Abstract

This article explores the relationship between the 2014–2016 Ebola outbreak and the political economy of diamond mining in Kono District, Sierra Leone. The authors argue that foreign companies have recycled colonial strategies of indirect rule to facilitate the illicit flow of resources out of Sierra Leone. Drawing on field research conducted during the outbreak and in its aftermath, they show how this ‘indirect rule redux’ undermines democratic governance and the development of revenue-generation institutions. Finally, they consider the linkages between indirect rule and the Ebola outbreak, vis-à-vis the consequences of the region’s intentionally underdeveloped health care infrastructure and the scaffolding of outbreak containment onto the paramount chieftaincy system.

Keywords: Ebola, Sierra Leone, diamonds, neocolonialism, indirect rule, illicit financial flows

Abstract

Cet article explore la relation entre l’épidémie d’Ebola de 2014–2016 et la politique économique de l’extraction de diamants dans le district de Kono, au Sierra Leone. Les auteurs avancent que des entreprises étrangères ont recyclé les stratégies coloniales de la « règle indirecte » afin de faciliter le flux de ressources hors du Sierra Leone. S’appuyant sur de la recherche de terrain conduite pendant l’épidémie et après, il est démontré comment ce retour de la « règle indirecte » sape la gouvernance démocratique et le développement d’institutions qui génèrent du revenu. Enfin, cet article s’intéresse aux liens entre la « règle indirecte » et l’épidémie d’Ebola, vis-à-vis des conséquences de l’infrastructure de soins de santé intentionnellement sous-développée dans la région et les tentatives de confinement de l’épidémie pour le système essentiel de chefferie.

Keywords: Ebola, Sierra Leone, diamants, néocolonialisme, règle indirecte, flux financiers illicites

Introduction

In this article we explore the relationship between the 2014–2016 Ebola outbreak and the political economy of diamond mining in Kono District, Eastern Sierra Leone. In particular, we argue that neo-colonial strategies of indirect rule are deployed by foreign mining companies to facilitate the flow of resources out of Sierra Leone. This ‘indirect rule redux’ undermines democratic governance and the development of regulatory and revenue-generation institutions, which ultimately contributes to Sierra Leone’s political, social and healthcare underdevelopment.

We consider ‘indirect rule’ a useful analytic in describing a number of different machinations of political-economic subjugation that arise from extractive industries in Sierra Leone and which together serve to predispose vast swathes of the country to catastrophic public health events. Despite being first deployed and defined by British colonial authorities in the late 19th century, the term is now infrequently used within Sierra Leonean political discourse or among development technocrats. Indeed, as we will describe below, the trappings of indigeneity surrounding the paramount chieftaincy constitute a potent ‘anti-politics machine’ that often veils systematic structures of marginalisation and oppression at work (Ferguson 1994).

When we use the concept indirect rule, we are referring to strategies deployed by foreign entities (historically the British colonial government, currently corporate actors) seeking access to Sierra Leonean resources that meet four criteria: 1) They cultivate and empower an elite group of Sierra Leonean nationals in powerful political positions within and parallel to the national government who are more beholden to foreign extractive entities than their constituents and thus; 2) grant unfettered access to resources for foreign entities, even if that involves reclaiming and displacing indigenous communities; 3) intentionally undermine the development of regulatory institutions in order to grant a small, elite class the authority to broker access to mineral resources; and, related, 4) facilitate illicit financial flows by circumventing national revenue-generation institutions, thus undermining the provision of public goods and contributing to the country’s health, social and economic underdevelopment.

In order to demonstrate the relationship between indirect rule and the Ebola outbreak, we will first recount the historical context in which the Sierra Leonean paramount chieftaincy was established by British colonial authorities, and how this system of undemocratic rule has been entangled with extractive industries since its inception. Then, we will draw on two case studies – that of a major international corporate mine, and that of a small-scale foreign diamond magnate – to illuminate how indirect rule enables unfettered access to diamondiferous land for foreign entities, intentionally undermines the development of national and international regulatory institutions and enables the widespread evasion of mandated taxes that could be used to develop a more robust and capable national health system. Finally, we offer an initial analysis of the linkages between contemporary indirect rule and the 2014–2016 Ebola virus in Kono District, Sierra Leone, vis-à-vis the consequences of the region’s intentionally underdeveloped healthcare system and the scaffolding of the public health response onto the paramount chieftaincy system.

Methods

Our analysis is informed by a concern with the links among health, history, political economy and crisis response, and shaped by extensive fieldwork in Sierra Leone. We conducted six weeks of intensive ethnographic fieldwork in Kono District, which included participant observation and extended interviews with Ebola survivors and individuals affiliated with the mining industry. Our work is also informed by our experience as clinicians and researchers working in the region since 2003, including five months of ‘observant participation’ (to borrow from Fassin and Rechtman [2009]) as health workers during the 2014–2016 Ebola outbreak. As the centre of the country’s diamond mining economy, Kono serves as a useful case study for conducting an analysis of contemporary practices of indirect rule and its relations to the region’s underdeveloped healthcare system. This granular focus also unveils the ways in which such political-economic systems affect the spread and response to infectious diseases across other communities governed by indirect rule, as these practices are not restricted to the far east of Sierra Leone.

Background

Kono District, Sierra Leone

Kono District has long been known for having some of the richest diamond deposits in the world. It has thus been a nexus for political tensions, labour migration, and foreign extractive activity since the British learned of the deposits in the early 1930s (Zack-Williams 1990). In the subsequent decades, the region became entangled in battles over nationalising foreign-controlled mining operations, international criminal trade networks extending to the Middle East and Europe, and illicit diamond smuggling (Frost 2012). In the 1990s, Kono was an ‘epicentre’ of the country’s 11-year civil war as competing factions fought for control over the district’s rich mineral deposits. Since then, it has been one of the most politically contentious districts in the country, swinging wildly – and sometimes violently – back and forth between the All People’s Congress party and the current ruling Sierra Leone People’s Party.

