Abstract

There is substantial evidence that chronic heart failure in humans and in animal models is associated with inflammation. Ischemic interventions such as myocardial infarction lead to necrotic cell death and release of damage associated molecular patterns, factors that signal cell damage and induce expression of proinflammatory chemokines and cytokines. It has recently become evident that nonischemic interventions are also associated with increases in inflammatory genes and immune cell accumulation in the heart and that these contribute to fibrosis and ventricular dysfunction. How proinflammatory responses are elicited in nonischemic heart disease which is not, at least initially, associated with cell death is a critical unanswered question. In this review we provide evidence supporting the hypothesis that cardiomyocytes are an initiating site of inflammatory gene expression in response to nonischemic stress. Furthermore we discuss the role of the multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-regulated kinase, CaMKIIδ, as a transducer of stress signals to nuclear factor-κB activation, expression of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, and priming and activation of the NOD-like pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome in cardiomyocytes. We summarize recent evidence that subsequent macrophage recruitment, fibrosis and contractile dysfunction induced by angiotensin II infusion or transverse aortic constriction are ameliorated by blockade of CaMKII, of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1/C-C chemokine receptor type 2 signaling, or of NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

Keywords: CaMKII, DAMPs, inflammasome, macrophages

INTRODUCTION

Inflammation and Heart Failure

Heart failure remains a leading cause of death despite decades of research and improved therapeutics. Cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, fibrosis, and contractile dysfunction are well known phenotypic changes seen in the failing heart. Cardiac inflammation is also evident in the failing heart (3, 17, 28, 96) and is increased with aging (65, 89). Inflammation is considered to be a driver of the adverse remodeling that occurs in response to acute myocardial infarction (MI) (25, 128). MI and other ischemic interventions lead to necrotic cell death and current thinking, supported by considerable research, is that necrotic cells release factors that signal cell damage. These signals, referred to as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), activate Toll-like receptors (TLRs) including TLR4 to elicit NF-κB signaling and induce expression of proinflammatory chemokines and cytokines, which in turn recruit neutrophils, macrophages, and T cells. While initially serving a salutary function in preventing further tissue damage this process, when sustained, leads to chronic inflammation. Chronic inflammation appears to be causally related to changes in the extracellular matrix, fibrosis and development of contractile dysfunction. Nonetheless most clinical trials using anti-inflammatory drugs have failed to prevent heart failure (17, 38, 81, 91, 120). A primary example is the randomized placebo-controlled trials using etanercept (TNF-α inhibition) in patients with chronic heart failure, which failed to demonstrate any beneficial effect (91). In another study, treatment of patients with chronic viral cardiomyopathy with interferon-β-1b improved New York Heart Association functional class but did not significantly improve echocardiographic and hemodynamic parameters (99). Useful tables summarizing clinical trials targeting inflammatory pathways and immune-modulatory therapies are included in recent reviews by Riehle and Bauersachs (91) and by Ong et al. (81). A possible reason that anti-inflammatory treatment fails to be effective when used at advanced stages of heart failure is that a complex cascade of immune cell responses, generating multiple proinflammatory mediators, has been engaged. Gaining more insight into the specific immune cell types responsible for sustaining inflammation at later stages of heart failure, and understanding what controls their activation and what they secrete, holds promise for improving anti-inflammatory therapeutics in heart failure.

Renewed interest in the potential efficacy of anti-inflammatory therapy was sparked by the results of the recently published CANTOS trial in which a significant decrease in adverse cardiac events was observed in patients treated with canakinumab to block signaling by the potent cytokine IL-1β (90), as was a decrease in rehospitalization of patients with heart failure (27). A separate trial (REDHART) using anakinra, an inhibitor of the IL-1 receptor, reported improved cardiac performance in patients with decompensated systolic HF (121). These inhibitors antagonize responses to mediators generated through the NLRP3 inflammasome suggesting that the inflammasome plays a central role in both initiating and sustaining cardiac inflammation.

In this review, we discuss recent progress in our understanding of the molecular mechanisms by which cardiac inflammatory signals are generated and the inflammasome is activated. We focus on the poorly appreciated role of cardiac inflammation in initiating adverse cardiac remodeling in response to nonischemic stress such as pressure overload, isoproterenol and angiotensin II (ANG II). Achieving a broader understanding of the sites and mechanisms that trigger cardiac inflammation has implications for the improved development of therapeutic regimens to limit cardiac remodeling.

HOW IS INFLAMMATION INITIATED IN ISCHEMIC HEART DISEASE?

Cell Death and DAMPs

The notion that the immune system is concerned with responding to “danger” or “damage” in addition to distinguishing between self and nonself was first proposed in the 1990s (70), and it is now well accepted that inflammation can occur in the absence of an exogenous pathogen. This “sterile” form of inflammation can be triggered by endogenous signals, produced in response to stressors, an example of which is MI. In the context of MI, cardiomyocytes release DAMPs such as HMGB1, double-stranded DNA and ATP (2, 50, 98, 142). The receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) and TLR1, -2, -4, -5, and -6 located on the plasma membrane of cells including immune cells, fibroblasts and cardiomyocytes respond to extracellular DAMPs. Toll like receptors localized on endosomal and lysosomal membranes (TLR3, -7, -8, and -9) recognize DAMPs such as mitochondrial DNA (mitoDNA) (66, 80, 117).

TLR4, the most highly expressed TLR in the heart, was originally recognized as a receptor for LPS (67). TLR4 plays a critical role in innate immune responses but is also one of the best examined DAMP receptors. TLR4 has many reported ligands including saturated fatty acids, serum amyloid A, tenascin C, fibrinogen, S100A8/9, S100A1, FN-EDA, HMGB1, and heat shock proteins (HSPs) (117). Global TLR4-deficient mice sustain smaller infarctions and exhibit less inflammation after myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury (82) and in another study TLR4 deficiency was shown to reduce the extent of left ventricular (LV) dilation and systolic dysfunction as well as reducing interstitial fibrosis in the noninfarcted area (108). HMGB1, a highly conserved nonhistone nuclear protein, is released from necrotic cells and induces inflammatory responses through its binding to TLR4 and RAGE. Indeed, HMGB1 inhibition also provides cardioprotection against ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) and this protection is diminished in RAGE KO mice (2). Together, these findings support the idea that DAMPs elicit inflammatory responses through their binding to TLRs and RAGE and thereby contribute to ischemic cardiac injury.

Stimulation of TLRs by DAMPs activates NF-κB, a master regulator of inflammatory gene expression. NF-κB transcriptionally upregulates expression of cytokines and chemokines, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1/CCL2). NF-κB signaling also increases mRNA for NLRP3, as well as for the precursor forms of IL-1β and IL-18, which are processed to their mature forms by subsequent activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. All of these cytokines and chemokines serve to drive the ensuing recruitment of immune cells to the heart, a process that further enhances production of proinflammatory mediators, culminating in adverse cardiac remodeling (25, 62).

Monocyte/Macrophage and T-Cell Recruitment

Extensive studies originating in the laboratories of Doug Mann and Matthias Nahrendorf have characterized the origins and fate of cardiac macrophages and the populations of cells that respond to ischemic injury (24, 37, 55, 73, 74). Macrophages are the primary immune cells that reside in the heart under physiological conditions. Resident macrophages are established embryonically and are derived from yolk sac and fetal liver progenitors (24). The primary cardiac resident macrophages, which are characterized as Ly6Clow, CD11clow, and CCR2−, are renewed through in situ proliferation independent of blood monocyte recruitment (24). In MI, as indicated above, proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines are generated through the actions of DAMPs released from dying cells and these lead to recruitment of neutrophils and monocytes to the heart. The monocytes that infiltrate the infarcted myocardium are CCR2+, Ly6Chigh and these become the dominant macrophages in the heart (6, 37, 74, 107). The CCR2+ macrophages further contribute to generation of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines, which play a key role in adverse cardiac remodeling and heart failure pathogenesis in response to MI in both rodent and human heart (7, 40, 102, 107). Specific subsets of macrophages also produce proresolving mediators, which contribute to the resolution of inflammation in the infarcted myocardium (32). Single cell RNA-seq analysis has recently been used to reveal subsets of macrophages that are clearly linked to the development of inflammation and its sequelae following MI (50). Analysis by single cell RNA-seq is a powerful tool to identify distinct populations of immune cells not evident in analysis of immune cell populations using standard cell markers in flow cytometry.

In ischemic heart disease induced by MI CD25+CD4+ FoxP3 regulatory T cells (Tregs), a specific subset of lymphocytes, infiltrate the heart and play a role in wound healing, reducing infarct size and preventing LV remodeling (18, 41, 81, 125). Recent studies indicate that at later stages Tregs become dysfunctional, taking on proinflammatory and anti-angiogenic properties (9). Another subset of T cells, termed T-helper (Th) cells, also expand in the spleen and migrate to the heart during development of ischemic heart failure, with Th17 and Th2 subsets contributing to the progression to heart failure (12).

