Abstract

We describe a new approach to fluorescence sensing based on a mixture of fluorophores, one of which is sensitive to the desired analyte. If a long-lifetime analyte-insensitive fluorophore is mixed with a short-lifetime analyte-sensitive fluorophore, the modulation of the emission at conveniently low frequencies becomes equal to the fractional fluorescence intensity of the sensing fluorophore. Under these conditions, the modulation can be used to determine the analyte concentration. This can be used with any fluorophore that changes intensity in response to analyte and does not require the sensing fluorophore to display a change in lifetime. The feasibility of modulation-based sensing was demonstrated using mixtures of 6-carboxyfluorescein and [Ru 2,2′-(bipyridyl)3]2+ as a pH sensor and of the calcium probe Fluo-3 and [Ru 2,2′-(bipyridyl)3]2+ as a calcium sensor.

Fluorescence is widely used in analytical and clinical chemistry.1–7 In the past several years there has been increasing interest in the use of time-resolved fluorescence as an analytical tool.8–11 The basic idea is to identify fluorophores or sensing schemes in which the decay time of the sample changes in response to the analyte and to use the decay time to determine the analyte concentration. Such lifetime-based sensing is most often performed using the phase-modulation method. The use of phase angles or decay times rather than intensities is advantageous because decay times are mostly independent of the signal level and can be measured in turbid media and even through skin.11,12

Most fluorophores used for sensing display decay times on the nanosecond time scale. It now appears possible to design low-cost instruments for sensors with nanosecond decay times. For instance, it is known that blue and UV light-emitting diodes (LEDs) can be modulated to over 100 MHz and used as the excitation source in phase modulation fluorometry.13–16 However, it may be useful to avoid the use of frequencies near 100 MHz, which are needed for nanosecond decay time measurements, and thus use the simpler electronics for lower frequencies. Also, a significant fraction of sensing fluorophores display changes in intensity without changes in lifetime.

In the present paper, we describe a general method to perform sensing at low light modulation frequencies near 1 MHz using sensing fluorophores with nanosecond lifetimes, without relying on a change in lifetime of the nanosecond fluorophore. The basic idea is to use a mixture of the nanosecond fluorophore with a fluorophore that displays a long lifetime near 1 μs. For such a mixture, the modulation of the emission at intermediate frequencies becomes equivalent to the fraction of the total emission due to the short lifetime nanosecond fluorophore. This occurs because the emission from the microsecond fluorophore is demodulated and that of the nanosecond fluorophore is near unity. This method allows sensing based on modulation from about 1 to 10 MHz. Additionally, the nanosecond sensing fluorophore does not need to display a change in lifetime. A simple change in intensity in response to the analyte is adequate for a low-frequency modulation sensor.

The feasibility of this sensing scheme was demonstrated to be practical in several systems. First, the method was validated using a simple mixture of nanosecond and microsensing fluorophores. We then devised assays for pH and for calcium. We note that this method is generic and can be applied to any analyte for which an intensity-based sensor is available.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The following reagent grade chemicals were obtained from commercial sources and used as received: Ru(bpy)3Cl2·6H2O (Aldrich; bpy) 2,2′-bipyridyl), 6-carboxyfluorescein (6-CF) (Eastman/Kodak), Fluo-3 pentapotassium salt (Molecular Probes), calcium calibration buffer kit 2 (C-3009, Molecular Probes), and TRIS (Sigma). Water was deionized with a Milli-Q purification system. Solutions ranging from pH 5.0 to 9.1 were prepared in TRIS buffer for the 6-CF studies. Experiments using the Ca2+ indicator Fluo-3 were performed solely in plastic media to prevent uptake of Ca2+ from glass surfaces. All solutions were prepared in plastic vials from the calcium calibration buffer. Luminescence measurements were performed in polystyrene plastic cuvettes. In one experiment, Ru(bpy)3Cl2 was in a poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) film on the outside of the cuvette. In all other studies, a small aliquot of aqueous Ru(bpy)3Cl2·6H2O was added to solutions containing the nanosecond fluorophore (6-carboxyfluorescein or Fluo-3) with analyte. We used these two different configurations to demonstrate the versatility of this approach to sensing. Typically, the steady-state emission intensity of Ru(bpy)3Cl2·6H2O contributed about 20–30% of the total sample intensity at the highest pH (6-carboxyfluorescein) or at the highest Ca2+ concentration (Fluo-3). All samples were optically dilute (<0.1 OD) at 488 nm.