Alongside the enormous wealth that has been extracted from the region, extreme poverty is ubiquitous. Despite development aid, an effort at political decentralisation through transfer of key functions from the central government to local councils and a sizeable international non-governmental organisation (NGO) sector, the district’s healthcare system has remained ineffectual. Across the country, life expectancy and maternal mortality rates are among the worst in the world, malnutrition is rampant, and most young adults are thrust into tenuous lives of petty-trading, small-scale agricultural work, and, in Kono, alluvial mining (World Health Organization n.d.; United Nations World Food Programme 2011). Kono has some of the country’s highest rates of HIV and TB, probably due to the mining industry via migration and occupational health hazards. Before the 2014–2016 West African Ebola outbreak – which led to the deaths of over 240 people in Kono and nearly 400 cases – the district had just three doctors to care for 550,000 people.

Indirect rule: origins and strategies

In his 1922 book, The dual mandate, British colonial strategist Lord Frederick Lugard articulated his strategy for indirect rule across British colonial Africa, a system of governance that would simultaneously control and marginalise the populace but also enable resource extraction by a foreign, colonising entity. He wrote:

There are not two sets of rulers – British and native – working either separately or in co-operation, but a single government in which the native chiefs have well-defined duties and an acknowledged status equally with British officials. They should be complementary to each other, and the Chief himself must understand that he has no right to place and power unless he renders his proper services to the [colonial] State. (Lugard 1922, 203, emphasis added)

Across its West African colonies, British would identify and institutionalise an indigenous elite, cultivate relationships between colonial authorities and local rulers to maintain authority and access to resources within the region, and empower local chiefs as the ‘direct’ enforcers of day-to-day colonial laws, taxation and land distribution.

In 1896, Britain expanded its presence in what is today known as Sierra Leone beyond Freetown – a city ‘founded’ in 1792 by British abolitionists and freed slaves who had been previously resettled in Nova Scotia, Jamaican Maroons, and poor black individuals from London (later known as ‘Krios’) (Walker 1992) – and established indirect rule in the rural periphery (the ‘Sierra Leone Protectorate’) outside the city. Unlike other British protectorates such as those in parts of today’s Ghana and Uganda, there had been no stable, pre-colonial state or centralised system of governance on which to scaffold a new system of indirect rule (Richards 2005; Acemoglu et al. 2014).1 Paul Richards (2005) notes that throughout the 19th century, the area that would become the Sierra Leone Protectorate had been ruled by warrior-chiefs who had amassed wealth and power by deploying large armies of warrior-slaves as mercenaries for coastal mercantile chiefs engaged in the Transatlantic slave trade. Though elite rule and brutality in West Africa certainly existed independently of European traders arriving in search of slaves, the entire cultural and political order of the region in the 19th century was characterised by inter-clan violence and predation provoked by and deeply entangled with the slave trade (Shaw 2002). From 1896 on, when the British government formally established the Protectorate, these warlords were dubbed ‘paramount chiefs’ and, as Richards writes, ‘this froze in place the practices and privileges of the 19th century forest warrior chiefs’ (Richards 2005, 582). Thus, with the establishment of the Protectorate, the hinterland warrior-chiefs who had long been engaged in the exchange of bodies and goods with European traders were made into components of a formally subservient and extractive political system.

The British divided the Protectorate into a series of chiefdoms, each governed by a paramount chief, and these rulers were given the authority to enforce local and colonially mandated laws, operate local judicial systems, levy taxes, mandate labour and, perhaps most important, distribute and charge rent for the land in their chiefdoms.2 Though Lugard and others did contend that one of the two ‘dual mandates’ in British Africa was ‘civilising’ the native populations, the British subsequently invested very little in the development of education, healthcare or political systems in the rural hinterlands, even compared to neighbouring colonies (Cartwright 1970). The fact that, from the founding of the Protectorate, the human development of the region was deemed unimportant exposes the fact that indirect rule in Sierra Leone has always been fundamentally a system of economic extraction.

Although the colonial authorities selected the initial paramount chiefs based on their loyalty to the colonial government and wealth (Abraham 1978, 239), the British worked to stoke an appearance of tribal indigeneity surrounding the role of paramount chiefs that has endured to this day (Cartwright 1970; Corby 1990, 322). This was seen, in part, through the British positioning paramount chiefs as nominal figureheads for the rights of Protectorate inhabitants (particularly in conflicts between the Krios and tribal indigenes in the early 20th century) while simultaneously cultivating them as a largely anti-radical and pro-British bloc that would maintain order in and access to the countryside.

Though many former colonies reformed their systems of indirect rule through independence – Ghana and Uganda among them – Sierra Leone has largely maintained the selection process, roles and authorities of paramount chiefs. Indirect rule was reaffirmed in the 2009 Chieftaincy Act that notes ‘a recognised ruling house [a family eligible for chieftaincy] is one that has been established and in existence as such at independence on 27 April 1961 [the date of independence]’ (Republic of Sierra Leone 2009). As an indication of just how much this ‘customary’ political system continues to rely on its colonial origins, one man in Kono, who believed his family had the right to the chieftaincy, told us that the family was not recognised as a ‘ruling house’ until one member recently found a line in a colonial archive in which a British officer had noted that the man’s ancestor was a ‘wealthy and important man’. In this system, wealth and historical proximity to colonial overlords translate into the right to rule.

Paramount chiefs and the political economy of diamond mining

Despite democratisation efforts in Sierra Leone, paramount chiefs maintain an enormous amount of political clout. Chiefs continue to levy local taxes, maintain influence over local courts, and serve as key conduits through which elites lay claim to resources in the rural peripheries, thus rendering them ‘internal colonies’ (Zack-Williams 1990). As ‘custodians of the land’ (as they are called colloquially), the paramount chiefs, with an elaborate system of sub-chiefs beneath them, are the formal owners of nearly all land in Sierra Leone and thus have almost unilateral control over the distribution, management and even reclamation of utilised surface land.