CALCIUM CALMODULIN-DEPENDENT PROTEIN KINASE REGULATION AND FUNCTION

Calcium calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMKII) is a serine threonine kinase that is initially activated by binding of calcium liganded calmodulin to a pseudosubstrate region in the CaMKII regulatory domain. This event frees the enzyme from inhibitory constraint, increasing its catalytic activity and allowing posttranslational modifications that generate “autonomously active” forms of the enzyme, which no longer require elevated calcium (1). The best known posttranslational modification is autophosphorylation at Thr 286/287 (the precise numbering varies according to isoform). Subsequent studies led to the discovery that CaMKII can also be oxidized at methionine residues 281 and 282 leading to its activation and notably this was observed in cardiomyocytes and in the mouse heart in response to ANG II (26).

CaMKIIδ is the predominant isoform in the mammalian heart. We showed that CaMKII is activated rapidly in response to pressure overload (106, 141) and other studies indicate that it remains active during development of heart failure (16, 52, 105). Notably, however, our work and that of others demonstrated that CaMKIIδ is not required for development of pathological hypertrophy, but instead for the progression from hypertrophy to heart failure (31, 51, 61, 127). Transgenic mice with cardiomyocyte CaMKIIδ overexpression develop heart failure, which is not rescued by normalizing sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium handling, blocking β-adrenergic receptors or inhibiting the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (16, 23, 42, 140), suggesting an as yet undefined pathway by which CaMKIIδ activation mediates progression to heart failure. Studies discussed in this review, in the context of broader work in this area, suggest that activation of CaMKIIδ is the mechanism by which nonischemic stresses, including ANG II and transverse aortic constriction (TAC), lead to cardiac inflammation and that this is a key step in development of fibrosis and adverse remodeling in response to these interventions.

INFLAMMATION IN RESPONSE TO ANG II INFUSION

The clinical efficacy of inhibitors of ANG II synthesis and antagonists of ANG II type I (AT1) receptors in the treatment/prevention of heart failure provides clear support for the notion that the renin-angiotensin system is a major contributor to the progression to heart failure and diastolic dysfunction in humans (100). Evidence that the heart can locally generate angiotensin led to the postulate that beyond the well-recognized effects of ANG II on the vasculature, there is also a cardiac tissue-localized, renin-angiotensin system that plays a pathophysiological role in the heart (22, 100). Indeed the ability of ANG II to induce robust cardiac inflammation can be dissociated from the hypertensive effects of ANG II (110, 129). Locally generated ANG II acts on the G protein-coupled AT1 receptors on cardiomyocytes to transduce a variety of signals that induce cardiomyocyte hypertrophy (4, 138). Infusion of ANG II is now commonly used as an in vivo model for inducing cardiac hypertrophy, inflammation and fibrosis in mice (34, 129).

Cardiac fibroblasts also express AT1 receptors and it is generally thought that direct actions of ANG II on these receptors lead to the conversion of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts and subsequent development of fibrosis (11, 56). However it is increasingly accepted that cardiac inflammatory responses play a central role in development of fibrosis and adverse remodeling (33, 53) accordingly the inflammatory component of ANG II signaling would also be critical to its ability to induce these responses. In this regard it is notable that inflammatory gene expression in response to ANG II infusion increases rapidly, preceding fibrotic gene upregulation (110, 129). Thus local proinflammatory responses mediated through effects of ANG II on cardiac myocytes, fibroblasts or other cardiac cells appears to be the initiating step leading to recruitment of monocytes/macrophages and associated inflammatory responses that predispose to development of fibrosis, adverse cardiac remodeling and heart failure.

Considerable work from the Entman laboratory examined pathways by which ANG II infusion leads to inflammatory and fibrotic responses (20, 34, 133). Specifically they demonstrated that MCP-1 is generated in the heart in response to ANG II infusion. Using a global MCP-1 knockout (KO) mouse, they showed that MCP-1 signaling is required for the increased appearance of bone marrow-derived monocytic CD34+/CD45+ cells in the heart following ANG II infusion (133). More detailed flow cytometric analysis by the Mann laboratory (24) examined cardiac monocytes and macrophages at steady state and in response to cardiac stressors including ANG II. They demonstrated the rapid influx of Ly6Chigh monocytes in response to ANG II infusion, which subsequently expanded into multiple cardiac macrophage populations. Notably the monocytes that they observed to be recruited to the heart at early times of ANG II infusion were also positive for CCR2, the receptor for MCP-1. CCR2+ macrophages produce high amounts of TNF-α as well as IL-1β, consistent with a proinflammatory phenotype (24). These findings implicate MCP-1 in recruiting CCR2+ monocytes that subsequently expand into a pool of proinflammatory cardiac macrophages. Our recent studies confirmed this concept, demonstrating that the recruitment of CD68 macrophages to the heart at 1 day of ANG II infusion, as well as fibrosis observed at 3 days ANG II, were inhibited by pharmacological blockade of the CCR2 receptor with RS102895 (129).

Mechanistically, ANG II-induced cardiac inflammation and fibrosis are initiated through activation of NF-κB. This is evidenced by loss of ANG II-induced increases in proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (IL-1β, IL-6, and MCP-1/CCL2) and fibrotic genes (collagen, fibronectin) in knock-in mice in which NF-κB signaling is inhibited (134). Our recent studies demonstrated that NF-κB activation in response to ANG II occurs in the heart within 3 h of ANG II infusion, and showed that pharmacological inhibition of NF-κB activation with BMS-345541 virtually abolished the increases in MCP-1, MIP1α, CXCL1, IL-1β, and IL-6 in the heart (129).

The question that arises is how NF-κB is activated to induce proinflammatory genes in response to ANG II. More specifically, in contrast to MI discussed above, ANG II infusion does not lead to cell death and release of DAMPs at times when pronounced inflammatory gene expression is initiated (129). Accordingly signaling through TLRs would not likely occur as an immediate consequence of this intervention. TNF-α is induced in response to ANG II infusion and could signal to induce NF-κB activation, but NF-κB activation occurs quite early (129). A recent report implicates transactivation of RAGE by AT1 receptors in ANG II-mediated NF-κB activation and inflammatory signals (86). There is also considerable evidence that ANG II signaling activates NADPH oxidase not only in the vasculature but also in the heart and this could lead to accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that activate NF-κB (137, 139). While some of these potential mechanisms of NF-κB activation are plausible, our recent studies along with previously published data suggest another scenario.

CaMKIIδ AS A TRANSDUCER OF ANG II SIGNALING TO INFLAMMATION

Work from our laboratory, combined with studies from the groups of Mark Anderson and Johannes Backs, has provided considerable evidence that cardiac CaMKII mediates cardiac decompensation in response to pressure overload, MI, isoproterenol and ANG II infusion (5, 31, 61, 103, 106, 127, 129, 141). These studies used transgenic overexpression of CaMKII or CaMKII inhibitory peptides or CaMKII KO mice to reveal key mechanisms involved in CaMKII signaling. Observations made in some of these papers implicated CaMKII in the control of NF-κB signaling and inflammation (30, 60, 103, 104, 124). Specifically, our earlier studies revealed decreased activation of NF-κB in response to in vivo I/R in mice in which CaMKIIδ (the predominant cardiac isoform) was genetically depleted (60). Ex vivo I/R was also associated with CaMKII-mediated NF-κB signaling, through an effect on an upstream regulatory kinase, and lead to increases in IL-6 and TNF-α (30). Responses to in vivo I/R were also studied by Weinreuter et al. in the Backs laboratory using CaMKIIδ/γ double KO mice, and shown to be associated with CaMKII dependent alterations in expression of myriad mRNAs including those for proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (124). Likewise Singh et al. (103, 104) from the Anderson group implicated NF-κB activation through TLR and Myd88 signaling in the effects of CaMKII on MI. Inflammatory responses are generally considered to occur in immune cells and there is evidence for a role of CaMKII in immune cell signaling. However, it is the CaMKIIα and -γ isoforms, rather than CaMKIIδ that has been shown to regulate responses of macrophages (19, 63, 109). Moreover the studies above, and our work discussed below, used cardiomyocyte-specific inhibition or KO of CaMKII, supporting the concept that the prominent inflammatory effects of CaMKII result from its signaling in cardiomyocytes, not macrophages.

When there is ischemic damage, as in MI or I/R, CaMKII is activated through its oxidation by ROS generated by damaged mitochondria (64). CaMKII has also been shown to be activated in response to DAMPs (e.g., HMGB-1) (144). CaMKII activation can in turn contribute to cell death and mitochondrial dysfunction (46); thus a vicious cycle involving cell death, inflammation, and CaMKII activation is engaged. However, is CaMKII also a player in inflammatory responses to nonischemic interventions in particular ANG II infusion?