Instrumentation.

UV-visible absorption spectra were measured on a Hewlett-Packard 8453 diode array spectrophotometer with (1 nm resolution. Uncorrected steady-state emission spectra were obtained on a SLM AB-2 fluorometer under magic angle polarization conditions. Time-resolved luminescence decays were measured in the frequency domain (ISS, Koala) using an air-cooled cw-Ar+ laser (Omnichrome, 543-AP) operating at 488.0 nm (80 mW). This laser was passed through a Pockels cell which provided modulated light from 300 kHz to 150 MHz. Two different PTS frequency synthesizers (PTS-500) were used to modulate the Pockels cell and detection system. The output of the PTS synthesizer driving the Pockels cell was amplified by an ENI 25-W linear rf amplifier (325 LA, 250 kHz-150 MHz) prior to Pockels cell input. The other PTS synthesizer output was directed into an ENI 3-W linear RF amplifier (403 LA, 150 kHz-300 MHz) for proper modulation of the detection system. The emission was observed as usual at 90° to the excitation through an appropriate combination of long-pass filters which eliminated scattered light at the excitation wavelength. We used this experimental configuration because it was available in this laboratory. In the actual use of modulation sensing, we expect the light source will be an intensity-modulated LED or some other solid-state light source.

The intensity decays were analyzed in terms of the multiexponential model,

| (1) |

where αi are the preexponential factors and τi the decay times. The fractional steady-state intensity associated with each decay time is given by

| (2) |

Generally, Σαi and the Σfi are constrained to be equal to unity. Rhodamine B in water with a lifetime of 1.68 ns was used as a lifetime reference in the frequency-domain experiments.17 Luminescence decays were analyzed by nonlinear least-squares procedures described previously.18,19 Global analysis of frequency-domain emission decay data was performed with programs developed at the Center for Fluorescence Spectroscopy. In the global analysis, the lifetimes were the global parameters and the amplitudes were fitted as nonglobal parameters. This means that the lifetimes were fitted parameters but were constrained to be the same values at all analyte concentrations. The amplitudes were also fitted parameters but were allowed to vary at each analyte concentration.

THEORY

Intensity decays were measured using the frequency-domain method.20,21 In this method one measures the phase (ϕω) and modulation (mω) of the emission for various values of the light modulation frequency (ω, in radians/s). For a mixture of fluorophores the phase and modulation can be calculated using

| (3) |

| (4) |

where fi is the fractional intensity, ϕi is the phase angle and mi is the modulation of each fluorophore. The terms Nω and Dω are typically referred to as the sine and cosine transforms of the intensity decays.18,19 If each fluorophore displays a single-exponential decay time τ then

| (5) |

| (6) |

For a multiexponential decay the phase and modulation at any given frequency ω are given by

| (7) |

| (8) |

In the present study, the samples display two widely different decay times, which we will refer to as the short (τS) and long (τL) decay times. In this case, the values of N and D are given by

| (9) |

| (10) |

where we have dropped the subscript ω referring to the light modulation frequency. The total fractional intensity is normalized fS + fL) 1.0. If the two lifetimes are very different, one can identify intermediate frequencies where the modulated emission of the short component is high and that of the long-lifetime component is low. Suppose the sample is examined at an intermediate modulation frequency such that the modulation of the short component is unity (mS) 1.0) and the modulation of the long component is near zero (mL) 0.0). In this case

| (11) |

| (12) |

Using eq 8, and recalling the sin2 θ + cos2 θ) 1.0, one obtains

| (13) |

This is a useful result which indicates that the modulation of the emission is the fractional intensity of the short-lifetime component. In the present report, the short-lifetime fluorophores were selected to display changes in intensity in response to the analyte. The long-lifetime fluorophore is [Ru(bpy)3]2+ and is not sensitive to changes in pH or calcium over the investigated concentration ranges.

RESULTS

Model Sensors with Varying Fluorescein Concentration.

