Abstract

Small terrestrial mammals could be used as accumulative biomonitors of different environmental contaminants, but the knowledge of the level of Hg in their bodies is scant. The aim of our research was to verify the factors influencing Hg bioaccumulation and to analyze the concentration of total mercury (Hg) in the livers of four species of wild terrestrial rodents from different rural areas of Poland: the yellow-necked mouse (Apodemus flavicollis), striped field mouse (Apodemus agrarius), common vole (Microtus arvalis), and bank vole (Myodes glareolus). The concentration of total Hg was analyzed in liver tissue by atomic absorption spectrometry using a direct mercury analyzer. The concentration of Hg found in the livers of rodents ranged from <1 to 36.4 µg/kg of wet weight, differed between study sites, species, and sexes, and was related to body weight. We addressed feeding habits as potential causes of differences in liver Hg concentration among species.

Keywords: total mercury, liver, wild rodents, bank vole, common vole, yellow-necked mouse, striped field mouse

1. Introduction

Mercury (Hg) is considered one of the most hazardous non-essential trace elements, and its fate in the environment, where it is ubiquitous, is a matter of concern worldwide [1]. The mechanisms of Hg toxicity are well known and depend on its chemical form [2,3]. Mercury can be emitted both from natural sources, such as volcanic eruptions and forest fires, and from anthropogenic sources, including coal combustion, notoriously used in the non-ferrous metals industry, cement production, and artisanal gold mining. Global anthropogenic Hg emissions were estimated at 2220 Mg in 2015 [4]. In Poland, anthropogenic emissions in 2016 were 10.3 Mg and were mainly caused by coal combustion for the production of electricity and heat, in industrial processing of non-ferrous metals, and in small household boilers [5,6]. The deposition of Hg may lead to contamination of both aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems [1], and inorganic Hg may be converted by microbial communities into more toxic methylmercury [7], which can be accumulated in the trophic chain [8]. Different organisms have been used as bioindicators of Hg pollution in terrestrial ecosystems, including invertebrates [9,10,11,12], birds [13,14,15], bats [16], shrews [17,18,19], moles [19], foxes [20], and mustelids [21,22]. Rodents are also considered good bioindicators of environmental pollution due to their widespread occurrence, high reproductive rate and abundance, short lifespan, and good availability [23,24]. However, differences in biotope preferences, feeding habits, and behavior may result in differential bioaccumulation of contaminants between particular species.

The bank vole (Myodes glareolus, Schreber 1780, formerly Clethrionomys glareolus) and the common vole (Microtus arvalis, Pallas 1778) belong to the Arvicolinae subfamily. The bank vole inhabits different types of woodlands [25]. Its diet is based mainly on aerial vegetative parts of plants and fruits but also includes invertebrates and fungi [26]. The common vole has a larger body weight than M. glareolus has (27.5 versus 17–20 g) [27,28], prefers open habitats, including meadows, pastures, and farming areas [29], and feeds mainly on herbaceous plants and grasses—invertebrates are very rarely present in its diet [26].

The striped field mouse (Apodemus agrarius, Pallas 1771) and yellow-necked mouse (Apodemus flavicollis, Melchior 1834) are two species that belong to the Muridae family and are also widely distributed in Eurasia, including Poland. The striped field mouse inhabits fields, meadows, gardens, the edges of forests, and roadside scrub parks [30] and is well adapted to urban habitats [31]. Its diet consists mainly of seeds, fruits, and invertebrates [26]. The yellow-necked mouse is considered a typical forest species and rarely occurs in urban areas [31]. The diet of A. flavicollis is more diverse compared to that of A. agrarius. Additionally to seeds, fruits, and invertebrates, A. flavicollis eats aboveground parts of plants, flowers, and fungi [26].

The objectives of our work were to analyze the concentration of total Hg in the livers of these four species of rodents and to verify the influence of study site, age, sex, and body weight (b.w.) on Hg bioaccumulation.

