Abstract

Youth sport is a key physical activity opportunity for children and adolescents. Several factors influence youth sport participation, including social factors, but this has not to date been clearly delineated. This study is a scoping review to survey the literature on the influence of family and peers on youth sports participation. The review identified 111 articles of which the majority were cross-sectional, included boys and girls, and were conducted primarily in the United States, Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom. The articles were grouped into 8 research themes: (1) reasons for participation, (2) social norms, (3) achievement goal theory, 4) family structure, (5) sports participation by family members, (6) parental support and barriers, (7) value of friendship, and (8) influence of teammates. Friendships were key to both initiation and maintenance of participation, parents facilitated participation, and children with more active parents were more likely to participate in sport. Less is known on how family structure, sibling participation, extended family, and other theoretical frameworks may influence youth sport. The review suggests that social influences are important factors for ensuring participation, maximizing the quality of the experience, and capitalizing on the benefits of youth sport. Future research studies, programs, and policies promoting and developing evidence-based youth sporting experiences should consider social influences on youth sport participation.

Keywords: children, adolescents, peers, friends, parents, siblings, prevention

‘In general, children who participate in youth sport receive many benefits, including physical and psychosocial benefits, . . .’

Sport has been identified as 1 of the 7 best investments for promoting physical activity, which is particularly relevant for youth.1 A study of 38 countries worldwide found that approximately half of children participate in organized youth sport; however, this varies from country to country.2 It is estimated that the youth sport industry in the United States is worth $15 billion,3 further emphasizing its high profile in society. Importantly for health, youth sport is one of the key physical activity opportunities for youth,4,5 and contributes a significant proportion of their total physical activity.6 In general, children who participate in youth sport receive many benefits, including physical and psychosocial benefits, many related to participation in physical activity during sports. These include reduced risk of obesity, improved metabolic profiles, increased muscular strength,7 improved self-esteem, reduced risk of depression,8 and overall positive youth development,9 which is a prosocial approach to reaching positive outcomes for youths.9 However, both the physical and psychological benefits of sport are highly dependent on the quality of the specific sporting experience.8,10 Interestingly, some of the benefits may not be solely due to increased physical activity or energy expenditure, and there is some evidence that sport participation may be a greater contributor to mental health than overall physical activity.11 Children who participate in youth sport also report several other positive health behaviors such as improved diet, safer sexual practices, and decreased substance abuse.12

Since developing positive habits (eg, physical activity) in childhood can track into adulthood,13,14 it can be argued that there should be an emphasis on enjoyable lifelong activities that children can participate in.15-17 Youth sport participation can be regarded as a lifelong physical activity that can be safe and effective for providing myriad physical and psychosocial benefits for children when implemented with qualified instruction and appropriate supervision. Unfortunately, not all children participate in youth sports, and many of those who do participate have negative sporting experiences, which can lead to dropout—owing to injury, unsustainable expectations and demands, and/or burnout. According to the Sports and Fitness Industry Association, recent data from the United States suggest that overall participation in youth sports is dropping.18 Australian research has found that children begin dropping out of youth sport at the age of 8 years,19 which is similar to the age of physical activity decline recently reported in British children.20 A better understanding of these sporting experiences (or lack of sporting experience) will help increase participation, quality, and the benefits that children receive from youth sport.

Several factors influence youth sport participation. Using a socioecologic framework, it is proposed that factors from multiple levels influence access, quality, and outcomes.21 Historically, research on correlates of sports and physical activity in general in both adults and children have focused on intrapersonal factors, including demographic and biological, psychosocial, and behavioral variables.22 However, youth sport is a social experience and it is likely that interpersonal factors, which we will refer to as social factors throughout the article, play a large role. These social factors include family, friends, teachers or any other people who may influence an individual. One of the most obvious social agents is the coach. A growing body of research has explored factors related to coaches that influence youth sport experiences.23-25 But there are several other social agents that influence the youth sport experience including peers and families. Less is known on how these external social agents influence the youth sporting experience from access, quality of the experience, and the outcomes of participation. These social influences must be understood in order to increase youth sport participation and high-quality sporting experience for children to ultimately maximize the number of children receiving the physical and psychosocial benefits from a positive, evidence-based sporting experience.

Therefore, the purpose of this scoping review was to explore social influences on youth sport participation. More specifically, it explored how social agents, including peers, parents, and siblings, influence youth sport participation.

Methods

Study Design

The current study was guided by the methodological framework for scoping reviews proposed by Arksey and O’Malley26 and further defined by Levac et al.27 Scoping reviews allow a rapid and broad survey of existing literature. The authors proposed 6 stages to conduct a scoping review, including: (1) identifying a research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data, (5) collating, summarizing and reporting the results, and (6) consultation.26,27 The authors’ 6 stages guided the current study.

Stage 1: Identifying a Research Question

The research question for the current study was: how do social agents, including peers, parents, and siblings, influence youth sport participation? These social agents were later grouped into family and peers.

Stage 2: Identifying Relevant Studies

We searched 3 databases, including: PubMed, ERIC, and PsychInfo. Our PubMed search terms and strategy are detailed below. The same key words were used while searching the other 2 databases. The review included studies published prior to September 2017.

The following search terms were used to search the abstract and title: ((sport) AND (child* or youth)) AND (sibling* or brother* or sister* or parent or parents or mother or father or mom or dad or friend* or peer* or teammate*).

Stage 3: Study Selection

Included studies sampled youth from an organized youth sport setting. For the purposes of this study, organized youth sports (herein referred to as youth sport) was defined as an organized activity, formally arranged and governed by the rules of a given sport.28 Youth sport participants attended regular practices and games under supervision of one or more adults, who most often assume the role of team coach.28 For the current study, youth sport did not include sport occurring during school time (eg, school sport, physical education) or sport occurring outside of the typical formal setting (eg, summer camps, off-season training). Youth were defined as children and adolescents 18 years old and younger.

