Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Rates of cardiovascular disease among people with diabetes have declined over the last 20–30 years. To determine whether First Nations people have experienced similar declines, we compared time trends in rates of cardiac event and disease management among First Nations people with diabetes and other people with diabetes in Ontario, Canada.

METHODS:

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients aged 20 to 105 years with diabetes between 1996 and 2015, using linked health administrative databases. Outcomes compared were the annual incidence of each admission to hospital for myocardial infarction and heart failure, and death owing to ischemic heart disease. Management indicators were coronary revascularization and prescription rates for cardioprotective medications. Overall rates and annual percent changes were compared using Poisson regression.

RESULTS:

Incidence rates for all cardiac outcomes decreased over the study period. The greatest relative annual decline among First Nations men and women were observed in ischemic heart disease death (4.4%, 95% confidence interval [CI] 3.0 to 5.9) and heart failure (5.4%, 95% CI 4.5 to 6.4), respectively. Among other men and women, the greatest annual declines were seen in ischemic heart disease death (6.3%, 95% CI 6.1 to 6.5 and 7.3%, 95% CI 7.1 to 7.6, respectively). However, all absolute cardiac event rates were higher among First Nations people (p < 0.001). Coronary artery revascularization procedures and prescriptions for cardioprotective medications increased among First Nations people, while only prescriptions increased among other people.

INTERPRETATION:

Over the last 20 years, the incidence of cardiac events has declined among First Nations people with diabetes, but remains higher than other people with diabetes in Ontario. For continued reductions in incidence, future efforts need to recognize First Nations people’s unique social and cultural determinants of health.

Cardiovascular disease is a major cause of premature morbidity and mortality among people with diabetes, developing 15 years earlier and being associated with poorer prognoses after an event than among individuals without diabetes.1–5 Although high blood glucose is a major independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease, people with diabetes often have other risk factors such as hypertension, dyslipidemia and being overweight, which further increase their cardiovascular risk.6–8 However, over the last 20–30 years, improvements in diabetes management and reductions in the prevalence of, and better care for, co-existing cardiac risk factors have contributed to substantial declines in cardiovascular disease rates and associated morbidity and mortality among people with diabetes.9–11 Despite these gains, people with diabetes remain at higher cardiovascular risk than those without diabetes.

The cardiovascular health of First Nations people, one of 3 major Indigenous populations in Canada, has been particularly affected by high prevalence of diabetes, with onset at young ages, and the early development of related complications.6,12–15 Comorbidities, genetic factors and complex social, cultural and environmental factors also contribute to their increased cardiovascular risk.13,14,16–18 Across Canada, First Nations people are at more than 30% greater risk of dying from cardiovascular disease than other people.19 Communities with high proportions of First Nations people also have higher rates of myocardial infarction and first myocardial infarction at younger ages, and are more likely to have diabetes at the time of a myocardial infarction, than communities with low proportions of First Nations residents.20

Whether initiatives to address high diabetes rates and related complications among First Nations people have affected rates of cardiovascular disease is unknown.21,22 Thus, the objectives of this study were to examine trends in cardiac event rates, particularly myocardial infarction, heart failure and death owing to ischemic heart disease, and indicators of cardiac disease prevention and management among First Nations people with diabetes, compared with other people with diabetes in Ontario, Canada. Findings here and in a related First Nations–specific report of diabetes in Ontario will provide insights into potential areas for improved health care among First Nations people.23

Methods

Study design and population

We conducted a population-based analysis of residents of Ontario, Canada, with diabetes, through linkage of Ontario’s Registered Persons Database to the Ontario Diabetes Database. This study is part of a series examining outcomes related to diabetes mellitus among First Nations people in Ontario; the methods for establishing the study cohort are presented in detail elsewhere.24 The Registered Persons Database is a registry with basic demographic information about all individuals who have ever been eligible for Ontario’s universal health insurance plan. The Ontario Diabetes Database is a registry of all Ontario residents who were identified as having diabetes, created using hospital admission records and physician claims with a reported 86% sensitivity, 97% specificity and 80% positive predictive value against primary care health records.25 The Ontario Diabetes Database does not distinguish between type 1 and type 2 diabetes, but we estimate that more than 90% of individuals have type 2, based on Public Health Agency of Canada reporting from 2011.26

We created annual study cohorts from 1996 to 2015 of individuals aged 20 to 105 years who had been given a diagnosis of diabetes before and were alive on April 1 of each year, and followed each cohort to Mar. 31 of the next year. First Nations people were identified using the Indian Register of all people registered with the Federal government as members of a First Nation recognized under the Indian Act (i.e., all “Status Indians” or “Registered Indians”), regardless of whether they live in a First Nation community (“Indian reserve”).27 People not in the Indian Register, including Inuit and Métis, were classified as “other people.”

