Abstract

Cyanobacteria played an important role in the evolution of Early Earth and the biosphere. They are responsible for the oxygenation of the atmosphere and oceans since the Great Oxidation Event around 2.4 Ga, debatably earlier. They are also major primary producers in past and present oceans, and the ancestors of the chloroplast. Nevertheless, the identification of cyanobacteria in the early fossil record remains ambiguous because the morphological criteria commonly used are not always reliable for microfossil interpretation. Recently, new biosignatures specific to cyanobacteria were proposed. Here, we review the classic and new cyanobacterial biosignatures. We also assess the reliability of the previously described cyanobacteria fossil record and the challenges of molecular approaches on modern cyanobacteria. Finally, we suggest possible new calibration points for molecular clocks, and strategies to improve our understanding of the timing and pattern of the evolution of cyanobacteria and oxygenic photosynthesis.

Keywords: Biosignatures, Cyanobacteria, Evolution, Microfossils, Molecular clocks, Precambrian

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Origin and evolution of cyanobacteria, oxygenic photosynthesis and plasts are debated.

-

•

Cyanobacterial fossil record starts unambiguously at 1.89–1.84 Ga.

-

•

Classic and new cyanobacterial signatures, and their fossil record are reassessed.

-

•

Challenges of molecular phylogenies and clocks are reviewed.

-

•

New possible calibration points for molecular clocks are suggested.

1. Introduction

Modern cyanobacteria constitute an ancient and well-diversified bacterial phylum, with unique complex morphologies and cellular differentiation. They play a key role in food webs as primary producers performing oxygenic photosynthesis. Cyanobacteria also played a major role in early biogeochemical fluxes and in Life and Earth evolution. They are the only prokaryotic organisms that perform oxygenic photosynthesis, and are thus generally held responsible for the rise of oxygen in the atmosphere and oceans around 2.4 Ga, during the so-called Great Oxidation Event (GOE [1,2]), facilitated by geological processes [3]. Oxygenic photosynthesis has enabled the oxygenation of oceanic and terrestrial niches, and the diversification of complex life [4]. Indeed, most modern eukaryotes need a minimal concentration of molecular oxygen to synthesize their sterol membranes [5]. They diversified from a last eukaryotic common ancestor (LECA), an aerobe protist with a mitochondrion [6]. Further increased oxygen concentration was required for the metabolic activity of mobile macroscopic metazoans [7]. At least 1.05 Ga ago, oxygenic photosynthesis spread among some eukaryotic clades, giving rise to diverse types of algae and later to plants. This important evolutionary step was due to the primary endosymbiosis of a cyanobacterium within a unicellular eukaryote [8,9], and subsequent higher-order endosymbiotic events [10]. The endosymbiotic theory is well supported by biochemical, ultrastructural, ecological and molecular data [11], although the identity and habitat of the cyanobacterial ancestor of the chloroplast are still debated [[12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17]].

Despite the importance of cyanobacteria in the early evolution of Earth and life, fundamental questions remain about their origin, the timing and pattern of their diversification, and the origin of oxygenic photosynthesis, ranging from the Archean to the GOE [18]. One crucial problem to solve is the discrepancy between the unambiguous cyanobacterial fossil record, starting at 1.9 Ga, the GOE at 2.4 Ga, and the report of several older geochemical data suggestive of oxygenic photosynthesis ([19]; but see Ref. [20]) [[21], [22], [23], [24], [25]]; and [26,27].

Several types of evidence are used to reconstruct the fossil record of cyanobacteria, but all have their limitations and challenges. Stromatolites are usually associated to cyanobacterial activity. However, although conical stromatolites seem to plead for oxygenic photosynthesis [28], others types of stromatolites and microbially induced sedimentary structures (MISS) [[29], [30], [31]] may have been produced by non-cyanobacterial lineages, such as anoxygenic phototrophs [28,32], or by/in association with methanotrophs [33]. This suggests that stromatolites and MISS are not necessarily indicative of cyanobacteria activity, and perhaps not even of photosynthesis [34]. Biomarkers (fossil molecules) can indicate the presence of metabolisms such as oxygenic photosynthesis, but they are preserved only in well-preserved unmetamorphosed rocks, and contamination is a challenge [35]. Among those, lipids such as 2-methyl-hopanes are produced by cyanobacteria [36] but not only [37], and pigments such as porphyrins with N isotope composition [38]. Other geochemical (redox and isotopic) proxies can also inform on the presence of molecular oxygen in the water column or biologically-induced isotopic fractionation due to oxygenic photosynthesis, but their interpretation is often debated. Finally, microfossils may provide direct evidence for cyanobacteria, but their identification is often ambiguous. At the present time, the cyanobacterial identity of only three fossil taxa is not debated: Eoentophysalis, Eohyella and Polybessurus. Eoentophysalis belcherensis is the oldest microfossil interpreted with certainty as a cyanobacterium [39]. This microfossil has been described from 1.89–1.84 Ga silicified stromatolites of the Belcher Supergroup, Hudson Bay, Canada [39].

Microbiology of modern cyanobacteria pairs the geological and paleobiological approaches. The accumulation of modern cyanobacterial genetic data in public databases increasingly allows phylogenetic reconstructions and molecular clock analyses aimed at estimating the origin of the phylum and the origin of oxygenic photosynthesis. However, due to the lack of tree calibrations from the fossil record, contamination of genetic sequences, chosen dataset, and limitations or differences in models, these estimates are quite variable [40]. Thus, discrepancies between the geological and fossil records and molecular phylogenies remain, and the origin and evolution of cyanobacteria, oxygenic photosynthesis, and the chloroplast are still debated.

In this paper, we review classic and new biosignatures of cyanobacteria, critically assess their fossil record, and suggest possible new calibration points for molecular clocks. We also briefly discuss molecular phylogenies, molecular clocks and their discrepancies. We finally make some suggestions for future research, to improve our understanding about the evolution of cyanobacteria and its consequences on Earth and biosphere evolution.

| Fundamental and unresolved questions regarding the early evolution of cyanobacteria |

|---|

| What are the timing, pattern, and environment of cyanobacteria origin and evolution? How to interpret the discrepancies between the fossil record and molecular phylogenies, and how to reconcile these records? What are the origin and timing of oxygenic photosynthesis? Which among geochemical redox proxies and stromatolites are reliable indicators of oxygenic photosynthesis? What is the origin, timing, and environment of chloroplast acquisition by endosymbiosis and evolution of eukaryotic photosynthesis? |

2. Identification of cyanobacteria in the fossil record

Paleontologists have to rely on information other than the genomic data and internal cellular organization to identify the biological affinities of early microfossils. In some cases, conventional biosignatures such as morphology, division mode, presence of ornamentation, ultrastructure, and chemistry of carbonaceous cell walls, combined with their distribution pattern within the hosting rocks and the characteristics of their preservational environments may help deciphering their biological affinities [[41], [42], [43]].

Recently, new cyanobacterial signatures, such as intracellular biominerals, molecular fossils of lipids and pigments, and isotopic signatures of carbon and nitrogen, measured on single molecules or whole microfossils, were proposed as tools to better constrain the early evolution of cyanobacteria and their role in early ecosystems. These conventional and new biosignatures of cyanobacteria are discussed below.

2.1. Morphology and division pattern

Cyanobacteria were traditionally described as algae and referred to as ‘Cyanophyta’ or ‘Blue green algae’. Until the end of the 20th century, the nomenclatural system of cyanobacteria followed the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature. In the late seventies, Stanier and colleagues [44] recognized the prokaryotic nature of the cyanobacteria and proposed to follow the International Code of Nomenclature for Bacteria. According to the Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, and following the Stanier approach and Rippka et al. (1979) [45] concepts, cyanobacteria were divided into two groups: unicellular and multicellular filamentous cyanobacteria; and five subsections based on morphological criteria, and corresponding to five former cyanobacterial orders: Chroococcales (section I) and Pleurocapsales (section II) harbor unicellular cells, which divide by binary fission in one or multiple plans and are solitary or arranged in colonies. Pleurocapsales can also produce small easily dispersed cells (baeocytes) after division by multiple fissions. Within the multicellular filamentous cyanobacteria, Oscillatoriales (section III) have only vegetative cells arranged in filaments, whereas Nostocales (section IV), and Stigonematales (section V) are capable of producing specialized cells, the heterocytes, which allow N-fixation in an anoxic compartment; or can exhibit environmental stress resistant cells called akinetes. Besides, cyanobacteria from section V are also characterized by their ability to divide in more than one plane and form true branched trichomes [45].

Since that time, the taxonomic classification of cyanobacteria has been continually reevaluated with the development of electron microscopy and genetic characterization methods [46]. The classification into subsections is practical but does not reflect phylogeny because they are not all monophyletic except for the Nostocales and Stigonematales.

Interpreting microfossils as cyanobacteria is generally based on morphological criteria, and their mode of division. However, the simple shape of many microfossils makes an unambiguous identification very difficult [40]. The size of cyanobacteria cells or filaments may be used as a taxonomic criterion for microfossil biological affinity. However, microfossil size does not correspond exactly to the size of living microorganisms due to modification by taphonomic processes, including diagenesis, collapsing and flattening [47]. Moreover, different fossil and modern groups of bacteria, cyanobacteria and eukaryotic algae have overlapping size ranges. Therefore, microfossil size alone does not constitute a reliable criterion for the interpretation of a microfossil as a cyanobacterium [48] or even as a prokaryote or a eukaryote [49].

