Abstract

Neuroimaging studies have uncovered structural and functional alterations in the cingulate cortex in individuals with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Such abnormalities may underlie neurochemical imbalance. In order to characterize the neurochemical profile, the current study examined the concentration of brain metabolites in dorsal ACC (dACC) and posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) in high-functioning adults with ASD. Twenty high-functioning adults with ASD and 20 age- and-IQ-matched typically developing (TD) peers participated in this Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) study. LCModel was used in analyzing the spectra to measure the levels of N-Acetyl aspartate (NAA), choline (Cho), creatine (Cr), and glutamate/glutamine (Glx) in dACC and PCC. Groups were compared using means for the ratio of each metabolite to their respective Cr levels as well as on absolute internal-water-referenced measures of each metabolite. There was a significant increase in Cho in PCC for ASD adults, with a marginal increase in dACC. A reduction in NAA/Cr in dACC was found in ASD participants, compared to their TD peers. No significant differences in Glx/Cr or Cho/Cr were found in dACC. There were no statistically significant group differences in the absolute concentration of NAA, Cr, Glx, or NAA/Cr, Cho/Cr, and Glx/Cr in the PCC. Differences in the metabolic properties of dACC compared to PCC were also found. Results of this study provide evidence for possible cellular and metabolic differences in the dACC and PCC in adults with ASD. This may suggest neuronal dysfunction in these regions and may contribute to the neuropathology of ASD.

Keywords: autism spectrum disorder, cingulate cortex, 1H-MRS, MR spectroscopy, neurochemicals, biochemistry

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder with varying levels of neuropathology spanning aberrant structure, function, and potentially altered neuronal metabolism. Differences in neurochemical levels, intracellular mechanisms, and cell metabolism can affect the integrity of neurons and ultimately impact the overall brain function [Isacson, 1993]. Such abnormalities in neurochemical levels would impact local function within the affected area, but could also disrupt the connectivity with other brain regions, ultimately causing the disruption of important cognitive and social functions. These functions (e.g., social interaction, communication, decision-making) are found to be markedly impaired in individuals with ASD.

An intriguing aspect of the neuropathology of autism is its complexity and breadth that spans across different levels. Previous neuroimaging studies point to diffuse functional and anatomical abnormalities in the brains of individuals with ASD [Anagnostou & Taylor, 2011; Minshew & Williams, 2007]. Although structural and functional neuroimaging studies provide valuable information on neuroanatomy and function, they are not tuned to elicit information at the neurochemical level. Proton Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) is the only noninvasive MRI technique available for measuring tissue metabolite concentration in the living brain [Stanley, 2002], and is often used for identifying disease-related abnormalities [Fayed, Olmos, Morales, & Modrego, 2006] in disorders like ASD. It has proven to be an effective tool for the assessment of various pathologic conditions, including epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, stroke, cancer, and metabolic diseases [Ross & Bluml, 2001]. 1H-MRS can be especially helpful in uncovering the concentration of a number of neurochemicals and their role in healthy and unhealthy brains. It provides stable measures of metabolite concentrations in healthy individuals [Geurts et al., 2004], so it can be used as a valuable technique for assessing potential neurobiological alterations in autism. Given the functional and structural alterations previously identified in ASD, studies using 1H-MRS can potentially add deeper levels of biological insights into ASD that cannot be accomplished by traditional MRI.

MR spectroscopy allows for measurement of a number of metabolites, including N-acetylaspartate (NAA), Choline (Cho), Glutamate/Glutamine (Glx), and Creatine (Cr). NAA is a neuronal marker, representing neuronal and axonal health and density, and reductions in NAA concentrations can be a marker for disease [Fayed et al., 2006; Maddock & Buonocore, 2012; Meyerhoff et al., 1993]. Cho levels represent cellular membrane proliferation and degradation [Fayed et al., 2006; Maddock & Buonocore, 2012]. Glutamate is related to oxidative energy production and excitatory neurotransmitter functions, while glutamine is involved with glutamate recycling and regulation of brain ammonia metabolism [Maddock & Buonocore, 2012; Waagepetersen, Sonnewald, & Schousboe, 2007]. The combined Glx thus represents overall glutamate/glutamine levels and their functioning in the brain [Maddock & Buonocore, 2012; Rothman, Behar, Hyder, & Shulman, 2003; Yuksel & Ongur, 2010]. Finally, Cr plays a role in central nervous system energy homeostasis, and represents the most stable cerebral metabolite [Fayed et al., 2006; Maddock & Buonocore, 2012]. Because Cr is so stable, it is often used as an internal reference value, and other metabolites are reported in terms of their ratio to Cr (e.g., NAA/Cr for the measurement of NAA).

Previous studies have uncovered alterations in various neurochemicals in ASD, with reduced NAA level in both gray and white matter serving as the most common finding [Ipser et al., 2012]. The methodology used in previous studies has varied greatly in terms of scanner strength (many using 1.5 T, rather than 3 T) and how metabolites are referenced (Cr ratio, internal water reference, or no reference). Using a 3T scanner, the current study applied 1H-MRS to study the dorsal anterior cingulate (dACC) and posterior cingulate (PCC) cortices in adults with ASD. The metabolites are reported in a ratio to Cr and as absolute measures of internal-water-referenced metabolites, to gain a better understanding of how these measures may differ in ASD.

Previous fMRI studies in ASD have found significantly reduced ACC response for motor preparation [Rinehart, Bradshaw, Brereton, & Tonge, 2001], processing familiar faces [Pierce & Redcay, 2008], and for response inhibition [Kana, Keller, Minshew, & Just, 2007]; and significantly reduced PCC activation for spatial working memory [Luna et al., 2002], and for processing faces of familiar children [Pierce & Redcay, 2008], when compared to control individuals. Abnormalities in cingulate cortex volume [Abell et al., 1999; Haznedar et al., 1997; Schumann et al., 2010] and alterations in its underlying white matter [Barnea-Goraly et al., 2004; Jou et al., 2011; Kumar et al., 2010; Noriuchi et al., 2010; Pardini et al., 2009; Thakkar et al., 2008] have also been reported in ASD. Functional connectivity MRI studies in ASD have also uncovered significant alterations in connectivity involving ACC and PCC during cognitive tasks [Agam, Joseph, Barton, & Manoach, 2010; Kleinhans et al., 2008; Shih et al., 2011; Solomon et al., 2009] and during resting state [Assaf et al., 2010; Cherkassky, Kana, Keller, & Just, 2006; Monk et al., 2009; Weng et al., 2010]. Thus, the cingulate cortex was chosen as the area of interest (focusing on dACC and PCC) due to its widespread alterations in function, anatomy, and connectivity reported in autism. The current study aims to determine whether alterations in metabolite concentrations also exist across cingulate cortex. Although a few previous studies have examined the ACC using 1H-MRS, the results have been relatively inconsistent. Two studies found reduced choline (Cho) level in left ACC [Levitt et al., 2003] and reduced NAA/Cr in the ACC [Fujii et al., 2010] in ASD children compared to typically developing (TD) children. Another study found reduced Cr and increased glutamate/glutamine (Glx) in pregenual ACC in children with ASD [Bejjani et al., 2012]; yet another found increased glutamate (Glu) in ACC in children with ASD [Joshi et al., 2013]. Three additional studies examined adults with ASD, finding increased NAA/Cho in the ACC [Oner et al., 2007], reduced NAA, and combined Glutamate/Glutamine (Glx) in pregenual ACC [van Elst et al., 2014], and reduced Glx in right ACC [Bernardi et al., 2011] compared to TD peers. PCC is another region of multiple abnormalities in ASD. For instance, reduced connectivity between the PCC and medial prefrontal cortex has been reported in a mixed group of children and adolescents with ASD [Rudie et al., 2012]. Lynch et al. [2013] examined the default mode network and found hyperconnectivity of PCC in children with autism and its correlation with social symptoms. Moreover, abnormal cytoarchitecture has also been reported in PCC in autism with irregularly distributed neurons in specific cortical layers along with the presence of increased white matter neurons [Oblak, Rosene, Kemper, Bauman, & Blatt, 2011]. Nevertheless, to date, the PCC has not been studied in ASD using 1H-MRS. The current study is thus novel in that it investigates metabolite levels in PCC in ASD, and also compares the metabolite levels between the dACC and PCC. Based on function, anatomy, and connectivity differences involving the cingulate cortex, as well as a few previous 1H-MRS studies uncovering significantly reduced NAA in ACC (see Ipser et al. [2012] for a review), we expect to find alterations in metabolites in these regions, particularly within the ACC. In addition, to better understand the link between neurochemical markers in ASD and behavior, we will also correlate brain metabolites with cognitive measures. The findings of this study may provide valuable insights into the health of neurons in ASD and its impact on the behavioral phenotype of autism.

