Abstract

Background

Exercise improves balance in Parkinson disease (PD), yet the majority of people with the diagnosis are physically inactive. Insights gained from understanding how people with PD (PwPD) make sense of their symptoms and their ability to control them may inform the communication strategies and motivational approaches adopted by physical therapists. To our knowledge, no previous study has qualitatively explored how PwPD perceive the concept of balance and the beliefs they hold concerning their ability to affect balance.

Objective

This study aimed to explore the meaning of balance for PwPD and the beliefs they hold regarding their ability to influence their balance in everyday life.

Design

The design was a qualitative study with an inductive approach.

Methods

In-depth interviews were conducted with 18 participants with PD (age range 46–83 years, Hoehn and Yahr range 1–4), and transcripts were analyzed using qualitative content analysis.

Results

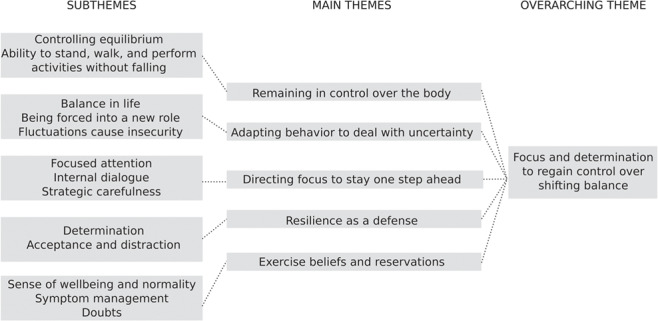

Five main themes emerged from the analysis: remaining in control over the body, adapting behavior to deal with uncertainty, directing focus to stay 1 step ahead, resilience as a defense, and exercise beliefs and reservations. Interpretation of the underlying patterns in the main themes yielded the overarching theme of focus and determination to regain control over shifting balance.

Conclusions

The concept of balance was perceived as both bodily equilibrium and mind-body interplay and was described in the context of remaining in control over one’s body and everyday life. Cognitive resources were utilized to direct focus and attention during balance-challenging situations in a process involving internal dialogue. Even participants who did not express beliefs in their ability to affect balance through exercise used psychological resilience to counter the challenges of impaired balance.

Postural instability is a cardinal feature of Parkinson’s Disease (PD), and although exacerbated by disease progression,1 balance impairments occur at all stages.2 Previous studies describe the ways in which balance impairments negatively affect lifestyle and quality of life among people with PD (PwPD);3,4 however, no study to our knowledge has explored what the concept of balance represents to this group.

Exercise interventions have proven to be successful in improving balance and decreasing fall risk in both the short and long term.5,6 Additionally, a growing body of research highlights the possible role of physical exercise in managing PD by means of neuroprotective mechanisms.7,8 Yet despite these promising research results, studies have shown that even in the early stages of the disease, PwPD do not sustain optimal levels of physical activity.9–11 There could be a number of reasons for this discrepancy; firstly, knowledge of exercise benefits does not necessarily lead to a change in exercise behavior.12 Secondly, for PwPD to engage in exercise as symptom management, they must believe that PD symptoms can be positively influenced.13

PwPD report various disease symptoms, such as depression and fatigue,13,14 and beliefs about symptom management13 as barriers to exercise engagement. To better interpret these barriers, therefore, we firstly need to understand how disease symtpoms are perceived in PwPD. Few previous studies have specifically explored the meaning of balance for PwPD or the beliefs PwPD hold regarding their ability to affect symptoms such as balance impairment. Insights generated from qualitative studies may help therapists to better understand patient perspectives. Acknowledgment of the subjective experience of PD may, in fact, be key to engaging people with the disease in therapy. With this in mind, the aim of this study was to explore the meaning of balance for PwPD and the beliefs they held regarding their ability to influence their balance in everyday life.