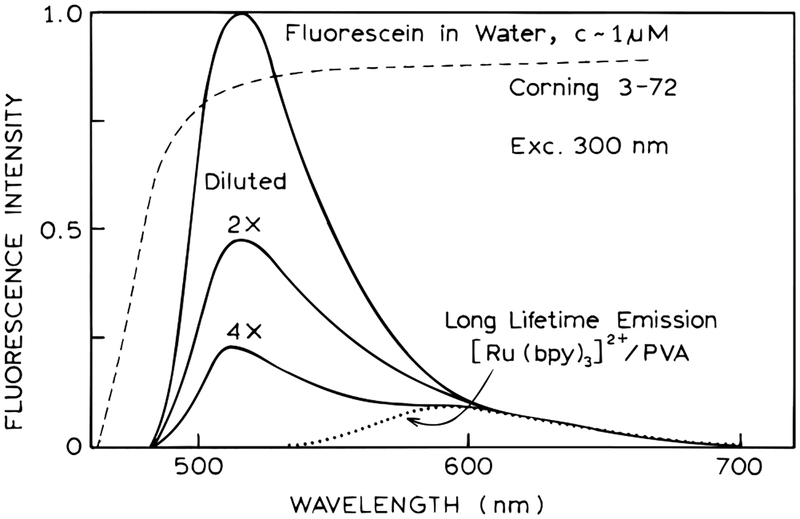

To test the principle of modulation sensing, we performed frequency-domain measurements for a sample that displayed emission from both [Ru(bpy)3]2+ and fluorescein. In this case, the two fluorophores were physically separated, which is a useful configuration if the sensing fluorophore can interact with the reference fluorophore. The long-lifetime fluorophore [Ru(bpy)3]2+ was dissolved in melted PVA which was painted on the outer surface of the cuvette (Chart 1, top). Aqueous solutions of fluorescein were placed within the cuvette. This model assay was excited at 488 nm with an argon ion laser. Emission spectra of this sample are shown in Figure 1. The fluorescein dominates the emission spectra with a maximum near 510 nm. The emission from [Ru(bpy)3]2+ occurs at longer wavelengths with an emission maximums near 590 nm.

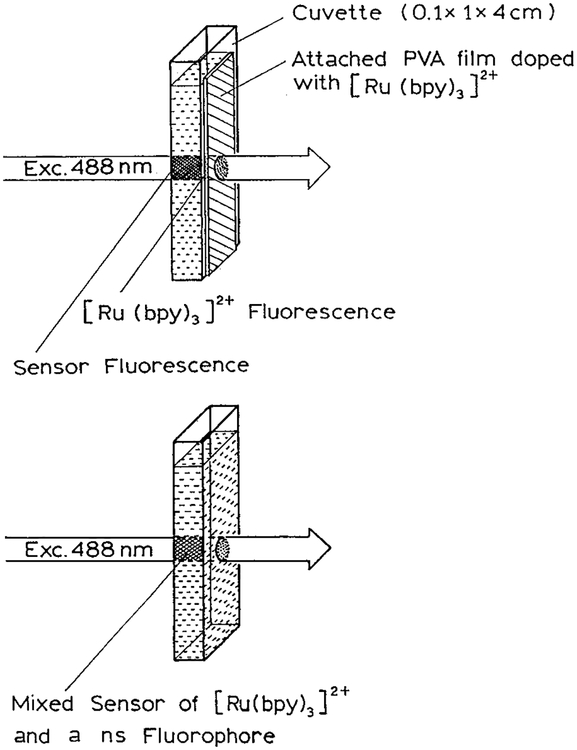

Chart 1.

Schematic of the Sensors with a Nanosecond Fluorophore and [Ru(bpy)3]2+

Figure 1.

Emission spectra of the model sensor containing fluorescein in the internal aqueous phase and [Ru(bpy)3]2+ in an external PVA film.

For FD measurements, the emission was observed through a Corning 3–72 filter, which transmitted the emission from both fluorescein and [Ru(bpy3)]2+ (Figure 1, - - -). The relative proportion of the two emissions were varied by dilution of the fluorescein within the cuvette (Figure 1). The concentration and emission intensity of [Ru(bpy)3]2+ remained the same as the fluorescein was diluted.

