Abstract

Background

Patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer often have a detriment in health-related quality of life (HRQoL). In the randomized, double-blind, phase III POLO trial progression-free survival was significantly longer with maintenance olaparib, a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor, than placebo in patients with a germline BRCA1 and/or BRCA2 mutation (gBRCAm) and metastatic pancreatic cancer whose disease had not progressed during first-line platinum-based chemotherapy. The prespecified HRQoL evaluation is reported here.

Patients and methods

Patients were randomized to receive maintenance olaparib (300 mg b.i.d.; tablets) or placebo. HRQoL was assessed using the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30-item module at baseline, every 4 weeks until disease progression, at discontinuation, and 30 days after last dose. Scores ranged from 0 to 100; a ≥10-point change or difference between arms was considered clinically meaningful. Adjusted mean change from baseline was analysed using a mixed model for repeated measures. Time to sustained clinically meaningful deterioration (TSCMD) was analysed using a log-rank test.

Results

Of 154 randomized patients, 89 of 92 olaparib-arm and 58 of 62 placebo-arm patients were included in HRQoL analyses. The adjusted mean change in Global Health Status (GHS) score from baseline was <10 points in both arms and there was no significant between-group difference [−2.47; 95% confidence interval (CI) −7.27, 2.33; P = 0.31]. Analysis of physical functioning scores showed a significant between-group difference (−4.45 points; 95% CI −8.75, −0.16; P = 0.04). There was no difference in TSCMD for olaparib versus placebo for GHS [P = 0.25; hazard ratio (HR) 0.72; 95% CI 0.41, 1.27] or physical functioning (P = 0.32; HR 1.38; 95% CI 0.73, 2.63).

Conclusions

HRQoL was preserved with maintenance olaparib treatment with no clinically meaningful difference compared with placebo. These results support the observed efficacy benefit of maintenance olaparib in patients with a gBRCAm and metastatic pancreatic cancer.

ClincalTrials.gov number

Keywords: pancreatic cancer, health-related quality of life, olaparib, BRCA, metastatic

Key Message

In the POLO trial, the high baseline health-related quality of life scores, assessed by EORTC QLQ-C30, were preserved during maintenance treatment with olaparib in patients with a germline BRCA1 and/or BRCA2 mutation and metastatic pancreatic cancer whose disease had not progressed during treatment with first-line platinum-based chemotherapy.

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is the 13th most common cancer and 7th most common cause of cancer death worldwide [1]. Patients often present with advanced disease with worldwide 5-year survival rates of 9%, reducing to 3% for metastatic pancreatic cancer [2]. Median progression-free survival (PFS) with standard-of-care first-line treatments is around 6 months and disease progression can result in deterioration in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [3, 4]. As a consequence, patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer have reduced HRQoL due to high emotional burden, symptom burden (in particular pain, fatigue, vomiting and diarrhoea), and poor prognosis [5–10]. When evaluating the best treatment option for patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer, it is important to not only assess survival, which is relatively short, but also ensure that there are no detrimental effects of treatment on HRQoL. Indeed, American Society for Clinical Oncology guidelines on treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer recommend that clinicians should proactively discuss quality of life issues such as pain, fatigue, and loss of appetite, which tend to be overlooked yet have significant impact on daily life, with their patients [11].

In the international, randomized, placebo-controlled phase III POLO trial patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer and a germline BRCA1 and/or BRCA2 mutation (gBRCAm) whose disease had not progressed on first-line platinum-based chemotherapy derived a statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement in PFS from maintenance treatment with the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib versus placebo [12]. The aim of maintenance treatment is to prolong PFS, and ultimately overall survival, delaying the need for subsequent cytotoxic chemotherapy. In addition, maintenance treatment should seek to preserve HRQoL, which may be improved following effective first-line chemotherapy [13]. First-line treatment with FOLFIRINOX has been shown to improve overall HRQoL and lead to a decrease in some symptoms, including pain, for patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer [13]. A prespecified secondary objective of the POLO trial was to evaluate the effect of olaparib on HRQoL, specifically the adjusted mean change from baseline in Global Health Status (GHS) score using the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30-item module (EORTC QLQ-C30).

Methods

Patient population and study design

Details of this randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial have been reported previously [12]. Briefly, patients aged ≥18 years with histologically or cytologically confirmed pancreatic adenocarcinoma and a documented deleterious or suspected deleterious gBRCAm were eligible. Patients had received ≥16 weeks of continuous first-line platinum-based chemotherapy for metastatic pancreatic cancer, although duration was unlimited as long as no evidence of disease progression was noted by the investigator at randomization. Patients were randomized in a 3 : 2 ratio to receive maintenance olaparib tablets (300 mg twice daily) or matching placebo, initiated 4–8 weeks after the last dose of first-line chemotherapy and continued until objective radiologic disease progression (investigator-assessed according to modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors v1.1) or unacceptable toxicity [14]. Crossover to olaparib was not permitted during the trial.

