Abstract

Background/Objectives:

Reducing potentially preventable hospitalization (PPH) among older adults with dementia is a goal of Healthy People 2020, yet no tools specifically identify patients with dementia at highest risk. The objective was to develop a risk prediction model to identify older adults with dementia at high imminent risk of PPH.

Design:

A 30-day risk prediction model was developed using multivariable logistic regression. Patients from fiscal years (FY) 2009-2011 were split into development and validation cohorts; FY 2012 was used for prediction.

Setting:

Community-dwelling older adults (≥65) with dementia who received care through the Veterans Health Administration.

Participants:

n=1,793,783

Measurements:

Characteristics associated with hospitalization risk, including: 1) age, other demographic factors; 2) outpatient, emergency department, and inpatient utilization; 3) medical and psychiatric diagnoses; 4) prescribed medication use, including changes to psychotropic medications (e.g., initiation or dosage increase). Model discrimination was determined by c-statistic for each of the three cohorts. Finally, to determine whether predicted 30-day risk strata were stable over time, the observed PPH rate was calculated out to one year.

Results:

In the development cohort, 0.6% of patients experienced PPH within 30 days. The c-statistic for the development cohort was 0.83 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.83-0.84) and 0.83 in the prediction cohort (95% CI 0.82-0.84). Patients in the top 10% of predicted 30-day PPH risk accounted for over 50% of 30-day PPH admissions in all three cohorts. In addition, those predicted to be at elevated 30-day risk remained at higher risk throughout a year of follow-up.

Conclusion:

It is possible to identify older adults with dementia at high risk of imminent PPH, and their risk remains elevated for an entire year. Given the negative outcomes associated with acute hospitalization for those with dementia, healthcare systems and providers may be able to proactively engage these high-risk patients to avoid unnecessary hospitalization.

Keywords: dementia, potentially preventable hospitalization, risk prediction

INTRODUCTION

Patients with dementia have an all-cause hospitalization rate approximately 1.4-times higher than other older adults, while potentially preventable hospitalization (PPH) is nearly 1.8-times higher.1 PPH captures admission for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions—like congestive heart failure (CHF) or pneumonia—that, with optimal outpatient access and management, are potentially unnecessary. Reduction of PPH specifically in older adults with dementia is a goal of Healthy People 2020.2,3 Their elevated hospitalization risk is worrying because, while all older adults are at increased risk of hospitalization-associated delirium, iatrogenic complications, and cognitive and functional decline,4–6 the consequences are greater for patients with dementia,7,8 for whom cognitive or functional decline are risk factors for institutionalization.9,10

As the population with dementia nearly triples by 2050,11 even small reductions in the rate of PPH could have a large impact. Unfortunately, no controlled dementia care intervention trials have demonstrated a reduction in hospitalization.12,13 One possible reason is the trials were not specifically designed to target patients at highest risk of hospitalization. Given the potential adverse consequences of hospitalization for older adults with dementia, identifying those at high risk before they need to be hospitalized—especially admissions for conditions that could potentially be treated in an outpatient setting—is critical.

Approaches to risk-stratify patients with dementia that do not rely on over-burdened primary care clinicians14 is key to appropriately target supports that may benefit these older adults and their caregivers.15 For this analysis, we used national data from the U.S. Veterans Health Administration (VHA) electronic health record to develop a multivariable logistic regression model to predict PPH admission within 30 days (developmental cohort). We then used the model to identify risk tiers among a different cohort of older adults with dementia (validation cohort) and determine whether the model could accurately predict risk among the new set of patients (prediction cohort).

METHODS

Study sample and outcome

The study sample (n=1,793,783) was drawn from older adults treated in the VHA from October 1, 2008 through September 30, 2012 (fiscal years [FY] 2009–2012). The first index date was October 1, 2008 (i.e., the start of FY2009), with a cohort including patients who met the following 4 inclusion criteria: 1) ≥65 years of age; 2) at least one inpatient or outpatient encounter within the previous 12 months to establish use of VHA services; 3) dementia diagnosis prior to index date (based on ≥1 encounter with one of the following ICD-9-CM codes, as used in previous work16–18: 046.1, 046.3, 290.0, 290.1x, 290.2x, 290.3, 290.4x, 291.2, 294.10, 294.11, 331.0, 331.1, and 331.82); and 4) not in a VHA inpatient or long-term care setting on the index date.

Then, we expanded the cohort by moving the index date ahead at two-months intervals from December 1, 2008; February 1, 2009; and so on; through August 1, 2012. All patients who met the four inclusion criteria at the index date of each two-month interval (e.g., on December 1, 2008) were considered at-risk for potentially preventable hospitalization (PPH) and included in the cohort. Therefore, a single patient could contribute multiple at-risk intervals to the final cohort.

The event of interest was PPH admission within 30 days of entering the cohort (i.e., the index date). We defined PPH using the primary ICD-9-CM discharge diagnosis (Supplementary Table S1) for the inpatient admission, applying the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality prevention quality indicators,19 which include conditions both acute (e.g., dehydration, bacterial pneumonia, kidney or urinary tract infection) and chronic (diabetes, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, congestive heart failure exacerbation, angina). To be consistent with prior studies,1,3,20 we also included cellulitis, gastric/duodenal/peptic ulcer, ear/nose/throat infection, gastroenteritis, hypoglycemia, hypokalemia, influenza, malnutrition, and seizure disorder. The total cohort from the first three years (FY2009–2011) was randomly split into halves to develop and validate the prediction model (n=664,355 and 664,357, respectively); the final year (FY2012; n=465,071) was used as a prediction cohort to apply the model.

