Abstract

Introduction:

Preconception and interconception health care are critical means of identifying, managing, and treating risk factors originating prior to pregnancy that can harm fetal development and maternal health. However, many women in the U.S. lack health insurance, limiting their ability to access such care. State-level variation in Medicaid eligibility, particularly before and after the 2014 Medicaid expansions, offers a unique opportunity to test the hypothesis that increasing healthcare coverage for low-income women can improve preconception and interconception healthcare access and utilization, chronic disease management, overall health, and health behaviors.

Methods:

In 2018–2019, data on 58,365 low-income women aged 18–44 years from the 2011–2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System were analyzed and a difference-in-difference analysis was used to examine the impact of Medicaid expansions on preconception health.

Results:

Expanded Medicaid eligibility was associated with increased healthcare coverage and utilization, better self-rated health, and decreases in avoidance of care because of cost, heavy drinking, and binge drinking. Medicaid eligibility did not impact diagnoses of chronic conditions, smoking cessation, or BMI. Medicaid eligibility was associated with greater gains in health insurance, utilization, and health among married (versus unmarried) women. Conversely, women with any (versus no) dependent children experienced smaller gains in insurance following the Medicaid expansion, but greater take-up of insurance when eligibility increased and larger behavioral responses to gaining insurance.

Conclusions:

Expanded Medicaid coverage may improve access to and utilization of health care among women of reproductive age, which could ultimately improve preconception health.

INTRODUCTION

The U.S. ranks above other developed nations in rates of preterm delivery and low birth weight,1,2 as well as maternal morbidity and mortality.3 These rates have changed little over time,4,5 despite national efforts aimed at increasing access to prenatal care,6 including expansion of Medicaid—the public health insurance program for low-income families7—in the 1980s and 1990s to cover low-income women during pregnancy.8,9

Increasingly, it is recognized that health care only during the prenatal period is inadequate to address risks such as smoking, alcohol use, obesity, and chronic disease that adversely affect fetal development and maternal health, but originate prior to pregnancy and cannot be remediated fully during pregnancy.6,10–12 Treatments for these risks during pregnancy (e.g., pharmacotherapy or nicotine replacement, anti-hypertensive medication, and weight loss) can create new risks to fetal development or may simply come too late to prevent adverse effects.11,13,14 Thus, preconception and interconception (hereafter, referred to as “preconception” for brevity) preventive care have been heralded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,15 American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (2005),16 and March of Dimes (2002)12 as promising methods of improving outcomes for both mother and infant.6,10

An important barrier to preconception health is inadequate access to health insurance.17 As of 2012, about one fifth of all women of reproductive age18 and more than one third of low-income women of reproductive age (Appendix Table 1) were without health insurance, limiting access to health care (Appendix Table 2). Expansion of Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) allowed states to expand coverage to all non-elderly Americans with incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty level, theoretically increasing preconception insurance coverage for low-income women who would previously not have become Medicaid eligible until pregnancy.19 Moreover, the ACA requires Medicaid cover preventive care without cost sharing.20 Indeed, the 2014 expansion increased insurance coverage and access to care in general,21–23 among women of reproductive age in particular,24,25 and prior to conception.26,27 It remains unknown, however, whether these gains in coverage translated to improved health in domains known to be associated with pregnancy health, such as preventive care, chronic disease, and health behaviors. This study fills this gap by providing some of the first data at the national level examining the impact of expanded Medicaid eligibility (both prior to and after the ACA) on measures of preventive health care and behaviors among low-income women of reproductive age.

METHODS

Study Sample

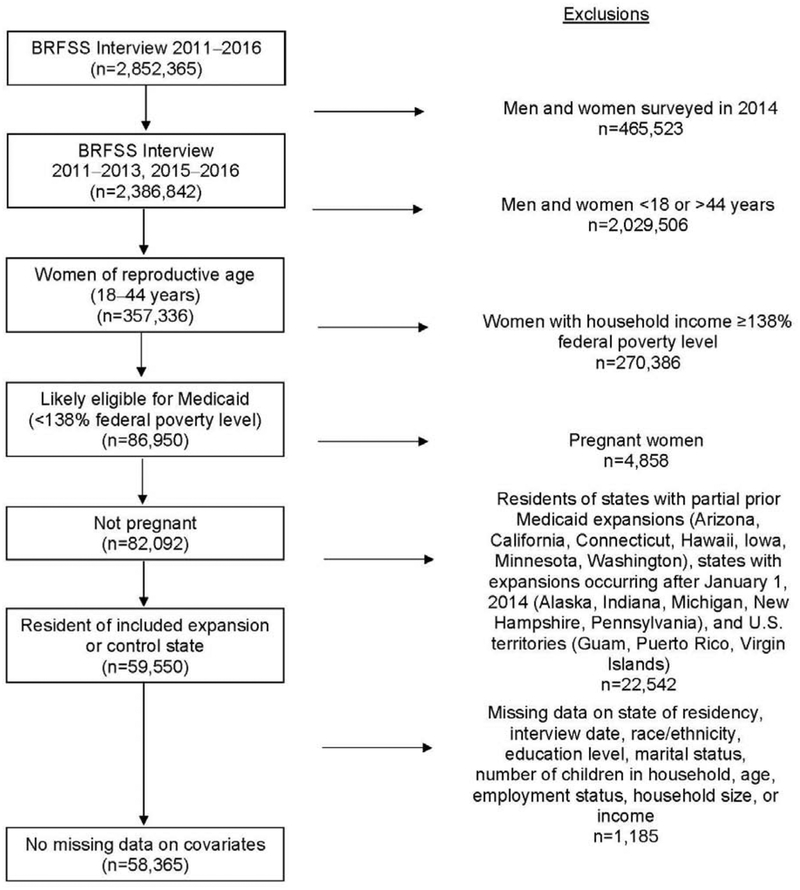

Data came from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS),28 administered annually in all 50 states and the District of Columbia (DC) to non-institutionalized U.S. residents aged ≥18 years. The sample included 2011–2013 (pre-expansion) and 2015–2016 (post-expansion) data on women of reproductive age (18–44 years, N=357,336), with low household income (<138% federal poverty level, n=86,950), who were not pregnant at the time of interview (n=82,092) (Figure 1). Data from 2014 were excluded because women reporting during 2014 would have had less than a full year exposure to Medicaid expansion, and because questions about use of care referred to previous periods of time, for example, over the past year or in the past 3 months. Because this research used de-identified data, it was deemed not human subjects research by Michigan State University’s IRB.

