to create blunts. The appeal of this cigar feature was identified by a previous study with adults;25 however, we observed that youth also were aware of this feature and preferred this feature because it enabled novice blunt users to make their own blunts. These findings suggest that comprehensive cigar regulations to prevent youth cigar use could include prohibiting cigar companies from designing and manufacturing features of the products that could be used to manipulate the product easily to create blunts.

Flavored cigars are popular among youth,37,38 and appealing flavors are cited as the most common reason for cigar initiation among adolescents.13 We observed that flavors were critically important in creating a blunt. Participants enjoyed trying a new cigar flavor; specifically, they reported liking the aroma when first opening the package, as well as the taste from licking the wrapper, and taking the initial puffs. However, they also reported that they no longer tasted or smelled the flavor after the initial puffs, suggesting that flavors are experienced at the initial phase of blunt creation/smoking. Mixing cigar flavors with marijuana also was perceived to enhance the taste of marijuana, which was also observed in other studies.25,39 Our findings contribute to the growing literature showing the positive role of flavors on youth cigar use and expands current understanding of the appeal of flavored cigars on blunt use as well.

Given the FDA’s regulatory authority over cigars, it is more important than ever to understand the role of cigars in blunts. Blunt use is not only a form of marijuana use but it is also a form of tobacco use. Although the tobacco inside the cigar is replaced with marijuana, the tobacco wrapper still contains nicotine, unlike cigarette wrappers.16 Some youth mixed tobacco and marijuana (ie, “spliffing”) to make the blunt burn longer and to share it with friends.40 Some also reported smoking a cigarette after blunt use (ie, “chasing”).5,26,40,41 Both methods have been reported to enhance the high or to prolong the high from marijuana.5,26,40,41 The concurrent use of marijuana and tobacco through blunts, as well as adding more tobacco through “spliffing” and “chasing” raises the concern that youth are being exposed to greater harm and addiction to both marijuana and nicotine.20 However, less is known about how blunt use is associated with long-term use of both substances. Thus, future studies should assess trajectories of tobacco and marijuana use patterns, such as whether blunt use leads to tobacco use and dependence among youth who would otherwise have not used a tobacco product.

A finding of concern was that youth had some notable misperceptions about the health risks of cigars and blunts. For instance, youth perceived that removing the inner wrapper that keeps the tobacco together, referred to as the “cancer paper,” reduces the harm associated with cigar and blunt use. Although our focus group participants did not report removing the “cancer paper” when they did not manipulate the cigar into blunts, others have reported this behavior (ie, “freaking” or “hyping”).42 A previous study examined the viability of the urban myth of “cancer paper” and observed that removing the inner wrapper did not reduce toxin exposure.43 Despite the lack of evidence for the claim of “cancer paper,” this belief is still being shared widely among youth. Furthermore, our findings showed that the source of information regarding the “cancer paper” was unknown. Educational and prevention campaigns should debunk the false belief of “cancer paper” and that removing the inner wrapper reduces the risk of harm.

Consistent with the well-documented literature of social influences on tobacco use among adolescents,44 we also observed that peers were important in initiating and using blunts. Blunt use is different from other tobacco and marijuana use in that the ritual of creating blunts and smoking blunts often occurs in a group activity.28,30 Thus, it is not surprising that most youth reported that their first experience with blunts and their primary source of information regarding learning how to create and smoke blunts was peers. Social sources (eg, older peers, adults) were also a common source for acquiring cigars among underage youth.

Another source of information for blunts was through social media and music videos. Focus groups conducted with adolescents 17 years ago also observed that cigars were heavily marketed using hip-hop stars.31 Unfortunately, similar types of marketing still exist today, with popular hip-hop stars such as Snoop Dogg promoting the use of blunts on music videos, concerts and social media.45 The main difference between the focus groups conducted 17 years ago and in the present is that today, youth are accessing this pro-tobacco and marijuana content via social media, which is difficult to regulate. Pro-blunt use content has been identified in popular social media websites such as Twitter46-49 and Instagram.50,51 Exposure to promarijuana messages is associated with increased odds of using marijuana among adolescents;52 thus, effective campaigns should counteract pro-tobacco and marijuana communication.

