Abstract

Background

Ischaemic heart disease including heart failure is the most common cause of death in the world, and the incidence of the condition is rapidly increasing. Heart failure is characterised by symptoms such as fatigue and breathlessness during light activity, as well as disordered breathing during sleep. In particular, sleep disordered breathing (SDB), including central sleep apnoea (CSA) and obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA), is highly prevalent in people with chronic heart failure. A previous meta‐analysis demonstrated that positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy dramatically increased the survival rate of people with heart failure who had CSA, and thus could contribute to improving the prognosis of these individuals. However, recent trials found that adaptive servo‐ventilation (ASV) including PAP therapy had a higher risk of all‐cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality. A meta‐analysis that included recent trials was therefore needed.

Objectives

To assess the effects of positive airway pressure therapy for people with heart failure who experience central sleep apnoea.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, Embase, and Web of Science Core Collection on 7 February 2019 with no limitations on date, language, or publication status. We also searched two clinical trials registers in July 2019 and checked the reference lists of primary studies.

Selection criteria

We excluded cross‐over trials and included individually randomised controlled trials, reported as full‐texts, those published as abstract only, and unpublished data.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted outcome data from the included studies. We double‐checked that data had been entered correctly by comparing the data presented in the systematic review with study reports. We analysed dichotomous data as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and continuous data as mean difference (MD) or standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% CIs. Furthermore, we performed subgroup analysis in the ASV group or continuous PAP group separately. We used GRADEpro GDT software to assess the quality of evidence as it relates to those studies that contribute data to the meta‐analyses for the prespecified outcomes.

Main results

We included 16 randomised controlled trials involving a total of 2125 participants. The trials evaluated PAP therapy consisting of ASV or continuous PAP therapy for 1 to 31 months. Many trials included participants with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Only one trial included participants with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.

We are uncertain about the effects of PAP therapy on all‐cause mortality (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.21; participants = 1804; studies = 6; I2 = 47%; very low‐quality evidence). We found moderate‐quality evidence of no difference between PAP therapy and usual care on cardiac‐related mortality (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.24; participants = 1775; studies = 5; I2 = 11%). We found low‐quality evidence of no difference between PAP therapy and usual care on all‐cause rehospitalisation (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.30; participants = 1533; studies = 5; I2 = 40%) and cardiac‐related rehospitalisation (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.35; participants = 1533; studies = 5; I2 = 40%). In contrast, PAP therapy showed some indication of an improvement in quality of life scores assessed by all measurements (SMD −0.32, 95% CI −0.67 to 0.04; participants = 1617; studies = 6; I2 = 76%; low‐quality evidence) and by the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MD −0.51, 95% CI −0.78 to −0.24; participants = 1458; studies = 4; I2 = 0%; low‐quality evidence) compared with usual care. Death due to pneumonia (N = 1, 3% of PAP group); cardiac arrest (N = 18, 3% of PAP group); heart transplantation (N = 8, 1% of PAP group); cardiac worsening (N = 3, 9% of PAP group); deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism (N = 1, 3% of PAP group); and foot ulcer (N = 1, 3% of PAP group) occurred in the PAP therapy group, whereas cardiac arrest (N = 16, 2% of usual care group); heart transplantation (N = 12, 2% of usual care group); cardiac worsening (N = 5, 14% of usual care group); and duodenal ulcer (N = 1, 3% of usual care group) occurred in the usual care group across three trials.

Authors' conclusions

The effect of PAP therapy on all‐cause mortality was uncertain. In addition, although we found evidence that PAP therapy did not reduce the risk of cardiac‐related mortality and rehospitalisation, there was some indication of an improvement in quality of life for heart failure patients with CSA. Furthermore, the evidence was insufficient to determine whether adverse events were more common with PAP than with usual care. These findings were limited by low‐ or very low‐quality evidence. PAP therapy may be worth considering for individuals with heart failure to improve quality of life.

Plain language summary

Positive airway pressure for heart failure associated with central sleep apnoea

Background

Ischaemic heart disease including heart failure is the most common cause of death in the world, and the incidence of the condition is rapidly increasing. Heart failure is characterised by symptoms such as fatigue and breathlessness during light activity, as well as disordered breathing during sleep. In particular, sleep disordered breathing, including central sleep apnoea (CSA) and obstructive sleep apnoea, is highly prevalent in people with chronic heart failure.

Purpose: to assess the effects of positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy for people with heart failure who experience CSA.

Methods

We searched the scientific literature for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (a type of study in which participants are assigned to one of two or more treatment groups by means of a random method) that compared the effectiveness of PAP therapy versus usual care in people with heart failure who experience CSA. PAP therapy consisted of continuous PAP and adaptive servo‐ventilation, and usual care consisted of medical therapy based on relevant guidelines. The evidence is current to February 2019.

Results

We included 16 RCTs involving a total of 2125 participants. The effect of PAP therapy on on all‐cause mortality was uncertain. In addition, PAP therapy did not reduce cardiac‐related mortality, all‐cause rehospitalisation, and cardiac‐related rehospitalisation compared with usual care. However, PAP therapy showed some indication of an improvement in quality of life scores. Death due to pneumonia (N = 1, 3% of PAP group); cardiac arrest (N = 18, 3% of PAP group); heart transplantation (N = 8, 1% of PAP group); cardiac worsening (N = 3, 9% of PAP group); deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism (N = 1, 3% of PAP group); and foot ulcer (N = 1, 3% of PAP group) were observed in the PAP therapy group, whereas cardiac arrest (N = 16, 2% of usual care group); heart transplantation (N = 12, 2% of usual care group); cardiac worsening (N = 5, 14% of usual care group); and duodenal ulcer (N = 1, 3% of usual care group) occurred in the usual care group across three trials.

Quality of the evidence

We assessed the the quality of evidence for many outcomes including cardiac‐related rehospitalisation as low or very low because variability among studies (heterogeneity) was high, a range of confidence intervals was wide, and random sequence generation and blinding of participants and personnel were poorly described.

Conclusion

The effect of PAP therapy on all‐cause mortality was uncertain. In addition, although PAP therapy did not reduce the risk of cardiac‐related mortality and rehospitalisation, there was some indication of an improvement in quality of life score for heart failure patients with CSA. Furthermore, the evidence was insufficient to determine whether adverse events were more common with PAP than with usual care. These findings were limited by low‐ or very low‐quality evidence. PAP therapy may be worth considering for individuals with heart failure to improve quality of life.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. PAP therapy compared to usual care for heart failure associated with central sleep apnoea.

| Patient or population: heart failure associated with central sleep apnoea Setting: in the hospital and home based Intervention: PAP therapy Comparison: usual care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with usual care | Risk with PAP therapy | |||||

| All‐cause mortality follow‐up: range 3 to 80 months | Study population | RR 0.81 (0.54 to 1.21) | 1804 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 1 2 3 | ||

| 430 per 1000 | 348 per 1000 (232 to 520) | |||||

| Cardiac‐related mortality follow‐up: range 3 to 80 months | Study population | RR 0.97 (0.77 to 1.24) | 1775 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate 1 | The largest trial weighed 44.7% in the analysis (SERVE‐HF 2015). | |

| 349 per 1000 | 338 per 1000 (269 to 433) | |||||

| All‐cause rehospitalisation follow‐up: range 1 to 80 months | Study population | RR 0.95 (0.70 to 1.30) | 1533 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low 1 3 | The largest trial weighed 58.1% in the analysis (SERVE‐HF 2015). | |

| 643 per 1000 | 610 per 1000 (450 to 835) | |||||

| Cardiac‐related rehospitalisation follow‐up: range 1 to 80 months | Study population | RR 0.97 (0.70 to 1.35) | 1533 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low 1 3 | The largest trial weighed 55.8% in the analysis (SERVE‐HF 2015). | |

| 411 per 1000 | 399 per 1000 (288 to 555) | |||||

| QOL assessed with: all measurements follow‐up: range 3 to 31 months | ‐ | SMD 0.32 lower (0.67 lower to 0.04 higher) | ‐ | 1617 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low 1 2 | A lower score means better QOL. |

| QOL: Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ) (points) scale from 0 to 105 follow‐up: range 3 to 80 months | The mean change in MLHFQ score was −2.3 points from baseline. | The mean change in MLHFQ score was −8.1 points from baseline. MD 0.51 lower (0.78 lower to 0.24 lower) |

‐ | 1458 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low 1 2 | A lower score means better QOL. The largest trial weighed 99.8% in the analysis (SERVE‐HF 2015). |

| Adverse events follow‐up: range 1 month to 80 months | 1 trial involving 63 participants reported death due to pneumonia (N = 1, 3%), cardiac worsening (N = 3, 9%), deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism (N = 1, 3%), and foot ulcer (N = 1, 3%) in the PAP therapy group, whilst cardiac worsening (N = 5, 14%) and duodenal ulcer (N = 1, 3%) were reported in the usual care group (Arzt 2013). Another trial involving 24 participants reported no adverse events with PAP therapy, and cardiac arrest (N = 1, 8%) and heart transplantation (N = 1, 8%) in the usual care group (Naughton 1995a). The third trial involving 1349 participants reported cardiac arrest (N = 18, 3%) and heart transplantation (N = 8, 1%) in the PAP therapy group, and cardiac arrest (N = 16, 2%) and heart transplantation (N = 12, 2%) in the usual care group (SERVE‐HF 2015). | ‐ | 1412 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low 1 3 | ||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; PAP: positive airway pressure; QOL: quality of life; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1Downgraded one level as random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, or selective reporting were poorly described in over 50% of the included studies. 2Downgraded one level because heterogeneity was more than 40%. 3Downgraded one level because the 95% confidence intervals was very wide.

