Abstract

Background

People with end‐stage kidney disease (ESKD) treated with dialysis are frequently affected by major depression. Dialysis patients have prioritised depression as a critically important clinical outcome in nephrology trials. Psychological and social support are potential treatments for depression, although a Cochrane review in 2005 identified zero eligible studies. This is an update of the Cochrane review first published in 2005.

Objectives

To assess the effect of using psychosocial interventions versus usual care or a second psychosocial intervention for preventing and treating depression in patients with ESKD treated with dialysis.

Search methods

We searched Cochrane Kidney and Transplant's Register of Studies up to 21 June 2019 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. Studies in the Register are identified through searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE, conference proceedings, the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs of psychosocial interventions for prevention and treatment of depression among adults treated with long‐term dialysis. We assessed effects of interventions on changes in mental state (depression, anxiety, cognition), suicide, health‐related quality of life (HRQoL), withdrawal from dialysis treatment, withdrawal from intervention, death (any cause), hospitalisation and adverse events.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently selected studies for inclusion and extracted study data. We applied the Cochrane 'Risk of Bias' tool and used the GRADE process to assess evidence certainty. We estimated treatment effects using random‐effects meta‐analysis. Results for continuous outcomes were expressed as a mean difference (MD) or as a standardised mean difference (SMD) when investigators used different scales. Dichotomous outcomes were expressed as risk ratios. All estimates were reported together with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Main results

We included 33 studies enrolling 2056 participants. Twenty‐six new studies were added to this 2019 update. Seven studies originally excluded from the 2005 review were included as they met the updated review eligibility criteria, which have been expanded to include RCTs in which participants did not meet criteria for depression as an inclusion criterion.

Psychosocial interventions included acupressure, cognitive‐behavioural therapy, counselling, education, exercise, meditation, motivational interviewing, relaxation techniques, social activity, spiritual practices, support groups, telephone support, visualisation, and voice‐recording of a psychological intervention.

The duration of study follow‐up ranged between three weeks and one year. Studies included between nine and 235 participants. The mean study age ranged between 36.1 and 73.9 years.

Random sequence generation and allocation concealment were at low risk of bias in eight and one studies respectively. One study reported low risk methods for blinding of participants and investigators, and outcome assessment was blinded in seven studies. Twelve studies were at low risk of attrition bias, eight studies were at low risk of selective reporting bias, and 21 studies were at low risk of other potential sources of bias.

Cognitive behavioural therapy probably improves depressive symptoms measured using the Beck Depression Inventory (4 studies, 230 participants: MD ‐6.10, 95% CI ‐8.63 to ‐3.57), based on moderate certainty evidence. Cognitive behavioural therapy compared to usual care probably improves HRQoL measured either with the Kidney Disease Quality of Life Instrument Short Form or the Quality of Life Scale, with a 0.5 standardised mean difference representing a moderate effect size (4 studies, 230 participants: SMD 0.51, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.83) , based on moderate certainty evidence. Cognitive behavioural therapy may reduce major depression symptoms (one study) and anxiety, and increase self‐efficacy (one study). Cognitive behavioural therapy studies did not report hospitalisation.

We found low‐certainty evidence that counselling may slightly reduce depressive symptoms measured with the Beck Depression Inventory (3 studies, 99 participants: MD ‐3.84, 95% CI ‐6.14 to ‐1.53) compared to usual care. Counselling reported no difference in HRQoL (one study). Counselling studies did not measure risk of major depression, suicide, or hospitalisation.

Exercise may reduce or prevent major depression (3 studies, 108 participants: RR 0.47, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.81), depression of any severity (3 studies, 108 participants: RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.87) and improve HRQoL measured with Quality of Life Index score (2 studies, 64 participants: MD 3.06, 95% CI 2.29 to 3.83) compared to usual care with low certainty. With moderate certainty, exercise probably improves depression symptoms measured with the Beck Depression Inventory (3 studies, 108 participants: MD ‐7.61, 95% CI ‐9.59 to ‐5.63). Exercise may reduce anxiety (one study). No exercise studies measured suicide risk or withdrawal from dialysis.

We found moderate‐certainty evidence that relaxation techniques probably reduce depressive symptoms measured with the Beck Depression Inventory (2 studies, 122 participants: MD ‐5.77, 95% CI ‐8.76 to ‐2.78). Relaxation techniques reported no difference in HRQoL (one study). Relaxation studies did not measure risk of major depression or suicide.

Spiritual practices have uncertain effects on depressive symptoms measured either with the Beck Depression Inventory or the Brief Symptom Inventory (2 studies, 116 participants: SMD ‐1.00, 95% CI ‐3.52 to 1.53; very low certainty evidence). No differences between spiritual practices and usual care were reported on anxiety (one study), and HRQoL (one study). No study of spiritual practices evaluated effects on suicide risk, withdrawal from dialysis or hospitalisation.

There were few or no data on acupressure, telephone support, meditation and adverse events related to psychosocial interventions.

Authors' conclusions

Cognitive behavioural therapy, exercise or relaxation techniques probably reduce depressive symptoms (moderate‐certainty evidence) for adults with ESKD treated with dialysis. Cognitive behavioural therapy probably increases health‐related quality of life. Evidence for spiritual practices, acupressure, telephone support, and meditation is of low certainty . Similarly, evidence for effects of psychosocial interventions on suicide risk, major depression, hospitalisation, withdrawal from dialysis, and adverse events is of low or very low certainty.

Plain language summary

Are psychosocial interventions effective for treating depression among people on dialysis?

What is the issue?

Depression is frequently experienced by people treated with dialysis. Dialysis patients consider treatments that help with depression to be a high priority. Despite that fact that psychosocial interventions have been shown to decrease depression in various chronic diseases, we are very uncertain about whether treatments prevent or treat depression for dialysis patients as studies are rare.

What did we do?

This evidence is current to June 2019. We searched the medical literature and identified 33 studies with 2056 participants treated by dialysis. Studies evaluated a range of possible treatments including acupressure, cognitive‐behavioural therapy (CBT), counselling, education, exercise, meditation, motivational interviewing, relaxation techniques, social activity, spiritual practices, support groups, telephone support, visualisation, and voice control compared to usual care or other psychosocial treatments. We also checked the quality of the information in the studies to learn how certain we could be about the results.

What did we find?

We are moderately certain that CBT, exercise, and relaxation techniques probably decrease symptoms of depression for patients treated with long‐term dialysis. Counselling may slightly decrease depression symptoms, while we are uncertain whether acupressure, telephone support, or meditation make any difference. We found moderate certainty evidence that CBT provides higher quality of life for dialysis patients. Studies did not measure effects of psychosocial treatments on major depression, suicide risk, and whether therapies made any difference to anxiety, hospital admissions, or withdrawal from dialysis treated is uncertain. Adverse events from treatment is very uncertain.

Some study authors did not report the methods for their studies clearly, so we could not be certain whether patients truly had a random chance of being in each treatment group or whether the trial results were assessed by people knowing which treatments that patients actually received. For most outcomes, we identified very few studies, which decreased our confidence in the results.

Conclusions

CBT, exercise, and relaxation techniques probably decrease depressive symptoms for dialysis patients while CBT also improves life quality. Counselling may slightly reduce depression among those receiving dialysis. We are not certain whether interventions prevent or treat major depression, anxiety, suicide risk, or withdrawal from dialysis care before death or whether psychological and social treatments have adverse effects.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Depression is the most common psychological problem in patients undergoing dialysis (Finkelstien 2000; Kimmel 1993; Levenson 1991). Approximately one‐quarter of dialysis patients meet diagnostic criteria for major depression (Palmer 2013a; Szeifert 2012). The main factors that contribute to the develop of depressive symptoms are medications, reduction of physical function and dietary restrictions (Farrokhi 2014). The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Patient Health Questionnaire and Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale are validated tools for depression in people undergoing haemodialysis (HD), although the optimal screening tool is still uncertain (King‐Wing Ma 2016).

