Abstract

Objectives

The purpose of this study is to estimate the prevalence of comorbidities among people with osteoarthritis (OA) using administrative health data.

Design

Retrospective cohort analysis.

Setting

All residents in the province of Alberta, Canada registered with the Alberta Health Care Insurance Plan population registry.

Participants

497 362 people with OA as defined by ‘having at least one OA-related hospitalization, or at least two OA-related physician visits or two ambulatory care visits within two years’.

Primary outcome measures

We selected eight comorbidities based on literature review, clinical consultation and the availability of validated case definitions to estimate their frequencies at the time of diagnosis of OA. Sex-stratified age-standardised prevalence rates per 1000 population of eight clinically relevant comorbidities were calculated using direct standardisation with 95% CIs. We applied χ2 tests of independence with a Bonferroni correction to compare the percentage of comorbid conditions in each age group.

Results

54.6% (n=2 71 794) of people meeting the OA case definition had at least one of the eight selected comorbidities. Females had a significantly higher rate of comorbidities compared with males (standardised rates ratio=1.26, 95% CI 1.25 to 1.28). Depression, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and hypertension were the most prevalent in both females and males after age-standardisation, with 40% of all cases having any combination of these comorbidities. We observed a significant difference in the percentage of comorbidities among age groups, illustrated by the youngest age group (<45 years) having the highest percentage of cases with depression (24.6%), compared with a frequency of 16.1% in those >65 years.

Conclusions

Our findings highlight the high frequency of comorbidity in people with OA, with depression having the highest age-standardised prevalence rate. Comorbidities differentially affect females, and vary by age. These factors should inform healthcare programme and delivery.

Keywords: osteoarthritis, comorbidity, depression, hypertension, COPD, administrative health data

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Strong methodological approach to identify cases of osteoarthritis (OA) with a validated case definition using five linked population-based administrative databases.

However, case identification based on administrative data may result in underreporting of cases and comorbidities.

The age-standardised prevalence of eight comorbidities, selected on their clinical relevance and the availability of validated case definitions for administrative health data, was estimated among people with OA.

We limited our analysis to eight comorbidities of clinical relevance.

We stratified the analysis by sex and by age cohorts.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common form of arthritis, affecting 1 in 8 (13%) Canadians and representing a major cause of pain and disability in society.1 2 OA affects people of all ages, but is more prevalent among females and older age groups.3 4 Due to an ageing population and an increase in obesity, the prevalence of OA is expected to continue to rise, predicted to affect one in four Canadians by 2040.5 6 The high prevalence of OA in Canada has a substantial impact on quality of life and healthcare costs to individuals and healthcare systems. Quality of life was measured to be 10%–25% lower among people with OA relative to the general population7 with an associated economic burden of $C33 billion (direct and indirect costs) in Canada in 2011.3 The annual cost per individual with OA has been estimated to be two to three times higher compared with people without OA,7 and are associated with more physician visits and hospitalisations.8

More recently, the characterisation of comorbidities among people with OA has been explored due to the potential effect of comorbidities on routine clinical practice, clinical practice guidelines, healthcare utilisation and costs.9 10 In people with OA over the age of 50 years in England, the presence of comorbidities resulted in increased physical disability compared with those without OA, with the influence of comorbidities greater than that expected for OA alone or for each comorbidity in isolation.4 Knowledge of the prevalence of comorbidities in people with OA raises important considerations for optimal OA treatment and management, to reduce pain and physical disability, enhance the quality of life and decrease the burden of OA. Comorbidities add complexity to the management of patients with OA to provide patient-centred care, ensure appropriate management recommendations for healthcare programme and delivery.

The purpose of this study is to estimate the prevalence of comorbidities at time of diagnosis among people with OA in the province of Alberta, Canada, using administrative health data. Our study fills the gap in knowledge regarding the patterns and burden of comorbidities in people with OA, particularly with regard to the link between OA and comorbidities associated with age. In addition, our study is unique in that we examine all of the commonly reported comorbidities simultaneously in a single study. This information is useful to consider in clinical practice guidelines and to assess the potential impact of comorbidities for clinical practice.

Materials and methods

Data sources

We used five linked Alberta, Canada provincial administrative databases between 1 April 1994 and 31 March 2013 to identify individuals with OA who accessed healthcare services paid for by the provincial healthcare insurance plan, previously described elsewhere in detail.6 These databases included the Alberta Health Care Insurance Plan (AHCIP) population registry, the Discharge Abstract Database (DAD), the Physician Claims Database (claims), the Ambulatory Care Classification System (ACCS) and the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System (NACRS).

AHCIP population registry captures individual level demographic data on all insured persons as of the last day of each fiscal year (31 March). All Albertans who are included in the AHCIP have a unique, 9-digit personal health number, which is used when accessing healthcare services, and served to link datasets prior to deidentification. Members of the Armed Forces and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, federal penitentiary inmates and Albertans who have opted out of the AHCIP are excluded.