2. Results

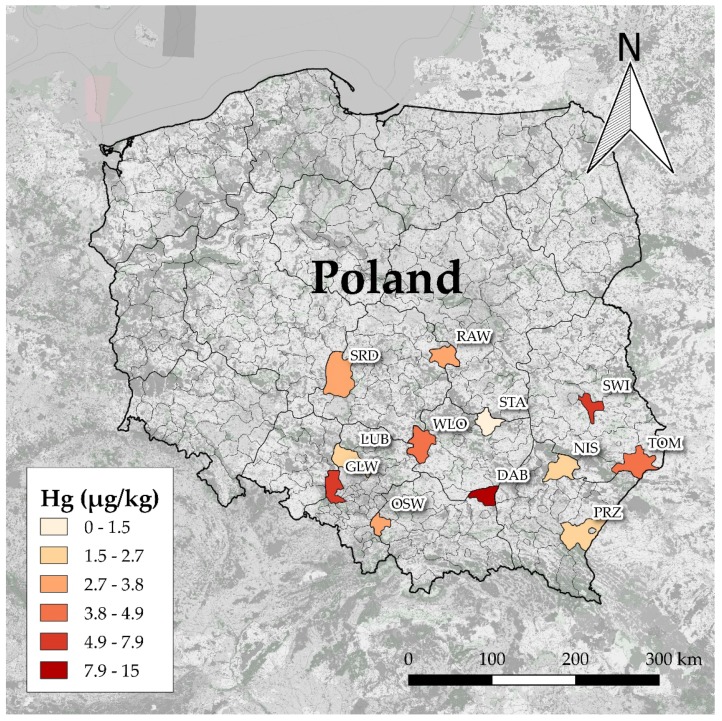

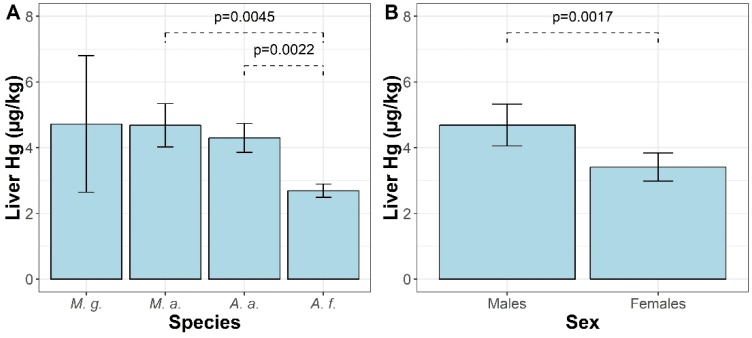

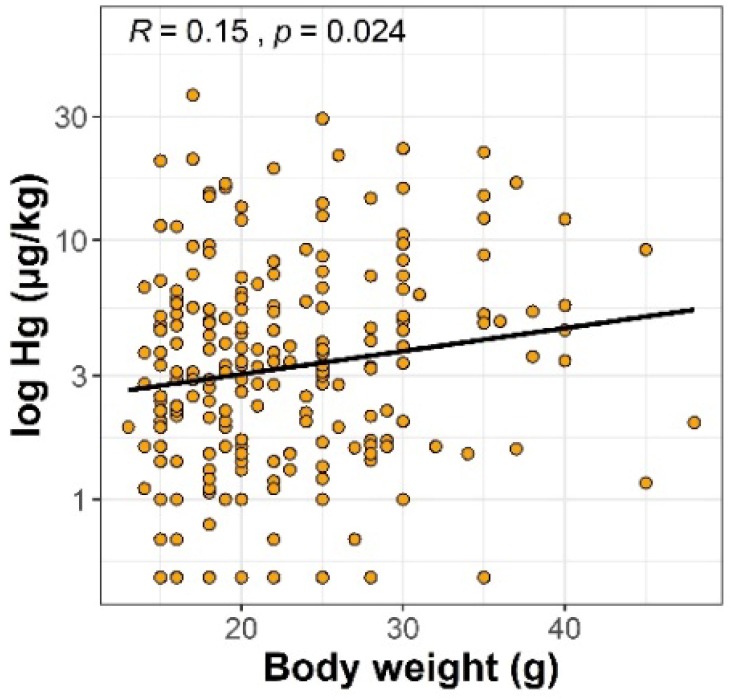

The concentration of Hg found in the livers of rodents ranged from <1 to 36.4 µg/kg wet weight. The descriptive statistics of Hg concentrations in the livers of rodents according to their species, sex, and sampling site are summarized in Supplementary Table S3. Generalized linear model (GLM) analysis showed that liver Hg concentrations were influenced by study site (F = 10.1, p = 2 × 10−16), sex (F = 9.9, p = 1.9 × 10−3), species (F = 6.1, p = 5.6 × 10−4), and body weight (F = 7.7, p = 5.9 × 10−3). Site-specific differences in liver Hg concentrations are shown in Figure 1. The highest estimated mean level of Hg in the livers of all species of rodents was at the DAB site (15 ± 4 μg/kg) and was higher than that found in other study sites (p < 0.05), with the exception of GLW and SWI. The second area with high liver Hg concentration was GLW (7.9 ± 2 μg/kg), located in Upper Silesia, and animals from STA had the lowest marginal mean Hg content in the liver (1.5 μg/kg). Differences between estimated marginal mean concentrations of Hg among study sites are presented in Supplementary Table S4 for clarification. Some differences between species were also salient. The levels of Hg in the livers of A. flavicollis were about half those of A. agrarius and M. arvalis (Figure 2A). The estimated mean Hg level in the livers of M. glareolus was 4.7 ± 2 μg/kg, which was almost twice that of A. flavicollis, but the difference was not confirmed statistically. Comparing the differences between sexes, it was found that males tended to accumulate about 38% more Hg in their livers than females (Figure 2B). Rodent body weight and Hg concentration in the liver were positively correlated, as shown by the Spearman rank correlation test (Figure 3), which confirmed the GLM findings.