Measures

Candidate model variables were chosen based on prior work examining predictors of hospitalization in older adults.21–23 Demographic variables included age, gender, race (white, black, other race, unknown race), Hispanic ethnicity, marital status (married, single/never, divorced, widowed, unknown), and urbanicity (urban, rural, highly rural as defined by VHA using U.S. Census designations). Clinical characteristics included length of time since the first dementia diagnosis (a proxy for dementia severity, ascertained from records going back 10 years), number of unique prescription medications as of the index date, and presence of the following conditions based on clinical encounters in the preceding 12 months (Supplementary Table S1): diagnoses used to derive the Charlson Comorbidity Index; each PPH condition; delirium (or other transient mental status change); and individual psychiatric conditions including depression, bipolar disorder, and anxiety disorders.

Service utilization characteristics included the number of outpatient, inpatient, and emergency room visits for specific pre-index intervals: 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months.

Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia may be associated with hospitalization risk,24,25 and the use of psychotropic medications suggest these symptoms are present,26 so we used indicators of psychotropic (e.g., antipsychotic, antidepressant, sedative/hypnotic, mood stabilizer) and antidementia (e.g., cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine) medication prescribing: prevalent use; incident use; and dosage escalation. Each psychotropic indicator was determined for 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months pre-index, as well as on the index date.

Analysis

Our goal was to develop a model predicting 30-day PPH risk; we followed an analytic plan similar to one used to develop and validate a suicide risk prediction model among VHA patients using the VHA EHR.27 To develop a model to predict 30-day PPH, we used the development cohort and fit multivariable logistic regression. Generalized estimation equation with independence was used to adjust for potential correlation from repeated inclusion of the same patients.

Because the medication and service utilization measures were collected for several pre-specified time intervals that were potentially correlated (e.g., antipsychotic use 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months pre-index), we screened each set of measures separately to determine which were most predictive. Based on the magnitude and significance of the parameter estimates, 1 month pre-index was most predictive of PPH, so the final model only included medication and service utilization indicators from the month pre-index. Longer pre-index intervals (e.g., 3 or 6 months pre-index) did not further add to model predictiveness, with parameter estimates close to zero.

To allow for effect modification of diagnoses and utilization measures by patient age, we also considered variable-by-age interaction terms, but they were neither significant nor improved the model fit so were not retained. For continuous or count measures (age, number of outpatient visits, etc.), we included linear and square terms after centering the measures to allow non-linear relationships. We did not use any additional variable reduction approaches and retained all variables in the model regardless of statistical significance because our focus was on overall prediction of risk rather than causal inferences related to specific characteristics and the associated PPH risk.

We present the distribution of select patient sociodemographic and clinical characteristics in the development cohort overall and among those with a PPH admission within 30 days or one year. Patient characteristics are described for those at risk of PPH at all intervals; if a patient is at risk of PPH in more than one interval, that person’s contribution to the patient characteristics is considered as if from a different patent for each interval. Therefore, the values of the predictors corresponding to each time interval are all accounted for separately.

Model discrimination was assessed by calculating the c-statistic in each of the three cohorts: development (half 1 of FY2009–2011), validation (half 2 of FY2009–2011), and prediction (FY2012). In each study cohort, based on the ranked predicted probability of PPH admission within 30 days, we set risk cut-points starting with those patients with the top 0.1% predicted probability down through lower, more inclusive tiers of risk (e.g., top 0.5%, 1.0%, 5.0%, etc.). We examined risk concentration for each cut-point by determining the number of observed PPH admissions for patients in the risk tier divided by the number of expected PPH admissions based on the overall cohort PPH rate. We used the validation cohort to graphically display calibration by deciles of predicted risk and also used the Hosmer-Lemeshow test for goodness of fit.

To appreciate the impact of applying the model to a new set of patients, performance characteristics (sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value) were determined in the prediction cohort using the pre-specified risk cut-points.

Finally, to determine whether those at high imminent (i.e., 30-day) risk of PPH remained at high risk throughout an entire year, we applied the 30-day PPH risk cut-points to the prediction cohort to determine each tier’s risk concentration 1, 3, 6, and 12 months post-index. Statistical analyses were done using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Select demographic and clinical characteristics of the development cohort are presented in Table 1 (all characteristics in Supplementary Table S2), which included 664,355 adults with dementia. The 30-day PPH rate was 69.7 per 1,000 person-years, while 1-year PPH rate was 57.6 per 1,000 person-years. The PPH rate of black patients was nearly double that of white patients. Those patients that experienced PPH within 30 days had more use of each type of inpatient and outpatient service, as well as more of every category of psychotropic medication use, including dose increases in the pre-index month.

Table 1.

