Abstract

While tetrahedranes as a family are scarce, neutral heteroatomic species are all but unknown, with the only reported example being AsP3. Herein, we describe the isolation of a neutral heteroatomic X2Y2 molecular tetrahedron (X, Y=p‐block elements), which also is the long‐sought‐after free phosphaalkyne dimer. Di‐tert‐butyldiphosphatetrahedrane, (tBuCP)2, is formed from the monomer tBuCP in a nickel‐catalyzed dimerization reaction using [(NHC)Ni(CO)3] (NHC=1,3‐bis(2,4,6‐trimethylphenyl)imidazolin‐2‐ylidene (IMes) and 1,3‐bis(2,6‐diisopropylphenyl)imidazolin‐2‐ylidene (IPr)). Single‐crystal X‐ray structure determination of a silver(I) complex confirms the structure of (tBuCP)2. The influence of the N‐heterocyclic carbene ligand on the catalytic reaction was investigated, and a mechanism was elucidated using a combination of synthetic and kinetic studies and quantum chemical calculations.

Keywords: dimerization, homogeneous catalysis, nickel, phosphaalkynes, phosphorus

Free dimer at last: Di‐tert‐butyldiphosphatetrahedrane is accessible by the facile nickel‐catalyzed dimerization of tert‐butyl phosphaalkyne. This compound not only represents an uncomplexed phosphaalkyne dimer, but is also the first example of a tetrahedral molecule with carbon and phosphorus atoms in its scaffold.

Tetrahedranes (tricyclo[1.1.0.02, 4]butanes) have considerable practical and theoretical significance because of their high energy content, large bond strain and ensuing high reactivity.1 While theoretical chemists have endeavored to determine the electronic structure and the thermodynamic stability of tetrahedranes with ever increasing accuracy,2, 3, 4, 5 synthetic chemists have striven to develop effective protocols for their preparation. The isolation by Maier and co‐workers of the first organic tetrahedrane, (tBuC)4, was a milestone in organic synthesis (Figure 1 a).6 Nevertheless, the number of well‐characterized tetrahedranes remains small, even more than four decades later.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Some heavier congeners, for example, (RE)4 (E=Si and Ge, R=SitBu3) and related group 13 element compounds, are also known,14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 as are the structures adopted by white phosphorus (P4) and yellow arsenic (As4). Undoubtedly, P4 is the most industrially significant tetrahedrane. Moreover, neutral tetrahedranes containing two different heteroatoms in their skeleton are almost unknown, the only example to have been isolated so far being AsP3, which was synthesized by reaction of a niobium cyclotriphosphido complex with AsCl3.22

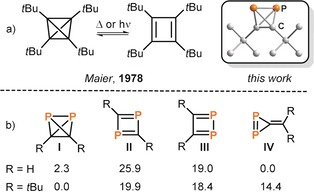

Figure 1.

a) The tetrahedrane (tBuC)4 in equilibrium with the cyclobutadiene isomer and DFT structure of (tBuCP)2;6 b) calculated relative electronic energies (ΔE in kcal mol−1) for (RCP)2 with R=H (data from ref. 3) and R=tBu (see Supporting Information).

Diphosphatetrahedranes, (RCP)2, represent a particularly attractive target in this area, potentially providing a hybrid between the two most famous tetrahedral molecules, P4 and (tBuC)4. However, high level quantum chemical studies indicate that, similar to pure carbon‐based tetrahedranes, such a species must be stabilized by bulky alkyl substituents (Figure 1 b). Thus, while 1,2‐diphosphatriafulvene (IV) is predicted to be the preferred isomer of (HCP)2, the diphosphatetrahedrane (I) is the most stable isomer of (tBuCP)2 (Figure 1 b).3, 5 Related diphosphacyclobutadienes II and III are considerably higher in energy in both cases.

