Abstract

A 71-year-old woman was referred with abdominal pain and weight loss. An abdominal CT showed a 5-cm heterogeneous mass in the head of the pancreas with involvement of the superior mesenteric vein and artery. Her carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and CA 19-9 were normal. Two endoscopic ultrasound/fine needle aspirates (EUS/FNAs) of the mass diagnosed her with a mesenchymal tumour of myogenic origin but did not show features of malignancy. Frozen section analysis of laparoscopic core biopsies also failed to show malignant features, hence requiring an open biopsy which confirmed the diagnosis of pancreatic leiomyosarcoma (PLMS). She was eventually treated with radiotherapy. To our knowledge this is the only case in recent English literature of inoperable locally advanced PLMS that has required an open biopsy to formalise the diagnosis despite prior EUS FNAs. We include a review of the literature, highlighting the deficiencies of various biopsy techniques.

Keywords: pancreas and biliary tract, pancreatic cancer, pathology, general surgery

Background

Pancreatic leiomyosarcoma (PLMS) is a very rare mesenchymal tumour, with 58 cases documented in the English literature since it was first reported in 1951.1 It accounts for only 0.1% of pancreatic tumours.2 Its diagnosis can be problematic as imaging characteristics are nonspecific. Hence, it requires demonstration of histopathological and immunohistochemical (IHC) features that can be difficult to demonstrate in biopsies obtained via minimally invasive means. To illustrate that point we present a case of PLMS that has required an open pancreatic biopsy to make a firm diagnosis despite having had two endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) guided fine needle aspirates (FNA).

Case presentation

A 71-year-old female patient was referred with a 6-month history of upper abdominal pain associated with 12 kg of weight loss. She had no vomiting or jaundice. Her medical history included gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and a hemithyroidectomy, which was performed 30 years prior. Physical examination was unremarkable. She was investigated with plain film X-ray of her abdomen which demonstrated a potential lesion in the pancreas. Subsequently, she was referred for CT.

Investigations

Her CT demonstrated a 5 cm heterogeneous head of pancreas mass with involvement of the superior mesenteric vein and artery but no biliary tract encroachment. On the portal venous phase, the mass was mildly enhancing peripherally with a necrotic centre (figure 1). There was no associated lymphadenopathy or liver metastases. A staging CT chest showed no other evidence of spread. Her blood test panel including liver function tests, amylase and tumour markers (CEA, CA 19–9, chromogranin A) were all normal.

Figure 1.

Axial CT scan of the abdomen showing head of pancreas mass with peripheral enhancement and central necrosis.

She underwent an EUS which identified a well-defined 47×49 mm hypoechoic oval mass in the pancreatic head which invaded into the portal vein (figure 2). The endosonographic appearance was highly suspicious for adenocarcinoma. FNA was performed with size 22 and 25 gauge needles with eight passes in total. Cytology demonstrated scant groups of atypical spindle cells.

Figure 2.

Endoscopic ultrasound of head of pancreas mass with sonographic evidence of invasion into portal vein (PV).

Given the inconclusive nature of the biopsy the patient underwent a second EUS/FNA. Ten passes were made with 22 and 25 gauge needles. Cytological examination revealed atypical spindle cells. IHC staining was positive for small muscle actin and desmin and negative for CD117, DOG1, CD34 and S100. A stromal tumour of myogenic subtype, such as leiomyoma or leiomyosarcoma, was thought likely. The cell block was inadequate to assess for mitosis, nuclear pleomorphism or necrosis.

Laparoscopy was undertaken to further sample the pancreatic mass. There was no evidence of peritoneal or liver deposits noted. The lesser sac was entered and an intraoperative ultrasound was used to demarcate the mass. Disposable 16/18G stylets (Bard Max Core biopsy instrument) were used to obtain three core biopsies, which were sent for frozen section. The pathologist again found atypical spindle cells and excluded adenocarcinoma. However, he could not identify malignant features on the core frozen samples to confirm the diagnosis of PLMS until further examination of formalin fixed paraffin embedded tissue later. Given the need to confirm the diagnosis promptly and to prevent further delays in treatment, an open biopsy was undertaken. A limited upper midline laparotomy was performed centred over the mass. The firm mass was again located sonographically before a 15×10 mm specimen (pale grey, hard) was sent off, taking care to avoid vessels and the pancreatic duct. A drain was placed. The patient made an uneventful recovery and was discharged 3 days later.

