Abstract

Numerical data in biology and medicine are commonly presented as mean or median with error or confidence limits, to the exclusion of individual values. Analysis of our own and others’ data indicates that this practice risks excluding ‘Goldilocks’ effects in which a biological variable falls within a range between ‘too much’ and ‘too little’ with a region between where its function is ‘just right’; a concept captured by the Swedish term ‘Lagom’. This was confirmed by a narrative search of the literature using the PubMed database, which revealed numerous relationships of biological and clinical phenomena of the Goldilocks/Lagom form including quantitative and qualitative examples from the health and social sciences. Some possible mechanisms underlying these phenomena are considered. We conclude that retrospective analysis of existing data will most likely reveal a vast number of such distributions to the benefit of medical understanding and clinical care and that a transparent approach of presenting each value within a dataset individually should be adopted to ensure a more complete evaluation of research studies in future.

Keywords: statistics & research methods, data analysis and interpretation, data distributions

Introduction

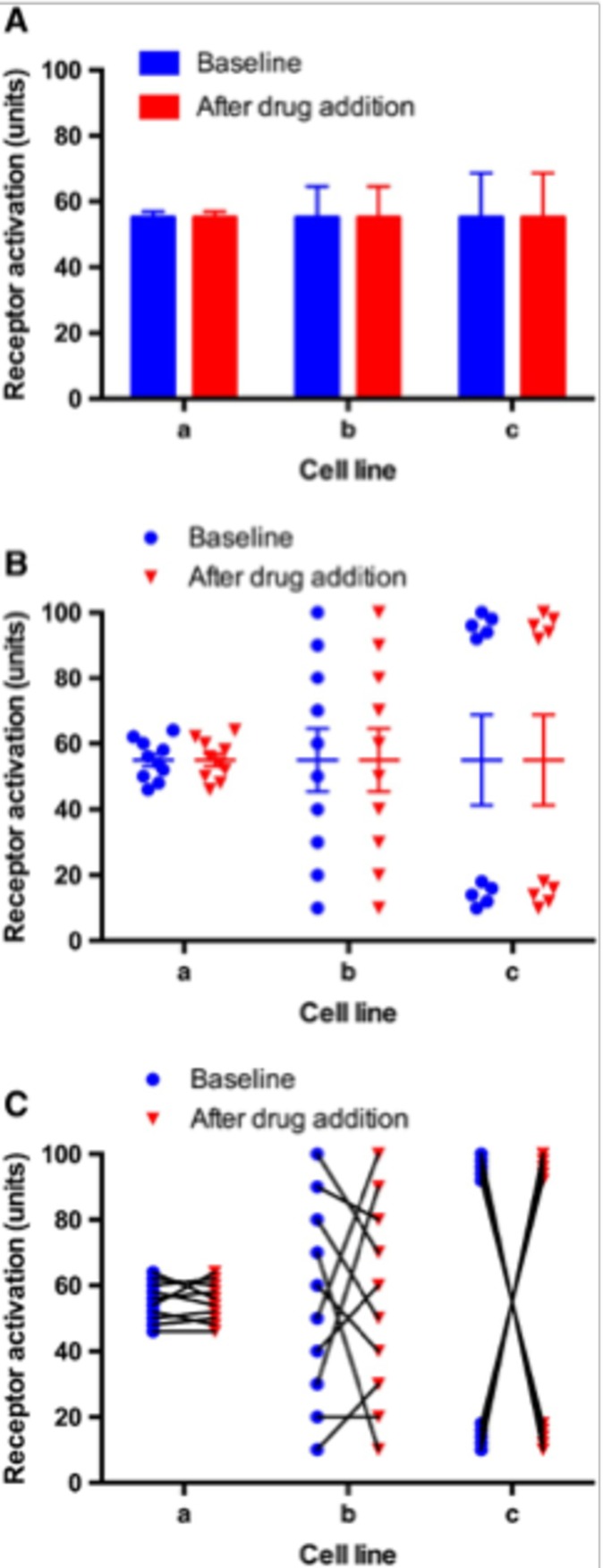

Numerical data in science and medicine have traditionally been presented as mean or median values with SEs or SDs. Such data commonly take the form of tables, bar graphs or line graphs. However, as Weissgerber et al1 point out, this practice poses a problem since different distributions of data can lead to the same bar or line graph. This was well illustrated elegantly by George et al2 who used illustrative data from a hypothetical experiment to examine the impact of three different cell lines on drug receptor activation and showed that a variety of distributions of individual data points can lead to similar bar graphs with the same mean (figure 1). This is because bar charts frequently do not convey major features of the dataset adequately. As figure 1 makes clear, moving away from using bar charts to visualise the entire dataset is a necessary refinement that can increase the transparency and reporting of data.

Figure 1.

