Abstract

The benefits of diploidy are considered to involve masking partially recessive mutations and increasing genetic diversity. Here, we review new studies showing evidence for diverse allele-specific expression and epigenetic states in mammalian brain cells, which suggest that diploidy expands the landscape of gene regulatory and expression programs in cells. Allele-specific expression has been thought to be restricted to a few specific classes of genes. However, new studies show novel genomic imprinting effects that are brain region, cell-type and age dependent. In addition, novel forms of random monoallelic expression that impact many autosomal genes have been described in vitro and in vivo. We discuss the implications for understanding the benefits of diploidy, and the mechanisms shaping brain development, function and disease.

Keywords: epigenetics, genomic imprinting, random monoallelic, gene expression, behavioral genetics, brain development

The Landscape of Allelic Effects

By controlling spatial and temporal patterns of gene activity in response to physiological and environmental cues, gene regulatory mechanisms shape the development and function of the myriad of different cell types that compose the brain. The regulatory mechanisms governing gene activity in the brain are typically thought to apply similarly to the maternal and paternal alleles (see Glossary) for a given gene, such that the two alleles function as redundant backup copies. Established exceptions to this rule include canonical genomic imprinting [1], which silences one parental allele in offspring; random X-inactivation in females [2,3], allelic exclusion of immunoglobulins [4], as well as random monoallelic expression of clustered protocadherins [5] and olfactory receptors [6]. Many of these cases involve genes with a uniquely clustered genomic organization. However, there is growing evidence for other forms of allele-specific gene regulation and expression, some of which have been comprehensively reviewed elsewhere [7–9]. Here, we review recent developments in this area that may advance our understanding of the function of diploidy, and open new opportunities for investigating how gene expression at the allele and cellular level shapes brain development, function and brain disorders.

Ploidy: Why have two (or more) alleles?

Diploidy is often considered to have evolved to mask deleterious partially recessive mutations [10], implying that maternal and paternal alleles are only backup copies for each other – similarly regulated and expressed. However, the details are more nuanced. If diploidy only masks deleterious recessive mutations, then haploinsufficiency in the absence of such mutations should not be a significant factor in shaping phenotypes and disease risks. To the contrary, recent large-scale mutant mouse phenotyping studies found that haploinsufficiency frequently had phenotypic effects, impacting 42% of the 90 genes tested [11]. In humans, hundreds to thousands of genes are predicted to be haploinsufficient, depending on the threshold criteria [12,13], and the growing wealth of human genome data indicates that heterozygous mutations impacting gene dosage contribute substantially to disease risks. Indeed, for autism and schizophrenia, many known risk mutations are heterozygous, and haploinsufficiency at certain genes increases liability and causes behavioral phenotypes in mouse models [14–17]. Furthermore, potent mechanisms other than diploidy exist to promote biological robustness. Gene duplications can provide functional redundancy [18] and several features of gene regulatory networks promote mutational robustness [19]. Thus, there are likely advantages to diploidy beyond promoting robustness to mutations.

Another ploidy state prevalent in nature, particularly among invertebrates [20], is haploidy. Haploidy has the advantage of efficiently eliminating deleterious mutations in a population, and selecting for beneficial ones [10], whereas diploidy increases genetic variation (deleterious and beneficial) by doubling the number of possible alleles. Consequently, diploidy is postulated to be advantageous when evolutionary change is limited by genetic diversity, and haploidy is advantageous when change is limited by selection [10]. The capacity for heterozygosity in the diploid state also has benefits by diversifying the functional effects of the allelic copies of a gene within an individual. One example of the effects of allelic diversity is heterosis (hybrid vigor), in which the mating of two genetically different individuals generates a phenotype that is distinct from, rather than intermediate to, the parental phenotypes [21,22]. Currently, it is not clear how increased heterosis arises from increased allelic diversity [23]. Few studies of heterosis exist for the brain, but cases are reported for myelination and anxiety in mice, and it is proposed to be a factor shaping phenotypic variance in psychiatric disorders [22]. The ability of diploidy to diversify gene function and create new phenotypic effects is an important concept that we consider further below.

Allele number is expanded beyond diploidy in some mammalian cell types. Megakaryocytes, hepatocytes, muscle cells and placental trophoblast giant cells, for example, exhibit varying degrees of polyploidization, ranging from tetraploidy (4N) in hepatocytes to over 100N for some megakaryocytes [24,25]. Vertebrate tetraploid neurons were first reported around 1970 [26] but were not widely accepted due to the technical limitations of the time [27]. More recent studies using advanced techniques have identified regional subpopulations of tetraploid neurons in the rodent cortex and striatum [28,29] and human entorhinal cortex [30]. Many cases involve large, projection neurons. Interestingly, other recent work found regional and individual differences in neuronal DNA content, such that a substantial fraction of neurons were found to have DNA content exceeding the diploid level, but not reaching the tetraploid level in the brain [31–33].

The advantages of increasing allele number are debated, but accumulating evidence suggests benefits for increasing stress tolerance and surviving unpredictable environmental stressors [24,34]. For example, whole genome duplication events occurred across various taxa in correlation with periods of mass extinction due catastrophic environmental events, such as the comet or asteroid strike and volcanic eruptions at the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary [24]. Further, all recent polyploid animal taxa are ectotherms, which are more strongly impacted by environmental change than endotherms [24]. In human and mouse hepatocytes, polyploidization increases with age, injury and infection [25]. In the brain, tetraploid neurons are reported to increase in number with age and in association with degenerative diseases, like Alzheimer’s Disease [35].

Increases in ploidy are typically considered a product of selection for changes to genetic diversity. Less consideration has been given to the idea that diploidy and polyploidy function to increase epigenetic diversity. From recent studies detailed below, we provide evidence that allele-specific epigenetic and gene expression effects expand the diversity of gene regulatory and expression programs available to cells with increased ploidy. These new findings may change our understanding of the benefits of diploid and polyploid states, and reveal new questions about the mechanisms shaping brain development, function and disease.

Maternal and Paternal Imprinted Genes in the Brain

Genomic imprinting is a deterministic form of allele-specific expression in which the maternally or paternally inherited allele is preferentially expressed due to heritable epigenetic mechanisms [1]. One well-studied example in the brain is UBE3A, a maternally expressed gene (MEG) located among a cluster of imprinted genes on human chromosome 15 [36]. Maternally inherited mutations or deletions in UBE3A cause Angelman syndrome. UBE3A imprinting is regulated by expression of an anti-sense transcript, UBE3A-ATS, which arises from a nearby imprinting control region (ICR) that is methylated only on the maternal allele, and not the paternal allele. The UBE3A-ATS transcript partially overlaps the UBE3A gene, blocking UBE3A expression from the paternal allele. Thus, regulating the expression of this overlapping noncoding antisense transcript in a developmental stage and cell-type dependent manner, can similarly regulate UBE3A imprinting.