Cyanobacteria form spheroidal or rod-shaped cells, filaments or tubes. Some of them occur as spiral filaments (e.g. Spirulina, modern counterpart of Obruchevella [50]) but this morphology also occurs in other bacteria (Leptospira [51]). Cyanobacteria from the Nostocales and Stigonematales orders may present some of the most complex morphologies among prokaryotes, including specialized cells such as larger elongated cells with thicker walls (akinetes) and round cells in or at the end of the filament (heterocytes, fixing nitrogen). The complex multicellular filamentous forms of nostocalean and (uniseriate or multiseriate) stigonematalean cyanobacteria may also display false or true branching. These more complex cyanobacteria may present unique characters allowing to not only identify their fossils as cyanobacteria, but also as specific cyanobacterial clades, more useful as calibrating points.

However, most cyanobacteria have simple morphologies, widespread in the three domains of life. Simple prokaryotic shapes may lead to erroneous interpretations since abiotic processes, such as mineral growth, fluid inclusions, organics migration, or interstitial spaces between grains, can mimic biogenic forms [40,47,[52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57]]. Once the biogenicity of a microfossil is established, morphological observations need to be combined with other criteria, including the wall ultrastructure and molecular composition, in order to confirm unambiguously its identity [58,59].

The division pattern of fossil cells, when preserved, indicates their reproduction, and in some cases, may be indicative of particular taxonomic groups [60,61]. Cyanobacteria reproduce asexually by binary or multiple fissions. Multiple fissions may lead to the formation of baeocytes, which are small cells formed within the parental cell [62]. They can also divide in two or three planes of division, such as Entophysalis spp., the modern counterpart of Eoentophysalis. Moreover, some cyanobacteria occur as colonies either within (e.g. Gloeocapsa spp., modern counterpart of Gloeodiniopsis) or without (e.g. Cyanobium spp., Synechococcus spp., and Synechocystis spp.) a thick polysaccharide envelope. They can also present more or less organized and dense aggregates (e.g. Microcystis spp., modern counterpart of Eomicrocystis) and even cells organized as tablets (e.g. Merismopedia spp.). Some cyanobacteria can also reproduce with the aid of hormogonia, which are short filaments resulting from break up of longer filaments [63]. Trichomes are ensheathed individual filaments [63].

2.2. Ultrastructure

The wall ultrastructure of modern cyanobacteria consists of a peptidoglycan layer of varying thickness in the periplasmic space between a cytoplasmic and an outer membrane, with generally an external S-layer [64]. In some cases, a transparent or pigmented exopolysaccharidic (EPS) envelope, the so called sheath, may surround cells, filaments or colonies. Cyanobacterial EPS includes two forms, one attached to the cell wall and one released in the environments. They may be composed by up to twelve different monosaccharides, including pentoses, hexoses, and acid hexoses as well as methyl sugars and/or amino sugars (e.g. N-acetyl glucosamine, 2,3-O-methyl rhamnose, 3-O-methyl rhamnose, 4-O-methyl rhamnose, 3-O-methyl glucose, see Ref. [65] for a review). In the fossil record, sheaths of cyanobacteria are very common given that they are more readily fossilized, or less easily degraded, than the unsheathed ones [66]. The association of sheaths with clay minerals is more frequent than with unsheathed cyanobacteria, which helps the preservation of these structures [67,68]. This association would be due to differences in the chemical composition between the EPS and the sheath, and the rapid coating of sheaths [67]. Precipitation of other minerals such as nano-aragonite [68] or silica [69] may also enhance preservation.

As phototrophs, all cyanobacteria but Gloeobacter spp [70]. possess internal membranes called thylakoids hosting the photosynthetic apparatus, the two photosystems and their pigments. The arrangement of the thylakoids in cells is well organized and coincide with cyanobacterial lineages taxonomy [71]. For example, in tested strains from Nostocales/Stigonematales thylakoids are coiled and concentrated at the periphery [71]. Since cyanobacteria are the only oxygenic photosynthetic organisms among prokaryotes, the presence of preserved thylakoids in microfossils would be a reliable criterion to confirm that they were able to make this type of photosynthesis [72]. So far, ultralaminae interpreted as thylakoids based on their stacking and thickness, were preserved in microfossils as old as 155 Ma [72]. In acid extraction of 600 Ky microbial mats also revealed the resilience of thylakoids displaying their concentric structure over the hosting cell walls [68]. In both cases, the preservation of thylakoids made of lipids, pigments and proteins was favored by clay minerals ([68,72] and discussion therein). Moreover, although eukaryotes also have thylakoids, they are compartmentalized in chloroplasts and often are arranged differently than in cyanobacteria. Therefore, the distinction between cyanobacterial and eukaryotic thylakoids would be possible in fossils if they are preserved [72].

2.3. Paleoecology and behavior

Geochemical proxies may provide indirect evidence for oxygenation, at the planetary scale, such as the GOE, or at the scale of basins [[73], [74], [75], [76], [77]], and permit the reconstruction of the evolution of paleoredox conditions. However, as mentioned above, their interpretation can be challenging and do not necessarily imply the existence of oxygenic photosynthesis. In the best cases, they represent average values of local conditions over a relatively large time scale compared to the life span and sedimentation of individual taxa within a given microfossil assemblage (which itself also represents a time average, biased by taphonomy). Thus, establishing the paleoecology of fossil assemblages is difficult, although combining micropaleontology and geochemistry at high-resolution along a paleoenvironmental gradient may be informative [54,75], review in Ref. [78]. Hence, examining the consistent trends in distribution of some microfossil taxa in photic zones, in silicified stromatolites or other carbonates, or in microbial mats preserved in siliciclastic rocks, might give a hint to their metabolism and point to (anoxygenic or oxygenic) photosynthesis. Nevertheless, paleontologists and biologists have to keep in mind that the paleoecology of fossil organisms might differ from their modern relatives.

At the microscale, the distribution and the orientation of microfossils within rocks may also provide insights about their ecology [41]. Moreover, their orientation might help to infer the behavior of microfossils, such as phototropism of filaments erected towards the light or chemotropism, rock-boring by endolithic microbes, mat-building benthic microbes, or plankton settling down with no preferential orientation [79,80]. For example, Green et al. [81] and Golubic and Seong-Joo [61] concluded that Eohyella was a euendolithic cyanobacterium owing to its orientation in oolithes, by analogy with its modern counterpart, Hyella [41]. Euendoliths are rock-inhabiting microorganisms, which dissolve mineralized substrates to penetrate the rock [82], in contrast to other endoliths, e.g. chasmoendoliths, which are endoliths that colonize existing rock fissures [82].

2.4. Molecular fossils

Molecular fossils include complex organic molecules produced only by biology and, in some cases, are indicative of particular metabolisms or lineages [83]. Cyanobacteria produce lipids (2-methyl-hopanes – [83,84] and pigments that can potentially be preserved in the unmetamorphosed geological record [35,36]. So far, the lipids 2-methyl-hopanes were extracted from bitumen in black shales as old as 1.6 Ga (McArthur basin, Australia) [83,84]. Their oldest record at 2.7 Ga [85] was reassessed as younger contaminants [86,87]. These fossilized lipids were first attributed to cyanobacteria [84], but it is now acknowledged that they might be signatures of other bacterial lineages [37].

Pigments are also used as signatures for (anoxygenic and oxygenic) photosynthesis. More precisely, the presence of ancient chlorophylls can be detected by the preservation of their nitrogen-containing tetrapyrrole (porphyrin) core. Moreover, some fossilized forms of carotenoids, such as okenane and isorenieratane evidence the presence of purple S-bacteria, green S-bacteria and other bacterial lineages (incl. cyanobacteria) [83]. Even if they are not unique to cyanobacteria, their report shows pigment can be preserved in relatively old unmetamorphosed rocks.

The oldest porphyrins reported so far are preserved in shales of the 1.1 Ga Taoudeni basin, Mauritania [38], which also preserves exquisite microfossils, including eukaryotes and cyanobacteria [88]. These fossilized pigments exhibit a specific N isotope fractionation indicating a cyanobacterial source and permit to suggest that cyanobacteria were the dominant primary producers in mid-proterozoic oceans [38].

Other UV-protective (sunscreen) pigments may be used as signature for bacterial life, such as the mycosporin-like amino acids (MAAs), and two colored molecules specific of cyanobacteria: scytonemin and gloeocapsin. For instance, the combined analyses of modern cultures and fossil (4500 years BP) microbial mats of cyanobacteria from Antarctica revealed that cells and pigmented filamentous sheaths can withstand acetolysis (used to isolate them from the mineral matrix) and retain their molecular signature identified by FTIR microspectroscopy [68]. They are also preserved in siliciclastic sediments by precipitation of nano-aragonite and clay minerals [68]. FTIR microspectroscopy of microfossils enables the non-destructive analysis of the biopolymer composition of cell walls or sheaths. Comparison with taxonomically informative polymers unique to particular modern clades permit to identify the microfossils, in combination with the morphology and wall ultrastructure [58]. However, the scarce knowledge of the composition of pigments, preservable cells, cysts and other structures produced by modern microorganisms, and of their transformation and alteration through fossilization, limits this approach. Moreover, high temperature and pressure (metamorphism) after burial can alter even more or erase original biological properties [89]. Raman microspectroscopy enables estimating the temperature at which the organic material has been submitted (e.g. Ref. [90]), which is necessary to interpret properly the spectra obtained by FTIR microspectroscopy [89]. Raman spectroscopy also permits to characterize molecules in modern organisms, including cyanobacteria [68,[91], [92], [93], [94]]. Scytonemin is a molecule consisting of phenolic and indolic subunits [95]. Today it is notably biosynthesized in benthic filaments of Calothrix sp. [68], and in the endolithic cyanobacteria Hyella sp. and Solentia sp., from coastal carbonates [93]. It may be a promising signature of cyanobacteria given that it can be fossilized [68,96]. In older deposits from Antarctica, derivatives of scytonemin and carotenoids can be extracted from 125000 years BP sediments [97]. However, the preservation potential of scytonemin in older rocks is not known. Artificial taphonomic experiments of decaying cyanobacterial cultures showed the recalcitrance of filamentous polysaccharide sheaths, possibly helped by the presence of pigments [66]. However, in lake sediments from Antarctica, both brown (scytonemin-rich) and transparent (scytonemin-poor) filamentous sheaths were well preserved; hence, scytonemin probably was not the factor driving their preservation [68].

