Abstract

Purpose:

Aging is a known risk factor for osteoarthritis (OA). Several transgenic rodent models have been used to investigate the effects of accelerated or delayed aging in articular joints. However, age-effects on the progression of post-traumatic OA are less frequently evaluated. The objective of this study is to evaluate how animal age affects the severity of intra-articular inflammation and joint damage in the rat medial collateral ligament plus medial meniscus transection (MCLT+MMT) model of knee OA.

Methods:

Forty-eight, male Lewis rats were aged to 3, 6, or 9 months old. At each age, eight rats received either an MCLT+MMT surgery or a skin-incision. At 2 months post-surgery, intra-articular evidence of CTXII, IL1β, IL6, TNFα, and IFNγ was evaluated using a multiplex magnetic capture technique, and histological evidence of OA was assessed via a quantitative histological scoring technique.

Results:

Elevated levels of CTXII and IL6 were found in MCLT+MMT knees relative to skin-incision and contralateral controls; however, animal age did not affect the severity of joint inflammation. Conversely, histological investigation of cartilage damage showed larger cartilage lesion areas, greater width of affected cartilage, and more evidence of hypertrophic cartilage damage in MCLT+MMT knees with age.

Conclusions:

These data indicate the severity of cartilage damage subsequent to MCLT+MMT surgery is related to the rat’s age at the time of injury. However, despite greater levels of cartilage damage, the level of intra-articular inflammation was not necessarily affected in 3, 6, and 9 month old male rats.

Keywords: knee osteoarthritis, age, meniscus injury, intra-articular inflammation, quantitative histology, cartilage lesion morphometry

Introduction

In osteoarthritis (OA), homeostasis within the articular joint is permanently disrupted, creating a chronic cycle of maladaptive joint remodeling and low-grade inflammation1. Here, cartilage begins to break down and fracture – a hallmark of OA pathogenesis. In response to altered distribution of joint loads, bony structures remodel, as evident by subchondral bone thickening and osteophyte formation along the joint margins. Fibrocartilaginous tissues, like the knee menisci, begin to thin and may experience degenerative tears. Alterations in joint loading can also cause structural changes in ligaments, which alter joint laxity and further promote joint damage. Moreover, changes in joint biomechanics, fragmentation of joint tissues, and danger signals from cells within the articular joint can incite synovial inflammation2. This maladaptive remodeling of multiple joint tissues can lead to the recruitment of immune cells, mainly macrophages, and increased intra-articular inflammation throughout the joint3. The chronic low-grade inflammation in the OA joint can drive both structural changes and painful symptoms4–6. Increases in catabolic enzyme activity and pro-inflammatory mediators contribute to the maladaptive changes in the OA joint and perpetuate a long-term cycle of pro-inflammatory activity that fails to resolve. Typically, the root cause of OA is unknown, as OA may arise from multiple sources, including inflammatory, genetic, biomechanical, and metabolic factors. However, regardless of the underlying cause, the OA joint is irreversibly damaged, and the OA patient may develop chronic pain and disability.

Aging is a known risk factor for OA development7, and aging processes, both within the joint and in related physiologic systems, can contribute to the initiation and progression of OA8–10. In particular, aging contributes to both systemic and local inflammatory changes3; 10–12. With age, stressors on the immune system culminate in an immunosenescent state of dysregulated immune function, resulting in altered levels of several pro-inflammatory mediators with increasing age. Fat mass also increases with age, and increases in fat mass are associated with an influx of pro-inflammatory mediators. Within the OA joint, chondrocytes show evidence of senescence and DNA damage. Senescent cells exhibit a senescent-associated secretory phenotype, which is characterized by the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, and enzymes. This senescent-associated secretory phenotype is linked with aging and may promote OA by increasing intra-articular levels of pro-inflammatory mediators.

While age is a primary risk factor for OA development, the majority of OA models study OA in young, near-adolescent rodents13. Of the work that has examined age effects in rodent OA models, transgenic mouse studies are the most common. This includes work where age-associated OA is slowed. For example, in the lectin-like, ox-LDL receptor-1 (LOX-1) knockout mouse, resistance is shown to age-related OA at both 12 and 18 months, measured via joint histology14. Transgenic mice have also been used to study accelerated aging, where mice with inactivation of integrin α1 or modifications to key cartilage structural proteins have accelerated histological evidence of OA15; 16. Comparisons have also been drawn between spontaneous, age-related OA models and chemically- or surgically-induced OA models. For example, while the Hartley guinea pig is a common model of age-related OA17; 18, a surgically-simulated ACL injury in 12 month old, male Hartley guinea pig accelerates joint damage in conjunction with increased MMP13, IL1β, and collagen fragmentation19. In addition, 18 month old, male IL6 knockout mice developed spontaneous age-related OA relative to wild-type controls20. However, when collagenase was injected to induce OA in 3 month old, male IL6 knockout mice and wildtypes, comparable levels of joint damage were observed. In a related study, 12 and 22 month old macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) knockout mice were protected against age-related OA21; however, at 12 weeks old, both MIF knockout mice and wild-type controls developed similar levels of joint damage following destabilization of the medial meniscus (DMM).

Unfortunately, while age-associated OA and experimentally-induced OA models are often compared, the effects of age on OA progression within a chemically- or surgically-induced OA is less frequently studied. Blaker and colleagues22 explored age effects in a mouse model of joint loading and ACL rupture, demonstrating adolescent, adult, and older adult mice all showed different mechanisms of ACL injury. Moreover, Huang et al23 showed the severity of cartilage degradation and subchondral bone thickening following DMM surgery was worse in 12-month old mice relative to 4-month animals. Related to this study, a simulated ACL injury in 12-month old rats showed significantly worse cartilage degradation compared to the same injury in 2-month old rats24. Interestingly, the ACL injury enhanced local levels of IL17 and IL1β, but the inflammatory response was not affected by age despite the increased joint damage24. These studies serve to highlight the differences in etiological factors in OA research, as age can both serve as an underlying cause of OA and as a factor that affects OA progression.

The objective of our study is to evaluate how animal age affects the severity of intra-articular inflammation and joint damage in a medial collateral ligament plus medial meniscus transection (MCLT+MMT) rat model of post-traumatic OA. To achieve this objective, a meniscal injury was surgically simulated in 3, 6, and 9 month old male Lewis rats. Our study adds to the limited body of work on age-effects in surgically-induced models of knee OA, filling the gap of age-effects in the rat MCLT+MMT model.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

To achieve our objective, two sequential sets of experiments were performed. First, our group’s magnetic capture protocols26; 27 for the evaluation of intra-articular OA biomarkers were adapted to simultaneously measure one marker of cartilage catabolism and four markers of intra-articular inflammation. Since this is the first application of multiplex magnetic capture, our first set of experiments validates this approach in vitro. Next, both the multiplex magnetic capture protocol and our previously published methods to quantitatively evaluate rodent knee histology28 are used to assess the severity of post-traumatic OA in 3, 6, and 9 month old male Lewis rats. Our methods begin with the respective experimental designs, with detailed methods provided thereafter.

