Abstract

Metagenomic sequence data from defined mock communities is crucial for the assessment of sequencing platform performance and downstream analyses, including assembly, binning and taxonomic assignment. We report a comparison of shotgun metagenome sequencing and assembly metrics of a defined microbial mock community using the Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) MinION, PacBio and Illumina sequencing platforms. Our synthetic microbial community BMock12 consists of 12 bacterial strains with genome sizes spanning 3.2–7.2 Mbp, 40–73% GC content, and 1.5–7.3% repeats. Size selection of both PacBio and ONT sequencing libraries prior to sequencing was essential to yield comparable relative abundances of organisms among all sequencing technologies. While the Illumina-based metagenome assembly yielded good coverage with few misassemblies, contiguity was greatly improved by both, Illumina + ONT and Illumina + PacBio hybrid assemblies but increased misassemblies, most notably in genomes with high sequence similarity to each other. Our resulting datasets allow evaluation and benchmarking of bioinformatics software on Illumina, PacBio and ONT platforms in parallel.

Subject terms: DNA sequencing, Metagenomics, Data acquisition, Hardware and infrastructure

| Measurement(s) | metagenomic data • sequence_assembly |

| Technology Type(s) | ONT MinION • Illumina sequencing • PacBio RS II |

| Factor Type(s) | sequencing platform |

| Sample Characteristic - Organism | Bacteria |

| Sample Characteristic - Environment | mock community |

Machine-accessible metadata file describing the reported data: 10.6084/m9.figshare.10260740

Background & Summary

Accurate microbial community representation based on cultivation-independent genome sequencing methods has been one of the major challenges in microbial ecology and genomics since the onset of shotgun metagenome sequencing. Existing sequencing technologies display platform-specific biases depending on run mode and chemistry. These biases affect read length, data throughput, GC coverage bias, error rates, and the ability to resolve repetitive genomic elements1–3. The Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT) MinION is the first commercially available sequencer that uses nanopores. In the MinION, nanopore sequencing discriminates individual nucleotides by measuring the change in electrical conductivity as DNA molecules pass through a biological pore4. The ONT MinION is a portable sequencing device generating maximum read lengths in excess of 100 kb with the potential to span long repeats, and at comparably low cost and high-speed (our test runs yielded 10–50 Gb in 48 hours). To date most published studies using the MinION technology focus on (i) whole genome sequencing (WGS) of organisms with existing reference genomes and on (ii) validating or resolving difficult regions or screens of target genes/gene regions in viral5–12, bacterial5,6,13–28, and eukaryotic29–44 genomes. Laver et al. compared ONT performance for three bacterial strains with % GC of ~29–71% and showed that the strain with highest % GC was underrepresented in the sequencing reads45. Various genome assemblies were shown to improve in hybrid approaches with Illumina reads30 and reached 99.5% nucleotide identity for a de novo assembly of E. coli13. To our knowledge, only two ONT shotgun metagenome studies exist, one of an environmental sample in which DNA was fragmented to ~510–840 bp and the resulting 2D reads (0–1200 bp) were mapped against a database of 400 bp gene fragments46, and the other of various low complexity mock communities comparing different long read classification tools47. To date, there has not been an ONT shotgun metagenome study that evaluates its long reads in the context of mapping accuracy, assembly contiguity, and overall community representation.

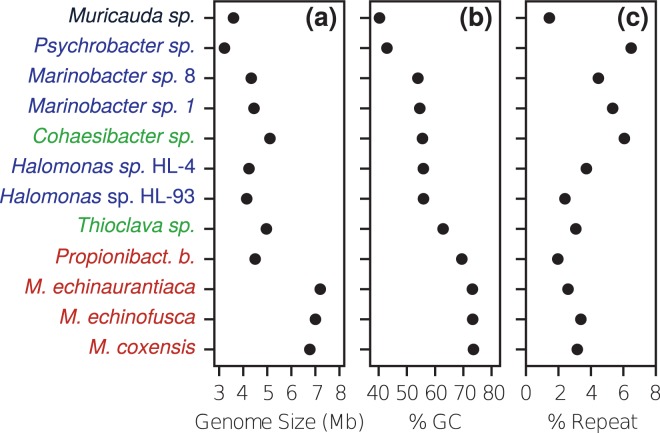

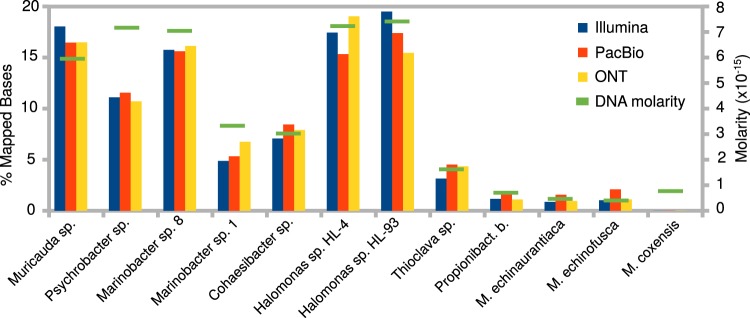

We used a defined community (composed of a pool of separately extracted DNAs), BMock12, that includes 12 bacterial strains belonging to two phyla (Actinobacteria and Flavobacteria) and 2 proteobacterial classes (Alpha- and Gammaproteobacteria). Genomes from these taxa represent a breadth of genome sizes and range from low to high % GC with variable repeat fractions. Bmock12 includes three actinobacterial genomes of the genus Micromonospora characterized by high %GC content and high average nucleotide identity (ANI), which present challenges for assembly (Fig. 1, Table 1). Shotgun sequencing performance on ONT MinION was compared to other state-of-the-art platforms, Pacific Biosciences RS-II and Illumina HiSeq. 2500 (Table 2). Interestingly, we noticed a major impact of input DNA size selection during library preparation on the length distribution of mapped reads in ONT data, favoring the sequencing of shorter reads, which also resulted in a slightly skewed community structure (Figs. S1, S2). After size selection and removal of reads <10 kb, relative abundances of each organism were found to be comparable across all sequencing technologies, and equally correlated to molarity (Fig. 2, Tables S1, S2 and S3). Average % identity of both ONT and PacBio mapped reads was 85.9% (Figs. S3, S4). A negligible number of reads were mapped to M. coxensis, likely due to low input DNA concentration or quality, or as a result of pipetting error and/or inaccuracies in DNA quantification as was observed previously48. Therefore, this organism was omitted from the remainder of the analysis. Other disagreements between the distributions of % mapped bases and DNA molarity are likely due to these same noise factors.