Figure 1.

Analytic sample from 2011‒2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey data.

A quasi-experimental, difference-in-differences (DID) study design was used to compare the change from pre- to post-Medicaid expansion in prevalence of self-reported outcomes between low-income women of reproductive age living in states that expanded Medicaid by January 1, 2014 (expansion states) and similar women in states that did not expand Medicaid (control states). As a second, complementary approach, treatment was measured using a simulated measure of Medicaid eligibility across the study period, as eligibility for Medicaid varied widely across states and over time.29

Measures

Expansion states included those that expanded Medicaid by January 1, 2014.30 The primary analysis excluded five states that expanded Medicaid between January 2014 and the end of 2015 as well seven states that had partial Medicaid expansions prior to 2014 (excluded n=22,542) and women with missing data on covariates (excluded n=1,185) for an analytic sample of 58,365 women in 38 states plus DC. Appendix Table 3 shows expansion/control status of states.

The simulated eligibility measure used a sample of women of reproductive age (18–44 years) drawn from the 2010–2012 American Community Survey (prior to the ACA Medicaid expansion) to create demographic subgroups defined by the combination of: state of residence, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, other race), age (18–24, 25–34, 35–44 years), marital status (married, unmarried), dependent children (yes/no), and educational attainment (less than high school, high school, some college, college graduate). Each woman’s household income and composition in the 2010–2012 data were used to calculate her eligibility for Medicaid in each year from 2010 to 2016 using Medicaid eligibility regulations for that year in her state. Next, mean eligibility within each demographic subgroup was used to calculate a simulated probability that a woman in a given subgroup would be eligible for Medicaid in a given year from 2010 to 2016. These simulated probabilities were merged onto the BRFSS data by demographic subgroup and year.

This approach takes advantage of variation in Medicaid eligibility by state and time, not limited to the 2014 expansion. Importantly, variation in simulated eligibility derives only from policy changes and does not suffer from the limitation that women’s earnings/income could change if they enroll in Medicaid. This measure also incorporates differences in baseline eligibility of both treatment and control states. This approach is common and widely accepted as valid.31,32 This approach yields a larger sample size (282,869) because it is not limited by state of residence or women’s household income. To compare results from this approach with those from the DID analysis, the simulated eligibility analysis was first conducted only among women in the 38 expansion and control states plus Washington, DC (n=212,836).

Outcomes included current health insurance (yes/no), healthcare access (avoiding care because of cost in the past year); preventive health care (checkup in past year, ever had blood cholesterol checked, and had cholesterol checked within previous year), overall health (self-rated health, physical and mental health distress [defined as ≥14 days not in good physical/mental health in the past month]); chronic disease (participant ever told that she has high blood pressure, high cholesterol, prediabetes, or diabetes; currently taking blood pressure medication [among those with high blood pressure]; currently taking insulin [among those with a diabetes diagnosis]), and health behaviors (smoking-cessation attempt in past year [among current smokers], current normal/underweight BMI [versus overweight/obese], and binge and heavy drinking in the past month). These measures were selected based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s recommended domains for monitoring and improving preconception health.33 Observations missing data on outcomes were excluded from analyses of those outcomes only; no outcome was missing >7% of observations (Appendix Table 5). A full description of variables, denominators, and missing values is available in Appendix Tables 4 and 5.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses included the unadjusted proportion (%) for all outcomes for the 58,365 women in the DID analysis, overall and by expansion/control state and pre-/post-expansion period. The parallel trends assumption for the DID analysis was assessed both graphically and empirically (Appendix Figure and Appendix Table 6).

The main analysis included a series of multivariable, linear probability DID models with robust SEs clustered by state using data from both the pre- and post-expansion periods. The DID model is as follows:

where Yist represents the outcome of interest for woman i in state s and year t. Expansion is a 0/1 indicator of whether the woman lives in an expansion or control state; post, a 0/1 indicator for whether the outcome is measured pre- or post-expansion; Yeart and States are vectors of year and state fixed effects that account for changes in the outcome over time and state-level contextual differences, respectively; Xist is a vector of individual covariates (age group, race/ethnicity, household income, educational attainment, employment status, marital status, household size, and whether or not the woman has dependent children in the household); and Zst is the quarterly average state unemployment rate. The parameter of interest (i.e., the DID estimator) is β1. The authors first estimated models with only year and state fixed effects (“minimally adjusted models,” and then added individual covariates and the state unemployment rate (“adjusted models”).

The second approach uses the simulated eligibility variable as a continuous measure of treatment in the regression model. For this analysis, all women of reproductive age are used (not limited by income). The model is as follows:

where Yigst represents the outcome of interest for woman i in group g and state s in year t. Simluated_eligibility is her probability of being eligible for Medicaid based on her demographic characteristics (g) and the income eligibility rules of her state of residence (s) in the year (t) of survey (computed based on the American Community Survey data, as described in the Measures section), and State′ s x Group′gβ2 and Year′t x Group′ gβ3 are interactions between vectors of state and demographic subgroup and state and year fixed effects. The parameter of interest,β1, represents the change in Yigst when all women in the demographic group are eligible for Medicaid versus when no women are eligible.

