Abstract

The HIV-1 envelope (Env) glycoprotein, a (gp120-gp41)3 trimer, mediates fusion of viral and host cell membranes after gp120 binding to host receptor CD4. Receptor binding triggers conformational changes allowing coreceptor (CCR5) recognition through CCR5’s tyrosine-sulfated N-terminus, release of the gp41 fusion peptide, and fusion. We present 3.3Å and 3.5Å cryo-EM structures of E51, a tyrosine-sulfated coreceptor-mimicking antibody, complexed with a CD4-bound open HIV-1 native-like Env trimer. Two classes of asymmetric Env interact with E51, revealing tyrosine-sulfated interactions with gp120 mimicking CCR5 interactions, and two conformations of gp120-gp41 protomers (A and B protomers in AAB and ABB trimers) that differ in their degree of CD4-induced trimer opening and induction of changes to the fusion peptide. By integrating the new structural information with previous closed and open envelope trimer structures, we modeled the order of conformational changes on the path to coreceptor binding site exposure and subsequent viral–host cell membrane fusion.

Introduction

The HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein (Env), a homotrimer of gp120-gp41 heterodimers, mediates fusion of the host and viral membrane bilayers to allow entry of the HIV-1 capsid containing viral RNA into the host cell cytoplasm1. The fusion process is initiated by interactions between the Env gp120 subunit and the host receptor CD4, resulting in conformational changes that reveal the binding site for a host coreceptor, the CCR5 or CXCR4 chemokine receptor2,3. Coreceptor binding facilitates further changes leading to insertion of the gp41 fusion peptide into the host cell membrane and subsequent fusion1. Conformational changes induced by CD4 binding to trimeric HIV-1 Env have been characterized by cryo-electron tomography of virion-bound Envs4 and higher resolution single-particle cryo-EM structures of soluble, native-like Env trimers lacking membrane and cytoplasmic domains and including stabilizing mutations (SOSIP Envs)5–7. Mutations introduced into soluble SOSIP Env trimers (‘SOS’ mutations A501Cgp120, T605Cgp41 and the ‘IP’ mutation I559Pgp41)8 prevent HIV-1 infection when introduced into virion-bound Envs9, as expected since the substitutions were designed to stabilize the prefusion Env conformation8. However, SOSIP Env structures can undergo conformational changes upon binding to CD4; thus SOSIP structures have defined a closed, pre-fusion Env state in which the g120 V1V2 loops shield the coreceptor binding site on V3 and an open CD4-bound trimeric state with outwardly rotated gp120 subunits and V1V2 loops displaced by ~40Å to expose the V3 loops and coreceptor binding site5–7,10 (Supplementary Video). Both the closed and open CD4-bound states are consistent with the structures of native virion-bound Envs derived by cryo-electron tomography and sub-tomogram averaging4.

As the only viral protein on the surface of HIV-1 virions, HIV-1 Env is the target of host antibodies whose epitopes have been mapped onto structures of Env glycoprotein trimers11. One class of antibodies, the CD4-induced (CD4i) antibodies, recognizes conserved regions of gp120 at or near the coreceptor binding site that are exposed by conformational changes caused by CD4 binding12. These antibodies are often cross-reactive but not very potent13–16, perhaps related to limited steric accessibility when Env on the viral membrane is complexed with CD4 on the target cell17. CD4i antibodies were initially characterized structurally as complexes with monomeric gp120 cores (gp120 constructs with truncations in the N- and C-termini, V1V2, and V3), as exemplified by the first gp120 crystal structure in which CD4i antibody 17b and soluble CD4 (sCD4) were complexed with a gp120 core18. The CD4i epitope on monomeric gp120 cores comprises the base of the V3 loop and the bridging sheet (a four-stranded anti-parallel β-sheet involving the gp120 β20 and β21 strands preceding the V5 loop and the β2 and β3 strands at the base of V1V2). Confirming that the coreceptor binding site on gp120 also involves the bridging sheet and V3, a cryo-EM structure of a sCD4-bound full-length monomeric gp120 complexed with CCR5 showed interactions of the CCR5 N-terminal residues with the four-stranded bridging sheet and insertion of gp120 V3 loop into the chemokine binding pocket formed by the CCR5 transmembrane helices19. The structure also revealed contacts of N-terminal O-sulfated tyrosines on CCR5 that enhance viral entry (Tys10CCR5 and Tys14CCR5)20 with residues at the base of gp120 V319.

CD4i antibodies mimic host coreceptors by requiring conformational changes within Env trimers for binding. In addition, some CD4i antibodies; e.g., the E51 and 412d antibodies that were isolated from the same HIV-1–infected donor21,22, mimic N-terminal residues of CCR5 by including sulfotyrosines in their heavy chain complementarity determining region 3 (CDRH3) regions20,23. Current structures of CD4i antibodies bound to sCD4-bound Env trimers are limited to complexes with 17b and 21c5,7, antibodies that do not include tyrosine-sulfated CDRH3 regions. Here we present 3.3 Å and 3.5 Å resolution cryo-EM structures of E51, the more potent of the pair of tyrosine-sulfated CD4i antibodies21–23, bound to open sCD4-SOSIP Env trimer complexes, allowing comparisons of sulfated tyrosine recognition by a CD4i antibody and by CCR5. Both E51-sCD4-Env structures exhibit deviations from 3-fold Env symmetry in the degree to which the three gp120-gp41 protomers open in response to sCD4 binding and in the extent of sCD4- and Fab-induced structural changes relayed to gp41 and the fusion peptide. Together with comparisons with previous structures, including complexes of CCR5-sCD4-monomeric gp12019, CD4i-sCD4-Env trimers5,7, and CD4i-sCD4-monomeric gp12024,25, the new structures define structural effects of CDRH3 tyrosine sulfation, illustrate the potential for Env trimer asymmetry, and facilitate understanding of conformational changes leading to Env-mediated fusion of viral and host cell membranes.

Results

Cryo-EM Structures of Env trimer in complex with sCD4 and E51 Fab

We previously described structures of clade A BG505 and clade B B41 native-like soluble Env trimers (SOSIP.664 trimers8) complexed with sCD4, the CD4i antibodies 17b or 21c, and the gp120-gp41 interface antibody 8ANC1956,7. We observed conformational changes, including rotation and displacement of gp120 subunits, displacement of the gp120 V1V2 region from the apex to the sides of the trimer, exposure of V3, and a more compact conformation of the gp41 HR1C helices. As defined by measurements between 3-fold symmetry-related residues in gp120 that were outwardly displaced in response to sCD4 binding7, we described the trimers in the 17b-sCD4-Env-8ANC195 and 21c-sCD4-Env-8ANC195 complexes as partially open, as compared with the fully-open Env conformation in a 17b-sCD4-B41 complex5, concluding that 8ANC195 binding induced partial closure of open sCD4-bound Env trimers7,26.