Ube3a is widely expressed in the mouse brain and imprinted expression emerges between birth and postnatal day (P)7 in cortical neurons. However, Ube3a imprinted expression doesn’t occur in oligodendrocytes and some select neuron populations in the brain [37,38], revealing highly cell type specific effects. Surprisingly, persistent expression of the paternal Ube3a allele was recently uncovered in a subset of neurons in the adult suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), which regulates circadian rhythm [39]. This may have important functional consequences because a maternally-inherited deletion in Ube3a causes many phenotypic effects, including altered sleep homeostasis, but circadian rhythms of behavior are relatively normal [40]. Indeed, therapeutic strategies have been developed in mice to potentially treat Angelman Syndrome by activating the silent paternal Ube3a allele in the brain [41–43]. The results indicate that the expression of a healthy Ube3a allele can reduce the impact of deleterious mutations in the maternal allele in mice, depending on the age of rescue. The case of UBE3A/Ube3a illustrates how complex developmental stage and cell-type dependent imprinting in the brain can shape disease risks and reveal new therapeutic interventions.

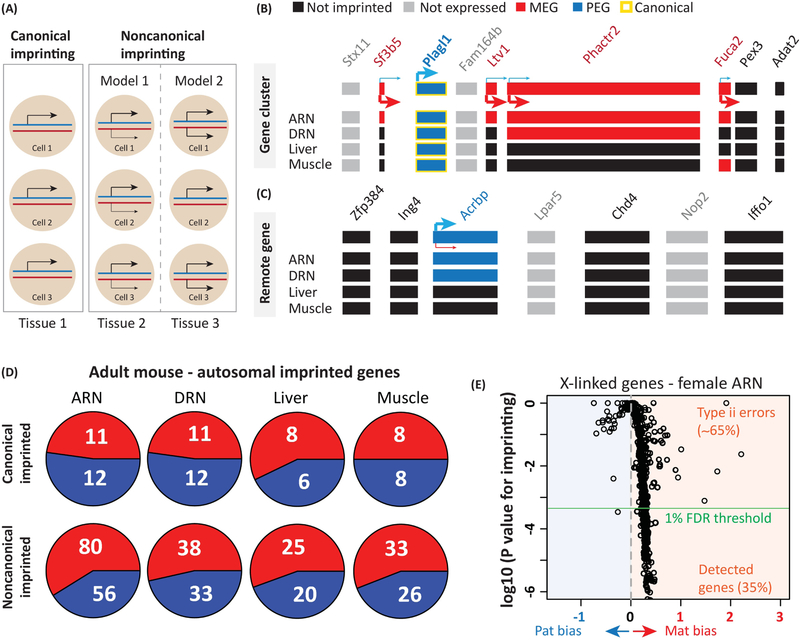

There is interest in more deeply understanding the landscape of imprinting in the brain and other tissues. Recent efforts focusing on this problem learned that complex tissue and developmental stage dependent imprinting effects are frequent in mice [44–47] and humans [48,49]. We [44], and others [45], have especially focused on “noncanonical” genomic imprinting effects (also called parental allele biases). Canonical imprinting is typically considered to involve complete silencing of one parental allele. Accordingly, we previously defined canonical imprinted genes in the mouse as the subset with monoallelic expression at the tissue level [44] (Fig. 1A–C). However, we and others also observed a subset of genes with a significant maternal or paternal allele expression bias, which we refer to as noncanonical imprinting [44] (Fig. 1A–C). Noncanonical imprinted genes are more numerous than canonical imprinted genes and especially prevalent in the brain [44] (Fig. 1D). We observed that noncanonical imprinting can arise near clusters of canonical imprinted genes in the genome, indicating that the imprinting effect at these loci can influence neighboring genes in a tissue dependent manner (Fig. 1B). This observation was recently confirmed by others and described across a large number of mouse tissues and ages [46]. Noncanonical imprinted genes also reside in genomic regions that are distant and isolated from other imprinted genes [44] (Fig. 1C), suggesting multiple mechanisms contribute to this effect. Noncanonical imprinting is reproducible with various methods, manifests at the level of chromatin, exists in different mouse lines and is found in wild-derived populations [44]. However, its function and cellular mechanisms are poorly understood.

Figure 1. Canonical and noncanonical imprinting in the brain and body.

(A) Canonical imprinting involves allele silencing at the tissue and cellular level. Noncanonical imprinting involves a bias to express one parental allele over the other at the tissue level, and could involve an allelic expression bias or cell-type specific imprinting at the cellular level.

(B) Noncanonical imprinting in mice can arise in a tissue and age dependent manner for genes near canonical imprinted genes. Shown is the case of noncanonical imprinted genes near the canonical PEG, Plagl1 (from [44]). Plagl1 exhibits canonical imprinting in all tissues shown, but the neighboring genes exhibit tissue specific maternal allele expression biases. ARN, arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus; DRN, dorsal raphe nucleus of the midbrain; Muscle, skeletal muscle

(C) Tissue-specific noncanonical imprinting also arises in mouse genome for genes that are not near other imprinted genes, such as the noncanonical PEG, Acrbp. (from [44])

(D) Estimated numbers of canonical and noncanonical PEGs (blue) and MEGs (red) in different tissues of adult mice (from [44]).

(E) In mice, a bias to silence the paternally inherited X chromosome occurs in females and as a consequence the majority of X-linked genes exhibit a maternal allele expression bias. The detection rate of this noncanonical imprinting pattern for individual X-linked genes is a simple internal metric for type II errors for imprinting studies. The data shows the maternal bias for most X-linked genes in the female ARN relative to the p-value for imprinting. At a 1% FDR threshold, only 35% of the maternally biased X-linked genes are detected, revealing type II errors (~65%). Figure adapted from [44].

Mounting evidence indicates that imprinting effects are more regulated at the cellular level than was previously appreciated. Beyond UBE3A/Ube3a, other genes have been shown to have cell-type specific imprinting effects in the brain [7]. In fact, rather than an allele expression bias, noncanonical imprinting effects could be due to cell-type specific imprinting effects (Fig. 1A). In support of this model, the strength of noncanonical imprinting effects can differ significantly between brain regions [44], presumably from differences in number and/or spatial distribution of cells that express both alleles (biallelic) or only one allele (monoallelic). Using nascent RNA in situ hybridization, we uncovered evidence that stronger noncanonical imprinting effects in a given brain region are associated with more monoallelic brain cells, suggesting highly brain region and cell-type dependent allelic effects for at least some noncanonical imprinted genes [44].

