Abstract

Background

Despite impressive reductions in infectious disease burden within Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), half of the top ten causes of poor health or death in SSA are communicable illnesses. With emerging and re-emerging infections affecting the region, the possibility of healthcare-acquired infections (HAIs) being transmitted to patients and healthcare workers, especially nurses, is a critical concern. Despite infection prevention and control (IPC) evidence-based practices (EBP) to minimize the transmission of HAIs, many healthcare systems in SSA are challenged to implement them. The purpose of this review is to synthesize and critique what is known about implementation strategies to promote IPC for nurses in SSA.

Methods

The databases, PubMed, Ovid/Medline, Embase, Cochrane, and CINHAL, were searched for articles with the following criteria: English language, peer-reviewed, published between 1998 and 2018, implemented in SSA, targeted nurses, and promoted IPC EBPs. Further, 6241 search results were produced and screened for eligibility to identify implementation strategies used to promote IPC for nurses in SSA. A total of 61 articles met the inclusion criteria for the final review. The articles were evaluated using the Joanna Briggs Institute’s (JBI) quality appraisal tools. Results were reported using PRISMA guidelines.

Results

Most studies were conducted in South Africa (n = 18, 30%), within the last 18 years (n = 41, 67%), and utilized a quasi-experimental design (n = 22, 36%). Few studies (n = 14, 23%) had sample populations comprising nurses only. The majority of studies focused on administrative precautions (n = 36, 59%). The most frequent implementation strategies reported were education (n = 59, 97%), quality management (n = 39, 64%), planning (n = 33, 54%), and restructure (n = 32, 53%). Penetration and feasibility were the most common outcomes measured for both EBPs and implementation strategies used to implement the EBPs. The most common MAStARI and MMAT scores were 5 (n = 19, 31%) and 50% (n = 3, 4.9%) respectively.

Conclusions

As infectious diseases, especially emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases, continue to challenge healthcare systems in SSA, nurses, the keystones to IPC practice, need to have a better understanding of which, in what combination, and in what context implementation strategies should be best utilized to ensure their safety and that of their patients. Based on the results of this review, it is clear that implementation of IPC EBPs in SSA requires additional research from an implementation science-specific perspective to promote IPC protocols for nurses in SSA.

Keywords: Infection prevention and control, Global Health, Nursing, Implementation strategies, Implementation outcomes, Sub-Saharan Africa

Background

Infectious diseases generate significant morbidity and mortality worldwide [1, 2]. Despite reductions in global prevalence over the last 20 years, a disproportionate amount of the disease burden related to infectious diseases remains in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) [3, 4]. Despite impressive reductions in infectious disease burden within SSA [3, 4], communicable illnesses (along with maternal, neonatal, and nutritional causes) comprised 61% of the disability-adjusted life year (DALY) burden in the region as of 2015 [5]. Half of the top ten causes of poor health or death in SSA are infectious diseases [2, 3]. With rapid economic, social, and geographical shifts occurring in the region [6–8], emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases are playing an increasingly important role in the burden of disease. Recent outbreaks like the Ebola viral disease (EVD) epidemics of 2014 and 2018 have highlighted the impact of infectious diseases on healthcare systems and the communities they serve. In the context of already resource-challenged health care systems, the EVD epidemic of 2014 devastated the healthcare infrastructure of three Western African countries [9], and impacted four more [10]. By April 2016, 28,616 confirmed EVD cases and 11,310 deaths were reported for the region [9]; the economic cost of the epidemic was estimated at $3.6 billion, with $2.2 billion in gross domestic product lost in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone in 2015 [9]. Similar expenditures can be observed for HIV services and care within the region: fiscal requirements for HIV therapy up to 2050 are projected to be as high as 21% and 80% of the GDPs of South Africa and Malawi respectively [11]. Currently, an EVD epidemic in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is evolving into a significant public health endeavor, leading to the second largest EVD epidemic in history, with over 500 confirmed cases [12]. Infectious diseases and the damage they can cause to patients, healthcare workers, and health systems remain among the most pressing priorities to be addressed in SSA.

Within the broader category of infectious diseases, healthcare-acquired infections (HAIs) are a major challenge. HAI rates are generally higher in low-income compared to high-income countries [13], with substantial variation across and within countries of all income levels: the cumulative incidence of HAIs ranges from 5.7 to 48.5% within African countries [14]. Traditionally defined, HAIs are infections patients acquire while receiving care in a healthcare facility [15, 16]. Yet, HAIs that impact healthcare workers providing patient care are equally important, especially nurses [17, 18]. While many different types of health care workers (i.e., laboratory technicians, physicians, water and sanitation staff) are at increased risk of acquiring infectious diseases in the healthcare setting, this study focused on nurses for the following reasons: (a) nurses have unique needs (they spend the most amount of time with patients than any other health worker [19] and operate in highly unstandardized and variable circumstances); (b) nurses are by far the largest cadre of healthcare workers in SSA (even though their needs often take second place or are lumped to those of physicians or other healthcare workers).

Two diseases, EVD and tuberculosis (TB), provide excellent exemplars of infectious diseases that disproportionately affect nurses while caring for patients. A total of 718 healthcare worker EVD infections occurred in West Africa, with 396 (55%) confirmed cases among nurses [20]. A combined cumulative incidence rate of EVD among nurses was 43.7 per 1000 in the region, compared to 29.5 and 40.4 per 1000 among physicians and laboratory technicians respectively [20]. Similarly, high rates of TB infections are observed in healthcare workers [21]. The median incidence rate of TB among healthcare workers in SSA was 3871 per 100,000 [21], making the risk of contracting TB among healthcare workers, including nurses, in SSA greater than the risk in the general population in SSA [22]. In terms of HAIs, nurses are often unduly infected, leaving significant burdens on the health system.

Inadequate adherence to infection prevention and control (IPC) standards place millions of patients and healthcare workers, especially nurses, at risk of infectious diseases worldwide, including HAIs. “IPC is a scientific approach and practical solutions to prevent harm caused by infections to patients and health workers” [23]. Effective IPC knowledge and practice are the keystones of a strong healthcare system. The causes of high HAI rates include poor environmental hygiene, inappropriate medical waste disposal, inadequate infrastructure, insufficient equipment, and poor knowledge of infection control protocols all contribute to high HAIs [13].

For example, nurses in SSA may not have enough resources, like biohazard bins or waste bags, to adequately dispose of infectious medical materials [18]. Additionally, nurses may not have access to the following: an adequate healthcare infrastructure to provide safe patient care, familiarity with IPC policies or regulations within their healthcare facilities, and knowledge of effective screening and triage practices to minimize transmission of infectious diseases entering the health facility [18]. The causes of poor IPC places nurses at increased risk of acquiring an infectious disease while serving patients; however, HAIs among healthcare workers and patients are preventable.

The World Health Organization (WHO) [24] has identified a set of evidence-based recommendations on the key components of an IPC program for a national and facility level. These IPC core components include dedicated programs with teams of specialty trained IPC professionals, guidelines, training and education, surveillance, implementation of multi-modal IPC strategies, monitoring/auditing and providing feedback, establishing requirements for workload, staffing, and bed occupancy, and ensuring that the built environment, equipment, and materials are available for IPC practices [24]. These core components are the foundation for the two different branches of IPC precautions: standard precautions and transmission-based precautions [25]. Standard precautions are the basics of the IPC precautions. Used for all patients, this branch of precautions includes hand hygiene practices, appropriate use of personal protective equipment (PPE), respiratory hygiene, appropriate patient placement, injection safety, disinfection, and medical waste disposal [26]. When implemented correctly by health workers, these precautions keep the health worker protected from infection and keep infections from spreading among patients [26]. In addition to standard precautions, the second branch of IPC precautions are transmission-based precautions [26]. The three transmission-based precautions are contact, droplet, and airborne [26]. Contact precautions are used when patients are colonized with an infectious agent and the risk of further transmission is high [26]. For some infectious agents, specialized precautions called administrative precautions are used to further control the spread of infection. Administrative precautions focus on reducing the risk of exposure to patients infected with specific infectious diseases [27]. Administrative control activities include screening, diagnosing, and treating infectious agents [27]. For example, TB is an infectious disease that requires both administrative precautions and transmission-based precautions [27]. Rapidly screening TB suspects via intensive case finding expedites patient diagnosis, which allows for therapy to be expedited as well. Once TB patients are placed on effective therapy, they are no longer infectious to others [28–30].

With sufficient resources to advance health system strengthening initiatives, prevention of infectious diseases, including HAIs, is achievable. Within the global health context, many initiatives have used strategies to incorporate IPC evidence-based practices (EBPs), like standard, transmission-based, and administrative precautions, into standard healthcare practice. Many EBPs are known for many healthcare challenges [31]. EBPs, like hand hygiene, are effective interventions known to reduce infectious agents among patients and healthcare workers [32–34]. Unfortunately, EBPs, including those for IPC, are not effectively implemented in many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) in SSA [35]. Within implementation science, a variety of implementation strategies have been used to integrate EBPs into clinical practice in LMICs. Proctor et al. [36] defines implementation strategies as “methods or techniques used to enhance the adoption, implementation, and sustainability of a clinical program or practice”. In SSA, many implementation strategies have been used to promote IPC protocols [32, 37–40]. All of these strategies have produced outcomes associated with the original EBP or the strategy utilized. Additionally, implementation outcomes measure the degree in which implementation strategies have been successfully utilized. Implementation outcomes are “the effects of deliberate and purposive action to implement new treatments, practices, and services [41]. In SSA, implementation outcomes have been measured to assess if IPC EBPs have been successfully implemented.