The impact of the Medicaid expansion was hypothesized to be greater among women without dependent children (versus those with dependent children, who may have previously qualified for Medicaid under more generous parental eligibility levels), unmarried (versus married) women, and women aged ≥26 years who would not have benefitted from the dependent coverage provision of the ACA. A Holm–Bonferroni correction was applied to account for multiple hypothesis testing.

Secondary analyses included the simulated eligibility analysis using women in all 50 states and DC instead of only the 38 expansion/control states, and the DID analysis using different definitions of expansion and control states (Appendix Table 3). Although unweighted data were used in the main analyses (as this analysis used only a sample, not the entire BRFSS data set), secondary analyses included the BRFSS weights for comparison.

RESULTS

Medicaid expansion was associated with a minimally adjusted increase in healthcare coverage (9.7 percentage points), report of a checkup in the past year (3.7 percentage points), taking blood pressure medication (6.8 percentage points), and taking insulin (4.9 percentage points), and with a 7.4 percentage point decrease in avoiding seeking care because of cost (Table 1). The parallel trend assumption was met for 15 of 20 outcomes, with the exceptions being having a checkup in the past year, having cholesterol checked in the past year, self-rated health, physical distress, and body weight (Appendix Figure and Appendix Table 6).

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics by Expansion Status and Difference-in-Difference (DID) Estimates (n=58,365)

| Overall | Expansion states | Control states | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | n (%) | Pre-expansion n (%) | Post-expansion n (%) | Percentage point change pre to post | Pre-expansion n (%) | Post-expansion n (%) | Percentage point change pre to post | Minimally adjustedb DID β (p-value) |

Adjustedc DID β (p-value) |

| Overall | 58,365 | 10,628 | 5,871 | 26,670 | 15,196 | ||||

| Race | |||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white/other | 34,434 (59.0) |

6,315 (59.5) |

3,599 (61.3) |

1.8 | 15,784 (59.2) |

8,736 (57.5) |

−1.7 | – | – |

| Non-Hispanic black | 11,375 (19.5) |

1,471 (13.8) |

771 (13.1) |

−0.7 | 6,049 (22.7) |

3,084 (20.3) |

−2.4 | – | – |

| Hispanic | 12,556 (21.5) |

2,842 (26.7) |

1,501 (25.6) |

−1.1 | 4,837 (18.1) |

3,376 (22.2) |

4.1 | – | – |

| Education | |||||||||

| Did not graduate high school | 10,283 (17.6) |

1,906 (17.9) |

981 (16.7) |

−1.2 | 4,823 (18.1) |

2,573 (16.9) |

−1.2 | – | – |

| Graduated high school | 21,269 (36.4) |

3,916 (36.8) |

2,155 (36.7) |

−0.1 | 9,709 (36.4) |

5,489 (36.1) |

−0.3 | – | – |

| Attended college | 19,403 (33.2) |

3,585 (33.7) |

1,976 (33.7) |

0.0 | 8,838 (33.1) |

5,004 (32.9) |

−0.2 | – | – |

| Graduated college | 7,410 (12.7) |

1,221 (11.5) |

759 (12.9) |

1.4 | 3,300 (12.4) |

2,130 (14.0) |

1.6 | – | – |

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Married/Unmarried couple vs Divorced, widowed, separated, never married | 21,094 (36.1) |