In Vitro Validation of Multiplex Magnetic Capture

In magnetic capture, the unique properties of superparamagnetic nanoparticles are leveraged to move the first stage of an immunoprecipitation assay into a biologic fluid (i.e. in situ incubation26). To achieve this, superparamagnetic nanoparticles are embedded within a polymeric particle; then, the particle is coated with antibodies to molecular targets of interest (see Supplementary Figure 1). Because superparamagnetic nanoparticles do not retain stable magnetization in the absence of a magnetic field, these antibody-coated particles are able to distribute through a biological fluid, thereby binding the targeted molecules to the particle surface, and leaving other targets behind. Conversely, superparamagnetic nanoparticles acquire strong magnetization when a magnetic field is present; thus, following the incubation stage, the now biomarker-loaded particles can be magnetically recovered from the synovial fluid using magnetic probes26 or from lavage washes using a magnetic separator. Once recovered, molecular biomarkers and the collected particles can be quantified, thereby determining biomarker load within the fluid.

We have previously demonstrated the ability to detect a marker of cartilage catabolism26 and an OA-related chemokine29 using the magnetic capture approach. In this work, magnetic capture is expanded to multiplex detection for the first time, evaluating intra-articular levels of c-telopeptide of type II collagen (CTXII), interleukin-1β (IL1β), interleukin-6 (IL6), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα), and interferon-γ (IFNγ).

To confirm magnetic capture can simultaneously assess CTXII, IL1β, IL6, TNFα, and IFNγ, two benchtop experiments were designed (both outlined in Supplemental Figure 2). The first experiment evaluated biomarker collection and release with different concentrations of particles. Here, known amounts of our five molecular targets were blended together in PBS containing 2% bovine serum albumin and 2 mM EDTA (hereafter referred to as capture buffer); these amounts were 0.6 pg/μL CTXII, 2.0 pg/μL IL1β, 2.1 pg/μL IL6, 0.2 pg/μL TNFα, and 1.1 pg/μL IFNγ. Then, increasing concentrations of antibody-conjugated particles (see magnetic particle conjugation, 0-440 μg) in 2 μL of capture buffer were added to 8 μL of the biomarker blend, incubated for 2 hrs to achieve a binding equilibrium, and finally recovered from the biomarker blend using a magnetic separator. Particles were washed in capture buffer, re-separated using a magnetic separator, then incubated for 15 mins in 200 mM glycine-tris buffer containing 1% bovine serum albumin (pH 1.8, hereafter referred to as release buffer). This temporary pH treatment breaks non-covalent bonds between the antibody and molecular target, thereby separating the targeted molecules and particles for quantification. Following biomarker release, particles and the released biomarker were magnetically separated again, and both solutions are adjusted to pH 7.5. Molecular targets were then assayed using a CTXII ELISA or multiplex cytokine assay, and particles were quantified via optical absorbance (see detailed methods below).

Prior to use, it is also important to validate a magnetic capture measurement relative to an alternative, like a direct ELISA. To achieve this validation (see Supplemental Figure 2), a biomarker blend was created in capture buffer (0.8 pg/μL CTXII, 2.0 pg/μL IL1β, 2.1 pg/μL IL6, 0.2 pg/μL TNFα, and 1.1 pg/μL IFNγ). This biomarker blend was then diluted 2- or 4-times in capture buffer to create three different concentrations of biomarker mix. Then, 27.5 μg of antibody-conjugated particles in 2 μL of capture buffer (or the same amount of non-conjugated particles – no antibody control) were added to 8 μL of capture buffer (no biomarker control, n=3 per biomarker blend). Particles were incubated for 2 hrs to achieve a dynamic binding equilibrium; then, particles were isolated using a magnetic separator. Here, supernatant was assessed for non-bound biomarker, while particles were washed and treated in release buffer, as described above. Again, CTXII and cytokines were assessed with the CTX-II ELISA and MSD assay, respectively, and particles were counted using absorbance measurements.

Assessing the Effects of Age on Joint Damage and Intra-articular Inflammation in the Rat MCLT+MMT Model

The MCLT+MMT model is commonly referred to as the MMT model, as the medial collateral ligament transection is part of the original procedure described by Janusz et al.30 We note the MCLT in our abbreviation to align with our previous work with this model31–33. All studies described herein were conducted under IACUC-approved protocols at the University of Florida. Animals were housed in conventional housing on 12 hr light/dark cycles with standard chow and water provided ad libitum. Animals were monitored for signs of distress and body condition daily. A flowchart for the animal experiment is included in Supplemental Figure 3.

To assess the effects of age on post-traumatic OA, forty-eight Lewis rats were obtained from Charles River Laboratories and aged to 3, 6, or 9 months old (male). At each age, eight rats received either an MCLT+MMT surgery or a skin-incision (sham control), as described below. While some prior work in this model has used MCLT alone as a control30, our prior work demonstrates measurable synovial thickening, bony remodeling, and behavioral changes with MCLT alone, despite limited cartilage damage28; 31; 34. Since these synovial and bony changes may associate with inflammation, skin-incision alone was selected as a surgical control for this study. At 8 weeks post-surgery, animals were euthanized via cardiac puncture and exsanguination under deep anesthesia. Blood, acquired during exsanguination, was processed to serum using blood-separating vacutainers (Part #367981 BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immediately post-mortem, magnetic capture was performed in both the operated and contralateral knee. Here, 138 μg of antibody-conjugated magnetic particles in 10 μL of saline was injected into the operated and contralateral knee joint. After 2 hrs of incubation in the knee, particles were washed from the joint as follows: A small skin-incision was made on a lateral side of the patella. Then, using a micropipette, 10 repeated washes of 20 μl PBS were performed. New PBS was used for each wash, and the fluid collected after each wash was combined in an Eppendorf tube. Particles in this combined wash solution were isolated via a magnetic separator, washed two times with capture buffer, then treated in release buffer for 15 mins. Particles and biomarkers were then quantified as described below. Following magnetic capture, knees were dissected and processed for histology, as described below.