Outcomes and data sources

Our primary cardiac outcomes of interest were admissions to hospital for myocardial infarction and heart failure, and deaths owing to ischemic heart disease. Heart failure may have a different pathophysiology than that of ischemic heart disease, but is increasingly recognized as a contributor to morbidity and mortality among people with diabetes, and was thus included.28 Hospital admissions were identified from the Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database, which includes information from the discharge abstracts of all acute-care hospitals in Ontario. Using validated codes from the International Classification of Diseases (Appendix 1, Supplement 1, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.190899/-/DC1), we included all admissions with a main diagnosis of myocardial infarction and heart failure, counting a maximum of 1 admission per individual per study year.29,30 We identified deaths owing to ischemic heart disease from the Office of the Registrar General Vital Statistics database.31

Secondary cardiac outcomes of interest were 30-day and 1-year all-cause mortality after admission to hospital for myocardial infarction, heart failure or unstable angina, and 30-day all-cause readmission rates after hospital discharge for a stay related to myocardial infarction or heart failure. We identified hospital readmission rates from the Discharge Abstract Database and determined all-cause mortality from the Registered Persons Database.

We examined the following cardiac disease prevention and management indicators: rates of coronary artery revascularization procedures, specifically percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass graft surgery; and prescription claims for cardioprotective medications, specifically statins, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), antiplatelet agents (excluding acetylsalicylic acid) and β-blockers. We identified coronary artery revascularization procedures from the Discharge Abstract Database using validated procedure codes (Appendix 1, Supplement 1).32 We captured prescription claims from the Ontario Drug Benefit database, which contains information about claims covered by and made to the Ontario Drug Benefit program for eligible individuals — primarily people in Ontario aged 65 years and older or living in long-term care facilities; hence, indicators for medication use were limited to those aged 65 years and older. Because statins and ACEI or ARBs are recommended for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease in many individuals with diabetes,33,34 we defined these rates as having a prescription claim in the first 100 days (i.e., maximum days’ supply per claim) of the fiscal year among all patients aged 65 years and older. Similarly, because antiplatelet agents and β-blockers are primarily recommended for secondary prevention, 34,35 we defined these rates as having a prescription claim in the 90 days after discharge among patients admitted to hospital for a myocardial infarction, with the number of days chosen to be consistent with quality indicators of care for patients with myocardial infarction. We report results for claims from 2000 onward only, because many of the medications studied have seen more routine use in standard care only since this time.

All data sets were linked using unique, encoded identifiers and analyzed at ICES.

Statistical analysis

Baseline demographics of the study population were calculated as mean ± standard deviation for age, and proportions for categorical characteristics. To account for differences in age and sex between our study populations, overall rates were age- and sex-standardized to the 2001 Ontario census population, while sex-specific rates were age-standardized to the same population using the direct method. Hospital readmission rates were determined in 2-year intervals rather than annually because small absolute numbers of readmissions in some age or sex strata by year would affect the accuracy and reliability of standardized rates.

We compared overall rates for First Nations people with other people using Poisson regression, modelling the expected number of events from the standardized rate as a linear function of year and population, and the natural logarithm of the population size as offset. Where appropriate, we ran separate models for each population to examine relative changes in rates over time, calculating the average annual percent change over the 20-year study period from the incident rate ratio. We determined differences in the average annual percent change between First Nations and other people using similar methods with an interaction term for population and year, and assessed significance by Wald’s χ2 test.

We conducted all analyses using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). All p values are 2-sided.

Ethics approval

This study underwent review and approval by the Chiefs of Ontario’s Data Governance Committee, and the Research Ethics Boards at Queen’s University and Laurentian University.

Results

Table 1 shows baseline demographic characteristics of our study population for 1996, 2006 and 2015. Between 1996 and 2015, the absolute number of people in Ontario aged 20 to 105 years with diabetes increased 183% among First Nations people and 243% for other people. Compared with other people, First Nations people with diabetes were more likely to be female, younger and live in rural communities, and had a similar number of comorbidities.

