Significance

The philosopher John Rawls aimed to identify fair governing principles by imagining people choosing their principles from behind a “veil of ignorance,” without knowing their places in the social order. Across 7 experiments with over 6,000 participants, we show that veil-of-ignorance reasoning leads to choices that favor the greater good. Veil-of-ignorance reasoning makes people more likely to donate to a more effective charity and to favor saving more lives in a bioethical dilemma. It also addresses the social dilemma of autonomous vehicles (AVs), aligning abstract approval of utilitarian AVs (which minimize total harm) with support for a utilitarian AV policy. These studies indicate that veil-of-ignorance reasoning may be used to promote decision making that is more impartial and socially beneficial.

Keywords: ethics, decision making, policy making, procedural justice, fairness

Abstract

The “veil of ignorance” is a moral reasoning device designed to promote impartial decision making by denying decision makers access to potentially biasing information about who will benefit most or least from the available options. Veil-of-ignorance reasoning was originally applied by philosophers and economists to foundational questions concerning the overall organization of society. Here, we apply veil-of-ignorance reasoning in a more focused way to specific moral dilemmas, all of which involve a tension between the greater good and competing moral concerns. Across 7 experiments (n = 6,261), 4 preregistered, we find that veil-of-ignorance reasoning favors the greater good. Participants first engaged in veil-of-ignorance reasoning about a specific dilemma, asking themselves what they would want if they did not know who among those affected they would be. Participants then responded to a more conventional version of the same dilemma with a moral judgment, a policy preference, or an economic choice. Participants who first engaged in veil-of-ignorance reasoning subsequently made more utilitarian choices in response to a classic philosophical dilemma, a medical dilemma, a real donation decision between a more vs. less effective charity, and a policy decision concerning the social dilemma of autonomous vehicles. These effects depend on the impartial thinking induced by veil-of-ignorance reasoning and cannot be explained by anchoring, probabilistic reasoning, or generic perspective taking. These studies indicate that veil-of-ignorance reasoning may be a useful tool for decision makers who wish to make more impartial and/or socially beneficial choices.

The philosopher John Rawls (1) proposed a famous thought experiment, aimed at identifying the governing principles of a just society. Rawls imagined decision makers who have been denied all knowledge of their personal circumstances. They do not know whether they, as individuals, are rich or poor, healthy or ill, or in possession of special talents or abilities. Nor do they know the social groups to which they belong, as defined by race, class, gender, etc. The decision makers are assumed to be purely self-interested, but their decisions are constrained by the absence of information that they could use to select principles favorable to their personal circumstances. Rawls referred to this epistemically restricted state as being behind a “veil of ignorance” (VOI).

Rawls conceived of this hypothetical decision as a device for helping people in the real world think more clearly and impartially about the organizing principles of society. A just social order, he argued, is one that selfish people would choose if they were constrained to choose impartially, in the absence of potentially biasing information. Some empirical researchers have adapted Rawls’ thought experiment to the laboratory, asking ordinary people to evaluate candidate organizing principles by engaging in VOI reasoning (2). Here, we depart from the conventional use of the VOI as a device for thinking about the general organization of society. Instead, we apply VOI reasoning to a set of more specific moral and social dilemmas. These dilemmas, although more restricted in scope than Rawls’ foundational dilemma, are nevertheless of broad social significance, with life-and-death consequences in the domains of health care, international aid, and automated transportation. What effect, if any, does VOI reasoning have on people’s responses to such dilemmas?

We predict that VOI reasoning will cause people to make more utilitarian judgments, by which we mean judgments that maximize collective welfare.* This result is by no means guaranteed, as there are reasons to think that VOI reasoning could have the opposite effect, or no effect at all. Rawls was one of utilitarianism’s leading critics (1), suggesting that VOI reasoning might reduce utilitarian judgment. In addition, even if VOI reasoning were to support utilitarian choices, it is possible that people’s ordinary responses to moral dilemmas implicitly reflect the lessons of VOI reasoning, such that engaging in explicit VOI reasoning would have no additional effect.

Despite Rawls’ renown as a critic of utilitarianism, our predicted results are not necessarily incompatible with Rawls’ philosophy, as the dilemmas employed here are not designed to distinguish between a utilitarian decision principle and Rawls’ “maximin” principle (1, 4). Rawls’ maximin principle favors whatever outcome maximizes the welfare of the least well-off person. For example, in the well-known footbridge case (see below), the least well-off people under each option experience equally bad outcomes, namely death by trolley. Thus, one might expect a Rawlsian to be indifferent between the 2 options or to favor the utilitarian option, invoking the utilitarian principle as a secondary consideration. (Alternatively, one might expect a Rawlsian to reject the utilitarian option on the grounds that “each person possesses an inviolability founded on justice that even the welfare of society as a whole cannot override” [ref. 1, p. 3]. See, for example, Sandel [ref. 5, Chap. 2].) Our predictions are, however, most closely aligned with the ideas of Rawls’ contemporary and critic, John Harsanyi, an influential economist who independently conceived of VOI reasoning and argued that it provides a decision-theoretic foundation for a utilitarian social philosophy (6, 7).

To illustrate our application of VOI reasoning, consider the aforementioned footbridge dilemma, in which one can save 5 people in the path of a runaway trolley by pushing a person off of a footbridge and into the trolley’s path (8). The utilitarian option is to push, as this maximizes the number of lives saved. However, relatively few people favor the utilitarian option in this case, a result of negative affective responses to this actively, directly, and intentionally harmful action (9, 10).