3,966 (37.3) |

2,217 (37.8) |

0.5 | 9,256 (34.7) |

5,655 (37.2) |

2.5 | – | – |

| Dependent children in household? | |||||||||

| Yes | 46,146 (79.1) |

8,485 (79.8) |

4,426 (75.4) |

−4.4 | 21,438 (80.4) |

11,797 (77.6) |

−2.8 | – | – |

| Health insurance | |||||||||

| Healthcare coverage | 38,469 (66.1) |

6,659 (62.8) |

4,864 (83.2) |

20.4 | 16,135 (60.7) |

10,811 (71.4) |

10.7 |

9.2 (<0.01) |

9.0 (<0.01) |

| Access to health care | |||||||||

| Avoided seeking care due to cost | 20,424 (35.1) |

3,972 (37.4) |

1,254 (21.4) |

−16.0 | 10,511 (39.5) |

4,687 (30.9) |

−8.6 |

−7.3 (<0.01) |

−7.4 (<0.01) |

| Preventive health care | |||||||||

| Check-up in last year | 34,922 (60.8) |

6,117 (58.4) |

3,863 (67.2) |

8.7 | 15,552 (56.2) |

9,390 (62.9) |

3.7 |

5.2 (<0.01) |

5.1 (<0.01)d |

| Ever had blood cholesterol checked | 20,901 (61.8) |

4,088 (61.0) |

1,711 (64.9) |

3.9 | 10,777 (61.3) |

4,325 (62.5) |

1.2 | 2.0 (0.24) | 2.2 (0.13) |

| Last cholesterol check within a year | 13,173 (64.1) |

2,515 (62.3) |

1,140 (67.9) |

5.6 | 6,744 (63.6) |

2,774 (65.5) |

1.9 | 3.8 (0.05) | 3.6 (0.06) |

| Overall health | |||||||||

| Self-rated health good/very good/excellent | 44,154 (75.9) |

7,877 (74.2) |

4,435 (75.8) |

1.6 | 20,296 (76.3) |

11,546 (76.2) |

−0.1 | 1.5 (0.16) | 2.3 (0.03) |

| Experienced physical health distress in past month | 9,190 (16.0) |

1,808 (17.3) |

947 (16.4) |

−0.9 | 4,152 (15.8) |

2,283 (15.3) |

−0.5 | −0.5 (0.55) |

−1.0 (0.19) |

| Experienced mental health distress in past month | 13,914 (24.2) |

2,603 (24.8) |

1,412 (24.4) |

−0.4 | 6,338 (24.1) |

3,561 (23.8) |

−0.3 | −0.6 (0.56) |

−1.1 (0.23) |

| Chronic disease | |||||||||

| Has been told she has/had high blood pressure | 6,316 (17.9) |

1,216 (17.5) |

446 (16.2) |

−1.3 | 3,407 (18.6) |

1,247 (17.2) |

−1.4 | −0.1 (0.95) |

−0.6 (0.62) |

| Has been told she has/had high cholesterol | 4,726 (22.7) |

983 (24.2) |

324 (19.0) |

−5.2 | 2,549 (23.8) |

870 (20.2) |

−3.6 | −1.2 (0.25) |

−1.6 (0.13) |

| Has been told she has/had diabetes | 3,490 (6.0) |

601 (5.7) |

323 (5.5) |

−0.2 | 1,637 (6.1) |

929 (6.1) |

0.0 | −0.1 (0.69) |

−0.4 (0.25) |

| Has been told she has/had prediabetes or borderline diabetes | 1,798 (7.8) |

354 (7.2) |

201 (8.8) |

1.6 | 700 (7.6) |

543 (8.2) |

0.6 | 0.0 (0.97) | −0.3 (0.77) |

| Currently taking blood pressure medicationa | 3,526 (55.9) |

644 (53.0) |

259 (58.2) |

5.2 | 1,935 (56.8) |

688 (55.2) |

−1.6 |

7.3 (<0.01)d |

7.9 (<0.01)d |

| Currently takes insulina | 481 (34.9) |

111 (30.7) |

36 (34.3) |

3.6 | 237 (37.0) |

97 (35.7) |

−1.3 |

12.4 (0.02) |

11.4 (<0.01) |

| Health behaviors | |||||||||

| Smoking cessation attempt in last yeara | 11,814 (64.7) |

2,240 (62.2) |

1,119 (61.9) |

−0.3 | 5,662 (66.0) |

2,793 (65.4) |

−0.6 | 0.2 (0.90) | 0.3 (0.87) |

| Underweight or normal weight vs overweight or obese | 19,481 (35.8) |

3,694 (37.0) |

1,973 (36.4) |

−0.6 | 8,902 (35.6) |

4,912 (35.1) |

−0.5 | −0.1 (0.92) |

−0.3 (0.75) |

| Binge drinking | 7,893 (14.3) |

1,463 (14.5) |

770 (13.7) |

−0.8 | 3,646 (14.5) |

2,014 (13.9) |

−0.6 | −0.5 (0.55) |

−0.8 (0.25) |

| Heavy drinking | 2,496 (4.5) |

482 (4.8) |

241 (4.3) |

−0.5 | 1,125 (4.5) |

648 (4.5) |

0.0 | −0.7 (0.09) |

−1.0 (0.01) |

Note: Boldface indicates statistical significance (p<0.05).

This item was asked to only a subset of the sample based on responses to prior survey items (Appendix Tables 4 and 5).

Models include only state, year, and the interaction between expansion status and pre/post time period.

Models additionally adjusted for state, year, race, education, marital status, dependent children, age group, employment status, household size, income group, and state average unemployment rate.

Reject null hypothesis after applying Holm-Bonferroni correction.

After adjustment for individual covariates (age group, race/ethnicity, household income, educational attainment, employment status, marital status, household size, and whether or not the woman has dependent children in the household), 2014 Medicaid expansion was associated with a 9.0 (95% CI=2.9, 15.2) percentage point increase in healthcare coverage and a 7.4 (95% CI= −12.2, −2.6) percentage point decrease in avoiding care because of cost (Table 1, last column and Table 2, first column). The expansion was associated with percentage point increases of 7.9 (95% CI=3.1, 12.8) in taking blood pressure medication and 11.4 (95% CI=3.0, 19.7) in taking insulin. The expansion was associated with a 1.0 (95% CI= −1.8, −0.2) percentage point decrease in heavy drinking. Associations were larger among married women and those with no dependent children compared with unmarried women and those with dependent children (Table 2). Results were similar across age groups (Appendix Table 7), with increases in taking medication for chronic conditions seen primarily in older women. After applying the Holm–Bonferroni correction, fewer findings were statistically significant (only blood pressure medication and checkups among all women and insurance, avoiding care, and cholesterol check among women with no dependent children) (Table 2, footnote d).

Table 2.

Adjusteda Difference-in-Difference (DID) Estimates Stratified by Marital Status and Dependent Children in the Household

| Outcome | All women (n=58,365) |

Married (n=21,094) |

Not married (n=37,271) | Dependent children (n=46,146) |

No dependent children (n=12,219) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DID estimate (95% CI) | DID estimate (95% CI) | DID estimate (95% CI) | DID estimate (95% CI) | DID estimate (95% CI) | |

| Health insurance | |||||

| Has healthcare coverage | 9.0 (2.9, 15.2) | 11.9 (4.1, 19.7) | 7.6 (2.2, 12.9) | 7.6 (0.8, 14.4) | 13.9 (8.7, 19.2)d |

| Access to health care | |||||

| Avoided seeking care due to cost | −7.4 (−12.2, −2.6) | −8.5 (−14.4, −2.6) | −6.8 (−11.5, −2.2) | −6.7 (−11.9, −1.5) | −10.5 (−16.2, −4.8)d |

| Preventive health care | |||||

| Check-up in last year | 5.1 (1.8, 8.4)c,d | 6.2 (1.3, 11.2) | 4.5 (1.3, 7.9) | 4.6 (1.3, 7.9) | 7.2 (2.5, 11.9) |

| Ever had blood cholesterol checked | 2.2 (−0.7, 5.1) | −1.7 (−6.5, 3.1) | 4.6 (1.3, 7.9) | 0.8 (−3.0, 4.6) | 6.8 (3.1, 10.4)d |

| Last cholesterol check within a year | 3.6 (−0.1, 7.2)c | 2.1 (−3.1, 7.4) | 4.4 (−0.2, 8.9) | 3.4 (−0.1, 6.9) | 4.5 (−3.8, 12.9) |