Studies must have explored a social agent’s influence on youth sport participation, specifically peers and family (i.e., parents and/or siblings). No limitations were set regarding study design, participants’ sex, or publication date. Excluded studies included: protocols papers, book reviews, commentaries, majority of participants were aged >18 years, limited to special populations (eg, children with disabilities), sport injury studies, studies that only addressed physical activity in general and not sports specifically, those limited to parent demographic variables such as family income or parent education, and those not written in the English language.

Stage 4: Charting the Data

Articles were then screened by title, abstract, and full text by the first author. Data were extracted from the articles independently by 2 reviewers, such as details about the population and study design (Supplemental Table A available in the online version of the article).

Stage 5: Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

To collate and summarize the data, the 3-step process method proposed by Levac et al27 was used and included analysis, reporting, and meaning. The analysis phase includes developing both numerical and qualitative summaries of the findings. The reporting phase includes the organization of these results into an end-product such as themes that may be a conceptual framework or table. In the third phase, the specific findings must be discussed within the broader context and consider implications to add validity to the findings.27

Stage 6: Consultation

Consultation was not performed at this stage, however the implications for key stakeholders is discussed.

Results

Study Selection

The initial search included 5291 titles after removing duplicates (4656 from PubMed, 967 from ERIC, 923 from PsychInfo). After screening by title, 431 articles remained. Abstracts were then screened and 252 full-text articles were reviewed for full text. A final sample of 111 full-text articles were included in the final review (See Supplemental Table A).

Study Characteristics

The majority of studies were cross-sectional (80 studies) with an additional 15 qualitative, 10 longitudinal studies, 4 reviews, 1 experimental, and 1 quasi-experimental. Most of the included studies were conducted in the United States (40 studies), Canada (13 studies), Australia (11 studies), and the United Kingdom (10 studies; 6 studies specified England). One study had multinational samples from the United States and the United Kingdom and 1 had participants from Australia and Canada.

Participant sample size ranged from 8 to 67,124 with a median of 231 participants. Of studies that included youth participants, 62 studies included adolescents (above primary grades), 19 included children only, and 18 included both children and adolescents. An additional 13 studies included adult participants (recalling childhood experiences) or were review articles. Most studies included both girls and boys (n = 96, 86%), with 12 studies including girls only and 3 studies including boys only. The majority of studies examined youth sport in general (n = 66, 59%) or a combination of sports (n = 15). The most common single sport researched was soccer (n = 9).

The articles represented 8 broad themes as shown in Table 1. These included reasons for/barriers to participation, social norms, achievement goal theory, family structure, sporting family, parent support, value of friendship, and influence of teammates.

Table 1.

Summary of Article Themes.

| Social Agent | Theme | No. of Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Family and peers | Reasons for/barriers to participation | 13 |

| Social norms | 8 | |

| Achievement motivation | 24 | |

| Family | Structure | 3 |

| Sporting family | 15 | |

| Parent support | 20 | |

| Peers | Friendships | 5 |

| Teammates | 11 | |

| Variable | Multiple | 6 |

Reasons for and Barriers to Participation in Youth Sport

Several studies, using surveys or qualitative interviews, indicated that the most common reasons children gave for participating in youth sports were because of friends or family (see Supplemental Table A). Five qualitative studies29-33 asked participants to describe reasons for sport participation. An Australian study of 9- to 12-year-old children reported family, siblings, and community reasons for joining soccer,29 which was echoed by a study of Canadian adolescents,31 but friendships were important for continued youth sport participation.29 Another study of adolescent soccer players in England found that family, particularly bringing the family together and connecting with family members was motivation for participating in youth sport.30 Additionally, involvement and engagement with others was a theme that emerged in a qualitative study that interviewed Swedish adolescents about their participant in youth sport.32 However, these results may be biased by interviews with children and adolescents who are participating in sport. Similarly, Coleman et al33 found that UK adolescents who participate in sports report friends as a reason for participating; however, those who do not participate in youth sports reported friends as a barrier because these participants perceived sport to take away from time to be social.

Quantitative surveys had inconsistent results regarding the role of family and peers for participating in sports. A study of boys aged 6 to 10 years in the United States found the top reasons for participating in sport to be feeling part of a team and being with and making new friends.34 However, a survey of Australian children and adolescents reported competition, skills, physical fitness, and liking a challenge as top reasons for participating.35 It is possible that there are cultural or racial differences in reasons for participation in youth sport, as found in one study,36 or differences in age groups. Basterfield et al37 found that physical barriers (eg, not having transportation) were more important for 9-year-olds in England, but social environmental factors (eg, friends and peer acceptance) were more important for 12-year-olds. Other evidence suggests gender differences may account for some differences in participation and factors related to it with girls having greater social influences.38 A survey of French adolescents found that boys reported having a friend in sport as a reason for participating, while girls more specifically participated for encouragement and support from parents, siblings, and friends.39 An additional parental barrier to participating included a fear of injury.40,41

Social Norms

Seven cross-sectional and qualitative studies addressed social norms,42-48 displayed by family and peers, as they are associated with youth sports. These mainly included perceptions of gender and popularity. Several older studies examined what characteristics high school students’ value for popularity. While one study found athletes were most popular,43 another found that high schoolers would prefer to be remembered for being smart as opposed to an athlete.45 Unsurprisingly, youth perceptions of popularity were highly influenced by gender, not only of the participant, but also the sport in which they participate. One study found male athletes were considered more popular and boys valued sports for popularity.43 Furthermore, females in stereotypical “feminine” sports (eg, ballet) were given higher status as rated by their peers compared to those in stereotypical “masculine” sports (eg, karate, basketball).42,46 These gendered perspectives existed among family members as well as peers. Two studies examined family gender stereotyping from parents and sibling order, with boys more likely to have sport or “masculine” toys from early ages.47,48 While the majority of this research was conducted prior to 2000, a more recent Serbian study using social network methods found that those who participate in sport have higher sociometric status as rated by their peers.44