DAD captures admission and inpatient care data for all hospitalised patients, including diagnostic codes, interventions, patient age and sex, and administrative information. Among 25 DAD diagnostic code fields extracted from the hospital record, OA-related records were identified as those with the first 3 digits 715 or M15 to M19 based on the ninth and tenth revisions of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes, respectively.

Claims captures OA-related physician visits, which were identified based on the aforementioned ICD codes in any of the three diagnostic code fields.

ACCS and NACRS contains data on hospital-based and community-based ambulatory care, including day surgery, outpatient and community-based clinics and emergency departments, and publicly funded hospital support services such as physiotherapy and occupational therapy. OA-related records were identified based on the presence of the aforementioned ICD codes in any of the 10 diagnostic code fields. NACRS was used since April 2010.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in setting the research question, the design and conduct of the study. No patients were involved in the interpretation or writing up of results. There are no plans to disseminate the results of the research to study participants because this was admin health database analysis. We will make the publication available to the relevant patient community.

Case definition of OA

Validated case definitions have been used in previous research related to OA using administrative data.11 12 The sensitivity of algorithms based on both physician claims and hospitalisations records within 2–5 years ranged from 24% to 46%, along with specificity and positive predictive value ranging from 92% to 98%, and 39% to 54%, respectively11. In this study, OA cases were identified as individuals with at least one OA-related hospitalisation (DAD), or at least two OA-related physician visits (claims) within 2 years, or at least two OA-related ambulatory care visits (ACCS/NACRS) within 2 years, assuming none of the physicians or ambulatory care visits had occurred on the same day.11 For our study, the OA cohort refers to those Alberta residents registered with AHCIP who have a specified OA-related diagnostic code in any diagnostic code field position. The cohort inclusion date is the earliest date of the OA-related record identified from either the Claims, DAD or ACCS/NACRS files.

Case definitions of comorbidities

We identified specific comorbidities to explore in this analysis based on three criteria: (1) a high frequency of reported comorbidities in the published literature on OA; (2) the availability of validated case definitions for each comorbid condition; and (3) expert input from our clinical coinvestigators. We first conducted a scoping review of the literature,13 aiming to examine the extent and range of comorbidities research among people with OA. We identified 20 studies from a range of countries (9 in North America, 8 in Europe, 1 in Asia, 1 in South American, 1 in Netherlands), using different study designs (9 cross-sectional, 5 retrospective cohort, 5 prospective cohort and 1 case control study) with a range of sample sizes (91–85 966 369 cases of OA). Based on the results of this review, we derived a list of comorbidities and presented it to our clinical coinvestigators. On this basis, we identified eight comorbidities to include in our analysis: hypertension, depression, COPD, diabetes, congestive heart failure (CHF), peripheral vascular disease (PVD), myocardial infarction (MI) and cerebrovascular disease (CEVD). We applied case definitions for each comorbidity to identify those present within 3 years prior to the OA diagnosis. Detailed ICD 9 and ICD 10 diagnostic codes used to identify each comorbidity are provided in online supplementary appendix 1.14–23

bmjopen-2019-033334supp001.pdf (79.6KB, pdf)

Age-standardised comorbidity prevalence rate

The frequency of each comorbid condition in people meeting the case definition for OA was calculated, as was the frequency of the number of comorbidities present per individual: one comorbidity, two comorbidities and three or more comorbidities. We stratified OA cases by sex, and by age at diagnosis (<35, 35–44, 45–54, 55–65, 65–74 and ≥75 years). The crude rate was calculated as the number in each comorbidity group divided by the total number of OA cases. We calculated age-standardised comorbidity prevalence rates using the direct standardisation method.24 We used the 2016 Canadian population reported publicly by Statistics Canada25 to age-standardise the estimates for females and males with 95% CIs calculated using the binomial approximation method.24 To compare differences between females and males, standardised rate ratios (SRR) were estimated as the female age-standardised rate divided by the male age-standardised rate. We calculated 95% CIs for the SRR based on the SE for each sex, to test for a sex difference.24

We calculated the percentage of females and males in each age group and the percentage of OA cases for each age group by sex. The percentage of comorbidities among OA population was calculated as the number of cases with specific comorbidity divided by the OA population. The percentage of comorbidities among those with comorbidities was calculated using the population with one or more of the eight comorbidities as denominator. We also calculated the frequency of common groupings of these comorbidities in people with OA.

We applied χ2 tests of independence with a Bonferroni correction26 to compare the percentage of specific comorbid conditions among the population with OA in each age group (<45, 45–64 and ≥65 years). The null hypothesis is that there is no difference in the percentage of comorbidities across age groups, which is rejected when the calculated χ2 is greater than the critical value for a specific number of df and an altered significance level of 0.005 after Bonferroni correction. All analyses were conducted with R V.3.5.1 and Excel 2013.