Gloeocapsin, an enigmatic pigment detected in the thick sheath enveloping colonies of the cyanobacterial genus Gloeocapsa growing on carbonate surfaces [93] and in lichens (with cyanobacterial symbionts), might also become a useful indicator, but its molecular composition remains to be characterized and its preservation potential is currently unknown [93].

2.5. Isotopic fractionation

Carbon isotopes fractionation do not permit to discriminate oxygenic photosynthesis from other metabolisms that have overlapping range of fractionation, except for methanogenesis [98,99]. At the microscale, C and N isotopic composition can be measured on single microfossils with undisputed biogenicity [[100], [101], [102]] and might reveal some information on inferred paleobiology and metabolism, but only when combined with their morphology, ultrastructure, molecular composition, paleoecology and behavior.

Analyses of N isotopic fractionation measured on molecular fossils can also indicate metabolism and cyanobacterial affinity. Phototrophic organisms have a specific nitrogen isotopic offset between total biomass and chloropigments [38]. Based on laboratory experiments, this offset is independent of the nitrogen source (NH4+, N2, or NO3−) and its isotopic composition and from redox conditions during cell growth. The N isotopic offset remains relatively constant within different phototrophic organisms such as cyanobacteria, bacteria, red or green algae or plants, and thus may help identify the source organisms. This offset was notably measured on in 1.1 Ga porphyrins, permitting to relate them to cyanobacteria [38].

2.6. Intracellular biomineralization

Passive biomineralization leads to precipitation of minerals on filaments, sheaths, or cells and enhance their preservation potential but is not specific of particular microorganisms [103,104]. Active biomineralization is controlled by the cell or the organism and might be indicative of its metabolism and taxonomic identity. In modern oceans and alkaline lakes, some cyanobacteria have the capacity to form beads of intracellular Ca-carbonates [57,105], but their preservation potential is unknown. Some extant cyanobacteria also have the capacity to produce intracellular ferric phosphates [106]. In the 1.88 Ga Gunflint Formation, Canada, specific microfossil taxa preserved in silicified stromatolites contain internal Fe-silicate and Fe-carbonate nanocrystals, absent from the external wall surfaces. This feature and its distribution pattern are consistent with intracellular biomineralization, with subsequent recrystallization, and not with known patterns of diagenesis. Thus, the combination of large size, morphology and intracellular Fe biominerals is consistent with a cyanobacterial affinity, and not with other known Fe-mineralizing microorganisms [107]. High-resolution observations, as illustrated in Ref. [107], might possibly reveal new cyanobacteria signatures at the nano-scale, in the rock record.

3. The fossil record

Microfossils interpreted as cyanobacteria have been reported in rocks as old as the early Archean, but their biogenicity and interpretation is highly debated. The necessity of reliable criteria for the study of microfossils is well illustrated with the famous controversy surrounding the “microfossils” from the 3.45 Ga Apex Chert, Australia [108]. These traces interpreted as fossil cyanobacteria based on their morphology and the geological context [108] were subsequently reassessed either as pseudofossils [[109], [110], [111]], contaminants [48], mineral artefacts [53], or microfossils [[112], [113], [114]] and the geological context was revised [110].

In this section, we discuss a selection of (1) unambiguous cyanobacteria microfossils for which morphological features and habitats coincide strikingly with modern lineages, (2) probable and possible cyanobacteria microfossils that share morphological similarities both with a taxon belonging to the cyanobacterial phylum and with other lineages belonging to another phylum or domain of life. The limited number of preservable characters, along with their taphonomic alteration, and possible morphological convergence, limits the interpretation of the fossil record. Therefore, additional signatures would strengthen the confidence in the identification of fossil cyanobacteria. Table 1 summarizes the morphology, dimensions, habitats, and geological occurrences of the fossil taxa discussed below and their possible modern counterparts. Supplementary Table 1 summarizes the geochronological information dating these fossil occurrences.

Table 1.

Summary of microfossil morphological features, habitat, occurrences and their modern analogues.

| Microfossil | Morphology | Dimensions (μm) (length x width) |

Habitat | Occurrences Formation/Group, (age in Ga), country |

Modern analogue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anhuithrix magna | Uniserial, straight, curved, bent or twisted filament. Presence of globose cells (akinetes) in or at the end of the filament. In aggregates, filaments are in a common mucilaginous matrix. If isolated, trichomes may be enveloped by an extracellular sheath (thin and non-lamillated). | Filament: up to 2 cm x 141-615 Cells: 56–425 × 113-614 Globose cells: 364-800 |

Transitional to offshore zones. Benthic organism. | Liulaobei Fm (0.84), North China [128] | Nostocales and Stigonematales |

| Archaeoellipsoides | Ellispoidal vesicle with a smooth or ribbed wall. With rounded, flat or slightly depressed ends, Solitary or in groups | 50–100 × 15-25 | Peritidal platform | Francevillian Group (2.1–2.04), Gabon [135]; McArthur Group (1.653–1.647), Australia [136]; Salkhan Limestone (1.6), India [173]; Gaoyuzhuang Fm Jixian section (∼1.58), China [144]; Kotuikan Fm & Yusmastakh Fm (1.5), Siberia [133]; Wumishan Fm (1.425), China [174]; Dismal Lake Group (1.4), Canada [175]; Debengda Fm (1.265–1.04), Siberia [176]; Shorikha Fm (1), Siberia [177]; Kirgitey & Lopatinskaya Fm (0.8), Siberia [178]; Chichkan Fm (0.65), South Kazakhstan [179] |

Anabaena (akinetes) Possible Nostocales or Stigonematales |

| Eoentophysalis belcherensis | Spheroidal to ellipsoidal cells arranged in dyads, tetrads, octets or in loose or palmelloid colonies (spherical, hemispherical or mushroom-like shape), Division by binary fission in three perpendicular planes. The outer layers of colonies are pigmented. | 2,5-9 | Intertidal, mudflats and shallow sub- and supratidal zone | Belcher Supergroup (1.89–1.84), Canada [39]; Amelia Dolomite (McArthur Group – 1.653–1.647), Australia [180]; Kotuikan Fm & Yumastakh Fm & Avzyan Fm (1.5), Ural Mountains [133]; Kheinjua Fm (1.5–1), India [181]; Balbirini Fm (1.483), Australia [182]; Gaoyuzhuang Fm & Wumishan Fm (Changcheng Group – 1.425), China [139]; Sukhaya Tunguska Fm (1), Siberia [154]; Bitter Springs Fm (0.81–0.79), Australia [140]; Deoban Limestone & Jammu Limestone Fm (1–0.967), India [183]; Jiudingshan Fm (0.8), China [184]; Min’Yar Fm (0.79–0.68), Southern Ural Mountains [185]; Svanbergfjellet Fm (0.75–0.7), Spitsbergen [171]; Narssârssuk Fm (0.688), Greenland [186]; Ediacaran Shuurgat Fm (0.635), Mongolia [187] |

Entophysalis Chrooccocales |

| Eohyella | Uni-, bi- or multiseriate pseudofilament which penetrates the substrate. Branched or unbranched. | 4–21 × 8,5-<50 | Euendolithic in silicified ooids, intertidal and subtidal environments | Dahongyu Fm (Changcheng Group – 1.63), China [126]; Koldaha Shale Fm (1.5–1), India [188]; Backlundtoppen Fm (0.8–0.7), Spitsbergen [189]; Eleonore Bay Group (0.95–0.68), Greenland [81]; Red Pine Shale unit (Uinta Mountains Group – ∼0.75), USA [190]; Nagod Limestone Fm (0.625 or 0.75–0.65), Central India [191] |

Hyella Pleurocapsales |

| Eomicrocystis | Subspheroidal colonies, or packets, of spheroidal to ellipsoidal vesicles with a single layered wall. | 0,8–6,5 or 15-17 | Subtidal to intertidal environment | Kotuikan Fm (1.48–1.47), Siberia [138]; Widely distributed in Meso-Neoproterozoic |

Microcystis Chroococcales |

| Gloeodiniopsis | Spheroidal vesicles, sometimes solitary but commonly in colonies. Vesicles are usually with multilayered envelope. | 0,8-8 | Intertidal environment | Bitter Springs Fm (0.81–0.79), Australia [140]; widely distributed in Meso-Neoproterozoic |

Gloeocapsa or Chroococcus Chroococcales |

| Obruchevella | Tightly or loosely coiled empty tube with loose or regular cylindrical spirals. | Width: 0,8-8; 11–25; 27-55 |

Intertidal to supratidal; in open shelf; in tidal flats | Gaoyuzhuang Fm (∼1.58), China [144]; Kamo Group (1.5–1.05), Russia [192]; Thule Supergroup (1.3–1.2), Greenland [193]; Avadh Fm (1.25–1.15), India [194]; Atar/El Mreïti Group (1.1), Mauritania [75]; Mbuji-Mayi Supergroup (1.03–0.95), DRC [165]; Bylot Supergroup (1.092 ± 59 Ma), Canada [163]; Burgess Shale (0.5), Canada [147]; | Spirulina for narrower diameter, and Arthrospira for larger forms, Oscillatoriales, or eukaryotes |

| Oscillatoriopsis | Uniseriate and unbranched trichome, without sheath, formed by discoidal to cylindrical cells whose length is less or equal their diameter. Apices may sometimes be tapered. Solitary or in mat-like mass. | Cell length: 1,8-12 Trichome width: 1-11; 25; 63 |