Background

Description of the condition

Ischaemic heart disease including heart failure is the most common cause of death in the world, with an incidence of 8.76 million deaths in 2015 according to Global Health Observatory data reported by the World Health Organization (WHO 2017). Furthermore, global prevalence of heart failure was reported at approximately 40 million by the Global Burden of Disease study (GBD 2016). The incidence of heart failure has increased dramatically over the past few decades and is expected to continue to rise over the next 20 years (Mozaffarian 2015; Okura 2008). Defined as a clinical syndrome characterised by symptoms and signs stemming from a structural or functional cardiac abnormality, or both, heart failure occurs in approximately 2% of adults and in more than 10% of elderly people (Mosterd 2007; Ponikowski 2016). About 30% to 40% of individuals survive for one year after onset of heart failure, and rates of hospital readmission and cardiac events are very high (Mozaffarian 2015). Heart failure consists of two subcategories: heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). The left ventricular ejection fraction in HFrEF and HFpEF is less than 40% and greater than 50%, respectively (Ponikowski 2016). Individuals with left ventricular ejection fraction in the range of 40% to 49% represent a grey area (Ponikowski 2016). Individuals with HFrEF are reported as having a 32% higher risk of mortality compared with those with HFpEF (MAGGIC 2012).

Symptoms of heart failure include fatigue and breathlessness during light activity, as well as disordered breathing during sleep. In particular, approximately 30% to 40% of people with heart failure experience sleep‐disordered breathing (SDB), including obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) and central sleep apnoea (CSA) (Javaheri 1998; Sin 1999; Wang 2007). OSA and CSA are associated with a worse prognosis in heart failure (Ponikowski 2016). OSA is caused mainly by narrowing or occlusion of the upper airway due to obesity and reportedly occurs in 38% of men and 31% of women with heart failure (Sin 1999). CSA, the most common form of SDB among those with HFrEF, reportedly occurs in 25% to 40% of individuals with HFrEF (Lévy 2007; McKelvie 2011). CSA is reportedly caused by low cardiac output, high sympathetic activation, and pulmonary congestion (Naughton 2017). SDB leads to hypertension through sympathetic activation, intrinsic endothelial dysfunction, and pressor effects of vasoactive peptides that sustain elevated blood pressure (Kasai 2012; Shahar 2001; Yoshihisa 2013b). Furthermore, these conditions independently increase the risk of cardiovascular mortality and decrease quality of life (QOL) for people with CSA (Bradley 2005; Carmona 2008). One meta‐analysis revealed that risk of mortality among people with heart failure and CSA was 1.48 times higher than in people with heart failure without SDB (Nakamura 2015). In addition, European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines recommend improving QOL in people with heart failure, which means alleviating symptoms and improving well‐being (Ponikowski 2016).

Three previous studies reported that positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy such as continuous PAP (CPAP), bilevel PAP (BiPAP), and adaptive servo‐ventilation (ASV) improved hypopnoea, SDB, cardiac function, haemodynamic status, and QOL (Bradley 2005; Mansfield 2004; Yoshihisa 2013b). Furthermore, PAP therapy was shown to dramatically increase the survival rate of people with heart failure who had CSA, and thus could contribute to improving the prognosis of these individuals (Nakamura 2015; Yoshihisa 2013b).

Description of the intervention

Positive airway pressure therapy is a physical treatment in which patients wear a nasal or facial mask during sleep. The airstream blown through the mask acts as a pneumatic splint and keeps the airway open, thus lowering the risk of blocked airways, which can cause hypertension through sympathetic activation, and increasing endothelial dysfunction and pressor effects of vasoactive peptides. ESC guidelines recommend PAP therapy to improve outcomes caused by SDB, especially OSA for people with heart failure (Ponikowski 2016). However, ASV in PAP therapy is not recommended for people who have HFrEF and CSA (Ponikowski 2016). In one meta‐analysis by Nakamura, ASV in PAP therapy reduced all‐cause mortality (risk ratio 0.13, 95% confidence interval 0.02 to 0.95) amongst people with heart failure who had CSA, whereas CPAP was not associated with changes in mortality rate (Nakamura 2015).

How the intervention might work

Use of PAP therapy for people with heart failure and SDB has been reported to decrease the frequency of episodes of sleep apnoea and hypopnoea and to improve cardiac function and exercise capacity (Bradley 2005). For this reason, PAP improves pulmonary congestion by reopening collapsed alveoli, increasing lung volume, preventing peripheral airway occlusion, improving oxygenation and lung compliance, and reducing cardiac preload through reduced venous return (Mehta 2001; Naughton 1995b; Naughton 2017; Takano 1986). PAP therapy should therefore be considered for people with respiratory distress (class of recommendation ‐ IIa; level of evidence ‐ B) according to the ESC guideline (Ponikowski 2016).

Why it is important to do this review

PAP therapy is reportedly effective for people with OSA when provided according to available guidelines (Randerath 2012; Yumino 2013), therefore it may be considered to treat nocturnal hypoxaemia in OSA (Randerath 2012; Yumino 2013). However, the effectiveness of PAP therapy for people with heart failure who have CSA is unclear. The Treatment of Predominant Central Sleep Apnoea by Adaptive Servo Ventilation in Patients With Heart Failure (SERVE‐HF) trial, which was conducted in 11 countries and investigated the effects of ASV on survival and cardiovascular outcomes of people with HFrEF and CSA, reported that the ASV group had an almost 1.3 times higher risk of all‐cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality than the control group (Cowie 2015). In light of the results of this trial, the ESC guideline has suggested that ASV is not recommended for HFrEF and predominantly CSA. However, the Study of the Effects of Adaptive Servo‐ventilation Therapy on Cardiac Function and Remodeling in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure (SAVIOR‐C) trial, which was conducted in Japan and investigated the effects of ASV in HFrEF regardless of CSA, reported no significant differences in cardiovascular events between ASV and control groups (Momomura 2015). Furthermore, clinical composite response, New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification, and symptoms during daily activities showed greater improvement in the ASV group than in the control group. As results of these and other trials differed, the effectiveness of PAP for people with heart failure and CSA remains unclear. This review aimed to determine the benefits and harms of PAP therapy for people with heart failure who have CSA.

Objectives

To assess the effects of positive airway pressure therapy for people with heart failure who experience central sleep apnoea.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included individually randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Cluster‐RCTs were eligible for inclusion, however none were identified. We excluded cross‐over trials and included full‐text studies, studies for which only the abstract was published, and unpublished data.

Types of participants

We included participants 18 years of age or older with a diagnosis of heart failure with CSA. We included HFrEF and HFpEF. We planned that if a study included only a subset of eligible participants, we would ask the study authors to provide data on the subset of interest; if we could not obtain data for the subset of eligible participants, we would have excluded them from the analysis and categorised them as studies awaiting classification. We defined CSA by polysomnography and fulfilment of the following criteria: apnea‐hypopnea index ≥ 5 events per hour and 3% of oxygen desaturation index ≥ 5 events per hour. We excluded participants with an implantable ventricular assist device and those who underwent heart transplantation.

Types of interventions

We included trials comparing PAP (CPAP, BiPAP, or ASV) therapy versus usual care consisting of medical therapy based on relevant guidelines (Hunt 2009; McMurray 2012). Standard mechanical settings are used for PAP therapy, and expiratory positive airway pressure can be increased manually to manage sleep apnoea. Participants were asked to use the PAP device for three hours per night on average to ensure the efficacy of PAP therapy (Cowie 2015).

Types of outcome measures

We assessed all outcome measures and clinical events after randomisation.

Primary outcomes

All‐cause mortality

Cardiovascular (cardiac‐related) mortality

All‐cause rehospitalisations

Cardiac‐related rehospitalisation: defined as total number of rehospitalisations

Health‐related quality of life as assessed by validated questionnaires

Adverse events (PAP device‐related and non‐device‐related): defined as total number of adverse events

Secondary outcomes

SDB markers: apnea‐hypopnea index, respiratory disturbance index, and oxygen desaturation index

Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular function markers: blood pressure, echocardiography, and left ventricular ejection fraction

Physical function markers: exercise capacity, 6‐minute walking distance, and NYHA classification

Reporting one or more of the outcomes listed above was not an inclusion criterion for this review.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We identified trials through systematic searches of the following bibliographic databases on 7 February 2019:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), in the Cochrane Library (Issue 2 of 12, 2019);

Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, MEDLINE Daily and MEDLINE (Ovid, 1946 to 5 February 2019);

Embase (Ovid, 1980 to 2019 week 5);

Web of Science Core Collection (Clarivate Analytics, 1900 to 6 February 2019).

We adapted the search strategy devised for MEDLINE (Appendix 1) for use in the searches of other databases. We applied the Cochrane sensitivity‐maximising randomised controlled trial filter to MEDLINE (Ovid) searches, and adaptations of it to the searches of the other databases, except CENTRAL (Lefebvre 2011). See Appendix 1 for all of the search strategies used.