Our findings also demonstrated that youth were using YouTube videos to learn novel ways to roll a blunt, which is consistent with the existing literature suggesting that novel tobacco use behaviors are learned through YouTube videos.53 Although the content of social media websites are unregulated due to their first amendment rights, the public and health organizations can request the removal of offensive materials or other materials that use copyright materials.54 Such efforts are needed to reduce the exposure of pro-tobacco materials that are easily accessed by youth.

Finally, we observed that bypassing underage restrictions for purchasing cigars was easy. This finding is consistent with the findings from Ohio showing that 64% of underage adolescent cigar users have purchased cigars.55 Moreover, our participants reported that bypassing underage restrictions was easier for cigars than it was for cigarettes, suggesting that stronger enforcement of underage tobacco laws is needed.

This study has several limitations. The overarching goal of the focus groups was to assess cigar use, so the responses may have been different had we recruited blunt users. However, this concern is mitigated because most participants (85.5%) reported using blunts in the past 30 days. Additionally, the qualitative nature of the study and its geographic location may limit the generalizability of our findings. Large population-based studies are needed to gain better understanding of these behaviors and perceptions. However, qualitative data are important because they allow identification of important themes for examination in future studies.

IMPLICATIONS FOR TOBACCO REGULATION

In conclusion, our findings replicate previous study findings on the appeal and perception of blunts, such as perceptions that removing “cancer paper” reduces harm, that cigars are easy to access, and that the appeal of product features enhances blunt creation (eg, easy to peel wrappers). These findings suggest that more prevention and education efforts are needed to reduce youth appeal and access, and correct misperceptions. We also have novel findings. For instance, we identified new terms/brands used to refer to blunt use (eg, Entourage). We also identified more specific ways in which cigar flavors appeal to adolescents and young adults. Whereas flavor has been identified as an important reason for cigar use among adolescents,12,13 less known is how flavors are experienced. Our findings showed that flavors were important during blunt creation and initial exposure (puffs), but they were no longer experienced while smoking the blunt. Finally, we identified that adolescents and young adults were exposed to pro-blunt use content on social media.

These findings suggest that a comprehensive tobacco prevention campaign should consider concurrent use of tobacco and marijuana through the use of blunts, as well as correct the widely-shared faulty perception of “cancer paper,” and that harm is not reduced by removing this paper. Cigar regulations could include prohibiting perforated wrappers or wrappers that can be easily peeled, as well as enticing flavors to reduce the youth appeal. Finally, the compliance of restrictions of sale of cigars to underage minors from convenience stores and other retailors need to be monitored and reinforced.

Acknowledgements

The research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Center for Tobacco Products (CTP; P50DA036151; Yale TCORS). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the Food and Drug Administration.

Footnotes

Human Subjects Approval Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yale University and the local school administrators.

Conflict of Interest Statement

None to report

Contributor Information

Grace Kong, Yale School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry, New Haven, CT..

Dana A. Cavallo, Yale School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry, New Haven, CT..

Alissa Goldberg, Yale School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry, New Haven, CT..

Heather LaVallee, Yale School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry, New Haven, CT..

Suchitra Krishnan-Sarin, Yale School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry, New Haven, CT..

References

- 1.Jamal A, Gentzke A, Hu SS, et al. Tobacco use among middle and high school students -United States, 2011-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:597–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corey CG, Dube SR, Ambrose BK, et al. Cigar smoking among U.S. students: reported use after adding brands to survey items. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(2, Suppl 1):S28–S35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rait MA, Prochaska JJ, Rubinstein ML. Reporting of cigar use among adolescent tobacco smokers. Addict Behav. 2016;53:206–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nasim A, Blank MD, Berry BM, Eissenberg T. Cigar use misreporting among youth: data from the 2009 Youth Tobacco Survey, Virginia. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9(E42). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sifaneck SJ, Johnson BD, Dunlap E. Cigars-for-blunts: choice of tobacco products by blunt smokers. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2005;4(3-4):23–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Golub A, Johnson BD, Dunlap E. The growth in marijuana use among American youths during the 1990s and the extent of blunt smoking. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2005;4:1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yerger V, Pearson C, Malone RM. When is a cigar not a cigar? African American youths’ understanding of “cigar” use. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(2):316–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soldz S, Huyser DJ, Dorsey E. The cigar as a drug delivery device: youth use of blunts. Addict. 2003;98(10):1379–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baker F, Ainsworth SR, Dye JT, et al. Health risks associated with cigar smoking. JAMA. 2000;284(6):735–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Cancer Institute (NIH). Cigars: Health Effects and Trends. Bethesda, MD: NIH; 1998. Available at https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/tcrb/mono-graphs/9/index.html. Accessed July 29, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Food and Drug Administration. Cigars, Cigarillos, Little Filtered Cigars. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/Labeling/ProductsIngredientsComponents/ucm482562.htm. Accessed May 30, 2017.