Fig. 1.

Microbial mock community strains display a large spread with respect to genome size, % GC and repeat content. Order was determined by GC content. Colors indicate phylum/class of each organism. Black = Bacteroidetes, Green = Alphaproteobacteria, Blue = Gammaproteobacteria, Red = Actinobacteria.

Table 1.

All genomes are available as improved high-quality drafts in the IMG database. See Fig. S1 for detailed statistics.

| IMG Taxon ID | Organism | Phylum | Class |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2615840527 | Muricauda sp. ES.050 | Bacteroidetes | Flavobacteria |

| 2615840533 | Thioclava sp. ES.032 | Proteobacteria | Alphaproteobacteria |

| 2615840601 | Cohaesibacter sp. ES.047 | Proteobacteria | Alphaproteobacteria |

| 2615840646 | Propionibacteriaceae bacterium ES.041 | Actinobacteria | Actinobacteria |

| 2615840697 | Marinobacter sp. LV10R510-8 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria |

| 2616644829 | Marinobacter sp. LV10MA510-1 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria |

| 2617270709 | Psychrobacter sp. LV10R520-6 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria |

| 2623620557 | Micromonospora echinaurantiaca DSM 43904 | Actinobacteria | Actinobacteria |

| 2623620567 | Micromonospora echinofusca DSM 43913 | Actinobacteria | Actinobacteria |

| 2623620609 | Micromonospora coxensis DSM 45161 | Actinobacteria | Actinobacteria |

| 2623620617 | Halomonas sp. HL-4 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria |

| 2623620618 | Halomonas sp. HL-93 | Proteobacteria | Gammaproteobacteria |

Table 2.

Run information and statistics for each sequencing platform. Average quality score for Illumina reads was 35.3. Percent identity was calculated as E/(E + I + D + S), where, E, I, D, S represent exact matches, insertions, deletions and substitutions respectively.

| Illumina | PacBio | ONT | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Instrument model | HiSeq-2500 1TB | RS-II | MinION |

| Sequencing chemistry | TruSeq SBS v.4 | RSII v. C4 | R9.4.1 (flow cell) |

| Run mode | 2 × 150 indexed run | 1 × 240 sequencing movie run | |

| Raw reads | 426,735,646 | 389,806 | 187,507 |

| Filtered reads | 422,896,888 | 389,806 | 187,507 |

| Filtered bases | 63,384,840,109 | 2,583,337,248 | 3,737,495,058 |

| Average insert/read size [bp] | 302.70 | 6,627.00 | 19,932.60 |

| Longest insert/read [bp] | 625 | 45,165 | 145,720 |

| Uniquely mapped reads | 411,863,512 | 376,583 | 187,448 |

| %Identity | 99.8 | 85.9 | 85.9 |

Fig. 2.

Distribution of mapped bases for each organism and technology, and molarity of each genome in the mock community. Molarities strongly correlate with mapped bases (Pearson correlation coefficient: 0.95) for all sequencing platforms. The total number of bases that mapped to M. coxensis was negligibly small.

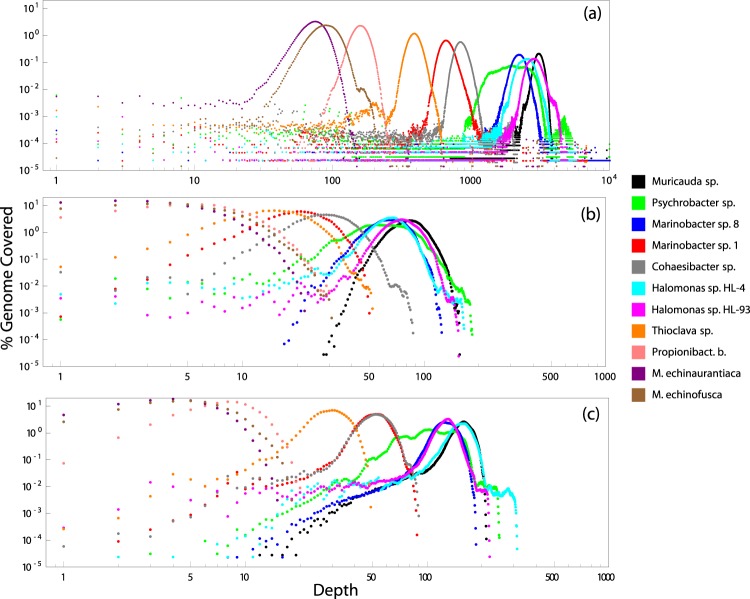

Although reads <10 kb were removed from ONT and PacBio datasets, the distribution of read lengths peaked at ~12 kb in ONT vs. ~5 kb in PacBio data, because PacBio sequences generally tend to favor shorter DNA molecules49 and likely because size selection for ONT was more successful (Fig. S5). The length distribution of reads mapped to each organism was found to be nearly the same within each sequencing platform (Fig. S6). PacBio and ONT reads displayed comparable distribution patterns of % genome coverage over sequencing depth (Figs. 3 and S7), and in contrast to Illumina reads, they did not show any notable GC bias (Fig. S8). Illumina sequences have previously been described to discriminate against GC-poor and GC-rich genomes and DNA regions50–52. Read mapping errors were mostly substitutions and deletions and, to a lesser degree, insertions for ONT, whereas PacBio errors were dominated by insertions (Figs. S9, S10).

