Abstract

LEE-negative Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) strains are important cause of infection in humans and they should be included in the public health surveillance systems. Some isolates have been associated with haemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) but the mechanisms of pathogenicity are is a field continuos broadening of knowledge. The IrgA homologue adhesin (Iha), encoded by iha, is an adherence-conferring protein and also a siderophore receptor distributed among LEE-negative STEC strains. This study reports the presence of different subtypes of iha in LEE-negative STEC strains. We used genomic analyses to design PCR assays for detecting each of the different iha subtypes and also, all the subtypes simultaneously. LEE-negative STEC strains were designed and different localizations of this gene in STEC subgroups were examinated.

Genomic analysis detected iha in a high percentage of LEE-negative STEC strains. These strains generally carried iha sequences similar to those harbored by the Locus of Adhesion and Autoaggregation (LAA) or by the plasmid pO113. Besides, almost half of the strains carried both subtypes. Similar results were observed by PCR, detecting iha LAA in 87% of the strains (117/135) and iha pO113 in 32% of strains (43/135). Thus, we designed PCR assays that allow rapid detection of iha subtypes harbored by LEE-negative strains. These results highlight the need to investigate the individual and orchestrated role of virulence genes that determine the STEC capacity of causing serious disease, which would allow for identification of target candidates to develop therapies against HUS.

Keywords: Microbiology, Food technology, Food microbiology, Animal behavior, Public health, Infectious disease, STEC iha subtype genomics PCR design

Microbiology; Food technology; Food microbiology; Animal behavior; Public health; Infectious disease; STEC iha subtype genomics PCR design

1. Introduction

Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) is an important group of pathogens which cause serious human disease, including bloody diarrhea and haemolytic uraemic syndrome (HUS) [18, 23].

STEC are classified into two major groups in accordance with the presence of the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE). LEE-positive strains have the ability to produce attaching and effacing lesions on the intestinal epithelium [23]. However, the presence of LEE is not essential for pathogenesis of all the STEC strains since some LEE-negative STEC strains have been also associated with severe disease in humans [4]. The majority of STEC strains associated with disease in humans adhere to the intestinal epithelial cells [12] because the adhesion presumably allows the pathogens to deliver toxins efficiently to the host [33]. This colonization ability is often linked to the expression of specific mechanisms. However, little is known about the adherence mechanisms of LEE-negative STEC strains to epithelial cells [36].

Among STEC, a range of novel adhesins have been identified, including Iha. It was first described as an adhesin in a STEC O157:H7 strain, and it was named “IrgA homologue adhesin” due to homology shared with the IrgA of Vibrio cholerae [33]. The iha gene was found in duplicated genomic islands (called OI-43 and OI-48), which encode Tellurite resistance (Ter), AidaA-1, and Iha [37].

Interestingly, iha has been detected in LEE-positive STEC and LEE-negative STEC, as well as in uropathogenic E. coli [14, 30, 33]. Moreover, LEE-negative STEC strains, iha is harbored by mobile genetic elements that encode other virulence factors involved in human pathogenicity, namely plasmids and pathogenicity islands (PAIs). For example, plasmid pO113 encodes several toxins and adhesins such as EhxA, Saa, SubAB, and Iha [15, 24]. The PAI Locus of Proteolysis Activity (LPA) encodes EspI and Iha [30]. A novel PAI, named Locus of Adhesion and Autoaggregation (LAA) is found either as a “complete” structure with four modules: module I (hes and other genes), module II (iha, lesP and others genes), module III (pagC, tpsA, and other genes), and module IV (agn43 and other genes); or as an “incomplete” structure if one of the modules is missing (<4 modules) [17].