Method and Materials

Participants

Twenty high-functioning adults with ASD (15 males/5 females; mean age: 26.8 years) and 20 age and IQ matched TD peers (15 males/5 females; mean age: 24.9 years) participated in this study (see Table 1 for demographic information). Full-scale IQ (FSIQ), verbal IQ (VIQ), and performance IQ (PIQ) were assessed using the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) [Wechsler, 1999], handedness using the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory [Oldfield, 1971], and ASD symptoms using the Ritvo Autism Asperger Diagnostic Scale-Revised (RAADS-R) [Ritvo et al., 2011]. Age, FSIQ, VIQ, and PIQ were not significantly different between groups. The groups also did not significantly differ on socioeconomic status as measured by income and highest level of education achieved. The ASD group scored significantly higher on the RAADS-R compared to their TD peers (see Table 1). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our university, and all participants provided informed consent for their participation in the study. Participants with ASD had received a previous diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder or Asperger’s syndrome based on autism diagnostic interview-revised (ADI-R) [Rutter, Le Couteur, & Lord, 2003] symptoms and autism diagnostic observation schedule (ADOS) [Lord et al., 2000] confirmed by obtaining clinical records and diagnostic reports from each subject’s licensed clinical psychologist. In addition, the RAADS-R was administered as a supplementary measure to confirm diagnosis. Scores on the RAADS-R have been found to have 95.59% concurrent validity with the Social Responsiveness Scale-Adult [Ritvo et al., 2011] and 96% concurrent validity with the ADOS Module 4 [Ritvo, 2013]. All subjects included in the ASD group met the cutoff for ASD based on the RAADS-R scoring criteria. TD participants were screened through a self-report history questionnaire to rule out neuropsychiatric disorders, such as ASD, ADHD, or Tourette’s Disorder, that could potentially confound the results. Several ASD participants reported taking medications, including stimulant medication (n = 6), antidepressants (n = 9), anxiety medication (n = 1), and antipsychotic medication (n = 1). Eight ASD participants reported no medications, and no TD participants reported taking medication. Finally, all participants in this study were reported to be nonsmokers.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics

| Autism | Control | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 20 | N = 20 | Group difference | ||||||

| Mean | Range | s.d. | Mean | Range | s.d. | t-value | P-value | |

| Age | 26.8 | 19–40 | 1.35 | 24.9 | 19–38 | 1.13 | 1.04 | 0.30 |

| Verbal IQ | 113.7 | 95–139 | 3.15 | 113.8 | 88–141 | 2.91 | 0.01 | 0.98 |

| Performance IQ | 113.9 | 94–138 | 3.18 | 115.1 | 99–133 | 2.84 | 0.27 | 0.78 |

| Full-scale IQ | 115.4 | 99–140 | 2.88 | 117.5 | 103–140 | 2.51 | 0.53 | 0.59 |

| RAADS-R total | 128.7 | 72–181 | 6.66 | 39.15 | 13–77 | 3.84 | 11.4 | <0.0001 |

1H-MRS Imaging

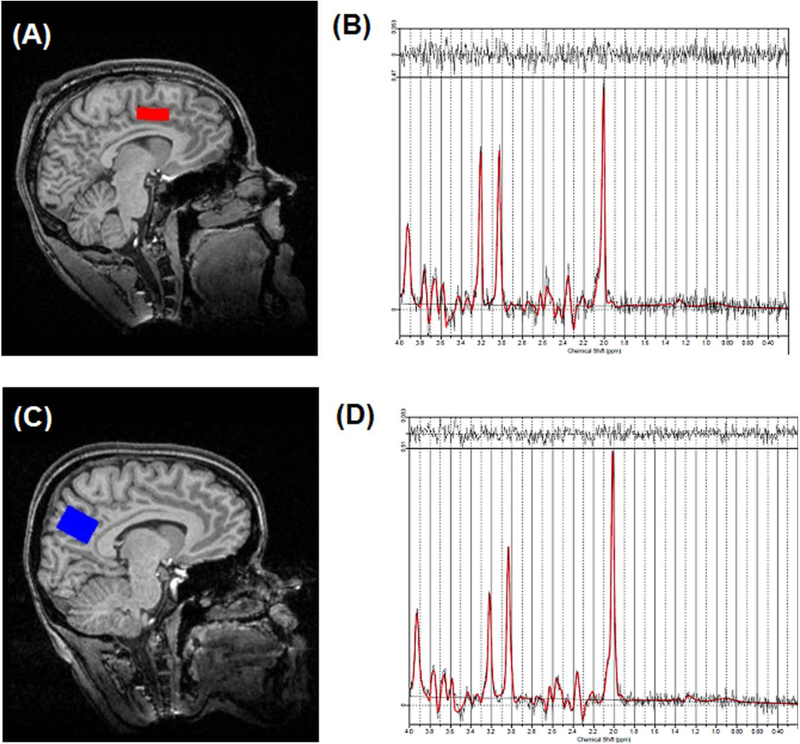

Imaging was performed on a 3T head-only scanner (Siemens Allegra, Erlangen, Germany) with a circularly polarized transmit/receive head coil. A series of sagittal, coronal, and axial T1-weighted anatomical scans were acquired for 1H-MRS voxel placement (gradient-recalled echo sequence; TR = 250ms, TE = 3.48ms, flip angle = 70 degrees, 512 × 512 matrix size, 5 mm slice thickness, and 1.5 mm gap). Slices were aligned to the anatomical midline to control for head tilt. The 1H-MRS voxel for dACC (20 × 27 × 10 mm) was positioned around the center of the ACC, identified centrally in the gray matter above the anterior body of the corpus callosum. The anterior aspect of the dACC voxel was aligned with the topmost anterior corner of the lateral ventricle. The 1H-MRS voxel for PCC (20 × 27 × 20 mm) was positioned above the splenium of the corpus callosum with the long axis parallel to the parietooccipital sulcus (see Fig. 1 for sample voxel placement). These voxels were placed on the basis of the sagittal and coronal images, such that the amount of gray matter in the voxel as viewed on the T1-weighted images is maximized. Following manual shimming to optimize field homogeneity across the voxel, water-suppressed spectra were collected with the point-resolved spectroscopy sequence (PRESS; TR/TE = 2000/80 ms, 1200 Hz spectral bandwidth, 1024 points, 128 averages, and 4 min 24 s scanning time). Water unsuppressed spectra (eight averages) were also acquired for quantitation.

Figure 1.

Example 1H-MRS voxel position for (A) dACC and (C) PCC from one participant; Sample spectrum (black) and LCModel fit (red) from the (B) dACC and (D) PCC.

MRS data were processed in LCModel (version 6.3–0L) [Provencher, 1993]. The basis set was provided with LCModel and consisted of the following: alanine, aspartate, creatine (Cr), phosphocreatine (PCr), gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), glucose, glutamine (Gln), glutamate (Glu), glycerophosphocholine (GPC), phosphocholine (PCh), glutathione, myo-Inositol, lactate, N-acetylaspartate (NAA), N-acetylaspartylglutamate (NAAG), scyllo-Inositol, taurine, lipids, and macromolecules. Spectra were eddy-current corrected and water-scaled using the unsuppressed water, yielding quantification of total NAA (NAA + NAAG), Glx (Glu + Gln), total Cho (GPC + PCh), and total Cr (Cr + PCr). Water-scaled metabolites were corrected for the proportion of CSF within the MRS voxel using the equation Metcorr = Met/(1-CSF), where Metcorr is the corrected metabolite value, Met is the LCModel value, and CSF is the fraction of CSF within the voxel [de la Fuente-Sandoval et al., 2011]. Metabolite levels are reported in institutional units and as ratios to total creatine (Cr + PCr). Cramer-Rao lower bounds (CRLB) were calculated by LCModel and used as a measure of uncertainty of the fitting procedure for the metabolite concentrations [Jiru, Skoch, Klose, Grodd, & Hajek, 2006; Provencher, 2001]. Inclusion in analyses required metabolites to have CRLB less than 20%, to ensure lower quality spectra are rejected and only the highest quality (most accurately measured) parameters are included. Three participants (2 ASD, 1 TD) were removed from dACC Glx analyses due to CRLB >20%. One TD participant was removed from all PCC analyses due to poor model fit caused by head motion. Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS (version 11.5). Demographics were compared using independent samples t-tests. Metabolite ratios (to Cr) and water-referenced metabolite measures were compared between groups using ANCOVA, covarying for age. Regional differences in metabolite concentrations (between dACC and PCC) were compared using one-way ANOVAs. In exploratory analyses, Pearson’s correlation coefficients were used to evaluate the relationship between metabolite levels and cognitive and symptom severity measures (FSIQ, VIQ, PIQ, RAADS-R).