Depression can adversely affect the well‐being of patients receiving long‐term dialysis in several ways. Health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) of patients on chronic dialysis has been shown to correlate more strongly with depression than with dialysis adequacy measures (Martin 2000; Steele 1996). Depression in dialysis patients is associated with lower adherence to dialysis prescriptions (Kaveh 2001; Kimmel 1995) and recommended fluid restrictions (Everett 1993), which may lead to poorer clinical outcomes (Chilcot 2018). One study (Davies 2003) found a significant association between depression and intolerance to antihypertensive drugs because of nonspecific adverse effects in the general population. This may be of relevance to patients treated with long‐term dialysis as 80% of HD and 50% of peritoneal dialysis (PD) patients are hypertensive (Levey 1998) and hypertension may contribute to the burden of cardiovascular disease in the dialysis population. Depressed patients on PD have been shown to have higher rates of peritonitis (Juergenson 1996). Depression has been associated with increased death for dialysis patients (Hedayati 2010; Palmer 2013b; Weisbord 2014). The risk of hospitalisation is increased in patients with depression (Flythe 2017; Lopes 2002).

Description of the intervention

Depression can be treated by both physical (drugs and electro‐convulsive therapy (ECT)) and psychosocial interventions.

Psychosocial interventions can be defined as those interventions that provide psychological, emotional, or social support without using pharmacological substances. These may include counselling, social group support, cognitive‐behavioural therapy (CBT), relaxation or visualisation techniques, exercise, education, or individual social support including by telephone. Therapies may vary in their mode of delivery, intensity, or methodology, and level of contact with an individual therapist or support worker. Psychosocial interventions may help reduce distressing symptoms, increase coping strategies, increase social connectedness, assist in strategies to address specific disease‐related problems, and decrease anxiety and stress.

How the intervention might work

Several meta‐analysis of psychosocial interventions have found such therapies to be effective treatments for depression in the wider population (Churchill 2001; Dobson 1989; Robinson 1990; Scoggin 1994). In some studies, although participants did not report a specific diagnosis of depression when they were enrolled, psychosocial interventions were effective to prevent depression and impede the progression of the disease (Heshmatifar 2015). Dialysis patients, caregivers, and health professionals have identified depression as a critical outcome for evaluation in nephrology research (Tong 2017); however a previous version of this Cochrane review published in 2005 (Rabindranath 2005) did not identify any randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of psychosocial interventions to treat depression in the dialysis setting. Psychosocial interventions may be especially appropriate for patients on dialysis, since they avoid potential drug interactions and adverse effects of antidepressant medication. Psychosocial interventions are also known to be acceptable to patients and form a core recommendation in guidelines for the treatment of depression in adults (NICE 2018).

Why it is important to do this review

Depression is common for dialysis patients and may increase the substantial burden of symptoms and treatment. Patients, health professional and policy‐makers have identified research on the psychosocial impact of chronic kidney disease (CKD) as a priority (Tong 2015). This is an update of a Cochrane review that was first published in 2005, which identified no relevant studies of psychosocial interventions to treat depression in dialysis patients (Rabindranath 2005). Similarly, a Cochrane review in 2016 of antidepressants for treatment depression in adults with end‐stage kidney disease (ESKD) treated with dialysis included four studies including 170 participants (Palmer 2016). In very low certainty or ungraded evidence, antidepressant therapy had uncertain effects on quality of life (QoL), might reduce depression symptoms and might incur nausea.

Given the priority placed on psychosocial support for dialysis by patients and health professionals, the very low certainty of existing evidence for depression treatment, and the poor outcomes associated with depression in the dialysis setting, our aim was to provide an updated summary of the evidence of the benefits and potential harms of psychosocial interventions among adults with ESKD treated with dialysis.

Objectives

To assess the effect of using psychosocial interventions versus usual care or a second psychosocial intervention for preventing and treating depression in patients with ESKD treated with dialysis.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included RCTs and quasi‐RCTs (e.g. studies in which the method of assignment is based on alternation, date of birth or medical record number) of psychosocial interventions for prevention and treatment of depression among adults treated with long‐term dialysis.

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria

We included participants aged 18 years or above undergoing dialysis (either HD or PD) for ESKD with or without a diagnosis of depression.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded studies evaluating treatment for other psychiatric disorders including bipolar affective disorder.

Types of interventions

We included studies that compared a psychosocial intervention (such as cognitive and behavioural therapies, exercise training, and counselling) versus usual care or a second psychosocial intervention. We excluded studies comparing psychosocial interventions with drugs or ECT.

Types of outcome measures

We did not exclude studies that did not measure or report review outcomes.

We collected outcome data for depression by any measure and at any time point including incidence of major depression, depression (any severity), and depression score at end of treatment (any measure).

Primary outcomes

Depression (any measure)

HRQoL

Secondary outcomes

Anxiety (any measure)

Cognitive function (any measure)

Hospitalisation

Death from any cause

Suicide or suicide attempts

Adherence to dialysis treatment

Withdrawal from dialysis treatment

Withdrawal from trial intervention

Adverse events

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies up to 21 June 2019.The specialised register contains studies identified from the following sources.

Monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

Weekly searches of MEDLINE OVID SP

Handsearching of kidney‐related journals and the proceedings of major kidney and transplant conferences

Searching of the current year of EMBASE OVID SP

Weekly current awareness alerts for selected kidney journals

Searches of the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Studies contained in the Register are identified through searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE based on the scope of Cochrane Kidney and Transplant. Details of search strategies, as well as a list of handsearched journals, conference proceedings and current awareness alerts, are available on the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant website.

See Appendix 1 for search terms used in strategies for this review.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of review articles, relevant studies and clinical practice guidelines.

Letters seeking information about unpublished or incomplete trials to investigators known to be involved in previous studies.

For the original review, the American College of Physicians Database and PsycINFO were also searched.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

For this 2019 update, two authors independently reviewed study titles and abstracts. Full text articles of studies considered potentially relevant were obtained and reviewed for eligibility by both authors. We consulted a third author to resolve discrepancies if necessary. We reassessed eligibility of studies excluded in the last version of the review (Rabindranath 2005) because of changes to the review criteria.

Data extraction and management

For this update, data extraction and assessment of risk of bias was performed by two authors using standardised data extraction forms. Disagreements not resolved by discussion between authors could be referred to a third author. Studies reported in languages other than English were translated before data extraction. Where more than one report of a study was identified, data were extracted from all reports. Where there were discrepancies between reports, data from the primary source were used. Study authors were contacted for additional information about studies.

We extracted the following information:

Methods: type of study design, setting, country, funding sources, time frame, duration of follow‐up

Participants: number of participants randomised to each group, number of analysed participants, inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, age, sex, antidepressant medication

Interventions: details of intervention

Outcomes: all outcomes measured by study authors summary statistics of continuous data (mean, standard deviation (SD) and dichotomous data (number who experienced endpoint and number at risk).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two authors independently assessed methodological reporting using the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins 2011) (see Appendix 2).

We assessed the following:

Was there adequate sequence generation (selection bias)?

Was allocation adequately concealed (selection bias)?

-

Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study (detection bias)?

Participants and personnel (performance bias)

Outcome assessors (detection bias)

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed (attrition bias)?

Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting (reporting bias)?

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous outcomes (hospitalisation, death, suicide or suicide attempts, withdrawal from trial treatment, withdrawal from dialysis, adverse events), results were expressed as risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Continuous data

Where continuous scales of measurement were used to assess the effects of treatment (HRQoL, depression score), we used mean differences (MD) where the studies employed the same outcome measure. Where the studies used different scales to assess a given outcome, we used the standardised mean difference (SMD). We considered SMD of 0.2 a small effect size, SMD 0.5 a medium effect size and SMD 0.8 a large effect size (Cohen 1988).