We reasoned that the dimerization of phosphaalkynes, R‐C≡P, could present an elegant avenue toward elusive diphosphatetrahedranes. Indeed, transition metal‐bound phosphaalkyne dimers (most frequently 1,3‐diphosphacyclobutadienes,23 but also other isomers) commonly result from transition metal‐mediated phosphaalkyne oligomerization reactions.24 Free diphosphatetrahedranes have also been proposed as key intermediates in thermal and photochemical oligomerization reactions of phosphaalkynes, which typically lead to higher phosphaalkyne oligomers (RCP)n (n=3–6).25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 However, an uncomplexed phosphaalkyne dimer has never been observed.

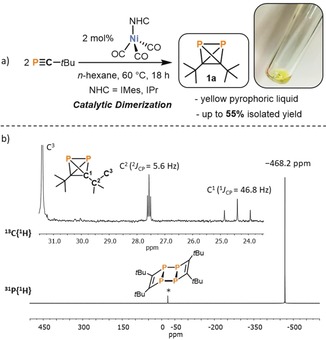

Building on previous work on iron(‐I)‐ and cobalt(‐I)‐mediated phosphaalkyne dimerizations,31, 32, 33 we recently began studying the analogous reactivity of phosphaalkynes with nickel(0) species. Unexpectedly, the 31P{1H} NMR spectrum of the reaction of [Ni(CO)4] with an excess of tBuCP (50 equivalents) exhibited a high‐field‐shifted singlet at −468.2 ppm in addition to the signal of free tBuCP at −68.1 ppm. It was anticipated that such an upfield shift could be consistent with formation of a P2C2 tetrahedron (cf. P4, δ=−521 ppm) through dimerization of tBuCP. This assumption was later confirmed through isolation of the pure product 1 a (vide infra). A subsequent screening of various nickel tricarbonyl complexes [(NHC)Ni(CO)3] (NHC=IMes, IPr, iPr2ImMe (=1,3‐di(isopropyl)‐4,5‐di(methyl)imidazolin‐2‐ylidene)) for this dimerization reaction of tBuCP revealed that the bulky NHC ligands IPr and IMes gave optimal results (see Supporting Information for details), while the use of the smaller isopropyl‐substituted ligand iPr2ImMe resulted in only a low yield of 1 a. Using [(IMes)Ni(CO)3], 1 a can be isolated in up to 55 % yield on a 500 mg scale using just 2 mol % of the nickel catalyst in n‐hexane for 18 h (Figure 2). Fractional condensation of the raw product affords pure 1 a as a pyrophoric, yellow oil with a melting point of −32 °C. Above the melting point, neat 1 a dimerizes to the known ladderane‐type tetramer 2 a (Figure 2) within several hours.25 However, 1 a is stable at −80 °C for weeks without noticeable decomposition as evidenced by 31P{1H} NMR spectroscopy. Dimerization of 1 a to 2 a is significantly slower in dilute solutions (e.g. 0.2 m in toluene). The use of 1‐adamantylphosphalkyne under similar conditions results in the analogous formation of diadamantyldiphosphatetrahedrane (1 b), as indicated by a resonance at −479.8 ppm in 31P{1H} NMR spectra. However, attempts to isolate 1 b in pure form have thus far been hampered by decomposition to higher phosphaalkyne oligomers (e.g. the ladderane (AdCP)4 (2 b) analogous to 2 a).

Figure 2.

a) Synthesis of 1 a by [(NHC)Ni(CO)3] (NHC=IMes, IPr) catalyzed dimerization of tBuCP, b) 31P{1H} and 13C{1H} NMR spectra for 1 a at 300 K in C6D6. The asterisk marks a trace of the tetramer (tBuCP)4 (2 a, that is, the dimerization product of 1 a).