Fig. 3.

Genome coverage for all organisms and sequencing platforms displayed on a log-log scale. M. coxensis is excluded due to lack of mapped reads.

Metagenome assembly was performed using (1) only Illumina reads, (2) Illumina and PacBio reads, or (3) Illumina and ONT reads. Illumina-only assemblies performed well and yielded at least 92.6% reference coverage (Table 3). 6 out of 11 Illumina-only genome assemblies displayed fewer misassemblies than the hybrid assemblies, which is likely due to the increased error rate in long reads. Misassemblies in hybrid assemblies were particularly high for the two Halomonas spp., which shared 99% ANI, indicating that hybrid assemblies might generally be challenged by the presence of strains of the same species, or more generally with high % ANI to each other. In the case of the two Marinobacter spp., which shared 85% ANI, only one of the two genomes generated few misassemblies in the hybrid assemblies (Tables 3 and S4). For all genomes, except that of Proprionibacter bacterium, contiguity improved greatly in the hybrid assemblies. In some hybrid assemblies, the total number of contigs was reduced by an order of magnitude. Illumina + ONT assemblies were less fragmented than Illumina + PacBio assemblies due to the longer average read lengths of the ONT reads (Fig. S11). ANI between genome pairs was the main factor determining the assembly quality (Table S4). Genomes that are closely related to others (particularly two Halomonas strains with 99% ANI) yielded lower quality assemblies (Table S5). This effect of strain heterogeneity on metagenome assembly has been previously reported through extensive benchmarking53. Similarly, genomes with high repeat content (Psychrobacter, Cohaesibacter, and both Marinobacter species) resulted in more fragmented assemblies as compared to others. Reference coverage was the same or better in hybrid assemblies with the exception of Halomonas sp. HL-4 (Table 3). Total aligned length was comparable between all sequencing technologies (Table S4). Genomes pairs with relatively high ANI (two Halomonas strains, Marinobacter sp. LV10R510-8, Marinobacter sp. LV10MA510-1, M. echinaurantiaca and M. echinofusca) displayed assembly lengths larger than their references, which resulted from contigs that mapped to more than one reference genome.

Table 3.

Assembly statistics. NGA50 is the length of the shortest in the set of blocks of that length or longer covers at least 50% of the reference genome after alignment. Blocks are parts of contigs split at misassembly events.

| Assemblies | Total Length [bp] | Reference Coverage [%] | No. Contigs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina Only | Illumina + ONT | Illumina + PacBio | Illumina Only | Illumina + ONT | Illumina + PacBio | Illumina Only | Illumina + ONT | Illumina + PacBio | |

| Muricauda sp. | 3,579,780 | 3,596,256 | 3,590,644 | 99.6 | 99.8 | 99.9 | 14 | 3 | 2 |

| Thioclava sp. | 4,898,095 | 4,940,417 | 4,933,303 | 98.6 | 99.5 | 99.3 | 65 | 3 | 8 |

| Cohaesibacter sp. | 4,943,283 | 5,151,317 | 4,995,520 | 96.7 | 98.5 | 97.4 | 139 | 23 | 72 |

| Propionibact. b. | 4,495,270 | 4,495,756 | 4,495,756 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Marinobacter. sp. 8 | 4,337,062 | 9,170,029 | 5,788,008 | 98.6 | 100.0 | 99.8 | 98 | 11 | 25 |

| Marinobacter sp. 1 | 4,371,813 | 7,274,187 | 5,460,448 | 96.3 | 99.6 | 98.5 | 114 | 20 | 38 |

| Psychrobacter sp. | 3,173,207 | 3,229,220 | 3,224,906 | 97.4 | 99.2 | 99.1 | 122 | 41 | 44 |

| M. echinaurantiaca | 7,164,504 | 7,193,150 | 7,172,232 | 99.3 | 99.7 | 99.5 | 49 | 6 | 17 |

| M. echinofusca | 6,965,883 | 11,125,773 | 7,412,507 | 99.4 | 100.0 | 99.6 | 60 | 5 | 19 |

| Halomonas sp. HL-4 | 4,007,588 | 7,577,667 | 4,772,878 | 92.6 | 99.3 | 85.0 | 477 | 56 | 149 |

| Halomonas sp. HL-93 | 4,186,714 | 7,535,492 | 5,037,941 | 98.1 | 99.3 | 96.4 | 503 | 43 | 118 |

| not_aligned | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 240 | 239 | 240 |

While arriving at the true community composition of complex microbiomes will remain challenging, current advancements in sequencing protocols have resulted in reduced bias, improved resolution, and more predictable error. Metagenomic sequence data from defined samples, such as MBARC-2654, HMP55, and the BMock12 data described here are critical to not only assess new or modified wet lab protocols56 and performance of sequencing platforms57, but also downstream analytical tools and pipelines used to derive biological insights from metagenome datasets53,58. While ONT had been primarily used for WGS for organisms with existing reference genomes, and hybrid assemblies as well as diagnostics, our study shows that shotgun metagenome data generated on the MinION yields community representation and improved genome assembly contiguity that is comparable to that of the Illumina-PacBio hybrid assembly contiguity (Table 4). As sequencing accuracy and throughput reliability improve and with the development of long read assemblers, this platform is headed towards stand-alone long-read assemblies that are suitable for accurate representations of microbial community structure and predicted function in complex environmental samples.

Methods

Cultivation and DNA extraction

Cultures of Micromonospora coxensis DSM 45161, Micromonospora echinaurantiaca DSM 43904, and Micromonospora echinofusca DSM 43913 were grown aerobically in DSMZ medium 65 Gym Streptomyces Medium (https://www.dsmz.de/?id=441) (DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany) at 28 °C. Genomic DNA was isolated using the MasterPure Gram Positive DNA Purification Kit (Epicentre, Madison, WI) following the standard protocol provided by the manufacturer but modified by incubating on ice overnight on a shaker and the use of an additional 1 µl proteinase K.