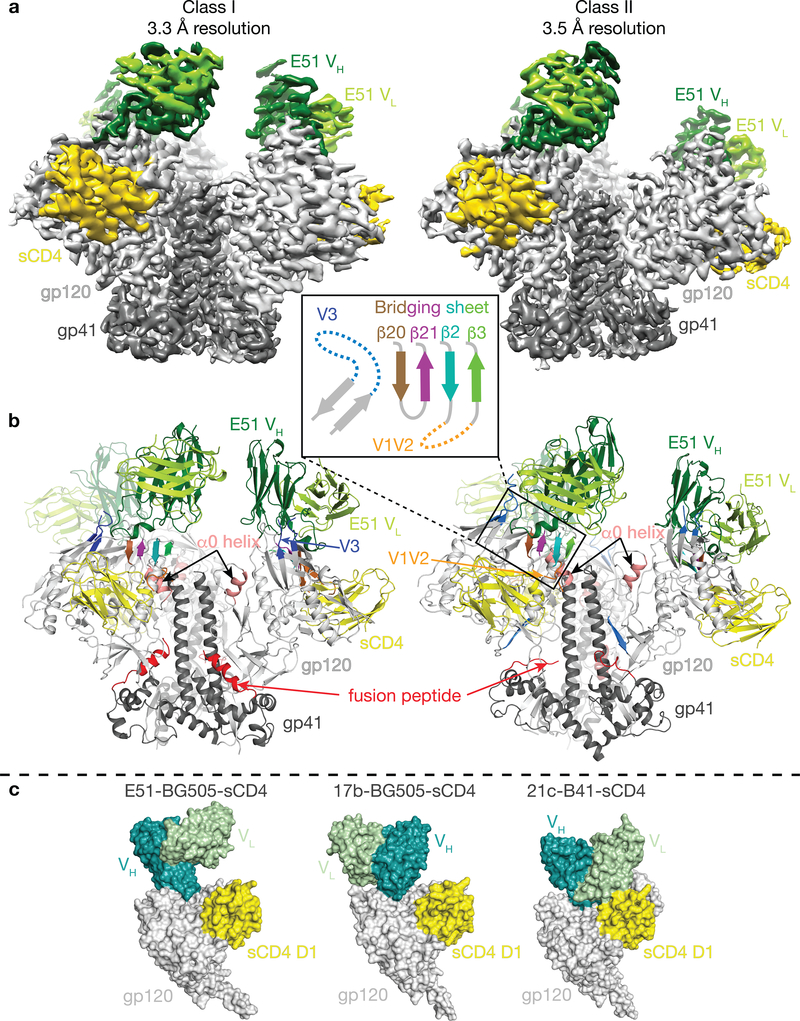

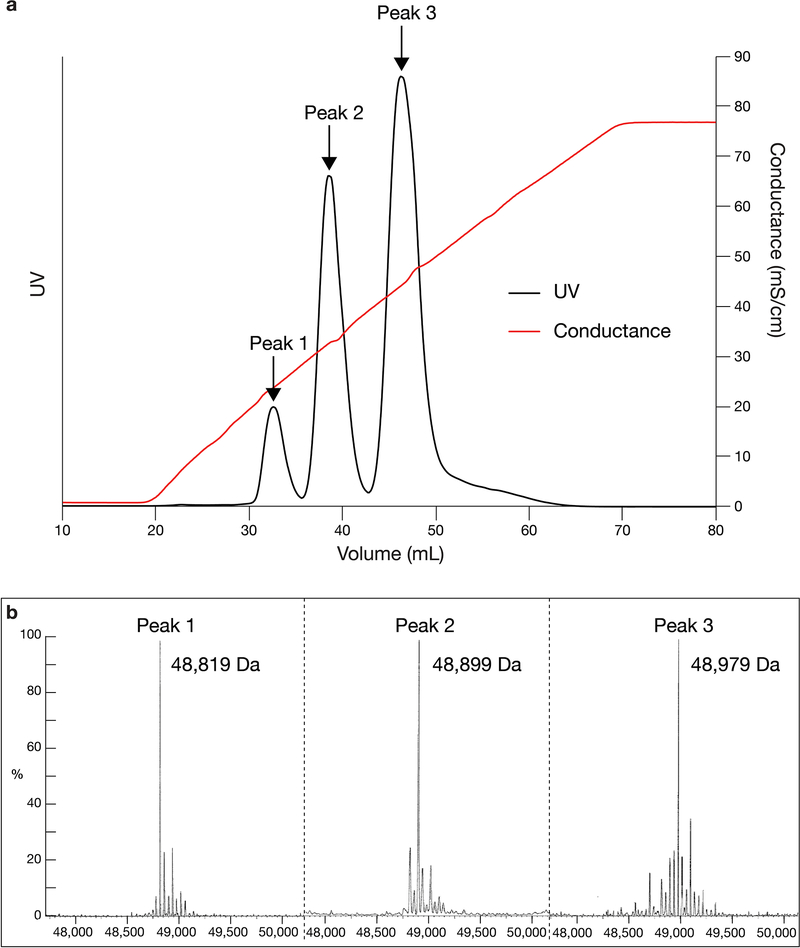

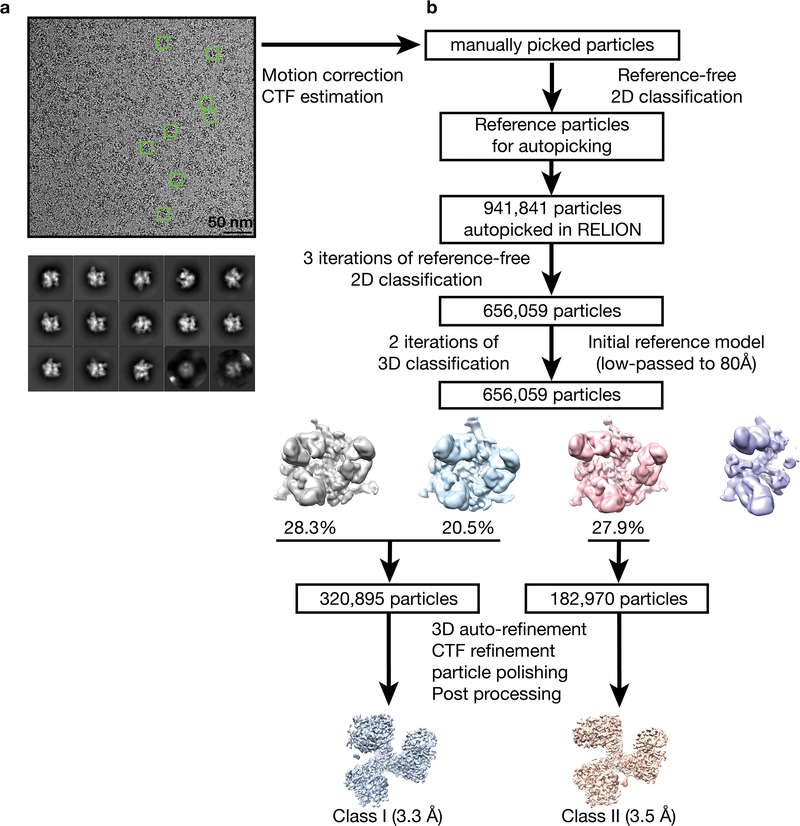

In this study, we prepared fully-open sCD4-bound BG505 SOSIP.664 Env trimer and used cryo-EM to investigate the structural details of sulfotyrosine interactions with the exposed coreceptor binding site in an E51-sCD4-BG505 complex. E51 Fab, BG505 SOSIP, and sCD4 domains 1 and 2 were expressed and purified as described7 with modifications for E51 including co-expression with tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase II (TPST II)27 and isolation of tyrosine-sulfated Fab (Extended Data 1a). Mass spectrometric analyses revealed up to two sulfated tyrosines within the E51 Fab (Extended Data 1b). Single-particle cryo-EM structures were solved using complexes containing E51 Fab with two sulfotyrosines to resolutions of 3.3 Å and 3.5 Å for two conformational classes of the E51-sCD4-BG505 complex (denoted here as class I and class II) (Table 1, Extended Data 2,3). Both structures involved an asymmetric Env trimer complexed with three sCD4s and three E51 Fabs (Fig. 1a,b). Each of the three gp120-gp41 protomers exhibited outwardly rotated gp120 subunits compared to closed Env trimers, a largely disordered and exposed V3 loop, a displaced V1V2 region, and a four-stranded gp120 bridging sheet (Fig. 1b; Supplementary Video). The E51 Fab epitope on gp120 overlaps with the epitopes for the CD4i antibodies 17b and 21c (Fig. 1c). Consistent with mass spectrometric identification of sulfated tyrosines in E51 Fab (Extended Data 1b), we found density for two sulfated tyrosines within the E51 CDRH3 (Extended Data 4). While Tys100IE51 HC showed clear density for both the aromatic ring and sulfate group, the density for Tys100FE51 HC was weaker (Extended Data 4a).

Table 1.

Cryo-EM data collection, refinement, and validation statistics

| BG505 SOSIP-sCD4-E51 Class I (EMDB-20605; PDB 6U0L) |

BG505 SOSIP-sCD4-E51 Class II (EMDB-20608; PDB 6U0N) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Data collection and processing | ||

| Magnification (nominal) | 130,000x | 130,000x |

| Voltage (kV) | 300 | 300 |

| Electron exposure (e−/Å2) | 64 | 64 |

| Defocus range (μm) | 1 – 2.8 | 1 – 2.8 |

| Pixel size (Å) | 1.057 | 1.057 |

| Symmetry imposed | C1 | C1 |

| Initial particle images (no.) | 941,841 | 941,841 |

| Final particle images (no.) | 320,895 | 182,970 |

| Map resolution (Å) | 3.31 | 3.49 |

| FSC threshold | 0.143 | 0.143 |

| Map resolution range (Å) | 3.3 – 5.2 | 3.5 – 5.2 |

| Refinement | ||

| Initial model used (PDB code) | 6CM3 (partial*) | 6CM3 (partial*) |

| Model resolution (Å) | ||

| FSC threshold - 0.143 | 3.2 | 3.3 |

| Model resolution range (Å) | 3.2 – 5.2 | 3.3 – 5.2 |

| Map sharpening B factor (Å2) | −90 | −80 |

| Model composition | ||

| Non-hydrogen atoms | 19,624 | 19,322 |

| Protein residues | 2502 | 2489 |

| Ligands | NAG: 35 | NAG: 34 |

| BMA: 3 | BMA: 3 | |

| MAN: 8 | MAN: 6 | |

| B factors (Å2) | ||

| Protein | 68 | 84 |

| Ligand | 69 | 87 |

| R.m.s. deviations | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.009 | 0.006 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.025 | 0.914 |

| Validation | ||

| MolProbity score | 2.17 | 1.84 |

| Clashscore | 6.01 | 5.68 |

| Poor rotamers (%) | 1.0 | 0.35 |

| Ramachandran plot | ||

| Favored (%) | 90.6 | 90.5 |

| Allowed (%) | 9.4 | 9.5 |

| Disallowed (%) | 0 | 0 |

Used coordinates of trimeric gp120-gp41 as the reference model

Figure 1. The Env protomers in E51-sCD4-BG505 complexes adopt two distinct conformations.

a, Cryo-EM density maps of class I and class II E51-sCD4-BG505 structures. b, Cartoon representations of Envs from the two structural classes. Inset shows a topology diagram for the four-stranded bridging sheet and the exposed V3 loop (mostly disordered) that comprise part of the E51 epitope on gp120. c, Surface representations comparing CD4i Fabs (E51, 17b, and 21c) bound to the gp120-sCD4 portions of CD4i-sCD4-Env trimer complex structures (PDBs 6CM3 and 6EDU for the 17b and 21c complex structures, respectively).