This is most important in minerally rich regions of the country, such as Kono, in which the paramount chiefs’ authority is evident through their brokering access to mining areas. Since the 1930s, when the British learned of the country’s rich diamond deposits, paramount chiefs have been entangled in the industry and efforts to maintain preferential access for foreign players. While the British Sierra Leone Selection Trust (SLST) maintained an absolute monopoly on the right to mine in the country through the 1950s, paramount chiefs served as gatekeepers for wealthy Freetown elites, Middle Easterners, and other foreigners to access illicit mining sites within their chiefdoms. As limited areas of Sierra Leone were opened up to small-scale mining through independence and into the later part of the 20th century, and increasingly large numbers of young men migrated to diamondiferous regions in search of work and wealth, paramount chiefs continued to broker access to chiefdom-owned concessions as well as illicit mining sites owned by the SLST-managed National Diamond Mining Company (NDMC) (Harbottle 1976). Paramount chiefs used their state-sanctioned elite status to enrich themselves via illicit mining activities that circumvented official authorisation, in a sense foreshadowing the ways in which national regulations surrounding mining are now evaded via foreign corporations’ proximity to paramount chiefs.

In the fragmented landscape of the diamond industry after the NDMC’s withdrawal during the country’s civil war, the paramount chieftaincy is arguably the primary way in which competing artisanal, small-scale, foreign and industrial-scale actors access land and mining concessions today. Significant efforts have gone into developing centralised regulatory systems to monitor mining activities and to trace stones set for export (as a result of international agreements like the Kimberley Process and with support from international consultants and development agencies, see, e.g., Smillie, Lansana, and Hazleton 2000). And yet these systems are easily circumvented via foreign actors’ strategic relationships to more local elites who serve as the direct gatekeepers to mining areas. In what follows, we analyse the how the paramount chieftaincy continues to be such a durable institution, and its effects on the country’s political, social and healthcare underdevelopment.

Case studies: contemporary indirect rule

Indirect rule and land reclamation

In this section, we consider the use of indirect rule by a large, international corporate actor as a strategy to reclaim massive amounts of inhabited diamondiferous land in Kono District. In so doing, we reveal the entangled and visible relations that emerge between foreign mining actors and paramount chiefs as the on-the-ground ‘gatekeepers’ to mining areas. These strategic partnerships have great resonance with colonial-era efforts to politically pacify the rural populace enabling unfettered access to natural resources for foreign entities.

Koidu Holdings is the major mechanised diamond mine in Kono and since its establishment has been operated by former South African mercenaries who fought in the Sierra Leone civil war with the company Executive Outcomes (Manson 2013). Koidu Holdings is now heavily financed by Tiffany and wholly owned through a subsidiary, Octea Limited, by Benny Steinmetz Group Resources (operated by the Israeli diamond magnate Benny Steinmetz, who, at the time of this writing, is under investigation for massive corruption schemes to gain access to an iron mine in neighbouring Guinea) (Keefe 2013). Koidu Holdings has placed the local paramount chief as a non-voting member on its board of directors, which the chief openly acknowledges comes with a monthly salary linked to the financial success of the mine (The Association of Journalists on Mining and Extractives 2009). Harnessing the chief’s lawful authority to reclaim (forcibly) inhabited surface land, the mine has embarked on a massive expansion project that has displaced thousands of people who have been subsequently moved to a large muddy flat on the outskirts of Koidu City overshadowed by the mine’s tailing dump colloquially, and indignantly, called ‘Resettlement’.

Over the last nine years, significant tensions have emerged between the mine’s administration, affected community members and the paramount chief who serves as an intermediary between the two. Early conflicts centred around the inadequate building materials used in the resettlement houses. Then, conflicts arose about the company’s refusal to pay people who were being resettled for their farmland and crops that were lost in the process. Eventually, an Affected Property Owners Association was successful in requiring that all repossessed land be visited by an assessor. But the lump-sum payments that were provided, at rates sanctioned by the paramount chief, often frustrated villagers given that decades-old cacao and coffee groves, which would have borne fruit for years to come, were simply bought out at a flat rate. Farmers were often not given significant land to utilise after being resettled into concrete row-houses. The expansion process has thrust thousands of people from lives of tenuous agrarian existence to abject, peri-urban poverty. The most common complaint voiced in our interviews was that ‘there is no development to be seen on the ground for us.’

Forcibly excluded from the region’s mineral wealth, along the periphery of the Koidu Holdings site local people engage in improvised industry in the detritus of the mine. Scores of women and children pick their way delicately down the large boulder slopes carrying pans of stones on their heads. They are sorted into piles that will be smashed into gravel by school-aged children on the stoops of resettlement houses. The occasional kimberlite blocks that escape the company’s processors are hammered by men squatting in cages made of mosquito netting in case a diamond rolls out. Each time a new tributary of water bursts through the mine’s walls young men arrive within hours to sift through the nearby gravel in hopes that a stray diamond may still remain in the runoff. Many of these scavenging miners said they wished the company would simply sell buckets of the mine’s ‘tailing’, or residual gravel, since the tailings are assumed to have small diamonds inside. The company declines these requests. One miner said he had been told that the company was concerned they would need to raise salaries to retain employees if people could make as much money sifting through gravel on their own time.

Because the paramount chief is the main conduit through which the mine gains access to land, and there is no popular system to hold him to account, there is virtually no impetus for Koidu Holdings to contribute to the region’s development. The link between this underdevelopment, Koidu Holdings, and the paramount chief does not go unnoticed by the local population. There have been at least three periods of unrest during which protesters have been shot and killed by police contracted by the mine and the paramount chief, and nearby government buildings have been burned to the ground. Koidu Holdings touts the paramount chief as an indigenous ruler who can serve as an agent of development – the company’s close relationship with him thus constituting a sort of ultra-culturally competent form of community engagement – but these ‘customary’ trappings shroud more extractive power relations at play between the company and the chief, and the chief and his subjects.

Indirect rule and the underdevelopment of regulatory institutions

Over the past three decades, and especially in the wake of the Sierra Leone civil war and its perpetuation via the flow of ‘blood diamonds’, significant efforts have been made by international institutions and the Sierra Leone government to strengthen centralised regulatory bureaucracies and ensure fairer practices in diamond mining, trading and export. In 2012, the Sierra Leone government ordered the establishment the National Minerals Agency (NMA), a semi-autonomous body under the Ministry of Mines and Mineral Resources that is purported to have more enforcement power over the (substantial) licensure processes and the tax obligations that are stipulated in Sierra Leonean law. This happened alongside a broader process of decentralisation of political power through the Local Government Act of 2011, as well as other democratic reforms in the wake of the Sierra Leonean war (Fanthorpe, Lavali, and Sesay 2011; Republic of Sierra Leone 2012).