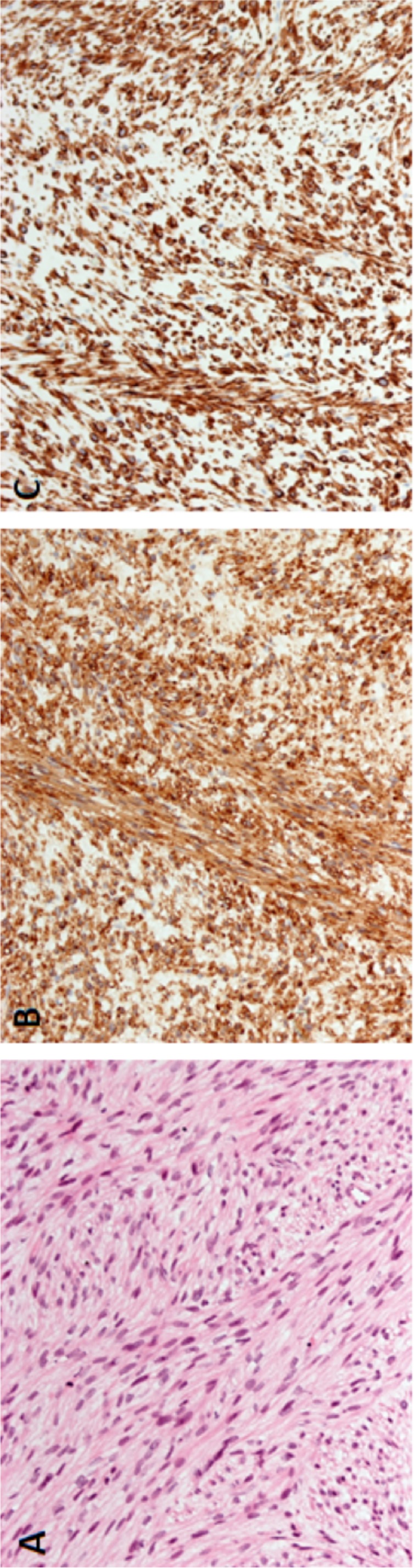

Histopathology of the submitted tissue revealed long, sweeping, interlacing fascicles of spindle cells with cigar-shaped nuclei and moderate nuclear pleomorphism (figure 3). Coagulative necrosis was noted in the specimen. There were scattered mitoses (approximately 5 mitoses/50 hpf). IHC stains were strongly and diffusely positive for vimentin, smooth muscle antigen (SMA), desmin, p16 and p53 and negative for CD 17, DOG1 and S100. The proliferation index (Ki-67) was 15%. Based on the morphological and IHC findings, a diagnosis of PLMS was made. It was classified as grade 2, per the French Federation of Cancer Systems.3

Figure 3.

Histopathological specimen from open biopsy of head of pancreas lesion. (A) H&E stain demonstrating fascicles of spindle cells and moderate nuclear pleomorphism. (B) Positive staining for SMA. (C) Positive staining for desmin.