Multinuclear NMR spectra of 1 a are in agreement with the tetrahedral structure with localized C 2v symmetry. The 31P{1H} NMR spectrum of 1 a in C6D6 displays a singlet resonance at −468.2 ppm similar to other tetrahedral phosphorus compounds, for example, P4 (δ(31P)=−520 ppm) and AsP3 (δ(31P)=−484 ppm).34, 35, 36 The 1H NMR spectrum shows a singlet resonance at 1.07 ppm for the tBu group. In the 13C{1H} spectrum, a singlet resonance is observed for the methyl groups, whereas the two other carbon signals split into triplets with 1 J P‐C=46.7 Hz and 2 J P‐C=5.7 Hz (Figure 2). 1 a was further characterized by elemental analysis, IR, UV/VIS spectroscopy and mass spectrometry. The UV/VIS spectrum reveals a weak absorption band at 275 nm (ϵ max=1200 L mol−1 cm−1) tailing into the visible region with a shoulder at 350 nm accounting for the yellow color. Analysis of 1 a by EI‐MS mass spectrometry revealed a molecular ion peak at m/z=200.0879 in good agreement with the calculated molecular ion peak (m/z=200.0878) and additionally showed fragmentation pathways via loss of P2 units (e.g. M+‐CH3‐P2: 123.1172, calcd 123.1173).

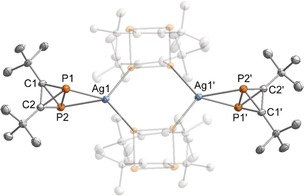

Attempts to grow single crystals of 1 a suitable for X‐ray crystallography have so far been unsuccessful. For this reason, the preparation of a metal complex was attempted with [Ag(CH2Cl2)2(pftb)] (pftb=Al{OC(CF3)3}4).37, 38 A clean reaction was observed in toluene using two equivalents of 1 a per silver atom, and a species with a significantly downfield shifted 31P{1H} NMR signal (−446.8 ppm, cf. −468.2 ppm for 1 a) was detected. Further NMR monitoring also showed the slow formation of the tetramer 2 a. A single‐crystal X‐ray diffraction study on crystals grown from CH2Cl2 revealed the formation of [{Ag(1 a)(2 a)}2][pftb]2 (3), where both 1 a and 2 a are incorporated in the same complex (Figure 3).39 Crucially, the X‐ray diffraction experiment confirms the tetrahedral structure of 1 a. The P2C2 tetrahedron is bound to the Ag atom in an η2 fashion via the P−P bond (P1−P2 2.308(3) Å). The four P−C bond lengths in the tetrahedron range 1.821(9)–1.836(9) Å, while the C−C bond length (C1−C2 1.462(12) Å) is similar to that of (tBuC)4 (average: 1.485 Å).40 Broadened singlet resonances are observed in the 31P{1H} NMR spectrum at −19.8 and −446.8 ppm when crystals of 3 are dissolved in CD2Cl2, and the 1H NMR data are also consistent with the molecular structure obtained by X‐ray crystallography.41

Figure 3.

Molecular structure of 3 in the solid state. Thermal ellipsoids are set at 50 % probability level. Hydrogen atoms and the [pftb]− counterions are omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths [Å] and angles [°]: P1‐P2 2.308(3), P1‐C1 1.836(9), P1‐C2 1.835(9), P2‐C1 1.821(9), P2‐C2 1.820(8), C1‐C2 1.462(12), C1‐P2‐P1 51.2(3), C1‐P2‐C2 47.4(4), C2‐P2‐P1 51.1(3), C1‐P1‐P2 50.6(3), C2‐P1‐P2 50.5(3), C2‐P1‐C1 46.9(4), P2‐C1‐P1 78.3(3), C2‐C1‐P2 66.3(5), C2‐C1‐P1 66.5(5), P2‐C2‐P1 78.3(3), C1‐C2‐P2 66.4(5), C1‐C2‐P1 66.6(5).45