An illustrative example of a comparison of cell lines is described, which shows that bar charts do not give the reader adequate information on the variability and distribution of each sampled ‘n’. The extent of activation of a receptor in three cell lines a, b and c under baseline (drug‐naïve) conditions and following the addition of a drug is given in arbitrary units. The same datasets are presented in three different ways: (A) bar chart, (B) grouped column scatter plot with means and error and (C) before–after scatter plot. n=10 (ie, biological replicates and not technical replicates). In this example, error bars represent the SEM although authors should consider the sampling size and distribution of ‘n’ when choosing the most appropriate way of showing experimental error (eg, SD or CI).

The attention paid to individual variation in cellular and molecular biological and clinical studies is relatively recent, but has been well-known for many years to ecologists, especially following the publication by Albert F Bennett,3 in 1987, of an influential article entitled: ‘Inter-individual variability: an underutilized resource’. Bennett, an ecological physiologist, pointed out that mean values with CIs about the mean, once published tend to ‘—take on a life of their own, and become the only point of analysis and comparison’ to the exclusion of the individual values, and their potential significance. Bennett referred to this tendency as ‘the tyranny of the Golden Mean’, and as an alternative, advocated the analysis of interindividual variability, that is, the full range of individual values, he considered could provide the observer with a greater interpretative repertoire.

In the time since Bennett’s paper, there has been a movement away from the tyranny of the mean in many areas of biology, notably in ecology.4 Examples are provided by Stephen J Gould,5 who wrote an article on ‘The median isn’t the message’, Hayes and Jenkins6 on individual variation in mammals, and Lloyd-Smith7 on the spread of epidemics of human disease.

Our interest in interindividual variability arose particularly from research in which we have been involved on (1) the development and metabolism of single preimplantation mammalian embryos (DRB, HJL, RS) and (2) of glycaemic control in individual human subjects (TS).

Development and metabolism of single preimplantation embryos

Data which illustrate the value of distributions rather than mean or median values were provided by Guerif et al8 who measured the consumption of the essential nutrient, pyruvate, by single bovine preimplantation embryos at the zygote stage (1 cell fertilised egg; day 1 of development). The experiments revealed considerable heterogeneity between individual embryos such that it was possible to divide them prospectively into three groups—of ‘high’, ‘intermediate’ and ‘low’ pyruvate consumption at an early stage (day 2)—and track their subsequent development to the blastocyst stage, a critical developmental endpoint. These data indicated that intermediate values of pyruvate consumption correlated with viability (capacity to form a blastocyst), though with considerable overlap between the categories. Put another way, which takes account of this overlap, plotting individual values revealed the existence of an optimal ‘range’ of metabolic activity. This concept was developed in a follow-up paper9 in which we proposed that the optimal range was equivalent to a ‘Goldilocks zone’ or as it is known in Sweden, of ‘Lagom’, meaning ‘just the right amount’, in which embryos with maximum developmental potential are located.

Glycaemic control

Glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) is a marker of glycaemic control in patients with diabetes which is commonly used in clinical practice. Indeed, HbA1c is the recommended test for diagnosing diabetes.10 There is an association between the extent of high blood glucose as measured by HbA1c and the risk of death and of macrovascular and microvascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM).11 In the landmark UK Prospective Diabetes Study, intensive glycaemic control that aimed to achieve a HbA1c level of 7% or below was associated with improved outcome in newly diagnosed patients with T2DM.12 This finding was then extrapolated to all patients with T2DM, and as a result, lower HbA1c levels were recommended for management of patients with T2DM. However, concerns arose as data from the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes trial began to emerge showing increased all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality in the intensive treatment group who were treated with antihyperglycaemic agents aiming for a lower HbA1c target of 6% compared with conventional antihyperglycaemic treatment in patients with T2DM aiming for HbA1c of 7%–7.9%. These results led to early termination of the trial.13 Further studies14 15 have demonstrated that lower and higher mean HbA1c values were associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events and mortality suggesting a ‘Goldilocks’ or Lagom state of HbA1c is the optimal.

Similar ‘U’ shaped associations with HbA1c and all-cause mortality have also been shown for type 1 diabetes.16 Even in patients without diabetes, extremes of glycaemia as measured by HbA1c are associated with adverse clinical outcomes including cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality. Similar increases in mortality in either extremes are seen with body weight, blood pressure, birth weight, cholesterol and other cardiovascular risk factors.

Goldilocks and Lagom

The Goldilocks zone has been defined mathematically by Kohn and Melnick17 in the context of xenobiotic ligand binding to nuclear receptors as a ‘Non-monotonic receptor-mediated dose-response curve’ (NMDRC), and by Vandenberg18 in the context of endocrine disrupting chemicals as ‘a response where the slope of the curve changes sign from positive to negative or vice versa somewhere along the range of doses examined’. These are valuable definitions because they can be applied to all non-linear distributions including U-shaped, inverted U-shaped, J-shaped, sigmoidal and reverse sigmoidal.