The Conceptual Model of Implementation Research is a framework that outlines the relationships between an EBP, implementation strategies utilized to promote the EBP, and outcomes of the implementation strategies [42]. This framework provides the conceptual underpinnings for the primary research question of this review: how are implementation strategies used to support IPC promotion for nurses in SSA. Using this model, hand hygiene, waste disposal, and correct PPE use are examples of EBPs. Trainings and stakeholder buy-in sessions are examples of implementation strategies, and number of nurses trained and number of trainings conducted are examples of implementation outcomes. Given the burden of infectious diseases in SSA, the promotion of IPC protocols for healthcare workers is critically needed. Yet, limited literature exists on how implementation strategies have been used to advance IPC, for nurses, a commonly overlooked healthcare worker cohort. To address this gap, the purpose of this review is to synthesize and critique what is known about implementation strategies to promote IPC for nurses in SSA.

Methods

Search strategy

A systematic approach was used to identify articles from the following databases: PubMed, Ovid/MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane, and CINHAL. PubMed and Ovid/MEDLINE were selected for their referencing of the biomedical literature. Embase was selected for its focus on international scholarship and a global audience. Cochrane and CINHAL were selected for their reporting on systematic reviews and nursing literature respectively. Two reviewers (AEBC, KAR) independently searched the databases using the search terms for nurses/nursing; IPC, standard precautions or transmission-based precautions; and Sub-Saharan Africa or individual countries in the region. The complete search syntax for each database are included in Additional file 1. As per the recommendations of Whittemore and Knafl [43], the reference sections of each article were reviewed for additional studies meeting eligibility criteria: a methodology known as citation indexing.

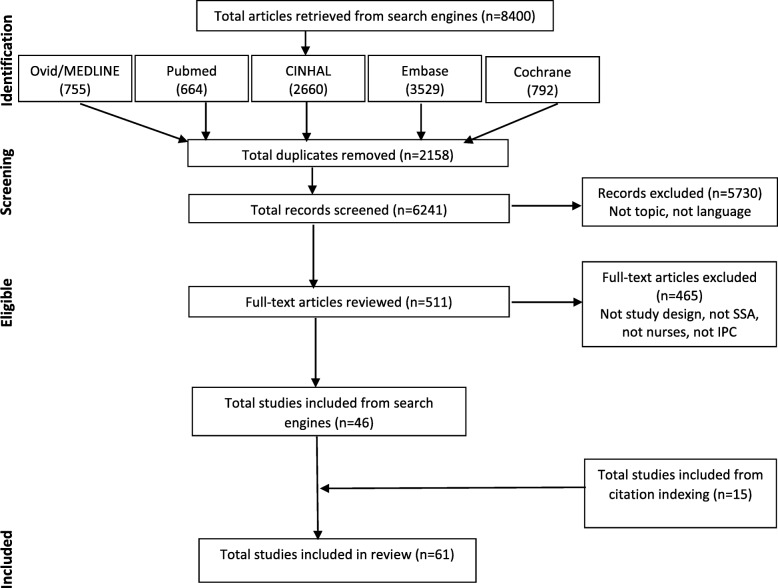

Figure 1 depicts the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram used to report study findings [44]. The protocol for this review was not registered.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for search strategy

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed to identify research that empirically evaluated or tested implementation strategies to promote IPC protocols for nurses in SSA. Studies were eligible for inclusion if written in English, peer-reviewed, published between 1998 and 2018, implemented in SSA, targeted nurses, and promoted IPC EBPs. All study designs (RCT, cross-sectional, cohort, qualitative) were eligible. Studies were excluded if they did not meet the aforementioned criteria. For example, non-empirical studies (reviews, commentaries, briefs, editorials, reports, guidelines) and studies that did not specifically evaluate or test an implementation strategy (e.g., prevalence studies, modeling studies) were excluded from this review.

Study selection and data extraction

Titles and abstracts identified in the initial search were de-duplicated and then screened using inclusion and exclusion criteria for full-text review. Citation-index searching was conducted on articles that met inclusion criteria following full-text review, and eligible articles were similarly screened. The following implementation-related data elements were extracted from studies included in the review: author, year of publication, purpose, country, study design, IPC EBPs, implementation strategies, and implementation outcomes.

For each article, implementation strategies and outcomes were categorized based on the definitions produced by Powell et al. [45] and Proctor et al. [41] respectively. Further categorization of implementation outcomes based on their association with the EBPs or implementation strategies to promote the EBPs was conducted. For example, hand hygiene is an EBP. An educational training (implementation strategy) may be provided to nurses to promote the uptake of hand hygiene practices. The outcomes of this initiative may be related to the EBP and/or to the training. An example of a possible outcome related to the above scenario for the EBP is penetration (i.e., increased number of nurses practicing hand hygiene out of total number of nurses). An example of a possible outcome associated with the implementation strategy (training) is acceptability (i.e., 95% of nurses agreed the training material on hand hygiene was good, informative, and useful). Two reviewers (AEBC, KAR) screened all articles for inclusion/exclusion. After all articles were screened and deemed to meet the inclusion criteria of the review, data extraction was then conducted by the primary reviewer (AEBC).

Quality screening

Each included article was assessed for quality using tools developed by the Johanna Briggs Institute (JBI). JBI focuses on the promotion of evidence-based practices through effective healthcare measures to a global community [46]. Implementation and translational science are key methodologies embraced and promoted by JBI [46], making these appraisal criteria particularly well-suited to the purpose and scope of this review.

JBI uses individual assessment tools for each type of study (randomized control trial, cohort, case-study, qualitative investigation, etc.) to assess quality. Study designs that had global cut-off criteria were assessed using that criteria. For studies where no global criteria existed, the reviewers established pre-determined cut-off scores before the appraisal process was initiated. Each JBI tool has specific questions addressing bias, confounding variables, statistical analyses, methodological validity, and outcome reliability [47]. Table 1 contains the quality appraisal and scoring criteria utilized in this review.

Table 1.

Quality appraisal summary and criteria

| Study design | Tool | Response options | Scoring | Cut-off score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCT [47] | MAStARI | Yes, No, Unclear, Not applicable | Yes = 1; No/Unclear/NA = 0 | 6 |

| Quasi-experimental [47] | MAStARI | Yes, No, Unclear, Not applicable | Yes = 1; No/Unclear/NA = 0 | 5 |

| Cross-sectional [47] | MAStARI | Yes, No, Unclear, Not applicable | Yes = 1; No/Unclear/NA = 0 | 5 |

| Qualitative [48] | QARI | Yes, No, Unclear, Not applicable | Yes = 1; No/Unclear/NA = 0 | 5 |

| Mixed methods [49] | MMAT | Yes, No, Cannot Tell | Yes = 1; No/Cannot Tell = 0 | 50% |

For quantitative studies, the JBI-Meta Analysis for Statistics Assessment and Review Instrument (MAStARI) was used. For qualitative studies, the JBI-Qualitative Assessment and Review Instrument (QARI) was used. For mixed methods studies, JBI does not have an appraisal tool. The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) produced by Pluye et al. [49] at McGill University was used. This tool has specific quantitative, qualitative, and integration (mixed methods) questions to assess study quality. Two reviewers (AEBC, KAR) appraised all studies for quality, and an additional reviewer (JES) appraised a random sample of 20% (n = 20) of the articles. Any discrepancy in the appraisal process was discussed by all reviewers and consensus was reached.

Results

Database and citation indexing search results

The initial database search produced 8400 results. Further, 2159 duplicates were removed. Of the 6241 studies that remained, 511 met the criteria for full-text review. Forty-six studies met the inclusion criteria. Citation indexing yielded an additional 15 studies that met the inclusion criteria. A total of 61 studies have been included in this review (see Fig. 1 for PRISMA flow diagram) [32–34, 38–40, 50–104].

Table 2 provides a summary of the individual study characteristics of the studies included in this review. Table 3 provides a table of evidence of the studies in the review. The majority of the studies were conducted in South Africa (n = 18, 30%), within the last 18 years (n = 41, 67%), and utilized a quasi-experimental design (n = 22, 36%). After South Africa, the other countries where the majority of studies were conducted were Nigeria (n = 5, 8%), Kenya (n = 4, 7%), and Zambia (n = 4, 7%). The majority of studies in this review focused on HIV (n = 24, 39%), TB (n = 6, 10%), Ebola (n = 6, 10%), or did not focus on a specific disease or infection (n = 14, 23%). The non-disease studies focused on standard precautions.

Table 2.