What effect might VOI reasoning have on a case such as this? Following Hare (11), you might imagine that you are going to be one of the 6 people affected by the footbridge decision (one of the 5 on the tracks or the one who could be pushed). You might assume that you have even odds† of being any one of them. (We note that Rawls’ version of the VOI assumes unknown odds rather than even odds.‡) Would you, from a purely self-interested perspective, want the decision maker to push, giving you a 5 out of 6 chance of living? Or would you want the decision maker to not push, giving you a 1 out of 6 chance of living? Here, we suspect (and confirm in study 1) that most people prefer that the decision-maker push, increasing one’s odds of living.

However, what, if anything, does this imply about the ethics of the original moral dilemma? As noted above, most people say that it would be wrong to push the man off the footbridge. However, a Rawlsian (or Harsanyian) argument seems to imply that pushing is the fairer and more just option: It is what those affected by the decision would want if they did not know which positions they would occupy. In the studies presented here, we follow a 2-stage procedure, as suggested by the foregoing argument. First, participants consider a VOI version of a moral dilemma, reporting on what they would want a decision maker to do if they did not know who they would be among those affected by the decision. Second, participants respond to a standard version of the same dilemma, reporting on the moral acceptability of the proposed action. (In study 3, participants in the second stage make a real-stakes choice instead of a hypothetical judgment.) The question, then, is whether engaging in VOI reasoning in the first stage influences ordinary moral judgment in the second stage. To be clear, we are not comparing the responses in the VOI exercise with responses to the standard moral dilemma. Instead, we investigate the influence of VOI reasoning, induced through the VOI exercise, on responses to the standard moral dilemma.

In applying VOI reasoning, we are not only attempting to influence moral judgment, but to do so through a kind of reasoning. By this, we mean that the influence occurs through a conscious valuation process that is constrained by a need for consistency—either with a general principle, with related judgments, or both (14). We expect that, in the second stage, participants will explicitly consider the normative relationship between the moral judgment they are currently making and the judgment that they made in the first stage, a self-interested decision from behind a VOI. Moreover, we expect that they will be inclined to make their current moral judgment consistent with their prior VOI judgment. In other words, we predict that participants will think something like this: “If I didn’t know which of the 6 people I was going to be, I would want the decision maker to push. But when I think about pushing, it feels wrong. Nevertheless, if pushing is what I’d want from an impartial perspective, not knowing who I was going to be, then perhaps it really is the right thing to do, even if it feels wrong.”

Thus, through this procedure, we encourage participants to absorb the philosophical insight of the VOI thought experiment and apply this idea in their subsequent judgments. We note that the predicted effect of VOI reasoning would provide evidence for an especially complex form of moral reasoning. This would be notable, in part, because there is little evidence for moral reasoning beyond the application of simple rules such as simple cost–benefit reasoning (3, 13, 15–18).

Beyond moral psychology, the effects of VOI reasoning may be of practical significance, as people’s responses to moral dilemmas are often conflicted and carry significant social costs (13). Consider, for example, the social dilemma of autonomous vehicles (AVs) (19), featuring a trade-off between the safety of AV passengers and that of others, such as pedestrians. As a Mercedes-Benz executive discovered (20), an AV that prioritizes the safety of its passengers will be criticized for devaluing the lives of others. However, a “utilitarian” AV that values all lives equally will be criticized for its willingness to sacrifice its passengers. This paradox is reflected in the judgments of ordinary people, who tend to approve of utilitarian AVs in principle, but disapprove of enforcing utilitarian regulations for AVs (19). Likewise, people may feel conflicted about bioethical policies or charities that maximize good outcomes, with costs to specific, identifiable parties (13). We ask whether the impartial perspective encouraged by VOI reasoning can influence people’s responses to these and other dilemmas. This research does not assume that such an influence would be desirable. However, to the extent that people value impartial decision procedures or collective well-being, such an influence would be significant.

Across 7 studies, we investigate the influence of VOI reasoning on moral judgment. We begin with the footbridge dilemma (study 1) because it is familiar and well characterized. In subsequent studies, we employ cases with more direct application, including a decision with real financial stakes (study 3). Across all cases, we predict that participants’ responses to the VOI versions will tend to be utilitarian, simply because this maximizes their odds of a good outcome. Critically, we expect participants to align their later moral judgments with their prior VOI preferences, causing them to make more utilitarian moral judgments, favoring the greater good, compared to control participants who have not engaged in VOI reasoning.

Experimental Designs and Results

Study 1 (n = 264) employs the footbridge dilemma: The decision maker can save 5 people in the path of a runaway trolley by pushing a person off of a footbridge and into the trolley’s path (8). The utilitarian option is to push, as this saves more lives, but relatively few favor this option, largely due to negative affective responses (9, 10). Study 1’s VOI condition employs the 2-stage procedure described above. In the VOI version (stage 1), participants imagined having equal odds of being each of the 6 people affected by the decision: the 5 people on the tracks and the sixth person who could be pushed. Participants were asked whether they would want the decision maker to push, giving the participant a 5 out of 6 chance of living, or not push, giving the participant a 1 out of 6 chance of living. Here (and in all subsequent studies), most participants gave utilitarian responses to the VOI version of the dilemma. In stage 2 of the VOI condition, participants responded to the standard footbridge dilemma as the decision maker, evaluating the moral acceptability of pushing, using a dichotomous response and a scale rating. In the control condition, there is only one stage, wherein participants respond to the standard dilemma. Critically, the key dependent measures for both conditions were responses to the standard dilemma. In other words, we ask whether first completing the VOI version affects subsequent responses to the standard dilemma.