Results

We identified 497 362 cases of OA, 57.9% of whom were females (table 1). More than half of the OA cases had at least one of the eight comorbidities (54.6%, n=271 794) (table 2). A total of 161 315 (32.4%) people with OA had only one comorbidity, with 14.6% (n=72 567) having two and 7.6% (n=37 912) having three or more of the comorbidities. Hypertension was the most frequent comorbidity (29%, n=144 453), followed by depression (19.9%, n=99 103), COPD (18.6%, n=92 273), diabetes (9.5%, n=47 102) and CHF (5.6%, n=27 905). PVD (3.0%), CEVD (1.2%) and MI (1.0%) were the least frequent comorbidities.

Table 1.

Characteristics of people with OA identified in the population

| Population | Age groups (years) |

Female | Male | Total | ||||

| n | % by age groups | % (Female) | n | % by age groups | % (Male) | |||

| People meeting OA case definition | <35 | 13 975 | 50.6 | 4.9 | 13 638 | 49.4 | 6.5 | 27 613 |

| 35–44 | 25 616 | 52.4 | 8.9 | 23 279 | 47.6 | 11.1 | 48 895 | |

| 45–54 | 57 574 | 57.6 | 20.0 | 42 445 | 42.4 | 20.3 | 100 019 | |

| 55–64 | 65 528 | 57.1 | 22.8 | 49 329 | 42.9 | 23.6 | 114 857 | |

| 65–74 | 59 346 | 57.7 | 20.6 | 43 527 | 42.3 | 20.8 | 102 873 | |

| 75+ | 65 912 | 63.9 | 22.9 | 37 193 | 36.1 | 17.8 | 103 105 | |

| Total | 287 951 | 57.9 | 100.0 | 209 411 | 42.1 | 100.0 | 497 362 | |

% by age groups was calculated using total population of each specific age group (eg, for OA <35 years), the percentage was calculated using the number of females with OA as the numerator and the total number of people with OA as the denominator (13 975+13 638= 27 613). % female <35 years was calculated using the number of females in the age group <35 years as the numerator (13 975) and the number of females with OA as the denominator (287 951).

OA, osteoarthritis.

Table 2.

Frequency, percentage and age-standardised rate of comorbidities in people with OA

| Comorbidity | n | % of OA cohort | % of the OA cohort with one or more of the eight comorbidities | Age standardised rate (per 1000 population) | ||

| Female (95% CI) | Male (95% CI) | SRR (95% CI) | ||||

| Comorbid conditions | ||||||

| Hypertension | 144 453 | 29.0 | 53.1 | 162.2 (160.9 to 163.5) | 146.5 (145.1 to 148.0) | 1.11 (1.09 to 1.12) |

| Depression | 99 103 | 19.9 | 36.5 | 264.1 (260.9 to 267.3) | 152.6 (149.8 to 155.4) | 1.73 (1.69 to 1.77) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 92 273 | 18.6 | 33.9 | 195.9 (193.0 to 198.8) | 153.6 (150.9 to 156.3) | 1.28 (1.25 to 1.30) |

| Diabetes | 47 102 | 9.5 | 17.3 | 53.1 (52.0 to 54.2) | 59.4 (58.4 to 60.4) | 0.89 (0.87 to 0.92) |

| Congestive heart failure | 27 905 | 5.6 | 10.3 | 24.4 (23.9 to 24.9) | 25.4 (24.9 to 26.0) | 0.96 (0.93 to 0.99) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 15 044 | 3.0 | 5.5 | 12.6 (12.1 to 13.0) | 17.8 (17.2 to 18.3) | 0.71 (0.67 to 0.74) |

| Myocardial infarction | 4969 | 1.0 | 1.8 | 4.3 (4.1 to 4.5) | 4.7 (4.4 to 5.0) | 0.91 (0.84 to 0.98) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 5974 | 1.2 | 2.2 | 4.0 (3.8 to 4.2) | 7.9 (7.6 to 8.2) | 0.51 (0.48 to 0.54) |

| No of comorbidities | ||||||

| One comorbidity | 161 315 | 32.4 | 59.4 | 329.1 (325.7 to 332.4) | 271.5 (268.2 to 274.8) | 1.21 (1.19 to 1.23) |

| Two comorbidities | 72 567 | 14.6 | 26.7 | 124.9 (122.8 to 127.1) | 84.6 (82.9 to 86.2) | 1.48 (1.44 to 1.52) |

| Three or more comorbidities | 37 912 | 7.6 | 13.9 | 42.3 (41.4 to 43.2) | 36.9 (36.2 to 37.7) | 1.15 (1.11 to 1.18) |

| OA with comorbidities | 271 794 | 54.6 | 496.3 (492.8 to 499.8) | 392.9 (389.4 to 396.4) | 1.26 (1.25 to 1.28) | |

| None of the 8 comorbidities | 225 568 | 45.4 | 503.7 (500.17 to 507.22) | 607.1 (603.56 to 610.56) | 0.83 (0.82 to 0.84) | |