Study characteristics (N = 61)

| Characteristic | Number of studies (n) | Percentage of studies (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sub-Saharan country | ||

| South Africa | 18 | 29.5 |

| Nigeria | 5 | 8.2 |

| Kenya | 4 | 6.6 |

| Zambia | 4 | 6.6 |

| Rwanda | 4 | 6.6 |

| Uganda | 4 | 6.6 |

| Ethiopia | 3 | 4.9 |

| Cameroon | 3 | 4.9 |

| Tanzania | 2 | 3.3 |

| Malawi | 2 | 3.3 |

| Sierra Leone | 2 | 3.3 |

| Liberia | 2 | 3.3 |

| Mali | 1 | 1.6 |

| Sudan | 1 | 1.6 |

| Eritrea | 1 | 1.6 |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 1 | 1.6 |

| Guinea | 1 | 1.6 |

| Swaziland | 1 | 1.6 |

| Zimbabwe | 1 | 1.6 |

| Botswana | 1 | 1.6 |

| Publication date | ||

| 1998–2003 | 3 | 4.9 |

| 2004–2009 | 17 | 27.9 |

| 2010–2015 | 21 | 34.4 |

| 2015+ | 20 | 32.8 |

| Study design | ||

| RCT | 7 | 11.5 |

| Quasi-experimental | 22 | 36.1 |

| Cohort | 13 | 21.3 |

| Cross-sectional | 12 | 19.7 |

| Mixed methods | 3 | 4.9 |

| Qualitative | 3 | 4.9 |

| Multi-modal | 1 | 1.6 |

| Healthcare Workers | ||

| Healthcare workers (physicians, nurses, laboratory techs, etc.) | 47 | 77.0 |

| Nurses only | 14 | 22.9 |

| Diseases/infections | ||

| HIV | 24 | 39.3 |

| TB | 6 | 9.8 |

| Ebola | 6 | 9.8 |

| Multiple diseases | 3 | 4.9 |

| Malaria | 2 | 3.3 |

| CLABSI | 1 | 1.6 |

| VAP | 1 | 1.6 |

| SSI | 1 | 1.6 |

| Bloodborne (non- CLABSI) | 1 | 1.6 |

| STIs (non-HIV) | 1 | 1.6 |

| None (hand hygiene, disinfection focused) | 14 | 23.0 |

| Evidence-based practices | ||

| Standard Precautions | 21 | 34.4 |

| Multiple SP | 11 | 18.0 |

| Hand hygiene | 8 | 13.1 |

| Disinfection | 1 | 1.6 |

| Waste management | 1 | 1.6 |

| Transmission-based precautions | 4 | 6.6 |

| PPE | 1 | 1.6 |

| Isolation/quarantine | 1 | 1.6 |

| Immunization | 1 | 1.6 |

| Post-exposure prophylaxis | 1 | 1.6 |

| Administrative precautions | 36 | 59.0 |

| Treatment | 21 | 34.4 |

| Screening/surveillance | 11 | 18.0 |

| Diagnosis | 4 | 6.6 |

| Quality assessment score | ||

| MAStARI 4 | 1 | 1.6 |

| MAStARI 5 | 19 | 31.1 |

| MAStARI 6 | 10 | 16.4 |

| MAStARI 7 | 16 | 26.2 |

| MAStARI 8 | 5 | 8.2 |

| MAStARI 9 | 3 | 4.9 |

| MAStARI 10 | 1 | 1.6 |

| MAStARI 11 | 2 | 3.3 |

| QARI 5 | 1 | 1.6 |

| QARI 6 | 0 | 0.0 |

| QARI 7 | 1 | 1.6 |

| QARI 8 | 2 | 3.3 |

| MMAT 0% | 0 | 0.0 |

| MMAT 50% | 2 | 3.3 |

| MMAT 75% | 1 | 1.6 |

| MMAT 100% | 0 | 0.0 |

Table 3.

Table of evidence

| No. | Author/Year | Purpose | Country | Study design | Participants | Disease | EVB IPC intervention | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Allegranzi et al. [32] | To assess the feasibility and effectiveness of WHO hand hygiene improvement strategy in low-income country | Mali | Pre/Post Design | 224 Healthcare workers (# of nurses not specified) | NA | Hand hygiene/washing | MAStARI 5 |

| 2 | Brown et al. [50] | To evaluate the impact, acceptability, and feasibility of a novel toolkit to prevent HIV | Kenya | Mixed methods | 10 HCWs (2 nurses) 40 HIV Patients (20 HIV+ women; 10 discordant couples) | HIV | HIV prevention/safe conception practices associated with HIV prevention | MMAT 50% |

| 3 | Brown et al. [51] | To assess the impact of an immunization training on knowledge and practice of HCWs | Nigeria | Pre-Post experimental design/RCT study | 69 HCWs (17 were nurses/midwives/CNO) | NA | Immunization | MAStARI 9 |

| 4 | Courtenay-Quirk et al. [52] | To identify key factors in bloodborne Pathogen Exposure (BPE) incidence, report, and Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) uptake to inform the development of a multi-component intervention strategy | Botswana Zambia Tanzania | Mixed methods | HCWs (2851 for all 3 countries; # of nurses not specified) | Any blood- borne pathogen | Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) | MMAT 50% |

| 5 | Dahinten et al. [53] | To describe the implementation and feasibility of the “Pratt Pouch,” a pre-packaged ARV medicated foil package for infants born to HIV+ mothers in non-healthcare facilities | Zambia | Pre/Post Design | 41 HCWs (16 nurse, 18 community health-care workers, and 7 pharmacists) 150 HIV+ pregnant women | HIV | ART (HIV therapy) | MAStARI 7 |

| 6 | Durrheim et al. [54] | To study a novel surveillance system to address deficiencies in identifying infectious disease syndromes | South Africa | Prospective cohort study | 32 Nurses | Multiple (Polio, Cholera, Measles, Plague, Meningococcal disease, Yellow fever, Dysentery, Viral hemorrhagic fevers) | Surveillance/screening | MAStARI 8 |

| 7 | Elnour et al. [39] | To assess nursing and sanitation staff knowledge and practice regarding health care waste management | Sudan | Pre/Post Design | 200 HCWs (# of nurses not specified) 100 HCWs received training intervention; 100 HCWs were controls | NA | Waste management and proper disposal | MAStARI 9 |

| 8 | Farley et al. [55] | To develop and evaluate a nurse case management model and intervention using the tenants of the Chronic Care Model (CCM) to manage MDR-TB treatment for patients | South Africa | Pre/Post Design | 1 nurse case manager 40 MDR-TB patients | MDR-TB HIV | MDR-TB treatment/monitoring | MAStARI 5 |

| 9 | Fatti, G [56]. | To evaluate the effectiveness of a Quality Nurse Mentor (QNM) health systems strengthening intervention to improve PMTCT processes and outcomes | South Africa | Pre/Post Design | Number of nurses not directly stated All pregnant women attending material health facilities were eligible to enroll in intervention (specific #s of samples not specified) | HIV | PMTCT (HIV therapy) | MAStARI 5 |

| 10 | Gous et al. [57] | To assess the feasibility and accuracy of the implementation of a nurse-operated multiple POCT in 2 ART clinics | South Africa | Cross-sectional study | 3 Senior level nurses 793 HIV+ patients from 2 clinical sites | HIV | Point-of-care testing (POCT) | MAStARI 7 |

| 11 | Holmen et al. [58] | To improve hand hygiene (HH) compliance among physicians and nurses using the WHO’s guidelines | Rwanda | Pre/Post Design | HCWs (54 nurses; 12 physicians) | N/A | Hand hygiene (hand washing) | MAStARI 5 |

| 12 | Holmen et al. [33] | To assess the impact of hand hygiene (HH) programs aimed at improving compliance AND to identify unique challenges to HH sustainability | Rwanda | Pre/Post Design | HCWs(56 nurses; 11 physicians) | N/A | Hand hygiene (hand washing) | MAStaARI 5 |

| 13 | Howard et al. [59] | To evaluate the effectiveness and acceptability of a combination intervention package designed to improve isoniazid preventative therapy (IPT) initiation, adherence, and completion among PLHIV | Ethiopia | Mixed methods randomized cluster trial (RCT) (randomization occurred at the clinic level, not individual) | HCWs (10 nurses; 2 health officers; 9 peer educators) # of patients not specified; 10 out of 11 sites were selected for participation (patients pulled from these sites) | TB | IPT (TB therapy) | MAStARI 9 |

| 14 | Imani et al. [60] | To evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of 2 interventions: on-site support (OSS) and integrative management of infectious disease (IMID) for HCWs | Uganda | Mixed methods randomized cluster trial (RCT) (randomization occurred at the clinic level, not individual) | Mid-level professionals (including 20 nurses, 48 clinical officers, registered midwives) 2 MLP per site = 72 MLPs 687 total patients | Malaria, TB, HIV, and other childhood infectious diseases | Screening, diagnosis, therapy | MAStARI 8 |

| 15 | Jere et al. [61] | To assess the effects of a peer-to-peer intervention on rural HCWs universal precautions and client teaching | Malawi | Pre/Post Design | HCWs (clinicians, including nurses, and technicians; clinical support workers; non-clinical workers (no specific # of nurses) | HIV | Universal precautions AND HIV prevention associated with universal precautions | MAStARI 8 |

| 16 | Jones et al. [62] | To describe the educational and transcultural strategies employed to bridge the gap between IPC policy and clinical practice of HCWs | Tanzania | Qualitative study | HCWs (# nurses not specified) | NA | Standard Precautions/UP | QARI 8 |

