Abstract

With the advent of immunomodulatory therapies and the HIV epidemic, the impact of JC Virus (JCV) on the public health system has grown significantly due to the increased incidence of Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy (PML). Currently, there are no pharmaceutical agents targeting JCV infection for the treatment and the prevention of viral reactivation leading to the development of PML. As JCV primarily reactivates in immunocompromised patients, it is proposed that the immune system (mainly the cellular-immunity component) plays a key role in the regulation of JCV to prevent productive infection and PML development. However, the exact mechanism of JCV immune regulation and reactivation is not well understood. Likewise, the impact of host factors on JCV regulation and reactivation is another understudied area. Here we discuss the current literature on host factor-mediated and immune factor-mediated regulation of JCV gene expression with the purpose of developing a model of the factors that are bypassed during JCV reactivation, and thus are potential targets for the development of therapeutic interventions to suppress PML initiation.

Keywords: JC virus, PML, immunosuppression, reactivation, diagnosis, therapy

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

In Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy (PML), multiple pathological changes occur affecting both glial cells and neuronal axons. PML is caused by reactivation of the JC virus (JCV), a polyomavirus that forms long-term latent infections in a majority of the human population. After reactivation of JCV, oligodendrocytes appear as the primary cells with productive infection. Astrocytes, however, were also identified to have functional infection by JCV (Ferenczy et al, 2012; Astrom et al, 1958). Following reactivation, viral proteins are expressed in both glial cell populations, leading to cellular lysis and focal destruction of the myelin protein (Cavanaugh et al, 1959; Brooks and Walker, 1984). This widespread loss of myelin results in axonal dysfunction and a retrograde loss of the neuronal cell bodies due to cellular insults on the demyelinated axons. This neural loss is likely a permanent result of PML (Cinque et al, 1996).

While JC virus infection is common among humans, incidence of reactivation and progression of PML is quite low. (Ferenczy et al, 2012). PML was first classified as a very rare disease, only being associated with pre-existing oncological conditions which impacted the immune system. This largely remained the case until widespread use of immunomodulatory therapies for neurological diseases such as multiple sclerosis (MS), as well as the AIDS epidemic (Astrom et al, 1958; Richardson 1961). Possible PML diagnoses date back in literature to 1930, although the first officially-recorded case wasn’t until 1958 when a patient symptomatic of chronic lymphocytic leukemia and Hodgkin’s lymphoma was found to have pathologies similar to PML, including the development of white matter plaques at various locations throughout the brain (Astrom et al, 1958; Richardson 1961; Bateman et al, 1945; Christensen and Fog, 1955; Hallervorden, 1930; Winkleman and Moore, 1941). Statistically, between 3 to 5% of all AIDS patients may develop PML at some point during the course of their disease. This is a significantly higher rate compared to patients with other means of immunomodulation therapy (Major, 2010). However, HIV/AIDS is just one of the risk factors for PML development, as increased risk of immunomodulatory therapy has resulted in PML development being a serious side effect. Recently, the use of monoclonal antibody therapies as a pharmaceutical method of modulating the immune response to various targets has become more common. Unfortunately, many of these therapies have resulted in fatal cases of PML in patients treated with monoclonal antibodies for the modulation of different subsets of immune cells (Lipsky, 1996). There have also been similar cases reported in non-monoclonal antibody immunomodulatory therapies, including mycophenolate mofetil, which is used to reduce the likelihood of rejection following an organ transplant (Lipsky, 1996). All of these drugs play a major role in the reactivation of JCV by limiting the surveillance of the immune system at major sites of reactivation, perhaps most notably the brain.

JCV genome and viral genes

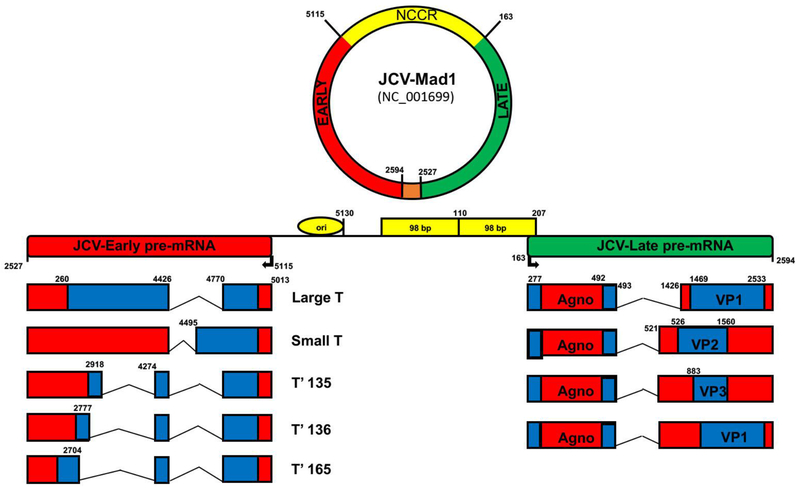

Similar to the other polyomaviruses, JCV is a non-enveloped icosahedral virus with a closed, circular, double-stranded DNA genome. The archetype JCV genome is ~5k base pairs in length, although JCV is typically found in variant forms, which contain differences in genome size resulting from mutations within the non-coding control region. The genome is split into two distinct regions (the early coding region and the late coding region) and is separated by the viral non-coding control region NCCR which contains the origin of viral replication (Figure 1). The early region is transcribed prior to DNA replication and contains the genes for the regulatory tumor antigens (large T-antigen, small t-antigen, T’135, T’136, and T’165). The late region is transcribed simultaneously with DNA replication and encodes the three capsid proteins (VP1, VP2, VP3), as well as the regulatory agnoprotein. During JCV infection, viral proteins are able to interact with both host and viral factors, including other proteins and DNA during the infectious and replication cycles. The T-antigens are involved in viral replication through several different mechanisms, including shifting of the host cell toward S phase for viral replication through p53 inactivation, and regulation of both host and viral genome transcription through interactions with RNA polymerase. The virus produces four proteins within the late region: the regulatory Agnoprotein, as well as the viral capsid proteins VP1, VP2, and VP3. Agnoprotein functions in multiple ways, including some ways that are still being identified today. During JCV infection of permissive cells, agnoprotein is found primarily in the cytoplasm, with perinuclear localization (Okada et al, 2001, Del Valle et al, 2001). These results are confirmed within the PML brain, with immunohistochemical staining showing similar cytoplasmic and perinuclear localization of agnoprotein within lesion sites (Okada et al, 2001). In terms of function, much remains to be elucidated for agnoprotein. Currently, there are limited studies assessing the function of agnoprotein. One study suggests that agnoprotein works as a viroporin (Suzuki et al, 2010). This hypothesis is bolstered by our studies showing that JCV agnoprotein mutants release viral particles that are defective in viral DNA (Sariyer and Khalili, 2011). It is also shown that agnoprotein interacts with JCV T-antigen to enhance T-antigen’s DNA binding activity to the viral origin of replication, resulting in enhanced viral replication (Saribas et al, 2010). Furthermore, agnoprotein is released from infected glial cells during viral propagation, and is present in the extracellular matrix (Otlu et al, 2014; Craigie et al., 2018; Saribas et al., 2018). The release and detection of agnoprotein in the extracellular matrix suggests a novel role of agnoprotein in the molecular pathogenesis of JCV. The three structural proteins are VP1, VP2, and VP3, with VP1 being the major capsid protein. The viral capsid proteins function in cellular binding and entry through various negatively-charged sialic-acid receptors on the cell membrane (Dugan et al, 2008; Liu et al, 1998; Neu et al, 2011).

Fig. 1.