% of OA cohort was calculated using OA population (271 794+225 568 = 497 362) as denominator and the population of each comorbidity as numerator. % of the OA cohort with one or more of the eight comorbidities was calculated using population with at least one comorbidity (n=271 794) as denominator. SRR denotes standardised rate ratio between females and males (females/males). The eight comorbidities are those with validated case definitions for administrative health data.

OA, osteoarthritis.

Comorbidity patterns by sex

A similar pattern was observed regarding the number of comorbidities (with most people with OA having one comorbidity) and the ordering of the frequency of each of the comorbidities among females and males based on age-standardised prevalence rates (table 2). Statistically significant differences among females and males were observed by the number of comorbidities, with females having higher age-standardised rates overall (SRR=1.26, 95% CI 1.25 to 1.28). The number of comorbidities was also higher for females compared with males with SRR ranging from 1.15 (95% CI 1.11 to 1.18) for three or more comorbidities to 1.48 (95% CI 1.44 to 1.52) for two comorbidities (table 2).

Depression, COPD and hypertension remained as the three most prevalent comorbidities in both females and males after age standardisation. However, the prevalence of each of these comorbidities was higher in females compared to males (table 2). Females had significantly higher prevalence rates than males for depression (SRR=1.73, 95% CI 1.69 to 1.77), COPD (SRR=1.28, 95% CI 1.25 to 1.30) and hypertension (SRR=1.11, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.12).

The prevalence of each of these three comorbidities differed significantly in females. For example, the age-standardised prevalence of depression in females was 264 cases per 1000 population, 35% higher and statistically higher than for COPD (196 cases per 1000 population) (SRR=1.35, 95% CI 1.32 to 1.37). In contrast, the prevalence of these three comorbidities among males were not significantly different.

Common groupings of comorbidities in people with OA

As shown in table 3, of the eight comorbidities in people with OA, the most frequent comorbidity was hypertension as a single comorbidity, found in 12.8% of people with OA (n=63 520). The most common grouping of two comorbidities was the coexistence of hypertension and depression (2.9%, n=14 609). The most common grouping with three comorbidities was depression, COPD and hypertension (1.1%, n=5262). People with OA having any combination of the top three comorbidities accounted for ~40% of people with OA.

Table 3.

Frequency of top 10 common groupings of comorbidities

| Combinations of comorbidity | n | % of OA cohort | % of OA with comorbidities |

| Hypertension only | 63 520 | 12.8 | 23.4 |

| Depression only | 46 226 | 9.3 | 17.0 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease only | 34 464 | 6.9 | 12.7 |

| Hypertension, depression | 14 609 | 2.9 | 5.4 |

| Hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 13 653 | 2.7 | 5.0 |

| Depression, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 13 584 | 2.7 | 5.0 |

| Hypertension, diabetes | 11 784 | 2.4 | 4.3 |

| Diabetes | 11 054 | 2.2 | 4.1 |

| Hypertension, depression, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 5262 | 1.1 | 1.9 |

| Hypertension, congestive heart failure | 3946 | 0.8 | 1.5 |

% of OA cohort was calculated using OA population (271 794+225 568 = 497 362) as denominator and the population of each comorbidity as numerator. % of OA with comorbidities was calculated using population with at least one comorbidity at the diagnosis of OA (n=271 794) as denominator.

OA, osteoarthritis.

Comorbidity patterns by age group

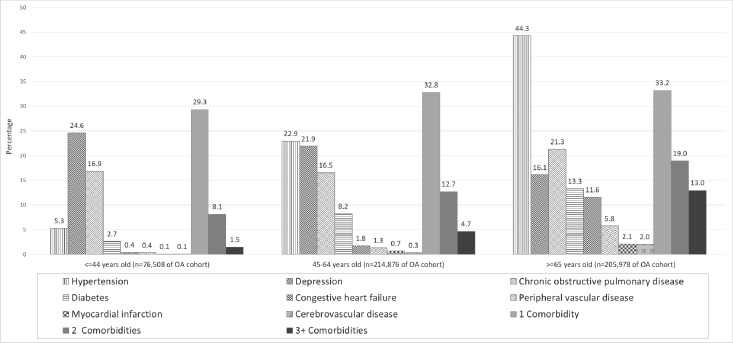

As shown in figure 1, each of the eight comorbidities, with the exception of depression, was most common in people with OA over 65 years old. Hypertension was found in 44.3% of people with OA over 65 years of age (n=91 153 cases) compared with 5.3% (n=4040 cases) in those <44 years old. The largest number of people with OA and depression were in the 45–64 years age cohort (n=47 061 cases), with the youngest age group (<44 years) having the highest percentage of cases with depression (24.6% compared with 21.9% in the middle age group (45–64 years) and 16.1% in the older age group (≥65 years)). The difference in the percentage of each of the eight comorbidities among the three age groups was statistically significant (p<0.0001). The detailed age-sex stratified crude rates per 1000 population is provided in online supplementary appendix 2.