To study DNA methylation patterns at the cellular level in vivo, a recent series of creative studies developed the ICR from the Prader-Willi Syndrome – Angelman Syndrome (PWS-AS) imprinted gene cluster as a reporter system for DNA methylation dynamics, using green fluorescent protein expression (GFP) as a readout for the presence (GFP-) versus absence (GFP+) of methylation in cells [50,51]. By fusing the PWS-AS ICR to the ICR for the Dlk1-Dio3 imprinted gene cluster, the authors were able to analyze parent-of-origin DNA methylation dynamics over development and at the cellular level in mice [50,51]. The study shows that DNA methylation at imprinting control regions can be regulated in a complex developmental stage, tissue and cell-type dependent manner. Mosaic imprinting was observed in adult brain cells, including Purkinje neurons, and imprinting was absent from astrocytes and neural stem cells, as previously reported [52]. Inter-individual variation in imprinting was also prevalent. Since complex tissue and isoform specific imprinted transcripts have been described in humans [48,49,53], deeper analyses at the cellular level may reveal new cellular diversity in human imprinting, as in mice.

Imprinted genes are sources of maternal and paternal influence on gene expression in offspring and there is interest in learning the relative roles and numbers of MEGs and paternally expressed genes (PEGs) in the brain [54]. We observe more MEGs than PEGs in the mouse brain and the effect is largely driven by more maternally-expressed noncanonical imprinted genes (Fig. 1D) [44]. In recent studies, we reproduced this overall MEG bias for different ages (supplement in [55]). Not all studies agree with this observation. One group reported widespread paternal allele expression biases in the mouse genome [47]. Though it is not known whether the following contributed to the discrepancy between the studies, in our experience, widespread paternal allele biases can emerge during steps to normalize replicates for the total reads generated per sample. The effect emerges because of the maternal bias for mitochondrial genes and X-linked genes. The X chromosome is maternally-derived in males and a bias to express the maternal X chromosome occurs in females [44,56–58]. Thus, normalizing allele phased reads causes a paternal bias to emerge for autosomal genes because of relatively more maternally-phased mitochondrial and X-linked reads. The solution is to normalize before phasing reads. Studies reporting more PEGs than MEGs also had relatively reduced power to detect noncanonical imprinting effects [45,46]. For instance, we analyzed ~90 mice per brain region or tissue [44], while others analyzed 18 or fewer [45,48], and/or used thresholding criteria for stronger imprinting effects (eg. a minimum 70% allele bias) [46]. Thus, straightforward differences in statistical power and thresholding criteria are likely factors shaping differences in the detection of noncanonical imprinting and the relative numbers of MEGs verusus PEGs in different studies.

It is unclear which studies, if any, capture the full breadth of the imprinted transcriptome. The most recent RNASeq studies of imprinting have a strong statistical framework and extensive independent validation that indicates that Type I errors are well managed [44–46,48,59]. However, less attention has been paid to Type II statistical errors. In mice, a simple internal control we find useful is the detection rate of the maternal allele expression bias for X-linked genes in female mice [44,56–58]. At a 1% false discovery rate (FDR), our approach detects the maternal effect for ~35% of expressed X-linked genes [44]. While our study had more power to detect imprinting than some others, and found ~200 autosomal imprinted genes in the mouse, we nonetheless estimate our Type II error rate at ~65% based on X-linked genes in females (Fig. 1E). Therefore, undiscovered autosomal imprinting effects may exist, and future screens should provide some internal metric of Type II errors to rigorously interpret the data and facilitate comparisons between studies (Fig. 1E).

Finally, there is a longstanding interest in determining how genomic imprinting may change in response to environmental and physiological factors. Pregnancy was recently shown to have relatively little effect on imprinting in maternal tissues [46]. Experience dependent plasticity in the visual cortex may change imprinting for some genes in the mouse brain [60], though much of the analysis was done with only 1 or 2 biological replicates, and more investigations may be warranted. A recent study developed a luciferase transgenic reporter strategy in mice to monitor diet and drug effects on imprinting in offspring. The data show that a maternal protein-deficient diet causes loss-of-imprinting in a developmental stage and tissue dependent manner for the maternally expressed imprinted gene, Cdkn1c [61]. This method is a powerful new platform to learn how environmental factors may perturb imprinting in offspring. In general, imprinting appears more malleable early in life, but seems relatively robust in adulthood [61–63].

Clonal and Dynamic Random Allelic Expression Effects in Brain Cells

Beyond genomic imprinting, other forms of allele-specific gene expression have been uncovered that manifest as random monoallelic expression. These phenomena have similarities and differences to random X-inactivation in females, which involves stochastic silencing of one X chromosome during early stages of embryonic development (for a comprehensive review, see [64]). Once a precursor cell chooses to express either the maternal (Xm) or paternal (Xp) X chromosome, subsequent daughter cells inherit that choice. Thus, random X-inactivation patterns are clonal in females. Although the intuition of random X-inactivation is that 50% of cells choose the Xp and 50% choose the Xm, that is frequently not the case. A study that generated transgenic mice in which the Xm was tagged with a green fluorescent protein reporter and the Xp was tagged with a tdTomato reporter [65] showed how clonal random monoallelic effects create variable cellular mosaics in vivo. Even within a litter, some siblings predominantly express the Xp, others predominantly express the Xm and some are a relatively equal mix. Within an individual, one brain hemisphere can be dominated by Xp expressing cells and the other by Xm expressing cells – a finding with important consequences for brain genetics.

