Abstract

Although studies have shown links between minority stress and mental health (e.g., Meyer, 2003), there is little research explaining this association. Research has suggested that adequate coping skills might protect youth from the negative impact of stress (Compas et al., 2017). Thus, we aimed to examine: 1) whether associations between minority stress and depressive symptoms occurred through mechanisms of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness, and 2) whether these associations were dependent on level of problem-solving coping (moderated mediation). Using an online survey of 267 sexual minority youth from the Netherlands (16-22 years; 28.8% male), the results show an indirect relationship of sexual orientation victimization and internalized homophobia with depressive symptoms occurring through perceived burdensomeness; for both males and females. Problem-solving coping skills did not significantly moderate the aforementioned indirect relationships. These results have implications for prevention and intervention work that currently focuses on social isolation rather than perceived burdensomeness.

Keywords: minority stress, interpersonal-psychological theory, depressive symptoms, coping, sexual minority youth

The experience of stress associated with being a sexual minority (minority stress) has been related to poor mental health and is often considered as an explanation for the mental health disparities between sexual minority and non-sexual minority individuals, particularly related to depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation (Meyer, 2003). The mechanisms by which the internalization of sexual minority stress affects mental health, however, is just beginning to receive research attention. Drawing from interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide (Joiner et al., 2009), recent empirical work has identified the experience of thwarted belongingness and the perception of being a burden to others as an important explanation for the relationship between minority stress and mental health (Baams, Russell, & Grossman, 2015; Plöderl et al., 2014). Sexual minority youth are thought to be particularly prone to a thwarted sense of belonging and the perception of being a burden to others, in response to minority stressors (Baams et al., 2015). At the same time, adolescents and young adults with optimal coping skills process and handle stressful situations in more functional ways and are not affected by stressors to the same extent as those with lower levels of these skills (Compas et al., 2017; Lazarus, 1993; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Thus, having a high level of problem-solving coping skills is thought to protect against the development of depression (Seiffge-Krenke & Klessinger, 2000) and may be an important resource among sexual minority youth who experience minority stress. Research during adolescence (10–19 years old) and young adulthood (18–35 years old) is critical because during this time youth often start to disclose their sexual orientation to others (Martos, Nezhad, & Meyer, 2015), and developments during this period can have negative consequences for long-term mental health disparities (Mustanski, 2015). The present research was designed to test: (1) the indirect relationship between three aspects of minority stress (sexual orientation victimization; expected rejection; internalized homophobia) and depressive symptoms, through thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness, and (2) whether these indirect associations were dependent on level of problem-solving coping skills.

Minority Stress and the Interpersonal-Psychological Theory

Sexual minority individuals can experience stressors related to their minority status. These unique, often chronic, stressors are called minority stressors. Meyer (2003) uses the distal-proximal distinction as a means to characterize different processes of minority stress. Distal processes such as prejudice and victimization are external to the individual but depend on proximal processes involving the individual’s subjective appraisal of the situation. Meyer (2003) delineated three processes of minority stress related to sexual minorities that range from the distal to proximal: external, objective stressful events and conditions, expectations of and vigilance for such events, and internalization of negative societal attitudes.

Experienced prejudice and victimization directed at sexual minority youth’s (presumed) sexual identity is common (Balsam, Rothblum & Beauchaine, 2005) and related to mental health problems (e.g., Burton, Marshal, Chisolm, Sucato, & Friedman, 2013). Sexual orientation victimization has been conceptualized as experiences with, for example, verbal and physical violence because the youth was lesbian, gay, or bisexual, or someone thought they were (D’Augelli, 2002; D’Augelli, Grossman, & Starks, 2006; Pilkington & D’Augelli, 1995). More proximal stressors are also found to relate to sexual minority youth’s health. For example, the expectation of rejection and the vigilance that may follow has been related to anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation (Kelleher, 2009). Further, internalized homophobia, defined as “the […] person’s direction of negative social attitudes toward the self, leading to a devaluation of the self and resultant internal conflicts and poor self-regard” (Meyer & Dean, 1998, p. 161), is related to higher levels of depression and anxiety (see Newcomb & Mustanski, 2010 for a review). Although these stressors have been related to negative (mental) health outcomes such as depression and suicidality (Meyer, 2003; Russell & Fish, 2016), until recently there has been little attention for explanatory mechanisms of these associations. One proposed mechanism comes from the interpersonal-psychological theory, which has been applied to both depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation (Baams et al., 2015).

In the interpersonal-psychological theory, two factors are identified that are important in the development of depression, suicidal ideation, and suicidal behavior: perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness (Joiner et al., 2009). First, perceived burdensomeness is defined as the perception of being a burden to friends and family. This perception is thought to develop when the need for social competence is unmet (Van Orden, Cukrowicz, Witte, & Joiner, 2012). Feeling like a burden has long been suggested to be prevalent among sexual minority youth and (young) adults (e.g., Diaz, Ayala, Bein, Henne, & Marin, 2001; Oswald, 1999) and may develop in response to others’ negative reactions to “coming out” experiences (Hilton & Szymanski, 2011). Second, thwarted belongingness or a sense of social isolation has also been shown to be prevalent among sexual minority individuals and can develop as a function of rejection and victimization (e.g., Baams et al., 2015). Thwarted belongingness is described as a psychological state that develops when the need to belong is unmet, this may refer to a lack of connectedness to one’s family, community, and also society more broadly (Van Orden et al., 2012). Thwarted belongingness and social isolation have also been related to mental health problems (Diaz et al., 2001; Hatzenbuehler, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Dovidio, 2009).

To our knowledge there are currently three studies that combine the interpersonal-psychological theory and the minority stress framework to understand sexual minority mental health. One study among a sample of Bavarian sexual minority adults showed that internalized homophobia was related to perceived burdensomeness, and perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness were associated with higher levels of depression (Plöderl et al., 2014). A study among college students in the United States showed that the association of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness with suicidal ideation was conditional on the level of perceived or anticipated rejection due to sexual identity (Hill & Pettit, 2012). These first two studies highlight the link between perceived burdensomeness and mental health outcomes for sexual minorities, and the importance of minority stress in these relations.