| 17 | Jones-Konneh et al. [63] | To reveal the importance and effect of intensive education of HCWs during an Ebola (EVD) outbreak | Sierra Leone | Cross-sectional study | HCWs (# nurses not specified) | Ebola | Standard precautions and transmission- based precautions for EVD prevention | MAStARI 5 |

| 18 | Kaponda et al. [64] | To evaluate the impact of a peer group intervention on work-related knowledge and behavior on universal precautions among HCWs | Malawi | Pre/Post Design | Roughly 561 HCWs (clinicians, including nurses, and technicians; clinical support workers; non-clinical workers (no specific # of nurses) 678 Patients | HIV | Universal precautions AND HIV prevention associated with universal precautions | MAStARI 5 |

| 19 | Karari et al. [65] | To evaluate the uptake, acceptability, and effectiveness of Uliza: a telephone consultation service for HCWs | Kenya | Prospective cohort study | 296 HCWs (188 physicians, 66 nurses, 23 medical officers. 2 pharmacy technicians, and 17 other) | HIV | ART (HIV therapy) | MAStART 7 |

| 20 | Kerrigan et al. [66] | To explore the feasibility and acceptability of three active case finding strategies for TB to inform their optimal implementation in a larger, randomized, cluster trail | South Africa | Qualitative study | 25 participants (10 HCWs (# nurses not specified), 8 TB patients, and 7 family members of TB patients) | TB | TB screening/active case finding | QARI 8 |

| 21 | Kunzmann et al. [67] | To develop and implement an evidence-based bundle of care (Best Care Always) to prevent pediatric VAP | South Africa | Prospective cohort study | HCWs (doctors and nurses) (# of nurses not specified) | VAP | “Best Care Always:” an evidence- based HCAI prevention bundle | MAStARI 6 |

| 22 | Labhardt et al. [68] | To assess the availability of equipment and staff knowledge of PMTCT | Cameroon | Pre/Post Design | HCWs (no denominator provided; study states 42% were staff nurses; 40% were registered nurses; 18% care assistance among nurse-lead facilities (physicians were also included in this study) | HIV | PMTCT (HIV therapy) | MAStARI 5 |

| 23 | Levy et al. [69] | To describe a successful partnership to implement a national IPC training and PPE supply program in all Primary Health Units (PHUs) | Sierra Leone | Cross-sectional study | 4264 HCWs (# of cadres not specified) | Ebola | Standard precautions and transmission- based precautions for EVD prevention | MAStARI 6 |

| 24 | Lewin et al. [70] | To assess whether adding a training intervention for clinic staff to usual DOTS strategy for TB would affect TB treatment outcomes | South Africa | Clustered RCT (randomization occurred at the clinic level; total number of clincis-24 (with 50 patients per clinic) | HCWs (doctors, nurses, educators, clerical staff, CHWs) # of nurses not specified Roughly 1200 patients | TB | TB therapy | MAStARI 11 |

| 25 | Liautaud et al. [71] | To examine the effectiveness of a 1-year certificate program in IPC and occupational health (OH) aimed at empowering HCWs to act as change agents for improving workplace-based HIV and TB prevention | South Africa | Mixed methods | 32 HCWs (56% were nurses) | HIV TB | HIV/TB IPC | MMAT 75% |

| 26 | Liu et al. [72] | To describe the Chinese response to the Ebola epidemic in Liberia | Liberia | Cross-sectional study | HCWs (nurses, social workers, cleaners, and technicians) # nurses not specified | Ebola | Ebola ETU safe design/layout for patient isolation and infection reduction; standard precautions; transmission-based precautions | MAStARI 7 |

| 27 | Mahomed et al. [73] | To evaluate infection control in intensive care units (ICUs) using the Infection Control Assessment Tool (ICAT) | South Africa | Cross-sectional study | Nurses (# not specified) | NA | IPC Practices (including standard precautions and transmission-based precautions) | MAStARI 6 |

| 28 | Miceli et al. [74] | To describe the Integrated Infectious Disease Capacity Building Evaluation approach to integrating advances in health professional educational theory in the context of primary healthcare system | Uganda | Pre/Post Design | 72 HCWs (clinical officers, nursing officers) # of nurses not specified (36 sites total) | Infectious Diseases (emphasis on HIV, TB, and malaria) | HIV prevention/ART, TB screening/therapy, malaria screening/therapy | MAStARI 7 |

| 29 | Mbombo & Bimerew [75] | To evaluate students’ clinical performance on PMTCT competencies integrated into the standard nursing curriculum and to determine the effectiveness and relevance PMTCT training program | South Africa | Pre/Post Design | 154 student nurses | HIV | PMTCT (HIV therapy) | MAStARI 5 |

| 30 | Ogoina et al. [76] | To describe the experiences of a tertiary teaching hospital in preparing and responding to the 2014 EVD outbreak | Nigeria | Multi-modal | HCWs (70 doctors, 61 nurses, and 59 other medical staff) | Ebola | Standard precautions and transmission-based precautions for EVD prevention | MAStARI 7 QARI 7 |

| 31 | Otu et al. [77] | To assess the effect of using a tablet computer application to deliver an educational intervention to change HCWs EVD-related knowledge and attitudes | Nigeria | Pre/Post Design | 203 HCWs (94 CHWs, 26 nurses, 8 lab staff, and 75 other | Ebola | Standard precautions and transmission-based precautions for EVD prevention | MAStARI 5 |

| 32 | Parker et al. [78] | To describe the results of an evaluation of the impact of a low-cost, brief nursing intervention on the utilization of Safe Water System (SWS) and knowledge of proper hand-washing | Kenya | Pre/Post Design | 11 Nurses | NA | Safe Water System (Hand hygiene) | MAStARI 5 |

| 33 | Richards et al. [79] | To describe the implementation and impact of a bundle to reduce CLASI in the Netcare group of private hospitals | South Africa | Prospective cohort study | HCWs (# nurses not specified) | NA | “Best Care Always:” an evidence- based HCAI prevention bundle | MAStARI 7 |

| 34 | Samuel et al. [80] | To examine the feasibility of adherence to quality standards once established, with reference to hand washing practice as a measure of infection prevention | Eritrea | Qualitative study | HCWs (10 physicians, 10 nurses, 14 health assistants and support staff) 30 patients | NA | Hand hygiene (hand washing) | QARI 8 |

| 35 | Schmitz et al. [81] | To define baseline rates of HCW hand hygiene adherence and assess the impact of implementing the WHO Multi-modal Hand Hygiene Strategy at an academic hospital | Ethiopia | Pre/Post Design | 1000 HCWs (505 physicians, 291 medical students, 144 nurses, and 60 other) | NA | Hand hygiene/washing | MAStARI 5 |

| 36 | Shumbusho et al. [82] | To evaluate the results of a pilot program of nurse-centered ART | Rwanda | Retrospective cohort study | 3 Nurses (at 3 health centers) | HIV | ART (HIV therapy) | MAStART 7 |

| 37 | Speare et al. [83] | To describe the results of a training strategy for communicable disease control nurses | South Africa | Cross-sectional study | 20 Nurses | NA | Surveillance/screening | MAStARI 6 |

| 38 | Tillerkeratne et al. [84] | To determine whether a multi-faceted intervention targeting health care personnel would reduce CAUTI rate in a public hospital | Kenya | Pre/Post Design | Roughly 44 HCWs (nurses and clinical officers) # nurses not specified | NA | CAUTI Infection Prevention and Control | MARtARI 5 |

| 39 | Uneke et al. [34] | To promote the adoption of the WHO HH guidelines to enhance compliance among doctors and nurses and improve patient safety in a teaching hospital | Nigeria | Cross-sectional study | 202 HCWs (39 physicians and 163 nurses) | NA | Hand hygiene/washing | MAStARI 6 |

| 40 | Uneke et al. [85] | To assess the impact of a stethoscope disinfection campaign among doctors and nurses | Nigeria | Pre/Post Design | HCWs (39 physicians and 163 nurses) | NA | Disinfection (of medical equipment) | MAStARI 5 |

| 41 | Van Rie et al. [86] | To evaluate the implementation of three models of provider-initiated HIV counseling and testing for TB patients | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Cross-sectional study | 10 HCWs (6 research nurses, 2 VCT staff, 1 counselor/nurse, 1 TB nurse (1238 patients at 3 TB clinics) | HIV TB | HIV Counseling/Testing AND TB Prophylaxis | MAStARI 7 |

| 42 | Wanyu et al. [87] | To describe the introduction, successes, and challenges implementing a PMTCT program using trained birth attendants | Cameroon | Cross-sectional study | 30 Trained Birth Attendants (42 mother-newborn dyads) | HIV | PMTCT (HIV therapy) | MAStARI 7 |

| 43 | Welty et al. [88] | To describe how the Cameroon Baptist Convention Health Board (CBHHB) successfully integrated PMTCT into routine antenatal care | Cameroon | Cross-sectional study | 690 Nurse, midwives, nurse aids, and trained birth attendants | HIV | PMTCT (HIV therapy) | MAStARI 7 |