Table 1:

Demographic characteristics of First Nations people and other people with diabetes, 1996, 2006 and 2015

| Characteristic | No. of First Nations People in Ontario (%)* | No. of other people in Ontario (%)* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| 1996 | 2006 | 2015 | 1996 | 2006 | 2015 | |

| Population size, N | 7758 | 15 580 | 21 989 | 381 202 | 817 866 | 1 309 359 |

|

| ||||||

| Female | 4407 (56.8) | 8591 (55.1) | 11 794 (53.6) | 182 518 (47.9) | 393 578 (48.1) | 629 804 (48.1) |

|

| ||||||

| Age, yr, mean ± SD | 52.38 ± 13.80 | 53.76 ± 13.74 | 56.55 ± 13.83 | 61.68 ± 14.61 | 61.95 ± 14.56 | 63.69 ± 14.31 |

|

| ||||||

| Age group, yr | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 20–49 | 3291 (42.4) | 5951 (38.2) | 6591 (30.0) | 80 006 (21.0) | 166 384 (20.3) | 209 002 (16.0) |

|

| ||||||

| 50–64 | 2954 (38.1) | 6143 (39.4) | 9016 (41.0) | 121 753 (31.9) | 282 052 (34.5) | 450 294 (34.4) |

|

| ||||||

| 65–79 | 1314 (16.9) | 3009 (19.3) | 5372 (24.4) | 141 564 (37.1) | 274 275 (33.5) | 464 356 (35.5) |

|

| ||||||

| ≥ 80 | 199 (2.6) | 477 (3.1) | 1010 (4.6) | 37 879 (9.9) | 95 155 (11.6) | 185 707 (14.2) |

|

| ||||||

| Rurality† | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Urban | 1876 (24.2) | 4190 (26.9) | 6372 (29.0) | 265 405 (69.6) | 587 583 (71.8) | 952 659 (72.8) |

|

| ||||||

| Semi-urban | 1497 (19.3) | 2837 (18.2) | 4127 (18.8) | 77 314 (20.3) | 157 729 (19.3) | 251 030 (19.2) |

|

| ||||||

| Rural | 1758 (22.7) | 3318 (21.3) | 4602 (20.9) | 35 518 (9.3) | 67 365 (8.2) | 98 339 (7.5) |

|

| ||||||

| Remote or missing | 2627 (33.9) | 5235 (33.6) | 6888 (31.3) | 2965 (0.8) | 5189 (0.6) | 7331 (0.6) |

|

| ||||||

| Comorbidities‡ | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Low | 1366 (17.6) | 2931 (18.8) | 4447 (20.2) | 56 891 (14.9) | 130 650 (16.0) | 240 318 (18.4) |

|

| ||||||

| Medium | 3140 (40.5) | 5981 (38.4) | 8573 (39.0) | 167 491 (43.9) | 351 573 (43.0) | 553 556 (42.3) |

|

| ||||||

| High | 3252 (41.9) | 6668 (42.8) | 8969 (40.8) | 156 820 (41.1) | 335 643 (41.0) | 515 485 (39.4) |

Note: SD = standard deviation.

Unless stated otherwise.

Based on the Rurality Index of Ontario, which considers travel time to basic and advanced referral centres.36

Using The Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Groups system version 7 Aggregated Diagnosis Groups scoring system (low = 0–4, medium = 5–9, high = 10+).37