Figure 1.

Percentage of specific comorbid conditions among the population with OA in each age group (<45, 45–64 and ≥65 years). The difference by age group was statistically significant for each comorbid conditions (p<0.0001), as was the frequency of the number of comorbidities present per individual (p<0.0001). OA, osteoarthritis

bmjopen-2019-033334supp002.pdf (84.3KB, pdf)

The number of comorbidities in people with OA increased with increasing age. The percentage of people with three or more comorbidities increased significantly from 1.5% in youngest age group (<44 years), to 4.7% in the middle age group (45–64 years) and to 13% in the older age group (≥65 years) (p<0.0001).

Discussion

We estimated the prevalence of comorbid conditions in people with OA using provincial administrative health data. Using validated case and comorbidity definitions, we found that 54.6% of people with OA had at least one of the eight comorbidities, and 22.2% had at least two. Depression, COPD and hypertension were the three most prevalent comorbidities in both females and males after age standardisation. However, the prevalence of each of these comorbidities was significantly higher in females compared with males. People with any combination of these three comorbidities represented about 40% of the people with OA. In general, the number of comorbidities in people with OA increased with increasing age. Each of the eight comorbidities, except depression, was most common in people with OA ≥65 years. The largest number of people with OA and depression are in the middle age group (45–64 years), with the youngest age group (<44 years) having the highest percentage of cases with depression.

The estimated prevalence of comorbidities varies among studies due to differences in case definitions, the list of included chronic conditions, data sources and study population. We estimated that the prevalence of comorbidity among people with OA was 54.6% for one or more of the eight comorbid chronic conditions and 22.2% for two or more comorbid chronic conditions with OA. Our estimates of the prevalence of comorbidities in people with OA are higher than the prevalence of two or more and three or more chronic conditions among the general Canadian population (26.5% and 10.2%, respectively) as reported by Feely et al,27 and higher than the prevalence of 12.9% (two or more chronic diseases) and 3.9% (three or more chronic diseases) reported by Roberts et al.28 In our study, among 205 978 OA cases in the age group over 65 years old, the prevalence of one or more comorbid chronic conditions was 33.2% (n=68 418) and the prevalence of two or more comorbid chronic conditions with OA was 19.0% (n=39 044). The estimated prevalence of comorbid chronic conditions in people with OA is higher than the estimates reported by Roberts et al, which showed that the prevalence of two or more chronic diseases in the general population over 65 years old was 31.3% and the prevalence of three or more chronic diseases was 11.3%. It has been reported previously that the prevalence of one or more comorbid condition among people with musculoskeletal conditions was more than twice than those without a musculoskeletal condition but with another chronic condition.29

We identified depression, COPD and hypertension as frequent comorbid conditions among the people with OA. This was consistent with findings reported from the Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network showing that the prevalence of OA has significant association with depression, COPD and hypertension.2 Depression is emerging as a significant comorbidity in OA. Previous findings have reported that depression was highly prevalent in people with OA.10 30 A systemic review of depressive symptoms in people with OA, including 49 studies worldwide and representing 15 855 individuals, reported a frequency of depression of 19.9% among people with OA,31 which was similar to our estimates.

Depressed individuals are more likely to report chronic or more severe pain, and more than half of the patients with chronic pain are depressed. People living with OA are known to have fewer social contacts, limited physical activity, increased pain and disability,32 33 worse surgical outcomes and reduced effectiveness of pain interventions,34 which are all important predictors of depression.35 However, current clinical practice guidelines for non-surgical management of OA do not include recommendations regarding mental health management.36–39 This emphasises the need for treatments and management for depression to improve outcomes for people with OA.40 It has been suggested that educating physicians about timely identification of psychological factors may be helpful to improve outcomes. In addition, self-care management could be integrated into OA management strategies as a way to reduce anxiety and depression, as well as resulting emotional and physical pain. Guidelines suggest that OA management should also integrate pharmacotherapy carefully and be cautious about the drug interactions and adverse side effects when treating OA, depression, anxiety and pain holistically.30 Two or more of the comorbidities that we examined coexist in a substantial proportion of people with OA—approximately 22% in total. Obesity, which we were unable to study using administrative data, is also prevalent among people with OA and a risk factor for developing OA.41 42 From a clinical practice perspective, a physician has to consider the implications of prescribing non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications for pain management, but this may worsen hypertension and have an associated increased risk of cardiovascular disease. However, without good pain management, it is difficult for patients with OA to engage in exercise programme which can help improve their muscular condition and potentially reduce obesity and hypertension. This is further complicated by the relationship of lower socioeconomic status with an increased risk of developing OA as demonstrated in the project for an Ontario Women’s Health Evidence-based Report.29