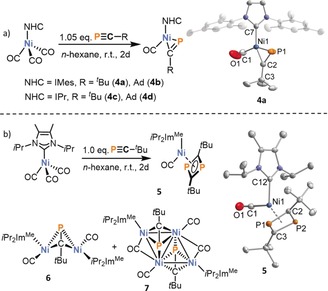

In an attempt to identify possible intermediates in the formation of 1 a, the nickel tricarbonyl complexes [(NHC)Ni(CO)3] (NHC=IMes, IPr, iPr2ImMe) were reacted with one equivalent of phosphaalkyne RCP (R=tBu, Ad) in n‐hexane at ambient temperature. Each of these reactions led to an instant color change from colorless to bright yellow and concomitant gas evolution (liberation of CO gas). For the sterically more demanding NHC ligands IPr and IMes, the phosphaalkyne complexes [(NHC)Ni(CO)(PCR)] (NHC=IMes, R=tBu (4 a), Ad (4 b), NHC=IPr; R=tBu (4 c), Ad (4 d)) featuring η2‐bound phosphaalkyne ligands were the sole P‐containing products of these reactions (Figure 4 a). Complexes 4 a–4 d can be isolated as crystalline solids in yields from 34 % to 87 %, and were characterized by single crystal X‐ray diffraction, multinuclear NMR spectroscopy, IR spectroscopy and elemental analysis (see Supporting Information for details). The structural and spectroscopic data compare well to the related, isoelectronic complexes [(iPr2Im)2Ni(PCtBu)] (iPr2Im=1,3‐di(isopropyl)imidazolin‐2‐ylidene) and [(trop2NMe)Ni(PCPh3)}] (trop=5H‐dibenzo[a,d]cyclohepten‐5‐yl).42, 43

Figure 4.

Synthesis of 4 a–d, 5, 6 and 7; and structures of 4 a and 5 in the solid state. Thermal ellipsoids are set at 50 % probability level. Hydrogen atoms and the second crystallographically independent molecule (in case of 4 a) are omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths [Å] and angles [°] for 4 a: Ni1‐C1 1.777(3), Ni1‐C7 1.931(2), Ni1‐P1 2.1793(9), Ni1‐C2 1.898(3), C1‐O1 1.137(4), P1‐C2 1.636(3), C3‐C2‐P1 144.2(2), C7‐Ni1‐P1 102.89(7), C2‐Ni1‐P1 46.67(8), C2‐Ni1‐C7 149.56(11), C2‐P1‐Ni1 57.59(10), O1‐C1‐Ni1 171.4(4); 5: Ni1‐P1 2.3114(3), Ni1‐P2 2.3113(3), Ni1‐C2 2.0898(11), Ni1‐C3 2.0637(11), P1‐C2 1.7966(11), P1‐C3 1.8143(11), P2‐C2 1.8121(11), P2‐C3 1.7992(11), Ni1‐C1 1.7538(13), C1‐O1 1.1458(17), Ni1‐C12 1.9421(11), C1‐Ni1‐C12 94.29(5), O1‐C1‐Ni1 176.74(12), C2‐P1‐C3 78.74(5), C3‐P2‐C2 78.73(5), P1‐C2‐P2 100.90(6), P2‐C3‐P1 100.71(6).45

Conversely, the reaction of tBuCP with [(iPr2ImMe)Ni(CO)3] afforded a mixture of the mononuclear 1,3‐diphosphacyclobutadiene complex [(iPr2ImMe)Ni(CO)(η4‐P2C2 tBu2)] (5), the dinuclear complex [{(iPr2ImMe)Ni(CO)}2(μ,η2:η2‐tBuCP)] (6) and a tetranuclear cluster [{(iPr2ImMe)Ni2(CO)2(tBuCP)}2] (7, Figure 4 b). The three different species were identified in the 31P{1H} NMR spectrum and structurally authenticated by X‐ray diffraction experiments after fractional crystallization. Treatment of [(iPr2ImMe)Ni(CO)3] with just 0.5 or two equivalents of tBuCP resulted in similar mixtures. Upon addition of tBuCP to one equivalent of [Ni(CO)4], more than ten different species were detected by 31P{1H} NMR spectroscopy. The unselective nature of these reactions is in contrast to the selective formation of the η2‐bound phosphaalkyne complexes 4 a–d and presumably accounts for the lower yields in the catalytic formation of 1 a.