Organization of JC virus (JCV) genome. JCV genome is a double-stranded circular DNA genome which contains a bidirectional non-coding control region (NCCR, yellow), which separates the early (red) and late (green) coding regions. Prior to DNA replication, the early coding region of JCV is transcribed, resulting in expression of the JCV regulatory T-antigen proteins, including large T-antigen, small t-antigen, and the T-prime splice variants, which are expressed following the alternative splicing of the early viral transcript. After early coding region transcription, both DNA replication of the genome as well as transcription of the late coding region of JCV occur simultaneously. The late coding region of JCV encodes the viral capsid proteins, VP1, VP2, and VP3, as wells as the small regulatory agnoprotein. Positions of nucleotides on circular viral genome are numbered relative to the Mad-1 reference strain (GenBank # NC-001699). Orange color on circular viral genome depicts the overlapping region for early and late transcripts.

JCV infection and viral life-cycle

JCV is an extremely wide-spread virus with studies showing roughly 75% of the human population is serotype positive for neutralizing antibodies against JCV. While this does indicate prior exposure to the virus, it is important to note that the rate of serotype positivity varies among different subpopulations and cultures (Knowles et al, 2003; Major et al, 1998). The exact mechanism behind the infection is not currently known, however, the current model involves respiratory inhalation or oral-ingestion of virally-contaminated food or water (Berger et al, 2006). This model, based on evidence where JCV was found to infect tonsillar stromal cells and hematopoietic progenitor cells, led to the hypothesis that the primary route of infection is through the stromal cells or the immune cells within the upper respiratory system (Monaco et al, 1996). Following primary infection, JCV travels through the body to peripheral sites, allowing for latent infection. JCV demonstrates a highly-restricted host cell range due to various aspects of the viral life cycle. Studies in vivo have suggested that JCV infection is restricted to oligodendrocytes, astrocytes, kidney epithelial cells, tonsillar stromal cells, and bone-marrow derived cell lineages (Monaco et al, 1996; Houff et al, 1988; Major et al, 1992; Tornatore et al, 1992; Monaco et al, 1996; Major et al, 1990; Atwood et al, 1992).

The initial infection of permissive host cells requires the interaction of sialic-acid containing receptors on the cell surface and the capsid proteins of JCV (Dugan et al, 2008). Further, JCV may interact with receptor ligands to allow entry into the cell, which is precisely the case with the oligosaccharide lactoseries tetrasaccharide C (LSTc). Additionally, there have been studies demonstrating that JCV may utilize the serotonin receptor 5HT2AR to infect permissive glial cells (Elphick et al, 2004). In 2003, Baum et al showed that both Chlorpromazine and Clozapine, two antipsychotic medications which act as antagonists against dopamine and serotonin receptors, both possess antiviral activity against JCV, which led to the hypothesis that JCV may interact with these neurotransmitter receptors to enter permissive cells, perhaps explaining the high glial-tropism (Baum et al, 2003). This hypothesis was even further supported after studies showed that expressing the receptor on HeLa and HEK293 cells allowed for viral entry, and that blocking the receptor with specific antibodies prevented infection from occurring (Elphick et al, 2004; Maginnis et al, 2010). JCV enters cells through a clathrin-dependent endocytosis pathway (Pho et al, 2000). After initial binding, JCV is trafficked from clathrin-coated pits to Rab5-positive early endosomes, a process which is inhibited by dominant negative Eps15 mutants, which blocks the assembly of clathrin coated pits (Pho et al, 2000; Querbes et al, 2004). After initial trafficking, JCV co-localizes with cholera toxin B in compartments which are hypothesized to be caveolin-1-positive late endosomes (Engel et al, 2011; Querbes et al, 2006). Once co-localization has occurred, JCV was found to further co-localize with calregulin, which leads to the hypothesis that productive infection of JCV requires trafficking to the ER (Querbes et al, 2006). The importance of ER trafficking for JCV is currently not known. Following nuclear translocation of the JCV genome, the genome can serve as a template for host RNA polymerase II transcriptional machinery (Ferenczy et al, 2012). Immediate early transcription of JCV genes can begin in the absence of viral proteins and utilizes the host proteins only, which may have further implications for cell type tropism of the virus. Initiation of transcription occurs post-interaction of the viral NCCR with host transcription factors. JCV NCCR contains various transcriptional factor binding sites, allowing for interactions with Oct-6/tst-1/SclP, Pur-α, NFI, Spi-B, SRSF1, as well as other transcription factors within the host cell (Ferenczy et al., 2012, Wegner et al., 1993, Chen et al., 1997, Kerr et al., 1994, Tada and Khalili, 1992, Amemiya et al., 1992, Shivakumar and Das, 1994, Marshall et al., 2010, Uleri et al., 2011, Sariyer and Khalili, 2011). When the virus initially infects a permissive cell type, it does not contain any viral transcriptional activating proteins, unlike many other human DNA-viruses, resulting in viral transcription being controlled by host factors in all facets.

JCV DNA replication is initiated following early gene transcription and large T-antigen production. As with other polyomaviruses, the JCV large T-antigen can bind to the origin of viral replication at a pentanucleotide consensus sequence of GAGGC, forming a tertiary structure required for the initiation of viral genomic DNA replication (Major et al, 1992; Frisque, 1983; Amirhaeri et al, 1988). In parallel, T-antigen drives the host cell toward replication by shifting the cell towards the S-phase through interactions with retinoblastoma protein (pRb) and p53 (Bollag et al, 2000; Tavis et al, 1994; White and Khalili, 2006; Del Valle et al, 2001). There are many factors that contribute to JCV DNA replication, including T-antigen, host DNA polymerase, and many host cellular proteins. While the exact replication process of JCV is not fully understood, it is believed to be similar to the replication process of SV40. During SV40 DNA replication, T-antigen forms a double hexamer structure, allowing it to function as a helicase to unwind viral DNA and form a complex with topoisomerase I, DNA polymerase a, and replication protein A (RPA) to initiate DNA replication (Bullock et al, 1991; Fairman and Stillman, 1988; Nesper et al, 1997). Aside from initiation of replication, T-antigen also functions during the elongation process through interactions with DNA polymerase δ, PCNA, and replication factor C (Lee and Hurwitz, 1990; Tsurimoto et al, 1990; Weinberg et al, 1990). Following completion of the bi-directional replication, the JCV genome exists as two interlinked circles, which are cleaved and re-ligated through the function of topoisomerase I and topoisomerase II (Nesper et al, 1997).

PML and neuroimmune response to JCV

The reactivation of JCV from a latent or non-productive state to a productive infection in glial cells is the etiologic cause of PML. The pathology of PML is the infection of oligodendrocytes, which is characterized by the presence of inclusion bodies in the nuclei of infected cells, as well as loss of chromatin structure and abnormally large nuclei. Following JCV replication in oligodendrocytes, the cells undergo lysis, allowing the viral particles to spread to neighboring uninfected cells. Ultimately, this results in the widespread, or focal, destruction of myelin. Although oligodendrocytes are the primary cells infected by JCV, astrocytes are also capable of being infected by JCV, resulting in significant morphological changes leading to the formation of “bizarre astrocytes” found in PML-brains (Mázló and Tariska, 1982). These bizarre astrocytes are significantly larger than non-infected astrocytes and contain irregular nuclei. Another major pathological characteristic of the PML-brain is the destruction of neurons. However, neurons possess a very limited capacity for being infected in a productive manner by JCV. The mechanism behind neuronal loss is due to demyelination, as demyelinated axons become vulnerable to extracellular insults, mainly due to the release of products by glial cells. These insults result in axonal injury which causes a loss of the neuronal cell body, believed to be a permanent effect of PML.