We conducted searches of the US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (apps.who.int/trialsearch/) on 1 July 2019. We searched all databases from their inception to the present, regardless of language of publication or publication status.

We did not perform a separate search for adverse effects of interventions used for treatment of CSA. We only considered adverse effects described in the included studies.

Searching other resources

We checked reference lists of all primary studies and review articles for additional references. We contacted experts in the field and asked if they knew of any ongoing or unpublished trials. We also examined any relevant retraction statements and errata for included studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (SY and TY) independently screened titles and abstracts of all studies identified by the search for potential eligibility, coding them as 'retrieve' (eligible or potentially eligible/unclear) or 'do not retrieve'. If disagreements arose, we asked a third review author (KN) to arbitrate. We retrieved the full‐text versions of study reports, and three review authors (SY, TY, and KN) independently screened these for inclusion in the review, and identified and recorded reasons for the exclusion of ineligible studies. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion or by consulting other review authors (CN and RM) when necessary. We identified and excluded duplicates and collated multiple reports of the same study so that each study, rather than each report, was the unit of interest in the review. We recorded the selection process in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram and 'Characteristics of excluded studies' tables.

Data extraction and management

We used a data collection form that had been piloted on at least one study in the review to record study characteristics and outcome data. Two review authors (SY and TY) extracted the following study characteristics from the included studies:

Methods: study design, total study period, details of any 'run‐in' period, number of study centres and locations, study setting, and study date;

Participants: numbers of participants who were randomised, who withdrew or were lost to follow‐up, and who were analysed; mean age, age range, gender, severity of condition, diagnostic criteria, baseline lung function, smoking history, inclusion criteria, and exclusion criteria;

Interventions: intervention, comparison, concomitant medications, and excluded medications;

Outcomes: primary and secondary outcomes specified and collected, and time points reported;

Notes: funding for trial, and notable conflicts of interest of trial authors.

Two review authors (SY and TY) independently extracted outcome data from the included studies. Any disagreements were resolved by reaching consensus or by involving a third review author (KN) when necessary. One review author (SY) transferred data into Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014). We double‐checked that data had been entered correctly by comparing the data presented in the systematic review against the study reports. A second review author (TY) spot‐checked study characteristics against trial reports for accuracy.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Three review authors (SY, TY, and KN) independently assessed risk of bias for each study per the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Any disagreements were resolved by discussion or by consultation with other review authors (CN and RM). We assessed risk of bias according to the following domains.

Random sequence generation

Allocation concealment

Blinding of participants and personnel

Blinding of outcome assessment

Incomplete outcome data

Selective outcome reporting

Other bias

We graded each potential source of bias as high, low, or unclear and provided a quote from the study report together with a justification for our judgement in the 'Risk of bias' table. We summarised 'Risk of bias' judgements across different studies for each of the listed domains. When information on risk of bias related to unpublished data or to correspondence with a trialist, we noted this in the 'Risk of bias' table.

When considering treatment effects, we considered risk of bias that might have affected a given outcome. Note that given the nature of PAP therapy, study participants and staff could not be blinded.

Assessment of bias in conducting the systematic review

We conducted the review according to its published protocol and reported any deviations from it in the Differences between protocol and review section of the systematic review.

Measures of treatment effect

We expressed dichotomous data as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For continuous variables, we compared net changes (i.e. intervention group value minus control group value). For each trial, we ascertained the mean change (and standard deviation (SD)) in outcomes between baseline and follow‐up for both PAP therapy and control groups; if this information was unavailable, we used the absolute mean (and SD) outcome at follow‐up for both groups. We expressed the results as mean differences (MDs). For studies employing a different scale or measurement system, we used standardised mean differences (SMDs).

Unit of analysis issues

We included only individually randomised trials and synthesised the relevant information. Cluster‐RCTs were eligible for inclusion, however none were identified. Had we included cluster‐RCTs, we would have followed the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Dealing with missing data

We contacted investigators or study sponsors to verify key study characteristics and to obtain missing numerical outcome data when possible (e.g. when a study was identified as an abstract only). When this was not possible, and missing data were thought to introduce serious bias, we explored the impact of including such studies in the overall assessment of results by performing a sensitivity analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We visually inspected forest plots for signs of heterogeneity and evaluated heterogeneity qualitatively by comparing the characteristics of included studies. We used I2 and Chi2 statistics to quantitatively measure heterogeneity amongst the trials in each analysis. If we identified substantial heterogeneity (i.e. I2 > 50% and P < 0.05), we reported this and explored possible causes by conducting prespecified subgroup analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

If we were able to pool more than 10 trials, we would create and examine a funnel plot to explore possible small‐study biases for primary outcomes. If we suspected publication bias, we would carry out a simulation to investigate possible small‐study effects.

Data synthesis

We undertook meta‐analysis only when this was meaningful (i.e. when treatments, participants, and the underlying clinical question were similar enough for pooling to make sense). Furthermore, we have narratively reported non‐device‐related adverse events. We pooled data from each study using random‐effects modelling when appropriate. To examine the robustness of results, we performed meta‐analyses using fixed‐effect models after attributing less weight to small trials and compared fixed‐effect pooled estimates or 95% CIs versus random‐effects pooled estimates or 95% CIs. We performed meta‐analyses using fixed‐effect models except where we identified statistical heterogeneity (I2 > 50%), when we used a random‐effects model (Higgins 2011).

'Summary of findings' table

We created a 'Summary of findings' table using the following outcomes.

All‐cause mortality

Cardiovascular (cardiac‐related) mortality

All‐cause rehospitalisations

Cardiac‐related rehospitalisations

Health‐related quality of life (all measurements)

Adverse events

We used the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias) to assess the quality of a body of evidence as it relates to studies that contribute data to meta‐analyses for the prespecified outcomes (Guyatt 2008). We used the methods and recommendations described in Section 8.5 and Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, employing GRADEpro GDT software (GRADEpro GDT; Higgins 2011). We justified all decisions to downgrade the quality of studies by using footnotes, and made comments to aid the readers' understanding of the review when necessary.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We performed the following subgroup analysis on all outcomes: CPAP, BiPAP, or ASV therapy.

Furthermore, we planned to carry out the following subgroup analyses for primary outcomes if an I2 > 50% was obtained:

Age (≤ 65 years or > 65 years);

Sex (male and female);

Left ventricular ejection fraction (≤ 45% or > 45%);

Apnea‐hypopnea index (< 15/h or ≥ 15/h);

Cheyne‐Stokes breathing (yes or no);

Follow‐up (≤ 1 year or > 1 year).

We used the formal test for subgroup interactions available in Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014).

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to carry out a sensitivity analysis for primary outcomes to determine if high risk of bias of some included studies affected the study results. We defined 'high risk' in terms of random sequence generation, inadequate allocation concealment, and studies with missing data of greater than 20% (Tierney 2005). We planned to carry out the following sensitivity analyses.

Exclusion of studies at high risk of bias

Exclusion of trials with 10 or fewer events

Exclusion of cluster‐RCTs

Comparing fixed‐effect pooled estimates or 95% CIs versus random‐effects pooled estimates or 95% CIs

Reaching conclusions

We based our conclusions only on findings from the quantitative or narrative synthesis of studies included in this review. We avoided making recommendations for practice, and our implications for research suggest priorities for future investigation and outline remaining uncertainties in the area.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies

Results of the search

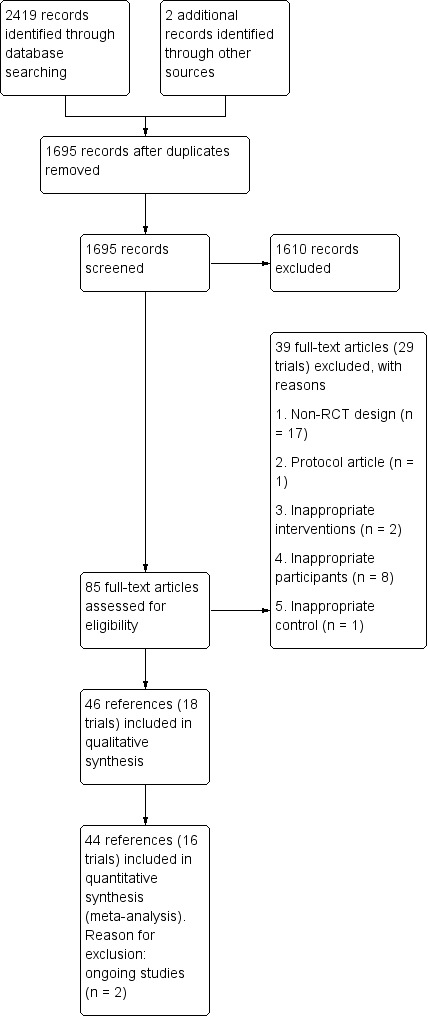

We identified a total of 1695 records after removal of duplicates, and retrieved 85 records after screening of titles and abstracts (Figure 1). We further excluded 39 of the remaining records (29 trials): 17 studies were non‐randomised; 1 study was a protocol article; 2 studies had inappropriate interventions; 8 studies had inappropriate participants; and 1 study included an inappropriate control. A total of 18 trials (46 references) met the eligibility criteria of this review. We included a total of 16 trials (44 references) in the analysis as 2 trials were ongoing studies.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We included 16 trials (44 references) with a total of 2125 participants in the review. Many trials included participants with HFrEF. Only one trial included participants with HFpEF (Yoshihisa 2013a). The majority of studies were conducted in Europe, Canada, and Japan. Furthermore, three multicentre trials were performed in Europe, Canada, and the United States (CANPAP 2005; CAT‐HF 2017; SERVE‐HF 2015). The largest trial, SERVE‐HF 2015, contributed about 60% (1325 participants) of all included participants. The mean age of participants in most studies ranged from 60 to 70 years. Ninty‐two per cent of recruited participants were men. The included trials evaluated mortality, rehospitalisation, adverse events, QOL, apnea–hypopnea index (AHI), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification, and 6‐minute walking distance. Many trials evaluated LVEF. PAP therapy was CPAP or ASV therapy. Details of the included studies are provided in the Characteristics of included studies section.