Study outcome measures

A prespecified secondary objective of the POLO study was to assess HRQoL using the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire. Additional HRQoL data were collected using the pancreatic cancer specific EORTC QLQ-PAN26 questionnaire (data not reported here). These questionnaires are considered appropriate to assess the pancreatic cancer patient experience [15]. The EORTC QLQ-C30 includes a two-item GHS scale, five multi-item functioning scales, three multi-item symptom scales, five single-item symptom scales, and a single-item financial impact scale [16]. Raw scores were transformed on to a scale ranging from 0 to 100; transformed scores are reported here. For GHS and functioning scales, a higher score is indicative of better quality of life whereas for symptom scales a higher score is indicative of more severe symptoms. A change from baseline of ≥10 points was predefined as clinically meaningful, based on the published literature [17–19]. Assessments were undertaken at baseline, every 4 weeks until disease progression, at discontinuation of study treatment, and 30 days after last dose. The primary HRQoL end point was adjusted mean change from baseline in GHS score. Best HRQoL response (improvement, no change, or deterioration), the proportion of patients with a clinically meaningful change (defined as a ≥10-point change from baseline) and time to sustained clinically meaningful deterioration (TSCMD) were secondary HRQoL end points. A TSCMD event was defined as a ≥10-point decrease (GHS and functioning subscales) or increase (symptom subscales) from baseline (or a patient being too ill to complete the questionnaire) sustained at the next scheduled visit with no response of ‘improved’ or ‘no change’ in between the two visit responses of ‘deterioration’, or death. In addition to the GHS score evaluation, exploratory analyses of functioning scores (physical, role, cognitive, emotional, and social) and patient-reported symptoms (pain, fatigue, nausea and vomiting, appetite loss and insomnia) were prespecified. Results from datasets considered to be most clinically relevant (GHS, physical functioning, and symptom subscales) are reported here.

Statistical analysis

HRQoL data were analysed in the subset of patients in the intention-to-treat population who had an evaluable baseline EORTC QLQ-C30 or QLQ-PAN26 form [patient-reported outcome (PRO) analysis set]. An evaluable form was defined as one on which at least one subscale baseline score could be determined.

For the adjusted mean change from baseline in GHS score analysis, only visits with at least 25% non-missing values in each treatment arm were included; study treatment discontinuation and 30 days following last dose of study treatment visits were excluded. The analysis was carried out using a linear mixed model for repeated measures, adjusted for score at baseline, time, and treatment-by-time interaction to estimate the cumulative effect of olaparib versus placebo on GHS. Between-group differences were compared using adjusted mean estimates for each treatment group with a between-group difference of ≥10 points defined as clinically meaningful, based on published literature [17–19]. A change of ≥10 points from baseline was also predefined as clinically meaningful [17–19]. TSCMD was analysed by log-rank test [hazard ratio (HR) <1 favours olaparib] in all patients with a baseline score ≥10 (GHS and functioning subscale analyses) or ≤90 (symptom subscales). HRQoL improvement rates were analysed using a logistic regression model [odds ratio (OR) >1 favours olaparib].

Results

Population characteristics

Baseline characteristics of randomized patients are reported in the primary manuscript [12].

Of 154 randomized patients, 89 of 92 who received olaparib and 58 of 62 who received placebo were included in the PRO analysis set; the remaining seven patients had missing baseline forms. HRQoL scores were well-balanced between treatment groups at baseline with overall high scores for GHS and physical functioning scales, and low scores for symptom scales (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Questionnaire compliance

The overall compliance rate for EORTC QLQ-C30 was high, 100% at baseline and 96.6% and 94.8% overall in the olaparib and placebo groups, respectively, based on the PRO analysis set (supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online).