Shallow water marine environments, subtidal shelf environments, peritidal flat and pluvial lakes | Bitter Springs Fm (0.81–0.79), Australia [140]; widely distributed in Proterozoic |

Oscillatoria, Oscillatoriales or other bacteria |

| Palaeolyngbya | Uniseriate unbranched trichome formed by discoidal to cylindrical cells. Trichome surrounded by an uni- or multilayered smooth sheath. | 2–8 x 8-85 | Peritidal flat, restricted tidal flat or open shelf | Bitter Springs Fm (0.81–0.79), Australia [140]; Widely distributed in Proterozoic |

Lyngbya Oscillatoriales, or other bacteria |

| Polybessurus | Multilamellated cylindrical stalk with concave and regularly spaced layers and with funnel-like shape. The top of the stalk is open or is ended by preserved cells. | Cell: 25–85 × 20-60 Stalk: 20–600 × 15-150 |

Intertidal to subtidal environments | Avzyan Fm (1.35–1.01), Russia [123]; Society Cliffs Fm (1.2), North America [169]; Hunting Fm (1.2), North America [195]; Sukhaya Tunguska Fm (1), Siberia [196]; Seryi Klyuch Fm (1.1–0.85), Siberia [197]; Skillogalee Dolomite (0.77), Australia [198]; Svanbergfjellet Fm (0.75–0.7), Spitsbergen [171]; Eleonore Bay Group (0.95–0.68), Greenland [121] | Cyanostylon -like, Pleurocapsales |

| Polysphaeroides filiformis | Spheroidal vesicles arranged in a filamentous aggregate surrounded by a common sheath closed at both ends. Cells are dispersed or arranged in pairs, tetrads, octets or in colonies. Colonies sometimes arranged in pairs forming pseudobranched filament. | Sheath: 300–500 x 7–13,5 Cell width: 3,5-8 |

Shallow subtidal shelf | Ust’-Il'ya Fm & Kotuikan Fm (1.48–1.46), Siberia [199]; Mbuji-Mayi Supergroup (1.03–0.95), DRC [165]; Miroedikha Fm (0.85), Siberia [162]; Vychegda Fm (0.635–0.55), East European Platform [200] |

Stigonema robustum, Stigonematales, or green and red algae |

| Siphonophycus | Cylindrical empty tube, unbranched with non-septate. Solitary or generally arranged in mass. | ≤120 x 1–3,7 | Subtidal environments | Bitter Springs Fm (0.81–0.79), Australia [140]; Widely distributed in Proterozoic |

Oscillatoria –like, Oscillatoriales, Or other bacteria |

3.1. Unambiguous microfossils of cyanobacteria

Although microfossils attributed to cyanobacteria are abundant during the Proterozoic, many of them are identified with some ambiguities. Knoll and Golubic [41] determined a confidence range for these microfossils, since most of them are identified based on morphology, sometimes coupled with their occurrence in the photic zone, despite the possibility of morphological convergence. So far, only three taxa are unambiguously identified as cyanobacteria: Eoentophysalis, Polybessurus and Eohyella, because they also present distinctive modes of division.

3.1.1. Eoentophysalis

The cyanobacteria fossil record starts around 1.9 billion years ago with the most emblematic Proterozoic microfossil identified so far with certainty as a cyanobacterium, Eoentophysalis belcherensis (Fig. 1A). E. belcherensis was first described in the 1.89–1.84 Ga Belcher Supergroup, Hudson Bay, Canada, where this colonial microorganism formed mats in silicified stromatolites [39,115].

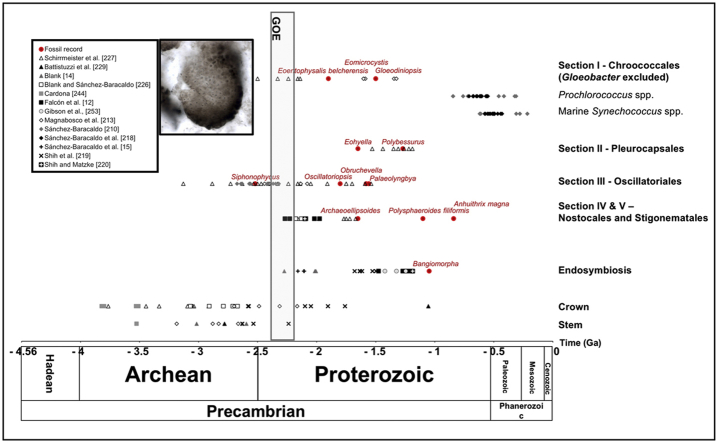

Fig. 1.

Microphotographs of fossils with some of their modern analogues. A) Eoentophysalis belcherensis from the 1.89–1.84 Ga Kasegalik Formation, Belcher Supergroup, Canada; B) Polybessurus from the 800-750 Ma Draken Formation, Svalbard, photo courtesy of A. H. Knoll; C) Cyanostylon, the modern analogue of Polybessurus, photo courtesy of A. H. Knoll; D) Eohyella, the euendolithic cyanobacterium from the 950-680 Ma Eleonore Bay Group, central East Greenland, photo courtesy of A. H. Knoll; E) Hyella, the modern analogue of Eohyella, photo courtesy of A. H. Knoll; F) Obruchevella from the 1.03–0.95 Ga Mbuji-Mayi Supergroup, Democratic Republic of the Congo, photo courtesy of B. K. Baludikay; G) Archaeoellipsoides from the 1.48–1.3 Ga Billyakh Group, Siberia, photo courtesy of A. H. Knoll; H) Stigonema robustum, the modern analogue of Polysphaeroides filiformis, photo courtesy of T. Hauer; I) Polysphaeroides filiformis of the 1.03–0.95 Ga Mbuji-Mayi Supergroup, Democratic Republic of the Congo, photo courtesy of B. K. Baludikay. Scale bars = 20 μm in A, B, E, F, G and H; = 10 μm in C; = 100 μm in D; = 50 μm in I.

The identification of E. belcherensis is based on comparison with the modern cyanobacterium genus, Entophysalis [115]. Based on morphology, Entophysalis belongs to the order Chroococcales [116] and consists of coccoidal unicells forming characteristic pustular palmelloid colonies. The morphology of Entophysalis colonies is due to its mode of cell division by binary fission in three perpendicular planes. Modern Entophysalis produce highly hydrated exopolymer envelopes that expand during cell division. With this expansion, the older exopolymer envelopes are moved outward. Another particularity of Entophysalis colonies is the presence in the outer layers of the colonies of a yellow-brown UV-protecting pigment, scytonemin, that is produced by the most external cells for protection against intense solar radiation [117]. Entophysalis cells grow in the form of mats in the intertidal range of shallow marine basins [115,117]. This cyanobacterial genus may also precipitate micrite in stromatolites such as those in the shallow hypersaline Hamelin Pool, Shark Bay (Western Australia), in association with other cyanobacteria but also other Bacteria, and halophilic and methanogenic Archaea [34,[117], [118], [119]]. Entophysalis is dominant in pustular mats, but also in smooth and colloform coccoidal mats and precipitate micrite, playing a key role in lithifying the stromatolites compared to filamentous forms [34]. They are also reported to enable the stabilization of loose sandy substrate and contribute to the formation of stromatolites by passively trapping sediment particles on the mat's surface between its irregularities [115,117].

The microfossils Eoentophysalis belcherensis were discovered in silicified stromatolites from the Kasegalik and McLeary formations of the Paleoproterozoic Belcher Supergroup (1.89–1.84 Ga). The geological context of these two formations corresponds to intertidal mudflats as well as shallow subtidal and supratidal zones [39,120]. These paleoenvironments are thus comparable to the modern ecological niches occupied by Entophysalis. In addition, E. belcherensis and Entophysalis have similar morphological attributes and, both consist of coccoidal cells showing the same size range (Table 1). They both reproduce by binary fission in three perpendicular planes with a high production of exopolymeric envelopes. Finally, both fossil and modern colonies present the same characteristic warty (pustular) mamillate shape and darkened external layers [115]. However, the nature of this dark outer layer in the fossil colonies remains to be elucidated, as it could be simply due to desiccation instead of specific pigments [59,115]. The morphology of those cells and colonies occurs exclusively in Chroococcales [41]. Therefore, the combination of those criteria (morphology, development, environment and colony pigmentation) enabled the unambiguous identification of this microfossil.

3.1.2. Polybessurus

Polybessurus is another Proterozoic microfossil unambiguously identified as a cyanobacterium [121]. Polybessurus was formally described from silicified carbonates of the ca. 950-680 Ma Eleonore Bay Group (East Greenland) [121], following Fairchild, who was the first who described Polybessurus in his unpublished PhD thesis [122]. Its oldest occurrence is in the ca. 1.35–1.01 Ga Avzyan Formation, Russia [123].

Polybessurus is a fossil of a coccoidal unicellular microorganism with a very particular morphology unique to cyanobacteria (Fig. 1B). This microfossil is composed of a cylindrical stalk produced by means of asymmetric and unidirectional secretion of extracellular mucopolysaccharide envelopes, growing from within the sediments upward. Ellipsoidal cells, surrounded by multiple envelopes, are present at the higher end of the stalk. The primordial role of this stalk is to maintain the cells at the sediment-water interface [124]. The morphology of Polybessurus resembles a stack of cup shaped envelopes.