With a high‐yielding protocol for the preparation of 4 a in hand, the reactivity of this species was investigated. 4 a is the most potent catalyst for the dimerization of tBuCP among all nickel complexes investigated. Thus, a significantly shorter reaction time for full conversion of the phosphaalkyne is required with 4 a than with [(IMes)Ni(CO)3]. High temperature 31P{1H} NMR spectroscopic monitoring of this catalytic dimerization reaction revealed the presence of 4 a at a constant concentration throughout the whole reaction (see Supporting Information for further details). These observations suggest that 4 a is the resting state for the catalytic cycle. Further reaction intermediates were not detected by 31P{1H} NMR spectroscopy even upon monitoring the reaction at −80 °C. Also noteworthy is that treatment of 4 a with one equivalent AdCP affords the mixed‐substituted diphosphatetrahedrane (P2C2AdtBu, 1 c), which can be identified by a 31P{1H} NMR singlet at −473.8 ppm.

Kinetic analysis with 0.5 to 4 mol % of 4 a indicates a first‐order dependence of the dimerization reaction in both catalyst and phosphaalkyne. The proposed rate law is therefore [Eq. (1)]:

| (1) |

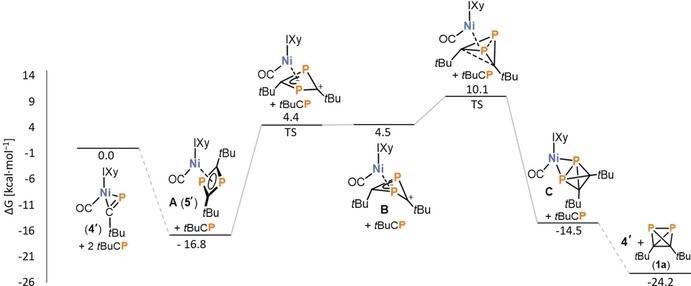

These results are in good agreement with DFT calculations performed on the TPSS‐D3BJ/def2‐TZVP level, which suggest that the reaction between the truncated model complex [(IXy)Ni(CO)(tBuCP)] (4′, IXy=1,3‐bis(2,6‐dimethylphenyl)imidazolin‐2‐ylidene) and a molecule of tBuCP initially affords the 1,3‐diphosphacyclobutadiene complex A (Figure 5, cf. complex 5, which differs only in the identity of NHC ligand; see Supporting Information for more details).44 However, A is not the global minimum of the potential hypersurface and transforms into an intermediate B showing an isomerized (tBuCP)2 ligand. In the next step, a diphosphatetrahedrane complex C is formed. The formation of C has a calculated activation barrier of 26.9 kcal mol−1 with respect to A. This is well in line with the reaction temperature of +60 °C required for the reaction to proceed at an appreciable rate (vide supra). Subsequent replacement of the diphosphatetrahedrane 1 a by another phosphaalkyne molecule is a downhill process and re‐forms the resting state 4′ (cf. complex 4, which is the only species we could identify by NMR spectroscopy in solution). Notably, a different scenario has been calculated for a further truncated model system consisting of Me‐C≡P and [(IPh)Ni(CO)(PCMe)], (IPh=1,3‐diphenylimidazolin‐2‐ylidene, see Supporting Information for further details). In this case, significant stabilization of the analogous 1,3‐diphosphacyclobutadiene complex (A′) is observed. The high activation barrier calculated for the transformation A′→C′ (49.8 kcal mol−1) precludes the formation of the diphosphatetrahedrane. It appears that the steric repulsion between bulky substituents on the NHC such as Mes and Dipp and the tBu groups has a destabilizing effect on A, and this destabilization of the 1,3‐diposphacyclobutadiene complex, which is usually a thermodynamic sink in other reactions,33 enables catalytic turnover in this particular case.

Figure 5.

Reaction profile calculated with DFT at the TPSS‐D3BJ/def2‐TZVP level for the dimerization of tBu‐C≡P catalyzed by [(IXy)Ni(PCtBu)] (IXy=1,3‐bis(2,6‐dimethylphenyl)imidazolin‐2‐ylidene) (4′). Calculated Gibbs energies (in kcal mol−1at 298 K) and schematic drawings of intermediates and transition states are given.