Our recent work addressed the role of CaMKII in ANG II-induced inflammation using mice in which CaMKIIδ was genetically deleted (129). More specifically CaMKII was deleted from cardiomyocytes by crossing floxed CaMKIIδ and MLC2v-Cre mice. Thus we tested not only involvement of CaMKII but also involvement of cardiomyocytes in the inflammatory response to ANG II. First, we measured NF-κB activation, as indicated by increases in nuclear p65 in the heart, and showed that this was nearly abolished when CaMKII was deleted from cardiomyocytes. Concomitantly mRNA levels of a series of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines including MCP-1 (CCL2), MIP1α (CCL3), CXCL1, IL-1β, and IL-6 were observed to increase at 1 day or as early as 3 h post-ANG II, and these responses were lost in the absence of cardiomyocyte CaMKII or in the presence of NF-κB inhibition. Finally recruitment of macrophages assessed by CD68 or F4/80 staining of mouse hearts was nearly completely abolished in hearts lacking cardiomyocyte CaMKIIδ. These findings lead to a number of unexpected and mechanistic conclusions. First, a major site at which ANG II signals to elicit cardiac inflammation is the cardiomyocyte. Second, activation of CaMKII serves to transduce the ANG II signal to NF-κB. Third, the myocyte serves as a significant source of generation of proinflammatory chemokines and cytokines.

INFLAMMATION IN TRANSVERSE AORTIC CONSTRICTION-INDUCED PRESSURE OVERLOAD MODEL

Inflammatory Gene Expression

TAC-induced pressure overload is the most commonly used murine models for eliciting hypertrophy and heart failure. Like ANG II infusion this is a nonischemic intervention and is not, at least at early times, associated with significant loss of cardiomyocytes (106, 131). The concept that pressure overload induces cardiac inflammation has only recently become appreciated although studies carried out more than a decade ago presented evidence that this occurs (10, 53, 131). For example, rat suprarenal aortic banding was shown to upregulate MCP-1 gene expression in the heart at day 1, a response that peaked at day 3 and returned to basal levels by day 28 (53). Significant upregulation of mRNA for genes including TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 was also observed to be maximal at 6 h after TAC in the mouse heart, decreasing at 1 and 3 days to basal levels (10). These proinflammatory genes were also shown to be transiently upregulated in the mouse heart in response to TAC in work from other laboratories (122, 131). Our recently published paper extended the repertoire of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines to include MIP1α, CXCL1, and CXCL2 and further delineated the mechanism and rapid kinetics of their activation in response to TAC (106). Increases in expression of these genes were observed at day 1.5, were maximal at day 3, and decreased over time.

Monocyte/Macrophage Accumulation

One of the earlier studies detailing the involvement of macrophages in the response to pressure overload showed that F4/80high-Ly6Clow macrophages increase at days 3, 6, and 21 (peaking at day 6) following TAC (126). In contrast to MI, there is minimal neutrophil recruitment in the heart subjected to TAC (126, 131), consistent with the lack of cardiomyocyte death. Our recent studies also demonstrated that F4/80-positive macrophages are increased by TAC, significant at 1 wk, peaking at 2 wk and sustained at lower levels up to 6 wk. Notably, this response was significantly attenuated in mice in which CaMKIIδ was deleted from cardiomyocytes. Using mice in which we selectively deleted MCP-1 in cardiac myocytes, we additionally provided evidence that macrophage accumulation was partially dependent on generation of MCP-1 in cardiomyocytes (106). This finding implied that it was a CCR2+ macrophage population that was increased by TAC since MCP-1 is the chemokine that recruits these cells. A recent study by Patel et al. (84) probed this more extensively, demonstrating that while resident CCR2- macrophages are increased by local expansion in response to 7-day TAC, significantly larger increases in Ly6Chigh-CCR2+ monocyte-derived macrophages are observed at this time. In contrast Jain et al. (59) reported that macrophage accumulation in the heart after 7-day TAC is mediated by proliferation of resident CCR2- macrophages since only at the later times (4 wk) did they observe increases in monocyte-derived CCR2+ cardiac macrophages. The reason for this discrepancy is not clear but indeed all of these studies demonstrate that macrophages increase in the heart in response to 1–2 wk TAC, a time that precedes the transition to HF. Much of this work also suggests that CCR2 is the critical receptor molecule expressed in the population of macrophages that contribute to cardiac inflammation following TAC, as is also the case for ANG II and MI. This is discussed further in MCP-1 Signaling Through CCR2 and Macrophages in Adverse Remodeling.

T-Lymphocyte Activation in Hearts Exposed to Pressure Overload

T cells are activated by APCs (antigen-presenting cells), including dendritic cells and macrophages. Activated CD4+ T cells (T-helper cells; Th cells) generate cytokines (e.g., interferon-γ) that play important roles in inflammation. Increases in circulating CD4+ T lymphocytes, which express proinflammatory cytokines, have been associated with LV dysfunction in patients with heart failure (29, 97, 136). Laroumanie et al. (54) used the TAC model to demonstrate accumulation of both CD4+ and CD8+ (killer T cell) subsets of T cells in the heart at 6 wk TAC. They correlated development of ventricular dysfunction and dilation with CD4+ accumulation based on studies using KO mice lacking mature CD4+ T cells. Subsequent work by Nevers et al. (76) from the Alcaide laboratory demonstrated that in addition to increases in systemic T cells, patients with nonischemic end-stage heart failure had increases in LV T cells. Kallikourdis et al. (48) also demonstrated increases in T cells in cardiac tissue from patients with aortic stenosis and nonimmune cardiomyopathies. Additional work from Salvador et al. (76, 93) examining the effects of pressure overload in mice revealed enhanced adhesion of T cells to vascular endothelium and activation of T cells in the heart draining mediastinal lymph node after TAC. Increased CD25, a marker of T-cell activation, was evident in cells from the mediastinal lymph node at times as early as 2 days TAC, and T-cell staining in the ventricle could be seen at 1 or 4 wk (48, 76, 84). Mechanistically T-cell infiltration into mouse cardiac tissue in response to pressure overload was shown to require increases in intercellular cell adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1) on endothelial cells (93) and be mediated through the actions of circulating chemokines on the receptor CXCR3 (78). Interestingly CXCR3 is expressed predominantly on the Th1 subset of T-helper cells (contrasting with the Th 2 and Th17 subsets implicated in MI-induced heart failure) (78). The site of immune T-cell activation also differs, occurring in the mediastinal lymph node following TAC versus the spleen in response to MI. Growing evidence supports a role for T cells in later stages of heart failure as strategies for blocking their activation and recruitment have salutary effects on TAC-induced adverse remodeling (12, 48).

Cardiomyocyte Role in TAC-Induced Inflammatory Signaling

Work from the Otsu laboratory, using mice in which DNase was deleted, provided initial evidence that cardiomyocytes can contribute to inflammation in hearts exposed to pressure overload. Their studies demonstrated that pressure overload can increase cytosolic mitoDNA, which leads to inflammation via activation of TLR9 localized to the endosome/lysosome and thereby contributes to development of heart failure (80). Although the model used is not physiological (mice are genetically deleted for DNAase) the findings nonetheless indicate that cardiomyocytes detect and respond to endogenous danger signals. DNA strand breaks can also occur with pressure overload and contribute to inflammation and the pathogenesis of heart failure (39). Thus changes in known damage signals can occur with TAC but are not likely to be involved at the earliest stages at which TAC initiates cardiac inflammation.

Our recent data showed that activation of CaMKIIδ in cardiomyocytes in response to pressure overload triggers NF-κB-mediated proinflammatory gene expression and contributes to subsequent macrophage accumulation in the heart (106). Importantly, we isolated cardiomyocytes from the mouse heart at various times after TAC and showed that the increases in proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine mRNA levels occurring at day 3 after TAC represented changes in cardiomyocytes rather than in the nonmyocyte fraction (which contained fibroblasts, endothelial and immune cells). This distinction is important because there is macrophage accumulation in the heart within the first few days after TAC (14, 122, 131). Certainly these cells contribute to the overall inflammatory profile that develops in the heart following TAC but our findings demonstrate that the cardiomyocyte is the primary site at which the earliest proinflammatory response is elicited. The fibrosis, ventricular dilation and contractile dysfunction that occur by 6 wk TAC are also significantly attenuated by deletion of cardiomyocyte CaMKIIδ and associated inflammatory signaling. Taken together these results strongly suggest that cardiomyocytes are the initial site where stress is sensed and the onset of inflammatory responses leading to adverse remodeling occurs.

NLRP3 INFLAMMASOME PRIMING AND ACTIVATION IN THE HEART

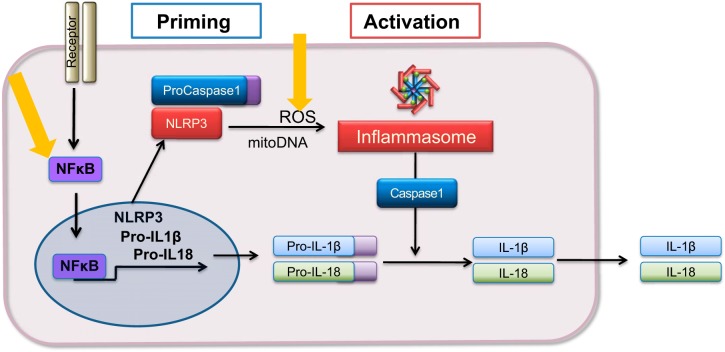

The NLRP3 inflammasome is a multiprotein complex that regulates maturation of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 by activating caspase-1. Signaling through NF-κB “primes” the inflammasome. The term priming (sometimes called step 1) refers to the transcriptional upregulation of components of this pathway including NLRP3 and the inactive precursor proteins pro IL-1β and pro IL-18. The assembled inflammasome complex that is “activated” by stress signals (e.g., ATP, ROS) leads to caspase-1 activation, which catalyzes cleavage of these cytokines to their biologically active forms, followed by their release from the cell (Fig. 1). Several studies have provided evidence that inflammasome activation occurs in the heart under ischemic conditions induced by MI and I/R (69, 72, 111, 112, 114, 115). While the cardiac fibroblast has been shown to be a site of inflammasome activation following ischemia reperfusion injury (49, 94) other data indicate that cardiomyocytes could also be involved in generating inflammasome-mediated signals in response to ischemia (72).