In this section, we consider why many of these regulatory reforms have been largely ineffective at mitigating the detrimental environmental, economic and political impact of diamond mining activities and often seem, on the ground, not to be implemented at all. Whereas in the previous section we described the use of the paramount chief’s lawful – albeit autocratic – authority to reclaim surface land, here we present a case study of a smaller-scale foreign diamond magnate’s use of indirect rule to evade licensure and regulatory requirements entirely. We demonstrate that licensure requirements and environmental regulations are essentially made null through the strategic and lucrative relationships between mining entities and paramount chiefs who ultimately call the shots and who can open up diamondiferous land to foreign exploitation without regard for legal requirements.

In late June 2016, residents of Koidu City, Kono District’s capital, found the Congo Town Bridge, which formed the main link between Kono District and the highway to Freetown, blockaded. Heavy machinery from a company belonging to Max, an Israeli mining and business magnate, had abruptly begun demolishing the structure. Many in the area seemed to be unsure who had authorised the bridge’s demolition, or why it had happened so suddenly. The land beneath the bridge was thought to be full of diamonds, but it had long been protected reserve land. A local official who had remained in Kono through the country’s civil war told us that ‘even the rebels executed anyone who tried to mine there.’ He and other local leaders were bewildered and appalled when Max’s workers showed up at the bridge and dug up and carted away the gravel – protected by heavily armed officers from the Sierra Leone Police as they worked.

It was clear at the time that the demolition and mining had not been authorised by national regulatory agencies. An official from NMA was quoted in a local newspaper as saying, ‘[It] is illegal and my office has condemned it regardless of who was involved in it’ (Senessie 2016). The 2009 Mines and Minerals Act outlines specific protocols for mining land within a 200-metre radius of a city and ‘set apart as a public highway’: such areas can only be mined with the ‘written consent of the local authority having control over the township’ (Republic of Sierra Leone 2010). The NMA seemed unable to organise a response, however, amidst the general confusion about who exactly was responsible for the activity and how it was so tightly organised (with state security officers, heavy machinery and a large group of labourers at work).

Soon, a story about what was happening at the Congo Town Bridge began to circulate within the shops and markets throughout Koidu. According to this story, Max had made a pitch to a ‘cabal’ of political leaders including the region’s paramount chief that the foundation of the bridge had been so damaged by illicit, small-scale miners that it needed to be repaired. He explained that if his company simply repaired the bridge without sifting through the gravel underneath and extracting all the diamonds, the small-scale miners would return to hack away at the foundation of the newly repaired bridge. So, he received permission from the paramount chief to cart away all the gravel, lest others be tempted to mine there in the future. The rumoured agreement was that he would backfill the site with large boulders from the nearby Koidu Holdings mine and rebuild the bridge. Those we interviewed on the periphery of the site felt certain that Max had concocted this explanation to mask his intention simply to extract diamonds from under the bridge and get out as quickly as he could – a story he could deploy in the unlikely chance that, in the future, he might be held to account.

The mining’s abrupt commencement, along with the powerlessness of the various local agencies tasked with regulating mining activity, infuriated area residents, some of whom lost their houses and land as a result of the flooding caused by the work. At the ruins of the Congo Town Bridge, several elderly men complained to us (though seemed unsurprised) about the absurdity that the local paramount chief – the ultimate ‘custodian of the land’ – had opened up this site to exploitation by a foreigner. They felt certain Max had paid the chief or offered him a position in his business plan. As we looked out at the heaps of mud and deep pools of water dotting people’s farms and hovels, we saw hordes of men in rags passing buckets filled with gravel to large piles to be carted off and cleaned.

One week later, tensions between local people and key figures involved in the mining scheme reached a fever pitch. Groups of angry youth had gathered at the mining site, hoping to find the paramount chief and Max. Both had fled to Freetown, anticipating this tension. Later that evening, the paramount chief’s compound was stoned. Fearing that the riots could turn dangerous, security officials deployed the military into the city to enforce a 7pm curfew. Tensions simmered, but eventually the protests died down, and the work continued. It took several months before the site was fully repaired and the road restored.

This ethnographic vignette brings into clear view the fact that paramount chiefs, who wield the authority to grant access to diamondiferous land, often operate as more beholden to foreign entities than to Sierra Leonean regulatory institutions. Although there have been significant efforts to bolster a bureaucratic process for distributing mining licences, and while regulatory institutions for monitoring the damage to the environment and livelihoods like that which the Congo Town community faced do nominally exist, such reforms have been impotently laminated on top of an existing system of indirect rule that still serves as the primary mode of access for foreign mining entities. And although there have been significant efforts after the civil war to promote local councils as a more liberal form of rural government that might better regulate and coordinate local development and relations with mining actors (Fanthorpe, Lavali, and Sesay 2011), we found they did not wield power commensurate with the chieftaincy. In fact, patronage networks linked to and bolstering the paramount chief have effectively penetrated and subsumed the Koidu City Council, as was demonstrated when a recent mayor pursuing lawsuits against mining companies for not paying required taxes was abruptly fired and chased to Freetown on what were widely considered sham charges (Thomas 2016).

It is evident that as long as paramount chiefs continue to wield such immense power of land and resources, efforts to build more democratic and bureaucratised regulatory systems will largely go in vain; foreign entities will be able to circumvent such systems, directly negotiate with and enrich the paramount chief, and access land without sophisticated oversight. In this regard, Max’s working through the paramount chief to access land is not merely a politically neutral strategy: it serves to strengthen systems of indirect rule at the expense of more substantial regulatory and revenue-generation schemes, and thus systematically contributes to the economic and political marginalisation of the rural population.

Indirect rule and tax evasion

In this section, we return to Koidu Holdings to explore how these various machinations of indirect rule coalesce to enable the company’s evasion of massive tax obligations. These lost taxes result in extremely weak public services, including political, educational and healthcare systems. We describe, first, how the suppression of regulatory institutions through strategies of indirect rule enables the outflow of unmonitored and untaxed corporate revenue. But we also suggest that the country’s social, political and public health underdevelopment – in part produced through the country’s lack of revenue-generating capacity – is in turn deployed by corporate actors like Koidu Holdings to further avoid paying mandated taxes. This analysis brings into sharp relief the mutually dependent relationship between Sierra Leone’s underdevelopment and foreign mining activities and is in part why we argue that Sierra Leone has been intentionally underdeveloped via contemporary indirect rule.