Although some studies have found and evaluated the presence of the different iha subtypes, this information in LEE-negative STEC strains is scarce. Therefore, our objetives are to design PCR assays for detecting each of the different subtypes of iha in LEE-negative STEC strains and to examine the different localizations of this gene in STEC subgroups. Even more, and stemming from these objetives, we aimed at designing a general PCR assay for detecting all subtypes of iha in LEE-negative STEC strains.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Genomic analysis

Thirty LEE-negative STEC strains were selected for the sequence analysis. Fourteen strains were isolated from dairy, beef cattle and food in Argentina [21, 29] and 16 strains from cattle and humans in Chile [16]. Draft genomes of all of these strains were previously obtained [16]. The accession number of the corresponding sequences are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Strains ID and accession numbers (NCBI nucleotide) for draft genomic sequences included in this study.

| Strain ID | Serogroup/Serotype | Origin | Country | Year of isolation | Accession Number | In silico iha subtype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CM 15-2 | O8:H16 | Ground beef | Argentina | 1998 | QESP00000000 | iha pO113 |

| 30M | O8:H19 | Ground beef | Argentina | 1998 | QESO00000000 | - |

| 45-2-4 | O8:H19 | Cattle | Argentina | 2009 | QESN00000000 | - |

| HT 1-6 | O20:H19 | Hamburguer | Argentina | 1998 | QESL00000000 | iha LAA/iha pO113 |

| HW 1-3 | O22:H8 | Hamburguer | Argentina | 1998 | QESK00000000 | iha LAA/ iha pO113 |

| AM 162-1 | O39:H49 | Cattle | Argentina | 1998 | QESJ00000000 | iha LAA/ iha pO113 |

| V07-4-4 | O91:H21 | Cattle | Argentina | 2008 | QESH00000000 | iha LAA/ iha pO113 |

| AP 16-1 | O91:H21 | Cattle | Argentina | 1998 | QESG00000000 | iha LAA/ iha pO113 |

| 47-1-1 | O91:H21 | Cattle | Argentina | 2009 | QESF00000000 | iha LAA/ iha pO113 |

| FO 130 | O91:H21 | Cattle | Argentina | 2001 | QESE00000000 | iha LAA/iha pO113 |

| 5-1-1 | O91:H21 | Cattle | Argentina | 2010 | QESD00000000 | iha LAA/ iha pO113 |

| AP 32-1 | O117:H7 | Cattle | Argentina | 1998 | QERR00000000 | iha LAA |

| AP 31-1 | O141:H8 | Cattle | Argentina | 1998 | QERO00000000 | iha LAA/ iha pO113 |

| 180-3-4r | O178:H19 | Chicken burguer | Argentina | 2007 | QERJ00000000 | iha LAA |

| 26_1 | O2 | Cattle | Chile | NA | QESR00000000 | iha EDL933 |

| 365_1 | O7 | Cattle | Chile | NA | QESQ00000000 | iha LAA/ iha pO113 |

| 116_1 | O20:H19 | Cattle | Chile | NA | QESM00000000 | iha LAA/ iha pO113 |

| 348_3 | O46 | Cattle | Chile | NA | QESI00000000 | iha LAA/ iha pO113 |

| 211_1 | O103:H42 | Cattle | Chile | NA | QESC00000000 | iha LAA/ iha pO113 |

| E044-00 | O113:H21 | Human | Chile | 2000 | QERZ00000000 | iha LAA |

| E045-00 | O113:H21 | Human | Chile | 2000 | QERY00000000 | iha LAA |

| E042-00 | O113:H21 | Human | Chile | 2000 | QERU00000000 | iha LAA |

| E043-00 | O113:H21 | Human | Chile | 2000 | QERT00000000 | iha LAA |

| E046-00 | O113:H21 | Human | Chile | 2000 | QERS00000000 | iha LAA |

| 6_6 | O130:H11 | Cattle | Chile | NA | QERQ00000000 | iha pO113 |

| 208_3 | O139:H19 | Cattle | Chile | NA | QERP00000000 | iha pO113 |

| 175_1 | O156:H- | Cattle | Chile | NA | QERN00000000 | iha LAA |

| 218_8 | O163:H9 | Cattle | Chile | NA | QERM00000000 | iha LAA/ iha pO113 |

| 115_4 | O171:H2 | Cattle | Chile | NA | QERL00000000 | iha LAA |

| 58_3 | O174:H21 | Cattle | Chile | NA | QERK00000000 | iha LAA |

2.2. In silico identification of iha subtypes

The presence/absence of iha genes and their localization were determined by using VirulenceFinder and BLAST programs [2, 10]. Open reading frames (ORFs) were detected by using the ORFfinder program [28]. The identified nucleotide sequences of iha were downloaded from the GenBank. A multiple alignment and phylogenetic relathionship of nucleotide sequences of iha were performed by using MUSCLE in the Ugene software, thus generating a maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree [20].