Likewise, there is a peripheral response to the CNS lesions of PML as well. The most common peripheral cells found at sites of PML lesions are invading macrophages, which are generally present in the centers of the lesions. The peripheral macrophages act as scavengers to remove debris-primarily the remnants of the myelin destroyed during the demyelination aspect of PML. Monocyte-derived cells do not appear able to be infected by JCV, as neither peripheral or CNS macrophages nor microglia have been shown to be infected (Yadav and Collman, 2009; Wiley et al, 1988). While a limited number of monocytes are capable of infiltrating to PML lesions, lymphocytes are generally not seen at the sites of infection, resulting in a limited inflammatory response which is counterintuitive to what would be expected with the high amounts of tissue damage. However, significant lymphocytic migration and inflammation occurs if the immune system is restored during PML infection, leading to a condition referred to as Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome (PML-IRIS). In PML-IRIS, peripheral immune cells migrate to perivascular regions and the parenchyma in close vicinity to JCV-infected cells, with the primary cellular population being CD8+ T-cells (Wüthrich et al, 2006; Vendrely et al, 2005). The rapid infiltration of immune cells following immune reconstitution results in extensive inflammation within the CNS of these PML-IRIS patients, resulting in increased cytotoxicity and damage to the CNS (Gheuens et al., 2012; Sierra et al., 2017). IRIS has been often associated with HIV-infected patients following the initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) (Bowen et al., 2018). In HIV-positive patients, IRIS is developed in 17-30% of the cases (Muller at al., 2010). A significant number of PML-IRIS cases (157 cases between 1998 and 2016) have been reported once the underlying immunomodulatory therapies are withdrawn or immune reconstitution was achieved (Fournier et al., 2017). At pathological level, PML and PML-IRIS lesions present similar distribution and characteristics. At neuropathological and MRI level, PML-IRIS has different features: PML-IRIS lesions contain increased numbers of T cells and B cells however the number of macrophages does not vary from PML (Martin-Blondel et al., 2013). In a cross-sectional study, it has been reported that HIV-associated PML–IRIS presents 60 times more CD20+ B cells, 16 times more CD8+ T cells, and 700 times more CD138+ plasma cells (Martin-Blondel et al., 2013). Furthermore, some studies have also shown an implication of chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5)-positive T cells in IRIS (Schwab et al., 2012; Martin-Blondel et al., 2015). There are no treatment guidelines for PML-IRIS. Therapeutic strategies targeting neuroinflammation with a minimal impact on immune system are yet to be developed.

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and PML

Among more recent developments with regard to potential therapeutics, immune checkpoint Inhibitors such as Nivolumab and Pembrolizumab have been considered as a possible treatment for PML (Cortese et al., 2019; Rauer et al., 2019), but it is important to note that these can also lead to potential triggering factors. Both of these drugs are monoclonal antibodies (MABs) that target programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), which is an inhibitory T-cell surface receptor that prevents one’s immune system from attacking their body’s own organs and tissues. The drugs work by blocking PD-1’s ability to bind its ligand, preventing inhibition of T-cell proliferation and production of cytokines. The two drugs are very similar, despite the fact that they target different parts of the PD-1 protein. Both are IgG4 molecules that are capable of crossing the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB), with a half-life of 26 days. In the study cited above by Koralnik, 2019, treatment using Nivolumab and Pembrolizumab resulted in a decrease of PD-1–binding CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in blood. Among six patients with PML that had data available, four of six patients with PML who had a low but detectable number of JC virus-specific CD4+ T cells at baseline had an increase in the number of these cells after treatment. These patients also presented better clinical outcomes, whereas the two other patients with an undetectable number of JC virus-specific cells at baseline did not have a response and died from PML. It should be noted, however, that no data was presented on the effect of PD-1 on JC virus-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes, which are the most important effectors of the cellular immune response (Gheuens et al, 2011). After Pembrolizumab treatment in two patients with CLL and a remote history of Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (respectively), the JC viral load detected in the CSF of two patients decreased to levels just above detectable within one month after treatment. Another patient, who was HIV positive, had evidence of in vitro reinvigoration of anti-JCV T-cell response within 1 month after initial infusion of pembrolizumab. The reactivity against JC viral peptide LT was more than 2x as high as the baseline level, and the reactivity against JC viral peptide VP1 was over 10x as high as the baseline level.

In a recent case report published by Cortese et al, eight adults who were symptomatic for PML were enrolled in the NIH Natural History Study of PML (ClinicalTrials.gov number, ) and also the Inflammatory and Infectious Diseases of the Nervous System study (). Pembrolizumab was given by IV at a dose of 2mg per kg of body weight, every 4 to 6 weeks with a maximum of three doses per patient. By using ultra-sensitive multiplex quantitative PCR, researchers were able to detect JC virus genomic DNA in patient CSF samples. Among the eight patients, the JC viral load in the CSF at the initial NIH evaluation ranged from 63 to 28,350 copies per milliliter. The immune conditions underlying PML were human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection in two patients, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) in two patients, remote history of Hodgkin’s lymphoma in one patient, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in one patient, and idiopathic lymphopenia in two patients (Cortese et al, 2019). Five of these eight patients experienced a reduction in JCV viral load in the CSF which was temporally associated with reinvigoration of in vitro anti–JC virus cellular immune responses. Four of these five patients continued to display reduction in JCV viral load, including no recurrence of PML up to 26 months after their final dose of Pembrolizumab. In another study by Rauer et al, a patient was treated with Pembrolizumab at the same dosage but a total of five infusions. Conditions improved and JCV was not detectable in the CSF. In the case reported above, the authors’ results support the idea that blocking PD-1 or its ligands (PD-L1 and PD-L2) can help JCV infection. The complete mechanisms behind the PD-1 blockade and the use of ongoing infusions in patients with PML are still unclear. Moving forward, larger clinical trials and more mechanistic studies are needed in order to gain a better insight in to the effect of immune checkpoint Inhibitor treatments.

Risk Factors associated with JCV reactivation and development of PML

While the rates of JCV infection are significantly high in terms of the serotype positive population, the incidence of JCV reactivation and PML remain extremely low in comparison, and only occurs following a significant change in immunological function. Therefore, it follows that there must be a strong negative regulation of JCV by host factors, including cellular factors and the host immune system, in controlling the infection. With the advent of monoclonal antibodies and other immunomodulatory therapies to treat a wide-range of diseases, it is not surprising that PML is associated with some of these pharmacological agents (Table 1). Typically, these therapies are used to treat autoimmune diseases (such as Multiple Sclerosis or Rheumatoid Arthritis), or lymphoproliferative diseases (such as Lymphomas or Leukemias). However, these therapies carry a substantial risk for the development of PML due to changes in the immune system function of these patients. One example of an immunomodulatory therapy which carries a high risk for PML development is natalizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody mainly used to treat relapsing multiple sclerosis. Natalizumab functions by binding to the a4 chain of very late antigen-4 (VLA-4), which mediates cell migration and infiltration in immune signaling through its binding to the vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM), allowing leukocytes to bind to the endothelial cells of blood vessels for extravasation out of circulation to sites of inflammation (Engelhardt and Kappos, 2008; Rice et al, 2005). The hallmark of Multiple Sclerosis is chronic leukocytic infiltration into the brain, which is potently blocked by treatment with Natalizumab. Another effect of Natalizumab treatment is to impact the B-cell population, functioning to increase CD34+ progenitor cells in the blood and bone marrow, increasing circulating pre-B and B cells in the periphery, and increasing the expression of factors involved in the differentiation of B cells from their progenitors (Jing et al, 2010; Krumbholz et al, 2008; Lindberg et al, 2008). Importantly, one factor upregulated by Natalizumab treatment is Spi-B, a factor involved in promoting the differentiation of B cells which has also been found to increase JCV transcription, thus functioning as a possible mechanism for increased PML risk following Natalizumab therapy (Marshall et al, 2010). Currently, it has been approximated that 3.5 per 1,000 patients undergoing therapy with Natalizumab may develop PML-however, the true incidence still remains to be determined.

TABLE 1:

Examples of monoclonal antibody therapies associated with PML risk.