| Overall health | |||||

| Self-rated health good/very good/excellent | 2.3 (0.3, 4.3)c | 2.3 (−0.4, 5.0) | 2.3 (−0.2, 4.8) | 2.4 (−0.3, 5.0) | 1.9 (−1.4, 5.2) |

| Experienced physical health distress in past month | −1.0 (−2.6, 0.5)c | 0.7 (−1.7, 3.0) | −2.0 (−4.2, 0.2) | −1.8 (−3.7, 0.2) | 1.7 (−0.1, 3.5) |

| Experienced mental health distress in past month | −1.1 (−3.0, 0.7) | −1.3 (−4.2, 1.7) | −1.0 (−3.0, 1.0) | −1.2 (−3.3, 1.0) | −1.4 (−5.0, 2.2) |

| Chronic disease | |||||

| Told high blood pressure | −0.6 (−3.2, 1.9) | −2.1 (−5.8, 1.7) | 0.3 (−3.0, 3.5) | −1.3 (−3.9, 1.4) | 1.4 (−3.1, 5.9) |

| Told high cholesterol | −1.6 (−3.6, 0.5) | −1.8 (−6.8, 3.2) | −1.3 (−5.3, 2.7) | −1.1 (−3.7, 1.4) | −3.7 (−8.1, 0.7) |

| Told diabetes | −0.4 (−1.1, 0.3) | −0.5 (−2.0, 0.9) | −0.3 (−1.1, 0.6) | −0.4 (−1.2, 0.4) | −0.3 (−2.0, 1.3) |

| Told prediabetes | −0.3 (−2.7, 2.0) | −2.3 (−5.3, 0.7) | 0.7 (−2.0, 3.5) | −0.9 (−3.7, 1.8) | 1.8 (−1.6, 5.2) |

| Currently taking blood pressure medicationb | 7.9 (3.1, 12.8)d | 9.0 (−0.2, 18.2) | 8.7 (2.0, 15.3) | 6.8 (0.4, 13.2) | 10.6 (1.8, 19.3) |

| Currently takes insulinb | 11.4 (3.0, 19.7) | 22.7 (2.5, 42.9) | 5.9 (−7.6, 19.3) | 8.9 (0.3, 17.5) | 19.0 (−2.4, 40.4) |

| Health behaviors | |||||

| Smoking cessation attempt in last yearb | 0.3 (−3.3, 3.9) | −1.6 (−6.1, 2.8) | 1.2 (−3.5, 5.9) | 0.5 (−3.6, 4.5) | −1.6 (−8.3, 5.2) |

| Underweight/normal vs overweight/obese | −0.3 (−1.9, 1.4)c | 2.0 (−1.9, 5.9) | −1.3 (−3.2, 0.7) | −0.2 (−2.1, 1.7) | −0.1 (−3.4, 3.2) |

| Binge drinking | −0.8 (−2.3, 0.6) | −0.7 (−2.6, 1.2) | −1.0 (−2.8, 0.8) | −0.8 (−2.4, 0.7) | −1.3 (−4.5, 2.0) |

| Heavy drinking | −1.0 (−1.8, −0.2) | −0.8 (−1.8, 0.2) | −1.1 (−2.2, 0.0) | −0.8 (−1.5, 0.0) | −2.1 (−4.3, 0.1) |

Note: Boldface indicates statistical significance (p<0.05).

Models additionally adjusted for state, year, race, education, marital status, dependent children, age group, employment status, household size, income group, and state average unemployment rate.

This item was asked to only a subset of the sample (Appendix Tables 4 and 5).

Did not meet parallel trends assumption.

Reject null hypothesis after applying Holm-Bonferroni correction.

Simulated eligibility estimates indicated that increasing Medicaid eligibility to all women of reproductive age would be associated with percentage point increases of 15.9 (95% CI=8.0, 23.7) in health insurance coverage, 7.4 (95% CI=0.7, 14.2) in having a checkup in the past year, 8.8 (95% CI=1.4, 16.2) in having had a cholesterol check within a year, and 2.3 (95% CI=0.5, 4.2) in reporting good self-rated health, and percentage point decreases of 9.9 (95% CI= −17.2, −2.5) in avoiding care because of cost and 3.3 (95% CI= −6.5, −0.1) in binge drinking (Table 3). In general, eligibility was associated more strongly with outcomes among married women and those with dependent children. Among married women only, eligibility was associated with increases in taking insulin; among women with dependent children only, eligibility was associated with declines in physical health distress and heavy drinking (Table 3).

Table 3.

Adjusteda Associations Between Simulated Probability of Medicaid Eligibility and Outcomes in 38 States and Washington DC

| Outcome | All women (n=212,836) |

Married (n=123,397) |

Not married (n=89,439) |

Dependent children (n=149,618) |

No dependent children (n=63,218) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DID estimate (95% CI) |