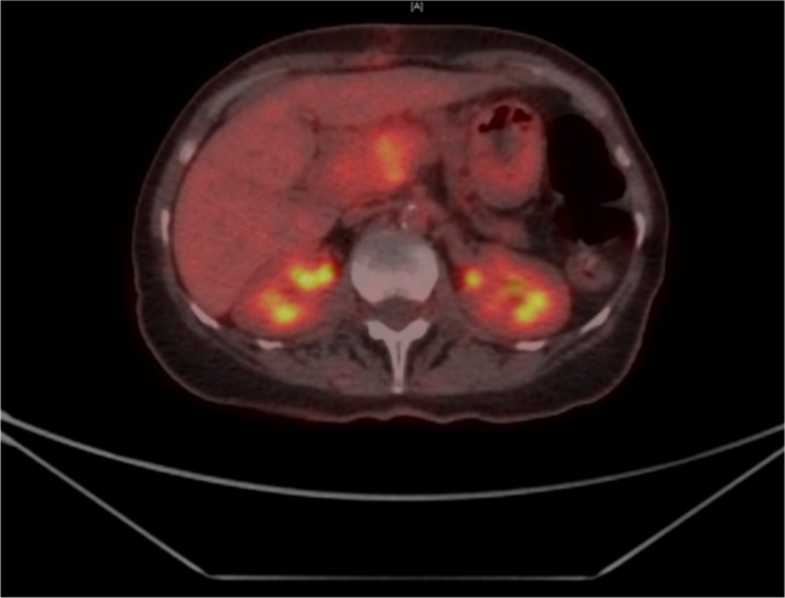

A positron emission tomography scan revealed a largely hypermetabolic pancreatic head/neck mass (figure 4). The posterior aspect of the tumour exerted a mass effect on the inferior vena cava. There was no evidence of hypermetabolic nodal or distant metastatic disease. Overall the tumour was staged as T2N0M0 (stage IIIA).4

Figure 4.

PET scan revealing hypermetabolic mass in pancreatic head/neck. PET; positron emission tomography.

Differential diagnosis

Other tumours may have similar radiological and preliminary histological features. Other retroperitoneal leiomyosarcomas such as those arising from the stomach, duodenum and retroperitoneal organs can also invade the pancreas and mimic the diagnosis.5–7 Pancreatic lesions that can mimic PLMS include undifferentiated adenocarcinoma of the sarcomatoid subtype, leiomyosarcoma (LMS) that has metastasised from elsewhere (although very rare), other myogenic stromal tumours (eg, leiomyoma, tumours from myofibroblasts) and non-myogenic tumours (eg, GIST). A good quality CT, EUS and IHC can help distinguish among them; however, as our case has demonstrated a high index of suspicion is also required.

Treatment

Given the extent of splanchnic vessel invasion the tumour was deemed inoperable after multidisciplinary team (MDT) review. The patient was offered palliative chemotherapy but declined due to the associated morbidity. She consented for palliative radiotherapy and completed 54 Gy in 30 fractions with a good clinical result.

Outcome and follow-up

She is clinically well 18 months after diagnosis and 10 months post treatment. The patient reports that her symptoms have dissipated and she has more energy for day to day activities.

Discussion

Leiomyosarcoma is an exceedingly rare form of pancreatic malignancy but it is the most common of the stromal tumours of the pancreas.8 It is postulated that PLMS originates from either the walls of intrapancreatic vessels or from the smooth muscle cells of the pancreatic ducts.5 9 10 A literature search using MeSH terms pancreas*+pancreatic ± pancreas and sarcoma ± leiomyosarcoma ±*sarcoma was conducted using PubMed and Embase. Based on this search only 67 case reports have been noted, with 58 being in English. Twenty cases in the Chinese literature have been documented separately.7

PLMS appears to be more prevalent in the fifth decade of life with a higher incidence in females.5 8 It does not appear to have a preference regarding location of tumour within the pancreas, that is, body/tail versus head involvement.5 Clinical presentation is variable but may present as abdominal pain, an abdominal mass and weight loss.5 7 8

PLMS is often diagnosed at an advanced stage. A systematic review reported that 25% of patients had distant disease (lungs and liver mainly) and 19% had locally advanced disease at presentation.7 Despite this propensity to metastasise, regional lymphatic spread is rare.5 8

Currently, there are no published radiological criteria to characterise PLMS.11 Indeed, in our case the lesion was initially suggested on plain film radiograph. Following this the patient went on to have a CT scan which revealed a large head of pancreas mass. Table 1 summaries the various imaging features that have been identified in and associated with primary pancreatic leiomyosarcoma.11 12 Most commonly they are seen on CT as solid lesions with possible cystic components secondary to necrosis or haemorrhage, with contrast enhancement in both arterial and venous phases with no fat content.7 12 Given the CT findings they can be frequently misdiagnosed as pancreatic pseudocysts or cystic neoplasms.7 13

Table 1.