Achievement Goal Theory

Twenty-four studies were based on achievement goal theory and included studies of motivational climates and goal orientations (See Supplemental Table A). Twenty-one of these studies were cross-sectional, with only 2 longitudinal49,50 and 1 qualitative.51 Both peer and parent motivational climates, or the psychological environment that is created in a situation, were researched. The motivational climate includes the goals (eg, social, winning) of the social agents (eg, coach, parent) which are emphasized in the environment. The majority of these studies examined associations between task or ego climates and youth outcomes such as motivation or maintenance. One study of US soccer players found parent goal orientations were associated with child orientations.52 Task-oriented peer and/or parent climates in sports have been associated with flow,53 intrinsic motivation and persistence in sport,54-57 and positive self-worth and enjoyment.58 Studies also found that combinations of individual traits, such as perfectionism and stress combined with particular climates and orientations were associated with negative outcomes such as burnout59,60 and unsportspersonlike play.61

Family-Specific Themes

Family Structure

Three cross-sectional studies examined family structure only,62-64 not whether family members participated in sports, but how many parents were in the household and sibling orders. Family structure, particularly parents, was associated with youth sports participation. In 1 large Canadian study of more than 20,000 children and adolescents62 and 1 smaller study of 381 adolescents from the United Kingdom,63 children from single-parent families were less likely to participate in youth sports. Only 1 study examined the effect of sibling order on sports participation and found no relationship.64

Sporting Family

Fifteen studies examined the associations between family members’ participation in sport and a child’s participation in sports (see Supplemental Table A). Two of these included qualitative information65,66 and 2 were reviews,67,68 with the remaining cross-sectional studies. This has been both examinations of associations between family members’ sporting behaviors as well as possible genetic contributions. Three studies have discussed a potential genetic basis of shared of sports participation with 2 being reviews, concluding limited evidence for a genetic influence.67,68 The 1 cross-sectional study was conducted in the Netherlands and found relationships in sports behavior between parents, and between female twins, but not between parents and offspring.69 Other studies have consistently found that children with parents who participate in sport, or are active, are more likely to participate in sports.65,70-74 With regard to siblings specifically, one study found that both sibling participation in elite or nonelite sports and the interaction with sibling order related to a child’s sport participation.75 For example, children with an older sibling who participated in the same sport were more likely to be elite athletes.

Parent and Family Support

Twenty studies researched how parents provide support for children in youth sport as well as potential barriers that they may face to providing that support. Again, the majority were cross-sectional studies; however, 7 were qualitative,76-82 1 was longitudinal,83 and 1 was a review article.84 Parents play several roles for youth in a sport setting, including being supporters (eg, cheering from the sideline), coaching, managing (eg, fundraising). and being providers (eg, providing transportation).80 The majority of studies described parental support as an important facilitator for participation.77,82,84,85 While multiple studies describe the importance of financial support,78,79 and often financial toll, parents provide other forms of support including tangible, esteem, information, emotion and network support.81 Parental modeling of sport, while associated with higher rates of child participation, may not be as critical for sports participation as other forms of support.86,87 On the other side, children who receive negative parental support, such as pressure to excel88,89 or hostility,90 may result in a negative experience for children in sport. Some barriers parents experience in providing support include cost, time, and work.76,91

Peer-Specific Themes

Value of Friendship

Four cross-sectional studies92-95 and 1 cross-sectional and longitudinal study96 examined friendship in sports. Generally, youth have friends who participate in sport with them95 and friendships in sport may predict sporting commitment.94 However, the reverse may not be true. Participating in sport together was not critical for friendship. Socializing and school were more important for maintaining friendship compared to participating in sports together as ranked by fourth and eighth graders in the United States.93 Bigelow et al92 found that friendships were also resilient to sporting context, meaning that if a child has a friend on another team, they can still maintain that friendship. In the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health in the United States, a social network analysis of more than 67 000 adolescents found that children are more likely to be friends if they participate in sport together and in a longitudinal follow-up of a subsample of 2550 participants, those who participate in sport together are more likely to be friends 8 months later.96

Influence of Teammates

More specifically than peers and friends, 11 studies described factors related to teammates that influenced behaviors, both prosocial and antisocial behaviors. These included 5 cross-sectional studies,97-101 2 qualitative studies,102,103 2 longitudinal studies,104,105 1 quasi-experimental study,106 and 1 experimental study.107 Being involved in youth sport itself may lead to improved prosocial behaviors.102,105-107 The antisocial behaviors studied included bullying, aggression, and unsportspersonlike conduct. Sporting context,97 team norms,101 and self-efficacy98 have been associated with antisocial behaviors. Baar and Wubbels97 conducted a survey of more than 1400 10- to 12-year-olds in the Netherlands and found that sports clubs had higher levels of aggression than school sports and that this may result from different prosocial and Machiavellian resource control strategies in different sporting contexts. A study of ice hockey players in Canada, found that teammates who perpetrated antisocial behaviors saw their behavior as justified and acceptable, while positive teammate behaviors influenced social identity of the team.102 Group cohesion104 and positive group membership105 may be beneficial for team outcomes and weaker social connections have been associated with bullying.99 The 1 experimental study found in this review, compared a coach-led soccer environment with a peer-led soccer environment, and found that those in the peer-led group had higher prosocial behaviors and communication.107

Cross-Themes

Six studies included multiple themes of those described above.108-113 Two qualitative studies conducted with Australian adolescents examined reasons for participating, including participate to advance education, barriers to participation, including lack of parent provided transportation, how having active family members promoted sport, enjoyment of participating with friends, and influences from peer social norms.108,109 The other studies were cross-sectional surveys and examined how both parents and peers interest were higher in athletes compared with nonatheltes,111 how strong parent support may counteract peer negative support,112 how parent and peer support is associated with self-esteem110 and important for fun in sport.113

