Abstract

Objectives/Hypothesis

Literature examining long-term survival in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) with human papillomavirus (HPV) status is lacking. We compare 10-year overall survival (OS) rates for cases to population-based controls.

Study Design

Prospective cohort study.

Methods

Cases surviving 5 years postdiagnosis were identified from the Carolina Head and Neck Cancer Study. We examined 10-year survival by site, stage, p16, and treatment using Kaplan-Meier and Cox proportional hazard models. Cases were compared to age-matched, noncancer controls with stratification by p16 and smoking status.

Results

Ten-year OS for HNSCC is less than controls. In 581 cases, OS differed between sites with p16+ oropharynx having the most favorable prognosis (87%), followed by oral cavity (69%), larynx (67%), p16− oropharynx (56%), and hypopharynx (51%). Initial stage, but not treatment, also impacted OS. When compared to controls matched on smoking status, the hazard ratio (HR) for death in p16+ oropharynx cases was 1.5 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.7–3.1) for smokers and 2.4 (95% CI: 0.7–8.8) for nonsmokers. Similarly, HR for death in non–HPV-associated HNSCC was 2.2 (95% CI: 1.7–3.0) for smokers and 2.4 (95% CI: 1.4–4.9) for nonsmokers.

Conclusions

OS for HNSCC cases continues to decrease 5 years posttreatment, even after stratification by p16 and smoking status. Site, stage, smoking, and p16 status are significant factors. These data provide important prognostic information for HNSCC.

Level of Evidence

2

Keywords: Head and neck neoplasms, oropharynx, survival, smoking, human papillomavirus

INTRODUCTION

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is a heterogeneous disease that includes cancers involving the oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx. Worldwide, there are more than 550,000 new cases and 380,000 deaths each year from HNSCC.1 Between 2006 and 2012, the American Cancer Society estimated a 5-year survival of 64% for oral cavity (OC) and pharynx cancers and 61% for larynx cancer.2 The majority of HNSCC recurrences or disease-specific deaths occur within the first 2 to 3 years,3,4 and patients are often considered cured after 5 years.

Traditionally, tobacco and alcohol use are the most important risk factors for HNSCC. Heavy smokers have a 5- to 25-fold increased risk of developing HNSCC when compared to nonsmokers.5,6 Alcohol has both an independent and multiplicative effect on the risk for HNSCC, with a more than 35-fold increase in those who smoke more than two packs of cigarettes and consume more than four alcoholic beverages daily.5 Other risk factors, such as chewing betel nut, diet, and poor oral health, have also been reported.7–9 Cessation of and abstinence from smoking for more than 10 years reduces the risk of cancer development.5 After treatment, smoking remains a critical determinant of outcomes, as smokers are at higher risk for treatment failure, disease recurrence, and development of second primaries.10–12

Over the last 20 years, the epidemiology of HNSCC has changed significantly due to human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC).13 These patients often present with early primary tumor stage but advanced nodal stage and thus advanced overall stage. In contrast to traditional HNSCC patients, those with HPV-associated OPSCC are often younger, nonsmokers, of higher socioeconomic status, male, and Caucasian.14–16 Even after adjustment for these factors, patients with HPV-associated OPSCC have improved overall and disease-free survival.17 The reported overall survival (OS) for HPV-associated OPSCC, regardless of stage, is approximately 80% at 5 years.15,18

Few studies have examined OS in HNSCC beyond 5 years and none with stratification by HPV status. Moreover, most studies have not been population-based, reducing the generalizability of the findings. Using a large population-based case-control study, we aimed to examine 10-year OS in a cohort of cases who have already survived 5 years posttreatment. With subsequent stratification by HPV status, we compared cancer cases with noncancer controls to assess the overall long-term mortality burden associated with HNSCC beyond the initial 5 years.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

The Carolina Head and Neck Cancer Study (CHANCE), is a population-based case-control study of HNSCC conducted between January 1, 2002 and February 28, 2006 in North Carolina.7,19 Cases were identified and recruited through rapid case ascertainment through the North Carolina Central Cancer Registry. To be eligible for this study, cases must have a diagnosed first primary HNSCC of the oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx, aged 20 to 80 years, who resided in central North Carolina. Controls were residents of the same geographic and age range without a diagnosis of HNSCC sampled through the Department of Motor Vehicles records. Controls were frequency matched to cases on age, sex, and race at the time of study enrollment. Demographic, socioeconomic, and basic health information were collected for all participants, along with pathology reports and tumor characteristics for HNSCC cases. Case records were reviewed and staged according to the 7th edition American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging guidelines.20 The institutional review board at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill approved the study.