A summary of the features on various imaging modalities in relation to pancreatic leiomyosarcoma11 12

| Imaging modality | Features |

| Ultrasound | Small lesions—hypoechoic Large lesions—haemorrhagic or cystic |

| CT | Large lesion, heterogeneous, slightly enhancing peripherally, large central non-enhancing component. Cystic component secondary to necrosis |

| MRI | T1—isointense with skeletal muscle T2—hyperintense with heterogenous gadolinium enhancement |

A firm histological diagnosis on a biopsy specimen relies on histopathological morphology and IHC staining pattern. Characteristically, stromal tumours have well-formed fascicles of spindle cells with blunt-ended nuclei intersecting at right angles. Positive staining for SMA, desmin, h-caldesmon and HHF35 assign the mesenchymal tumour to the myogenic subgroup while excluding a myofibroblastic tumour. Negative stains for neurogenic tissue (S100) and GIST (CD117, DOG1) are required. The presence of tissue necrosis, mitosis and pleomorphism will confirm the presence of malignancy.

The published English literature from 1980 contains 50 cases of PLMS, with 21 having had biopsies. Only 19 had enough detailed information to be analysed (table 2). The biopsies were performed either via an open approach, percutaneously or by EUS/FNA. Interestingly, all non-pancreatic biopsies were positive while only 8/14 (57%) of pancreatic biopsies were positive (table 3). Three frozen sections were sent, all from the pancreas with an open approach and none were diagnostic of PLMS.

Table 2.

Published cases of pancreatic leiomyosarcoma having tissue biopsy (1980–2019)

| Year | Author | Disease location | Metastatic disease | Biopsy type | Biopsy result | Treatment | ||

| Open | Percutaneous | EUS | ||||||

| 1981 | Ishikawa et al 23 | Head | No | Pancreas | Negative | DP, CT | ||

| 1993 | Russ24 | Tail | Liver, spleen | Liver | Positive | Nil | ||

| 1994 | Ishii et al 25 | Tail | Liver | Liver | Positive | CT | ||

| 1994 | Peskova26 | Head | No | Pancreas | Negative | DP | ||

| 1998 | Chawla et al 27 | Head | Lung | Pancreas | Positive | CT | ||

| 1998 | Zalatnai et al 9 | Head | Liver | Pancreas | Positive | Bypass | ||

| 2000 | Srivastava et al 11 | Body | Peritoneum | Peritoneal nodules |

Positive | CT | ||

| 2000 | Srivastava et al 11 | Head | Lung | Pancreas | Positive | CT | ||

| 2007 | Maarouf et al 28 | Tail | No | Pancreas | Negative | DP | ||

| 2008 | Muhammed et al 29 | Body | Liver | Liver | Positive | Nil | ||

| 2010 | Riddle et al 30 | Tail | No | Pancreas | Negative | DP | ||

| 2011 | Zhang et al 31 | Body | No | Pancreas | Negative | DP | ||

| 2012 | Moletta et al 15 | Body | Liver | Liver, pancreas | Positive | DP, LH, CT | ||

| 2014 | Hebert-Magee et al 6 | Head | Peritoneum | Pancreas | Positive | Nil | ||

| 2015 | Milanetto et al 18 | Head | No | Pancreas | Negative | LE | ||

| 2016 | Reyes et al 32 | Head | Liver | Liver, pancreas |

Positive | CT | ||

| 2016 | Lin et al 2 | Body | Liver, peritoneum | Liver, peritoneum |

Positive | Nil | ||

| 2018 | Abdelfatah33 | Head | Liver | Pancreas | Positive | Nil | ||

| 2019 | Papalampros e t al 5 | Head | Liver | Pancreas | Positive | IRE | ||

CT, chemotherapy; DP, distal pancreatectomy; IRE, irreversible electroporation; LE, local excision; LH, left hemihepatectomy.

Table 3.