Sulfotyrosines on E51 recognize conserved positive patches on gp120

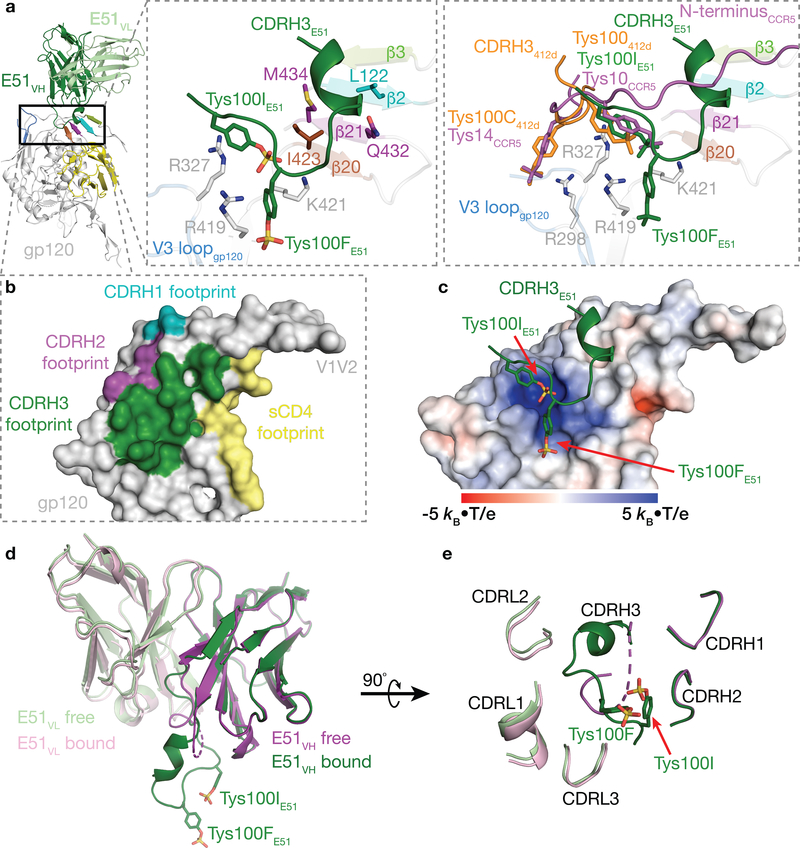

In common with the epitopes of CCR5 and the CD4i antibodies such as 17b and 21c, the E51 epitope on gp120 involves the base of V3 and residues within the four-stranded β20-β21-β2-β3 bridging sheet (Fig. 2), and like 17b and 21c, E51 also contacts the CD4-binding site loop (Supplementary Note 1). E51 Fab contacts gp120 with all three CDRs of its heavy chain, but its light chain does not participate in gp120 recognition (Fig. 2a,b). Contacts between the E51 heavy chain and gp120 could be divided into two categories: (i) CDRH1 and CDRH2 contacts with gp120 bridging sheet residues and CDRH3 stacking on top of the bridging sheet (Fig. 2a,b), and (ii) interactions between CDRH3 sulfotyrosines and positively-charged gp120 residues (Fig. 2c).

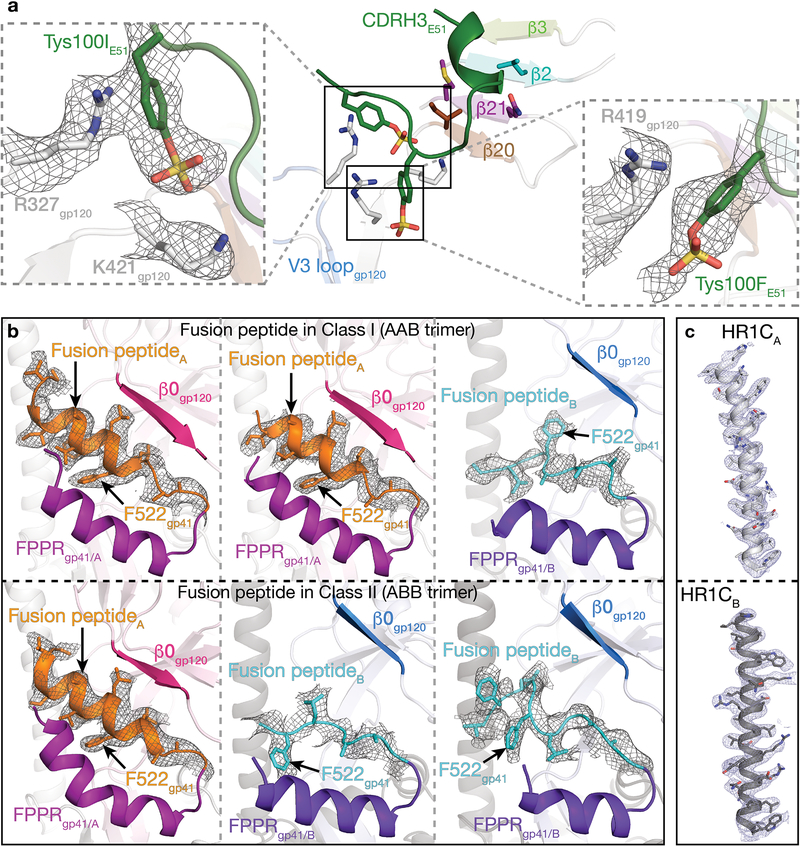

Figure 2. E51 Fab interacts extensively with gp120.

a, Cartoon representation of E51-gp120 portion of E51-sCD4-BG505 structure (left). Middle inset shows a close-up with the four-stranded bridging sheet (colors as shown in Fig. 1b) and interface residues shown as sticks. Right inset shows a superimposition of regions containing sulfated tyrosines in structures of E51-sCD4-BG505, CCR5-sCD4-gp120 (PDB 6MEO), and 412d-sCD4-gp120 (PDB 2QAD) complexes. b, Surface representation of gp120 with contacts by E51 CDRs and sCD4 highlighted. c, Electrostatic surface of gp120 overlaid with CDRH3 of bound E51. Sulfated tyrosines highlighted as sticks. d, Superimposition of VH-VL domains of bound and free E51 (PDB 1RZF)22. Ordered sulfated tyrosines are highlighted as sticks on the CDRH3 of the bound E51 Fab structure. A dashed line for the CDRH3 in the free structure indicates a disordered region. e, E51 combining site (90° rotation from orientation in panel d) with ordered sulfated tyrosines highlighted as sticks.

The E51 CDRH3 sulfotyrosines, Tys100IE51 HC and Tys100FE51 HC, play prominent roles in E51’s interface with gp120 (Fig. 2a). The aromatic ring of E51 Tys100IE51 HC is stacked above the guanidinium group of Arg327gp120 (base of the V3 loop) through a cation-π interaction, while the sulfate group interacts electrostatically with Lys421gp120, which is N-terminal to the β20 strand of the bridging sheet (Fig. 2a). Tys100FE51 HC interacts electrostatically with Arg419gp120 and is in the vicinity of Lys421gp120, with which it could interact with a cation-π interaction. The E51 sulfotyrosine interactions can be compared with interactions of monomeric gp120 with sulfated tyrosines within the N-terminal loop of CCR5 and in the CD4i antibody 412d, as visualized in structures of CCR5-sCD4-gp120monomer19 and 412d-sCD4-gp120monomer25 complexes. Superimposition of the gp120 portions of the E51-sCD4-BG505, CCR5-sCD4-gp120, and 412d-sCD4-gp120 complexes showed that a CCR5 sulfated tyrosine that is required for binding to gp120-sCD4 complexes and for inhibition of viral entry into host cells28 (Tys10CCR5) was oriented similarly with respect to gp120 as Tys100IE51 HC and made analogous interactions. These interactions were also shared with the orientation and interactions of Tys100412d, a sulfated tyrosine in the 412d Fab25 (Fig. 2a). The 412d antibody included another sulfated tyrosine, Tys100C412d, which mimicked the interactions of another required CCR5 sulfated tyrosine, Tys14CCR5 (Fig. 2a).

To further characterize E51 recognition of sCD4-bound Env, we compared the structures of the variable domains of free E51 (PDB 1RZF)22 and E51 complexed with Env trimer (this study). The E51 VL domain showed no major structural changes between bound and free forms (root mean square deviation, r.m.s.d., for superimposition of 112 VL Cα atoms = 0.4 Å) (Fig. 2d,e), consistent with no VL contacts in E51 with gp120. By contrast, the E51 VH domain buried 723 Å2 at the interface with gp120. Major changes between the free and bound E51 VH domains involved the CDRH3 loop, which was largely disordered in free E51 Fab (12 disordered residues spanning Gly99E51 HC–Asp100JE51 HC, which included two sulfated tyrosines22), but adopted an ordered conformation stabilized by contacts with gp120 in bound E51 (Fig. 2d,e) (r.m.s.d. = 1.0 Å calculated for 121 ordered Cα residues in bound versus free E51 VH). The ordered CDRH3 conformation in bound E51 Fab included 1.5 turns of α-helix (residues Ala98E51 HC–Ala100CE51 HC) followed by the two sulfated tyrosines (Tys100FE51 HC and Tys100IE51 HC) (Fig. 2d).