Change scores and missing standard deviations

We included change scores and missing standard deviations (SD) according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Unit of analysis issues

Cross‐over studies

A primary concern with cross‐over trials is the "carry‐over" effect in which the effect of the intervention treatment influences the participant's response to the subsequent intervention in the second phase of the study. As a consequence, participants entering the second phase of the study may differ systematically from their "baseline" state even after a wash‐out phase. To minimise the carry‐over effect, we only extracted data from the first phase of the study, prior to cross‐over.

Dealing with missing data

Any further information required from the original author was requested by written correspondence and any relevant information obtained was to be included in the review. Evaluation of important numerical data such as screened, randomised patients as well as intention‐to‐treat, as‐treated and per‐protocol population were carefully performed. Attrition rates, for example drop‐outs, losses to follow‐up and withdrawals were investigated. Issues of missing data and imputation methods (for example, last‐observation‐carried‐forward) were critically appraised (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We first assessed the heterogeneity by visual inspection of the forest plot. We then quantified statistical heterogeneity using the I2 statistic, which describes the percentage of total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error (Higgins 2003). A guide to the interpretation of I2 values was as follows.

0% to 40%: might not be important

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

The importance of the observed value of I2 depends on the magnitude and direction of treatment effects and the strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P‐value from the Chi2 test, or a confidence interval for I2) (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting bias may occur when the direction and/or magnitude of a study's results influence a decision to publish the study. Empirical evidence suggests that studies with statistically significant findings are more likely to be submitted and accepted for publication, and may lead to over‐estimation of the true treatment effect. To assess whether studies in our meta‐analyses may be affected by publication bias, we planned to enter data into a funnel plot when a meta‐analysis included the results of at least 10 studies and in the absence of moderate or substantial heterogeneity (Higgins 2011). In this version of the review, there were insufficient data to generate funnel plots.

Data synthesis

Data were summarised using the random‐effects model and the fixed‐effect model was also used to ensure robustness of the model chosen and susceptibility to outliers.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Although subgroup analyses have to be treated with caution, as they are hypothesis‐forming rather than hypothesis‐testing, we considered conducting a priori defined analyses in order to explore whether methodological and clinical differences between the trials may have systematically influenced the differences that were observed in the treatment outcomes.

Sensitivity analysis

We considered performing sensitivity analyses to explore the influence of the following factors on effect size, although in this version of the review, there were insufficient data to generate sensitivity analyses.

Repeating the analysis excluding unpublished studies

Repeating the analysis taking account of risk of bias, as specified

Repeating the analysis excluding any very long or large studies to establish how much they dominate the results

Repeating the analysis excluding studies using the following filters: diagnostic criteria, language of publication, source of funding (industry versus other), or country.

'Summary of findings' tables

We presented the main results of the review in 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables present key information concerning the quality of the evidence, the magnitude of the effects of the interventions examined, and the sum of the available data for the main outcomes (Schunemann 2011a). The 'Summary of findings' tables also include an overall grading of the evidence related to each of the main outcomes using the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach (GRADE 2008; GRADE 2011). The GRADE approach defines the quality of a body of evidence as the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association is close to the true quantity of specific interest. The quality of a body of evidence involves consideration of within‐trial risk of bias (methodological quality), directness of evidence, heterogeneity, precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias (Schunemann 2011b).

We used the GRADE process to assess the certainty of the body of the evidence associated with the following outcomes.

Major depression

Depression score (any measure)

Anxiety

QoL

Withdrawal from dialysis

Withdrawal from intervention

Death (any cause)

We constructed four 'Summary of Findings' tables for the following comparisons in this review.

CBT versus usual care

Counselling versus usual care

Exercise versus usual care

Relaxation techniques versus usual care

Spiritual practice versus usual care

One author completed the tables in consultation with a second author.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

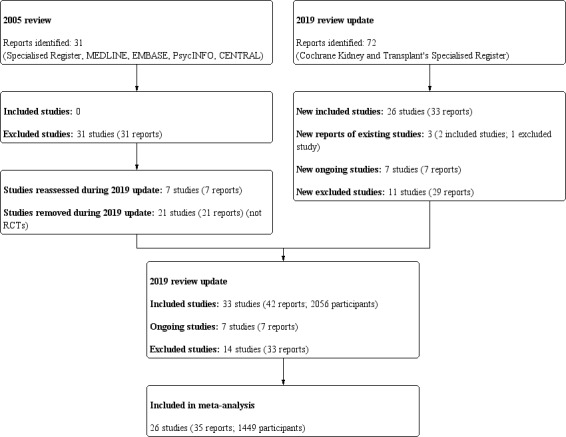

Search results are shown in Figure 1. For this 2019 review update, we screened 72 titles and abstracts. We reclassified seven studies in seven publications from the 2005 review as eligible due to the expanded criteria in this review to include participants without depression at baseline. We removed 21 studies (21 publications) from the 2005 review as they were not RCTs. From the 2019 search update, we identified 26 new studies (33 reports) that met the review eligibility criteria (Characteristics of included studies); 11 studies (29 reports) were and excluded, and there are 7 ongoing studies.

1.

Study flow diagram

Included studies

See Characteristics of included studies.

We included 33 studies in 42 publications. One study (Cukor 2014) was a cross‐over study design in which participants were administered each of the study interventions sequentially without a washout period. One study (Dziubek 2016) was a quasi‐randomised study.

Study design, setting and characteristics

Study duration varied from three weeks to one year. Studies were conducted in fifteen different countries including Brazil (Duarte 2009), Canada (Thomas 2017), Greece (Kouidi 1997; Kouidi 2010; Ouzouni 2009), Indonesia (Sofia 2013), Iran (Babamohamadi 2017; Bahmani 2016; Espahbodi 2015; Heshmatifar 2015; Kargar Jahromi 2016), Jordan (Al Saraireh 2018), Malaysia (Hmwe 2015), Mexico (Lerma 2017), Poland (Bargiel‐Matusiewicz 2011; Bargiel‐Matusiewicz 2011a; Dziubek 2016), Singapore (HED‐SMART 2011), Taiwan (Lii 2007; Tsai 2015), UK (iDiD 2016; Krespi 2009; Vogt 2016), Tunisia (Frih 2017), Turkey (Sertoz 2009), and USA (Beder 1999; Carney 1987; Cukor 2014; Erdley 2014; Frey 1999; Leake 1999; Mathers 1999; Matthews 2001). One study (Thomas 2017) received at least some funding from companies, while 32 studies provided no specific details about funding sources.

Study participants

The 33 studies included 2056 randomised participants treated with HD. The sample size varied from 9 participants (Vogt 2016) to 235 participants (HED‐SMART 2011). One study (Sofia 2013) did not report the number of participants. The mean study age ranged from 36.1 years (Carney 1987) to 73.9 years (Erdley 2014), with a median of 52.4 years.

Interventions

Details of interventions in each study are presented in the Characteristics of included studies and in Table 6.