Excluded studies

We excluded 39 references (29 trials) for reasons provided in the Characteristics of excluded studies section. Many studies were excluded because they were not RCTs.

Risk of bias in included studies

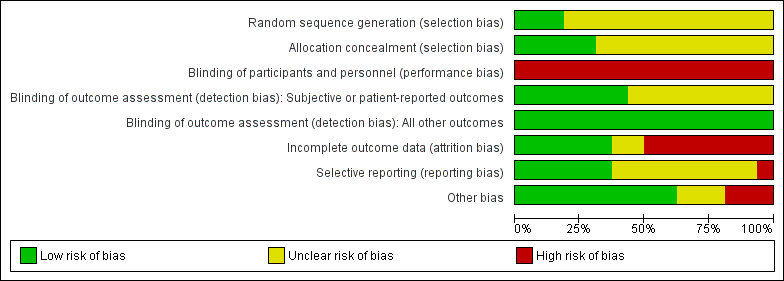

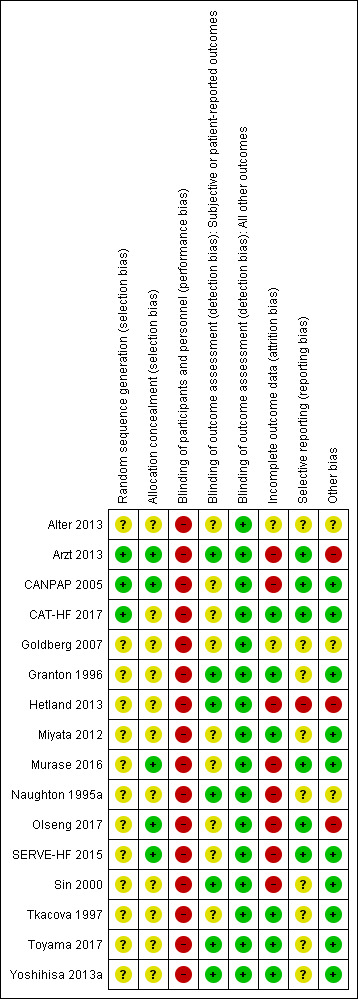

'Risk of bias' assessments are indicated in Characteristics of included studies, Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

All trials described RCTs. However, many trials reported insufficient detail to permit an assessment of the methods of random sequence generation and allocation concealment. A total of 3 out of 16 (19%) trials reported sufficient detail on random sequence generation (Arzt 2013; CANPAP 2005; CAT‐HF 2017), and 2 out of 16 (13%) trials reported sufficient detail on the methods of allocation concealment (Arzt 2013; CANPAP 2005).

Blinding

Blinding of participants and personnel

All participants were divided into PAP therapy and usual care groups, and were instructed not to discuss their intervention. Due to the nature of the PAP therapy, blinding was not possible.

Blinding of outcome assessment

We separated subjective or patient‐reported outcomes (e.g. QOL and 6‐minute walking distance) from objective outcomes such as mortality.

The assessors were blinded in half (7 out of 16; 44%) of the trials for subjective or patient‐reported outcomes (Arzt 2013; Granton 1996; Hetland 2013; Naughton 1995a; Sin 2000; Toyama 2017; Yoshihisa 2013a). As the events and the evaluation of cardiovascular function markers were not affected by outcome assessors, we considered all studies

to be at low risk of detection bias for this outcome.

Incomplete outcome data

The dropout rate in the trials was relatively high, ranging from 6% to 44%. Two trials did not report details on dropout or loss to follow‐up (Alter 2013; Goldberg 2007). Follow‐up of 90% or more was achieved in 5 out of 16 (31%) trials (Granton 1996; Miyata 2012; Tkacova 1997; Toyama 2017; Yoshihisa 2013a).

Selective reporting

Half (7 out of 16; 44%) of trials reported all outcomes listed in a clinical trial registry or protocol paper (Arzt 2013; CANPAP 2005; CAT‐HF 2017; Hetland 2013; Murase 2016; Olseng 2017; SERVE‐HF 2015). We did not find trial registries or protocol papers for the remaining trials, which we assessed as at unclear risk of reporting bias (Alter 2013; Goldberg 2007; Granton 1996; Miyata 2012; Naughton 1995a; Sin 2000; Tkacova 1997; Toyama 2017; Yoshihisa 2013a).

Other potential sources of bias

There was a difference in participant characteristics at baseline between groups in one trial (Arzt 2013). Two out of 16 (13%) trials performed a per‐protocol analysis (Hetland 2013; Olseng 2017). Furthermore, half (8 out of 16; 50%) of the trials received external funds from industry sponsors (Arzt 2013; CANPAP 2005; CAT‐HF 2017; Hetland 2013; Murase 2016; Olseng 2017; SERVE‐HF 2015; Tkacova 1997). Three out of 16 (19%) trials received funds from government agencies or public institutions (Granton 1996; Naughton 1995a; Sin 2000).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

See: Table 1, Table 2, and Table 3

1. Subgroup analysis.

| Outcome | Subscale | Subgroups | Included studies | Heterogeneity | MD (95% CI) | Test for subgroup differences |

| Quality of life | All measurements | ≤ 65 years | CAT‐HF 2017; Naughton 1995a | Tau2 = 3.17; I2 = 95% | −1.08 (−3.62, 1.45) | Chi2 = 0.46, df = 1 (P = 0.50), I2 = 0% |

| > 65 years | Arzt 2013; CAT‐HF 2017; Murase 2016; Olseng 2017; SERVE‐HF 2015 | Tau2 = 0.00; I2 = 0% | −0.21 (−0.31, −0.10) | |||

| ≤ 1 year | Arzt 2013; CAT‐HF 2017; Murase 2016; Naughton 1995a; Olseng 2017 | Tau2 = 0.34; I2 = 80% | −0.45 (−1.04, 0.14) | Chi2 = 0.67, df = 1 (P = 0.41), I2 = 0% | ||

| > 1 year | SERVE‐HF 2015 | Not applicable | −0.20 (−0.31, −0.09) |

CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference

2. Sensitivity analysis.

| Outcome | Sensitivity analysis | Heterogeneity | RR, MD, or SMD (95% CI) | |

| All‐cause mortality | Included all studies (random‐effects) | Tau2 = 0.09; I2 = 47% | 0.81 (0.54, 1.21) | |

| Exclusion of studies at high risk of bias | Excluded Hetland 2013 and Sin 2000 | Tau2 = 0.00; I2 = 5% | 1.04 (0.90, 1.22) | |

| Exclusion of trials with 10 or fewer events | Excluded Hetland 2013 and Yoshihisa 2013a | Tau2 = 0.04; I2 = 41% | 0.92 (0.67, 1.27) | |

| Fixed‐effect | Chi2 = 9.49; I2 = 47% | 1.02 (0.92, 1.12) | ||

| Cardiac‐related mortality | Included all studies (random‐effects) | Tau2 = 0.01; I2 = 11% | 0.97 (0.77, 1.24) | |

| Exclusion of studies at high risk of bias | Excluded Hetland 2013 | Tau2 = 0.00; I2 = 0% | 1.03 (0.91, 1.16) | |

| Exclusion of trials with 10 or fewer events | Excluded Hetland 2013 and Yoshihisa 2013a | Tau2 = 0.00; I2 = 0% | 1.03 (0.91, 1.17) | |

| Fixed‐effect | Chi2 = 4.48; I2 = 11% | 1.01 (0.89, 1.14) | ||

| All‐cause rehospitalisations | Included all studies (random‐effects) | Tau2 = 0.04; I2 = 40% | 0.95 (0.70, 1.30) | |

| Exclusion of studies at high risk of bias | Excluded Naughton 1995a | Tau2 = 0.05; I2 = 48% | 0.97 (0.70, 1.36) | |

| Exclusion of trials with 10 or fewer events | Excluded Miyata 2012, Naughton 1995a, and Yoshihisa 2013a | Tau2 = 0.00; I2 = 0% | 1.00 (0.93, 1.08) | |

| Fixed‐effect | Chi2 = 6.66; I2 = 40% | 0.99 (0.92, 1.06) | ||

| Cardiac‐related rehospitalisations | Included all studies (random‐effects) | Tau2 = 0.05; I2 = 40% | 0.97 (0.70, 1.35) | |

| Exclusion of studies at high risk of bias | Excluded Naughton 1995a | Tau2 = 0.05; I2 = 48% | 1.00 (0.71, 1.41) | |