Currently, only one study has used the interpersonal-psychological theory to examine the mechanism behind the associations between minority stress and mental health (Baams et al., 2015), with results pointing to an important role of perceived burdensomeness as a key mechanism. This study of LGB self-identified youth (ages 15–21) in the United States assessed two minority stressors: sexual orientation victimization and stress around coming-out experiences. The results showed that the association between sexual orientation victimization with depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation could be explained by higher levels of perceived burdensomeness. Further, for girls, the relation between coming-out stress and depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation could be explained by higher levels of perceived burdensomeness. Thus, this recent study shows the importance of a minority stressor such as victimization for both boys and girls, and the role that perceived burdensomeness plays in relation to depression and suicidal ideation. Further, coming-out stress was found to function similarly, but only for girls (Baams et al., 2015).

Problem-Focused Coping Skills

After decades of research on minority stress and mental health, and the now growing field of research on mechanisms in these associations, there is still little attention for individual factors that may moderate the impact of minority stress. Particularly problem-focused coping has been found to help regulate stressful responses and reduce negative feelings related to stressful or prejudice events (Allport, 1954; Clarke, 2006; Gonzales, Tein, Sandler, & Friedman, 2001; Silk, Steinberg, & Morris, 2003), and thus the associations between minority stress and health outcomes may be dependent on problem-focused coping skills. Problem-focused coping is a form of active coping and includes responses to stress such as coming up with solutions, seeking information, and taking action (Lazarus, 1993; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Effective coping skills have been found to attenuate the effects of stress on a host of psychological symptoms (e.g., Clarke, 2006; Compas et al., 2001; Compas et al., 2017; Penley, Tomaka, & Wieke, 2002). As such, adequate coping skills have also been suggested to ameliorate the association of minority stress with health outcomes (Meyer, 2003). For example, one study found that among lesbian and gay undergraduate students, the association between perceived stigma and depressive symptoms was conditional upon problem-solving coping strategies (Talley & Bettencourt, 2011). Knowing the ways that minority stress compromises mental health, assessing potential protective factors such as coping skills would be a fruitful avenue, especially when those specific coping skills can be learned, or the efficacy of coping can be improved in prevention and intervention work. Intervention may prove to be particularly effective when youth acquire skills that ameliorate the impact of uncontrollable stressors, such as minority stress.

Sex Differences, Minority Stress, and Depressive Symptoms

Previous research has indicated that there are important mean level-differences between males and females in terms of minority stress and depression, as well as the (indirect) relations between minority stress and depression (Baams et al., 2015). For example, a study among U.S. youth showed that females, on average, reported higher levels of depression and males reported higher levels of sexual orientation victimization (Baams et al.). In addition, for both males and females perceived burdensomeness was found to explain the relation between sexual orientation victimization and depression and suicidal ideation, while for females coming-out stress was also a mediator of these relationships (Baams et al.). Gender differences in coping strategies in relation to depressive symptoms have also been found (Malooly, Flannery, Ohannessian, & McCauley, 2017). In response to these mean-level sex differences and differential associations for males and females, we also examine whether the predictive models equally apply for males and females.

Present Study

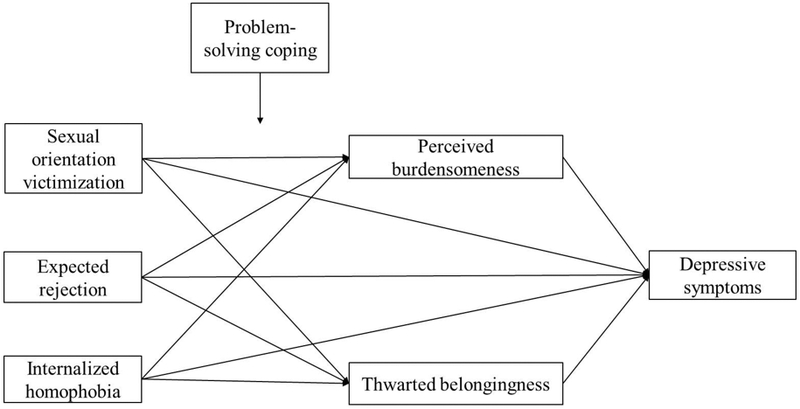

Consistent with previous theoretical and empirical work (Baams et al., 2015; Joiner et al., 2009; Lazarus, 1993; Meyer, 2003), we hypothesize an indirect relation between three aspects of minority stress (sexual orientation victimization; expected rejection; internalized homophobia) and depressive symptoms, through perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness. Further, we hypothesize that these indirect associations are dependent on the level of problem-solving coping skills (see Figure 1 for conceptual model). Although we have no hypotheses for sex differences, we also explore a multigroup model for males and females. These associations are examined in a sample of 267 sexual minority youth aged 16 to 22 years old.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model. Predicting depressive symptoms from minority stress via perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness; indirect relationships moderated by problem-solving coping skills.

Because previous research has indicated that age (Baams et al., 2015) and level of same-sex attraction (van Beusekom, Baams, Bos, Overbeek, & Sandfort, 2016) may correlate with victimization and psychological distress we control for these factors in the analyses.

Method

Procedure and Participants

Data came from a larger project (masked version) conducted in The Netherlands in the fall of 2014. Youth were asked to participate via advertisements on several Dutch LGBTQ-directed websites. Prior to completing the online survey youth received information describing the aims of the study, confidentiality safeguards, and procedures for declining or ending participation. After giving online informed consent youth completed an online survey. Participating youth were entered into a raffle to win a gift certificate. This study was approved by the ethics board of (masked version).