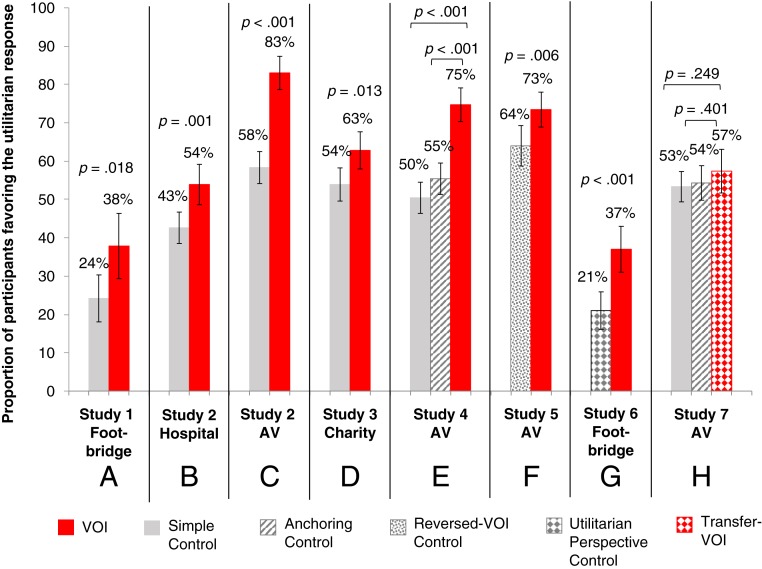

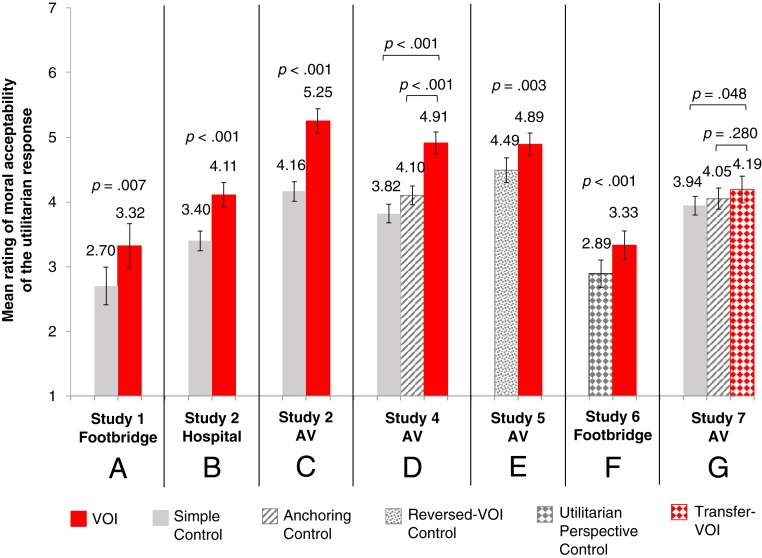

As predicted, participants in the VOI condition gave more utilitarian responses to the standard footbridge dilemma (38% [95% CI: 30%, 47%]), compared to control participants (24% [95% CI: 18%, 32%]; logistic regression, P = 0.018). Likewise, participants rated the utilitarian response as more morally acceptable in the VOI condition (mean [M] = 3.32, SD = 2.05) compared to the control condition (M = 2.70, SD = 1.65) [linear regression, t(262) = 2.74, P = 0.007] (Figs. 1A and 2A). (See SI Appendix for detailed procedures, materials, and results for all studies, including results without excluding participants who failed attention and/or comprehension checks. See SI Appendix, Tables S1–S4. See studies 4 to 6 for additional control conditions.)

Fig. 1.

Dichotomous responses for all studies (n = 6,261). P values from logistic regression. Error bars indicate 95% CI. (A) Study 1 footbridge case; (B) study 2 hospital case; (C) study 2 AV case; (D) study 3 charity case; (E) study 4 AV case; (F) study 5 AV case; (G) study 6 footbridge case; and (H) study 7 AV case.

Fig. 2.

Scale responses for studies 1, 2, and 4 to 7 (n = 5,428). P values from linear regression. Error bars indicate 95% CI. (A) Study 1 footbridge case; (B) study 2 hospital case; (C) study 2 AV case; (D) study 4 AV case; (E) study 5 AV case; (F) study 6 footbridge case; and (G) study 7 AV case.

Study 2 (n = 894) employs dilemmas concerning bioethics and the ethics of AVs. In the bioethics case, participants considered taking oxygen away from a single hospital patient to enable the surgeries of 9 incoming earthquake victims. In the VOI version of the bioethical case, participants were asked how they would want the oxygen to be allocated if they knew they had a 1 in 10 chance of being the single patient and a 9 in 10 chance of being one of the 9 earthquake victims (21). In the AV policy case, participants considered whether AVs should be required to minimize the total loss of life (i.e., be utilitarian), for example, saving 9 pedestrians by swerving into a wall, but killing the AV’s passenger (19). In the VOI AV case, participants were asked whether they would want the AV to swerve into the wall given a 1 in 10 chance of being in the AV and 9 in 10 chance of being one of the 9 pedestrians. As predicted, participants in the VOI condition gave more utilitarian responses to the standard bioethical dilemma (54% [95% CI: 49%, 59%]), compared to control (43% [95% CI: 39%, 47%]; P = 0.001). Likewise, participants in the VOI condition gave more utilitarian responses to the standard AV dilemma (83% [95% CI: 79%, 87%]), compared to control (58% [95% CI: 54%, 62%]; P < 0.001) (Fig. 1 B and C). The rating scale results showed a similar pattern: Participants in the VOI condition reported taking the patient off oxygen as more morally acceptable (M = 4.11, SD = 1.90) compared to participants in the control condition [M = 3.40, SD = 1.75; t(892) = 5.71, P < 0.001]. Similarly, participants in the VOI condition reported swerving as more morally acceptable (M = 5.25, SD = 1.74) compared to participants in the control condition [M = 4.16, SD = 1.83; t(892) = 8.86, P < 0.001] (Fig. 2 B and C).