Genomes of STEC strains were annotated by using RAST (Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology) server [3] and, when possible, the regions near the iha gene were manually analyzed.

2.3. Polymerase chain reaction PCR detection of iha genes

Primers were designed to amplify iha (iha without discrimination of any subtype) and also specific iha subtypes (named iha pO113 and iha LAA). DNA was extracted by following methodologies previously described by Parma et al. [22]. Amplification was performed in a total volume of 25 μl. The reaction mixture contained 500 mM KCl, 100 mM Tris–HCl pH 9, Triton X-100, 25 mM MgCl2, 200 mM of each deoxynucleotide (dATP, dGTP, dCTP, dTTP), 1U TaqDNA Polymerase and 2.5 ul DNA. Primers and PCR conditions are described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Primers used for iha detection and size of PCR amplicons.

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′) | Size (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| pO113 iha F | GGCACTGAGATCAGTGGAGG | 600 | This study |

| pO113 iha R | ACCAGAGCATATCTTGTTCCG | ||

| iha general F | AACTGGCAGATCACCGAAGA | 346 | This study |

| iha general R | GCGACATCCAGTAATTTCGCT | ||

| LAA iha F | TTTCAGCCAGCAGCATGGCA | 172 | [7] |

| LAA iha R | ACATCCACACCCTCCACAGC |

A total of 135 LEE-negative STEC strains were screened. These STEC strains were isolated from dairy and beef cattle and food (beef, ground beef, hamburguer and chicken burger) between 2000 and 2015 from Argentina. In previous studies, these isolates were analyzed for the presence of vt1, vt2, eae, ehxA, and saa genes by PCR, and O and H types were determined by the microagglutination technique (Table 3) [1,8,21,22]. Twenty eight sequenced LEE-negative STEC strains, whose genomes were previously sequenced [16], harboring different iha subtypes were used as positive controls. In addition, other two sequenced LEE-negative and iha negative STEC strains (30M and CM15-2) and 69 LEE-positive STEC strains belonging to serotypes O26:H11, O157:H7, O111:H-, O145:H-, and O103:H-, were used as negative controls.

Table 3.

Distribution of iha genes, virulence profile and serogroup of LEE-negative STEC strains isolated from different origins.

| Serotype | iha pO113 | iha LAA | iha general | Virulence Profile | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O8:H16 (1) | + | - | + | vt1, saa | Ground beef |