Figure 1.

Concentrations of Hg in the livers of rodents from 12 study sites. The color scale represents estimated marginal means (in µg/kg of wet weight.). Results were averaged by species and sex.

Figure 2.

(A) Differences in Hg concentrations in the liver between species (M. g—Myodes glareolus; M. a.—Microtus arvalis; A. a.—Apodemus agrarius; A. f.—Apodemus flavicollis). Results (in µg/kg of wet weight) were averaged by study site and sex. (B) Differences in Hg concentrations in the liver between males and females (in µg/kg of wet weight). Results were averaged by study site and species. Both bar and whisker plots show estimated marginal means and standard errors that were back-transformed from the log scale. Differences between marginal means were verified on the log scale.

Figure 3.

Spearman rank correlation coefficients between body weight of rodents and concentrations of Hg in their livers.

3. Discussion

We found the highest levels of Hg in rodents from the DAB and GLW areas. The DAB area is located in the northeastern part of the Małopolskie voivodeship. According to national monitoring data, the median background Hg level in topsoil collected at the DAB site was 0.090 mg/kg (Supplementary Table S1). Surprisingly, there were no known major emitters close to the area, such as power plants, smelters, or other heavy industrial facilities, that may have been a source of Hg to the surrounding environment. We assume that local emissions caused by the combustion of coal in household boilers could also contribute to Hg bioaccumulation in biota [32]. The second region to the DAB site in terms of Hg content in the livers of rodents was located in the western part of the Upper Silesian Industrial District, which is known as one of the most polluted parts of Poland and is mainly associated with coal mining and metal production. Mercury levels in this area could be three- to sixfold higher than in rural areas in Poland [33], which our findings confirm.

The mean concentration of Hg found in the livers of all species of rodents from the most polluted DAB site (15 µg/kg of wet weight) was one-seventh of the level of Hg found in the livers of A. flavicollis from areas polluted by lead smelting in Slovenia, but threefold higher than that observed in the same species captured in the area contaminated by power plant emissions in that country [34]. Much higher levels than ours were found in Microtus guentheri from the marble mining area in Turkey [35], in M. glareolus from the zone around a chlor-alkali plant in Great Britain [36], and in Apodemus sylvaticus from different polluted and unpolluted areas in Galicia in northern Spain [37]. However, threefold lower Hg levels were noted in M. glareolus inhabiting the area affected by metal-processing industry in Russia [18]. Literature data on Hg levels in the livers of wild rodents are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Concentrations of Hg in the livers of small terrestrial mammals from different areas (in µg/kg of wet weight).

| Species | Country | Site | N | Mean (Min–Max) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apodemus flavicollis | Slovenia | lead smelter | 7 | 100.3 (39.5–249.3) * | [34] |

| main road | 23 | 6.1 (3–21.3) * | |||

| thermal power plant | 30 | 42.6 (3–173.3) * | |||

| reference area | 13 | 18.2 (3–36.5) * | |||

| Apodemu sylvaticus | Great Britain | chlor-alkali plant | 6 | 230 (90–530) | [36] |

| reference area | 10 | 40 (10–70) | |||

| Spain | Galicia, different areas | 372 | 53 (17–110) | [37] | |

| Chaetidypus penicillatus | NV, USA | Las Vegas Wash | 32 | 3.3 (0.9–24.3) | [49] |

| Dipodomys merriami | 8 | 3.7 (0.7–20.6) | |||

| Microtus arvalis | Slovenia | thermal power plant | 4 | 3 (<LOQ–10) * | [34] |

| main road | 3 | 3 * | |||

| Microtus guentheri | Turkey | marble mining area | 68 | 231 (221.9–240.1) * | [35] |

| reference area | 24 | 200.6 (145.9–240.1) * | |||

| Mus musculus | NV, USA | Las Vegas Wash | 2 | 2.3 (1.5–3.0) | [49] |

| Myodes glareolus | Slovenia | lead smelter | 21 | 9.1* | [34] |

| main road | 13 | 3 (3–6.1) * | |||

| thermal power plant | 4 | 97.3 (3–231) * | |||

| reference area | 15 | 18.2 (3–36.5) * | |||

| Russia | metallurgical plant | 50 | 4.3 * | [18] | |

| Great Britain | chlor-alkali plant | 7 | 150 (60–340) | [36] | |

| reference area | 6 | 60 (30–130) | |||

| Neotoma lepida | NV, USA | Las Vegas Wash | 16 | 6.8 (2.0–20.8) | [49] |

| Peromyscus leucopus | IL, USA | contaminated wetland | 36 | 11 (2–23) | [50] |

| reference area 1 | 84 | 10 (1–21) | |||

| reference area 2 | 43 | 8 (1–20) | |||

| reference area 3 | 43 | 15 (3–35) | |||

| Peromyscus maniculatus | MI, USA | outside Sargent Lake watershed | 15 | 29.98 | [51] |