The U-shaped curve is probably the most widely observed. It usually refers to the nonlinear relationship between two variables, in particular, a dependent and an independent variable. Because many analytical methods assume an underlying linear relationship, systematic deviation from linearity can lead to bias in estimation of safe levels in exposure to nutrients, drugs or toxic agents (for a discussion, see section Mechanisms underlying the Goldilocks principle and what is Lagom and Vandenberg18).

How widespread is the presence of a Goldilocks zone in biology and medicine?

We thought it might be instructive to discover how widely the notion of a Goldilocks zone is a feature of the wider biological literature, especially as applied to medicine. A comprehensive search for information conducted on the PubMed database in early 2018 using the term ‘Goldilocks’ revealed 184 entries, all of which have been examined, together with the grey literature. Only articles in English language were selected. A selection of 43 of these publications has been presented (online supplementary appendix 1) as representative of the range of phenomena which invoke the Goldilocks concept in order to increase biological and clinical understanding. It should be emphasised that this is a narrative review rather than systematic review and no judgement on the quality of these studies or of those which have been omitted is implied.

bmjopen-2018-027767supp001.pdf (73.1KB, pdf)

Inspection of these examples reveals the wide range of biological and clinical phenomena in which Goldilocks zones have been found including the health and social sciences which can be qualitative rather than quantitative. It seems likely that a vast number remain to be discovered and that authors could, in a relatively simple manner, derive added value from their existing data by presenting distributions rather than median/mean values, and making raw data available to the research community via online repositories. This would allow systematic reanalysis by data scientists with an interest in the Goldilocks/Lagom concept.

Mechanisms underlying the Goldilocks principle and what is Lagom

Mechanisms which are global in scope

We previously proposed an explanation that may account for Goldilocks/Lagom phenomena, derived from our work on energy efficiency in early mammalian embryo development9 which made use of an account of general aspects of biological optimisation by Johnson.19 The premise was that living things aim to function with the minimum input of energy, that is, with high energetic efficiency. To accomplish this will obviously require a threshold level of metabolic activity to ensure a given process proceeds in an optimum, yet efficient manner, while the upper limit will be set by the capacity to increase metabolism versus ‘the energy parsimony in almost everything (living things) do’.19 The Goldilocks/Lagom zone will obviously lie between these extremes. The boundaries will be set by homeostatic mechanisms at all levels of organisation. Such boundaries will be flexible in order to allow for the capacity to upregulate or downregulate metabolism in response to stress. Responses of these types have been usefully categorised by ecologists to distinguish (1) modest changes in metabolism (up or down within the optimum (Goldilocks/Lagom) range) from which the cell/organism can recover (the so-called Pejus range) and (2) extreme perturbation beyond the optimum which shifts metabolism irreversibly into a Pessimum range which is fatal (see figure 1 in the work of Sokolova).20

Specific mechanisms

Specific mechanisms for the production of NMDRCs were well summarised by Vandenberg18 in terms of the effect of endocrine disrupting chemicals, notably Bisphenol A on cells in culture, whole organisms, laboratory animals and human populations. Interestingly, it was reported that NMDRCs were common, comprising 20%–30% of all studies examined, depending on the conditions; for example, in vivo versus in vitro. Mechanisms considered included cytotoxicity,21 inhibition of cell proliferation22; hormone receptors produced versus degraded23; cell and tissue-specific cofactors24 and pharmacological effects. At the whole body level, examples of NMDRCs in nutrition are widespread, reflecting minimum requirments at the lower end of the distribution and toxicity at the higher, for example, vitamin A. Vandenberg18 concludes that ‘strong evidence for Non-monotonic receptor-mediated dose-response curves’—question the current risk assessment practice where ‘safe’ levels are predicted from high dose exposures’

Conclusion

There has long been a fixation in the biological and clinical research communities with presenting data solely as measures of dispersion (means and medians) and of central tendency (eg, SD and IQR). We believe that the retrospective analysis of existing data could reveal numerous potential relationships with a Goldilocks/Lagom pattern.

Interestingly, the editors of the British Journal of Pharmacology 2 ‘will now require that, where possible, numerical data (whether categorical or continuous), particularly involving two sets or paired data, should be presented using scatter-plots, before-after graphs, and other forms in which each individual ‘n’ value is individually plotted, rather than using bar charts. Authors presenting data as bar charts should state that a scatter plot or before–after charts did not reveal unusual or interesting aspects of the data not obvious from the bar chart’.