Fig. 1.

Steps in inflammasome priming and activation. Priming is the step involving NF-κB-regulated increases in components of the inflammasome. The inflammasome complex is assembled and activated by stress signals leading to caspase-1 activation. Caspase-1 cleaves pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18 to their biologically active forms which are released from the cell. Yellow arrows: sites of calcium calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMKII) regulation.

Of particular interest is emerging evidence that inflammasome activation in the heart can also be triggered by nonischemic stresses such as pressure overload and acute isoproterenol treatment (58, 132). How inflammasome activation occurs in the absence of cell death-mediated release of DAMPs, and whether the inflammasome is primed and activated within the cardiomyocyte or in other heart cells has not been resolved. A recent paper demonstrated that βAR stimulation acutely increases cardiac ROS and leads to rapid inflammasome-dependent generation of IL-18 (132). This study provided evidence that the inflammasome was activated in cardiomyocytes, specifically demonstrating increased cardiomyocyte ASC (apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain) specks, NLRP3, and cleaved IL-18. In a study examining the dependence of pressure overload induces responses on phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-γ signaling, Damilano et al. noted that increases in IL-1β gene expression observed in the heart at 2 wk TAC were not dependent on the local presence of inflammatory cells, suggesting generation of this inflammasome derived cytokine in myocardial cells (14). A recent study implicating the NLRP-3 inflammasome in the development of arrhythmias provided further evidence that inflammasome signaling in atrial myocytes was sufficient to induce arrhythmias and that markers of inflammasome activation were increased in atria of patients and in a dog model of atrial fibrillation (135).

A recent study from our laboratory provides compelling additional evidence regarding the role of cardiomyocytes as a primary site of origin of inflammasome activation in response to TAC. Using an enriched preparation of cardiomyocytes isolated from mouse hearts at 3 days TAC, we localized NLRP3 induction and caspase-1 activation, assessed by caspase-1 enzymatic activity and by visualization of activated caspase-1, to the cardiomyocyte compartment (106). We also showed increases in cleaved IL-18 in the enriched cardiomyocyte fraction at this time. Not only do these responses occur at a time after TAC that precedes macrophage recruitment, but we demonstrated that these indicators of inflammasome activation were not evident in the noncardiomyocyte cell fraction which contains immune cells, endothelial or fibroblasts. Thus inflammasome activation in cardiomyocytes appears to contribute to the initiation of inflammatory responses in the heart.

Our studies using TAC as well as ANG II infusion also revealed the mechanism by which the NLRP3 inflammasome components are transcriptionally upregulated (primed) and activated in response to these stimuli (106, 129) (Fig. 1). We determined that deletion of cardiomyocyte CaMKIIδ blocked increases in the NF-κB-regulated components of the inflammasome including IL-1β, IL-18, and NLRP3 mRNA, implicating CaMKIIδ signaling in ANG II- and TAC-induced inflammasome priming. CaMKIIδ was also required for TAC- and ANG I-induced increases in NLRP3 inflammasome activation as assessed by caspase-1 activity and IL-18 cleavage. We additionally explored the mechanism by which CaMKII regulates this latter process. Expression of constitutively active CaMKIIδ in cardiomyocytes induces ROS accumulation and activates caspase-1, which is prevented by scavenging mitochondrial ROS with mitoTEMPO (106, 127, 129). Furthermore, we carried out in vivo studies in which we showed that TAC increases mitoROS through CaMKIIδ, and that treatment with mitoTEMPO blocks this increase in ROS accumulation and attenuates caspase-1 activation (106). These findings are consistent with early work demonstrating that ROS activates the NLRP3 inflammasome in immune cells (143) as schematized in Fig. 1.

Our results implicate mitoROS in NLRP3 inflammasome activation in cardiomyocytes. In noncardiac systems oxidized mitoDNA can contribute to inflammasome activation (75, 101). Under certain conditions pressure overload can increase release of mitoDNA (80) or elicit a DNA damage response (39). Mechanisms such as these could also contribute to NLRP3 inflammsome activation in cardiomyocytes, particularly at later stages of heart failure.

One might also consider the possible involvement of these initiating events in development of pyroptosis, a mechanism by which caspase-1 activation results in cell rupture. Specifically once the inflammasome is activated, the resultant increase in caspase-1 activity could lead to cleavage of gasdermin D, promoting cell death and contributing to further propagation of inflammation. Pyroptosis or associated events have in fact been suggested to be involved in ischemic injury (57, 71, 88, 113).

ROLE OF INFLAMMATORY SIGNALS IN FIBROSIS AND ADVERSE REMODELING

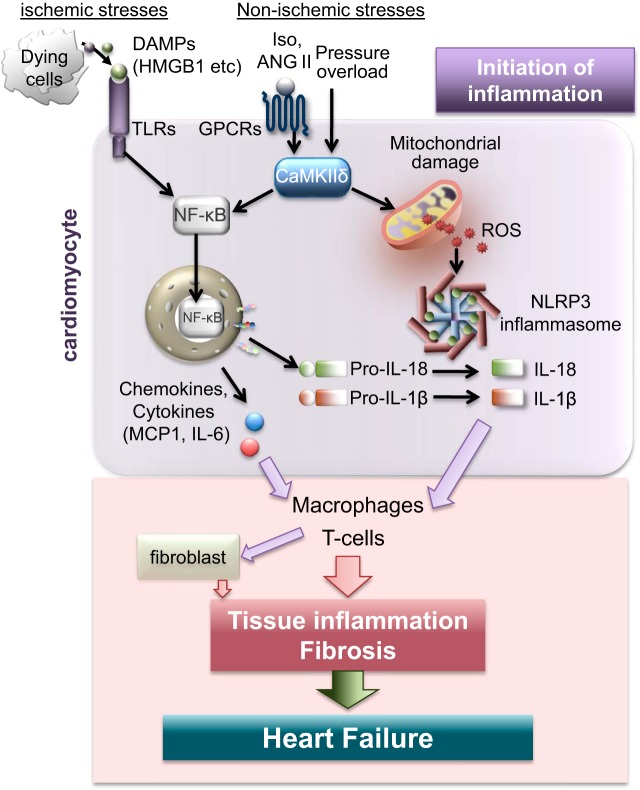

The section below describes evidence that the processes discussed above (MCP-1 gene expression, CCR2-mediated macrophage recruitment, NLRP3 inflammasome activation, and T-cell activation) are major contributors to the subsequent development of fibrosis and cardiac dysfunction induced by stress (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Cardiac inflammation is initiated in cardiomyocytes in response to ischemic and nonischemic stress. In response to ischemic stress, damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) released from dying cells activate Toll-like receptors (TLRs) leading to NF-κB activation and inflammation. In response to nonischemic stresses such as ANG II and pressure overload, calcium calmodulin-dependent protein kinase-δ (CaMKIIδ) is activated in cardiomyocytes. This early signaling event is independent of cell death and leads to NF-κB mediated expression of proinflammatory genes including monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), NOD-like pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3), and IL-1β. CaMKIIδ signaling also triggers activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in cardiomyocytes by increasing mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS), an event that leads to production of active IL-1β and IL-18. These cytokines and chemokines, generated in cardiomyocytes, initiate cardiac inflammation by recruiting macrophages and subsequently T cells, contributing to fibrosis, adverse cardiac remodeling and heart failure.

MCP-1 Signaling Through CCR2 and Macrophages in Adverse Remodeling

As detailed above, MCP-1 is one of the major proinflammatory chemokines that is transcriptionally upregulated by NF-κB signaling in response to either ischemic injury-induced release of DAMPs or ANG II and TAC-induced CaMKII activation. Blood borne monocytes are recruited through MCP-1 and subsequent binding to its receptor CCR2, a G protein-coupled receptor (24, 43, 92). The pathophysiological significance of CCR2+ macrophage recruitment to the heart in response to ischemic injury is supported by the findings that blockade of MCP-1, the CCR2 ligand, or inhibition of CCR2 signaling reduce excessive inflammation and attenuate damage induced by MI (15, 35, 36, 47). For example, Hayashidani et al. (36) used an NH2-terminal deletion mutant of MCP-1 expressed in vivo to block MCP-1 signaling and demonstrated attenuated LV remodeling and failure after MI, and an associated decrease in interstitial fibrosis. Attenuated myofibroblast accumulation and improved cardiac function were also observed after MI in global MCP-1 KO mice (15). These findings clearly suggest that MCP-1-mediated CCR2+ monocyte recruitment and subsequent expansion of macrophages in the infarct heart are key events in cardiac remodeling.