Study 3 (n = 833) examines a real-stakes setting: charitable donations. US participants chose to donate $200 to 1 of 2 real charities (with one randomly selected participant’s decision determining the actual outcome). Donating to the more effective/utilitarian charity can be expected to cure 2 people of blindness in India. Donating to the other charity can be expected to cure one person of blindness in the United States. In the VOI condition, participants were first asked where they would want the $200 to go if they knew they had a 1 in 3 chance of being an American who would be cured by a donation to the US charity and a 2 in 3 chance of being an Indian who would be cured by a donation to the Indian charity. They then made their real donation decisions. As predicted, participants in the VOI condition more often chose to donate to the more effective/utilitarian charity (63% [95% CI: 57%, 68%]), compared to control participants, who only made the real donation decision (54% [95% CI: 50%, 58%]; P = 0.013) (Fig. 1D).

We have hypothesized that the effects observed in studies 1 to 3 are due to the influence of VOI reasoning itself, inducing a more impartial mindset that promotes concern for the greater good. An alternative explanation is that participants in the VOI condition are simply “anchoring” on their prior utilitarian responses to the VOI versions, giving subsequent utilitarian responses due to a generic tendency toward consistency. [By anchoring, we mean giving a subsequent response that is the same as a prior response, rather than referring to anchoring in the more specific sense defined by Tversky and Kahneman (22).] Our hypothesis also appeals to a desire for consistency, but we hypothesize that participants are engaging in a specific kind of moral reasoning, mirroring the reasoning of Rawls and Harsanyi, whereby participants perceive a connection between what is morally defensible and what they would want if they did not know whom they would be among those affected by the decision.

Study 4 (n = 1,574; preregistered) tests this alternative hypothesis while replicating the VOI effect using the AV dilemma. Study 4 employs an additional anchoring control condition in which participants first respond to a standard (non-VOI) dilemma that reliably elicits utilitarian responses. This non-VOI dilemma asks participants whether they favor destroying a sculpture to save the lives of 2 people. As predicted, participants in the VOI condition gave more utilitarian responses (75% [95% CI: 70%, 79%]), compared to simple control (50% [95% CI: 46%, 54%]; P < 0.001) and anchoring control (55% [95% CI: 51%, 60%]; P < 0.001). Likewise, participants rated the utilitarian policy as more morally acceptable in the VOI condition (M = 4.91, SD = 1.71), compared to those in the simple control condition [M = 3.82, SD = 1.86; t(1,571) = 9.65, P < 0.001], and compared to those in the anchoring control condition [M = 4.10, SD = 1.72; t(1,571) = 7.13, P < 0.001] (Figs. 1E and 2D).

Further alternative explanations appeal to features of the VOI dilemma not captured by study 4’s anchoring control condition. More specifically, participants in the VOI condition are asked to engage in numerical reasoning and probabilistic reasoning. This could, perhaps, induce a mindset favoring expected utility calculations, as prescribed by rational choice models of decision making (23). The VOI condition also asks participants to engage in a limited kind of perspective taking (24), as participants are asked to consider the effects of the decision on all affected. These and other task features could potentially induce more utilitarian responses to the standard dilemma. These features are essential to VOI reasoning, but a further essential feature of VOI reasoning (as implemented here) is its relation to impartiality, whereby one has an equal probability of being each person affected.

Thus, study 5 (n = 735; preregistered), which again uses the AV dilemma, employs a more stringent control condition in which participants first respond to a modified VOI dilemma in which the probabilities are reversed. That is, one has a 9 in 10 chance of being the single person in the AV and a 1 in 10 chance of being one of the 9 pedestrians in the AV’s path. Reversing the probabilities disconnects VOI reasoning from impartiality, as one no longer has an equal probability of being each person affected. Because it is the impartiality of VOI reasoning that gives it its moral force, we do not expect this reversed-VOI reasoning to have the same effect. As predicted, participants in the VOI condition gave more utilitarian responses (73% [95% CI: 69%, 78%]), compared to the reversed-VOI control condition (64% [95% CI: 59%, 69%]; P = 0.006). Likewise, participants rated the utilitarian policy as more morally acceptable in the VOI condition (M = 4.89, SD = 1.77), compared to those in the reversed-VOI control condition [M = 4.49, SD = 1.80; t(733) = 3.03, P = 0.003] (Figs. 1F and 2E).

Study 6 (n = 571; preregistered) aims to rule out a further alternative explanation for the VOI effect: The effect of VOI may simply be due to “narrow anchoring,” whereby giving a specific response to a specific dilemma in the first phase (involving the VOI exercise) then causes the participant to give the same response to the same dilemma in the second phase. We therefore employ an additional control condition in which we expect participants to give utilitarian responses to the dilemma in the first phase, but not in the second phase when they encounter the standard version of the dilemma. This additional control condition asks participants to adopt the perspective of a person (named Joe) who is strongly committed to utilitarianism and who is therefore willing to sacrifice the interests of some individuals for the greater good of others. We predicted that participants would tend to give utilitarian responses to the footbridge dilemma when asked to adopt Joe’s utilitarian perspective during the first phase of the control condition. However, we predicted that participants would tend not to give utilitarian responses in the second phase of the control condition, when they are no longer instructed to adopt Joe’s perspective and are instead simply responding to the footbridge dilemma in its standard form. We hypothesized that participants in the VOI condition, compared to those in the utilitarian-perspective control condition (in which they adopt Joe’s perspective in the first phase), would be more likely to make the utilitarian judgment in response to the standard footbridge case in the second phase.

As predicted, participants in the VOI condition gave more utilitarian responses to the standard footbridge dilemma (37% [95% CI: 31%, 43%]), compared to the utilitarian-perspective control condition (21% [95% CI: 16%, 25%]; P < 0.001). Likewise, participants rated the utilitarian judgment in the standard footbridge dilemma as more morally acceptable in the VOI condition (M = 3.33, SD = 1.86), compared to in the utilitarian-perspective control condition [M = 2.89, SD = 1.83; t(569) = 2.83, P = 0.005] (Figs. 1G and 2F). These results indicate that the effect of VOI reasoning cannot be explained by a tendency to anchor on a specific response to a specific dilemma.