Summary of biopsy results during the period 1980–2019

| Biopsy site | Biopsy type | Total | Result | |

| Positive | Negative | |||

| Pancreatic | Open | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| Percutaneous | 6 | 3 | 3 | |

| EUS | 4 | 4 | 0 | |

| Non-pancreatic | Open | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Pancreatic | 3 | 3 | 0 | |

| EUS | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

The diagnosis can be made with EUS and FNA, although only four cases have demonstrated successful cytological diagnosis through this method so far.7 Although this is less invasive than operative biopsy there are issues with its use. False negative results can arise due to the cystic and fibrous nature of the lesion.2 6 Additionally, a sufficient sample must be available for a good cell block. A sufficiently large needle must be used to get a sample that will facilitate adequate assessment. A needle size of 19 gauge achieved better tissue yield.6 Otherwise, repeated sampling may be required which delays treatment and may not improve yield.2

Core biopsies are more useful as they provide larger samples. However, sarcomas are notorious for harbouring tissue heterogeneity which can make diagnosis and grading inaccurate.14

The use of frozen section in cases of PLMS is limited. Its main role is to exclude adenocarcinoma. While it can make a presumptive diagnosis of a mesenchymal tumour it cannot provide information on subtypes as it requires more detailed IHC analysis. Also, processing procedure for frozen sections can produce tissue artefacts which makes the diagnosis of a stromal tumour difficult. Larger incisional biopsies are possible by open or laparoscopic approach. They are performed in cases where curative resection is not possible and where no other metastatic deposits can be sampled. They help with diagnosis and tumour grading.

There is no standardised treatment protocol for PLMS. Current evidence suggests that operative management with complete resection of the tumour is the gold standard.5 8 15 This usually includes a pancreaticoduodenectomy or a distal pancreatectomy (DP) depending on the location. However, juxta-pancreatic resections have also been attempted for locally advanced cases. Lakhoo, documented a case requiring gastric and colonic resection with a DP, with the patient being alive without evidence of disease after 2 years.16 A synchronous left hepatectomy for a metastasis has been performed with the patient being alive with disease after 3 years, although the patient required treatment for recurrence.15 Makimoto performed five metastatectomies after aggressive resection of a locally advanced tumour.17 The patient survived 70 months after diagnosis without any adjuvant therapy. Although technically feasible options, these cases undergo potentially rigorous selection to ensure optimal patient outcome.

There is no strong evidence regarding the role of adjuvant therapy after a complete resection.18–20 In fact, a review of cases published in the English literature since 1980 shows that out of 32 patients who had resection only two had adjuvant therapy. Of the 30 patients who had no adjuvant treatment, two-thirds had no documented recurrence on follow-up. However, a combination of doxycycline and ifosfamide has been reported as an adjuvant regime with patient being disease free a year after treatment.21

Palliative treatment can be extrapolated from European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines regarding soft tissue and visceral sarcomas.22 Advanced unresected cases are offered doxorubicin (with possibility of adding ifosfamide) as first line therapy rather than gemcitabine and docetaxel. The combination of anthracyclines and olaratubmab is possible and has been reported.5 Trabectedin is used as second line agent. Palliative radiotherapy can be offered in locally advanced cases for symptom control although the local recurrence rate is still high. Doses of over 60 Gy are recommended for effect but has significant risk of local visceral injury. Hence it is not first line treatment.

Novel treatment modalities have been instigated recently. Papalampros described a case of metastatic leiomyosarcoma which was treated with irreversible electroporation of the pancreatic lesion and microwave ablation to the liver metastases.5 Transarterial chemoembolisation with doxorubicin and 5FU has been used recently to treat liver metastasis after PD.11

Prognosis is dictated by the Union for International Cancer Control Stage Classification System (eighth edition) which incorporates grading in its assessment.4 The French Federation of Cancer System grades the tumour according to tumour differentiation, mitotic count and extent of tumour necrosis, as demonstrated in table 4.3 A systematic review found that radical resection and, to a lesser extent, invasion of adjacent organs/vessels affected prognosis.7

Table 4.

Grading from French Federation of cancer system4

| Tumour differentiation | Necrosis | Mitotic count (n per 10 high power fields) |

| 1. Well | 0: Absent | 1: n<10 |

| 2. Moderate | 1:<50% | 2: 10–19 |

| 3. Poor (anaplastic) | 2:≥50% | 3: n≥20 |

The sum of the scores of the three criteria determines the grade of the malignancy.