| Exclusion of trials with 10 or fewer events | Excluded Miyata 2012, Naughton 1995a, and Yoshihisa 2013a | Tau2 = 0.00; I2 = 0% | 1.06 (0.94, 1.19) | |

| Fixed‐effect | Chi2 = 6.67; I2 = 40% | 1.02 (0.91, 1.15) | ||

| QOL: all measurements |

Included all studies (random‐effects) |

Tau2 = 0.13; I2 = 76% | −0.32 (−0.67, 0.04) | |

| Exclusion of studies at high risk of bias | Excluded Murase 2016 and Olseng 2017 | Tau2 = 0.18; I2 = 85% | −0.42 (−0.91, 0.07) | |

| Fixed‐effect |

Chi2 = 20.48; I2 = 76% | −0.20 (−0.29, −0.10) | ||

| QOL: Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire |

Included all studies (random‐effects) |

Tau2 = 0.0; I2 = 0% | −0.51 (−0.78, −0.24) | |

| Exclusion of studies at high risk of bias | Excluded Murase 2016 and Olseng 2017 | Tau2 = 11.04; I2 = 44% | −2.06 (−7.82, 3.70) | |

| Fixed‐effect |

Chi2 = 2.41; I2 = 0% | −0.51 (−0.78, −0.24) | ||

CI: confidence interval

MD: mean difference

QOL: quality of life

RR: risk ratio

SMD: standardised mean difference

Primary outcomes

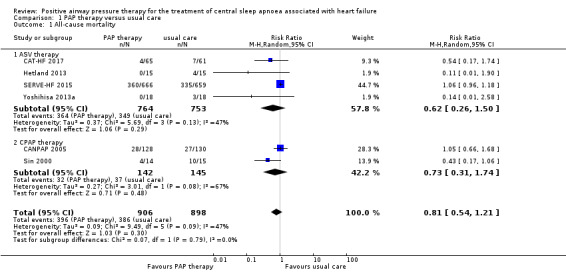

All‐cause mortality

Six trials involving 1804 participants reported all‐cause mortality (Analysis 1.1). We found that the effect of PAP therapy on all‐cause mortality was uncertain when comparing PAP therapy with usual care (risk ratio (RR) 0.81, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.54 to 1.21; participants = 1804; studies = 6; I2 = 47%; very low‐quality evidence). We performed a subgroup analysis for ASV therapy or CPAP therapy, which showed no evidence of a difference between the groups (test for subgroup differences: P = 0.79). We did not perform the other subgroup analyses because an I2 > 50% was not obtained. We performed the following sensitivity analyses: exclusion of studies at high risk of bias (missing data > 20%), exclusion of trials with 10 or fewer events, and comparing fixed‐effect versus random‐effects models; the results were not changed after sensitivity analyses (Table 3).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PAP therapy versus usual care, Outcome 1 All‐cause mortality.

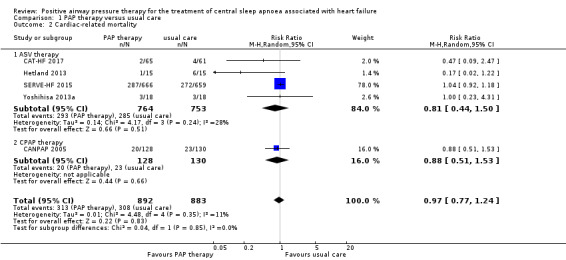

Cardiac‐related mortality

Five trials involving 1775 participants reported cardiac‐related mortality (Analysis 1.2). There was no difference between groups when comparing PAP therapy with usual care (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.24; participants = 1775; studies = 5; I2 = 11%; moderate‐quality evidence). We performed a subgroup analysis for ASV therapy or CPAP therapy, which showed no difference between the groups (test for subgroup differences: P = 0.85). We did not perform the other subgroup analyses because an I2 > 50% was not obtained. We performed the following sensitivity analyses: exclusion of studies at high risk of bias (missing data > 20%), exclusion of trials with 10 or fewer events, and comparing fixed‐effect versus random‐effects models; the results were not changed after sensitivity analyses (Table 3).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PAP therapy versus usual care, Outcome 2 Cardiac‐related mortality.

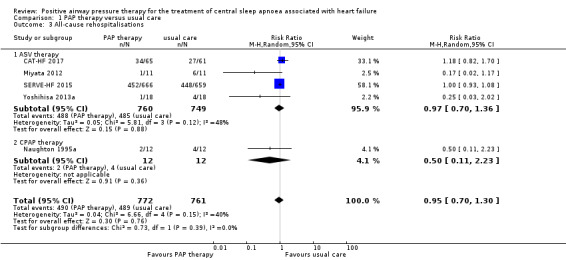

All‐cause rehospitalisations

Five trials involving 1533 participants reported all‐cause rehospitalisations (Analysis 1.3). There was no evidence of a difference between groups when comparing PAP therapy with usual care (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.30; participants = 1533; studies = 5; I2 = 40%; low‐quality evidence). We performed a subgroup analysis for ASV therapy or CPAP therapy, which showed no evidence of a difference between the groups (test for subgroup differences: P = 0.39). We did not perform the other subgroup analyses because an I2 > 50% was not obtained. We performed the following sensitivity analyses: exclusion of studies at high risk of bias (missing data > 20%), exclusion of trials with 10 or fewer events, and comparing fixed‐effect versus random‐effects models; the results were not changed after sensitivity analyses (Table 3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PAP therapy versus usual care, Outcome 3 All‐cause rehospitalisations.

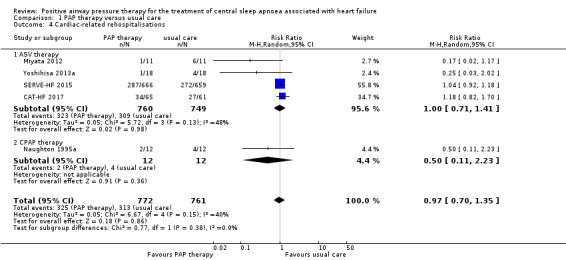

Cardiac‐related rehospitalisations: defined as total number of rehospitalisations

Five trials involving 1533 participants reported cardiac‐related rehospitalisations (Analysis 1.4). There was no evidence of a difference between groups when comparing PAP therapy with usual care (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.35; participants = 1533; studies = 5; I2 = 40%; low‐quality evidence). We performed a subgroup analysis for ASV therapy or CPAP therapy, which showed no evidence of a difference between the groups (test for subgroup differences: P = 0.38). We did not perform the other subgroup analyses because an I2 > 50% was not obtained. We performed the following sensitivity analyses: exclusion of studies at high risk of bias (missing data > 20%), exclusion of trials with 10 or fewer events, and comparing fixed‐effect versus random‐effects models; the results were not changed after sensitivity analyses (Table 3).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PAP therapy versus usual care, Outcome 4 Cardiac‐related rehospitalisations.

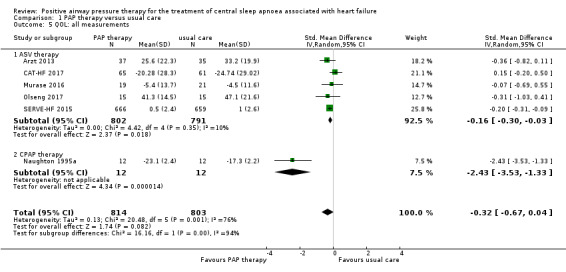

Health‐related QOL as assessed by validated questionnaires

Quality of life was assessed using the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ), the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ), the Chronic Heart Failure Questionnaire (CHFQ), or the 36‐item Short Form Health Survey (SF‐36). Four trials assessed QOL with the MLHFQ (Arzt 2013; Murase 2016; Olseng 2017; SERVE‐HF 2015), whilst two trials used the other questionnaires (CAT‐HF 2017; Naughton 1995a). When pooling 6 trials involving 1617 participants that reported QOL scores using all measurements, there might be some improvement benefit for PAP therapy (standardised mean difference (SMD) −0.32, 95% CI −0.67 to 0.04; participants = 1617; studies = 6; I2 = 76%; low‐quality evidence) compared with usual care (Analysis 1.5). This SMD size is considered to be a small effect according to the Cohen paper (Cohen 1988), as cited in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PAP therapy versus usual care, Outcome 5 QOL: all measurements.

The substantial heterogeneity was explained by subgroup analysis, with P < 0.001 from the test for subgroup differences. Studies of CPAP therapy (SMD −2.43, 95% CI −3.53 to −1.33; participants = 24; studies = 1) showed a larger treatment effect than studies of ASV therapy (SMD −0.16, 95% CI −0.30 to −0.03; participants = 1593; studies = 5). Heterogeneity was lower after subgroup analysis compared with pre‐subgroup analysis. We also performed subgroup analyses for age (≤ 65 years or > 65 years) and follow‐up (≤ 1 year or > 1 year); the heterogeneity remained, with no difference between subgroups (P = 0.50 for the subgroup analysis by age, and P = 0.41 for the subgroup analysis by length of follow‐up) (Table 2). We were unable to perform the remaining planned subgroup analyses because most of recruited participants were men, AHI > 15/h, HFrEF and Cheyne‐Stokes breathing. We performed the following sensitivity analyses: exclusion of studies at high risk of bias (missing data > 20%) (Murase 2016; Olseng 2017); and comparing fixed‐effect versus random‐effects models. After sensitivity analysis excluding studies at high risk of bias, there was no difference between the groups. However, there might be some improvement benefit for PAP therapy (SMD −0.20, 95% CI −0.29 to −0.10) compared with usual care after sensitivity analysis using the fixed‐effect model (Table 3).