Methods

Design and Participants

A qualitative approach was used to describe subjective experiences and perspectives of PwPD. Qualitative inquiries are suitable when wishing to capture human experience.15 Participants were recruited from a health care center in eastern Stockholm, Sweden, and via advertisement at the Parkinson association. The intention was to include participants with different experiences of and viewpoints on balance, and recruitment was therefore based on maximum variation sampling16 with regards to time since diagnosis, sex, age, experience of supervised balance training, current physical activity level, self-perceived balance, use of walking aids, falls in the last year, and fear of falling. Participants were eligible for inclusion if they had a diagnosis of idiopathic PD, scored ≥ 21 on Montreal Cognitive Assessment,17 had a Hoehn & Yahr stage 1 to 4,18 and were able to communicate in Swedish. Nineteen people were assessed for eligibility, whereof 1 was excluded due to a Montreal Cognitive Assessment score below the inclusion cut-off, rendering a total of 18 people (9 women) interviewed (Tab. 1). Participants had a mean age of 69.8 years; mean time since diagnosis was 8.8 years, and Hoehn and Yahr scores ranged from 1 to 4. Self-reported falls during the last year ranged from no falls to once a week; and mean balance performance, as measured with Mini-BESTest, was 18.5 points. Walking aids were used by 8 participants; 6 used a walker outdoors and sometimes indoors, 1 used a cane outdoors, and 1 used a walking frame indoors at night time only. Four participants lived alone, and the remaining 14 lived with a spouse. Ten participants had previous experience with supervised balance training, and self-reported physical activity scores ranged from very inactive to moderately active. The study was approved by the regional ethical board in Stockholm county (2016/1973–32), and all participants signed a written informed consent prior to study inclusion.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Participants (N = 18)

| ID No. | Sex | Age (y) | Years With PD | Falls in Last Year (n) | Hoehn and Yahr a | UPDRS III b | Mini-BESTest c | ABC Scale d (%) | Walk 12 e | PASE f |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female | 70 | 21 | 5 | 3 | 40 | 24 | 60.0 | 15 | 39 |

| 2 | Male | 71 | 10 | 3 | 3 | 46 | 20 | 86.9 | 0 | 118 |

| 3 | Male | 72 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 40 | 16 | 83.1 | 16 | 60 |

| 4 | Male | 80 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 31 | 11 | 73.1 | 25 | 27 |

| 5 | Female | 70 | 10 | 0 | 2 | 14 | - | - | 0 | 64 |

| 6 | Female | 67 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 19 | 24 | 76.3 | 8 | 188 |

| 7 | Female | 83 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 28 | 6 | 16.3 | 17 | 86 |

| 8 | Female | 67 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 16 | 20 | 70.6 | 1 | 50 |

| 9 | Male | 81 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 32 | 17 | 51.9 | 15 | 5 |

| 10 | Male | 70 | 14 | 4 | 3 | 33 | 22 | 64.3 | 19 | 114 |

| 11 | Male | 68 | 21 | 5 | 2 | 32 | 19 | 76.3 | 14 | 37 |

| 12 | Male | 46 | 9 | 2 | 3 | 23 | 19 | 75.6 | 23 | 136 |

| 13 | Female | 73 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 18 | 24 | 63.1 | 25 | 141 |

| 14 | Female | 61 | 3 | 52 | 2 | 22 | 19 | 26.3 | 28 | 67 |

| 15 | Female | 76 | 11 | 0 | 3 | 29 | 16 | 72.5 | 24 | 116 |

| 16 | Male | 73 | 10 | 3 | 4 | 62 | 4 | 16.9 | 38 | 3 |

| 17 | Male | 59 | 13 | 2 | 2 | 24 | 28 | 83.1 | 6 | 214 |

| 18 | Female | 70 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 20 | 25 | 88.8 | 2 | 116 |

| Range | 46–83 | >2–21 | >0–52 | >1–4 | >14–62 | >4–28 | >16.3–88.8 | >0–38 | >3–214 | |

aFive-point disease rating scale, where 1 = minimal or no functional disability and 5 = confinement to bed/wheelchair unless aided.

bUnified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale, part III, motor examination. Score ranges from 0 to 132, where higher scores indicate worse motor function.

cA 14-item clinical test of balance function (maximum score = 28), where higher scores indicate better balance function.

dActivities and Balance Confidence scale, a 16-item self-report questionnaire, where higher scores indicate better self-perceived balance confidence.

eA 12-item self-report questionnaire on walking ability (maximum score = 42), where higher scores indicate worse self-reported walking ability.

fPhysical Activity Scale for the Elderly, self-report questionnaire. Ranges from 0 to 400 points or more. Higher scores indicate higher levels of self-reported physical activity.

Data Collection

Semi-structured interviews were performed by first author H.J. according to an interview guide with predefined themes and open-ended questions (see Appendix 1 for sample interview questions). The interviews were conducted at Karolinska Institutet or in the participants’ home, in accordance with participant wishes, and recorded using a digital Dictaphone (Olympus VN-741PC) and transcribed verbatim. Data collection took place between November 2016 and February 2017, and the average length of the interviews was 51 minutes (range 22–75 minutes). Three interviews were listened to and discussed within the team to evaluate both the interview guide and the interview technique. Some minor changes to the sequencing of the questions were made. In addition to the interviews, a second visit with the participants was conducted to perform clinical testing of balance capacity (Mini-BESTest),19 motor function and disease stage (Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale—motoric subsection), 20 and to collect self-reported questionnaires including Activities-specific Balance Confidence Scale,21 Walk −12,22 and Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly.23 These measures were undertaken as part of a parallel study but are included here to provide a clear picture of the variation in the sample.