Emerging evidence suggests that MCP-1 signaling also plays a critical role in nonischemic stress-induced cardiac decompensation elicited by ANG II infusion and TAC. As cited earlier, Haudek et al. from the Entman group provided early evidence in studies using global KO mice that MCP-1 generation was also required for ANG II-induced CD45+ cell recruitment to the heart (34). Induction of type I and III collagen, TGF-β1, and TNF-α in response to ANG II infusion were attenuated in MCP-1 KO mouse hearts, implicating monocyte recruitment in the development of fibrosis (34). We also demonstrated that the recruitment of CD68 macrophages to the heart at 1 day of ANG II infusion was inhibited by pharmacological blockade of the CCR2 receptor with RS102895 and that this was associated with significantly attenuated fibrosis, assessed by Masson trichrome staining and collagen gene expression, at 3 days of ANG II infusion (129).

MCP-1 signaling has also been implicated in TAC-induced heart failure. Chronic treatment with an anti-MCP-1 monoclonal neutralizing antibody was shown to inhibit macrophage accumulation, fibroblast proliferation, and TGF-β induction in response to suprarenal aortic constriction-induced pressure overload (53). Inhibition of CCR2+ monocyte and macrophage engagement by anti-CCR2 monoclonal antibody during pressure overload reduced subsequent pathological hypertrophy, fibrosis, and systolic dysfunction (84). Our recent study used pharmacological antagonists of CCR2 (RS102895) to demonstrate diminished macrophage accumulation, attenuated fibrosis and preserved cardiac function in response to pressure overload (106). CCR2 KO mice also showed preserved cardiac function in response to TAC (59). Finally, the important role of the cardiomyocyte in generation of MCP-1 following TAC was demonstrated by our observation that selective deletion of MCP-1 in cardiomyocytes decreased fibrosis and attenuated cardiac dysfunction in response to TAC (106).

NLRP3 Inflammasome and Adverse Remodeling

As described above the NLRP3 inflammasome is activated by numerous cellular alarm signals through NF-κB priming and subsequent inflammasome complex formation occurs in response to secondary signals such as ATP or ROS. Once caspase-1 is cleaved by the inflammasome the biologically active forms of the potent cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 are generated and secreted from the cell where they play a major role in initiating and sustaining inflammation. Alternative inflammasomes could also contribute to IL-1β and IL-18 generation. AIM2 and NLRC4 inflammasomes in cardiomyocytes and cardiac macrophages are increased in peri-infarct regions of LV, consistent with the finding that NLRC4 is an important regulator of IL-18 in patients with acute coronary syndromes (21, 45).

The involvement of inflammasome signaling in cardiac disease resulting from MI is suggested by studies in animal models in which IL-1β signaling or the inflammasome are blocked (68, 118). MCC950 is a highly selective small molecule NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor (13). Recent studies have used MCC950 to demonstrate reduced infarct size and preserved cardiac function in a pig model of MI (112, 118), confirming prior findings using other small molecule inhibitors to ameliorate development of injury in rodent MI and I/R models (68, 69)

Clinical trials also provide strong evidence for the involvement of the inflammasome and IL-1 in cardiac disease. One clinical trial showed improvement in LV function in patients with rheumatoid arthritis being treated with the IL-1 receptor antagonist anakinra (44). More recently the REDHART study specifically examined the effect of anakinra in cardiac disease and reported improved cardiac performance in patients with decompensated systolic HF (121). The recent highly publicized CANTOS trial (90) was aimed at testing the effect of IL-1β blockade with canakinumab in patients with prior MI, in whom levels of low-density lipoprotein were normalized but inflammation, based on high sensitivity C-reactive protein levels, was elevated. A significant reduction in the incidence of adverse cardiac events, concomitant with decreased C-reactive protein levels, was observed in patients treated with canakinumab although this was not shown to be dose dependent and canakinumab increased the incidence of fatal infection (90). Importantly, secondary analysis of a subset of patients enrolled in the CANTOS trial directly addressed the effect of treatment on rehospitalization for heart failure. In this study a dose dependent salutary effect on heart failure outcomes was observed (27).

The other cytokine produced through activation of the inflammasome, IL-18, has also been targeted using a neutralizing antibody and its effects in MI and heart failure are under study (79). Notably in mouse models the administration of recombinant IL-18 has been reported to induce interstitial fibrosis, myocardial remodeling and myocardial dysfunction (87, 130). IL-18 has also been suggested to mediate the cardiomyocyte dysfunction induced by IL-1β administration (116). Clinical trials using inhibitors of this cytokine, which may be particularly critical for mediating inflammation-induced cardiac dysfunction, are underway.

With regard to the effect of inflammasome inhibition in the pressure overload model, initial studies relied upon Chinese herbal medicines used to treat fibrosis (triptolide and pirfenidone) and suggested to affect NLRP3 inflammasome activity in the heart (83). These drugs were shown to inhibit formation of IL-1β and IL-18, decrease macrophage infiltration and fibrosis and improve TAC-induced cardiac diastolic and systolic function (58, 123). Triptolide was also shown to attenuate cardiac fibrosis in response to Ang II (83). Our recent work, and a study by the Walsh laboratory, used MCC950, the more selective NLRP3 inhibitor mentioned above. In our study the inhibitor treatment was used only during the first 7 days after TAC but found nonetheless to significantly attenuate development of fibrosis, cardiac dilation and contractile dysfunction observed at 4–6 wk after TAC (106). Treatment throughout the 5 wk following TAC leads to an impressive attenuation of TAC-induced adverse remodeling (95).

T-Cell-Mediated Signals and Adverse Remodeling

A role for T cells in the adverse remodeling that occurs in response to ischemic heart failure was demonstrated in studies using antibody-mediated CD4+ T-cell depletion. Reduced cardiac infiltration of CD4+ T cells prevented progressive LV dilation (8). TAC-induced development of fibrosis and cardiac dysfunction was also demonstrated by Laroumanie et al. to involve T cells, and they specifically identified the role for CD4+ (vs CD8+) in TAC-induced adverse remodeling (54). These studies compared mice lacking CD4+ (MHCII KO mice) and CD8 (CD 8 KO mice) and showed diminished TAC-induced fibrosis and ventricular dysfunction only in the former line of mice (54). Another study used genetic deletion of the α-chain of the T-cell receptor (TCRα−/−) as well as T-cell depletion in wild-type mice and reported preserved LV function, reduced LV fibrosis, less inflammation, and improved survival after TAC (76). TAC-induced heart failure was also ameliorated by treatment of mice with abatacept, which blocks T-cell costimulatory molecules (CD80 and CD86) on antigen presenting cells (48).

A question of considerable interest is the relationship between TAC-induced macrophage accumulation and T-cell recruitment or activation, both of which clearly contribute to development of fibrosis and ventricular dysfunction. T cells have in some cases been observed in the heart early after TAC, and the cytokines they generate can activate macrophages, thus there is a likely role for cross talk in this direction. On the other hand massive accumulation of macrophages generally precedes the appearance of T cells in the heart and macrophages can serve as antigen presenting cells thus representing key players in engaging T cells in cardiac dysfunction. In support of this, Patel et al. (84) reported that blocking macrophage recruitment with a monoclonal antibody against murine CCR2, also decreased CD4+ T-cell expansion. T-cell recruitment was recently shown to be mediated through CXCR3, a receptor stimulated by CXCL9 and CXCL10. These chemokines are produced by cardiac resident and infiltrated macrophages further suggesting a possible link between macrophages and T cells (78). Another question is the mechanism by which cardiac accumulated T cells promote fibrosis in nonischemic disease. Nevers et al. (77) from the Alcaide laboratory observed that T cells activated in response to TAC adhere to cardiac fibroblasts through integrin-α4, inducing TGF-β expression in these cells and thereby contributing to fibrosis.

EVIDENCE THAT EARLY BLOCKADE OF INFLAMMATORY SIGNALS AMELIORATES FIBROSIS AND VENTRICULAR DYSFUNCTION

Our recent paper showed that treatment with the CaMKII inhibitor KN93 during the first two weeks of TAC attenuated the fibrotic response observed at 6 wk after TAC (106). In contrast, delayed treatment beginning 2 weeks after TAC had no significant effect on development of fibrosis, dilation or contractile dysfunction. We confirmed this observation in studies in which AAV9-Cre virus was used to delete cardiomyocyte CaMKII just before TAC, or two weeks after TAC. The former treatment significantly attenuated fibrosis and cardiac dysfunction while the latter was ineffective (T. Suetomi, S. Miyamoto, and J. H. Brown, unpublished observations). Patel et al. (85) from the Prabhu laboratory reported similar effects when they specifically targeted macrophage-mediated inflammation at early or later stages of TAC. In their studies in which macrophage function was inhibited by inducible macrophage deletion at 2 wk after TAC, subsequent cardiac fibrosis and remodeling were unaffected (85). On the other hand, use of either a pharmacological inhibitor of CCR2 (RS 504393) or a monoclonal antibody against murine CCR2 given only at an early time (3–7 days) after TAC attenuated later cardiac fibrosis, T-cell expansion, and LV remodeling and dysfunction at day 28 (84). These data are consistent with and support the notion that early inhibition of inflammatory signals leading to immune cell recruitment would be a highly effective strategy for preventing heart failure development. Attempts to treat established heart failure by blocking inflammation have been largely unsuccessful (38) possibly because once inflammatory responses are fully established, a multitude of immune cell types and secreted factors are engaged. On the other hand, more targeted approaches could be feasible. For example, involvement of CD4+ T cells, which are activated at later times following the induction of TAC and subsequent to macrophage recruitment, may in fact be amenable to intervention once heart failure has developed, as suggested by Kallikourdis et al. in the Condorelli laboratory (48). Likewise it now appears that there is conversion of regulatory T cells (Tregs) into dysfunctional Tregs at later times (9) suggesting that immune therapy targeting this cell population or the factors it generates could also be useful in more developed stages of heart failure.