1. TIDieR framework of interventions descriptions for included studies.

| Study ID | Intervention | Control | Aim | What | How | Who, where, when | Tailoring/modification | How well: planned | How well: actual |

| Al Saraireh 2018 | CBT | Education | To assess the level of depression among patients undergoing HD and to compare the effectiveness of CBT versus psycho education | Traditional CBT sessions protocol was compared with psycho educational therapy | Both groups attended seven sessions of one hour. The control group discussed on education about stress management and relaxation, focusing on optimism, deep breathing and problem‐solving skills | In private rooms within the dialysis units by two expert researchers, for 7 sessions (3 months) | ‐ | All sessions were administered on one‐to‐one basis | 105 completed the study |

| Babamohamadi 2017 | Spiritual practice | Usual care | To examine the effect of the Holy Qur'an recitation (music therapy) on depressive symptoms | Holy Qur'an was recited aloud with the voice of Shateri (a well‐known actor of the Qur'an) | Listened to the Qur'an recitation (adds religious content to the pleasant, adding further to the relaxation, focus on pleasant sounds, and distraction from negative ruminations) using an MP3 player with headphones | Shateri provided the intervention 3 times a week for 20 min each during 1‐month, in the clinic | ‐ | ‐ | 54 completed the study |

| Bahmani 2016 | Counselling | Usual care | To examine a method that considers the needs of patients under special treatment such as dialysis | Combination of treatment including some elements of "existentialism" philosophy and a "cognitive" approach | Discussions on social support, face loneliness, isolation, death, losing the opportunity to job, losing education, emotional difficulties and the pain of treatment | Researcher provided the intervention for 12 sessions of 90 min, for 3 months, in the clinic | ‐ | ‐ | 20 completed the study |

| Bargiel‐Matusiewicz 2011 | Voice recording | Usual care | To assess the influence of a psychological intervention on the cognitive appraisal | Based on the principles of the Ericksonian therapy and used therapeutic metaphors | Listened to a CD (20 min) with a recorded psychological intervention | Twice a day for 3 weeks. Researchers carried out the intervention in a natural environment | ‐ | ‐ | 60 completed the study |

| Bargiel‐Matusiewicz 2011a | Counselling | Usual care | To assess if psychological intervention improve the level of acceptance of illness | Participants attended in meetings | ‐ | Psychologist provided the intervention for 5 weeks | ‐ | ‐ | The number of subject who completed the study was not clear |

| Beder 1999 | Counselling | Usual care | To provide existing dialysis programs with a supported model of service | Basic social support consisted of a psycho‐educational and support components | Providing information on patients' needs and received additional social support component | Renal social workers provided the intervention in the hospital for 3 months | Helping the patients in mobilizing and assessing and accessing additional supports as needed | ‐ | 46 completed the study |

| Carney 1987 | Exercise | Support group | To assess the effect of exercise training on the psychosocial rehabilitation | 5‐min sessions on a stationary bicycle ergometer and fast walking interspersed with 5‐mi rest periods | All patients were provided with bicycle ergometers for home use and jogging 1 to 2 laps | 3 time a week at home for 45 to 60 min for 6 months | ‐ | ‐ | 17 completed the study |

| Cukor 2014 | CBT | Usual care | To test the efficacy of an individual chairside CBT | Standard CBT intervention for depression was adapted for HD patients | At the end of the first period, treatments were inverted | Psychologists provided the intervention in chairside, during dialysis, for 3 months | ‐ | ‐ | 59 completed the study |

| Duarte 2009 | CBT | Usual care | To assess the effectiveness of CBT in ESKD patients with a diagnosis of major depression | Educating patients on several aspects of kidney disease, dialysis, depression | Provided self‐monitoring of mood status; cognitive restructuring; programming pleasant activities; training on social abilities; exercises | Psychologists provided the intervention (1 hour and 30 min) during dialysis, for 3 months | ‐ | Another psychologist checked written records to monitor the intervention | 74 completed the study |

| Dziubek 2016 | Exercise | Exercise | To evaluate the effects of exercise on depression and anxiety, and compared 2 different types of training in dialysis | Endurance and resistance training were performed | Ergonometer group performed short warm‐up, 10 to 15 min of training using a motorized exercise therapy device and 35 to 50 min ride on the cycle ergometer. Resistance group performed strength exercises with weights, balls and Thera Bands and final relaxation | Nephrologist and cardiologist supervised the training performed 3 times a week for 6 months in the clinic | The number of evolutions and load were constant, individually tailored to the patient depending on the tolerance of the exercise | Heart rate, blood pressure and the degree of fatigue were monitored | 28 participants completed the study |

| Erdley 2014 | Counselling | Usual care | To assess the efficacy of problem‐solving therapy in reducing depressive symptoms. | Providing intervention to manage problems and improve individual coping and problem‐solving ability. | Provided orientation to problem solving, evaluating and choosing solutions, and identifying steps to achieve solutions. | Meeting with social workers were provided once weekly in the dialysis unit for 1 hour, for 6 weeks. | ‐ | ‐ | 33 completed the study. |

| Espahbodi 2015 | Education | Usual care | To investigate psychological impacts of psycho education on anxiety and depression | Psycho education sessions | Sessions of anatomy, pathophysiology, variety of treatments, stress management, problem‐solving skills, and muscle relaxation | 3 sessions of one‐hour, in the clinic with a psychiatrist was delivered for 1 month | ‐ | ‐ | 55 completed the study |

| Frey 1999 | Exercise | Usual care | To evaluate the difference in kilocalorie and protein intake in ESKD patients who perform or not perform exercise | Exercise patients cycled on stationary bicycle ergometers | 5 minutes warm‐up and 5 minutes cool down. Cycling periods were followed by gradually increasing tension | Investigator supervised the intervention for 12 weeks | ‐ | ‐ | All participants completed the study |

| Frih 2017 | Spiritual practice | Exercise | To determine whether listening to Holy Qur'an recitation improve the effects of exercise on physiological measures | Resistance training consisted of dynamic exercises. Endurance training consisted of ergo cycle exercise. The intervention group listened to the Holy Qur'an | The Holy Qur'an was recited by the reader Al‐Dosari, who reads with a relaxing and calming voice. The recitation was played through headphones on MP3 | The reader Al‐Dosari recited and participants listened verses 3 times a week during 24 weeks, (20 min), in the clinic | The volume was adjusted according to the patient’s comfort | A Borg score of 5 to 6 for dyspnoea or fatigue was set as a target | All participants completed the study |

| HED‐SMART 2011 | Counselling | Usual care | To determine the efficacy of the intervention on biochemical markers, clinical status, QoL and patient satisfaction | Participants performed the NKF‐NUS self‐management intervention to take control of their condition | 3 main interactive sessions held every two weeks and one booster session Intervention components will include problem solving, overcoming barriers, challenging beliefs, conducting brainstorming sessions, goal setting, and reinforcement. Participants also received an educational booklet | 4 sessions (90 min each) were facilitated by two health care professionals | Used feedback, modelling of problem‐solving strategies through group support and guidance for individual self‐management efforts | Patients were contacted by telephone to assess the progress they were making with their goals | All participants completed the study |

| Heshmatifar 2015 | Relaxation | Usual care | To assess the efficacy of Benson technique to improve depressive symptoms | The training sessions included discussions about relaxation. The participants were asked to perform the relaxation exercises | Participants performed exercises for 20 minutes. The training method, an educational pamphlet and a CD were handed to subjects to perform the exercises | Researcher provided the intervention in the clinic, for 1 month | ‐ | Subjects’ compliance was ensured through text messages | All participants completed the study |

| Hmwe 2015 | Acupressure | Usual care | To evaluate the effects of acupressure on depression, stress, anxiety and general psychological distress | Acupoints for depression, anxiety, and stress was based on the concepts of Chinese medicine | Acupressure is performed by applying consistent fingertip pressure on selected acupoints with rotational movements | Investigator provided acupressure 3 times/ week over 4 weeks, in the clinic | ‐ | A supervisor monitored to ensure that the intervention was performed as the protocol declared | 102 the study. 108 were analysed (intention to treat) |

| iDiD 2016 | Telephone support + CBT | CBT | To explore adherence and examine the efficacy of online CBT sessions and therapist support calls | All patients had access to the iDiD online intervention Patients in the supported arm received three 30 min telephone calls | iDiD sessions were designed to last approximately 60 min. iPads were available at dialysis units. The researcher guided the patient to the most relevant components of sessions | Telephone support was delivered by a trained psychological well‐being researcher | For 6 patients was generate an email address and provide brief Internet education, thus these patients received a higher degree of technical support and face to face contact | Patients received reminders. Support calls were audio recorded for supervision and checks | 23 completed the study |