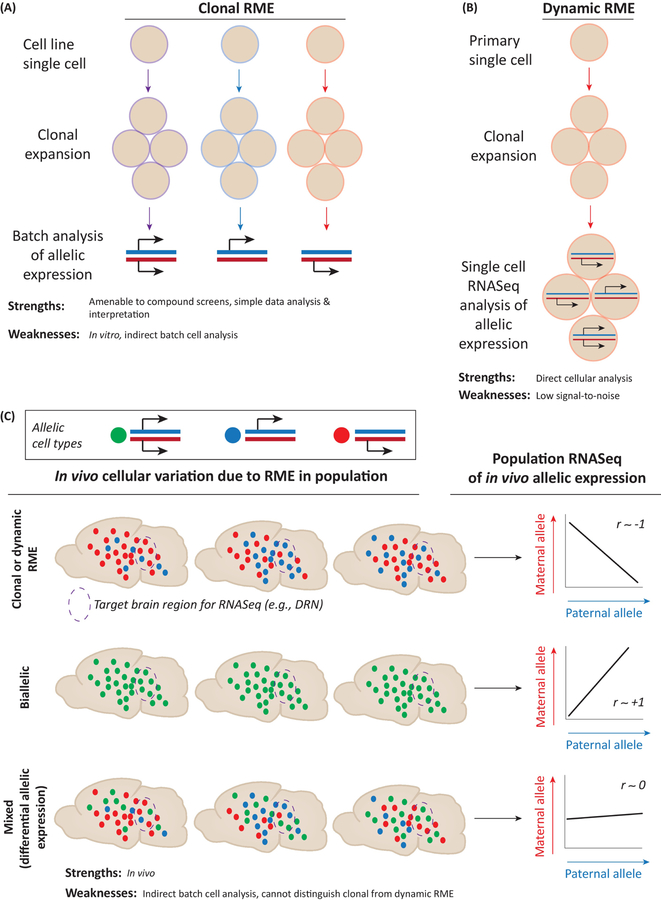

Several brain disorders are caused by X-linked mutations, such as MECP2, which is linked to Rett Syndrome [3]. However, the severity of the disorder in females can be influenced by the number and type of cells that chose the X chromosome harboring the mutant allele, due to skewed X-inactivation patterns [66–68]. Given these findings, there is interest in determining whether clonal random monoallelic effects impact some autosomal genes. A foundational study of human lymphoblastoid cell lines estimated that 5–10% of human autosomal genes exhibit clonal random monoallelic expression [69] (Fig. 2A). Similar results were later found in mouse lymphoblastoid cell lines [70], mouse embryonic stem cell (ESC) lines [71,72] and human neural progenitor cell lines [73,74]. Genes with these clonal random monoallelic effects have a distinguishing chromatin signature, which permitted the identification of in vivo candidates [75]. These putative clonal random monoallelic genes have increased genetic diversity in humans compared to other genes [76].

Figure 2. Different approaches detect random monoallelic expression (RME) in vitro and in vivo.

(A) Schematic depiction of clonal RME in cell lines. Single cells were expanded and allele-specific gene expression was analyzed in each clone by RNASeq or microarray. Biallelic, maternal monoallelic and paternal monoallelic clones were observed for many genes and the allelic expression pattern is the same in subsequent daughter cells derived from the same clone, indicating mitotic inheritance of allelic states. See [69, 70, 71, 72].

(B) Schematic depiction of dynamic RME in primary cell culture. Dynamic RME was identified using single cell RNASeq analysis of a clonal population of cells grown from a single cell in primary cell culture. Cells within a clone were observed to be heterogeneous in terms of allelic expression. Cells exhibited biallelic, maternal monoallelic or paternal monoallelic expression for many genes. See [79, 80].

(C) Schematic depicting the detection of clonal and dynamic RME in vivo in a brain region of interest using RNASeq. Genes with RME have maternal and paternal alleles with negatively correlated expression levels across a population of individuals because of variation at the cellular level: when more cells choose the maternal allele, fewer choose the paternal allele and vice versa. Across a population of individuals this variation gives rise to a negative correlation between the alleles in RNASeq data, which is clearly observed for random monoallelic X-linked genes in females. In contrast, biallelic expression, in which the maternal and paternal alleles are expressed in unison in the same cells, manifests as a positive correlation between the maternal and paternal alleles in RNASeq data from many individuals. Finally, when brain cells are a mosaic mix of biallelic and RME cell populations for a given gene, one observes a relatively low or absence of correlation in the expression of the maternal and paternal alleles. Imprinted genes are filtered and statistical modeling accounts for expression level, variance and genetic effects in the data, thereby yielding high confidence in vivo detection of RME. See [55].

The prevalence of clonal random monoallelic expression increases following differentiation into neural progenitors [71,72]. The mechanisms that preserve epigenetic information transfer between parent and daughter ESCs differ compared to dividing somatic cells [77], suggesting an area for study to understand what contributes to the differences in allelic expression effects in ESCs versus neural progenitors. A study using ATAC-Seq to investigate monoallelic patterns of DNA accessibility in mouse ESCs and neural progenitors recently found that random monoallelic open chromatin sites are more prevalent in neural progenitors than ESCs and are enriched at promoters [78]. Bivalent histone modifications in ESCs marked some sites that became random monoallelic in neural progenitors, and the monoallelic effect was observed to be mitotically inherited [78]. Clonal random monoallelic expression in neural progenitors does not appear to be related to gene dosage or require DNA methylation [71,72].

While the evidence for clonal random monoallelic expression in cell lines is well supported, the prevalence of this phenomenon in vivo is debated [8,79,80]. It has been argued that copy number variation, chromosomal instability and detection criteria in cell line studies contribute to overestimates of clonal random monoallelic genes [8]. A recent study using single cell RNASeq in primary somatic cells found that clonal random monoallelic expression is rare (<1% of genes), but a different form of random monoallelic expression, called dynamic random monoallelic expression, is more frequent (4–33% of genes depending on cell type) [79,80] (Fig. 2B). The authors interpret dynamic random monoallelic expression as being dynamic over time, but this was not directly shown. Instead, the data show that primary cells within a clone express different alleles, showing the effect is not clonal (Fig. 2B). Time-lapse imaging studies are needed to understand the temporal stability of different allelic states within a cell. Dynamic random monoallelic expression is related to gene expression levels and considered a function of the probabilistic nature of gene expression [8,79,81]. It is proposed to have roles in shaping developmental fate choices and cellular phenotypic variance [8]. Current estimates of the prevalence of dynamic random allelic expression effects in vivo may also be immature, partly in view of the lack of validation using an orthogonal approach in most of these studies. As dynamic allelic effects are more prevalent for lowly expressed genes, they are inherently difficult to detect and distinguish from the ~80% of random monoallelic expression in single cell RNASeq data due to technical noise [82]. Split-cell controls were used to carefully manage false positives [79,80]. Less is known about false negatives (Type II errors).

In an effort to screen for allele-specific expression effects in vivo, we recently devised and applied a genomics strategy for detecting allelic effects in bulk RNASeq data, which has reduced technical noise compared to single cell RNASeq [55] (Fig. 2C). Our approach takes advantage of the fact that random monoallelic expression across a population of individuals manifests as a distinctive pattern wherein expression of the maternal allele comes at the expense of expression of the paternal allele, and vice versa, such that the two are negatively correlated (Fig. 2B). This pattern is clearly detectable for X-linked genes in females. On the other hand, if the two alleles are expressed equally, then their expression will be highly correlated across individuals (Fig. 2B). Intermediate cases, in which some cells express a gene in a random monoallelic pattern and other cells express it in a biallelic manner, will potentially manifest as low maternal and paternal allele correlation (Fig. 2B). Empirical Bayesian modeling is performed to account for gene differences in expression level, variance and genetic effects to estimate the 95% confidence interval for the ground truth biological correlation between the two alleles. We used this approach to screen for novel autosomal genes that differentially express their maternal and paternal alleles in vivo in the mouse and primate brain.