Select demographic and clinical characteristics and 30-day and 1-year rates of potentially preventable hospitalization (PPH) among the development cohort.

| Characteristica | N (%) | Patients with PPH within 30 days, N (%) | Patients with PPH within 1 year, N (%) | 30-day PPH rate per 1,000 person-yrb | 1-year PPH rate per 1,000 person-yrb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 664,355c | 3,745 | (0.6) | 31,962 | (4.8) | 69.7 | 57.6 | |

| Age, y | ||||||||

| 65–74 | 113,964 | (17.2) | 659 | (17.6) | 5,732 | (17.9) | 71.5 | 58.9 |

| 75–84 | 322,642 | (48.6) | 1,688 | (45.1) | 14,639 | (45.8) | 64.6 | 53.6 |

| ≥85 | 227,749 | (34.3) | 1,398 | (37.3) | 11,591 | (36.3) | 76.1 | 63.0 |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 647,274 | (97.4) | 3,646 | (97.4) | 31,088 | (97.3) | 69.7 | 57.6 |

| Race | ||||||||

| White | 482,594 | (72.6) | 2,743 | (73.2) | 23,214 | (72.6) | 70.3 | 57.5 |

| Black | 67,907 | (10.2) | 694 | (18.5) | 5,971 | (18.7) | 127.1 | 109.6 |

| Other races | 15,463 | (2.3) | 100 | (2.7) | 943 | (3.0) | 80.0 | 73.4 |

| Unknown or missing | 98,391 | (14.8) | 208 | (5.6) | 1,834 | (5.7) | 26.1 | 22.0 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | ||||||||

| Yes | 17,794 | (2.7) | 156 | (4.2) | 1,236 | (3.9) | 108.8 | 85.1 |

| No | 575,614 | (86.6) | 3,421 | (91.4) | 29,277 | (91.6) | 73.5 | 60.9 |

| Unknown or missing | 70,947 | (10.7) | 168 | (4.5) | 1,449 | (4.5) | 29.3 | 24.5 |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Married | 429,644 | (64.7) | 1,903 | (50.8) | 16,399 | (51.3) | 54.7 | 45.0 |

| Single/never married | 35,670 | (5.4) | 294 | (7.9) | 2,586 | (8.1) | 102.6 | 90.0 |

| Divorced | 79,610 | (12.0) | 651 | (17.4) | 5,440 | (17.0) | 101.5 | 84.0 |

| Widowed | 116,469 | (17.5) | 889 | (23.7) | 7,465 | (23.4) | 94.7 | 79.4 |

| Unknown or missing | 2,962 | (0.4) | 8 | (0.2) | 72 | (0.2) | 33.4 | 29.2 |

| Residence | ||||||||

| Urban | 432,406 | (65.1) | 2,670 | (71.3) | 22,558 | (70.6) | 76.4 | 62.9 |

| Rural | 224,684 | (33.8) | 1,048 | (28.0) | 9,159 | (28.7) | 57.6 | 48.2 |

| Highly rural | 7,265 | (1.1) | 27 | (0.7) | 245 | (0.8) | 45.9 | 39.8 |

| Diagnoses present in past 12 months | ||||||||

| Myocardial infarction | 20,181 | (3.0) | 337 | (9.0) | 2,182 | (6.8) | 210.0 | 144.1 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 125,495 | (18.9) | 1,256 | (33.5) | 10,227 | (32.0) | 124.7 | 102.9 |

| Delirium or other transient mental status change | 280,286 | (42.2) | 2,100 | (56.1) | 16,953 | (53.0) | 93.0 | 74.5 |

| Depression | 167,864 | (25.3) | 1,249 | (33.4) | 10,508 | (32.9) | 92.2 | 76.3 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 40,426 | (6.1) | 309 | (8.3) | 2,545 | (8.0) | 94.7 | 76.3 |

| Other anxiety disorders | 48,414 | (7.3) | 413 | (11.0) | 3,295 | (10.3) | 105.9 | 83.2 |

| Duration of dementia | ||||||||

| < 1 year | 165,081 | (24.8) | 1,035 | (27.6) | 7,811 | (24.4) | 77.7 | 56.8 |

| 1-3 years | 292,349 | (44.0) | 1,510 | (40.3) | 13,327 | (41.7) | 63.8 | 54.4 |

| 4-6 years | 141,122 | (21.2) | 709 | (18.9) | 6,645 | (20.8) | 62.1 | 56.3 |

| ≥ 7 years | 65,803 | (9.9) | 491 | (13.1) | 4,179 | (13.1) | 92.4 | 77.1 |

| Type of dementia | ||||||||

| Alzheimer’s disease | 545,775 | (82.2) | 2,794 | (74.6) | 24,050 | (75.2) | 63.3 | 52.6 |

| Vascular dementia | 175,687 | (26.4) | 1,429 | (38.2) | 12,212 | (38.2) | 101.0 | 85.8 |

| Lewy body dementia | 32,098 | (4.8) | 236 | (6.3) | 1,762 | (5.5) | 91.6 | 69.9 |

| Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy | 256 | (<0.1) | 2 | (0.1) | 11 | (<0.1) | 97.2 | 52.3 |

| Jakob-Creutzfeldt disease | 236 | (<0.1) | 3 | (0.1) | 21 | (0.1) | 157.9 | 109.4 |

| Alcoholic dementia | 20,558 | (3.1) | 167 | (4.5) | 1,419 | (4.4) | 101.0 | 85.4 |