Cultures of Halomonas sp. HL-4 and Halomonas sp. HL-93 were grown aerobically in Hot Lake Heterotroph (HLH) medium59 at 30 °C. Genomic DNA was isolated using phenol-chloroform extraction as previously described60.

Cultures of Thioclava sp. ES.032, Propionibacteriaceae bacterium ES.041, Cohaesibacter sp. ES.047, and Muricauda sp. ES.050 were grown aerobically on modified PE agar plates61. Biomass from 1–2 plates was scraped and genomic DNA was isolated using the Qiagen bacterial extraction protocol for the Genomic-tip 500/G kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD), with minor modifications. Briefly, in addition to the buffer B1, proteinase K and RNase additions, an enzyme cocktail composed of 500 ml achromopeptidase (10 U/ml), 500 ml lysostaphin (0.2 U/ml), 500 ml of lysozyme (100 mg/ml) and 1 ml mutanolysin (1 U/ml) was added to the samples. Samples were placed on a shaker and incubated at 37 °C overnight to lyse the cells. Genomic DNA was extracted the next day using the genomic-tips 500/G, as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

The Marinobacter and Psychrobacter strains isolated from Antarctic Lake Vida (Marinobacter sp. LV10R510-8, Marinobacter sp. LV10MA510-1, and Psychrobacter sp. LV10R520-6) were grown aerobically in R2A media (Difco) with 5% NaCl (25 mL each) under non-shaking conditions at 10 °C. Cells were pelleted by centrifuging for 5 minutes at 12,000 × g. High molecular weight genomic DNA was isolated following Ausubel62. Briefly, cells were resuspended in TE buffer with 10% SDS and proteinase K (final concentration) then following 1 hr. incubation at 37 °C, CTAB (hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide)/NaCl was added to extract the nucleic acids, and chloroform: isoamylalcohol was used to purify the preparation. The crude extract was digested with RNAse and then the HMW gDNA was precipitated in isopropanol, and following drying, the pellet was resuspended in TE.

All DNA extracts were checked for quality and quantified using a Qubit fluorometer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and visually by quantitative gel. Samples were pooled at varying ratios from 1.6–16.2% to generate the mock community (Table 1).

Library creation and sequencing

For Illumina library creation, 100 ng of genomic DNA, brought up to a total of 100 μl in TE, was sheared to 300 bp using the Covaris LE200 (Covaris, Inc. Woburn, MA, USA) and size-selected using SPRI beads (Roche Holding AG, Basel, Switzerland): 60 μl of beads were added to 100 μl of sample. The sample was then incubated at room temperature (RT) for 5 min. Beads were pelleted using a magnetic particle concentrator (MPC) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, South San Francisco, CA, USA) until liquid was clear. The supernatant was removed and transferred to a new tube. AMPure XP (30 μl) beads were then added for the second bead size selection. The mixture was pulse vortexed, quickly spun and incubated at RT for 5 min. Beads were pelleted using an MPC until liquid was clear. The supernatant was then discarded without disturbing the beads and 200 μl of freshly prepared 75% ethanol (EtOH) was added, followed by a 30 s incubation to wash the beads. EtOH was discarded before the EtOH wash step was repeated twice. Afterwards, the sample was placed on a thermocycler (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) with the lid open and incubated at 37 °C until the beads were dry and residual EtOH had evaporated. The beads were re-suspended in 53 μl of EB buffer (Qiagen, Redwood City, CA, USA), vortexed, quickly spun and incubated at RT for 1 min. Beads were pelleted using an MPC until liquid was clear and then 50 μl of supernatant was transferred to a new tube. The fragments were treated with the Kapa Library Preparation Kit ORIGIN (Kapa Biosystems, Wilmington, MA, USA) for the following steps: For end-repair 26 μl MilliQ water, 9 μl 10X End Repair Buffer, and 5 μl End Repair Enzyme were combined in a 1.5 ml tube. The cocktail was vortexed and quickly spun, stored on ice, and then 40 μl was added to the 50 μl DNA sample. The mixture was vortexed and quickly spun, before incubation at 30 °C for 30 min in a thermocycler (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). After incubation, 126 μl of AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) were added to 90 μl of End Repair sample, pulse vortexed, quickly spun, and incubated at RT for 5 min. Beads were pelleted using an MPC until liquid was clear. The supernatant was then discarded without disturbing the beads. The beads were washed twice with 200 μl of freshly prepared 75% EtOH with an incubation time of 30 s. After washing, the sample was incubated at 37 °C in a thermocycler with the lid open until residual EtOH had evaporated. For DNA resuspension, 17.5 μl of EB buffer was added. The sample was vortexed, quickly spun, and incubated at RT for 1 min, before beads were pelleted on an MPC. 15 μl of supernatant was then transferred to a new tube.

For A-tailing, 9 μl of MilliQ water, 3 μl of 10X A-Tailing Buffer and 3 μl of A-Tailing Enzyme were combined in this order in a 1.5 ml tube. The cocktail was vortexed and quickly spun, then 15 μl of the A-Tailing cocktail was added to the 15 μl sample. The mixture was vortexed and quickly spun before incubating the samples in a thermocycler at 30 °C for 30 min, followed by 5 min at 70 °C.