Magnetic Particle Conjugation

Commercially-available, streptavidin-functionalized particles were acquired from Life Technologies (Dynabeads MyOne™ Streptavidin C1, Cat. # 65001, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). In addition, biotinylated antibodies were acquired for CTXII (cat. # AC-08F1, ImmunoDiagnostic Systems, Copenhagen, Denmark), IL1β, IL6, TNFα, and IFNγ (cat. # 503505, 516003, 517703, and 518803, Biolegend, San Diego, CA, USA). Antibodies were conjugated to the particles’ surface as follows: First, an antibody mix was created containing 12 ng/μL anti-CTXII, 99 ng/μL anti-IL1β, 19 ng/μL anti-IL6, 99 ng/μL anti-TNFα, and 99 ng/μL anti-IFNγ antibodies. Then, particles were washed 3 times in PBS and incubated in the antibody mix for 2 hrs on a tube revolver at room temperature. Following room temperature incubation, particles in the antibody mix were moved to 4°C and incubated overnight. The following morning, particles were washed three times in capture buffer. Final antibody amounts per particle were 0.7 ng anti-CTXII per μg particle, 5.8 ng anti-IL1β per μg particle, 1.1 ng anti-IL6 per μ particle, 5.8 ng anti-TNFα per μg particle, and 5.8 ng anti-IFNγ per μg particle.

CTXII and Cytokine ELISA

CTXII was detected using the Cartilaps CTX-II ELISA kit (cat. #AC-08F1, ImmunoDiagnostic Systems Cartilaps kit, Copenhagen, Denmark). Similarly, IL1β, IL6, TNFα, and IFNγ were investigated using a customized rat pro-inflammatory panel II MSD kit (Cat. #K15059D-2, Meso Scale Diagnostics, Rockville, MD, USA). These ELISA kits were used according to the manufacturer instructions with the following modifications. First, to standardize the pH of the samples and the pH of the kit’s standards, a 200 mM glycine-tris buffer containing 1% bovine serum albumin (pH 7.5) was used in replacement of the buffer provided with the kits. Second, plates were incubated on a plate shaker at room temperature for 2 hrs.

Particle Counts

For particle quantification, particles were re-suspended in 60 μl of capture buffer. Particle aggregates were broken down by via sonication in an ice water bath (3 times at 1 min intervals, Model M1800H, Branson Ultrasonic Corporation, Danbury, CT, USA). Then, particle suspensions were read for absorbance at 450 nm using Synergy 2 Multi-Mode Microplate Reader. Suspensions of known particle concentrations were used as standards.

Animal Surgeries

Animals were first anesthetized in a 4% isoflurane sleep box, then transferred to a 1-2% isoflurane mask to maintain anesthesia. First, intra-operative buprenorphine was administered (0.05 mg/kg, SC); then, the right limb was shaved and aseptically prepared using three repeated applications of povidone-iodine scrub and ethanol, ending on a fourth povidone-iodine scrub application. Animals were then transferred to a sterile field and the prepared limb was draped with sterile surgical towels. For all surgeries, a midline skin-incision was made along the medial aspect of the patellar ligament, with the medial collateral ligament (MCL) exposed via blunt dissection. At this point, the surgeon was notified of the procedure. If the procedure was a skin-incision sham, animals were closed using PDS absorbable suture (4.0) for the muscle and skin. If the procedure was an MCL transection and medial meniscus transection (MCLT+MMT) surgery, the MCL was transected, the knee was placed in a valgus orientation to expose the central portion of the medial meniscus, and then the medial meniscus was transected. MCLT+MMT animals were closed in the same manner as skin-incision animals, and for both groups, buprenorphine was maintained with repeated doses every 12 hrs for 48 hrs following surgery.

Histology

Both the operated and contralateral knees were dissected and placed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 48 hrs. Following fixation, knees were decalcified in 10% formic acid for 2 weeks, dehydrated through an ethanol ladder, and embedded in paraffin wax via vacuum infiltration. Knees were then sectioned frontally at 10 μm with at least one section acquired every 100 μm between the anterior and posterior horn of the medial meniscus. Slides were stained with safranin-O/fast green and graded using our graphic user interface for the evaluation of knee OA (GEKO)28. GEKO is a quantitative histological grading tool based on the OARSI histopathology recommendations for the rat35.

In this study, two blinded graders used GEKO to independently trace the cartilage surface, osteophyte, osteochondral interface, growth plate, and medial joint capsule. Then, GEKO calculates histology scores based on these user-define traces; histology scores were averaged between the two graders. In addition, lesion morphometry was calculated via GEKO by determining the distance between the osteochondral interface and the cartilage surface for the medial compartment of the tibial plateau.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using an analysis of variance (ANOVA) approach. For intra-articular measurements of CTXII, IL1β, IL6, TNFα, and IFNγ, a full-factorial, 3-way ANOVA was used, accounting for limb, age, and surgery type as factors. For histology, an analogous full-factorial, 3-way ANOVA was used. For serum assessments, the ANOVA was reduced to a full-factorial 2-way ANOVA, accounting for age and surgery type as factors. For all ANOVAs, a post-hoc Tukey’s HSD test was performed when indicated by the ANOVA main effect or interaction. Data are presented as scatterplots with the exception of lesion morphometry data, which is presented as the average ± 95% confidence interval.