Matching and Stratification

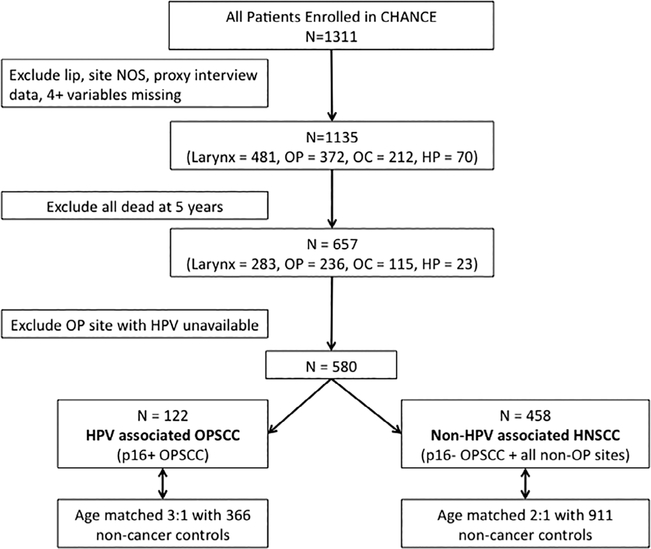

For this study, CHANCE cases with lip cancer, proxy interview data, extensive (four or more variables) missing covariate information, distant metastasis, and site not otherwise specified were excluded (Fig. 1). We limited our study group to 657 cases alive 5 years postdiagnosis. An additional 77 cases were excluded because they had OPSCC, but HPV status could not be determined due to insufficient tissue availability. Remaining cases were stratified by HPV status into two groups: 122 cases with HPV-associated OPSCC and 458 cases with non–HPV-associated HNSCC, which included HPV-negative OPSCC and nonoropharyngeal subsites. Nonoropharyngeal subsites and non–HPV-associated OPSCC were combined due to similar risk profiles and the small number of non–HPV-associated OPSCC cases in the study. Cases were then frequency matched with noncancer controls alive 5 years following reference date in the following age increments: 20 to 49, 50 to 54, 55 to 59, 60 to 64, 65 to 69, 70 to 74, and 75 to 80 years. The 122 HPV-associated OPSCC cases were age matched 3:1 with 366 noncancer controls, whereas the 458 non–HPV-associated HNSCC cases were age-matched 2:1 with 911 noncancer controls alive 5 years following reference date.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of patient selection and stratification. CHANCE = Carolina Head and Neck Cancer Study; HNSCC = head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; HP = hypopharynx; HPV = human papillomavirus; NOS = not otherwise specified; OC = oral cavity; OP = otopharyngeal; OPSCC = oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma.

HPV Status

We use p16 immunohistochemical expression as a surrogate for HPV positivity given its clinical utility and widespread availability in medical centers.21–23 The International Agency for Research on Cancer performed the p16 immunohistochemistry evaluation using the protocol provided with the CINtec Histology p16INK4a kit (9511; Mtm Laboratories Inc., Westborough, MA). Qualitative detection of p16 expression patterns on slides prepared from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor samples were graded based on percentage of stained cells (0 = 0% stained cell, 1 = 1%–10% stained cells, 2 = 11%–50% stained cells, 3 = 51%–80% stained cells, 4 = 81%–100% stained cells) and intensity of nuclear or cytoplasmic staining (0 = no staining, 1 = weak staining, 2 = moderate staining, 4 = strong staining). The two scores were multiplied, and scores greater than 4 were considered positive for p16 expression. p16 immunohistochemistry was performed on all oropharyngeal cancer cases with available tumor blocks (N = 248) and a random sample of nonoropharyngeal cancers (N = 244). p16 status was available for 463 HNSCC cases alive 5 years after diagnosis.

Outcome Assessment

Death was identified through December 31, 2013 by linking CHANCE data to the National Death Index (NDI) using name, social security number, date of birth, sex, race, and state of residence. The NDI is a national file compiled from those submitted by State Vital Statistics offices of identified death records and cause of death. Greater than 75% of cases in CHANCE were perfect or near-perfect matches to the NDI on social security number, date of birth, and sex. Near matches were confirmed by examining the United States Social Security Death Index and obituaries on newspaper websites.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe case, disease, and treatment characteristics. P values were calculated with the χ2 test for categorical variables and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables. OS was measured from baseline to cases’ death obtained from the NDI, with baseline being 5-years postdiagnosis for cases and 5-years following reference date for controls. However, for simplicity, OS was reported at 10 years postdiagnosis for each group. Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank values were calculated. Additionally, Kaplan-Meier curves were adjusted by reweighting the cases to the controls based on age, race, and smoking status (ever/never).24,25 For HPV-associated OPSCC and non–HPV-associated HNSCC cases, Kaplan-Meier curves were constructed and stratified by baseline smoking (<10 pack-years versus ≥10 pack-years) for both cases and controls. Hazard ratios were calculated with Cox proportional hazards model with baseline as 5-years postdiagnosis for cases and 5-years following reference date adjusted for private insurance (yes/no), race (white vs. nonwhite), sex, and continuous age. The confounders were determined a priori based on the relationship between smoking, stage, and site with survival. Proportional hazards assumption was tested and satisfied. Statistical analysis was performed using R version 3.1.4 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