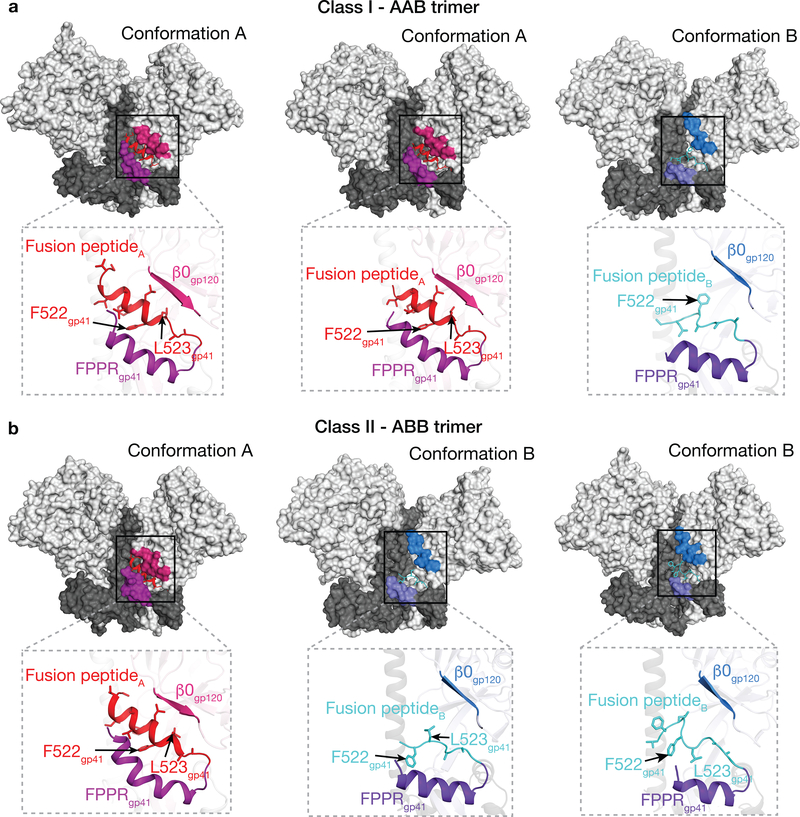

BG505 Env trimer adopts two distinct sCD4-bound open states when complexed with E51

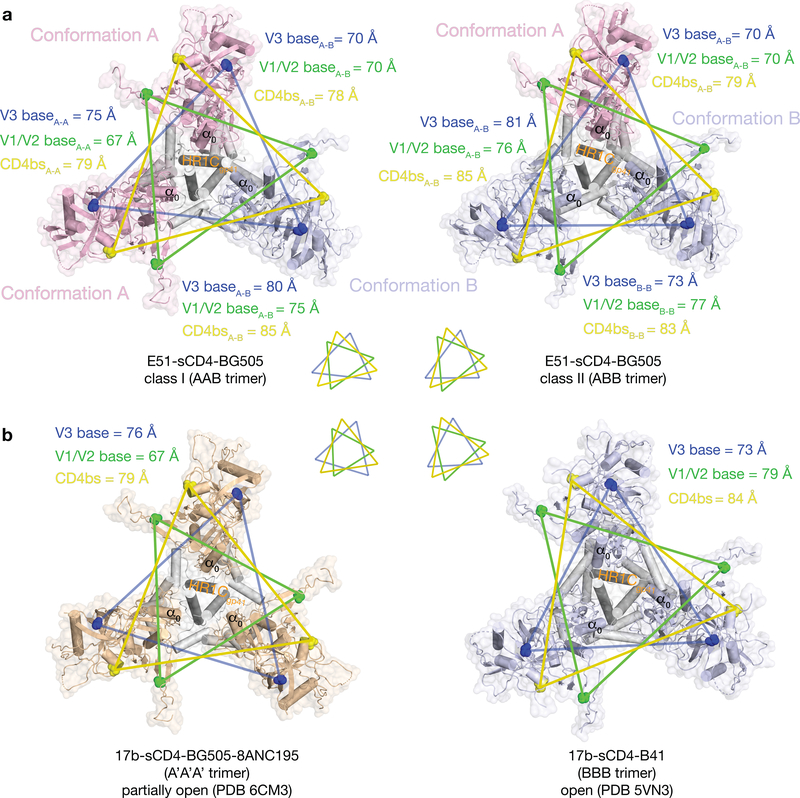

Whereas other structures of CD4i-sCD4-Env complexes (open and partially-open CD4i-sCD4-Env structures) are three-fold symmetric5,7, the E51-sCD4-BG505 complexes are asymmetric, exhibiting two distinct conformations referred to here as class I and class II (Fig. 3a). The class I and class II Env trimers are distinguished by containing different proportions of two distinct gp120-gp41 protomer conformations, defined by differences in the gp120 core (gp120 residues excluding V1V2 and V3) and in gp41 (Fig. 3a; Supplementary Video). The class I Env trimer contained two protomers in conformation A and one protomer in conformation B (AAB trimer), whereas the class II Env trimer contained one protomer in conformation A and two protomers in conformation B (ABB trimer) (Fig. 3a). When compared with gp120s from partially-open Env protomers in a 17b-sCD4-BG505–8ANC195 complex7 and a 17b-sCD4-B41 complex with a fully-open symmetric Env trimer5, the protomer A conformation was intermediate between the conformations of the protomers in the partially-open and fully-open Env trimers, whereas the protomer B conformation corresponded to the protomer conformation in the fully-open Env trimer (Fig. 3b; Table S1). We found no classes containing symmetric Env trimers with all three protomers adopting the same conformation.

Figure 3. BG505 Env trimers are asymmetric in the class I and class II E51-sCD4-BG505 structures.

a, Top-down views of BG505 trimers in class I (left) and class II (right) conformations with the protomer conformation A in light pink and the protomer conformation B in light blue. Inter-protomer distances between three residues (V3 base residue His330gp120, V1V2 base residue Pro124gp120, and CD4 binding site (CD4bs) residue Asp368gp120) are indicated in colored lines on the structures and shown schematically as triangles below the structures. b, Top-down views of Env trimers in symmetric CD4i-sCD4-Env complex structures. Inter-protomer distances between the three residues used for analysis in panel a are indicated in colored lines on the structures and shown schematically as triangles above the structures. A’ denotes the conformation of protomers in a partially-open sCD4-bound structure (PDB 6CM3)7.

To compare and quantify the A and B gp120-gp41 protomer conformations, we started by aligning on an unaltered region at the gp120 base that is in common amongst the six Env protomers within the class I and class II Env structures, This region is formed by a three-stranded β-sheet (N- and C-terminal gp120 strands (β4 and β26) and the N-terminal gp41 β-strand), about which the gp41 heptad repeat 2 (HR2) helices are wrapped (Fig. 4a; Supplementary Video). Upon sCD4 binding, the core of gp120 in the closed Env trimer conformation is displaced relative to this region, pivoting around a hinge surrounding residues Gly41gp120 and Pro493gp120 (Fig. 4a). The A and B protomer conformations can be distinguished after superimposing the hinge region β-strands (gp120 β4 and β26) from the six protomers in the class I and class II trimers as follows: (i) gp120-gp41 protomer conformation A: a conformation in which the gp120 core is located closer to the central axis of the trimer than in fully-open sCD4-bound trimers5, but further from the central axis than in partially-open sCD4-bound trimers7, and (ii) gp120-gp41 protomer conformation B: a conformation corresponding to fully-open sCD4-bound trimers5 in which gp120 is further from the central axis (Fig. 3a,b). The centers of mass (c.o.m.) of the gp120 cores in conformations A and B differed by 7.3 Å (calculated for 345 Cα atoms), and lines joining the centers of mass to the hinge residue Pro493gp120 differed an angle of 11.40° (Fig. 4b).

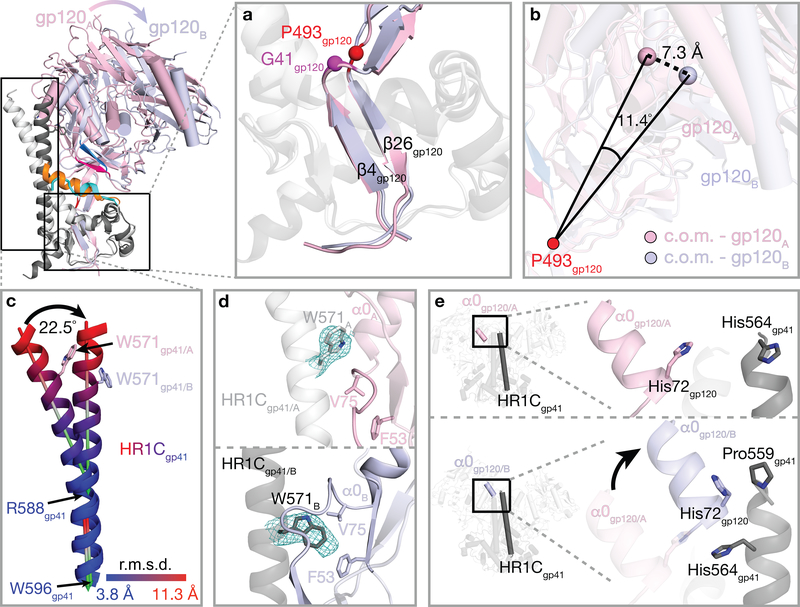

Figure 4. Protomers A and B exhibit different structural features (see also Supplementary Video).