Our findings show that random monoallelic expression from the autosomes is prevalent in vivo in the mouse and primate brain [55], supporting the general conclusions drawn from pioneering cell line studies. We independently validated our results with four different approaches, including an analysis of independently generated RNASeq datasets, pyrosequencing of RNA from new tissue samples, nascent RNA in situ hybridization to detect cellular allelic expression in tissue sections, and by examining heterozygous knockout reporter mice in which one allele expresses a lacZ reporter and the other expresses the wild-type allele. We found that heterozygous mutations in genes with differential allelic expression can form mosaics of brain cells that differentially express the mutant versus wild-type alleles.

It remains unclear whether the random monoallelic effects we observed in vivo are clonal or dynamic in nature, and the temporal stability of different allelic states in single brain cells remains untested. Different modes of epigenetic regulation were recently shown to have different temporal effects on gene silencing and activation at the cellular level [83], though little is known at the allele level. A consistent finding between our in vivo study [55] and previous in vitro studies [71,72,78] is that allelic expression states are developmentally regulated for many genes and differ between cell types [55,71,72,78,84]. We found that differential allelic expression is prevalent in the early postnatal mouse brain, impacting ~85% of genes, but impacts only ~10% of genes by weaning and in adulthood [55]. Thus, monoallelic and biallelic expression states change developmentally for many genes in neural lineages. The function, mechanisms involved and impacts on protein levels remain to be uncovered.

A Third Component of Phenotypic Variation?

The landscape of epigenetic allelic effects made possible by diploidy could contribute to the mysterious “third component” of phenotypic variation, which is independent of genetic and environmental factors [85]. Third component variation is estimated to cause 70–90% of non-genetic phenotypic variation in mammals, was uncovered during decades long efforts to use inbreeding to reduce phenotypic variation in lab animals and cattle [85], and is further supported by twin studies and studies of cloned animals [86–89]. It has been proposed that stochastic epigenetic effects, skewed random X-inactivation, polymorphic imprinting between individuals and unknown early embryonic factors contribute to third component phenotypic variation [86–89]. Most brain disorders are highly phenotypically variable and genetic factors often explain 50% or less of the phenotypic variation [16,87,90], suggesting an important contribution from third component variation. Further, similar genetic risk factors are shared across different disorders [91]. If allele-specific epigenetic effects underlie a substantial fraction of third component variation in brain phenotypes, the field may be able to get a foothold on important new mechanisms shaping psychiatric disorders and disease.

Understanding the function and mechanisms involved in different allelic effects in different brain cell populations is an important area for study. Genomic imprinting has only been observed in mammals and is postulated to have evolved for at least some genes due to an evolutionary conflict between mothers and fathers over the phenotypic traits of offspring [92]. The model predicts that maternally expressed imprinted genes function antagonistically to paternally expressed genes in offspring. Interestingly, a recent comprehensive study of imprinting found that imprinting is more prevalent during embryonic development [46,48], and relatively high numbers of imprinted genes were found in tissues important for energy transfer from mother to offspring [46]. In other work, evidence for genetic conflicts in imprinted gene networks was found from co-expressed pairs of MEGs and PEGs in offspring [48]. Noncanonical imprinting (and cell-type specific imprinting) in the brain may be a consequence of this conflict, such that MEGs and PEGs shape offspring brain and behavioral phenotypes in an antagonistic manner. This is an attractive model, as noncanonical imprinting has phenotypic consequences for offspring and can impact multiple genes in a pathway [44,45]. However, we know little about the relative functions of maternally and paternally expressed noncanonical (or canonical) imprinted genes in the brain or the consequences of disrupting imprinting at these loci (for a recent comprehensive review see [7]), and other explanations for imprinting have been proposed [93].

Stochastic gene expression and epigenetic effects are proposed to have important roles in developmental and phenotypic plasticity [88,94]. Indeed, a single cell analysis of early gastrulation in mice found that transcriptional noise increases prior to lineage commitment when cells transition between states [95]. We, and others, expect that autosomal random monoallelic expression on the autosomes plays important roles in cellular plasticity, state transitions and phenotypic variance [8,9]. In the context of genetic variation, random monoallelic expression of heterozygous variants could shape phenotypes in a manner similar to skewed X-inactivation, such that the genetic architecture of mosaics of cells differentially expressing mutant versus healthy alleles shapes phenotypic outcomes [66–68]. Intriguingly, we found that autosomal random allelic effects in the mouse brain cause these types of cellular mosaics for some genes [55].

Independent of interactions with genetic variation, random allelic effects could potentially impact gene dosage, such that cells with biallelic expression have a higher level of expression than cells with monoallelic expression. For clonal random monoallelic effects detected in neural progenitor lines, a significant effect on gene dosage was not detected [71,72]. However, dynamic random monoallelic effects are related to gene dosage [79]. In vivo, we observed a subset of genes with unusually highly correlated allele expression and these genes have significantly higher expression than most other genes in the genome, at least at the level of RNA [55]. Thus, mechanisms regulating coordinated allelic expression could influence gene dosage in some cases. Additionally, clonal and/or dynamic random allelic expression could resolve regulatory conflicts in the genome that might prevent two transcripts from being simultaneously co-expressed in a cell, similar to the case of UBE3A/Ube3a and UBE3A-ATS/Ube3a-ats detailed above, but in a random fashion. Indeed, overlapping sense-antisense gene pairs are common in the genome [96]. Also, ~50% of enhancers are intragenic, yet often regulate the activity of genes other than the host gene [97–99], potentially inhibiting the simultaneous expression of the two genes from the same allele. Finally, competitions between genes for access to the same enhancer(s) could create regulatory conflicts that are resolved in a random allelic manner. Such effects have been observed for olfactory receptors [6] and imprinted genes [100]. By resolving regulatory conflicts in an allele-specific manner, cells could create a condition of “allelic multiplexing” that detects and responds to a greater diversity of environmental cues.