DID estimate (95% CI) |

DID estimate (95% CI) |

DID estimate (95% CI) |

DID estimate (95% CI) |

|

| Health insurance | |||||

| Has healthcare coverage |

15.9 (8.0, 23.7)c |

32.3 (18.7, 45.8)c |

12.9 (6.1, 19.6)c |

30.6 (18.6, 42.6)c |

9.4 (3.7, 15.2)c |

| Access to health care | |||||

| Avoided seeking care due to cost |

−9.9 (−16.5, −3.4) |

−17.5 (−28.5, −6.4)c |

−8.6 (−14.6, −2.6) |

−20.5 (−30.6, −10.4)c |

−5.3 (−10.5, −0.1) |

| Preventive health care | |||||

| Check-up in last year |

7.4 (0.7, 14.2) |

16.7 (5.3, 28.2) |

5.8 (−0.4, 11.9) |

13.5 (4.0, 23.1) |

4.8 (−1.4, 11.0) |

| Ever had blood cholesterol checked | 0.7 (−3.9, 5.4) |

−3.6 (−15.4, 8.2) |

1.5 (−4.0, 7.0) |

2.9 (−8.5, 14.3) |

−0.1 (−5.9, 5.6) |

| Last cholesterol check within a year |

8.8 (1.4, 16.2) |

23.5 (6.4, 40.6) |

6.0 (−2.3, 14.2) |

14.9 (4.1, 25.8) |

5.6 (−3.4, 14.7) |

| Overall health | |||||

| Self-rated health good/very good/excellent |

2.3 (0.5, 4.2) |

2.7 (−2.4, 7.9) |

2.3 (0.4, 4.1) |

6.5 (1.2, 11.8) |

0.5 (−1.8, 2.8) |

| Experienced physical health distress in past month | −0.9 (−2.9, 1.1) |

2.3 (−3.4, 7.9) |

−1.5 (−3.7, 0.8) |

−4.1 (−7.5, −0.6) |

0.5 (−1.6, 2.6) |

| Experienced mental health distress in past month | −1.9 (−4.7, 1.0) |

1.2 (−4.4, 6.9) |

−2.5 (−5.7, 0.8) |

−1.3 (−7.0, 4.4) |

−2.1 (−5.2, 0.9) |

| Chronic disease | |||||

| Told high blood pressure | 2.0 (−2.8, 6.7) |

6.3 (−5.4, 18.1) |

1.2 (−3.4, 5.9) |

5.0 (−1.2, 11.2) |

0.7 (−4.5, 6.0) |

| Told high cholesterol | −1.3 (−6.0, 3.3) |

3.9 (−9.0, 16.8) |

−2.3 (−7.8, 3.1) |

−1.2 (−9.8, 7.4) |

−1.4 (−6.7, 3.9) |

| Told diabetes | −0.2 (−1.2, 0.9) |

1.4 (−1.5, 4.2) |

−0.5 (−1.7, 0.8) |

0.3 (−2.3, 2.8) |

−0.4 (−1.8, 1.0) |

| Told prediabetes | 0.3 (−3.8, 4.3) |

−2.4 (−9.7, 4.8) |

0.9 (−3.6, 5.4) |

−2.1 (−6.2, 2.1) |

1.7 (−2.8, 6.2) |

| Currently taking blood pressure medicationb | 3.3 (−8.8, 15.4) |

−4.9 (−54.5, 44.6) |

4.7 (−11.1, 20.5) |

−7.8 (−23.9, 8.2) |

13.5 (−5.9, 33.0) |

| Currently takes insulinb | 34.4 (−10.7, 79.5) |

104.1 (10.6, 197.7) |

14.7 (−27.1, 56.5) | 22.7 (−62.9, 108.3) |

44.7 (11.3, 78.1) |

| Health behaviors | |||||

| Smoking cessation attempt in last yearb | −2.6 (−10.3, 5.1) |

4.7 (−10.7, 20.0) |

−4.1 (−11.7, 3.6) |

7.4 (−8.5, 23.3) |

−10.3 (−19.1, −1.6) |

| Underweight/normal vs overweight/obese | −0.3 (−3.8, 3.2) |

4.6 (−6.4, 15.7) |

−1.2 (−4.7, 2.4) |

0.9 (−6.1, 8.0) |

−0.9 (−5.7, 4.0) |

| Binge drinking |

−3.3 (−6.5, −0.1) |

4.4 (−2.8, 11.7) |

−4.7 (−8.2, −1.3) |

−2.1 (−7.3, 3.2) |

−3.8 (−7.6, −0.1) |

| Heavy drinking | −1.8 (−3.9, 0.4) |

−1.7 (−6.0, 2.5) |

−1.8 (−4.2, 0.6) |

−3.6 (−6.0, −1.2) |

−1.0 (−3.5, 1.6) |

Note: Boldface indicates statistical significance (p<0.05).

Models additionally adjusted for demographic subgroup-by-state and subgroup-by-year fixed effects.

This item was asked to only a subset of the sample (Appendix Tables 4 and 5).

Reject null hypothesis after applying Holm-Bonferroni correction.

Estimates from analyses using different definitions of expansion and control states slightly attenuated results compared with the estimates in Table 2 (Appendix Tables 8 and 9). Applying BRFSS weights also yielded similar, slightly attenuated, findings (Appendix Table 10).

DISCUSSION

These findings showed that expanded Medicaid eligibility for low-income women of reproductive age was associated with increased healthcare coverage and utilization, better self-rated health, decreased avoidance of care because of cost, and decreased heavy and binge drinking but did not impact diagnoses of chronic disease, smoking cessation, or BMI. Married women experienced greater gains in health insurance, utilization, and health compared with unmarried women, and women with dependent children experienced smaller gains in insurance but larger behavioral responses to gaining insurance.

This study makes an important and unique contribution by using national data to examine impacts of Medicaid eligibility—both prior to and because of the 2014 ACA expansion—on preventive health care and health among women of reproductive age. Previous research has demonstrated that the 2014 Medicaid expansion increased insurance coverage and access to care among women overall (aged 19–64 years),34,35 women of reproductive age (19–44 years),25 and prior to pregnancy.26 Although one early study found that Medicaid expansion did not improve preventive health care or health behaviors by 2015 among women aged 19–64 years,34 a recent study found increases in blood pressure and cholesterol screening and mammograms among women aged 19–64 years in 2014–2017 compared with 2010–2013.35 These results, which focus exclusively on women of reproductive age (18–44 years), show improvements in several (although not all) indicators of preventive care, chronic disease management, and drinking. Indeed, the perinatal period of a woman’s life may be a window of opportunity during which women more likely adopt healthier behaviors and heed medical advice.36–38

Another contribution of this study is the simulated eligibility measure. By using a continuous measure of eligibility over the entire study period, this study accounts for the fact that some women may have been eligible for Medicaid prior to the expansion or in non-expansion states (e.g., because of income or dependent children). These analyses demonstrated that some outcomes (e.g., cholesterol check and binge drinking) were not impacted, on average, by the 2014 expansion but did respond positively to overall increases in Medicaid eligibility, highlighting the value of simulated eligibility. When treatment is measured by a dichotomous yes/no indicator of expansion, variation in the extent of treatment across states is ignored. The simulated eligibility measure provides a measure of the extent of treatment, which differed across states. This more accurate measure provides greater statistical power and incorporates a dose (i.e., expanded coverage) response relationship that is expected.