A total of 657 CHANCE cases were alive at 5 years. These 657 cases (283 larynx, 236 oropharynx, 115 OC, and 23 hypopharynx) had an overall 5-year survival of 58% (63% oropharynx, 59% larynx, 54% OC, and 33% hypopharynx) (see Supporting Figure 1 in the online version of this article). Seventy-seven oropharynx cases without available HPV status were subsequently excluded; the remaining 580 cases comprised the primary analytic dataset. The median follow-up time was 9.2 years from date of diagnosis. Basic characteristics of cases and controls are shown in Table I.

TABLE I.

Characteristics of Cases Surviving at 5 Years After Diagnosis and Controls.

| Cases |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypopharynx, n = 23 | Larynx, n = 283 | Oral Cavity, n = 115 | Oropharynx, n = 236 | Controls, n = 1,250 | Overall, N = 1,907 | |

| Age at enrollment, yr, no. (%) | ||||||

| ≤50 | 6 (26.1) | 52 (18.4) | 22 (19.1) | 76 (32.2) | 181 (14.5) | 337 (17.7) |

| 51–65 | 11 (47.8) | 149 (52.7) | 58 (50.4) | 129 (54.7) | 538 (43.0) | 885 (46.4) |

| 66+ | 6 (26.1) | 82 (29.0) | 35 (30.4) | 31 (13.1) | 531 (42.5) | 685 (35.9) |

| Race, no. (%) | ||||||

| White | 12 (52.2) | 202 (71.4) | 89 (77.4) | 193 (81.8) | 1,000 (80.0) | 1,496 (78.4) |

| Black | 10 (43.5) | 76 (26.9) | 25 (21.7) | 34 (14.4) | 233 (18.6) | 378 (19.8) |

| Other | 1 (4.3) | 5 (1.8) | 1 (0.9) | 9 (3.8) | 17 (1.4) | 33 (1.7) |

| Sex, no. (%) | ||||||

| Male | 20 (87.0) | 224 (79.2) | 73 (63.5) | 194 (82.2) | 853 (68.2) | 1,364 (71.5) |

| Female | 3 (13.0) | 59 (20.8) | 42 (36.5) | 42 (17.8) | 397 (31.8) | 543 (28.5) |

| Smoking, no. (%) | ||||||

| < 10 pack-years | 4 (18.2) | 29 (10.2) | 22 (19.1) | 93 (39.7) | 718 (57.5) | 866 (45.5) |

| ≥10 pack-years | 18 (81.8) | 254 (89.8) | 93 (80.9) | 141 (60.3) | 530 (42.5) | 1,036 (54.5) |

| NA | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Education, no. (%) | ||||||

| <HS | 11 (47.8) | 107 (37.8) | 36 (31.3) | 39 (16.5) | 174 (13.9) | 367 (19.2) |

| HS | 5 (21.7) | 80 (28.3) | 33 (28.7) | 64 (27.1) | 298 (23.8) | 480 (25.2) |

| >HS | 7 (30.4) | 96 (33.9) | 46 (40.0) | 133 (56.4) | 778 (62.2) | 1,060 (55.6) |

| Private insurance, no. (%) | ||||||

| No | 11 (52.4) | 141 (50.7) | 50 (51.0) | 62 (27.3) | 463 (37.6) | 727 (39.2) |

| Yes | 10 (47.6) | 137 (49.3) | 48 (49.0) | 165 (72.7) | 769 (62.4) | 1,129 (60.8) |

| NA | 2 | 5 | 17 | 9 | 18 | 33 |

| Income, no. (%) | ||||||

| >$50,000 | 5 (22.7) | 80 (29.2) | 29 (26.4) | 110 (48.2) | 553 (45.9) | 777 (42.2) |

| $20,000–$50,000 | 8 (36.4) | 105 (38.3) | 46 (41.8) | 70 (30.7) | 431 (35.7) | 660 (35.9) |

| <$20,000 | 9 (40.9) | 89 (32.5) | 35 (31.8) | 48 (21.1) | 222 (18.4) | 403 (21.9) |

| NA | 1 | 9 | 5 | 8 | 44 | 23 |

| Stage, no. (%) | ||||||

| I | 3 (13.0) | 112 (39.6) | 45 (39.1) | 18 (7.6) | — | 178 (9.3) |

| II | 4 (17.4) | 67 (23.7) | 26 (22.6) | 19 (8.1) | — | 116 (6.1) |

| III | 4 (17.4) | 49 (17.3) | 7 (6.1) | 54 (22.9) | — | 114 (6.0) |

| IV | 12 (52.2) | 55 (19.4) | 37 (32.2) | 145 (61.4) | — | 249 (13.1) |

| Treatment, no. (%) | ||||||

| Chemo + radiation | 15 (65.2) | 52 (18.4) | 9 (7.8) | 78 (33.2) | — | 154 (8.1) |