Cardiac outcomes

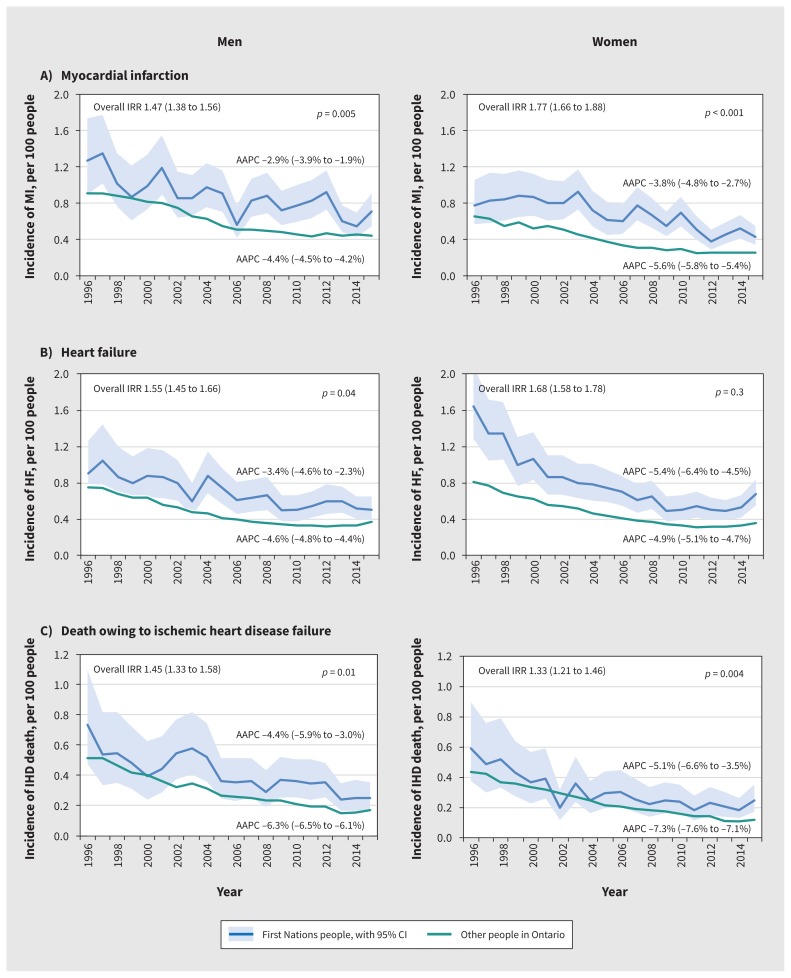

Between Apr. 1, 1996, and Mar. 31, 2016, the incidence of hospital admission for myocardial infarction and heart failure, and deaths owing to ischemic heart disease were all higher among First Nations people than other people (Figure 1, p < 0.001 for all). Over time, a decreasing trend in the age-standardized incidence of myocardial infarction, heart failure and ischemic heart disease death is observed, with annual percent declines among First Nations people less than other people (p < 0.05 for all except heart failure among women [p = 0.3]). The greatest average annual decline among First Nations men and women is seen in deaths owing to ischemic heart disease (4.4%, 95% confidence interval [CI] 3.0 to 5.9) and heart failure (5.4%, 95% CI 4.5 to 6.4), respectively. Among other people, the greatest average annual declines are seen in ischemic heart disease death for both men and women (6.3%, 95% CI 6.1 to 6.5 and 7.3%, 95% CI 7.1 to 7.6, respectively).

Figure 1:

Incidence of (A) hospital admission for myocardial infarction (MI), (B) hospital admission for heart failure (HF), and (C) death owing to ischemic heart disease (IHD), by sex, among people with diabetes in Ontario, Canada, 1996–2016. The overall incidence rate ratio (IRR, 95% confidence interval [CI]) with other people as the reference and average annual percent change (AAPC) (95% CI) are reported for each outcome. P values are for differences in AAPC between First Nations people and other people. Note: blue shading represents 95% CI for the First Nations population.

Of patients admitted to hospital for myocardial infarction, heart failure or unstable angina, First Nations people had similar 30-day and 1-year mortality rates as other people (overall relative rates 1.03, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.16 and 0.98, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.05, respectively), with rates relatively stable in both populations during the study period (Appendix 1, Supplement 2). The average annual 30-day mortality rate (± SD) for First Nations people was 4.5 ± 1.9 per 100 people compared with 4.4 ± 0.6 for other people (p = 0.7); and the average annual 1-year mortality rate was 11.8 ± 2.3 and 12.1 ± 0.7 per 100 people for First Nations and other people in Ontario, respectively (p = 0.7).

Of all patients discharged alive after a hospital admission for myocardial infarction during the study period, 38.5% (958/2489) of First Nations people compared with 33.0% (37 498/113 490) of other people were readmitted for any cause within 30 days (p < 0.001) (Appendix 1, Supplement 3). Of patients discharged after an admission to hospital for heart failure, 33.9% (879/2596) of First Nations people compared with 28.0% (38 942/139 074) of other people were readmitted for any cause within 30 days (p < 0.001). Although rates between 1996 and 2006 for First Nations and other people were not significantly different (myocardial infarction, p = 0.6; heart failure, p = 0.09), rates thereafter were higher among First Nations people, particularly increasing after heart failure (p < 0.001).