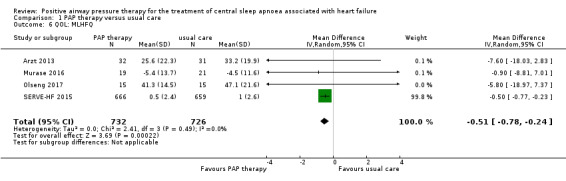

When pooling 4 trials involving 1458 participants that reported MLHFQ scores, only ASV therapy was used. There was some indication of an improvement with ASV therapy (mean difference (MD) −0.51, 95% CI −0.78 to −0.24; participants = 1458; studies = 4; I2 = 0%; low‐quality evidence) compared with usual care (Analysis 1.6). We performed the following sensitivity analyses: exclusion of studies at high risk of bias (missing data > 20%) and comparing fixed‐effect versus random‐effects models; the results were not changed after sensitivity analyses (Table 3).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PAP therapy versus usual care, Outcome 6 QOL: MLHFQ.

Adverse events

As there were only three trials with adverse events, we reported these results narratively. One trial involving 63 participants reported death due to pneumonia (N = 1, 3%), cardiac worsening (N = 3, 9%), deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism (N = 1, 3%), and foot ulcer (N = 1, 3%) in the PAP therapy group, whereas cardiac worsening (N = 5, 14%) and duodenal ulcer (N = 1, 3%) were reported in the usual care group (Arzt 2013). Another trial involving 24 participants reported no adverse events in the PAP therapy group, and cardiac arrest (N = 1, 8%) and heart transplantation (N = 1, 8%) in the usual care group (Naughton 1995a). The third trial involving 1349 participants reported cardiac arrest (N = 18, 3%) and heart transplantation (N = 8, 1%) in the PAP therapy group, and cardiac arrest (N = 16, 2%) and heart transplantation (N = 12, 2%) in the usual care group (SERVE‐HF 2015). Due to the low numbers of events, there was insufficient evidence to assess whether adverse events were more common with PAP therapy than with usual care.

Secondary outcomes

SDB markers

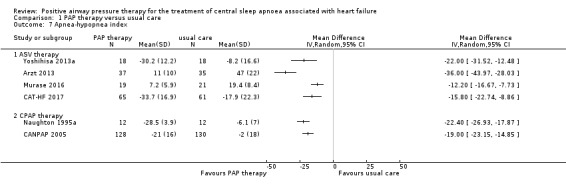

AHI was measured to assess SDB markers using polygraphy or polysomnography. Seven trials involving 580 participants reported AHI at the baseline and endpoint. We found substantial heterogeneity that was not explained by the following subgroup analyses; age (≤ 65 years or > 65 years), device (CPAP or ASV), and follow‐up (≤ 1 year or > 1 year). We were unable to perform the subgroup analyses because most of recruited participants were men, AHI > 15/h, HFrEF and Cheyne‐Stokes breathing. We therefore reported AHI narratively. The intervention was ASV therapy in four trials, Arzt 2013; CAT‐HF 2017; Murase 2016; Yoshihisa 2013a, and CPAP therapy in two trials (CANPAP 2005; Naughton 1995a). There was an improvement in PAP therapy compared with usual care in all seven trials (Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PAP therapy versus usual care, Outcome 7 Apnea‐hypopnea index.

Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular function markers: left ventricular ejection fraction and BNP

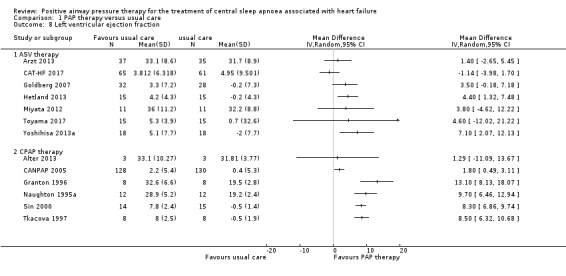

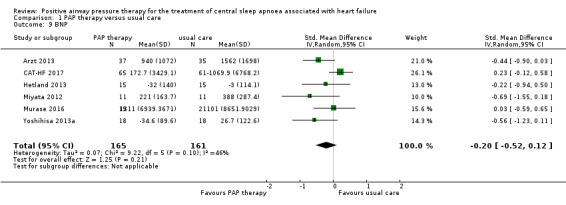

LVEF and BNP were measured to assess cardiovascular function markers. LVEF was measured using echocardiography. Thirteen trials involving 725 participants reported LVEF at the baseline and endpoint. We found substantial heterogeneity that was not explained by the following subgroup analyses: age (≤ 65 years or > 65 years), device (CPAP or ASV), and follow‐up (≤ 1 year or > 1 year). We were unable to perform the subgroup analyses because most of recruited participants were men, AHI > 15/h, HFrEF and Cheyne‐Stokes breathing. We therefore reported LVEF narratively. The intervention was ASV therapy in seven trials, Arzt 2013; CAT‐HF 2017; Goldberg 2007; Hetland 2013; Miyata 2012; Toyama 2017; Yoshihisa 2013a, and CPAP therapy in six trials (Analysis 1.8) (Alter 2013; CANPAP 2005; Granton 1996; Naughton 1995a; Sin 2000; Tkacova 1997). There was an improvement of 1.29% to 13.1% in PAP therapy compared with usual care in 12 trials. The remaining trial, CAT‐HF 2017, reported that the change of LVEF from baseline to endpoint in the usual care group was a little higher than that in the PAP therapy group (3.8% in PAP therapy versus 4.9% in usual care); however, this approximate 1% difference was not significant. In contrast, six trials involving 326 participants reported BNP or N‐terminal pro b‐type natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP) at the baseline and endpoint. The intervention was ASV therapy in all six trials (Analysis 1.9) (Arzt 2013; CAT‐HF 2017; Hetland 2013; Miyata 2012; Murase 2016; Yoshihisa 2013a). There was no evidence of a difference between the groups when comparing PAP therapy with usual care (SMD −0.20, 95% CI −0.52 to 0.12; I2 = 46%).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PAP therapy versus usual care, Outcome 8 Left ventricular ejection fraction.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PAP therapy versus usual care, Outcome 9 BNP.

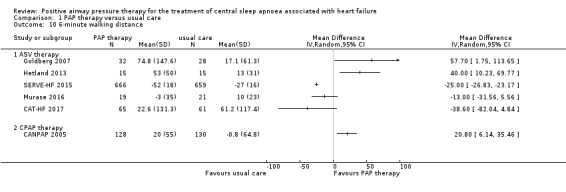

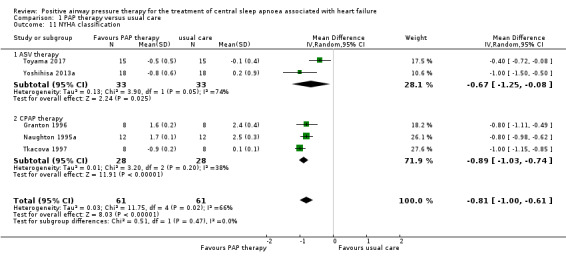

Physical function markers: 6‐minute walking distance and NYHA classification

Six‐minute walking distance and NYHA classification were measured to assess physical function markers. Six‐minute walking distance was assessed in six trials involving 1839 participants, whilst NYHA was assessed in five trials involving 136 participants at the baseline and endpoint. We found substantial heterogeneity that was not explained by the following subgroup analyses: age (≤ 65 years or > 65 years), device (CPAP or ASV), and follow‐up (≤ 1 year or > 1 year). We were unable to perform the subgroup analyses because most of recruited participants were men, AHI > 15/h, HFrEF and Cheyne‐Stokes breathing. We therefore reported 6‐minute walking distance narratively. The intervention was ASV therapy in five trials, CAT‐HF 2017; Goldberg 2007; Hetland 2013; Murase 2016; SERVE‐HF 2015, and CPAP therapy in one trial (Analysis 1.10) (CANPAP 2005). There was improvement in the PAP therapy group compared with the usual care group in three trials that were conducted before the year 2013 (CANPAP 2005; Goldberg 2007; Hetland 2013). In contrast, there was no improvement in the PAP therapy group compared with the usual care group in three recent three trials conducted since 2015 (CAT‐HF 2017; Murase 2016; SERVE‐HF 2015). When pooling four trials that reported NYHA classification, there was a significant improvement in all participants with PAP therapy (MD −0.81, 95% CI −1.00 to −0.61; I2 = 66%) compared with usual care (Analysis 1.11). We performed a subgroup analysis for ASV therapy or CPAP therapy, which showed evidence of difference between the groups in ASV therapy (MD −0.67, 95% CI −1.25 to −0.08) and CPAP therapy (MD −0.89, 95% CI −1.03 to −0.74). Although an RCT, one trial was removed from the analysis because the SD was zero. The median of differences between baseline and endpoint were −1.0 class (interquartile range (IQR): −1.0 to 0.0) in ASV therapy and 0.0 class (IQR: 0.0 to 0.0) in usual care (Hetland 2013).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PAP therapy versus usual care, Outcome 10 6‐minute walking distance.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 PAP therapy versus usual care, Outcome 11 NYHA classification.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We included 16 RCTs (44 references) involving a total of 2125 participants in this review. The studies evaluated PAP therapy consisting of ASV or CPAP therapy for 1 to 31 months in Europe, the United States, Canada, and Japan. Although our meta‐analysis included participants with HFrEF and HFpEF, 98% of participants had HFrEF. Many trials included mostly male participants or only males.