Finally, study 7 (n = 1,390; preregistered) asks whether VOI reasoning transfers across cases. Participants in the transfer-VOI condition first responded to 2 VOI cases that are not tightly matched to the AV case, before responding to the standard AV case. Study 7 employed a simple control condition as in study 1 along with a 2-dilemma anchoring control condition similar to that of study 4. We predicted that participants in the transfer-VOI condition would be more likely to make the utilitarian judgment in the standard AV case, relative to the 2 control conditions. Contrary to our predictions, we found no significant differences in participants’ responses to the standard AV case in the transfer-VOI condition (57% [95% CI: 52%, 63%]), compared to simple control (53% [95% CI: 49%, 57%]; P = 0.249) and anchoring control (54% [95% CI: 50%, 59%]; P = 0.401). For the scale measure, we found that participants rated the utilitarian response as more morally acceptable in the transfer-VOI condition (M = 4.19, SD = 1.80), compared to those in the simple control condition [M = 3.94, SD = 1.86; t(1,387) = 1.98, P = 0.048]. However, there were no significant differences in participants’ scale responses between the transfer-VOI condition and the anchoring control condition [M = 4.05, SD = 1.78; t(1,387) = 1.08, P = 0.280] (Figs. 1H and 2G). These results establish a boundary condition on the effect of VOI reasoning. We note, however, that further training in VOI reasoning may enable people to transcend this boundary.

Discussion

Across multiple studies, we show that VOI reasoning influences responses to moral dilemmas, encouraging responses that favor the greater good. These effects were observed in response to a classic philosophical dilemma, a bioethical dilemma, real-stakes decisions concerning charitable donations, and in judgments concerning policies for AVs. While previous research indicates net disapproval of utilitarian regulation of AVs (19), here we find that VOI reasoning shifts approval to as high as 83% (Fig. 1 C, E, and F). (We note that these findings address attitudes toward regulation, but not individual consumption.) The effect of VOI reasoning was replicated in 3 preregistered studies. These studies showed that this effect cannot be explained by a generic tendency toward consistency (general anchoring) or by a tendency to give the same response to a subsequent version of the same dilemma (narrow anchoring). Most notably, we show that the effect of VOI reasoning depends critically on assigning probabilities aligned with a principle of impartiality.

Arguably the most central debate in the field of moral psychology concerns whether and to what extent people’s judgments are shaped by intuition as opposed to reason or deliberation (13–15, 18). There is ample evidence for the influence of intuition, while evidence for effectual moral reasoning is more limited (18). Beyond simple cost–benefit utilitarian reasoning (3, 13, 15–17), people’s judgments are influenced by explicit encouragement to think rationally (25) and by simple debunking arguments (15). Performance on the Cognitive Reflection Test (26) is correlated with utilitarian judgment (15, 17, 27), and exposure to this test can boost utilitarian judgment (15, 17), but this appears to simply shift the balance between intuitive responding and utilitarian reasoning, rather than eliciting a more complex form of reasoning. Closer to the present research is the use of joint (vs. separate) evaluation, which induces participants to make a pair of judgments based on a common standard of evaluation (28).

Here, we provide evidence for effectual moral reasoning in ordinary people that is arguably more complex than any previously documented. The VOI condition requires a kind of spontaneous “micro-philosophizing” to produce its effect, recapitulating the insights of Rawls and Harsanyi, who perceived an equivalence between self-interested decisions made from behind a VOI and justifiable moral decisions. Here, participants are not presented with an explicit argument. Instead, they are given the raw materials with which to construct and apply an argument of their own making. Participants in the VOI condition are not told that there is a normative relationship between the VOI exercise and the subsequent judgment, but many participants nevertheless perceive such a relationship. Without explicit instruction, they perceive that a self-interested choice made from behind a VOI is an impartial choice, and therefore likely to be a morally good choice when the veil is absent. In addition, once again, this effect disappears when the probabilities are reversed, indicating that participants are sensitive to whether the VOI is fostering a kind of impartial thinking. We are not claiming, of course, that people engage in this kind of moral reasoning under ordinary circumstances. However, these findings indicate that ordinary people can actively engage in a rather sophisticated kind of moral reasoning with no special training and minimal prompting.

We note several limitations of the present findings. First, we do not claim that VOI reasoning must always promote utilitarian judgment. In particular, we are not attempting to resolve the debate between Rawls and Harsanyi over whether VOI reasoning favors a utilitarian principle over Rawls’ maximin principle, as the dilemmas employed here do not distinguish between them. Second, we note that our studies aimed at ruling out competing explanations (studies 4 to 6), as well as our study establishing limited generalization (study 7), all used either the footbridge case or the AV policy case. Nevertheless, the most parsimonious interpretation of the evidence is that the VOI effect observed for these cases is psychologically similar to those observed for other cases. Finally, we note that in study 5 the proportion of utilitarian judgments in the standard AV case, following the reversed-VOI exercise, was relatively high (64%), compared to the standalone AV cases tested in studies 2, 4, and 7 (58%, 50%, 53%, respectively). Thus, it is possible that component features of the VOI exercise, such as the engagement of probabilistic reasoning, may play some role in promoting subsequent utilitarian judgment. Alternatively, it could be that engaging in reversed-VOI reasoning is enough to prompt some participants to engage in standard VOI reasoning.