| O8:H19 (2) | - | - | - | vt2 | Cattle |

| O20:H19 (1) | + | + | + | vt1, vt2, ehxA, saa | Hamburguer |

| O22:H8 (1) | - | + | + | vt1, vt2, ehxA, saa | Hamburguer |

| O39:H49 (1) | + | + | + | vt2, ehxA, saa | Cattle |

| O91:H21 (10) | + | + | + | vt2, saa, ehxA | Cattle |

| O91:H21 (4) | - | + | + | vt2, saa, ehxA | Cattle |

| O91:H21 (4) | + | + | + | vt2, ehxA | Cattle |

| O91:H21 (1) | - | + | + | vt2, ehxA | Cattle |

| O91:H21 (1) | - | + | + | vt1, ehxA | Cattle |

| O91:H40 (1) | - | + | + | vt2, ehxA | Chicken burger |

| O91:H28 (1) | - | + | + | vt2, saa, ehxA | Cattle |

| O91:H21 (1) | + | + | + | vt2 | Cattle |

| O103:H26 (1) | - | + | + | vt2 | Beef |

| O103:H42 (1) | - | + | + | vt2 | Beef |

| O113:H21 (10) | + | + | + | vt2, saa, ehxA | Cattle |

| O113:H21 (4) | - | + | + | vt2, saa, ehxA | Cattle |

| O113:H21 (2) | - | + | + | vt2, saa, ehxA | Chicken burger |

| O113:H21 (1) | + | + | + | vt1, vt2, ehxA, saa | Cattle |

| O117:H7 (1) | - | + | + | vt2, saa | Cattle |

| O130:H11 (23) | - | + | + | vt1, vt2, ehxA, saa | Cattle |

| O130:H11 (6) | + | + | + | vt1, vt2, ehxA, saa | Cattle |

| O130:H11 (2) | + | + | + | vt1, vt2, ehxA, saa | Chicken burger |

| O130:H11 (1) | + | + | + | vt1, ehxA, saa | Cattle |

| O141:H8 (1) | - | + | + | vt1, vt2, ehxA, saa | Cattle |

| O174:H21 (9) | - | - | - | vt2 | Cattle |

| O174:H21 (12) | - | + | + | vt2 | Cattle |

| O174:H21 (1) | - | + | + | vt1, vt2, ehxA, saa | Cattle |

| O174:H21 (1) | - | + | + | vt2, saa | Cattle |

| O178:H19 (6) | - | - | - | vt2 | Cattle |

| O178:H19 (1) | + | + | + | vt2, ehxA, saa | Cattle |

| O178:H19 (4) | + | + | + | vt1, vt2, ehxA,saa | Cattle |

| O178:H19 (13) | - | + | + | vt2 | Cattle |

| O178:H19 (1) | - | + | + | vt2, ehxA,saa | Cattle |

| O178:H19 (1) | - | + | + | vt1, vt2, ehxA,saa | Cattle |

| O178: H21 (2) | - | + | + | vt2 | Cattle |

| O178: H25 (1) | - | + | + | vt2, ehxA, saa | Cattle |

| O178:H28 (1) | - | + | + | vt2, ehxA, saa | Cattle |

2.4. Statistical analysis

The association between LEE-negative STEC strains and iha gene subtype was analyzed by using the Fisher's test with a confidence level of 95%.

3. Results

3.1. Genomic analysis

Genomes of thirty LEE-negative STEC strains isolated in Argentina (n = 14) and Chile (n = 16) were analyzed. The presence of one or two iha genes was detected in 28/30 (93%) of the STEC genomes by using VirulenceFinder tool and BLAST. The iha nucleotide sequences identified were similar to iha genes carried by STEC strain B2F1 (LAA pathogenicity island), 4797/97 (LPA pathogenicity island), 98NK2 (plasmid pO113) and EDL933 (accession numbers AFDQ01000026.1, AJ278144.1 and AF399919, AE005174, respectively). The comparative analysis showed that iha of LAA and iha of LPA are 99.7% similar. Therefore, in this study, we named the detected iha subtypes as iha LAA, iha pO113 and iha EDL933.

3.2. In silico identification of iha subtypes

Among the 28 STEC genomes positive for iha, 14 (47%) carried both iha LAA and iha pO113 subtypes, 12 (40%) iha LAA, 3 (10%) iha pO113, and 1 (3%) iha EDL933. In particular, 14 (70%) and 16 (80%) out of 20 STEC strains isolated from cattle were positive to iha LAA and iha pO113, respectively; and only one was positive for iha EDL933. Three (60%) out of 5 and 3 (60%) of STEC strains isolated from food were positive to iha LAA and iha pO113, respectively. All of the LEE-negative STEC obtained from humans were positive for the presence of iha LAA.