The main findings of the review are that the effects of PAP therapy on all‐cause mortality and 6‐minute walking distance were uncertain, and it did not reduce the risk of cardiac‐related mortality and rehospitalisation or BNP; however, PAP therapy showed some indication of an improvement in QOL, NYHA classification, AHI, and LVEF. Furthermore, pneumonia, cardiac arrest, heart transplantation, cardiac worsening, deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism, foot ulcer, and duodenal ulcer were reported in the included studies. The incidence rates of adverse events were less than 10% in both groups, excluding cardiac worsening (14%) in usual care. Due to the low numbers of events, there was insufficient evidence to assess whether adverse events were more common with PAP than with usual care. However, this finding was limited due to low‐quality evidence. Furthermore, we identified three problems with the included trials. First, the period of most PAP therapy was rather short (median 3 months). Although the duration of PAP therapy was more than one year in three trials (CANPAP 2005; SERVE‐HF 2015; Yoshihisa 2013a), it was less than six months in the remaining trials. Second, only three trials reported adverse events (Arzt 2013; Naughton 1995a; SERVE‐HF 2015). Although PAP therapy did not increase adverse events compared with usual care, we were unable to determine whether the reported adverse events were related to PAP therapy because we could not perform a meta‐analysis. Third, many participants had HFrEF, excluding one trial (Yoshihisa 2013a), whilst in the real world the percentage of heart failure patients with HFrEF or HFpEF is equal (Okura 2008). We need therefore to assess the effectiveness of PAP therapy for people with HFpEF.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The generalisability of this review is limited by the average age, sex, and percentage of HFrEF. The previous large cohort studies reported a mean age of patients with heart failure of more than 70 years, and half of the patients were men and had HFrEF (Adams 2005; Lee 2014; Nieminen 2006; Sato 2013). However, the mean age of participants in most studies ranged from 60 to 70 years. Furthermore, 92% of recruited participants were men. In addition, all trials except for Yoshihisa 2013a included participants with HFrEF only. However, as HFrEF is the most common cause of CSA in men and the elderly (Sin 1999), it is possible that the effect of the intervention is sufficiently shown in this meta‐analysis. Another concern is that the largest trial, SERVE‐HF 2015, weighed more than 50% in some primary outcomes; it is therefore possible that these outcomes were heavily influenced by this one trial (SERVE‐HF 2015). However, SERVE‐HF 2015 has a large sample size and is a high‐quality, multicentre RCT, and may therefore accurately represent the necessity of PAP therapy. Finally, although we analysed the combined effects of PAP therapy including both ASV and CPAP, these two therapies are different modes of applying positive airway pressure. The setting and mode of PAP therapy in clinical practice must be understood before PAP therapy is used.

Quality of the evidence

More than 25% of the included trials were assessed as low risk of bias for allocation concealment, selective outcome reporting, and blinding of outcome assessment. However, as random sequence generation and blinding of participants and personnel were poorly described, we downgraded the quality of evidence by one level due to study limitations for all outcomes. We downgraded the quality of evidence by one level for all‐cause mortality and QOL due to inconsistency because heterogeneity was more than 40%. In addition, we downgraded the quality of evidence by one level for all‐cause mortality, all‐cause rehospitalisation, and cardiac‐related rehospitalisation due to imprecision because the 95% CIs were very wide. For these reasons, we judged the quality of the evidence to be low or very low.

Potential biases in the review process

We conducted this review according to the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Furthermore, we undertook a comprehensive electronic search to identify published and unpublished studies, and synthesised and analysed data according to our review protocol (Yamamoto 2017). We also searched conference abstracts. However, most abstracts focused on the same trials, or lacked sufficient data including authors’ contact information. It is therefore possible that we did not obtain all relevant data. Furthermore, due to the nature of the PAP therapy, blinding was not possible. An information bias is therefore possible.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Our findings demonstrated that the effectiveness of PAP therapy was uncertain because the evidence for most primary outcomes was of low or very low quality, excluding one outcome that reported evidence of moderate quality, although there was some indication of an improvement in QOL score, NYHA classification, AHI, and LVEF. A previous systematic review and meta‐analysis showed that PAP therapy significantly reduced mortality compared with the control for heart failure patients with CSA (RR 0.13, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.95) (Nakamura 2015). However, the search conducted in that systematic review was limited to only English language articles identified through three electronic search engines, that is CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and Embase, on March 2014. Consequently, that systematic review did not include large trials, that is SERVE‐HF 2015 and CAT‐HF 2017. Whilst our review included 16 trials (44 references) involving a total of 2125 heart failure patients with only CSA, Nakamura's review included 11 trials with a total of 1944 heart failure patients with both CSA and OSA. Median follow‐up duration was longer in our review than in Nakamura's review because we included SERVE‐HF 2015, which had the longest follow‐up duration of the included studies. In addition, Nakamura 2015 did not report the effectiveness of PAP therapy on adverse events, rehospitalisation, QOL, NYHA classification, AHI, or LVEF, or information related to risk of bias. Our findings therefore provide more up‐to‐date results on a wider range of trials and outcomes compared with the previous review (Nakamura 2015).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

We found evidence that the effects of positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy on all‐cause mortality and 6‐minute walking distance were uncertain, and it did not reduce the risk of cardiac‐related mortality, rehospitalisation, and brain natriuretic peptide; however, PAP therapy showed some indication of an improvement in quality of life, New York Heart Association classification, apnea–hypopnea index, and left ventricular ejection fraction for heart failure patients with central sleep apnoea. These findings were limited by low‐ or very low‐quality evidence. The current European Society of Cardiology guideline does not recommend adaptive servo‐ventilation (ASV) therapy for patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) (Ponikowski 2016), as the SERVE‐HF trials reported on the limited effectiveness of ASV therapy. However, our findings did not show any increase in adverse events with PAP therapy, that is ASV or continuous PAP therapy, for participants with heart failure. PAP therapy may be beneficial for individuals with heart failure, as it may improve sleep quality, subjective symptoms, and quality of life.

Implications for research.

Most participants in the trials included in this review had HFrEF, although this review included participants with HFrEF or heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). The number of people with HFrEF or HFpEF is estimated to continue increasing until 2035 (Mozaffarian 2015; Okura 2008). Furthermore, the number of elderly heart failure patients may also increase in the future. We therefore need to assess patients with HFpEF and elderly patients in future studies. In addition, the evidence reported in this review was limited by being of low or very low quality. More high‐quality randomised controlled trials are needed to further clarify the effectiveness of PAP, or the difference between ASV and CPAP for heart failure patients with central sleep apnoea.

Acknowledgements

The review authors thank Ms Emma Barber for providing editorial support. We also thank the Information Specialist of the Cochrane Heart Group for supporting our search efforts. The Methods section of this review is based on a standard template used by the Cochrane Heart Group. We also thank Dr Anders Holt, Department of Cardiovascular, Herlev and Gentofte Hospital, Denmark, and Brian Duncan for peer review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

CENTRAL

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Continuous Positive Airway Pressure] this term only

#2 MeSH descriptor: [Intermittent Positive‐Pressure Ventilation] this term only

#3 positiv* airway* pressur*

#4 airway pressure release ventilation

#5 (PAP or CPAP or BiPAP or ASV or aprv)

#6 #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5

#7 MeSH descriptor: [Heart Failure] explode all trees

#8 ((cardi* or heart* or myocard*) near/2 (fail* or incompet* or insufficien* or decomp*))

#9 #7 or #8

#10 #6 and #9

MEDLINE Ovid

1. continuous positive airway pressure/ or intermittent positive‐pressure ventilation/

2. positiv* airway* pressur*.tw.

3. airway pressure release ventilation.tw.

4. (PAP or CPAP or BiPAP or ASV or aprv).tw.

5. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4

6. exp Heart Failure/

7. ((cardi* or heart* or myocard*) adj2 (fail* or incompet* or insufficien* or decomp*)).tw.

8. 6 or 7

9. 5 and 8

10. randomized controlled trial.pt.

11. controlled clinical trial.pt.

12. randomized.ab.

13. placebo.ab.

14. drug therapy.fs.

15. randomly.ab.

16. trial.ab.

17. groups.ab.

18. 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17

19. exp animals/ not humans.sh.

20. 18 not 19

21. 9 and 20

Embase Ovid

1. positive end expiratory pressure/ or intermittent positive pressure ventilation/

2. positiv* airway* pressur*.tw.

3. airway pressure release ventilation.tw.

4. (PAP or CPAP or BiPAP or ASV or aprv).tw.

5. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4

6. exp heart failure/

7. ((cardi* or heart* or myocard*) adj2 (fail* or incompet* or insufficien* or decomp*)).tw.

8. 6 or 7

9. 5 and 8

10. random$.tw.

11. factorial$.tw.

12. crossover$.tw.

13. cross over$.tw.

14. cross‐over$.tw.

15. placebo$.tw.