Of the initial sample (N = 364), 96 youth did not report their sex, and one female participant reported a heterosexual sexual identity with no same-sex attractions. These participants were excluded for the current analyses, resulting in a total sample of 267 youth (28.8% male as reported in passport or identification; Mage = 17.61, SD = 1.87, ranging from 16 to 22 years). Most participants had a Dutch (61.8%) or Western cultural background (6.4%). Participating youth were enrolled in different educational tracks, with approximately 20.6% of youth in vocational education programs and 45.8% of the adolescents in college/university (preparatory) programs. We assessed sexual orientation with two variables: 1) sexual attraction, and 2) sexual identity). Participants’ responses to the sexual attraction question ranged from only other-sex attractions to only same-sex attractions. A total of 18.7% reported their sexual identity as “gay,” 30.3% as “lesbian,” 22.1% as “bisexual,” and 2.2% as “queer,” 6.3% reported a sexuality identity not listed, and 20.3% skipped the question about sexual identity.

Material

Sexual orientation victimization.

A shortened version of the Sexual Orientation Victimization Scale was translated and used to assess life-time experiences of sexual orientation victimization (D’Augelli et al., 2006). This scale has demonstrated reliability and validity across various adolescent and young adult populations (Baams et al., 2015; D’Augelli et al., 2008; Dragowski, Halkitis, Grossman, & D’Augelli, 2011). The original scale consisted of six items and four were selected for the current study. Two items asking about “threats with a knife/gun/other weapon” and “sexually attacked/raped,” were excluded because these items are sensitive in nature and might require intervention, which was not possible with the current anonymous survey design. Participants were asked about their lifetime experience with “verbal insults,” “threats of physical violence,” “objects thrown at you,” and “punched, kicked, or beaten,” because of them being gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender or others thinking they were gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender. Participants could answer on four-point scales (0 = never and 3 = three or more times). A mean score of the four items was used for the current analysis (α = .70).

Expected rejection.

A scale developed by Bos, Van Balen, and van den Boom (2004) was used to assess expected rejection. This scale has demonstrated reliability and validity across various adolescent and young adult Dutch-speaking populations (Baams, Bos, & Jonas, 2014; Bos et al.; Sandfort, 1997). A sample item was “I am afraid to be made fun of because of my sexual orientation.” Participants could answer on five-point scales (1 = not worried at all and 5 = very worried). For the current study, the mean score of 8 items was used (α = .90).

Internalized homophobia.

A scale developed by Bos and colleagues (2004) was used to assess internalized homophobia, the mean score of 5 items was used (α = .79). Similar to the scale for expected rejection, the scale to assess internalized homophobia has demonstrated reliability and validity across various adolescent and young adult Dutch-speaking populations (Baams, Bos, & Jonas, 2014; Bos et al.; Sandfort, 1997). A sample item was “Because I have homosexual/lesbian/bisexual feelings, I don’t feel like myself.” Participants could answer on five-point scales (1 = fully disagree and 5 = fully agree).

Perceived burdensomeness.

To assess perceived burdensomeness, the seven-item subscale of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire was translated into Dutch (Van Orden et al., 2008). This scale has demonstrated reliability and validity across various adolescent and (young) adult populations (Baams et al., 2015; Hill & Pettit, 2012; Joiner et al., 2009; Van Orden et al.). A sample item was “These days, I think the people in my life wish they could be rid of me.” Participants could answer on seven-point scales (1 = not at all true for me and 7 = very true for me). A mean score of these items was used for the current analyses (α = .92).

Thwarted belongingness.

To assess thwarted belongingness, the five-item subscale of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire was translated into Dutch (Van Orden et al., 2008). This scale has also demonstrated reliability and validity across various adolescent and (young) adult populations (Baams et al., 2015; Hill & Pettit, 2012; Joiner et al., 2009; Van Orden et al.). A sample item was “These days, I feel disconnected from other people,” participants could answer on seven-point scales (1 = not at all true for me and 7 = very true for me). A mean score of these items was used for the current analyses (α = .71).

Depressive symptoms.

To assess depressive symptoms in the last two weeks, the 6-item Depressive Mood List was used (Kandel & Davies, 1982, translated into Dutch by Dékovic, 1996). The translated scale has demonstrated reliability and validity across various Dutch-speaking adolescent and young adult populations (Dekoviç, 1999; Doornwaard, van den Eijnden, Baams, Vanwesenbeeck, & ter Bogt, 2016; Noom, Dekoviç, & Meeus, 1999). A sample item was “I felt too tired to do anything.” Participants could answer on five-point scales (1 = never and 5 = always). A mean score of these items was used for the current analyses (α = .85).

Problem-solving coping skills.

To assess the level of problem-solving coping skills, the mean of the five-item problem-solving coping skills subscale from the Coping Strategy Indicator was used and translated into Dutch (Amirkhan, 1990). This scale has demonstrated reliability and validity across various young adult populations (Ager & Maclachlan, 1998; Bijtebier & Vertommen, 1997). Participants were asked how often they responded in a certain manner to stressful situations. A sample item was “Tried to solve the problem.” Participants could answer on three-point scales (1 = not at all and 3 = a lot) (α = .68).

Same-sex attraction.

To assess youths’ levels of same-sex attraction, one item was used: “Rate on the following scale to what extent you are attracted to boys or girls.” Answers ranged on a ten-point scale (1 = I’m attracted to men only and 9 = I’m attracted to women only, 10 = I’m not attracted to men or women). Zero participants reported being attracted to neither men nor women. Scores for male adolescents were recoded so that higher scores indicated a higher level of same-sex attraction. Thus, in the present sample scores could range from 1 to 9.

Analysis Strategy

With univariate and multivariate analyses of variance, sex differences in the key variables were tested. Further, bivariate correlations were examined to assess the associations between the key variables. To test the direct relations between the three indicators of minority stress and depressive symptoms, a regression (path) analysis was performed in Mplus version 7.2 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2012) using mean (manifest) variables created in SPSS version 20, controlling for age and same-sex attraction. To test whether the relationship between minority stress and depressive symptoms occurred through perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness, indirect effects were added (bootstrapped; boot=5000) using manifest variables in Mplus. Significance of indirect relations were inferred by the bootstrapped confidence intervals (BCI) not including zero. Missing (mean) values were handled with full information maximum likelihood. All missing values of key variables were missing completely at random. Item-level missingness ranged from 25.0–31.3% and scale missingness ranged from 24.7–30.7%.