In conclusion, diphosphatetrahedranes (RCP)2 (R=tBu, Ad) have been synthesized by an unprecedented nickel(0)‐catalyzed dimerization reaction of the corresponding phosphaalkynes RCP. The tert‐butyl‐derivative (tBuCP)2 (1 a) is stable enough to be isolated and thoroughly characterized. The molecular structure of the silver(I) complex 3 confirms the tetrahedral structure of the molecule. 1 a is a very rare “mixed” tetrahedrane, which, moreover, represents the hitherto elusive free phosphaalkyne dimer. Its synthesis therefore closes a significant gap in phosphaalkyne oligomer chemistry. 1 a is a metastable compound that slowly converts to the ladderane 2 a. This reaction shows that such dimers are indeed intermediates in phosphaalkyne tetramerizations as proposed previously.25, 28 Synthetic, kinetic and computational investigations suggest that a 1,3‐diphosphacyclobutadiene complex is a key intermediate and that destabilization of this complex by steric repulsion is a crucial factor in achieving catalysis. We are currently exploring the further reactivity of the remarkable small molecule 1 a.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

Financial support by the European Research Council (CoG 772299) and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie (Kekulé fellowship for G. H.) is gratefully acknowledged. We thank the group of Prof. Manfred Scheer (Luis Dütsch and Martin Piesch) for the donation of [Ni(CO)4)] and [Ag(CH2Cl2)2(pftb)]. We also thank Jonas Strohmaier and Georgine Stühler for assistance, and Dr. Daniel Scott and Dr. Sebastian Bestgen for helpful comments on the manuscript.

G. Hierlmeier, P. Coburger, M. Bodensteiner, R. Wolf, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 16918.

References

- 1. Maier G., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1988, 27, 309–332; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 1988, 100, 317–341. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nemirowski A., Reisenauer H. P., Schreiner P. R., Chem. Eur. J. 2006, 12, 7411–7420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ivanov A. S., Bozhenko K. V., Boldyrev A. I., J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012, 8, 135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Haunschild R., Frenking G., Mol. Phys. 2009, 107, 911–922. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Höltzl T., Szieberth D., Nguyen M. T., Veszprémi T., Chem. Eur. J. 2006, 12, 8044–8055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maier G., Pfriem S., Schäfer U., Matusch R., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1978, 17, 520–521; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 1978, 90, 552–553. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sekiguchi A., Matsuo T., Watanabe H., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 5652–5653. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kobayashi Y., Nakamoto M., Inagaki Y., Sekiguchi A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 10740–10744; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2013, 125, 10940–10944. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Maier G., Neudert J., Wolf O., Pappusch D., Sekiguchi A., Tanaka M., Matsuo T., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 13819–13826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nakamoto M., Inagaki Y., Nishina M., Sekiguchi A., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 3172–3173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ochiai T., Nakamoto M., Inagaki Y., Sekiguchi A., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 11504–11507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sekiguchi A., Tanaka M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 12684–12685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tanaka M., Sekiguchi A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 5821–5823; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2005, 117, 5971–5973. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wiberg N., Finger C. M. M., Polborn K., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1993, 32, 1054–1056; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 1993, 105, 1140–1142. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Uhl W., Hiller W., Layh M., Schwarz W., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1992, 31, 1364–1366; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 1992, 104, 1378–1380. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mennekes T., Paetzold P., Boese R., Bläser D., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1991, 30, 173–175; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 1991, 103, 199–200. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dohmeier C., Robl C., Tacke M., Schnöckel H., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1991, 30, 564–565; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 1991, 103, 594–595. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Purath A., Dohmeier C., Ecker A., Schnöckel H., Amelunxen K., Passler T., Wiberg N., Organometallics 1998, 17, 1894–1896. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wiberg N., Amelunxen K., Lerner H.-W., Nötz H., Ponikwar W., Schwenk H., J. Organomet. Chem. 1999, 574, 246–251. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Uhl W., Jantschak A., Saak W., Kaupp M., Wartchow R., Organometallics 1998, 17, 5009–5017. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Uhl W., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1993, 32, 1386–1397; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 1993, 105, 1449–1461. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Note that SbP3, As2P2 and As3P were observed spectroscopically, see refs. [34] and [35].