| 44 | White et al. [89] | To evaluate three different methods of checklist training by assessing change in behavior at 3–6 months post training on the WHO Surgical safety checklist | Guinea | Cross-sectional study | HCWs (4 surgeons, 7 anesthetists, and 2 ward nurses) | NA | IPC Practices during surgeries (disinfection of equipment, decontamination of equipment, disinfection of environment) | MAStARI 6 |

| 45 | Xi et al. [90] | To investigate the importance of supervision through video surveillance in improving the quality of personal protection in preparing health care workers working in Ebola treatment units | Liberia | Cross sectional study | HCWs (23 physicians; 8 nurses) | Ebola | PPE use | MAStARI 7 |

| 46 | Zaeh et al. [91] | To evaluate the impact of a cost-effective quality improvement intervention targeting active TB cases and provision of IPT among those without active TB disease | Ethiopia | Pre/Post Design | 4 HCWs (2 physicians; 2 nurses) 751 HIV+ patients | HIV TB | TB screening/IPT Prophylaxis | MAStARI 5 |

| 47 | *Bedelu et al. [92] | To describe how the integration of HIV care and treatment into primary health care in Lusikisiki overcome some of the challenges of working in a resource-limited rural area, to achieve good treatment outcomes and clinical outcomes | South Africa | Prospective cohort study | HCWs (nurses and community health workers) (# of nurses not specified) 2200 patients | HIV | ART (HIV therapy) | MAStARI 7 |

| 48 | Elden et al. [38] | To implement and evaluate a program of intensive case finding for TB into a high HIV prevalence, low resource, rural setting | Swaziland | Prospective cohort study | HCWs (nurses and HIV counselors) (# of nurses not specified) 1467 HIV patients | TB | TB screening/intensive case finding | MAStARI 6 |

| 49 | Charalambous et al. [93] | To evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of a specialist clinical service for HIV-infected mineworkers | South Africa | Prospective cohort study | HCWs (physicians, nurses) (3 nurses) 1773 patients | HIV TB | ART (HIV therapy) TB screening/INH therapy | MAStARI 6 |

| 50 | Fairall et al. [40] | To assess the effects on mortality, viral suppression, and other health outcomes and quality indicators of the Streamlining Tasks and Roles to Expand Treatment and Care for HIV (STRETCH) program | South Africa | Clustered RCT (randomization occurred at the clinic level; total number of clincis-31 | 103 nurses (this number represents the number of nurses trained in the intervention group) | HIV | ART (HIV therapy) | MAStARI 10 |

| 51 | Harrison et al. [94] | To evaluate the implementation of syndrome packets and healthcare worker training of sexually-transmitted diseases | South Africa | Clustered RCT (randomized at the clinic level; total of 10 clinics) | 5 nurses (one from each intervention clinic) | Sexually- transmitted diseases | STD Syndromic case management | MAStARI 11 |

| 52 | Naidoo et al. [95] | To measure knowledge changes among HCWs who participated in a TB training program and make recommendations for future TB trainings | South Africa | Pre/Post Design | 267 HCWs (physicians, nurses, and other HCWs) (171 nurses, # of physicians or other HCWs not specified) | TB | TB diagnosis, treatment, and treatment monitoring | MAStARI 5 |

| 53 | Morris et al. [96] | To describe experiences with task-shifting in Lusaka in a large public sector ART program | Zambia | Prospective cohort study | HCWs (Clinical officers, which practice as NPs, nurses, and peer educators) 71,000 patients | HIV | ART (HIV therapy) | MAStARI 6 |

| 54 | Perez et al. [97] | To report on activities and lessons learned during the first 18-months of a rural program of PMTCT of HIV | Zimbabwe | Prospective cohort study | 20 nurses and midwives 2308 patients | HIV | PMTCT (HIV therapy) | MAStARI 7 |

| 55 | Sanne et al. [98] | To assess the efficacy of “doctor-initiated-nurse-monitored” ART to doctor-initiated-doctor-monitored” ART using a composite endpoint reflecting both treatment outcomes and patient management | South Africa | RCT | HCWs (2 physicians, 2 nurses) (812 patients) | HIV | ART (HIV therapy) | MAStART 7 |

| 56 | Ssekabira et al. [99] | To evaluate the impact of a training on the quality case management in 8 health facilities roughly one-year after the implementation of artemether-lumefantrine as a recommended 1st-line treatment regimen | Uganda | Pre/Post Design | 170 HCWs at 8 sites (each site had 1 MO, 2 CO, 5 nurses, 5 midwives, 4 nursing assistants, 1 dental officer, 1 lab tech, 1 lab assistant, 1 records officer, 1 educator, 1 health assistant) (Roughly 112 nurses) 76,705 patients | Malaria | Malaria screening, diagnosis, treatment | MAStART 5 |

| 57 | Sserwanga et al. [100] | To describe the impact of a sentinel site malaria surveillance system promoting laboratory testing and rational antimalarial drug use | Uganda | Prospective cohort study | HCWs AT 6 sites (each site had 1 MO, 2 CO, 5 nurses, 5 midwives, 4 nursing assistants, 1 dental officer, 1 lab tech, 1 lab assistant, 1 records officer, 1 educator, 1 health assistant) (Roughly 84 nurses) 424,701 patients | Malaria | Malaria screening/surveillance/ intensive case finding | MAStARI 7 |

| 58 | Stringer et al. [101] | To report the feasibility and early outcomes of scaling up an ART program | Zambia | Prospective cohort study | HCWs (# nurses not specified) 21,755 patients | HIV | ART (HIV therapy) | MAStARI 8 |

| 59 | Umulisa et al. [102] | To describe a multi-strategy intervention with a focus on ensuring stable water supply to improve hand hygiene compliance in a district hospital | Rwanda | Pre/Post Design | HCWs (physicians, nurses, student nurses) | NA | Hand hygiene/washing | MAStARI 5 |

| 60 | Driessche et al. [103] | To develop and evaluate training materials for provider-initiated HIV counseling, testing, prevention involved in care of patients with TB at the primary health care clinic level | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Pre/Post Design | 65 HCWs completed post-test assessment (7 physicians, 38 nurses; 16 lab techs, 4 district supervisors) | HIV | HIV Counseling/Testing AND TB testing/therapy | MAStARI 5 |

| 61 | Workneh et al. [104] | To report on the effectiveness of a clinical mentoring program at decentralized ART sites dedicated to promoting the scale-up of quality pediatric HIV care and treatment | Botswana | Retrospective cohort study |

HCWs (physicians, nurses) (# of nurses not specified) 374 patient charts |

HIV | ART (HIV therapy) | MAStARI 6 |

Healthcare worker cadres

This review was conducted to investigate what is known about implementation strategies utilized to promote IPC protocols for nurses. Forty-seven (77%) studies included healthcare worker samples, including physicians, pharmacists, laboratory technicians, nurse aids, trained birth attendants, residents, and nurses. Fewer studies (n = 14, 23%) had sample populations comprising nurses only.

IPC evidence-based practices

A variety of EBPs were represented in this review. The majority of studies focused on administrative precautions (n = 36, 59%). Standard precautions and transmission-based precautions represented forty-one (34%) and four (7%) studies respectively. Among the administrative precautions, treatment was the most frequently reported EBP (n = 21, 34%), followed by screening (n = 11, 18%) and diagnosis (n = 4, 7%). Studies focusing on HIV treatment or TB screening comprised the majority of studies in this section.

Only four (6%) studies focused on transmission-based precautions. Each study reported on a unique precaution. Transmission-based studies focused on correct PPE use, appropriate patient placement, immunization, and post-exposure prophylaxis.

Studies that addressed standard precautions did so by incorporating multiple precautions (n = 11, 18%) or focused on hand hygiene only (n = 8, 13%). Other studies that focused on standard precautions addressed medical equipment disinfection or appropriate waste management.

Implementation strategies

The most frequent implementation strategies used to promote IPC protocols in included studies were education (n = 59, 97%), quality management (n = 39, 64%), planning (n = 33, 54%), and restructure (n = 32, 53%). A variety of educational strategies were used to promote IPC protocols for nurses. Strategies used included didactic lectures, simulations, on-site mentorship, visual reminders, and demonstrations. Quality management strategies generally consisted of audit and feedback sessions provided to nurses in real time to promote the uptake of an IPC EBP. Planning strategies consisted of collaborations, partnerships, or buy-in sessions that were established at a higher administrative level for nurse IPC involvement. Planning strategies were mostly utilized in conjunction with other strategies. For example, a partnership between the government of a country and an academic institution may be formalized to provide nurses training or mentorship on IPC protocols. Planning strategies were also used to inquire about nurses’ experiences with IPC EBPs. A variety of restructure strategies were used to promote IPC. Nurses may be task-shifted to include IPC activities within their scope of work, provided additional resources (i.e., alcohol-based hand gel) to make adhering to IPC protocols easier, or promoted to a higher nursing position whereby IPC became the focus of the new role. Only eight (n = 8, 13%) studies used financing incentives to promote IPC protocols among nurses. When used, a financial strategy was generally associated with external funders providing resources to initiate an EBP intervention or providing over-time compensation to healthcare workers. For example, the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation, the Axios Foundation, and the Boehringer Ingleheim Pharmaceutical Company provided funds to initiate an antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation program for HIV patients in Cameroon [88]. Zero (0%) policy strategies were used.