Koidu Holdings’ original lease agreement, first signed in 2002 and revisited in 2010, articulates a substantial profit-sharing agreement with the Sierra Leonean government, including a gradually increasing annual lease rent, income taxes of 35% and an additional 8% royalty rate for exceptionally large or valuable stones that are found (NMA 2010). On the company’s website, the company states that its objective is to demonstrate that ‘through responsible development of diamond projects, the good that flows into the local communities, the economy and the country can outweigh the perceived drawbacks’ (Koidu Limited n.d.a). Such language suggests that the extraction of diamond reserves by an international company is in fact the socially responsible thing to do in such an impoverished region. Presumably, the ‘good that flows into local communities’ would come about by formalising a trade that has been characterised by corruption, hidden flows of cash and ‘blood diamonds’, patronage systems and exploitation of workers (Smillie, Lansana, and Hazleton 2000).

But a recent investigative report, prompted by Koidu Holdings’ prominent presence in the so-called Panama Papers suggests that the company’s dealings and corporate structure are also shrouded in proverbial smoke and mirrors – on an international scale. The report showed that while Koidu Holdings’ production often accounts for 60–90% of the country’s annual diamond exports, recent tax registers do not document company paying any national income taxes at all (Sharife and Gbandia 2016). The corporation, for its part, has claimed that it is encountering serious financial woes due to falling diamond prices and the Ebola outbreak, and has thus defaulted both on payments to the Sierra Leone government as well as to the mine’s main investor, Tiffany and Co. (The United States Securities and Exchange Commission 2016). Amidst ongoing negotiations between the mine’s main creditor, the Sierra Leonean government and the Koidu Holdings administration, a top company official was covertly recorded saying that the mine’s management intended to continue to ‘run it [the mine], stop it and run away’ from the country without paying investors or back taxes (Africa Confidential 2015). But the Panama Papers also suggested that the company has but a few degrees of separation from a series of shell companies, flush with cash, that may be used to conceal revenue in order to defer taxes and other payments.

In this sense, the Ebola outbreak and the country’s instability has provided a mechanism for evading mandated taxes – revenue that could have been used to fund a healthcare system better able to stave off the massive loss of life during the 2014–2016 outbreak. This provokes a broader consideration of the mutually interdependent relationship between Sierra Leone’s underdevelopment and Koidu Holdings’ corporate activities, mediated through its indirect rule strategy. Indirect rule undermines the development revenue-generating institutions and facilitates tax evasion, which predispose the country to catastrophic public health events. Those catastrophes, in turn, justify the company’s evading even more taxes and further underdeveloping the healthcare system. This self-fulfilling cycle results in a lack of revenue-generating capacity visible at the local level: in what Paul Farmer (2015) terms a clinical and ‘public health desert’, poor roads and substandard schools where secondary school students we interviewed were largely illiterate.

Conclusion: illicit financial flows, indirect rule and the Ebola outbreak

Illicit financial flows (IFFs) are illegal movements of money or capital from one country to another (Global Financial Integrity 2015, World Bank 2017), thus reducing the amount of capital and revenue available within a country to develop public services such as healthcare systems. The non-profit organisation Global Financial Integrity estimates that Sierra Leone was subject to IFFs in the amount of US$558 million per annum for the 10 years leading up to the 2014–16 Ebola outbreak (Global Financial Integrity n.d.). Although the illicit flows leaving Sierra Leone arise from a number of different sectors, lost revenue and illicit movements of funds arising from extractive activities certainly constitute the greatest portion of IFFs (Frost 2012).

In the prior sections, we have detailed three mechanisms through which these IFFs may be produced through foreign diamond mining companies’ use of indirect rule: through massive and unfettered land reclamation; through the intentional underdevelopment of regulatory institutions that could monitor licensure and tax obligations; and through the (related) evasion of nominally mandated tax requirements. In this section, we consider the linkages between indirect rule and the 2014–2016 Ebola outbreak.

First, we will note that the Kono District outbreak, like the epidemic in much of the country, was almost entirely fuelled through mis-steps and chaos in severely under-resourced public health facilities. We show how the IFFs described above enabled the rapid spread of Ebola via these hospital-acquired infections (from an abysmally underdeveloped healthcare system) and an ineffective, containment-only public health response (Richardson et al. 2017). Second, we will consider the scaffolding of the outbreak response on structures of indirect rule, and describe how the role of the paramount chieftaincy in the public health response facilitated graft, chaos and distrust of the public health system.

Indirect rule and weak healthcare systems

While conducting serosurveys as part of other research, we traced the Kono outbreak from Ndambie to Gbongor, two small villages along the main highway to Freetown. We learned that several prominent community members, later blamed for spreading Ebola due to their extensive social networks and ‘non-compliance’ with public health directives, had each tried to access care at the hospital and were inadequately screened and deemed not at risk for having Ebola before being sent back to their villages. Our further investigations of the major transmission events in Kono revealed that nearly every other ‘super-spreading’ event was precipitated by a patient who had visited and had been turned away from a health facility after an incorrect diagnosis, and that dozens of patients contracted Ebola from unclean facilities and overcrowded ambulances.

At the same time that numerous Ebola patients were arriving each day at Koidu Government Hospital from Ndambie and Gbongor villages, nearly 20 Ebola corpses were decomposing in the wards, and a majority of healthcare workers staffing the improvised Ebola containment response were contracting the disease, Koidu Holdings had a fully stocked hospital, complete with the only X-ray machine in the district, a surgery ward and a team of expatriate health workers less than three miles away from Kono’s isolation unit (Koidu Limited n.d.b). Attending to such gravely different realities in close proximity underscores the ‘intentionality’ of Sierra Leone’s health system underdevelopment and its manifestation as viral disease. The oft-repeated references to the country’s ‘lack of development’ – including its status as number 181 out of 188 on the Human Development Index (United Nations Development Programme n.d.) – efface the fact that huge deposits of wealth have been extracted within Sierra Leone, with little in the way of public goods to show for it, and that while the country was receiving US$424 million per annum in official development aid over the 10 years leading up to the outbreak (World Bank n.d.), it was losing US$558 million per year to illicit flows (Global Financial Integrity n.d.). In addition, the revenue lost just from official tax incentives to major foreign companies – let alone from the graft described above – could have financed more than one-third of the cost of a fully functional health system for the country3 that would have been able to identify, control and address an Ebola outbreak without significant spread. With this in mind, one might even consider the unfettered spread of Ebola as an embodied result of diamond corporations’ efforts to maintain inexpensive access to minerals – all by undermining political and social development via recycled strategies of indirect rule.