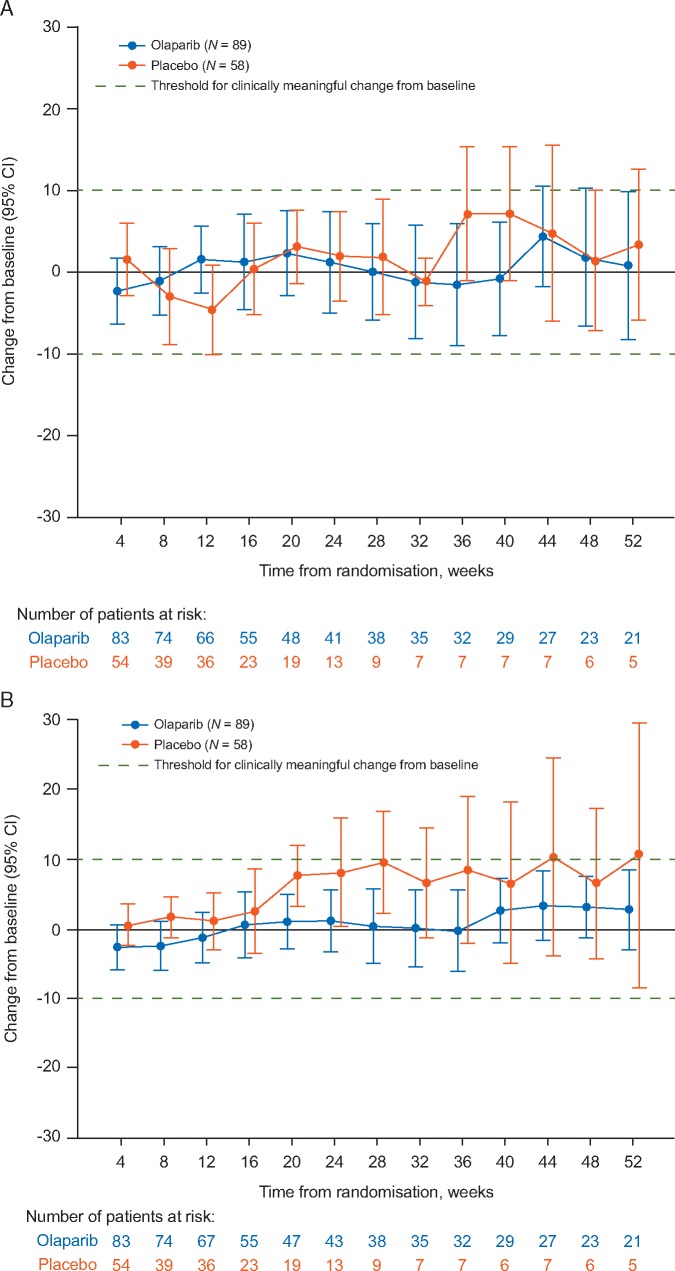

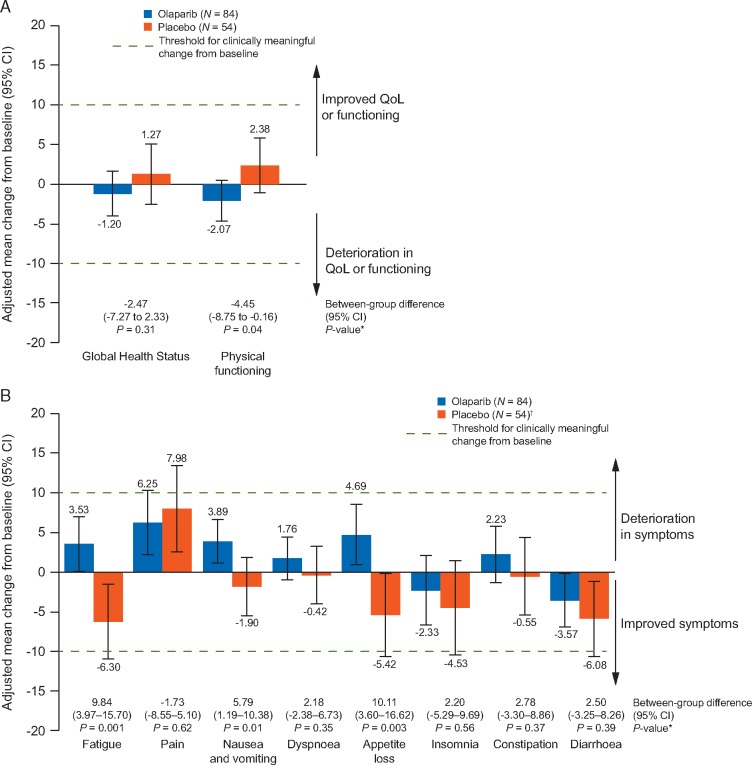

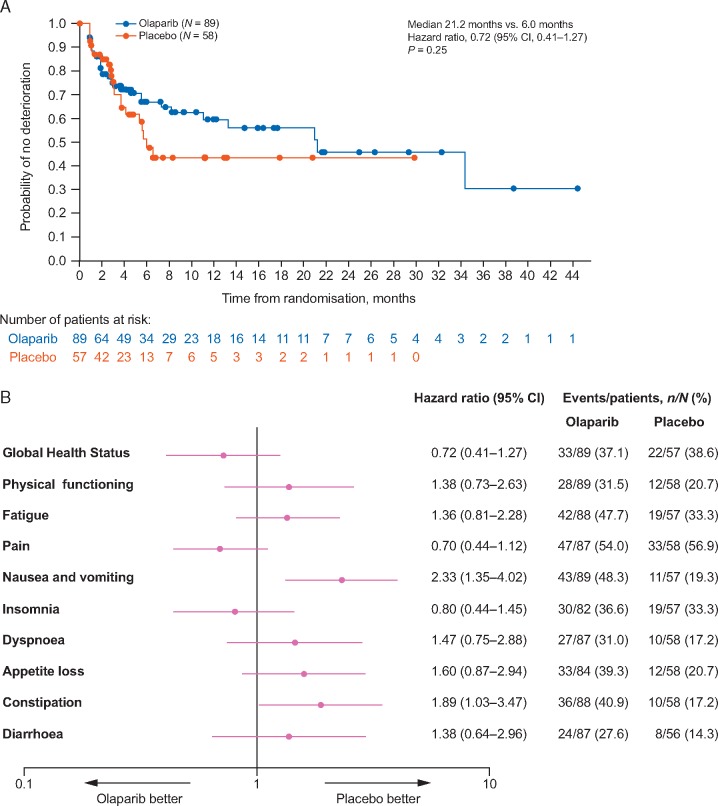

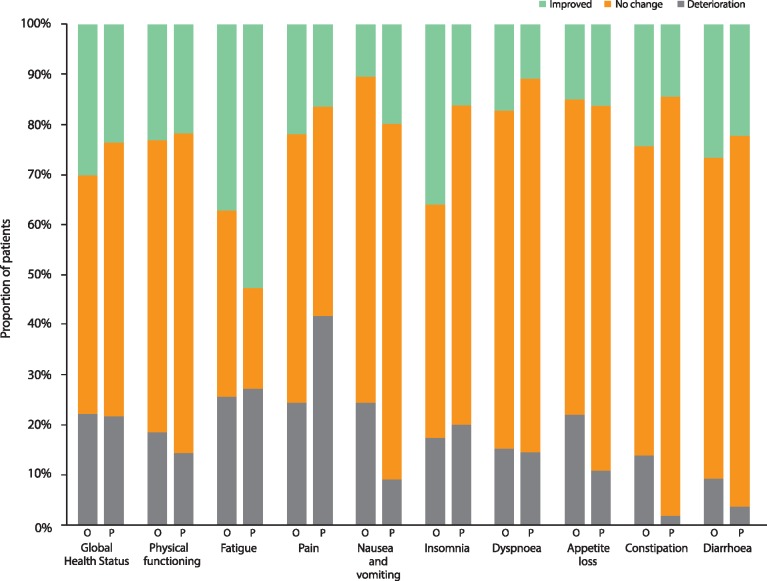

Global Health Status

Mean baseline scores for GHS were high compared with those from other metastatic pancreatic cancer trials [13]; 70.4 in the olaparib and 74.3 in the placebo group (supplementary Figure S1A, available at Annals of Oncology online). GHS scores remained relatively stable over time for both treatment groups (Figure 1A). There was no statistically significant difference in overall between-group adjusted mean change from baseline for GHS score [between-group difference −2.47; 95% confidence interval (CI) −7.27, 2.33; P = 0.31] calculated across the first 6 months of treatment (Figure 2A). The median TSCMD for GHS score was 21.2 months for olaparib and 6.0 months for placebo (HR 0.72; 95% CI 0.41, 1.27; P = 0.25) (Figure 3). A similar proportion of patients in each arm reported improvement in GHS score: 26/89 (29.2%) in the olaparib and 13/58 (22.4%) in the placebo group (OR 1.43; 95% CI 0.67, 3.15; P = 0.36) (Figure 4).

Figure 1.

Mean change from baseline in EORTC QLQ-C30 scores across timepoints, by treatment group for (A) Global Health Status and (B) physical functioning scores. A change from baseline of ≥10 points was predefined as clinically meaningful. Error bars denote 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 2.

Overall adjusted mean change from baseline in EORTC QLQ-C30 scores over the first 6 months of treatment (A) Global Health Status and physical functioning and (B) symptom scales. An adjusted mean change from baseline or between-group difference of ≥10 points was considered to be clinically meaningful. For each subscale, only visits with at least 25% non-missing values in each treatment arm were included, therefore analyses cover only the first 6 months of treatment. Error bars denote 95% confidence intervals. *Between-group differences were considered statistically significant if P<0.05. †For diarrhoea, N=53. CI, confidence interval; QoL, quality of life.

Figure 3.

Time to sustained clinically meaningful deterioration (A) Kaplan–Meier plot for EORTC QLQ-C30 Global Health Status and (B) Forest plot for EORTC QLQ-C30 Global Health Status, physical functioning and symptom scales. Patients with baseline scores ≥10 were included in analyses of Global Health Status and physical functioning scores; patients with baseline scores ≤90 were included in analyses of symptom scores. Patients who had not had a TSCMD event or who had a TSCMD event after