Abstract

Nanostructured dopant-based silicon (Si) transistors are promising candidates for high-performance photodetectors and quantum information devices. For highly doped Si with donor bands, the energy depth of donor levels and the energy required for tunneling processes between donor levels are typically on the order of millielectron volts, corresponding to terahertz (THz) photon energy. Owing to these properties, highly doped Si quantum dots (QDs) are highly attractive as THz photoconductive detectors. Here, we demonstrate THz detection with a lithographically defined and highly phosphorus-doped Si QD. We integrate a 40 nm-diameter QD with a micrometer-scale broadband logarithmic spiral antenna for the detection of THz photocurrent in a wide frequency range from 0.58 to 3.11 THz. Furthermore, we confirm that the detection sensitivity is enhanced by a factor of ~880 compared to a QD detector without an antenna. These results demonstrate the ability of a highly doped-Si QD coupled with an antenna to detect broadband THz waves. By optimizing the dopant distribution and levels, further performance improvements are feasible.

Subject terms: Sensors, Quantum dots

Introduction

Doping technologies for semiconductors have a great potential for realizing new functional and high-performance photonic devices. Among the various properties created by dopants, robust quantum states formed by donor levels is one of the most interesting and important. One notable example involves nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond, which can lead to highly sensitive magnetic sensors and quantum information devices1. The use of dopant-assisted photoresponse in silicon (Si) nanodevices is emerging as a promising method for highly sensitive photodetection. Trapping and detrapping of electrons localized in the Si donor levels provides a polarization field, which strongly modifies the local electrostatic environment of percolation pathways in devices. These processes lead to the generation of observable currents, even under very weak light irradiation. By utilizing dopant-based Si nanotransistors, Tabe et al. observed single-electron transport through a single dopant2 and demonstrated highly sensitive photon detection in the visible light region3. In addition, microwave-induced currents have been observed through a doped Si QD channel4,5.

Dopant-based Si nanotransistors are opening up new possibilities for high-performance Si photonic devices in the terahertz (THz) regime. For highly doped Si with donor bands, the typical energy depths of individual donor levels are known to be of the order of millielectron volts (meV)2,4, which correspond to THz photon energies. Additionally, the neighboring tunneling processes between donor levels also correspond to similar energies4. These features provide THz-induced changes in percolation pathways in Si devices due to the modification of the electrostatic environment, leading to the generation of an observable photocurrent4,5. Furthermore, this phenomenon occurs because the current in nanostructures is dominated by a smaller number of percolation pathways compared to conventional microscale transistors. Therefore, a highly doped Si QD is appropriate for developing a THz photoconductive detector.

Technologies based on THz waves are becoming increasingly important because of their broad range of potential applications such as security screening, medical checks, and materials characterization6–8. Although THz generation and detection based on femtosecond pulse lasers are widely used, solid-state THz devices without pulse lasers are preferable and in demand for practical applications. At present, solid-state THz sources include quantum cascade lasers9, resonant tunneling-diode oscillators10,11, p-type germanium lasers12,13, and superconducting coherent emitters14,15. Recently, various nanostructured devices have been employed to enhance THz detector performance. To date, THz detectors with nanoscale devices based on compound semiconductors16, superconductors17,18, carbon nanotubes19–21, and graphene22–24 have been reported.

Si-based detectors are one of most reliable devices because they can be entirely fabricated using mature complementary metal-oxide semiconductor-compatible processes. In this paper, we report THz detection based on a lithographically defined and highly phosphorus-doped 40 nm diameter Si QD. One crucial issue concerning the application of such a nanoscale THz detector is that the nanoscale sensing area of a QD is much smaller than the wavelength of THz waves, generally resulting in low THz coupling efficiency. To overcome this problem, we directly integrated a Si QD with a micrometer-scale logarithmic-spiral (log-spiral) antenna25,26. We experimentally demonstrated that THz irradiation onto a dopant-based Si QD with a log-spiral antenna generated THz photocurrent in a wide frequency range from 0.58 to 3.11 THz. Furthermore, the detection sensitivity was enhanced by a factor of ~880 compared to a Si QD detector without an antenna.