There are many other immunomodulatory therapies that significantly increase the risk of developing PML over the course of the therapy. Rituximab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that targets CD20 and is used to treat hematological cancers, such as non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, as well as autoimmune diseases such as Rheumatoid Arthritis. Treatment with Rituximab results in the destruction of peripheral B cells, as binding of the antibody to CD20 results in NK-cell mediated killing of B-cells, as well as inducing apoptosis in these cells (Rudnicka et al, 2013). Destruction of B-cells serves to remove malignant or auto-reactive B-cells from the periphery, resulting in replacement by pre-B cells in the bone marrow. However, as JCV is suggested to infect hematopoietic progenitors in the bone marrow, this treatment may serve to increase the population of JCV positive B-cells in the body (Major, 2010; Reff et al, 1994; McLaughlin et al, 1998). Efalizumab is another humanized monoclonal antibody that targets CD11b and was used to treat Psoriasis. Treatment with Efalizumab resulted in disruption of leukocyte function-associated antigen type 1 (LFA-1) binding to intercellular adhesion molecular 1 (ICAM-1), which served to prevent the migration of T lymphocytes to sites of inflammation (Lebwohl et al, 2003). However, in 2009, Efalizumab was withdrawn from the market by Genentech, Inc. due to the occurrence of PML following treatment, which affected 1 in 500 patients treated with the drug. It appears that the mechanism behind the increased risk of PML following immunomodulatory therapy is multifaceted, with the over-arching theme being a significant decrease in immune surveillance as well as the differentiation of progenitor cells into terminally differentiated lymphocytes, potentially serving as a mechanism for dissemination of latent JCV into the CNS. While immunomodulatory therapies increase the risk of developing PML, the cohort with the most significant risk for developing PML remains AIDS patients, as PML occurs at significantly higher rates in this cohort than in cohorts with other causes of immunosuppression. Currently, PML is reported to be the cause of death in 3 to 5% of AIDS patients, which represents a significant population (Major, 2010). As a disease, AIDS has a very widespread negative impact on the immune system and immunological function, as it presents chronic immunosuppression, impacts cytokine release and shifts towards a more “pro-viral” cytokine profile, and increases the permeability of the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) to allow infected cells to enter the brain (Houff and Berger, 2008). Studies have suggested that HIV and JCV interact in a synergistic manner, resulting in PML occurrence in these patients. Both HIV and JCV can remain latent in CD34+ progenitor cells, which, following expansion of these cells into B-cells, both viruses appear to possess reactivation capabilities (Monaco et al, 1996; Houff and Berger, 2008; Carter et al, 2010). Likewise, HIV Tat protein has been shown to interact with JCV, primarily through increasing the transcription of both early and late regions of JCV, and increases JCV propagation when infected cells express Tat (Chowdhury et al, 1993; Chowdhury et al, 1990; Chowdhury et al, 1992; Nukuzuma et al, 2010; Stettner et al, 2009; Tada et al, 1990). In vitro studies have demonstrated that Tat secreted from infected cells and oligodendrocytes were able to uptake the protein, which leads to the hypothesis that uptake of extracellular Tat by oligodendrocytes could be one of the initial mechanisms for JCV reactivation in AIDS patients (Ensoli et al, 1993; Daniel et al, 2004; Taylor et al, 1992; Enam et al, 2004). Infection with HIV also significantly increases the permeability of the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) and increases peripheral lymphocyte migration into the brain- two mechanisms which may result in increased JCV in the brain and eventual reactivation and PML development, primarily through Tat protein-mediated activation of CCL2 (Puri et al, 2010; Ault, 1997; Ikegaya and Iwase, 2004; Berger et al, 2001; Petito and Cash, 1992). There is some semblance of a relationship between JCV and HIV in which HIV changes the host conditions significantly enough to allow for reactivation of JCV, however, the exact mechanisms in this relationship still need to be further investigated.

Host-genes and JC Virus regulation

While the immune system is primarily implicated in controlling JCV infection, other non-immunological factors also play a major role in the regulation of JCV and inhibiting viral reactivation. One such factor is the alternative splicing factor Serine/Arginine-Rich Splicing Factor 1 (SRSF1), which is involved in the alternative splicing of human pre-mRNA. While playing a constitutive role in the host cell, SRSF1 also possesses antiviral capabilities by impacting viral splicing in infected cells. Originally, SRSF1 was identified as a negative regulator of Simian Virus 40 (SV40), which is another viral member of the polyomaviridae family, where SRSF1 was found to impact early gene splicing, which suppressed expression of large and small T antigens (Ge and Manley, 1990). Similar to its function against SV40, SRSF1 negatively regulates JCV, however the exact mechanism behind this suppression was different from SV40. For JCV, SRSF1 primarily suppressed viral transcription and replication in glial cells, mainly through interaction with the JCV promoter DNA sequence (Sariyer and Khalili, 2011). Likewise, when astrocytes were treated with shRNA against SRSF1 and then infected with JCV, there was a significant increase in viral protein production, suggesting that JCV replication is suppressed by SRSF1 expression. SRSF1 also impacts the expression of all JCV proteins, most likely as a consequence of transcriptional suppression, and the suppression of the viral proteins inhibits the transforming properties of the T-antigens (Uleri et al, 2011). While SRSF1 possesses a strong negative regulatory impact of JCV, the viral proteins also possess the capability to rescue this suppressive mechanism. The expression of large T antigen in cells was sufficient to rescue transcriptional suppression mediated by the over-expression of SRSF1. Further studies revealed that large T antigen could suppress the expression of SRSF1 in glial cells via interaction with the SRSF1 promoter to inhibit SRSF1 transcription (Craigie et al, 2015). This interaction between viral proteins and host cellular factors represents a novel finding into the mechanisms underlying the reactivation of JCV from a latent state to a productive infection. Likewise, there appears to be an interaction between SRSF1 and the immune suppression of JCV, with soluble immune factors possibly mediating SRSF1 expression as an antiviral mechanism. The treatment of glial cells with conditioned media from induced peripheral blood mononuclear cells resulted in a strong negative suppression of early and late gene transcription of JCV. Likewise, it was found that this treatment resulted in increased expression of SRSF1 through an unknown mechanism. These data suggest a novel pathway for indirect immunological suppression of JCV, with the immune system functioning to control JCV gene expression through the induction of the expression of cellular negative regulators of the virus, such as SRSF1 (Sariyer et al, 2016).

During JCV infection and subsequent replication, the cellular tropism of JCV is thought to be primarily regulated at the transcriptional level. Some of the transcriptional factors that have been described to interact with the JCV promoter region include NF-κB, Tst-1, Y-box binding protein 1, c-Jun, nuclear factor 1x (NF-1) and Pura (Wegner et al, 1993, Kerr et al, 1994; Ranganathan and Khalili, 1993; Chen et al, 1995; Ravichandran et al, 2006). It is important to note that transcriptional factor expression varies among cell types that appear to be one of the major contributors to viral tissue tropism (Ravichandran et al, 2006). An example of one transcriptional factor that appears to play a major role in JCV gene expression is NF-1X, a member of the NF-1 family of transcriptional factors which is highly expressed in cell types which support JCV expression, including glial cells, B-lymphocytes, tonsillar stromal cells, and cells of an astrocytic lineage (Ravichandran et al, 2006). Following NF-1X binding to the JCV promoter region, there is a significant increase in the expression of major capsid protein 1 (VP1), which is indicative of increased viral gene expression (Ravichandran et al, 2006).