two or more missed HRQoL assessment visits were censored at the time of their last HRQoL assessment where the respective score could be evaluated; however, patients were not censored if they had two missing visits between two evaluable HRQoL assessments (and the outcome of the second assessment was not deterioration) and subsequently went on to show sustained clinically meaningful deterioration. CI, confidence interval.

Figure 4.

Best overall quality of life response for EORTC QLQ-C30 Global Health Status, physical functioning and symptom scales. Percentages are calculated based on the 86 olaparib-arm patients and 55 placebo-arm patients (54 for the diarrhoea subscale) with available results. Three patients in each arm (4 placebo arm patients for the diarrhoea subscale) were included in the PRO analysis set, but had no evaluable baseline or post-baseline results and are excluded from this figure. O, olaparib; P, placebo.

Physical functioning

Mean baseline physical functioning scores were similarly high in both treatment groups and improved over time (supplementary Figure S1A, available at Annals of Oncology online; Figure 1B). The between-group difference in adjusted mean change from baseline for physical functioning was −4.45 points (95% CI −8.75, −0.16; P = 0.04) (Figure 2A). There was no statistically significant between-group difference in TSCMD for physical functioning (medians not reached; HR 1.38; 95% CI 0.73, 2.63; P = 0.32) (Figure 3B). The proportion of patients with best HRQoL responses of ‘improved’ or ‘deterioration’ for physical functioning was similar between arms (Figure 4). Analyses of role, emotional, cognitive and social functioning showed no between-group differences in adjusted mean change from baseline of ≥10-points and no statistically significant differences in TSCMD between arms.

Symptom subscales

Mean symptom scale scores were low at baseline, reflecting a low symptom burden (supplementary Figure S1B, available at Annals of Oncology online). For the symptom scales of fatigue, nausea and vomiting, and appetite loss between-group differences were statistically significant in favour of placebo. For fatigue, and nausea and vomiting the between-group difference was <10 points, whereas for appetite loss the between-group difference was 10.11 points (Figure 2B). There were no between-group differences in TSCMD for any symptom scores, except for nausea and vomiting, and constipation for which there were significant differences in favour of placebo (Figure 3B). Best HRQoL responses for symptom subscales are shown in Figure 4.