Voxel-Based Morphometry

Anatomical images were acquired using high-resolution T1-weighted scans using a 160 slice 3D magnetization-prepared rapid acquisition gradient-echo (MPRAGE) volume scan with a TR = 200ms, TE = 3.34 ms, flip angle = 12°, FOV = 25.6 cm, 256 × 256 matrix size, and 1mm slice thickness. Images were independently visually inspected by three researchers to confirm data quality (and images with significant distortion due to head motion or scanner artifact were excluded). All three researchers mutually agreed on the quality of images, and were deemed acceptable for segmentation. Based on this quality control, no volumes needed to be excluded. Anatomical data were processed using Statistical Parametric Mapping 8 (SPM8; Wellcome Trust Center for Neuroimaging) in MATLAB version 7.11.0 (Mathworks). As metabolite concentrations vary depending on the brain tissue type being examined, the tissue concentrations within our regions of interest (ROI) were measured for each subject to ensure the tissue content of the ROIs did not differ between groups. Each participant’s T1-weighted MPRAGE image was segmented into gray matter (GM), white matter (WM), and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) using the segmentation routine in SPM8. Using subjects’ native-space masks, we calculated the total GM, WM, and CSF volumes within a mask that represented the exact placement of the dACC and PCC voxels from the 1H-MRS data collection. This was done using a script adapted from John’s SPM Gems (http://www-personal.umich.edu/ñichols/JohnsGems.html) in MATLAB. No significant differences were found between groups in tissue content for the dACC GM ([F(1,37)=0.11, P = 0.73), WM ([F(1,37)=0.19, P = 0.65), and CSF ([F(1,37)=0.60, P = 0.44) or PCC GM ([F(1,37)=0.21, P = 0.64), WM ([F(1,37)=0.05, P = 0.81), and CSF ([F(1,37)=0.005, P = 0.94). The LCModel output was corrected for the proportion of CSF as we report water-scaled results. Results from the 1H-MRS analyses do not change if GM, WM, or CSF tissue concentrations (or any combination of these measures) are included as covariates in the group analyses.

Results

Group Differences in Metabolite Levels in Reference to Creatine

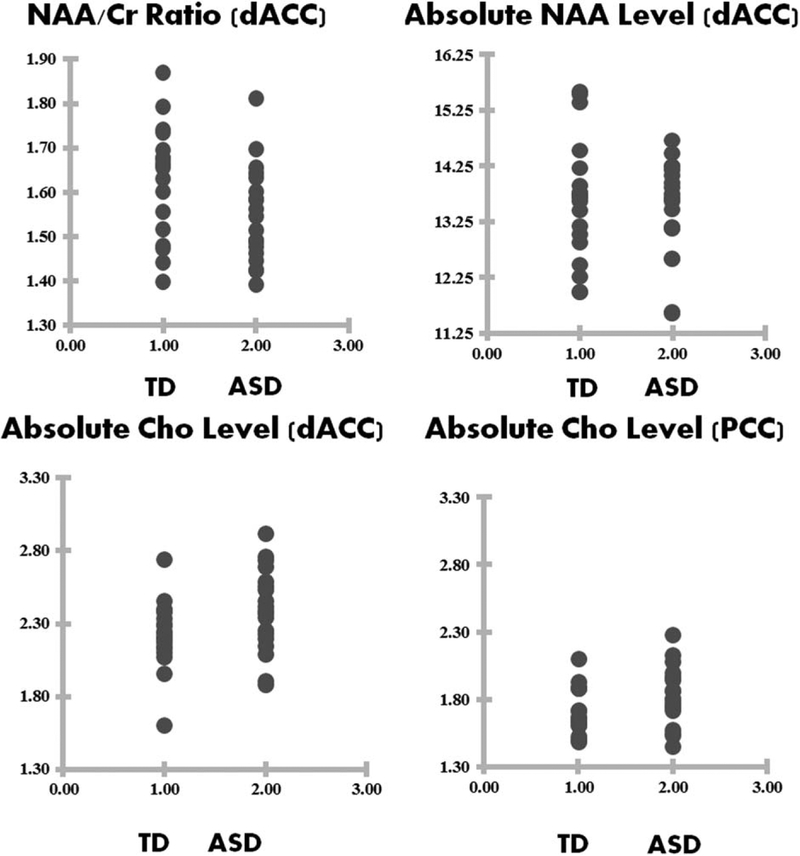

For the dACC, the mean NAA/Cr ratio for the ASD group was significantly reduced compared to the TD group [F(1,37)=4.63, P = 0.038], while there were no statistically significant group differences in Glx/Cr and Cho/Cr ratios (see Fig. 2 and Table 2). For PCC, no significant group differences in the metabolite ratios to Cr were found. It should be noted that the group difference results did not survive Bonferroni correction.

Figure 2.

Raw data points for NAA/Cr ratio for dACC (top left), absolute NAA level for dACC (top right), absolute Cho level (bottom left), and absolute Cho level for PCC (bottom right).

Table 2.

1H-MRS ANCOVA Results Between ASD and TD Groups for Metabolite Levels in Ratio to Cr for dACC and PCC Regions

| ROI | Metabolite | ASD (n = 20) Mean (SD) | TD (n = 20) Mean (SD) | Group differences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F-statistic | P-value | ||||

| dACC | NAA/Cr | 1.54 (0.10) | 1.62 (0.12) | F(1,37)=4.63 | 0.038 |

| Glx/Cr | 1.11 (0.12) | 1.16 (0.11) | F(1,34)=1.60 | 0.214 | |

| Cho/Cr | 0.27 (0.03) | 0.26 (0.02) | F(1,37)=0.41 | 0.523 | |

| Linewidth (ppm) | 0.03 (0.009) | 0.03 (0.005) | F(1,37)=0.05 | 0.824 | |

| PCC | NAA/Cr | 1.64 (0.09) | 1.68 (0.10) | F(1,36)=1.64 | 0.207 |

| Glx/Cr | 1.01 (0.11) | 1.03 (0.11) | F(1,36)=0.19 | 0.664 | |

| Cho/Cr | 0.19 (0.02) | 0.18 (0.01) | F(1,36)=2.66 | 0.111 | |

| Linewidth (ppm) | 0.03 (0.005) | 0.03 (0.012) | F(1,37)=0.29 | 0.592 | |

Group Differences in Absolute Metabolite Levels

In comparing group differences in absolute metabolite concentrations (using internal water referencing), the mean level of Cho for the ASD group was significantly increased, compared to the TD group, in PCC [F(1,36)=4.99, P = 0.032], with a marginal increase in Cho for the dACC region [F(1,37)=3.74, P = 0.061] (see Fig. 2 and Table 3). No significant differences in NAA, Glx, or Cr were found between groups for either PCC or dACC. It should be noted that none of the group differences survive Bonferroni correction.

Table 3.

1H-MRS ANCOVA Results Between ASD and TD Groups for Absolute Metabolite Levels for dACC and PCC Regions

| ROI | Metabolite | ASD (n = 20) Mean (SD) | TD (n = 20) Mean (SD) | Group differences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F-statistic | P-value | ||||