To test moderation of the indirect relations by problem-solving coping skills (moderated mediation), the MODEL CONSTRAINT option was used in Mplus to evaluate the moderated mediation index, following suggestions by Hayes (2015). This option allows for the testing whether the indirect relationship of minority stress and depressive symptoms through perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness is moderated by problem solving coping skills (all continuous variables were centered).

Model fit.

To test whether males and females differed in the aforementioned associations, we tested multigroup models. We first constrained all regression paths to be equal across male and female youth, and then we unconstrained paths to be estimated freely. We compared model fit based on the root mean squared error of approximation fit index (RMSEA; i.e., lower values indicate better fit), the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), and Bentler’s Comparative Fit Index (CFI; i.e., higher values indicate better fit), as well as a chi-square differences test. The indirect model in which all regression paths were constrained to be equal across males and females showed a good fit (RMSEA = .052, TLI = .939, CFI =.970), and the fit statistics were better compared to the unconstrained model (RMSEA = .109, TLI = .731, CFI = .993). This was confirmed by the chi-square difference test (χ2diff = 21.87, df = 17, p = .190). Considering these findings, we assessed male and female youth together.

To address potential differences between youth with various sexual identities, we tested multigroup models for the three largest groups (lesbian, gay, and bisexual). These models had a poor fit (RMSEA = .113 - .183, TLI = .423).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations of the key variables for male and female youth separately. There were no significant sex differences in levels of sexual orientation victimization, expected rejection, internalized homophobia, perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, depressive symptoms, problem-solving coping skills, and age; ps > .05. Male youth did report significantly higher levels of same-sex attraction compared to female youth, F(1, 213) = 6.65, p = .011, η2p = .031.

Table 1.

Bivariate Correlations Between Key Variables, Means, SDs, and Range of Key Variables for Male and Female Youth

| Male | Female | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | M (SD) | M (SD) | Range | |

| 1. Age | -- | 17.47 (1.64) | 17.67 (1.95) | 16-22 | |||||||

| 2. Same-sex attraction | .15* | -- | 7.82 (1.32) | 7.19 (1.73)a | 1-9 | ||||||

| 3. Sexual orientation victimization | .01 | .06 | -- | 1.40 (0.38) | 1.33 (0.43) | 1-3 | |||||

| 4. Expected rejection | −.27*** | −.15* | .25*** | -- | 2.44 (1.08) | 2.47 (1.05) | 1-5 | ||||

| 5. Internalized homophobia | −.13 | −.14 | .00 | .46*** | -- | 1.83 (0.77) | 1.98 (0.91) | 1-4.60 | |||

| 6. Perceived burdensomeness | −.25** | −.14 | .31*** | .30*** | .29*** | -- | 2.34 (1.42) | 2.71 (1.50) | 1-7 | ||

| 7. Thwarted belongingness | −.19** | −.05 | .14 | .30*** | .31*** | .48*** | -- | 3.18 (1.26) | 3.33 (1.25) | 1-7 | |

| 8. Depressive symptoms | −.16* | −.19** | .19* | .25** | .26*** | .66*** | .37*** | -- | 2.87 (0.88) | 3.12 (0.85) | 1-5 |

| 9. Problem-solving coping skills | .03 | .04 | .02 | .05 | .09 | −.05 | −.05 | .03 | 3.37 (0.77) | 3.26 (0.73) | 1.40-5 |

Significant difference between male and female youth.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001

Several bivariate correlation analyses were performed to assess the relations between the key variables in the current study (see Table 1). The results show that perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness were interrelated, and related to a higher level of minority stress. Youth who reported a higher level of depressive symptoms, also reported a higher level of minority stress, perceived burdensomeness, and thwarted belongingness.

Indirect Models Predicting Depressive Symptoms from Minority Stress Via Perceived Burdensomeness and Thwarted Belongingness

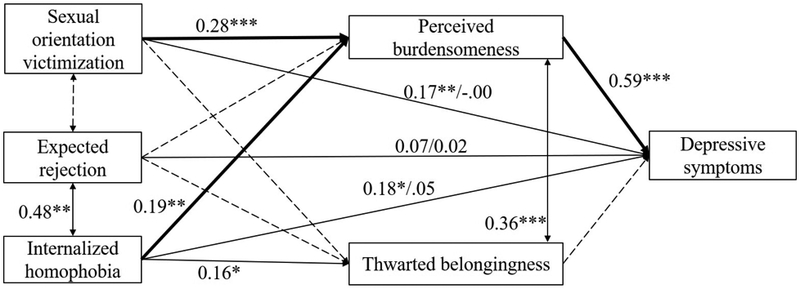

Figure 2 presents the indirect relations between minority stress depressive symptoms through perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness and Table 2 provides the results from the path models, including 1) the direct associations between minority stressors and depressive symptoms, 2) indirect associations between minority stressors and depressive symptoms, through perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness, and 3) whether the indirect relations were moderated by problem-solving coping skills.

Figure 2.

Predicting depressive symptoms from minority stress via perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness. Direct significant (p < .05) relations are presented in narrow arrows (with the values before the dash representing the coefficients of the direct relations, and after the dash the direct relations including perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness (as mediators). Significant bootstrapped indirect relations are presented in bold arrows. Non-significant direct relations are presented in striped arrows. Standardized regression coefficients are given with significance level. * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001

Table 2.