Discussion

Metastatic pancreatic cancer, which is the initial diagnosis for 50%–60% of pancreatic cancer patients, has a poor prognosis [20]. Therefore, treatment should focus not only on prolonging disease progression or improving survival but should also consider preserving or improving quality of life, because symptoms such as fatigue, pain, appetite and weight loss, and decreased functional status all have a detrimental impact on HRQoL for patients with this disease.

Patients were randomized into the POLO study following a minimum of 4 months of first-line platinum-based chemotherapy (although there was no maximum limit to the duration of platinum-based treatment) and patients whose disease had progressed during first-line chemotherapy were not eligible for this maintenance trial. With the exception of alopecia, peripheral neuropathy and anaemia, toxic effects from previous treatments must have resolved to grade 1 before randomization [12]. The majority of patients (84%) had received variants of FOLFIRINOX, which is known to significantly improve GHS over the first 6 months of treatment [12, 13]; in the seminal phase III study FOLFIRINOX improved mean GHS score from 53.8 at baseline to 68.3 at the end of 6 months of treatment [13]. It is therefore not surprising that patients in the POLO study had consistently higher baseline GHS and physical functioning scores and lower symptom severity than the general population of patients with gastrointestinal cancers, reflecting low disease burden following first-line chemotherapy [21]. The mean GHS score was 70.4 in the olaparib arm at baseline, consistent with expectations based on FOLFIRINOX data. Preservation of HRQoL is a major therapeutic goal in the maintenance setting and further improvement in comparison with placebo may not be expected. Furthermore, standard-of-care chemotherapy agents are often associated with cumulative treatment-emergent toxicities that further affect HRQoL and a potential decrease in GHS has been observed when FOLFIRINOX treatment is continued beyond 6 months [10, 13].

High baseline GHS scores in the POLO study were preserved with olaparib maintenance treatment and the primary HRQoL end point (adjusted mean change from baseline) showed no statistically significant or clinically meaningful difference between the olaparib and placebo groups. Furthermore, median TSCMD was longer in the olaparib (21.2 months) than the placebo group (6.0 months), although this difference was not statistically significant. This result may be influenced by a higher degree of censoring and smaller number of assessable patients (reflective of earlier disease progression) in the placebo arm compared with the olaparib arm. In addition, the proportion of patients with improved GHS score was similar in the olaparib (29.2%) and placebo groups (22.4%).

Evaluation of the physical functioning subscale indicated a significant between-group difference in adjusted mean change from baseline, favouring placebo; however, this difference was not considered to be clinically meaningful based on the 10-point change threshold [17–19] and high baseline scores were preserved with olaparib treatment. In addition, there were no clinically meaningful between-group differences in change from baseline for symptom scales, with the exception of appetite loss, which showed a clinically meaningful difference favouring placebo. The notable findings in appetite loss scores appear to be driven by an improvement of these symptoms in the placebo group, since appetite loss scores remained low and stable over time in the olaparib group. Furthermore, appetite loss is a recognised treatment-related symptom of olaparib [22]. Lower symptom scores indicate reduced symptom burden and all other symptom scores remained low during maintenance olaparib treatment.

A ≥10-point change from baseline in EORTC QLQ-C30 score was predefined as clinically meaningful, based on the published literature. A study designed to determine the significance to patients of HRQoL scores showed that a ≥10-point change from baseline in EORTC QLQ-C30 score generally reflected a change in quality of life that was ‘moderately’ or ‘very much’ better or worse [17] and was consistent with results from a systematic review of randomized controlled trials in various cancer settings, which demonstrated that a mean difference of 10–15 points in GHS score represented a medium effect size that was likely to be clinically relevant [18]. This 10-point threshold has been adopted for other studies based on EORTC QLQ-C30 data, including those in the pancreatic cancer setting, suggesting that it is an appropriate and generally accepted definition [19, 23, 24]; however, it is worth noting that at the time the POLO study was designed, there was no precedent for defining a clinically meaningful change in the maintenance setting.

In the POLO study, patients in the olaparib arm derived a statistically significant and clinically meaningful PFS benefit compared with placebo and a trend towards increased time to second progression was observed, suggesting the treatment benefit may be maintained through subsequent lines of therapy [12]. In addition, time to first subsequent therapy was significantly delayed in the olaparib arm [25]. Patients discontinued study treatment at disease progression and were only followed for HRQoL for 1 month after this point, therefore follow-up for HRQoL was considerably shorter in the placebo arm and the impact of disease progression, or any subsequent treatments, on HRQoL was not taken into account. Adjusted mean change from baseline analyses only included visits at which ≥25% of patients in each treatment arm had evaluable questionnaires; for the GHS analysis this equated to the first 6 months of treatment. This may mean that these analyses underestimate the overall impact of olaparib treatment in comparison with placebo, since disease progression and associated subsequent therapies would be expected to result in decreased HRQoL. Additional data assessing the psychological impact of having prolonged disease control (e.g. Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire or depression scale data) were not collected; however, the possibility of a positive benefit for this population of patients who had significantly improved PFS with maintenance olaparib may be considered.