| dACC | NAA | 13.49 (0.85) | 13.63 (1.06) | F(1,37) = 0.09 | 0.764 |

| CRLB,% | 2.65 (0.93) | 2.90 (1.07) | |||

| Glx | 9.82 (1.11) | 9.83 (1.30) | F(1,34) = 0.00 | 0.980 | |

| CRLB,% | 11.88 (1.93) | 13.47 (4.04) | |||

| Cho | 2.38 (0.27) | 2.22 (0.22) | F(1,37) = 3.74 | 0.061 | |

| CRLB,% | 3.90 (1.16) | 4.55 (1.27) | |||

| Cr | 8.75 (0.61) | 8.41 (0.94) | F(1,37) = 1.70 | 0.200 | |

| CRLB,% | 3.35 (1.03) | 3.55 (0.82) | |||

| Linewidth (ppm) | 0.03 (0.009) | 0.03 (0.005) | F(1,37) = 0.05 | 0.824 | |

| PCC | NAA | 15.34 (1.04) | 15.36 (0.94) | F(1,36) = 0.00 | 0.968 |

| CRLB,% | 1.85 (0.48) | 1.94 (0.40) | |||

| Glx | 9.46 (0.99) | 9.48 (1.02) | F(1,36) = 0.04 | 0.832 | |

| CRLB,% | 10.05 (2.98) | 10.36 (2.47) | |||

| Cho | 1.82 (0.21) | 1.69 (0.16) | F(1,36) = 4.99 | 0.032 | |

| CRLB,% | 3.50 (0.82) | 4.00 (1.41) | |||

| Cr | 9.37 (0.69) | 9.15 (0.81) | F(1,36) = 0.71 | 0.402 | |

| CRLB,% | 2.25 (0.55) | 2.42 (0.76) | |||

| Linewidth (ppm) | 0.03 (0.005) | 0.03 (0.012) | F(1,37) = 0.29 | 0.592 | |

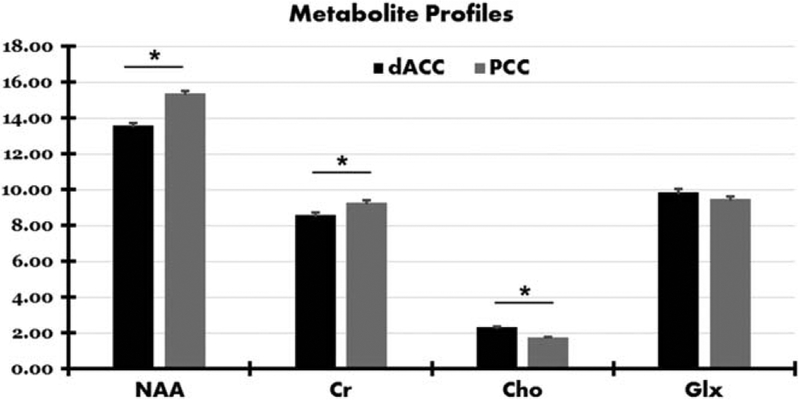

Regional Differences in Metabolite Concentration

To examine potential differences in metabolic concentrations between dACC and PCC, mean metabolite concentrations were compared between the two regions. A similar pattern of results emerged for all participants combined (TD + ASD), for ASD participants only, and for TD participants only (see Fig. 3 and Table 4). Compared to PCC, dACC had significantly lower NAA [F(1,77)=67.1, P < 0.001] and Cr [F(1,77)=15.2, P < 0.001], and significantly higher Cho [F(1,77)=107.2, P < 0.001]. No significant differences in Glx emerged between the two regions [F(1,74)=2.00, P = 0.161].

Figure 3.

Mean levels for each metabolite for dorsal anterior cingulate (dACC) and posterior cingulate (PCC) cortices. Significant differences in absolute metabolite concentrations between the two regions are indicated with an asterisk (*).

Table 4.

Regional Differences in Metabolite Levels

| Subjects | Metabolite | Regions | Regional differences | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dACC Mean (SD) | PCC Mean (SD) | F statistic | P-value | ||

| All | NAA | 13.56 (0.95) | 15.35 (0.98) | F(1,77) = 67.1 | <0.001 |

| Cr | 8.58 (0.80) | 9.26 (0.75) | F(1,77) = 15.2 | <0.001 | |

| Cho | 2.30 (0.26) | 1.76 (0.19) | F(1,77) = 107.3 | <0.001 | |

| Glx | 9.82 (1.19) | 9.47 (0.99) | F(1,74) = 2.00 | 0.161 | |

| TD | NAA | 13.63 (1.06) | 15.36 (0.94) | F(1,37) = 28.58 | <0.001 |

| Cr | 8.41 (0.94) | 9.15 (0.81) | F(1,37) = 6.86 | 0.013 | |

| Cho | 2.22 (0.22) | 1.69 (0.16) | F(1,37) = 69.1 | <0.001 | |

| Glx | 9.83 (1.30) | 9.48 (1.02) | F(1,36) = 0.87 | 0.357 | |

| ASD | NAA | 13.49 (0.85) | 15.34 (1.04) | F(1,38) = 37.53 | <0.001 |

| Cr | 8.75 (0.61) | 9.37 (0.69) | F(1,38) = 8.93 | 0.005 | |

| Cho | 2.38 (0.27) | 1.82 (0.21) | F(1,38) = 52.46 | <0.001 | |

| Glx | 9.82 (1.11) | 9.46 (0.99) | F(1,36) = 1.09 | 0.302 | |

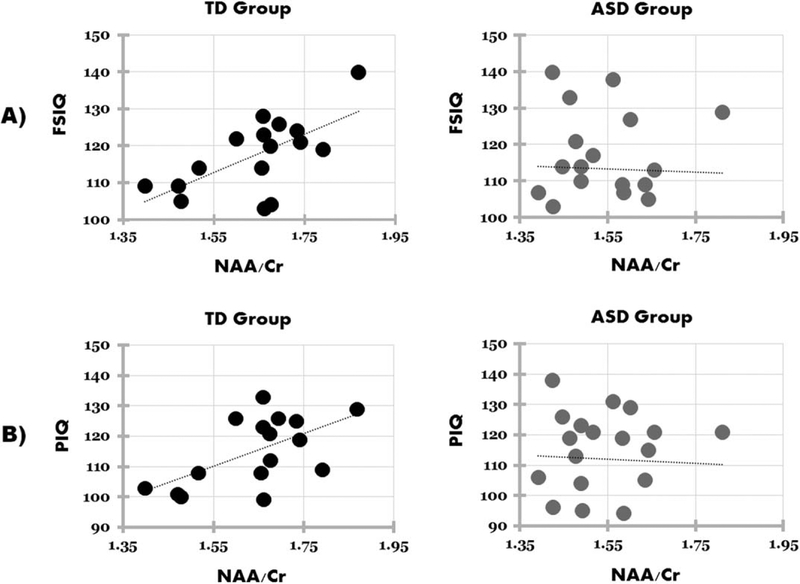

Correlations Between Metabolite Concentrations and Cognitive Measures

NAA/Cr for the dACC was significantly positively correlated with FSIQ in TD (r(18)= 0.645, P = 0.007) but not in ASD participants (r(18)= −0.031, P = 0.898) (see Fig. 4). There was a significant difference between groups on their correlation coefficients (Z= 2.32, P = 0.020). NAA/Cr for the dACC was also significantly positively correlated with PIQ in TD (r(18)= 0.589, P = 0.016) but not in ASD participants (r(18) = −0.047, P = 0.844), again with a significant difference between groups (Z= 2.10, P = 0.034). No significant correlations were found for either group for dACC NAA/Cr and VIQ or RAADS-R. Nor was there any significant correlation for either group between any of the absolute measures of metabolites (NAA, Cho, Cr, Glx) or other Cr ratio measures (Cho/Cr, Glx/Cr) and any of the cognitive measures collected (FSIQ, VIQ, PIQ, RAADS-R) for dACC. In addition, no significant correlations were found for either group for any of the metabolite or metabolite ratios in PCC and cognitive measures.

Figure 4.

Pearson’s correlations for (A) full-scale IQ (FSIQ) and NAA/Cr for the typically developing (TD) group (left; r = 0.645, P = 0.007) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) group (right; r = −0.031, P = 0.898), and (B) performance IQ (PIQ) and NAA/Cr for TD (left; r = 0.589, P = 0.016) and ASD (right; r = −0.047, P = 0.844) groups.

Impact of Medication Use

An exploratory analysis was conducted to determine whether use of medication impacted metabolic measures. No significant differences were found between the medicated (n = 12) and unmedicated (n = 8) ASD participants for any of the absolute metabolite levels. In comparing unmedicated ASD participants (n = 8) to TD participants (n = 20), marginal increases in Cho were found for the unmedicated ASD participants in both dACC [F(1,25)=3.11, P = 0.089] and PCC [F(1,25)=3.18, P = 0.086]. No other significant differences were found in absolute metabolite levels between unmedicated ASD participants and TD participants. However, due to the small number of subjects in each of these subgroups, such comparison is relatively under-powered. Nevertheless, these findings are fairly consistent with the overall between-group results of the study.

Discussion

The main findings of this MR spectroscopy study include a significant reduction in NAA/Cr in the dACC for ASD participants, compared to their TD peers. However, the absolute NAA level was not found to be significantly different across groups when using internal water referencing. A significant increase in water scaled Cho was found in the PCC in ASD group, relative to the TD group, with a similar marginal difference in dACC. It should be noted that the results do not survive multiple comparisons correction using Bonferroni correction.

Group Differences in NAA level

Reduced levels of NAA/Cr in dACC in our study are consistent with previous reports of reduced NAA concentration in adults with ASD in the ACC [Fujii et al., 2010]; however, they are not consistent with previous studies reporting increased NAA/Cr [Oner et al., 2007], reduced Glx [Bernardi et al., 2011], increased Glx [Joshi et al., 2013], increased Cho [Vasconcelos et al., 2008], and reduced Cho in inferior ACC but no significant differences in superior ACC [Levitt et al., 2003]. Some of the differences in results may stem from widely varying methodology across studies. For example, only two of the previous studies used tissue segmentation procedure to control for tissue content [Joshi et al., 2013; Levitt et al., 2003] and just two studies used MRI scanners with field strength above 1.5T [Bernardi et al., 2011; Joshi et al., 2013]. Previous studies examining the ACC in ASD have also differed in whether they reported absolute quantification of metabolites [Bernardi et al., 2011; Joshi et al., 2013; Levitt et al., 2003], or ratios [Oner et al., 2007], or both [Fujii et al., 2010; Vasconcelos et al., 2008]; and none report using water as a reference for quantification. In addition, subjects vary in age from 2–50 years, and the number of included ASD subjects ranges from 7–31 years. All of these factors combined make it incredibly challenging to interpret the real state of metabolite concentrations within the ACC in ASD.