| Chemo + radiation + surgery | 1 (4.3) | 12 (4.2) | 13 (11.3) | 74 (31.5) | — | 100 (5.2) |

| Radiation only | 4 (17.4) | 97 (34.3) | 5 (4.3) | 15 (6.4) | — | 121 (6.3) |

| Radiation + surgery | 3 (13.0) | 72 (25.4) | 17 (14.8) | 46 (19.6) | — | 138 (7.2) |

| Surgery only | 0 (0.0) | 50 (17.7) | 71 (61.7) | 22 (9.4) | — | 143 (7.5) |

| NA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

HS = high school; NA = not available.

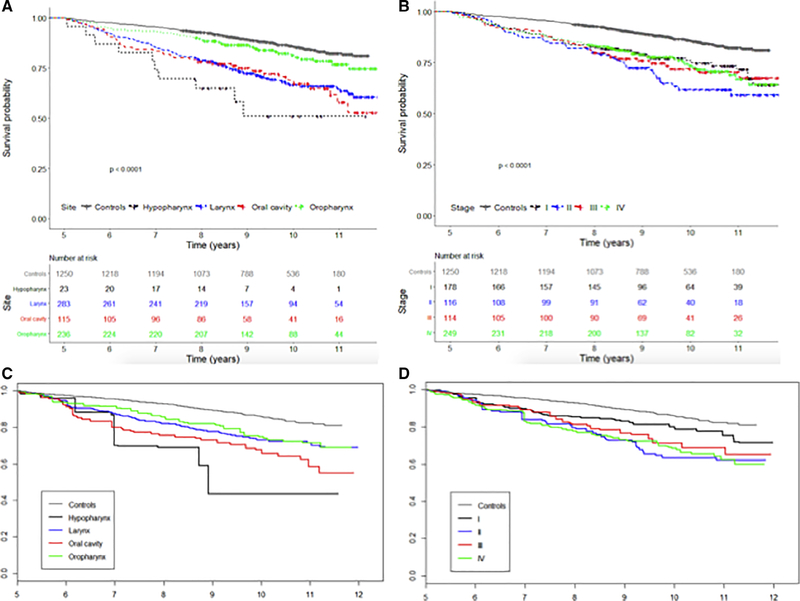

For cases alive at five years, subsequent long-term OS, stratified by site, is shown in Figure 2 and Table II. OS differed between cases and controls, and between different primary sites (P < .01). When stratified by initial overall stage, OS differed between cases and controls (Fig. 2B) (P < .01). The unadjusted survival by stage (Fig. 2B) was heavily influenced by the younger age of HPV+ OPSCC cases that also tended to have higher staging and paradoxically showed worse survival for stage I cases when compared to stages II to IV. When adjusted for age, sex, and race (Fig. 2C), stage I had improved survival when compared to stages II to IV (P < .01), but there was no further stratification between stages II and IV. We also examined whether the lack of survival difference with stratification by initial overall stage was due to the treatment modality and did not find a difference in survival hazard ratio (HR) (Table II).

Fig. 2.

Long-term overall survival of all head and neck squamous cell carcinoma patients alive 5 years after diagnosis stratified by tumor site (A) and initial overall stage (B) compared to age-matched controls. Weighted survival curve by tumor site (C) and by initial survival stage (D) adjusting group to control in terms of age, race, and smoking status. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.laryngoscope.com.]

TABLE II.

Survival of Cases After Initial 5 Years.

| HR (95% CI) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Site | ||

| Control | Referent | |

| Oropharynx | 2.0 (1.4–2.9) | <.01 |

| Larynx | 2.0 (1.5–2.7) | <.01 |

| Oral cavity | 2.7 (1.9–4.0) | <.01 |

| Hypopharynx | 3.6 (1.8–7.0) | <.01 |

| Stage | ||

| Control | Referent | |

| I | 1.6 (1.1–2.3) | <.01 |

| II | 2.4 (1.7–3.5) | <.01 |

| III | 2.4 (1.6–3.6) | <.01 |

| IV | 2.5 (1.8–2.4) | <.01 |

| Treatment | ||

| Control | Referent | |

| Chemo + radiation | 3.2 (2.3–4.4) | <.01 |

| Chemo + radiation + surgery | 1.9 (1.2–3.2) | .01 |

| Radiation only | 2.2 (1.5–3.1) | <.01 |

| Radiation + surgery | 1.6 (1.1–2.4) | .02 |

| Surgery only | 2.1 (1.5–3.1) | <.01 |

HRs were adjusted for race, sex, age, insurance, and smoking status. CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio.