Conclusions

HRQoL was preserved with olaparib maintenance therapy in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer and a gBRCAm whose disease had not progressed during first-line platinum-based chemotherapy, with no meaningful difference observed compared with placebo. Results of prespecified end points from the POLO trial show that maintenance olaparib significantly improved PFS without compromising quality of life, an important result for patients particularly when considering the cumulative toxicities of standard-of-care chemotherapies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients who participated in this trial, their families and our co-investigators. Medical writing assistance was provided by Elin Pyke, MChem, from Mudskipper Business Ltd, funded by AstraZeneca and Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA (MSD).

Funding

This study was sponsored by AstraZeneca and is part of an alliance between AstraZeneca and MSD (no grant number). This research was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30-17 CA008748.

Disclosure

PH reports grants received from AstraZeneca during the conduct of this study. Personal fees and grants from Celgene, Erythec, Halozyme, Novartis, Pfizer and Servier outside of the submitted work. HLK reports grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca during the conduct of this study. Personal fees from Aldeyra Therapuetics, Astellas, Erytech, Five Prime Therapeutics, Ipsen Pharmaceuticals, and Kyowa. Personal fees and non-financial support from Boehringer-Ingelheim and Paredox Therapeutics. Grants and personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb and MedImmune. Grants from Aduro, Bayer, Deciphera, Glaxo Smith Kline, Lilly, Polaris, and Verastem. Grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Merck outside the submitted work. MR reports grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Celgene, personal fees from Baxalta, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Novocure, Novartis, Shire and AstraZeneca and unpaid Steering Committee membership for Boston Pharmaceuticals, outside the submitted work. EvC reports grants from Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ipsen and Roche; grants and personal fees from Bayer, Celgene, Lilly, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Merck KGaA, Novartis, Roche and Servier; personal fees from AstraZeneca, and Bristol-Myers Squibb outside the submitted work. TM reports personal fees and non-financial support from Shire Pharmaceuticals, Servier, Sanofi, Celgene, Incyte, and H3 Biomedicine; personal fees from Roche, Baxter, QED Therapeutics and Amgen; grants from BeiGene; grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca outside the submitted work. MJH reports non-financial support and research collaboration only from Myriad Genetic Laboratories, Caris Life Science, Foundation Medicine, Invitae, and Ambry; non-financial support from Astra-Zeneca, outside the submitted work. JOP reports grants and personal fees from Celgene, personal fees from Shire/Servier, Merck Serono, and Sanofi, outside the submitted work. DA reports personal fees from AstraZeneca during the conduct of the study; personal fees and non-financial support from Bayer, BMS, MSD, Servier, Sanofi, Roche, and Sirtex; personal fees from Biocompatibles, Eli Lilly, and Terumo outside the submitted work. D-YO reports grants from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Novartis, Genentech/Roche, Merck Serono, Bayer, Taiho, ASLAN, and Halozyme, outside the submitted work. AR-S reports grants from AstraZeneca during the conduct of the study; grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Amgen, Celgene, Roche, and Servier; personal fees from Baxalta, BMS, MSD, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Shire, iomedico, Aurikamed, MCI, med publico, BSH, Promedicis, and BOVita; grants and non-financial support from Ipsen; grants and personal fees from Lilly, and Merck Serono; grants from AIO Studien gGmbH, Mologen Berlin, Boehringer, Pharma Consulting Group AB Sweden, and Syneed medidata GmbH outside the submitted work. GT reports personal fees from Celgene outside the submitted work. HA reports personal fees from Servier and Celgene; grants from Chugai; non-financial support from Lilly and Revolution Medicine outside the submitted work. EMO’R reports grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, grants from NCI, personal fees from Merck, during the conduct of the study; grants from ActaBiologica, Array, Genentech, MabVax, Novartis, OncoQuest, Polaris Puma, QED, and Roche; grants and personal fees from Agios, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Beigene, from BMS, Casi, Celgene, Exelixis, Halozyme, Incyte, and Lilly; personal fees from 3DMed, AlignMed, Amgen, Antengene, Aptus, Aslan, Astellas, Bioline, Boston Scientific, BridgeBio, CARsgen, Cipla, CytomX, Daiichi, Debiopharm, Delcath, Eisai, Genoscience, Hengrui, Inovio, Ipsen, Jazz, Janssen, Kyowa Kirin, LAM, Loxo, Merck, Mina, Novella, Onxeo, PCI Biotech, Pfizer, Pieris, RedHill, Sanofi, Servier, Silsenseed, SillaJen, Sobi, Targovax, Tekmira, TwoXAR, Vicus, Yakult, and Yiviva outside the submitted work. DH and DMcG have declared no conflicts of interest. KYC reports other funding from Merck & Co., Inc associated with the conduct of the study. SJ is an employee of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA and owns stock in Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA. HKY is an employee of AstraZeneca. NP is an employee of AstraZeneca and owns stock. TG reports personal fees from AstraZeneca during the conduct of the study; institutional research funding from AstraZeneca, and Merck MSD, consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, AbbVie, Bayer, Merck MSD and Teva, and has participated in speakers’ bureaus for AbbVie outside the submitted work.