Results from Regression Models of Minority Stress and Depressive Symptoms Through Perceived Burdensomeness and Thwarted Belongingness, Moderated by Problem-Solving Coping Skills

| Predictor | B | SE | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct relation with depressive symptoms | |||

| Sexual orientation victimization | .39 | .15 | .008 |

| Expected rejection | .05 | .06 | .400 |

| Internalized homophobia | .19 | .08 | .010 |

| Predictor | Estimate | 95% BCI | |

| Indirect relation through perceived burdensomeness | |||

| Sexual orientation victimization | .37 | .22, .57 | |

| Expected rejection | .03 | −.04, .10 | |

| Internalized homophobia | .13 | .05, .22 | |

| Indirect relation through thwarted belongingness | |||

| Sexual orientation victimization | .01 | −.00, .07 | |

| Expected rejection | .01 | −.00, .04 | |

| Internalized homophobia | .01 | −.00, .05 | |

| Moderated indirect relation through perceived burdensomeness | |||

| Sexual orientation victimization | −.03 | −.22, .16 | |

| Expected rejection | .06 | −.13, .26 | |

| Internalized homophobia | −.10 | −.20, .01 | |

| Moderated indirect relation through thwarted belongingness | |||

| Sexual orientation victimization | −.02 | −.20, −.03 | |

| Expected rejection | .01 | −.02, .04 | |

| Internalized homophobia | .01 | −.04, .01 | |

Note. Prior to the moderated mediation analyses, all continuous variables were centered. BCI = Bootstrapped Confidence Interval.

Results indicated direct associations between sexual orientation victimization and internalized homophobia with depressive symptoms. No significant association between expected rejection and depressive symptoms was found. Indirect effects for the association between sexual orientation victimization and depressive symptoms revealed that sexual orientation victimization relates to a higher level of perceived burdensomeness (B = 1.08, SE = 0.24, p < .001) and perceived burdensomeness relates to a higher level of depressive symptoms (B = .35, SE = .05, p < .001). The direct association between sexual orientation victimization and depressive symptoms is no longer statistically significant (from B = .39, SE = .15, p = .008 to B = −.00, SE = .13, p = .989) when including the indirect relationship with perceived burdensomeness (estimate = .37, 95%BCI [.22, .57]). There is no significant indirect relationship between sexual orientation victimization and depressive symptoms through thwarted belongingness (estimate = .01, 95%BCI [−.00, .07]).

Indirect effects for the association between internalized homophobia and depressive symptoms reveal that internalized homophobia relates to a higher level of perceived burdensomeness (B = .37, SE = .14, p = .008) and perceived burdensomeness relates to a higher level of depressive symptoms (B = .35, SE = .05, p < .001). The direct association between internalized homophobia and depressive symptoms is no longer statistically significant (from B = .19, SE = .08, p = .010 to B = .05, SE = .06, p = .391) when including the indirect relationship through perceived burdensomeness (estimate = .13, 95%BCI [.05, .22]). There is no significant indirect relation through thwarted belongingness (estimate = .01, 95%BCI [−.00, .05]).

There is no significant direct association between expected rejection and depressive symptoms (B = .05, SE = .06, p = .400) and there is no significant indirect relationship between expected rejection and depressive symptoms through perceived burdensomeness or thwarted belongingness (estimate = .03, 95%BCI [−.04, .10]; estimate = .01, 95%BCI[−.00, .04]). This model explained 13.8% of the variance in depressive symptoms.

Moderation by Problem-Solving Coping Skills

To test whether problem-solving coping skills moderated the indirect relationships between minority stress and depressive symptoms through perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness, moderated indirect relationships were estimated for each mediator (perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness), and each minority stress aspect separately (see Table 2). The results show that the indirect relationships between sexual orientation victimization, expected rejection, and internalized homophobia with depressive symptoms, through perceived burdensomeness, were not significantly moderated by problem-solving coping skills. Similarly, the indirect relationships between sexual orientation victimization, expected rejection, and internalized homophobia with depressive symptoms, through thwarted belongingness, were not significantly moderated by problem-solving coping skills.

Discussion

With the current study the minority stress model (Meyer, 2003) and interpersonal-psychological theory (Joiner et al., 2009) were combined in (1) studying the indirect relationships between three indicators of minority stress and depressive symptoms, through thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness, and (2) examining whether these indirect associations were dependent on level of problem-solving coping skills.

As hypothesized, the results show that the experience of both sexual orientation victimization and internalized homophobia was indirectly related to depressive symptoms through perceived burdensomeness, but not through thwarted belongingness. These findings are consistent with literature on minority stress (e.g., Meyer, 2003) and the interpersonal-psychological theory (Joiner et al., 2009), and extend findings from a previous study that showed an indirect relationship between sexual orientation victimization and LGB coming-out stress and depression and suicidal ideation, through perceived burdensomeness among youth in the United States (Baams et al., 2015). The current study shows that although minority stress and depressive symptoms are associated with thwarted belongingness, thwarted belongingness did not significantly explain the link between minority stress and depressive symptoms. The latter suggests that perceived burdensomeness is the key mechanism and should be the focus of future research.

Adding to previous work on the interpersonal-psychological theory model among sexual minority youth (Baams et al., 2015; Hill & Pettit, 2012; Van Orden et al., 2008), the current study shows that internalized homophobia (similar to sexual orientation victimization) was associated with depressive symptoms, through perceived burdensomeness, but that this was not the case for the expectation of rejection. It is currently unclear what mechanisms may explain how the expectation of rejection, or vigilance, is related to depressive symptoms and future research should focus on the association of expected rejection with other aspects of mental health, such as anxiety (Bettis et al., 2016).

In contrast to our hypotheses, indirect associations between minority stress and depressive symptoms were not dependent on level of problem-solving coping skills. From previous research we expected that adequate problem-solving coping skills would enable youth to regulate stressful responses and reduce negative feelings related to the minority stress, indicated by a weaker relationship between minority stress and depressive symptoms (Allport, 1954; Clarke, 2006; Gonzales et al., 2011; Silk et al., 2003). There are at least two possible explanations for this unexpected finding. First, although problem-solving coping skills have been found to ameliorate the associations between stress and health outcomes in previous research (e.g., Clarke, 2006; Penley et al., 2002), coping skills may not take the form that is necessary to ameliorate the associations between minority stress and health outcomes. Minority stress, as assessed in the current study, is characterized by overt sexual orientation victimization and internal processes of expected rejection and internalized homophobia. These three stressors have one thing in common: They involve issues that may be perceived as uncontrollable or unchangeable, especially when they are perpetrated by others. The meta-analysis by Penley and colleagues (2002) shows that problem-solving coping skills in the context of uncontrollable stressors (versus controllable) may not be sufficient to overcome their impact (Penley et al.). Therefore, to overcome minority stress perceived as uncontrollable or unchangeable different copings skills may be necessary, such as emotion-focused coping (Vitaliano, DeWolfe, Maiuro, Russo, & Katon, 1990).