| inside Sargent Lake watershed | 15 | 10.99 | |||

| mainland | 4 | 21.41 | |||

| Peromyscus eremicus | NV, USA | Las Vegas Wash | 46 | 10.9 (0.9–85.3) | [49] |

* Results calculated from original data given on dry wt. basis assuming 30.4% of solids.

Mercury can accumulate along the trophic gradient in food webs, and the level of this element increases with the higher trophic position of animals [3,18]. However, the bioaccumulation of Hg may depend on dietary protein level and glutathione metabolism [38] and on the role of gut microbiota in demethylation and excretion of Hg [39]. The lowest liver Hg levels were found in A. flavicollis. Our results are in line with the results of Martiniaková et al. [40], who found that A. flavicollis was a biomonitor with lower metal concentration than M. glareolus. Mice of the Apodemus species have a more variable and protein-rich diet than herbivorous voles [41], and the richness of diet may result in lower bioaccumulation of toxic elements due to “diet dilution” [42]. We hypothesize that mycophagy could be another explanation for species-specific differences in liver Hg concentration in rodents. Fungi can accumulate Hg from the environment, and Hg levels in fruiting bodies could be higher than 4 mg/kg of dry weight [43,44,45]. In our study, all rodents were captured from early summer to the end of October, when fungi were readily available. Blaschke and Bäumler reported that fungal spores can account for 7% of the stomach volume of A. flavicollis and up to 36% of the stomach content of M. glareolus [46]. Besides species-specific feeding habits, the frequency of mycophagy in rodents also depends on the availability of this dietary component during the year. The analysis of fungal spores in fresh fecal pellets of rodents showed that they were present in almost 100% of examined individuals of M. glareolus during summer and autumn, whereas in Apodemus spp., only 30–40% of individuals consumed fungi during summer, although the frequency increased to approximately 80% in autumn [47]. The bioaccumulation of Hg may be different between the sexes. Lower levels of Hg in female mammals may be due to depuration during lactation [48].

The higher Hg concentrations in the livers of rodents found in our study corroborate the results reported by Sánchez-Chardi in white-toothed shrews (Crocidura russula) [52]. We are aware that the lack of the ages of the rodents, whch were not recorded during the study, is a limitation of our research. The estimation of the age of rodents by body size could be imprecise because different factors affect their growth [53]. Nevertheless, we found a positive correlation between body weight and liver Hg in rodents, which could be explained by the accumulation of Hg within their lifespan. Our study showed that the concentration of Hg in the liver of wild rodents may depend on different factors, including the level of exposure in their habitat, species, sex, and b.w. We suspect that differences in liver Hg concentrations between species of rodents may be caused by feeding habits, and future studies are needed to investigate the potential sources of Hg in their diet.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sampling

A total of 221 free-living small rodents were captured between June 2016 and October 2017 in 12 study sites (counties) of central, southeastern, and eastern Poland. The characteristics of all study sites, including mean annual temperature, annual rainfall, altitude, type of vegetation, and background soil Hg, and the number of animals sampled per species and sex are summarized in Supplementary Table S1. All animals were caught by a standard live-trapping technique in their natural foraging areas located close to farm buildings, using Sherman traps with baits of cereal grain and fresh apple. Four species of wild rodents were chosen: the bank vole (M. glareolus), common vole (M. arvalis), striped field mouse (A. agrarius), and yellow-necked mouse (A. flavicollis). Live animals were transported to the laboratory and euthanized, and necropsies were performed in a laminar chamber on the same day as capture. Liver samples were taken using stainless-steel surgical scissors, placed in 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes, and frozen at −20 °C until analysis. The sampling of rodents was performed within a project that was focused on small mammals as sentinels for multiple zoonotic pathogens and was approved by the Local Ethics Committee for Animal Experimentation in Lublin under Resolution No. 30/2016. No ethical committee permission was required for the analysis of Hg, as the samples were taken post-mortem for this purpose.