Furthermore, our analyses showed that depression not only was the most prevalent comorbidity after age standardisation in people with OA, but that rates of depression were significantly higher for females and younger people (<44 years old). The study by Dibonaventura et al reported that people under 65 years of age were still participating in the workforce; however, OA pain resulted in significantly lower productivity and higher costs compared with those without OA pain.8 They identified unique treatment gaps for patients younger than 60 years old because the non-operative treatment options were ineffective in long-term management of OA symptoms, but young patients were too young or maybe unwilling to undergo definitive treatment such as total joint replacement.43 Even for those patients who undergo total joint replacement, they were more likely to be dissatisfied about the treatment than older patients, and reported poorer outcomes including residual pain and stiffness.44 45 A survey of orthopaedic surgeons found that 84% perceived a need for better treatment for younger (<60 years old) physically active OA patients, and 68.4% perceived that there is a treatment gap for these patients.43 Due to the different presentations of comorbidities and treatment options among young and old age groups, it is imperative to examine the impact of comorbidities on management strategies in an age-stratified OA cohort.

Most clinical practice guidelines focus on single conditions.46 Fortin et al concluded that even though the quality of the Canadian guidelines was good, their relevance for patients with two or more chronic conditions was limited.47 Boyd et al highlighted the lack of consideration of comorbidities in clinical practice guidelines may result in poor quality of care because the healthcare some patients received was not optimal.48 Sharma et al pointed out that the present literature fails to fully address the management strategies when dealing with comorbidities seen in people with OA.30 Patient-centred care has been recommended in clinical practice guidelines with the aim of improving quality of care by focusing on the patient as a whole rather than on a single disease.49 From a system perspective, patients with several comorbidities were also the main users of healthcare resources and services.50 Patient-centred and coordinated care for these patients may decrease related healthcare use.51 It was recommended that physicians consider these comorbidities in the management of people with OA.

A strength of our study is the large population-based number of people with OA (n=497 362) and the investigation of a group of eight comorbidities that are clinically relevant to the management of people with OA. These eight comorbidities among people with OA has been reported in previous studies, but only on an individual basis or in groups of a subset of these comorbidities. Our study is the first one to include all of these comorbidities, which is necessary to understand the clinical context for managing these patients. Furthermore, our analysis also delineates the patterns of occurrence and co-occurrence of these comorbidities regarding the prevalence of comorbidities that is relevant for planning and delivery of health services for this growing population of people with OA. We applied case definitions for administrative health data to identify cases of OA and each of the comorbidities at the diagnosis of OA. A limitation of our study is that case identification based on administrative data may result in underreporting of cases and comorbidities. The case definitions for OA in administrative data research,5 based on the physician claims and hospitalisations records, have been applied and validated with a sensitivity of 24%, high specificity of 98% and a positive predictive value of 54%.11 In our study, we also included ACCS/NACRS to mitigate the issue of underestimations.6 Nonetheless, the estimated number of OA cases using this approach is almost certainly an underestimate. Similarly, the algorithms for comorbidities may underestimate the prevalence of these comorbidities; the sensitivity for identifying depression is from 36% to 51%,19 for PVD is 39%18 and for COPD is 53%21 in administrative data (online supplementary appendix 2). More importantly, the reported levels of comorbidity in patients with OA were measured at the time of OA diagnosis. New cases of comorbidity diagnosed after the OA diagnosis were not identified. Further, we limited our analysis to eight comorbidities of clinical relevance and for which there were case definitions in administrative data.

Conclusions

We found that depression, COPD and hypertension were the three most prevalent comorbidities in people with OA, with rates significantly higher in females compared with males. Of particular note is that the largest number of people with OA and depression are in the age group between 45 and 64 years old, with the highest percentage of cases occurring in the younger age groups (<44 years). Our findings highlight the need to recognise that people with OA have high rates of comorbidities and this may affect optimal healthcare management of these patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the following team members and their contributions to the study: Behnam Sharif.

Footnotes

Contributors: DAM, PDF and KY were responsible for the conception and design of the research, acquisition of the data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article and revision of the article for important intellectual content. XL was responsible for the analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article and revision of the article for important intellectual content. ChB, ClB, DM, TN, JW and LL were responsible for the conception and design of the research, interpreting results of the research and revision of the article for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript to be submitted. DAM (damarsha@ucalgary.ca) and XL (xiaoxili@ucalgary.ca) take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole.