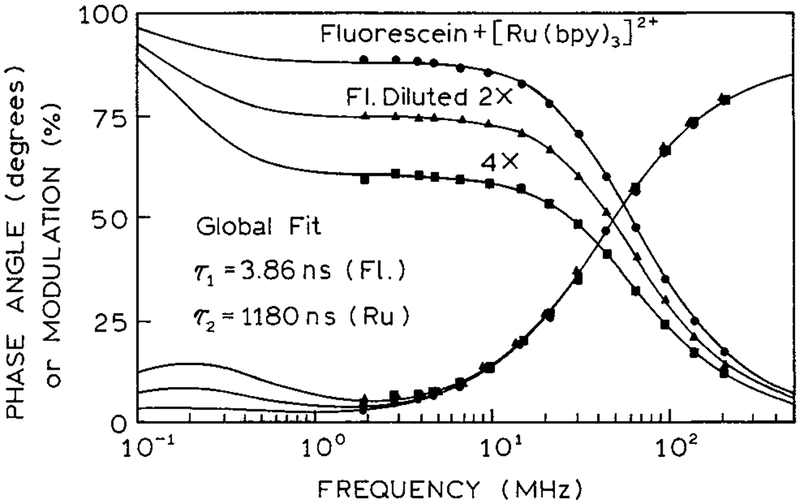

Figure 2 shows the frequency-domain intensity decays of this model assay. The emission is already demodulated below 1.0 for the lowest measurement frequency near 1.8 MHz. This effect is due to the long decay time of [Ru(bpy)3]2+ in PVA. In separate measurements, the decay time of [Ru(bpy)3]2+ in PVA was found to be 1180 ns. The modulation is nearly constant from 2 to 8 MHz. This occurs because the modulation of [Ru(bpy)3]2+ is near zero and that of fluorescein with a lifetime of 2.85 ns is near 1.0. In this low-frequency range, the modulation is expected to represent the fractional steady-state intensity of the short-lifetime emission (eq 13). Comparison of Figures 1 and 2 shows that the modulation values at intermediate frequencies are approximately equal to the intensity of fluorescein relative to that of [Ru(bpy)3]2+.

Figure 2.

Frequency-domain intensity decay of the fluorescein-[Ru(bpy)3]2+ model sensor.

Low-Frequency Modulation pH Assay.

We use the concept described above to create a pH assay based on the modulation at the intermediate frequencies. As a pH-sensitive fluorophore we selected 6-CF. Fluorescein and its derivatives have been widely used for pH sensing.22–24 Fluorescein and its derivatives display a pH-dependent dissociation of the carboxyl group. The ionized form, which exists at pH values above 7.5, is highly fluorescent, and the protonated low-pH form is essentially nonfluorescent. For this reason, fluorescein is not known to display a change in lifetime when this dissociation reaction occurs.

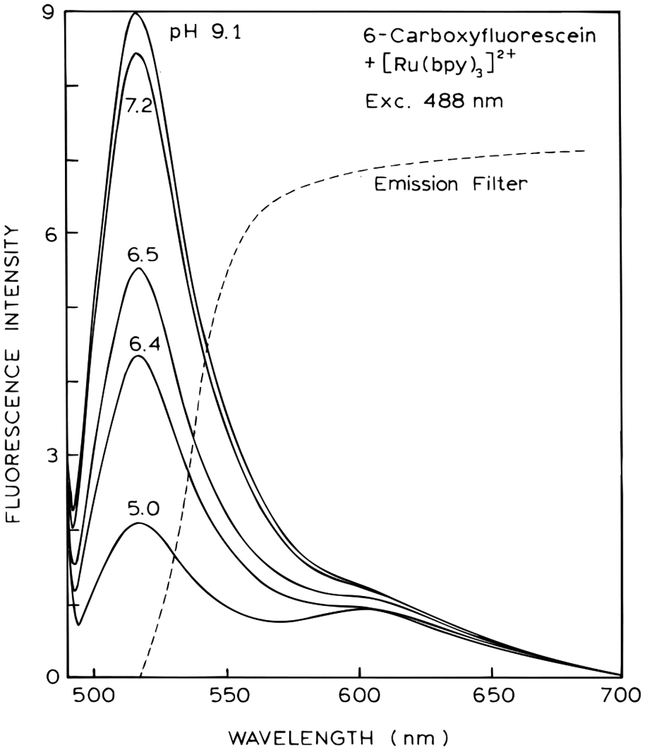

For the modulation pH assay, 6-CF and [Ru(bpy)3]2+ were both dissolved in the aqueous phase (Chart 1, bottom). We did not use the external PVA film. Emission spectra of this mixture shows that the 6-CF emission is strongly affected by pH, while the intensity of the long-lifetime [Ru(bpy)3]2+ is essentially the same at all pH values (Figure 3). The emission filter was selected to transmit all the [Ru(bpy)3]2+ emission and part of the 6-CF emission. In this way, one can modify the fractional intensity from each fluorophore without changing the actual concentrations.