We then stratified cases further by HPV status and compared them to age-matched controls to see if the survival advantage seen in oropharynx cases was due to the younger age of HPV-associated OPSCC cases. P16+ OPSCC cases were termed HPV-associated OPSCC. P16− OPSCC cases were grouped with OC, hypopharynx, and larynx and termed non–HPV-associated HNSCC. Basic characteristics for cases and age-matched controls after stratification by HPV status are shown in Table III. When compared to other cancer cases, those with HPV-associated OPSCC were more likely to be white, younger, have private insurance, and an income greater than $50,000 annually. There was an approximate 4:1 male to female dominance in both groups. Most cases with non–HPV-associated HNSCC (87%) had a greater than 10 pack-years smoking history.

TABLE III.

Patient Characteristics of Cases Surviving at 5 Years After Diagnosis Stratified by HPV Status and Age-Matched Controls.

| Non–HPV-Associated HNSCC, n = 458 | Non–HPV-Associated HNSCC Controls, n = 912 | HPV-Associated OPSCC, n = 122 | HPV-Associated Controls, n = 366 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at enrollment, yr, no. (%) | ||||

| ≤50 | 67 (19.6) | 131 (19.2) | 43 (37.2) | 133 (36.3) |

| 51–60 | 181 (52.9) | 344 (50.3) | 62 (51.2) | 193 (52.7) |

| ≥66 | 94 (27.5) | 209 (30.5) | 14 (11.6) | 40 (10.9) |

| Sex, no. (%) | ||||

| Male | 345 (75.3) | 628 (68.9) | 99 (81.1) | 253 (69.1) |

| Female | 113 (24.7) | 284 (31.1) | 23 (18.9) | 113 (30.9) |

| Race, no. (%) | ||||

| White | 319 (69.7) | 711 (78.0) | 111 (91.7) | 276 (75.4) |

| Black | 131 (28.6) | 191 (20.9) | 4 (3.3) | 86 (23.5) |

| Other | 8 (1.7) | 10 (1.1) | 6 (5.0) | 4 (1.1) |

| Smoking, no. (%) | ||||

| Never | 25 (5.5) | 310 (34.0) | 30 (24.8) | 135 (36.9) |

| <10 pack-years | 36 (7.9) | 231 (25.4) | 25 (20.7) | 92 (25.1) |

| ≥10 pack years | 396 (86.7) | 370 (40.6) | 66 (54.5) | 139 (38.0) |

| Missing | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Alcohol use, no. (%) | ||||

| <1 drink/week | 69 (15.6) | 294 (32.5) | 24 (19.8) | 121 (33.2) |

| ≥1 drink/week | 374 (84.4) | 610 (67.5) | 97 (80.2) | 243 (66.8) |

| Missing | 15 | 8 | 1 | 2 |

| Income, no. (%) | ||||

| >$50,000 | 121 (27.4) | 425 (48.1) | 64 (52.5) | 185 (50.5) |

| $20,000–$50,000 | 172 (39.0) | 302 (34.2) | 41 (33.6) | 119 (32.5) |

| <$20,000 | 148 (33.6) | 157 (17.8) | 12 (9.8) | 57 (15.6) |

| Missing | 17 | 28 | 5 | 5 |

| Private insurance, no. (%) | ||||

| No | 217 (50.1) | 309 (34.3) | 26 (21.5) | 80 (21.9) |

| Yes | 216 (49.9) | 592 (65.7) | 89 (73.6) | 281 (76.8) |

| Missing | 25 | 11 | 6 | 5 |

| Surgery, no. (%) | ||||

| No | 186 (54.4) | 684 (100) | 44 (36.4) | 366 (100) |

| Yes | 156 (45.6) | 77 (63.6) | ||

| Radiation, no. (%) | ||||

| No | 57 (16.7) | 684 (100) | 5 (4.1) | 366 (100) |

| Yes | 285 (83.3) | 116 (95.9) | ||

| Chemotherapy, no. (%) | ||||

| No | 242 (70.8) | 684 (100) | 43 (35.5) | 366 (100) |

| Yes | 100 (29.2) | 78 (64.5) | ||

HNSCC = head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; HPV = human papillomavirus; OPSCC = oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma.