Second, in addition to requiring different coping skills, the efficacy of coping should also be considered. Aldwin and Revinson (1987) describe the difference between effectiveness (i.e., the relation between coping and outcome) and efficacy (i.e., the perception that coping was successful in its achieving its goal) of coping and emphasize that one needs both to adequately handle stressful situations. Due to the perceived uncontrollable nature of minority stress, youth’s efficacy of coping may have been particularly low which would further undermine their efforts to adequately regulate stress. In the current study we did not obtain an assessment of efficacy of coping; we also did not assess which coping skills were used in different minority stress situations. Therefore, for future research it would be essential to assess the protective function of coping in different stressful situations, and assess perceived efficacy of coping as well as different forms of coping.

Although previous research shows sex differences in the associations between minority stress and depressive symptoms (Baams et al., 2015), we only found one sex difference: Boys reported higher levels of same-sex attraction than girls. This finding is in line with other studies suggesting more fluidity in girls’ sexual orientation and a higher likelihood to identify as bisexual for girls than for boys (e.g., Diamond, 2008; Kann, Olsen, McManus et al., 2016).

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

There were several limitations in the current study. The main limitations pertain to the cross-sectional nature of the current study and the inclusion of a non-representative and fairly homogeneous sample of youth who were contacted through their involvement in online communities.

First, with the current cross-sectional correlational data we cannot draw any causal inferences (Maxwell, Cole, & Mitchell, 2011). Concepts such as perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness may develop parallel to the development of depressive symptoms, and with the current study we cannot infer the temporal order of these developments. Moreover, in the current study we did not assess acquired capability for suicide—part of the interpersonal-psychological theory. This construct is often operationalized as a last step to developing suicidal behavior, and because our study focused on depressive symptoms, we did not include this measure in the study. Further, with the inclusion of a non-representative sample of which the majority was female (71.2%), we cannot generalize the findings to the LGBTQ population in the Netherlands.

Second, the current study included only self-report measures, of which the scale for sexual orientation victimization and problem-solving coping skills had low internal reliability. Other measures of the constructs in the current study could be obtained through (clinical) interviews, observations, or with peer-report measures, which would provide novel insights. Further, having more knowledge about who perpetrates sexual orientation victimization (e.g., known versus stranger, peer versus parent) may give us insights into when and how these negative experiences take place. Also, having measures of different types of problem-solving coping skills, such as cognitive restructuring or emotion-focused coping would allow us to compare the function of different coping strategies.

Third, the majority of the sample reported a Dutch cultural background. Most scholars emphasize the importance of considering intersectionality of gender (identity and expression), sexual identity, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status as important in health disparities (Mustanski, 2015; Mustanski, Kuper, & Greene, 2014). Research or methodologies that consider social inequality across several of these dimensions would expand our knowledge of inequalities among sexual minority youth, and in comparison to non-sexual minority youth (Mustanski, 2015).

Theoretical and Practical Implications

The current study suggests that the perception of being a burden to others is harmful for sexual minority youth—it is also an important factor for understanding health disparities. Although perceived burdensomeness was known to be an important factor in the development of suicidal ideation (Joiner et al., 2009), this concept has only recently received attention in research on sexual minority individuals (Baams et al., 2015; Hill & Pettit, 2012; Plöderl et al., 2014; Silva, Chu, Monahan, & Joiner, 2014; Woodward, Wingate, Gray, Pantalone, 2014). One suggested method to lower feelings of burdensomeness is through clinical intervention (Joiner et al., 2009; Woodward et al., 2014). Further, because perceived burdensomeness is found to be an important mediator in pathways to suicidality (Baams et al., 2015; Hill & Pettit, 2014), preventive efforts aimed at reducing perceived burdensomeness may also effectively prevent the development of depression and suicidality (Hill & Pettit, 2014). Despite the hypothesized state-like nature of perceived burdensomeness and the instability of these cognitions within individuals (Hill & Pettit, 2014; Joiner, 2005), there are currently no intervention or prevention studies that inform us on how to decrease perceived burdensomeness.

Further, existing research has largely focused on the negative impact of social isolation on sexual minority youth’s well-being. While this focus offers knowledge on the prevalence of social isolation, it also limits our insight into the development of mental health problems and potential protective factors. The current study supports previous findings that it is the perception of being a burden to others that is most harmful to sexual minority youth. Future (intervention) research should thus focus on the reduction of perceived burdensomeness, especially among sexual minority youth who appear to have a higher risk of developing these detrimental cognitions which ultimately compromise their mental health.

Although previous research has found that having adequate coping skills ameliorates the association of stress with health outcomes (e.g., Clarke, 2006; Penley et al., 2002), the current study did not find that the associations between minority stress and depressive symptoms were dependent on problem-solving coping skills. Unfortunately, research in the context of minority stress or among sexually stigmatized populations has rarely applied hypotheses following from coping theory (Lazarus, 1993; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) or examined the role of other individual-level factors. This may perhaps be in part because a focus on individual’s resilience could be confused with placing the responsibility to cope with minority stress on the individual (Kitzinger, 1997). We agree that an individualistic focus “could lead to ignoring the need for important political and structural changes” (Meyer, 2003, p. 692). However, a perspective in which coping processes can be viewed as protective allows for the identification of characteristics that can make individuals more resilient (Meyer, 2003; Mustanski, 2015), along with strategies to help youth build these skills. Thus, a fruitful path for prevention and intervention research in sexual minority youth mental health may be to consider the effectiveness and perceived efficacy of several forms of coping (i.e., active versus passive coping, emotional versus problem-solving coping skills) and their function in buffering the impact of uncontrollable minority stressors. These efforts may aid in designing programs or clinical practices that promote the use of coping skills, especially focusing on strategies to cope with perceptions of stigma and discrimination.