Concluding Remarks

Diploidy and polyploidy are thought to be favored over haploidy for increasing genetic diversity [10]. Based on the studies detailed above, we propose that diploid and polyploidy states are also advantageous for increasing epigenetic diversity and the capacity to activate different gene expression programs in an allele and cell specific manner. The prevalence of imprinting and random monoallelic expression has been debated, but the recent studies and different approaches highlighted above now show that noncanonical imprinting and widespread autosomal random monoallelic expression are bona fide biological phenomena. The foundations have been laid for new efforts to focus on functional and mechanistic questions. Since multiple studies suggest that genes linked to neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders can exhibit random allelic expression in human brain cells [55,71–73,101], studies focused on the function and phenotypic significance may uncover novel mechanisms shaping disease risks. Overall, continued work in understanding gene regulation at the allele and cellular level has the potential to advance our understanding of the benefits of diploidy (and polyploidy) and define novel factors shaping brain cell development, function, plasticity and disease (see Outstanding Questions).

Outstanding Questions Box.

Noncanonical imprinting effects manifest as maternal or paternal allele expression biases at the level of brain regions. Are these tissue level allele biases caused by highly cell-type specific imprinting effects in a subset of cells in the brain?

How do canonical and noncanonical MEGs versus PEGs shape offspring brain functions and behaviors?

Which genes exhibit clonal random monoallelic expression, and which ones exhibit dynamic random monoallelic expression in vivo in the brain?

What is the function of random monoallelic and biallelic expression states in brain cells during development? Adulthood? Do they shape cellular plasticity and responses to environmental cues?

How do clonal and/or dynamic random monoallelic expression effects interact with heterozygous genetic mutations to shape phenotypes and risks for brain disorders?

How stable are different allelic expression states over time in a cell? Do they manifest at the protein level?

How do environmental factors and life experiences shape allelic expression states and brain cell functions? What are the mechanisms involved?

Does random monoallelic expression resolve regulatory conflicts between genes in the genome that arise due to sense-antisense overlapping transcripts, enhancer competitions or chromatin conformational incompatibilities? Does this phenomenon permit “allelic multiplexing” and expand the landscape of gene expression programs available to a brain cell, thereby promoting plasticity? Does biallelic expression reduce plasticity compared to allele-specific expression?

Does polyploidy in projection neurons and aging neurons help promote stress resilience and plasticity by expanding the landscape of different epigenetic and gene expression programs available?

Are the metabolic demands associated with biochemically regulating more alleles an important factor limiting ploidy across different cell types and species?

Highlights.

Recent studies show that allele-specific expression and epigenetic states are more prevalent at the cellular level in brain cells than generally thought. The expanded landscape of allelic effects involves imprinting and random monoallelic expression for autosomal genes.

Allelic effects may change our understanding of the benefits of diploidy. It is proposed that increased ploidy is beneficial for increasing epigenetic diversity and expanding a cell’s capacity to activate different gene expression programs, thereby improving responses to stress and to unpredictable environmental cues.

Monoallelic and biallelic expression states in brain cells are regulated in a developmental stage and cell-type dependent manner.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Elliott Ferris for feedback on the manuscript. We thank the students, postdocs and technical staff who made this review possible. Work in our lab is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH R01MH109577).

Glossary

- Allele

One of two or more alternative forms of a gene

- Angelman syndrome

A neurodevelopmental and autism spectrum disorder involving delayed development, intellectual disability, speech impairment, and problems with movement and balance (ataxia).

- Autosomal genes

Genes found on chromosomes that are not sex chromosomes (X or Y)

- Autosome

A chromosome that is not a sex chromosomes (X or Y)

- Biallelic cell

A cell that expresses the maternal and paternal allele for a gene.

- Diploidy

Ploidy refers the number of sets of chromosomes, and diploidy indicates two sets of chromosomes, such that each autosomal gene has two alleles.

- Genomic imprinting

A heritable epigenetic mechanism that causes preferential expression of either the maternally or paternally inherited allele for some genes in offspring.

- Haploidy

A form of ploidy involving only a single set of chromosomes.

- Haploinsufficiency

A term that describes when a diploid organism has only one functional copy (allele) of a gene and lost the function of the other allele due to a mutation.

- Hepatocytes

A type of liver cell. Hepatocytes make up ~80% of liver mass and carry out most of the major metabolic, protein synthesis and detoxification functions of the liver.

- Heterosis

Also called hybrid vigour. It is the phenomenon in which hybrid offspring from crosses of distantly related parental strains have superior biological trait(s) compared to the parents.

- Imprinting control region

A genetic element that is methylated on one parental allele, but not the other, and functions to regulate the imprinted expression of neighboring genes.

- Lymphoblastoid cell

Peripheral blood lymphocytes are transformed into lymphoblastoid cells that can be expanded as immortalized cell lines. Transformation is typically done by infecting peripheral blood lymphocytes with Epstein-Barr virus.

- Megakaryocytes

Large bone marrow cells responsible for the generation of platelets.

- Monoallelic cell

A diploid or polyploid cell that expresses only a single allele.

- Mosaic imprinting

Variable genomic imprinting in which some cells exhibit imprinted methylation at an imprinting control region and others do not.

- Noncanonical imprinting

A subtype of genomic imprinting that manifests as a bias to express one parental allele at a higher level than the other allele at the tissue level. In contrast, canonical imprinting involves complete tissue-level silencing of the imprinted allele.

- Polyploidy

Refers to organisms or cells with more than two sets of chromosomes.