This particular morphology with cells jetted upward by the stalk is similar to the modern cyanobacterium Cyanostylon belonging to the order Chroococcales (Fig. 1C). However, Polybessurus reproduced by the formation of baeocytes (smaller cells) which is characteristic of the order Pleurocapsales, but is unlike the modern Cyanostylon [121]. Indeed, the reproduction mode of Polybessurus was inferred from preserved clusters of narrow tubes radiating from the same point. This particularity allows to suggest that those narrow tubes were produced by small cells [121]. Thus, the modern counterpart of Polybessurus is a not yet described Pleurocapsales Cyanostylon-like cyanobacterium discovered in peritidal environments of the Bahama Banks, environments similar to the paleoenvironment of Polybessurus [79]. Actually, it is the discovery of the fossil Polybessurus that permitted to predict the environment where to look for its modern counterpart [121,124]. Taken together, the particular morphology of Polybessurus, its mode of reproduction and ecology enable its affiliation to cyanobacteria, probably within the Pleurocapsales.

3.1.3. Eohyella

The Limestone-Dolomite series of the ca. 950-680 Ma Eleonore Bay Group (central East Greenland) also preserve a group of particular microfossils showing a distinct endolithic behavior [81]. Among them, Eohyella is a coccoidal microfossil forming pseudofilaments (where juxtaposed cells do not share a common wall), sometimes branching depending on the microfossil species, by the juxtaposition of several cells surrounded by extracellular envelopes (Fig. 1D). Eohyella was qualified as an euendolith cyanobacterium because of its orientation within the substrate: they crosscut the substrate laminae [81,125]. Eohyella microfossils occur in oolites and pisolites of shallow peritidal environment. Within the euendolithic cyanobacteria group of the Limestone-Dolomite series, Eohyella was the most abundant genus. So far, its oldest occurrence was found in the 1.63 Ga Dahongyu Formation, China [126].

The morphology, behavior and paleoenvironment of Eohyella are similar to those of the modern genus Hyella (Fig. 1E), which enabled the identification of this microfossil as a cyanobacterium, of the order of Pleurocapsales. In the present day, Hyella is an euendolithic cyanobacterial taxon present in ooids of the shallow subtidal environment in the Bahamas Banks [81].

3.2. Probable and possible cyanobacteria microfossils

Other microfossils are identified with less confidence but still considered as probable or possible cyanobacteria, depending on the authors. They are discussed below in alphabetical order. While analyses of fossil porphyrins suggest that cyanobacteria were the dominant primary producers in mid-proterozoic oceans [38], it is still unknown whether they were planktonic or benthic, and mostly small and coccoidal or filamentous, or both. The geological record seems to preserve mostly benthic cyanobacteria in the form of microbial mats or endoliths, although some microfossils, such as Eomicrocystis, are possible planktonic cyanobacteria. Modern Microcystis colonies overwinter on lake sediment after summer blooms and reinvade the water column in the spring [127]. This alternance of benthic and planktonic stage of life may have evolved early in cyanobacteria.

This review does not illustrate all the Proterozoic microfossils interpreted as cyanobacteria, often displaying simple colonial morphologies also encountered in other bacterial clades. Sergeev et al. [50] list additional taxa such as Eosynechococcus, Leiosphaeridia, Myxococcoides in their extensive review about all the Proterozoic microfossils currently interpreted as cyanobacteria. Here, we discuss those we consider the most relevant, common or distinctive taxa that could be used directly, or after further characterization, as new possible calibration points.

3.2.1. Anhuithrix

Pang et al. [128] described a new mat-forming filamentous microfossil, Anhuithrix magna, from the Tonian Liulaobei Formation (0.84 Ga), North China. They interpreted this fossil as a heterocytous N-fixing cyanobacterium of subsections IV or V (Nostocales or Stigonematales), based on the occurrence of large globose cells, observed between smaller vegetative cells within a filament, or at filament ends. These large cells were interpreted as probable akinetes according to their dimensions (364–800 μm in diameter) and their location in filaments. This microfossil reproduced by the production of hormogonia and grew by binary fission. However, the preservation of those microfossils as carbonaceous compressions might lead to cell deformation, making difficult the interpretation based on size and simple morphology.

This new fossil genus is, as Archaeoellipsoides (discussed below), a promising calibration point for molecular clocks to provide a minimum age of the Nostocales or Stigonematales. Therefore, this probable interpretation should be strengthened by microanalyses (ultrastructure, chemistry) of extracted microfossils to confirm its identity.

3.2.2. Archaeoellipsoides

Nostocales and Stigonematales are modern cyanobacterial orders that, as mentioned above, have evolved specialized cells, the heterocytes [129], and in some cases akinetes [130]. Akinetes, formed from vegetative cells, differ from those by their larger size, a thicker cell wall and absence of cell division. Modern akinetes, in all known species of akinete-bearing cyanobacteria, have an ellipsoidal to cylindrical morphology and range from 2 to 450 μm in length and to 1.8–30 μm in width [128,131]. The microfossils Archaeoellipsoides are cylindrical cells that include several species differing by their size [50] (Fig. 1G). Golubic et al. [132] hypothesized that Archaeoellipsoides from the 1.48–1.3 Ga Billyakh Group (Siberia) were fossil akinetes, based on morphological characteristics (size, elongated shape, and absence of cell division), by comparison with the akinetes of the extant analogue Anabaena. Anabaena, a nostocacean cyanobacterium, produces akinetes ranging from 7 to 90 μm in length and to 1.8–25 μm in width [128,131]. Moreover, Archaeoellipsoides are associated, in the Billyakh assemblage, with short trichomes. Those trichomes were interpreted as possible products of akinete germination [133], but the relationship between the akinetes and the co-occurring trichomes is discussed [134]. Older occurrences include poorly preserved microfossils in the 2.1–2.04 Ga Francevillian Supergroup, Gabon [135] and better preserved specimens in the 1.65 Ga McArthur Supergroup, Australia [136].

However, the simple morphology of Archaeoellipsoides might also occur among other microorganisms, such as some giant Firmicutes, e.g. the parasitic Epulopiscium [137] or green algae, such as Spirotaenia or Stichococcus [134]. Therefore, the identity of Archaeoellipsoides remains to be confirmed by other evidence than morphology alone.

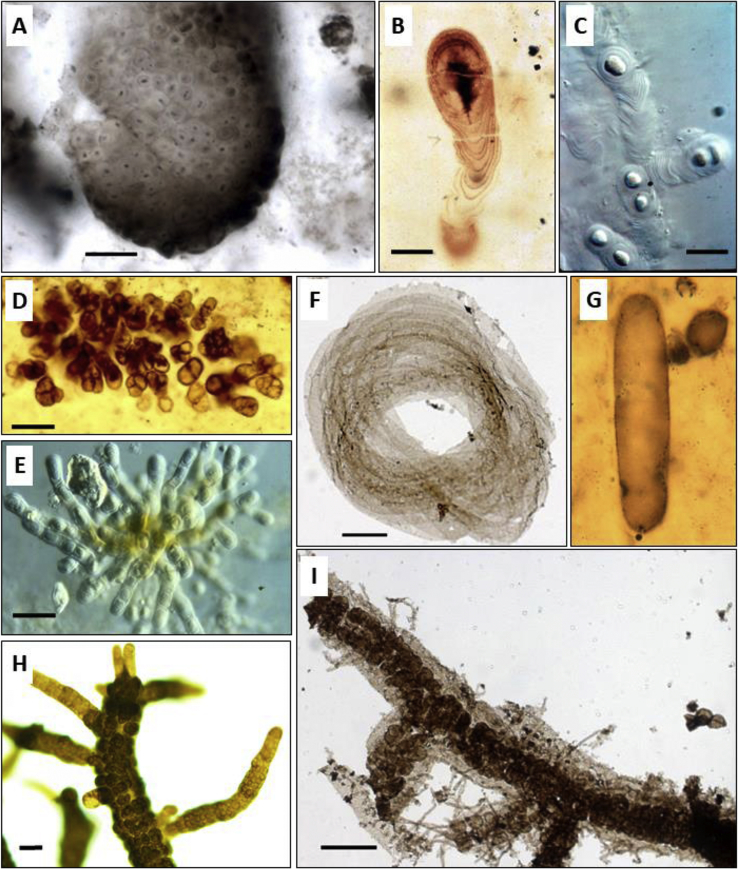

3.2.3. Eomicrocystis

Eomicrocystis is a microfossil genus described in 1984 by Golovenok and Belova [138], and interpreted as a cyanobacteria. It was named according to its possible modern analogue, Microcystis, a planktonic coccoid cyanobacterium that forms colonies in freshwater lakes and ponds [133,138]. Eomicrocystis also formed colonies composed of small spheroidal to ellipsoidal cells (Fig. 2A), but preserved in marine environments. It may dominate assemblages and occur as blooms in specific levels of the 1.1 Ga El Mreiti Group, Mauritania [88]. Sergeev et al. [133] suggested that Eomicrocystis was a junior synonym of the genus Coniunctiophycus that Zhang [139] had also described and interpreted as the fossil analogue of the extant Microcystis. Eomicrocystis’ oldest occurrence is in the 1.48–1.46 Ga Kotuikan Formation, Siberia [133]. However, the simple morphology of this microfossil does not enable a confident interpretation as a cyanobacterium. Indeed, this morphology is also encountered among eukaryotic algae (e.g. Nannochloropsis) [63] and other bacteria.

Fig. 2.

Microphotographs of fossils considered as probable or possible cyanobacteria. A) Eomicrocystis from the 1.1 Ga Atar/El Mreïti Group, Taoudeni Basin, Mauritania. B) Siphonophycus from the 1.48–1.3 Ga Billyakh Group, Siberia; C) Palaeolyngbya from the 1.03–0.95 Ga Mbuji-Mayi Supergroup, Democratic Republic of the Congo, photo courtesy of B. K. Baludikay; D) Tortunema from the 1.03–0.95 Ga Mbuji-Mayi Supergroup, Democratic Republic of the Congo, photo courtesy of B. K. Baludikay. Scale bars = 20 μm.