Results

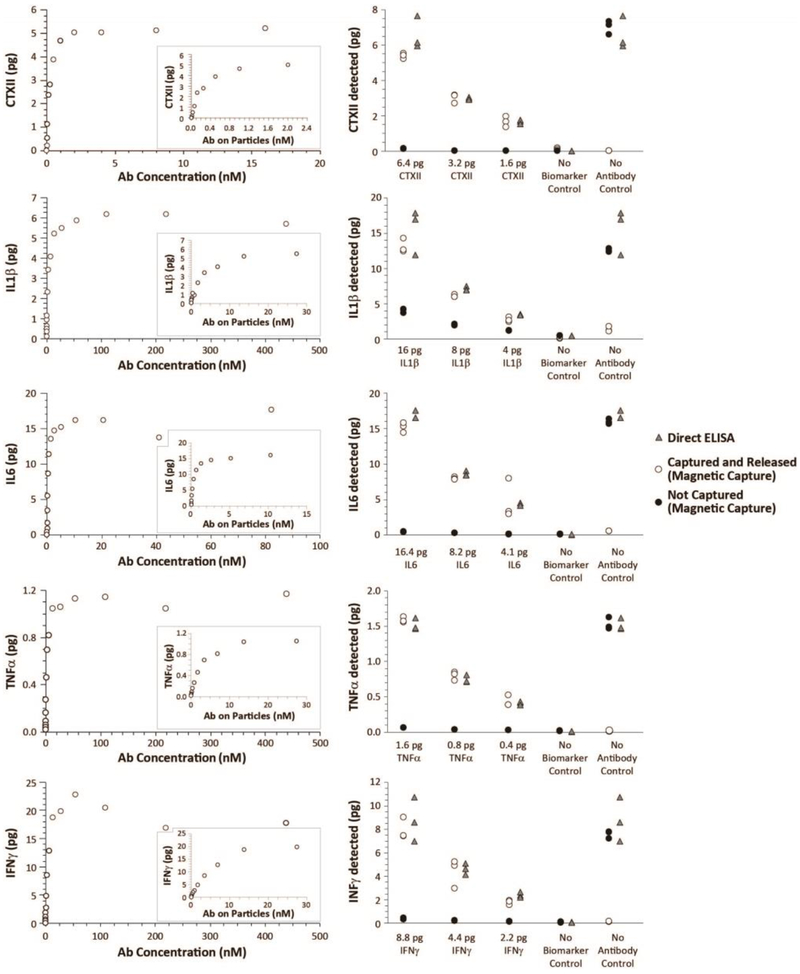

Validation of our multiplex magnetic capture procedure is provided in Figure 1. As expected, each molecular target plateaued as particle amount (and thereby antibody concentrations) increased (Figure 1, Left Column). Moreover, low pH was able to release the molecular targets from the particles. By assuring magnetic capture was operating in the plateau region of the binding curve (see 26), the amount of CTXII, IL1β, IL6, TNFα, and IFNγ quantified via magnetic capture was comparable to direct ELISA (Figure 1, Right Column). A minor issue was observed for IL1β and IL6, where magnetic capture values were slightly below values from direct ELISA (Figure 1, Row 2 and Row 3, respectively). However, the bound to unbound proportion of IL1β and IL6 was stable across concentration, allowing us to account for this issue in our final estimation of these cytokines.

Figure 1: Proof-of-principle and validation of multiplex magnetic capture.

As a validation of multiplex magnetic capture, two experiments were designed (See Supplemental Figure 2). First, 0.6 pg/μL CTXII, 2.0 pg/μL IL1β, 2.1 pg/μL IL6, 0.2 pg/μL TNFα, and 1.1 pg/μL IFNγ were blended together in a biomarker blend. Then, increasing concentrations of antibody-conjugated particles (and thereby increasing concentrations of antibody) were added to biomarker blend. As particle concentrations increased, biomarker was depleted from the sample, as demonstrated by the plateauing collection curve (Left Column). Moreover, pH treatment was able to release the biomarker for quantification. Second, to validate magnetic capture relative to direct ELISA, a second biomarker blend was created (0.8 pg/μL CTXII, 2.0 pg/μL IL1β, 2.1 pg/μL IL6, 0.2 pg/μL TNFα, and 1.1 pg/μL IFNγ). This biomarker blend was then diluted 2- or 4-times. Antibody-conjugated particles were added to 8 μL of each biomarker blend (n=3 per biomarker blend); capture buffer without biomarkers (no biomarker control) and bare particles (no antibody control) were used as controls. Direct ELISAs were conducted on the same samples as a positive control. As shown in the Right Column, a multiplex magnetic capture was able to simultaneously assay CTXII, IL1β, IL6, TNFα, and IFNγ. While minor losses were observed in IL1β and IL6, these losses were stable and predictable across the different concentrations assessed. Combined, these data demonstrate these molecular targets can be collected, released, and assayed via magnetic capture.