4.2. Mercury Analysis

Frozen samples were thawed at 4 °C. The analysis of Hg in liver tissue was performed in raw tissue by a previously described method [54] using a Tri-cell DMA-80® direct mercury analyzer (Milestone Srl, Sorisole (BG), Italy). Quantification of Hg was based on external calibration curves in three independent working ranges. Standard solutions (from 3 to 30, from 3 to 150, and from 250 to 10,000 µg/L) were prepared by dilution of an Hg standard stock solution (J.T. Baker, 1000 mg/L) (Avantor Performance Materials B.V, Deventer, the Netherlands) with 1% (v/v) nitric acid (Suprapur®, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Briefly, using an ENTRIS 224l-1S analytical balance (Sartorius Lab Instruments GmbH & Co, Goettingen, Germany) approximately 50 ± 0.1 mg of liver tissue was weighed into nickel boats and placed on the autosampler rotor of the DMA-80. The analysis took 5.5 min per sample. The operating conditions are shown in Supplementary Table S2. Quality control of the measurements was provided by using the following certified reference materials (CRMs): SRM-1577c Bovine Liver (National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), Gaithersburg, MD, USA), Chicken ZC73016 (NCS Testing Technology Co., Beijing, China), and MODAS-3 Herring tissue (M-3 HerTis) (Institute of Nuclear and Technology (IChTJ), Warsaw, Poland). Recoveries of Hg in CRMs were 98%, 122%, and 97% for SRM-1577c, ZC73016, and M-3 HerTis, respectively. The limit of quantification of the method was 1 µg/kg of wet weight. The method is accredited according to ISO/IEC 17025/Ap1:2007 [55] and regularly verified in proficiency tests organized by the European Union Reference Laboratory for Metals and Nitrogenous Compounds in Feed and Food (EURL-MN) in Lyngby, Denmark.

We also measured the moisture content in the livers of rodents to facilitate the comparison of our results with literature data. The moisture content was analyzed in 16 randomly selected subsamples of the liver using an HR83 moisture analyzer (Mettler Toledo, Switzerland) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The mean content of dry matter in the liver of rodents was 30.4%, and this level was used for calculations. All of the results in this article are expressed in µg/kg of wet weight.

4.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R in version 3.6.0 [56]. The data handling and descriptive statistics calculation, including mean, standard deviation, median, median absolute deviation (MAD), and range were performed in the dplyr package, version 0.8.1 [57]. Results below LOQ were set as 0.5 of the LOQ. The Shapiro–Wilk normality test was used to verify the normality of distribution [58], and because data were not normally distributed, we used log-transformation to achieve the normality. Effects of species, study site, sex, season of sampling (summer and autumn), feeding habits (omnivores and herbivores), and body weight were verified using GLM [59]. We constructed GLM with Gaussian distribution as follows: log-transformed Hg concentration was used as the dependent variable, and all factors (species, study site, sex, season of sampling, feeding habit, and body weight) were used as predictors. The best model was chosen by the step command with forward–backward stepwise procedure based on Akaïke’s Information Criterion (AIC). Differences between factor levels were verified by post-hoc tests with Bonferroni adjustment of p-values on estimated marginal means using version 1.4.1 of the emmeans package [60]. The Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used to verify the relationship between Hg accumulation in the liver and the b.w. The results were visualized using the ggplot2 package (version 3.2.1) [61], and the map with estimated marginal mean concentrations of Hg in the livers of rodents in selected study sites was plotted by QGIS software version 3.8 [62].

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to Scott Carter for English proofreading.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online. Supplementary Table S1 of the characteristics of study sites and the number of rodents captured according to study site, species, and sex; Supplementary Table S2 of the DMA-80 operating conditions; Supplementary Table S3 of the descriptive statistics of Hg concentrations in the liver of rodents according to their species, sampling site, and sex (µg/kg); Supplementary Table S4 of the differences in liver Hg concentrations in rodents between study sites; Supplementary Table S5 of the differences in liver Hg concentrations in rodents between species; and Supplementary Table S6 of the differences in liver Hg concentrations in rodents between females and males.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D. and A.N.; methodology, A.N.; formal analysis, M.D.; investigation, M.D. and A.F.; resources, M.N. and J.Ż.; supervising, A.P; writing—original draft preparation, M.D. and A.N; writing—review and editing, A.P., M.N., and J.Ż.; visualization, M.D.; funding acquisition, J.Ż. and M.D.

Funding

This research was funded by the KNOW (Leading National Research Centre) Scientific Consortium “Healthy Animal-Safe Food”, decision of Ministry of Science and Higher Education Resolution No. 05-1/KNOW2/2015, and sampling was supported by the National Science Centre, Krakow, Poland, grant number DEC-2013/09/B/NZ7/02563.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds and biological material used in this study are not available from the authors.