Top left, overlay of cartoon representations of gp120 conformations A (pink) and B (light blue) and gp41 conformations A (light grey) and B (dark grey). Insets show close-up views of features discussed in the text. a, Superimposition of gp120 β4 and β26 strands in protomers A and B. b, Definition of lines joining the hinge residue Pro493gp120 to the center of mass (c.o.m.) of the gp120s in conformations A and B. The lines differed by an angle of 11.4° and a displacement of 7.3 Å. c, Differences in the protomer A and B HR1C helices. After superimposition of gp120 β4 and β26 strands in protomers A and B (panel a), the C-terminal portion of the HR1C helix (Arg588gp41–Trp596gp41) was similar between the two conformations (angle between the two helical axes of 2.5°), whereas the N-terminal portion (Leu565gp41–Glu584gp41) showed deviations up to 11.3 Å at the helix N-termini and a helical axis angle difference of 22.5°. d, Comparison of the location and conformation of gp41 HR1C residue Trp571gp41 in protomer conformations A (top) and B (bottom). e, The gp120 α0 helix in conformation B, but not conformation A, facilitates an extension of the gp41 HR1C N-terminus of a neighboring protomer.

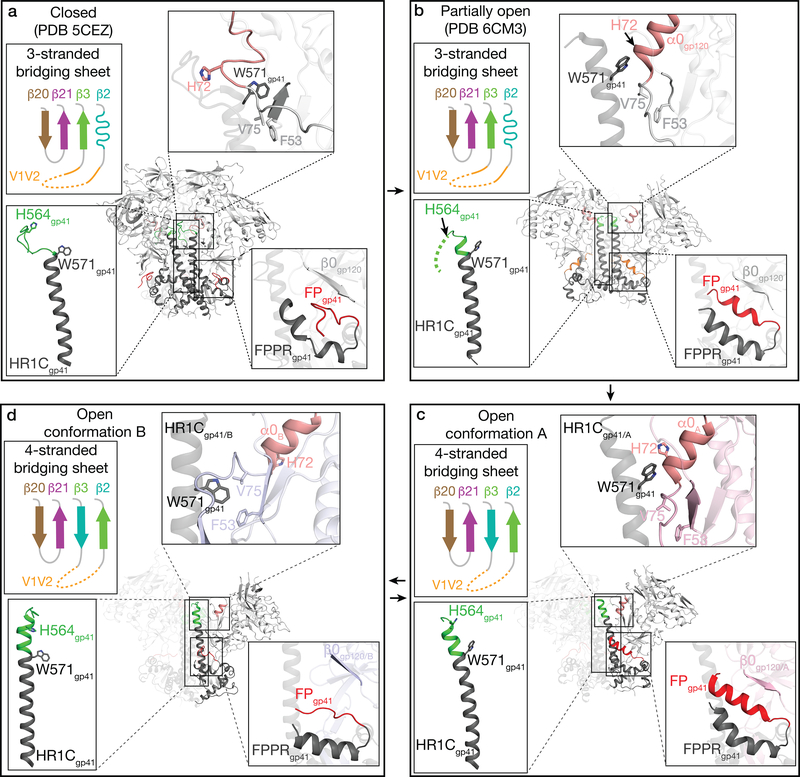

Transition between open gp120-gp41 protomer conformations demonstrate plasticity of gp41 HR1C

Conformational differences in gp41 between protomer conformations A and B include changes in the gp41 HR1C helix. In closed and sCD4-bound partially-open Env trimer structures, three gp41 HR1C segments form a three-helix bundle around a three-fold symmetric Env trimer axis7, whereas the gp41 HR1C helices deviated from three-fold symmetry in the E51-sCD4-bound–class I and class II Env trimers. After superimposition of the protomer A and B gp120 β4 and β26 strands, the C-terminal portion of the HR1C helix (Arg588gp41–Trp596gp41) was similar between the protomer A and protomer B conformations (angle between the two helical axes = 2.5°), whereas the N-terminal portion (Leu565gp41–Glu584gp41) showed deviations up to 11.3 Å at the N-termini of the helices and a helical axis angle difference of 22.5°, resulting in a bent protomer A HR1C helix and a straight protomer B HR1C helix (Fig. 4c). The straight conformation of the protomer B HR1C helix allowed insertion of the Trp571gp41 sidechain into a pocket located below the loop connecting gp120 α0 helix and β0 strand, where it is sandwiched by hydrophobic residues Phe53gp120 and Val75gp120, whereas the Trp571gp41 sidechain in the bent protomer A HR1C helix is above the loop, preventing the α0 helix and β0 strand from adopting the B conformation (Fig. 4d).

The short gp120 α0 helix conformation frees up space that allowed straightening of the gp41 HR1C helix; in addition, the gp120 α0 helix is adjacent to the N-terminus of the HR1C from a neighboring protomer in conformation B, but not to the HR1C from a neighboring protomer in conformation A (Fig. 4e). As a result, a conserved histidine residue (His72gp120) of the conformation B gp120 α0 is brought in proximity to residue Pro559gp41 of the neighboring gp41 HR1C, enabling extension of ordered density for the N-terminus of the gp41 HR1C helix by four residues (His560gp41-Glu564gp41), as compared to the counterpart region of gp41 adjacent to a conformation A gp120 α0 helix, in which ordered density does not extend beyond Pro559gp41 (Fig. 4e).

The fusion peptide conformation is coupled to Env protomer conformational states

While the conformation of the fusion peptide in closed Env structures is either disordered (e.g., PDB codes 4NCO and 3J5M) or in a loop conformation (e.g., PDBs 5CEZ, 5CJX, 4ZMJ) (with the exception of closed Envs in which the fusion peptide is directly stabilized by antibodies such as PGT15129 and VRC3430), the fusion peptide formed a partial helix in a partially-open Env trimer complexed with 17b, sCD4 and 8ANC1957 (Extended Data 5). In our E51-sCD4-BG505 complex structures, a full-length ordered α-helix was found for the fusion peptide in protomer A, which resides in a hydrophobic environment that includes gp120 β-strands and the fusion peptide proximal region (FPPR; residues 530gp41-545gp41, as defined in ref.31). In contrast, for gp120-gp41 protomer conformation B in which gp120 is further displaced from the Env trimer axis, the outermost gp120 β-strand (β0) is elevated with respect to the Env trimer base, whereas the FPPR is lower. The straight protomer B HR1C helix, but not the bent protomer A HR1C helix (Fig. 4c), results in displacement of the protomer B fusion peptide from the hydrophobic environment it occupies in the protomer A conformation. The result of these conformational changes is exposure of the fusion peptide residues to solvent, where it adopts a less-ordered loop structure in protomer B than the helical conformation in protomer A (Fig. 5; Supplementary Video). The conformational differences in the protomer A and B fusion peptide conformations are anchored at the sidechain of Phe522gp41, which has been described as an pivot point for the flexible fusion peptide32, and whose orientation differs between the A and B protomer conformations (Fig. 5). Phe522gp41 also serves as an anchor point for fusion peptide conformational changes in closed Env trimer structures bound to PGT15129 or VRC3410. In our structures, the transition from conformation A to B was accompanied by the release of hydrophobic residues Phe522gp41 and Leu523gp41, resulting in reorientation of their side chains (Fig. 5; Supplementary Video).

Figure 5. gp41 exhibits different conformations in protomers A and B (see also Supplementary Video).

a, Class I Env trimer. The gp41 fusion peptide is α-helical in two conformation A protomers in the class I structure (AAB trimer), and adopts a partially-ordered loop structure in the conformation B protomer. b, Class II Env trimer. The fusion peptide is α-helical in one conformation A protomer and in two conformation B protomers in the class II structure (ABB trimer).

Discussion

The HIV-1 Env trimer functions in the first step of viral infection: fusion of the viral and host lipid bilayers to allow entry of the HIV-1 capsid and its RNA into the host cell cytoplasm1. Membrane fusion requires major conformational changes in Env, including CD4-induced and(or) stabilized opening of the closed prefusion Env resulting in an open trimer that exposes the coreceptor binding site, rearrangement to allow insertion of the gp41 fusion peptide into the host cell membrane upon coreceptor binding, membrane fusion, and culmination a post-fusion gp41 helical bundle structure1. Structural information for a subset of these conformational states exists: (i) closed, prefusion HIV-1 Env structures have been characterized by crystallographic and cryo-EM structures of Env trimers10, (ii) sCD4-bound open Env trimer structures5–7, including those reported here, defining structural rearrangements resulting from receptor binding, and (iii) the post-fusion six-helical bundle structures of gp4133,34.

We know less about the conformational changes that occur after CD4 binding and before six-helical gp41 bundle formation because there is currently no structural information for sCD4 plus coreceptor-bound Env trimers. However, a sCD4- and CCR5-bound cryo-EM structure of a gp120 monomer revealed the CCR5 footprint on gp120, including interactions of the tyrosine-sulfated N-terminus of CCR519. The CCR5 binding site on gp120 overlaps with the binding sites of CD4i antibodies, which mimic host coreceptors by requiring CD4-induced conformational changes within Env for binding, and CD4i antibodies sometimes further resemble CCR5 by including tyrosines modified by sulfation20,23,35. Structures of CD4i-sCD4-Env trimers can therefore be used to infer Env trimer rearrangements required for coreceptor binding, and if including a tyrosine-sulfated CD4i antibody, to gain understanding of the role of tyrosine sulfation in recognition of HIV-1 Env. Here we report cryo-EM structures of E51, a tyrosine-sulfated CD4i antibody, complexed with an open sCD4-bound BG505 Env trimer. The structures define interactions of two E51 sulfated tyrosines with gp120 and reveal unexpected asymmetry in sCD4-bound Env trimers.