Funding: This research was funded through a Canadian Institute for Health Research (CIHR) Operating Grant (Grant #: 126128) and the Arthur J.E. Child Chair in Rheumatology Research. There were no study sponsors and the funding agencies had no involvement in the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. DAM was supported by a Canada Research Chair and the Arthur J.E. Child Chair in Rheumatology Research. XL was supported by the Arthur J.E. Child Chair in Rheumatology Research, the Cumming School of Medicine Postdoctoral Scholarship and the Postdoctoral Scholarship funded by the O’Brien Institute of Public Health and the McCaig Institute for Bone and Joint Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval for this project was provided by the Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Calgary (REB13-0100).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available.

References

- 1. Leite AA, Costa AJG, Lima BdeAMde, et al. Comorbidities in patients with osteoarthritis: frequency and impact on pain and physical function. Rev Bras Reumatol 2011;51:118–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Birtwhistle R, Morkem R, Peat G, et al. Prevalence and management of osteoarthritis in primary care: an epidemiologic cohort study from the Canadian primary care sentinel surveillance network. CMAJ Open 2015;3:E270–5. 10.9778/cmajo.20150018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bombardier C, Hawker G, Mosher D. The impact of arthritis in Canada: today and over the next 30 years; 2011.

- 4. Kadam UT, Jordan K, Croft PR. Clinical comorbidity in patients with osteoarthritis: a case-control study of general practice consulters in England and Wales. Ann Rheum Dis 2004;63:408–14. 10.1136/ard.2003.007526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kopec JA, Rahman MM, Berthelot J-M, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of osteoarthritis in British Columbia, Canada. J Rheumatol 2007;34:386–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Marshall DA, Vanderby S, Barnabe C, et al. Estimating the burden of osteoarthritis to plan for the future. Arthritis Care Res 2015;67:1379–86. 10.1002/acr.22612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tarride J-E, Haq M, O'Reilly DJ, et al. The excess burden of osteoarthritis in the province of Ontario, Canada. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:1153–61. 10.1002/art.33467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. dacosta DM, Gupta S, McDonald M, et al. Evaluating the health and economic impact of osteoarthritis pain in the workforce: results from the National health and wellness survey. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2011;12 10.1186/1471-2474-12-83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rosemann T, Joos S, Szecsenyi J, et al. Health service utilization patterns of primary care patients with osteoarthritis. BMC Health Serv Res 2007;7:169 10.1186/1472-6963-7-169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kim KW, Han JW, Cho HJ, et al. Association between comorbid depression and osteoarthritis symptom severity in patients with knee osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011;93:556–63. 10.2106/JBJS.I.01344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lix L, Yogendran M, Mann J. Defining and validating chronic diseases: an administrative data approach and update with ICD-10-CA; 2008.

- 12. Kopec JA, Rahman MM, Sayre EC, et al. Trends in physician-diagnosed osteoarthritis incidence in an administrative database in British Columbia, Canada, 1996-1997 through 2003-2004. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:929–34. 10.1002/art.23827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pham MT, Rajić A, Greig JD, et al. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods 2014;5:371–85. 10.1002/jrsm.1123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McCormick N, Lacaille D, Bhole V, et al. Validity of myocardial infarction diagnoses in administrative databases: a systematic review. PLoS One 2014;9:e92286 10.1371/journal.pone.0092286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Quan H, Khan N, Hemmelgarn BR, et al. Validation of a case definition to define hypertension using administrative data. Hypertension 2009;54:1423–8. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.139279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McCormick N, Bhole V, Lacaille D, et al. Validity of diagnostic codes for acute stroke in administrative databases: a systematic review. PLoS One 2015;10:e0135834 10.1371/journal.pone.0135834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McCormick N, Lacaille D, Bhole V, et al. Validity of heart failure diagnoses in administrative databases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2014;9:e104519 10.1371/journal.pone.0104519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fan J, Arruda-Olson AM, Leibson CL, et al. Billing code algorithms to identify cases of peripheral artery disease from administrative data. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2013;20:e349–54. 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-001827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Townsend L, Walkup JT, Crystal S, et al. A systematic review of validated methods for identifying depression using administrative data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2012;21 Suppl 1:163–73. 10.1002/pds.2310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Leong A, Dasgupta K, Bernatsky S, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of validation studies on a diabetes case definition from health administrative records. PLoS One 2013;8:e75256 10.1371/journal.pone.0075256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Smidth M, Sokolowski I, Kærsvang L, et al. Developing an algorithm to identify people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) using administrative data. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2012;12:38 10.1186/1472-6947-12-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen G, Khan N, Walker R, et al. Validating ICD coding algorithms for diabetes mellitus from administrative data. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2010;89:189–95. 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 2005;43:1130–9. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Boyle P, Parkin D. Cancer registration: principles and methods. statistical methods for registries. IARC Sci Publ 1991;95:126–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Statistics Canada Census Profile, 2016 Census Alberta [Province] and Canada [Country]; 2016.