References

- 1.Driscoll C.T., Mason R.P., Chan H.M., Jacob D.J., Pirrone N. Mercury as a Global Pollutant: Sources, Pathways, and Effects. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013;47:4967–4983. doi: 10.1021/es305071v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clarkson T.W., Magos L. The toxicology of mercury and its chemical compounds. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2006;36:609–662. doi: 10.1080/10408440600845619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boening D.W. Ecological effects, transport, and fate of mercury: A general review. Chemosphere. 2000;40:1335–1351. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(99)00283-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.UN Environment . Global Mercury Assessment 2018. UN Environment Programme Economy Division Chemicals and Health Branch International Environment House; Geneva, Switzerland: 2019. pp. 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- 5.KOBiZE . Poland’s Informative Inventory Rreport 2018. Submission under the UN ECE Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution and the DIRECTIVE (EU) 2016/2284. National Centre for Emission Management (KOBiZE) at the Institute of Environmental Protection—National Research Institute; Warsaw, Poland: 2018. pp. 1–286. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pyka I., Wierzchowski K. Estimated mercury emissions from coal combustion in the households sector in Poland. J. Sustain. Min. 2016;15:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jsm.2016.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu J., Buck M., Eklöf K., Ahmed O.O., Schaefer J.K., Bishop K., Skyllberg U., Björn E., Bertilsson S., Bravo A.G. Mercury methylating microbial communities of boreal forest soils. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-37383-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsz-Ki Tsui M., Liu S., Brasso R.L., Blum J.D., Kwon S.Y., Ulus Y., Nollet Y.H., Balogh S.J., Eggert S.L., Finlay J.C. Controls of Methylmercury Bioaccumulation in Forest Floor Food Webs. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019;53:2434–2440. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b06053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodríguez Álvarez C., Jiménez-Moreno M., Guzmán Bernardo F.J., Rodríguez Martín-Doimeadios R.C., Berzas Nevado J.J. Using species-specific enriched stable isotopes to study the effect of fresh mercury inputs in soil-earthworm systems. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018;147:192–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2017.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abeysinghe K.S., Yang X.-D., Goodale E., Anderson C.W.N., Bishop K., Cao A., Feng X., Liu S., Mammides C., Meng B., et al. Total mercury and methylmercury concentrations over a gradient of contamination in earthworms living in rice paddy soil. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2017;36:1202–1210. doi: 10.1002/etc.3643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ortiz C., Weiss-Penzias P.S., Fork S., Flegal A.R. Total and Monomethyl Mercury in Terrestrial Arthropods from the Central California Coast. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2015;94:425–430. doi: 10.1007/s00128-014-1448-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng D., Liu X., Jin D., Li H., Li X. Mercury bioaccumulation in arthropods from typical community habitats in a zinc-smelting area. Environ. Geochem. Health. 2018;40:1329–1337. doi: 10.1007/s10653-017-0059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janiga M., Haas M. Alpine accentors as monitors of atmospheric long-range lead and mercury pollution in alpine environments. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019;26:2445–2454. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-3742-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson A.K., Evers D.C., Adams E.M., Cristol D.A., Eagles-Smith C., Edmonds S.T., Gray C.E., Hoskins B., Lane O.P., Sauer A., et al. Songbirds as sentinels of mercury in terrestrial habitats of eastern North America. Ecotoxicology. 2015;24:453–467. doi: 10.1007/s10646-014-1394-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Costa R.A., Eeva T., Eira C., Vaqueiro J., Vingada J.V. Assessing heavy metal pollution using Great Tits (Parus major): Feathers and excrements from nestlings and adults. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2013;185:5339–5344. doi: 10.1007/s10661-012-2949-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korstian J.M., Chumchal M.M., Bennett V.J., Hale A.M. Mercury contamination in bats from the central United States. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2018;37:160–165. doi: 10.1002/etc.3940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sánchez-Chardi A., López-Fuster M.J., Nadal J. Bioaccumulation of lead, mercury, and cadmium in the greater white-toothed shrew, Crocidura russula, from the Ebro Delta (NE Spain): Sex- and age-dependent variation. Environ. Pollut. 2007;145:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2006.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Komov V.T., Ivanova E.S., Poddubnaya N.Y., Gremyachikh V.A. Mercury in soil, earthworms and organs of voles Myodes glareolus and shrew Sorex araneus in the vicinity of an industrial complex in Northwest Russia (Cherepovets) Environ. Monit. Assess. 2017;189:104. doi: 10.1007/s10661-017-5799-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Antonova E.P., Ilyukha V.A., Komov V.T., Khizhkin E.A., Sergina S.N., Gremyachikh V.A., Kamshilova T.B., Belkin V.V., Yakimova A.E. The Mercury Content and Antioxidant System in Insectivorous Animals (Insectivora, Mammalia) and Rodents (Rodentia, Mammalia) of Various Ecogenesis Conditions. Biol. Bull. 2017;44:1272–1277. doi: 10.1134/S1062359017100028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalisinska E., Lisowski P., Kosik-Bogacka D.I. Red Fox Vulpes vulpes (L, 1758) as a Bioindicator of Mercury Contamination in Terrestrial Ecosystems of North-Western Poland. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2012;145:172–180. doi: 10.1007/s12011-011-9181-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalisinska E., Lisowski P., Salicki W., Kucharska T., Kavetska K. Mercury in wild terrestrial carnivorous mammals from north-western Poland and unusual fish diet of red fox. Acta Theriol. 2009;54:345–356. doi: 10.4098/j.at.0001-7051.032.2008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalisińska E., Łanocha-Arendarczyk N., Kosik-Bogacka D.I. Mammals and Birds as Bioindicators of Trace Element Contaminations in Terrestrial Environments. Springer International Publishing; Cham, Switzerland: 2019. Mercury, Hg; pp. 593–653. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wren C.D. Mammals as biological monitors of environmental metal levels. Environ. Monit. Assess. 1986;6:127–144. doi: 10.1007/BF00395625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Talmage S.S., Walton B.T. Small mammals as monitors of environmental contaminants. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1991;119:47–145. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4612-3078-6_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mazurkiewicz M. Factors influencing the distribution of the bank vole in forest habitats. Acta Theriol. 1994;39:113–126. doi: 10.4098/AT.arch.94-16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Butet A., Delettre Y.R. Diet differentiation between European arvicoline and murine rodents. Acta Theriol. 2011;56:297. doi: 10.1007/s13364-011-0049-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lundrigan B., Mueller M. Myodes glareolus (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. [(accessed on 1 October 2019)]; Available online: https://animaldiversity.org/site/accounts/information/Myodes_glareolus.html.