3.2.4. Gloeodiniopsis

Gloeodiniopsis is also another possible fossil of a benthic chroococcacean cyanobacterium [140]. Its stratigraphic range starts with the ∼1.58 Ga Gaoyuzhuang Formation, China, and the 1.55 Ga Satka Formation, the Southern Ural Mountains [139,141].

Gloeodiniopsis consists of several spheroidal to ellipsoidal vesicles surrounded by a multilayered envelope. They are generally grouped in colonies but they may also occur occasionally as isolated cells. This morphology resembles that of modern Gloeocapsa or Chroococcus. These two possible modern analogues show both a similar morphology but differ slightly by the presence (Gloeocapsa) or the absence (Chroococcus) of a colored sheath and the thickness of this sheath. The distinction between these two modern cyanobacteria is still debated because some consider this difference between Gloeocapsa and Chroococcus as minor [50], and moreover, molecular analyzes show that they both are polyphyletic groups [45,142].

Although the morphology of Gloeodiniopsis is very similar to Gloeocapsa, some green algae may also present a similar morphology, e.g. Volvox [143], Sphaerocystis or Eudorina [63]. Again here, new analyzes of ultrastructure and chemistry, including the presence of unique pigments [93] in microfossils and modern specimens might help the discrimination.

3.2.5. Obruchevella

Obruchevella is a microfossil that consists of an empty helically coiled tube (Fig. 1F). This fossil genus includes several species differing by their tube and spiral diameters. The stratigraphic range of Obruchevella starts in the third member of the ∼1.58 Ga Gaoyuzhuang Formation, China [144]. When preserved as carbonaceous compressions in shale, the helicoidal filaments are compressed into more or less tight spirals. When preserved in 3D in chert, they occur as screw-like coiled filaments [145].

Reitlinger [146] first described Obruchevella specimens as foraminifera. Its biological affinity was however reassessed as cyanobacteria with Spirulina as modern counterpart, a cyanobacterium belonging to the Oscillatoriales [147,148]. The interpretation of Obruchevella was essentially based on its helically coiled morphology and its ecology, both similar to Spirulina, a planktonic helically coiled cyanobacterium. However, this morphology is also known in other cyanobacteria (Arthrospira) [149], and other bacteria, e.g. the parasitic but also free-living helicoidal species of Leptospira [51], Pararhodospirillum [150,151] and in some eukaryotic algae (e.g. Ophiocytium, a Tribophycean alga [63]). Some species of Leptospirales are associated with marine stromatolites [34]. Leptospira has a much thinner diameter (0.1 μm) and does not overlap with the thinnest Obruchevella (0.8 μm). Some Obruchevella microfossils present dimensions similar to Spirulina (tube diameter 0.5–3 μm, see in Ref. [149]), while most other species have sizes close to Arthrospira dimensions (tube diameter 2.5–16 μm, see in Ref. [149]. A few other Obruchevella species have a tube diameter wider than 20 μm, broader than Arthrospira and Spirulina, and may perhaps be closer to eukaryotic organisms. Other organisms in the fossil record also have spiral morphology with a larger size and a eukaryotic interpretation. The Mesoproterozoic specimens of Grypania spiralis, a coiled filamentous fossil, reach macroscopic size and have been interpreted as a eukaryotic organism based on its size, preserved septae and external sheath, and cell length and size suggesting a coenocytic organization. The older 1.9 Ga Grypania are smaller, thinner and do not preserve internal structure, and resemble more ripped-up microbial mat fragments (see review in Ref. [59]).

Thus, although Obruchevella is a probable cyanobacteria, these hypotheses are only based on morphology and size, and would be strengthened by ultrastructure and chemical analyzes.

3.2.6. Oscillatoriopsis

Oscillatoriacean cyanobacteria are reported as the most represented group of cyanobacteria in the fossil record [152]. One of those is Oscillatoriopsis, an unsheathed cellular filament with more or less isodiametric cells (Length:Width ≤ 1) [140,153,154] (Fig. 2D). Oscillatoriopsis microfossils are slightly constricted at intercellular septa [153].

Oscillatoriopsis microfossils are commonly found in shallow water marine environments but they also may be found in lacustrine deposits or pluvial lakes [50,140,155]. The stratigraphic record of this genus starts with the ca. 2.2–1.8 Ga silicified carbonates from the Duck Creek Dolomite Formation, Australia [155].

The interpretation is only based on morphology, similar to modern Oscillatoria. However, this type of simple morphology is also found among other prokaryotes such as Beggiatoa, a sulfide-oxidizing proteobacterium [41,50,155,156] or among eukaryotes such as Ulothrix, a green alga [157]. Oscillatoriacean cyanobacteria often reproduce by the formation of hormogonia. The fossil occurrence of such short filamentous microfossils interpreted as Oscillatoriopsis could support its identificationas hormogonia of oscillatoriacean cyanobacteria [141]. However, other bacteria, again including Beggiatoa, may also produce hormogonia. Therefore, the interpretation of Oscillatoriopsis as an oscillatoriacean cyanobacterium, albeit plausible, is still debated [41].

3.2.7. Palaeolyngbya

Palaeolyngbya is interpreted as a hormogonian oscillatoriocean cyanobacterium microfossil found first in the 0.81–0.79 Ga Bitter Springs Formation, Central Australia [140,158], but its oldest occurrence is in the 1.60 Ga Gaoyuzhuang Formation, China [159], and in 1.48–1.46 Ga Kotuikan Formation, Siberia [160]. It is a sheathed filament with a smooth wall (Fig. 2C). Regular and uniseriate discoidal cells are arranged inside the single sheath [153].

As several other possible cyanobacteria microfossils, Palaeolyngbya has been interpreted as such based only on its morphology [140,161] and therefore is debatable.

3.2.8. Polysphaeroides filiformis

Polysphaeroides is a fossil genus described by Hermann [162], which included several fossil species, until 1994, when Hofmann and Jackson [163] moved nearly all of the species of Polysphaeroides to the genus Chlorogloeaopsis, because of their similar morphology. Only one species remained, Polysphaeroides filiformis [164]. Polysphaeroides filiformis consists of spheroidal cells arranged in a loose multiseriate filamentous aggregate and surrounded by a common envelope with closed ends (Fig. 1I). The colonies formed by the spheroidal cells may branch. The 1.48–1.46 Ga Kotuikan Formation, Siberia, is the oldest formation in which Polysphaeroides filiformis was recorded so far [164].

Polysphaeroides is compared to modern stigonemataleans [164,165], although some authors suggested a possible affinity to eukaryotic algae, either green or red [166], for example the red algae Polysiphonia (Figs. 16–42 in Ref. [63]). However, the morphology of Polysphaeroides filiformis, characterized by a thick sheath surrounding multiseriate filament arrangement and occasional branching, fits the description of the recently re-evaluated modern genus Stigonema [167]. For instance, Polysphaeroides filiformis from the 1.03–0.95 Ga Mbuji-Mayi Supergroup, DRC [165], displays cell shape, arrangement, and diameters, as well as the presence of the thick sheath and the occurrence of branching (Fig. 1I) that are strikingly similar to the modern multiseriate species, Stigonema robustum (Fig. 1H). We consider that this fossil cyanobacterium may represent a good alternative calibration for future molecular clock analyses as modern taxa belonging to this genus form a monophyletic clade. Modern multiseriate Stigonema species including the recently described S. informe, and S. robustum, are generally epilithic [167] while Polysphaeroides filiformis from Mbuji-Mayi Supergroup was associated with intertidal or subtidal environments [165].

3.2.9. Siphonophycus

Siphonophycus is one of the most common filamentous microfossils in the Proterozoic. It is commonly found in shallow water deposits in Proterozoic mat assemblages [41,168], preserved in situ in chert [41,80,124,140,169] or as bundles ripped off mats in shales [54], or as the main stromatolite builders [50]. Siphonophycus is an unbranched, non-septate and empty smooth-walled filamentous sheath [140] (Fig. 2B). Several species are distinguished based on the diameter range of the filamentous sheath [153]. Broad (15–25 μm) filaments of Siphonophycus transvaalensis reported in the latest Archean 2.52 Ga Gamohaan Formation of South Africa were interpreted as non-heterocytous cyanobacteria similar to modern Oscillatoriales [170]. Similar Oscillatoriales-like microfossils occur through all the Proterozoic.

Siphonophycus specimens are generally interpreted as sheaths of oscillatoriacean cyanobacteria. Schopf [140] occasionally observed transverse thickenings that were placed along Siphonophycus filamentous sheaths. Therefore, he suggested that modern counterparts of Siphonophycus microfossils would be LPP-like cyanobacteria (Lyngbya, Phormidium and Plectonema) [140,141,171]. Nevertheless, this simple morphology is also encountered in other bacteria. For example, minute Siphonophycus sheaths may be comparable to Chloroflexi-like photosynthetic bacteria [41,168]. Large Siphonophycus microfossils might also be the remains of filamentous eukaryotic algae [50]. Some Siphonophycus may present a sheath with a thickness of around 2 μm. Thick sheaths are generally common among cyanobacteria and not among other bacterial phyla [172]. They may thus be a criterion of a cyanobacterial affinity for those Siphonophycus specimens, in addition to alternating vertical and horizontal disposition in mats, which may indicate phototropism or chemotropism, a behavior not unique to cyanobacteria [41,134].