Appendix

POLO Investigators

The table lists the principal investigator for each site who participated in the study.

| Country | Principal investigator |

|---|---|

| Australia | Lorraine Chantrill,a David Goldstein, Warren Joubert, Nick Pavlakis, Annette Tognela |

| Belgium | Eric Van Cutsem, Frank Van Fraeyenhove, Jean-Luc Van Laethem, Marc Peeters |

| Canada | Neesha Dhani, Petr Kavan, Frederic Lemay |

| France | Antoine Adenis,a Pascal Artru, Nabil Baba-Hamed, Christine Belletier, Meher Ben Abdelghani,a Jean-Frederic Blanc, Christophe Borg, Romain Coriat, Gael Deplanque,a Roger Faroux, Philippe Follana, Rosine Guimbaud, Farid el Hajbi, Pascal Hammel, Vincent Hautefeuille, David Malka, Jean-Philippe Metges, David Tougeron, Thomas Walter |

| Germany | Hana Algül, Thomas Ettrich, Ulrich Thorsten Hacker, Elke Hennes, Lutz Jacobasch, Stephan Kanzler, Ursula Pession, Anke Reinacher-Schick, Christian Scholz, Marianne Sinn, Alexander Stein, Christian Strassburg, Arndt Vogel |

| Israel | Menachem Ben-Shahar,a Ronen Brenner, Ron Epelbaum,a Ravit Geva, Alexander Gluzman, Talia Golan, Efraim Idelevich, Maya Kolin,a Valeriya Semenisty, Ayelet Shai, Salomon Stemmer, Nirit Yarom |

| Italy | Luigi Celio, Pierfranco Conte, Carlo Garufi, Luca Gianni, Francesco Leonardi, Evaristo Maiello, Mariacristina Di Marco, Michele Milella, Carmine Pinto,a Daniele Santini, Mario Scartozzi, Giampaolo Tortora,a Vanja Vaccaro, Enrico Vasile |

| Republic of Korea | Ji-Won Kim, Jin-Won Kim,a Do-Youn Oh, Joon Oh Park |

| The Netherlands | Hanneke Wilmink |

| Spain | Rafael Alvarez Gallego, Gema Duran Ogalla, Adelaida Garcia Velasco, Elena Garralda Cabanas,a Carlos Gomez Martin, Carmen Guillén Ponce, Berta Laquente Saez, Rafael Lopez, Teresa Macarulla, Andres Munoz Martin, Roberto Pazo, Carles Pericay Pijaume, Javier Rodriguez, Ricardo Yaya-Tur |

| UK | Arvind Arora, David Alan Anthoney, T.R. Jeffrey Evans, Mark Harrison, Daniel Hochhauser, Daniel Palmer, Debashis Sarker, Naureen Starling, Juan Valle, Lucy Wall |

| USA | Richy Agajanian, James Bearden, Tanios Bekaii-Saab,a Corey Carter, Deirdre Cohen, Alfred DiStefano, Tomislav Dragovich, Samuel Ejadi, James Ford, Stephen Grabelsky, Michael Hall, Howard Hochster,a Peter Hosein, Milind Javle, Hedy Kindler, Jill Lacy, Daniel Laheru, Stephen Leong, Maeve Lowery,a Robert Marsh, Anne Noonan, Paul Oberstein, Allyson Ocean, Eileen O'Reilly, David Ryan, Tara Seery, Somasundaram Subramaniam, David Van Echo,a Andrea Wang-Gillam, Colin Weekes,a Stephen Welch |

Former principal investigator.

Contributor Information

the POLO Investigators:

Lorraine Chantrill, David Goldstein, Warren Joubert, Nick Pavlakis, Annette Tognela, Eric Van Cutsem, Frank Van Fraeyenhove, Jean-Luc Van Laethem, Marc Peeters, Neesha Dhani, Petr Kavan, Frederic Lemay, Antoine Adenis, Pascal Artru, Nabil Baba-Hamed, Christine Belletier, Meher Ben Abdelghani, Jean-Frederic Blanc, Christophe Borg, Romain Coriat, Gael Deplanque, Roger Faroux, Philippe Follana, Rosine Guimbaud, Farid el Hajbi, Pascal Hammel, Vincent Hautefeuille, David Malka, Jean-Philippe Metges, David Tougeron, Thomas Walter, Hana Algül, Thomas Ettrich, Ulrich Thorsten Hacker, Elke Hennes, Lutz Jacobasch, Stephan Kanzler, Ursula Pession, Anke Reinacher-Schick, Christian Scholz, Marianne Sinn, Alexander Stein, Christian Strassburg, Arndt Vogel, Menachem Ben-Shahar, Ronen Brenner, Ron Epelbaum, Ravit Geva, Alexander Gluzman, Talia Golan, Efraim Idelevich, Maya Kolin, Valeriya Semenisty, Ayelet Shai, Salomon Stemmer, Nirit Yarom, Luigi Celio, Pierfranco Conte, Carlo Garufi, Luca Gianni, Francesco Leonardi, Evaristo Maiello, Mariacristina Di Marco, Michele Milella, Carmine Pinto, Daniele Santini, Mario Scartozzi, Giampaolo Tortora, Vanja Vaccaro, Enrico Vasile, Ji-Won Kim, Jin-Won Kim, Do-Youn Oh, Joon Oh Park, Hanneke Wilmink, Rafael Alvarez Gallego, Gema Duran Ogalla, Adelaida Garcia Velasco, Elena Garralda Cabanas, Carlos Gomez Martin, Carmen Guillén Ponce, Berta Laquente Saez, Rafael Lopez, Teresa Macarulla, Andres Munoz Martin, Roberto Pazo, Carles Pericay Pijaume, Javier Rodriguez, Ricardo Yaya-Tur, Arvind Arora, David Alan Anthoney, T R Jeffrey Evans, Mark Harrison, Daniel Hochhauser, Daniel Palmer, Debashis Sarker, Naureen Starling, Juan Valle, Lucy Wall, Richy Agajanian, James Bearden, Tanios Bekaii-Saab, Corey Carter, Deirdre Cohen, Alfred DiStefano, Tomislav Dragovich, Samuel Ejadi, James Ford, Stephen Grabelsky, Michael Hall, Howard Hochster, Peter Hosein, Milind Javle, Hedy Kindler, Jill Lacy, Daniel Laheru, Stephen Leong, Maeve Lowery, Robert Marsh, Anne Noonan, Paul Oberstein, Allyson Ocean, Eileen O'Reilly, David Ryan, Tara Seery, Somasundaram Subramaniam, David Van Echo, Andrea Wang-Gillam, Colin Weekes, and Stephen Welch