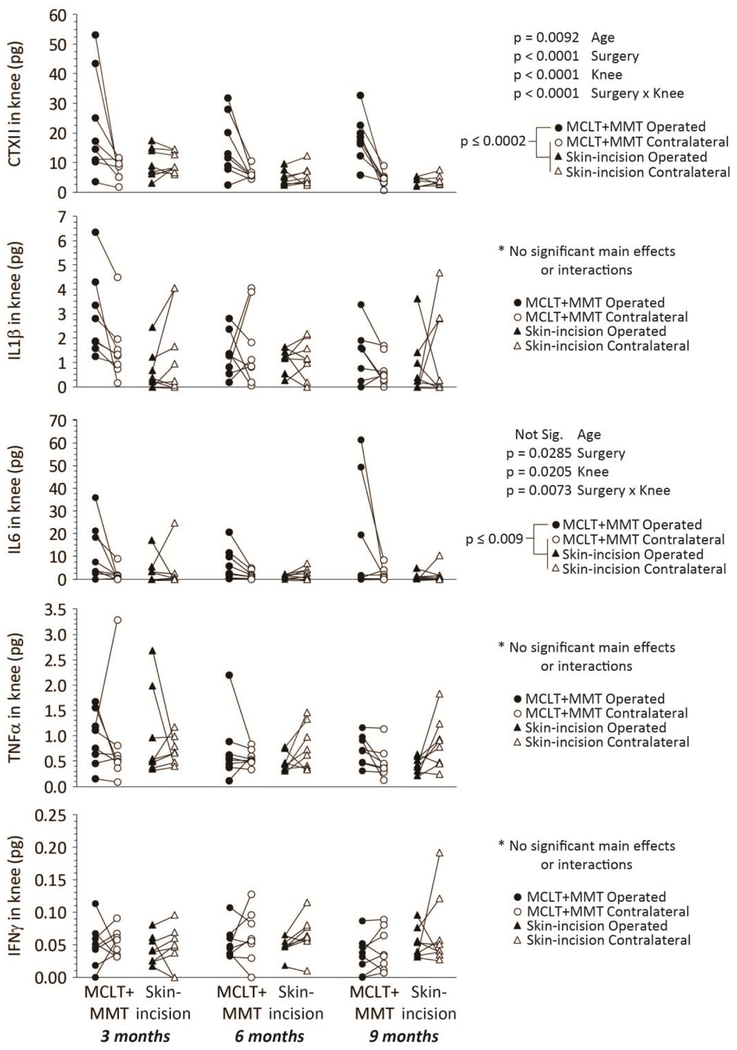

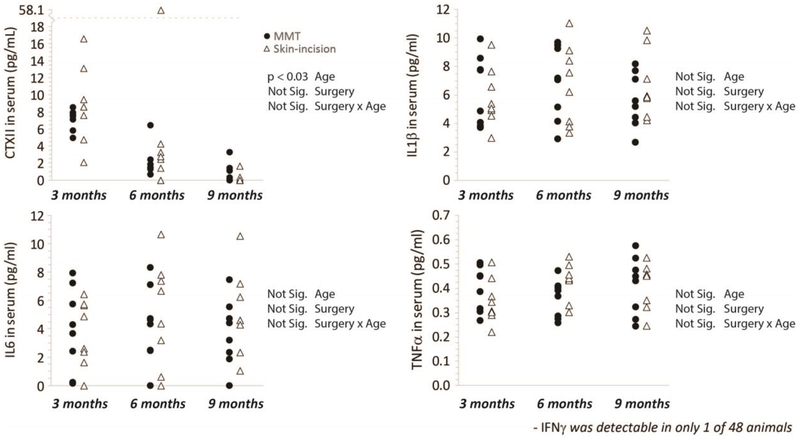

Using magnetic capture, CTXII and multiple cytokines were evaluated in the OA-affected and contralateral knee (Figure 2, lines indicate samples from the same animal). While particle collection data is used to normalize biomarker data between samples (see Supplemental Figure 1), particle collection efficiency are provided as a reference in Supplemental Figure 4. Both CTXII and IL6 were elevated in the MCLT+MMT operated knee relative to all other groups; no significant differences were observed for IL1β, TNFα, or IFNγ. In the serum, no changes in CTXII, IL6, IL1β, or TNFα were observed (Figure 3), indicating circulating levels of these markers were not markedly affected by local OA pathogenesis. IFNγ was detectable in 1 of the 48 serum samples, and the one detectable sample was near the lower limit of detection for our assay. For cytokines, age-effects were not found in synovial fluid or serum, while CTXII was found to decrease with age in both synovial fluid and serum. The CTXII results confirm a known age-dependence for CTXII measurements in other species36; 37.

Figure 2: Intra-articular levels of CTXII, IL1β, IL6, TNFα, and IFNγ in the Rat MCLT+MMT Model of Knee OA.

Magnetic capture revealed elevated levels of CTXII and IL6 in the MCLT+MMT operated joint relative to contralateral and skin-incision controls (Row 1 and Row 3). Differences in IL1β, TNFα, and IFNγ were not observed. Age was found to affect the measured levels of CTXII in the synovial fluid, aligning with prior results describing decreases in serum-level CTXII with age36; 37. Relevant ANOVA main effect and interaction p-values are provided next to each figure; p-values are associated with a post-hoc Tukey’s HSD test. Data linked by a line are from the same animal (paired scatterplot).

Figure 3: Serum levels of CTXII, IL1β, IL6, TNFα, and IFNγ in the Rat MCLT+MMT Model of Knee OA.

Serum was collected at the time of euthanasia, and then assessed using a CTXII and cytokine multiplex assay. Differences were not observed between MCLT+MMT and skin incision animals at 8 weeks after surgery. Age was found to affect the measured levels of CTXII in the serum, again aligning with prior results on CTXII concentration related to age36; 37. Relevant ANOVA main effect and interaction p-values are provided in the statistical table next to each figure. Note, IFNγ concentrations were only above the assay detection threshold in 1 of the 48 animals assessed; as such, these data are not shown.

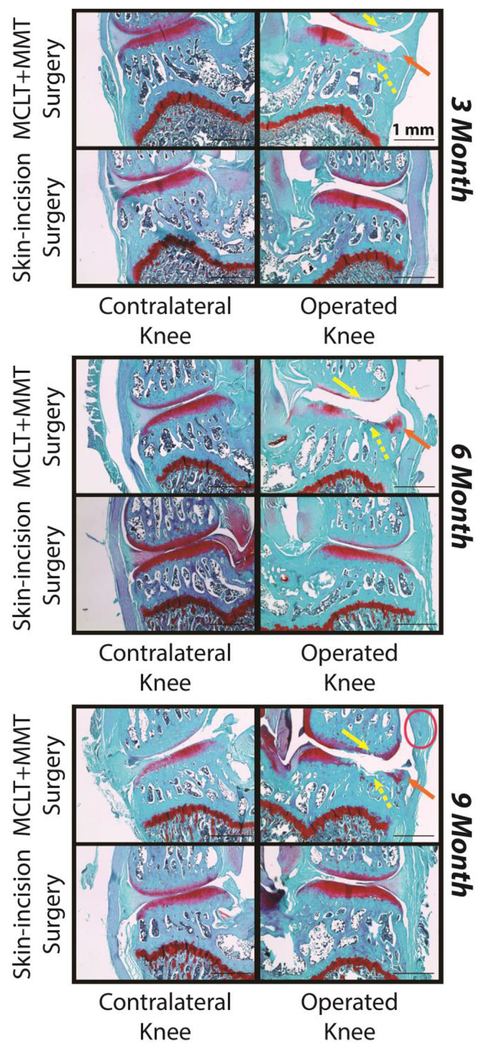

Representative histological images are provided for the medial compartment of the operated and contralateral limb (Figure 4). All animals are 8 weeks post-surgery, where the age noted in the figure is age at the time of surgery. In MCLT+MMT operated knees, clear evidence of a cartilage lesion can be observed on the medial tibial cartilage (yellow dashed arrow) and medial femoral cartilage (yellow solid arrow). Osteophytes can also be observed along the medial margins of the tibial plateau in MCLT+MMT operated knees (orange arrow). Finally, evidence of medial joint capsule thickening was observed in some sections (pink circle).

Figure 4: Representative Histological Images.

Images of the medial compartment are provided for the operated knee (right) and contralateral knee (left). In all age groups, tibial cartilage damage was observed (yellow, dashed arrows), femoral cartilage damage was observed (yellow, solid arrows), and osteophyte formation was observed (orange arrows). Synovitis was apparent is some samples from MCLT+MMT operated knees (pink oval), but was not consistently observed at any age group.