We emphasize that these findings, by themselves, neither assume nor demonstrate that the effects of VOI reasoning are desirable. Nevertheless, these findings may have significant implications when combined with certain widely shared moral values (29). For those who regard promoting the greater good as an important moral goal, the present findings suggest a useful tool for encouraging people to make decisions that promote the greater good. Likewise, this approach may be of interest to those who value impartial procedures, independent of any commitment to maximizing aggregate well-being. Lawmakers and policy makers who value impartial procedures and/or promoting the greater good may find VOI reasoning to be a useful tool for making complex social decisions and justifying the decisions they have made.

Here, it is worth noting connections between VOI reasoning and other policy tools. For example, others have used structured decision procedures to encourage a more impartial or detached perspective on matters of distributive justice, including one of Rawls’ and Haransyi’s central concerns, the (re)distribution of wealth (30, 31). We also note that decision procedures similar to VOI reasoning could be used for evaluating policies from a less impartial perspective. This might involve rejecting the equiprobability assumption that we (following Harsanyi) have used in our VOI reasoning procedures. For example, if one expects to have a high probability of being a passenger in an AV, but one expects to have a low probability of being a pedestrian who could be threatened by AVs, then one might want to incorporate these individualized probabilities into a decision procedure that in some ways resembles VOI reasoning. However, if the aim is to incorporate a principle of impartiality into one’s decision procedure, then, in our view, it makes the most sense to adopt Harsanyi’s equiprobability assumption.

VOI reasoning may be most useful when people are forced to make, and publicly justify, decisions involving difficult trade-offs. Decisions that promote the greater good may involve emotionally aversive sacrifices and/or an unwillingness to allocate resources based on personal or group-based loyalties (13, 32). Observers tend to be highly suspicious of people who make utilitarian decisions of this kind (33). Indeed, we found in study 6 that participants who adopted a utilitarian perspective in the first phase (because we asked them to) were not especially likely to maintain that perspective in the second phase. How, then, can decision makers whose genuine aim is to promote the greater good advance policies that are so readily perceived as antisocial or disloyal? We suggest that VOI reasoning can help people—both decision makers and observers—distinguish between policies that are truly antisocial or culpably disloyal from socially beneficial policies that are simply aversive. Emotionally uncomfortable trade-offs may seem more acceptable if one can credibly say, “This is what I would want for myself if I did not know who I was going to be.”

Where there is conflict—either within or between people—about important moral decisions, mechanisms that might promote agreement are worth considering. VOI reasoning may be especially useful because it influences people’s judgments without telling them how to think or what to value. Nor does it manipulate people through nonconscious influences or the restriction of information. Instead, it is Socratic. It openly and transparently asks people to consider their decisions from a different perspective, leaving it up to decision makers to determine whether that perspective is valuable. Across a range of decisions, from bioethics to philanthropy to machine ethics, people seem to find this perspective illuminating.

Materials and Methods

The procedures and materials for all studies were reviewed and approved by the Harvard University Institutional Review Board. All participants provided informed consent. We have uploaded all study materials, preregistrations, raw data, and analyses code on Open Science Framework (34). All statistical analyses were conducted using R statistical software. For complete study materials, see SI Appendix.

Study 1.

In both conditions, participants entered their Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) IDs and completed an attention check. Participants who failed the attention check were excluded from analysis. In the control condition, participants responded to the standard version of the footbridge dilemma with a dichotomous choice (“Is it morally acceptable for you to push the second person on to the tracks in order to save the five workmen?”) and a scale item (“To what extent is this action morally acceptable?”).

In the VOI condition, participants first responded to a VOI version of the footbridge dilemma in which the participant is asked to imagine having an equal probability of being each of the 6 people affected by the decision. They then indicated what they would like the decision maker to do using a dichotomous choice (“Do you want the decision maker to push or not push?”) and a scale measure (“To what extent do you want the decision maker to push?”). The VOI version of the footbridge dilemma was then followed by the standard version, as used in the control condition. Once again, in both conditions our primary dependent measures are responses to the standard footbridge dilemma.

In both conditions, after participants responded to the dilemma(s), they completed comprehension checks (one for each dilemma). We hypothesized a priori that only participants who engaged in careful and attentive thinking would be affected by the VOI manipulation, and therefore we excluded from analysis participants who failed at least one attention check or comprehension check. For all studies, we report exclusion rates by condition, and we present results including all participants. This provides assurance that our conclusions are not artifacts of differential rates of exclusion across conditions (SI Appendix, Tables S1–S4).

At the end of their sessions, participants in the VOI condition were asked about whether their responses to the standard case were influenced by the VOI exercise. All participants assessed their prior familiarity with the testing materials, supplied their age and gender, and were asked for general comments.

Study 2.

Procedures followed those of study 1, but using the hospital and AV dilemmas. Participants were assigned to the same condition for both dilemmas, and all participants responded to both the hospital and AV dilemmas. In the VOI condition, participants were always presented with the VOI version of a dilemma immediately prior to the standard version of that dilemma. In both conditions, and in both stages of the VOI condition, the order of the dilemmas (AV vs. hospital) was counterbalanced.

In the standard AV case, participants responded to the dichotomous measure (“Is it morally acceptable for a state law to require autonomous vehicles to swerve in such a situation to save the 9 pedestrians?”) followed by the corresponding scale measure. In the standard hospital case, participants responded to the dichotomous measure (“Is it morally acceptable for you to take the patient at the hospital off oxygen?”) followed by the scale measure.

In the VOI version of the AV dilemma, participants responded to a dichotomous measure (“Please respond from a purely self-interested perspective: Would you want to be in a state where the law requires autonomous vehicles to swerve in such a situation?”) and a corresponding scale measure. Likewise, in the VOI hospital dilemma, participants responded to a dichotomous measure (“Please respond from a purely self-interested perspective: Do you want the ethics committee to take the patient off oxygen?”) and a corresponding scale measure. In study 1, we expected participants responding to the VOI dilemma to respond from a self-interested perspective when asked what they would want the decision maker to do, as the decision maker’s choice would determine whether they would probably live or probably die. In study 2 and all subsequent studies, we explicitly instructed participants responding to VOI dilemmas to respond from a self-interested perspective. This change only affects the VOI exercise and not the standard moral dilemma used in the second phase of the VOI condition.