Prevention and management of cardiac disease

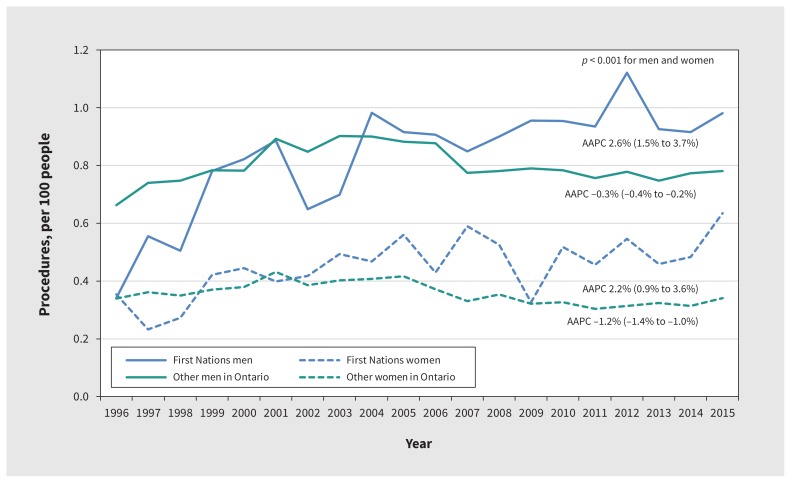

During the study period, coronary artery revascularization rates declined an average of 0.3% (95% CI 0.2 to 0.4) and 1.2% (95% CI 1.0 to 1.4) annually among other men and women, respectively (Figure 2). In comparison, coronary artery revascularization rates for First Nations men almost tripled and for women almost doubled, with average annual percent changes of 2.6% (96% CI 1.5 to 3.7) and 2.2% (95% CI 0.9 to 3.6), respectively (p < 0.001 for difference).

Figure 2:

Incidence of revascularization (percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass graft), by sex, 1996–2016. Average annual percent change (AAPC) (95% confidence interval [CI]) is reported for men and women. P value is for difference in AAPC between First Nations people and other people.

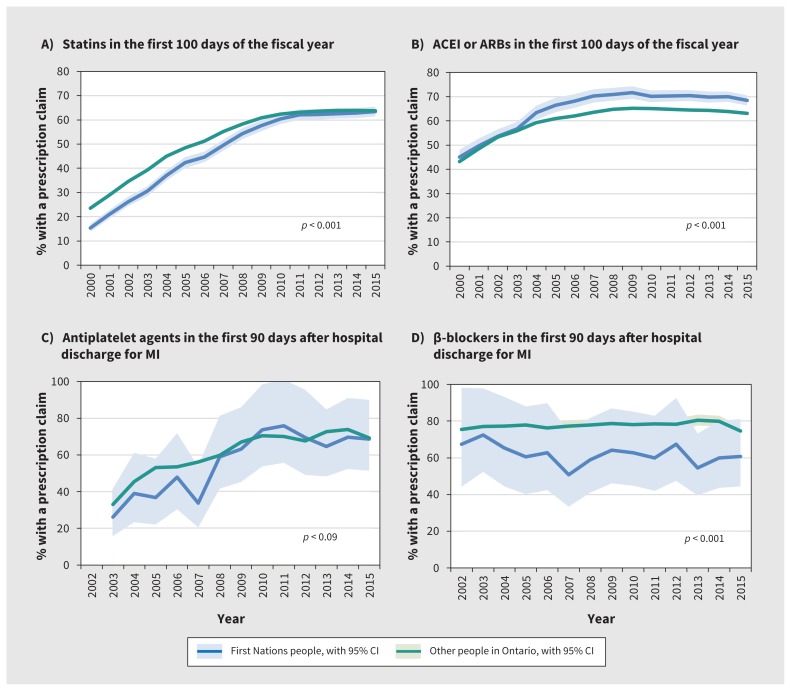

Among all people with diabetes aged 65 years and older, rates of prescription claims for statins or ACEIs or ARBs increased substantially between 2000 and 2016 (Figure 3, p < 0.001). Although overall rates among First Nations people were lower for statins and higher for ACEI or ARBs (p < 0.001) compared with other people, statin rates were similar by 2016. In both populations, rates for both medication types also stabilized in more recent years — at about 65%–70% in 2007 for ACEI or ARBs and at slightly more than 60% in 2011 for statins. Similarly, between 2003 and 2009, prescription claims for antiplatelet agents within 90 days after hospital discharge for myocardial infarction increased considerably, but stabilized thereafter at 65%–70%. Rates of use of β-blockers after hospital discharge for myocardial infarction were relatively unchanged among both First Nations and other people (average annual percent change −0.9%, 95% CI −3.0 to 1.2 and 0.2%, 95% CI −0.1 to 0.4, respectively), but over the study period, First Nations people showed consistently lower rates of prescription claims (p < 0.001).