Env interactions of E51 sulfated tyrosines

The E51-sCD4-BG505 structures revealed V1V2 displacement from the trimer apex to its sides, which exposes the gp120 V3 region to allow interactions with the E51 CDRH3 (Supplementary Video). As in other CD4-CD4-Env trimer structures5–7, the E51 interaction with V3 involved the base of the loop (Fig. 1b). By contrast, CCR5 interacts extensively with the exposed V3 loop19 that is disordered in CD4i-sCD4-Env trimer structures5–7. In the E51-sCD4-BG505 structures, EM density for the two sulfated tyrosines (Tys100FE51 HC and Tys100IE51 HC) in E51 Fab (Extended Data 1) allowed a detailed description of electrostatic and cation-π interactions between the Tys residues and gp120 (Fig. 2a). One of the E51 residues (Tys100IE51 HC) made analogous interactions with gp120 as a CCR5 sulfated tyrosine and a sulfated tyrosine within the 412d CD4i antibody25 (Fig. 2a). Structural comparisons of the E51, 412d, and CCR5 complexes with trimeric (for E51) or monomeric (for 412d and CCR5) Envs showed that each of the tyrosine-sulfated CD4i Fabs included one sulfated tyrosine (Tys100IE51 HC and Tys100412d) that directly mimicked a CCR5 sulfated tyrosine and an additional sulfated tyrosine (Tys100FE51 HC and Tys100C412d) that made distinct interactions with gp120 (Fig. 2a).

Comparisons of the interactions of CD4-bound gp120 with E51’s CDRH3 and with CCR519 suggest a possible scenario for the high potency of eCD4-Ig, a reagent in which a sulfopeptide corresponding to the E51 CDRH3 was fused to the C-terminus of CD4-Fc27,36. Namely, the effects of electrostatic interactions of E51 sulfotyrosines with positively-charged residues on gp120 in combination with interactions of the short helix in the CDRH3 of bound E51 (Fig. 2d) (if the helix forms in the context of the CDRH3 sulfopeptide) with the four-stranded gp120 bridging sheet (Fig. 2a) could contribute to specific binding of eCD4-Ig to the sCD4-induced Env conformation in which these regions are accessible. By contrast, these regions are buried in the closed Env conformation in which the bridging sheet has only three strands that differ in topology from the four-stranded bridging sheet in open sCD4-bound Env conformations (Fig. 6a–d; Supplementary Video).

Figure 6. Summary of conformational changes described in text between closed and various open Env conformations (see also Supplementary Video).

Env conformations are indicated, along with the complex from which the Env structure was derived. a, Closed Env trimer conformation (PDB 5CEZ). b, Partially-open sCD4-bound Env conformation (PDB 6CM3). c, Open conformation A (intermediate between partially-open and fully-open sCD4-bound Env conformations). d, Fully-open sCD4-bound Env conformation B.

A model of Env fusion activation

Although previous sCD4-bound Env structures were three-fold symmetric5–7, the E51-sCD4-BG505 complex structures displayed Env trimer asymmetry, including differences in the degree of gp120 rearrangement and distinct conformations for specific structural elements within gp120-gp41 protomers. Given the relatively small number of available sCD4-bound open Env structures, it is unclear why the Env trimers in the E51-sCD4-Env structures were asymmetric. However, these new open Env conformations can be used to deduce likely states of structural changes in HIV-1 Env upon CD4 binding. Comparison of the class I and class II E51-sCD4-Env structures with previous closed and partially-open Env structures suggest a model for the initial sCD4-induced conformational changes that lead to coreceptor binding and fusion (Fig. 6a–d). As previously described, sCD4 binding to gp120 subunits within Env trimer leads gp120 rotation and outward displacement4 and to repositioning of the V1V2 domain from the trimer apex in closed Env to the sides of trimer in sCD4-bound Env6 (Supplementary Video), resulting in formation of the four-stranded gp120 bridging sheet and exposure of the coreceptor binding site on V37. The rotation and displacement of gp120 subunits in sCD4-bound Env trimer structures results in loss of intra-protomer gp120 contacts, a conformation that is either captured by sCD4 during Env “breathing” and (or) is driven by CD4 binding that induces the straightening of the gp41 HR1C helix observed in the protomer B conformation (Fig. 4c). Apparently synchronized conformational changes that differentiate the less-open protomer A conformation (Fig. 6c) and the fully-open protomer B conformation (Fig. 6d) include: (i) gp120 outward displacement that opens space for extension of the HR1Cgp41 N-terminus, (ii) displacement of the gp120 α0 helix closer to HR1Cgp41 N-terminus of the neighboring protomer to facilitate a loop-to-helix transition at the HR1Cgp41 N-terminus, and (iii) elevation of the gp120 β0 strand and lowering of the portion of the gp41 helix C-terminal to the fusion peptide, presumably releasing the fusion peptide from the hydrophobic environment observed in the closed10, partially-open sCD4-bound Env structures7, and protomer A conformations.

We now have structural information relevant to sCD4-induced (or captured) conformational changes in four distinct Env trimer conformations: closed10 (Fig. 6a), partially-open sCD4-bound7 (Fig. 6b), the sCD4-bound protomer A in the E51-sCD4-BG505 structures (Fig. 6c), and the fully-open conformation of the sCD4-bound protomer B in the E51-sCD4-BG505 structures (this study) (Fig. 6d) and in the 17b-sCD4-B41 Env structure5. These conformations may represent snapshots of transitions from closed Env trimer (Fig. 6a) to various forms of partially-open trimers (Fig. 6b,c), prior to adopting the fully-open sCD4-bound Env conformation (Fig. 6d) that can interact with coreceptor to undergo further changes resulting in full release of the gp41 fusion peptide. Thus the ability of single-particle cryo-EM to reveal multiple conformations of a protein-protein complex facilitates understanding of conformational changes required during the function of a complicated process such as HIV-1 Env-mediated membrane fusion.

Methods

Protein expression and purification

A native-like, soluble HIV Env gp140 trimer BG505 SOSIP.664 construct including ‘SOS’ mutations (A501Cgp120, T605Cgp41), the ‘IP’ mutation (I559Pgp41), introduction of an N-linked glycosylation site mutation (T332Ngp120) and improved furin protease cleavage site (REKR to RRRRRR), and truncation after the C-terminus of gp41 residue 6648 subcloned into the pTT5 expression vector (National Research Council of Canada) and expressed by transient expression in HEK293–6E cells. BG505 Env trimer was purified from HEK 6E cell supernatants by 2G12 immunoaffinity and size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) using a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL (GE Life Sciences) as described26.

The heavy and light chains of 6x-His tagged E51 Fab were co-expressed with tyrosylprotein sulfotransferase II (TPST II)27 in HEK293–6E cells and purified from transiently-transfected cell supernatants by Ni-NTA chromatography followed by SEC. To separate differentially tyrosine-sulfated species, purified E51 Fab in Tris-Cl pH 9.0 was applied to a Mono Q 5/50 GL anion exchange column (GE Life Sciences) and eluted using a linear salt gradient from 0 mM to 1 M NaCl. Fractions corresponding to three Fab species (Extended Data 1a) were buffer exchanged during SEC into TBS (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.02% NaN3).

C-terminally 6x-His tagged sCD4 (D1D2 domain residues 1–186) was expressed in HEK293–6E cells and purified from transiently-transfected cell supernatants by Ni-NTA chromatography followed by SEC as described7.

Mass spectrometric characterization of E51 Fab

E51 Fab samples were analyzed by LC-MS in the positive ion mode using an LCT Premier XE Time-of-Flight mass spectrometer (Waters Corporation). The sample was introduced by a 2.1×50 mm, 450Å, 2.7μm particle BioResolv mAb PolyPhenyl column (Waters Corporation) using a 7-minute gradient of water and acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid. Raw spectra were averaged and deconvoluted with the MassLynx software (Waters Corporation).

Cryo-EM sample preparation

E51-sCD4-BG505 complexes were generated by incubating purified BG505 SOSIP.664 trimer with E51 and sCD4 at a molar ratio of 4:4:1 (E51:sCD4:Env trimer) at room temperature for 2 hours, transferred to 4°C overnight, and then concentrated to 1.2 mg/mL. Cryo-EM grids were prepared using a Mark IV Vitrobot (ThermoFisher) operated at 10°C and 100% humidity. 3.2 μL of concentrated sample was applied to 300 mesh Quantifoil R2/2 grids, blotted for 4 s, and then plunge-frozen in liquid ethane that is surrounded by liquid nitrogen.