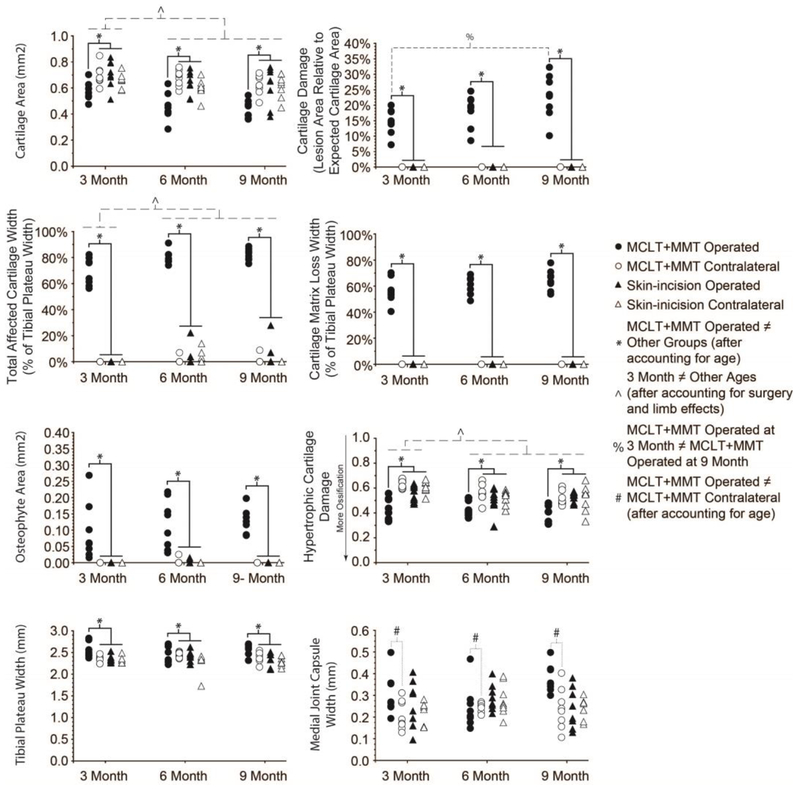

Quantitative histological grading is provided in Figure 5, with associated statistical analysis provided in Supplemental Table 1. Histological sections from MCLT+MMT operated knees had evidence of cartilage damage (Row 1 & 2), including reduced cartilage area, greater cartilage damage (lesion area/expected cartilage area), greater total affected cartilage width (which includes proteoglycan loss), and greater cartilage matrix loss width (cartilage loss, not including proteoglycan loss). In addition to cartilage damage, MCLT+MMT operated knees had strong evidence of osteophyte formation (Row 3, Left Column) and hypertrophic cartilage ossification (Row 3, Right Column). Tibial plateau widths were widest in MCLT+MMT operated knees (Row 4, Left Column); and finally, the synovial capsule was thicker in MCLT+MMT operated knees compared to the contralateral limb control (Row 5, Right Column).

Figure 5: Quantitative Histological Scores.

The cartilage lesion, osteochondral interface, growth plate, osteophyte (when present), and medial joint capsule were traced in GEKO, with histological scores calculated from these traces. Cartilage parameters are shown in Row 1 & 2. Relative to contralateral and skin-incision controls, MCLT+MMT operated knees had decreased cartilage area, more cartilage damage, larger total degeneration widths (which includes proteoglycan loss), and larger cartilage matrix loss widths (which does not include proteoglycan loss). Bone and synovial changes are shown in Row 3 & 4. Here, MCLT+MMT operated knees had larger osteophytes, more ossification of the hypertrophic cartilage, and larger tibial plateau widths relative to contralateral and skin-incision controls. Finally, the medial joint capsule width in MCLT+MMT operated knees was wider relative to its contralateral control. Age significantly affected measures of cartilage damage. Histological data demonstrate that, relative to 3 month old animals, 6 month and 9 month old animals had decreased cartilage area, larger total cartilage degeneration widths, and more evidence of hypertrophic cartilage damage. Cartilage damage (lesion size) was also larger in 9 month old animals relative to 3 month old animals. Relevant ANOVA main effect and interaction p-values are provided in Supplemental Table 1.

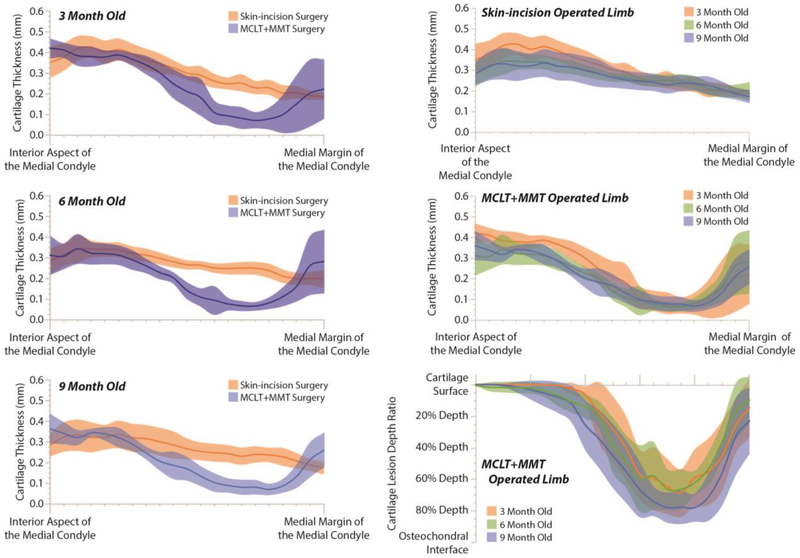

The age of the animal significantly affected cartilage measures. Relative to 3 month old animals, 6 month and 9 month old animals had lower cartilage areas, greater total affected cartilage widths, and more significant evidence of hypertrophic cartilage damage. In addition, 9 month old animals with MCLT+MMT surgery had greater cartilage damage than 3 month old animals with MCLT+MMT surgery. These age-effects were also observed in lesion morphometry (Figure 6). Here, solid lines represent the average thickness or depth ratio of the cartilage, starting at the interior aspect of the medial compartment tibial plateau (left) and proceeding to the medial margin of the medial compartment tibial plateau (right); shaded areas represent a 95% confidence interval. While the lines and bands undulate, this does not necessarily indicate cartilage surface roughness. Instead, natural variance occurs due to focal lesions or fissures in a few select samples, and these focal lesions caused the variance bands and average roughness to move as a function of location. As can be seen in the first column of Figure 6, lesions are observed for MCLT+MMT operated knees, with the greatest losses of cartilage occurring closer to the medial margin of the tibial plateau. In the second column of Figure 6, cartilage thinning can be seen in skin-incision knees, particularly toward the interior aspect of the medial condyle (Top Row, Right Column). Moreover, for MCLT+MMT knees, the cartilage lesion appears to be wider, but not deeper, for 6 month and 9 month animals relative to 3 month old animals (Bottom Row, Right Column).

Figure 6: Cartilage Lesion Morphometry.

Like bone histomorphometery, cartilage lesion morphometry seeks to quantify lesion shape characteristics. Here, solid lines represent the average thickness or depth ratio of the cartilage, starting at the interior aspect of the medial compartment tibial plateau (left) and proceeding to the medial margin of the medial compartment tibial plateau (right); the shaded areas of like color represent a 95% confidence interval. These band are calculated at 5% steps, moving from the interior aspects of the medial condyle and proceeding to the medial margin. While these lines and bands undulate, this does not necessarily indicate the cartilage surface is rough. Instead, focal lesions or crevice-like fissures can occur in a few select samples, and this occurrence can temporarily shift the mean thickness and create an undulating average thickness. As can be seen in Column 1, cartilage thickness decreases in MCLT+MMT operated knees due to cartilage lesion formation, with the greatest losses of cartilage occurring closer to the medial margin. In Column 2, cartilage thinning is observed in skin-incision knees (Top Row). Moreover, for MCLT+MMT operated knees, the cartilage lesion appears to be wider, but not deeper, for 6 month and 9 month animals relative to 3 month old animals (Middle and Bottom Row).