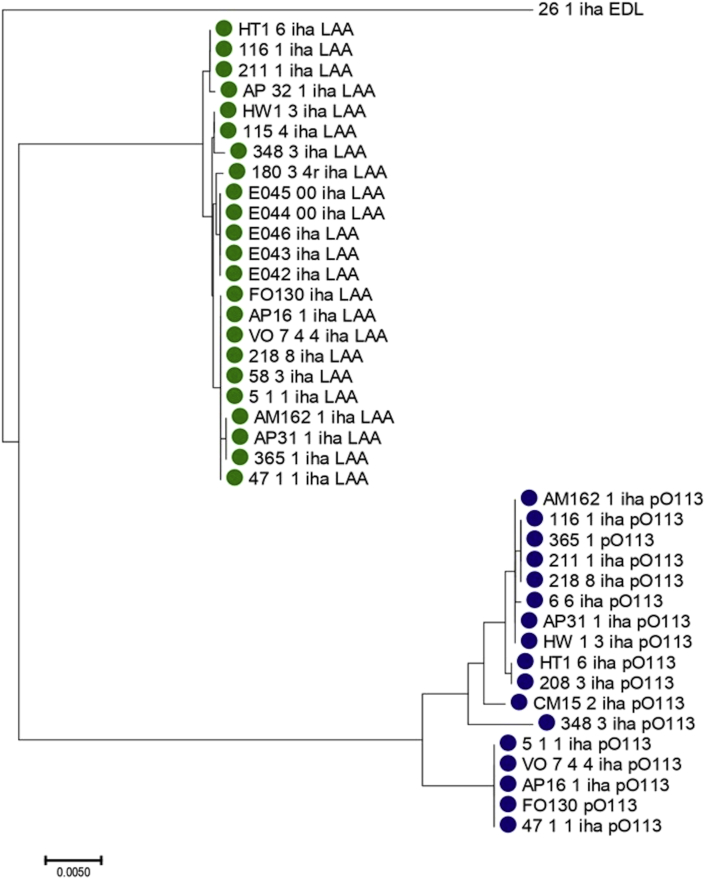

A phylogenetic tree based on iha sequences showed three clades, each one corresponding to the subtypes iha LAA, iha pO113, and iha EDL933, respectively (Figure 1). In clade iha pO113, sequences shared near 98% similarity. In clade iha LAA, the sequences shared near 99% sequence similarity and 94% similarity with clade iha pO113. We found that one iha EDL933 shared 91% similarity with clades iha pO113 and iha LAA.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree based on iha sequences.

Once the contigs carrying iha genes were selected, annotated regions near iha were examined when they were available. Thus, we identified three different genetic contexts for each iha subtype: first, genes encoding AtoS, AtoC, acetoacetyl-CoA transferases and a ShiA homologue were generally identified upstream iha gene, while genes encoding the vitamin B12 receptor BtuB, a N-acetylgalactosamine-sulfatase and a putative porin gene were detected downstream, in a LAA island context. Second, an entry exclusion protein coding gene was identified in the proximity of iha pO113. Additionally, replication initiation proteins (Rep) and other plasmid element-coding genes, as well as saa and/or subA genes, could be identified in several contigs carrying iha pO113. Finally, only one small contig carried iha EDL933 that had a region encoding tellurite resistance proteins, was observed.

3.3. Distribution of iha by PCR detection

Among the 135 LEE-negative STEC strains screened by PCR, 124 (92%) were positive for iha (iha general) (Table 3). Specific detection of iha LAA showed that this subtype was predominant among LEE-negative STEC strains (117/135, 87%) and detected in several serotypes. The iha pO113 subtype was detected in 32% of the strains (43/135). The iha LAA and iha pO113 subtypes were significantly associated with LEE-negative STEC strains (both with p > 0.00001).

4. Discussion

In recent years, there has been an increasing interest in the study and characterization of LEE-negative STEC strains because some isolates have been associated with HUS [32]. Iha is an adherence-conferring protein and also a siderophore receptor that is distributed among STEC strains of a variety of serotypes [34] and was reported in PAIs and plamids of LEE-negative STEC [17, 25].

In this study, genomic analysis and PCR assays detected iha subtypes in a high percentage of LEE-negative STEC strains. In other studies, such as Toma et al. [34] the most prevalent adhesin gene found among all LEE-negative and LEE-positive STEC strains was iha; 127 out of 139 strains (91%) from humans (54), animals (52), and food (33). Similarly, Miko et al. [15] found that iha was common in O178 LEE-negative STEC strains serogroup tested. According to Cáceres et al. [5] iha showed a high distribution in strains isolated from calves and adults (87.04 and 98.48%, respectively). On the other hand, a study on distribution of gene markers for OI-43/48 detected iha in 45% of LEE-positive STEC strains serogroup O103 [13]. However, we should be cautious about the interpretation of these results because only one subtype of iha was positively screened. Taking into account different iha subtypes are associated to LEE-positive or LEE-negative STEC strains, subtype-specific detection should be performed.

Interestingly, the genomic analysis allowed for the identification of particular characteristics of iha genes in 30 LEE-negative STEC strains. These strains generally carried iha sequences similar to those encoded by LAA or pO113, here named iha LAA and iha pO113 subtypes. Besides, almost half of the strains carried both subtypes simultaneously. Similar results were observed by PCR analyses that detected 87% of strains (117/135) from iha LAA and 32% of strains (43/135) from iha pO113.

