Abstract

Background

Ustekinumab and briakinumab are monoclonal antibodies that target the standard p40 subunit of cytokines interleukin‐12 and interleukin‐23 (IL‐12/23p40), which are involved in the pathogenesis of Crohn's disease (CD). A significant proportion of people with Crohn's disease fail conventional therapy or therapy with biologics (e.g. infliximab) or develop significant adverse events. Anti‐IL‐12/23p40 antibodies such as ustekinumab may be an effective alternative for these individuals.

Objectives

The objectives of this review were to assess the efficacy and safety of anti‐IL‐12/23p40 antibodies for maintenance of remission in CD.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane IBD Group Specialized Register, CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, and trials registers from inception to 17 September 2019. We searched references and conference abstracts for additional studies.

Selection criteria

We considered for inclusion randomized controlled trials in which monoclonal antibodies against IL‐12/23p40 were compared to placebo or another active comparator in participants with quiescent CD.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened studies for inclusion, extracted data, and assessed bias using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool. The primary outcome measure was failure to maintain clinical remission, defined as a Crohn's disease activity index (CDAI) of < 150 points. Secondary outcomes included failure to maintain clinical response, adverse events (AE), serious adverse events (SAE), and withdrawals due to AEs. Clinical response was defined as a decrease in CDAI score of ≥ 100 points from baseline score. We calculated the risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for each outcome. We analyzed all data on an intention‐to‐treat basis. We used GRADE to evaluate the overall certainty of the evidence supporting the outcomes.

Main results

Three randomized controlled trials (646 participants) met the inclusion criteria. Two trials assessed the efficacy of ustekinumab (542 participants), and one study assessed the efficacy of briakinumab (104 participants). We assessed all of the included studies as at low risk of bias.

One study (N = 145) compared subcutaneous ustekinumab (90 mg) administered at 8 and 16 weeks compared to placebo. Fifty‐eight per cent (42/72) of ustekinumab participants failed to maintain clinical remission at 22 weeks compared to 73% (53/73) of placebo participants (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.02; moderate‐certainty evidence). Failure to maintain clinical response at 22 weeks was seen in 31% (22/72) of ustekinumab participants compared to 58% (42/73) of placebo participants (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.79; moderate‐certainty evidence). One study (N = 388) compared subcutaneous ustekinumab (90 mg) administered every 8 weeks or every 12 weeks to placebo for 44 weeks. Forty‐nine per cent (126/257) of ustekinumab participants failed to maintain clinical remission at 44 weeks compared to 64% (84/131) of placebo participants (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.91; moderate‐certainty evidence). Forty‐one per cent (106/257) of ustekinumab participants failed to maintain clinical response at 44 weeks compared to 56% (73/131) of placebo participants (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.60 to 0.91; moderate‐certainty evidence). Eighty per cent (267/335) of ustekinumab participants had an AE compared to 84% (173/206) of placebo participants (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.03; high‐certainty evidence). Commonly reported adverse events included infections, injection site reactions, CD event, abdominal pain, nausea, arthralgia, and headache. Eleven per cent of ustekinumab participants had an SAE compared to 16% (32/206) of placebo participants (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.48 to 1.15; moderate‐certainty evidence). SAEs included serious infections, malignant neoplasm, and basal cell carcinoma. Seven per cent (5/73) of ustekinumab participants withdrew from the study due to an AE compared to 1% (1/72) of placebo participants (RR 4.93, 95% CI 0.59 to 41.18; low‐certainty evidence). Worsening CD was the most common reason for withdrawal due to an AE.

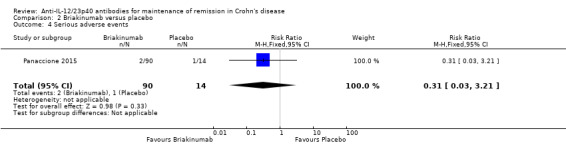

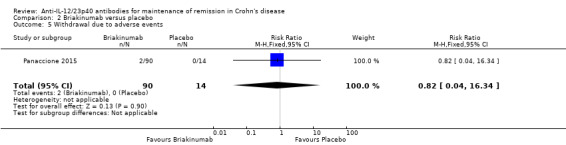

One study compared intravenous briakinumab (200 mg, 400 mg, or 700 mg) administered at weeks 12, 16, and 20 with placebo. Failure to maintain clinical remission at 24 weeks was seen in 51% (32/63) of briakinumab participants compared to 61% (22/36) of placebo participants (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.20; low‐certainty evidence). Failure to maintain clinical response at 24 weeks was seen in 33% (21/63) of briakinumab participants compared to 53% (19/36) of placebo participants (RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.40 to 1.02; low‐certainty evidence). Sixty‐six per cent (59/90) of briakinumab participants had an AE compared to 64% (9/14) of placebo participants (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.55; low‐certainty evidence). Common AEs included upper respiratory tract infection, nausea, abdominal pain, headache, and injection site reaction. Two per cent (2/90) of briakinumab participants had an SAE compared to 7% (1/14) of placebo participants (RR 0.31, 95% CI 0.03 to 3.21; low‐certainty evidence). SAEs included small bowel obstruction, deep vein thrombosis, and respiratory distress. Withdrawal due to an AE was noted in 2% of briakinumab participants compared to 0% (0/14) of placebo participants (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.04 to 16.34; low‐certainty evidence). The AEs leading to study withdrawal were not described.

Authors' conclusions

Moderate‐certainty evidence suggests that ustekinumab is probably effective for the maintenance of clinical remission and response in people with moderate to severe CD in remission without an increased risk of adverse events (high‐certainty evidence) or serious adverse events (moderate‐certainty evidence) relative to placebo. The effect of briakinumab on maintenance of clinical remission and response in people with moderate to severe Crohn's disease in remission was uncertain as the certainty of the evidence was low. The effect of briakinumab on adverse events and serious adverse events was also uncertain due to low‐certainty evidence. Further studies are required to determine the long‐term efficacy and safety of subcutaneous ustekinumab maintenance therapy in Crohn's disease and whether it should be used by itself or in combination with other agents. Future research comparing ustekinumab with other biologic medications will help to determine when treatment with ustekinumab in CD is most appropriate. Currently, there is an ongoing study that compares ustekinumab with adalimumab. This review will be updated when the results of this study become available. The manufacturers of briakinumab have stopped production of this medication, thus further studies of briakinumab are unlikely.

Keywords: Humans; Antibodies, Monoclonal, Humanized; Antibodies, Monoclonal, Humanized/therapeutic use; Crohn Disease; Crohn Disease/therapy; Interleukin‐12; Interleukin‐12/antagonists & inhibitors; Interleukin‐12/immunology; Interleukin‐23; Interleukin‐23/antagonists & inhibitors; Interleukin‐23/immunology; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Remission Induction; Remission Induction/methods; Ustekinumab; Ustekinumab/therapeutic use

Plain language summary

Ustekinumab and briakinumab for the treatment of inactive Crohn's disease

What is Crohn's disease?

Crohn's disease is a long‐term (chronic) inflammatory bowel disease that can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract from the mouth to the anus. Common symptoms include abdominal pain, diarrhea, and weight loss. Crohn's disease is usually managed through medical and surgical therapies. When a person with Crohn's disease is experiencing symptoms, the disease is ‘active’. When symptoms of Crohn's disease disappear, the disease is said to be in remission.

What are ustekinumab and briakinumab?

Ustekinumab and briakinumab are biologic medications, which suppress the immune system and reduce the inflammation associated with Crohn's disease. They can be injected under the skin using a syringe (subcutaneous) or directly infused into a vein (intravenous). Many people with Crohn's disease fail conventional therapy with steroids or therapy with biologics (e.g. infliximab) or develop significant side effects. A drug such as ustekinumab may be an effective alternative for these individuals.

What did the research investigate?

The researchers investigated whether ustekinumab or briakinumab helps maintain remission in people with Crohn's disease and whether these medications have harmful effects (side effects). The researchers searched the medical literature up to 17 September 2019.

What did the researchers find?

The researchers identified 3 studies (646 participants) that compared ustekinumab (2 studies, 542 participants) or briakinumab (1 study, 104 participants) to a placebo (a fake medicine). The treatment effect of ustekinumab was examined in one study after 22 weeks and another study after 44 weeks. The study of briakinumab examined the treatment effect after 24 weeks. All studies were of high methodological quality.

Moderate‐certainty evidence suggests that ustekinumab is more effective than placebo at maintaining remission and reducing symptoms of Crohn's disease at 22 and 44 weeks. The rates of side effects (ustekinumab: 80%; placebo: 84%) and serious side effects (ustekinumab: 11%; placebo: 16%) were lower in ustekinumab participants than in placebo participants. High‐certainty evidence suggests there is no increased risk of side effects with ustekinumab compared to placebo. Commonly reported side effects included infections, injection site reactions, Crohn's disease event (e.g. disease worsening), abdominal pain, nausea, arthralgia (i.e. joint pain), and headache. Moderate‐certainty evidence suggests there is no increased risk of serious side effects with ustekinumab compared to placebo. Serious side effects included serious infections, malignant neoplasm (i.e. a cancerous tumor), and basal cell carcinoma (i.e. skin cancer). In one study, more ustekinumab participants (7%) withdrew from the study due to a side effect than placebo participants (1%). However, the certainty of the evidence was low. The most common side effect leading to study withdrawal was worsening Crohn's disease.

Fifty‐one per cent (32/63) of briakinumab participants relapsed at 24 weeks compared to 61% (22/36) of placebo participants (low‐certainty evidence). The proportion of participants without a reduction in Crohn's disease symptoms at 24 weeks was 33% (21/63) in the briakinumab group compared to 53% (19/36) in the placebo group (low‐certainty evidence). The rates of side effects (briakinumab: 66%; placebo: 64%; low‐certainty evidence) and study withdrawal due to side effects (briakinumab: 2%; placebo: 0%; low‐certainty evidence) were comparable in briakinumab and placebo participants. Commonly reported side effects included upper respiratory tract infection, nausea, abdominal pain, headache, and injection site reaction. The rate of serious side effects was lower in briakinumab participants (2%) compared to placebo participants (7%) (low‐certainty evidence). Serious side effects included small bowel obstruction, deep vein thrombosis, and respiratory distress.

Conclusions

Moderate‐certainty evidence suggests that ustekinumab is probably effective for the maintenance of clinical remission and response in people with moderate to severe Crohn's disease in remission without an increased risk of side effects (high‐certainty evidence) or serious side effects (moderate‐certainty evidence). Further studies are required to determine the long‐term benefits and harms of subcutaneous ustekinumab maintenance therapy in Crohn's disease and whether it should be used alone or in combination with other agents. Future research comparing ustekinumab with other biologic medications will help to determine when treatment with ustekinumab in Crohn's disease is most appropriate. Currently, there is an ongoing study that compares ustekinumab with adalimumab (another type of biologic medication). The manufacturers of briakinumab have stopped production of this medication, thus further studies of briakinumab are unlikely.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Ustekinumab compared to placebo for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease.

| Ustekinumab compared to placebo for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with moderate to severe Crohn's disease in remission Setting: outpatient Intervention: ustekinumab Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with ustekinumab | |||||

|

Failure to maintain clinical remission Follow‐up: 22 weeks |

726 per 1000 | 581 per 1000 (457 to 741) | RR 0.80 (0.63 to 1.02) | 145 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | Clinical remission was defined as a CDAI < 150 points. |

|

Failure to maintain clinical response Follow‐up: 22 weeks |

575 per 1000 | 305 per 1000 (207 to 455) | RR 0.53 (0.36 to 0.79) | 145 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | Clinical response was defined as a ≥ 100‐point decrease from the baseline CDAI score. |

|

Failure to maintain clinical remission Follow‐up: 44 weeks |

641 per 1000 |

487 per 1000 (410 to 584) |

RR 0.76 (0.64 to 0.91) |

388 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate3 | Clinical remission was defined as a CDAI < 150 points. |

|

Failure to maintain clinical response Follow‐up: 44 weeks |

557 per 1000 |

412 per 1000 (334 to 507) |

RR 0.74 (0.60 to 0.91) |

388 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate4 | Clinical response was defined as a decrease from baseline in the CDAI score of ≥ 100 points or a CDAI score < 150. |

|

Adverse events Follow‐up: 44 weeks |

840 per 1000 |

789 per 1000 (731 to 865) |

RR 0.94 (0.87 to 1.03) |

541 (2 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | Commonly reported adverse events included worsening Crohn's disease, abdominal pain, nausea, arthralgia, and headache. |

|

Serious adverse events Follow‐up: 44 weeks |

155 per 1000 | 115 per 1000 (75 to 179) | RR 0.74 (0.48 to 1.15) | 541 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate5 | Commonly reported serious adverse events included malignant neoplasm, basal cell carcinoma, and injection site reactions. |

|

Withdrawal due to adverse events Follow‐up: 44 weeks |

14 per 1000 |

68 per 1000 (8 to 572) |

RR 4.93 (0.59 to 41.18) |

145 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low6 | Adverse events leading to withdrawal included worsening Crohn's disease |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CDAI: Crohn's Disease Activity Index; CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1Downgraded one level due to sparse data (95 events). 2Downgraded one level due to sparse data (64 events). 3Downgraded one level due to sparse data (210 events). 4Downgraded one level due to sparse data (179 events). 5Downgraded one level due to sparse data (70 events). 6Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (6 events).

Summary of findings 2. Briakinumab compared to placebo for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease.

| Briakinumab compared to placebo for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with moderate to severe Crohn's disease in remission Setting: outpatient Intervention: briakinumab Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo | Risk with briakinumab | |||||

|

Failure to maintain clinical remission Follow‐up: 24 weeks |

611 per 1000 |

513 per 1000 (354 to 733) |

RR 0.84 (0.58 to 1.20) |

99 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | Clinical remission was defined as a CDAI score < 150 points. |

|

Failure to maintain clinical response Follow‐up: 24 weeks |

528 per 1000 |

338 per 1000 (211 to 538) |

RR 0.64 (0.40 to 1.02) |

99 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2 | Clinical response was defined as a decrease in CDAI score ≥ 100 points compared with week 0. |

|

Adverse events Follow‐up: 24 weeks |

643 per 1000 |

656 per 1000 (431 to 996) |

RR 1.02 (0.67 to 1.55) |

104 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3 | Common adverse events included upper respiratory tract infection, nausea, abdominal pain, and headache. |

|

Serious adverse events Follow‐up: 24 weeks |

71 per 1000 |

22 per 1000 (2 to 229) |

RR 0.31 (0.03 to 3.21) |

104 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low4 | Serious adverse events included small bowel obstruction, deep vein thrombosis, and respiratory distress. |

|

Withdrawals due to adverse events Follow‐up: 24 weeks |

0 per 1000 |

0 per 1000 (0 to 0) |

RR 0.82 (0.04 to 16.34) |

104 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low5 | We were unable to calculate absolute effects. 2% of briakinumab participants withdrew due to an adverse event compared to none of the placebo participants. Adverse events leading to withdrawal were not reported. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CDAI: Crohn's Disease Activity Index; CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

1Downgraded two levels due to sparse data (54 events) and very wide confidence interval. 2Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (40 events). 3Downgraded two levels due to sparse data (68 events) and very wide confidence interval. 4Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (3 events). 5Downgraded two levels due to very sparse data (2 events).

Background

Description of the condition

Crohn's disease is a chronic, relapsing and remitting, inflammatory condition that results in abdominal pain, diarrhea, and weight loss. Despite highly effective therapies, up to one‐third of people with Crohn's disease develop fistulas or require surgery for disease complications (CCC 2018). Additionally, many of the current therapies are encumbered by unexpected adverse events (Colombel 2004; Colombel 2007; Ford 2011; Raj 2010; Schreiber 2007; Singh 2011; Yang 2002). Given that approximately 40% of patients do not respond to conventional agents such as corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, and biologics (e.g. infliximab), the development of new therapies is a priority for clinical practice (Danese 2011; Hanauer 2002; Hanauer 2006; Targan 1997).

Monoclonal antibodies against tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF‐α) are commonly used for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease. However, it is estimated that 25% to 40% of patients receiving TNF‐α antagonists who initially benefit from treatment either lose response or are forced to stop treatment due to intolerable adverse events during the maintenance phase (Danese 2011). Although some patients regain response with an increase in dose, a significant proportion of these individuals experience a relapse of their Crohn's disease due to non‐TNF‐α driven inflammatory pathways (Steenholdt 2016). In such cases continued anti‐TNF‐α treatment would be ineffective and other therapies are needed.

Description of the intervention

Ustekinumab (CNTO 1275) and briakinumab (ABT‐874) are monoclonal antibodies directed against the shared p40 subunit of interleukin‐12 and interleukin‐23 (IL‐12/23p40). Inhibition of these cytokines is beneficial for induction of remission in Crohn's disease (Feagan 2016).

How the intervention might work

Pathogenic immune responses in Crohn’s disease are characterized by dysregulated T‐cell activity stimulated by the release of interleukin‐12 (IL‐12) and IL‐23 by antigen‐presenting cells (Benson 2011a; Duvallet 2011; Peluso 2006; Watanabe 2004). IL‐12 promotes differentiation of naive T‐cells down the Th1 pathway (Xavier 2007), whereas IL‐23 stimulates proliferation of Th17 lymphocytes. Activation of the Th1 pathway culminates in the release of interferon (IFN)‐ɣ and TNF‐α (Benson 2011b; Cingoz 2009; Peluso 2006), two cytokines that have been implicated in the pathogenesis of Crohn's disease. In contrast, Th17 is important in maintaining many chronic inflammatory conditions (Duvallet 2011).

In murine models, inhibition of IL‐12/23p40 results in apoptosis of T cells in the gut mucosa (Fuss 1999), which results in disease improvement (Neurath 1995). Collectively, these data suggest a possible therapeutic role for ustekinumab in the treatment of Crohn’s disease.

Why it is important to do this review

Ustekinumab is widely used for the treatment of psoriasis where it has demonstrated safety and efficacy (Papp 2008). The safety and efficacy of ustekinumab has been established for induction of remission in Crohn's disease (MacDonald 2016). However, the benefits and harms of this therapy for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease have not been systematically assessed.

Objectives

The objectives of this review were to assess the efficacy and safety of anti‐IL‐12/23p40 antibodies for maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered randomized controlled trials for inclusion in the review.

Types of participants

We considered participants with quiescent Crohn's disease (as defined by the original study) for inclusion. We applied no age restrictions.

Types of interventions

We considered trials comparing monoclonal antibodies against IL‐12/23p40 to placebo or an active comparator for inclusion.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Proportion of participants who failed to maintain clinical remission (as defined by the original study).

Secondary outcomes

The proportion of participants:

who failed to maintain clinical response (as defined by the original study);

who failed to maintain endoscopic response (as defined by the original study);

who failed to maintain endoscopic remission (as defined by the original study);

who failed to maintain histological response (as defined by the original study);

who failed to maintain histological remission (as defined by the original study);

who failed to maintain both clinical and endoscopic response (as defined by the original study);

who failed to maintain both clinical and endoscopic remission (as defined by the original study);

with adverse events;

with serious adverse events; and

who withdrew from the study due to adverse events.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases for relevant studies:

the Cochrane IBD Group Specialized Register (searched 17 September 2019);

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (searched 17 September 2019);

MEDLINE (Ovid, 1946 to 17 September 2019); and

Embase (Ovid, 1984 to 17 September 2019).

The search strategies are listed in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We also searched the references of relevant trials and review articles for additional studies not identified by the search. Furthermore, we searched conference proceedings from major meetings including Digestive Disease Week, the European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation congress, and the United European Gastroenterology Week for the last five years (2013 to 2017) to identify studies published in abstract form only. We contacted leaders in the field and the manufacturers of briakinumab and ustekinumab (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA and Centocor, Horsham, PA, USA) to identify any unpublished studies.

Lastly, to identify ongoing trials, we searched trials registers including:

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov; searched 17 September 2019);

International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations (www.ifpma.org; searched 17 September 2019); and

ISRCTN registry (www.isrctn.com; searched 17 September 2019).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (SCD and TMN) screened the search results independently for eligible studies based on the described inclusion criteria. Any disagreements were discussed until a consensus was reached or by consulting a third review author (RK) when necessary.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (SCD and TMN) independently extracted data from the included studies. Any disagreements regarding the extracted data were first discussed and then brought to a third review author (RK) for resolution as required. If the case of missing data, we contacted the study authors for additional information.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (SCD and TMN) assessed the methodological quality of the included studies using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2011). We assessed factors pertaining to the methodological quality of the study including sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other potential sources of bias. We judged studies to be at low, high, or unclear risk of bias. Any disagreements regarding risk of bias were first discussed and then brought to a third review author (RK) for resolution as required.

We used the GRADE approach to determine the overall certainty of evidence supporting the following outcomes: failure to maintain clinical remission, failure to maintain clinical response, adverse events, serious adverse events, and withdrawal due to adverse events (Schünemann 2011). We considered evidence that was extracted from randomized controlled trials to be of high certainty. The certainty of the evidence could be downgraded due to the following factors:

risk of bias;

indirect evidence;

inconsistency (unexplained heterogeneity);

imprecision; and

publication bias.

We classified the overall certainty of the evidence as high (we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect); moderate (we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.); low (our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect); or very low (we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect) (Guyatt 2008).

Measures of treatment effect

We used Review Manager 5 to analyze the data on an intention‐to‐treat basis (Review Manager 2014). We calculated the risk ratio (RR) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for dichotomous outcomes. We planned to calculate the mean difference (MD) and corresponding 95% CI for continuous outcomes.

Unit of analysis issues

For outcomes measured at different time points, we determined the appropriate fixed intervals for the follow‐up for each outcome. We included cross‐over trials if data were available for the first phase of the trial prior to cross‐over. We performed separate comparisons for each type of antibody and for each antibody in the context of other therapies. For reoccurring events (e.g. adverse events), we reported on the proportion of participants who experienced at least one event. If we encountered multiple drug dose groups, we divided the placebo group across the dose groups to avoid a unit of analysis error. We did not encounter any cluster‐randomized trials.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the authors of the original study if any data were missing. Additionally, participants without treatment outcomes were presumed to be treatment failures. We performed a sensitivity analysis to assess the impact of this assumption on the effect estimate if deemed appropriate.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity using the Chi² test (a P value of 0.10 was considered statistically significant) and the I² statistic. For the I² statistic, 75% indicated high heterogeneity among study data, 50% moderate heterogeneity, and 25% low heterogeneity (Higgins 2003). We conducted sensitivity analysis to explore possible explanations for heterogeneity as appropriate.

Assessment of reporting biases

To assess potential reporting biases, we compared outcomes listed in the study protocol to those outcomes reported in the published manuscript. If we did not have access to the protocol, we compared the outcomes listed in the methods section of the published manuscript with the outcomes reported in the published manuscript. We planned to investigate potential publication bias using funnel plots if a sufficient number of studies (≥ 10) were pooled for meta‐analysis (Egger 1997).

Data synthesis

We combined data from individual trials for meta‐analysis when the interventions, patient groups, and outcomes were similar as deemed by author consensus. We calculated the pooled RR and 95% CI for dichotomous outcomes. Additionally, we planned to calculate the pooled MD and 95% CI for any continuous outcomes. We used a fixed‐effect model to pool data unless there was heterogeneity among the studies (I² of 50% to 75%), in which case we used a random‐effects model. We did not pool data for meta‐analysis if a high degree of heterogeneity (I² ≥ 75%) was found.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We performed a subgroup analysis for different drug doses.

Sensitivity analysis

We used a sensitivity analysis to determine the impact of random‐effects and fixed‐effect modelling, risk of bias, type of report (full manuscript, abstract, or unpublished data), and loss to follow‐up on the pooled effect estimate.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

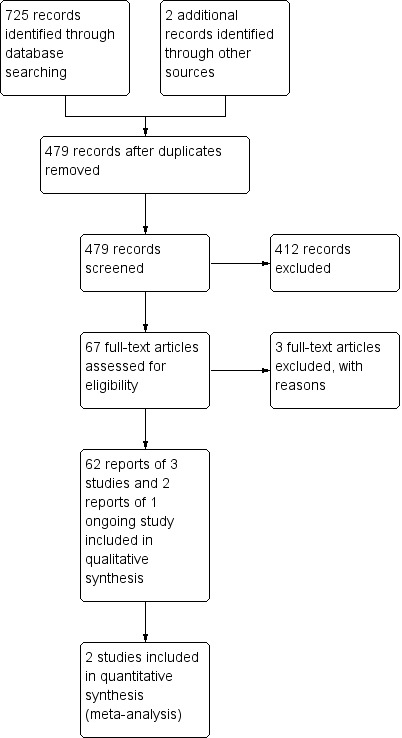

The literature search conducted on 17 September 2019 identified 725 records, and an additional two records were identified through other sources (See Figure 1). After removal of duplicates, 479 records remained for screening. Of these, 67 records were selected for full‐text review. Three studies were excluded after reviewing the full text (see Characteristics of excluded studies tables). Sixty‐two reports of 3 studies (646 participants) met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review (Feagan 2016; Panaccione 2015; Sandborn 2012).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

This study assessed ustekinumab in two populations (UNITI‐1 and UNITI‐2) with moderate to severe Crohn's disease. Adults (≥ 18 years) who had Crohn's disease for at least three months and a Crohn's Disease Activity Index (CDAI) score of 220 to 450 were enrolled in the induction trials. For the UNITI‐1 study, participants were required to have received one or more TNF‐α antagonists at approved doses and to have met the criteria for primary non‐response or secondary non‐response or to have experienced any unacceptable adverse effects. For the UNITI‐2 study, participants were required to have had treatment failure or unacceptable adverse effects when treated with immunosuppressants or glucocorticosteroids. Participants could have previously received one or more TNF‐α antagonists if they did not experience any unacceptable adverse effects and did not meet the criteria for primary or secondary non‐response to treatment. The primary outcome for both the UNITI‐1 and UNITI‐2 induction trials was clinical response at week 6 (decrease from baseline in CDAI score of at least 100 points or a total CDAI score of less than 150). Secondary endpoints included clinical remission at week 8 (CDAI < 150), clinical response at week 8, and a decrease from baseline in CDAI score of at least 70 points at weeks 3 and 6.

In the IM‐UNITI trial (N = 397) participants who responded to ustekinumab during the induction studies were randomly assigned to receive subcutaneous maintenance injections of 90 mg of ustekinumab (either every 8 weeks or every 12 weeks) or placebo. The primary outcome in the maintenance trial was clinical remission at week 44 (CDAI score < 150). Secondary outcomes included clinical response (decrease in CDAI score of > 100 points from week 0 of induction or clinical remission) at week 44, maintenance of clinical remission among participants in remission at week 0 of the maintenance trial, glucocorticosteroid‐free remission, and remission in participants who met the primary or secondary non‐response criteria or who had unacceptable adverse effects. In IM‐UNITI study, of the 397 randomized patients, 9 patients, who were randomized prior to the study restart, were excluded from the efficacy analysis population. Thus, 388 patients were included in the efficacy analysis population for IM‐UNITI.

This study assessed the effectiveness of briakinumab in adults who had Crohn's disease for at least four months that was confirmed by endoscopy or radiologic evaluation and a CDAI score ranging from 220 to 450. Exclusion criteria included people with colitis other than Crohn's disease, prior exposure to systemic or biologic anti‐IL‐12 therapy, receipt of an investigational TNF‐α antagonist at any time, or receipt of any investigational agent within 30 days of study entry. The study was conducted at 60 sites in Australia, Canada, Europe, and the United States. The study was both an induction and maintenance study that lasted 115 weeks and included 6 phases, starting with screening (< 4 weeks), induction (12 weeks), and maintenance (12 weeks). Participants were randomly assigned 1:1:1:3 to intravenous infusion induction regimens: placebo, 200 mg briakinumab, 400 mg briakinumab, and 700 mg briakinumab administered at 0, 4, and 8 weeks. At week 12, participants in the placebo group and the 400 mg induction group who achieved a clinical response continued into the maintenance phase, receiving the same treatment and dosage. Participants in the 700 mg induction group who achieved a clinical response were re‐randomized 1:1:1 to placebo, 200 mg briakinumab, or 700 mg briakinumab. Participants received placebo or briakinumab at weeks 12, 16, and 20 of the maintenance phase. A total of 104 participants were involved in the maintenance phase.

This study assessed the role of ustekinumab in adults (> 18 years) with a minimum three‐month history of moderate to severe Crohn's disease as defined by a CDAI score of 220 to 450 points. Participants enrolled in CERTIFI were recruited from 153 centers in 12 different countries. All participants were required to meet a specified criteria for a primary non‐response, secondary non‐response, or unacceptable adverse effects after receiving an anti‐TNF‐α at an approved dose. Participants were allowed to receive concomitant medications for the treatment of Crohn's disease, which included oral prednisolone or budesonide, immunomodulators, mesalamine, and antibiotics. Exclusion criteria included undergoing bowel resection within six months of enrollment, short‐bowel syndrome, clinically significant stricture, abscess, active tuberculosis, current infection, or other previous or current infections or cancers. During the induction phase of the study, 526 participants were randomly assigned to receive intravenous ustekinumab in doses of 1, 3, or 6 mg/kg or placebo. The primary outcome during the induction phase was clinical response (≥ 100‐point decrease from the baseline CDAI score) at week 6. Participants with a baseline CDAI score of 248 points or less were considered to have a clinical response if their CDAI score was less than 150. The main secondary outcomes included clinical remission (CDAI < 150) at week 6 and clinical response at week 6. During the maintenance phase of the study (weeks 8 to 36), participants who had a response to ustekinumab during the induction phase (N = 145) and those who did not respond to ustekinumab underwent separate randomizations to receive subcutaneous ustekinumab (90 mg) or placebo at weeks 8 and 16. Clinical remission and clinical response in the maintenance phase were measured at 22 weeks.

Excluded studies

We excluded three studies (Fasanmade 2008; Mannon 2004; Sands 2010). Fasanmade 2008 was a pharmacokinetics study that compared different doses of ustekinumab (4.5 mg/kg to 90 mg) and was not a randomized trial. Mannon 2004 was not a maintenance‐of‐remission study. Sands 2010 assessed a different compound of interest (i.e. a different mechanism of action than briakinumab and ustekinumab).

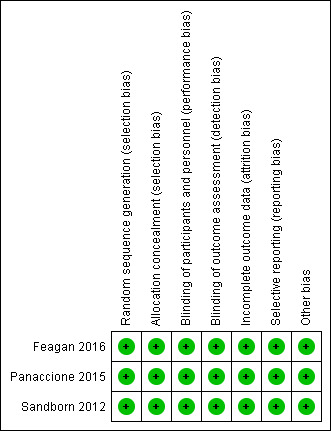

Risk of bias in included studies

A summary of the 'Risk of bias' assessment is provided in Figure 2.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

The three included studies performed central randomization and were rated as at low risk bias. Randomization in Feagan 2016 and Panaccione 2015 was performed centrally using permuted blocks in all trials. Adaptive randomization based on the investigative site and induction dose was performed centrally in Sandborn 2012.

Blinding

We assessed all included studies as at low risk of bias for blinding (Feagan 2016; Panaccione 2015; Sandborn 2012).

Incomplete outcome data

We assessed all included studies as at low risk of bias for incomplete outcome data (Feagan 2016; Panaccione 2015; Sandborn 2012). Dropouts were balanced across treatment groups with similar reasons for withdrawal.

Selective reporting

We assessed all included studies as at low risk of bias for selective reporting, as all expected outcomes were reported (Feagan 2016; Panaccione 2015; Sandborn 2012).

Other potential sources of bias

The included studies appeared to be free from other potential sources of bias and were therefore rated as at low risk of bias for this domain (Feagan 2016; Panaccione 2015; Sandborn 2012).

Effects of interventions

Ustekinumab versus placebo

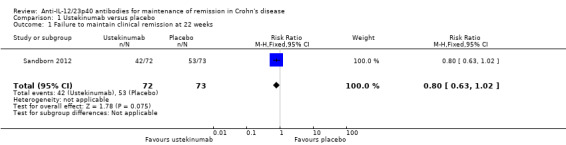

Failure to maintain clinical remission at 22 weeks

One placebo‐controlled trial involving 145 participants reported on the proportion of participants who failed to maintain clinical remission (CDAI < 150) at 22 weeks (Sandborn 2012). Fifty‐eight per cent (42/72) of ustekinumab participants failed to maintain clinical remission at week 22 compared to 73% (53/73) of placebo participants (risk ratio (RR) 0.80, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.63 to 1.02; Analysis 1.1). The GRADE analysis indicated that the overall certainty of the evidence was moderate due to sparse data (95 events; see Table 1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Ustekinumab versus placebo, Outcome 1 Failure to maintain clinical remission at 22 weeks.

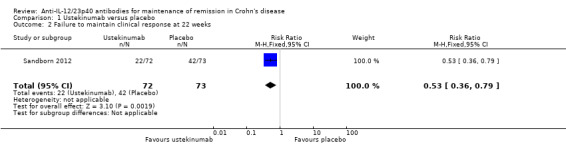

Failure to maintain clinical response at 22 weeks

One study (N = 145) reported on the proportion of participants who failed to maintain clinical response (≥ 100‐point decrease from the baseline CDAI score) at week 22 (Sandborn 2012). Thirty‐one per cent (22/72) of ustekinumab participants failed to maintain clinical response at week 22 compared to 58% (42/73) of placebo participants (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.79; Analysis 1.2). The GRADE analysis indicated the overall certainty of the evidence for this outcome was moderate due to sparse data (64 events; see Table 1).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Ustekinumab versus placebo, Outcome 2 Failure to maintain clinical response at 22 weeks.

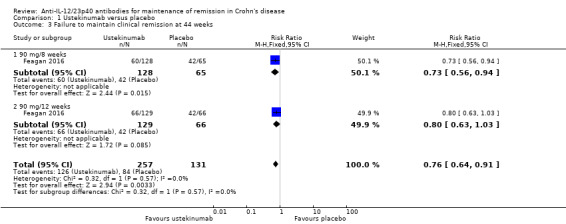

Failure to maintain clinical remission at 44 weeks

Feagan 2016 (N = 388) reported on failure to maintain clinical remission (CDAI < 150) at 44 weeks. Forty‐nine (126/257) per cent of participants in the ustekinumab group failed to maintain clinical remission compared to 64% (84/131) in the placebo group (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.91; Analysis 1.3). The GRADE analysis indicated that the overall certainty of evidence for this outcome was moderate due to sparse data (210 events; see Table 1).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Ustekinumab versus placebo, Outcome 3 Failure to maintain clinical remission at 44 weeks.

We performed a subgroup analysis based on dosing schedules of 90 mg every 8 weeks and 90 mg every 12 weeks, which suggested no difference in efficacy between the 8‐week and 12‐week dosing schedules. Among participants who were treated every 8 weeks, 47% (60/128) of ustekinumab participants failed to maintain remission at 44 weeks compared to 65% (42/65) of placebo participants (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.94; Analysis 1.3). Among participants who were treated every 12 weeks, 51% (66/129) of ustekinumab participants failed to maintain remission at 44 weeks compared to 64% (42/66) of placebo participants (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.03; Analysis 1.3). The test for subgroup differences showed no difference between the dosing schedule subgroups (test for subgroup differences Chi² = 0.32, df = 1, P = 0.57, I² = 0%).

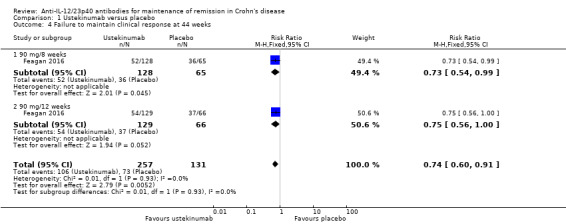

Failure to maintain clinical response at 44 weeks

Feagan 2016 (N = 388) reported on failure to maintain clinical response (≥ 100‐point decrease from the baseline CDAI score) at 44 weeks. Forty‐one per cent (106/257) of participants in the ustekinumab group failed to maintain clinical response compared to 56% (73/131) of placebo participants (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.60 to 0.91; Analysis 1.4). The GRADE analysis indicated that the overall certainty of evidence for this outcome was moderate due to sparse data (179 events; see Table 1).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Ustekinumab versus placebo, Outcome 4 Failure to maintain clinical response at 44 weeks.

We performed a subgroup analysis based on the dosing schedule of 90 mg every 8 weeks and 90 mg every 12 weeks, which suggested no difference in efficacy between the 8‐week and 12‐week dosing schedules. Among participants who were treated every 8 weeks, 41% (52/128) of ustekinumab participants failed to maintain clinical response at 44 weeks compared to 55% (36/65) of placebo participants (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.99; Analysis 1.4). Among participants who were treated every 12 weeks, 42% (54/129) of ustekinumab participants failed to maintain clinical response at 44 weeks compared to 56% (37/66) of placebo participants (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.00; Analysis 1.4). The test for subgroup differences showed no difference between the dosing schedule subgroups (test for subgroup differences Chi² = 0.01, df = 1, P = 0.93, I² = 0%).

Failure to maintain endoscopic response

Sandborn 2012 and Feagan 2016 did not report data on this outcome.

Failure to maintain endoscopic remission

Sandborn 2012 and Feagan 2016 did not report data on this outcome.

Failure to maintain histological response

Sandborn 2012 and Feagan 2016 did not report data on this outcome.

Failure to maintain histological remission

Sandborn 2012 and Feagan 2016 did not report data on this outcome.

Failure to maintain clinical and endoscopic response

Sandborn 2012 and Feagan 2016 did not report data on this outcome.

Failure to maintain clinical and endoscopic remission

Sandborn 2012 and Feagan 2016 did not report data on this outcome.

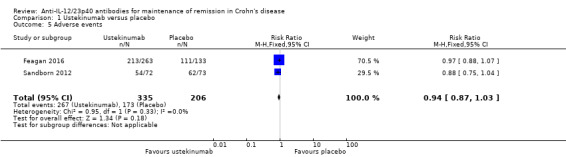

Adverse events

Two studies provided data on adverse events (Feagan 2016; Sandborn 2012). Eighty per cent (267/335) of ustekinumab participants experienced an adverse event compared to 84% (173/206) of placebo participants (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.03; I² = 0%; Analysis 1.5). The GRADE analysis indicated the overall certainty of evidence for this outcome was high (see Table 1). Commonly reported adverse events included infections, injection site reactions, Crohn's disease event, abdominal pain, nausea, arthralgia, and headache.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Ustekinumab versus placebo, Outcome 5 Adverse events.

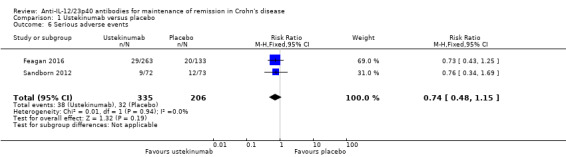

Serious adverse events

Two studies provided data on serious adverse events (Feagan 2016; Sandborn 2012). Eleven per cent (38/335) of ustekinumab participants experienced a serious adverse event compared to 16% (32/206) of placebo participants (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.48 to 1.15; I² = 0%; Analysis 1.6). The GRADE analysis indicated the overall certainty of evidence for this outcome was moderate due to sparse data (70 events; see Table 1). Serious adverse events included serious infections, malignant neoplasm, and basal cell carcinoma.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Ustekinumab versus placebo, Outcome 6 Serious adverse events.

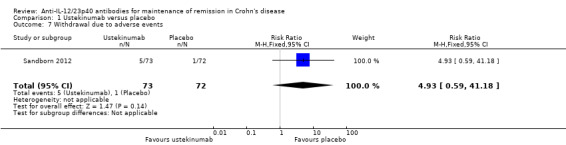

Withdrawals due to adverse events

One study provided data for withdrawal due to adverse events (Sandborn 2012). Seven per cent (5/73) of ustekinumab participants withdrew from the study due to an adverse event compared to 1% (1/72) of placebo participants (RR 4.93, 95% CI 0.59 to 41.18; Analysis 1.7). The GRADE analysis indicated the certainty of evidence was low due to very sparse data (6 events; see Table 1). Adverse events leading to study withdrawal included worsening Crohn's disease.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Ustekinumab versus placebo, Outcome 7 Withdrawal due to adverse events.

Subgroup analysis

We did not perform a subgroup analysis by dose because participants in both studies received 90 mg subcutaneous ustekinumab as maintenance therapy.

Sensitivity analyses

We did not perform sensitivity analyses as both studies had very similar populations and inclusion criteria (Feagan 2016; Sandborn 2012). Both studies used the same dose and method of administration for treatments, and outcomes were measured using the same criteria. This made fixed‐effect the most appropriate method of analysis. We did not conduct sensitivity analysis for risk of bias as we assessed both studies as at low risk of bias. Both studies were Phase II randomized controlled trials and were reported as full manuscripts, therefore we did not conduct sensitivity analysis for type of report.

Briakinumab versus placebo

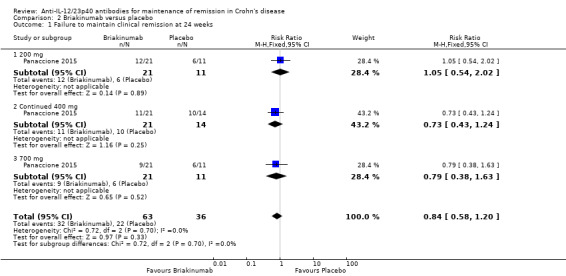

Failure to maintain clinical remission at 24 weeks

Panaccione 2015 (99 participants) reported on failure to maintain clinical remission (CDAI < 150) at 24 weeks. Fifty‐one per cent (32/63) of participants in the briakinumab group failed to maintain clinical remission at 24 weeks compared to 61% (22/36) of placebo participants (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.20; Analysis 2.1). The GRADE analysis indicated the certainty of evidence was low due to sparse data (54 events) and a very wide confidence interval (see Table 2).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Briakinumab versus placebo, Outcome 1 Failure to maintain clinical remission at 24 weeks.

A subgroup analysis based on dose suggested that there was no difference in remission rates across the 200 mg, 400 mg, or 700 mg dose subgroups. Among participants in the 200 mg group, 57% (12/21) of briakinumab participants failed to maintain remission at 24 weeks compared to 54% (6/11) of placebo participants (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.54 to 2.02; Analysis 2.1). Among participants in the 400 mg group, 52% (11/21) of briakinumab participants failed to maintain remission at 24 weeks compared to 71% (10/14) of placebo participants (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.43 to 1.24; Analysis 2.1). Lastly, among participants in the 700 mg group, 43% (9/21) of briakinumab participants failed to maintain remission at 24 weeks compared to 54% (6/11) of placebo participants (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.63; Analysis 2.1). The test for subgroup differences showed no difference between the dose subgroups (test for subgroup differences Chi² = 0.72, df = 2, P = 0.70, I² = 0%).

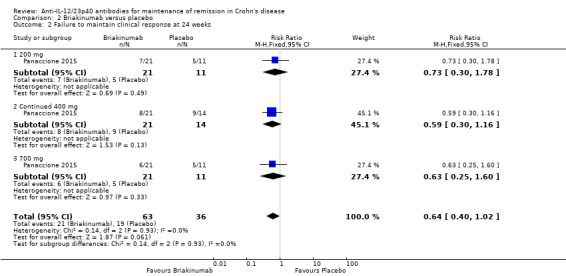

Failure to maintain clinical response at 24 weeks

Panaccione 2015 (99 participants) reported on failure to maintain clinical response (≥ 100‐point decrease in CDAI from baseline) at 24 weeks. Thirty‐three per cent (21/63) of briakinumab participants failed to maintain clinical response at 24 weeks compared to 53% (19/36) of placebo participants (RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.40 to 1.02; Analysis 2.2). The GRADE analysis indicated the certainty of evidence was low due to very sparse data (30 events; see Table 2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Briakinumab versus placebo, Outcome 2 Failure to maintain clinical response at 24 weeks.

A subgroup analysis based on dose suggested that there was no difference in response rates across the 200 mg, 400 mg, or 700 mg dose subgroups. Among participants in the 200 mg group, 33% (7/21) of briakinumab participants failed to maintain clinical response at 24 weeks compared with 45% (5/11) of placebo participants (RR 0.73, 95% CI 0.30 to 1.78; Analysis 2.2). Among participants in the 400 mg group, 38% (8/21) of briakinumab participants failed to maintain clinical response at 24 weeks compared with 64% (9/14) of placebo participants (RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.30 to 1.16; Analysis 2.2). Lastly, among participants in the 700 mg group, 29% (6/21) of briakinumab participants failed to maintain clinical response at 24 weeks compared to 45% (5/11) of placebo participants (RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.60; Analysis 2.2). The test for subgroup differences showed no difference between the dose subgroups (test for subgroup differences Chi² = 0.14, df = 2, P = 0.93, I² = 0%).

Failure to maintain endoscopic response

Panaccione 2015 did not report data on this outcome.

Failure to maintain endoscopic remission

Panaccione 2015 did not report data on this outcome.

Failure to maintain histological response

Panaccione 2015 did not report data on this outcome.

Failure to maintain histological remission

Panaccione 2015 did not report data on this outcome.

Failure to maintain clinical and endoscopic response

Panaccione 2015 did not report data on this outcome.

Failure to maintain clinical and endoscopic remission

Panaccione 2015 did not report data on this outcome.

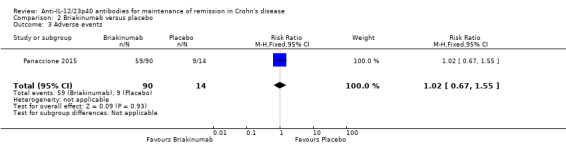

Adverse events

Adverse events were reported in 66% (59/90) of briakinumab participants compared to 64% (9/14) of placebo participants (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.55; Analysis 2.3) (Panaccione 2015). Commonly reported adverse events included upper respiratory tract infection, nausea, abdominal pain, headache, and injection site reaction. The GRADE analysis indicated the certainty of evidence was low due to sparse data (68 events) and a very wide confidence interval (see Table 2).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Briakinumab versus placebo, Outcome 3 Adverse events.

Serious adverse events

Serious adverse events were reported in 2% (2/90) of briakinumab participants compared to 7% (1/14) of placebo participants (RR 0.31, 95% CI 0.03 to 3.21; Analysis 2.4) (Panaccione 2015). Serious adverse events included small bowel obstruction, deep vein thrombosis, and respiratory distress. The GRADE analysis indicated the certainty of evidence was low due to very sparse data (3 events; see Table 2).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Briakinumab versus placebo, Outcome 4 Serious adverse events.

Withdrawal due to adverse events

Withdrawals due to adverse events were reported in 2% of briakinumab participants compared to 0% (0/14) of placebo participants (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.04 to 16.34; Analysis 2.5) (Panaccione 2015). The adverse events leading to withdrawal were not reported in the manuscript. The GRADE analysis indicated the certainty of evidence was low due to very sparse data (2 events; see Table 2).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Briakinumab versus placebo, Outcome 5 Withdrawal due to adverse events.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This systematic review included three randomized controlled trials (646 participants) that evaluated the efficacy and safety of ustekinumab or briakinumab as maintenance therapy in people with moderate to severe Crohn's disease. Feagan 2016 (N = 397) assessed maintenance therapy in participants receiving 90 mg of ustekinumab (every 8 or 12 weeks) or placebo. Sandborn 2012 (N = 145) assessed maintenance therapy in participants receiving 90 mg of ustekinumab or placebo at weeks 8 and 16. Panaccione 2015 assessed maintenance therapy (N = 104) in participants receiving 200 mg, 400 mg, or 700 mg of briakinumab or placebo at weeks 12, 16, and 20 of the maintenance phase of the study. The participants in all three studies were responders to ustekinumab or briakinumab induction therapy. Caution is advised in interpreting the results of this review, as the certainty of the evidence was impacted by sparse data.

Moderate‐certainty evidence suggests that ustekinumab is probably effective for the maintenance of clinical remission and response at 22 weeks and 44 weeks in people with moderate to severe Crohn's disease in remission. Subgroup analyses showed no difference in efficacy between 8‐week and 12‐week dosing schedules. High‐certainty evidence suggests there is no increased risk of adverse events with ustekinumab when compared with placebo. Moderate‐certainty evidence suggests there is no increased risk of serious adverse events with ustekinumab compared with placebo. Commonly reported adverse events included infections, injection site reactions, Crohn's disease event, abdominal pain, nausea, arthralgia, and headache. Serious adverse events included serious infections, malignant neoplasm, and basal cell carcinoma.

The effect of briakinumab on maintenance of clinical remission and response in people with moderate to severe Crohn's disease in remission was uncertain as the certainty of the evidence was low. Subgroup analysis showed no difference in efficacy across the 200 mg, 400 mg, and 700 mg dose subgroups. However, the number of participants assessed in each subgroup was small, therefore the ideal dose of briakinumab, should one exist, is unknown. The effect of briakinumab on adverse events and serious adverse events was uncertain as the certainty of the evidence was low. Commonly reported adverse events included upper respiratory tract infection, nausea, abdominal pain, headache, and injection site reaction. Serious adverse events included small bowel obstruction, deep vein thrombosis, and respiratory distress.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The results of this review are applicable to individuals with moderate to severe Crohn's disease in remission. The study participants included people who had failed standard therapy with corticosteroids or immunosuppressants or who had developed unacceptable adverse effects associated with these agents, or people who had previous treatment with TNF‐α antagonists and had lost response or had become intolerant to the drug. However, the overall evidence cannot be considered complete. The three included studies (646 participants) assessed maintenance therapy of moderate to severe Crohn's disease with ustekinumab or briakinumab and reported data on maintenance of clinical remission and clinical response, adverse events, serious adverse events, and withdrawals due to adverse events. We did not pre‐specify quality of life as a secondary outcome. Furthermore, some of our prespecified secondary outcomes, including maintenance of endoscopic response and remission and maintenance of histological response and remission, were not reported in the included studies.

Quality of the evidence

We judged all three included studies as at low risk of bias. For ustekinumab, GRADE analysis indicated the overall certainty of the evidence supporting the primary outcome of failure to maintain clinical remission was moderate. The certainty of the evidence supporting the secondary outcomes of failure to maintain clinical response and serious adverse events was moderate. The certainty of the evidence supporting the outcomes adverse events and withdrawal due to adverse events was high and low, respectively. Outcomes that were downgraded were due to varying degrees of imprecision (sparse data).

For briakinumab, GRADE analysis indicated the overall certainty of the evidence supporting the primary outcome of failure to maintain clinical remission was low. The certainty of the evidence supporting the secondary outcomes failure to maintain clinical response, adverse events, serious adverse events, and withdrawal due to adverse events was low. We downgraded all of the outcomes due to varying degrees of imprecision (sparse data).

Potential biases in the review process

In order to reduce potential bias in the review process we performed a comprehensive literature search to identify all eligible studies. Two review authors independently assessed studies for inclusion, extracted data, and assessed risk of bias. There were some limitations to this review. Due to differing time points for analysis in the two ustekinumab studies, the primary outcome and several secondary outcomes could not be pooled for meta‐analysis. In addition, many of the outcomes assessed in this systematic review were given GRADE ratings of moderate or low certainty due to sparse event data. None of the included studies used endoscopic remission or response as an outcome, despite the increasing use of endoscopic outcomes in Crohn's disease studies. Further research is needed to assess the impact of ustekinumab and briakinumab on these outcomes.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The results of our systematic review with respect to the efficacy and safety of ustekinumab agree with the results of a recently published systematic review, Zaltman 2019, and the results of a recently published network meta‐analysis (Singh 2018). We were unable to identify any systematic reviews dealing with the efficacy and safety of briakinumab for maintenance of remission in people with moderate to severe Crohn's disease in remission.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Moderate‐certainty evidence suggests that ustekinumab is probably effective for the maintenance of clinical remission and response at 22 weeks and 44 weeks in people with moderate to severe Crohn's disease in remission. High‐certainty evidence suggests that there is no increased risk of adverse events with ustekinumab compared with placebo. Moderate‐certainty evidence suggests that there is no increased risk of serious adverse events with ustekinumab compared with placebo. The effect of briakinumab on maintenance of clinical remission and response in people with moderate to severe Crohn's disease in remission was uncertain due to low‐certainty evidence. The effect of briakinumab on adverse events and serious adverse events was uncertain due to low‐certainty evidence.

Implications for research.

Further studies are required to increase the quality of evidence available for the use of subcutaneous ustekinumab in the maintenance of moderate to severe Crohn's disease in remission. In addition, further studies are required to determine the long‐term efficacy and safety of subcutaneous ustekinumab maintenance therapy in Crohn's disease, and whether it should be used as monotherapy or combined with other agents. Future research should also consider comparing ustekinumab directly to other biologic treatments in order to define its position in the treatment algorithm for Crohn's disease. Real World Effectiveness of Ustekinumab in Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Crohn's Disease (RUN‐CD) is a prospective cohort study currently in the recruitment phase that will compare ustekinumab to other biologics for the induction and maintenance of remission in Crohn’s disease. There is also an ongoing randomized controlled trial comparing maintenance therapy with ustekinumab to adalimumab in participants with moderate to severe Crohn's disease in remission (NCT03464136). The manufacturers of briakinumab have stopped production of this medication, thus further studies of briakinumab are unlikely.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Appendix 1

Embase

1 random$.tw.

2 factorial$.tw.

3 (crossover$ or cross over$ or cross‐over$).tw.

4 placebo$.tw.

5 single blind.mp.

6 double blind.mp.

7 triple blind.mp.

8 (singl$ adj blind$).tw.

9 (double$ adj blind$).tw.

10 (tripl$ adj blind$).tw.

11 assign$.tw.

12 allocat$.tw.

13 crossover procedure/

14 double blind procedure/

15 single blind procedure/

16 triple blind procedure/

17 randomized controlled trial/

18 or/1‐17

19 (exp animal/ or animal.hw. or nonhuman/) not (exp human/ or human cell/ or (human or humans).ti.)

20 18 not 19

21 exp Crohn disease/ or crohn*.mp. or exp colon Crohn disease/

22 (inflammatory bowel disease* or IBD).mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer, device trade name, keyword]

23 21 or 22

24 ustekinumab.mp. or exp ustekinumab/

25 briakinumab.mp. or exp briakinumab/

26 (abt‐874 or "cnto 1275").mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer, device trade name, keyword]

27 24 or 25 or 26

28 "interleukin 12".mp. or exp interleukin 12/

29 "interleukin 23".mp. or exp interleukin 23/

30 (IL‐12 or IL‐23 or p40).mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer, device trade name, keyword]

31 28 or 29 or 30

32 exp monoclonal antibody/ or exp antibody/ or antibod*.mp.

33 31 and 32

34 anti‐IL‐12 23p40.mp.

35 27 or 33 or 34

36 20 and 23 and 35

MEDLINE

1 random$.tw.

2 factorial$.tw.

3 (crossover$ or cross over$ or cross‐over$).tw.

4 placebo$.tw.

5 single blind.mp.

6 double blind.mp.

7 triple blind.mp.

8 (singl$ adj blind$).tw.

9 (double$ adj blind$).tw.

10 (tripl$ adj blind$).tw.

11 assign$.tw.

12 allocat$.tw.

13 randomized controlled trial/

14 or/1‐13

15 (exp animal/ or animal.hw. or nonhuman/) not (exp human/ or human cell/ or (human or humans).ti.)

16 14 not 15

17 exp Crohn disease/ or crohn*.mp.

18 ("inflammatory bowel disease*" or IBD).mp. [mp=title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept, rare disease supplementary concept, unique identifier]

19 17 or 18

20 (ustekinumab or briakinumab or "CNTO 1275" or ABT‐874).mp. [mp=title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept, rare disease supplementary concept, unique identifier]

21 interleukin 12.mp. or exp Interleukin‐12/

22 interleukin 23.mp. or exp Interleukin‐23/

23 (IL‐12 or IL‐23 or p40).mp. [mp=title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept, rare disease supplementary concept, unique identifier]

24 21 or 22 or 23

25 antibod*.mp. or exp Antibodies/ or exp Antibodies, Monoclonal/

26 24 and 25

27 IL‐12 23p40.mp.

28 20 or 26 or 27

29 16 and 19 and 28

Cochrane Library (CENTRAL)

1 ustekinumab or briakinumab or ABT‐874 or CNTO 1275

2 interleukin 12 or interleukin 23 or IL‐12 or il‐23 or p40

3 antibod*

4 #2 and #3

5 anti‐il‐12/23p40

6 #1 or #4 or #5

7 #6 and (Crohn* or IBD or "inflammatory bowel disease*")

ClinicalTrials.gov, clinicaltrials.ifpma.org, and isrctn.com

(interleukin 12, interleukin‐12, IL‐12, interleukin 23, interleukin‐23, IL‐23, p40, ustekinumab, CNTO 1275, briakinumab and ABT‐874) were all searched with the search term: crohn*

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Ustekinumab versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Failure to maintain clinical remission at 22 weeks | 1 | 145 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.63, 1.02] |

| 2 Failure to maintain clinical response at 22 weeks | 1 | 145 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.53 [0.36, 0.79] |

| 3 Failure to maintain clinical remission at 44 weeks | 1 | 388 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.76 [0.64, 0.91] |

| 3.1 90 mg/8 weeks | 1 | 193 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.56, 0.94] |

| 3.2 90 mg/12 weeks | 1 | 195 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.63, 1.03] |

| 4 Failure to maintain clinical response at 44 weeks | 1 | 388 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.74 [0.60, 0.91] |

| 4.1 90 mg/8 weeks | 1 | 193 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.54, 0.99] |

| 4.2 90 mg/12 weeks | 1 | 195 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.56, 1.00] |

| 5 Adverse events | 2 | 541 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.87, 1.03] |

| 6 Serious adverse events | 2 | 541 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.74 [0.48, 1.15] |

| 7 Withdrawal due to adverse events | 1 | 145 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.93 [0.59, 41.18] |