Grade 1=2 or 3; grade 2=4 or 5; grade 3=6.

In summary this case illustrates how the strict requirements necessary to finalise the diagnosis of PLMS can be difficult to achieve especially due to shortcomings in minimally invasive diagnostic tools. Management is controversial and can be aided by the latest ESMO guidelines on visceral sarcoma.

Learning points.

Diagnosis of pancreatic leiomyosarcoma (PLMS) relies on the presence of interlacing spindle cells, positive immunohistochemical staining pattern (SMA, desmin) and malignant features (pleiomorphism, mitosis, necrosis).

Biopsy techniques employed have their limitations due to the strict requirements for making a diagnosis of PLMS.

Biopsy of extrapancreatic deposits has a higher yield than pancreatic biopsies. If pancreatic biopsy is required then an endoscopic ultrasound/fine needle aspirate with 19G needle can achieve a good yield.

Frozen section is not useful in differentiating subtypes of mesenchymal tumours.

Acknowledgments

Dr Indika Liyanage Dr Leonardo Santos.

Footnotes

Contributors: NF: conception of the work including the design, acquisition and analysis of data. Drafting and revision of the manuscript. Final approval of the submitted version. Accountable for all aspects of the work. TS: conception of the work including the design, acquisition and analysis of data. Final approval of the submitted version. Accountable for all aspects of the work. AD: Final approval of the submitted version. Accountable for all aspects of the work. KR: conception of the work including the design, acquisition and analysis of data. Final approval of the submitted version. Accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Ross CF. Leiomyosarcoma of the pancreas. Br J Surg 1951;39:53–6. 10.1002/bjs.18003915311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lin C, Wang L, Sheng J, et al. . Transdifferentiation of pancreatic stromal tumor into leiomyosarcoma with metastases to liver and peritoneum: a case report. BMC Cancer 2016;16:947 10.1186/s12885-016-2976-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Guillou L, Coindre JM, Bonichon F, et al. . Comparative study of the National cancer Institute and French Federation of cancer centers sarcoma group grading systems in a population of 410 adult patients with soft tissue sarcoma. J Clin Oncol 1997;15:350–62. 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.1.350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brierley JD, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C. Tnm classification of malignant tumours. John Wiley & Sons, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Papalampros A, Vailas MG, Deladetsima I, et al. . Irreversible electroporation in a case of pancreatic leiomyosarcoma: a novel weapon versus a rare malignancy? World J Surg Oncol 2019;17:6 10.1186/s12957-018-1553-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hébert-Magee S, Varadarajulu S, Frost AR, et al. . Primary pancreatic leiomyosarcoma: a rare diagnosis obtained by EUS-FNA cytology. Gastrointest Endosc 2014;80:361–2. 10.1016/j.gie.2014.02.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Xu J, Zhang T, Wang T, et al. . Clinical characteristics and prognosis of primary leiomyosarcoma of the pancreas: a systematic review. World J Surg Oncol 2013;11:290 10.1186/1477-7819-11-290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Singla V, Arora A, Tyagi P, et al. . Rare cause of recurrent acute pancreatitis due to leiomyosarcoma. Trop Gastroenterol 2016;37:70–2. 10.7869/tg.328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zalatnai A, Kovács M, Flautner L, et al. . Pancreatic leiomyosarcoma. Case report with immunohistochemical and flow cytometric studies. Virchows Arch 1998;432:469–72. 10.1007/s004280050193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sato T, Asanuma Y, Nanjo H, et al. . A resected case of giant leiomyosarcoma of the pancreas. J Gastroenterol 1994;29:223–7. 10.1007/BF02358688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Srivastava DN, Batra A, Thulkar S, et al. . Leiomyosarcoma of pancreas: imaging features. Indian J Gastroenterol 2000;19:187–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barral M, Faraoun SA, Fishman EK, et al. . Imaging features of rare pancreatic tumors. Diagn Interv Imaging 2016;97:1259–73. 10.1016/j.diii.2016.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Aihara H, Kawamura YJ, Toyama N, et al. . A small leiomyosarcoma of the pancreas treated by local excision. HPB 2002;4:145–8. 