An exhaustive list of implementation strategies is provided for each study in Table 4. Bolded strategies targeted nurses. In order to be included in this review, studies needed to report the use of implementation strategies for nurses. Many studies used implementation strategies that targeted patients, non-nurse healthcare workers, or aspects of the healthcare system. Few studies used implementation strategies solely for nurses. A summary of implementation strategies used for nurses and non-nurses (i.e., patients or a healthcare system-specific matter) is provided in Table 5. Most studies used education (n = 58, 95%) for nurses; a drastic contrast to the number of studies that used education (n = 1, 2%) for non-nurses. Other discordant results between strategies used for nurses compared to strategies used for non-nurses included planning, restructure, and finance. These strategies were used more for non-nurses than nurses. Twenty-one (34%), 25 (41%), and six (10%) studies used planning, restructure, and finance strategies respectively for non-nurses. Planning, restructure, and finance were used in 12 (20%), seven (12%), and two (3%) studies respectively for nurses.

Table 4.

List of Implementation Strategies and Outcomes Produced in each Study (n = 61)

| No. | Author/ Year | EVB IPC intervention | Implementation strategy* | Implementation outcome for the EBP* | Implementation outcome for the Implementation strategy* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Allegranzi et al. [32] | Hand hygiene/washing |

1. PLAN: (conducted local consensus discussions with senior managers, WHO staff, ward staff, pharmacists; recruit, designate, trained for leadership-task-shifted roles of hospital staff; assess for readiness and identified barriers, conducted needs assessment) 2. RESTRUCTURE: (revise profession roles—pharmacist became study coordinator and an additional pharmacist and medical student became trainers; change physical structure and equipment—supplied hand-rub to HCWs) 3. EDUCATE: (training on HH, distributed educational materials; made training dynamic—slide show, training film, and presentations) 4. FINANCIAL (fund and contract for clinical innovation—hand rub production) 5. QUALITY MGMT: (audit and provide feedback to HCWs) |

1. FEASIBILITY: Reduction in HAI from baseline (18.7%) to follow-up (15.3%) (p = .453) observed using the WHO HH toolkit |

1. FEASIBILITY: WHO HH improvement strategy was successfully implemented 2. COST: Economic production of alcohol hand rub was produced 3. PENETRATION: 224 HCWs were trained 4. ACCEPTIBILITY: HCW perceptions on some HH indicators improved (i.e. system change, education, providing feedback, etc.) |

| 2 | Brown et al. [50] | HIV prevention/safe conception practices associated with HIV prevention | 1. EDUCATE: (Development of educational materials, HIV counseling guide, counseling messages to prevent HIV, brochures for HIV couples on safe conception practices and avoidance of HIV infection; Educational materials were distributed to providers and patients; Training was given to providers on all developed materials and on how to best counsel patients) |

1. ACCEPTIBILITY: self- reported provider confidence in HIV/safer conception counseling and testing 2. FEASIBILITY: Providers stated that integrating counseling into HIV patient care was doable 3. SUSTAINABILITY: Increased confidence in HIV prevention/safe conception knowledge/practice sustained three weeks post-training (self-reported by providers) |

1. PENETRATION: After counseling, patients (74%) were able to identify HIV treatment and viral suppression as effective strategies for safer contraception compared to pre-counseling (33%); Pre-training, only 10% of providers could identify the fertile period during a women’s menstrual cycle compared to 70% post-training; Pre training, only 66% of providers could identify safer contraception strategies to prevent HIV compared to 100% post-training; 116 potential participants screened to enroll in intervention—response rate for those who agreed to enroll was 42% for discordant couples, 34% for HIV+ women, and 100% for HCWs; No lost to follow-up among HCWs or patients 2. APPROPRIATENESS: self-report from HCWs that educational toolkit materials are culturally appropriate |

| 3 | Brown et al. [51] | Immunization | 1. EDUCATE: (conduct training, make training dynamic: used PP, pictures, demonstrations, videos, and group discussions) | None |

1. PENETRATION: 69 eligible HCWs could have participated in study; 69 did participate in study; 1 HCW was lost to follow-up; knowledge of HCWs increased immediately after the intervention, but then declined at 3 and 6 months; For the intervention group, overall knowledge scores increased significantly compared to non-intervention counterpart scores (p < .001) 2. FEASIBILITY: Factors identified as influencing HCW knowledge were assessed |

| 4 | Courtenay-Quirk et al. [52] | Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) |

1. PLAN: (stakeholder buy-in and information sessions; visit different sites in the 3 countries; conducted an assessment of PEP barriers and BPE rates) 2. EDUCATE: (conducted training sessions on PEP; educational materials were distributed through the healthcare facilities)-posters, calendars, key chains 3. QUALITY MGMT: (update PEP operational plans) |

1. FEASIBILITY: Formative research conducted at 9 health facilities prior to intervention to access potential challenges/barriers to PEP implementation; Factors hindering PEP were identified; BPE rates were high in HCWs, yet under-reported; PEP management not sufficient given low report of BPE incidences; Within the last 6 months, roughly 2073 (69%) of HCWs stated having a BPE. Of these HCWs who stated having a BPE, roughly 35.6% were not reported. |

1. PENETRATION: (number of HCWs who attended training (n-2852)/compared to total HCWs who could have attended the training N = 4667) 2. APPROPRIATENESS: (HCW and healthcare management stated that tailoring each intervention to specific facility needs, HCW cadres needs, or messaging needs to be incorporated into intervention |

| 5 | Dahinten et al. [53] | ART (HIV therapy) | 1. EDUCATE: (trained HCWs on “Pratt pouch”) |

1. ADOPTION: (Pratt pouch was often used as a “bridge” until women could get to a healthcare facility, such that 73% of mothers used at least 3 pouches and 88% of mothers used less than 7 pouches; 2. FEASIBILITY: 90% of women who gave birth at home were able to use the Pratt pouch within three days of delivery 3. ACCEPTIBILITY: (26/30 mothers who gave birth at home stated that the pouch was easy to use or understanding the instructions of the pouch) 4. PENETRATION: Pratt pouch increased access to ARVs went from 35% to 94% (p < 05); 169 HIV+ pregnant women were surveyed. Of which, 160 enrolled in study) |

1. PENETRATION: 41 HCWs from 8 different facilities were trained 2. SUSTAINABILITY: Three months after training, 8 nurses and 11 community-health workers were re-assessed and training knowledge was identified as retained |

| 6 | Durrheim et al. [54] | Surveillance/screening |

1. PLAN: (stakeholder buy-in on surveillance system) 2. EDUCATE (develop effective educational materials (manual/training materials), trainings, and create a learning collaborative for nurses) 3. QUALITY MGMT: (audit and feedback-assessment for flaccid paralysis from hospital records, develop and organize quality monitoring systems for the surveillance system) 4. RESTRUCTURE: (Revise professional roles-nurses involved in active surveillance) |

1. FIDELITY: During two year period, 14 cases of meningococcal disease occurred. All but one was notified and contained within 48-h period | 1. SUSTAINABILITY: monthly meetings among nurses, networking, and feedback were identified as important mechanisms keeping the surveillance system on-going |

| 7 | Elnour et al. [39] | Waste management and proper disposal | 1. EDUCATE: (training for HCWs on proper waste management; made training dynamic—used PP, group discussions, videos, demos, and health talks) | 1. PENETRATION: Within the intervention group, self-reported practices (among those reporting good practice) rose from 42% to 55%. Similar increases in practice were self-reported for waste management practice indicators collected (ie safe waste separation) | None |

| 8 | Farley et al. [55] | MDR-TB treatment/monitoring |

1. PLAN: (assessed for readiness via a SWOT analysis to identify strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats in the current MDR-TB and HIV treatment model; Recruited, designated, and trained for leadership—one nurse case manager; Developed a formal implementation blueprint using the PRECEDE-PROCEED model; Conducted educational and ecological assessment, as well as, administrative and policy assessments for intervention 2. RESTRUCTURE: (revised professional roles via the introduction of nurse case manager role) 3. EDUCATE: (trained case manager on 6 proximal outcomes of interest associated with MDR-TB treatment management) |

1. ADOPTION: 40 MDR-TB patients enrolled in the intervention and followed for the 6-month intervention period (aka to be followed by the nurse case manage 2. PENETRATION: 24% increased occurred between Cotrimoxazole preventative therapy at baseline to post-intervention; Active surveillance for adverse drug reactions increased by 75% from baseline to post-intervention. |

1. PENETRATION: No lost to follow-up during 6-month intervention period of 40 patients; In terms of MDR-TB and HIV medical record concordance, nurse case manager identified 44% of the documented ART regimens were discordant between the medical records at baseline compared to post-intervention concordance, which was 100% between MDR-TB and HIV medical records |

| 9 | Fatti, G [56]. | PMTCT (HIV therapy) |

1. RESTRUCTURE: (revise professional roles via the use of a quality nurse mentor—whose responsibility is to build staff capacity and clinical management skills, ensure proper application of PMTCT guidelines) 2. QUALITY MGMT: (visit sites every two weeks and audit patient records with facility registers; address any data gaps, conduct re-fresher trainings for nurses if gaps exist) |