Prior expansions of Medicaid in the 1980s were designed to increase enrollment in prenatal care by increasing Medicaid eligibility during pregnancy, and demonstration waiver programs in the 1990s began extending Medicaid eligibility to cover family planning services (a form of preconception health care).40 Yet, these expansions were not associated with improvements in birth outcomes.8,9 Recently, Brown and colleagues40 reported that the 2014 Medicaid expansion did in fact improve black/white disparities in low birth weight and preterm birth, suggesting that expanding health insurance coverage for women prior to conception—which can enable them to access preconception care and thus improve preconception health—offers promise in terms of improving subsequent pregnancy outcomes. These findings indicate support for this process: Low-income women of reproductive age did utilize preventive care and experience some improvements in health following state Medicaid expansions.

Limitations

This study was limited by the relatively short follow-up period and data available in BRFSS.28 Several outcomes are conditional on a diagnosis (e.g., taking blood pressure medication). Thus, a change in the proportion taking medication could reflect either a change in the number of women with high blood pressure or a true behavioral change. These data, however, do not reflect changes in diagnoses associated with Medicaid. Medicaid expansion was not associated with smoking-cessation attempts or BMI, suggesting that these domains of preconception health may not be sensitive to healthcare use, at least over a period of 2 years. Moreover, this study could not examine changes in contraceptive use, interpregnancy interval, or unintended pregnancy, which are associated with pregnancy health41,42 and can be influenced by healthcare coverage and access.43,44 Although not all findings remained significant after accounting for multiple testing, the Holm–Bonferroni correction is conservative, and these findings still suggest impacts that are clinically relevant. Not all Medicaid-eligible women will enroll in Medicaid or seek preventive care services, and only a fraction of reproductive age women in BRFSS will go on to become pregnant in the near future, potentially limiting the population-level impact of these findings on pregnancy health. An important next step is examining the impact of Medicaid expansion on pregnancy outcomes using data (unavailable in BRFSS) on women who do become pregnant post-expansion.

CONCLUSIONS

These findings indicate that expanding eligibility for Medicaid improves some, although not all, measures of health among low-income women of reproductive age. Even if only a fraction of these women go on to become pregnant in subsequent years, they may enter pregnancy in better health, particularly with respect to management of chronic disease. In light of the increased emphasis on preconception health care as a method of improving health at the outset of pregnancy,6,10,12 and subsequently, improving outcomes for both women and infants, this study provides important data suggesting that increasing health insurance coverage for low-income women prior to pregnancy may play an important role in preconception health.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by Michigan Applied Public Policy Research pilot funding from the Michigan State University Institute for Public Policy and Social Research and by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development R01HD095951 (Margerison, Principal Investigator).

Footnotes

This work in a preliminary format was presented at the Population Association of America Annual Meeting in Denver, Colorado in April, 2018.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.March of Dimes. Born Too Soon. www.marchofdimes.org/mission/global-preterm.aspx. Updated 2017. Accessed September 20, 2017.

- 2.Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Low Birth Weight. www.oecd.org/els/family/CO_1_3_Low_birth_weight.pdf. Updated October 31, 2018. Accessed April 18, 2019.

- 3.Carroll A. Why is US maternal mortality rising? JAMA. 2017;318(4):321 10.1001/jama.2017.8390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Margerison-Zilko C. The contribution of maternal birth cohort to term small for gestational age in the United States 1989‒2010: an age, period, and cohort analysis. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2014;28(4):312‒321. 10.1111/ppe.12127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, Driscoll AK, Drake P. Births: final data for 2017. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2018;67(8):1‒50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atrash H, Jack B, Johnson K, et al. Where is the “W”oman in MCH? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(6 suppl 2):S259‒S265. 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bitler M, Zavodny M. Medicaid: a review of the literature. NBER Work Pap Ser.2014;20169:1‒42. 10.3386/w20169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dave D, Decker S, Kaestner R, Simon KI. Re-examining the effects of Medicaid expansion for pregnant women. NBER Work Pap Ser. 2008;14591:1‒41. 10.3386/w14591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howell EM. The impact of the Medicaid expansions for pregnant women: a synthesis of the evidence. Med Care Res Rev. 2001;58(1):3‒30. 10.1177/107755870105800101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jack BW, Atrash H, Coonrod DV, Moos MK, O’Donnell J, Johnson K. The clinical content of preconception care: an overview and preparation of this supplement. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(6 suppl 2):S266‒S279. 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.07.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Floyd RL, Johnson KA, Owens JR, et al. A national action plan for promoting preconception health and health care in the United States (2012‒2014). J Womens Health. 2013;22(10):797‒ 802. 10.1089/jwh.2013.4505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.March of Dimes. March of Dimes updates: is early prenatal care too late? Contemp Ob Gyn.2002;12:54‒72. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunlop AL, Gardiner PM, Shellhaas CS, Menard MK, McDiarmid MA. The clinical content of preconception care: the use of medications and supplements among women of reproductive age. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(6 suppl B):S367‒S372. 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.07.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gardiner PM, Nelson L, Shellhaas CS, et al. The clinical content of preconception care: nutrition and dietary supplements. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(6 suppl 2):S345‒S356. 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson K, Posner SF, Biermann J, et al. Recommendations to improve preconception health and health care--United States. A report of the CDC/ATSDR Preconception Care Work Group and the Select Panel on Preconception Care. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR06):1‒23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. The importance of preconception care in the continuum of women’s health care. ACOG Committee Opinion number 313. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(3):665‒666. 10.1097/00006250-200509000-00052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hawks R, McGinn A, Bernstein P, Tobin JN. Exploring preconception care: insurance status, race/ethnicity, and health in the pre-pregnancy period. Matern Child Health J. 2018;22(8):1103‒ 1110. 10.1007/s10995-018-2494-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guttmacher Institute. Uninsured rate among women of reproductive age has fallen more than one-third under the Affordable Care Act. www.guttmacher.org/article/2016/11/uninsured-rate-among-women-reproductive-age-has-fallen-more-one-third-under. Published November 17, 2016. Accessed August 17, 2017.