Indirect rule and the public health response

The precarity of survival and abysmal healthcare infrastructure during the Ebola outbreak in Kono does not merely exist in continuity with a century of indirect rule. In fact, the same political actors, institutions and para-institutions that over the past 120 years have facilitated foreign access to diamond deposits were the ones that ultimately commanded the outbreak response. The same paramount chief who was thought to have colluded with Max’s venture, is on Koidu Holdings’ board of directors and is managing the resettlement process, was appointed by the president of Sierra Leone to serve as the director of the District Ebola Response Centre, the highest position in the region’s response. His appointment occurred after several months of ineffective management of the response by the severely underequipped and understaffed district health management team; in this sense, we may consider the paramount chief’s appointment as a turning over, so to speak, of the Ebola response from an impotent and under-funded government institution to the paramount chieftaincy (and another indirect rule redux). As a result, the paramount chief was given access to enormous financial resources, an additional salary, a fleet of vehicles to manage response efforts and employment, and motorbikes, jobs and other resources were subsequently distributed through patronage networks. The outbreak response under the paramount chief was arguably not more effective, but significantly more draconian (including several 5pm ‘mop-up’ campaigns in which soldiers arrived unannounced in caravans into ‘hot-spot’ villages and scoured communities for hidden Ebola patients).

Many healthcare and development NGOs soon followed suit, directing their resources and efforts through the paramount chiefs both because of the chiefs’ authority and experience managing large flows of resources, and as a means of touting the organisations’ ‘cultural competence’ in collaborating with, patronising and deferring to chiefs as representatives of local communities and as a proxy form of local engagement. In reality, such deference to paramount chiefs kept popular grievances at arm’s length and from materialising into a productive political mobilisation. In this way, the international ‘crisis caravan’ (Polman 2011) (which has perpetually swept into and out of the country during the civil war, during the Ebola outbreak, and during intervening years of Sierra Leone’s constant ‘public health emergency’) could very well have set back the goals of decentralisation and rural democratisation by scaffolding a public health response onto such a patrimonial system of governance, while in the process shoring up despotic rule as the price of a more ‘efficient’ Ebola response.

Retrospective analyses of funding streams during the outbreak have similarly indicted the way that global health financing apparatuses interfaced with patrimonial political systems on a national scale. A 2015 report by national auditors found that almost one-third of all Ebola relief funds in Sierra Leone were unaccounted for, many of which are thought to have been funnelled through existing systems through political patronage networks as the response was increasingly turned over to existing systems of indirect rule (Audit Service Sierra Leone 2015). This opinion was widely shared by Ebola survivors and local political leaders we interviewed, and also led to eruptions of violence in Kono such as when Koidu Government Hospital was attacked by youth in October 2014 aligned with competing political factions each accusing the other of inventing or exaggerating the Ebola risk for political and economic gain (Johnson 2014).

In addition to enabling the predatory and ineffective use of public health resources, the public optics of a healthcare system mediated through systems of indirect rule have profound implications for the ways in which local people interact with the healthcare system. The lack of ‘trust’ in the healthcare system has been identified as a key reason why patients were not more rapidly turned over to the healthcare system for isolation and often solitary death. Trust is often described within the public health literature as something that will be engendered through outreach, education campaigns and the marginalisation of local understandings of disease and healing (Chandler et al. 2015; Dhillon and Kelly 2015; Nuriddin et al. 2018). We hope that this analysis may prompt a consideration of much more proximal political-economic origins; when a political system that for 120 years has enabled the subjugation of rural Sierra Leoneans as well as the extraction of critical financial resources is tasked with orchestrating a complex and at times draconian outbreak response, it is no wonder that patients may prefer to remain in the care of the families and loved ones rather than call for an ambulance directed by the paramount chief. Thus, efforts to dismantle systems of indirect rule may not only bolster much-needed tax revenue for health systems strengthening, but may also be considered, in the language of biosecurity technocrats, to contribute to a ‘reservoir’ of community trust to be drawn on in a future public health emergency.

That much of the Ebola humanitarian care apparatus has now been scaled down, long-term health aid dramatically reduced and that the health system is returning to pre-Ebola conditions underscores the (il)-logics of much of the international reaction to the epidemic as well as the durability of underlying political and social systems in places like Kono. Indirect rule endures in an untouched form, continuing to enable corporations’ evasion of regulatory and taxation requirements, displacing ever greater numbers of rural people, and contributing to Sierra Leone’s continued healthcare underdevelopment. Post-Ebola health programmes continue to be funnelled through paramount chiefs, further strengthening indirect rule through the political economy of health aid. Ultimately, we hope this article can serve as an initial effort to diagnose a ‘sick’ system of governance and public health in Kono, while also encouraging social scientists to trace the pathological ramifications of other illicit financial flows.

Figure 1.

Man smashing runoff kimberlite from the mine.

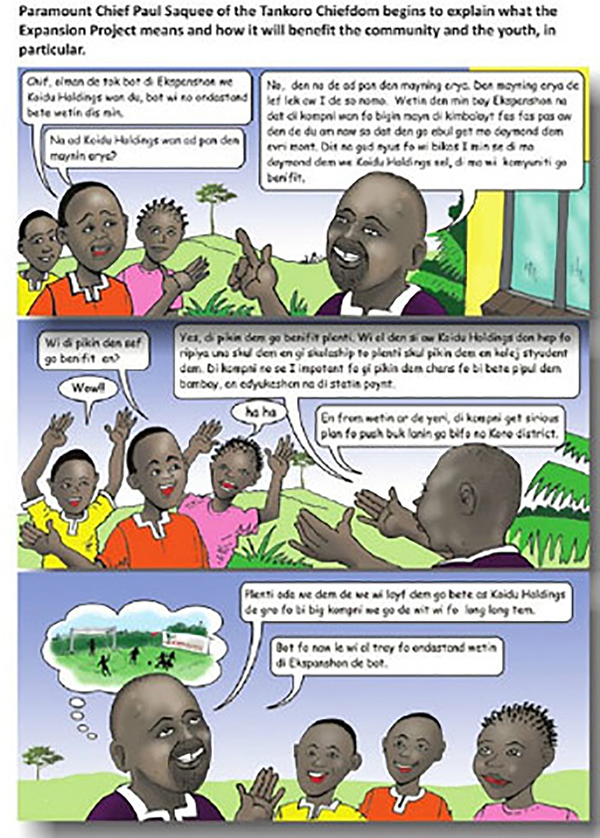

Figure 2.