4. Molecular dating

The understanding of cyanobacterial phylum evolution has progressed significantly with the emergence of molecular biology techniques and new sequencing technologies. Since the late 90's a myriad of phylogenetic studies based on single loci (i.e., 16S rRNA or some protein) have been published (e.g. Refs. [9,201]). Even if the five major sections of Cyanobacteria were not yet represented in genomic databases, the first studies to use a phylogenomic (i.e. multilocus) dataset were the works of Rodriguez-Ezpeleta et al. (2005) [202] and then of Criscuolo and Gribaldo (2011) [203]. In 2013, the large CyanoGEBA (Genomic Encyclopedia of Bacteria and Archaea) sequencing project led to an improvement in terms of genomic coverage of cyanobacterial taxa, notably by sequencing genomes belonging to sections II and V [201]. Since then, the number of publicly available cyanobacterial genomes has dramatically increased. Yet, their quality, especially contamination of cyanobacterial assemblies by non-cyanobacterial DNA, has gone worse in parallel, which is a problem for phylogenetic analyses [204]. Moreover, the real biodiversity of cyanobacteria is still under-represented in genomic databases, mainly because of a biased sampling in the sequencing effort [205,206]. Nevertheless, since Shih et al. (2013) [201], many authors have taken advantage of these new genomes to carry out phylogenomic analyses [13,15,[207], [208], [209], [210], [211], [212], [213]]. Most of these studies focussed on integrating new genomic data to the same set of 100–200 hundreds loci (but see Ref. [15]). By doing so, few tried to handle the methodological difficulties associated with the use of large-scale data to resolve the phylogeny of old groups such as Cyanobacteria, whether during dataset assembly (e.g., contamination, horizontal gene transfer, hidden paralogy) or phylogenetic inference (e.g., substitutional saturation, compositional bias, heterogeneous evolutionary rate) [[214], [215], [216], [217]], except [203]. Consequently, among the ten phylogenomic studies cited above, only three are in agreement on the cyanobacterial backbone [13,201,210].

4.1. Calibration, models, and datasets

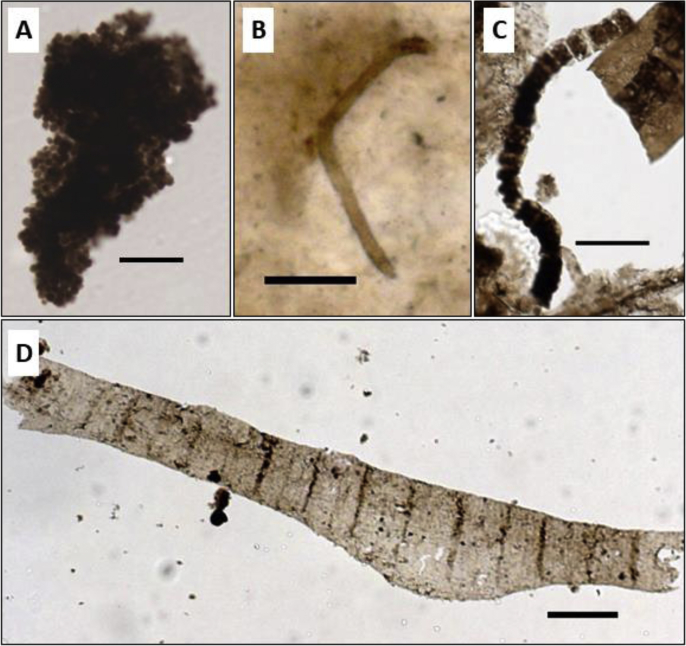

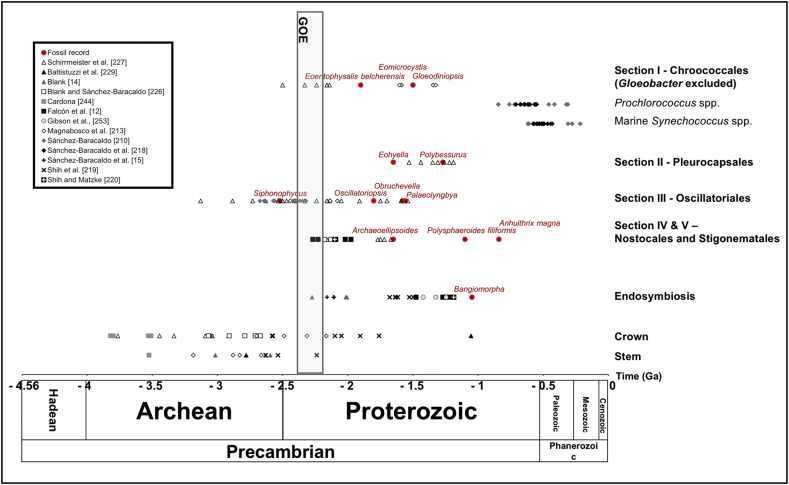

For molecular clock reconstructions, microfossils of cyanobacteria are needed as a source of calibration of the molecular phylogenies. However, only few calibration points are available to date oxygenic photosynthesis, the endosymbiotic event having given rise to the chloroplast, as well as the origin of cyanobacteria. For the latter, estimates range from the early Archean to the GOE, in the Paleoproterozoic (Fig. 3). Beyond the lack of congruence of the phylogenomic studies and the polyphyletic nature of many cyanobacterial groups (including well-known genera such as Synechoccocus and Leptolyngbya), the issue is complicated by the absence in genomic databases of modern counterparts (Entophysalis, Hyella or Cyanostylon-like) of the unambiguous cyanobacteria microfossils (Eoentophysalis, Eohyella and Polybessurus). As we have no reliable indication of the phylogenetic position of these important modern taxa, researchers often use flimsy affiliations as calibration points. Usually, only few cyanobacterial fossils are used as constraints for molecular clock analyses. They include Archaeoellipsoides for monophyletic Nostocales and Stigonematales lineages, and Eohyella for Pleurocapsales lineages, despite the absence of a genetic characterization of the modern counterpart Hyella (e.g. Refs. [210,218]). The occurrence of fossil diatoms is often used for the advent of the endosymbiont Rivularia intracellularis, and the fossil red algae Bangiomorpha for the minimum age of the primary endosymbiosis. Moreover, some authors have chosen not to use cyanobacteria microfossils in their analysis, but instead fossils from eukaryotic lineages such as plants [219], or the occurrence of horizontal gene transfer [213], or the GOE to set a lower bound on Cyanobacteria as a phylum [220]. In a non-exhaustive survey, we observed more than 89 different approaches used to estimate the evolution of cyanobacterial phylum. This diversity of phylogenies, and calibration points, but also of clock models and dating software packages, has led to a large variety of age estimates.

Fig. 3.

Microfossils record of unambiguous, probable and possible cyanobacteria (see text for discussion, Table 1, and Supplementary Table 1), and of Bangiomorpha as an unambiguous red alga, and minimum median age estimates for the divergence of sections I, II, III, IV and V as described by Rippka et al. [45]; for phylogenetic nodes supporting stem and crown group cyanobacteria according to the literature; and for the primary endosymbiosis. Note that the age of Polysphaeroides filiformis considered here corresponds to its record in Baludikay et al. [165].

So far, all the attempts to date the evolutionary events of the cyanobacterial phylum used a fixed-node approach, where researchers manually select nodes to place calibration points. This strategy has the disadvantage of inducing an unmeasurable uncertainty on the inferred node ages, due to errors in taxonomic affiliation and/or specified geological ages. The affiliation error is often due to misleading morphological similarities between unrelated extant organisms and (ambiguous) microfossils. Moreover, polyphyletic groups make impossible to specify node calibrations, except by reporting their origin to a (much) older common ancestor far back in the tree. This problem could be even worse if some scarcely sampled extant organisms used for calibration are actually polyphyletic. Regarding ages, they are specified as prior distributions partly based on the minimum age (lower bound or oldest occurrence) of a given microfossil in the paleontological record. However, owing to issues due to taphonomy and extinction of stem groups, this may introduce an unmeasurable divergence between the ages specified for the fossil and the real geological span of the organism. Ultimately, inferred node ages are thus highly dependent on the completeness of the paleontological record [221].

Because of these limitations, an alternative strategy, termed tip-dating, would be more suitable for dating the evolution of Cyanobacteria. In such an approach, the placement of the microfossils within the tree is guided by a morphological matrix and supported by statistical values, the posterior probabilities [222]. The consequence of this “automatic” placement is that tip-dating enables the use of a wider range of microfossils, not only the unambiguous ones, but also the numerous ambiguous microfossils. Further, by explicitly modeling stem groups within the tree [221], tip-dating is able to test (and thus either confirm or reject) the affiliation of microfossils to extant organisms, which is usually taken for granted in the paleontological literature and many molecular dating studies building upon it.

4.2. Origin of cyanobacteria and oxygenic photosynthesis

In most cyanobacterial phylogenetic analyses that are using a non-cyanobacterial outgroup to root the tree, the reference strain Gloeobacter violaceus PCC7421 has a basal position [9,[223], [224], [225]]. Consequently, the phylogenetic node bearing Gloeobacter and the rest of modern cyanobacterial lineages serves as calibration for the origin of cyanobacteria in several studies [[226], [227], [228]]. In these studies, the authors have set different root limit ages, so that the maximum root age may vary between the earliest estimate of abiogenesis around 4.2 Ga [226], the end of the Late Heavy Bombardment at 3.85 Ga [228], or the GOE at 2.4 Ga [229].

Recently, two newly discovered lineages were proposed as sister groups of the cyanobacterial phylum, the Melainabacteria [230] and the Sericytochromatia [231]. Of note, these lineages (mostly known as metagenomics assemblies) do not contain genes required for photosynthesis nor carbon fixation [231]. The integration of genetic data from Melainabacteria and Sericytochromatia as outgroups for molecular clock analyses suggested that cyanobacteria evolved just before the GOE [213,219]. Taken together, this suggests that oxygenic photosynthesis has evolved after the separation of cyanobacteria from Melainabacteria [213,219]. However, the loss of photosynthetic capability in the ancestor of the three lineages before or at the time of GOE has been suggested as an alternative hypothesis that cannot be ruled out [232].