Adapter ligation was performed immediately thereafter: 9 μl of 5X Ligation Buffer and 5 μl of ligase were combined in a 1.5 ml tube. The mixture was pulse vortexed and quickly spun before adding 14 μl of adapter ligation cocktail to the 30 μl sample; 1 μl of 18 μM adapter was then added to the ligation mixture for a final concentration of 400 nM. The mixture was incubated in a thermocycler at 20 °C for 15 min. After adapter ligation, 5 μl of EB Buffer was added to 45 μl of adapter-ligated sample. The sample was size-selected and washed twice with 45 μl of AMPure XP beads as described previously. After the first clean-up step, the sample was resuspended with 52 μl of EB Buffer and 45 μl of supernatant was transferred to a clean tube. After the second clean-up step, the sample was eluted with 25 μl of EB Buffer and 23 μl of supernatant was transferred to a clean tube. The sample was quality-controlled and quantified using an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 High Sensitivity Kit.

The prepared Illumina library was further quantified using KAPA Biosystem’s next generation sequencing library qPCR kit (Roche Holding AG, Basel, Switzerland) and run on a Roche Light Cycler 480 real-time PCR instrument according to the manufacturer’s guidelines (Roche Holding AG, Basel, Switzerland). The quantified library was then prepared for sequencing on the Illumina HiSeq sequencing platform (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). First, the TruSeq paired-end cluster kit, v3, and Illumina’s cBot instrument were used to generate a clustered flowcell for sequencing (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Sequencing of the flowcell was performed on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 sequencer using a TruSeq SBS sequencing kit 200 cycles, v4, following a 2 × 150 indexed run recipe (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) (Table 2). This resulted in 426,735,646 raw reads.

For PacBio library creation, an unamplified library was generated using Pacific Biosciences standard template preparation protocol for creating >10 kb libraries. gDNA (10 μg) was sheared using Covaris g-Tubes to generate >10 kb fragments (Covaris, Inc., Woburn, MA, USA). The sheared DNA fragments were then prepared according to the Pacific Biosciences SMRTbell template preparation kit guidelines (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA). Briefly, DNA fragments were treated with DNA damage repair mix, end-repaired, and 5′ phosphorylated. PacBio hairpin adapters were then ligated to the fragments to create SMRTbell templates for sequencing. The SMRTbell templates were purified using exonuclease treatments and size-selected using the Sage Science BluePippin instrument with a 10 kb lower cutoff depending on DNA quality.

PacBio sequencing primers were annealed and v. P6 sequencing polymerase was bound to the SMRTbell templates. The prepared SMRTbell template libraries were then sequenced on a Pacific Biosciences RSII sequencer using v. C4 chemistry and 1 × 240 min sequencing movie run times (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA).

For the size-selected ONT library, 10 µg of gDNA was used and quality controlled using FA12 DNA QC. The DNA was sheared using Covaris g-Tubes to generate >10 kb fragments (Covaris, Inc., Woburn, Ma, USA). The sheared DNA fragments were then size selected using the Sage Science BluePippin instrument with a 10 kb lower cutoff. After clean-up, DNA was repaired and end-prepared using the NEBNext FFPE DNA Repair kit (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) with the following changes to the manufacturer’s protocol: The reaction volume was doubled to 120 µl, incubation was performed at 20 °C for 20 minutes and at 65 °C for 20 minutes. AMPure XP beads (120 µl) were added to the repaired DNA and incubated at RT for 30 minutes on a Hula mixer, followed by two washes with 70% EtOH. Beads were then resuspended with 61 µl of nuclease-free (NF) water and incubated at RT for 30 minutes on a Hula mixer; 61 µl of the eluate was then transferred into a clean 1.5 ml Eppendorf tube. The resulting DNA was quantified using the Qubit HS DNA kit.

Adapter ligation and clean-up was performed using the Ligation Sequencing Kit SQK-LSK109 (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, United Kingdom) with a slightly changed protocol: Ligation buffer, NEBNext Quick T4 DNA ligase, and adapter mix were added to the repaired DNA and incubated at RT for 10 minutes and then overnight at 4 °C. The ligated sample was purified using 100 µl of AMPure XP beads during a 30 minute incubation at RT on the Hula mixer, two bead washing steps using the kit-provided wash buffer and resuspension of the beads in 40 µl of elution buffer at RT for 30 minutes on the Hula mixer; 40 µl of the eluate was then transferred into a clean 1.5 ml tube.

The library was then sequenced on a MinION using R9.4.1 flow cell sequencing chemistry (Table 2). This resulted in 187,507 Pass-1D reads that were processed using the MinKNOW software version 1.13.1.

For the non-size-selected ONT library, 5 μg of gDNA was used to create the ONT library. The DNA was sheared using Covaris g-tubes to generate >10 kb fragments (Covaris Inc., Woburn, MA USA). The sheared DNA was repaired using the NEBNext FFPE Repair Mix (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. AMPure XP beads (62 μl) were added to the FFPE-repair reaction and incubated at RT for 30 minutes on a Hula mixer, followed by two washes with 70% EtOH. Beads were then resuspended with 93 μl of NF water and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature on a Hula mixer; 90 μl of the eluate was then transferred to a clean 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube. The resulting DNA was quantified using the Qubit HS DNA kit.

The fragmented and repaired DNA underwent end repair and A-tailing using the NEBNExt End Repair/dA-Tailing Module (New England BioLabs) with the following changes to the manufacturer’s protocol: The reaction volume was doubled to 120 μl, incubation was performed at 20 °C for 20 minutes and at 65 °C for 20 minutes. AMPure XP beads (120 μl) were added to the end-prep reaction and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature on a Hula mixer, followed by two washes with 70% EtOH. Beads were then resuspended in 31 ul of NF water and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature on a Hula mixer; 61 μl of the eluate was then transferred to a clean 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube. The resulting DNA was quantified using the Qubit HS DNA kit.

Adapter ligation and clean-up was performed using the SQK-LSK108 kit (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Oxford, United Kingdom) with the following changes to the manufacturer’s protocol: The ligation reaction was incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes and then overnight at 4 °C. The ligated samples were purified using 40 μl of AMPure XP beads, incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature on a Hula mixer followed by two washes using the kit-provided wash buffer. The beads were resuspended in 15 μl of the kit-provided elution buffer and then incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature on a Hula mixer; 15 μl of the eluate was then transferred to a clean 1.5 mL tube and quantified using the Qubit HS DNA kit.