Cryo-EM data collection and processing

Cryo-grids were loaded onto a 300kV Titan Krios electron microscope (ThermoFisher) equipped with a GIF Quantum energy filter (slit width 20 eV) operating at a nominal 130,000x magnification. Images were recorded on a K2 Summit direct electron detector (Gatan) operating in counting mode with a pixel size of 1.057 Å•pixel−1. The defocus range was set to 1–2.8 μm. Each image was exposed for 8 s and dose-fractionated into 40 subframes with a total dose of 64 e−•pixel−1, generating a dose rate of 1.6 e−•pixel−1•subframe−1. A total of 3128 images were motion-corrected using MotionCor237 without binning. Micrographs CTF were estimated using Gctf 1.0638. Initially, ~1000 particles were manually picked and reference-free 2D classes were generated using RELION39,40. Particles from good 2D classes were used as references for particle picking using RELION AutoPicking39,40. A total of 941,841 particles used for three rounds of reference-free 2D classification in RELION39,40. After removing ice contaminants, damaged particles and aggregates, 687,259 particles from good classes were combined and used for 3D classification (Extended Data 2a). Low-pass (80 Å) filtered coordinates from a partially-open sCD4-bound BG505 SOSIP Env trimer (PDB 6CM3) were used as a reference for initial 3D classifications. Two major classes (class I and class II) were generated from the first round of 3D classification. Particles from good classes were combined for a second round of 3D classification using the class I map low-pass filtered to 80 Å. Both 3D classification steps were performed assuming C1 symmetry. Class I contained 320,895 particles and class II contained 182,970 particles (Extended Data 2b). 3D auto-refinement for both classes were performed assuming C1 symmetry with the E51 Fab CHCL domains and the sCD4 D2 domain masked out, generating 3.8 Å and 3.9 Å resolution maps for class I and class II, respectively, whereas 3D auto-refinements performed using C3 symmetry produced maps with overall resolutions worse than 7 Å for both classes (data not shown). Particle CTF refinement, particle polishing, and post processing were performed in RELION39,40 for the two classes of asymmetric maps, which produced two 3D reconstructions with overall resolutions of 3.3 Å for class I and 3.5 Å for class II, calculated using the gold-standard FSC 0.143 criterion41 (Extended Data 3).

Model building

Coordinates for gp120, gp41, E51 Fab, and sCD4 D1 were fitted into the corresponding regions of the density maps. The following coordinate files were used for initial fitting: BG505 gp120 monomer, gp41 monomer, and sCD4 D1 from the partially-open complex (PDB 6CM3), and E51 Fab from its crystal structure (PDB 1RZF). Coordinates for the two classes of complex structures as well as the N-linked glycans were manually refined and built in Coot42. Multiple rounds of whole-complex refinement using phenix.real_space_refine43,44 and manual refinement were performed to correct for interatomic bonds and angles, clashes, residue side chain rotamers, and residue Ramachandran outliers.

Structural analyses

Buried surface areas were calculated using PDBePISA45 and a 1.4 Å probe. Potential hydrogen bonds were assigned using the geometry criteria with separation distance of <3.5 Å and A-D-H angle of >90 °. The maximum distance allowed for a potential van der Waals interaction was 4.0 Å. Protein surface electrostatic potentials were calculated in PyMol (Schrödinger LLC). Briefly, hydrogens were added to proteins using PDB2PQR46, and an electrostatic potential map was calculated using APBS47.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The structural coordinates were deposited into the Worldwide Protein Data Bank (wwPDB) with accession code 6U0L (class I E51-BG505 SOSIP.664-sCD4 complex) and 6U0N (class II E51-BG505 SOSIP.664-sCD4 complex). EM density maps were deposited into EMDB with accession numbers EMD-20605 (class I) and EMD-20608 (class II). Other data are available upon reasonable request.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1. Mass spectrometry characterization of E51 Fab.

a, Peak fractions from anion exchange chromatography of E51 Fab. b, Mass spectra of the three E51 peaks from panel a. The molecular mass for Peak 1 corresponded within 27 Da to the predicted mass for unmodified E51 Fab (48,791 Da), suggesting this E51 Fab fraction contained no sulfated tyrosines. The molecular masses for Peaks 2 and 3 were each increased by 80 Da from the preceding peak, corresponding to the molecular weight of a SO3− group (80 Da). These results are consistent with the identification of Peaks 2 and 3 as E51 Fab with one and two sulfated tyrosines, respectively. Peak 3 was used for preparing complexes for cryo-EM.

Extended Data Fig. 2. Data processing for BG505 SOSIP-sCD4-E51 complex structures.

a, Example of a motion-corrected and dose-weighted micrograph of E51-sCD4-BG505 complexes (representative individual particles in boxes). Scale bar = 50 nm. Defocus was ~2.6 μm underfocus. b, Data processing scheme. Collected micrographs were motion-corrected using MotionCor2 (ref.1) without binning. Contrast transfer functions (CTFs) were estimated using Gctf 1.06 (ref.2). ~1,000 particles were manually picked and subjected to 2D classification in RELION3,4. Particles from good classes were used as references for automatic particle picking using RELION AutoPicking. 941,841 autopicked particles were subjected to three rounds of reference-free 2D classification. In each round, particles from good 2D classes were selected, which gave 656,059 particles. Subsequently, using the Env trimer portion of an 80 Å low-pass filtered partially-open trimeric BG505 SOSIP structure (PDB 6CM3) as the reference model, first round of 3D classification was performed assuming C1 symmetry. Particles from good classes were combined and used for a second round of 3D classification with C1 symmetry. The resulting maps could be grouped into two classes: class I (320,895 particles) and class II (182,970 particles). Maps from the two classes were refined separately assuming C1 symmetry with the sCD4 D2 domain and E51 Fab CHCL domains masked out. After CTF refinement, movie refinement, and particle polishing, the class I and class II post-processed maps were refined to 3.3 Å and 3.5 Å resolution (FSC 0.143), respectively (Fig. S3).

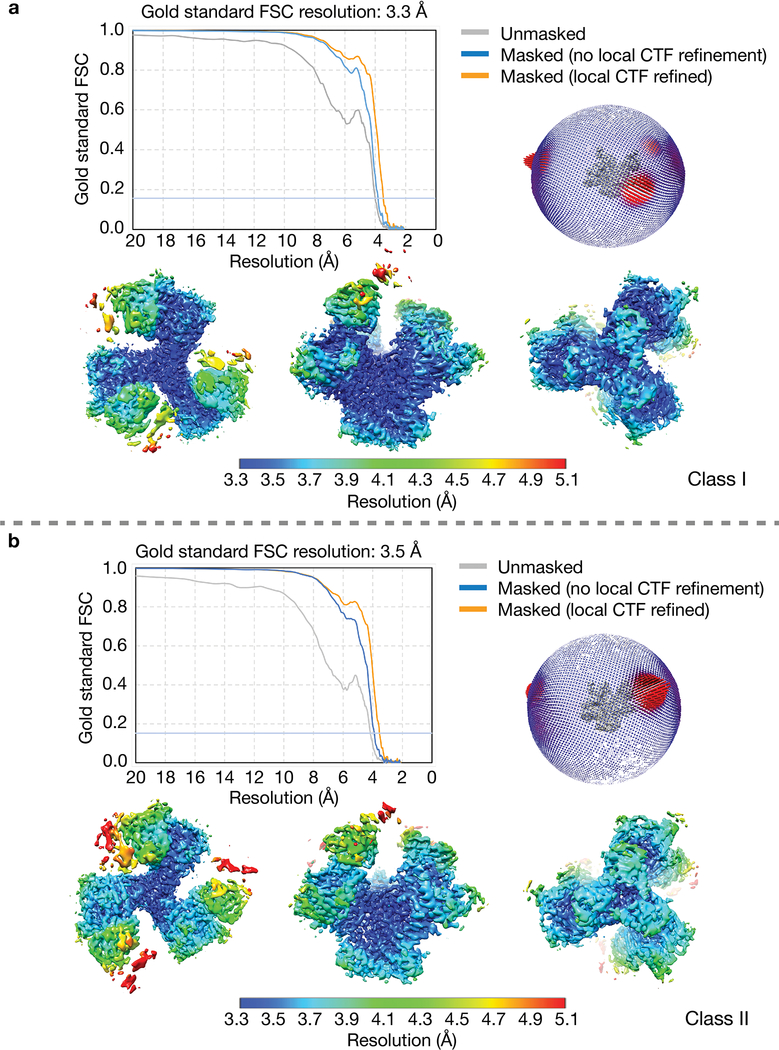

Extended Data Fig. 3. Validation of the BG505 SOSIP-sCD4-E51 complex structures.

Class I (panel a) and class II (panel b) E51-sCD4-BG505 complex structures. Top left in both panels: Gold-standard Fourier Shell Correlations (FSCs) of two classes of maps. Top right: Orientation distributions for class I and class II structures. Bottom: Local resolution estimations for class I and class II density maps (calculated using the local resolution program in RELION3,4).

Extended Data Fig. 4. Representative densities for class I and class II E51-sCD4-BG505 complex structures.

a, Densities for residues involved in E51 CDRH3 sulfotyrosine interactions. b, Densities for fusion peptides in protomers A (top) and B (bottom). c, Densities for HR1C helices in protomers A (top) and B (bottom)

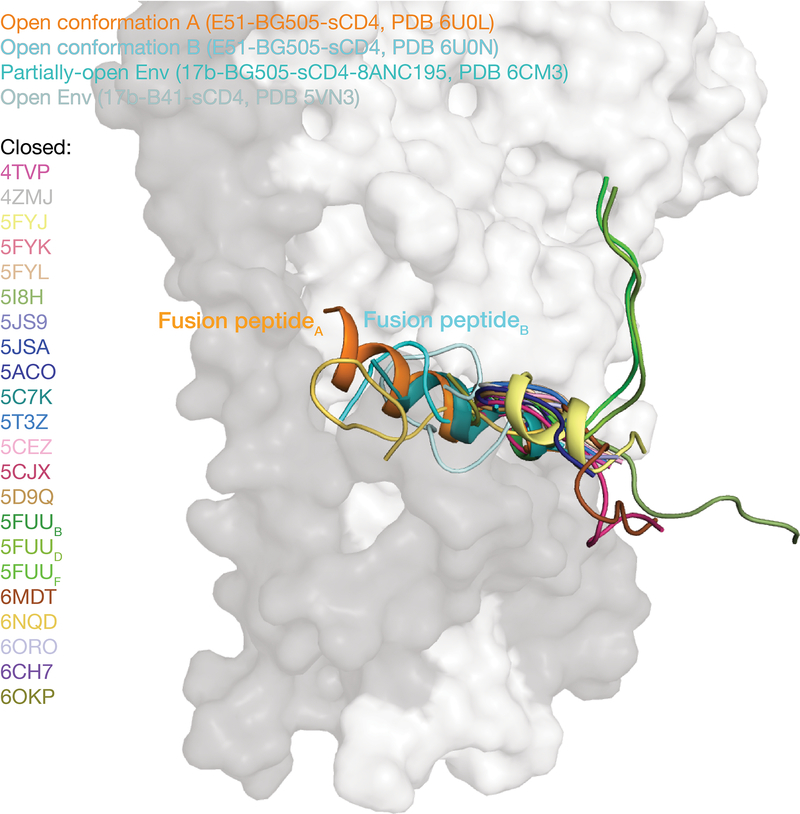

Extended Data Fig. 5. Comparison of fusion peptide conformations in Env structures.