Data Analysis

Transcripts were analyzed using content analysis, a valid and reliable method for text analysis, as well as a systematic method of capturing central themes from text.24 After reading each transcript repeatedly, meaning units were identified by author H.J. Authors B.L. and K.S.R. independently identified meaning units from 2 of the transcripts to validate in comparison with author H.J. Initial coding of the meaning units was performed by H.J. in several cycles. During first cycle coding, meaning units were assigned descriptive information codes. Inferential information was assigned using pattern codes during second cycle coding.25 To ensure conformability throughout the analysis, several team debriefing meetings that included all authors were held to discuss coding and categorization as well as development and refinement of the main and overarching themes. Table 2 demonstrates examples of the analytical process from meaning unit to subtheme. Interviews and content analysis were performed in Swedish, after which results and quotations were translated into English.

Table 2.

Example of the Initial Stages of the Analysis Process From Meaning Units to Subthemes

| ID No | Meaning Unit | Code | Subtheme |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | “That is, to keep the body in a controlled state, independent of where you are.” | Controlling your body | Controlling equilibrium |

| 15 | “Yes, well is not that [balance] like you should walk as steadily as possible with both feet on the ground.” | Both feet on the ground | Ability to stand, walk and perform activities without falling |

| 2 | “Spontaneously you think about being able to walk upright and have balance in that way. But then there is balance in life as well.” | Being balanced physically and mentally | Balance in life |

| 14 | “Yes it can vary, in a half an hour maybe I cannot walk, and then it changes back again and then I can be as mobile as ever.” | Fluctuating symptoms | Fluctuations cause unpredictability |

| 16 | ”Otherwise I have not done much, but I am so sick of it, I do not want to do too much either because…Having poor balance, that affects everything. …Yes, everything you do.” | Affects everything you do | Being forced into a new role |

| 9 | “And when you are walking you feel like ‘now this step went alright, and now this step went alright.’ I mean, you probably think faster than that, but that is my experience of it.” | Focusing on 2 step at a time | Focused attention |

| 1 | “I need to think, always think. How should I walk? Because if I walk with small steps, then I lose balance, and need to hang on to my walker.” | Internal dialogue | Internal dialogue |

| 12 | “No I have not fallen yet. But it has been close a few times and…I walk extra carefully when I’m low on medicine. I walk carefully because it’s easy to slip on gravel and stuff.” | Risk assessing | Strategic carefulness |

| 3 | “No, but now you know that your balance is affected. But it’s not like I’m reluctant to do things because my balance is so bad. I do not avoid going into town and such, I mean I have a target when I do things. I am goal oriented.” | Goal oriented | Determination |

| 8 | “That one does not stop, but try and find new ways and try and live as normally as possible. Simply make the best of a bad situation, that’s how I feel. I do not think about it myself, it’s not like I’m feeling sorry for myself like “no no no this is terrible”. It’s the way it is, and I have to live with it.” | Not feeling sorry for myself | Acceptance and distraction |

| 18 | “Because you know it’s [exercising] good for you, and it shows. It has been many years when people who have not met me in a long while have not even understood that I have Parkinson’s disease.” | Sense of normality | Sense of normality and wellbeing |

| 7 | “Yes because when I attended this rehabilitation 3 times a week, I did notice that I improved. And there I wasn’t so afraid of falling, because there was always someone there picking you up quickly.” | Improving balance | Symptom management |

| 10 | “Yes and it seems like everything is ruined, and then it is bloody hard to come back. I’m not…The reason I say no is because I’m not used to failing with these kinds of exercise stuff, but here I have failed to come back.” | Previous failures lead to doubt | Doubts |

Role of the Funding Source

This study was supported by grants from the Doctoral School in Health Care Sciences, the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (FORTE), Parkinson Research Foundation, the Swedish Parkinson Foundation, and the Swedish Research Council. The funders played no role in the design, conduct, or reporting of the study.

Results

The qualitative content analysis resulted in the formation of 13 subthemes and 5 main themes that patterned together to form the overarching theme “Focus and determination to regain control over shifting balance” (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of the analytical process from subthemes to overarching theme.