Conclusions

Although longitudinal research is necessary to identify developmental trajectories of minority stress and mental health, the current study provides compelling knowledge on the important role of perceived burdensomeness in the relationship between minority stress and depressive symptoms. The current study advances our understanding of the mechanisms at play in the dynamics of sexual minority youth’s minority stress and mental health. Knowledge of the role of additional dimensions of minority stress, as well as potential protective factors, will lead to effective (preventive) interventions to help youth be more resilient to minority stress.

Acknowledgements:

This study was funded by Dynamics of Youth (DoY). DoY is one of the four strategic themes of Utrecht University in the Netherlands, in which all seven faculties participate. DoY supports and funds multidisciplinary research projects to investigate the biological and social-cultural factors that influence the development of children (www.uu.nl/dynamicsofyouth). This manuscript reflects the views of the authors and may not reflect the opinions or views of DoY. This research was also supported by grant 5 R24 HD042849, awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The authors acknowledge generous support from the Communities for Just Schools Fund, and support for Russell from the Priscilla Pond Flawn Endowment at the University of Texas at Austin.

Contributor Information

Dr. Laura Baams, University of Groningen, Pedagogy and Educational Sciences, Grote Rozenstraat 38, 9712 TJ Groningen, the Netherlands; University of Texas at Austin, Population Research Center, Human Development and Family Sciences

Prof. dr. Judith Semon Dubas, Utrecht University, Developmental Psychology

Prof. dr. Stephen T. Russell, University of Texas at Austin, Human Development and Family Sciences

Prof. dr. Rosemarie L. Buikema, Utrecht University, Gender Studies

Prof. dr. Marcel A. G. van Aken, Utrecht University, Developmental Psychology

References

- Ager A, & Maclachlan M (1998). Psychometric properties of the Coping Strategy Indicator (CSI) in a study of coping behaviour amongst Malawian students. Psychology and Health, 13, 399–409. doi: 10.1080/08870449808407299 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aldwin CM, & Revenson TA (1987). Does coping help? A reexamination of the relation between coping and mental health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 337–348. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.53.2.337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allport GW (1954). The nature of prejudice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Amirkhan JH (1990). A factor analytically derived measure of coping: The Coping Strategy Indicator. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 1066–1074. Retrieved from: http://psycnet.apa.org/buy/1991-11477-001 [Google Scholar]