Study 3.

Here, participants chose between a more effective and less effective charitable donation. We presented all participants with descriptions of 2 real charities, although the charity names were not given. Donating $200 to the Indian charity would fund cataract surgeries for 2 people in India. Each of the 2 people need surgery in one eye, and without the surgery, each will go permanently blind in one eye. Donating $200 to the US charity would contribute to funding surgery for a person living in the United States. Here, the recipient is going blind from an eye disease called pars planitis, and without the surgery, this person will go permanently blind in one eye. These charities were designated “charity A” and “charity B,” with label/order counterbalanced.

The Indian charity is more effective because the same level of donation cures 2 people instead of 1. More precisely, a donation to the US charity is expected to contribute to the curing of a single person. However, for the purposes of assigning probabilities in the VOI version, we assumed that the single person would be cured as a result of the donation. This is a conservative assumption, since it increases the appeal of the US charity, and our prediction is that considering the VOI version of the charity dilemma will make people less likely to choose the US charity in the subsequent decision. The 2 charities differ in other ways, most notably in the nationality of beneficiaries, but that is by design, as the most effective charities tend to benefit people in poorer nations, where funds go further.

For the real donation decision employed in both conditions, we told participants, “We will actually make a $200 donation and one randomly chosen participant’s decision will determine where the $200 goes.” They were then asked, “To which charity do you want to donate the $200?” with the options, “I want to donate the $200 to charity A” or “I want to donate the $200 to charity B.”

In the VOI condition, participants were first presented with a VOI version of the charity dilemma (hypothetical), which used this prompt: “Please respond from a purely self-interested perspective: To which charity do you want the decision maker to donate the $200?” There was no continuous measure in study 3. Participants in the VOI condition then made their real charity decision, as in the control condition. We compared the real charity decisions between the VOI and control conditions.

Study 4.

Study 4 methods (preregistered; #6425 on AsPredicted.org) follow those used for the AV policy case in study 2, but with no accompanying bioethical dilemma, and, critically, with the inclusion of a new anchoring control condition. In the anchoring control condition, participants first responded to the sculpture case (which reliably elicits utilitarian responses) before responding to the AV policy case.

Study 5.

Study 5 methods (preregistered; #11473 on AsPredicted.org) follow that of studies 2 and 4, using variants of the AV policy dilemma for both the VOI condition and the reversed-VOI control condition. As before, in the VOI condition, participants completed a VOI version of the AV dilemma, in which they imagined having a 9 in 10 chance of being one of the 9 people in the path of the AV and a 1 in 10 chance of being the single passenger in the AV. In the reversed-VOI version of the AV dilemma, they imagined having a 9 in 10 chance of being the single passenger in the AV and a 1 in 10 chance of being one of the 9 pedestrians in the AV’s path.

Study 6.

In study 6 (preregistered; #27268 on AsPredicted.org), participants responded to the standard footbridge case, as in study 1, as the main dependent variable. In the VOI condition, participants first responded to the VOI version of the footbridge case, prior to the standard footbridge case, as in study 1. In the utilitarian-perspective control condition, participants responded to a version of the footbridge case in which they were instructed to adopt the perspective of a person committed to utilitarianism. This was then followed by the standard footbridge case, as in the VOI condition.

Study 7.

In study 7 (preregistered; #6157 on AsPredicted.org), as in studies 4 and 5, all participants responded to the standard AV case. This study tested for a transfer effect. In the transfer-VOI condition, participants completed the VOI hospital case and a hypothetical version of the VOI charity case (from studies 2 and 3, respectively) before responding to the standard AV case. We intentionally included 2 VOI cases for the VOI manipulation, before the standard AV case, to boost the possibility of transfer. In the simple control condition, participants responded only to the standard AV case. In the anchoring control condition, prior to the standard AV case, participants responded to the sculpture case from study 4 and an additional case, the speedboat case, which also reliably elicits utilitarian judgments. Thus, as in study 4, this control condition is intended to control for participants’ making 2 affirmative utilitarian responses prior to responding to the standard AV case. We note that this control condition lacks the features introduced in study 5 (which was run after study 7). However, because our prediction concerning this control condition was not confirmed, the absence of these features does not affect our conclusions. In both the transfer-VOI condition and the anchoring control conditions, we counterbalanced the order of the 2 cases preceding the standard AV case.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Thanks to F. Cushman, D. Gilbert, A. W. Brooks, N. Barak-Corren, I. Gabriel, and members of the Cushman laboratory and the J.D.G. laboratory for comments; and S. Worthington for statistical support. This research was supported by the Future of Life Institute (2015-146757) and the Harvard Business School.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: All study materials, preregistrations, raw data, and analyses code reported in this paper have been deposited on Open Science Framework, https://osf.io/6xyct/?view_only=7bf03da0dbe049b8bbbda05d4c139d02.

*Following convention in the psychology and cognitive neuroscience literatures, we refer to these judgments as “utilitarian,” but one could also call them “consequentialist,” a label that does not assume that saving more lives necessarily implies greater overall happiness. In addition, in calling these judgments utilitarian, we are not claiming that the people who make them are in any general way committed to utilitarianism (3).

†Our understanding of “even odds” is motivated by a principle of impartiality, which provides the motivation for VOI reasoning. VOI reasoning, as applied here, assigns even odds of being each person affected by the specific decision in question. One could, however, incorporate other types of probabilistic information, such as the odds that a decision-maker would, in real life, occupy one position rather than another (e.g., being on a footbridge vs. on trolley tracks). Incorporating such probabilities could be highly relevant for other purposes, but doing so would weaken the connection between VOI reasoning and impartiality, which is essential for present purposes. See Discussion.