Remaining in Control Over the Body

The subthemes controlling equilibrium and ability to stand, walk, and perform activities without falling tie together to form this main theme. When asked to describe how they perceived balance, participants described the concept of balance as being related to the ability to control one’s equilibrium.

“To keep the body in an equal weight so that you don’t fall. That must be what balance is, that things are weighted equally in some way, so that you don’t weigh over more to 1 side.” (Participant 6)

This control was described as a combination of automatic and voluntary processes entailing abilities such as coordination of body parts. Having equilibrium was also described in terms of being in an effortless state whereby you could carry yourself freely and not have to think ahead and prepare before challenging movements.

“Balance, that to me is like being able to control your, your body, control your feet, being able to do things freely, walk normally…stopping. Balance to me is a state where my symptoms are fairly perfectly alleviated, where the body is like balanced and walking works and I can lift things. Then I am in balance. Or well, hopefully.” (Participant 12)

When participants were asked to express what it meant for them to have good balance, they talked about it as the opposite of falling, whether it be in standing, walking, or when performing more challenging activities. Good balance was also attributed to a state of normality, whereby movements could be performed “like any normal person”, or where one would not be mistaken for being under the influence of alcohol as could happen when walking unsteadily on a bad day.

“Well, that you can do things like any normal person can do without like losing your balance. That’s the way it is. Like you can stand on 1 leg, be able to run, be able to walk, cycle.” (Participant 17)

Adapting Behavior to Deal With Uncertainty

This theme is composed of the subthemes balance in life; being forced into a new role, and fluctuations cause insecurity. The theme incorporates the participants’ multifaceted lived experiences of balance impairment. The concept of balance was not solely seen as a physical function but was also discussed in relation to mental well-being and the interplay between body and mind.

I’m thinking about a weighing scales, like that you…are in balance…in every way. That things do not weigh too much on 1 side, and in a spiritual way as well.” (Participant 16)

Even though this mind-body interplay was not always explicitly expressed, all participants conveyed a direct or indirect emotional impact of reduced balance capacity. Having an impaired balance capacity often meant having to refrain from, or adapt, one’s activities. No longer being able to perform things one previously could led to a reduced sense of freedom and independence. As a consequence of this, participants were forced into new roles in their management of disease restrictions.

“You lose the freedom to move in the way that you would like to. That must be the biggest freedom that you have, to be able to go where you like.” (Participant 16)

This forced adjustment was further aggravated by the unpredictable nature of PD. Fluctuating symptoms and unpredictable freezing episodes made planning for the short and long term difficult. Being low on medication or being in an “off-state” was described as not only affecting mobility but also their mind and their thought process. It provoked clear negative, emotional responses, even described by 1 person as despair.

“The thing with Parkinson’s is that If I’m in a bad way I can feel complete despair, that I’ll never be able to get up again or that I will never be able to do this thing or that thing. That’s how I think when I’m bad, that things are like totally destroyed for me. And I don’t think about the fact that maybe I will be fine in a half hour, I don’t think that way, It’s like my whole world is decided by the state that I am in that very moment.” (Participant 13)

Directing Focus to Stay One Step Ahead

The subthemes focused attention; internal dialogue and anticipating and planning group together to form this theme. Participants described having to place an increasing amount of conscious effort into dealing with the present moment and, more specifically, performing activities without falling. They were more careful and aware of challenging situations and had begun to implement a sort of strategic carefulness, which could entail staying seated on the bus until it had come to a full stop or walking on the middle of the train platform instead of near the edge.

“Yes exactly, and at the same time, if I walk on a path and meet someone I let them pass in a way that I do not have to step aside, because then I would be afraid that I might fall.” (Participant 6)

While in the moment of performing a certain balance-demanding task, such as walking, participants described having to concentrate on this 1 task with undivided attention.

“Yes I do that, when I walk from the kitchen counter to the sofa I do that. But the thing is that I concentrate on just that one thing that I am doing right then, and then when I sit down, then I relax a little. But I can’t relax while I’m walking.” (Participant 8)

The subtheme internal dialogue concerns how participants pep-talked themselves when faced with environmental demands such as icy streets, stairs, or an oncoming crowd of people. It also entails how they communicated with their body to prepare for and thereafter perform the action in a goal-directed manner.