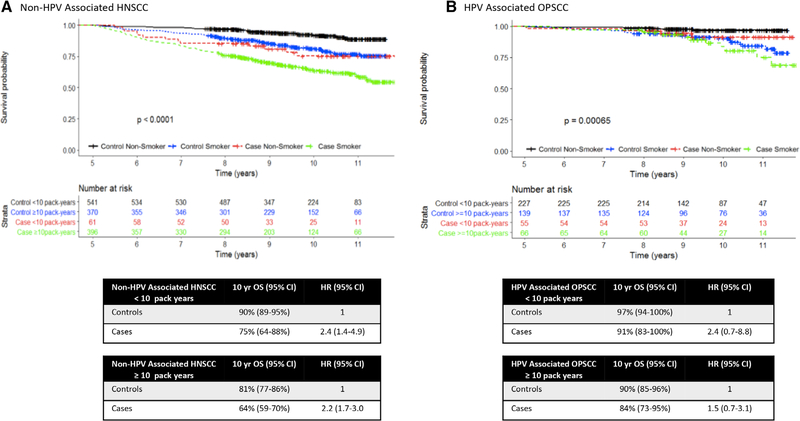

In both HPV-associated OPSCC and non–HPV-associated HNSCC groups, cases with a ≥ 10 pack-years smoking history had worse OS than those with a < 10 pack-years smoking history (Fig. 3). After 5 years, OS for HPV-associated OPSCC cases was worse than their age-matched controls, even after stratification by smoking status (Fig. 3). Among those with a < 10 pack-years smoking history, cases had a 2.4 times increased risk of death when compared to controls. For those with a ≥ 10 pack-years smoking history, cases had 1.5 times increase when compared controls. Similarly, when stratified by smoking status, non–HPV-associated HNSCC cases showed decreased OS when compared to their age-matched controls, with a 2.2 to 2.4 times increased risk of death.

Fig. 3.

Overall survival of (A) non–HPV-associated HNSCC and (B) HPV-associated OPSCC cases after 5 years stratified by smoking status (<10 pack-years vs. >10 pack-years) with associated 10-year OS and HRs. HRs indicate risk of death of cases when compared to controls with the same smoking status. CI = confidence interval; HNSCC = head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; HPV = human papillomavirus; HR = hazard ratio; OPSCC = oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma; OS = overall survival. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.laryngoscope.com.]

DISCUSSION

HNSCC cases that survive beyond 5 years after initial diagnosis continue to have decreased OS when compared to their age-matched non-cancer controls, even after adjusting for smoking status. Primary tumor site, HPV positivity in OPSCC, smoking history and initial stage all impact OS after 5 years.

Our findings are largely in line with the few previous studies reporting long-term survival in HNSCC but differ in terms of OPSCC where HPV status plays an important role.26,27 Both studies evaluated cases diagnosed pre-1994, whereas ours spanned from 2002 to 2006. In the intervening decade between the previous studies and ours, the rate and proportion of HPV-associated OPSCC rose dramatically. The 2004 study using the Ontario Cancer Registry and the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) databases found that among patients who survived 5 years after diagnosis, 10-year survival was significantly decreased from that expected of the general population.26 The 10-year survival in SEER cases alive at 5 years reported in the Skarsgard et al.26 study is comparable to what we report, with the notable difference of the oropharynx site. Their reported 10-year survival for oropharynx (57%) is similar to our reported survival for p16− OPSCC (56%) but worse than p16+ OPSCC (87%). The 2014 study examined long-term survival to 25 years and also reported that survival beyond 5 years is particularly poor for oropharynx (14% at 15 years).27 Their reported survival is particularly low because they did not limit the study to those alive at 5 years. Our study confirms that overall long-term survival for HPV-positive OPSCC is substantially improved compared to HPV-negative disease in the long term and warrants separate analysis.

An important finding of this study is that although stage I cases had improved survival, stages II to IV did not differ significantly in long-term survival in cases alive 5 years after diagnosis. This finding suggests that after treatment and survival beyond the first 5 years, initial tumor and nodal burden may be less important determinants of OS. In prior studies, mortality directly attributable to the initial HNSCC stabilized after 5 years but remained a leading cause of death.28 Second primaries and cardiovascular disease followed as the next most common causes of death when mortality was not directly attributable to the primary HNSCC, with increasing age being the main risk factor.28,29 The minimal impact of overall staging on OS suggests that after 5 years, factors not directly attributable to the primary HNSCC, such as second primaries and cardiovascular disease, may become more important determinants of mortality. Another possible explanation for the lack of survival difference between stages II-IV is that nodal status heavily influenced the 7th edition AJCC staging of OPSCC. Numerous studies have questioned the predictive accuracy of this approach in HPV-associated OPSCC,30–32 leading to major changes to the staging guidelines in the 8th edition.33 For HPV-associated OPSCC, the lack of correlation between long-term OS and initial overall staging may reflect the weaknesses of the previous TNM staging system. Furthermore, low numbers of cases with stages I to III HPV-associated OPSCC in the CHANCE at the onset may have further weakened the analysis.