- 19.U.S. Congress. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 42 U.S.C. § 18001 (2010).

- 20.Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid’s Role for Women. www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/fact-sheet/medicaids-role-for-women/. Published March 28, 2019. Accessed April 18, 2019.

- 21.Kaestner R, Garrett B, Chen J, Gangopadhyaya A, Fleming C. Effects of ACA Medicaid expansions on health insurance coverage and labor supply. J Policy Anal Manage. 2017;36(3):608‒642. 10.1002/pam.21993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mazurenko O, Balio CP, Agarwal R, Carroll AE, Menachemi N. The effects of Medicaid expansion under the ACA: a systematic review. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(6):944‒950. 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wherry LR, Miller S. Early coverage, access, utilization, and health effects associated with the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansions: a quasi-experimental study. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(12):795‒803. 10.7326/m15-2234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gunja M, Collins S, Doty M, Beutel S. How the Affordable Care Act Has Helped Women Gain Insurance and Improved Their Ability to Get Health Care. The Commonwealth Fund. www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2017/aug/how-affordable-care-act-has-helped-women-gain-insurance-and?redirect_source=/publications/issue-briefs/2017/aug/aca-helped-women-gain-insurance-and-access. Published August 10, 2017. Accessed February 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnston EM, Strahan AE, Joski P, Dunlop AL, Adams EK. Impacts of the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion on women of reproductive age: differences by parental status and state policies. Womens Health Issues. 2018;28(2):122‒129. 10.1016/j.whi.2017.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clapp M, James K, Kaimal A, Daw JR. Preconception coverage before and after the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansions. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(6):1394‒1400. 10.1097/aog.0000000000002972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adams E, Dunlop AL, Strahan A, Joski P, Applegate M, Sierra E. Prepregnancy insurance and timely prenatal care for Medicaid births: before and after the Affordable Care Act in Ohio. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2019;28(5):654‒664. 10.1089/jwh.2017.6871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.CDC. The BRFSS Data User Guide. www.cdc.gov/brfss/data_documentation/pdf/UserguideJune2013.pdf. Published August 15, 2013. Accessed February 2019.

- 29.Kaiser Family Foundation. Trends in Medicaid Eligibility Limits. www.kff.org/data-collection/trends-in-medicaid-income-eligibility-limits/. Updated 2019. Accessed February 2019.

- 30.Wehby GL, Lyu W. The impact of the ACA Medicaid expansions on health insurance coverage through 2015 and coverage disparities by age, race/ethnicity, and gender. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(2):1248‒1271. 10.1111/1475-6773.12711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Currie J, Gruber J. Health insurance eligibility, utilization of medical care, and child health. Q J Econ. 1996;111(2):431‒466. 10.2307/2946684. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gruber J, Simon K. Crowd-out 10 years later: have recent public insurance expansions crowded out private health insurance? J Health Econ. 2008;27(2):201‒217. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robbins C, Zapata L, Farr S, et al. Core state preconception health indicators - Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System and Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2009. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2014;63(ss03):1‒62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simon K, Soni A, Cawley J. The impact of health insurance on preventive care and health behaviors: evidence from the first two years of the ACA Medicaid expansions. J Policy Anal Manage. 2017;36(2):390‒417. 10.1002/pam.21972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee L, Monuteaux M, Galbraith A. Women’s affordability, access, and preventive care after the Affordable Care Act. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(5):631‒638. 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bloch M, Parascandola M. Tobacco use in pregnancy: a window of opportunity for prevention. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(9):e489‒e490. 10.1016/s2214-109x(14)70294-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Louis GM, Cooney MA, Lynch CD, Handal A. Periconception window: advising the pregnancy-planning couple. Fertil Steril. 2008;89(2 suppl):e119‒e121. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.12.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Phelan S. Pregnancy: a “teachable moment” for weight control and obesity prevention. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(2):135.e1‒135.e8. 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gold RB, Alrich C. Role of Medicaid family planning waivers and Title X in enhancing access to preconception care. Womens Health Issues. 2008;18(6 suppl):S47‒S51. 10.1016/j.whi.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown C, Moore J, Felix H, et al. Association of state Medicaid expansion status with low birth weight and preterm birth. JAMA. 2019;321(16):1598‒1609. 10.1001/jama.2019.3678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheng D, Schwarz E, Douglas E, Horon I. Unintended pregnancy and associated maternal preconception, prenatal and postpartum behaviors. Contraception. 2009;79(3):194‒198. 10.1016/j.contraception.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shah PS, Balkhair T, Ohlsson A, Beyene J, Scott F, Frick C. Intention to become pregnant and low birth weight and preterm birth: a systematic review. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15(2):205‒216. 10.1007/s10995-009-0546-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ghosh A, Simon K, Sommers B. The effect of state Medicaid expansions on prescription drug use: evidence from the Affordable Care Act. NBER Work Pap Ser. 2017;23044:1‒35. 10.3386/w23044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Culwell KR, Feinglass J. The association of health insurance with use of prescription contraceptives. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2007;39(4):226‒230. 10.1363/3922607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.