| Pick’s dementia | 9,980 | (1.5) | 59 | (1.6) | 533 | (1.7) | 73.1 | 64.4 |

| Utilization in past month | ||||||||

| Medical/surgical outpatient visits, n | ||||||||

| 0 | 336,372 | (50.6) | 732 | (19.6) | 7,846 | (24.5) | 26.8 | 27.1 |

| 1 | 147,262 | (22.2) | 687 | (18.3) | 6,753 | (21.1) | 57.5 | 54.1 |

| 2 | 77,930 | (11.7) | 564 | (15.1) | 5,037 | (15.8) | 89.6 | 78.4 |

| ≥3 | 102,791 | (15.5) | 1,762 | (47.1) | 12,326 | (38.6) | 216.1 | 162.1 |

| Acute inpatient hospitalizations, n | ||||||||

| 0 | 655,674 | (98.7) | 3,314 | (88.5) | 29,992 | (93.8) | 62.4 | 54.5 |

| 1 | 8,313 | (1.3) | 396 | (10.6) | 1,851 | (5.8) | 640.5 | 403.9 |

| ≥2 | 368 | (0.1) | 35 | (0.9) | 119 | (0.4) | 1,412.7 | 824.0 |

| Medications on index date, n | ||||||||

| 0 | 139,929 | (21.1) | 517 | (13.8) | 4,178 | (13.1) | 45.9 | 36.8 |

| 1-2 | 93,255 | (14.0) | 265 | (7.1) | 2,675 | (8.4) | 35.0 | 33.4 |

| 3-4 | 114,498 | (17.2) | 348 | (9.3) | 3,678 | (11.5) | 37.4 | 37.1 |

| 5-6 | 109,603 | (16.5) | 537 | (14.3) | 4,548 | (14.2) | 60.4 | 48.4 |

| ≥7 | 207,070 | (31.2) | 2,078 | (55.5) | 16,883 | (52.8) | 124.6 | 100.6 |

| Class of psychotropic use on index date | ||||||||

| Antipsychotic | 64,358 | (9.7) | 530 | (14.2) | 4,378 | (13.7) | 102.4 | 86.0 |

| Antidepressant | 175,836 | (26.5) | 1,295 | (34.6) | 10,918 | (34.2) | 91.1 | 75.0 |

| Sedative/hypnotic | 49,248 | (7.4) | 369 | (9.9) | 3,172 | (9.9) | 92.8 | 78.6 |

| Mood stabilizer | 48,743 | (7.3) | 453 | (12.1) | 3,808 | (11.9) | 115.4 | 96.2 |

| Psychotropic dose increase in prior month | ||||||||

| Antipsychotic | 19,709 | (3.0) | 178 | (4.8) | 1,430 | (4.5) | 112.4 | 92.6 |

| Antidepressant | 51,758 | (7.8) | 411 | (11.0) | 3,439 | (10.8) | 98.4 | 80.7 |

| Sedative/hypnotic | 13,970 | (2.1) | 121 | (3.2) | 952 | (3.0) | 107.4 | 83.6 |

| Mood stabilizer | 13,526 | (2.0) | 137 | (3.7) | 1,108 | (3.5) | 125.8 | 101.6 |

For the complete list of characteristics included in the predictive model and model coefficients, see eTables 2 and 3, respectively.

Calculated as number of patients with PPH divided by the at-risk days where person-days are counted until the earliest date of PPH, non-PPH admission, death, or end of follow-up period (30 days for 30-day rate and 12 months for 12-month rate) and expressed as per 1,000 person-years. Participants who were at risk in multiple intervals are counted multiple times. In the development cohort, 16396 (13%) patients were included only once, 15042 (12%) patients twice,14049 (11.2%) patients 3 times, 12868 (10.2%) patients 4 times, 11567 (9.2%) patients 5 times, 10921 (8.7%) patients 6 times, 10714 (8,5%) 7 times, 10066 (8%) 8 times, 8921 (7.1%) patients 9 times, 6693 (5.3%) 10 times, 4434 (3.5%) 11 times, 2386 (1.9%) patients 12 times, 1092 (0.8%) patients 13 times, 358 (0.3%) patients 14 times, 84 (0.07%) patients 15 times, 14 (0.01%) patients 16 times, 2 patients 17 times, and 1 patient 18 times.