- Tetraploidy

Refers to organisms or cells with four sets of chromosomes.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bartolomei MS and Ferguson-Smith AC (2011) Mammalian Genomic Imprinting. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 3, a002592–a002592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee JT (2011) Gracefully ageing at 50, X-chromosome inactivation becomes a paradigm for RNA and chromatin control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 12, 815–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deng X et al. (2014) X chromosome regulation: diverse patterns in development, tissues and disease. Nat Rev Genet DOI: 10.1038/nrg3687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vettermann C and Schlissel MS (2010) Allelic exclusion of immunoglobulin genes: models and mechanisms. Immunological Reviews 237, 22–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen WV and Maniatis T (2013) Clustered protocadherins. Development 140, 3297–3302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monahan K and Lomvardas S (2015) Monoallelic expression of olfactory receptors. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol 31, 721–740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perez JD et al. (2016) New Perspectives on Genomic Imprinting, an Essential and Multifaceted Mode of Epigenetic Control in the Developing and Adult Brain. Annu Rev Neurosci 39, annurev–neuro–061010–113708–384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reinius B and Sandberg R (2015) Random monoallelic expression of autosomal genes: stochastic transcription and allele-level regulation. Nat Rev Genet 16, 653–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chess A (2016) Monoallelic Gene Expression in Mammals. Annu Rev Genet 50, 317–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Otto SP and Gerstein AC (2008) The evolution of haploidy and diploidy. Current Biology 18, R1121–R1124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White JK et al. (2013) Genome-wide Generation and Systematic Phenotyping of Knockout Mice Reveals New Roles for Many Genes. Cell 154, 452–464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang N et al. (2010) Characterising and predicting haploinsufficiency in the human genome. PLoS Genet 6, e1001154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shihab HA et al. (2017) HIPred: an integrative approach to predicting haploinsufficient genes. Bioinformatics 33, 1751–1757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yi F et al. (2016) Autism-associated SHANK3 haploinsufficiency causes Ih channelopathy in human neurons. Science 352, aaf2669–aaf2669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gompers AL et al. (2017) Germline Chd8 haploinsufficiency alters brain development in mouse. Nat Neurosci 20, 1062–1073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaste P et al. (2017) The Yin and Yang of Autism Genetics: How Rare De Novo and Common Variations Affect Liability. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 18, 167–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duffney LJ et al. (2015) Autism-like Deficits in Shank3-Deficient Mice Are Rescued by Targeting Actin Regulators. CellReports 11, 1400–1413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsiao T-L and Vitkup D (2008) Role of duplicate genes in robustness against deleterious human mutations. PLoS Genet 4, e1000014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Payne JL and Wagner A (2015) Mechanisms of mutational robustness in transcriptional regulation. Front Genet 6, 322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sagi I and Benvenisty N (2017) Haploidy in Humans: An Evolutionary and Developmental Perspective. Dev Cell 41, 581–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Birchler JA et al. (2010) Heterosis. Plant Cell 22, 2105–2112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Comings DE and MacMurray JP (2000) Molecular heterosis: a review. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism 71, 19–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen ZJ (2013) Genomic and epigenetic insights into the molecular bases of heterosis. Nat Rev Genet 14, 471–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van de Peer Y et al. (2017) The evolutionary significance of polyploidy. Nat Rev Genet 18, 411–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gentric G and Desdouets C (2014) Polyploidization in Liver Tissue. Am J Pathol 184, 322–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lentz RD and Lapham LW (1970) Postnatal development of tetraploid DNA content in rat purkinje cells: a quantitative cytochemical study. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol 29, 43–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swartz FJ and Bhatnagar KP (1981) Are CNS neurons polyploid? A critical analysis based upon cytophotometric study of the DNA content of cerebellar and olfactory bulbar neurons of the bat. Brain Res 208, 267–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sigl-Glöckner J and Brecht M (2017) Polyploidy and the Cellular and Areal Diversity of Rat Cortical Layer 5 Pyramidal Neurons. CellReports 20, 2575–2583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lopez-Sanchez N and Frade JM (2013) Genetic Evidence for p75NTR-Dependent Tetraploidy in Cortical Projection Neurons from Adult Mice. Journal of Neuroscience 33, 7488–7500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mosch B et al. (2007) Aneuploidy and DNA replication in the normal human brain and Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci 27, 6859–6867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Westra JW et al. (2010) Neuronal DNA content variation (DCV) with regional and individual differences in the human brain. J. Comp. Neurol 518, 3981–4000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fischer H-G et al. (2012) Changes in neuronal DNA content variation in the human brain during aging. Aging Cell 11, 628–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bushman DM and Chun J (2013) The genomically mosaic brain: aneuploidy and more in neural diversity and disease. Semin Cell Dev Biol 24, 357–369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Madlung A (2012) Polyploidy and its effect on evolutionary success: old questions revisited with new tools. Heredity 110, 99–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frade JM and López-Sánchez N (2017) Neuronal tetraploidy in Alzheimer and aging. Aging DOI: 10.18632/aging.101312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.LaSalle JM et al. (2015) Epigenetic regulation of UBE3A and roles in human neurodevelopmental disorders. Epigenomics 7, 1213–1228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sato M and Stryker MP (2010) Genomic imprinting of experience-dependent cortical plasticity by the ubiquitin ligase gene Ube3a. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107, 5611–5616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Judson MC et al. (2014) Allelic specificity of Ube3a Expression In The Mouse Brain During Postnatal Development 522, 1874–1896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jones KA et al. (2016) Persistent neuronal Ube3a expression in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of Angelman syndrome model mice. Sci Rep 6, 28238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ehlen JC et al. (2015) Maternal Ube3a Loss Disrupts Sleep Homeostasis But Leaves Circadian Rhythmicity Largely Intact. J Neurosci 35, 13587–13598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang H-S et al. (2011) Topoisomerase inhibitors unsilence the dormant allele of Ube3a in neurons. Nature 481, 185–189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Silva-Santos S et al. (2015) Ube3a reinstatement identifies distinct developmental windows in a murine Angelman syndrome model. J Clin Invest 125, 2069–2076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meng L et al. (2015) Towards a therapy for Angelman syndrome by targeting a long noncoding RNA. Nature 518, 409–412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bonthuis PJ et al. (2015) Noncanonical Genomic Imprinting Effects in Offspring. CellReports 12, 979–991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perez JD et al. (2015) Quantitative and functional interrogation of parent-of-origin allelic expression biases in the brain. eLife 4, e07860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andergassen D et al. (2017) Mapping the mouse Allelome reveals tissue-specific regulation of allelic expression. eLife 6, e146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crowley JJ et al. (2015) Analyses of allele-specific gene expression in highly divergent mouse crosses identifies pervasive allelic imbalance. Nat Genet 47, 353–360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Babak T et al. (2015) Genetic conflict reflected in tissue-specific maps of genomic imprinting in human and mouse. Nat Genet 47, 544–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baran Y et al. (2015) The landscape of genomic imprinting across diverse adult human tissues. Genome Res 25, 927–936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stelzer Y et al. (2016) Parent-of-Origin DNA Methylation Dynamics during Mouse Development. CellReports 16, 3167–3180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stelzer Y et al. (2015) Tracing Dynamic Changes of DNA Methylation at Single-Cell Resolution. Cell 163, 218–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ferrón SR et al. (2011) Postnatal loss of Dlk1 imprinting in stem cells and niche