Figure 3:

Prescription rates for (A) statins and (B) angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) or angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARBs) in the first 100 days of the fiscal year, and (C) antiplatelet agents and (D) β-blockers after hospital discharge for myocardial infarction (MI) among people aged 65 years and older, 2000–2016. Results for antiplatelet agents are shown for 2003 and later, and β-blockers for 2002 and later because these medications have seen more routine use in standard care only after this time. P values are for differences in the overall relative rates between First Nations people and other people. Note: blue shading represents 95% CI for the First Nations population; green shading represents 95% CI for other people.

Interpretation

Among both First Nations people and other people with diabetes in Ontario, we found that, between 1996 and 2016, the incidence of admissions to hospital for myocardial infarction and heart failure and deaths owing to ischemic heart disease decreased, with incidence remaining higher among First Nations people. However, mortality rates among those admitted to hospital were similar and relatively unchanged. In addition, during this period, coronary artery revascularization rates and the use of cardioprotective medications among First Nations people increased substantially.

Although our finding of higher cardiac event rates among First Nations people is consistent with those of previous studies, the observed decreasing rates over time contrasts with earlier Canadian studies showing increasing rates of cardiovascular disease among First Nations people in general, suggesting that progress has been made in the management of diabetes and other cardiac risk factors in this population.17,19,20,38 In addition to increased use of coronary artery revascularization procedures and pharmacotherapies for prevention of cardiovascular disease, another study found First Nations people to have more intensive glucose-lowering medication regimens, albeit with poorer glycemic control (unpublished data, 2019). In another pan-Canadian study, residents of communities with a high proportion of First Nations people were less likely to undergo angiography or percutaneous coronary intervention during an admission to hospital for myocardial infarction than residents of other communities, although in-hospital mortality rates were similar.20 Our results may differ because we studied a population with diabetes and did not restrict to care provided during the hospital admission for myocardial infarction, providing broader insights into preventive care.

Despite these gains, our findings show that First Nations people have higher diabetes complication rates than other people, particularly hospital readmissions. This suggests that current approaches and services are insufficient to close the gap. Higher hospital readmission rates in recent years may be explained by more severe ischemic heart disease and higher rates of other micro- and macrovascular disease that potentially increase the risk of readmission.6,16,22,39 Gaps in postdischarge management resulting from poor access to primary care physicians in communities with high proportions of First Nations people may also contribute to high readmission rates, as access to primary health care in the community (e.g., at nursing stations) has been associated with lower levels of avoidable hospital admissions for ambulatory care–sensitive conditions.40,41 First Nations people face not only structural barriers to optimal care such as limited access to physicians and continuity of care to facilitate timely follow-up after discharge, but also the ongoing effects of colonization, food insecurity, health care inequities, negative interactions with health care providers and genetic factors.18,22,42–44 Further investigations are required to better understand potential causal factors that could reduce readmission rates, as well as to examine interventions that are effective in preventing and managing cardiac risk factors and cardiovascular disease.

The strengths of this study include the population-based study cohort of people in Ontario with diabetes, and the ability to link to 20 years of health administrative data to examine trends over time.

Limitations

We acknowledge the following limitations. Although our study population includes nearly all adults in Ontario, low absolute outcome counts among First Nations people contributed to unstable rates over time for many indicators and precluded the ability to study outcomes across subgroups. Because First Nations people living in versus outside of First Nations communities, as well as those in rural versus urban communities, have a higher prevalence of diabetes and face different determinants of health, it is possible that trends in outcomes may be different in these subpopulations (unpublished data, 2019).22,23 Additionally, we report rates that are age- and sex-standardized to a census population that is younger and healthier. Thus, caution should be taken in interpreting the reported rates, which may underestimate the absolute impact of diabetes. Because this study focused on diabetes, we also did not examine the influence of other comorbidities on differences in outcomes between First Nations people and other people, although First Nations people have a higher prevalence of other cardiac risk factors, which likely contributes to their greater risk.16,45

Conclusion

This study provides new insights into patterns of cardiovascular health and related care of First Nations people with diabetes in Ontario. While progress is being made overall in diabetes management and reducing cardiac events and mortality, First Nations people with diabetes remain at greater risk of cardiovascular disease and complications than other people in Ontario. Efforts to further close the gap in cardiovascular risk will require emphasis on early prevention strategies that not only include Western medical therapies, but must also account for the complex context of the health of First Nations people in Canada and address their unique social and cultural determinants of health.

Acknowledgements

Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by the Ontario MOHLTC and Canadian Institute for Health Information. The analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not reflect those of the funding or data sources; no endorsement is intended or should be inferred. The authors thank Jiming Fang for his assistance in this study’s data analysis, and IMS Brogan Inc. for use of its Drug Information Database; information from this database is linked with the Ontario Drug Benefits database. This manuscript is dedicated to Jack Tu, who passed away prior to its completion.