Results and Discussion

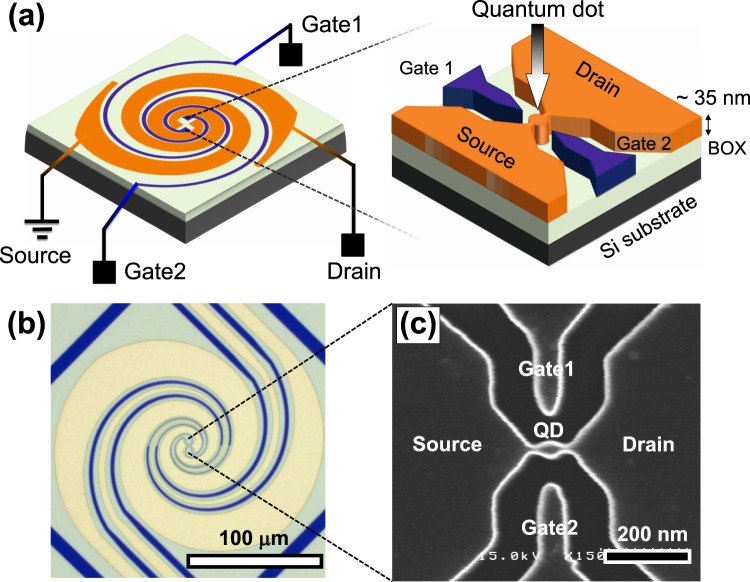

Our highly doped Si QD is depicted in Fig. 1(a), and the fabrication process is described in the Methods section. To efficiently concentrate THz waves on this 40-nm-diameter QD, we integrated a log-spiral antenna, which is a self-complementary broadband antenna25,26. An optical image of the device is shown in Fig. 1(b). Furthermore, we employed bowtie-shaped probes in the center of the log-spiral antenna that were connected to source and drain electrodes of the QD, as shown in the scanning electron microscopy image of the QD (Fig. 1(c)). The antenna was made of a Au (100 nm)/Cr (10 nm) film using an electron beam evaporator.

Figure 1.

Structure of the THz detector based on the antenna-coupled doped Si quantum dot. (a) Schematic of the device structure. (b) Optical image of an actual device. (c) Scanning electron microscopy image of the Si quantum dot located in the center.

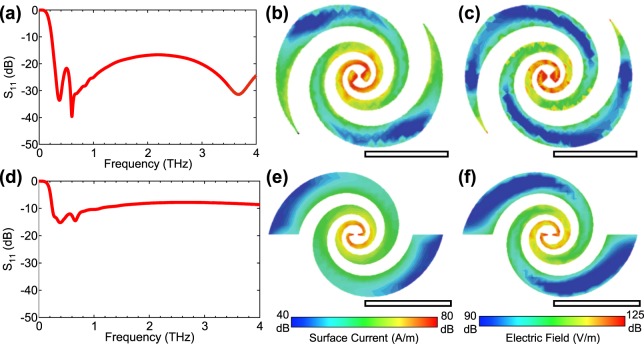

Figure 2(a) shows the S11 parameter of this antenna simulated using a finite integration technique (CST STUDIO) as a function of frequency. The result confirmed that the S11 parameter exhibited a smooth dependence in a wide frequency range. As shown in Fig. 2(b), the surface current density at 0.5 THz increased toward the center of the antenna because of the reduction in arm size. As a result, the electric fields on the antenna surface were strongly concentrated on the tips of the bowtie-shaped probe. These results indicate that the present structure can work as an antenna for wideband, high-efficiency THz detection with a nanoscale QD photodetector. Recently, this advantage was experimentally demonstrated with scattering-type scanning near-field optical microscopy in the mid-infrared region27.

Figure 2.