Comparison 2. Briakinumab versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Failure to maintain clinical remission at 24 weeks | 1 | 99 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.58, 1.20] |

| 1.1 200 mg | 1 | 32 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.54, 2.02] |

| 1.2 Continued 400 mg | 1 | 35 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.43, 1.24] |

| 1.3 700 mg | 1 | 32 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.79 [0.38, 1.63] |

| 2 Failure to maintain clinical response at 24 weeks | 1 | 99 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.40, 1.02] |

| 2.1 200 mg | 1 | 32 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.30, 1.78] |

| 2.2 Continued 400 mg | 1 | 35 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.59 [0.30, 1.16] |

| 2.3 700 mg | 1 | 32 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.25, 1.60] |

| 3 Adverse events | 1 | 104 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.67, 1.55] |

| 4 Serious adverse events | 1 | 104 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.31 [0.03, 3.21] |

| 5 Withdrawal due to adverse events | 1 | 104 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.04, 16.34] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Feagan 2016.

| Methods | Randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial | |

| Participants |

Inclusion criteria: adult patients (≥ 18 years) with at least a 3‐month history of Crohn's disease and a score of 220 to 450 points on the CDAI were included in the induction phase. For the UNITI‐1 study, participants had moderate to severe Crohn's disease that was resistant to TNF‐α antagonists. For the UNITI‐2 study, participants were required to have treatment failure or unacceptable side effects when treated with immunosuppressants or glucocorticoids. 397 participants who had a clinical response to ustekinumab induction therapy (UNITI‐1 or UNITI‐2) were randomized to the maintenance study (IM‐UNITI). 9 patients, who were randomized prior to the study restart, resulting in 388 patients in the efficacy analysis population for IM‐UNITI. Exclusion criteria: previous therapy specifically targeting interleukin‐12 or interleukin‐23 |

|

| Interventions | Group 1: Placebo (n = 133) Group 2: Subcutaneous ustekinumab 90 mg, every 8 weeks (n = 132) Group 3: Subcutaneous ustekinumab 90 mg, every 12 weeks (n = 132) |

|

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome:

Secondary outcomes:

|

|

| Duration of follow‐up |

Induction phase: 8 weeks Maintenance phase: 44 weeks |

|

| Notes | This manuscript reports the results of 3 randomized trials: UNITI‐1 (induction), UNITI‐2 (induction), and IM‐UNITI (maintenance). The results of the induction studies are not reported in this review. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated randomization |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomization was performed centrally with the use of permuted blocks in all trials. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | The study agents were identical in appearance and packaging. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Treatment assignment blinding was maintained for investigative sites, site monitors, and participants in the study until the week 44 analyses were completed. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Dropouts were balanced across interventions with similar reasons for withdrawal. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All expected outcomes were reported. |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free of other sources of bias. |

Panaccione 2015.

| Methods | Phase 2b, multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial | |

| Participants |

Inclusion criteria: adult patients (N = 104 for maintenance phase) with a diagnosis of Crohn's disease for 4 months, confirmed by endoscopy or radiologic evaluation, and a CDAI score > 220 and < 450 Participants who had a response to briakinumab during the induction phase were able to enter the maintenance phase. Exclusion criteria: patients with colitis other than Crohn's disease, prior exposure to systemic or biologic anti‐IL‐12 therapy, receipt of an investigational TNF antagonist at any time, or receipt of any investigational agent within 30 days or 5 half‐lives before week 0 visit were not eligible. |

|

| Interventions | Group 1: Placebo (n = 36) Group 2: Briakinumab 200 mg (n = 26) Group 2: Briakinumab 400 mg (n = 21) Group 3: Briakinumab 700 mg (n = 21) Participants received study drugs at weeks 12, 16, and 20 of the maintenance phase. |

|

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome:

Secondary outcomes:

|

|

| Duration of follow‐up |

Induction phase: week 12 Maintenance phase: week 24 |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomization schemes were generated by the study sponsor before the start of the study. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Randomization and re‐randomization was performed centrally. |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Participants were randomly assigned to intravenous infusion. The participants were unaware of their treatment assignments. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | The study sponsor, site personnel, and participants were unaware of the treatment assignments throughout both the induction and maintenance phases. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Dropouts were balanced across interventions with similar reasons for withdrawal. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All expected outcomes were reported. |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free of other sources of bias. |

Sandborn 2012.

| Methods | Randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial | |

| Participants |

Inclusion criteria: adult patients (≥ 18 years) with at least a 3‐month history of Crohn's disease and a score of 220 to 450 points on the CDAI were included in the induction phase. CERTIFI participants had moderate to severe Crohn's disease that was resistant to TNF‐α antagonists. Participants with a response to ustekinumab at 6 weeks of the induction phase were included in the maintenance phase (N = 145). Exclusion criteria: previous therapy specifically targeting interleukin‐12 or interleukin‐23 |

|

| Interventions | Group 1: Placebo (N = 73) Group 2: Subcutaneous ustekinumab at weeks 8 and 16 (weeks 1 and 9 of maintenance phase), 90 mg (N = 72) |

|

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome:

Secondary outcomes:

|

|

| Duration of follow‐up |

Induction phase: 8 weeks Maintenance phase: 36 weeks |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Central randomization was performed based on investigative site and the induction dose using Pocock and Simon's (1975) randomization method. |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Centralized randomization |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Placebo administrations will have the same appearance as the respective ustekinumab administrations. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Treatment assignment blinding was maintained for investigative sites, site monitors, and participants in the study until the week 36 analyses were completed. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Dropouts were balanced across interventions with similar reasons for withdrawal. |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All expected outcomes were reported. |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free of other sources of bias. |

CDAI: Crohn's Disease Activity Index; TNF‐α: tumor necrosis factor‐alpha

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Fasanmade 2008 | Not a randomized controlled trial |

| Mannon 2004 | Not a maintenance trial |

| Sands 2010 | Does not investigate our compound of interest This study investigated apilimode mesylate, which acts at the level of transcription rather than directly on the p40 subunit. |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

NCT03464136.

| Trial name or title | Safety and Efficacy of Adalimumab Versus Ustekinumab for One Year (SEAVUE) |

| Methods | Randomized, blinded, active‐controlled study |

| Participants |

Inclusion criteria: moderate to severe Crohn's disease or fistulizing Crohn's disease of at least 3 months' duration, has not previously received an approved biologic for Crohn's disease Exclusion criteria: has complications of Crohn's disease that are likely to require surgery |

| Interventions | Group 1: Ustekinumab. Participants will receive IV infusion of ustekinumab (6 mg/kg) and 4 SC injections of placebo for adalimumab at week 0, followed by 2 SC injections of placebo at week 2. From week 4 to week 56, participants will self‐administer 1 SC injection of ustekinumab 90 mg every 8 weeks starting at week 8 and placebo adalimumab at 2 week dosing intervals. Group 2: Adalimumab. Participants will receive IV infusion of placebo for ustekinumab and 4 SC injections of adalimumab (each 40 mg, total dose 160 mg) at week 0, followed by 2 SC injections of adalimumab (each 40 mg, total dose 80 mg) at week 2. From week 4 to week 56, participants will self‐administer 1 SC injection of adalimumab 40 mg every 2 weeks. |

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome:

Secondary outcomes:

|

| Starting date | 29 March 2018 |

| Contact information | Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC Telephone: 844‐434‐4210; email: JNJ.CT@sylogent.com |

| Notes |

IV: intravenous; SC:subcutaneous

Differences between protocol and review

For the published protocol we did not pre‐specify which outcomes would be included in the 'Summary of findings' tables. This decision was made after the publication of the protocol.

Contributions of authors

Sarah C Davies: screening of abstracts and titles, screening of full‐text articles, data extraction, 'Risk of bias' assessment; data entry, data analysis, reporting of results, and manuscript preparation.

Tran M Nguyen: ran first literature search; screening of abstracts and titles, screening of full‐text articles, data extraction, 'Risk of bias' assessment; data analysis, GRADE assessment, reporting of results, and manuscript preparation.

Claire E Parker: provided methodological expertise, critical revision of the manuscript, and approval of the final manuscript.

John K MacDonald: provided methodological expertise, ran second literature search; checked data extraction and analysis; checked GRADE analysis, checked reporting of results; manuscript preparation; critical revision of the manuscript and approval of the final manuscript.

Vipul Jairath: provided clinical and methodological expertise, critical revision of the manuscript, and approval of the final manuscript.

Reena Khanna: provided clinical and methodological expertise, adjudication of study selection, data extraction, or 'Risk of bias' assessment; critical revision of the manuscript and approval of the final manuscript.

Declarations of interest

John K MacDonald, Tran M Nguyen, Claire E Parker, and Sarah C Davies have no known conflicts of interest.

Vipul Jairath has received scientific advisory board fees from AbbVie, Sandoz, Ferring, and Janssen; speaker's fees from Takeda and Ferring; and travel support for conference attendance from Vifor Pharma. All of these activities are outside the submitted work.