See related article at www.cmajopen.ca/lookup/doi/10.9778/cmajo.20190096

Footnotes

Competing interests: Michael Green received grant funding from the Ontario Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR) Support Unit, which is jointly funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Province of Ontario specific to this work. Dr. Green receives grant funding for other related work from both CIHR and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). Dr. Green has received funding from Health Canada’s First Nations and Inuit Health Branch for consulting work related to the application of Jordan’s Principle in Ontario. Jack Tu and Douglas Lee received a grant from CIHR, during the conduct of the study. No other competing interests were declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: All of the authors contributed to the conception and design of the study. Lu Han, Shahriar Khan and Anna Chu acquired the data and performed the data analyses. All of the authors interpreted the results. Anna Chu drafted the manuscript, and all of the authors revised it critically for important intellectual content, approved the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This study was funded by a CIHR foundation grant (FDN-143313) to Jack Tu, an IMPACT Award from the Ontario SPOR SUPPORT Unit and the Brian Hennen Chair in Family Medicine held by Michael Green. The study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario MOHLTC. Idan Roifman is supported by National New Investigator and Ontario Clinician Scientist Awards from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. Douglas Lee is the Ted Rogers Chair in Heart Function Outcomes and is supported by a Mid-career award from the Heart and Stroke Foundation. Jennifer Walker is supported by a Tier 2 Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Health. Jack Tu was supported by a Canada Research Chair in Health Services Research and an Eaton Scholar award from the Department of Medicine at the University of Toronto.

Data sharing: The data used in this study are held at ICES, and are not available for sharing from the authors. Contact ICES (www.ices.on.ca) for more information.

Disclaimer: This study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario MOHLTC. The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred.

References

- 1.Aguilar D, Solomon SD, Køber L, et al. Newly diagnosed and previously known diabetes mellitus and 1-year outcomes of acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2004;110:1572–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Booth GL, Kapral MK, Fung K, et al. Relation between age and cardiovascular disease in men and women with diabetes compared with non-diabetic people: a population-based retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2006;368:29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dauriz M, Mantovani A, Bonapace S, et al. Prognostic impact of diabetes on long-term survival outcomes in patients with heart failure: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2017;40:1597–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Einarson TR, Acs A, Ludwig C, et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes: a systematic literature review of scientific evidence from across the world in 2007–2017. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2018;17:83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haffner SM, Lehto S, Rönnemaa T, et al. Mortality from coronary heart disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes and in nondiabetic subjects with and without prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1998;339:229–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris SB, Naqshbandi M, Bhattacharyya O, et al. Major gaps in diabetes clinical care among Canada’s First Nations: results of the CIRCLE study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2011;92:272–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kannel WB, McGee DL. Diabetes and glucose tolerance as risk factors for cardiovascular disease: the Framingham study. Diabetes Care 1979;2:120–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Preis SR, Pencina MJ, Hwang S-J, et al. Trends in cardiovascular disease risk factors in individuals with and without diabetes mellitus in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2009;120:212–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gregg EW, Li Y, Wang J, et al. Changes in diabetes-related complications in the United States, 1990–2010. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1514–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imperatore G, Cadwell BL, Geiss L, et al. Thirty-year trends in cardiovascular risk factor levels among US adults with diabetes: National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 1971–2000. Am J Epidemiol 2004;160:531–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stark Casagrande S, Fradkin JE, Saydah SH, et al. The prevalence of meeting A1C, blood pressure, and LDL goals among people with diabetes, 1988–2010. Diabetes Care 2013;36:2271–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dannenbaum D, Kuzmina E, Lejeune P, et al. Prevalence of diabetes and diabetes-related complications in First Nations communities in Northern Quebec (Eeyou Istchee), Canada. Can J Diabetes 2008;32:46–52. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dyck R, Osgood N, Lin TH, et al. Epidemiology of diabetes mellitus among First Nations and non-First Nations adults. CMAJ 2010;182:249–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gracey M, King M. Indigenous health part 1: determinants and disease patterns. Lancet 2009;374:65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanley AJG, Harris SB, Mamakeesick M, et al. Complications of type 2 diabetes among Aboriginal Canadians. Diabetes Care 2005;28:2054–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anand SS, Yusuf S, Jacobs R, et al. Risk factors, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular disease among Aboriginal people in Canada: the Study of Health Assessment and Risk Evaluation in Aboriginal Peoples (SHARE-AP). Lancet 2001;358:1147–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris SB, Zinman B, Hanley A, et al. The impact of diabetes on cardiovascular risk factors and outcomes in a native Canadian population. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2002;55:165–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacklin KM, Henderson RI, Green ME, et al. Health care experiences of Indigenous people living with type 2 diabetes in Canada. CMAJ 2017;189:E106–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tjepkema M, Wilkins R, Goedhuis N, et al. Cardiovascular disease mortality among First Nations people in Canada, 1991–2001. Chronic Dis Inj Can 2012;32: 200–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hospital care for heart attacks among First Nations, Inuit and Métis. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aboriginal diabetes initiative program framework 2010–2015. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2011. Cat no H34-156/2011E. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crowshoe L, Dannenbaum D, Green M, et al. Diabetes Canada 2018 clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of diabetes in Canada: type 2 diabetes and Indigenous Peoples. Can J Diabetes 2018;42:S296–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green ME, Jones CR, Walker JD, et al. First Nations and Diabetes in Ontario. Toronto: ICES; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slater M, Green ME, Shah B, et al. First Nations people with diabetes in Ontario: methods for a longitudinal population-based cohort study. CMAJ Open. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hux JE, Ivis F, Flintoft V, et al. Diabetes in Ontario: determination of prevalence and incidence using a validated administrative data algorithm. Diabetes Care 2002;25:512–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diabetes in Canada: facts and figures from a public health perspective. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Indian Act, R.S.C., 1985, c I-5.