A reduction in NAA level may suggest the possibility of continuing neuronal compromise in ACC [Ipser et al., 2012]. This is particularly important considering the cingulate cortex abnormalities in ASD reported widely in studies using functional MRI [Assaf et al., 2010; Chiu et al., 2008; Lombardo et al., 2010], MRI-based morphometry [Abell et al., 1999; Haznedar et al., 2000], diffusion tensor imaging [Barnea-Goraly et al., 2004; Jou et al., 2011; Kumar et al., 2010; Noriuchi et al., 2010; Pardini et al., 2009; Thakkar et al., 2008), PET (Haznedar et al., 1997, 2000], single-photon emission computed tomography [Ohnishi et al., 2000], and postmortem studies [Bauman & Kemper, 1994]. NAA is a neurochemical that is synthesized in the mitochondria of neurons, and it is present in most neuronal cell types, although it is highly concentrated in gray matter [Moffett, Ross, Arun, Madhavarao, & Namboodiri, 2007]. The primary roles for NAA in the brain have been suggested to include facilitating energy metabolism in neuronal mitochondria, serving as a source of acetate for myelin synthesis in oligodendrocytes, and as a precursor for the biosynthesis of N-acetyl aspartyl glutamate (which modulates neurotransmitter release from the synapse [Xi, Baker, Shen, Carson, & Kalivas, 2002; Zhao et al., 2001]) [Madhavarao & Namboodiri, 2006; Moffett et al., 2007]. Within the 1H-MRS spectra, NAA serves as the largest peak, and it has been shown to be fairly stable in healthy adults longitudinally [Rigotti et al., 2011]. Thus, reductions in NAA are typically indicative of disease or neuronal damage, as seen in cases of brain cancer, multiple sclerosis, brain injury, and Alzheimer’s Disease [Danielsen & Ross, 1999]. NAA level decreases when there is tissue destruction and reversibly so when the neuronal tissue is suffering [De Stefano et al., 1998] thereby nonspecifically reflecting the general state of the health of neurons. Reduction in NAA/Cr in dACC found in the current study could potentially be underscored by neuronal or axonal damage in that region in ASD. One previous study using postmortem and fresh-frozen tissue samples from ACC in individuals with ASD uncovered significantly greater astroglial reactions (and astrogliosis in some cases) and increases in proinflammatory and modulatory cytokines, compared to control tissue samples [Vargas, Nascimbene, Krishnan, Zimmerman, & Pardo, 2005]. Higher astroglial reactions and greater inflammatory processes, representing tissue damage and potential inhibition of neuronal repair, in cingulate cortex in ASD could support reductions in NAA measured using 1H-MRS. Reductions in NAA/Cr may also be indicative of a mitochondrial dysfunction, given the role of NAA in mitochondrial energy metabolism within neurons. Mitochondrial disease as well as biomarkers for mitochondrial dysfunction are prevalent at much higher rates in ASD children compared to the general population (see [Rossignol & Frye, 2012] for a review). In addition, altered expression of genes encoding the mitochondrial aspartate/glutamate carrier (AGC1) has been associated with ASD, marking a potential link between neuronal dysfunction and NAA levels in ASD [Palmieri et al., 2010; Ramoz et al., 2004; Segurado et al., 2005]. Our finding of reduced NAA/Cr in ASD adults may support the possibility of abnormal mitochondrial function in the brains of affected individuals. NAA has also been found to predict the severity of illness in various neurodegenerative disorders [Brooks et al., 1997; W. M. Brooks et al., 2000; S. D. Friedman, Brooks, Jung, Hart, & Yeo, 1998] and to correlate with cognitive function in brain disorders (A. J. Ross & Sachdev, 2004; A. J. Ross, Sachdev, Wen, Valenzuela, & Brodaty, 2005]. Furthermore, knowledge of NAA levels in autism can not only provide conceptual breakthroughs in basic neurobiology of autism, but also provide important insights into potential treatment options as evident from pharmacological intervention in other disorders [Jang et al., 2006; Khan et al., 2005; Mathew et al., 2008; Mostert, Sijens, Oudkerk, & De Keyser, 2006; Stankoff et al., 2001].

Group Differences in Choline Level

Cho and choline-containing compounds are found most abundantly in the neuronal cell membranes, particularly those of neuroglia, as well as myelin sheaths [Miller et al., 1996]. Significantly increased levels of Cho in PCC and marginally increased levels in dACC in ASD in the current study potentially indicate abnormal cell metabolism or alterations in cell membrane turn-over and/or integrity of this region in ASD. In these lines, previous postmortem studies in ASD have found altered expression of acetylcholine receptors and abnormalities in cholinergic nuclei [Deutsch, Urbano, Neumann, Burket, & Katz, 2010]. Another study found significantly elevated levels of ganglioside GM1 (glycolipids found especially in outer membrane surfaces of nerve cells) in the CSF of children with ASD [Nordin, Lekman, Johansson, Fredman, & Gillberg, 1998]. No previous study, to our knowledge, has examined PCC using 1H-MRS in ASD. The significant difference in Cho level in PCC is important considering previous findings of altered brain activity and connectivity of this region in participants with ASD [Luna et al., 2002; Pierce & Redcay, 2008]. A postmortem study of the PCC in ASD found no significant difference in densities of parvalbumin immunotractive interneurons and calbindin immunoreactive interneurons, although significantly abnormal cytoarchitecture was found in almost all cases [Oblak et al., 2011]. Significant reduction in the number of GABA receptors, and higher binding affinity in the superficial layers of PCC were also found in a postmortem study of ASD [Oblak, Gibbs, & Blatt, 2011]. The PCC is an important node in the default mode network, activating in synchrony with the rest of the network during resting state [Fransson & Marrelec, 2008]. Significant alterations in metabolic function in this region could relate to alterations found in the function [Luna et al., 2002; Pierce & Redcay, 2008] and structure [Abell et al., 1999; Schumann et al., 2010] of PCC.

Concentration of Other Metabolites

This study did not find any significant differences in Glx/Cr or absolute water-scaled Glx between ASD and TD participants. Glutamate is the major excitatory neurotransmitter, and is strongly related to neurodevelopment [Coyle, Leski, & Morrison, 2002], reductions of which could have implications for cellular migration and signaling in ASD [Manent & Represa, 2007]. In fact, a few studies have emphasized the role of glutamate receptor genes in ASD [Jamain et al., 2002; Purcell, Jeon, Zimmerman, Blue, & Pevsner, 2001; Serajee, Zhong, Nabi, & Huq, 2003; Shuang et al., 2004], finding altered glutamate serum levels in adults with ASD [Shinohe et al., 2006], In addition, five previous 1H-MRS studies found reduced Glx in children [DeVito et al., 2007; Kubas et al., 2012] and adults [Bernardi et al., 2011; Horder et al., 2013; van Elst et al., 2014] with ASD, with five other studies finding increased Glx or Glu in adults with ASD [Brown, Singel, Hepburn, & Rojas, 2013; Page et al., 2006] and children [Bejjani et al., 2012; Doyle-Thomas et al., 2014; Joshi et al., 2013]. Despite its implications for brain function in ASD, based on our findings, significant alterations in glutamate may not be the mechanism specific to impaired cingulate cortex function. We also found significant differences in metabolite concentrations between dACC and PCC, with ACC showing a significantly higher level of Cho than PCC and PCC showing higher concentration of NAA and Cr. The anterior and posterior cortices are distinct in both their function and cellular structure [Leech & Sharp, 2014; Vogt, Finch, & Olson, 1992], which along with differing profiles of metabolite concentrations may play an important role in abnormalities seen in ASD.

Relationship Between Metabolites and Cognition

As neurochemical levels can impact neuronal health and function, it is possible that they may predict cognitive abilities, such as intelligence. We found a significant correlation between FSIQ and NAA/Cr for dACC in TD, but not in ASD participants. A few previous studies found a significant positive correlation between FSIQ and NAA in occipitoparietal areas in healthy adults [Jung et al., 1999; Patel & Talcott, 2014]. As NAA is associated with neuronal functioning, it is likely that levels of NAA should indicate better overall brain function. For instance, white matter NAA has been shown to positively correlate with intelligence and with better cognitive performance [Ferguson et al., 2002; Jung et al., 1999; Valenzuela et al., 2000]. However, it should be noted that this significant correlation emerged for the NAA/Cr ratio, but not for the absolute measures of NAA or Cr, indicating that perhaps the balance between these two metabolites is more critical for cognitive functioning. Although the socioeconomic status across our participant groups did not differ significantly, it is possible that some other extraneous factor may drive the IQ correlation found in this study. It is possible that the alterations in NAA/Cr and Cho levels in our study are related to other aspects of ASD, such as social anxiety or information processing (and not the core symptoms of the disorder), measures which were not collected in our study.