Aligment and phylogenetic analysis revealed that iha LAA and iha pO113 subtypes were highly similar, whereas they have lower sequence similarity regarding iha gene in STEC EDL933. These results suggest that iha genes from LEE-negative and LEE-positive STEC strains may have different origins and are in agreement with those previously reported by Ju et al. [11], who reported that iha genes from LEE-positive STEC had high similarity (99.6%), whereas they had lower sequence similarity (91.1–93.6%) than iha genes from LEE-negative STEC. The scientific sustenance for the apparent differences in virulence between different serotypes is not known. Furthermore, evolution of PAIs and plasmids can occur by several processes, including recombination events, leading to deletion or acquisition of DNA, and horizontal transferance events that determine separate evolution and sequence divergence [31].

The DNA sequences upstream and downstream of the iha LAA subtype were highly similar among the positive strains and to the same regions in LAA of STEC B2F1, suggesting that this subtype is generally located in this pathogenicity island. On the other hand, elements and genes identified in contigs carrying iha pO113 indicate that this subtype is located in plasmids. Bacteria express numerous surface structures that enable them to interact with and survive in changing environments. In addition, iron uptake systems are vital to bacterial survival within the host but mucosal surfaces of the host cells are iron-poor environments [27]. Many bacteria secrete siderophores which bind iron and are brought into the bacterial cell via a specific siderophore receptor. The capacity of Iha to transport siderophores is TonB-dependent. The TonB protein, which is anchored in the cytoplasmic membrane, provides energy to the outer membrane receptors for the transport of iron compounds [14, 26, 35]. Interestingly, our study found that iha LAA is located in the proximity to btuB gene which encodes an outer membrane protein required for vitamin B12 uptake and is also TonB-dependent [6].

The virulence of STEC is dependent on its ability to multiply in host tissues [35]. Iha is common in all seropathotypes, suggesting that it is a necessary but not sufficient adhesin for human infection [34]. However, mutations of TonB-dependent iron transport systems have been assessed with several pathogens resulting in an avirulent phenotype in animal models [35]. Moreover, it has been reported that during iron shortage, siderophore synthesis and expression of siderophore transporters increase, thus eliciting an enhanced immune response against these antigens and may be used as the basis for development of a vaccine candidate for STEC control [9].

In conclusion, the capacity of LEE-negative STEC strains to cause life-threatening human disease has been long-recognized [19]. Our study showed that LEE-negative STEC strains frequently had one or two iha genes located in mobile elements that differed in sequence with the iha gene present in different localizations described previously. Further studies are needed that shed light on the actual role of Iha in STEC pathogenesis and find out how the combination of different genes determine STEC virulence leading to serious disease, a repertoire that could be the basis for developing therapies against HUS. In the meantime, we designed PCR assays that may contribute to the rapid detection of iha, based on common sequences among subtypes, and specific iha subtypes for future basic and/or epidemiological studies.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Colello R: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Krüger A: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Velez MV: Performed the experiments.

Del Canto F, Vidal R: Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Etcheverría AI: Performed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Padola NL: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Funding statement

This work was supported by PICT 2015–2666, CICPBA from Argentina and FONDECYT grants 1161161 and 11150966 from Chile.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Analía Gandur for correcting and editing the manuscript.