- 12.Kong G, Cavallo DA, Bold KW, et al. Adolescent and young adult perceptions on cigar packaging: a qualitative study. Tob Regul Sci. 2017;3:333–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kong G, Bold KW, Simon P, et al. Reasons for cigarillo initiation and cigarillo manipulation methods among adolescents. Tob Regul Sci. 2017;2:S48–S58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trapl ES, Koopman Gonzalez SJ, Cofie L, et al. Cigar product modification among high school youth. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018;20(3):370–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Behavioral Health Trends in the United States: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. (DHHS Publication No. SMA 15-4927, NSDUH Series H-50). Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2015: Available at https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FRR1-2014/NSDUH-FRR1-2014.pdf Accessed July 29, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peters EN, Schauer GL, Rosenberry ZR, Pickworth WB. Does marijuana “blunt” smoking contribute to nicotine exposure? Preliminary product testing of nicotine content in wrappers of cigars commonly used for blunt smoking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;168:119–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peters EN, Budney AJ, Carroll KM. Clinical correlates of co-occurring cannabis and tobacco use: a systematic review. Addict. 2012;107(8):1404–1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramo DE, Liu H, Prochaska JJ. Tobacco and marijuana use among adolescents and young adults: a systematic review of their co-use. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32(2):105–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohn A, Johnson A, Ehlke S, Villanti AC. Characterizing substance use and mental health profiles of cigar, blunt, and non-blunt marijuana users from the National Survey of Drug Use and Health. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;160:105–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Timberlake DS. A comparison of drug use and dependence between blunt smokers and other cannabis users Subst Use Misuse. 2009;44(3):401–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Badiani A, Boden JM, De Pirro S, et al. Tobacco smoking and cannabis use in a longitudinal birth cohort: evidence of reciprocal causal relationships. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;150:69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fairman BJ. Cannabis problem experiences among users of the tobacco–cannabis combination known as blunts. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;150:77–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooper ZD, Haney M. Comparison of subjective, pharmacokinetic, and physiologic effects of marijuana smoked as joints and blunts. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;103(3):107–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meier E, Hatsukami DK. A review of the additive health risk of cannabis and tobacco co-use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;166:6–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giovenco DP, Miller Lo EJ, Lewis J, Delnevo CD. “They’re Pretty Much Made for Blunts”: product features that facilitate marijuana use among young adult cigarillo users in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;19(11):1359–1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee JP, Battle RS, Lipton R, Soller B. ‘Smoking’: use of cigarettes, cigars and blunts among Southeast Asian American youth and young adults. Health Educ Res. 2010;25(1):83–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sinclair CF, Foushee HR, Pevear JS, et al. Patterns of blunt use among rural young adult African-American men. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(1):61–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Antognoli E, Cavallo D, Trapl E, et al. Understanding nicotine dependence and addiction among young adults who smoke cigarillos: a qualitative study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018;20(3):377–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lipperman-Kreda S, Lee JP, Morrison C, Freisthler B. Availability of tobacco products associated with use of marijuana cigars (blunts). Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;134:337–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dunlap E, Johnson BD, Benoit E, Sifaneck SJ. Sessions, cypers, and parties:settings for informal social controls of blunt smoking. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2005;4(3-4):43–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malone RE, Yerger V, Pearson C. Cigar risk perceptions in focus groups of urban African American youth. J Subst Abuse. 2001;13(4):549–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.US Food and Drug Administration. Deeming tobacco products to be subject to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, as amended by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act; restrictions on the sale and distribution of tobacco products and required warning statements for tobacco products. Fed Regist. 