We believe the Journal should be complimented on this approach and urge all such journals to adopt it.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: HJL: conceived the study, conducted literature searches and wrote the first draft. All authors then commented on subsequent drafts. VA: provided statistical advice. DRB: contributed to the initial concept and provided new material, as did RS who also prepared the manuscript for submission. TS: contributed to initial concept, provided new material and clinical expertise.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement statement: No members of the public, nor patients, were involved in the preparation of this article.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Weissgerber TL, Milic NM, Winham SJ, et al. Beyond bar and line graphs: time for a new data presentation paradigm. PLoS Biol 2015;13:1–10. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. George CH, Stanford SC, Alexander S, et al. Updating the guidelines for data transparency in the British Journal of Pharmacology - data sharing and the use of scatter plots instead of bar charts. Br J Pharmacol. 2017;174:2801–4. 10.1111/bph.13925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bennett AF. Interindividual variability: an underutilized resource : Feder ME, Bennett AF, Burggren WW, et al., New directions in ecological physiology. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987: 147–69. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Roche DG, Careau V, Binning SA, et al. Demystifying animal 'personality' (or not): why individual variation matters to experimental biologists. J Exp Biol 2016;219:3832–43. 10.1242/jeb.146712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gould SJ. The Median Isn’t the Message. Available: https://people.umass.edu/biep540w/pdf/Stephen Jay Gould.pdf [Accessed 4 Oct 2018].

- 6. Hayes JP, Jenkins SH. Individual variation in mammals. J Mammal 1997;78:274–93. 10.2307/1382882 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lloyd-Smith JO, Schreiber SJ, Kopp PE, et al. Superspreading and the effect of individual variation on disease emergence. Nature 2005;438:355–9. 10.1038/nature04153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guerif F, McKeegan P, Leese HJ, et al. A simple approach for consumption and release (core) analysis of metabolic activity in single mammalian embryos. PLoS One 2013;8:e67834 10.1371/journal.pone.0067834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Leese HJ, Guerif F, Allgar V, et al. Biological optimization, the Goldilocks principle, and how much is lagom in the preimplantation embryo. Mol Reprod Dev 2016;83:748–54. 10.1002/mrd.22684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. American Diabetes Association Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2011;34:S62–9. 10.2337/dc11-S062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Khaw K-T, Wareham N. Glycated hemoglobin as a marker of cardiovascular risk. Curr Opin Lipidol 2006;17:637–43. 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3280106b95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Anon Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). The Lancet 1998;352:837–53. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07019-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Duckworth W, Abraira C, Moritz T, et al. Glucose control and vascular complications in veterans with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2009;360:129–39. 10.1056/NEJMoa0808431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Currie CJ, Peters JR, Tynan A, et al. Survival as a function of HbA1c in people with type 2 diabetes: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2010;375:481–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61969-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Forbes A, Murrells T, Mulnier H, et al. Mean HbA, HbA variability, and mortality in people with diabetes aged 70 years and older: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2018;6:476–86. 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30048-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schoenaker DAJM, Simon D, Chaturvedi N, et al. Glycemic control and all-cause mortality risk in type 1 diabetes patients: the EURODIAB prospective complications study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014;99:800–7. 10.1210/jc.2013-2824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kohn MC, Melnick RL. Biochemical origins of the non-monotonic receptor-mediated dose-response. J Mol Endocrinol 2002;29:113–23. 10.1677/jme.0.0290113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vandenberg LN. Non-monotonic dose responses in studies of endocrine disrupting chemicals: bisphenol A as a case study. Dose Response 2014;12:259–76. 10.2203/dose-response.13-020.Vandenberg [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Johnson AT. Teaching the principle of biological optimization. J Biol Eng 2013;7:6 10.1186/1754-1611-7-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sokolova IM. Energy-Limited tolerance to stress as a conceptual framework to integrate the effects of multiple stressors. Integr Comp Biol 2013;53:597–608. 10.1093/icb/ict028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Welshons WV, Thayer KA, Judy BM, et al. Large effects from small exposures. I. mechanisms for endocrine-disrupting chemicals with estrogenic activity. Environ Health Perspect 2003;111:994–1006. 10.1289/ehp.5494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Soto AM, Sonnenschein C, Prechtl N, et al. Methods to screen estrogen-agonists and antagonists. J Med Food 1999;2:139–42. 10.1089/jmf.1999.2.139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ismail A, Nawaz Z. Nuclear hormone receptor degradation and gene transcription: an update. IUBMB Life 2005;57:483–90. 10.1080/15216540500147163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jeyakumar M, Webb P, Baxter JD, et al. Quantification of ligand-regulated nuclear receptor corepressor and coactivator binding, key interactions determining ligand potency and efficacy for the thyroid hormone receptor. Biochemistry 2008;47:7465–76. 10.1021/bi800393u [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-027767supp001.pdf (73.1KB, pdf)