10.1080/136518202760388064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lin X, Davion S, Bertsch EC, et al. . Federation Nationale des centers de Lutte Contre Le cancer grading of soft tissue sarcomas on needle core biopsies using surrogate markers. Hum Pathol 2016;56:147–54. 10.1016/j.humpath.2016.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moletta L, Sperti C, Beltrame V, et al. . Leiomyosarcoma of the pancreas with liver metastases as a paradigm of multimodality treatment: case report and review of the literature. J Gastrointest Cancer 2012;43 Suppl 1:246–50. 10.1007/s12029-012-9405-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lakhoo K, Mannell A. Pancreatic leiomyosarcoma. A case report. S Afr J Surg 1991;29:59–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Makimoto S, Hatano K, Kataoka N, et al. . A case report of primary pancreatic leiomyosarcoma requiring six additional resections for recurrences. Int J Surg Case Rep 2017;41:272–6. 10.1016/j.ijscr.2017.10.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Milanetto AC, Liço V, Blandamura S, et al. . Primary leiomyosarcoma of the pancreas: report of a case treated by local excision and review of the literature. Surg Case Rep 2015;1 10.1186/s40792-015-0097-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hur YH, Kim HH, Park EK, et al. . Primary leiomyosarcoma of the pancreas. J Korean Surg Soc 2011;81 Suppl 1:S69–73. 10.4174/jkss.2011.81.Suppl1.S69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Izumi H, Okada K-ichi, Imaizumi T, et al. . Leiomyosarcoma of the pancreas: report of a case. Surg Today 2011;41:1556–61. 10.1007/s00595-010-4536-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aguilar C, Socola F, Donet JA, et al. . Leiomyosarcoma of the splenic vein. Clin Med Insights Oncol 2013;7 10.4137/CMO.S12403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Casali P, Abecassis N, Bauer S, et al. . Soft tissue and visceral sarcomas: ESMO–EURACAN clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of Oncology 2018;29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ishikawa O, Matsui Y, Aoki Y, et al. . Leiomyosarcoma of the pancreas. Report of a case and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol 1981;5:597–602. 10.1097/00000478-198109000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Russ PD. Leiomyosarcoma of the pancreatic bed detected on CT scans. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1993;161 10.2214/ajr.161.1.8517309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ishii H, Okada S, Okazaki N, et al. . Leiomyosarcoma of the pancreas: report of a case diagnosed by fine needle aspiration biopsy. Jpn J Clin Oncol 1994;24:42–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Peskova M, Fried M. Pancreatic tumor of mesenchymal origin--an unusual surgical finding. Hepatogastroenterology 1994;41:201–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chawla S, Gairola M, Nachiappan PL, et al. . Pancreatic leiomyosarcoma in a middle-aged lady. Trop Gastroenterol 1998;19:118–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Maarouf A, Scoazec J-Y, Berger F, et al. . Cystic leiomyosarcoma of the pancreas successfully treated by splenopancreatectomy: a 20-year follow-up. Pancreas 2007;35:95–8. 10.1097/01.mpa.0000278689.86306.70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Muhammad SUI, Azam F, Zuzana S. Primary pancreatic leiomyosarcoma: a case report. Cases J 2008;1:280 10.1186/1757-1626-1-280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Riddle ND, Quigley BC, Browarsky I, et al. . Leiomyosarcoma arising in the pancreatic duct: a case report and review of the current literature. Case Rep Med 2010;2010:1–4. 10.1155/2010/252364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang Q-Y, Shen Q-Y, Yan S, et al. . Primary pancreatic pleomorphic leiomyosarcoma. J Int Med Res 2011;39:1555–62. 10.1177/147323001103900447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Reyes MCD, Huang X, Bain A, et al. . Primary pancreatic leiomyosarcoma with metastasis to the liver diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration and fine needle biopsy: a case report and review of literature. Diagn Cytopathol 2016;44:1070–3. 10.1002/dc.23540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Abdelfatah M, Gochanour EM. Leiomyosarcoma involving the pancreas diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound fine-needle aspiration. J Gastrointest Cancer 2018;49:340–2. 10.1007/s12029-016-9910-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]