Discussion

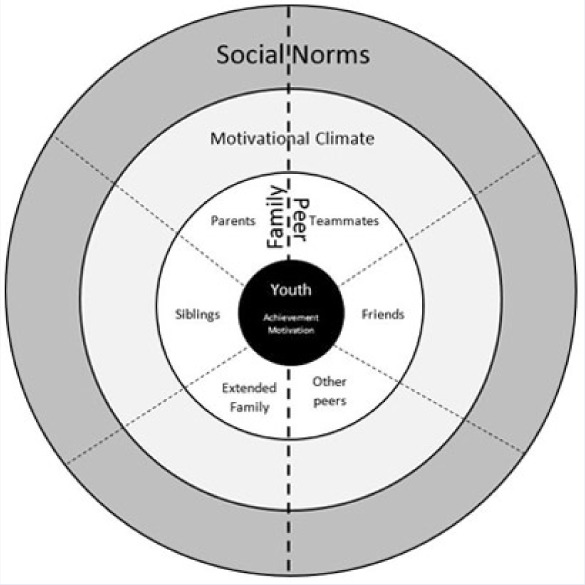

This scoping review identified 8 main themes of existing research related to social influences on youth sport, not including coaches. These themes are not exclusive or comprehensive to all the potential themes of social influences on youth sport, but a summary of the major research themes in existing literature. The social agents include parents, siblings, extended family, friends, teammates, other peers, as shown in Figure 1. While this represents an oversimplified view of the complex and nuanced relationships influencing youth sport, it is a current summary of the broad themes existing in the literature. These social agents have been shown to influence motivational climates that interact with goal orientations. All these social influences exist within a system of social norms.

Figure 1.

Sporting Social, a description of themes resulting from a scoping review of the social influences on youth sport.

Friends were consistently reported as a predominant reason given by children and adolescents for participating in sports. Thus, to increase and sustain participation, it is important to involve the friendship network. It is likely that friendship importance and quality differ by gender and ages and may be differentially associated with sport motivation.114 Future interventions may target friend groups to all participate in a sport as opposed to including individual children or adolescents. Family, including siblings and parents were also given as reasons for participating. Similarly, families should be included in the sporting experience. While sport is not suggested to be important for maintaining existing friendships, continuing sport may be highly dependent on whether youth have a friend participating with them. This may have implications for how teams are created, for example, keeping friends together on the same team instead of randomly selecting teams. This may also help in minimizing parent barriers. However, friendships may also result from being on teams, and coaches should facilitate these friendships to maintain sports participation and positive benefits of sport.

In addition to coaches, teammates have a large influence on the sporting experience, which can be both positive and negative. More effort is needed to ensure that this is a positive experience that encourages prosocial behaviors using systematic evaluation and valid interventions.115 For example, in addition to teaching skills and sport-specific team strategies, a good youth sport experience will also implicitly and potentially explicitly teach good social skills similar to other quality after-school programs.116

Few studies examined family structure in specific relation to sports’ participation. A single-parent home may be associated with fewer time and financial resources which are cited as key barriers for parental support.76,91 While there was limited research on siblings and sport, there has been more research on sibling concordance of broader health behaviors, including physical activity,117 and associated health outcomes such as obesity.118 It is possible that total number of siblings, and not birth order may be more important, which may be indicative of family socioeconomics or differences in parenting strategies118; however, birth order has shown to be associated with other types of achievement such as educational attainment119 and related skills such as cooperation.120 While family structure is not an easily modifiable factor, it may help to target resources toward youth in particular family situations who are less likely to gain the benefits from sports.

Not only may family structure influence sporting participation, but the sport behaviors of those family members have shown to be associated with youth sport participation. While several studies examined cross-sectional associations between sporting or activity habits of parents being positively associated with sport participation in children, this scoping review identified few articles on the effects of siblings’ sports participation on sports participation. A study of elite athletes found interesting and complex relationships between birth order and level of sport.75 Their study of Australian and Canadian elite athletes found that elite athletes were less likely to be first-born and more likely to have older siblings who participated in recreational sports. This suggests that there may be unique parenting or a transfer of skills or motivation that may encourage younger siblings who have older siblings involved in sports, though not at an elite level, to become elite athletes. For example, research has shown that eldest children receive more psychological support than youngest children.121 Similar to friends, if siblings play a large role in promoting youth sports participation, sports programs and interventions may aim to involve siblings in the sport experience. It is likely that the effect of siblings on sports participation is complex and an understanding of sibling order, gender, personality types, relationships, and sporting context are likely to influence sporting participation.

It is consistent that parents are an important supporter of youth sports participation, which is consistent with broader physical activity.122 Parents need to be included when targeting participation and barriers to parent support, particularly time and money should be addressed. However, it is interesting to note that financial support, while a major form of parent support for youth sport participation, is not the only type of support that may be beneficial for participation.81 Parents should be made aware of the multiple forms of support, beyond financial support, that they can provide for their children. Less is known on the influence of extended family. One study addressed how the influence of nuclear vs extended family on sporting behavior may differ by socioeconomic status.66 When parental barriers are high due to limited resources, extended family may be a key social agent. Different cultures may have differing functional123 involvements levels of extended family members that may also need to be included in the sporting experience.

Multiple social agents, parents, teammates, and peers, have been researched in the context of achievement goal theory. Achievement goal theory has been the dominant theoretical framework for understanding the influence of family and peers on youth sport experiences, and examining motivation in educational research in general.124 While much of the research has taken a simplistic approach to achievement motivation goals and orientations, a more complex understanding is need to better understand youth sport behavior and outcomes.124 Most research seems to suggest that for the majority of participants, a task parent and peer climate are most conducive to positive sporting experiences. Therefore, youth sport experiences that encourage task-oriented climates should be promoted. Other theoretical frameworks should also be explored. In taking a broader social network approach, theories, and methods from social network analysis such as social capital theory or rational choice theory may be considered.125 For example, instead of limiting analyses to a single social agent (ie, parents), social network analysis may examine multiple social agents and then connections between these agents. When examining a peer network, some peers may hold more influential status or complex connections between peers may be critical to influencing participation.

Finally, broader social norms have shown to influence these social relationships in the context of youth sport participation. Athletic or sport status was not as highly valued among high schoolers as expected.43,45 However, these studies were conducted in 1976 and 1994. The role of sports in society continues to evolve with a seemingly greater impact at all levels. Since the publications of those studies, sport has been increasingly specialized, commodified, and an increased presence in media.126 Even the way that individuals interact with the media has dramatically changed, with digital communication and social networking making sports easily accessible and “telepresent.”127 Sports media has shown to influence social norm perceptions. Current studies may find that the current form of sports, both professionally and recreationally, and how that is communicated and perceived in society has changed.

The role of gender stereotypes may have also changed in recent times; however, some evidence suggests that gender stereotypes are still present and may be strengthened.128 These gender norms may be reinforced as children get older with girls less likely to join sport at older ages and some boys joining during adolescence.19 Recently, adolescents have tended to rate masculine activities as more masculine, feminine activities as more feminine, and neutral activities as more masculine than did adults; though the role of gender stereotypes can change.129 There are still different social pressures and inequalities for girls participating in sports compared to boys. The way we consider gender in sport has changed and there is a growing appreciation of the intersectionality of race, cultures, and gender.130 More qualitative and longitudinal studies on how these social norms influence participation over time are needed. Especially during the transition from childhood to adolescence, as it is likely that these peer and family influences change during these different life stages. Research on physical activity in general suggests that the influence of family changes to a greater influence from peers.131

Overall, existing literature suggests an important role of family and peers on youth sport participation. However, the bulk of literature is limited by single cross-sectional survey study designs. This is an appropriate study design for many of the research questions such as how the structure of the family is associated with child sport participation. However, more longitudinal studies are needed to track participation over time and factors that may influence maintenance of dropping out of youth sports. Furthermore, experimental studies, intervening within social networks, such as with siblings or friends, may be a key method of increasing youth sport participation. However, change at the population level will not be affected without widespread implementation and dissemination of the findings from these longitudinal and experimental studies. Currently, there is a lack of implementation and dissemination research related to sports participation. This current scoping review was limited in depth to include a breadth of studies, while also including some indicators of study quality. Future systematic reviews may include more depth of studies as they relate to a single social agent such as parents or teammates. However, this is a first preliminary step in assessing the evidence for a role of social influences on youth sport participation and how these multiple influences may interrelate (Figure 1).

Conclusion

Social influences are important factors for ensuring participation, maximizing the quality of the experience, and capitalizing on the benefits of youth sport. Social factors appear to critically influence youth sport participation. Thus, future research, programs and policies hoping to increase participation and ensure high quality sport experiences, need to better understand the nuanced social relationships and address the many social agents influencing youth sport.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Grady Finley and Torey Walter for their help in collecting and extracting articles.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Informed Consent: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Trial Registration: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any clinical trials.

Supplemental Material: The online supplemental material is available at http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/suppl/10.1177/1559827618754842.

References

- 1. Global Advocacy for Physical Activity (GAPA) the Advocacy Council of the International Society for Physical Activity and Health (ISPAH). NCD prevention: investments that work for physical activity. Health Promot. 2010;17(2):5-15. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tremblay MS, Barnes JD, Gonzalez SA, et al. ; Global Matrix 2.0 Research Team. Global Matrix 2.0: report card grades on the physical activity of children and youth comparing 38 countries. J Phys Act Health. 2016;13(11 suppl 2):S343-S366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gregory S. How kids’ sports became a $15 billion industry. TIME. http://time.com/4913687/how-kids-sports-became-15-billion-industry/. Published August 24, 2017. Accessed January 8, 2018.

- 4. Mandic S, Bengoechea EG, Stevens E, de la Barra SL, Skidmore P. Getting kids active by participating in sport and doing it more often: focusing on what matters. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bergeron MF. Improving health through youth sports: is participation enough? New Dir Youth Dev. 2007;(115):27-41,6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wickel EE, Eisenmann JC. Contribution of youth sport to total daily physical activity among 6-to 12-yr-old boys. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39:1493-1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Janssen I, LeBlanc AG. Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Eime RM, Young JA, Harvey JT, Charity MJ, Payne WR. A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for children and adolescents: informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fraser-Thomas JL, Côté J, Deakin J. Youth sport programs: an avenue to foster positive youth development. Phys Educ Sport Pedagogy. 2005;10:19-40. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Guagliano JM, Rosenkranz RR, Kolt GS. Girls’ physical activity levels during organized sports in Australia. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45:116-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Marlier M, Van Dyck D, Cardon G, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Babiak K, Willem A. Interrelation of sport participation, physical activity, social capital and mental health in disadvantaged communities: a SEM analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0140196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Taliaferro LA, Rienzo BA, Donovan KA. Relationships between youth sport participation and selected health risk behaviors from 1999 to 2007. J Sch Health. 2010;80:399-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Van der Horst K, Paw MJCA, Twisk JW, Van Mechelen W. A brief review on correlates of physical activity and sedentariness in youth. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39:1241-1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. DeBate RD, Gabriel PK, Zwald M, Huberty J, Zhang Y. Changes in psychosocial factors and physical activity frequency among third-to eighth-grade girls who participated in a developmentally focused youth sport program: a preliminary study. J Sch Health. 2009;79:474-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Biddle SJH, Atkin AJ, Cavill N, Foster C. Correlates of physical activity in youth: a review of quantitative systematic reviews. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol. 2011;4:25-49. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lubans DR, Morgan PJ, Cliff DP, Barnett LM, Okely AD. Fundamental movement skills in children and adolescents: review of associated health benefits. Sports Med. 2010;40:1019-1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Faigenbaum AD, Lloyd RS, Myer GD. Youth resistance training: past practices, new perspectives, and future directions. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2013;25:591-604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bogage J. Youth sports study: declining participation, rising costs and unqualified coaches. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/recruiting-insider/wp/2017/09/06/youth-sports-study-declining-participation-rising-costs-and-unqualified-coaches/?utm_term=.b0138572cc35. Published September 6, 2017. Accessed January 8, 2018.

- 19. Howie EK, McVeigh JA, Smith AJ, Straker LM. Organized sport trajectories from childhood to adolescence and health associations. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48:1331-1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Farooq MA, Parkinson KN, Adamson AJ, et al. Timing of the decline in physical activity in childhood and adolescence: Gateshead millennium cohort study [published online March 13, 2017]. Br J Sports Med. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sallis JF, Cervero RB, Ascher W, Henderson KA, Kraft MK, Kerr J. An ecological approach to creating active living communities. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:297-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bauman AE, Reis RS, Sallis JF, Wells JC, Loos RJ, Martin BW; Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group. Correlates of physical activity: why are some people physically active and others not? Lancet. 2012;380:258-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Smith N, Quested E, Appleton PR, Duda JL. Observing the coach-created motivational environment across training and competition in youth sport. J Sports Sci. 2017;35:149-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schlechter CR, Rosenkranz RR, Milliken GA, Dzewaltowski DA. Physical activity levels during youth sport practice: does coach training or experience have an influence? J Sports Sci. 2017;35:22-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Guagliano JM, Lonsdale C, Rosenkranz RR, Kolt GS, George ES. Do coaches perceive themselves as influential on physical activity for girls in organised youth sport? PLoS One. 2014;9:e105960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19-32. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Janssen I. Active play: an important physical activity strategy in the fight against childhood obesity. Can J Public Health. 2014;105:e22-e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Light R, Curry C. Children’s reasons for joining sport clubs and staying in them: a case study of a Sydney soccer club. ACHPER Healthy Lifestyles J. 2009;56:23-27. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Clarke NJ, Harwood CG, Cushion CJ. A phenomenological interpretation of the parent-child relationship in elite youth football. Sport Exerc Perform Psychol. 2016;5:125-143. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gavin J, McBrearty M, Malo K, Abravanel M, Moudrakovski T. Adolescents’ perception of the psychosocial factors affecting sustained engagement in sports and physical activity. Int J Exerc Sci. 2016;9:384-411. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jakobsson BT. What makes teenagers continue? A salutogenic approach to understanding youth participation in Swedish club sports. Phys Educ Sport Pedagogy. 2014;19:239-252. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Coleman L, Cox L, Roker D. Girls and young women’s participation in physical activity: psychological and social influences. Health Educ Res. 2008;23:633-647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stern HP, Bradley RH, Prince MT, Stroh SE. Young children in recreational sports. Participation motivation. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1990;29:89-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Longhurst K, Spink KS. Participation motivation of Australian children involved in organized sport. Can J Sport Sci. 1987;12:24-30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Duncan SC, Strycker LA, Chaumeton NR. Personal, family, and peer correlates of general and sport physical activity among African American, Latino, and white girls. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2015;8:12-28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Basterfield L, Gardner L, Reilly JK, et al. Can’t play, won’t play: longitudinal changes in perceived barriers to participation in sports clubs across the child-adolescent transition. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2016;2:e000079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Keresztes N, Piko BF, Pluhar ZF, Page RM. Social influences in sports activity among adolescents. J R Soc Promot Health. 2008;128:21-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Deflandre A, Lorant J, Gavarry O, Falgairette G. Physical activity and sport involvement in French high school students. Percept Mot Skills. 2001;92:107-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Boufous S, Finch C, Bauman A. Parental safety concerns—a barrier to sport and physical activity in children? Aust N Z J Public Health. 2004;28:482-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bean CN, Fortier M, Post C, Chima K. Understanding how organized youth sport maybe harming individual players within the family unit: a literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:10226-10268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Alley TR, Hicks CM. Peer attitudes towards adolescent participants in male- and female-oriented sports. Adolescence. 2005;40:273-280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Buchanan HT, Blankenbaker J, Cotten D. Academic and athletic ability as popularity factors in elementary school children. Res Q. 1976;47:320-325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gadzic A, Vuckovic I. Participation in sports and sociometric status of adolescents. Biomedical Human Kinetics. 2009;1:83-85. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Holland A, Andre T. Athletic participation and the social status of adolescent males and females. Youth Soc. 1994;25:388-407. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kane MJ. The female athletic role as a status determinant within the social systems of high school adolescents. Adolescence. 1988;23:253-264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. McHale SM, Crouter AC, Tucker CJ. Family context and gender role socialization in middle childhood: comparing girls to boys and sisters to brothers. Child Dev. 1999;70:990-1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nash A, Fraleigh K. The influence of older siblings on the sex-typed toy play of young children. Paper presented at: Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; March 24-28, 1993; New Orleans, LA. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kipp LE, Weiss MR. Social predictors of psychological need satisfaction and well-being among female adolescent gymnasts: a longitudinal analysis. Sport Exerc Perform Psychol. 2015;4:153-169. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Joesaar H, Hein V, Hagger MS. Youth athletes’ perception of autonomy support from the coach, peer motivational climate and intrinsic motivation in sport setting: one-year effects. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2012;13:257-262. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Vazou S, Ntoumanis N, Duda JL. Peer motivational climate in youth sport: a qualitative inquiry. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2005;6:497-516. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ebbeck V, Becker SL. Psychosocial predictors of goal orientations in youth soccer. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1994;65:355-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Caglar E, Aşçi FH, Uygurtaş M. Roles of perceived motivational climates created by coach, peer, and parent on dispositional flow in young athletes. Percept Mot Skills. 2017;124:462-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Joesaar H, Hein V, Hagger MS. Peer influence on young athletes’ need satisfaction, intrinsic motivation and persistence in sport: a 12-month prospective study. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2011;12:500-508. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Le Bars H, Gernigon C, Ninot G. Personal and contextual determinants of elite young athletes’ persistence or dropping out over time. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2009;19:274-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sánchez-Miguel PA, Leo FM, Sánchez-Oliva D, Amádo D, Garcia-Calvo T. The importance of parents’ behavior in their children’s enjoyment and amotivation in sports. J Hum Kinet. 2013;36:169-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Stuntz CP, Weiss MR. Achievement goal orientations and motivational outcomes in youth sport: the role of social orientations. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2009;10:255-262. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Vazou S, Ntoumanis N, Duda JL. Predicting young athletes’ motivational indices as a function of their perceptions of the coach- and peer-created climate. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2006;7:215-233. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Smith AL, Gustafsson H, Hassmen P. Peer motivational climate and burnout perceptions of adolescent athletes. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2010;11:453-460. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gustafsson H, Hill AP, Stenling A, Wagnsson S. Profiles of perfectionism, parental climate, and burnout among competitive junior athletes. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2016;26:1256-1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Stuntz CP, Weiss MR. Influence of social goal orientations and peers on unsportsmanlike play. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2003;74:421-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. McMillan R, McIsaac M, Janssen I. Family structure as a correlate of organized sport participation among youth. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0147403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Quarmby T, Dagkas S, Bridge M. Associations between children’s physical activities, sedentary behaviours and family structure: a sequential mixed methods approach. Health Educ Res. 2011;26:63-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Landers DM. Sibling-sex-status and ordinal position effects on females’ sport participation and interests. J Soc Psychol. 1970:80;247-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sanz-Arazuri E, Ponce-de-Leon-Elizondo A, Valdemoros-San-Emeterio MA. Parental predictors of physical inactivity in Spanish adolescents. J Sports Sci Med. 2012;11:95-101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Stuij M. Habitus and social class: a case study on socialisation into sports and exercise. Sport Educ Soc. 2015;20:780-798. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Beunen G, Thomis M. Genetic determinants of sports participation and daily physical activity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23(suppl 3):S55-S63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Camporesi S, McNamee MJ. Ethics, genetic testing, and athletic talent: children’s best interests, and the right to an open (athletic) future. Physiol Genomics. 2016;48:191-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Boomsma DI, van den Bree MB, Orlebeke JF, Molenaar PC. Resemblances of parents and twins in sports participation and heart rate. Behav Genet. 1989;19:123-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Deflandre A, Lorant J, Gavarry O, Falgairette G. Determinants of physical activity and physical and sports activities in French school children. Percept Mot Skills. 2001;92:399-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Dollman J. Changing associations of Australian parents’ physical activity with their children’s sport participation: 1985 to 2004. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2010;34:578-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kobel S, Kettner S, Kesztyus D, Erkelenz N, Drenowatz C, Steinacker JM. Correlates of habitual physical activity and organized sports in German primary school children. Public Health. 2015;129:237-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Sukys S, Majauskiene D, Cesnaitiene VJ, Karanauskiene D. Do parents’ exercise habits predict 13–18-year-old adolescents’ involvement in sport? J Sports Sci Med. 2014;13:522-528. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Toftegaard-Stockel J, Nielsen GA, Ibsen B, Andersen LB. Parental, socio and cultural factors associated with adolescents’ sports participation in four Danish municipalities. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2011;21:606-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Hopwood MJ, Farrow D, MacMahon C, Baker J. Sibling dynamics and sport expertise. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015;25:724-733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Bassett-Gunter R, Rhodes R, Sweet S, Tristani L, Soltani Y. Parent support for children’s physical activity: a qualitative investigation of barriers and strategies. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2017;88:282-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Baxter-Jones AD, Maffulli N. Parental influence on sport participation in elite young athletes. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2003;43:250-255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Hosseini SV, Anoosheh M, Abbaszadeh A, Ehsani M. Qualitative Iranian study of parents’ roles in adolescent girls’ physical activity habit development. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15:207-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Kirk D, Carlson T, O’Connor A, Burke P, Davis K, Glover S. The economic impact on families of children’s participation in junior sport. Aust J Sci Med Sport. 1997;29:27-33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Knight CJ, Dorsch TE, Osai KV, Haderlie KL, Sellars PA. Influences on parental involvement in youth sport. Sport Exerc Perform Psychol. 2016;5:161-178. [Google Scholar]

- 81. Park S, Kim S. Parents’ perspectives and young athletes’ perceptions of social support. J Exerc Rehabil. 2014;10:118-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Zahra J, Sebire SJ, Jago R. “He’s probably more mr. Sport than me”—a qualitative exploration of mothers’ perceptions of fathers’ role in their children’s physical activity. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15:101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Brophy S, Cooksey R, Lyons RA, Thomas NE, Rodgers SE, Gravenor MB. Parental factors associated with walking to school and participation in organised activities at age 5: analysis of the millennium cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Hellstedt J. Invisible players: a family systems model. Clin Sports Med. 2005;24:899-928,x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Gould D, Lauer L, Rolo C, Jannes C, Pennisi N. Understanding the role parents play in tennis success: a national survey of junior tennis coaches. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40:632-636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Power TG, Woolger C. Parenting practices and age-group swimming: a correlational study. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1994;65:59-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Erkelenz N, Kobel S, Kettner S, Drenowatz C, Steinacker JM. Parental activity as influence on children’s BMI percentiles and physical activity. J Sports Sci Med. 2014;13:645-650. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Ommundsen Y, Roberts GC, Lemyre PN, Miller BW. Parental and coach support or pressure on psychosocial outcomes of pediatric athletes in soccer. Clin J Sport Med. 2006;16:522-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Amado D, Sánchez-Oliva D, González-Ponce I, Pulido-González JJ, Sánchez-Miguel PA. Incidence of parental support and pressure on their children’s motivational processes towards sport practice regarding gender. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Hennessy DA, Schwartz S. Personal predictors of spectator aggression at little league baseball games. Violence Vict. 2007;22:205-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Berntsson LT, Ringsberg KC. Swedish parents’ activities together with their children and children’s health: a study of children aged 2-17 years. Scand J Public Health. 2014;42(15 suppl):41-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Bigelow BJ, Lewko JH, Salhani L. Sport-involved children’s friendship expectations. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 1989;11:152-160. [Google Scholar]

- 93. Mathur R, Berndt TJ. Relations of friends’ activities to friendship quality. J Early Adolesc. 2006;26:365-388. [Google Scholar]

- 94. McDonough MH, Crocker PR. Sport participation motivation in young adolescent girls: the role of friendship quality and self-concept. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2005;76:456-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Poulin F, Denault A-S. Friendships with co-participants in organized activities: prevalence, quality, friends’ characteristics, and associations with adolescents’ adjustment. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev. 2013:19-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Schaefer DR, Simpkins SD, Vest AE, Price CD. The contribution of extracurricular activities to adolescent friendships: new insights through social network analysis. Dev Psychol. 2011;47:1141-1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Baar P, Wubbels T. Machiavellianism in children in Dutch elementary schools and sports clubs: prevalence and stability according to context, sport type, and gender. Sport Psychol. 2011;25:444-464. [Google Scholar]