Numerical simulation of the log-spiral antenna with terminated arms (a–c) and with non-terminated arms (d–f) using a finite integration method. (a,d) S11 parameter versus frequency. (b,e) Distribution of surface current at 0.5 THz. (c,f) Distribution of electric field at 0.5 THz. The scale bars indicate 100 μm.

Ideally, a log-spiral antenna has infinitely extended structures25. Therefore, to investigate the impact of the arm termination, we performed similar simulations on the non-terminated antenna and plotted the results in Fig. 2(d). The S11 parameter increased significantly compared to the arm-terminated antenna. As shown in Fig. 2(d), the surface current distribution was similar to that of the arm-terminated antenna in the center region of the antenna. However, at the arm’s end, the current dropped abruptly as shown in Fig. 2(e), leading to reflections. In contrast, the arm termination allowed the current to decrease smoothly along the arms without abrupt drops, thereby reducing reflections and disturbances. Based on the above simulation results, we employed the arm-terminated log-spiral antenna depicted in Fig. 1(a).

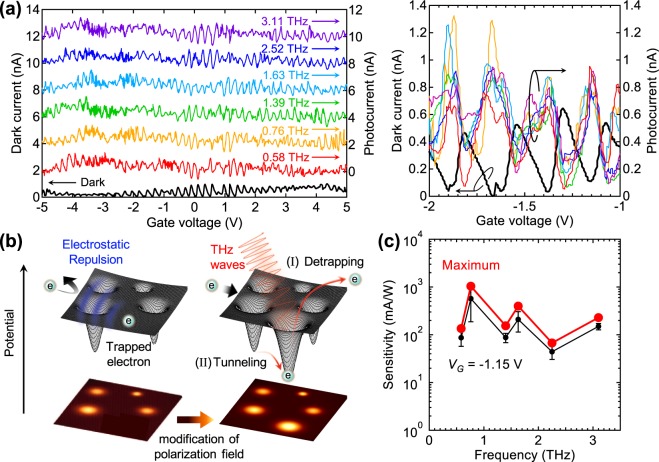

We measured the DC currents passing through the QD at a source–drain voltage of 5 mV and THz-induced photocurrent ITHz(f) = Iall(f) − I0, where I0 is the dark current without THz illumination and Iall(f) is the total current with THz illumination at a frequency of f. All measurements were performed at ~3 K (corresponding to 0.26 meV and 0.063 THz), as described in the Methods section. Figure 3(a) shows the dark current and the THz-induced photocurrent as functions of the gate voltage VG. Periodic dark current oscillations relative to VG (Coulomb oscillations) were observed, indicating that the QD operated as a single-electron transistor.

Figure 3.

THz response of the highly doped-Si QD with the antenna at six frequencies. (a) Dark current I0 (the dark curve) and THz photocurrent ITHz(f) (the other colored curves) at source–drain voltage of 5 mV. THz photocurrent depicted in left figure are offset by multiples of 2 nA. The right figure is smaller VG range. (b) Schematic view of the THz responses in the Coulomb blockade region; (I) detrapping process of the localized electron in donor levels; (II) THz-assisted tunneling process between the donor levels. These processes provide the modification of polarization field as shown in the bottom plains. (c) Frequency dependence of the maximum and VG-fixed sensitivity.

Interestingly, the THz photocurrent was mainly observed in the Coulomb blockade regions where electron tunneling was blocked as shown in the right panel of Fig. 3(a). Since its peak position relative to VG does not depend on the frequency of the illuminated THz waves, the THz photocurrent was not mainly caused by photon-assisted tunneling; this is due to the quantum level in zero-dimensional materials20,21,28. Here, we propose two mechanisms due to high doping for photocurrent generation in our device: (1) Detrapping processes from individual localized energy states created by the donor levels depicted as (I) in Fig. 3(b). This typical energy depth is known to be of the order of meV2,4, which corresponds to THz photon energy. Note that this energy depth effectively decreases compared to that of isolated donor (~45 meV of phosphorus), because the donor level broadens into bands29. (2) THz-assisted tunneling processes to empty donor levels4 depicted as (II) in Fig. 3(b). Both of these processes lead to a THz-induced polarization field and strongly modifies the local electrostatic environment of percolation pathways in the device, leading to the generation of observable photocurrent as theoretically shown in the Supplementary Information. Due to the confined electronic system of the QD with few percolation pathways, these pathways can be strongly modified further.