Discussion

The objective for this study was to evaluate how animal age affects the severity of intra-articular inflammation and joint damage in the rat MCLT+MMT model of knee OA. Our data show evidence of more severe cartilage damage with animal age, but not necessarily elevated levels of intra-articular inflammation. These results mirror prior reports for the rat ACLT model, where Ferrandiz et al24 also report increased severity of joint degeneration in 12-month old rats relative to 2-month old rats, but did not observe age-related effects on inflammatory mediators. In our work, elevated levels of IL6 were observed in the OA-affected joint, but intra-articular levels of IL6 were not affected by the age of the animal. On the other hand, histological evidence of cartilage damage (cartilage area, cartilage lesion width, and hypertrophic cartilage damage) were affected by animal age. Combined, these data indicate cartilage becomes less resilient to OA pathogenesis with age, but this more rapid and more severe OA pathogenesis does not necessarily cause higher levels of intra-articular inflammation in 3, 6, and 9 month old rats.

While the ages of animals used in this study align reasonably well with past studies, these ages do not reflect the typical age range for age-related OA in humans. There is no universal method for correlating a rat’s age to a human, but based on a phased aging model of the rat through different life cycles, a 3-month old rat is approximately equivalent to a 13 year-old human; a 6-month old rat is approximately a 20 year-old human; and, a 9-month old rat is approximately to a 28 year-old human25. Thus, while a 9-month rat is not elderly, most studies of post-traumatic OA in the rat investigate 2-3 month old animals (~12-13-year-old human). Although age-associated OA is not typical at the corresponding human ages, these data are more reflective of the expected rapidity of OA progression following a traumatic injury in 18-28 year-old male athletes. On this note, a limitation of this study is the use of male rats alone; this was selected as the rate of OA progression subsequent to MCLT+MMT surgery is well known for male rats. However, future work is needed to investigate age-related OA progression in female rats.

In the prior work on the rat ACLT model24, inflammatory cytokine analysis noted elevated levels of IL1β and IL17A in the OA-affected joint using ELISAs on pulverized tissue. Using our magnetic capture approach, elevated levels of IL6 were detected, but not IL1β (we did not investigate IL17A). The methods used by Ferrandiz and colleagues24 are likely to be more sensitive to inflammatory changes related to OA. However, their methods do not allow for the assessment histology and inflammatory mediators in the same joint. Originally, our goal was to correlate inflammatory mediators to the severity of joint damage, which magnetic capture enables since the joint tissues are not destroyed during cytokine collection. However, since intra-articular inflammation was not found to increase with age (while OA-related histological damage did increase with age), the comparison of intra-articular inflammation and age was no longer relevant.

Despite the lack of inflammatory changes with age, our work does demonstrate the utility of computer-aided, quantitative histological analyses and lesion morphometry to study age-effects in preclinical models of knee OA. Often, histological analyses of knee OA in preclinical models use semi-quantitative ranks, such as the Mankin scheme38 or the 2006 OARSI histopathology score39. While these ranks allow graders to integrate information occurring in multiple tissues before assigning a score, quantitative measures allow for a more thorough assessment of changes within different joint tissues. In 2010, OARSI updated their recommendations for the histological assessment of OA in different species; in the histological assessment schemes for the rat, a number of quantitative measures of joint damage were recommended35. Inspired by this quantitative approach, our group developed GEKO28, a free and open-source MATLAB package for knee OA histology evaluation. Here, GEKO-based scores were able to identify age-related effects on cartilage damage, partly due to the increased resolution that comes with quantitative measure of cartilage and bone damage. Moreover, GEKO enabled the creation of lesion morphometry graphs, which allowed us to visualize the average shape of the lesion as a function of age.

The lesion morphometry in Figure 6 presents both cartilage thickness maps and depth ratio maps. The depth ratio is the cartilage thickness divided by the expected thickness (see 35). However, because cartilage thickness decreases with age, the depth ratio also decreases due to a change in the denominator. As such, the cartilage thickness in the 6 month and 9 month MCLT+MMT operated knees are similar, while the depth ratio is slightly different. These results highlight the need to investigate multiple variables to understand the progression of joint damage in OA-affected knees.

Many prior studies of knee OA identified elevated levels of IL1β2; 40; however, we were unable to identify a statistically-significant elevation of IL1β via our multiplex magnetic capture procedure. It should be noted that, at the most common age range for OA preclinical studies (3 months old), IL1β levels in the OA-affected joint were higher than IL1β levels in the contralateral control (8 of 8 animals); however, differences in intra-articular IL1β between the OA and contralateral knee did not occur in older ages. As such, statistical significance in IL1β may be masked by age effects. Alternatively, our data in Figure 1 (Left Column) show a suboptimal collection of IL1β, which may be associated with an antibody affinity that is lower than other targets29. In addition, there were some losses of IL1β during pH release, resulting in slightly lower values than a direct ELISA in our benchtop validation (see Figure 1, Right Column). These methodological issues may have also lowered our ability to detect IL1β. As such, our inability to detect a statistically-significant shift in IL1β in this study does not necessarily diverge from past reports on this cytokine in OA preclinical models.

IFNγ was at relatively low levels in all of our samples. This result was expected, as IFNγ has not been identified as a primary cytokine in OA pathogenesis. Nonetheless, IFNγ was included in our development of multiplex magnetic capture as a control for other possible inflammatory activity in the joint.

In conclusion, these data indicate the severity of cartilage damage subsequent to MCLT+MMT surgery in the rat is related to the rat’s age at the time of the simulated injury. However, despite greater levels of cartilage damage with age, intra-articular inflammation was not necessarily affected. At this time, it is not known whether the observed increase in severity of cartilage damage with age in our model is related to age-related changes in the cartilage matrix, reduced resilience to inflammatory mediators, or other unknown factors. Nonetheless, these data demonstrate joint damage subsequent to a simulated joint injury may be accelerated and more severe as the animal ages.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health under grants R01AR068424 and R01AR071335, and by graduate student fellowships from the Herbert Wertheim College of Engineering and J. Crayton Pruitt Family Department of Biomedical Engineering at the University of Florida. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the University of Florida.

Footnotes

Disclosure of interest

The authors have no conflicts to report.