Among bacterial phototrophs (cyanobacteria, green S-bacteria, green non sulfur bacteria, purple bacteria, heliobacteria, some acidobacteria and gemmatimonadetes), Cyanobacteria is the only lineage that possesses two photosynthetic reaction centers of the Fe–S type (RCI) and Quinone type (RCII), whereas anoxygenic bacteria possess either the Fe–S or Quinone type. So far, three hypotheses were proposed to explain the presence of both types of RC in modern cyanobacteria. Two of these hypotheses suggest that both RCs would have been present in an anoxygenic phototrophic ancestor. In a first hypothesis, RCs evolved within the common ancestor of (all) bacterial phototrophs. Both of them were kept in the cyanobacterial lineage whereas there was a selective loss of one type of each in the modern anoxygenic lineage ancestors [233,234]. In the second hypothesis, the RCI and RCII would have emerged in the protocyanobacterial ancestor by duplication of a unique ancestral RC. This was followed by lateral transfer of a different RC type to the ancestors of the modern anoxygenic phototrophs [235]. The existence of an anoxygenic cyanobacterial ancestor may be supported by the occurrence of several genes involved in anoxygenic photosynthesis in modern cyanobacterial genomes [236], and the co-occurrence of both anoxygenic and oxygenic photosynthesis in several lineages of modern cyanobacteria clades [237,238]. A third hypothesis rather suggests the independent evolution of the two RCs in separate lineages of anoxygenic phototrophs and their lateral transfer into a protocyanobacterial ancestor, the so-called fusion hypothesis [239,240]. At least in purple bacteria, the genes for RCII are clustered in an ensemble of operons, the photosynthesis gene cluster (PGC), some organisms even harboring the PGC on large plasmids. This observation makes the transfer of full photosystems highly plausible, and recent events of such kind have been convincingly inferred in Rhodobacteraceae [241].

In order to test the likelihood of the ancient transfer of photosystems between the bacterial phototrophic lineages, Magnabosco and colleagues [213] added horizontal gene transfer events information of two genes (encoding for Mg-chelatase and S-adenosyl-l-homocysteine hydrolase) as additional constraints to their models to estimate the stem age of the bacterial phototrophs (Cyanobacteria, green S-bacteria and green non-sulfur bacteria). These authors assumed that such estimates would allow them to investigate the feasibility and timing of the RC transfer events between phototrophic lineages. Their results excluded the possibility of a RC transfer from the green sulfur bacteria to cyanobacteria, and thus, invalidated the fusion hypothesis. However, they were not able to choose between the two hypotheses suggesting that both RCs emerged from a common ancestor [213].

First, the reaction centers RCI and RCII would operate separately and asynchronously in the same ancestral anoxygenic phototroph organism. The RCI would catalyze H2S oxidation as in green S-bacteria, while the RCII would act as a light-dependent electron transporter as in purple bacteria [242]. A water-splitting RCII could also have evolved from an ancestral RCII type already capable of photosynthesis and manganese oxidation [243]. However, the evolution of these processes, and the early or late evolution of oxygenic photosynthesis, are still debated e.g. Refs. [99,244].

4.3. Diversification

Several studies suggested that ancestral cyanobacteria first inhabited freshwater ecosystems [13,15,17,210,218,226], but see e.g. Ref. [16] for a marine origin. Nevertheless, these estimates are based on comparison with the modern ecology of basal clades of cyanobacteria, which are likely to have changed through time. Moreover, the fossil record of cyanobacteria is almost exclusively estuarine and shallow marine, often from the intertidal zone, or hypersaline lacustrine. However, terrestrial deposits are less commonly preserved in the geological record, and this might bias our view of the fossil ecological ranges.

A couple time calibrated phylogenies based on low-resolution alignments of 16S rRNA gene sequences or on a large multilocus dataset [227,228] suggest that multicellular forms of cyanobacteria were potentially present when the GOE started, implying a pre-GOE origin of the cyanobacterial phylum. Furthermore, their results hint at an acceleration of the diversification rate after the substantial increase of atmospheric oxygen concentration [227]. The acquisition of the multicellularity would be an advantage for UV resistance and substrate adhesion [40]. However, multicellularity is polyphyletic and convergent several times across extant species – especially in cyanobacteria.

Other studies hypothesize that the origin of marine planktonic cyanobacteria would have happened after the evolution of crown groups in freshwater, terrestrial and benthic coastal modern environments [210]. Benthic (terrestrial and coastal) cyanobacteria may have dominated the oxygenic photosynthesis from the late Archean and possibly until the mid-Neoproterozoic [245].

However, these hypotheses remain to be confirmed since the record of Archean cyanobacteria is controversial as explained above, and the fossil record is biased towards benthic forms. Benthic filamentous cyanobacteria forming mats or preserved in silicified stromatolites are preserved preferentially to small planktonic cells sedimenting in the water column. Moreover shallow-water deposits are more common in the Precambrian then deeper sediments.

Non-heterocytous N-fixing unicellular and filamentous Trichodesmium spp. would have appeared later, during the late Neoproterozoic [210,218]. This observation possibly coincides with an increase of bioavailable Mo (an essential co-factor of nitrogenase) in the open ocean [40,218,246,247]. However, cyanobacteria likely had to invent a new N2-fixation machinery that could operate in the presence of the rising O2, leading to the evolution of heterocytous cyanobacterial taxa, probably as early as the GOE [227], and possibly supported by Paleoproterozoic [[134], [135], [136]] and Neoproterozoic [128] microfossils. However, this hypothesis might be questioned as heterocytous cyanobacteria age estimates resulted from models that used poorly preserved putative fossil akinetes from 2.1 Ga Franceville Gabon. In the Paleoproterozoic redox stratified oceans, cyanobacteria may have performed anoxygenic (rather than oxygenic) photosynthesis using H2S above euxinic layers, or may have been outcompeted by anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria metabolizing H2S or Fe2+ above ferruginous water [248]. However, they became important primary producers in the still stratified mid-Proterozoic oceans [38].

4.4. Origin of chloroplast

Chloroplasts form a monophyletic cluster within the Cyanobacteria phylum [12]. This observation is elegantly interpreted as the result of a primary endosymbiosis at the origin of the chloroplast [249]. Although this theory is well accepted in the scientific community (but see Ref. [250] for a more complex model involving Chlamydiales), the precise position of the plastid within the extant diversity of Cyanobacteria has been a matter of discussion. Two major scenarios are opposed, one postulating an ancient origin (early-branching) [13,14,105,202,203,209,211,220] and the other one postulating a (relatively) recent (late-branching) origin [12,208,251]. The hypothesis of an early origin is more frequent in the literature, and it has recently been strengthened by the study of Ponce-Toledo et al. (2017) [13], who identified the early-branching Gloeomargarita lithophora as the closest extant relative of plastids. In an attempt to date the primary endosymbiosis, Falcón and colleagues [12] assumed that the closest relative of chloroplasts was a unicellular N-fixing cyanobacterium (late-branching hypothesis) and that it occurred during the middle of the Proterozoic [12] (Fig. 3). However the calibration used included Archean ages for the highly controversial Apex chert microstructures and sterane that were subsequently reassessed as contaminants (see above). Later studies of ATP synthases subunits and elongation factors permitted to estimate the first endosymbiosis event at approximately 0.9 Ga [220]. Taking advantage of the recent discovery of Gloeomargarita [13,252], Sanchez-Baraccaldo et al. (2017) estimated the age of the origin of the chloroplast at 1.9 Ga (2.12–1.75 Ga) [15]. This result is similar to the one reported in Ref. [14], although the topologies used in the two studies were slightly different with respect to plastid position. In contrast, Shih et al., 2017 [219] recovered a quite different age for plastids (1.1 Ga). Interestingly, this latter estimate is more similar to the result of [12], even if assuming an early-branching hypothesis for plastid emergence. This suggests that discrepancies in estimated chloroplast ages rather stem from differences in calibration points and/or dating models than from topologies (early vs late-branching hypotheses). Indeed, if differences do exist in tree topologies concerning chloroplast emergence, the wide age intervals obtained in the various analyses often exceed the branch length variation implied by topological changes. This is not surprising given the very short length of the corresponding internodes in the cyanobacterial backbone.

As exploitable cyanobacterial microfossils are not numerous, a logical strategy is to use the morphologically more complex and more recent eukaryotic algae as calibration points. However, the oldest unambiguous fossil record of eukaryotic algae are silicified multicellular bangiophyte red algae preserved in hypersaline shallow-water environment [195] and recently well dated at 1.047 Ga [253]. These fossils were interpreted as benthic multicellular red algae based on their morphology, longitudinal division pattern, attachment structures, and ecology [195]. Other 1.6 Ga microfossils are interpreted as more divergent Florideophyte red algae based on morphology [254], but their age is debated because of the complex geology of the area [253]. Microfossils interpreted as green algae may also provide an estimation of the minimum age for chloroplast acquisition. Their fossil record ranges from unambiguous 0.6 Ga prasinophytes based on wall ultrastructure [255], 0.8 Ga probable siphonocladalean chlorophytes and probable hydrodictyacean chlorophyte based on distinctive morphology and ecology [134], the latter also found in 1.1–0.9 Ga lower Shaler Group of arctic Canada [256], to 1.65 Ga acritarchs whose putative algal interpretation needs confirmation [257]. Using the new age of 1.047 Ga calibration for Bangiomorpha, Gibson et al. [253] estimated the primary chloroplast endosymbiosis at 1.25 Ga, consistent with most of the unambiguous algal fossil record.

5. Conclusions