The library was then sequenced on a MinION using the R9.4 flow cell sequencing chemistry and resulted in 144,976 reads.

Sequence QC

BBDuk (filterk = 27 trimk = 27; https://sourceforge.net/projects/bbmap/) was used to remove Illumina adapters, known Illumina artifacts, and phiX, and to quality-trim both ends to Q12 from the Illumina library. Reads were discarded if they contained more than one ‘N’, or had quality scores (before trimming) averaging less than 8 over the read, or had a length under 40 bp after trimming. The remaining reads were mapped to a masked version of human HG19, dog, cat, and mouse with BBMap (https://sourceforge.net/projects/bbmap/), discarding all hits over 93% identity. This process yielded 422,896,888 filtered reads (Table 2). Quality filtering of PacBio sequences were performed using SMRT Portal v2.3.0, setting minimum subread length to 50, minimum polymerase read quality to 75, minimum polymerase read length to 50, and control spike-in was removed using pbalign with parameters minAccuracy = 0.75 minLength = 50. Filtering yielded 389,806 subreads. ONT basecalling was performed using Albacore basecaller v2.3.1 selecting only the pass-1D reads.

Read Mapping and repeat region identification

Illumina, PacBio, and ONT reads were mapped to reference genomes using bwa v0.7.15 (http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/) with default parameters for Illumina. Parameters -x pacbio and -x ont2d were specified for PacBio and ONT reads, respectively. The number of reads that mapped to Micromonospora coxensis was negligible. The distribution of reads that mapped to each organism, as well as numbers of reads that did not map to any organism, are given in Table S1. Reference sequences were downloaded from IMG on June 27, 2017. IMG IDs for references are listed in Table 1. Repeats in genomes were found using repeat-match tool from MUMmer package v3.2363, specifying parameter -n25.

Assembly and assembly quality assessment

For the assembly, we first performed error correction on Illumina reads using bfc version r181 with parameters -1 -s 10 g -k 21 -t 1064. Unpaired reads were removed from the library subsequently. Error-corrected reads were then assembled using SPAdes v3.12.065 with parameters -m 120 –only-assembler -k 33,55,77,99,127 –meta. For the hybrid assemblies, ONT and PacBio reads were supplied to the assembler via–nanopore and–pacbio parameters. Long reads were not error corrected as recommended in the SPAdes manual. Assembly statistics were generated using metaquast from Quast 4.6.366 package using default parameters.

Data post-processing

Depth of coverage plots in Figs. 3 and S7 were produced using bedtools genomecov67. Illumina insert size distribution in Fig. S6 was obtained using picard CollectInsertSizeMetrics68. We used jgi_summarize_bam_contig_depths (bitbucket.org/berkeleylab/metabat) with parameter–percentIdentity 70 to produce GC coverage plots in Fig. S8. Percent identity distributions in Figs. S3, S4, error rates in Fig. S9, and distributions in Fig. S10 were generated using jgi_summarize_bam_contig_depths (bitbucket.org/berkeleylab/metabat). Figures S11 and S12 were produced from Metaquast output.

The bash scripts used for QC, mapping, assembly and post-processing are available at https://bitbucket.org/volkansevim/bmock12/src/master/.

Data Records

Shotgun sequences generated on the Illumina, ONT, and PacBio platforms are publicly available through NCBI and details are listed in Supplementary Table 6: SRA Accessions SRX516198569 (ONT no size selection), SRX490158670 (ONT 10 kb size selection), SRX490158471 & SRX490158572 (PacBio 10 kb size selection; two libraries were combined for analysis), SRX490158373 (Illumina). Assemblies have been deposited at NCBI Assembly under the accessions GCA_003957615.174 (PacBio + Illumina hybrid), GCA_003957625.175 (ONT + Illumina hybrid), and GCA_003957645.176 (Illumina only).

Technical Validation

To assess the quality of genomic DNA received, we used the PicoGreen assay and the Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Each sample was quantified in quadruplicate.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the help of Gabi Poetter, DSMZ, for growing cells of DSM 43904, DSM 43913 and DSM 45161 and of Meike Doeppner, DSMZ, for DNA extraction and quality control. Work conducted at LLNL was performed under DOE Award SCW1039 and Contract No. DE-AC52-07NA27344. This work was conducted by the U.S. Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute, a DOE Office of Science User Facility, and was supported under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231.

Author contributions

R.C.E., A.M.D., B.M.B., M.G., A.M., S.R.L., H.-P.K. grew various isolates and extracted the DNA. Ja.L. created the mock community pool. Ju.L., H.H., R.O., M.Z. and C.D. generated the sequence data. V.S., R.E. and A.C. performed Q.C., read mapping and submitted the sequence data to the database. V.S. created the Figures and Tables. E.S., V.S. and T.W. wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Esther Singer, Email: esinger@lbl.gov.

Tanja Woyke, Email: twoyke@lbl.gov.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41597-019-0287-z.