References

- 1.Loeser RF, Goldring SR, Scanzello CR, et al. 2012. Osteoarthritis: a disease of the joint as an organ. Arthritis Rheum 64:1697–1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldring MB, Otero M. 2011. Inflammation in osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 23:471–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalaitzoglou E, Griffin TM, Humphrey MB. 2017. Innate Immune Responses and Osteoarthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 19:45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robinson WH, Lepus CM, Wang Q, et al. 2016. Low-grade inflammation as a key mediator of the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 12:580–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scanzello CR. 2017. Role of low-grade inflammation in osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 29:79–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orlowsky EW, Kraus VB. 2015. The role of innate immunity in osteoarthritis: when our first line of defense goes on the offensive. J Rheumatol 42:363–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loeser RF. 2011. Aging and osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 23:492–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berenbaum F 2013. Osteoarthritis as an inflammatory disease (osteoarthritis is not osteoarthrosis!). Osteoarthritis Cartilage 21:16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berenbaum F, Meng QJ. 2016. The brain-joint axis in osteoarthritis: nerves, circadian clocks and beyond. Nat Rev Rheumatol 12:508–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greene MA, Loeser RF. 2015. Aging-related inflammation in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 23:1966–1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loeser RF. 2013. Aging processes and the development of osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 25:108–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loeser RF, Collins JA, Diekman BO. 2016. Ageing and the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 12:412–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Kraan PM. 2017. Factors that influence outcome in experimental osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 25:369–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hashimoto K, Oda Y, Nakamura F, et al. 2017. Lectin-like, oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1-deficient mice show resistance to age-related knee osteoarthritis. Eur J Histochem 61:2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyd LM, Richardson WJ, Allen KD, et al. 2008. Early-onset degeneration of the intervertebral disc and vertebral end plate in mice deficient in type IX collagen. Arthritis and Rheumatism 58:164–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zemmyo M, Meharra EJ, Kühn K, et al. 2003. Accelerated, aging-dependent development of osteoarthritis in alpha1 integrin-deficient mice. Arthritis Rheum 48:2873–2880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bendele AM, Hulman JF. 1988. Spontaneous cartilage degeneration in guinea pigs. Arthritis Rheum 31:561–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bendele AM, White SL, Hulman JF. 1989. Osteoarthrosis in guinea pigs: histopathologic and scanning electron microscopic features. Lab Anim Sci 39:115–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei L, Fleming BC, Sun X, et al. 2010. Comparison of differential biomarkers of osteoarthritis with and without posttraumatic injury in the Hartley guinea pig model. J Orthop Res 28:900–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Hooge AS, van de Loo FA, Bennink MB, et al. 2005. Male IL-6 gene knock out mice developed more advanced osteoarthritis upon aging. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 13:66–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsui Y, Iwasaki N, Kon S, et al. 2009. Accelerated development of aging-associated and instability-induced osteoarthritis in osteopontin-deficient mice. Arthritis Rheum 60:2362–2371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blaker CL, Little CB, Clarke EC. 2017. Joint loads resulting in ACL rupture: Effects of age, sex, and body mass on injury load and mode of failure in a mouse model. J Orthop Res 35:1754–1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang H, Skelly JD, Ayers DC, et al. 2017. Age-dependent Changes in the Articular Cartilage and Subchondral Bone of C57BL/6 Mice after Surgical Destabilization of Medial Meniscus. Sci Rep 7:42294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferrándiz ML, Terencio MC, Ruhí R, et al. 2014. Influence of age on osteoarthritis progression after anterior cruciate ligament transection in rats. Exp Gerontol 55:44–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sengupta P 2013. The Laboratory Rat: Relating Its Age With Human’s. Int J Prev Med 4:624–630. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yarmola EG, Shah Y, Arnold DP, et al. 2016. Magnetic Capture of a Molecular Biomarker from Synovial Fluid in a Rat Model of Knee Osteoarthritis. Annals of Biomedical Engineering 44:1159–1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yarmola EG, Shah YY, Lakes EH, et al. Accepted Use of magnetic capture to identify elevated levels of CCL2 following intra-articular injection of monoiodoacetate in rats. Connective Tissue Research. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kloefkorn HE, Jacobs BY, Xie DF, et al. 2019. A graphic user interface for the evaluation of knee osteoarthritis (GEKO): an open-source tool for histological grading. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 27:114–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yarmola E, Shah Y, Lakes E, et al. 2017. CCL2 detection in a rat monoiodoacetate osteoarthritis model using magnetic capture. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage Volume 25:Page S102 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Janusz MJ, Bendele AM, Brown KK, et al. 2002. Induction of osteoarthritis in the rat by surgical tear of the meniscus: Inhibition of joint damage by a matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 10:785–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kloefkorn HE, Jacobs BY, Loye AM, et al. 2015. Spatiotemporal gait compensations following medial collateral ligament and medial meniscus injury in the rat: correlating gait patterns to joint damage. Arthritis Res Ther 17:287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kloefkorn HE, Allen KD. 2017. Quantitative histological grading methods to assess subchondral bone and synovium changes subsequent to medial meniscus transection in the rat. Connective Tissue Research 58:373–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jacobs BY, Dunnigan K, Pires-Fernandes M, et al. 2016. Unique spatiotemporal and dynamic gait compensations in the rat monoiodoacetate injection and medial meniscus transection models of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kloefkorn HE, Allen KD. 2016. Quantitative histological grading methods to assess subchondral bone and synovium changes subsequent to medial meniscus transection in the rat. Connect Tissue Res:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gerwin N, Bendele AM, Glasson S, et al. 2010. The OARSI histopathology initiative - recommendations for histological assessments of osteoarthritis in the rat. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 18 Suppl 3:S24–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang CC, Lee CC, Wang CJ, et al. 2014. Effect of age-related cartilage turnover on serum C-telopeptide of collagen type II and osteocalcin levels in growing rabbits with and without surgically induced osteoarthritis. Biomed Res Int 2014:284784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leung YY, Huebner JL, Haaland B, et al. 2017. Synovial fluid pro-inflammatory profile differs according to the characteristics of knee pain. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mankin HJ, Dorfman H, Lippiello L, et al. 1971. Biochemical and metabolic abnormalities in articular cartilage from osteo-arthritic human hips. II. Correlation of morphology with biochemical and metabolic data. J Bone Joint Surg Am 53:523–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pritzker KP, Gay S, Jimenez SA, et al. 2006. Osteoarthritis cartilage histopathology: grading and staging. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 14:13–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goldring MB, Otero M, Plumb DA, et al. 2011. Roles of inflammatory and anabolic cytokines in cartilage metabolism: signals and multiple effectors converge upon MMP-13 regulation in osteoarthritis. Eur Cell Mater 21:202–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.