1. PENETRATION: Estimated HIV testing in children increased 2-fold: 12.4% to 22.9% (p < 0001) Proportion of infant tested for HIV 6-weeks after birth increased: 68.7% to 76.7%(p < .0001); Repeat HIV testing at 32 weeks went from 38.5% to 46.4% (p < .0001); Zudovidine uptake increased from 80.9% to 88.1% (p < .0001); Of 27,458 pregnant women who could have been included in intervention, 4981 (18%) were included | 1. PENETRATION: Nurse restructuring and quality management activities were introduced into 31 sites |

| 10 | Gous et al. [57] | Point-of-care testing (POCT) |

1. EDUCATE: (senior level nurses trained how to use and evaluate POCT devices) 2. RESTRUCTURE: (senior level nurses at 2 clinic facilities are asked to task-shift duties to include POCT; new POCT devices are introduced into clinical system) 3. QUALITY MGMT: (POCT verification processes were undertaken through the study; Laboratory confirmation of POCT tests was also performed) |

1. ACCEPTIBILITY: Nurses stated no difficulties in in performing POCT 2. FEASIBILITY: 70% of patients required 3+ POCT; On average, if CD4 counts were needed for the POCT, testing took roughly 1 h and 47 min; If CD4 was not needed, for 3 tests was 6 min; A total of 6% and 4.3% error rates for the POCT platforms were obtained in the two study sites |

1. PENETRATION: 793 HIV+ patients were asked to enroll and 793 did 2. ACCEPTIBILITY: nurses stated a preference for quick reference charts as quick aids over longer training sessions 3. FEASIBILITY: POCT was implemented into 2 ART clinics; All POCT platforms passed verification; POCT did add to nurses’ already busy scope of practice |

| 11 | Holmen et al. [58] | Hand hygiene (hand washing) |

1. PLAN: (stake holder buy-in established prior to intervention roll-out with hospital leadership; Ensuring procurement of alcohol hand rub both for HCWs and patient rooms in facility) 2. EDUCATE: (nurses and physicians attended HH training; posters and educational materials were placed in facility wards) 3. RESTRUCTURE: (providing HCWs personal alcohol hand rub) 4. QUALITY MGMT: (pre- intervention HH quality assessment via observations; audit and feedback given to facility administrators on HH compliance among HCWs post-intervention) |

1. FIDELITY: Disparities among HH existed for both nurses and physicians pre-/post- intervention, with physicians being more compliant than nurses | 1. PENETRATION: (9 out of 12 physicians and 54 out of 54 nurses attended the HH training: Knowledge increased among HCWs from 41.3% at baseline to 78.45(p < .001) post-intervention |

| 12 | Holmen et al. [33] | Hand hygiene (hand washing) | 1. QUALITY MGMT: (purposeful re-examination of the HH intervention by conducting another post-intervention assessment via HH observation and interviews among nurses and physicians; performed audit/observation assessment of medical and nursing students in 2016) | 1. SUSTAINABIITY: (Among all HCWs, HH compliance declined from the 2015 assessment to the current 2016 assessment from 68.9% to 36.8%(p < .001); Nurse-specific compliance decreased by 20.8%; physician compliance was reduced in 4/5 HH indications, nurse compliance reduced in 2/5; Similar to 2015, physician compliance was higher than nurse compliance, however, the difference had decreased by 9.7%; In 2016 assessment, there was no difference in HH compliance between medical or nursing students | 1. FEASIBILITY: Production of alcohol hand gel that was provided to HCWs in 2015 assessment was no longer being made by the local pharmacist and distributed to HCWs |

| 13 | Howard et al. [59] | IPT (TB therapy) |

1. PLAN: (engaged local government stakeholders before study to gain feedback and buy-in on intervention) 2. EDUCATE: (trained nurses on IPC protocols; distributed educational materials throughout clinics as reminders of IPC protocols) 3. RESTRUCTURE: (introduced new tools to capture patient data, such as a Family Care Enrollment form to screen family members for TB/HIV; Patients were reimbursed for clinic visits, provided mobile phones, airtime, and sent reminder SMS messages to them) 4. QUALITY MGMT: (tools were developed for intervention monitoring) |

1. ADOPTION: IPT initiation rates 2. PENETRATION: IPT completion rates; IPT adherence rates; ART adherence rates; changes in CD4 counts; retention in HIV care |

1. ACCEPTABILITY: Majority of patients and HCWs stated that IPT combination intervention was agreeable |

| 14 | Imani et al. [60] | Screening, diagnosis, therapy |

1. EDUCATE: (trained HCWs on childhood infectious diseases: TB, HIV, malaria, and others, specifically on the diagnosis and therapy components of these diseases 2. QUALITY MGMT: (on-site supervision was provided for 9-months to HCWs, whereby mentorship and extra training were provided) |

1. FEASIBILITY: Relative risk ratios comparing intervention to control relative risk showed no difference in improvements in screening, diagnosis, and therapy initiation | None |

| 15 | Jere et al. [61] | Universal precautions AND HIV prevention associated with universal precautions |

1. EDUCATE: (provided training for HCWs on universal precautions and HIV preventions; trainings were made dynamic in that they incorporated rehearsal of key skills with feedback) 2. QUALITY MGMT: (developed tools for intervention monitoring, which included pre-/post- assessments and observations |

None | 1. FEASIBILITY: At baseline, overall universal precautions knowledge was higher in the control group |

| 16 | Jones et al. [62] | Standard Precautions/UP |

1. PLAN: (a collaboration of stake- holders was established between the MOH and the Global Health Alliance of Western Australia (GHAWA) to better understand why clinical practice had not changed among HCWs after an infectious disease training; An IPC needs assessment was performed by GHAWA; conducted healthcare facility visits to gain a sense of IPC challenges and cultural contexts) 2. EDUCATE: (developed an IPC course to fill in some of the gaps from previous courses/trainings; received stakeholder feedback and modified the course based on local context; training was made dynamic via role-plays and Glitterbug!) |

1. FEASIBILITY: Health facilities lacked running water, lack of resources, storage for IPC materials | 1. ACCEPTABILITY: HCWs reported they thought the training was useful and informative |

| 17 | Jones-Konneh et al. [63] | Standard precautions and transmission- based precautions for EVD prevention |

1. PLAN: (a collaboration of stake-holders was established to be able to cover all training needs, partners included: IOM, COMHAS, MOH, and RSLAF 2. EDUCATE: (HCWs were trained on the relevant standard precautions and transmission-based precautions to provide patient care and to maintain their own safety; Training was made dynamic—mock ETU were used, skills stations, clinical cases, and lectures) |

None |

1. PENETRATION: 6206 HCWs were trained 2. FEASIBILITY: Anxiety associated with providing care to EVD patients decreased after training |

| 18 | Kaponda et al. [64] | Universal precautions AND HIV prevention associated with universal precautions |

1. EDUCATE: (provided training for HCWs on universal precautions and HIV preventions; trainings were made dynamic in that they incorporated rehearsal of key skills with feedback) 2. QUALITY MGMT: (developed tools for intervention monitoring, which included pre-/post- assessments and observations |

None | 1. ACCEPTABILITY: HIV patients were asked about if HCWs had discussed any of the training materials with them AND how they felt about the material delivered; At baseline, only 28% of HCWs had discussed HIV prevention with patients compared to37% post-intervention(p < .01) |

| 19 | Karari et al. [65] | ART (HIV therapy) |

1. PLAN: (established an academic partnership to initiate Uliza; a publicity meeting was conducted introducing Uliza to HCWs) 2. EDUCATE: (promoting Uliza vai educational sessions to HCWs) 3. QUALITY MGMT: (reminded HCWs of Uliza via text messages; introduced Uliza: telephone consultation service to improve HIV care/ART; tools/surveys developed to evaluate the implementation of Uliza; chart audits at healthcare facilities were reviewed to assess if Uliza advice was actually implemented by HCWs) |

None |

1. PENETRATION: 296 calls from 79 different HCWs used Uliza within the first year of its implementation; 58.4% of HCWs made 2+ calls; 69% of calls came from district hospitals or healthcare centers 2. ACCEPTABILITY: Among users of Uliza, all most all (94+%) agreed that the service helped them with providing better patient care, met their expectations, convenient, and timely. 3. FEASIBILITY: two important barriers to implementation success: cell phone coverage in certain rural areas, and delayed response from Uliza consultants; Nonusers stated they did not use the service because they did not know about it, did not have questions, or used other resource materials available to them |

| 20 | Kerrigan et al. [66] | TB screening/active case finding | 1. PLAN: (Focus group discussions and in-depth interviews with key stakeholders (HCWs, patients, and family members) was performed to identify which active case finding method for TB (clinic-based, home-based, or incentive-based) would be the best option for a future trial) | None |

1. ACCEPTABILITY: All study participants stated the all three strategies would be acceptable, yet each method had its pros and cons, and some methods may be better targeted to specific patient populations. For example, patients stated clinic-based methods were generally acceptable and not out of the ordinary, however, they want to ensure patients were not being stigmatized. Thus, they suggested that ALL patients (not just some patients, like HIV+) be screened; HCWs stated they favored incentive-based system best 2. FEASIBILITY: Clinic costs and transportation times were also listed as issues that might inhibit this strategy’s successful implementation; Some TB patients stated they liked the home-based method better, as it allowed patients to feel more comfortable, less costs, but it did have the potential to create stigma; In terms of the material-based method, many participants stated food and money were good incentives, yet they questioned if the government would be able to implement this form of incentive system. Additional concerns related to this method were around if this method was sustainable. |

| 21 | Kunzmann et al. [67] | “Best Care Always:” an evidence- based HCAI prevention bundle |