“And then I can think to myself—think big steps, big steps and then dunce, so that I can sink down. Because otherwise you walk so jerkily, you know, it is that way and your steps shrink, they get smaller and smaller. And when they get smaller and smaller and jerky, then you can fall over, that’s why you have to think that about walking with your legs wide and heavy, you need to walk heavily. Heavy like a mother duck, like really stamp stamp stamp, so you have to think of another way to do it.” (Participant 13)

Resilience as a Defense

The subtheme resilience as a defense incorporates the subthemes determination and acceptance and distraction and describes how various reasoning approaches were used as strategies for living with a declining balance capacity. Determination incorporates how participants did not allow declining balance to stop them from doing activities they wanted to or from spending time with friends and family. It also describes the decision not to “feel sorry” for themselves and a determination to not let PD define who they are.

“I feel confident in a way, like this is me. That you have balance in general in your life as well, It’s like you can focus on your situation, that this is me, That’s not me down there who has fallen, but this is who I am, that’s how I feel.” (Participant 14)

Other strategies and approaches used by participants as a means of coping with the disease are incorporated in the subtheme of acceptance and distraction. Here some participants described distracting their thoughts of the disease by occupying themselves with activities whereas others instead expressed having come to accept the disease and the reduced sense of control it causes.

“Exactly, I feel now that I have accepted the disease and that I am comfortable to be in certain environments where I don’t really have control. And to say how things are if people ask if I need help. So that this leading into things, what you say, the stigmatization that you felt before has gone.” (Participant 12)

Exercise Beliefs and Reservations

This theme contains the subthemes sense of well-being and normality, symptom management, and doubts. The first 2 subthemes deal with the varying motivating factors towards being physically active. Some participants described physical activity as something that enabled them to temporarily take their mind off the disease. Continuing with activities they had previously performed also seemed to reinforce a sense of normality.

“Tennis and jogging and ball sports work pretty well, I mean I don’t think about the fact that I have the disease.” (Participant 12)

An array of activities were described as ways of managing different symptoms such as impaired gait, balance, and posture. Certain participants expressed thoughts on how physical activity could affect the brain and held positive beliefs towards activities that they considered as challenging.

“It’s really good for your brain, it’s like you get reflexes, yes, so it’s great…you have to think like, you have to think strategically when you play table tennis you need to be 1 step ahead in your thoughts when you get the ball, how you are going to place it. It means that you have to think. Think table tennis, and not just hit the ball back, there needs to be thought behind it. And everything needs to happen really fast as well.” (Participant 17)

Not all participants held positive beliefs that physical activity could improve their balance or other symptoms. Some of these participants had tried exercising but were not satisfied with the results, an experience which then resulted in feelings of self-doubt. Whereas some participants expressed beliefs about how the brain had capacity for regeneration, others viewed what happened to the brain as a fixed feature of the disease, as something that lay outside of their conscious control.

“After a failure then the doubt sets in, like this is not going to bloody work…then you start to doubt yourself a bit. I understand that you can influence most things, but of course if it’s the brain that’s gotten a disease, well then it’s not always as easy to make it work.” (Participant 10)

Discussion

There were both unifying and differentiating perceptions among the participants, but balance was mainly described in the context of bodily equilibrium. Participants defined having good balance as being able to remain in control over the body while performing activities. Whereas the concept “good balance” was perceived as involving the ability to stay upright, participants’ perceptions of impaired balance spanned wider concepts and was described as affecting numerous aspects of life emotionally, physically, and socially. In addition to a reduced sense of freedom and independence came the everyday challenges and uncertainties of fluctuating symptoms. Together this resulted in a perceived loss of control in everyday life. To regain control over their shifting balance, participants used determination and directed focus.

Our analysis revealed how participants utilized a process of internal dialogue during balance-demanding tasks. This form of self-talk was adopted as an enabling strategy for people to stay alert while performing the task at hand but also as a process of anticipating and planning for the next step ahead. This finding can be interpreted in relation to the concepts automatic versus goal-directed behavior. With the loss of dopamine in the basal ganglia, automatic movements such as walking become increasingly difficult.26 As a compensational strategy, PwPD exert executive control to perform actions in a goal-directed mode instead, thereby circumventing the stimulus-response habit behavior.27 The act of using conscious control to produce movement, also termed reinvestment, increases over time in PwPD.28 The current study provides first-hand evidence for how PwPD perceive and manage this feature of the disease. This further extends to the dual task paradigm, that is, the act of performing 2 tasks simultaneously. Allocating attention to perform a task increases the complexity of an otherwise seemingly simple task. As therapists, we need to be aware of the level of complexity a task constitutes to a person before we decide on a suitable dual task to either assess or train.