| Kargar Jahromi 2016 | Telephone support | Usual care | To evaluate the effect of nurse‐led telephone follow‐up on depression, anxiety and stress | The intervention group received telephone follow‐up after dialysis and conventional treatment | Key subjects: communication, cognition/development, breathing/circulation, nutrition, elimination, sleep, tissue, pain, sexuality, activity and psychosocial/spirituality/culture | Researchers provided every session (30 minutes), for a month | ‐ | The content of the call followed a script to ensure consistency | 54 completed the study |

| Kouidi 1997 | Exercise | Usual care | To assess the psychosocial effects of exercise training. | The intervention was the exercise training rehabilitation program. | The telemetric spirometer assessed the maximal oxygen consumption during the performance. | Psychologist and trainer supervised the exercise, for 6 months | The intensity and duration of the exercise sessions was gradually increased. | ‐ | 31 completed the study. |

| Kouidi 2010 | Exercise | Usual care | To investigate the effects of exercise on emotional parameters in HD patients | The intervention was the exercise training rehabilitation program | 5 min warm‐up, 30 to 60 min of cycling, 20 min strengthening time followed by a 5 min cooling off | 3 times a week during the first 2 hours of HD session | ‐ | ‐ | 38 completed the study |

| Krespi 2009 | Relaxation |

Control 1 Voice control Control 2 Usual care |

To investigate the effects of relaxation | The experimental group received specific visual imagery (using metaphors), delivered by audiotapes | Each tape lasted for 25 minutes, relaxation and imagery took 20 minutes for the techniques and 5 minutes for the specific imaging technique | Researchers provided the intervention 3 to 4 times/week for 6 weeks, during HD | ‐ | The procedures support patients and answer questions | 103 completed the study |

| Leake 1999 | Motivational interviewing |

Control 1 Motivational interviewing Control 2 Video recording |

To evaluate the therapeutic benefits of strategic self‐presentation | Patients participated in a videotaped interview where they portrayed their coping strategies | Patients were asked to provide candid testimonies about their own difficulties on problems with chronic illness | The researchers provided the interview for 1 month | ‐ | Patients were given the opportunity to revise the video tape | 41 completed the study |

| Lerma 2017 | CBT | Usual care | To reduce mild and moderate depression and anxiety symptoms in patients | Intervention consisted of positive self‐reinforcement, deep breathing, muscle relaxation, and cognitive restructuring | All components of the programme were adapted to the clinical context of patients with ESRD using images, examples, words, exercises, and everyday scenarios that were relevant to them | The therapist provided the intervention in the clinic during 5 weekly sessions that lasted 2 hours each | Patients who were identified as having severe depression symptoms (BDI > 29 points) were referred for appropriate psychiatric evaluation and care | The therapist recorded comments and received feedback from an expert | 49 completed the study |

| Lii 2007 | CBT | Usual care | To investigate the effects of intervention on depression and QoL | The treatment helped participants to evaluate problem and solve irrational beliefs | Self‐management of depression; restructuring beliefs; stress management; and health education | Nurses provided the intervention in the clinic, once a week, for 2 hours | ‐ | ‐ | 48 completed the study |

| Mathers 1999 | Education | Usual care | To determine if the psychosocial education sessions had an effect on the adaptation level | 7 audiotapes and a companion text module, provided information | Each module consisted in several questions to help participants focus on the topic of the day | Investigators provided 7 sessions, 2 days a week (20 min each), for 4.5 weeks | The investigator was available to answer any questions | ‐ | 6 completed the study |

| Matthews 2001 | Spiritual practice |

Control 1 Visualisation Control 2 Usual care |

To explore the effect of intercessory prayer, positive visualisation, and outcome expectancy | Christian prayer group and transpersonal (nonreligious) positive visualisation group improved illness | In the intervention group there were 6 intercessors who preyed. In the positive visualisation group, 6 psychology interns focused on patients' problems, using audiotapes | The prayers and the visualisation process took 5 to 15 min/5 days, for 6 weeks | ‐ | An individual checked if the intercessory prayer was performed | The number of subject who completed vary (absent during data collection) |

| Ouzouni 2009 | Exercise | Usual care | To assess the effects of intradialytic exercise training on HRQoL | Patients in the exercise group followed an exercise rehabilitation programme | Each exercise session included 30 min of cycling and 30 min of strengthening and flexibility exercises (20 min cycling at desired workload and 5 min cool‐down) | Physiologists provided the exercised 3 times weekly (90 min each), per 10 months (in the centre) | For the cycling exercise specific devices, which were adjusted to each patient’s bed, were used | Their cardiac rhythm and blood pressure were monitored continuously | 33 completed the study |

| Sertoz 2009 | Social activity | Usual care | To investigate the impact of social activity on anxiety, depression, self‐esteem and QoL | Patients were engaged in a play. The play chosen was one by Tuncay Cucenoglu (drama organisation) | “The Painter”, by displaying the social structure and diversity of ideas, maintains the audience’s curiosity. The control group participated as the audience | At the baseline and after 4 months | ‐ | ‐ | The number of subject who completed the study was not clear |

| Sofia 2013 | Relaxation | Control | To determine the effect of Latihan Pasrah Diri (LPD) on QoL in HD patients with depression | The intervention group received LPD | LPD was a method combining relaxation and remembrance with a focus on breathing exercises and words contained in the "zirk" (relaxation and repetitive prayer) | 21 days | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Thomas 2017 | Meditation | Usual care | To determine whether the intervention reduced depression and anxiety symptoms | Chairside meditative practices were performed 4 meditation techniques drawn from mindfulness‐based. |

Cognitive therapy were practiced in alternating fashion, on the basis of patient preference. In these techniques, the participant is guided to direct their attention toward specific elements of their experience | Interventionists performed 3 times/week, during HD, lasting 10 to 15 min, for 8 weeks | ‐ | Patients were encouraged to practice the techniques at home, but did not have formal logs | 32 completed the study |

| Tsai 2015 | Relaxation | Control | To examine the efficacy of a nurse‐led, in reducing depressive symptoms and improving sleep | The dialysis nurse administered the audio device–guided breathing training in a quiet room | Patients listened to pre‐recorded instructions on breathing technique and then practiced the breathing exercise | A trained nurse provided the intervention in the clinic: 8 sessions, twice weekly for 4 weeks | Each patient received an individual coaching session | The nurse supervised to ensure that participants performed them correctly | 57 completed the study |

| Vogt 2016 | Counselling | Usual care | To examine the feasibility and appropriateness of the intervention | Participants received Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) | The intervention was based on a self‐help manual with weekly telephone support | 6 weeks. | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

CBT ‐ cognitive behavioural therapy; ESKD ‐ end‐stage kidney disease; HD ‐ haemodialysis

Interventions included acupressure (Hmwe 2015) (108 participants), CBT in five studies (Al Saraireh 2018; Cukor 2014; Duarte 2009; Lerma 2017; Lii 2007) (405 participants), counselling in six studies (Bahmani 2016; Bargiel‐Matusiewicz 2011a; Beder 1999; Erdley 2014; HED‐SMART 2011; Vogt 2016) (527 participants), education in two studies (Espahbodi 2015; Mathers 1999) (70 participants), exercise in six studies (Carney 1987; Dziubek 2016; Frey 1999; Kouidi 1997; Kouidi 2010; Ouzouni 2009) (190 participants), meditation in Thomas 2017 (41 participants), motivational interviewing in Leake 1999 (42 participants), relaxation in four studies (Heshmatifar 2015; Krespi 2009; Sofia 2013; Tsai 2015) (287 participants), social activity in Sertoz 2009 (31 participants), spiritual practice in three studies (Babamohamadi 2017; Frih 2017; Matthews 2001) (208 participants), telephone support in Kargar Jahromi 2016 (60 participants), telephone support and CBT in iDiD 2016 (25 participants) and audio‐recording of a psychological intervention in Bargiel‐Matusiewicz 2011 (62 participants).