Implications of Current Findings

This study examined neurometabolite ratios (using Cr as a reference) as well as their absolute measures of metabolites (using water as a reference) in ASD. While a significant difference in NAA/Cr emerged, this result should be interpreted in the context of the limitations of the ratio method. A previous study found small but opposite changes in levels of NAA and Cr in ALS patients resulting a significant group difference, questioning the validity of the Cr ratio method in understanding the biochemistry of neurological disorders [Weiduschat et al., 2014]. In addition, a handful of studies have reported abnormalities (both increased and decreased) in Cr levels in participants with ASD [Friedman et al., 2003; Hardan et al., 2008; Levitt et al., 2003; Murphy et al., 2002; Page et al., 2006; Suzuki et al., 2010], casting doubts on Cr as an appropriate baseline for metabolite measures. The difference in Cho level (using the water referencing method) suggests the critical role of this relatively underestimated metabolite in the neuropathology of autism.

It is difficult to infer a consistent and common theme from the current 1H-MRS literature in ASD, as the methods used from study to study have varied substantially. For example, previous studies involved different age ranges of participants, differing methodology (sequence, scanner strength, and referencing method), and different ROI sizes and placements, possibly explaining the variability in results. Examining the 30 previous studies measuring regional metabolite concentrations of NAA, Cr, Cho, and/or Glx in both ASD and TD participants, roughly half of the studies included tissue segmentation, 12 mentioned using internal water referencing techniques, only 8 studies used a 3T or 4T scanner (all others used 1.5T, which is 20% less sensitive than 3T for measuring spectra [Barker, Hearshen, & Boska, 2001]), and 24 studies reported absolute measurement of metabolites while 13 included ratios (see Supporting Information Table S1 for a complete list and details of the studies). Of these, 16 studies included children (18 years and younger), 7 reported using only adult participants (19 years and older), and 7 studies included both child and adult participants. Results from these studies are confusing and often contradictory, perhaps because of the lack of consistency in methodology across the field.

Despite using a well-matched ASD and TD participant pool, our study also had a few limitations, such as medication use in some of the ASD participants. Medications could potentially alter brain metabolite levels; and differences in neurochemical levels could have been changed or masked by them. In addition, nutrition data were not available for the included participants, but should be taken into consideration in future studies as nutrition could potentially impact neurochemical concentration. In addition, none of the between-group differences reported in our study survive Bonferroni correction. Considering the metabolites measured are from the same individuals and the same two brain regions, the measures are likely not independent from one another; thus a Bonferroni correction may reduce our power to detect real differences. Nevertheless, the findings of this study provide evidence for significant metabolic and cellular dysfunction in the cingulate cortex in ASD which may have an impact on neuronal quality, myelination, and connectivity. These findings are important not only in better understanding the basic neuropathology in autism, but also in thinking about targeted clinical and pharmacological intervention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank our funding source: the UAB College of Arts and Sciences Interdisciplinary Innovation Award to R.K. The authors would also like to thank Thomas DeRamus, Hrishikesh Deshpande, and Dr. Nina Kraguljac for their assistance in the data collection and comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. Finally, the authors thank all participants and families for taking part in this study. The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web-site:

Table S1. Table showing the list of previous MR spectroscopy studies of autism with detailed information on participants, imaging sequence, analysis, and main findings.