In both HNSCC cases, population, smoking, and age heavily influenced the risk of developing cancer, cardiovascular disease, and pulmonary disease. Together, these represent the top three leading causes of death in the United States and are responsible for >50% of all causes of mortality.34 Smoking cessation has been shown to be independently associated with improvements in OS and disease-specific survival for both HPV-associated and non–HPV-associated disease.10,17 Unsurprisingly, we found that smoking has a major impact on long-term HNSCC survival, regardless of HPV status. Numerous studies have shown that the survival benefit seen in HPV-positive disease decreases with concomitant history of heavy smoking.17,35 We stratified our cases alive after 5 years by smoking status and compared them to age-matched noncancer controls in an attempt to better isolate the impact of HNSCC and its treatment on long-term survival. Roughly half of our HPV-associated OPSCC cases smoked ≥10 pack-years, and 25% were never smokers. HPV-associated OPSCC cases had a higher proportion reporting more than one alcoholic drink per week when compared to age-matched controls (80.2% vs. 66.8%) but did not differ in terms of income distribution or percentage with insurance status. After stratifying by smoking history and adjusting for sex and race, cases with HPV-associated OPSCC had a 1.5 fold increase in risk of death when compared to age-matched, nonsmoking controls. The remaining survival disadvantage for those previously diagnosed with a HNSCC may be due to genetic predisposition to malignancy, long-term morbidity of having been diagnosed with HNSCC, and other late manifestations of the disease. Whether these risk factors can be better identified or modified through changing treatment regimens warrants further investigation.

This study’s main strength is the use of a large, population-based case-control study with a diverse population, which allows the use of the controls to establish baseline survival. However, this study also has some important limitations. First, power was limited by low number of cases with <10-pack years smoking history. There was a higher proportion of never smokers to <10 pack-years smokers in our controls than in the cases, but we grouped these together due to the overall low number of <10 pack-years smokers. The study is also limited by the exclusion of oropharyngeal cases where HPV status was unavailable. Furthermore, the prognostic value of HPV/p16 status in nonoropharyngeal sites is unclear. It may have been more ideal to limit the comparison of p16+ OPSCC to p16− OPSCC only; however, a small number of p16− OPSCC prevented us from being able to do so reliably. Another major limitation is the lack of follow-up data regarding disease status and medical comorbidities. The objective of the CHANCE was to find etiologic factors of HNSCC; thus, the data were collected at baseline but not at subsequent points. Mortality was obtained from the NDI, which is reliable for death but limited in terms of cause of death. Often, there are competing and overlapping causes of mortality in HNSCC cases. Our study looked only at OS but was not able to examine disease-specific survival. In addition to cardiovascular disease, cancer, and pulmonary disease, studies have also suggested that chronic liver disease and suicide are increased among HNSCC cases when compared to the general population.29 The control group was identified and matched at study onset only; subsequent details regarding smoking and medical comorbidities were not available. Lastly, we were unable to fully stratify by site, stage, and treatment due to small numbers. Thus, we were limited in our ability to tease out the interplay between these important factors. The results from this study ought to be interpreted with these important limitations in mind. More research is needed to clarify long-term causes of death in both HPV-associated and non–HPV-associated HNSCC cases to ultimately guide efforts to improve long-term survival.

CONCLUSION

Long-term HNSCC survivors are a heterogeneous group at increased risk of death from numerous socioeconomic, lifestyle, health, disease, and treatment factors. For cases alive at 5 years, OS over the subsequent 5 years does not normalize to that of the general public, even for nonsmoking cases with HPV-associated OPSCC. Whether this mortality is due to late toxicity from treatment, genetic predisposition to disease or modifiable risk factors that lead to the cancer remains to be seen. Our results provide both clinicians and patients with important prognostic information. It also underscores the importance of ongoing specialized support, smoking cessation counseling, and head and neck surveillance for this vulnerable group of patients, even after cure has been achieved.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA90731) and a grant from Lineberger Integrated Training in Cancer Model Systems (T32CA009156).

Footnotes

The authors have no other funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Eugenie Du, Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, U.S.A..

Angela L. Mazul, Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, St. Louis, Missouri, U.S.A..

Doug Farquhar, Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, U.S.A..

Paul Brennan, International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France.

Devasena Anantharaman, International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France; Cancer Research Program (HPV Research), Rajiv Gandhi Centre for Biotechnology, Trivandrum, India.

Behnoush Abedi-Ardekani, International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France.

Mark C. Weissler, Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, U.S.A.; Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, U.S.A.

David N. Hayes, Department of Epidemiology, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, U.S.A.; Department of Medicine, Division of Hematology and OncologyUniversity of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, Tennessee, U.S.A.

Andrew F. Olshan, Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, U.S.A.; Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, U.S.A. Department of Epidemiology, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, U.S.A.