Figure 3(c) plots the maximum and VG-fixed detection sensitivity (i.e., THz photocurrent divided by the THz power onto the device) as a function of frequency. The VG-fixed sensitivity was determined by Lorentzian fitting at VG = −1.15 V. A smooth frequency dependence throughout the measured frequency range is clearly observed. This result confirms that the highly doped QD integrated with a log-spiral antenna can detect THz waves in a broad frequency region. This broadband response is attributed to both the broadband property of the antenna and the donor bands with the finite energy widths in the Si. THz detection in different or wider frequency regions are possible by adjusting the antenna parameters associated with cutoff frequencies. Considering the noise current density of this device (~10−13 A/Hz1/2), we roughly estimated that the noise equivalent power (NEP) is ~10−13 W/Hz1/2. We presume that the NEP is potentially lower, because the noise from the measuring system (e.g. the mechanical refrigerator) largely contributed to the noise value measured in this work.

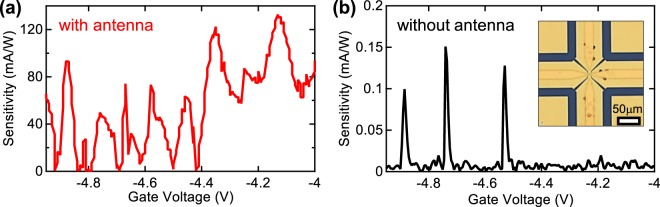

In order to verify the effect of the antenna, we made similar measurements of a QD device without an antenna. The non-antenna QD device was fabricated using the same processes used for the antenna-coupled QD device. Figure 4 compare the detection sensitivity between the two types of QD detectors at 3.11 THz. In Fig. 4, the maximum detection sensitivity of the antenna-coupled QD was 132.7 mA/W, whereas that of the non-antenna QD was 0.15 mA/W. Thus, the enhancement factor resulting from the presence of the log-spiral antenna was approximately 880. These results verify that the antenna efficiently focuses THz waves on the nanoscale QD photodetector.

Figure 4.

Detection sensitivity at 3.11 THz of the antenna-coupled QD (a) and the non-antenna-coupled QD (b). The inset in (b) shows an optical image of the non-antenna-coupled device.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated THz wideband detection using a highly doped Si QD device with a log-spiral antenna. The highly doped Si QD’s broadband capability is a result of both the dopant level and the log-spiral antenna’s broadband properties. It may possible to have an even more sensitive THz using the following two methods. One is by improving the read-out efficiency through the implementation of single-charge sensing with another single-electron transistor integrated in the proximity of the QD detector30 to enable the detection of THz photocurrent on the single-electron level. The other solution is by improving the quantum efficiency by sophisticated Si doping techniques such as deterministic doping31 to control the donor bands’ energy spread. In addition, by using a variety of donors and acceptors, it is possible to operate in a different bandwidth such as in the near-infrared range by using a deep level dopant (e.g., ~0.51 eV Ge-vacancy center as a donor32). An additional advantage of using Si nanotechnology is that arrayed Si-QD detectors are compatible with mature Si integrated circuit technologies for multiple signal processing and amplification techniques, which can then be applied to THz cameras in the future.

Methods

Sample fabrication

The THz detector was fabricated on a silicon-on-insulator (SOI) substrate. The QD structure and the log-spiral antenna were patterned using lithography. As illustrated in Fig. 1(a), the thickness of the Si layer in the SOI substrate was reduced to approximately 35 nm by thermal oxidation, contributing to the increase in the charging energy of the QD30. The QD, source, drain, and gate parts were doped via phosphine gas flow. The dopant concentration was 1 × 1019 cm−3.