Three studies reported three treatment groups. In Leake 1999, motivational interviewing was compared with another motivational interviewing or video recording. In Krespi 2009, relaxation was compared with voice control or usual care. Matthews 2001 compared spiritual practice with visualisation or usual care.

The methods for implementation, tailoring, and measurement of adherence of interventions are provided in Table 6 using a TIDIeR [Template for Intervention Description and Replication] checklist (Hoffmann 2014).

Excluded studies

We excluded 14 studies (33 reports) as the intervention or treatment comparison were judged as not eligible, the study did not include the population of interest, or the study was not an RCT. See Characteristics of excluded studies.

Ongoing studies

Our search identified seven studies that have yet to been completed (DOHP 2016; NCT02011139; NCT03162770; NCT03330938; NCT03406845; van der Borg 2016; WICKD 2019). Study comparisons include:

Structured information/workbook, psychosocial and educational supports compared to skills building to usual care (DOHP 2016)

CBT for 12 weeks compared to usual care (NCT02011139)

Meditation for 8 weeks compared to usual care (NCT03162770)

CBT together with resilience training for eight weeks compared to CBT alone (NCT03330938)

Meditation for eight weeks compared to a program of health education, diet, music, exercise, and positive life changes (NCT03406845)

Counselling by a social worker for 16 weeks compared to usual care (van der Borg 2016)

Early treatment with motivational care planning compared to delayed treatment with motivational care planning and usual care (WICKD 2019).

Risk of bias in included studies

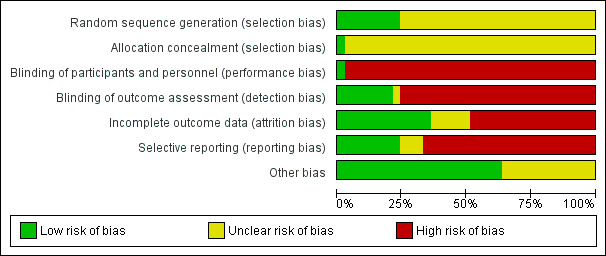

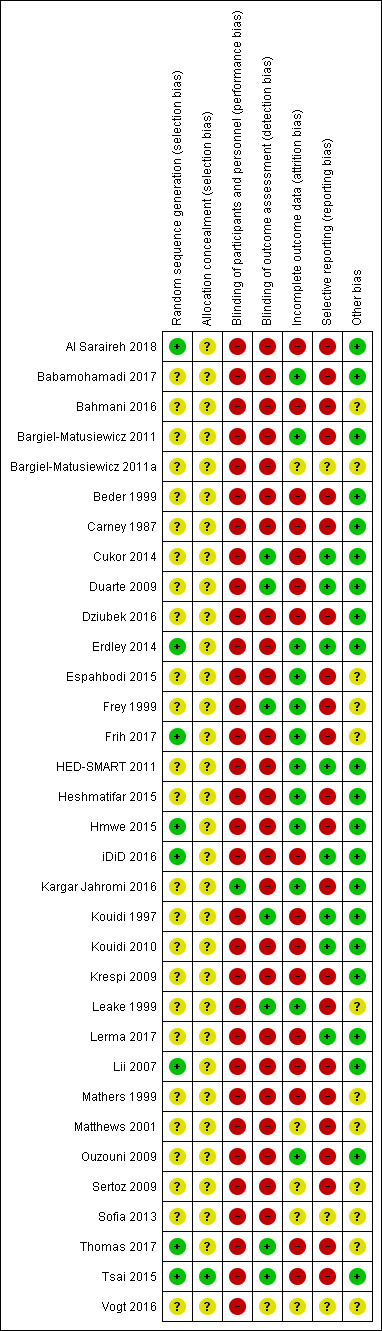

The risk of bias for studies overall are summarised in Figure 2 and the risk of bias in each individual study is reported in Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Methods for generating the random sequence were deemed to be at low risk of bias in eight studies (Al Saraireh 2018; Erdley 2014; Frih 2017; Hmwe 2015; iDiD 2016; Lii 2007; Thomas 2017; Tsai 2015). In the remaining 25 studies, the method for generating the random sequence was unclear.

Allocation concealment was adjudicated as low risk of bias in one study (Tsai 2015). The risk of bias for allocation concealment was unclear in the remaining 32 studies.

Blinding

One study was blinded and considered to be at low risk of bias for performance bias (Kargar Jahromi 2016). The remaining 32 studies were not blinded and were considered at high risk of performance bias.

Blinding of outcome assessment was assessed to be at low risk in seven studies (Cukor 2014; Duarte 2009; Frey 1999; Kouidi 1997; Leake 1999; Thomas 2017; Tsai 2015). The risk of bias for blinding of outcome assessment was unclear in one study (Vogt 2016). The remaining 25 studies were considered at high risk of detection bias.

Incomplete outcome data

Twelve studies met criteria for low risk of attrition bias (Babamohamadi 2017; Bargiel‐Matusiewicz 2011; Erdley 2014; Espahbodi 2015; Frey 1999; Frih 2017; HED‐SMART 2011; Heshmatifar 2015; Hmwe 2015; Kargar Jahromi 2016; Leake 1999; Ouzouni 2009). Sixteen studies were considered at high risk of attrition bias when there was differential loss to follow‐up between treatment groups and high attrition rates (Al Saraireh 2018; Bahmani 2016; Beder 1999; Carney 1987; Cukor 2014; Duarte 2009; Dziubek 2016; iDiD 2016; Kouidi 1997; Kouidi 2010; Krespi 2009; Lerma 2017; Lii 2007; Mathers 1999; Thomas 2017; Tsai 2015). In the remaining five studies, attrition bias was considered unclear. Loss to follow‐up was commonly due to death, hospitalisation, transplantation, withdrawal of consent, or medical problems.

Selective reporting

Eight studies reported expected and clinically‐relevant outcomes and were deemed to be at low risk of bias (Cukor 2014; Duarte 2009; Erdley 2014; iDiD 2016; HED‐SMART 2011; Kouidi 1997; Kouidi 2010; Lerma 2017). The risk of bias for reporting bias was unclear in three studies (Bargiel‐Matusiewicz 2011a; Sofia 2013; Vogt 2016). The remaining 22 studies did not report patient‐centred outcomes of life participation, fatigue, dialysis withdrawal, adverse events, or death.

Other potential sources of bias

Twenty‐one studies appeared to be free from other sources of bias (Al Saraireh 2018; Babamohamadi 2017; Bargiel‐Matusiewicz 2011; Beder 1999; Carney 1987; Cukor 2014; Duarte 2009; Dziubek 2016; Erdley 2014; HED‐SMART 2011; Heshmatifar 2015; Hmwe 2015; iDiD 2016; Kargar Jahromi 2016; Kouidi 1997; Kouidi 2010; Krespi 2009; Lerma 2017; Lii 2007; Ouzouni 2009; Tsai 2015). It was unclear whether the remaining 12 studies had other sources of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Cognitive‐behavioural therapy versus usual care.

| Cognitive‐behavioural therapy (CBT) versus with usual care for depression in people treated with dialysis | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with ESKD Settings: dialysis Intervention: CBT Comparison: usual care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Usual care | CBT | |||||

|

Major depression Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) (median follow‐up: 39.6 weeks) |

Not estimable1 | Not estimable | Not estimable | Insufficient data observations | Not estimable | Studies were not designed to measure effects of Cognitive behavioural therapy on major depression |

|

Depression (any severity, including mild, moderate and severe depression) Investigators measured depression using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). A higher score is indicative of more depressive symptoms. (median follow‐up: 17.7 weeks) |

The mean Beck Depression Inventory ranged across control groups from 14.5 to 21.39 | The mean Beck Depression Inventory score in the intervention groups was 6.10 lower (95% CI ‐8.63 to ‐3.57) |