1. PLAN: (consensus from local stakeholders agreed that a VAP bundle needed to be implemented on PICUs) 2. RESTRUCTURE: (task-shifting via the creation of a “VAP champion” role for nurses; nurse teams of 5 members were created to implement the VAP bundle; doctors required to complete VAP identification screening form; VAP Coordinator position was created) 3. EDUCATE: (all staff involved in the implementation of the VAP bundle were trained on the bundle; one-to-one teaching sessions occurred between VAP Coordinator and nursing staff; educational materials were made available throughout the PICU) 4. QUALITY MGMT: (new tool adapted to screen for VAP; regularly VAP monitoring for VAP introduced) |

None |

1. ACCEPTABILITY; Full-time VAP Coordinator, whose duties would not be clinical, was well received by healthcare facility administration (this newly created position would not cause senior nursing staff to be pulled away from the bedside) 2. FEASIBILITY: Initial implementation of VAP bundle was not successful; Resources shortages, limited number of nurses all contributed to implementation challenges; Upon initial implementation, many challenges arose that required changing the implementation approach of the VAP bundle intervention. For example, within first 4 months, data collection was unreliable, compliance low, 5-member nurse team had little time to teach and monitor staff on bundle, resistance from nurse staff in wanting to implement the VAP bundle, and PICU team buy-in was challenging-no sense of urgency to change 3. SUSTAINABILITY: After the VAP Coordinator position was eliminated, the intervention continued for 3 months |

| 22 | Labhardt et al. [68] | PMTCT (HIV therapy) |

1. RESTRUCTURE: (HIV kits, pocket guides for HIV ART distributed to 70 health care facilities) 2. QUALITY MGMT: (Throughout study, HIV kit inventories were captured; staff knowledge was assessed on ART; Senior nurses developed an inventory tracking tool for ART resources at the facility level) 3. EDUCATE: (HCWs were provided HIV/ART training, training was made dynamic via the use of lectures, demonstrations, teach-backs, interactive plenary sessions; on-site supervision occurred after training as well) |

None |

1. PENETRATION: HIV materials to deliver ART was distributed to 70 facilities; (44 healthcare facilities (63%) contained full equipment for HIV testing; 16 (23%) had stocked PMTCT drugs; Only 14 (20%) had both 2. FEASIBILITY: Physicians confirmed that PMTCT drugs had reached district-level facilities; yet materials and funds for training had not |

| 23 | Levy et al. [69] | Standard precautions and transmission- based precautions for EVD prevention |

1. PLAN: (coalition established between MOH and CDC, NGOs; some partners procured PPE, others organized logistics associated with training in the district PHUs) 2. EDUCATE: (IPC curriculum, training materials, and health promotion materials were produced; on-site PHU training occurred for all staff; Train-the-trainer strategy used to educate staff in 1200 PHUs nationwide) 3. COST: (funding for intervention strategies was provided from a variety of international, external sources) 4. QUALITY MGMT: (district teams performed initial PHU assessments, made recommendations, and returned a week later to perform quantitative assessment of the PHU; Additional feedback and training was provided at this time) |

None | 1. PENETRATION: 4264 HCWs trained in 14 districts; over 94% of PHUS received training/PPE supplies |

| 24 | Lewin et al. [70] | TB therapy | 1. EDUCATE: (training materials produced that incorporated a lot of staff self-reflection on TB care, addressing barriers to care, and empowering staff to implement system changes; training on the newly produced materials was carried out) | 1. PENETRATION: rates for successful completion of treatment improved more in the intervention clinics than in the control clinics, yet these differences were not statistically significant) |

1. FEASIBILITY: Training was successfully conducted in all clinics, except for 1; complete pre-and post-intervention data were obtained for all clinics, except 1; all clinic-based records matched 100% of the laboratory records 2. ACCEPTIBILITY: Clinic staff stated that they generally approved and liked the intervention |

| 25 | Liautaud et al. [71] | HIV/TB IPC |

1. FIANANCE: (University of Free State received funding for this program from Canada’s Global Health Research Initiative) 2. EDUCATE: (HCWs were trained on HIV/TB IPC; training was made dynamic—via the use of collaborative projects that had to address a specific HIV/TB IPC challenge at the HCWs place of work; HCWs had to develop proposals, initiate research models, and collect data) |

1. FEASIBILITY: Barriers to intervention implementation were identified: not enough time, lack of resources, logistical challenges, and institutional capacity; Lack of computer skills to develop HIV/TB IPC materials for research/data collection was a barrier to many HCWs | 1. ACCEPTIBILITY: HCWs stated that this intervention program was good, eye-opening, and substantial; HCWs felt they had learned a lot about research that they previously had no exposure to |

| 26 | Liu et al. [72] | Ebola ETU safe design/layout for patient isolation and infection reduction; standard precautions; transmission-based precautions |

1. RESTRUCTURE: (facilities to care for EVD patients was completely physically re-designed to adhere to IPC guidelines; cameras install into EVD units for close patient monitoring; Initiating a buddy-system for EVD patient care) 2. EDUCATE: (new EVD guidelines were developed; new tools for donning/doffing were produced—41 step PPE wearing guide was developed; training for EVD IPC provided to all HCWs working with EVD patients) 3. QUALITY MGMT: (strict supervision and inspection of all staff’s PPE prior to ETU entry was required; site inspections occurred regularly with video surveillance; Feedback was immediately provided to HCWs if PPE errors were observed) |

None |

1. PENETRATION: 1520 individuals were trained in EVD IPC; 80 local HCWs were trained in EVD IPC 2. FEASIBILITY: EVD facilities were constructed |

| 27 | Mahomed et al. [73] | IPC Practices (including standard precautions and transmission-based precautions) |

1. RESTRUCTURE: (trained nurses were used to fill out ICATs for given IPC assessment areas, like hand hygiene or isolation/quarantine) 2. EDUCATE: (nurses were trained on the ICAT tool) 3. QUALITY MGMT: (introduction of the ICAT tool to assess how well IPC is being implemented in ICUS) |

None |

1. PENETRATION: IPC practices associated with study were carried out in 6 public and 5 private ICUs 2. FEASIBILITY: Nurses successfully completed ICAT assessments |

| 28 | Miceli et al. [74] | HIV prevention/ART, TB screening/therapy, malaria screening/therapy |

1. EDUCATE: (implemented the Integrated Management of Infectious Disease training program; made training dynamic via case studies, group discussions, and small group work; On-site support and continuing education for HCWs was provided throughout 9-month study period) 2. QUALITY MGMT: (performed observations of HCWs practice for a total of 20 observations; assessed site performance via a surveillance system; assessment of population outcomes) |

None | 1. PENETRATION: 72 HCWs trained on IMID; HCWs applied complex clinical reasoning concepts by: analyzing 40–50 cases, discussing 20–30 presentations from their peers, 36 h of clinical placement, and discussing with 20 physicians |

| 29 | Mbombo & Bimerew [75] | PMTCT (HIV therapy) | 1. EDUCATE: (trainings performed in both midwifery and PMTCT for nursing students: training was dynamic via skills lab, visualization processes, guided practice, and independent practice) | 1. PENETRATION: Of 154 students, 107 (69.5%) provided intrapartum ARV prophylaxis to pregnant women; Of 116 students, 75.3% conducted neonatal ARV prophylaxis, (23 or 14.5%) performed 15 neonatal ARV prophylaxis procedures | 1. PENETRATION: 134 students performed the HIV pre-testing counseling competency (only 119 or 77.3%) completed the required 10 pre-test cases; 132 students completed the post-test counseling competency (only 115 or 74.7%) completed the required 10 post-test cases; Of the 144 student who submitted their competencies, 135 (87.7%) performed the required 7 rapid fingersticks for HIV testing; 121 (78%) of students provided dual ARV therapy (74 or 48.1%) competed the required 10 dual therapy sessions; |

| 30 | Ogoina et al. [76] | Standard precautions and transmission-based precautions for EVD prevention |

1. PLAN: (established partnerships between the Niger Delta University Teaching Hospital (NDUTH) and the Bayelsa State Ebola Task Force, the MOH, and international partners, like WHO; appraisal of the hospital’s EVD preparedness was assessed via the WHO Ebola checklist) 2. RESTRUTURE: (EVD response team was created at hospital; Facility altered to include isolation/quarantine space) 3. EDUCATE: (sensitization EVD workshops were provided to all HCWs) 4. FINANCIAL (funds from the state allowed for an isolation ward to be designed and built) 5. QUALITY MGMT: (assessments performed to assess HCW EVD knowledge, fears, myths; continuous IPC evaluations were performed throughout epidemic |

1. PENETRATION: 3 EVD “alarms” were reported, which turned out to be false/non-EVD cases 2. SUSTAINABILITY: a significant outcome of this study is associated with sustainability. Once the EVD outbreak was over in Nigeria, the IPC activities were not sustained |