astrocytes regulates neurogenesis. Nature 475, 381–385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stelzer Y et al. (2015) Differentiation of Human Parthenogenetic Pluripotent Stem Cells Reveals Multiple Tissue- and Isoform-Specific Imprinted Transcripts. CellReports 11, 308–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Allen ND et al. (1995) Distribution of parthenogenetic cells in the mouse brain and their influence on brain development and behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92, 10782–10786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang W-C et al. (2017) Diverse Non-genetic, Allele-Specific Expression Effects Shape Genetic Architecture at the Cellular Level in the Mammalian Brain. Neuron 93, 1094–1109.e7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gregg C et al. (2010) Sex-specific parent-of-origin allelic expression in the mouse brain. Science 329, 682–685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang X et al. (2010) Paternally biased X inactivation in mouse neonatal brain. Genome Biol 11, R79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Calaway JD et al. (2013) Genetic Architecture of Skewed X Inactivation in the Laboratory Mouse. PLoS Genet 9, e1003853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Deveale B et al. (2012) Critical evaluation of imprinted gene expression by RNA–Seq: a new perspective. PLoS Genet DOI: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002600.g006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hsu C-L et al. (2018) Analysis of experience-regulated transcriptome and imprintome during critical periods of mouse visual system development reveals spatiotemporal dynamics. Hum Mol Genet 27, 1039–1054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Van de Pette M et al. (2017) Visualizing Changes in Cdkn1c Expression Links Early-Life Adversity to Imprint Mis-regulation in Adults. CellReports 18, 1090–1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vidal AC et al. (2014) Maternal stress, preterm birth, and DNA methylation at imprint regulatory sequences in humans. GEG 6, 37–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vangeel EB et al. (2015) DNA methylation in imprinted genes IGF2 and GNASXL is associated with prenatal maternal stress. Genes Brain Behav 14, 573–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Disteche CM (2012) Dosage Compensation of the Sex Chromosomes. Annu Rev Genet 46, 537–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wu H et al. (2014) Cellular resolution maps of X chromosome inactivation: implications for neural development, function, and disease. Neuron 81, 103–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Knudsen GPS et al. (2006) Increased skewing of X chromosome inactivation in Rett syndrome patients and their mothers. Eur J Hum Genet 14, 1189–1194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Huppke P et al. (2006) Very mild cases of Rett syndrome with skewed X inactivation. J Med Genet 43, 814–816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Young JI and Zoghbi HY (2004) X-chromosome inactivation patterns are unbalanced and affect the phenotypic outcome in a mouse model of rett syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 74, 511–520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gimelbrant A et al. (2007) Widespread monoallelic expression on human autosomes. Science 318, 1136–1140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zwemer LM et al. (2012) Autosomal monoallelic expression in the mouse. Genome Biol 13, R10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Eckersley-Maslin MA et al. (2014) Random monoallelic gene expression increases upon embryonic stem cell differentiation. Dev Cell 28, 351–365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gendrel A-V et al. (2014) Developmental dynamics and disease potential of random monoallelic gene expression. Dev Cell 28, 366–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jeffries AR et al. (2013) Random or Stochastic Monoallelic Expressed Genes Are Enriched for Neurodevelopmental Disorder Candidate Genes. PLoS ONE 8, e85093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jeffries AR et al. (2012) Stochastic Choice of Allelic Expression in Human Neural Stem Cells. Stem Cells 30, 1938–1947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nag A et al. (2013) Chromatin signature of widespread monoallelic expression. eLife 2, e01256–e01256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Savova V et al. (2016) Genes with monoallelic expression contribute disproportionately to genetic diversity in humans. Nat Genet 48, 231–237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shipony Z et al. (2014) Dynamic and static maintenance of epigenetic memory in pluripotent and somatic cells. Nature 513, 115–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Xu J et al. (2017) Landscape of monoallelic DNA accessibility in mouse embryonic stem cells and neural progenitor cells. Nat Genet 49, 377–386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Reinius B et al. (2016) Analysis of allelic expression patterns in clonal somatic cells by single-cell RNA–seq. Nat Genet 48, 1430–1435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Deng Q et al. (2014) Single-Cell RNA-Seq Reveals Dynamic, Random Monoallelic Gene Expression in Mammalian Cells. Science 343, 193–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Deng Q et al. (2014) Single-cell RNA-seq reveals dynamic, random monoallelic gene expression in mammalian cells. Science 343, 193–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kim JK et al. (2015) Characterizing noise structure in single-cell RNA-seq distinguishes genuine from technical stochastic allelic expression. Nat Commun 6, 8687–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hansen SG et al. (2016) Dynamics of epigenetic regulation at the single-cell level. Science 351, 720–724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Reinius B et al. (2016) Analysis of allelic expression patterns in clonal somatic cells by single-cell RNA-seq. Nat Genet 48, 1430–1435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gärtner K (1990) A third component causing random variability beside environment and genotype. A reason for the limited success of a 30 year long effort to standardize laboratory animals? Laboratory Animals 24, 71–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gartner K (2012) Commentary: Random variability of quantitative characteristics, an intangible epigenomic product, supporting adaptation. Int J Epidemiol 41, 342–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wong AHC et al. (2005) Phenotypic differences in genetically identical organisms: the epigenetic perspective. Hum Mol Genet 14, R11–R18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pujadas E and Feinberg AP (2012) Regulated Noise in the Epigenetic Landscape of Development and Disease. Cell 148, 1123–1131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Feinberg AP and Irizarry RA (2010) Stochastic epigenetic variation as a driving force of development, evolutionary adaptation, and disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107, 1757–1764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Haque FN et al. (2009) Not really identical: epigenetic differences in monozygotic twins and implications for twin studies in psychiatry. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 151, 136–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Martin J et al. (2017) Assessing the evidence for shared genetic risks across psychiatric disorders and traits. Psychol Med 20, 1–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Haig D and Haig D (2004) Genomic Imprinting and Kinship: How Good is the Evidence? Annu Rev Genet 38, 553–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Spencer HG and Clark AG (2014) Non-conflict theories for the evolution of genomic imprinting. Heredity 113, 112–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Levine JH et al. (2013) Functional roles of pulsing in genetic circuits. Science 342, 1193–1200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mohammed H et al. (2017) Single-Cell Landscape of Transcriptional Heterogeneity and Cell Fate Decisions during Mouse Early Gastrulation. CellReports 20, 1215–1228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wood EJ et al. Sense-antisense gene pairs: sequence, transcription, and structure are not conserved between human and mouse. frontiersin.org DOI: 10.3389/fgene.2013.00183/abstract [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 97.Heintzman ND et al. (2007) Distinct and predictive chromatin signatures of transcriptional promoters and enhancers in the human genome. Nat Genet 39, 311–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Birnbaum RY et al. (2012) Coding exons function as tissue-specific enhancers of nearby genes. Genome Res 22, 1059–1068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Harmston N and Lenhard B (2013) Chromatin and epigenetic features of long-range gene regulation. Nucleic Acids Res 41, 7185–7199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kurukuti S et al. (2006) CTCF binding at the H19 imprinting control region mediates maternally inherited higher-order chromatin conformation to restrict enhancer access to Igf2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103, 10684–10689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Adegbola AA et al. (2015) Monoallelic expression of the human FOXP2speech gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112, 6848–6854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]