‡In Rawls’ version of the VOI, the decision makers assume that their odds of occupying any particular position in society are unknown. Following Harsanyi, we make an “equiprobability” assumption, instructing participants that they have even odds of being each of the people affected by the decision. In other words, we make the decision a matter of “risk,” rather than “ambiguity” (12). We do this for 2 related reasons. First, it is not our purpose to examine the effect of Rawls’ specific version of VOI reasoning, but rather to determine whether some kind of VOI reasoning, embodying a principle of impartiality, can influence moral judgment and, more specifically, induce people to make choices that more reliably favor the greater good. Second, and more positively, we believe that Rawls’ assumption of unknown odds, rather than even odds, makes little sense given the rationale behind the VOI thought experiment: If the function of the veil is to constrain the decision-makers into perfect impartiality, then why not give the interests of each person exactly equal weight by giving the decision-makers exactly even odds of being each person? We know of no compelling justification for assuming that the odds are anything other than exactly equal. (See ref. 13, pp. 383–385.)

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1910125116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Rawls J., A Theory of Justice (Harvard, 1971). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frohlich N., Oppenheimer J. A., Eavey C. L., Laboratory results on Rawls’s distributive justice. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 17, 1–21 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conway P., Goldstein-Greenwood J., Polacek D., Greene J. D., Sacrificial utilitarian judgments do reflect concern for the greater good: Clarification via process dissociation and the judgments of philosophers. Cognition 179, 241–265 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kameda T., et al. , Rawlsian maximin rule operates as a common cognitive anchor in distributive justice and risky decisions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 11817–11822 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sandel M. J., Justice: What’s the Right Thing To Do? (Macmillan, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harsanyi J. C., Cardinal welfare, individualistic ethics, and interpersonal comparisons of utility. J. Polit. Econ. 63, 309–321 (1955). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harsanyi J. C., Can the maximin principle serve as a basis for morality? A critique of John Rawls’s theory. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 69, 594–606 (1975). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomson J. J., The trolley problem. Yale Law J. 94, 1395–1415 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greene J. D., Sommerville R. B., Nystrom L. E., Darley J. M., Cohen J. D., An fMRI investigation of emotional engagement in moral judgment. Science 293, 2105–2108 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koenigs M., et al. , Damage to the prefrontal cortex increases utilitarian moral judgements. Nature 446, 908–911 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hare C., Should we wish well to all? Philos. Rev. 125, 451–472 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knight F. H., Risk, Uncertainty and Profit (Hart, Schaffner and Marx, 1921). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greene J. D., Moral Tribes: Emotion, Reason, and the Gap between Us and Them (Penguin, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paxton J. M., Greene J. D., Moral reasoning: Hints and allegations. Top. Cogn. Sci. 2, 511–527 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paxton J. M., Ungar L., Greene J. D., Reflection and reasoning in moral judgment. Cogn. Sci. 36, 163–177 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crockett M. J., Models of morality. Trends Cogn. Sci. 17, 363–366 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patil I., et al. , Reasoning supports utilitarian resolutions to moral dilemmas across diverse measures. bioRxiv:10.31234/osf.io/q86vx (22 December 2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Haidt J., The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion (Vintage, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonnefon J. F., Shariff A., Rahwan I., The social dilemma of autonomous vehicles. Science 352, 1573–1576 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morris D. Z., Mercedes-Benz’s self-driving cars would choose passenger lives over bystanders Fortune, 15 October 2016. https://fortune.com/2016/10/15/mercedes-self-driving-car-ethics/. Accessed 20 October 2018.

- 21.Robichaud C., Liberty Hospital Simulation. Classroom exercise (2015). https://www.openpediatrics.org/sites/default/files/assets/files/facilitator_guide_part_2_-_liberty_hospital_simulation_exercise_scenarios_year_2_lesson_5.docx. Accessed 12 January 2017.

- 22.Tversky A., Kahneman D., Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science 185, 1124–1131 (1974). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Von Neumann J., Morgenstern O., Theory of Games and Economic Behavior (Commemorative Edition, Princeton, 2007). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galinsky A. D., Moskowitz G. B., Perspective-taking: Decreasing stereotype expression, stereotype accessibility, and in-group favoritism. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 78, 708–724 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pizarro D. A., Uhlmann E., Bloom P., Causal deviance and the attribution of moral responsibility. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 39, 653–660 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frederick S., Cognitive reflection and decision making. J. Econ. Pers. 19, 25–42 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paxton J. M., Bruni T., Greene J. D., Are “counter-intuitive” deontological judgments really counter-intuitive? An empirical reply to. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 9, 1368–1371 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bazerman M. H., Loewenstein G. F., White S. B., Reversals of preference in allocation decisions: Judging an alternative versus choosing among alternatives. Adm. Sci. Q. 37, 220–240 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greene J. D., Beyond point-and-shoot morality: Why cognitive (neuro)science matters for ethics. Ethics 124, 695–726 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Norton M. I., Ariely D., Building a better America—one wealth quintile at a time. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 6, 9–12 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hauser O. P., Norton M. I., (Mis)perceptions of inequality. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 18, 21–25 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bloom P., Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion (Ecco, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Everett J. A. C., Faber N. S., Savulescu J., Crockett M. J., The costs of being consequentialist: Social inference from instrumental harm and impartial beneficence. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 79, 200–216 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang K., Greene J. D., Bazerman M., Veil-of-ignorance reasoning favors the greater good. Study materials, preregistrations, data, and code. https://osf.io/6xyct/?view_only=7bf03da0dbe049b8bbbda05d4c139d02. Deposited 10 October 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.