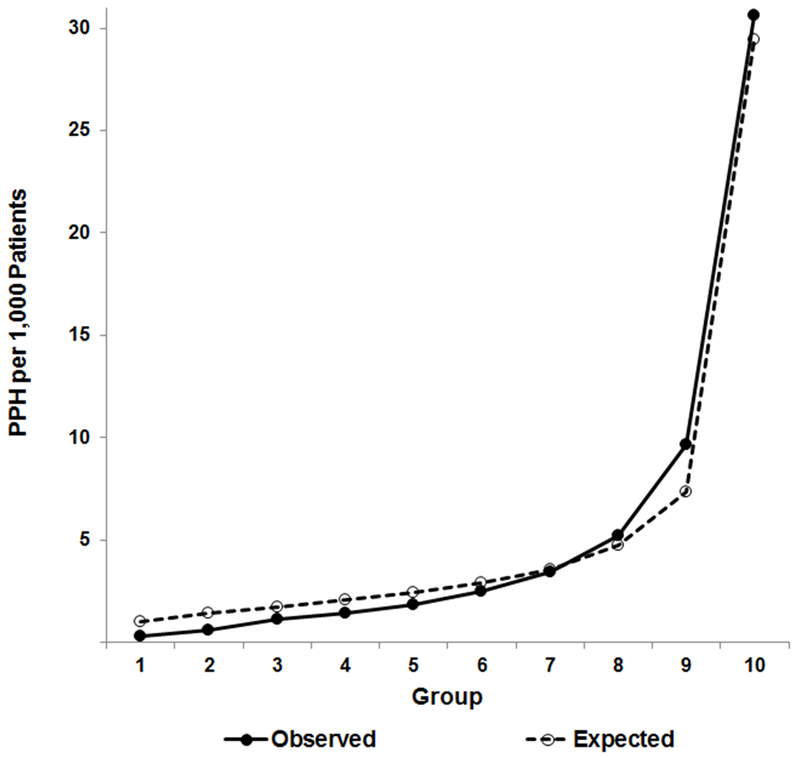

The development model had very good discrimination,28 with a c-statistic = 0.834 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.827–0.840); model coefficients are presented in Supplementary Table S3. When the model was applied to the validation and prediction cohorts, there was only a slight loss of discrimination, with c-statistics of 0.832 (95% CI 0.825–0.838) and 0.829 (95% CI 0.821–0.838), respectively. Figure 1 plots the expected (predicted) and observed PPH admission rates by decile of predicted risk for the validation cohort. The predicted rate was close to the observed rate across deciles, though the model slightly overestimated events in the lower deciles and slightly underestimated among the highest risk groups. While the Hosmer and Lemeshow statistic was significant (X2=159.8, df=8, p<0.001), this is likely a function of the large sample size.

Figure 1. Calibration curve for the predicted 30-day PPH risk model applied to the validation cohort.

The figure compares observed and expected (predicted) PPH admissions across deciles of risk among older adults with dementia in VHA. Expected events closely follow observed events, though, given the large sample size, prediction does vary across deciles, slightly over-predicting risk in the bottom deciles and slightly under-predicting risk in the top deciles (Hosmer and Lemeshow statistic: X2=159.8, df=8, p<0.001).

In each of the three cohorts of patients with dementia (Table 2), among the top 1.0% of patients by predicted 30-day PPH probability, the observed PPH rate ranged from 13.4- to 14.1-times higher than the crude rates (i.e., risk concentration). Little overfitting was indicated as seen by the consistent risk concentration across all three cohorts for each predicted probability cut-point. Of note, patients in the top 10% of predicted 30-day PPH risk accounted for 52.9% to 53.9% of 30-day PPH admissions in each cohort. Performance characteristics for various cut-points of predicted risk are presented in Table 3.

Table 2.

30-day PPH risk concentration and admission rate by cut-point of predicted 30-day PPH probability across the three cohorts

| Developmenta (n=664,355) | Validationb (n=664,357) | Predictionc (n=465,071) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted probability cut-point, % | Patients with PPH,%d | Risk concentratione | PPH rate per 1000 person-yrf | Patients with PPH,% | Risk concentration | PPH rate per 1000 person-yr | Patients with PPH,% | Risk concentration | PPH rate per 1000 person-yr |

| Top 0.1 | 2.4 | 24.3 | 1956.9 | 2.0 | 20.4 | 1635.2 | 1.9 | 18.8 | 1389.0 |

| Top 0.5 | 8.4 | 16.9 | 1317.0 | 7.7 | 15.4 | 1207.8 | 7.7 | 15.4 | 1113.3 |

| Top 1.0 | 13.6 | 13.6 | 1034.5 | 14.1 | 14.1 | 1092.7 | 13.4 | 13.4 | 953.2 |

| Top 5.0 | 38.4 | 7.7 | 564.6 | 38.5 | 7.7 | 571.8 | 37.4 | 7.5 | 512.0 |

| Top 10.0 | 53.9 | 5.4 | 389.6 | 53.8 | 5.4 | 393.1 | 52.9 | 5.3 | 357.0 |

| Top 20.0 | 70.3 | 3.5 | 250.6 | 69.5 | 3.5 | 250.3 | 69.3 | 3.5 | 230.5 |

| Top 50.0 | 91.0 | 1.8 | 127.8 | 90.1 | 1.8 | 127.8 | 90.3 | 1.8 | 118.4 |

| 100.0 | 100.0 | 1.0 | 69.7 | 100.0 | 1.0 | 70.4 | 100.0 | 1.0 | 65.1 |

c-statistic = 0.834, 95%CI: 0.827- 0.840.

c-statistic = 0.832, 95%CI: 0.825- 0.838.

c-statistic = 0.829, 95%CI: 0.821- 0.838.

The percentage of overall cohort PPH admissions accounted for by the patients within a given risk tier.

Risk concentration = (observed # PPH in risk tier) / (expected # PPH based on rate among older adults with dementia overall).

Calculated as the number of patients with PPH for each cut-point divided by the at-risk days where person-days are counted until the earliest date of PPH, non-PPH admission, death, or end of follow-up period (30 days) and expressed as per 1,000 person-years.

Table 3.

Performance characteristics by cut-point of predicted 30-day PPH risk in the prediction cohort

| Predicted probability cut-pointa, % | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPVb (%) | NPVc (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top 0.1 | 1.9 | 99.9 | 9.9 | 99.5 |

| Top 0.5 | 7.7 | 99.5 | 8.1 | 99.5 |

| Top 1.0 | 13.4 | 99.1 | 7.1 | 99.5 |

| Top 5.0 | 37.4 | 95.2 | 3.9 | 99.7 |

| Top 10.0 | 52.9 | 90.2 | 2.8 | 99.7 |

| Top 20.0 | 69.3 | 80.3 | 1.8 | 99.8 |

| Top 50.0 | 90.3 | 50.2 | 1.0 | 99.9 |

| 100.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | N/Ad |

Performance characteristics are calculated when those patients whose predicted 30-day PPH risk probability is at or exceeds the row cut-point are considered positive for PPH and the remaining patients are considered negative for PPH.

PPV: positive predictive value.

NPV: negative predictive value.

N/A due to 0 denominator.

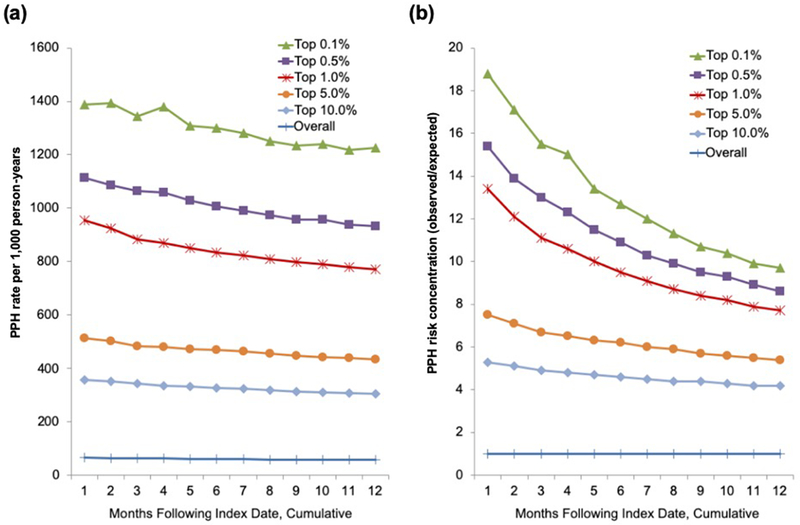

Finally, we applied our predicted 30-day probability cut-points to the prediction cohort to examine the trajectory of risk (i.e., observed PPH number, rate, and risk concentration) over one year (Figure 2, Supplementary Table S4). Older adults predicted to be at high 30-day risk of PPH had an elevated risk of admission for the entire year. For example, the top one percent had 13.4-times higher 30-day PPH risk than patients with dementia overall during the first month, but over the following year their 12-month PPH risk was still 7.7-times higher than the 12-month risk for patients with dementia overall.

Figure 2. Cumulative PPH rate and risk concentration over one year by cut-point of 30-day predicted PPH risk in the prediction cohort.

This figure demonstrates the change in (a) PPH rate and (b) PPH risk concentration (observed PPH admissions in risk tier) / (predicted PPH admissions based on the rate among older adults with dementia overall) over 12 months based on the tier of predicted risk in the prediction cohort. While the rate and risk concentration decline over time, the risk tiers maintain their relative positions at all time points and those at elevated 30-day risk continue to experience PPH admissions at higher rates all year.

DISCUSSION

Using data from over 660,000 adults with dementia, we developed a model that showed high discrimination for predicting 30-day risk of PPH using information available in the electronic health record (EHR). The model also had very good discrimination in the validation cohort (c-statistic = 0.83), indicating little over-fitting. Discrimination of the prediction model in the prediction cohort was also high (c-statistic = 0.83), while prediction cohort patients at high 30-day risk remained at elevated risk during one year of follow-up. While this model needs to be tested in other health systems to determine generalizability, our findings suggest this EHR-based approach may be feasible.

We found a PPH risk gradient among older adults with dementia: within the top 0.1%, 30-day risk of PPH was nearly 20-times higher than among patients overall. Expanding the definition of high-risk to the top 10%, a five-fold higher risk of 30-day PPH remained. While risk concentration did decrease over 12 months, those at high 30-day risk maintained persistently elevated risk. A variety of dementia care management and caregiver support programs have decreased caregiver burden, patient behavioral symptoms of dementia, or time to nursing home placement,29–32 but intervention trials have typically not reduced hospitalization.33 Null findings from randomized intervention trials may suggest these interventions do not reduce hospitalization; an alternative explanation is that participants were not risk-stratified to maximize hospitalization impact. The GRACE intervention trial, which provided care management for low-income older adults (with or without dementia), demonstrated this: there was no impact on hospitalization overall, but admissions were reduced in those who screened at high risk of hospitalization at baseline.34 Given the growing population of older adults with dementia, limited resources call for risk stratification strategies to help appropriately target interventions, rather than attempting to deliver a given intervention to all.

Claims- or administrative-data based analyses of older adults can be subject to unobserved confounding by factors such as frailty or functional status that are associated with health outcomes but are not routinely available in administrative data.35,36 Yet our model had excellent predictive ability derived entirely from structured information in the EHR, without any additional information from the patient or caregiver. In contrast, the Probability of Repeated Admission Instrument, which was used in the GRACE trial to identify the high-risk patients at baseline, has to be completed by the older adult and includes items on self-rated health and presence of an informal caregiver.37 Given the enormous demands on primary care providers’ time,14 harnessing the EHR may be a feasible means to risk-stratify these patients without requiring any additional input from providers, patients, or caregivers.

The ability of our model to identify high risk patients is notable given that the overall cohort—older adults with dementia—is, at baseline, at significantly elevated risk of admission compared to the general adult population. The predictive ability of our model is comparable to a separately-developed PPH predictive model for VA patients of all ages,23 while our model discriminates slightly better than other risk models specifically developed for older adults.22,38–41 A recent review of risk-stratification applied 6 different models—Adjusted Clinical Groups, Hierarchical Condition Categories, Elder Risk Assessment, Chronic Comorbidity Count, Charlson Comorbidity Index, and Minnesota Health Care Home Tiering—to over 80,000 primary care patients seen in a large academic health system. Across the 6 models, the c-statistic for one-year hospitalization prediction was 0.67–0.73.39

One specific model feature that may have facilitated identifying high-risk patients was the inclusion of psychotropic medications as predictors, specifically new medication starts and dosage increases. Changes to psychotropic medications may herald the presence or worsening of symptoms like agitation or psychosis.26,42 Such behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia may dominate the clinical presentation of patients with dementia, and the related caregiver distress is associated with increased hospitalization and costs for patients.25 Alternatively, such medication changes may be to treat delirium or other transient changes in mental status, which were recorded for over 40% of cohort patients in the prior 12 months. While information about behavioral symptoms is typically not available in the EHR or delirium may not be reliably recorded, incorporating information about psychotropic medication changes—which would be in the EHR—may help identify patients whose behavioral problems either reflect a worsening medical problem or are part of the constellation of symptoms that lead to hospital admission.42 Regardless of the clinical rationale for such medication changes, this information can be useful to identify high-risk older adults.

The 12-month PPH admission rate among our population—57.6 admissions per 1,000 person-years in the development sample—is, as expected for patients with dementia, higher than for adults overall in the VHA43 and older adults in the general population.44 However, the rate is lower than in an analysis of Medicare beneficiaries with dementia.20 This discrepancy between VHA and Medicare PPH rates is partially because most older VHA patients have Medicare, so some PPH admissions occur at community facilities. While this analysis was not designed to identify particular characteristics associated with PPH, it is notable that black patients experienced much higher PPH rates than other patients, in a system designed for equal access to care regardless of socioeconomic or insurance status.

A limitation of our analysis is that it only includes data from the VHA. While this limits generalizability, it suggests feasibility for other healthcare systems to develop and implement their own internal risk-prediction models. The model only captures PPH risk among patients identified with a dementia diagnosis, which likely represents the subset of patients with more advanced illness. In addition, the prediction data set is drawn from 2012, which is now over 6 years old. In 2012, the VA introduced the SAIL (Strategic Analytics for Improvement and Learning) Value Model, which includes PPH as a quality indicator. Heightened attention to PPH and other systemwide delivery changes mean a model developed with more recent data may perform differently. There is controversy over the utility of the PPH construct; a recent study found that, of AHRQ-designated preventable admissions, reviewing clinicians considered less than half preventable.45 However, Hodgson and colleagues suggest the PPH construct is still potentially useful, provided it is used to understand the underlying mechanisms increasing admission and not just to examine factors associated with admission.46 In this case, while risk prediction may help identify patients that could benefit from intervention, it cannot suggest the type of intervention that would be effective.

The acute inpatient hospital is a challenging environment for older adults with cognitive impairment, stressful to both patients and their caregivers. It is critical to proactively address healthcare issues before a crisis occurs and patients with dementia require hospitalization, particularly as the number of older adults with dementia grows. This analysis demonstrates that it is possible for healthcare systems to accurately identify older adults with dementia at high risk of imminent potentially preventable hospitalization.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Sponsor’s role: The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Funding Source: DTM was supported by the Beeson Career Development Award Program (NIA K08AG048321, AFAR, The John A. Hartford Foundation, and The Atlantic Philanthropies) and R01AG056407. KML was supported by the NIA (P30AG053760, P30AG024824, R01AG053972).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The authors have none to disclose.

Supplemental Material: Variable-defining ICD-9-CM codes, characteristics and model coefficients of the development cohort, and PPH risk decay over one year

REFERENCES

- 1.Phelan EA, Borson S, Grothaus L, Balch S, Larson EB. Association of incident dementia with hospitalizations. JAMA. 2012;307(2):165–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020. 2020 Topics & Objectives – Objectives A-Z. Available at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/default. [PubMed]

- 3.Culler SD, Parchman ML, Przybylski M. Factors related to potentially preventable hospitalizations among the elderly. Med Care. 1998;36(6):804–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krumholz HM. Post-hospital syndrome—an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. NEJM. 2013;368(2):100–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gillick MR, Serrell NA, Gillick LS. Adverse consequences of hospitalization in the elderly. Soc Sci Med. 1982;16(10):1033–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathews SB, Arnold SE, Epperson CN. Hospitalization and Cognitive Decline: Can the Nature of the Relationship Be Deciphered? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fick DM, Steis MR, Waller JL, Inouye SK. Delirium superimposed on dementia is associated with prolonged length of stay and poor outcomes in hospitalized older adults. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):500–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyketsos CG, Sheppard JM, Rabins PV. Dementia in elderly persons in a general hospital. Am J Psychiatr. 2000;157(5):704–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yaffe K, Fox P, Newcomer R, et al. Patient and caregiver characteristics and nursing home placement in patients with dementia. JAMA. 2002;287(16):2090–2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stern Y, Tang MX, Albert MS, et al. Predicting time to nursing home care and death in individuals with Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 1997;277(10):806–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr PA, Evans DA. Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010–2050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology. 2013;80(19):1778–1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phelan EA, Debnam KJ, Anderson LA, Owens SB. A systematic review of intervention studies to prevent hospitalizations of community-dwelling older adults with dementia. Med Care. 2015;53(2):207–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pimouguet C, Lavaud T, Dartigues JF, Helmer C. Dementia case management effectiveness on health care costs and resource utilization: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Nutr Health Aging. 2010;14(8):669–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caverly TJ, Hayward RA, Burke JF. Much to do with nothing: microsimulation study on time management in primary care. BMJ. 2018;363:k4983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bynum JP. The long reach of Alzheimer’s disease: patients, practice, and policy. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(4):534–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kales HC, Kim HM, Zivin K, et al. Risk of mortality among individual antipsychotics in patients with dementia. Am J Psychiatr. 2012;169(1):71–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kales HC, Valenstein M, Kim HM, et al. Mortality risk in patients with dementia treated with antipsychotics versus other psychiatric medications. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(10):1568–1576; quiz 1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maust DT, Kim HM, Seyfried LS, et al. Antipsychotics, other psychotropics, and the risk of death in patients with dementia: number needed to harm. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(5):438–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Prevention Quality Indicators Technical Specifications - Version 5.0, March 2015. http://www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov/Modules/PQI_TechSpec.aspx Accessed March 19, 2015.

- 20.Bynum JP, Rabins PV, Weller W, Niefeld M, Anderson GF, Wu AW. The relationship between a dementia diagnosis, chronic illness, medicare expenditures, and hospital use. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(2):187–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rudolph JL, Zanin NM, Jones RN, et al. Hospitalization in community-dwelling persons with Alzheimer’s disease: frequency and causes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(8):1542–1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lemke KW, Weiner JP, Clark JM. Development and validation of a model for predicting inpatient hospitalization. Med Care. 2012;50(2):131–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao J, Moran E, Li Y-F, Almenoff PL. Predicting potentially avoidable hospitalizations. Med Care. 2014;52(2):164–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Russ TC, Parra MA, Lim AE, Law E, Connelly PJ, Starr JM. Prediction of general hospital admission in people with dementia: cohort study. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;206(2):153–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maust DT, Kales HC, McCammon RJ, Blow FC, Leggett A, Langa KM. Distress Associated with Dementia-Related Psychosis and Agitation in Relation to Healthcare Utilization and Costs. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;25(10):1074–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maust DT, Langa KM, Blow FC, Kales HC. Psychotropic use and associated neuropsychiatric symptoms among patients with dementia in the USA. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCarthy JF, Bossarte RM, Katz IR, et al. Predictive Modeling and Concentration of the Risk of Suicide: Implications for Preventive Interventions in the US Department of Veterans Affairs. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(9):1935–1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meurer WJ, Tolles J. Logistic Regression Diagnostics: Understanding How Well a Model Predicts Outcomes. JAMA. 2017;317(10):1068–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amjad H, Wong SK, Roth DL, et al. Health Services Utilization in Older Adults with Dementia Receiving Care Coordination: The MIND at Home Trial. Health Serv Res. 2017;23(3):271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Callahan CM, Boustani MA, Unverzagt FW, et al. Effectiveness of collaborative care for older adults with Alzheimer disease in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(18):2148–2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mittelman MS, Ferris SH, Shulman E, Steinberg G, Levin B. A family intervention to delay nursing home placement of patients with Alzheimer disease. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1996;276(21):1725–1731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mittelman MS, Haley WE, Clay OJ, Roth DL. Improving caregiver well-being delays nursing home placement of patients with Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67(9):1592–1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klug MG, Halaas GW, Peterson ML. North Dakota assistance program for dementia caregivers lowered utilization, produced savings, and increased empowerment. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(4):605–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Clark DO, et al. Geriatric care management for low-income seniors: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298(22):2623–2633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kharrazi H, Anzaldi LJ, Hernandez L, et al. The Value of Unstructured Electronic Health Record Data in Geriatric Syndrome Case Identification. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;60:896–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim DH, Schneeweiss S. Measuring frailty using claims data for pharmacoepidemiologic studies of mortality in older adults: evidence and recommendations. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2014;23(9):891–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boult C, Dowd B, McCaffrey D, Boult L, Hernandez R, Krulewitch H. Screening Elders for Risk of Hospital Admission. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1993;41(8):811–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coleman EA, Wagner EH, Grothaus LC, Hecht J, Savarino J, Buchner DM. Predicting hospitalization and functional decline in older health plan enrollees: Are administrative data as accurate as self‐report? J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46(4):419–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haas LR, Takahashi PY, Shah ND, et al. Risk-stratification methods for identifying patients for care coordination. American J Managed Care. 2013;19(9):725–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crane SJ, Tung EE, Hanson GJ, Cha S, Chaudhry R, Takahashi PY. Use of an electronic administrative database to identify older community dwelling adults at high-risk for hospitalization or emergency department visits: the elders risk assessment index. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10(1):338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Inouye SK, Zhang Y, Jones RN, et al. Risk factors for hospitalization among community-dwelling primary care older patients: development and validation of a predictive model. Med Care. 2008;46(7):726–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kales HC, Gitlin LN, Lyketsos CG. Assessment and management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. BMJ. 2015;350(mar02 7):h369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Finegan MS, Gao J, Pasquale D, Campbell J. Trends and geographic variation of potentially avoidable hospitalizations in the veterans health-care system. Health Serv Manage Res. 2010;23(2):66–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCall N, Harlow J, Dayhoff D. Rates of hospitalization for ambulatory care sensitive conditions in the Medicare+ Choice population. Health Care Financ Rev. 2001;22(3):127. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patel KK, Vakharia N, Pile J, Howell EH, Rothberg MB. Preventable admissions on a general medicine service: prevalence, causes and comparison with AHRQ prevention quality indicators—a cross-sectional analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(6):597–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hodgson K, Deeny SR, Steventon A. Ambulatory care-sensitive conditions: their potential uses and limitations. BMJ Quality Safety. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.