- Baams L, Bos HM, & Jonas KJ (2014). How a romantic relationship can protect same-sex attracted youth and young adults from the impact of expected rejection. Journal of Adolescence, 37, 1293–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baams L, Russell ST, & Grossman AH (2015). Minority stress and mechanisms of risk for depression and suicidal ideation among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Developmental Psychology, 51, 688–696. doi: 10.1037/a0038994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Rothblum ED, & Beauchaine TP (2005). Victimization over the life span: a comparison of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual siblings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 477–487. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettis AH, Forehand R, McKee L, Dunbar JP, Watson KH, & Compas BE (2016). Testing specificity: Associations of stress and coping with symptoms of anxiety and depression in youth. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25, 949–958. doi: 10.1007/s10826-015-0270-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijttebier P, & Vertommen H (1997). Psychometric properties of the Coping Strategy Indicator in a Flemish sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 23, 157–160. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(97)00012-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bos HM, Van Balen F, Van Den Boom DC, & Sandfort TG (2004). Minority stress, experience of parenthood and child adjustment in lesbian families. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 22, 291–304. doi: 10.1080/02646830412331298350 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burton CM, Marshal MP, Chisolm DJ, Sucato GS, & Friedman MS (2013). Sexual minority-related victimization as a mediator of mental health disparities in sexual minority youth: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42, 394–402. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9901-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Jaser SS, Bettis AH, Watson KH, Gruhn MA, Dunbar JP, ... & Thigpen JC (2017). Coping, emotion regulation, and psychopathology in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 143, 939–991. doi: 10.1037/bul0000110.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Connor-Smith JK, Saltzman H, Thomsen AH, & Wadsworth ME (2001). Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 87–127. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.127.1.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke AT (2006). Coping with interpersonal stress and psychosocial health among children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35, 10–23. doi: 10.1007/s10964-005-9001-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR (2002). Mental health problems among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths ages 14 to 21. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 7, 439–462. doi: 10.1177/1359104502007003010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Grossman AH, & Starks MT (2006). Childhood gender atypicality, victimization, and PTSD among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 21, 1462–1482. doi: 10.1177/0886260506293482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dékovic M (1996). Vragenlijst Depressie bij Adolescenten (VDA). University Utrecht, The Netherlands: Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Dekovic M (1999). Parent-adolescent conflict: Possible determinants and consequences. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 23, 977–1000. doi: 10.1080/016502599383630 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond L (2008). Sexual fluidity: Understanding women’s love and desire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RM, Ayala G, Bein E, Henne J, & Marin BV (2001). The impact of homophobia, poverty and racism on the mental health of gay and bisexual Latino men: Findings from 3 US cities. American Journal of Public Health, 91, 927–932. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9905-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doornwaard SM, van den Eijnden RJ, Baams L, Vanwesenbeeck I, & ter Bogt TF (2016). Lower psychological well-being and excessive sexual interest predict symptoms of compulsive use of sexually explicit Internet material among adolescent boys. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45, 73–84. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0326-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragowski EA, Halkitis PN, Grossman AH, & D’Augelli AR (2011). Sexual orientation victimization and posttraumatic stress symptoms among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 23, 226–249. 10.1080/10538720.2010.541028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Tein JY, Sandler IN, & Friedman RJ (2001). On the limits of coping interaction between stress and coping for inner-city adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 16, 372–395. doi: 10.1177/0743558401164005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Nolen-Hoeksema S, & Dovidio J (2009). How does stigma “get under the skin”? The mediating role of emotion regulation. Psychological Science, 20, 1282–1289. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02441.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2014.962683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill RM, & Pettit JW (2012). Suicidal ideation and sexual orientation in college students: the roles of perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and perceived rejection due to sexual orientation. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 42, 567–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.00113.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill RM, & Pettit JW (2014). Perceived burdensomeness and suicide‐related behaviors in clinical samples: Current evidence and future directions. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70, 631–643. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton AN, & Szymanski DM (2011). Family dynamics and changes in sibling of origin relationship after lesbian and gay sexual orientation disclosure. Contemporary Family Therapy, 33, 291–309. doi: 10.1007/s10591-011-9157-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE Jr (2005). Why people die by suicide. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE Jr, Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Selby EA, Ribeiro JD, Lewis R, et al. (2009). Main predictions of the interpersonal–psychological theory of suicidal behavior: Empirical tests in two samples of young adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118, 634–646. doi: 10.1037/a0016500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, & Davies M (1982). Epidemiology of depressive mood in adolescents: An empirical study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 39, 1205–1212. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290100065011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, Olsen EO, McManus T, et al. (2016). Sexual identity, sex of sexual contacts, and health-related behaviors among students in grades 9–12—United States and selected sites. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 65, 1–202. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/ss/ss6509a1.htm [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher C (2009). Minority stress and health: Implications for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (LGBTQ) young people. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 22, 373–379. doi: 10.1080/09515070903334995 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzinger C (1997). Lesbian and gay psychology: A critical analysis In Fox D & Prilleltensky I (Eds.), Critical psychology: An introduction (pp. 202–216). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS (1993). Coping theory and research: Past, present, and future. Psychosomatic Medicine, 55, 234–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, & Folkman S (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Malooly AM, Flannery KM, & Ohannessian CM (2017). Coping mediates the association between gender and depressive symptomatology in adolescence. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 41, 185–197. doi: 10.1177/0165025415616202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martos AJ, Nezhad S, & Meyer IH (2015). Variations in sexual identity milestones among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 12, 24–33. doi:10.1007%2Fs13178-014-0167-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell SE, Cole DA, & Mitchell MA (2011). Bias in crosssectional analyses of longitudinal mediation: Partial and complete mediation under an autoregressive model. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 46, 816–841. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2011.606716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, & Dean L (1998). Internalized homophobia, intimacy and sexual behaviour among gay and bisexual men In Herek G (Ed.), Stigma and sexual orientation (pp. 160–186). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK and Muthén BO (1998–2012). Mplus User’s Guide. Seventh Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B (2015). Future directions in research on sexual minority adolescent mental, behavioral, and sexual health. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 44, 204–219. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.982756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Kuper L, & Greene GJ ( 2014. ). Development of sexual orientation and identity In Tolman DL & Diamond LM (Eds.), Handbook of sexuality and psychology (pp. 597 – 628 ). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb ME, & Mustanski B (2010). Internalized homophobia and internalizing mental health problems: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 1019–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noom MJ, Deković M, & Meeus WH (1999). Autonomy, attachment and psychosocial adjustment during adolescence: a double-edged sword? Journal of Adolescence, 22, 771–783. doi: 10.1006/jado.1999.0269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald RF (1999). Family and friendship relationships after young women come out as bisexual or lesbian. Journal of Homosexuality, 38, 65–83. doi: 10.1300/J082v38n03_04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penley JA, Tomaka J, & Wiebe JS (2002). The association of coping to physical and psychological health outcomes: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 25, 551–603. doi: 10.1023/A:1020641400589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilkington NW, & D’Augelli AR (1995). Victimization of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth in community settings. Journal of Community Psychology, 23, 33–56. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8192119 [Google Scholar]

- Plöderl M, Sellmeier M, Fartacek C, Pichler EM, Fartacek R, & Kralovec K (2014). Explaining the suicide risk of sexual minority individuals by contrasting the minority stress model with suicide models. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43, 1559–1570. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0268-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, & Fish JN (2016). Mental health in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 12, 465–487. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandfort TGM (1997). Samen of Apart. Wat homoseksuele mannen en lesbische vrouwen beweegt [Together or separate. Aspects that affect gay men and lesbian women]. Utrecht, The Netherlands: Utrecht University, Department of Gay and Lesbian Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Seiffge-Krenke I, & Klessinger N (2000). Long-term effects of avoidant coping on adolescents’ depressive symptoms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29, 617–630. doi: 10.1023/A:1026440304695 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silk JS, Steinberg L, & Morris AS (2003). Adolescents’ emotion regulation in daily life: Links to depressive symptoms and problem behavior. Child Development, 74, 1869–1880. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00643.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva C, Chu C, Monahan KR, & Joiner TE (2014). Suicide risk among sexual minority college students: A mediated moderation model of sex and perceived burdensomeness. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2, 22–33. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000086 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Talley AE, & Bettencourt B (2011). The moderator roles of coping style and identity disclosure in the relationship between perceived sexual stigma and psychological distress. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 41, 2883–2903. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2011.00863.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Beusekom G, Baams L, Bos HM, Overbeek G, & Sandfort TG (2016). Gender nonconformity, homophobic peer victimization, and mental health: How same-sex attraction and biological sex matter. The Journal of Sex Research, 53, 98–108. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2014.993462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Cukrowicz KC, Witte TK, & Joiner TE Jr (2012). Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness: construct validity and psychometric properties of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment, 24, 197–215. doi: 10.1037/a0025358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Gordon KH, Bender TW, & Joiner TE Jr (2008). Suicidal desire and the capability for suicide: tests of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior among adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 72–83. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaliano PP, DeWolfe DJ, Maiuro RD, Russo J, & Katon W (1990). Appraised changeability of a stressor as a modifier of the relationship between coping and depression: A test of the hypothesis of fit. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 582–592. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.59.3.582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward EN, Wingate L, Gray TW, & Pantalone DW (2014). Evaluating thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness as predictors of suicidal ideation in sexual minority adults. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1, 234–243. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000046 [DOI] [Google Scholar]