References

- 1.Roberts RJ, Carneiro MO, Schatz MC. The advantages of SMRT sequencing. Genome Biology. 2013;14:405. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-6-405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minoche AE, Dohm JC, Himmelbauer H. Evaluation of genomic high-throughput sequencing data generated on Illumina HiSeq and genome analyzer systems. Genome Biology. 2011;12:R112. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-11-r112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laver T, et al. Assessing the performance of the Oxford Nanopore Technologies MinION. Biomolecular Detection and Quantification. 2015;3:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bdq.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kasianowicz JJ, Brandin E, Branton D, Deamer DW. Characterization of individual polynucleotide molecules using a membrane channel. PNAS. 1996;93:13770–13773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kilianski, A. et al. Bacterial and viral identification and differentiation by amplicon sequencing on the MinION nanopore sequencer. GigaSci4(12), 10.1186/s13742-015-0051-z (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Karamitros T, Magiorkinis G. A novel method for the multiplexed target enrichment of MinION next generation sequencing libraries using PCR-generated baits. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e152. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sauvage Virginie, Boizeau Laure, Candotti Daniel, Vandenbogaert Mathias, Servant-Delmas Annabelle, Caro Valérie, Laperche Syria. Early MinION™ nanopore single-molecule sequencing technology enables the characterization of hepatitis B virus genetic complexity in clinical samples. PLOS ONE. 2018;13(3):e0194366. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mikheyev AS, Tin MMY. A first look at the Oxford Nanopore MinION sequencer. Molecular Ecology Resources. 2014;14:1097–1102. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Theuns, S. et al. Nanopore sequencing as a revolutionary diagnostic tool for porcine viral enteric disease complexes identifies porcine kobuvirus as an important enteric virus. Sci Rep8 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Yamagishi, J. et al. Serotyping dengue virus with isothermal amplification and a portable sequencer. Sci Rep7 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Wang, J., Moore, N. E., Deng, Y.-M., Eccles, D. A. & Hall, R. J. MinION nanopore sequencing of an influenza genome. Front. Microbiol. 6 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Quick J, et al. Real-time, portable genome sequencing for Ebola surveillance. Nature. 2016;530:228–232. doi: 10.1038/nature16996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loman NJ, Quick J, Simpson JT. A complete bacterial genome assembled de novo using only nanopore sequencing data. Nature Methods. 2015;12:733–735. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li, C. et al. INC-Seq: accurate single molecule reads using nanopore sequencing. Gigascience5 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Quick J, Quinlan AR, Loman NJ. A reference bacterial genome dataset generated on the MinIONTM portable single-molecule nanopore sequencer. GigaScience. 2014;3:22. doi: 10.1186/2047-217X-3-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ashton PM, et al. MinION nanopore sequencing identifies the position and structure of a bacterial antibiotic resistance island. Nature Biotechnology. 2015;33:296–300. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ip Camilla L.C., Loose Matthew, Tyson John R., de Cesare Mariateresa, Brown Bonnie L., Jain Miten, Leggett Richard M., Eccles David A., Zalunin Vadim, Urban John M., Piazza Paolo, Bowden Rory J., Paten Benedict, Mwaigwisya Solomon, Batty Elizabeth M., Simpson Jared T., Snutch Terrance P., Birney Ewan, Buck David, Goodwin Sara, Jansen Hans J., O'Grady Justin, Olsen Hugh E. MinION Analysis and Reference Consortium: Phase 1 data release and analysis. F1000Research. 2015;4:1075. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.7201.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deschamps, S. et al. Characterization, correction and de novo assembly of an Oxford Nanopore genomic dataset from Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Scientific reports6, 28625 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Mitsuhashi, S. et al. A portable system for rapid bacterial composition analysis using a nanopore-based sequencer and laptop computer. Scientific reports7(1), 5657 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Xia, Y. et al. MinION Nanopore Sequencing Enables Correlation between Resistome Phenotype and Genotype of Coliform Bacteria in Municipal Sewage. Frontiers in microbiology8, 2105 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Judge K, Harris SR, Reuter S, Parkhill J, Peacock SJ. Early insights into the potential of the Oxford Nanopore MinION for the detection of antimicrobial resistance genes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:2775–2778. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Votintseva AA, et al. Same-Day Diagnostic and Surveillance Data for Tuberculosis via Whole-Genome Sequencing of Direct Respiratory Samples. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55:1285–1298. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02483-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hyeon, J.-Y. et al. Quasimetagenomics-Based and Real-Time-Sequencing-Aided Detection and Subtyping of Salmonella enterica from Food Samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.84(4), e02340-17 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Hu J, et al. Diversified Microbiota of Meconium Is Affected by Maternal Diabetes Status. PloS one. 2013;8:e78257. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lemon JK, Khil PP, Frank KM, Dekker JP. Rapid Nanopore Sequencing of Plasmids and Resistance Gene Detection in Clinical Isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55:3530–3543. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01069-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanderson MA, Adler PR, Boateng AA, Casler MD, Sarath G. Switchgrass as a biofuels feedstock in the USA. Canadian Journal of Plant Science. 2006;86:1315–1325. doi: 10.4141/P06-136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quainoo S, et al. Whole-Genome Sequencing of Bacterial Pathogens: the Future of Nosocomial Outbreak Analysis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017;30:1015–1063. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00016-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quick, J. et al. Rapid draft sequencing and real-time nanopore sequencing in a hospital outbreak of Salmonella. Genome Biol16(1), 114 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Fraiture, M.-A. et al. Nanopore sequencing technology: a new route for the fast detection of unauthorized GMO. Scientific reports8(1), 7903 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Goodwin S, et al. Oxford Nanopore sequencing, hybrid error correction, and de novo assembly of a eukaryotic genome. Genome Res. 2015;25:1750–1756. doi: 10.1101/gr.191395.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Norris AL, Workman RE, Fan Y, Eshleman JR, Timp W. Nanopore sequencing detects structural variants in cancer. Cancer Biology & Therapy. 2016;17:246–253. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2016.1139236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoang PNT, et al. Generating a high-confidence reference genome map of the Greater Duckweed by integration of cytogenomic, optical mapping and Oxford Nanopore technologies. The Plant Journal. 2018;96:670–684. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tyson JR, et al. MinION-based long-read sequencing and assembly extends the Caenorhabditis elegans reference genome. Genome Res. 2018;28:266–274. doi: 10.1101/gr.221184.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wei, X., Shao, M., Gale, W. & Li, L. Global pattern of soil carbon losses due to the conversion of forests to agricultural land. Scientific reports4, 4062 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Pomerantz, A. et al. Real-time DNA barcoding in a rainforest using nanopore sequencing: opportunities for rapid biodiversity assessments and local capacity building. GigaScience7(4), giy033 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Runtuwene, L. R. et al. Nanopore sequencing of drug-resistance-associated genes in malaria parasites, Plasmodium falciparum. Scientific reports8(1), 8286 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Hargreaves, A. D. & Mulley, J. F. Assessing the utility of the Oxford Nanopore MinION for snake venom gland cDNA sequencing. PeerJ3, e1441 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Zaaijer, S. & Erlich, Y. Using mobile sequencers in an academic classroom. eLife5 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Lindberg Michael R., Schmedes Sarah E., Hewitt F. Curtis, Haas Jamie L., Ternus Krista L., Kadavy Dana R., Budowle Bruce. A Comparison and Integration of MiSeq and MinION Platforms for Sequencing Single Source and Mixed Mitochondrial Genomes. PLOS ONE. 2016;11(12):e0167600. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jain M, et al. Nanopore sequencing and assembly of a human genome with ultra-long reads. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36:338–345. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jansen, H. J. et al. Rapid de novo assembly of the European eel genome from nanopore sequencing reads. Scientific reports7(1), 7213 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Liem, M. et al. De novo whole-genome assembly of a wild type yeast isolate using nanopore sequencing. F1000Research6 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Volden R, et al. Improving nanopore read accuracy with the R2C2 method enables the sequencing of highly multiplexed full-length single-cell cDNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:9726–9731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1806447115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parker, J., Helmstetter, A. J., Devey, D., Wilkinson, T. & Papadopulos, A. S. T. Field-based species identification of closely-related plants using real-time nanopore sequencing. Scientific reports7(1), 8345 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Laver T, et al. Assessing the performance of the Oxford Nanopore Technologies MinION. Biomolecular Detection and Quantification. 2015;3:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bdq.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hu, Y. O. O. et al. Stationary and portable sequencing-based approaches for tracing wastewater contamination in urban stormwater systems. Scientific reports8(1), 11907 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Brown BL, Watson M, Minot SS, Rivera MC, Franklin RB. MinIONTM nanopore sequencing of environmental metagenomes: a synthetic approach. Gigascience. 2017;6:1–10. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/gix007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nakayama, Y., Yamaguchi, H., Einaga, N. & Esumi, M. Pitfalls of DNA Quantification Using DNA-Binding Fluorescent Dyes and Suggested Solutions. PLoS One11(3), e0150528 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Ardui S, Ameur A, Vermeesch JR, Hestand MS. Single molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing comes of age: applications and utilities for medical diagnostics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:2159–2168. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dohm JC, Lottaz C, Borodina T, Himmelbauer H. Substantial biases in ultra-short read data sets from high-throughput DNA sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:e105. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bentley DR, et al. Accurate whole human genome sequencing using reversible terminator chemistry. Nature. 2008;456:53–59. doi: 10.1038/nature07517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hillier LW, et al. Whole-genome sequencing and variant discovery in C. elegans. Nature Methods. 2008;5:183–188. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sczyrba A, et al. Critical Assessment of Metagenome Interpretation—a benchmark of metagenomics software. Nature Methods. 2017;14:1063–1071. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Singer E, et al. Next generation sequencing data of a defined microbial mock community. Scientific Data. 2016;3:160081. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2016.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Consortium THMP. A framework for human microbiome research. Nature. 2012;486:215–221. doi: 10.1038/nature11209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bowers, R. M. et al. Impact of library preparation protocols and template quantity on the metagenomic reconstruction of a mock microbial community. BMC Genomics16(1), 856 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Singer E, et al. High-resolution phylogenetic microbial community profiling. The ISME Journal. 2016;10:2020–2032. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bushnell B, Rood J, Singer E. BBMerge – Accurate paired shotgun read merging via overlap. PloS one. 2017;12:e0185056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cole, J. K. et al. Phototrophic biofilm assembly in microbial-mat-derived unicyanobacterial consortia: model systems for the study of autotroph-heterotroph interactions. Front. Microbiol. 5 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Moore, D. D. & Dowhan, D. Preparation and Analysis of DNA. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology (1995).