Figure 3.

Emission spectra of a pH sensor based on a mixture of 6-CF and [Ru(bpy)3]2+.

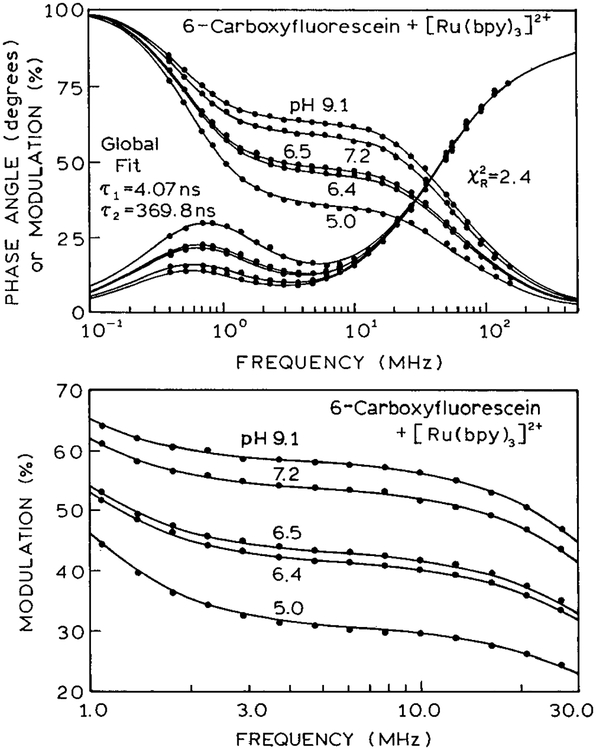

Frequency-domain intensity decay data for the mixture of 6-CF and [Ru(bpy)3]2+ are shown in Figure 4, top panel. As expected based on the lifetimes of 6-CF (4.07 ns) and [Ru(bpy)3]2+ (370ns), there is a region of constant modulation from 2 to 10 MHz. In this region, the modulation of the emission increases due to the higher intensity of 6-CF at high pH. The frequency data were analyzed using the multiexponential model (eq 1). At all pH values, the frequency responses could be fit to two decay times of 4.0 and 370 ns, as can be seen from the global analysis in Table 1. As the pH value increases, the fractional steady-state intensity of the short component (fi) also increases. For mixtures with such different lifetimes it is preferable to use the fi values, rather than the preexponential factors. The values of α1 are over 0.98 at all pH values.

Figure 4.

(Top) Frequency responses of the pH assay. (Bottom) Low-frequency modulation of the pH sensor.

Table 1.

Global Double-Exponential Analysis of the Intensity Decays of pH Sensora

| pH | α1 | α2 | f1 | f2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9.1 | 0.994 | 0.006 | 0.627 | 0.373 | 2.4 |

| 7.2 | 0.992 | 0.008 | 0.583 | 0.417 | |

| 6.5 | 0.988 | 0.012 | 0.474 | 0.526 | |

| 6.4 | 0.987 | 0.013 | 0.459 | 0.541 | |

| 5.0 | 0.980 | 0.020 | 0.347 | 0.653 |

At all pH’s, T1 = 4.07 ns and T2 = 369.8 ns.