2016;81(90):28973–29106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soldz S, Huyser D, Dorsey E. Youth preferences for cigar brands: rates of use and characteristics of users. Tob Control. 2003;12(2):155–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jolly DH. Exploring the use of little cigars by students at a historically Black university. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5(3):A82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cullen J, Mowery P, Delnevo C, et al. Seven-year patterns in US cigar use epidemiology among young adults aged 18–25 years: a focus on race/ethnicity and brand. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(10):1955–1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Terchek JJ, Larkin EMG, Male ML, Frank SH. Measuring cigar use in adolescents: inclusion of a brand-specific item. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(7):842–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Corey CG, Ambrose BK, Apelberg BJ, King BA. Flavored tobacco product use among middle and high school students -- United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(38):1066–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delnevo CD, Giovenco DP, Ambrose BK, et al. Preference for flavoured cigar brands among youth, young adults and adults in the USA. Tob Control. 2015;24(4):389–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sterling KL, Fryer CS, Nix M, Fagan P. Appeal and impact of characterizing flavors on young adult small cigar use. Tob Regul Sci. 2015;1:42–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schauer GL, Rosenberry ZR, Peters EN. Marijuana and tobacco co-administration in blunts, spliffs, and mulled cigarettes: a systematic literature review. Addict Behav. 2017;64:200–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lipperman-Kreda S, Lee JP. Boost your high: cigarette smoking to enhance alcohol and drug effects among Southeast Asian American youth. J Drug Issues. 2011;41(4):509–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nasim A, Blank MD, Cobb CO, et al. How to freak a Black & Mild: a multi-study analysis of YouTube videos illustrating cigar product modification. Health Educ Res.2014;29(1):41–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fabian LA, Canlas LL, Potts J, Pickworth WB. Ad lib smoking of Black & Mild cigarillos and cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(3):368–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Powell LM, Chaloupka FJ. Parents, public policy, and youth smoking. J Policy Anal Manage. 2005;24(1):93–112. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Richardson A, Ganz O, Vallone D. The cigar ambassador: how Snoop Dogg uses Instagram to promote tobacco use. Tob Control. 2014;23(1):79–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cavazos-Rehg P, Krauss M, Grucza R, Bierut L. Characterizing the followers and tweets of a marijuana-focused Twitter handle. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(6):e157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cavazos-Rehg PA, Krauss M, Fisher SL, et al. Twitter chatter about marijuana. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56(2):139–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kostygina G, Tran H, Shi Y, et al. ‘Sweeter Than a Swisher’: amount and themes of little cigar and cigarillo content on Twitter. Tob Control. 2016;25(Suppl 1):i75–i82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Montgomery L, Heidelburg K, Robinson C. Characterizing blunt use among Twitter users: racial/ethnic differences in use patterns and characteristics. Subst Use Misuse. 2018;53(3):501–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cavazos-Rehg PA, Krauss MJ, Sowles S, Bierut LJ. Marijuana-related posts on Instagram. Prev Sci. 2016;17(6):710–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Allem JP, Escobedo P, Chu KH, et al. Images of little cigars and cigarillos on Instagram identified by the hashtag #swisher: thematic analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(7):e255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roditis ML, Delucchi K, Chang A, Halpern-Felsher B. Perceptions of social norms and exposure to pro-marijuana messages are associated with adolescent marijuana use. Prev Med. 2016;93(Suppl C):171–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Richardson A, Vallone DM. YouTube: a promotional vehicle for little cigars and cigarillos? Tob Control. 2014;23(1):21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Elkin L, Thomson G, Wilson N. Connecting world youth with tobacco brands: YouTube and the internet policy vacuum on Web 2.0. Tob Control. 2010;19(5):361–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trapl ES, O’Rourke-Suchoff D, Yoder LD, et al. Youth acquisition and situational use of cigars, cigarillos, and little cigars: a cross-sectional study. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(1):e9–e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]