- 28.Noble S. “Microtus arvalis” (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. [(accessed on 1 October 2019)]; Available online: https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Microtus_arvalis/

- 29.Jacob J., Manson P., Barfknecht R., Fredricks T. Common vole (Microtus arvalis) ecology and management: Implications for risk assessment of plant protection products. Pest Manag. Sci. 2014;70:869–878. doi: 10.1002/ps.3695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kowalski K., Pucek Z., Ruprecht A.L. Rząd: Gryzonie—Rodentia. In: Pucek Z., editor. Klucz do Oznaczania Ssaków Polski. PWN; Warsaw, Poland: 1984. pp. 149–240. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gortat T., Barkowska M., Gryczyńska-Siemiątkowska A., Pieniążek A., Kozakiewicz A., Kozakiewicz M. The Effects of Urbanization—Small Mammal Communities in a Gradient of Human Pressure in Warsaw City, Poland. Polish J. Ecol. 2014;62:163–172. doi: 10.3161/104.062.0115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zielonka U., Hlawiczka S., Fudala J., Wängberg I., Munthe J. Seasonal mercury concentrations measured in rural air in Southern Poland: Contribution from local and regional coal combustion. Atmos. Environ. 2005;39:7580–7586. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2005.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pyta H., Rosik-Dulewska C., Czaplicka M. Speciation of Ambient Mercury in the Upper Silesia Region, Poland. Water. Air. Soil Pollut. 2009;197:233–240. doi: 10.1007/s11270-008-9806-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Al Sayegh Petkovšek S., Kopušar N., Kryštufek B. Small mammals as biomonitors of metal pollution: A case study in Slovenia. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2014;186:4261–4274. doi: 10.1007/s10661-014-3696-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yavuz M., Aktas O. Heavy metal accumulation in the Microtus guentheri (Danford and Alston, 1880) living near the mines as biomonitor. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2017;26:1104–1121. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bull K.R., Roberts R.D., Inskip M.J., Goodman G.T. Mercury concentrations in soil, grass, earthworms and small mammals near an industrial emission source. Environ. Pollut. 1977;12:135–140. doi: 10.1016/0013-9327(77)90016-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ángel Fernández J., Aboal J.R., González X.I., Carballeira A. Transfer and bioaccumulation variability of Cd, Co, Cr, Hg, Ni and Pb in trophic compartments of terrestrial ecosystems in Northern Spain. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2012;21:3527–3532. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adachi T., Yasutake A., Eto K., Hirayama K. Influence of dietary protein levels on the acute toxicity of methylmercury in mice. Toxicology. 1996;112:11–17. doi: 10.1016/0300-483X(96)03340-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rowland I.R., Robinson R.D., Doherty R.A. Effects of diet on mercury metabolism and excretion in mice given methylmercury: Role of gut Flora. Arch. Environ. Health. 1984;39:401–408. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1984.10545872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martiniaková M., Omelka R., Grosskopf B., Jančová A. Yellow-necked mice (Apodemus flavicollis) and bank voles (Myodes glareolus) as zoomonitors of environmental contamination at a polluted area in Slovakia. Acta Vet. Scand. 2010;52:58. doi: 10.1186/1751-0147-52-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Čepelka L., Heroldová M., Jánová E., Suchomel J. The dynamics of nitrogenous substances in rodent diet in a forest environment. Mammalia. 2014;78:327–333. doi: 10.1515/mammalia-2013-0017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ozaki S., Fritsch C., Valot B., Mora F., Cornier T., Scheifler R., Raoul F. How Do Richness and Composition of Diet Shape Trace Metal Exposure in a Free-Living Generalist Rodent, Apodemus sylvaticus. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019;53:5977–5986. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b07194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Falandysz J., Krasińska G., Pankavec S., Nnorom I.C. Mercury in certain boletus mushrooms from Poland and Belarus. J. Environ. Sci. Health B. 2014;49:690–695. doi: 10.1080/03601234.2014.922853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Falandysz J., Szymczyk K., Ichihashi H., Bielawski L., Gucia M., Frankowska A., Yamasaki S.I. ICP/MS and ICP/AES elemental analysis (38 elements) of edible wild mushrooms growing in Poland. Food Addit. Contam. 