MD ‐6.10 (95% CI ‐8.63 to ‐3.57) |

230 (4) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate 2 | Cognitive behavioural therapy probably decreases depressive symptoms |

|

Health‐related quality of life Investigators measured health‐related quality of life using different instruments: Quality of Life Scale (QoL) and HRQoL Short Form‐36, Kidney Disease and Quality of Life‐Short Form (KDQOL‐SF‐36) (median follow‐up: 17.7 weeks). A higher score is indicative of higher perceived of QoL. |

The mean quality of life score ranged across control groups from 40.46 to 110.6 | The mean QoL score in the intervention groups was 0.51 standard deviations higher (95% CI 0.19 to 0.83) |

SMD 0.51 (95% CI 0.19 to 0.83) |

230 (4) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate 2 | As a rule of thumb, 0.2 SMD represents a small effect size, 0.5 SMD a moderate effect size and 0.8 SMD a large effect size. Cognitive behavioural therapy probably moderately improves health‐related quality of life |

|

Anxiety Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (median follow‐up: 9 weeks) |

Not estimable3 | Not estimable | Not estimable | Insufficient data observations | Not estimable. | Studies were not designed to measure effects of cognitive behavioural therapy on anxiety |

| Withdrawal from dialysis | No data observations | Not estimable | No observations | Insufficient data observations | Not estimable. | Studies were not designed to measure effects of cognitive behavioural therapy on withdrawal from dialysis |

| Withdrawal from intervention | No data observations | Not estimable | No observations | Insufficient data observations | Not estimable. | Studies were not designed to measure effects of cognitive behavioural therapy on withdrawal from intervention |

|

Death (any cause) (median follow‐up: 24.3 weeks) |

13.8 per 1000 | ‐1.2 per 1000 (95% CI 4.83 to 47.61) | RR 1.09 (95% CI 0.35 to 3.45) | 145 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low 4, 5 | It is uncertain whether CBT makes any difference to death (any cause) |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ESKD: end‐stage kidney disease; CI: Confidence interval; MD: mean difference; SMD: standardised mean difference; RR: Risk Ratio; HRQoL: health‐related quality of life | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 The estimated risk of major depression was not estimable as a single study reported this outcome.

2 All studies had unclear risks of bias for allocation concealment and high risk of blinding of participants or investigators. Two studies (Cukor 2014; Duarte 2009) reported low risk methods for blinding of outcome assessment.

3 The estimated risk of anxiety was not estimable as a single study reported this outcome.

4 All studies had high or unclear risks of bias for allocation concealment and blinding of participants or investigators. One out of two studies reported low risk methods for blinding of outcome assessment.

5 The certainty in the evidence was downgraded due to imprecision in the treatment estimates, consistent with benefit or harm.

Summary of findings 2. Counselling versus usual care.

| Counselling versus usual care for depressive outcomes in people treated with dialysis | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with ESKD Settings: dialysis Intervention: counselling1 Comparison: usual care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Usual care | Counselling | |||||

| Major depression | No data observations | Not estimable | No observations. | Insufficient data observations | Not estimable | Studies were not designed to measure effects of counselling on major depression |

|

Depression (any severity, including mild, moderate and severe depression) Investigators measured depression using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). A higher score is indicative of more depressive symptoms. (median follow‐up: 13.2 weeks) |

The mean depression score ranged across control groups from ‐2.43 to 18.54 | The mean depression score in the intervention groups was 3.84 lower (95% CI ‐6.14 to ‐1.53) |

MD ‐3.84 (95% CI ‐6.14 to ‐1.53) |

99 (3) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low 2,3 | Counselling may decrease depressive symptoms |

|

HRQoL Kidney Disease Quality of Life (KDQOL‐36) (median follow‐up: 6 weeks) |

Not estimable4 | Not estimable | Not estimable | Insufficient data observations | Not estimable | Studies were not designed to measure effects of counselling on health related quality of life |

| Anxiety | No data observations | Not estimable | No observations | Insufficient data observations | Not estimable | Studies were not designed to measure effects of counselling on anxiety |

| Withdrawal from dialysis | No data observations | Not estimable | No observations | Insufficient data observations | Not estimable | Studies were not designed to measure effects of counselling on withdrawal from dialysis |

|

Withdrawal from intervention (median follow‐up: 6 weeks) |

Not estimable5 | Not estimable | Not estimable | Insufficient data observations | Not estimable | Studies were not designed to measure effects of counselling on withdrawal from intervention |

|

Death (any cause) (median follow‐up: 22.8 weeks) |

2.5 per 1000 | ‐1.7 per 1000 (95% CI 0.8 to 22.03) | RR 1.69 (95% CI 0.32 to 8.81) | 270 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low 2,6 | It is uncertain whether counselling makes any difference to death |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ESKD: end‐stage kidney disease; CI: Confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RR: Risk Ratio; HRQoL: health‐related quality of life | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Counselling included existentialism philosophy and cognitive approach, counselling component, problem‐solving therapy and NKF‐NUS self‐management intervention.

2 All studies had high or unclear risks of bias for allocation concealment, blinding of participants or investigators, and blinding of outcome assessment.

3 The certainty in the evidence was downgraded due to imprecision in the treatment estimates for the limited number of participants, according with Optimal Information Size (OIS).

4 The estimated risk of quality of life was not estimable as a single study reported this outcome.

5 The estimated risk of withdrawal from intervention was not estimable as a single study reported this outcome.

6The certainty in the evidence was downgraded due to imprecision in the treatment estimates, consistent with benefit or harm.

Summary of findings 3. Exercise versus usual care.

| Exercise versus usual care for depression in people treated with dialysis | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with ESKD Settings: dialysis Intervention: exercise Comparison: usual care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Usual care | Exercise | |||||

|

Major depression (median follow‐up: 44 weeks) |

86.02 per 1000 | 45.59 per 1000 (95% CI 23.23 to 69.68) |

RR 0.47 (95% CI 0.27 to 0.81) |

108 (3) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low 1,2 | Exercise may decrease risk of major depression |

|

Depression (any severity, including mild, moderate and severe depression) Investigators measured depression using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). A higher score is indicative of more depressive symptoms (median follow‐up: 44 weeks) |

The mean depression score ranged across control groups from 19.4 to22.1 | The mean depression score in the intervention groups was 7.61 lower (95% CI ‐9.59 to ‐5.63) |

MD ‐7.61 (95% CI ‐9.59 to ‐5.63) |

108 (3) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate 1 | Exercise probably decreases depressive symptoms |

|

HRQoL Investigators measured health related quality of life using the Quality of Life Index (QLI). A higher score is indicative of higher perceived of QoL (median follow‐up: 35.2 weeks) |

The mean QoL score ranged across control groups from 5.6 to 6.3 | The mean QoL score in the intervention groups was 3.06 higher (95% CI 2.29 to 3.83) |

MD 3.06 (95% CI 2.29 to 3.83) |

64 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low 1,3 | Exercise may improve HRQoL |

|

Anxiety Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (median follow‐up: 52.1 weeks) |

Not estimable4 | Not estimable | Not estimable | Insufficient data observations | Not estimable | Studies were not designed to measure effects of exercise on anxiety |

| Withdrawal from dialysis | No data observations | Not estimable | No observations | Insufficient data observations | Not estimable | Studies were not designed to measure effects of exercise on withdrawal from dialysis |

| Withdrawal from intervention | No data observations | Not estimable | No observations | Insufficient data observations | Not estimable | Studies were not designed to measure effects of exercise on withdrawal from intervention |

| Death (any cause) | No data observations | Not estimable | No observations | Insufficient data observations | Not estimable | Studies were not designed to measure effects of exercise on death |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ESKD: end‐stage kidney disease; CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio; MD: mean difference; HRQoL: health‐related quality of life | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 All studies had high or unclear risks of bias for allocation concealment and blinding of participants or investigators. One study out of four reported low risk methods for blinding of outcome assessment.