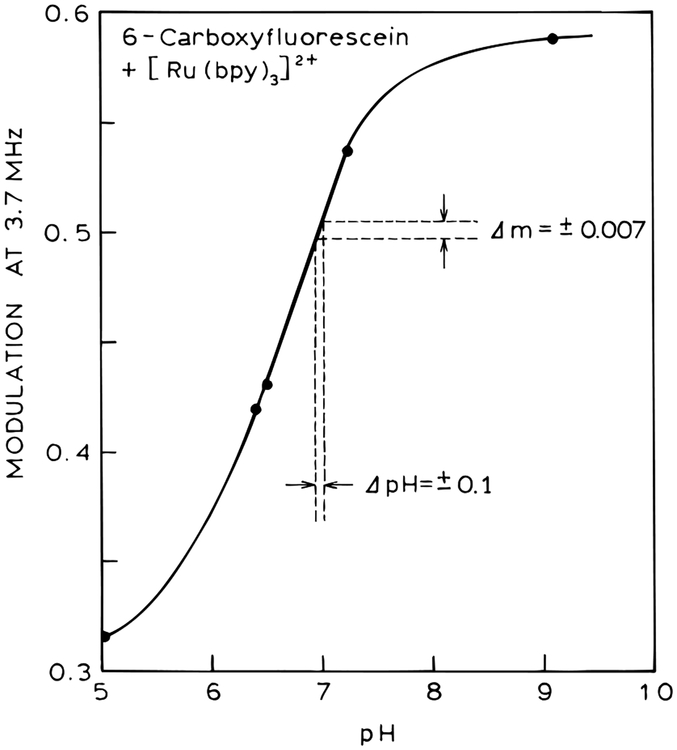

For clinical applications, the pH values are typically accurate to (±0.02 or better.25–28 The present sensor was found to be sensitive to changes in pH of (±0.1, as can be seen in the modulation data on an expanded scale (Figure 4, lower panel). For instance, pH values of 6.4 and 6.5 are easily distinguishable. Such data can be used to prepare a calibration curve for pH based on the modulation at 3.7 MHz (Figure 5). Modulation measurements are readily accurate to (±0.007, which results in a pH accuracy of (±0.1 (Figure 5). While the present level of accuracy does not meet the clinical specifications, we have not yet attempted to optimize the assay on the basis of the relative intensities of the two species and the overall change in intensity of the pH-sensitive fluorophore. Also, it should be possible to include measurements of the phase angle and modulation at more than one frequency to improve the pH accuracy.

Figure 5.

Calculation curve of the pH sensor.

A Modulation Assay for Calcium.

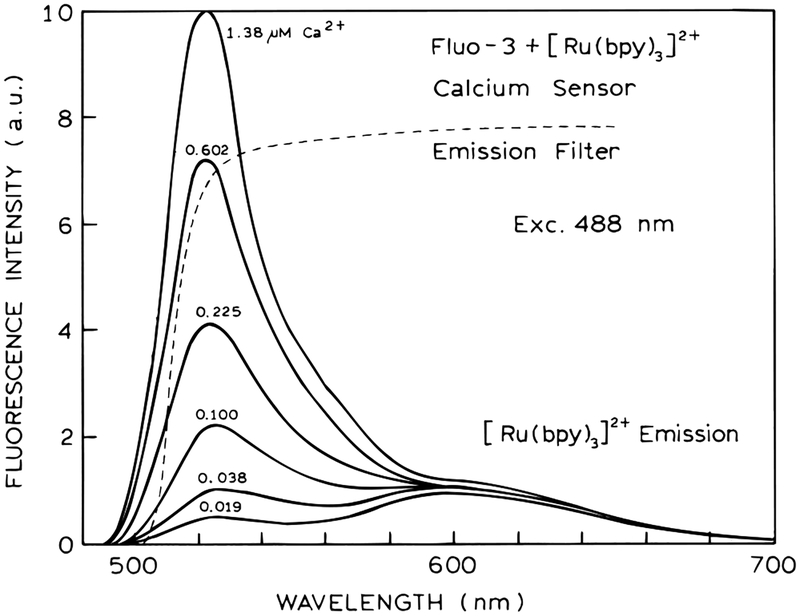

Calcium is known to be an intracellular messenger. Measurements of calcium concentrations have been the subject of numerous publications.29,30 Calcium can be measured using intensity-ratiometric probes31–34 or using lifetime-based sensing.35–39 However, some calcium probes do not display spectral shifts upon binding calcium, and some probes do not display changes in lifetime. One such calcium probe is Fluo-3, which is highly fluorescent in the presence of bound calcium but essentially nonfluorescent in the absence of calcium. Because the calcium-free probe does not fluoresce, the emission is due to only the calcium-bound form. For this reason, only the calcium-bound form of Fluo-3 contributes to the lifetime, and thus Fluo-3 displays the same lifetime at all calcium concentrations.