Measurements

The temperature of the Si-QD THz detector was decreased to approximately 3 K using a mechanical refrigerator (NIKI GLASS Co., LTD). The electrical measurements were conducted using a voltage source (Hewlett-Packard Company, 3245 A), a voltage meter (Agilent Technologies International Japan, Ltd, 34401 A), and current amplifier. (DL Instruments, LLC, Model 1211). For measuring the THz photocurrent of the non-antenna-coupled device, the THz signal was further amplified by a lock-in amplifier (NF Corporation, LI5640) due to the very low signal, where the THz waves were chopped at 40 Hz.

We used a molecular gas laser pumped by a CO2 mid-infrared laser as a THz illumination source. The frequency of the THz source could be varied by either tuning the wavelength of the CO2 pump laser or changing the type of gas. In this experiment, six frequencies (0.58, 0.76, 1.39, 1.63, 2.52, and 3.11 THz) were used. The beam was focused and guided by an off-axis parabolic mirror through a silver-coated pipe (3 mm core and 1.2 m) and Tsurupica window (7 mm thickness) at room temperature and filtered by a black-polyethylene film at low temperature. The transmission factors were estimated to be ~0.7 for the silver-coated pipe, ~0.6 for the Tsurupica window, and 0.4 for the black-polyethylene film using a power meter (Ophir Optronics, NOVA II). The THz power onto the devices was derived to be several tens of nW, where the effective photoactive area was approximated as a square of the THz wavelength.

The sensitivity was derived by dividing the THz photocurrent by the THz power onto the detector. The NEP was calculated to be noise current density (in A/Hz1/2)/sensitivity (in A/W), where the noise current density was estimated in the Coulomb blockade region.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the JST-Mirai Program and the Center of Innovation Program from the Japan Science and Technology Agency, JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP17K19026, JP17H02730, JP16H00798, JP16H00906, JP18H03766, JP19H04539, JP19K22099 and JP19H02199 from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, and Support for Tokyo Tech Advanced Researchers (STAR).

Author contributions

T.O. wrote the manuscript, and performed data processing, analysis, and theoretical modeling. N.F. conducted the experiments. L.C. performed the simulations. All these works were performed in consultation with Y.K. and T.K. Y.K. helped in the discussion and revision of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-54130-0.