Cartoon of the paramount chief explaining about the ‘Expansion Project ... and how it will benefit the community and the youth, in particular.’ Koidu Holdings website, http://www.koiduholdings.com/lib/slir/w1280-h1024-q/images/gallery/sustainability/environment/esia/09%20BID.jpg.

Figure 3.

The Congo Town Bridge site after destruction, with Koidu Holdings’ mine-tailings in the distance.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of Partners in Health–Sierra Leone for their support for this research, Sahr David Kpakiwa for invaluable research assistance and translation, Vincanne Adams for feedback on an early draft of this article, as well as feedback from two anonymous reviewers. We are grateful to all of the interlocutors we spoke with in Kono who shared their stories and insights.

Funding

This work was conducted with the support of a KL2/Catalyst Medical Research Investigator Training award (an appointed KL2 award) from Harvard Catalyst | The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health Award KL2 TR002542). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard Catalyst, Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centres, or the National Institutes of Health. This work was also supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) Medical Scientist Training Program Grant No. T32GM007618.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

For a discussion of possible ‘indigenous’ pre-colonial governing institutions connected with the poro society (the male ‘secret society’ for many West African Mande ethnic groups that may have served as a check on the unilateral power of local chiefs), see Little 1965. The colonial authorities sought to suppress the influence of the poro and formally banned it in 1897. In certain ways, secret societies have now been subsumed into the paramount chieftaincy system and do bolster the power of paramount chiefs by endowing them with trappings of what might be termed a Weberian traditional authority (Weber 1964). However, secret societies also serve as semi-independent blocs that may balance the unilateral authority of paramount chiefs, and may be involved in the (exceedingly rare) cases in which paramount chiefs are deposed.

Note that the creation of the chieftaincy system in Krio-dominated Freetown followed a different history and, given that Freetown is not diamondiferous, is not the focus of our study.

To estimate the cost of a fully functional health system, we multiplied the population of Sierra Leone by the recommended minimum government health expenditure of US$86 per person (McIntyre and Meheus 2014).

References

- Abraham Arthur. 1978. Mende Government and Politics Under Colonial Rule: A Historical Study of Political Change in Sierra Leone, 1890–1937. Freetown: Sierra Leone University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Acemoglu Daron, Chaves Isaías N., Osafo-Kwaako Philip, and James Robinson. 2014. “Indirect Rule and State Weakness in Africa: Sierra Leone in Comparative Perspective” NBER Chapters. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc; http://econpapers.repec.org/bookchap/nbrnberch/13443.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Africa Confidential. 2015. “Stalemate over Koidu Diamonds as Economy Sinks.” December 4, 56 (24). http://www.africa-confidential.com/article/id/11363/Stalemate_over_Koidu_diamonds_as_economy_sinks. [Google Scholar]

- Audit Service Sierra Leone. 2015. “Report on the Audit of the Management of the Ebola Funds (May to October 2014).” ReliefWeb, February 13. http://reliefweb.int/report/sierra-leone/audit-service-sierra-leone-report-audit-management-ebola-funds-may-october-2014.

- Cartwright John R. 1970. Politics in Sierra Leone, 1947–1967. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler Clare, Fairhead James, Kelly Ann, Leach Melissa, Martineau Frederick, Mokuwa Esther, Parker Melissa, Richards Paul, and Wilkinson Annie. 2015. “Ebola: Limitations of Correcting Misinformation.” The Lancet 385 (9975): 1275–1277. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62382-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corby Richard A. 1990. “Educating Africans for Inferiority under British Rule: Bo School in Sierra Leone.” Comparative Education Review 34 (3): 314–349. [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon Ranu S., and Kelly J. Daniel. 2015. “Community Trust and the Ebola Endgame.” New England Journal of Medicine 373 (9): 787–789. 10.1056/NEJMp1508413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanthorpe Richard, Lavali Andrew, and Sesay Mohamed Gibril. 2011. “Decentralization in Sierra Leone: Impact, Constraints and Prospects” Report funded by UK Department for International Development Sierra Leone. Purley, UK: Fanthorpe Consultancy Ltd; https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08ab340f0b652dd000868/DecentralizationResearchReportFINAL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer Paul. 2015. “Who Lives and Who Dies.” London Review of Books, February 5. [Google Scholar]

- Fassin Didier, and Rechtman Richard. 2009. The Empire of Trauma: An Inquiry into the Condition of Victimhood. Translated by Gomme Rachel. 1st ed. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson James. 1994. Anti-politics Machine: Development, Depoliticization, and Bureaucratic Power in Lesotho. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frost Diane. 2012. From the Pit to the Market: Politics and the Diamond Economy in Sierra Leone. Woodbridge, UK: James Currey. [Google Scholar]

- Sharife Khadija, and Gbandia Silas. 2016. “Flaws in Sierra Leone’s Diamond Trade.” The African Network of Centers for Investigative Reporting; April 4 https://panamapapers.investigativecenters.org/sierra-leone/. [Google Scholar]

- Global Financial Integrity. 2015. “Illicit Financial Flows from Developing Countries: 2004–2013.” Global Financial Integrity (blog). December http://www.gfintegrity.org/issue/illicit-financial-flows/.

- Global Financial Integrity. n.d “Data by Country.” Global Financial Integrity (blog). Accessed June 19, 2018 http://www.gfintegrity.org/issues/data-by-country/.

- Harbottle Michael. 1976. The Knaves of Diamonds. London: Seeley, Service and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Rod Mac. 2014. “Two Die in Sierra Leone Riot Sparked by Ebola Tests.” Corridor Gazette, October 22 http://corridorgazette.co.za/?page_id=162713&afp-story-id=24629. [Google Scholar]

- Keefe Patrick Radden. 2013. “Buried Secrets.” The New Yorker, July 8 http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2013/07/08/buried-secrets.

- Koidu Limited. n.d.a “Diamonds Doing Good.” Accessed August 25, 2016 http://www.koiduholdings.com/diamonds-doing-good.php.

- Koidu Limited. n.d.b “Healthcare.” Accessed September 16, 2016 http://www.koiduholdings.com/sustainability-community-healthcare.php.

- Little Kenneth. 1965. “The Political Function of the Poro: Part I.” Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 35 (4): 349–365. 10.2307/1157659. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lugard Frederick D. 1922. The Dual Mandate in British Tropical Africa. Edinburgh: W. Blackwood and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Manson Katrina. 2013. “Battlefields, Diamonds and the ‘Hell’ of the MBA.” Financial Times, October 7 http://www.ft.com/cms/s/2/95a65f74-08b7-11e3-8b32-00144feabdc0.html#axzz4H2wrqjwl.

- McIntyre Di, and Meheus Filip. 2014. “Fiscal Space for Domestic Funding of Health and Other Social Services.” Centre on Global Security Working Group Papers. London: Chatham House; https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/files/chathamhouse/home/chatham/public_html/sites/default/files/20140300DomesticFundingHealthMcIntyreMeheus.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NMA (National Minerals Agency, Sierra Leone). 2010. “Mining Lease Agreement Between The Republic of Sierra Leone and Koidu Holdings S.A. Relating to the Mining and Commercial Exploitation of the Koidu Kimberlites in a Project to Be Known as ‘The Koidu Kimberlite Project’.” Freetown: Sierra Leone Resource Contracts; (Online Contracts Database). http://www.nma.gov.sl/resourcecontracts/contract/ocds-591adf-0857214071/view#/. [Google Scholar]

- Nuriddin Azizeh, Jalloh Mohamed F., Meyer Erika, Bunnell Rebecca, Bio Franklin A., Jalloh Mohammad B., Sengeh Paul, et al. 2018. “Trust, Fear, Stigma and Disruptions: Community Perceptions and Experiences during Periods of Low but Ongoing Transmission of Ebola Virus Disease in Sierra Leone, 2015.” BMJ Global Health 3 (2): e000410 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polman Linda. 2011. The Crisis Caravan: What’s Wrong with Humanitarian Aid? New York: Picador. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Sierra Leone. 2009. The Chieftaincy Act, 2009.

- Republic of Sierra Leone. 2010. The Mines and Minerals Act, 2009. Act: Supplement to the Sierra Leone Gazette Vol. CXLI, No. 3 January 7 http://www.sierra-leone.org/Laws/2009-12.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Sierra Leone. 2012. The National Minerals Agency Act, 2012. Vol. supplement to the Sierra Leone Gazette. [Google Scholar]

- Richards Paul. 2005. “To Fight or to Farm? Agrarian Dimensions of the Mano River Conflicts (Liberia and Sierra Leone).” African Affairs 104 (417): 571–590. 10.1093/afraf/adi068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson Eugene T., Mohamed Bailor Barrie Cameron T. Nutt, Kelly J. Daniel, Frankfurter Raphael, Fallah Mosoka P., and Farmer Paul E. 2017. “The Ebola Suspect’s Dilemma.” The Lancet: Global Health 5 (3): e254–256. 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senessie Septimus. 2016. “Special Report: Kono Divided over Town Mining.” Politico SL News, June 23 http://politicosl.com/articles/special-report-kono-divided-over-town-mining. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw Rosalind. 2002. Memories of the Slave Trade: Ritual and the Historical Imagination in Sierra Leone. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smillie Ian, Lansana Gberie, and Hazleton Ralph. 2000. “The Heart of the Matter: Sierra Leone, Diamonds and Human Security (Complete Report).” Ottawa: Partnership Africa Canada. [Google Scholar]

- The Association of Journalists on Mining and Extractives (AJME). 2009. “Mining Watch Sierra Leone.” June 12 Magazine produced by AJME in collaboration with the Network Movement for Justice and Development, with support from Promoting Agriculture Governance and the Environment. [Google Scholar]

- The United States Securities and Exchange Commission. 2016. “Form 10-K: Annual Report of Tiffany & Co. for the Fiscal Year Ended January 31, 2016.” January 31 Washington, DC: US Securities and Exchange Commission; https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/98246/000009824616000211/tif-2016131×10k.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas Abdul Rashid. 2016. “Political Tension Rises in Koidu – Eastern District of Sierra Leone.” Sierra Leone Telegraph (blog). February 28 http://www.thesierraleonetelegraph.com/political-tension-rises-in-koidu-eastern-district-of-sierra-leone/.

- United Nations Development Programme. n.d “Human Development Index (HDI).” Accessed September 16, 2016 http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-index-hdi.

- United Nations World Food Programme. 2011. “Sierra Leone – The State of Food Security and Nutrition.” August https://www.wfp.org/content/sierra-leone-state-food-security-and-nutrition-2011.

- Walker James W. St. G. 1992. The Black Loyalists: The Search for a Promised Land in Nova Scotia and Sierra Leone, 1783–1870. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; http://trove.nla.gov.au/version/27178615. [Google Scholar]

- Weber Max. 1964. The Theory of Social and Economic Organization. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. 2017. “Illicit Financial Flows (IFFs).” Washington, DC: The World Bank; http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/financialsector/brief/illicit-financial-flows-iffs. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. n.d “Net Official Development Assistance and Official Aid Received.” Accessed June 19, 2018 https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/DT.ODA.ALLD.CD?end=2007&start=2006.

- World Health Organization. n.d. “Sierra Leone: Country Profiles (Global Health Observatory Data).” Accessed June 15, 2017 http://www.who.int/gho/countries/sle/country_profiles/en/.

- Zack-Williams Babatunde. 1990. “Diamond Mining and Underdevelopment in Sierra Leone - 1930/1980.” Africa Development/Afrique et Développement 15 (2): 95–117. [Google Scholar]