- 23. Chirila A., Wolf R., Slootweg J. C., Lammertsma K., Coord. Chem. Rev. 2014, 270–271, 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- 24.A few metal-catalyzed phosphaalkyne oligomerizations are known, see ref. [23] for an overview. Grützmacher and co-workers reported the use of 10 mol % [(trop2NMeNi(PCPh3)}] (trop=5H-dibenzo[a,d]cyclohepten-5-yl) for the trimerization of Ph3C−C≡P to a Dewar-1,3,5-phosphabenzene, see ref. [43].

- 25. Geissler B., Barth S., Bergsträsser U., Slany M., Durkin J., Hitchcock P. B., Hofmann M., Binger P., Nixon J. F., von Ragué Schleyer R., Regitz M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1995, 34, 484–487; [Google Scholar]; von Ragué Schleyer R., Regitz M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1995, 34, 484–487; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 1995, 107, 485–488. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Binger P., Leininger S., Stannek J., Gabor B., Mynott R., Bruckmann J., Krüger C., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1995, 34, 2227–2230; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 1995, 107, 2411–2414. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bartsch R., Hitchcock P. B., Nixon J. F., J. Organomet. Chem. 1989, 375, C31–C34. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wettling T., Geissler B., Schneider R., Barth S., Binger P., Regitz M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1992, 31, 758–759; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 1992, 104, 761–762. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Caliman V., Hitchcock P. B., Nixon J. F., Hofmann M., von Ragué Schleyer P., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1994, 33, 2202–2204; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 1994, 106, 2284–2286. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Streubel R., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1995, 34, 436–438; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 1995, 107, 478–480. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wolf R., Ehlers A. W., Slootweg J. C., Lutz M., Gudat D., Hunger M., Spek A. L., Lammertsma K., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 4584–4587; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2008, 120, 4660–4663. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wolf R., Slootweg J. C., Ehlers A. W., Hartl F., de Bruin B., Lutz M., Spek A. L., Lammertsma K., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 3104–3107; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2009, 121, 3150–3153. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wolf R., Ghavtadze N., Weber K., Schnöckelborg E.-M., de Bruin B., Ehlers A. W., Lammertsma K., Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 1453–1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cossairt B. M., Diawara M.-C., Cummins C. C., Science 2009, 323, 602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cossairt B. M., Cummins C. C., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 15501–15511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cossairt B. M., Cummins C. C., Head A. R., Lichtenberger D. L., Berger R. J. F., Hayes S. A., Mitzel N. W., Wu G., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 8459–8465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Krossing I., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 4603–4604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schwarzmaier C., Sierka M., Scheer M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 858–861; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2013, 125, 891–894. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Repeated attempts to isolate the homoleptic complex [Ag(1 a)2][pftb] were unsuccessful due to thermal decomposition of 1 a in solution.

- 40. Irngartinger H., Goldmann A., Jahn R., Nixdorf M., Rodewald H., Maier G., Malsch K.-D., Emrich R., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1984, 23, 993–994; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 1984, 96, 967–968. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Due to the low solubility of 3 in CD2Cl2 and slow decomposition in solution, a 13C{1H} NMR spectrum could not be obtained.

- 42. Schaub T., Radius U., Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2006, 632, 981–984. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Trincado M., Rosenthal A. J., Vogt M., Grützmacher H., Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 1599–1604. [Google Scholar]

- 44.A possible second, yet kinetically disfavored pathway for the formation of 1 a is discussed in the Supporting Information.

- 45.CCDC https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/services/structures?id=doi:10.1002/anie.201910505 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary