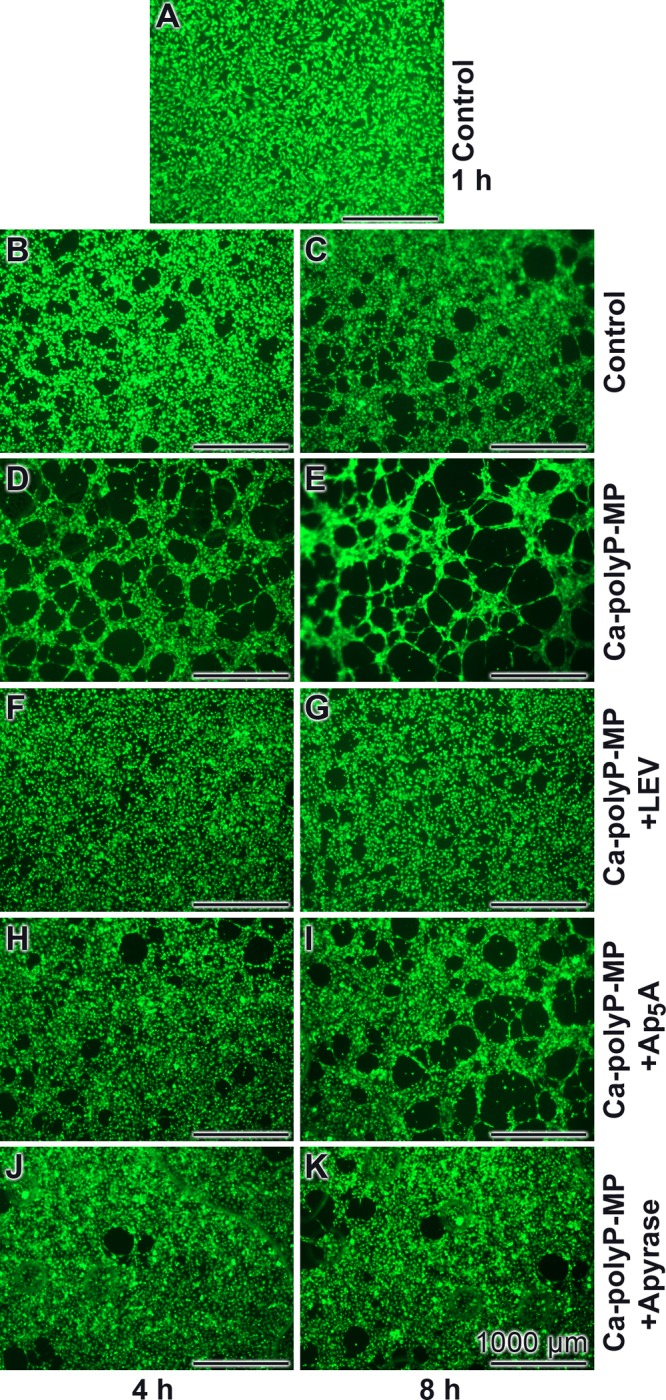

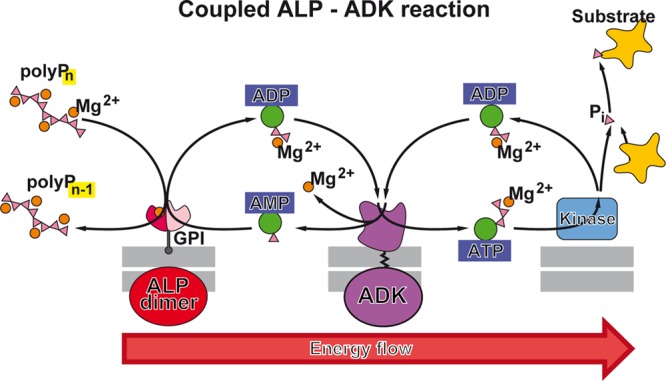

Abstract

Inorganic polyphosphates (polyP) consist of linear chains of orthophosphate residues, linked by high-energy phosphoanhydride bonds. They are evolutionarily old biopolymers that are present from bacteria to man. No other molecule concentrates as much (bio)chemically usable energy as polyP. However, the function and metabolism of this long-neglected polymer are scarcely known, especially in higher eukaryotes. In recent years, interest in polyP experienced a renaissance, beginning with the discovery of polyP as phosphate source in bone mineralization. Later, two discoveries placed polyP into the focus of regenerative medicine applications. First, polyP shows morphogenetic activity, i.e., induces cell differentiation via gene induction, and, second, acts as an energy storage and donor in the extracellular space. Studies on acidocalcisomes and mitochondria provided first insights into the enzymatic basis of eukaryotic polyP formation. In addition, a concerted action of alkaline phosphatase and adenylate kinase proved crucial for ADP/ATP generation from polyP. PolyP added extracellularly to mammalian cells resulted in a 3-fold increase of ATP. The importance and mechanism of this phosphotransfer reaction for energy-consuming processes in the extracellular matrix are discussed. This review aims to give a critical overview about the formation and function of this unique polymer that is capable of storing (bio)chemically useful energy.

1. Introduction

Any kind of chemical or biochemical reaction follows the thermodynamic laws. While chemical systems tend to reach an equilibrium between reactants and products, the reactants in living biochemical systems are usually in a nonequilibrium state.1 Living systems remain in the latter state due to thermodynamic processes that dissipate energy. This fact implies that in biological systems energy-generating/providing circuits are coupled to endergonic reactions. Intracellularly it is ATP that is capturing and transferring free energy.2,3 Under standard conditions, enzymatic hydrolysis of the terminal high-energy β–γ and α–β phosphoanhydride bonds in ATP to ADP and ADP to AMP, respectively, results in the release of −30.5 kJ mol–1 of Gibbs free energy change (ΔG0). This released free energy is used as fuel for driving energetically unfavorable processes, like channeling of molecules against a concentration gradient via ATP-powered pumps, movement of cilia, contraction of muscle or synthesis of biopolymers. In animal cells, and most nonphotosynthetic cells, fatty acids and sugars are metabolized during aerobic oxidation to CO2 and H2O, and the energy liberated is, at least partially, stored as biochemically usable energy in phosphoanhydride bonds of ATP. In eukaryotes, the final stages of aerobic oxidation occur in mitochondria, whereas in prokaryotes those reactions proceed on the plasma membrane. In addition, substrate-level phosphorylation steps take place during which ATP or GTP is formed directly from ADP or GDP. In plants, light energy is converted to chemical energy and stored in the chemical bonds of carbohydrates.

The intracellular cytosol has a sol consistency which thwarts especially the low-molecular weight molecules to diffuse freely. This highly dynamic and yet exquisitely organized cytosol undergoes sol–gel transition (gelation) in response to changing pH conditions and changing ions/molecules supplementation.4 Already this property allows a fairly stable regional organization of the cytosolic metabolic pathways. In the next higher hierarchical level of complexity, the cytosol in eukaryotes harbors insoluble suspended particles, like ribosomes and organelles. Semipermeable membranes around the organelles build a barrier and implement a further possibility for control of the different metabolic cycles, the intracellular transport or metabolic energy production/utilization.5 In addition, this compartmentalization builds a protection mechanism against the activity of lytic enzymes, like those of the lysosomes.

One prerequisite for the emergence of life was the separation of the cellular environment from the surrounding, external environment, which was accomplished by the cytoplasmic membrane with a width of ∼6–10 nm built of a phospholipid bilayer into which (glyco)proteins, glyoclipids, and cholesterol molecules are embedded too.6 These hydrophobic structures undergo self-assembly and exclude water interactions between the cell interior and the extracellular space.7 ATP-dependent as well as ATP-independent transporters establish and maintain a membrane asymmetry. The exchange of molecules between the cytoplasm and the extracellular milieu is enabled by both passive (without energy consumption) and active transport (energy-dependent transport against a concentration gradient or an electrochemical gradient) using a variety of channels and transporters.8 Mitochondria are the major intracellular ATP generator producing ∼32 mol of ATP from 1 mol of glucose which is metabolized via glycolysis and the citric acid cycle. ATP synthesized in mitochondria or during glycolysis is found to play parallel and/or separate, distinct roles during differentiation and migration.9,10

ATP cannot diffuse across the plasma membrane into the extracellular space unless it is channeled through, for example, the conductive ATP-releasing pathways.11,12 In addition, a series of ATP-permeable channels have been identified that are grouped to the connexin channels, hemichannels, pannexin 1, Ca2+ homeostasis modulator 1, volume-sensitive outwardly rectifying anion channels, and the maxi-anion channels. In spite of these varieties of ATP export channels, the intracellular ATP concentration is much higher and can reach up to 100 mM in the neuronal synaptic vesicles, compared to the extracellular environment with 10 nM (see refs (11 and 13)). In human blood, the ATP levels are in the range of 20 and 100 nM.13 In this context, it is interesting to mention that mammalian erythrocytes do not contain any mitochondria with the consequence that the level of ATP in those cells is low with 360 nM, compared to 8500 nM (average level for 106 cells) in T lymphocytes.14 It should be noted that precise measurements of the low, nanomolar ATP levels in the tissue interstitium are technically difficult, in particular, close to the cell surface where ATP seems to increase.13

While the energetics within cells is quite well understood the extracellular energetic cycle(s) are poorly addressed. In general, the extracellular space does not contain mitochondria, with the exception of the blood platelet environment during inflammatory responses. During this state extracellular mitochondria have been identified together with neutrophils in vivo, triggering neutrophil adhesion toward the endothelial wall.15 In most human tissues the volume occupied by cells is substantially smaller compared to the volume of the surrounding extracellular matrix (ECM), like in cartilage which contains about 1–2% of cells16 or calcified bone which comprises about 25% organic matrix (of which 2–5% contributes to cells), 5% water and 70% inorganic mineral.17 Now, the pressing question emerges, which addresses the fueling of the dynamic and complex ECM with metabolic energy, a space which does not contain ATP-generating mitochondria. Even more, the ECM is, as outlined above, poor in ATP, and if present in this compartment, this nucleotide is exposed to the extracellular or cell membrane-bound alkaline phosphatase (ALP [EC 3.1.3.1]) and the cell membrane glycoprotein-1 phosphodiesterase [EC 3.1.4.1]/nucleotide pyrophosphatase [EC 3.6.1.9].18 The diffusion level of ATP in the protein-rich ECM as well as in the cytosol is lower than the one in water;19 for example, the diffusion in the cytosol amounts to approximately 5 × 10–10 m2 s–1.20 An extracellular ADP/ATP carrier has not been identified. It is widely acknowledged that the maintenance of the organization of the ECM in general and especially in cell-poor organs is a high-energy-demanding process. It is very obvious that tissues which contain only a small number of cells, like cartilage or intervertebral discs, receive some of their metabolic energy from their cells by metabolic respiration during glycolysis and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation.21 Hence it must be assumed that nutrients/glucose can only be supplied by diffusion from blood vessels to the margins of the cartilage/discs through the dense ECM of that tissue. Quantitative determinations revealed that the values of the diffusion coefficients in cartilage vary within the range from 0.3 × 10–11 to 30 × 10–11 m2 s–1;22 the diffusion is higher in damaged/degenerated tissue compared to normal cartilage.

Until now, no quantitative determinations are available that support the view that ATP released from cells is sufficient to maintain the coordinated complex ECM structure. Perhaps one reason for this inappropriate situation is the lack of data on energy requiring and energy consuming reactions that proceed in the extracellular space. These, or at least some of those, will be outlined in this review. Furthermore, besides ATP, a new candidate physiological metabolic energy-storing compound in eukaryotes will be introduced, inorganic polyphosphate (polyP). This polymeric polyanion consists of unbranched chains of three up to 1000 phosphate (Pi) residues, linked by high-energy phosphoanhydride bonds. PolyP has been conserved in all biotic organisms from bacteria to animals and can reach in yeast vacuoles levels as high as 20% with respect to dry weight.23 It has been proposed that already in the prebiotic environment polyP was abundantly formed during volcanic eruptions. Emerging evidence is now available, which qualifies polyP, being an abundantly present polymer in metazoan tissue, due to the presence of high-energy phosphate bonds/acid anhydride linkages (reviewed in refs (24−27)), as a polymer that can transfer Gibbs free energy to AMP or ADP under formation of ATP after enzymatic cleavage of the polymer by ALP (reviewed in refs (28−30)).

2. Extracellular Matrix Organization

It is conceivable that the formation of the bulky ECM of metazoan tissues, most prominent with bone [70% contributes to the bone mineral and the remaining organic matrix, consisting of proteoglycans, glycosaminoglycans, and collagen, and only 25% is water],31 cartilage [<20% are cells],32 eye lens [<10% cells],33 and cornea [<10% cells],34 is a strongly energy-dependent process. The reason is that the (macro)molecular components of the ECM exist in a highly ordered, functional arrangement (Figure 1). These extracellular structural molecules are hierarchically composed and have a modular composition. The organization can be operationally grouped into three phases (Figure 1D). First, the synthesis of the macromolecules building the scaffold,35,36 such as collagen extruded from fibroblasts, elastin released from fibroblasts and endothelial cells, and fibronectin secreted from hepatocytes. These fiber-forming or rubber-like structural molecules of the ECM share the property of being dynamic and adapting to the physicochemical conditions of their environment. They are spiral-like and are loosely held together by noncovalent hydrophobic forces. Second, the elasticity of the ECM molecules is a prerequisite for the next step of complexity, the structural and functional organization of these components in the ECM. At this stage the macromolecules become embedded in a hydrogel consisting of proteoglycans and glycosaminoglycans (hyaluronan or heparin) and, to some extent, the fibrous proteins collagen, elastin, laminin, and fibronectin.37 Third, at least some of these organization processes are certainly driven by exergonic reactions, which are kinetically controlled by the flow of energy along metastable morphologies, assembled from the same or adjacent molecular building blocks.38 In addition, the self-assembly of these blocks into regional, tissue-specific, and distinct ECM tissue units requires metabolic energy, especially in the form of ATP. Exemplary highlighted: the transparent cornea with the stromal ECM as the major refractive element of the eye is composed of homogeneous small diameter collagen fibrils which are regularly packed in a highly ordered hierarchical way.39 Initially, in the developing cornea, collagen fibrillogenesis involves multiple molecules interacting in a sequential way, a process which is driven by a cell-directed deposition of aligned collagen fibrils. In the next step tuned interactions between keratocytes and stroma matrix components follow. In parallel, collagen fibrils nucleate and form bundles within cell surface channels or fuse to form fascicles of uniaxial collagen.40 While the mechanism of interaction, e.g., between the small leucine-rich proteoglycans and the collagen fibrils, has been well addressed also with respect to the temporal and spatial organization, the underlying energetics have only been poorly studied. It has been proven that ATP in the extracellular space promotes not only ECM biosynthesis, mediated by cell-based molecular pathways, but also increases the intracellular energy supply.41 In turn, the maintenance of the functional organization of the ECM requires metabolic energy, surely in the form of nucleoside triphosphates, mainly of ATP, as well. Some of those ATP-dependent processes will be mentioned (Figure 2).

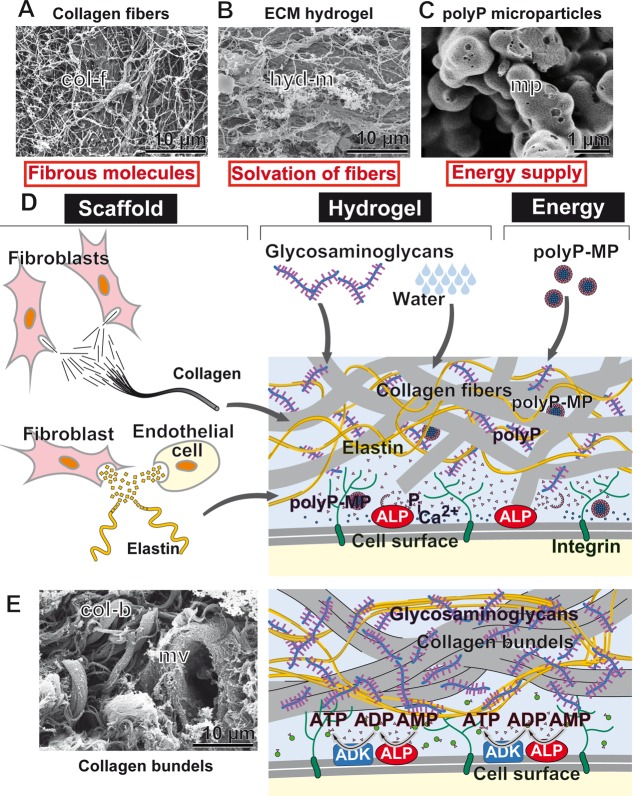

Figure 1.

Extracellular matrix (ECM) as a hydrogel-scaffold into which structural fibrous molecules are embedded in a functionally organized manner. (A) Initially, the collagen fibrils/fibers (col-f) are quite randomly arranged, and (B) become incorporated into a hydrogel matrix (hyd-m), depicted as contracted globular deposits. (C) Microparticles (mp), either released from the blood platelets or added as artificial particles, like Ca-polyphosphate microparticles (polyP-MP), integrate into the scaffold and function as storage for and generators of metabolic energy. (D) The three phases of the hierarchical organization of the ECM scaffold molecules; first, synthesis of the structural macromolecules (scaffold) such as collagen from the fibroblasts and elastin from fibroblasts and endothelial cells, second, formation of the hydrogel molecules such as proteoglycans and glycosaminoglycans, and third, the compartmentation of these scaffold molecules into functional tissue units, which requires organization processes driven by supramolecular assembly/interaction and metabolic energy, like ATP, as stressed in this review. It is proposed that enzymatically controlled hydrolysis of Ca-polyP-MP via ALP generates inorganic phosphate (Pi), Ca2+, and metabolic energy that, in the presence of adenylate kinase (ADK), is stored in ADP and ATP. (E) Organized arrangement of collagen bundles (col-b) that are often associated with microvessels (mv). [(A–C,E) SEM; scanning electron microscopy].

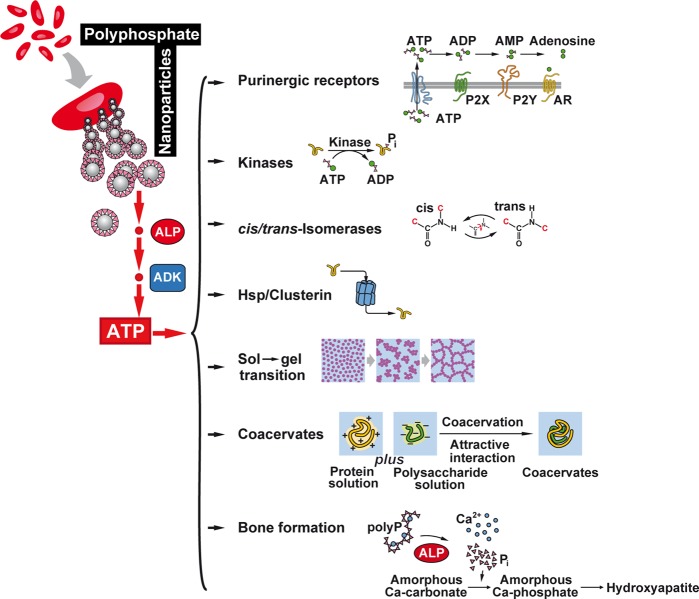

Figure 2.

ATP-requiring processes in the ECM. It is proposed that polyP in the ECM occurs as nano/microparticles that undergo hydrolytic cleavage via the ALP. In concert with the ADK, ATP (ADP, AMP) is synthesized that acts as a metabolic energy reservoir. In comparison, it is shown that ATP, exported from the cells, can act in the extracellular space as signal/ligand for purinergic receptors. During this reaction ATP is not used as metabolic fuel but activates purinergic receptor(s), P2X, P2Y, or adenosine receptors (AR). The ATP metabolizing systems in the ECM include the ECM kinases that control metabolic processes by phosphorylation of key molecules. ATP might also be required during peptidylprolyl cis–trans isomerase reactions. Surely, heat shock proteins (HSP), like clusterin, are also present in the ECM that are involved in the physiological folding of functional polymeric molecules. In addition, processes like sol to gel transitions during supramolecular polymer organization are critical organization principles in the ECM involving exergonic reactions. The transition processes during coacervation likewise follow an energy-favorable reaction pathway. Bone and cartilage formation in the extracellular space are prominent energy-requiring reactions. During bone mineralization Pi and ADP/ATP are generated by enzymatic hydrolysis of polyP via ALP. The released Pi is driving the transition of amorphous Ca-carbonate “bio-seeds”, initially formed during bone mineralization, to amorphous Ca-phosphate and the final deposition of hydroxyapatite.

It should be stressed here that ATP, as well as polyP, is expected to be associated, especially in the extracellular space, with binding proteins. However, only very fragmentary and rudimentary first data have been gathered in this field.42,43 ATP- and polyP-binding proteins could have the role of protecting these metabolites toward degrading enzymes, interfering with potential functional receptors, or allowing their transportation.

2.1. Purinergic Receptors

The plasma membrane comprises integrated purinergic receptors, purinoceptors, that respond to extracellular nucleosides (like adenosine) and nucleotides (ADP, ATP, UDP, or UTP), which act as signaling molecules.44,45 They are involved in learning and memory, locomotion/movement, feeding behavior, as well as in sleep.46 As typical signaling molecules these nucleosides and nucleotides react locally with the purinergic receptors.47 As an example, ATP released from aggregating blood platelets acts as a signaling molecule and elicits endothelium-dependent vasodilatation. During this process nucleosides and nucleotides are released from intracellular organelles and stores and act locally around the extracellularly exposed receptor(s).48 ATP acts as a signaling molecule on the purinergic receptors and, as such, needs to exist only at defined, usually low concentrations, triggering intracellular metabolic reactions.49

Important to note that polyP, present in the mammalian brain, acts in micromolar concentrations as a gliotransmitter between astrocytes P2Y1 purinergic receptors.50 The cells respond with an activation of phospholipase C, followed by a release of Ca2+ from the intracellular stores. Furthermore, besides neural cells, the P2Y purinergic receptors are also found at the surface of cardiomyocytes51 as well as on platelets and other hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic cells with, e.g., the subtype P2Y12.52

In addition to the function of ATP/ADP as a signaling molecule and a link in an autocrine signaling loop, the nucleotides are fed as substrates for metabolic energy-requiring processes in the ECM space. Some examples are given below.

2.2. Kinase Reactions

The intracellular signaling is dependent on amplifiers that potentiate extracellular signals (like hormones) via enzyme reactions (kinase reactions). Over 500 kinases have been described in humans53 and about 30% of the intracellularly existing proteins are phosphorylated.54 Initiated by analyses of the mammalian phosphoproteome, a series of secreted, extracellular proteins with phosphotyrosine units has been disclosed,55 like the vertebrate lonesome kinase (VLK). It is secreted in the ECM as a Tyr kinase which phosphorylates proteins both in the secretory pathway and outside the cell.56 Evidence has been presented that this kinase is physiologically regulated during platelet degranulation and enzymatically active.

2.3. Peptidylprolyl cis–trans Isomerases

The triple-helical protein collagen represents the most abundant ECM component. A series of enzymes, molecular chaperones, and post-translational modifiers facilitates the maturation of collagen. Among them are the peptidyl-prolyl cis–trans isomerases (PPIases) which catalyze an essential step during trans isomerization of the peptidylprolyl bonds, a rate limiting step in protein folding.57 The PPIases cover three families of structurally unrelated proteins, the cyclophilins, FK506-binding proteins, and parvulins. Spontaneous isomerization of peptidylprolyl bonds is a rather slow process at physiological pH conditions; the PPIases substantially accelerate this reaction.58 The first evidence that PPIases are present in the extracellular space came from studies with hensin, an ECM protein that forms 50- to 100 nm-long fibers.59 On the basis of theoretical consideration, it has been proposed that the cis–trans interconversion does not require ATP but instead is driven by energy derived from conformational changes in the protein.58,60 However, more experimental data are required to rule out that ATP is not indirectly involved in those PPIases processes, since for the FK506-binding protein binding of ATP to the domain II has been identified, which has been shown to be functionally active, while GTP is not.61 It remains also to be studied if a functional interplay between prolyl isomerases and ATP consuming HSPs, like with HSP60, during mitochondrial protein import exists, allowing a reduction of the number of ATP binding and release cycles and, in turn, making the folding more efficient and less energy-consuming.62

Interestingly, the formation/assembly of collagen type I monomers into higher organization complexes, into SLS (segment long spacing) crystallites63 with a length of ∼300 nm, is accelerated in the presence of ATP under in vitro conditions.64

2.4. Heat Shock Proteins/Clusterin

Heat shock proteins (HSPs) support and restore not only intracellularly but also extracellularly correct protein folding.65 The chaperones can be grouped into different families, according to their structure, complexity, and regulation.66 First, energy-independent chaperones, which function as monomers, dimers, or oligomers, and second, complex multichaperone machines, which bind to ATP, hydrolyze the nucleotide, and regulate cochaperone as well as substrate protein binding and a subsequent release (reviewed in ref (67)) are key regulators of proteostasis and include TRiC, HSP70, and HSP90. Surprisingly, it has been disclosed that polyP shares protein-like chaperone properties.68 The authors demonstrated that at micromolar concentrations, polyP efficiently prevent protein aggregation during stress conditions, like oxidative stress and higher temperature. Even more, it has been reported that in the presence of polyP, enzymes are stabilized as soluble micro-β-aggregates with amyloid-like properties.69 In continuation of this line, the authors showed that polyP prevents misfolding of the proteins by rendering them in a β-sheet-rich, amyloid-like, soluble conformation.69

Solid evidence exists that HSP70 is present in the extracellular space and released via the MyD88/NF-κB signal transduction pathway.70 Since HSP70 shows functional activity in the presence of ATP, it is more than hypothetical to suppose that HSP70 also binds ATP in the extracellular space, allowing energy-dependent protein folding.71

Perhaps more experimental data on the potential function of ATP toward the extracellularly present HSP clusterin are needed.72 For this protein it has been suggested that it functions independently of ATP hydrolysis,73 even though it comprises the ATP binding domain.74 Another example of an extracellular chaperone with ambiguous interaction with ATP is α-crystallin.72 This molecule protects vertebrate eye lens proteins from adverse protein aggregation. In addition, this protein exists also in extra-lenticular organs, including heart, kidney, and brain.75 In an experimental approach, it could be demonstrated that αB-crystallin, as a molecular chaperone, increases its chaperone functions in the presence of ATP.76 Further experiments are needed to clarify if those mentioned ATP-independent folding processes are not indirectly coupled with ATP consuming reactions.

2.5. Sol to Gel Transition: Supramolecular Polymers

Basically the ECM can be considered as a dense matrix which appears, at first glance, as an impermeable barrier for cells to infiltrate and to migrate into. In accordance with the gelation theory, the sol–gel transition theory,77 it is assumed that gelation starts when soluble polymer chains randomly bind together under formation of growing soluble clusters which assemble together and form a gel. This transition state is critical and fast and only depends upon a slight variation in the bond quantity.78 The directed navigation of cells through the ECM requires a series of intracellular biochemical signaling pathways which are probing the microenvironment through integrin-mediated adhesion circles. These cellular physiological processes must be coordinated with phase transition changes in the ECM during which the thermodynamical equilibrium shifts to a partition. This process requires free energy.79,80 It is known that within cells, ATP-driven processes cause fluctuations which usually result in random movements that can become directional if driven by motor proteins.81

Sol–gel transition processes often accelerate the coassembly of two components in supramolecular systems, like in hydrogels, the ECM, or in the cytoplasm. Supramolecular polymerization is caused and mediated by noncovalent interactions, which are usually weaker than covalent ones,38 but in contrast to covalent ones more wide-ranging and more specific. Even more, because of their property to be highly flexible in their organization, the molecules associated with functional units in the ECM are rarely used for a static stabilization of the cells. Specifically, the supramolecular polymers are prime candidates allowing a transitionally membranous scaffold formation in the ECM in order to set up extracellular functional compartments.82 In addition to those, some transport systems lined with epithelia, transcellular, pericellular, and paracellular transport pathways are characterized by a high flexibility in the ECM.83 Examples are the claudin–claudin cis interfacial structures that organize the dynamic and flexible nature of tight junction strands.84 Likewise, transcellular functional organization of aligned scaffolds is relevant for the formation of transcellular units and, by that, for an efficient transmission of information between neurons85 and basically between any other cell systems. Those flexible structures, based on supramolecular polymers, are energy requiring and energy consuming. If those structures are not fueled by metabolic energy, the transport systems should stall. In consequence, the mentioned self-adaptive supramolecular organizations and cycles are energy dissipating systems. As shown for micelles, the growth and breakdown of supramolecular associations are ATP-dependent.86 More generally, it can be proposed that a failure of ATP-driven transient supramolecular interactions in the ECM, like in the intracellular environment, results in a collapse of the metastable state of all living systems.

2.6. Coacervation

Related to the sol to gel transition process is the coacervate phase transition during which organic-rich droplets are formed via liquid–liquid phase separation, resulting in an association of oppositely charged polymeric molecules.87 This process requires the availability of free energy and entropy in the system.88

2.7. Bone and Cartilage

It is well-established that mechanical energy is stored as elastic energy in both nonmineralized and mineralized components in the ECM.89 Besides those energy-storing and dissipating systems in collagens and tendons,90 the less flexible human skeleton, contributing with about 15% to the total body weight, requires metabolic energy, like for released elastic strain energy, for the formation as well as continual maintenance and repair of this dynamic tissue. It is indicative that during the onset of osteoblast mineralization, ATP levels in those cells peak, a process which is paralleled with the accumulation of mitochondria with high-transmembrane potentials in those regions;91 subsequently, fully differentiated osteoblasts revert to glycolysis to maintain ATP production.92 These findings indicate that the development and the bioenergetic programs of the osteoblasts are coupled with the mineralization state. Furthermore, osteocalcin, secreted solely by osteoblasts, increases insulin sensitivity and modulates an array of genes involved in energy expenditure, like for Ucp2. Its protein product causes mitochondrial uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation under dissipation of energy as heat.93

In addition, polyP turned out to act as a source of inorganic phosphate needed during bone mineralization for the transformation of the initially formed amorphous calcium carbonate deposits (“bio-seeds”) into amorphous calcium phosphate (for a review, see ref (30)). While the calcium carbonate bioseed formation is enzyme-catalyzed by a membrane-associated carbonic anhydrase (CA-IX), the exchange of carbonate by phosphate in the amorphous calcium carbonate proceeds nonenzymatically but requires prior hydrolysis of polyP mediated by ALP. The amorphous calcium phosphate subsequently undergoes a phase transition to hydroxyapatite (Figure 2).

During bone and cartilage formation, like during wound healing, vascularization is one important process to happen and is essential for tissue construction and repair. During the initiation of this process, endothelial cells have to form initial small vessels. During this initial phase, the orientation, guiding, and ring formation of endothelial cells is mediated by ATP which is released into the extracellular space and acts as a chemotactic gradient along which the cells migrate.10,94

In conclusion, among the above-mentioned processes in the ECM which are evoked by ATP, some of them are most likely dependent on metabolic energy, generated during the cleavage of the energy-rich bonds of the nucleotide. Examples are the ATP-requiring processes during the following reactions: phosphorylation reactions driven by ECM kinases, the peptidylprolyl cis–trans isomerase process during collagen packaging, some heat shock protein-mediated actions, coacervation, sol to gel transition processes during supramolecular polymer organization, and finally formation of bulky extracellular tissue, like in bone and cartilage.

In section 13 experimental evidence is given, underscoring that extracellular ATP is enzymatically generated from polyP.

3. Structure of polyP

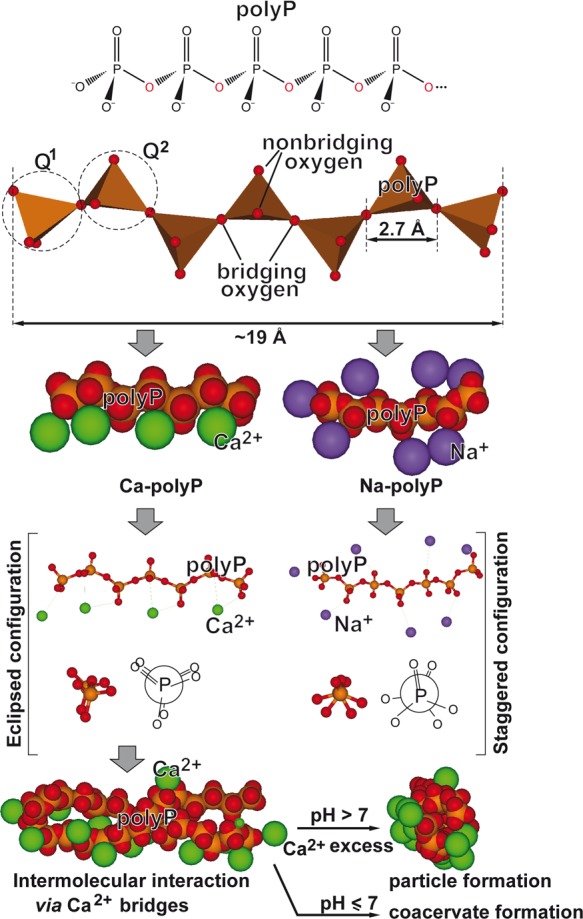

Every pro- and eukaryotic cell contains inorganic polyphosphate (polyP) with a chain length that can reach up to several thousands of orthophosphate (Pi) residues (Figure 3; see refs (24, 25, 95−97)). The tetrahedral Pi units forming this polymer are linked together by high-energy phosphoanhydride bonds similar to those found in ATP. While microorganisms usually contain very long-chain polyP, ranging in size from hundreds to thousands of Pi residues, eukaryotic cells synthesize polyP chains which are much less heterodisperse and comprise polymer lengths of ∼60–100 Pi units.

Figure 3.

Structure of the polyP molecule composed of interconnected PO4 tetrahedra, linked via their bridging oxygen atoms. The linear polyP consists of both Q1 (one bridging oxygen) and Q2 (two bridging oxygens) tetrahedra. Because of the rotational flexibility of the P–O–P (phosphoanhydride) bonds, the polymer can occupy various steric conformations (staggered and eclipsed), in dependence on the counterion. The space-filling models and ball-and-stick models of Ca-polyP and Na-polyP are shown. The divalent Ca2+ salt of polyP assumes an eclipsed configuration, while for the monovalent Na+ salt of polyP a staggered configuration is found. Higher-ordered structures formed by an intermolecular Ca2+ bridge formation comprise both solid particles (at alkaline pH and Ca2+ excess) and coacervates (at lower pH values).

3.1. PolyP Chain

In accordance with the Qi nomenclature (i = number of bridging oxygens), the linear polyP is composed of both Q1 and Q2 tetrahedra with one (terminal Pi units) and two bridging oxygens (internal Pi units), respectively98 (Figure 3). Branched polyP chains (“ultraphosphates”) with Q3 tetrahedra (three bridging oxygens) are not found in living organisms. The P–O bond lengths within the Pi units are between 1.62 and 1.66 Å for the single bonds99,100 and 1.52 Å for the P=O double bond.101,102 The length of the P=O bond is much shorter than the sum of the two atomic single-bond radii (P: 1.07 Å and O: 0.66 Å)100 due to the difference in electronegativity (P = 2.1; O = 3.5). On the basis of these values and the bond angles of P–O–P and O–P–O bonds (P–O–P: 130° and O–P–O: 102°),103 the maximum length (longitudinal size) of the linear polyP molecules can be estimated from the size of each phosphate unit (2.7 Å); e.g., the maximum size of polyP40 (usually used for the formation of biomimetic polyP nanoparticles; see below) amounts to 108 Å, while the maximum size of the long chain polyP produced by bacteria (around 1000 Pi units), which accomplish structural properties, is in the range of ∼3 × 103 Å (∼300 nm). Since the bond angles within the Pi units can vary between ∼120° to 180°,104 and the polymer is physiologically complexed to divalent cations, a smaller value for the space-filling area is, however, more realistic.

3.2. PolyP Conformations

In addition and due to a high degree of rotational flexibility, the polyP chain can occupy various conformations, staggered and eclipsed,104 depending on the arrangement of the tetrahedral PO4 units (Figure 3). In this way, the polymer can adjust to the charge and the coordination requirements of the respective counterions which can be monovalent (e.g., Na+ or K+), divalent (e.g., Mg2+ or Ca2+), or trivalent (e.g., Gd3+) cations. The eclipsed configuration seems to be optimal for divalent Ca2+ ions, as confirmed by modeling studies with pyrophosphate,105 while the monovalent Na+ salt of polyP prefers a staggered configuration. The higher binding energy of the fully charged polyanionic polyP to divalent cations is the major factor that determines the preferential binding of Mg2+ and Ca2+ at physiological pH; at a lower pH/charge density of the polymer, monovalent cations increasingly bind to the polyP chain.106 Based again on modeling studies, Ca2+ ions are able to form with polyP molecules organized aggregates/particles whereby–in the presence of a small number of polyP chains–the divalent cations occupy a more peripheral position (Figure 3).

4. Difficulties and Challenges in Analysis of Cell-Associated polyP and in Identification of polyP Metabolizing Enzymes

The polyP polymer has been identified comparably late after the discovery of ATP, first described as adenyl pyrophosphoric acid, by Lohmann.107 Initially named RNA,108 the basophilic polymer was later identified as metaphosphate by Schmidt et al.109 and later as polyphosphate.110 The first suggestion that polyP can serve as an energy-rich phosphate came from Ebel in 1952 (see ref (111)). The first attempts to understand the polyP metabolism were performed by Liss and Langen.112

4.1. Chemical Analysis of polyP

Despite the increasing importance of polyP in medicine and biotechnology as well as in environmental research, the chemical and biochemical analytics of the polymer are not well developed.113,114 Starting with biological and environmental samples, a significant disadvantage is seen in the isolation procedure because during the extraction of the polymer other phosphate-containing compounds are coisolated. Initially, polyP was adsorbed to charcoal, followed by LiCl desorption.115 After delipidation and alkali treatment, the material was neutralized with perchloric acid. The polyP in the fractions was determined after hydrolysis in acid and corrected for the orthophosphate content.116 In addition, especially if an accurate chain length is attempted to be determined, an interference with the ALP is a serious pitfall since this enzyme readily hydrolyzes the polymer during and after the extraction process from living tissue, especially from eukaryotic cells.117

An improvement was reached by application of a sequential extraction procedure, by isolation first of acid-soluble polyP and second of long-chain polyP at neutral pH.118 After removal of proteins using phenol-chloroform and nucleic acids by precipitation of polyP at neutral pH, the polyP factions (short chain and long chain) were collected by ion exchange chromatography. The polymer was quantitatively assessed after charcoal adsorption, by a total phosphate colorimetric assay, including also the toluidine blue colorimetric reaction.118,119 This basic extraction concept is still applied today97,120 and includes extraction after breaking up the cells with a chaotropic agent, like guanidinium thiocyanate, followed by enzymatic digestion with proteinases, phenol/chloroform mixture extraction, and anion exchanger-based chromatography. The chain length of polyP was determined by thin layer chromatography (short- to medium-chain polyP), ion-exchange chromatography, gel-filtration, electrophoresis on urea-polyacrylamide gels or 31P NMR spectroscopy.119−123 The calibration of the systems was achieved with either fluorescently or radiolabeled polyP markers.124−126 Introduced is also the overall determination of polyP, using the Fourier transform spectroscopy (FTIR),30 a technique which can be used also quantitatively.113 A less practical but comparably sensitive method for the quantitation of polyP was introduced with the fluorescence Ca2+ indicator fura-2.127 The fluorescence intensity in this system was found to be abolished with increasing polyP concentrations. This method turned out also to be applicable for the determination of polyP catabolic enzymes.

4.2. Determination of polyP in Intact Cells

It is of serious disadvantage that for polyP a specific dye does not exist. Very often the fluorescent dye DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) is used for in situ detection of polyP within cells or tissues.128 However, this reaction is not specific since DAPI stains also nucleic acids with only slightly different characteristics. The dye toluidine blue is less frequently used.129

4.3. Assays for polyP Metabolizing Enzymes

Due to the lack of precise polyP quantification techniques, faithful methods for the quantification of enzymatic reactions of polyP metabolizing enzymes are also not available. As an example, the photometric determination of the polyP kinase both acting as a polyP synthesizing enzyme and as a polyP hydrolyzing enzyme might be mentioned.130,131 In the first system, an enzyme-coupled assay with pyruvate kinase and lactate dehydrogenase has been elaborated, while for the reverse reaction, the determination of NADH consumption is used as a changing parameter. Furthermore, a similar assay has been introduced for the polyP-AMP-phosphotransferase reaction132 during which ATP, ADP, and AMP in combination with luciferase and luciferase/adenylate kinase is quantified. Finally, the purine-nucleoside phosphorylase has been used as an enzyme indicator for the quantification of polyP in the reaction.119

In all these assay systems, inaccuracies can creep in especially during the preceding isolation of the polyP product/substrate and the indirect approaches used for quantification of the product. Therefore, more reliable and specific methods have to be developed in the future suitable for a more precise quantification of polyP in cells and also during the enzyme reactions. These remarks should also indicate that some of the existing enzymatic and functional data should be taken with some caution.

5. Physiological Roles of polyP

Because of the presence of multiple energy-rich phosphodiester bonds, long-chain polyP is able to store large amounts of metabolically utilizable energy, much more than an ATP molecule. The energy (ΔG0; standard conditions) released during hydrolysis of a single phosphoanhydride bond within this polymer is similar to that of hydrolysis of the β–γ or α–β phosphoanhydride bond in ATP (−30.5 kJ mol–1) or even higher (ΔG0≈ −40 kJ mol–1).133

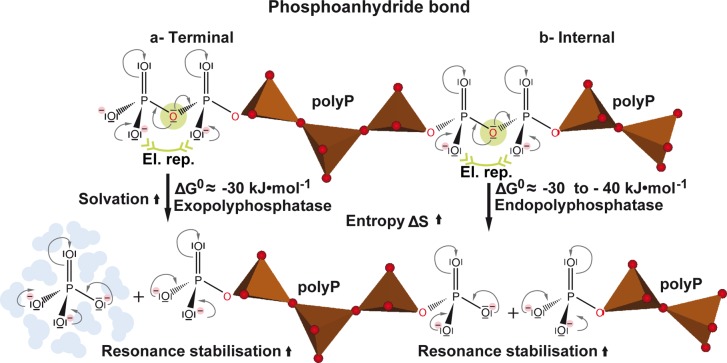

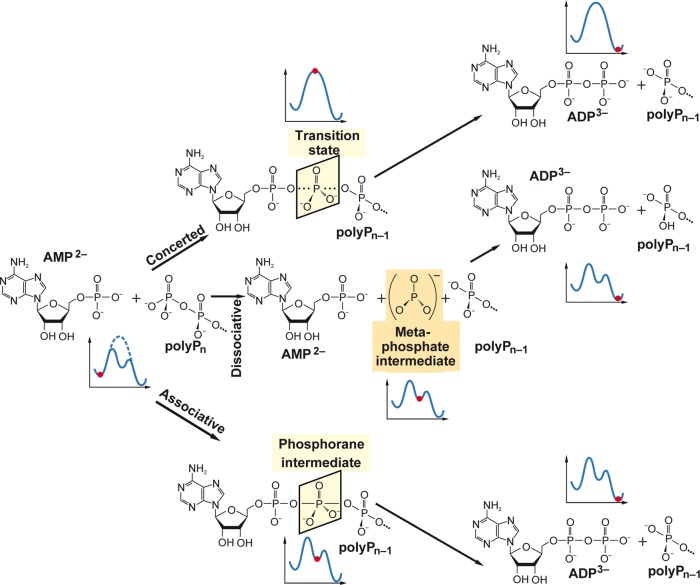

As sketched in Figure 4, several factors, similar to ATP hydrolysis, may contribute to the highly exergonic character of the hydrolytic cleavage of the phosphoanhydride bonds of polyP, which is catalyzed by polyP exo- and endopolyphosphatases, such as the extensive electrostatic repulsion of the negatively charged oxygen atoms on the phosphate groups,134 changes in entropy135 or resonance stabilization136,137 and a higher degree of solvation of the reaction products,135 compared to polyP (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Various factors contributing to the large amount of Gibbs’ free energy released during polyP hydrolysis by exopolyphosphatases and endopolyphosphatases. El. rep., electrostatic repulsion.

It should be noted, however, that under physiological conditions, the actual ΔG values, as with ATP, may be influenced by a number of factors, such as pH, temperature, divalent cations, and ionic strength.138−143 For example, physiologically, polyP (like ATP)144 is coordinated with divalent cations, like Ca2+ and Mg2+.25 Therefore, it is expected that the actual ΔG values for polyP hydrolysis will be significantly different from ΔG0, similar to ATP hydrolysis. For example, in the case of ATP hydrolysis, the actual ΔG values, for example, in the liver, are between −59 and −53.5 kJ mol–1, and in the heart, between −61.7 and −59.5 kJ mol–1;141,145 for in vivo data (human brain and muscle), see ref (146).

In contrast to microorganisms, the biological and biochemical pathways of polyP in higher eukaryotes have been largely unknown for a long time, although this polymer is detectable throughout the entire animal kingdom. This situation changed more recently when it became obvious that polyP has a functional role during bone mineralization147 as well as affects the energy balance within the cells and also in the surrounding ECM.148−150 First indications came from an observation that the amount and turnover of polyP is considerably higher in tissues with high metabolic rates and requirements like the brain or heart.150−152 However, caution is advisible about the reliability of those data since the isolation, purification, and analysis methods used are sometime immature, as pointed out.153

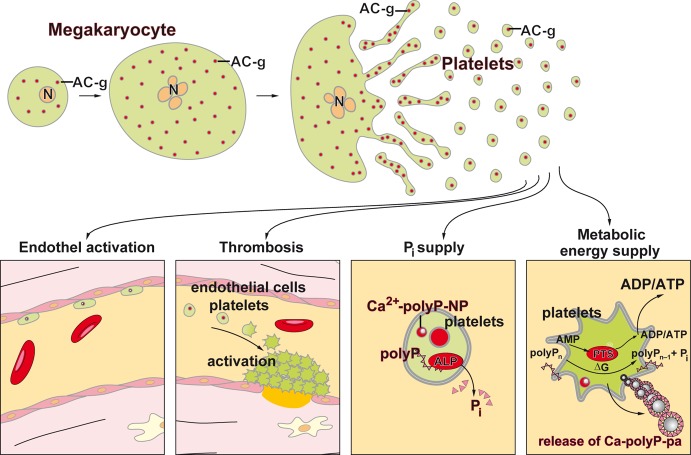

Microorganisms such as bacteria and yeast can accumulate large amounts of polyP. Multiple functions of polyP in these organisms have been demonstrated, e.g., being a source of energy, a donor for sugar and adenylate kinases, and also acting as a chelator for divalent cations and working as a functional buffer against alkaline stress or as a regulator of development. Likewise, the enzymes catalyzing these reactions have been identified (see refs (25 and 26)). However, also vertebrates contain significant amounts of polyP. This polymer has been identified in every animal tissue investigated so far, from mouse heart (∼114 μM), brain (95 μM), and lungs (91 μM) to kidney (64 μM). Lower amounts of polyP are found in the liver (38 μM), while high levels are present in mast cells and especially in blood platelets (up to 1.1 mM).121,154 It might be stressed that blood platelets comprise ∼5%, after erythrocytes (∼85%) but before bone marrow cells (2.5%) and lymphocytes (1.5%), the second most abundant cells in the human body.155 In human blood, a concentration of 1–3 μM polyP has been calculated.96 Also in other body fluids, like in synovial fluids, polyP exists.156 Within mammalian cells, this polymer has been identified in lysosomes,157 dense granules of the acidocalcisomes,121 mitochondria, and nuclei.158

Focusing on the polyP effect within the eukaryotic, mainly mammalian cells, it could be elucidated that polyP is likely to be involved in the following pathways.

5.1. Energy Production and Permeability Transition Pore Induction

In the mitochondria, polyP was found to increase in response to the activation of the metabolic respiration and be reduced by their inhibitors.159 Oligomycin, a known inhibitor of complex V/F1FO-ATP synthase, abolishes the proton gradient at the inner mitochondrial membrane and strongly interferes with mitochondrial polyP metabolism.159 The crucial role of polyP in mitochondrial energy metabolism has been demonstrated by enzymatic depletion of the mitochondrial polyP content using polyP-hydrolyzing yeast exopolyphosphatase PPX1; a significant decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential required for F1FO-ATP synthase-mediated ATP production was observed.160 The major role of mitochondrial polyP at certain pathological conditions associated with ischemic cell death like stroke and myocardial infarction161,162 has been intensively studied. These pathological conditions are associated with a Ca2+-induced activation of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP), a large, voltage-dependent multiprotein channel complex in the inner mitochondrial membrane, causing opening of the channel and leading to increased membrane permeability, decreased mitochondrial membrane potential, abolition of ATP production, and ultimately cell death (for a review, see refs (154 and 163)). Especially reperfusion/reoxygenation therapy of ischemic tissue can result in excessive Ca2+ accumulation inside the mitochondria. Already in the first report on the effect of polyP, evidence has been presented that this polymer is closely associated or a component of the mPTP complex.164 In this study, the isolation of a polyP/Ca2+/poly-3-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) complex from mammalian (rat liver) mitochondria was reported,164 a complex which was first identified in bacteria.165 On the basis of its properties, it was concluded that this complex might act as the ion-conducting module of mPTP.164 The proposed involvement of the polyP/Ca2+/PHB complex in mPTP opening was supported by polyP depletion experiments that revealed a strong inhibition of mPTP function,159,166 resulting in prevention of mitochondrial Ca2+ accumulation and cell death (see refs (154 and 167)). The effects of polyP are correlated with the chain length of the polymer. While long chain polyP (polyP120) can induce/activate PTP and cell death as well as mitochondrial depolarization in astrocytes, medium- (polyP60) and short-chain polyP (polyP15) failed to cause this effect.168 This result has been supported by findings revealing that short and medium polyP does not cause apoptosis while long chain polyP activates the apoptotic cascade in neurons and astrocytes.168 In a more recent study, a highly purified preparation has been obtained from mammalian mitochondria that contained besides the polyP/Ca2+/PHB also the C-subunit of the ATP synthase.169 The properties of this isolated channel-forming complex were quite similar to the native mPTP. The data also showed that polyP, PHB, and the C-subunit are intimately associated as an integral component of the Ca2+-induced mPTP.169 This conclusion was also supported by the finding that the formation of this channel-forming complex is inhibited by cyclosporine A, an inhibitor of mPTP.169 Interestingly, polyP has also been found to be an modulator (activator) of mTORC1 (target of rapamycin complex 1),170 a complex that acts as an intracellular homeostatic ATP sensor by activating a series of anabolic metabolic pathways.171 Recently, it has been reported that a decrease of mitochondrial membrane potential by opening mPTP pores is associated with a rise in calcification of polyP-treated MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic cells.172

5.2. Cell Sensation

The receptor-activated nonselective cation channel TRPM8 (transient receptor potential melastatin subtype 8), a cold-activated channel, is involved in sensing of extracellular temperature, such as coolness, but is also activated by certain chemicals such as menthol. Whole-cell patch-clamp and fluorescent calcium measurements with human embryonic kidney and F-11 neuronal cells revealed that the TRPM8 protein complex forms a stable association with polyP and PHB resulting in a modulation of the sensitivity threshold.173 A related but mechanistically distinct function of polyP, acting on the nociceptive sensation, has been described.174 The TRPA1 receptor (transient receptor potential A1) is expressed in sensory afferent neurons and requires polyP as a soluble factor to become functionally active. In contrast to TRPM8 which copurifies with polyP, TRPA1 only weakly interacts with polyP.

5.3. Cell Metabolism

The overall cell metabolism of human fibroblast cells is activated by polyP.175 This effect has been deduced from the findings that the mitogenic activities of both the acidic fibroblast growth factor (FGF-1) and the basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF-2) are enhanced by this polymer. In addition, polyP increases the adhesion capacity of the cells via their cell surface receptors. Support came also from more recent studies with Caco2/BBE cells.176 These authors described that polyP induces HSP27 gene expression in vitro and causes in vivo a protection of mice against inflammation, elicited by Na-dextran sulfate. Finally, it should be mentioned that higher levels of polyP are present in myeloma plasma cells, which are assumed to modulate the transcriptional activity, catalyzed by RNA polymerase I.177

5.4. DNA Synthesis and Repair

Using yeast cells as a model, polyP was found to increase the intracellular pool of deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs). These “extra” dNTPs were identified to protect the cells against DNA damage and extend the longevity of those compromised cells.178 Subsequent studies with mammalian HEK293 cells and in human dermal primary fibroblasts confirmed this effect by demonstrating that after deprivation of those cells for polyP the cells become more prone to DNA damage.178 In turn, the authors claim that polyP increases the intracellular metabolic energy in the form of ATP needed during the DNA repair process. In the bacterial system Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a close coupling of polyP synthesis with the completion of cell cycle exit during starvation has been demonstrated.179 This aspect of the interaction of polyP with the DNA replication machinery is, at the present state, not completely understood.

5.5. Blood Clotting

It has been suggested that after release from activated blood platelets, synthetic polyP initiates clotting of plasma via the contact pathway on the level of factor XII.120 However, subsequent studies disclosed that when platelets become activated only physiologically occurring short-chain polyP is released, which has only a very low capacity of direct activation of factor XII (see ref (180)).

5.6. Bone Mineralization and Cartilage Formation

Among the most energy-consuming processes proceeding in the extracellular space in humans are the bone and cartilage anabolic processes. An extensive review on this subject has been very recently published,30 and it is also discussed here in the context of energy homeostasis during bone and cartilage formation in the body.

Increasing evidence indicates that polyP can also act as an important mediator of pro-inflammation and pro-coagulation.181 Both activities are beneficial in innate immune response and during at least the initial stages of wound healing, e.g., accelerating the sealing process for severe injuries.182 These authors identified in rat basophilic leukemia mast cells polyP with a chain length of 60 Pi units which they attribute to the serotonin-containing acidocalcisomes. It has been described that those polymeric molecules are secreted from platelets/acidocalcisomes upon activation.120,121

The supporting role of ATP and adenosine being an important metabolite that controls the activity of chondrocytes in rat tibia explants was demonstrated in mice lacking the adenosine A2A receptor.183 Animals with this defect develop spontaneous osteoarthritis, a degenerative joint disorder. Supplementation with adenosine via intra-articular injection prevented the development of the disease.

6. PolyP Metabolism in Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells: Enzymes

Although polyP is an abundantly present inorganic polymer found in all cells from prokaryotes to eukaryotes, the way of synthesis and degradation of polyP in the different kingdoms of life appears to be distinctly different. This partially depends on the different functions of polyP in these organisms. In (eu)bacteria, polyP takes an active/functional role in survival at the stationary phase, stress responses, activation of ATP-dependent serine peptidases, Lon proteases, as well as during virulence184 (reviewed in ref (185)) but also acts extracellularly as an intercellular communication/signaling molecule during quorum sensing processes, and biofilm formation.186 Also in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae and the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum, polyP acts as a signaling molecule during pH homeostasis187 and growth control.188 In animals, polyP is also released into the extracellular space, especially from the platelets, and functions there as a regulator of a series of regeneration processes, e.g., in wound healing,189,190 inflammation,189 and coagulation.180,191

The chain length of the polyP has a decisive effect on the biological effects of the polymer. This has been reported both for intracellular (e.g., mitochondrial) and extracellular polyP. Therefore, the control of the size of the polymer seems to be of utmost importance. In principle, the polyP chain length can be controlled both on the level of polyP synthesis, catalyzed, e.g., by bacterial polyP kinases (PPK) [EC 2.7.4.1], and on the level of polyP degradation. In yeast and higher eukaryotes, different mechanisms for polyP synthesis have been developed, as discussed later.

polyP degradation can occur either by hydrolysis of the polyP chain, catalyzed by polyphosphatases, both by exopolyphosphatases [EC 3.6.1.11] which hydrolyze the polyP chain from the ends of the polymer under liberation of orthophosphate (Pi) and by polyP endopolyphosphatases [EC 3.6.1.10] which cleave polyP within the polymer chain, or by transfer of the terminal Pi groups to an acceptor molecule, mediated by a phosphotransferase. Examples of the latter group of enzymes are a polyP-AMP phosphotransferase [EC 2.7.4.B2] which catalyzes the phosphotransfer from polyP to AMP,192 or a polyP glucokinase [EC 2.7.1.63] which phosphorylates glucose by polyP.193 While in the first case, the energy of the energy-rich phosphoanhydride bond is liberated in the form of heat, this energy is, at least partially, conserved in the latter case in the newly formed phosphoanhydride or phosphoester bond at the acceptor molecule.

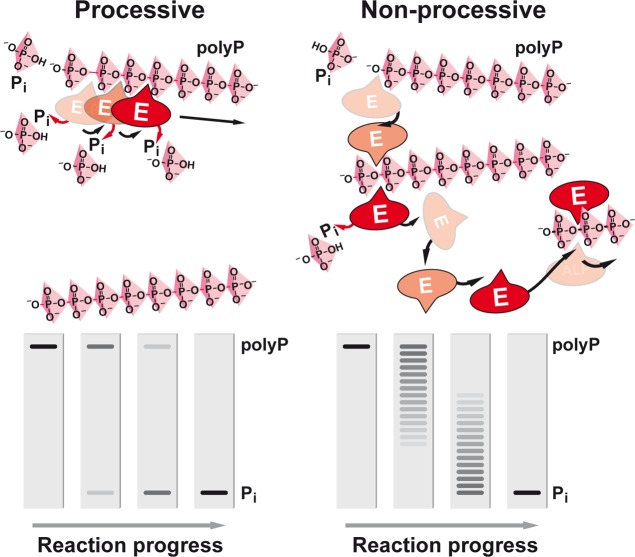

In addition, two principal mechanisms can be discerned through which degradation (but also synthesis) of polyP can proceed: processive or nonprocessive (Figure 5).24,25,117 In the processive reaction, the enzyme (here an exopolyphosphatase) remains bound to the polymer until the degradation of the polyP chain is completed. Analysis of the products on high-percentage polyacrylamide gels will reveal only two bands, the undegraded polyP substrate, which decreases during the reaction, and the product (e.g., Pi), which increases in the course of the reaction. No intermediate polyP chain lengths can be seen. In the nonprocessive mechanism, a successive association and dissociation of the enzyme from the polyP during each catalytic step takes place. In turn, the enzyme continually “jumps” from one polyP molecule to another until the substrate is completely turned over. Consequently, polyacrylamide gel analysis will show a ladder-like pattern reflecting the occurrence of shorter polyP chains between the polyP substrate and Pi product in the course of the reaction. It should be noted that some polyphosphatases break down the polyP to a certain chain length or change from a processive to a nonprocessive mechanism beyond a certain chain length; in the latter case, a laddering pattern is observed below that size of the polyP molecule.

Figure 5.

Processive versus nonprocessive degradation of polyP. In the processive mechanism (left), the enzyme (E) remains bound to the polyP substrate until the degradation is completed, while in the nonprocessive reaction (right), the enzyme dissociates from the substrate after each catalytic cycle and then reassociates either with the same or another polyP molecule.

6.1. Eubacterial Enzymes

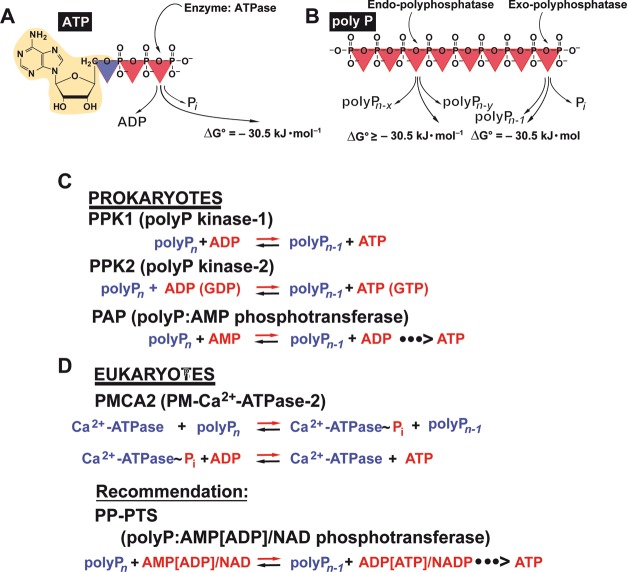

The intracellular, enzyme-driven polyP anabolism and catabolism, especially with respect to the energy metabolism, is well understood in bacteria. In the center of the bacterial energy transfer reactions are the polyphosphate kinases (PPKs),26,194 which synthesize polyP by using ATP as a substrate194 (Figure 6). Besides in bacteria, the PPKs have been identified in archaea, fungi, yeast, and algae (reviewed in ref (185)) but not yet unequivocally in animals.159 The PPKs are reversible acting enzymes transferring energy-rich bonds in both directions.185

Figure 6.

Enzymes involved in energy storage and energy supply by polyP. (A) ATP as the intracellular energy generator, and (B) polyP as an intra- and extracellular energy source and energy generator during the enzymatic hydrolysis by exo- or endopolyphosphatase(s). In both compounds, energy-rich bonds are present that comprise a ΔG0 of about −30.5 kJ mol–1 per bond. The polyP metabolizing enzymes that catalyze reversible reactions are present in both (C) prokaryotes and (D) eukaryotes. In prokaryotes, the initial ATP-dependent step of polyP synthesis is catalyzed by polyP kinases; the reactions catalyzed by polyP kinase 1 (PPK1) and polyP kinase 2 (PPK2) are shown. These reversible reactions can also serve for the formation of ATP (GTP) from polyP. Additionally, it has been suggested that polyP-AMP-phosphotransferases are using polyP as a substrate for the synthesis of ATP via AMP and ADP. For eukaryotes, it has been described that the plasma membrane associated Ca2+-ATPase (PMCA) acts as an ATP-polyphosphate transferase and polyphosphate-ADP transferase. Finally, an ALP is present, which is involved in both polyP hydrolysis and ADP formation from AMP, as well as a NAD-kinase which catalyzes the transfer of the terminally located energy-rich phosphate units of the polyP chain to NAD+ resulting in NADP+ production. We recommend to group these phosphotransferases which also includes the PPK (reversible reaction) as polyP-phosphotransferase system [PP-PTS].

Due to the comprehensive studies of the Kornberg’s group, the enzymatic metabolism of polyP in prokaryotes has been resolved. The initial ATP-dependent step of polyP synthesis is mediated by the polyP kinase 1 (PPK1 [EC 2.7.4.1]), most likely the dominant enzyme in bacteria (reviewed in refs (195 and 196)). Experimental data indicate that the metabolic energy, stored in polyP, can be reutilized in bacteria to synthesize ATP. A second bacterial polyP kinase, the PPK2 [EC 2.7.4.1]197 has been described that shows similarity to the mammalian thymidylate kinase.198 In addition, several bacterial PPKs have been identified that use preferentially pyrimidine nucleotides as cosubstrates; they were termed PPK3 [EC 2.7.4.1].199

polyP degradation in bacteria is catalyzed both by the polyP kinases (reversible reaction of PPKs) and exopolyphosphatases which only hydrolyze the polymer chain.200,201 A well investigated polyP degrading exopolyphosphatase is the bacterial exopolyphosphatase (PPX [EC 3.6.1.11]) from Escherichia coli a highly processive enzyme that preferentially hydrolyzes long polyP chains (≥1000 Pi residues).125,201,202 The enzyme is a dimer201 which produces four discrete intermediates: polyP2, polyP3, polyP14, and polyP50. In a model proposed,125 each monomer of the PPX dimer contains two catalytically active N-terminal sites and three polyP binding sites located at a distance of 3, 14, and 50 Pi residues from the active site.

Two further examples of an enzyme that produces intermediates with a specific chain length during degradation are the E. coli polyP guanosine pentaphosphate phosphohydrolase (GppA) [EC 3.6.1.40]203 and the polyP glucokinase [EC 2.7.1.63] of Propionibacterium shermani which phosphorylates glucose by polyP.193,204 Both enzymes degrade long chain polyP by processive hydrolysis of the terminal phosphates until a specific chain length of 40 Pi units (polyP40; for GppA)203 or 100 Pi units (polyP100; for polyP glucokinase)193,204 is released.

Additionally, a bacterial polyP-AMP-phosphotransferase (PAP [EC 2.7.4.B2])192,205 has been described that apparently metabolizes polyP as a substrate for the synthesis of ADP and ATP via ADP (the latter reaction, ATP formation, proceeds together with an adenylate kinase),206,207 as well as an enzyme from P. aeruginosa that acts both as a polyP:ADP phosphotransferase and an exopolyphosphatase.208,209 The active site of latter enzyme is assumed to be involved in both enzyme activities.209

In contrast to yeast and animals, endopolyphosphatases which cleave polyP in the middle of the chain seem to be absent in bacteria.

Interestingly, the polyP glucokinase from P. shermanii can change from a processive to nonprocessive mechanism. The degradation of long chain polyP by this enzyme proceeds via a processive mechanism, while short polyP is hydrolyzed nonprocessively.193,204 This change of the type of reaction is paralleled by a change of the Km of the enzyme that first increases slowly with decreasing polymer size but then dramatically increases at a chain length of 30 (polyP30). After reaching this size, the enzyme dissociates from the polymer and further degradation proceeds by a nonprocessive mechanism.

6.2. Fungal Enzymes

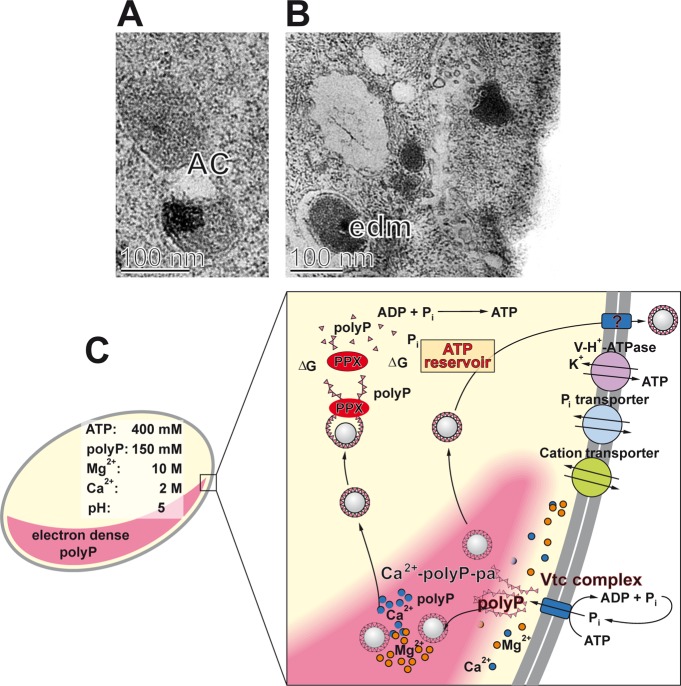

Some phylogenetic data revealed that eukaryotic fungi share a close relationship with animals.210,211 In yeasts, polyP accumulates in large amounts inside the vacuole, an acidic, acidocalcisome-like organelle,212 where cellular compounds are recycled. This vacuole is a dynamic structure that can rapidly modify its morphology. There the polyP polymer accumulates and is additionally found in smaller levels in the cytosol, nucleus, and mitochondria (reviewed in ref (213)).

Using the yeast S. cerevisiae as a model, most knowledge on polyP metabolism in eukaryotes has been gathered. Among the yeast enzymes involved in polyP metabolism are the cytosolic exopolyphosphatase PPX1,214,215 the cytosolic endopolyphosphatase DDP1,216−218 and the vacuolar endopolyphosphatases PPN1,219−221 which can switch between exo- and endopolyphosphatase activity,222 and PPN2.223,224 In addition, a vacuole transporter chaperon complex (Vtc complex) has been identified that synthesizes polyP and acts as a main phosphate storage molecule in yeast. This polymerase uses ATP as a substrate and transfers the γ-phosphate to an acceptor phosphate under formation of a polyP chain.225 This complex is also involved in the translocation of polyP across the vacuolar membrane (see section 8).

Different reversibly acting PPKs have been identified in other fungal taxa, like in arbuscular mycorrhiza or in the funguslike slime mold D. discoideum.226,227 In addition, PPK-like enzymes have been identified that use other cosubstrates such as the 1,3-diphosphoglycerate:polyphosphate phosphotransferase.25,228

The S. cerevisiae polyphosphatases have been extensively studied. These enzymes differ in their substrate specificity (preference for long polyP or for short polyP chains), mode of action (processive or nonprocessive), dependence on metal ions, and response to inhibitors;126,229,230 for a recent review, see ref (213). The PPX1 which degrades long-chain polyP to PPi in a processive manner under the release of Pi230 is a member of the DHH family of phosphoesterases,231 like the mammalian protein h-prune which also acts as an exopolyphosphatase (see below).232 On the basis of the analysis of the crystal structure, the yeast enzyme is assumed to contain a positively charged tunnel-like structure with multiple arginine and lysine residues, which channels the entering polyP polymer from one end to the catalytic site at the other end of the protein.233 The existence of such a tunnel-like structure has also been proposed for certain polyP-binding proteins.234 Also an enzyme related to the yeast PPN1 has been partially purified from rat and bovine brain220 but not further studied. The DDP1 belongs to the Nudix hydrolase family and seems to be primarily involved in inositol pyrophosphate metabolism but can also act as a polyP-hydrolyzing endopolyphosphatase.216−218

6.3. Enzymes from Other Eukaryotes and Animals

In the trypanosomes, the acidocalcisomes have been first discovered and, in turn, used as a model for the understanding of the role and function of these organelles in polyP metabolism also in animals.235

6.3.1. Trypanosomes/Unicellular Eukaryotes

Several exopolyphosphates have been isolated, cloned, and expressed from the major human pathogenic unicellular eukaryotes Trypanosoma brucei, Trypanosoma cruzi, and Leishmania major. In contrast to the yeast enzymes, these exopolyphosphatases preferentially hydrolyze short-chain polyP, such as the exopolyphosphatase from T. cruzi,236 the cytoplasmic PPX1 from T. brucei (degradation of polyP3, but not PPi and long-chain polyP),237 and the exopolyphosphatase from L. major, which is localized in the acidocalcisomes and cytosol.238 In addition, some members of the Nudix family of enzymes were found to hydrolyze polyP, such as the T. brucei Nudix hydrolases TbNH2, an exopolyphosphatase located in peroxisome-like organelles (glycosomes) where glycolysis occurs, and TbNH4, an endo/exopolyphosphatase located in the cytosol and nucleus.239,240

6.3.2. Animals

As outlined, until today, an enzyme related to the PPKs has not been identified in higher eukaryotes. It should be granted that, within the cells, in the first place ATP should be considered as the cosubstrate for the enzymatic synthesis of polyP. This energy-carrying nucleotide is assumed to be synthesized intracellularly at two metabolic intersections, either within the mitochondria during the enzyme-controlled reduction/oxidation reactions or in the cytoplasm at the substrate-level phosphorylation steps, like in glycolysis during transfer of a phosphate group to ADP from 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate yielding 3-phosphoglycerate (phosphoglycerate kinase reaction) and from phosphoenolpyruvate producing pyruvate (pyruvate kinase reaction). In these two compartments, mitochondria and cytosol (membrane associated), polyP synthesizing enzymes have been identified.

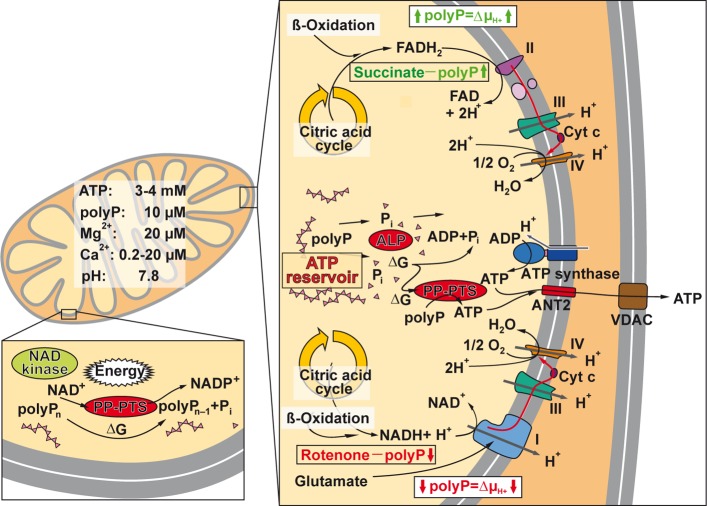

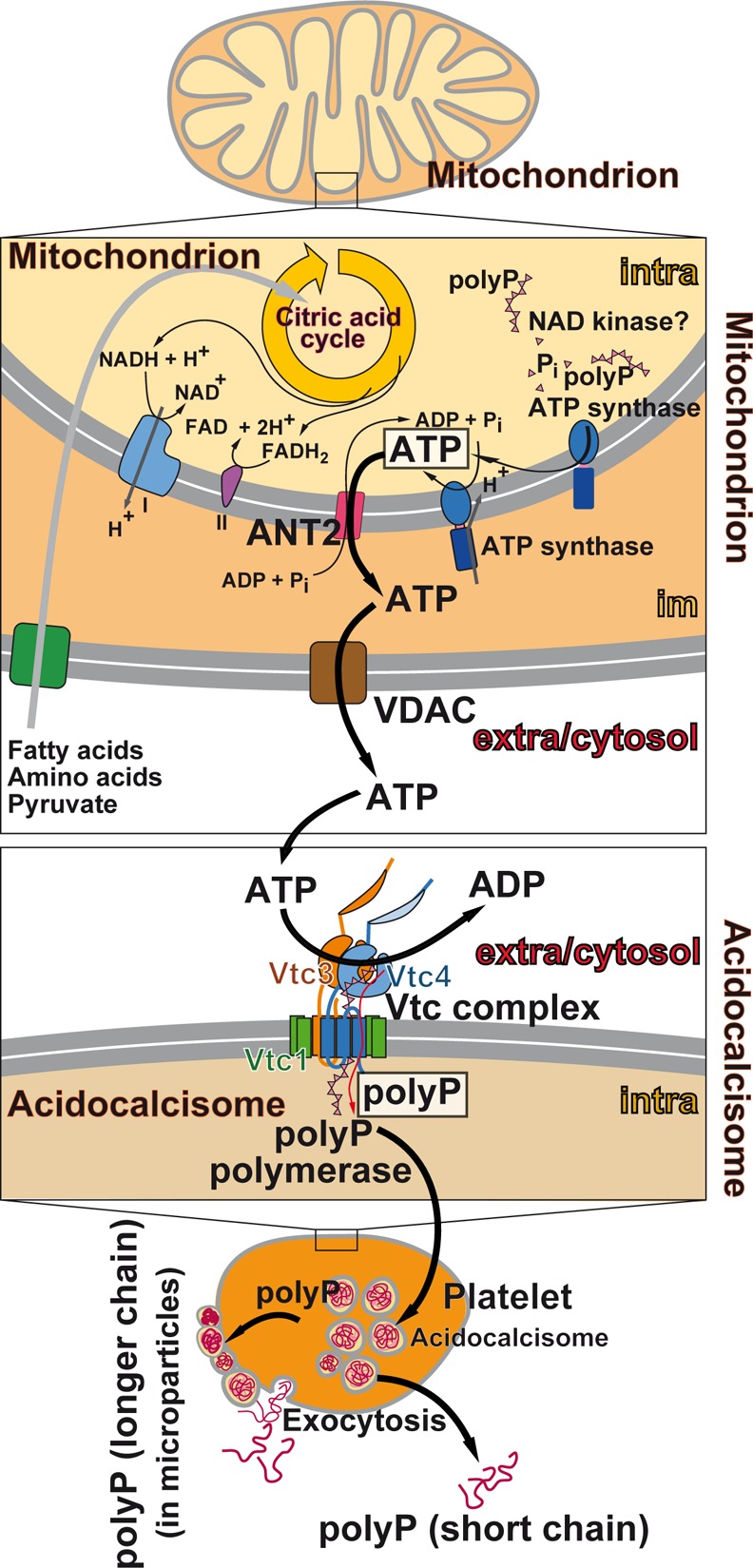

The mitochondrial ATP-synthase (F1FO-ATP synthase [EC3.6.1.34]) has been proposed to be involved in the synthesis of polyP.159 The authors conclude that polyP synthesis is directly linked with the ATP generation system of the mitochondria and with their energetic state; they propose that a feedback mechanism regulates the levels of polyP and of ATP and reciprocally (Figure 7). It has been suggested, based on the strong evidence that the energy level of the mitochondria is closely correlated with polyP level, that the synthesis of the polymer starts on pyrophosphate241 that becomes elongated by an unknown polyP-synthesizing enzyme. The level of polyP in mitochondria is ∼10 μM151 and that of ATP 3–4 mM.242 Enzymatic removal of polyP in mitochondria, via expression of yeast exopolyphosphatase (PPX), results in a decrease of the mitochondrial membrane potential and an impairment of the respiratory chain.243 This finding can be taken as an indication that polyP might act in the mitochondria as a reservoir for metabolic energy generation in the form of ATP (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Mitochondria as storage of ATP and ATP buffering organelles. These organelles are the major intracellular ATP generator producing ATP from reducing equivalents during metabolism of glucose and fatty acids via glycolysis (cytosol) and β-oxidation and finally the citric acid cycle (mitochondrion). The reducing equivalents drive the electron transport chain in the inner mitochondrial membrane, which ends in the ATP generator, the ATP synthase. The adenine nucleotide translocase (ANT2) allows the ATP to cross the mitochondrial inner membrane, while the voltage-dependent ion channel (VDAC) is involved in the energetic flux and transport of ATP and ADP across the outer mitochondrial membrane. Within the mitochondrial matrix, polyP is proposed to be metabolized via the NAD kinase (insert), an enzyme that catalyzes the phosphorylation of NAD+ to NADP+ under consumption of ATP and other nucleoside triphosphates as well as of polyP as a phosphate source. Most likely many of these complex enzymatic reactions, including the ALP and the NAD kinase, act as PP-PTS. A reduced polyP level parallels with a decrease of the mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔμH)/proton gradient (ΔpH+) at the inner mitochondrial membrane and vice versa. The approximate concentrations of ATP, polyP, Mg2+, and Ca2+ as well as the intramitochondrial pH value are given.

In addition, experimental evidence has been presented demonstrating that the plasma membrane associated Ca2+-ATPase (PMCA) from erythrocytes might function as an ATP-polyphosphate transferase and polyphosphate-ADP transferase.244 The PMCA belongs to the group of PMCA2 [EC 3.6.3.8] since the enzyme forms a phosphate intermediate during the reaction cycle.245−247 Consequently, it has been postulated that the PMCA2 is associated with polyP allowing also a transient covalent autophosphorylation, followed by a transferase reaction and, by that, the formation of ATP.244,248 It would be interesting to study this enzyme in further detail.

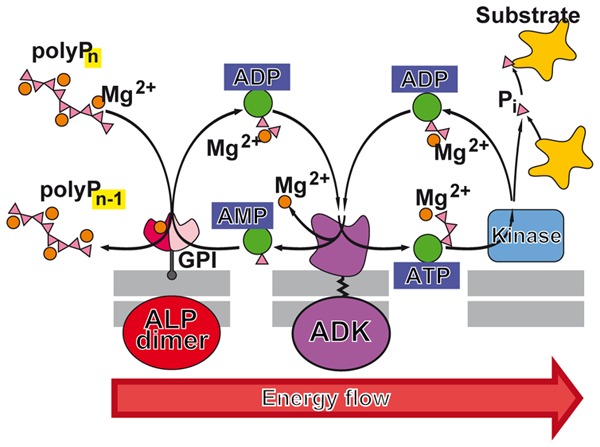

Among the mammalian enzymes involved in polyP degradation, only one enzyme that corresponds to the yeast PPX1 has been identified, the exopolyphosphatase h-prune which belongs to the DHH family of phosphoesterases.232 However, this enzyme, in contrast to the yeast PPX1, is a short-chain exopolyphosphatase and inhibited by long polyP chains.232 The major exopolyphosphatase in mammalian organisms including humans, which also degrades long polyP chains, seems to be the alkaline phosphatase (ALP); see section 7. We propose that this enzyme also acts as a phosphotransferase, as discussed in section 13, like the NAD kinase [EC 2.7.1.23]. The latter enzyme has been traced in mitochondria, mediating NADP+ biosynthesis from NAD+ (Figure 7);249,250 this metabolite is required in mitochondria for a series of specific biosynthetic pathways and acts also as an antioxidant.251 The NAD kinase uses not only ATP but also polyP as phosphate donor for phosphorylation of NAD+ at the 2′-hydroxyl group of the adenosine ribose moiety of the molecule.252,249

Therefore, the NAD kinase, like the ALP, belongs to a group of enzymes capable of using energy-rich polyP instead of nucleotides/ATP as a phosphate donor in phosphotransferase reactions. We propose to operationally classify this group of functionally related enzymes (e.g., ALP and NAD kinase) that catalyze the transfer of energy-rich phosphate from polyP to a substrate (e.g., AMP, ADP, or NAD+) as a polyP phosphotransferase system (PP-PTS; EC number 2.7) (Figure 6).

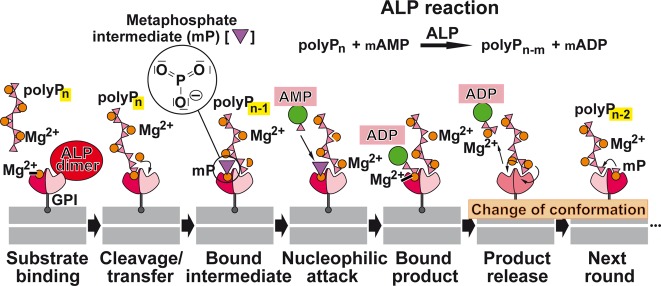

7. Alkaline Phosphatase: Role in polyP Catabolism

The major exopolyphosphatase in animals and humans, which is able to degrade long chain polyP, is the alkaline phosphatase (ALP).117 This metalloenzyme, which can also act as a phosphotransferase, can therefore be grouped into the polyP phosphotransferase system PP-PTS and is functionally active only as a dimer.253 It contains two Zn2+ ions and one Mg2+ ion in each catalytic site of the dimer; these metal ions are involved in the catalytic mechanism of the enzyme.254 We have demonstrated that the ALP degrades polyP following a processive mechanism.117 Four isozymes are known, the intestinal ALP, the placental ALP, the germ cell ALP, and the tissue-nonspecific ALP or liver/bone/kidney ALP.254 The ALP dimers are allosteric enzymes.253 Studies on the human placental ALP which only requires Zn2+ for activity revealed that this isoform, in its fully metalated form, shows the characteristics of a noncooperative allosteric enzyme; both subunits of the ALP dimer function independently, but their catalytic activity is controlled by the conformation of the respective other subunit.253 On the other hand, the tissue-nonspecific ALP (liver/bone/kidney ALP; also present in brain), which like the intestinal ALP, needs both Zn2+ and Mg2+, shows a negative cooperativity with respect to Mg2+ binding, which is relevant for the mechanism of polyP degradation, as discussed in section 13. The ALP is characterized by a broad substrate specificity. Besides polyP, the ALP hydrolyzes pyrophosphate, AMP, ADP, ATP, glucose-1-phosphate, glucose-6-phosphate, and β-glycerophosphate.

Apart from the ALP, only two other human proteins have proven to be an exopolyphosphatase. The first protein, h-prune, is characterized by a high sequence homology to PPX but preferably hydrolyzes only short-chain polyP (≤25 Pi residues).232 The second protein is the osteoclast tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP).255 This exopolyphosphatase hydrolyses, like h-prune, only shorter-chain polyP molecules; it is inhibited by long-chain polyP. On the basis of the facts that the chain length of the acidocalcisomal and platelet polyP is around 70–75 Pi units and the mammalian ALP, in contrast to h-prune and TRAP, hydrolyzes both long and short polyP molecules,117,256 it can be concluded that the ALP plays a predominant role at least in the control of long chain polyP in mammalian/human organisms. The ALP might function in close cooperation with the endopolyphosphatase described by Kumble and Kornberg.220 This enzyme which corresponds to the yeast PPN1 has been reported also to exist in mammalian tissue; it cleaves long chain polyP to polyP60 and has been partially purified from the rat brain and bovine brain.220 Unfortunately, this enzyme which might be responsible for the occurrence of polyP molecules of distinct, intermediate chain lengths during cell cycle/apoptosis has not been studied further. For example, analysis of the size of polyP in HL-60 cells revealed that both proliferating and nonproliferating cells contain two classes of polyP, long-chain polyP with a narrow size distribution of around 150 Pi residues and medium-chain polyP with 25–45 Pi residues. In apoptotic cells, the long-chain polyP but not the medium-chain polyP disappeared.257

With regard to the differential biological effects of different size classes of polyP, the processive mode of action of polyP degradation shown by ALP might be of particular importance. This mechanism allows the degradation of long polyP molecules to monomeric Pi without the intermediate release of polyP molecules of shorter, intermediate chain lengths. In this way, it is prevented that during degradation of long chain polyP shorter polyP molecules are formed with a size that might show different (possibly unwanted) activities. For example, very long polyP polymers, administered extracellularly, with chain length of ≥500, such as those present in microorganisms, have been shown to activate the contact pathway of the blood coagulation cascade, while medium size polyP molecules, with polymer lengths of about 100 phosphate units, such as those released by platelets, accelerate activation of factor V via factor Xa and thrombin and abrogate the anticoagulant function (inhibition of factor Xa) of the tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI); polyP chains with a size of ≥250 are required to enhance fibrin polymerization122 (reviewed in refs (96 and 258)).

The mechanism by which the mammalian polyP degrading enzymes recognize specific chain lengths of polyP is not known. This is in particular intriguing for exopolyphosphatases, like the ALP, because the degradation of long polyP chains begins at the ends of the polymer. In contrast to the E. coli enzyme, this, also processive, exopolyphosphatase degrades long-chain polyP, e.g. polyP750–800, without formation of any intermediary product.117 It might be possible that, like seen for the E. coli exopolyphosphatase (see above), multiple binding sites on distant portions of the enzyme proteins exist. Both enzymes are functionally active as a dimer. The affinity of the ALP to the polyP substrate increases with increasing chain length of the polymer. Measurements with low and medium chain polyP at pH 9.5 (pH 7.5) and using the enzyme from calf intestine revealed a decrease in the Km value (in terms of polymer concentration) from 187 μM (218 μM) for polyP2 to 28 μM (0.5 μM) for polyP69–95.117 This increase in affinity is paralleled by a decrease in the maximum rate of the reaction, vmax, from 1025 × 10–3 (176 × 10–3) mol min–1 mg–1 to 60 × 10–3 (2.5 × 10–3) mol min–1 mg–1, in line with the processive type of reaction catalyzed by the enzyme (increase in reaction rate in the course of the processive degradation of the polyP chain).

8. PolyP Metabolism in Eukaryotic Cells: Organelles

There are two intracellular organelles which are rich in polyP, the mitochondria and the acidocalcisomes.168 Interestingly, within eukaryotic cells, exemplarily demonstrated in the eukaryotic parasite T. brucei, these two organelles are in close contact,259 a finding that is suggestive and indicative toward a functional interaction of the acidocalcisomes with the mitochondria during regulation of cellular bioenergetics.260

8.1. Mitochondria

It has been especially the Abramov group261 that disclosed polyP metabolism being correlated with the polymer chain-length in mitochondria. Short polyP (14 Pi residues) or medium-sized polyP (∼70 Pi) increases the respiratory coefficient by activation of complex III and inhibition of complex IV, compared to the control. Simultaneously, these two classes of polyP markedly reduce the oxidative phosphorylation (ADP/O ratio). Long polyP (130 Pi) causes cell death in primary neurons and astrocytes, while medium and short polyP, again, do not elicit this effect. However, it might be considered that any kind of polyP is prone to degradation by ALP, or ALP-like enzymes, a fact which complicates a strong conclusion.117,262

A hypothetical polyP synthase has been proposed to be located in the inner membrane of the mitochondria, presumably associated with the mitochondrial ATP synthase (Figure 7).159 Complex I-linked substrates, like pyruvate, malate and glutamate or the complex II-linked substrate succinate, which stimulate mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation,263 are also activators of the mitochondrial polyP synthesis.159 Inhibition of the complex I system by Rotenone causes a drop of the polyP pool. This fact implies that alterations of the function of these complexes are correlated with the polyP level in the matrix of the mitochondria. This circuit is paralleled with a potential effect of polyP on the proton gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane (ΔpH+); at a high potential, polyP concentration increases and vice versa.168 In turn, two circuits which control the level of polyP in the mitochondria can be formulated, one linked with the individual complexes of the respiratory chain and another linked with the overall proton gradient.