- 61.Hanada S, Hiraishi A, Shimada K, Matsuura K. Chloroflexus aggregans sp. nov., a Filamentous Phototrophic Bacterium Which Forms Dense Cell Aggregates by Active Gliding Movement. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 1995;45:676–681. doi: 10.1099/00207713-45-4-676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ausubel, F. M. et al. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. 1 (John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 1994).

- 63.Kurtz S, et al. Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biology. 2004;5:R12. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-2-r12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li H. BFC: correcting Illumina sequencing errors. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:2885–2887. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bankevich A, et al. SPAdes: A New Genome Assembly Algorithm and Its Applications to Single-Cell Sequencing. Journal of Computational Biology. 2012;19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gurevich A, Saveliev V, Vyahhi N, Tesler G. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:1072–1075. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Quinlan Aaron R. BEDTools: The Swiss-Army Tool for Genome Feature Analysis. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics. 2014;47(1):11.12.1-11.12.34. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1112s47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Broad Institute. Picard Toolkit. http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/; (GitHub Repository Broad Institute, 2019).

- 69.2019. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRX5161985

- 70.2019. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRX4901586

- 71.2019. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRX4901584

- 72.2019. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRX4901585

- 73.2019. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRX4901583

- 74.Sevim V, 2019. GenBank. RKMI00000000

- 75.Sevim V, 2019. GenBank. RKMJ00000000

- 76.Sevim V, 2019. GenBank. RJWC00000000

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- 2019. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRX5161985

- 2019. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRX4901586

- 2019. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRX4901584

- 2019. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRX4901585

- 2019. NCBI Sequence Read Archive. SRX4901583

- Sevim V, 2019. GenBank. RKMI00000000

- Sevim V, 2019. GenBank. RKMJ00000000

- Sevim V, 2019. GenBank. RJWC00000000