- 28.Connelly KA, Gilbert RE, Liu P. Diabetes Canada 2018 clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of diabetes in Canada: treatment of diabetes in people with heart failure. Can J Diabetes 2018;42(Suppl 1):S196–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Austin PC, Daly PA, Tu JV. A multicenter study of the coding accuracy of hospital discharge administrative data for patients admitted to cardiac care units in Ontario. Am Heart J 2002;144:290–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tu JV, Donovan LR, Lee DS, et al. Effectiveness of public report cards for improving the quality of cardiac care: the EFFECT study: a randomized trial. JAMA 2009;302:2330–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geran L, Tully P, Wood P, et al. Comparability of ICD-9 and ICD-10 for mortality statistics in Canada. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2005. Cat no. 84-584-XIE; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee DS, Stitt A, Wang X, et al. Administrative hospitalization database validation of cardiac procedure codes. Med Care 2013;51:e22–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anderson TJ, Gregoire J, Pearson GJ, et al. 2016 Canadian Cardiovascular Society guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in the adult. Can J Cardiol 2016;32:1263–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stone JA, Houlden RL, Lin P, et al. Cardiovascular protection in people with diabetes. Can J Diabetes 2018;42(Suppl 1):S162–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tu JV, Khalid L, Donovan LR, et al. Indicators of quality of care for patients with acute myocardial infarction. CMAJ 2008;179:909–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kralj B. Measuring rurality — RIO2008 BASIC: methodology and results. Toronto: Ontario Medical Association; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 37.The Johns Hopkins ACG Case-Mix System Reference Manual Version 7.0. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shah BR, Hux JE, Zinman B. Increasing rates of ischemic heart disease in the native population of Ontario, Canada. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:1862–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dyck RF, Osgood ND, Lin TH, et al. End stage renal disease among people with diabetes: a comparison of First Nations people and other Saskatchewan residents from 1981 to 2005. Can J Diabetes 2010;34:324–33. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Health Quality Ontario. Health in the North: a report on geography and the health of people in Ontario’s two northern regions. Toronto: Queen’s Printer for Ontario; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lavoie JG, Forget EL, Prakash T, et al. Have investments in on-reserve health services and initiatives promoting community control improved First Nations’ health in Manitoba? Soc Sci Med 2010;71:717–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allan B, Smylie J. First Peoples, second class treatment: the role of racism in the health and well-being of Indigenous peoples in Canada. Toronto: Wellesley Institute; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reading J. Confronting the growing crisis of cardiovascular disease and heart health among Aboriginal peoples in Canada. Can J Cardiol 2015;31: 1077–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sherifali D, Shea N, Brooks S. Exploring the experiences of urban First Nations people living with or caring for someone with type 2 diabetes. Can J Diabetes 2012;36:175–80. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oster RT, Toth EL. Differences in the prevalence of diabetes risk-factors among First Nation, Métis and non-Aboriginal adults attending screening clinics in rural Alberta, Canada. Rural Remote Health 2009;9:1170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]