- 26. Bland JM, Altman DG. Multiple significance tests: the Bonferroni method. BMJ 1995;310:170 10.1136/bmj.310.6973.170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Feely A, Lix LM, Reimer K. Estimating multimorbidity prevalence with the Canadian chronic disease surveillance system. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can 2017;37:215–22. 10.24095/hpcdp.37.7.02 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Roberts KC, Rao DP, Bennett TL, et al. Prevalence and patterns of chronic disease multimorbidity and associated determinants in Canada. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can 2015;35:87–94. 10.24095/hpcdp.35.6.01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hawker GA, Badley EM, Jaglal S. Musculoskeletal Condtitions. In: Project for an Ontario Women’s Health Evidence-Based Report. Toronto; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sharma A, Kudesia P, Shi Q, et al. Anxiety and depression in patients with osteoarthritis: impact and management challenges. Open access Rheumatol Res Rev 2016;8:103–13. 10.2147/OARRR.S93516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stubbs B, Aluko Y, Myint PK, et al. Prevalence of depressive symptoms and anxiety in osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 2016;45:228–35. 10.1093/ageing/afw001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sale JEM, Gignac M, Hawker G. The relationship between disease symptoms, life events, coping and treatment, and depression among older adults with osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol 2008;35:335–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hawker GA, Gignac MAM, Badley E, et al. A longitudinal study to explain the pain-depression link in older adults with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2011;63:1382–90. 10.1002/acr.20298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gleicher Y, Croxford R, Hochman J, et al. A prospective study of mental health care for comorbid depressed mood in older adults with painful osteoarthritis. BMC Psychiatry 2011;11:147 10.1186/1471-244X-11-147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rosemann T, Backenstrass M, Joest K, et al. Predictors of depression in a sample of 1,021 primary care patients with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2007;57:415–22. 10.1002/art.22624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, part I: critical appraisal of existing treatment guidelines and systematic review of current research evidence. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2007;15:981–1000. 10.1016/j.joca.2007.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2008;16:137–62. 10.1016/j.joca.2007.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhang W, Nuki G, Moskowitz RW, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis: Part III: changes in evidence following systematic cumulative update of research published through January 2009. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2010;18:476–99. 10.1016/j.joca.2010.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2014;22:363–88. 10.1016/j.joca.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lin EHB, Katon W, Von Korff M, et al. Effect of improving depression care on pain and functional outcomes among older adults with arthritis. JAMA 2003;290 10.1001/jama.290.18.2428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Felson DT. Weight and osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol Suppl 1995;43:7–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Anderson JJ, Felson DT. Factors associated with osteoarthritis of the knee in the first National health and nutrition examination survey (Hanes I). Am J Epidemiol 1988;128:179–89. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Li CS, Karlsson J, Winemaker M, et al. Orthopedic surgeons feel that there is a treatment gap in management of early oa: international survey. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2014;22:363–78. 10.1007/s00167-013-2529-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bourne RB, Chesworth BM, Davis AM, et al. Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: who is satisfied and who is not? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010;468:57–63. 10.1007/s11999-009-1119-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Parvizi J, Nunley RM, Berend KR, et al. High level of residual symptoms in young patients after total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014;472:133–7. 10.1007/s11999-013-3229-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hughes LD, McMurdo MET, Guthrie B. Guidelines for people not for diseases: the challenges of applying UK clinical guidelines to people with multimorbidity. Age Ageing 2013;42:62–9. 10.1093/ageing/afs100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fortin M, Contant E, Savard C, et al. Canadian guidelines for clinical practice: an analysis of their quality and relevance to the care of adults with comorbidity. BMC Fam Pract 2011;12:74 10.1186/1471-2296-12-74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, et al. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: implications for pay for performance. JAMA 2005;294 10.1001/jama.294.6.716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Dawes M. Co-Morbidity: we need a guideline for each patient not a guideline for each disease. Fam Pract 2010;27:1–2. 10.1093/fampra/cmp106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Huntley AL, Johnson R, Purdy S, et al. Measures of multimorbidity and morbidity burden for use in primary care and community settings: a systematic review and guide. Ann Fam Med 2012;10:134–41. 10.1370/afm.1363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wolff JL, Starfield B, Anderson G. Prevalence, expenditures, and complications of multiple chronic conditions in the elderly. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:2269 10.1001/archinte.162.20.2269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-033334supp001.pdf (79.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-033334supp002.pdf (84.3KB, pdf)