Another recurring theme was the strategy of resilience as a defense used by participants to not allow the disease to constrain their everyday life or stop them from doing desired activities. Resilience signifies the processes by which people adapt to, manage, and bounce back from stressful events in life.29 Originating from developmental psychology in the 1970s, resilience has in the last decades also received increased attention in research on chronic diseases. Robottom et al sought to explore the determinants of resilience in PwPD. They found that less self-rated disability and better physical and mental quality of life, but not disease severity, was correlated with resilience.30 In the current study, the interview questions did not specifically explore the construct of resilience, but adaptational processes emerged during interview analysis in relation to PD symptoms. Interestingly, and in line with the work by Robottom et al, examples of resilience were expressed by participants all across the disease severity span. Expressing resilience was not unique to those who believed they could affect their balance through physical exercise or effort; it was also possible to feel psychologically but not physically resilient against the disease.

A previous study using regression analysis reported that psychological factors, such as self-efficacy, also seem to play a more extensive role than disease severity when it comes to exercise behavior in PwPD.31 The dynamic process of how people initiate and maintain behavior in response to a health threat is described in the Common-Sense Model of Self-Regulation, according to which, the type of coping strategy we use is partly dependent on our beliefs about the consequences of the illness and whether the illness can be cured or controlled.32 Our actions are further motivated by our ability to foresee future events, that is, if we believe that a certain action will lead to a desired result, we are more inclined to initiate it.33 In line with this, participants in the current study with negative experiences of exercise tended to express weaker beliefs in their ability to influence balance. This highlights again the importance of a shared language between caregiver and patient regarding the illness or symptom and also the need to recognize patients’ previous experiences of exercise, as well as their anticipated result, when trying to motivate them.

When analyzing the results of this study, it became clear that the common denominator among the themes was how they represented control. The concept of control appeared to be inherently intertwined with the concept of balance. Participants perceived balance in the sense of controlling their bodies but also described how declining balance led to a lost sense of control in everyday life situations. For some, this also evoked a sense of defiance and determination not to be defined by disease symptoms. Falling, for example, was described by 1 participant as something they did, not something that characterized who they were. Parallels may be drawn to research on perceived control and more specifically to the work done by Rotter in the 1960s. He introduced the term locus of control (LOC) and divided it into either internal, when a person beliefs that an event is contingent on their own actions, or external, when a person thinks that an event instead is contingent on luck, chance, or a powerful other.34 Studies have shown that PwPD have higher external LOC than healthy controls35 and that high internal LOC is associated with less disability.36 This suggests that PwPD believe to a greater extent that their health is controlled by external factors, and with increased disability, they are less likely to believe they can control their health. As physical therapists, we need to be conscious about our patients’ perceived control if we wish to motivate behavior change, because achieving a change in behavior is more likely to occur when symptoms are perceived as controllable.

Throughout the phases of preparing, organizing, and reporting a qualitative content analysis study, there are several factors that may affect trustworthiness.37 In the current study, there are strengths and limitations worth noting. All authors, although now working as researchers, are qualified physical therapists. This may have influenced both the development of the interview guide as well as the interpretation of findings. With this in mind, the interviewer (H.J.) presented herself as a graduate student, not as a physical therapist, in the attempt to minimize possible response bias. The current sample is varied with regards to several relevant demographic and physical performance factors. More importantly, our sampling strategy involved the strategic inclusion of people with no previous experience of organized exercise. This demographic is previously underrepresented in the literature, and we find no existing qualitative study that has explored the beliefs of this group in relation to perceptions of balance. This is a strength with regard to transferability, but the results cannot be considered to represent other patient populations. To increase transparency of the analysis, we aimed to select citations that best mirrored the content of each theme when reporting our results.

In conclusion, among people with PD, balance was a multilayered concept perceived as both physical bodily equilibrium as well as the interplay between body and mind. Balance was often described in the context of control and whether one could control the body in everyday life. People engaged in a multitude of activities where they exerted influence on balance in daily situations. Cognitive resources were utilized to direct focus and attention during everyday balance-challenging situations in a process involving internal dialogue. Even participants who did not express beliefs in the ability to affect balance through exercise described facing the challenges of impaired balance by developing psychological resilience against the disease.

Findings from the current study may have clinical implications for physical therapy treatment of this group. If people with PD perceive balance as a continual act of regaining control over their bodies, perhaps we can adopt concepts of control when encouraging them to initiate new exercise programs. To establish a comprehensive understanding of balance difficulties, we need to pose questions that highlight the extent to which a person uses cognitive resources, such as self-talk, during everyday activities. Becoming more aware of the extent to which PwPD are influencing balance through cognitive or physical adaptations in daily life will enable us to select the most appropriate methods of assessing and challenging this group during physical therapy treatment.