References

- 1.GLOBOCAN: estimated cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide in 2018. http://globocan.iarc.fr/Default.aspx (1 October 2019, date last accessed).

- 2. Noone AM, Howlader N, Krapcho M. et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2015. https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2015/sections.html (1 October 2019, date last accessed).

- 3. Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M. et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 2011; 364(19): 1817–1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP. et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med 2013; 369(18): 1691–1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ducreux M, Cuhna AS, Caramella C. et al. Cancer of the pancreas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2015; 26(Suppl 5): v56–v68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hameed M, Hameed H, Erdek M.. Pain management in pancreatic cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2010; 3(1): 43–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lahoud MJ, Kourie HR, Antoun J. et al. Road map for pain management in pancreatic cancer: a review. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2016; 8(8): 599–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carrato A, Falcone A, Ducreux M. et al. A systematic review of the burden of pancreatic cancer in Europe: real-world impact on survival, quality of life and costs. J Gastrointest Cancer 2015; 46(3): 201–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Akizuki N, Uchitomi Y, Inoguchi H. et al. Prevalence and predictive factors of depression and anxiety in patients with pancreatic cancer: a longitudinal study. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2016; 46(1): 71–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Anota A, Mouillet G, Trouilloud I. et al. Sequential FOLFIRI.3 + gemcitabine improves health-related quality of life deterioration-free survival of patients with metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a randomized phase II trial. PLoS One 2015; 10(5): e0125350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sohal DPS, Kennedy EB, Khorana A. et al. Metastatic pancreatic cancer: ASCO clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36(24): 2545–2556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Golan T, Hammel P, Reni M. et al. Maintenance olaparib for germline BRCA-mutated metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 2019; 381(4): 317–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gourgou-Bourgade S, Bascoul-Mollevi C, Desseigne F. et al. Impact of FOLFIRINOX compared with gemcitabine on quality of life in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer: results from the PRODIGE 4/ACCORD 11 randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31(1): 23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J. et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009; 45(2): 228–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Herman JM, Kitchen H, Degboe A. et al. Exploring the patient experience of locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer to inform patient-reported outcomes assessment. Qual Life Res 2019. July 4 [epub ahead of print], doi:10.1007/s11136-019-02233-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B. et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993; 85(5): 365–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J. et al. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol 1998; 16(1): 139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cocks K, King MT, Velikova G. et al. Evidence-based guidelines for determination of sample size and interpretation of the European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29(1): 89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Serrano PE, Herman JM, Griffith KA. et al. Quality of life in a prospective, multicenter phase 2 trial of neoadjuvant full-dose gemcitabine, oxaliplatin, and radiation in patients with resectable or borderline resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2014; 90(2): 270–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kleeff J, Korc M, Apte M. et al. Pancreatic cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016; 2: 16022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Scott NW, Fayers PM, Aaronson NK. et al. EORTC QLQ-C30. https://www.eortc.org/app/uploads/sites/2/2018/02/reference_values_manual2008.pdf (1 October 2019, date last accessed).

- 22. Banerjee S, Ledermann J, Matulonis U. et al. Abst 2759. Management of nausea and vomiting during treatment with the capsule (CAP) and tablet (TAB) formulations of the PARP inhibitor olaparib, European Cancer Congress. Vienna, Austria, 2015.

- 23. Dreno B, Ascierto PA, Atkinson V. et al. Health-related quality of life impact of cobimetinib in combination with vemurafenib in patients with advanced or metastatic BRAF(V600) mutation-positive melanoma. Br J Cancer 2018; 118(6): 777–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Harrington KJ, Ferris RL, Blumenschein G Jr. et al. Nivolumab versus standard, single-agent therapy of investigator's choice in recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (CheckMate 141): health-related quality-of-life results from a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017; 18(8): 1104–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Van Cutsem E, Golan T, Hammel P. et al. POLO: time to treatment discontinuation and subsequent therapies following maintenance olaparib for patients (pts) with a germline BRCA mutation and metastatic pancreatic cancer (mPC). European Society for Medical Oncology Congress, Barcelona, abstract #5029], 2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.