16. (doubl$ adj blind$).tw.

17. (singl$ adj blind$).tw.

18. assign$.tw.

19. allocat$.tw.

20. volunteer$.tw.

21. crossover procedure/

22. double blind procedure/

23. randomized controlled trial/

24. single blind procedure/

25. 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24

26. (animal/ or nonhuman/) not human/

27. 25 not 26

28. 9 and 27

Web of Science

#8 #7 AND #6

#7 TS=(random* or blind* or allocat* or assign* or trial* or placebo* or crossover* or cross‐over*)

#6 #5 AND #4

#5 TS=((cardi* or heart* or myocard*) near/2 (fail* or incompet* or insufficien* or decomp*))

#4 #3 OR #2 OR #1

#3 TS=(PAP or CPAP or BiPAP or ASV or aprv)

#2 TS=airway pressure release ventilation

#1 TS=positiv* airway* pressur*

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) Search Portal

"heart failure" AND "central sleep apnea" AND "positive airway pressure"

ClinicalTrials.gov

"heart failure" AND "central sleep apnea" AND "positive airway pressure"

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. PAP therapy versus usual care.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 All‐cause mortality | 6 | 1804 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.54, 1.21] |

| 1.1 ASV therapy | 4 | 1517 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.62 [0.26, 1.50] |

| 1.2 CPAP therapy | 2 | 287 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.31, 1.74] |

| 2 Cardiac‐related mortality | 5 | 1775 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.77, 1.24] |

| 2.1 ASV therapy | 4 | 1517 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.44, 1.50] |

| 2.2 CPAP therapy | 1 | 258 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.51, 1.53] |

| 3 All‐cause rehospitalisations | 5 | 1533 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.70, 1.30] |

| 3.1 ASV therapy | 4 | 1509 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.70, 1.36] |

| 3.2 CPAP therapy | 1 | 24 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.5 [0.11, 2.23] |

| 4 Cardiac‐related rehospitalisations | 5 | 1533 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.70, 1.35] |

| 4.1 ASV therapy | 4 | 1509 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.00 [0.71, 1.41] |

| 4.2 CPAP therapy | 1 | 24 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.5 [0.11, 2.23] |

| 5 QOL: all measurements | 6 | 1617 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.32 [‐0.67, 0.04] |

| 5.1 ASV therapy | 5 | 1593 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.16 [‐0.30, ‐0.03] |

| 5.2 CPAP therapy | 1 | 24 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.43 [‐3.53, ‐1.33] |

| 6 QOL: MLHFQ | 4 | 1458 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.51 [‐0.78, ‐0.24] |

| 7 Apnea‐hypopnea index | 6 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 7.1 ASV therapy | 4 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 7.2 CPAP therapy | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 8 Left ventricular ejection fraction | 13 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 8.1 ASV therapy | 7 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 8.2 CPAP therapy | 6 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 9 BNP | 6 | 326 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.20 [‐0.52, 0.12] |

| 10 6‐minute walking distance | 6 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 10.1 ASV therapy | 5 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 10.2 CPAP therapy | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 11 NYHA classification | 5 | 122 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.81 [‐1.00, ‐0.61] |

| 11.1 ASV therapy | 2 | 66 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.67 [‐1.25, ‐0.08] |

| 11.2 CPAP therapy | 3 | 56 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.89 [‐1.03, ‐0.74] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Alter 2013.

| Methods |

Study design: single‐centre RCT Country and setting: Germany Date of study: unclear |

|

| Participants | Chronic heart failure patients with SDB (CSA ≥ 50%) Inclusion criteria: unclear Exclusion criteria: unclear Number randomised: N total = 6 (PAP 3, usual care 3) Mean age (years, mean ± SD): unclear Sex: unclear LVEF (%): PAP 19.9 ± 11.2, usual care 29.8 ± 3.31 AHI (number/hour): total 27 ± 14 Numbers lost to follow‐up: 3 (PAP 2, usual care 1) |

|

| Interventions |

Device: CPAP therapy Airway pressure: not described Follow‐up duration: 3 months |

|

| Outcomes | LVEF, end‐systolic wall stress and end‐systolic wall | |

| Notes | Industry sponsors were not described in this study. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Participants were allocated at 1:1 randomisation to PAP therapy or usual care, however details about allocation sequence generation are not provided. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Details about concealment of allocation were not provided. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Due to the nature of PAP therapy, blinding was not possible. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias): Subjective or patient‐reported outcomes | Unclear risk | Details about blinding of the outcome assessment were not provided. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias): All other outcomes | Low risk | The evaluation of cardiovascular function markers was not affected by outcome assessors. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | The number of participants who dropped out or withdrew from the study was not provided. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | A protocol was not published, therefore unclear risk of bias. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | It was unclear whether there were differences between groups at baseline. |

Arzt 2013.

| Methods |

Study design: single‐centre RCT Country and setting: Germany Date of study: March 2007 to September 2009 |

|

| Participants | Chronic heart failure patients with SDB (CSA 47%) Inclusion criteria: patients aged 18 to 80 years, with CHF (NYHA II–III) due to ischaemic, non‐ischaemic, or hypertensive cardiomyopathy, an LVEF< 40%, AHI > 20 events/h, stable clinical status, and stable optimal medical therapy Exclusion criteria: unstable angina, myocardial infarction, cardiac surgery, hospital admissions within the previous 3 months, contraindications for positive airway pressure therapy, using oxygen therapy, or had severe pulmonary disease or symptoms of SDB Number randomised: N total = 72 (PAP 37, usual care 35) Mean age (years, mean ± SD): PAP 64 ± 10, usual care 65 ± 9 Sex: unclear LVEF (%): PAP 29.9 ± 7.2, usual care 29.4 ± 6.9 AHI (number/hour): PAP 48 ± 18, usual care 47 ± 19 Numbers lost to follow‐up: 3 (PAP 2, usual care 1) |

|

| Interventions |

Device: ASV therapy Airway pressure: 10 cmH2O Follow‐up duration: 3 months |

|

| Outcomes | Adverse events, LVEF, AHI, NT‐proBNP, SF‐36, and MLHFQ | |

| Notes | This study received external funds from an industry sponsor. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation was performed using a computer‐generated schedule. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation codes were made available by fax back‐request after testing for eligibility for the study. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Due to the nature of PAP therapy, blinding was not possible. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias): Subjective or patient‐reported outcomes | Low risk | Outcome assessors were blinded. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias): All other outcomes | Low risk | Outcome assessors were blinded. The incidence of adverse events was not affected by outcome assessors. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | 5 participants in the PAP therapy group did not complete the study: 4 withdrew and 1 died (dropout rate 14%). 4 participants in the usual care group withdrew from the study (dropout rate 11%). |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes were reported according to a registered protocol (ISRCTN04353156). |

| Other bias | High risk | There were significant differences in body mass index between groups at baseline (28.9 ± 4.3 kg/m2 vs 31.6 ± 4.9 kg/m2). |

CANPAP 2005.

| Methods |

Study design: multicentre RCT (11 centres in Canada) Country and setting: Canada Date of study: December 1998 to May 2004 |

|

| Participants | Chronic heart failure patients with CSA Inclusion criteria: patients aged 18 to 79 years, NYHA II–III heart failure due to ischaemic, hypertensive, or idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy and whose condition had been stabilised by means of optimal medical therapy for at least 1 month, LVEF < 40%, AHI > 15 events/h Exclusion criteria: pregnancy, myocardial infarction, unstable angina or cardiac surgery within the previous 3 months, and obstructive sleep apnoea Number randomised: N total = 258 (PAP 128, usual care 130) Mean age (years, mean ± SD): PAP 63.5 ± 9.8, usual care 63.2 ± 9.1 Sex: Total: men 248, women 10 PAP: men 123, women 7 Usual care: men 125, women 3 AHI (number/hour): PAP 40 ± 17, usual care 40 ± 15 LVEF (%): PAP 24.2 ± 7.6, usual care 24.8 ± 7.9 Numbers lost to follow‐up: 40 (PAP 20, usual care 20) |

|

| Interventions |

Device: CPAP therapy. Participants assigned to CPAP underwent further randomisation in a 2:1:1 ratio to the devices (Respironics Remstar Pro, ResMed Sullivan VII, or Tyco Healthcare GoodKnight 420S, respectively). Airway pressure: initially started at a pressure of 5 cmH2O, then increased by 2 to 3 cmH2O until reaching a pressure of 10 cmH2O. Follow‐up duration: 24 months |

|

| Outcomes | All‐cause or cardiovascular mortality, AHI, LVEF, and 6‐minute walking distance | |

| Notes | This study received external funds from an industry sponsor. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomisation was performed using a computerised method. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Treatment assignment was communicated to the study centres by the data management centre. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Due to the nature of PAP therapy, blinding was not possible. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias): Subjective or patient‐reported outcomes | Unclear risk | Details about blinding of the outcome assessment were not reported. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias): All other outcomes | Low risk | The incidence of mortality and rehospitalisations and the evaluation of cardiovascular function markers were not affected by outcome assessors. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | 20 participants in each group (15.5%) dropped out. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes were reported according to a registered protocol (NCT00811668). |

| Other bias | Low risk | There were no significant differences between groups at baseline. Furthermore, this study performed an intention‐to‐treat analysis. |

CAT‐HF 2017.

| Methods |