CONCLUSIONS

Inflammation is clearly triggered by cell death and contributes to heart failure in ischemic heart disease which develops after MI. Until recently there was limited recognition of the prominent role played by inflammation in nonischemic heart disease and adverse structural remodeling. We now know that sterile inflammation occurs in response to pressure overload and ANG II treatment and is initiated within the myocardium leading to a cascade of immune responses. Cardiomyocytes are a surprising but undeniable initiating site of inflammatory gene expression and inflammasome activation in response to nonischemic stress. Future research addressing how inflammation, instigated in cardiomyocytes, propagates to lead to fibrosis, apoptosis and changes in cardiac function should shed light on new therapeutic approaches to attenuate inflammation and its downstream consequences.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants R37-HL-028143 and R01-HL-145459 (to J. H. Brown), American Heart Association Grant 19TPA34910011 (to S. Miyamoto), and American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship 17POST33680017, a research fellowship from Uehara Memorial Foundation and the Kanae Foundation for the Promotion of Medical Science (Japan) (to T. Suetomi).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

T.S. and S.M. prepared figures; T.S. drafted manuscript; T.S., S.M., and J.H.B. edited and revised manuscript; T.S., S.M., and J.H.B. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson ME, Brown JH, Bers DM. CaMKII in myocardial hypertrophy and heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol 51: 468–473, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrassy M, Volz HC, Igwe JC, Funke B, Eichberger SN, Kaya Z, Buss S, Autschbach F, Pleger ST, Lukic IK, Bea F, Hardt SE, Humpert PM, Bianchi ME, Mairbäurl H, Nawroth PP, Remppis A, Katus HA, Bierhaus A. High-mobility group box-1 in ischemia-reperfusion injury of the heart. Circulation 117: 3216–3226, 2008. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.769331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anker SD, von Haehling S. Inflammatory mediators in chronic heart failure: an overview. Heart 90: 464–470, 2004. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2002.007005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aoki H, Richmond M, Izumo S, Sadoshima J. Specific role of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway in angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy in vitro. Biochem J 347: 275–284, 2000. doi: 10.1042/bj3470275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Backs J, Backs T, Neef S, Kreusser MM, Lehmann LH, Patrick DM, Grueter CE, Qi X, Richardson JA, Hill JA, Katus HA, Bassel-Duby R, Maier LS, Olson EN. The delta isoform of CaM kinase II is required for pathological cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling after pressure overload. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 2342–2347, 2009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813013106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bajpai G, Bredemeyer A, Li W, Zaitsev K, Koenig AL, Lokshina I, Mohan J, Ivey B, Hsiao HM, Weinheimer C, Kovacs A, Epelman S, Artyomov M, Kreisel D, Lavine KJ. Tissue resident CCR2- and CCR2+ cardiac macrophages differentially orchestrate monocyte recruitment and fate specification following myocardial injury. Circ Res 124: 263–278, 2019. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.314028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bajpai G, Schneider C, Wong N, Bredemeyer A, Hulsmans M, Nahrendorf M, Epelman S, Kreisel D, Liu Y, Itoh A, Shankar TS, Selzman CH, Drakos SG, Lavine KJ. The human heart contains distinct macrophage subsets with divergent origins and functions. Nat Med 24: 1234–1245, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0059-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bansal SS, Ismahil MA, Goel M, Patel B, Hamid T, Rokosh G, Prabhu SD. Activated T lymphocytes are essential drivers of pathological remodeling in ischemic heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 10: e003688, 2017. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.116.003688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bansal SS, Ismahil MA, Goel M, Zhou G, Rokosh G, Hamid T, Prabhu SD. Dysfunctional and proinflammatory regulatory T-lymphocytes are essential for adverse cardiac remodeling in ischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 139: 206–221, 2019. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.036065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baumgarten G, Knuefermann P, Kalra D, Gao F, Taffet GE, Michael L, Blackshear PJ, Carballo E, Sivasubramanian N, Mann DL. Load-dependent and -independent regulation of proinflammatory cytokine and cytokine receptor gene expression in the adult mammalian heart. Circulation 105: 2192–2197, 2002. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000015608.37608.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell SE, Katwa LC. Angiotensin II stimulated expression of transforming growth factor-beta1 in cardiac fibroblasts and myofibroblasts. J Mol Cell Cardiol 29: 1947–1958, 1997. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carrillo-Salinas FJ, Ngwenyama N, Anastasiou M, Kaur K, Alcaide P. Heart inflammation: immune cell roles and roads to the heart. Am J Pathol 189: 1482–1494, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2019.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coll RC, Robertson AA, Chae JJ, Higgins SC, Muñoz-Planillo R, Inserra MC, Vetter I, Dungan LS, Monks BG, Stutz A, Croker DE, Butler MS, Haneklaus M, Sutton CE, Núñez G, Latz E, Kastner DL, Mills KH, Masters SL, Schroder K, Cooper MA, O’Neill LA. A small-molecule inhibitor of the NLRP3 inflammasome for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Nat Med 21: 248–255, 2015. doi: 10.1038/nm.3806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Damilano F, Franco I, Perrino C, Schaefer K, Azzolino O, Carnevale D, Cifelli G, Carullo P, Ragona R, Ghigo A, Perino A, Lembo G, Hirsch E. Distinct effects of leukocyte and cardiac phosphoinositide 3-kinase γ activity in pressure overload-induced cardiac failure. Circulation 123: 391–399, 2011. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.950543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dewald O, Zymek P, Winkelmann K, Koerting A, Ren G, Abou-Khamis T, Michael LH, Rollins BJ, Entman ML, Frangogiannis NG. CCL2/monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 regulates inflammatory responses critical to healing myocardial infarcts. Circ Res 96: 881–889, 2005. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000163017.13772.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dewenter M, Neef S, Vettel C, Lämmle S, Beushausen C, Zelarayan LC, Katz S, von der Lieth A, Meyer-Roxlau S, Weber S, Wieland T, Sossalla S, Backs J, Brown JH, Maier LS, El-Armouche A. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II activity persists during chronic β-adrenoceptor blockade in experimental and human heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 10: e003840, 2017. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.117.003840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dick SA, Epelman S. Chronic heart failure and inflammation: what do we really know? Circ Res 119: 159–176, 2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dobaczewski M, Xia Y, Bujak M, Gonzalez-Quesada C, Frangogiannis NG. CCR5 signaling suppresses inflammation and reduces adverse remodeling of the infarcted heart, mediating recruitment of regulatory T cells. Am J Pathol 176: 2177–2187, 2010. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doran AC, Ozcan L, Cai B, Zheng Z, Fredman G, Rymond CC, Dorweiler B, Sluimer JC, Hsieh J, Kuriakose G, Tall AR, Tabas I. CAMKIIγ suppresses an efferocytosis pathway in macrophages and promotes atherosclerotic plaque necrosis. J Clin Invest 127: 4075–4089, 2017. doi: 10.1172/JCI94735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duerrschmid C, Crawford JR, Reineke E, Taffet GE, Trial J, Entman ML, Haudek SB. TNF receptor 1 signaling is critically involved in mediating angiotensin-II-induced cardiac fibrosis. J Mol Cell Cardiol 57: 59–67, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Durga Devi T, Babu M, Mäkinen P, Kaikkonen MU, Heinaniemi M, Laakso H, Ylä-Herttuala E, Rieppo L, Liimatainen T, Naumenko N, Tavi P, Ylä-Herttuala S. Aggravated postinfarct heart failure in type 2 diabetes is associated with impaired mitophagy and exaggerated inflammasome activation. Am J Pathol 187: 2659–2673, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2017.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dzau VJ. Tissue renin-angiotensin system in myocardial hypertrophy and failure. Arch Intern Med 153: 937–942, 1993. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1993.00410080011002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elrod JW, Wong R, Mishra S, Vagnozzi RJ, Sakthievel B, Goonasekera SA, Karch J, Gabel S, Farber J, Force T, Heller Brown J, Murphy E, Molkentin JD. Cyclophilin D controls mitochondrial pore-dependent Ca(2+) exchange, metabolic flexibility, and propensity for heart failure in mice. J Clin Invest 120: 3680–3687, 2010. doi: 10.1172/JCI43171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Epelman S, Lavine KJ, Beaudin AE, Sojka DK, Carrero JA, Calderon B, Brija T, Gautier EL, Ivanov S, Satpathy AT, Schilling JD, Schwendener R, Sergin I, Razani B, Forsberg EC, Yokoyama WM, Unanue ER, Colonna M, Randolph GJ, Mann DL. Embryonic and adult-derived resident cardiac macrophages are maintained through distinct mechanisms at steady state and during inflammation. Immunity 40: 91–104, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Epelman S, Liu PP, Mann DL. Role of innate and adaptive immune mechanisms in cardiac injury and repair. Nat Rev Immunol 15: 117–129, 2015. doi: 10.1038/nri3800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erickson JR, Joiner ML, Guan X, Kutschke W, Yang J, Oddis CV, Bartlett RK, Lowe JS, O’Donnell SE, Aykin-Burns N, Zimmerman MC, Zimmerman K, Ham AJ, Weiss RM, Spitz DR, Shea MA, Colbran RJ, Mohler PJ, Anderson ME. A dynamic pathway for calcium-independent activation of CaMKII by methionine oxidation. Cell 133: 462–474, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Everett BM, Cornel JH, Lainscak M, Anker SD, Abbate A, Thuren T, Libby P, Glynn RJ, Ridker PM. Anti-inflammatory therapy with canakinumab for the prevention of hospitalization for heart failure. Circulation 139: 1289–1299, 2019. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.038010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fernández-Ruiz I. Immune system and cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol 13: 503, 2016. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2016.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fukunaga T, Soejima H, Irie A, Sugamura K, Oe Y, Tanaka T, Kojima S, Sakamoto T, Yoshimura M, Nishimura Y, Ogawa H. Expression of interferon-gamma and interleukin-4 production in CD4+ T cells in patients with chronic heart failure. Heart Vessels 22: 178–183, 2007. doi: 10.1007/s00380-006-0955-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gray CB, Suetomi T, Xiang S, Mishra S, Blackwood EA, Glembotski CC, Miyamoto S, Westenbrink BD, Brown JH. CaMKIIδ subtypes differentially regulate infarct formation following ex vivo myocardial ischemia/reperfusion through NF-κB and TNF-α. J Mol Cell Cardiol 103: 48–55, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grimm M, Ling H, Willeford A, Pereira L, Gray CB, Erickson JR, Sarma S, Respress JL, Wehrens XH, Bers DM, Brown JH. CaMKIIδ mediates β-adrenergic effects on RyR2 phosphorylation and SR Ca(2+) leak and the pathophysiological response to chronic β-adrenergic stimulation. J Mol Cell Cardiol 85: 282–291, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Halade GV, Norris PC, Kain V, Serhan CN, Ingle KA. Splenic leukocytes define the resolution of inflammation in heart failure. Sci Signal 11: eaao1818, 2018. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aao1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hartupee J, Mann DL. Role of inflammatory cells in fibroblast activation. J Mol Cell Cardiol 93: 143–148, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haudek SB, Cheng J, Du J, Wang Y, Hermosillo-Rodriguez J, Trial J, Taffet GE, Entman ML. Monocytic fibroblast precursors mediate fibrosis in angiotensin-II-induced cardiac hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol 49: 499–507, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayasaki T, Kaikita K, Okuma T, Yamamoto E, Kuziel WA, Ogawa H, Takeya M. CC chemokine receptor-2 deficiency attenuates oxidative stress and infarct size caused by myocardial ischemia-reperfusion in mice. Circ J 70: 342–351, 2006. doi: 10.1253/circj.70.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hayashidani S, Tsutsui H, Shiomi T, Ikeuchi M, Matsusaka H, Suematsu N, Wen J, Egashira K, Takeshita A. Anti-monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 gene therapy attenuates left ventricular remodeling and failure after experimental myocardial infarction. Circulation 108: 2134–2140, 2003. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000092890.29552.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heidt T, Courties G, Dutta P, Sager HB, Sebas M, Iwamoto Y, Sun Y, Da Silva N, Panizzi P, van der Laan AM, Swirski FK, Weissleder R, Nahrendorf M. Differential contribution of monocytes to heart macrophages in steady-state and after myocardial infarction. Circ Res 115: 284–295, 2014. [Erratum in Circ Res 115: e95, 2014.] doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.303567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heymans S, Hirsch E, Anker SD, Aukrust P, Balligand JL, Cohen-Tervaert JW, Drexler H, Filippatos G, Felix SB, Gullestad L, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Janssens S, Latini R, Neubauer G, Paulus WJ, Pieske B, Ponikowski P, Schroen B, Schultheiss HP, Tschöpe C, Van Bilsen M, Zannad F, McMurray J, Shah AM. Inflammation as a therapeutic target in heart failure? A scientific statement from the Translational Research Committee of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail 11: 119–129, 2009. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfn043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Higo T, Naito AT, Sumida T, Shibamoto M, Okada K, Nomura S, Nakagawa A, Yamaguchi T, Sakai T, Hashimoto A, Kuramoto Y, Ito M, Hikoso S, Akazawa H, Lee JK, Shiojima I, McKinnon PJ, Sakata Y, Komuro I. DNA single-strand break-induced DNA damage response causes heart failure. Nat Commun 8: 15104, 2017. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hilgendorf I, Gerhardt LM, Tan TC, Winter C, Holderried TA, Chousterman BG, Iwamoto Y, Liao R, Zirlik A, Scherer-Crosbie M, Hedrick CC, Libby P, Nahrendorf M, Weissleder R, Swirski FK. Ly-6Chigh monocytes depend on Nr4a1 to balance both inflammatory and reparative phases in the infarcted myocardium. Circ Res 114: 1611–1622, 2014. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hofmann U, Beyersdorf N, Weirather J, Podolskaya A, Bauersachs J, Ertl G, Kerkau T, Frantz S. Activation of CD4+ T lymphocytes improves wound healing and survival after experimental myocardial infarction in mice. Circulation 125: 1652–1663, 2012. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.044164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huke S, Desantiago J, Kaetzel MA, Mishra S, Brown JH, Dedman JR, Bers DM. SR-targeted CaMKII inhibition improves SR Ca2+ handling, but accelerates cardiac remodeling in mice overexpressing CaMKIIδC. J Mol Cell Cardiol 50: 230–238, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hulsmans M, Sam F, Nahrendorf M. Monocyte and macrophage contributions to cardiac remodeling. J Mol Cell Cardiol 93: 149–155, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ikonomidis I, Lekakis JP, Nikolaou M, Paraskevaidis I, Andreadou I, Kaplanoglou T, Katsimbri P, Skarantavos G, Soucacos PN, Kremastinos DT. Inhibition of interleukin-1 by anakinra improves vascular and left ventricular function in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Circulation 117: 2662–2669, 2008. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.731877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johansson Å, Eriksson N, Becker RC, Storey RF, Himmelmann A, Hagström E, Varenhorst C, Axelsson T, Barratt BJ, James SK, Katus HA, Steg PG, Syvänen AC, Wallentin L, Siegbahn A; PLATO Investigators . NLRC4 Inflammasome is an important regulator of interleukin-18 levels in patients with acute coronary syndromes: genome-wide association study in the PLATelet inhibition and patient outcomes trial (PLATO). Circ Cardiovasc Genet 8: 498–506, 2015. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.114.000724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Joiner ML, Koval OM, Li J, He BJ, Allamargot C, Gao Z, Luczak ED, Hall DD, Fink BD, Chen B, Yang J, Moore SA, Scholz TD, Strack S, Mohler PJ, Sivitz WI, Song LS, Anderson ME. CaMKII determines mitochondrial stress responses in heart. Nature 491: 269–273, 2012. doi: 10.1038/nature11444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaikita K, Hayasaki T, Okuma T, Kuziel WA, Ogawa H, Takeya M. Targeted deletion of CC chemokine receptor 2 attenuates left ventricular remodeling after experimental myocardial infarction. Am J Pathol 165: 439–447, 2004. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63309-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kallikourdis M, Martini E, Carullo P, Sardi C, Roselli G, Greco CM, Vignali D, Riva F, Ormbostad Berre AM, Stølen TO, Fumero A, Faggian G, Di Pasquale E, Elia L, Rumio C, Catalucci D, Papait R, Condorelli G. T cell costimulation blockade blunts pressure overload-induced heart failure. Nat Commun 8: 14680, 2017. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kawaguchi M, Takahashi M, Hata T, Kashima Y, Usui F, Morimoto H, Izawa A, Takahashi Y, Masumoto J, Koyama J, Hongo M, Noda T, Nakayama J, Sagara J, Taniguchi S, Ikeda U. Inflammasome activation of cardiac fibroblasts is essential for myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circulation 123: 594–604, 2011. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.982777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.King KR, Aguirre AD, Ye YX, Sun Y, Roh JD, Ng RP Jr, Kohler RH, Arlauckas SP, Iwamoto Y, Savol A, Sadreyev RI, Kelly M, Fitzgibbons TP, Fitzgerald KA, Mitchison T, Libby P, Nahrendorf M, Weissleder R. IRF3 and type I interferons fuel a fatal response to myocardial infarction. Nat Med 23: 1481–1487, 2017. doi: 10.1038/nm.4428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kreusser MM, Lehmann LH, Keranov S, Hoting MO, Oehl U, Kohlhaas M, Reil JC, Neumann K, Schneider MD, Hill JA, Dobrev D, Maack C, Maier LS, Gröne HJ, Katus HA, Olson EN, Backs J. Cardiac CaM Kinase II genes δ and γ contribute to adverse remodeling but redundantly inhibit calcineurin-induced myocardial hypertrophy. Circulation 130: 1262–1273, 2014. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.006185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kreusser MM, Lehmann LH, Wolf N, Keranov S, Jungmann A, Gröne HJ, Müller OJ, Katus HA, Backs J. Inducible cardiomyocyte-specific deletion of CaM kinase II protects from pressure overload-induced heart failure. Basic Res Cardiol 111: 65, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s00395-016-0581-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kuwahara F, Kai H, Tokuda K, Takeya M, Takeshita A, Egashira K, Imaizumi T. Hypertensive myocardial fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction: another model of inflammation? Hypertension 43: 739–745, 2004. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000118584.33350.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Laroumanie F, Douin-Echinard V, Pozzo J, Lairez O, Tortosa F, Vinel C, Delage C, Calise D, Dutaur M, Parini A, Pizzinat N. CD4+ T cells promote the transition from hypertrophy to heart failure during chronic pressure overload. Circulation 129: 2111–2124, 2014. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.007101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lavine KJ, Epelman S, Uchida K, Weber KJ, Nichols CG, Schilling JD, Ornitz DM, Randolph GJ, Mann DL. Distinct macrophage lineages contribute to disparate patterns of cardiac recovery and remodeling in the neonatal and adult heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 16029–16034, 2014. [Erratum in Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113: E1414, 2014.] doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406508111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leask A. Getting to the heart of the matter: new insights into cardiac fibrosis. Circ Res 116: 1269–1276, 2015. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.305381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lei Q, Yi T, Chen C. NF-κB-Gasdermin D (GSDMD) axis couples oxidative stress and NACHT, LRR and PYD domains-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome-mediated cardiomyocyte pyroptosis following myocardial infarction. Med Sci Monit 24: 6044–6052, 2018. doi: 10.12659/MSM.908529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li R, Lu K, Wang Y, Chen M, Zhang F, Shen H, Yao D, Gong K, Zhang Z. Triptolide attenuates pressure overload-induced myocardial remodeling in mice via the inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 485: 69–75, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liao X, Shen Y, Zhang R, Sugi K, Vasudevan NT, Alaiti MA, Sweet DR, Zhou L, Qing Y, Gerson SL, Fu C, Wynshaw-Boris A, Hu R, Schwartz MA, Fujioka H, Richardson B, Cameron MJ, Hayashi H, Stamler JS, Jain MK. Distinct roles of resident and nonresident macrophages in nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115: E4661–E4669, 2018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1720065115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ling H, Gray CB, Zambon AC, Grimm M, Gu Y, Dalton N, Purcell NH, Peterson K, Brown JH. Ca2+/Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II δ mediates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury through nuclear factor-κB. Circ Res 112: 935–944, 2013. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.276915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ling H, Zhang T, Pereira L, Means CK, Cheng H, Gu Y, Dalton ND, Peterson KL, Chen J, Bers D, Brown JH. Requirement for Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II in the transition from pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy to heart failure in mice. J Clin Invest 119: 1230–1240, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu L, Wang Y, Cao ZY, Wang MM, Liu XM, Gao T, Hu QK, Yuan WJ, Lin L. Up-regulated TLR4 in cardiomyocytes exacerbates heart failure after long-term myocardial infarction. J Cell Mol Med 19: 2728–2740, 2015. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu X, Yao M, Li N, Wang C, Zheng Y, Cao X. CaMKII promotes TLR-triggered proinflammatory cytokine and type I interferon production by directly binding and activating TAK1 and IRF3 in macrophages. Blood 112: 4961–4970, 2008. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-144022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Luo M, Guan X, Luczak ED, Lang D, Kutschke W, Gao Z, Yang J, Glynn P, Sossalla S, Swaminathan PD, Weiss RM, Yang B, Rokita AG, Maier LS, Efimov IR, Hund TJ, Anderson ME. Diabetes increases mortality after myocardial infarction by oxidizing CaMKII. J Clin Invest 123: 1262–1274, 2013. doi: 10.1172/JCI65268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ma Y, Mouton AJ, Lindsey ML. Cardiac macrophage biology in the steady-state heart, the aging heart, and following myocardial infarction. Transl Res 191: 15–28, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Magna M, Pisetsky DS. The alarmin properties of DNA and DNA-associated nuclear proteins. Clin Ther 38: 1029–1041, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2016.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mann DL. The emerging role of innate immunity in the heart and vascular system: for whom the cell tolls. Circ Res 108: 1133–1145, 2011. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.226936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Marchetti C, Chojnacki J, Toldo S, Mezzaroma E, Tranchida N, Rose SW, Federici M, Van Tassell BW, Zhang S, Abbate A. A novel pharmacologic inhibitor of the NLRP3 inflammasome limits myocardial injury after ischemia-reperfusion in the mouse. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 63: 316–322, 2014. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Marchetti C, Toldo S, Chojnacki J, Mezzaroma E, Liu K, Salloum FN, Nordio A, Carbone S, Mauro AG, Das A, Zalavadia AA, Halquist MS, Federici M, Van Tassell BW, Zhang S, Abbate A. Pharmacologic inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome preserves cardiac function after ischemic and nonischemic injury in the mouse. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 66: 1–8, 2015. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Matzinger P. Tolerance, danger, and the extended family. Annu Rev Immunol 12: 991–1045, 1994. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.005015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Merkle S, Frantz S, Schön MP, Bauersachs J, Buitrago M, Frost RJ, Schmitteckert EM, Lohse MJ, Engelhardt S. A role for caspase-1 in heart failure. Circ Res 100: 645–653, 2007. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000260203.55077.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mezzaroma E, Toldo S, Farkas D, Seropian IM, Van Tassell BW, Salloum FN, Kannan HR, Menna AC, Voelkel NF, Abbate A. The inflammasome promotes adverse cardiac remodeling following acute myocardial infarction in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 19725–19730, 2011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108586108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nahrendorf M, Swirski FK. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity in the heart. Circ Res 112: 1624–1633, 2013. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nahrendorf M, Swirski FK, Aikawa E, Stangenberg L, Wurdinger T, Figueiredo JL, Libby P, Weissleder R, Pittet MJ. The healing myocardium sequentially mobilizes two monocyte subsets with divergent and complementary functions. J Exp Med 204: 3037–3047, 2007. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nakahira K, Haspel JA, Rathinam VA, Lee SJ, Dolinay T, Lam HC, Englert JA, Rabinovitch M, Cernadas M, Kim HP, Fitzgerald KA, Ryter SW, Choi AM. Autophagy proteins regulate innate immune responses by inhibiting the release of mitochondrial DNA mediated by the NALP3 inflammasome. Nat Immunol 12: 222–230, 2011. doi: 10.1038/ni.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nevers T, Salvador AM, Grodecki-Pena A, Knapp A, Velázquez F, Aronovitz M, Kapur NK, Karas RH, Blanton RM, Alcaide P. Left ventricular T-cell recruitment contributes to the pathogenesis of heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 8: 776–787, 2015. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nevers T, Salvador AM, Velazquez F, Ngwenyama N, Carrillo-Salinas FJ, Aronovitz M, Blanton RM, Alcaide P. Th1 effector T cells selectively orchestrate cardiac fibrosis in nonischemic heart failure. J Exp Med 214: 3311–3329, 2017. doi: 10.1084/jem.20161791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ngwenyama N, Salvador AM, Velázquez F, Nevers T, Levy A, Aronovitz M, Luster AD, Huggins GS, Alcaide P. CXCR3 regulates CD4+ T cell cardiotropism in pressure overload-induced cardiac dysfunction. JCI Insight 4: e125527, 2019. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.125527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.O’Brien LC, Mezzaroma E, Van Tassell BW, Marchetti C, Carbone S, Abbate A, Toldo S. Interleukin-18 as a therapeutic target in acute myocardial infarction and heart failure. Mol Med 20: 221–229, 2014. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2014.00034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Oka T, Hikoso S, Yamaguchi O, Taneike M, Takeda T, Tamai T, Oyabu J, Murakawa T, Nakayama H, Nishida K, Akira S, Yamamoto A, Komuro I, Otsu K. Mitochondrial DNA that escapes from autophagy causes inflammation and heart failure. Nature 485: 251–255, 2012. [Erratum in Nature 490: 292, 2012.] doi: 10.1038/nature10992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ong SB, Hernández-Reséndiz S, Crespo-Avilan GE, Mukhametshina RT, Kwek XY, Cabrera-Fuentes HA, Hausenloy DJ. Inflammation following acute myocardial infarction: Multiple players, dynamic roles, and novel therapeutic opportunities. Pharmacol Ther 186: 73–87, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]