- 98. Ciairano S, Gemelli F, Molinengo G, Musella G, Rabaglietti E, Roggero A. Sport, stress, self-efficacy and aggression towards peers: unravelling the role of the coach. Cogn Brain Behav. 2007;11:175-194. [Google Scholar]

- 99. Evans B, Adler A, Macdonald D, Côté J. Bullying victimization and perpetration among adolescent sport teammates. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2016;28:296-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Jackson B, Gucciardi DF, Lonsdale C, Whipp PR, Dimmock JA. “I think they believe in me:” the predictive effects of teammate- and classmate-focused relation-inferred self-efficacy in sport and physical activity settings. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2014;36:486-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Shields DL, LaVoi NM, Bredemeier BL, Power FC. Predictors of poor sportspersonship in youth sports: personal attitudes and social influences. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2007;29:747-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Bruner MW, Boardley ID, Allan V, et al. Examining social identity and intrateam moral behaviours in competitive youth ice hockey using stimulated recall. J Sports Sci. 2017;35:1963-1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Guest AM. Reconsidering teamwork: popular and local meanings for a common ideal associated with positive youth development. Youth Soc. 2008;39:340-361. [Google Scholar]

- 104. Bosselut G, McLaren CD, Eys MA, Heuzé JP. Reciprocity of the relationship between role ambiguity and group cohesion in youth interdependent sport. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2012;13:341-348. [Google Scholar]

- 105. Bruner MW, Boardley ID, Côté J. Social identity and prosocial and antisocial behavior in youth sport. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2014;15:56-64. [Google Scholar]

- 106. Nathan S, Kemp L, Bunde-Birouste A, MacKenzie J, Evers C, Shwe TA. “We wouldn’t of made friends if we didn’t come to Football United”: the impacts of a football program on young people’s peer, prosocial and cross-cultural relationships. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:399-415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Imtiaz F, Hancock DJ, Côté J. Examining young recreational male soccer players’ experience in adult-and peer-led structures. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2016;87:295-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Casey MM, Eime RM, Payne WR, Harvey JT. Using a socioecological approach to examine participation in sport and physical activity among rural adolescent girls. Qual Health Res. 2009;19:881-893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Eime RM, Payne WR, Casey MM, Harvey JT. Transition in participation in sport and unstructured physical activity for rural living adolescent girls. Health Educ Res. 2010;25:282-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Hines S, Groves DL. Sports competition and its influence on self-esteem development. Adolescence. 1989;24:861-869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Snyder EE, Spreitzer EA. Correlates of sport participation among adolescent girls. Res Q. 1976;47:804-809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. te Velde SJ, Chin AMJ, De Bourdeaudhuij I, et al. Parents and friends both matter: simultaneous and interactive influences of parents and friends on European schoolchildren’s energy balance-related behaviours—the ENERGY cross-sectional study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11:82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Visek AJ, Achrati SM, Mannix H, McDonnell K, Harris BS, DiPietro L. The fun integration theory: toward sustaining children and adolescents sport participation. J Phys Act Health. 2015;12:424-433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Weiss MR, Smith AL. Friendship quality in youth sport: relationship to age, gender, and motivation variables. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2001;23:420-437. [Google Scholar]

- 115. Gould D, Carson S. Life skills development through sport: current status and future directions. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol. 2008;1:58-78. [Google Scholar]

- 116. Durlak JA, Weissberg RP, Pachan M. A meta-analysis of after-school programs that seek to promote personal and social skills in children and adolescents. Am J Community Psychol. 2010;45:294-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Daw J, Margolis R, Verdery AM. Siblings, friends, course-mates, club-mates: how adolescent health behavior homophily varies by race, class, gender, and health status. Soc Sci Med. 2015;125:32-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. de Oliveira FM, Assunçã MC, Schäfer AA, et al. The influence of birth order and number of siblings on adolescent body composition: evidence from a Brazilian birth cohort study. Br J Nutr. 2015;114:118-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Travis R, Kohli V. The birth order factor: ordinal position, social strata, and educational achievement. J Soc Psychol. 1995;135:499-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Prime H, Plamondon A, Jenkins JM. Birth order and preschool children’s cooperative abilities: a within-family analysis. Br J Dev Psychol. 2017;35:392-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Terada T, Kasai M, Asano K. Psychological support for junior high school students: sibling order and sex. Psychol Rep. 2006;99:179-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Trost SG, Sallis JF, Pate RR, Freedson PS, Taylor WC, Dowda M. Evaluating a model of parental influence on youth physical activity. Am J Prev Med. 2003;25:277-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Georgas J, Mylonas K, Bafiti T, et al. Functional relationships in the nuclear and extended family: a 16-culture study. Int J Psychol. 2001;36:289-300. [Google Scholar]

- 124. Senko C, Hulleman CS, Harackiewicz JM. Achievement goal theory at the crossroads: old controversies, current challenges, and new directions. Educ Psychol. 2011;46:26-47. [Google Scholar]

- 125. Scott J. Social Network Analysis. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 126. Horne J, Tomlinson A, Whannel G, Woodward K. Understanding Sport: A Socio-Cultural Analysis. London, England: Routledge; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 127. Hutchins B. The acceleration of media sport culture: Twitter, telepresence, and online messaging. Inform Commun Soc. 2011;14:237-257. [Google Scholar]

- 128. Chalabaev A, Sarrazin P, Fontayne P, Boiché J, Clément-Guillotin C. The influence of sex stereotypes and gender roles on participation and performance in sport and exercise: review and future directions. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2013;14:136-144. [Google Scholar]

- 129. Plaza M, Boiché J, Brunel L, Ruchaud F. Sport = male . . . but not all sports: investigating the gender stereotypes of sport activities at the explicit and implicit levels. Sex Roles. 2017;76:202-217. [Google Scholar]

- 130. Abdel-Shehid G, Kalman-Lamb N. Complicating gender, sport, and social inclusion: the case for intersectionality. Soc Inclusion. 2017;5:159-162. [Google Scholar]

- 131. Chan DK, Lonsdale C, Fung HH. Influences of coaches, parents, and peers on the motivational patterns of child and adolescent athletes. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2012;22:558-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.