References

- Abell F, Krams M, Ashburner J, Passingham R, Friston K, Frackowiak R, … Frith U (1999). The neuroanatomy of autism: A voxel-based whole brain analysis of structural scans. Neuroreport, 10, 1647–1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agam Y, Joseph RM, Barton JJ, & Manoach DS (2010). Reduced cognitive control of response inhibition by the anterior cingulate cortex in autism spectrum disorders. Neuroimage, 52, 336–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostou E, & Taylor M (2011). Review of neuroimaging in autism spectrum disorders: What have we learned and where we go from here. Molecular Autism, 2, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assaf M, Jagannathan K, Calhoun VD, Miller L, Stevens MC, Sahl R, … Pearlson GD (2010). Abnormal functional connectivity of default mode sub-networks in autism spectrum disorder patients. Neuroimage, 53, 247–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker PB, Hearshen DO, & Boska MD (2001). Single-voxel proton MRS of the human brain at 1.5 T and 3.0 T. Magnetic resonance in medicine, 45, 765–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnea-Goraly N, Kwon H, Menon V, Eliez S, Lotspeich L, & Reiss AL (2004). White matter structure in autism: Preliminary evidence from diffusion tensor imaging. Biological psychiatry, 55, 323–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman ML, & Kemper TL (1994). The neuroanatomy of the brain in autism In Bauman ML & Kemper TL (Eds.), The Neurobiology of Autism (pp. 119–145). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bejjani A, O’Neill J, Kim JA, Frew AJ, Yee VW, Ly R, … Toga AW (2012). Elevated glutamatergic compounds in pregenual anterior cingulate in pediatric autism spectrum disorder demonstrated by 1H MRS and 1H MRSI. PloS one, 7, e38786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi S, Anagnostou E, Shen J, Kolevzon A, Buxbaum JD, Hollander E, … Fan J (2011). In vivo 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy study of the attentional networks in autism. Brain Research, 1380, 198–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks W, Sabet A, Sibbitt W Jr., Barker P, Van Zijl P, Duyn J, & Moonen C (1997). Neurochemistry of brain lesions determined by spectroscopic imaging in systemic lupus erythematosus. The Journal of Rheumatology, 24, 2323–2329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks WM, Stidley CA, Petropoulos H, Jung RE, Weers DC, Friedman SD, … Yeo RA (2000). Metabolic and cognitive response to human traumatic brain injury: A quantitative proton magnetic resonance study. Journal of Neurotrauma, 17, 629–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MS, Singel D, Hepburn S, & Rojas DC (2013). Increased glutamate concentration in the auditory cortex of persons with autism and first-degree relatives: A 1H-MRS study. Autism Research, 6, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherkassky VL, Kana RK, Keller TA, & Just MA (2006). Functional connectivity in a baseline resting-state network in autism. Neuroreport, 17, 1687–1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu PH, Kayali MA, Kishida KT, Tomlin D, Klinger LG, Klinger MR, & Montague PR (2008). Self responses along cingulate cortex reveal quantitative neural phenotype for high-functioning autism. Neuron, 57, 463–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle J, Leski M, & Morrison J (2002). The diverse roles of L-glutamic acid in brain signal transduction. In Davis K, Charney D, & Coyle J (Eds.) (pp. 71–90). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Danielsen E, & Ross B (1999). Magnetic resonance spectroscopy diagnosis of neurological diseases. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- de la Fuente-Sandoval C, León-Ortiz P, Favila R, Stephano S, Mamo D, Ramírez-Bermúdez J, & Graff-Guerrero A (2011). Higher levels of glutamate in the associative-striatum of subjects with prodromal symptoms of schizophrenia and patients with first-episode psychosis. Neuropsychopharmacology, 36, 1781–1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Stefano N, Matthews PM, Fu L, Narayanan S, Stanley J, Francis GS, … Arnold DL (1998). Axonal damage correlates with disability in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Results of a longitudinal magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Brain, 121, 1469–1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch SI, Urbano MR, Neumann SA, Burket JA, & Katz E (2010). Cholinergic abnormalities in autism: Is there a rationale for selective nicotinic agonist interventions? Clinical Neuropharmacology, 33, 114–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVito TJ, Drost DJ, Neufeld RW, Rajakumar N, Pavlosky W, Williamson P, & Nicolson R (2007). Evidence for cortical dysfunction in autism: A proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging study. Biological Psychiatry, 61, 465–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle-Thomas KA, Card D, Soorya LV, Ting Wang A, Fan J, & Anagnostou E (2014). Metabolic mapping of deep brain structures and associations with symptomatology in autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8, 44–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayed N, Olmos S, Morales H, & Modrego PJ (2006). Physical basis of magnetic resonance spectroscopy and its application to central nervous system diseases. American Journal of Applied Sciences, 3, 1836–1845. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson KJ, MacLullich AM, Marshall I, Deary IJ, Starr JM, Seckl JR, & Wardlaw JM (2002). Magnetic resonance spectroscopy and cognitive function in healthy elderly men. Brain, 125, 2743–2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fransson P, & Marrelec G (2008). The precuneus/posterior cingulate cortex plays a pivotal role in the default mode network: Evidence from a partial correlation network analysis. NeuroImage, 42, 1178–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman S, Shaw D, Artru A, Richards T, Gardner J, Dawson G, … Dager S (2003). Regional brain chemical alterations in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Neurology, 60, 100–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SD, Brooks WM, Jung RE, Hart BL, & Yeo RA (1998). Proton MR spectroscopic findings correspond to neuropsychological function in traumatic brain injury. American Journal of Neuroradiology, 19, 1879–1885. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii E, Mori K, Miyazaki M, Hashimoto T, Harada M, & Kagami S (2010). Function of the frontal lobe in autistic individuals: A proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic study. Journal of Medical Investigation, 57, 35–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geurts JJ, Barkhof F, Castelijns JA, Uitdehaag BM, Polman CH, & Pouwels PJ (2004). Quantitative 1H-MRS of healthy human cortex, hippocampus, and thalamus: Metabolite concentrations, quantification precision, and reproducibility. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 20, 366–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardan AY, Minshew NJ, Melhem NM, Srihari S, Jo B, Bansal R, … Stanley JA (2008). An MRI and proton spectroscopy study of the thalamus in children with autism. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 163, 97–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haznedar MM, Buchsbaum MS, Metzger M, Solimando A, Spiegel-Cohen J, & Hollander E (1997). Anterior cingulate gyrus volume and glucose metabolism in autistic disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 154, 1047–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haznedar MM, Buchsbaum MS, Wei T-C, Hof PR, Cartwright C, Bienstock CA, & Hollander E (2000). Limbic circuitry in patients with autism spectrum disorders studied with positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 1994–2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horder J, Lavender T, Mendez M, O’Gorman R, Daly E, Craig M, … Murphy D (2013). Reduced subcortical glutamate/glutamine in adults with autism spectrum disorders: A [1H] MRS study. Translational Psychiatry, 3, e279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ipser JC, Syal S, Bentley J, Adnams CM, Steyn B, & Stein DJ (2012). 1H-MRS in autism spectrum disorders: A systematic meta-analysis. Metabolic Brain Disease, 27, 275–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isacson O (1993). On neuronal health. Trends in Neurosciences, 16, 306–308. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90104-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamain S, Betancur C, Quach H, Philippe A, Fellous M, Giros B, … Bourgeron T (2002). Linkage and association of the glutamate receptor 6 gene with autism. Molecular Psychiatry, 7, 302–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang J, Kwon J, Jang D, Moon W-J, Lee J-M, Ha T, … Kim S (2006). A proton MRSI study of brain N-acetylaspartate level after 12 weeks of citalopram treatment in drug-naive patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(7), 1202–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiru F, Skoch A, Klose U, Grodd W, & Hajek M (2006). Error images for spectroscopic imaging by LCModel using Cramer-Rao bounds. Magma, 19, 1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10334-005-0018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi G, Biederman J, Wozniak J, Goldin RL, Crowley D, Furtak S, … Gönenç A (2013). Magnetic resonance spectroscopy study of the glutamatergic system in adolescent males with high-functioning autistic disorder: A pilot study at 4T. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 263, 379–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jou RJ, Jackowski AP, Papademetris X, Rajeevan N, Staib LH, & Volkmar FR (2011). Diffusion tensor imaging in autism spectrum disorders: Preliminary evidence of abnormal neural connectivity. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 45, 153–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung RE, Brooks WM, Yeo RA, Chiulli SJ, Weers DC, & Sibbitt WL (1999). Biochemical markers of intelligence: A proton MR spectroscopy study of normal human brain. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 266, 1375–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kana RK, Keller TA, Minshew NJ, & Just MA (2007). Inhibitory control in high-functioning autism: Decreased activation and underconnectivity in inhibition networks. Biological psychiatry, 62, 198–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan O, Shen Y, Caon C, Bao F. e., Ching W, Reznar M, … Lisak R (2005). Axonal metabolic recovery and potential neuroprotective effect of glatiramer acetate in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis, 11, 646–651. doi: 10.1191/1352458505ms1234oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinhans NM, Richards T, Sterling L, Stegbauer KC, Mahurin R, Johnson LC, … Aylward E (2008). Abnormal functional connectivity in autism spectrum disorders during face processing. Brain, 131, 1000–1012. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubas B, Kułak W, Sobaniec W, Tarasow E, Łebkowska U, & Walecki J (2012). Metabolite alterations in autistic children: A 1H MR spectroscopy study. Advances in Medical Sciences, 57, 152–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Sundaram SK, Sivaswamy L, Behen ME, Makki MI, Ager J, … Chugani DC (2010). Alterations in frontal lobe tracts and corpus callosum in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Cerebral Cortex, 20, 2103–2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leech R, & Sharp DJ (2014). The role of the posterior cingulate cortex in cognition and disease. Brain, 137, 12–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt JG, O’Neill J, Blanton RE, Smalley S, Fadale D, McCracken JT, … Alger JR (2003). Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging of the brain in childhood autism. Biological Psychiatry, 54, 1355–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo MV, Chakrabarti B, Bullmore ET, Sadek SA, Pasco G, Wheelwright SJ, … Baron-Cohen S (2010). Atypical neural self-representation in autism. Brain, 133, 611–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, Cook EH Jr., Leventhal BL, DiLavore PC, … Rutter M (2000). The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule—Generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30, 205–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna B, Minshew N, Garver K, Lazar N, Thulborn K, Eddy W, & Sweeney J (2002). Neocortical system abnormalities in autism An fMRI study of spatial working memory. Neurology, 59, 834–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch CJ, Uddin LQ, Supekar K, Khouzam A, Phillips J, & Menon V (2013). Default mode network in childhood autism: Posteromedial cortex heterogeneity and relationship with social deficits. Biological Psychiatry, 74, 212–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddock RJ, & Buonocore MH (2012). MR spectroscopic studies of the brain in psychiatric disorders. Current Topics in Behavioral Neuroscience, 11, 199–251, doi: 10.1007/7854_2011_197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhavarao CN, & Namboodiri AM (2006). NAA synthesis and functional roles In Moffett R, Tieman SB, Weinberger DR, Coyle JT, & Namboodiri MA (Eds.), N-Acetylaspartate: A Unique Neuronal Molecule in the Central Nervous System (pp. 49–66). New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Manent J-B, & Represa A (2007). Neurotransmitters and brain maturation: Early paracrine actions of GABA and glutamate modulate neuronal migration. The Neuroscientist, 13, 268–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew SJ, Price RB, Mao X, Smith EL, Coplan JD, Charney DS, & Shungu DC (2008). Hippocampal N-acetylaspartate concentration and response to riluzole in generalized anxiety disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 63, 891–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyerhoff DJ, MacKay S, Bachman L, Poole N, Dillon WP, Weiner MW, & Fein G (1993). Reduced brain N-acetylaspartate suggests neuronal loss in cognitively impaired human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive individuals: In vivo 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging. Neurology, 43, 509–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BL, Changl L, Booth R, Ernst T, Cornford M, Nikas D, … Jenden DJ (1996). In vivo 1H MRS choline: Correlation with in vitro chemistry/histology. Life Sciences, 58, 1929–1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minshew NJ, & Williams DL (2007). The new neurobiology of autism: Cortex, connectivity, and neuronal organization. Archives of Neurology, 64, 945–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffett JR, Ross B, Arun P, Madhavarao CN, & Namboodiri A (2007). N-Acetylaspartate in the CNS: From neurodiagnostics to neurobiology. Progress in Neurobiology, 81, 89–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk CS, Peltier SJ, Wiggins JL, Weng S-J, Carrasco M, Risi S, & Lord C (2009). Abnormalities of intrinsic functional connectivity in autism spectrum disorders. Neuroimage, 47, 764–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostert JP, Sijens PE, Oudkerk M, & De Keyser J (2006). Fluoxetine increases cerebral white matter NAA/Cr ratio in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neuroscience Letters, 402, 22–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DG, Critchley HD, Schmitz N, McAlonan G, van Amelsvoort T, Robertson D, … Simmons A (2002). Asperger syndrome: A proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study of brain. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59, 885–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordin V, Lekman A, Johansson M, Fredman P, & Gillberg C (1998). Gangliosides in cerebrospinal fluid in children with autism spectrum disorders. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 40, 587–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noriuchi M, Kikuchi Y, Yoshiura T, Kira R, Shigeto H, Hara T, … Kamio Y (2010). Altered white matter fractional anisotropy and social impairment in children with autism spectrum disorder. Brain Research, 1362, 141–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oblak AL, Gibbs TT, & Blatt GJ (2011). Reduced GABA A receptors and benzodiazepine binding sites in the posterior cingulate cortex and fusiform gyrus in autism. Brain Research, 1380, 218–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oblak AL, Rosene DL, Kemper TL, Bauman ML, & Blatt GJ (2011). Altered posterior cingulate cortical cyctoarchitecture, but normal density of neurons and interneurons in the posterior cingulate cortex and fusiform gyrus in autism. Autism Research, 4, 200–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi T, Matsuda H, Hashimoto T, Kunihiro T, Nishikawa M, Uema T, & Sasaki M (2000). Abnormal regional cerebral blood flow in childhood autism. Brain, 123, 1838–1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield RC (1971). The assessment and analysis of handedness: The Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia, 9, 97–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oner O, Devrimci-Ozguven H, Oktem F, Yagmurlu B, Baskak B, & Munir K (2007). Proton MR spectroscopy: Higher right anterior cingulate N-acetylaspartate/choline ratio in Asperger syndrome compared with healthy controls. American Journal of Neuroradiology, 28, 1494–1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page L, Daly E, Schmitz N, Simmons A, Toal F, Deeley Q, … Murphy D (2006). In vivo 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy study of amygdala-hippocampal and parietal regions in autism. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163, 2189–2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri L, Papaleo V, Porcelli V, Scarcia P, Gaita L, Sacco R, … Manzi B (2010). Altered calcium homeostasis in autism-spectrum disorders: Evidence from biochemical and genetic studies of the mitochondrial aspartate/glutamate carrier AGC1. Molecular Psychiatry, 15, 38–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardini M, Garaci F, Bonzano L, Roccatagliata L, Palmieri M, Pompili E, … Floris R (2009). White matter reduced streamline coherence in young men with autism and mental retardation. European Journal of Neurology, 16, 1185–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel T, & Talcott JB (2014). Moderate relationships between NAA and cognitive ability in healthy adults: Implications for cognitive spectroscopy. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce K, & Redcay E (2008). Fusiform function in children with an autism spectrum disorder is a matter of “who”. Biological Psychiatry, 64, 552–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provencher SW (1993). Estimation of metabolite concentrations from localized in vivo proton NMR spectra. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 30, 672–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provencher SW (2001). Automatic quantitation of localized in vivo 1H spectra with LCModel. NMR Biomedicine, 14, 260–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell A, Jeon O, Zimmerman A, Blue M, & Pevsner J (2001). Postmortem brain abnormalities of the glutamate neurotransmitter system in autism. Neurology, 57, 1618–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramoz N, Reichert JG, Smith CJ, Silverman JM, Bespalova IN, Davis KL, & Buxbaum JD (2004). Linkage and association of the mitochondrial aspartate/glutamate carrier SLC25A12 gene with autism. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161, 662–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigotti DJ, Kirov II, Djavadi B, Perry N, Babb JS, & Gonen O (2011). Longitudinal whole-brain N-acetylaspartate concentration in healthy adults. American Journal of Neuroradiology, 32, 1011–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinehart NJ, Bradshaw JL, Brereton AV, & Tonge BJ (2001). Movement preparation in high-functioning autism and Asperger disorder: A serial choice reaction time task involving motor reprogramming. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31, 79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritvo AR (2013). RAADS-R. In Encyclopedia of Autism Spectrum Disorders (pp. 2489–2490). New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Ritvo RA, Ritvo ER, Guthrie D, Ritvo MJ, Hufnagel DH, McMahon W, … Attwood T (2011). The Ritvo Autism asperger diagnostic scale-revised (RAADS-R): A scale to assist the diagnosis of Autism spectrum disorder in adults: An international validation study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41, 1076–1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross AJ, & Sachdev PS (2004). Magnetic resonance spectroscopy in cognitive research. Brain Research Reviews, 44, 83–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross AJ, Sachdev PS, Wen W, Valenzuela MJ, & Brodaty H (2005). Cognitive correlates of 1H MRS measures in the healthy elderly brain. Brain Research Bulletin, 66, 9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross B, & Bluml S (2001). Magnetic resonance spectroscopy of the human brain. The Anatomical Record, 265, 54–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossignol D, & Frye R (2012). Mitochondrial dysfunction in autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Molecular Psychiatry, 17, 290–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman DL, Behar KL, Hyder F, & Shulman RG (2003). In vivo NMR studies of the glutamate neurotransmitter flux and neuroenergetics: Implications for brain function. Annual Review of Physiology, 65, 401–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudie JD, Hernandez LM, Brown JA, Beck-Pancer D, Colich NL, Gorrindo P, … Levitt P (2012). Autism-associated promoter variant in MET impacts functional and structural brain networks. Neuron, 75, 904–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Le Couteur A, & Lord C (2003). Autism diagnostic interview-revised. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Schumann CM, Bloss CS, Barnes CC, Wideman GM, Carper RA, Akshoomoff N, … Lord C (2010). Longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging study of cortical development through early childhood in autism. The Journal of Neuroscience, 30, 4419–4427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segurado R, Conroy J, Meally E, Fitzgerald M, Gill M, & Gallagher L (2005). Confirmation of association between autism and the mitochondrial aspartate/glutamate carrier SLC25A12 gene on chromosome 2q31. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 2182–2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serajee F, Zhong H, Nabi R, & Huq AM (2003). The metabotropic glutamate receptor 8 gene at 7q31: Partial duplication and possible association with autism. Journal of Medical Genetics, 40, e42–e42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih P, Keehn B, Oram JK, Leyden KM, Keown CL, & Müller R-A (2011). Functional differentiation of posterior superior temporal sulcus in autism: A functional connectivity magnetic resonance imaging study. Biological Psychiatry, 70, 270–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohe A, Hashimoto K, Nakamura K, Tsujii M, Iwata Y, Tsuchiya KJ, … Sugihara G. i. (2006). Increased serum levels of glutamate in adult patients with autism. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 30, 1472–1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuang M, Liu J, Jia MX, Yang JZ, Wu SP, Gong XH, … Zhang D (2004). Family-based association study between autism and glutamate receptor 6 gene in Chinese Han trios. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics, 131, 48–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon M, Ozonoff SJ, Ursu S, Ravizza S, Cummings N, Ly S, & Carter CS (2009). The neural substrates of cognitive control deficits in autism spectrum disorders. Neuropsychologia, 47, 2515–2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stankoff B, Tourbah A, Suarez S, Turell E, Stievenart J, Payan C, … Bricaire F (2001). Clinical and spectroscopic improvement in HIV-associated cognitive impairment. Neurology, 56, 112–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley JA (2002). In vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy and its application to neuropsychiatric disorders. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue canadienne de psychiatrie, 47, 315–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K, Nishimura K, Sugihara G, Nakamura K, Tsuchiya KJ, Matsumoto K, … Sugiyama T (2010). Metabolite alterations in the hippocampus of high-functioning adult subjects with autism. The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 13, 529–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakkar KN, Polli FE, Joseph RM, Tuch DS, Hadjikhani N, Barton JJ, & Manoach DS (2008). Response monitoring, repetitive behaviour and anterior cingulate abnormalities in autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Brain, 131, 2464–2478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela M, Sachdev P, Wen W, Shnier R, Brodaty H, & Gillies D (2000). Dual voxel proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in the healthy elderly: Subcortical-frontal axonal N-acetylaspartate levels are correlated with fluid cognitive abilities independent of structural brain changes. Neuroimage, 12, 747–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Elst LT, Maier S, Fangmeier T, Endres D, Mueller G, Nickel K, … Biscaldi M (2014). Disturbed cingulate glutamate metabolism in adults with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder: Evidence in support of the excitatory/inhibitory imbalance hypothesis. Molecular Psychiatry, 19, 1314–1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas DL, Nascimbene C, Krishnan C, Zimmerman AW, & Pardo CA (2005). Neuroglial activation and neuroinflammation in the brain of patients with autism. Annals of Neurology, 57, 67–81. doi: 10.1002/ana.20315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos MM, Brito AR, Domingues RC, Da Cruz LCH, Gasparetto EL, Werner J, & Gonçalves JPS (2008). Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in school-aged autistic children. Journal of Neuroimaging, 18, 288–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt BA, Finch DM, & Olson CR (1992). Functional heterogeneity in cingulate cortex: The anterior executive and posterior evaluative regions. Cerebral Cortex, 2, 435–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waagepetersen HS, Sonnewald U, & Schousboe A (2007). Glutamine, Glutamate, and GABA: metabolic aspects In Lajtha A, Oja S, Schousboe A, & Saransaari P (Eds), Handbook of Neurochemistry and Molecular Neurobiology: Amino Acids and Peptides in the Nervous System, pp. 1–21. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D (1999). Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Weiduschat N, Mao X, Hupf J, Armstrong N, Kang G, Lange D, … Shungu D (2014). Motor cortex glutathione deficit in ALS measured in vivo with the J-editing technique. Neuroscience Letters, 570, 102–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng S-J, Wiggins JL, Peltier SJ, Carrasco M, Risi S, Lord C, & Monk CS (2010). Alterations of resting state functional connectivity in the default network in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Brain Research, 1313, 202–214. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.11.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi Z-X, Baker DA, Shen H, Carson DS, & Kalivas PW (2002). Group II metabotropic glutamate receptors modulate extracellular glutamate in the nucleus accumbens. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 300, 162–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuksel C, & Ongur D (2010). Magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies of glutamate-related abnormalities in mood disorders. Biological Psychiatry, 68, 785–794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Ramadan E, Cappiello M, Wroblewska B, Bzdega T, & Neale JH (2001). NAAG inhibits KCl-induced [3H]-GABA release via mGluR3, cAMP, PKA and L-type calcium conductance. European Journal of Neuroscience, 13, 340–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.