Appendix. Sample Interview Questions

The concept of balance

If you think about the word balance, what does it mean for you?

What does having bad balance involve for you?

What does having good balance involve for you?

Has your view of balance changed since you were diagnosed with Parkinson’s?

How do you consider your balance to be?

In your opinion, what affects your balance?

Can you give an example of situations where your balance is not good?

Can you give an example of situations where you have good balance?

How does your balance affect your ability to do everyday things?

Perceptions on the ability to influence balance

What is your opinion on whether you can influence your own balance?

What are your thoughts on whether balance can be improved through exercise?

What are your thoughts on whether balance can be worsened through exercise?

Is there anything you can think of that would motivate you to train your balance? Can you give some examples?

If you were to give advice to someone whose balance had deteriorated due to Parkinson disease, what would you say?

Is there anything that we have not asked about in relation to balance, falls or training balance which you think is important and would like to discuss?

H. Johansson, PT, MSc, Department of Neurobiology, Care Sciences and Society, Division of Physiotherapy, Karolinska Institutet, Alfred Nobels Allé 23, 141 83 Stockholm, Sweden Address all correspondence to Ms Johansson at: hanna.johansson.1@ki.se.

E. Franzén, PT, PhD, Department of Neurobiology, Care Sciences and Society, Division of Physiotherapy, Karolinska Institutet; Stockholms Sjukhem Foundation, Stockholm, Sweden; and Function Area Occupational Therapy and Physiotherapy, Allied Health Professionals Function, Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden.

K.S. Roaldsen, PT, PhD, Department of Neurobiology, Care Sciences and Society, Division of Physiotherapy, Karolinska Institutet; Sunnaas Rehabilitation Hospital, Oslo, Norway; and Faculty of Health, Oslo Metropolitan University, Oslo, Norway.

M. Hagströmer, PT, PhD, Department of Neurobiology, Care Sciences and Society, Division of Physiotherapy, Karolinska Institutet; Function Area Occupational Therapy and Physiotherapy, Allied Health Professionals Function, Karolinska University Hospital; and Department of Health Promoting Science, Sophiahemmet University, Stockholm, Sweden.

B. Leavy, PT, PhD, Department of Neurobiology, Care Sciences and Society, Division of Physiotherapy, Karolinska Institutet and Stockholms Sjukhem Foundation.

Author Contributions and Acknowledgments

Concept/idea/research design: H. Johansson, E. Franzén, K.S. Roaldsen, M. Hagströmer, B. Leavy

Writing: H. Johansson, E. Franzén, K.S. Roaldsen, B. Leavy, M. Hagströmer

Data collection: H. Johansson

Data analysis: H. Johansson, E. Franzén, K.S. Roaldsen, M. Hagströmer, B. Leavy

Project management: E. Franzén

Fund procurement: E. Franzén

Providing participants: H. Johansson

Providing facilities/equipment: E. Franzén, M. Hagströmer

Providing institutional liaisons: E. Franzén

Consultation (including review of manuscript before submitting): E. Franzén, K.S. Roaldsen, B. Leavy, M. Hagströmer

The authors thank all participants for making this study possible. They also thank Sofie LaGrone, PT, for her help with recruitment and clinical testing of participants.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Doctoral School in Health Care Sciences, the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (FORTE), Parkinson Research Foundation, the Swedish Parkinson Foundation, and the Swedish Research Council.

Disclosure and Presentations

The authors completed the ICJME Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and reported no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

Ethics Approval

The study was approved by the regional ethical board in Stockholm county (2016/1973–32), and all participants signed a written informed consent prior to study inclusion.