References

- 1.Aharonovich I, Greentree AD, Prawer S. Diamond photonics. Nat. Photonics. 2011;5:397. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2011.54. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tabe M, et al. Single-electron transport through single dopants in a dopant-rich environment. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010;105:016803. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.016803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tabe M, Udhiarto A, Moraru D, Mizuno T. Single-photon detection by Si single-electron FETs. Phys. Status Solidi A. 2011;208:646. doi: 10.1002/pssa.201000385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Creswell LA, Hasko DG, Williams DA. Microwave excitation of localized electrons in phosphorus-doped silicon single electron transistors. J. Appl. Phys. 2009;105:104508. doi: 10.1063/1.3129714. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rossi A, Hasko DG. Microwave-assisted transport via localized stated in degenerately doped Si single electron transistors. J. Appl. Phys. 2010;108:034509. doi: 10.1063/1.3467963. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferguson B, Zhang X-C. Materials for terahertz science and technology. Nat. Mater. 2002;1:26. doi: 10.1038/nmat708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tonouchi M. Cutting-edge terahertz technology. Nat Photonics. 2007;1:97. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2007.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawano Y. Terahertz Waves: A tool for Condensed Matter, the Life Sciences and Astronomy. Contemporary Physics. 2013;54:143. doi: 10.1080/00107514.2013.817194. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams BS. Terahertz quantum-cascade lasers. Nature Photonics. 2007;1:517. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2007.166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanaya H, Shibayama H, Sogabe R, Suzuki S, Asada M. Fundamental Oscillation up to 1.31 THz in Resonant Tunneling Diodes with Thin Well and Barriers. Appl. Phys. Express. 2012;5:124101. doi: 10.1143/APEX.5.124101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki S, Shiraishi M, Shibayama H, Asada M. High-Power Operation of Terahertz Oscillators with Resonant Tunneling Diodes Using Impedance-Matched Antennas and Array Configuration. IEEE J. Selected Topics Quantum Electron. 2013;19:8500108. doi: 10.1109/JSTQE.2012.2215017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Komiyama S. Far-Infrared Emission from Population-Inverted Hot-Carrier System in p -Ge. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1982;48:297. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.48.271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andronov AA. Hot electrons in semiconductors and submillimeter waves. Sov. Phys. Semicond. 1987;21:701. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ozyuzer L, et al. Emission of Coherent THz Radiation from Superconductors. Science. 2007;318:1291. doi: 10.1126/science.1149802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsujimoto M, et al. Broadly Tunable Subterahertz Emission from Internal Branches of the Current-Voltage Characteristics of Superconducting Bi2 Sr2 CaCu2 O8+δ Single Crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012;108:107006. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.107006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Komiyama S, Astafiev O, Antonov V, Hirai H, Kutsuwa T. A. single-photon detector in the far-infrared range. Nature. 2000;403:405. doi: 10.1038/35000166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ariyoshi S, et al. Terahertz imaging with a direct detector based on superconducting tunnel junctions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006;88:203503. doi: 10.1063/1.2204842. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei J, et al. Ultrasensitive hot-electron nanobolometers for terahertz astrophysics. Nature Nanotechnology. 2008;3:496. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fu K, et al. Terahertz detection in single wall carbon nanotubes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008;92:033105. doi: 10.1063/1.2837188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawano Y, Fuse T, Toyokawa S, Uchida T, Ishibashi K. Terahertz photon-assisted tunneling in carbon nanotube quantum dots. J. Appl. Phys. 2008;103:034307. doi: 10.1063/1.2838237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rinzan M, Jenkins G, Drew HD, Shanfranjuk S, Barbara P. Carbon Nanotube Quantum Dots As Highly Sensitive Terahertz-Cooled Spectrometers. Nano Lett. 2012;12(6):3097. doi: 10.1021/nl300975h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawano Y. Wide-band frequency-tunable terahertz and infrared detection with graphene. Nanotechnology. 2013;24:214004. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/24/21/214004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tong J, Muthee M, Chen S-Y, Yngvesson SK, Yan J. Antenna Enhanced Graphene THz Emitter and Detector. Nano Lett. 2015;15:5295. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b01635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fatimy AE, et al. Epitaxial graphene quantum dots for high-performance terahertz bolometers. Nature Nanotechnology. 2016;11.4:335. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2015.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rumsey, V. H. Frequency Independent Antennas (Academic Press, New York, 1966).

- 26.Mushiake Y. Self-complementary antennas. IEEE Antennas Propag. Mag. 1992;34.6:23. doi: 10.1109/74.180638. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okamoto T, Sugaya T, Fujimura N, Ishikawa K, Kawano Y. Near-field infrared investigations of an arm-terminated spiral structure with bow-tie probe. J. Phys. Commun. 2018;2.10:105004. doi: 10.1088/2399-6528/aadec3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kouwenhoven LP, et al. Observation of Photon-Assisted Tunneling through a Quantum Dot. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1994;73:3443. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.73.3443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taur Y, Ning HT. Fundamentals of Modern VLSI Devices. New York: Cambridge Univ. Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horibe K, Kodera T, Oda S. Lithographically-defined few-electron silicon quantum dots based on a silicon-on-insulator substrate. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015;106:083111. doi: 10.1063/1.4913321. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shinada, A. Okamoto, S., Kobayashi, T. & Ohdomari, I. Enhancing semiconductor device performance using ordered dopant arrays. Nature437.7062, 1128 (2005) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Achilli S, et al. GeVn complexes for silicon-based room-temperature single-atom nanoelectronics. Sci. Rep. 2018;8(1):18054. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-36441-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.