However, while some transcriptional-factors appear to increase JCV gene expression, other transcriptional factors appear to act as negative regulators of JCV gene expression through various mechanisms, including binding directly to the JCV promoter sequence or by interacting with positive-regulatory factors of JCV gene expression. A transcriptional factor which utilizes both of these mechanisms to negatively regulate JCV gene expression is c-Jun, a member of the AP-1 family of transcriptional factors. The binding of c-Jun to the JCV promoter region prevents the binding of NF-1X to the promoter, most likely in part with masking the NF-1X binding site, resulting in decreased JCV activity and replication (Ravichandran et al, 2006). While c-Jun is able to directly interact with the JCV promoter itself to negatively regulate JCV gene expression, it is also able to interact in a protein-protein function with positive regulators of JCV gene expression in order to suppress their ability to interact with the JCV promoter region. An example of this is that c-Jun is able to bind to NF-1X protein within the cell, preventing interaction of NF-1X with the JCV promoter region (Ravichandran et al, 2006). This function serves to eliminate free NF-1X from infected cells as a method to suppress JCV infection within the cells in which NF-1X is highly expressed. This multilevel interaction between c-Jun, NF-1X, and JCV demonstrates the complexity involving the regulation of JCV by host factors. In addition to the expected transcriptional factor binding to the JCV promoter to either positively or negatively regulate JCV gene expression, there also exists protein-protein interactions between host factors to suppress or induce the binding of various transcriptional factors to the JCV promoter sequence.

Conclusions

While PML at one point was an extremely rare disease, the onset of the AIDS epidemic as well as the increased usage of immunomodulatory therapies to treat diseases has resulted in a significant increase in the number of PML diagnoses. Currently, it is hypothesized that there are four changes which must occur for a patient to develop PML: there must be significant immunosuppression or alteration of the host immune state, the viral promoter must undergo recombination events allowing for increased viral transcription and replication in permissible cells, permissive cells must have tissue specific expression of various transcription factors which interact with the viral promoter, and the virus must cross the blood-brain barrier to infect oligodendrocytes. If all of these factors are met, it is hypothesized that the patient may ultimately develop PML. Since the discovery of JCV as the etiologic agent for PML, most research has focused upon analyzing the immunological deficits allowing for the reactivation of JCV. While immune suppression is required for the development of PML, this research generally excluded non-immunological control of the virus in cells. Discovery of host factors which act in an anti-viral manner against JCV may offer possible therapeutic potential in the treatment of PML.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was made possible by grants awarded by NIH to IKS (AI101192).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethical Standards:

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amemiya K, Traub R, Durham L, Major EO (1992) Adjacent nuclear factor-1 and activator protein binding sites in the enhancer of the neurotropic JC virus. A common characteristic of many brain-specific genes. J. Biol. Chem 267:14204–14211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Tawfiq JA, Banda RW, Daabil RA, Dawamneh MF. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) in a patient with lymphoma treated with rituximab: A case report and literature review. J Infect Public Health. 2015, Sep-Oct;8(5):493–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amirhaeri S, Wohlrab F, Major EO, Wells RD (1988) Unusual DNA structure in the regulatory region of the human papovavirus JC virus. J. Virol 62:922–931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Astrom KE, Mancell EL, Richardson EPJ. (1958) Progressive multifocal encephalopathy: A hitherto unrecognized complication of chronic lymphocytic leukemia and lymphoma. Brain. 81, 99–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atwood WJ, Amemiya K, Traub R, Harms J, Major EO (1992) Interaction of the human polyomavirus, JCV, with human B-lymphocytes. Virology 190, 716–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ault GS (1997) Activity of JC virus archetype and PML-type regulatory regions in glial cells. J. Gen. Virol 78:163–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bacchetta F, Mathias A, Schluep M, Du Pasquier R. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in two natalizumab-treated stepsisters: An intriguing coincidence. Mult Scler. 2017. February;23(2):300–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bateman OJ, Squires G, Thannhauser SJ (1945) Hodgkin’s disease associated with Schilder’s disease. Ann. Intern. Med 22, 426–431. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baum S, Ashok A, Gee G, Dimitrova G, Querbes W, Jordan J, Atwood WJ (2003) Early events in the life cycle of JC virus as potential therapeutic targets for the treatment of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J. Neurovirol 9, 32–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berger JR. Classifying PML risk with disease modifying therapies. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2017. February; 12:59–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berger JR, Chauhan A, Galey D, Nath A (2001) Epidemiological evidence and molecular basis of interactions between HIV and JC virus. J. Neurovirol 7:329–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berger JR, Miller CS, Mootoor Y, Avdiushko SA, Kryscio RJ, Zhu H (2006) JC virus detection in bodily fluids: clues to transmission. Clin. Infect. Dis 43, 9–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bollag B, Prins C, Snyder EL, Frisque RJ (2000) Purified JC virus T and T’ proteins differentially interact with the retinoblastoma family of tumor suppressor proteins. Virology 274:165–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bowen L, Nath A, Smith B. CNS immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. Handb Clin Neurol. 2018;152:167–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brooks BR, Walker DL. (1984) Progressive multifocal encephalopathy. Neurol Clin 2, 299–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bullock PA, Seo YS, Hurwitz J (1991) Initiation of simian virus 40 DNA synthesis in vitro. Mol. Cell. Biol 11:2350–2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carter CC, Onafuwa-Nuga A, McNamara LA, Riddell J 4th, Bixby D, Savona MR, Collins KL. (2010). HIV-1 infects multipotent progenitor cells causing cell death and establishing latent cellular reservoirs. Nat. Med 16: 446–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cavanaugh JB, Greenbaum D, Marchall A, Rubinstein L. (1959) Cerebral demyelination associated with disorder of thereticuloendothelial system. LancetII, 524–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen NN, Kerr D, Chang CF, Honjo T, Khalili K (1997). Evidence for regulation of transcription and replication of the human neurotropic virus JCV genome by the human S(mu)bp-2 protein in glial cells. Gene 185:55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen. NN, Change CF, Gallia GL, Kerr DA, Johnson EM, Krachmarov CP, Barr SM, Frisque RJ, Bollag B, Khalili K (1995) Cooperative action of cellular proteins YB-1 and Pur alpha with the tumor antigen of the human JC polyomavirus determines their interaction with the viral lytic control element. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92: 1087–1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gheuens S, Bord E, Kesari S, et al. Role of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses against JC virus in the outcome of patients with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) and PML with immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. J Virol. 2011. ;85(14):7256–7263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chowdhury M, Taylor JP, Tada H, Rappaport J, Wong-Staal F, Amini S, Khalili K. (1990). Regulation of the human neurotropic virus promoter by JCV-T antigen and HIV-1 tat protein. Oncogene 5:1737–1742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chowdhury M, Kundu M, Khalili K (1993) GA/GC-rich sequence confers Tat responsiveness to human neurotropic virus promoter, JCVL, in cells derived from central nervous system. Oncogene 8:887–892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chowdhury M, Taylor JP, Chang CF, Rappaport J, Khalili K (1992) Evidence that a sequence similar to TAR is important for induction of the JC virus late promoter by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat. J. Virol 66:7355–7361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christensen E, Fog M (1955) A case of Schilder’s disease in an adult with remarks to etiology and pathogenesis. Acta Psychiatr. Neurol. Scand. 30, 141–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cinque P, Vago L, Dahl H, et al. (1996) Polymerase chain reaction on cerebrospinal fluid for diagnosis of virus-associated opportunistic diseases of the central nervous system in HIV-infected patients. Aids 10, 951–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Craigie M, Regan P, Otalora YL, Sariyer IK (2015) Molecular interplay between T-antigen and splicing factor, arginine/serine-rich 1 (SRSF1) controls JC virus gene expression in glial cells. Virol J. 2015 November 24; 12:196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Craigie M, Cicalese S, Sariyer IK. Neuroimmune Regulation of JC Virus by Intracellular and Extracellular Agnoprotein. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2018. June;13(2):126–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cortese I, Muranski P, Enose-Akahata Y, et al. Pembrolizu-mab treatment for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. N Engl J Med 2019;380:1597–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daniel DC, Kinoshita Y, Khan MA, Del Valle L, Khalili K, Rappaport J, Johnson EM. (2004) Internalization of exogenous human immunodeficiency virus-1 protein, Tat, by KG-1 oligodendroglioma cells followed by stimulation of DNA replication initiated at the JC virus origin. DNA Cell Biol. 23:858–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Del Valle L, Baehring J, Lorenzana C, Giordano A, Khalili K, Croul S. (2001). Expression of a human polyomavirus oncoprotein and tumour suppressor proteins in medulloblastomas. Mol. Pathol 54:331–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.D’Souza A, Wilson J, Mukherjee S, Jaiyesimi I. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a report of three cases and review of the literature. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2010. February;10(1):E1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dugan AS, Gasparovic ML, Atwood WJ (2008) Direct correlation between sialic acid binding and infection of cells by two human polyomaviruses (JC virus and BK virus). J. Virol. 82, 2560–2564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elphick GF, Querbes W, Jordan JA, Gee GV, Eash S, Manley K, Dugan A, Stanifer M, Bhatnagar A, Kroeze WK, Roth BL, Atwood WJ (2004) The human polyomavirus, JCV, uses serotonin receptors to infect cells. Science 19, 1380–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Enam S, Sweet TM, Amini S, Khalili K, Del Valle L (2004) Evidence for involvement of transforming growth factor betal signaling pathway in activation of JC virus in human immunodeficiency virus 1-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med 128:282–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Engel S, Herger T, Mancini R, Herzog F, Kartenbeck J, Hayer A, Helenius A (2011) Role of endosomes in simian virus 40 entry and infection. J. Virol. 85, 4198–4211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Engelhardt B, Kappos L (2008) Natalizumab: targeting alpha4-integrins in multiple sclerosis. Neurodegener. Dis. 5, 16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ensoli B, Buonaguro L, Barillari G, Fiorelli V, Gendelman R, Morgan RA, Wingfield P, Gallo RC. (1993) Release, uptake, and effects of extracellular human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat protein on cell growth and viral transactivation. J. Virol 67:277–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fabis-Pedrini MJ, Xu W, Burton J, Carroll WM, Kermode AG. Asymptomatic progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy during natalizumab therapy with treatment. J Clin Neurosci. 2016. March;25:145–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fairman MP, Stillman B (1988) Cellular factors required for multiple stages of SV40 DNA replication in vitro. EMBO J. 7:1211–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Felli V, Di Sibio A, Anselmi M, Gennarelli A, Sucapane P, Splendiani A, Catalucci A, Marini C, Gallucci M. Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy Following Treatment with Rituximab in an FIIV-Negative Patient with Non-Flodgkin Lymphoma. A Case Report and Literature Review. Neuroradiol J. 2014. December;27(6):657–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferenczy MW, Marshall LJ, Nelson CDS, Atwood WJ, Nath A, Khalili K, Major EO (2012) Molecular biology, epidemiology, and pathogenesis of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, the JC virus-induced demyelinating disease of the human brain. Clin. Microb. Rev. 25, 471–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fleischmann RM. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy following rituximab treatment in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009. November;60(11 ):3225–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fournier A, Martin-Blondel G, Lechapt-Zalcman E, Dina J, Kazemi A, Verdon R, Mortier E, de La Blanchardiere A. Immune Reconstitution inflammatory Syndrome Unmasking or worsening AiDS-Related Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy: A Literature Review. Front Immunol. 2017. May 23;8:577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Freim Wahl SG, Folvik MR, Torp SH. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a lymphoma patient with complete remission after treatment with cytostatics and rituximab: case report and review of the literature. Clin Neuropathol. 2007, Mar-Apr;26(2):68–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frisque RJ (1983) Regulatory sequences and virus-cell interactions of JC virus. Prog. Clin. Biol. Res 105:41–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gadzia J, Turner J. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in two psoriasis patients treated with efalizumab. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010. August;9(8):1005–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gagne Brosseau MS, Stobbe G, Wundes A. Natalizumab-related PML 2 weeks after negative anti-JCV antibody assay. Neurology. 2016. February 2;86(5):484–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ge H, Manley JL (1990) A protein factor, ASF, controls cell-specific alternative splicing of SV40 early pre-mRNA in vitro. Cell 13, 25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gheuens S, Smith DR, Wang X, Alsop DC, Lenkinski RE, Koralnik IJ. Simultaneous PML-IRIS after discontinuation of natalizumab in a patient with MS. Neurology. 2012. May 1 ;78(18): 1390–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hallervorden J, (1930) Eigennartige und nicht rubizierbare Prozesse, p 1063–1107. In Bumke O (ed), Flandbuch der Geiteskranhetinen Springer, Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Havla J, Berthele A, Kümpfel T, Krumbholz M, Jochim A, Kronsbein H, Ryschkewitsch C, Jensen P, Lippmann K, Flemmer B, Major E, Hohlfeld R. Cooccurrence of two cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a natalizumab “infusion group”. Mult Scler. 2013. August; 19(9): 1213–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Himedan M, Camelo-Piragua S, Mills EA, Gupta A, Aburashed R, Mao-Draayer Y. Pathologic Findings of Chronic PML-IRIS in a Patient with Prolonged PML Survival Following Natalizumab Treatment. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2017. September 27;5(3):2324709617734248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Houff SA, Berger JR (2008) The bone marrow, B cells, and JC virus. J. Neurovirol 14:341–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Houff SA, Major EO, Katz DA, Kufta CV, Sever JL, Pittaluga S, Roberts JR, Gitt J, Saini N, Lux W (1988) Involvement of JC virus-infected mononuclear cells from the bone marrow and spleen in the pathogenesis of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. N Engl J Med 318, 301–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ikegaya H, Iwase H (2004) Trial for the geographical identification using JC viral genotyping in Japan. Forensic Sci. Int 139:169–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Isidoro L, Pires P, Rito L, Cordeiro G. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia treated with alemtuzumab. BMJ Case Rep. 2014. January 8;2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jing D, Oelschlaegel U, Ordemann R, Holig K, Ehninger G, Reichmann H, Ziemssen T, Bornhauser M. (2010). CD49d blockade by natalizumab in patients with multiple sclerosis affects steady-state hematopoiesis and mobilizes progenitors with a distinct phenotype and function. Bone Marrow Transplant. 45:1489–1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kerr D, Chang CF, Chen N, Gallia G, Raj G, Schwartz B, Khalili K. (1994) Transcription of a human neurotropic virus promoter in glial cells: effect of YB-1 on expression of the JC virus late gene. J. Virol 68:7637–7643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Knowles WA, Pipkin P, Andrews N, Vyse A, Minor P, Brown DW, Miller E (2003) Population-based study of antibody to the human polyomaviruses BKV and JCV and the simian polyomavirus SV40. J. Med. Virol. 71, 115–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Koralnik I J, Can Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors Keep JC Virus in Check? N Engl J Med. 2019. April 25;380(17):1667–1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kothary N, Diak IL, Brinker A, Bezabeh S, Avigan M, Dal Pan G. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy associated with efalizumab use in psoriasis patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011. September;65(3):546–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Krumbholz M, Meinl I, Kumpfel T, Hohlfeld R, Meinl E (2008) Natalizumab disproportionately increases circulating pre-B and B cells in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 71:1350–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kumar D, Bouldin TW, Berger RG. A case of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient treated with infliximab. Arthritis Rheum. 2010. November;62(11 ):3191–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Langer-Gould A, Atlas SW, Green AJ, Bollen AW, Pelletier D. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient treated with natalizumab. N Engl J Med. 2005. July 28;353(4):375–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lebwohl M, Tyring SK, Hamilton TK, Toth D, Glazer S, Tawfik NH, Walicke P, Dummer W, Wang X, Garovoy MR, Pariser D; Efalizumab Study Group. (2003) A novel targeted T-cell modulator, efalizumab, for plaque psoriasis. N. Engl. J. Med 349:2004–2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lee SH, Hurwitz J (1990) Mechanism of elongation of primed DNA by DNA polymerase delta, proliferating cell nuclear antigen, and activator 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 87:5672–5676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lindå H, von Heijne A, Major EO, Ryschkewitsch C, Berg J, Olsson T, Martin C. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy after natalizumab monotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2009. September 10;361 (11 ):1081–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lindberg RL, Achtnichts L, Hoffmann F, Kuhle J, Kappos L (2008) Natalizumab alters transcriptional expression profiles of blood cell subpopulations of multiple sclerosis patients. J. Neuroimmunol 194:153–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lipsky JJ (1996) Mycophenolate mofetil. Lancet 348:1357–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu CK, Wei G, Atwood WJ (1998) Infection of glial cells by the human polyomavirus JC is mediated by N-linked glycoprotein containing terminal alpha (2–6)-linked sialic acids. J Virol. 72, 4643–4649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Maginnis MS, Haley SA, Gee GV, Atwood WJ (2010) Role of N-linked glycosylation of the 5-HT2A receptor in JC virus infection. J. Virol. 84, 9677–9684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Major EO (2010) Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in patients on immunomodulatory therapies. Annu. Rev. Med. 61, 35–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Major EO, Amemiya K, Elder G, Houff SA (1990) Glial cells of the human developing brain and B cells of the immune system share a common DNA binding factor for recognition of the regulatory sequences of the human polyomavirus, JCV. J. Neurosci. Res. 27, 461–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Major EO, Amemiya K, Elder G, Tornatore CS, Houff SA, Berger JR (1992) Pathogenesis and molecular biology of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, the JC-virus induced demyelinating disease of the human brain. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 5, 49–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Major EO, Neel JV (1998) The JC and BK human polyoma viruses appear to be recent introductions to some South American Indian tribes: there is no serological evidence of cross-reactivity with the simian polyoma virus SV40. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 15525–15530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Marshall LJ, Dunham L, Major EO (2010) Transcription factor Spi-B binds unique sequences present in the tandem repeat promoter/ enhancer of JC virus and supports viral activity. J. Gen. Virol 91:3042–3052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Martin-Blondel G, Bauer J, Cuvinciuc V, Uro-Coste E, Debard A, Massip P, Delisle MB, Lassmann H, Marchou B, Mars LT, Liblau RS. In situ evidence of JC virus control by CD8+ T cells in PML–IRIS during HIV infection. Neurology. 2013. September 10;81 (11 ):964–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Martin-Blondel G, Bauer J, Uro-Coste E, Biotti D, Averseng-Peaureaux D, Fabre N, Dumas H, Bonneville F, Lassmann H, Marchou B, Liblau RS, Brassat D. Therapeutic use of CCR5 antagonists is supported by strong expression of CCR5 on CD8(+) T cells in progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy-associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. Acta Neuropathol. 2015. March;129(3):463–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mázló M, Tariska I (1982) Are astrocytes infected in progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy? Acta. Neuropathol. 56, 45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McLaughlin P, Grillo-López AJ, Link BK, Levy R, Czuczman MS, Williams ME, Heyman MR, Bence-Bruckler I, White CA, Cabanillas F, Jain V, Ho AD, Lister J, Wey K, Shen D, Dallaire BK. (1998) Rituximab chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy for relapsed indolent lymphoma: half of patients respond to a four-dose treatment program. J. Clin. Oncol 16:2825–2833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Monaco MC, Atwood WJ, Gravell M, Tornatore CS, Major EO (1996). JC virus infection of hematopoietic progenitor cells, primary B lymphocytes, and tonsillar stromal cells: implications for viral latency. J Virol. 70, 7004–7012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Müller M, Wandel S, Colebunders R, Attia S, Furrer H, Egger M; leDEA Southern and Central Africa. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in patients starting antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010. April;10(4):251–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nesper J, Smith RW, Kautz AR, Sock E, Wegner M, Grummt F, Nasheuer HP. (1997) A cell-free replication system for human polyomavirus JC DNA. J. Virol 71:7421–7428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Neu U, Maginnis M, Palma A, Ströh LJ, Nelson CDS, Feizi T, Atwood WJ, Stehle T (2011) Structure-function analysis of the human JC polyomavirus establishes the LSTc pentasaccharide as a functional receptor motif. Cell Host Microb. 8, 309–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nukuzuma S, et al. 2010. Efficient propagation of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy-type JC virus in COS-7-derived cell lines stably expressing Tat protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Microbiol. Immunol 54:758–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Okada Y., Endo S, Takahashi H, Sawa H, Umemura T, Nagashima K (2001) Distribution and function of JCV agnoprotein. J Neurovirol 7, 302–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Otlu O, De Simone FI, Otalora YL, Khalili K, Sariyer IK. he agnoprotein of polyomavirus JC is released by infected cells: evidence for its cellular uptake by uninfected neighboring cells. Virology. 2014. November;468–470:88–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Parikh A, Stephens K, Major E, Fox I, Milch C, Sankoh S, Lev MH, Provenzale JM, Shick J, Patti M, McAuliffe M, Berger JR, Clifford DB. A Programme for Risk Assessment and Minimisation of Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy Developed for Vedolizumab Clinical Trials. Drug Saf. 2018. May 8. doi: 10.1007/S40264-018-0669-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Paues J, Vrethem M. Fatal progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient with non-Hodgkin lymphoma treated with rituximab. J Clin Virol. 2010. August;48(4):291–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Petito CK, Cash KS (1992) Blood-brain barrier abnormalities in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: immunohistochemical localization of serum proteins in postmortem brain. Ann. Neurol 32:658–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Phan-Ba R, Lommers E, Tshibanda L, Calay P, Dubois B, Moonen G, Clifford D, Belachew S. MRI preclinical detection and asymptomatic course of a progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy (PML) under natalizumab therapy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012. February;83(2):224–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pho MT, Ashok A, Atwood WJ (2000) JC virus enters human glial cells by clathrin-dependent receptor-mediated endocytosis. J. Virol. 74, 2288–2292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Puri V, Chaundhry N, Gulati P, Patel N, Tatke M, Sinha S (2010) Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient with idiopathic CD4+ T lymphocytopenia. Neurol. India 58, 118–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rauer S, Marks R, Urbach H, et al. Treatment of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy with pembrolizumab. N Engl J Med 2019;380:1676–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Querbes W, Benmerah A, Tosoni D, Di Fiore PP, Atwood WJ (2004) A JC virus-induced signal is required for infection of glial cells by a clarthin- and eps15-dependent pathway. J. Virol. 78, 250–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Querbes W, O’Hara BA, Williams G, Atwood WJ (2006) Invasion of host cells by JC virus identifies a novel role for caveolae in endosomal sorting of noncaveolar ligands. J. Virol. 80, 9402–9413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ranganathan PN, Khalili K (1993) The transcriptional enhancer element, kappa B, regulates promoter activity of the human neurotrophic virus, JCV, in cells derived from the CNS. Nucleic Acids Research 21: 1959–1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ravichandran V, Sabath BF, Jensen PN, Houff SA, Major EO (2006) Interactions between c-Jun, nuclear factor 1, and JC virus promoter sequences: implications for viral tropism. J. Virol 80:10506–10513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Reff ME, Carner K, Chambers KS, Chinn PC, Leonard JE, Raab R, Newman RA, Hanna N, Anderson DR. 1994. Depletion of B cells in vivo by a chimeric mouse human monoclonal antibody to CD20. Blood 83:435–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Rice GP, Hartung HP, Calabresi PA (2005) Anti-alpha4 integrin therapy for multiple sclerosis: mechanisms and rationale. Neurology. 64, 1336–1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Richardson EP Jr., (1961) Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 265, 815–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rudnicka D; Oszmiana A; Finch DK; Strickland I; Schofield DJ; Lowe DC; Sleeman MA; Davis DM (June 6, 2013). “Rituximab causes a polarization of B cells that augments its therapeutic function in NK-cell-mediated antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity.”. Blood. 121 (23): 4694–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sano Y, Nakano Y, Omoto M, Takao M, Ikeda E, Oga A, Nakamichi K, Saijo M, Maoka T, Sano H, Kawai M, Kanda T. Rituximab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy derived from non-Hodgkin lymphoma: neuropathological findings and results of mefloquine treatment. Intern Med. 2015;54(8):965–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Saribas AS, Ozdemir A, Lam C, Safak M (2010) JC virus-induced progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Future Virol. 5, 313–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Saribas AS, White MK, Safak M Structure-based release analysis of the JC virus agnoprotein regions: A role for the hydrophilic surface of the major alpha helix domain in release. J Cell Physiol. 2018. March;233(3):2343–2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sariyer IK, Khalili K (2011) Regulation of human neurotropic JC virus replication by alternative splicing factor SF2/ASF in glial cells. PLoS One. 2011 January 31;6(1):e14630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sariyer R, De-Simone FI, Gordon J, Sariyer IK (2016) Immune suppression of JC virus gene expression is mediated by SRSF1. J Neurovirol. 22:597–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Schwab N, Ulzheimer JC, Fox RJ, Schneider-Hohendorf T, Kieseier BC, Monoranu CM, Staugaitis SM, Welch W, Jilek S, Du Pasquier RA, Brück W, Toyka KV, Ransohoff RM, Wiendl H. Fatal PML associated with efalizumab therapy: insights into integrin αίβ2 in JC virus control. Neurology. 2012. February 14;78(7):458–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Schwab N, Hohn KG, Schneider-Hohendorf T, Metz I, Stenner MP, Jilek S, Du Pasquier RA, Gold R, Meuth SG, Ransohoff RM, Brück W, Wiendl H Immunological and clinical consequences of treating a patient with natalizumab. Mult Scler. 2012. March;18(3):335–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Shivakumar CV, Das GC. 1994. Biochemical and mutational analysis of the polyomavirus core promoter: involvement of nuclear factor-1 in early promoter function. J. Gen. Virol 75:1281–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sierra Morales F, Illingworth C, Lin K, Rivera Agosto I, Powell C, Sloane JA, Koralnik IJ. PML-IRIS in an HIV-2-infected patient presenting as Bell’s palsy. J Neurovirol. 2017. October;23(5):789–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sikkema T, Schuiling WJ, Hoogendoorn M. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy during treatment with rituximab and CHOP chemotherapy in a patient with a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2013. January 25;2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Stettner MR, Nance JA, Wright CA, Kinoshita Y, Kim WK, Morgello S, Rappaport J, Khalili K, Gordon J, Johnson EM. (2009). SMAD proteins of oligodendroglial cells regulate transcription of JC virus early and late genes coordinately with the Tat protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Gen. Virol 90:2005–2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Stoppe M, Thomä E, Liebert UG, Major EO, Hoffmann KT, Claßen J, Then Bergh F. Cerebellar manifestation of PML under fumarate and after efalizumab treatment of psoriasis. J Neurol. 2014. May;261(5):1021–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Suzuki T, Orba Y, Okada Y, Sunden Y, Kimura T, Tanaka S, Nagashima K, Hall WW, Sawa H. The human polyoma JC virus agnoprotein acts as a viroporin. LoS Pathog. 2010. March 12;6(3):e1000801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Tada H, Rappaport J, Lashgari M, Amini S, Wong-Staal F, Khalili K. (1990). Trans-activation of the JC virus late promoter by the tat protein of type 1 human immunodeficiency virus in glial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 87:3479–3483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Tada H, Khalili K (1992) A novel sequence-specific DNA-binding protein, LCP-1, interacts with single-stranded DNA and differentially regulates early gene expression of the human neurotropic JC virus. J. Virol 66:6885–6892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Tavis JE, Trowbridge PW, Frisque RJ (1994) Converting the JCV T antigen Rb binding domain to that of SV40 does not alter JCV’s limited transforming activity but does eliminate viral viability. Virology 199: 384–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Taylor JP, Cupp C, Diaz A, Chowdhury M, Khalili K, Jimenez SA, Amini S. (1992) Activation of expression of genes coding for extracellular matrix proteins in Tat-producing glioblastoma cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 89:9617–9621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Tornatore C, Berger JR, Houff SA, Curfman B, Meyers K, Winfield D, Major EO (1992) Detection of JC virus DNA in peripheral lymphocytes from patients with and without progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Ann. Neurol. 31, 454–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Tsurimoto T, Melendy T, Stillman B (1990) Sequential initiation of lagging and leading strand synthesis by two different polymerase complexes at the SV40 DNA replication origin. Nature 346:534–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Uleri E, Beltrami S, Gordon J, Dolei A, Sariyer IK (2011) Extinction of tumor antigen expression by SF2/ASF in JCV-transformed cells. Genes Cancer. 2:728–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Uphaus T, Oberwittler C, Groppa S, Zipp F, Bittner S. Disease reactivation after switching from natalizumab to daclizumab. J Neurol. 2017. December;264(12):2491–2494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Van Assche G, Van Ranst M, Sciot R, Dubois B, Vermeire S, Noman M, Verbeeck J, Geboes K, Robberecht W, Rutgeerts P. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy after natalizumab therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2005. July 28;353(4):362–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Vendrely A, Bienvenu B, Gasnault J, Theibault JB, Salmon D, Gray F (2005) Fulminant inflammatory leukoencephalopathy associated with HAART-induced immune restoration in AIDS-related progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 109, 449–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Waggoner J, Martinu T, Palmer SM. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy following heightened immunosuppression after lung transplant. J Fleart Lung Transplant. 2009. April;28(4):395–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Warsch S, Hosein PJ, Morris Ml, Teomete U, Benveniste R, Chapman JR, Lossos IS. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy following treatment with bendamustine and rituximab. Int J Hematol. 2012. August;96(2):274–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Wegner M, Drolet DW, Rosenfeld MG (1993) Regulation of JC virus by the POU-domain transcription factor Tst-1: implications for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 90:4743–4747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Weinberg DH, Collins KL, Simancek P, Russo A, Wold MS, Virshup DM, Kelly TJ. (1990) Reconstitution of simian virus 40 DNA replication with purified proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 87:8692–8696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.White MK, Khalili K (2006) Interaction of retinoblastoma protein family members with large T-antigen of primate polyomaviruses. Oncogene 25:5286–5293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Wiley CA, Grafe M, Kennedy C, Nelson JA (1988) Human immunodeficiency virus and JC virus in acquired immune deficiency syndrome patients with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 76, 338–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Windpessl M, Burgstaller S, Kronbichler A, Pieringer H, Kalev O, Karrer A, Wallner M, Thaler J. Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy Following Combined Rituximab-Based Immune-Chemotherapy for Post-transplant Lymphoproliferative Disorder in a Renal Transplant Recipient: A Case Report. Transplant Proc. 2018. April;50(3):881–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Winkleman NW, Moore MT (1941) Lymphogranulomatosis (Hodgkin’s disease) of the nervous system. Arch. Neurol. Psychol. 45, 304–318. [Google Scholar]

- 135.Wüthrich C, Kesari S, Kim WK, Williams K, Gelman R, Elmeric D, De Girolami U, Joseph JT, Hedley-Whyte T, Koralnik IJ (2006) Characterization of lymphocytic infiltrate in progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: co-localization of CD8(+) T cells with JCV-infected glial cells. J. Neurovirol. 12, 116–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Yadav A, Collman RG (2009) CNS inflammation and macrophage/microglial biology associated with HIV-1 infection. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 4, 430–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Yokoyama H, Watanabe T, Maruyama D, Kim SW, Kobayashi Y, Tobinai K. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in a patient with B-cell lymphoma during rituximab-containing chemotherapy: case report and review of the literature. Int J Hematol. 2008. November;88(4):443–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]