2010;18:503–513. doi: 10.1080/02652030119625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rieder S.R., Brunner I., Horvat M., Jacobs A., Frey B. Accumulation of mercury and methylmercury by mushrooms and earthworms from forest soils. Environ. Pollut. 2011;159:2861–2869. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2011.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blaschke H., Bäumler W. Mycophagy and spore dispersal by small mammals in bavarian forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 1989;26:237–245. doi: 10.1016/0378-1127(89)90084-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kataržytė M., Kutorga E. Small mammal mycophagy in hemiboreal forest communities of Lithuania. Cent. Eur. J. Biol. 2011;6:446–456. doi: 10.2478/s11535-011-0006-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wada H., Yates D.E., Evers D.C., Taylor R.J., Hopkins W.A. Tissue mercury concentrations and adrenocortical responses of female big brown bats (Eptesicus fuscus) near a contaminated river. Ecotoxicology. 2010;19:1277–1284. doi: 10.1007/s10646-010-0513-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gerstenberger S.L., Cross C.L., Divine D.D., Gulmatico M.L., Rothweiler A.M. Assessment of mercury concentrations in small mammals collected near Las Vegas, Nevada, USA. Environ. Toxicol. 2006;21:583–589. doi: 10.1002/tox.20221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Levengood J.M., Heske E.J. Heavy metal exposure, reproductive activity, and demographic patterns in white-footed mice (Peromyscus leucopus) inhabiting a contaminated floodplain wetland. Sci. Total Environ. 2008;389:320–328. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2007.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vucetich L., Vucetich J., Cleckner L., Gorski P., Peterson R. Mercury concentrations in deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus) tissues from Isle Royale National Park. Environ. Pollut. 2001;114:113–118. doi: 10.1016/S0269-7491(00)00199-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sánchez-Chardi A., López-Fuster M.J. Metal and metalloid accumulation in shrews (Soricomorpha, Mammalia) from two protected Mediterranean coastal sites. Environ. Pollut. 2009;157:1243–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2008.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Adamczewska-Andrzejewska K.A. Methods of age determination in Apodemus agrarius (Pallas 1771) Ann. Zool. Fenn. 1971;8:68–71. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Szkoda J., Zmudzki J., Grzebalska A. Determination of total mercury in biological material by atomic absorption spectrometry method. Bull. Vet. Inst. Pulawy. 2006;50:363–366. [Google Scholar]

- 55.International Standard Organization ISO/IEC 17025 General requirements for the competence of testing and calibration laboratories. Int. Stand. 2005;2005:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 56.R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Version 3.6.0. [(accessed on 1 October 2019)]; Available online: http://www.r-project.org/

- 57.Wickham H., Romain F., Lionel H., Müller K. dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation. R Package Version 0.8.1. [(accessed on 1 October 2019)]; Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=dplyr.

- 58.Yap B.W., Sim C.H. Comparisons of various types of normality tests. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 2011;81:2141–2155. doi: 10.1080/00949655.2010.520163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zuur A.F., Ieno E.N., Walker N., Saveliev A.A., Smith G.M. In: Mixed Effects Models and Extensions in Ecology with R. Krämer A., Kretzschmar M., Krickeberg K., editors. Springer; New York, NY, USA: 2009. pp. 1–574. Statistics for Biology and Health. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lenth R. emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. R Package Version 1.4.1. [(accessed on 1 October 2019)]; Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=emmeans.

- 61.Wickham H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. 2nd ed. Springer; New York, NY, USA: 2016. pp. 1–260. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Team Q.D. QGIS Geographic Information System. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project. [(accessed on 1 October 2019)]; Version 3.8. Available online: http://qgis.osgeo.org/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.