The fusion peptide is orange in the conformation A protomer, cyan in the conformation B protomer (from the E51-sCD4-BG505 complex structures reported here), teal in a partially-open 17b-sCD4-BG505–8ANC195 complex (PDB 6CM3), and pale cyan in a fully-open 17b-sCD4-B41 complex (PDB 5VN3). Fusion peptides from Env trimers in a closed, prefusion conformation are color coded as shown for their PDB IDs. References for structures are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank M. Farzan, A.P. West, and C.O. Barnes for helpful discussions. Structural studies were performed in the Biological and Cryogenic Transmission Electron Microscopy Center at Caltech with assistance from directors A. Malyutin and S. Chen. We thank the Gordon and Betty Moore and Beckman Foundations for gifts to Caltech to support electron microscopy, Z. Yu (Janeila Farm) for advice on cryo-EM, J. Vielmetter and the Caltech Protein Expression Center for protein production, and M. Shahgholi and the Caltech Protein Exploration Laboratory for mass spectrometry analyses. This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health Grant HIVRAD P01 P01AI10014 (P.J.B.) and the National Institutes of Health Grant P50 8 P50 AI150464–13 (P.J.B.).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Harrison SC Viral membrane fusion. Virology 479–480, 498–507 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choe H et al. The beta-chemokine receptors CCR3 and CCR5 facilitate infection by primary HIV-1 isolates. Cell 85, 1135–48 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feng Y, Broder CC, Kennedy PE & Berger EA HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor. Science 272, 872–7 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu J, Bartesaghi A, Borgnia MJ, Sapiro G & Subramaniam S Molecular architecture of native HIV-1 gp120 trimers. Nature 455, 109–13 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ozorowski G et al. Open and closed structures reveal allostery and pliability in the HIV-1 envelope spike. Nature 547, 360–363 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang H et al. Cryo-EM structure of a CD4-bound open HIV-1 envelope trimer reveals structural rearrangements of the gp120 V1V2 loop. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113, E7151–E7158 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang H, Barnes CO, Yang Z, Nussenzweig MC & Bjorkman PJ Partially Open HIV-1 Envelope Structures Exhibit Conformational Changes Relevant for Coreceptor Binding and Fusion. Cell Host Microbe 24, 579–592 e4 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanders RW et al. A next-generation cleaved, soluble HIV-1 Env Trimer, BG505 SOSIP.664 gp140, expresses multiple epitopes for broadly neutralizing but not non-neutralizing antibodies. PLoS Pathog 9, e1003618 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alsahafi N, Debbeche O, Sodroski J & Finzi A Effects of the I559P gp41 change on the conformation and function of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) membrane envelope glycoprotein trimer. PLoS One 10, e0122111 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ward AB & Wilson IA The HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein structure: nailing down a moving target. Immunol Rev 275, 21–32 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burton DR & Hangartner L Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies to HIV and Their Role in Vaccine Design. Annu Rev Immunol 34, 635–59 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeVico AL CD4-induced epitopes in the HIV envelope glycoprotein, gp120. Curr HIV Res 5, 561–71 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burton DR et al. HIV vaccine design and the neutralizing antibody problem. Nat Immunol 5, 233–6 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thali M et al. Characterization of conserved human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 neutralization epitopes exposed upon gp120-CD4 binding. J Virol 67, 3978–88 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiang SH, Doka N, Choudhary RK, Sodroski J & Robinson JE Characterization of CD4-induced epitopes on the HIV type 1 gp120 envelope glycoprotein recognized by neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 18, 1207–17 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Decker JM et al. Antigenic conservation and immunogenicity of the HIV coreceptor binding site. J Exp Med 201, 1407–19 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Labrijn AF et al. Access of antibody molecules to the conserved coreceptor binding site on glycoprotein gp120 is sterically restricted on primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol 77, 10557–65 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.<Kwong PD et al. Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing human antibody. Nature 393, 648–59 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaik MM et al. Structural basis of coreceptor recognition by HIV-1 envelope spike. Nature 565, 318–323 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farzan M et al. Tyrosine sulfation of the amino terminus of CCR5 facilitates HIV-1 entry. Cell 96, 667–76 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiang SH et al. Epitope mapping and characterization of a novel CD4-induced human monoclonal antibody capable of neutralizing primary HIV-1 strains. Virology 315, 124–134 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang CC et al. Structural basis of tyrosine sulfation and VH-gene usage in antibodies that recognize the HIV type 1 coreceptor-binding site on gp120. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101, 2706–11 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choe H et al. Tyrosine sulfation of human antibodies contributes to recognition of the CCR5 binding region of HIV-1 gp120. Cell 114, 161–70 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diskin R, Marcovecchio PM & Bjorkman PJ. Structure of a clade C HIV-1 gp120 bound to CD4 and CD4-induced antibody reveals anti-CD4 polyreactivity. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17, 608–13 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang CC et al. Structures of the CCR5 N terminus and of a tyrosine-sulfated antibody with HIV-1 gp120 and CD4. Science 317, 1930–4 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scharf L et al. Broadly Neutralizing Antibody 8ANC195 Recognizes Closed and Open States of HIV-1 Env. Cell 162, 1379–90 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gardner MR et al. AAV-expressed eCD4-Ig provides durable protection from multiple SHIV challenges. Nature 519, 87–91 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cormier EG et al. Specific interaction of CCR5 amino-terminal domain peptides containing sulfotyrosines with HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein gp120. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97, 5762–7 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee JH, Ozorowski G & Ward AB Cryo-EM structure of a native, fully glycosylated, cleaved HIV-1 envelope trimer. Science 351, 1043–8 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kong R et al. Fusion peptide of HIV-1 as a site of vulnerability to neutralizing antibody. Science 352, 828–33 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumar S et al. Capturing the inherent structural dynamics of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein fusion peptide. Nat Commun 10, 763 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dingens AS et al. Complete functional mapping of infection- and vaccine-elicited antibodies against the fusion peptide of HIV. PLoS Pathog 14, e1007159 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chan DC, Fass D, Berger JM & Kim PS Core structure of gp41 from the HIV envelope glycoprotein. Cell 89, 263–73 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weissenhorn W, Dessen A, Harrison SC, Skehel JJ & Wiley DC Atomic structure of the ectodomain from HIV-1 gp41. Nature 387, 426–30 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dorfman T, Moore MJ, Guth AC, Choe H & Farzan M A tyrosine-sulfated peptide derived from the heavy-chain CDR3 region of an HIV-1-neutralizing antibody binds gp120 and inhibits HIV-1 infection. J Biol Chem 281, 28529–35 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fellinger CH et al. eCD4-Ig limits HIV-1 escape more effectively than CD4-Ig or a broadly neutralizing antibody. J Virol (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zheng SQ et al. MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat Methods 14, 331–332 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang K Gctf: Real-time CTF determination and correction. J Struct Biol 193, 1–12 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zivanov J et al. New tools for automated high-resolution cryo-EM structure determination in RELION-3. Elife 7(2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scheres SH RELION: implementation of a Bayesian approach to cryo-EM structure determination. J Struct Biol 180, 519–30 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scheres SH & Chen S Prevention of overfitting in cryo-EM structure determination. Nat Methods 9, 853–4 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG & Cowtan K Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66, 486–501 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adams PD et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66, 213–21 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Afonine PV et al. Real-space refinement in PHENIX for cryo-EM and crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 74, 531–544 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krissinel E & Henrick K Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J Mol Biol 372, 774–97 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dolinsky TJ et al. PDB2PQR: expanding and upgrading automated preparation of biomolecular structures for molecular simulations. Nucleic Acids Res 35, W522–5 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baker NA, Sept D, Joseph S, Holst MJ & McCammon JA Electrostatics of nanosystems: application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98, 10037–41 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The structural coordinates were deposited into the Worldwide Protein Data Bank (wwPDB) with accession code 6U0L (class I E51-BG505 SOSIP.664-sCD4 complex) and 6U0N (class II E51-BG505 SOSIP.664-sCD4 complex). EM density maps were deposited into EMDB with accession numbers EMD-20605 (class I) and EMD-20608 (class II). Other data are available upon reasonable request.