2 There was moderate heterogeneity in the findings of available studies.

3 The certainty in the evidence was downgraded due to imprecision in the treatment estimates for the limited number of participants, according with Optimal Information Size (OIS).

4 The estimated risk of anxiety was not estimable as a single study reported this outcome.

Summary of findings 4. Relaxation techniques versus usual care.

| Relaxation techniques versus usual care for depression in people treated with dialysis | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with ESKD Settings: dialysis Intervention: relaxation techniques1 Comparison: usual care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Usual care | Relaxation techniques | |||||

| Major depression | No data observations | Not estimable | No observations | Insufficient data observations | Not estimable | Studies were not designed to measure effects of relaxation techniques on major depression |

|

Depression (any severity, including mild, moderate and severe depression) Investigators measured depression using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). A higher score is indicative of more depressive symptoms. (median follow‐up: 4.2 weeks) |

The mean depression score ranged across control groups from 9.56 to 30.83 | The mean depression score in the intervention group was 5.77 lower (95% CI ‐8.76 to ‐2.78) |

MD ‐5.77 (95% CI ‐8.76 to ‐2.78) |

122 (2) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate 2 | Relaxation techniques probably decrease depressive symptoms |

|

HRQoL Investigators measured health‐related quality of life using the Health Status Questionnaire Short Form (SF‐36) (median follow‐up: 6 weeks) |

Not estimable3 | Not estimable | No observations | Insufficient data observations | Not estimable | Studies were not designed to measure effects of relaxation techniques on HRQoL |

| Anxiety | No data observations | Not estimable | No observations | Insufficient data observations | Not estimable | Studies were not designed to measure effects of relaxation techniques on anxiety |

| Withdrawal from dialysis | No data observations | Not estimable | No observations | Insufficient data observations | Not estimable | Studies were not designed to measure effects of relaxation techniques on withdrawal from dialysis |

| Withdrawal from intervention | No data observations | Not estimable | No observations | Insufficient data observations | Not estimable | Studies were not designed to measure effects of relaxation techniques on withdrawal from intervention |

| Death (any cause) | No data observations | Not estimable | No observations | Insufficient data observations | Not estimable | Studies were not designed to measure effects of relaxation techniques death |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ESKD: end‐stage kidney disease; CI: Confidence interval; MD: mean difference; HRQoL: health‐related quality of life | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Relaxation techniques included Benson relaxation technique and nurse‐led breathing training.

2 Studies had high or unclear risks of bias for allocation concealment, blinding of participants or investigators, and blinding of outcome assessment.

3 Treatment effects on HRQoL was not estimable as a single study reported this outcome.

Summary of findings 5. Spiritual practice versus usual care.

| Spiritual practice versus usual care for depression in people treated with dialysis | ||||||

|

Patient or population: people with ESKD Settings: dialysis Intervention: spiritual practice1 Comparison: usual care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Usual care | Spiritual practice | |||||

| Major depression | No data observations | Not estimable | No observations | Insufficient data observations | Not estimable | Studies were not designed to measure effects of spiritual practice on major depression |

|

Depression (any severity, including mild, moderate and severe depression) Investigators measured depression using different instruments: Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI). A higher score is indicative of more depressive symptoms. (median follow‐up: 5.2 weeks) |

The mean depression score ranged across control groups from 31.6 to 53.53 | The mean depression score in the intervention groups was 1.00 standard deviations lower (95% CI ‐3.52 to 1.53) |

SMD ‐1.00 (95% CI ‐3.52 to 1.53) |

116 (2) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 2,3,4 | As a rule of thumb, 0.2 SMD represents a small effect size, 0.5 SMD a moderate effect size and 0.8 SMD a large effect size. As SMD is ‐1.00, it is very uncertain whether spiritual practice makes any difference to depressive symptoms |

|

Health‐related quality of life Health Status Questionnaire Short Form (SF‐36) (median follow‐up: 6 weeks) |

Not estimable5 | Not estimable | Not estimable | Insufficient data observations | Not estimable | Studies were not designed to measure effects of spiritual practice on quality of life |

|

Anxiety Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) (median follow‐up: 6 weeks) |

Not estimable6 | Not estimable | Not estimable | Insufficient data observations | Not estimable | Studies were not designed to measure effects of spiritual practice on anxiety |

| Withdrawal from dialysis | No data observations | Not estimable | No observations | Insufficient data observations | Not estimable | Studies were not designed to measure effects of spiritual practice on withdrawal from dialysis |

| Withdrawal from intervention | No data observations | Not estimable | No observations | Insufficient data observations | Not estimable | Studies were not designed to measure effects of spiritual practice on withdrawal from intervention |

| Death (any cause) | No data observations | Not estimable | No observations | Insufficient data observations | Not estimable | Studies were not designed to measure effects of spiritual practice on death |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ESKD: end‐stage kidney disease; CI: Confidence interval; SMD: standardised mean difference; HRQoL: health‐related quality of life | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Spiritual practice included Holy Qur'an recitation and Christian prayer.

2 All studies had high or unclear risks of bias for allocation concealment, blinding of participants or investigators, and blinding of outcome assessment.

3 There was substantial heterogeneity in the findings of available studies (two downgrades).

4 The certainty in the evidence was downgraded due to imprecision in the treatment estimates, consistent with benefit or harm.

5 The estimated risk of anxiety was not estimable as a single study reported this outcome.

6 The estimated risk of quality of life was not estimable as a single study reported this outcome.

See: Table 1 CBT versus to usual care; Table 2 Counselling versus usual care; Table 3 Exercise versus usual care; Table 4 Relaxation techniques versus usual care; Table 5 Spiritual practice versus usual care.

Acupressure versus usual care

Hmwe 2015 reported outcome measures for acupressure compared to usual care for four weeks. Depression was assessed as a continuous outcome either as major (or severe) depression and depression (end of treatment), reported as a score. Since the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) score showed that all participants reported depressive symptoms at the baseline, the intervention was delivered to treat depression. The study measured major depression and HRQoL using the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ), and depression, anxiety and stress scores using DASS.

Hmwe 2015 (108 participants) reported no differences between acupressure and usual care for major depression (Analysis 1.1: GHQ score MD ‐0.89, 95% CI ‐2.42 to 0.64), depression (Analysis 1.2: DASS score MD ‐0.93, 95% CI ‐3.95 to 2.09), anxiety (Analysis 1.4: DASS score MD 0.23, 95% CI ‐2.21 to 2.67), stress (Analysis 1.5: DASS score MD ‐1.48, 95% CI ‐4.32 to 1.36), withdrawal from treatment (Analysis 1.6: RR 7.00, 95% CI 0.37 to 132.35), and hospitalisation (Analysis 1.7: RR 3.00, 95% CI 0.12 to 72.05). Acupuncture may improve HRQoL (Analysis 1.3: GHQ score MD ‐5.00, 95% CI ‐9.59 to ‐0.41). Adverse events of acupressure were rarely reported (Table 7).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupressure versus usual care, Outcome 1 Major depression.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupressure versus usual care, Outcome 2 Depression.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupressure versus usual care, Outcome 4 Anxiety.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupressure versus usual care, Outcome 5 Stress.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupressure versus usual care, Outcome 6 Withdrawal from intervention.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupressure versus usual care, Outcome 7 Hospitalisation.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupressure versus usual care, Outcome 3 Health‐related quality of life.

2. Table of studies reporting adverse events.

| Study ID | Intervention | Control | Adverse events in the intervention arm | Adverse events in the control arm | Comments |

| HED‐SMART 2011 | Counselling | Usual care | Adverse events were reported for the overall population | Adverse events were reported for the overall population | Quote: "Four participants died of cardiovascular causes during the course of the study (2 from each study arm). No other adverse events were reported." |