References

- 1.Alonso M., Lucchesi P.M.A., Rodríguez E.M., Parma A.E., Padola N.L. Enteropathogenic (EPEC) and Shigatoxigenic Escherichia coli (STEC) in broiler chickens and derived products at different retail stores. Food Control. 2012;23(2):351–355. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul S.F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E.W., Lipman D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215(3):403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aziz R.K., Bartels D., Best A.A., DeJongh M., Disz T., Edwards R.A., Formsma K., Gerdes S., Glass E.M., Kubal M. The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics. 2008;9(1):75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bielaszewska M., Stoewe F., Fruth A., Zhang W., Prager R., Brockmeyer J., Mellmann A., Karch H., Friedrich A.W. Shiga toxin, cytolethal distending toxin, and hemolysin repertoires in clinical Escherichia coli O91 isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009;47(7):2061–2066. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00201-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cáceres M.E., Etcheverría A.I., Fernández D., Rodríguez E.M., Padola N.L. Variation in the distribution of putative virulence and colonization factors in Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from different categories of cattle. Front.Cell.Infect. Microbiol. 2017;7 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cadieux N., Kadner R.J. Site-directed disulfide bonding reveals an interaction site between energy-coupling protein TonB and BtuB, the outer membrane cobalamin transporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1999;96(19):10673–10678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colello R., Vélez M.V., González J., Montero D.A., Bustamante A.V., Del Canto F., Etcheverría A.I., Vidal R., Padola N.L. First report of the distribution of Locus of Adhesion and Autoaggregation (LAA) pathogenicity island in LEE-negative Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolates from Argentina. Microb. Pathog. 2018;123:259–263. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernández D., Rodriguez E., Arroyo G., Padola N.L., Parma A.E. Seasonal variation of Shiga toxin-encoding genes (stx) and detection of E. coli O157 in dairy cattle from Argentina. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2009;106(4):1260–1267. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.04088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gelgie A.E. 2018. The Effect of tonB Deletion on the Expression of the Genes Encoding Shiga Toxin, TonB-dependent Receptors and Fimbriae in the 16001 Oedema Disease Strain of E. coli.http://hdl.handle.net/11343/219875 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joensen K.G., Scheutz F., Lund O., Hasman H., Kaas R.S., Nielsen E.M., Aarestrup F.M. Real-time whole-genome sequencing for routine typing, surveillance, and outbreak detection of verotoxigenic Escherichia coli. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014;52(5):1501–1510. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03617-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ju W., Shen J., Li Y., Toro M.A., Zhao S., Ayers S., Najjar M.B., Meng J. Non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in retail ground beef and pork in the Washington DC area. Food Microbiol. 2012;32(2):371–377. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2012.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaper J.B., Nataro J.P., Mobley H.L. Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004;2(2):123–140. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karama M., Johnson R.P., Holtslander R., Gyles C.L. Production of verotoxin and distribution of O islands 122 and 43/48 among verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli O103: H2 isolates from cattle and humans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;75(1):268–270. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01445-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Léveillé S., Caza M., Johnson J.R., Clabots C., Sabri M., Dozois C.M. Iha from an Escherichia coli urinary tract infection outbreak clonal group A strain is expressed in vivo in the mouse urinary tract and functions as a catecholate siderophore receptor. Infect. Immun. 2006;74(6):3427–3436. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00107-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miko A., Rivas M., Bentancor A., Delannoy S., Fach P., Beutin L. Emerging types of Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) O178 present in cattle, deer, and humans from Argentina and Germany. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2014;4 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Montero D.A., Canto F.D., Velasco J., Colello R., Padola N.L., Salazar J.C., Martin C.S., Oñate A., Blanco J., Rasko D.A. Cumulative acquisition of pathogenicity islands has shaped virulence potential and contributed to the emergence of LEE-negative Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains. Emerg. Microb. Infect. 2019;8(1):486–502. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2019.1595985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montero D.A., Velasco J., Del Canto F., Puente J.L., Padola N.L., Rasko D.A., Farfán M., Salazar J.C., Vidal R. Locus of Adhesion and Autoaggregation (LAA), a pathogenicity island present in emerging Shiga Toxin–producing Escherichia coli strains. Sci. Rep. 2017;7(1):7011. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06999-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Newell D., La Ragione R. Enterohaemorrhagic and other Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC): where are we now regarding diagnostics and control strategies? Transbound Emerg Dis. 2018;65:49–71. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newton H.J., Sloan J., Bulach D.M., Seemann T., Allison C.C., Tauschek M., Robins-Browne R.M., Paton J.C., Whittam T.S., Paton A.W. Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli strains negative for Locus of Enterocyte Effacement. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009;15(3):372. doi: 10.3201/eid1502.080631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okonechnikov K., Golosova O., Fursov M., Team U. Unipro UGENE: a unified bioinformatics toolkit. Bioinformation. 2012;28(8):1166–1167. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Padola N.L., Sanz M.E., Blanco J.E., Blanco M., Blanco J., Etcheverria A.a.I., Arroyo G.H., Usera M.A., Parma A.E. Serotypes and virulence genes of bovine Shigatoxigenic Escherichia coli (STEC) isolated from a feedlot in Argentina. Vet. Microbiol. 2004;100(1):3–9. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1135(03)00127-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parma A., Sanz M., Blanco J., Blanco J., Viñas M., Blanco M., Padola N., Etcheverría A. Virulence genotypes and serotypes of verotoxigenic Escherichia coli isolated from cattle and foods in Argentina. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2000;16(8):757–762. doi: 10.1023/a:1026746016896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paton A.W., Paton J.C. Detection and characterization of Shiga toxigenic Escherichia coli by using multiplex PCR assays for stx1, stx2, eaeA, enterohemorrhagic E. coli hlyA, rfb O111, and rfb O157. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1998;36(2):598–602. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.2.598-602.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paton A.W., Paton J.C. Multiplex PCR for direct detection of Shiga toxigenic Escherichia coli strains producing the novel subtilase cytotoxin. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005;43(6):2944–2947. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.6.2944-2947.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paton A.W., Woodrow M.C., Doyle R.M., Lanser J.A., Paton J.C. Molecular characterization of a Shiga Toxigenic Escherichia coli O113: H21 strain lacking eae responsible for a cluster of cases of Hemolytic-Uremic Syndrome. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1999;37(10):3357–3361. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.10.3357-3361.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Postle K., Kadner R.J. Touch and go: tying TonB to transport. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;49(4):869–882. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rashid R.A., Tarr P.I., Moseley S.L. Expression of the Escherichia coli IrgA homolog adhesin is regulated by the ferric uptake regulation protein. Microb. Pathog. 2006;41(6):207–217. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rombel I.T., Sykes K.F., Rayner S., Johnston S.A. ORF-FINDER: a vector for high-throughput gene identification. Gene. 2002;282(1-2):33–41. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00819-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanz M., Viñas M., Parma A. Prevalence of bovine verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli in Argentina. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 1998;14(4):399–403. doi: 10.1023/a:1007427925583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmidt H., Zhang W.-L., Hemmrich U., Jelacic S., Brunder W., Tarr P., Dobrindt U., Hacker J., Karch H. Identification and characterization of a novel genomic island integrated at selC in locus of enterocyte effacement-negative, Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 2001;69(11):6863–6873. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.11.6863-6873.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shen S., Mascarenhas M., Rahn K., Kaper J.B., Karmal M.A. Evidence for a hybrid genomic island in verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli CL3 (serotype O113: H21) containing segments of EDL933 (serotype O157: H7) O islands 122 and 48. Infect. Immun. 2004;72(3):1496–1503. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.3.1496-1503.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steyert S.R., Sahl J.W., Fraser C.M., Teel L.D., Scheutz F., Rasko D.A. Comparative genomics and stx phage characterization of LEE-negative Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2012;2 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tarr P.I., Bilge S.S., Vary J.C., Jelacic S., Habeeb R.L., Ward T.R., Baylor M.R., Besser T.E. Iha: a novel Escherichia coli O157: H7 adherence-conferring molecule encoded on a recently acquired chromosomal island of conserved structure. Infect. Immun. 2000;68(3):1400–1407. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1400-1407.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Toma C., Espinosa E.M., Song T., Miliwebsky E., Chinen I., Iyoda S., Iwanaga M., Rivas M. Distribution of putative adhesins in different seropathotypes of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004;42(11):4937–4946. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.11.4937-4946.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Torres A.G., Redford P., Welch R.A., Payne S.M. TonB-dependent systems of uropathogenic Escherichia coli: aerobactin and heme transport and TonB are required for virulence in the mouse. Infect. Immun. 2001;69(10):6179–6185. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.10.6179-6185.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ulett G.C., Webb R.I., Schembri M.A. Antigen-43-mediated autoaggregation impairs motility in Escherichia coli. An. Microbiol. 2006;152(7):2101–2110. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28607-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yin X., Wheatcroft R., Chambers J.R., Liu B., Zhu J., Gyles C.L. Contributions of O island 48 to adherence of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157: H7 to epithelial cells in vitro and in ligated pig ileal loops. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;75(18):5779–5786. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00507-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]