Jose P. Zevallos, Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, St. Louis, Missouri, U.S.A.; Department of Epidemiology, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, U.S.A.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1.Fitzmaurice C, Allen C, Barber RM, et al. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:524–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin 2017;67:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoffman HT, Karnell LH, Funk GF, Robinson RA, Menck HR. The National Cancer Data Base report on cancer of the head and neck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1998;124:951–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boysen M, Natvig K, Winther FO, Tausjo J. Value of routine follow-up in patients treated for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. J Otolaryngol 1985;14:211–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blot WJ, McLaughlin JK, Winn DM, et al. Smoking and drinking in relation to oral and pharyngeal cancer. Cancer Res 1988;48:3282–3287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wyss A, Hashibe M, Chuang SC, et al. Cigarette, cigar, and pipe smoking and the risk of head and neck cancers: pooled analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium. Am J Epidemiol 2013;178:679–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Divaris K, Olshan AF, Smith J, et al. Oral health and risk for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: the Carolina Head and Neck Cancer Study. Cancer Causes Control 2010;21:567–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldenberg D, Lee J, Koch WM, et al. Habitual risk factors for head and neck cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004;131:986–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mazul AL, Taylor JM, Divaris K, et al. Oral health and human papillomavirus-associated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer 2017;123:71–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Platek AJ, Jayaprakash V, Merzianu M, et al. Smoking cessation is associated with improved survival in oropharynx cancer treated by chemoradiation. Laryngoscope 2016;126:2733–2738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shiels MS, Gibson T, Sampson J, et al. Cigarette smoking prior to first cancer and risk of second smoking-associated cancers among survivors of bladder, kidney, head and neck, and stage I lung cancers. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:3989–3995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Imhoff LC, Kranenburg GG, Macco S, et al. Prognostic value of continued smoking on survival and recurrence rates in patients with head and neck cancer: a systematic review. Head Neck 2016;38(suppl 1):E2214–E2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, et al. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:4294–4301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benard VB, Johnson CJ, Thompson TD, et al. Examining the association between socioeconomic status and potential human papillomavirus-associated cancers. Cancer 2008;113:2910–2918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D’Souza G, Kreimer AR, Viscidi R, et al. Case-control study of human papillomavirus and oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med 2007;356:1944–1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Settle K, Posner MR, Schumaker LM, et al. Racial survival disparity in head and neck cancer results from low prevalence of human papillomavirus infection in black oropharyngeal cancer patients. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2009;2:776–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:24–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benson E, Li R, Eisele D, Fakhry C. The clinical impact of HPV tumor status upon head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Oral Oncol 2014;50:565–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hakenewerth AM, Millikan RC, Rusyn I, et al. Effects of polymorphisms in alcohol metabolism and oxidative stress genes on survival from head and neck cancer. Cancer Epidemiol 2013;37:479–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edge S, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene F, Trotti A, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Handbook. New York, NY: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oguejiofor KK, Hall JS, Mani N, et al. The prognostic significance of the biomarker p16 in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2013;25:630–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D’Souza G, Anantharaman D, Gheit T, et al. Effect of HPV on head and neck cancer patient survival, by region and tumor site: a comparison of 1362 cases across three continents. Oral Oncol 2016;62:20–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anantharaman D, Abedi-Ardekani B, Beachler DC, et al. Geographic heterogeneity in the prevalence of human papillomavirus in head and neck cancer. Int J Cancer 2017;140:1968–1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grambsch PM, Therneau TM. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model. New York, NY: Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Therneau TM. A package for survival analysis in R version 2.38. Available at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survival.

- 26.Skarsgard DP, Groome PA, Mackillop WJ, et al. Cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract in Ontario, Canada, and the United States. Cancer 2000; 88:1728–1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tiwana MS, Wu J, Hay J, Wong F, Cheung W, Olson RA. 25 year survival outcomes for squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck: population-based outcomes from a Canadian province. Oral Oncol 2014;50:651–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baxi SS, Pinheiro LC, Patil SM, Pfister DG, Oeffinger KC, Elkin EB. Causes of death in long-term survivors of head and neck cancer. Cancer 2014;120: 1507–1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Massa ST, Osazuwa-Peters N, Christopher KM, et al. Competing causes of death in the head and neck cancer population. Oral Oncol 2017;65:8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dahlstrom KR, Garden AS, William WN Jr, Lim MY, Sturgis EM. Proposed staging system for patients with HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer based on nasopharyngeal cancer N categories. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34:1848–1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang SH, Xu W, Waldron J, et al. Refining American Joint Committee on Cancer/Union for International Cancer Control TNM stage and prognostic groups for human papillomavirus-related oropharyngeal carcinomas. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:836–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Sullivan B, Huang SH, Su J, et al. Development and validation of a staging system for HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer by the International Collaboration on Oropharyngeal cancer Network for Staging (ICON-S): a multicentre cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:440–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lydiatt WM, Patel SG, O’Sullivan B, et al. Head and neck cancers-major changes in the American Joint Committee on cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin 2017;67:122–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2015: With Special Feature on Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. Report No.: 2016–1232. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang MB, Liu IY, Gornbein JA, Nguyen CT. HPV-positive oropharyngeal carcinoma: a systematic review of treatment and prognosis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2015;153:758–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.