References

- 1. Jankovic J. Parkinson's disease: Clinical features and diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:368–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kim SD, Allen NE, Canning CG, Fung VS. Postural instability in patients with Parkinson's disease. Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. CNS Drugs. 2013;27:97–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rahman S, Griffin HJ, Quinn NP, Jahanshahi M. Quality of life in Parkinson's disease: the relative importance of the symptoms. Mov Disord. 2008;23:1428–1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Muslimovic D, Post B, Speelman JD, Schmand B, de Haan RJ. Determinants of disability and quality of life in mild to moderate Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2008;70:2241–2247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shen X, Wong-Yu IS, Mak MK. Effects of exercise on falls, balance, and gait ability in Parkinson's disease: a meta-analysis. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2016;30:512–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mak MK, Wong-Yu IS, Shen X, Chung CL. Long-term effects of exercise and physical therapy in people with Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13:689–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Petzinger GM, Fisher BE, McEwen S, Beeler JA, Walsh JP, Jakowec MW. Exercise-enhanced neuroplasticity targeting motor and cognitive circuitry in Parkinson's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:716–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hirsch MA, van Wegen EEH, Newman MA, Heyn PC. Exercise-induced increase in brain-derived neurotrophic factor in human Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl Neurodegener. 2018;7:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mantri S, Fullard ME, Duda JE, Morley JF. Physical activity in early Parkinson disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 2018;8:107–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lord S, Godfrey A, Galna B, Mhiripiri D, Burn D, Rochester L. Ambulatory activity in incident Parkinson's: more than meets the eye? J Neurol. 2013;260:2964–2972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Benka Wallen M, Franzen E, Nero H, Hagstromer M. Levels and patterns of physical activity and sedentary behavior in elderly people with mild to moderate Parkinson disease. Phys Ther. 2015;95:1135–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kelly MP, Barker M. Why is changing health-related behaviour so difficult? Public Health. 2016;136:109–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ellis T, Boudreau JK, DeAngelis TR et al. Barriers to exercise in people with Parkinson disease. Phys Ther. 2013;93:628–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Afshari M, Yang A, Bega D. Motivators and barriers to exercise in Parkinson's disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 2017;7:703–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 3rd [updated] ed. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: SAGE Publications; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods: integrating Theory and Practice. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: SAGE Publications; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V et al. The Montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hoehn MM, Yahr MD. Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology. 1967;17:427–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Franchignoni F, Horak F, Godi M, Nardone A, Giordano A. Using psychometric techniques to improve the balance evaluation systems test: The mini-BESTest. J Rehabil Med. 2010;42:323–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Movement Disorder Society Task Force on rating scales for Parkinson's disease The unified Parkinson's disease rating scale (UPDRS): status and recommendations. Mov Disord. 2003;18:738–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Powell LE, Myers AM. The activities-specific balance confidence (ABC) scale. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50A:M28–M34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bladh S, Nilsson MH, Hariz GM, Westergren A, Hobart J, Hagell P. Psychometric performance of a generic walking scale (walk-12G) in multiple sclerosis and Parkinson's disease. J Neurol. 2012;259:729–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Washburn RA, Smith KW, Jette AM, Janney CA. The physical activity scale for the elderly (PASE): development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:153–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Krippendorff K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, and London, England: SAGE; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Miles MB. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 3rd ed. Los Angeles, CA, USA: Sage; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Redgrave P, Rodriguez M, Smith Y et al. Goal-directed and habitual control in the basal ganglia: implications for Parkinson's disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:760–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dirnberger G, Jahanshahi M. Executive dysfunction in Parkinson's disease: a review. J Neuropsychol. 2013;7:193–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Masters RS, Pall HS, MacMahon KM, Eves FF. Duration of Parkinson disease is associated with an increased propensity for "reinvestment." Neurorehabil and Neural Repair. 2007;21:123–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Windle G. What is resilience? A review and concept analysis. Rev Clin Gerontol. 2010;21:152–169. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Robottom BJ, Gruber-Baldini AL, Anderson KE et al. What determines resilience in patients with Parkinson's disease? Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012;18:174–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ellis T, Cavanaugh JT, Earhart GM et al. Factors associated with exercise behavior in people with Parkinson disease. Phys Ther. 2011;91:1838–1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Leventhal H, Phillips L, Burns E. The common-sense model of self-regulation (CSM): a dynamic framework for understanding illness self-management. J Behav Med. 2016;39:935–946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organ Beh Hum Decis Process. 1991;50:248–287. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rotter JB. Generalized expectancies for internal vs external control of reinforcement. Psychol Monogr. 1966;80:1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rizza F, Gison A, Bonassi S, Dall'Armi V, Tonto F, Giaquinto S. Locus of control', health-related quality of life, emotional distress and disability in Parkinson's disease. J Health Psychol. 2017;22:844–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gruber-Baldini AL, Ye J, Anderson KE, Shulman LM. Effects of optimism/pessimism and locus of control on disability and quality of life in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2009;15:665–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Elo S, Kääriäinen M, Kanste O, Pölkki T, Utriainen K, Kyngäs H. Qualitative content analysis. SAGE Open. 2014;4:1–10. [Google Scholar]