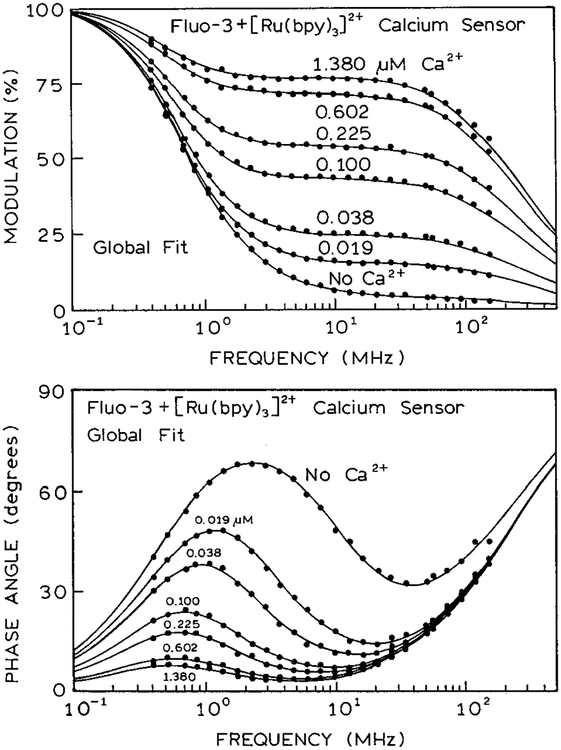

While Fluo-3 cannot be used as wavelength-ratiometric or lifetime sensor for calcium, it can be used in our method of modulation sensing. This is shown in Figure 6. In this assay both Fluo-3 and [Ru(bpy)3]2+ were contained within the cuvette. The emission of Fluo-3 at 510 nm increases dramatically in the presence of Ca2+. The emission intensity of [Ru(bpy)3]2+ is not sensitive to calcium and is the same at all calcium concentrations. The frequency-dependent modulation of the Fluo-3 [Ru-(bpy)3]2+ mixture is shown in Figure 7. As the calcium concentration increases so does the modulation from 2 to 30 MHz. We also examined the frequency-dependent phase angles (Figure 7). The phase angles show a maximum near 1 MHz. The largest values near 1 MHz are seen in the absence of calcium, where the emission is dominated by the long-lifetime Ru complex. As the calcium concentration increases the phase angles decrease to smaller values as the emission becomes dominated by the shorter lived emission from Fluo-3.

Figure 6.

Emission spectra of a modulated calcium sensor based on Fluo-3 and [Ru(bpy)3]2+.

Figure 7.

(Top) Modulation frequency response of the calcium assay. (Bottom) Phase angle frequency response of the calcium assay.

The modulation and phase angle frequency responses (Figure 7) were analyzed in terms of the multiexponential model (eq 1). Two decay times were needed to account for the emission from Fluo-3, 0.72 and 1.89 ns (Table 2). The data at all calcium concentrations could be globally fit to the same three decay times, with the fractional intensities dependent on the calcium concentration.

Table 2.

Global Intensity Decay Analysis of the Fluo-3 [Ru(bpy)3]2+ Calcium Sensora Intensity Decay

| Ca2+ (μM) | Ti = 0.72 ns | T2 = 1.89 ns | T3 = 359.8 ns | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| αi | fi | α2 | f2 | α3 | f3 | ||

| Ca2+ satd | 0.733 | 0.415 | 0.266 | 0.397 | 0.001 | 0.188 | 2.2 |

| 1.38 | 0.857 | 0.531 | 0.143 | 0.233 | 0.001 | 0.235 | |

| 0.602 | 0.859 | 0.498 | 0.140 | 0.215 | 0.001 | 0.287 | |

| 0.225 | 0.875 | 0.392 | 0.123 | 0.145 | 0.002 | 0.463 | |

| 0.100 | 0.860 | 0.302 | 0.137 | 0.126 | 0.003 | 0.572 | |

| 0.038 | 0.861 | 0.171 | 0.132 | 0.069 | 0.007 | 0.760 | |

| 0.019 | 0.879 | 0.113 | 0.108 | 0.036 | 0.013 | 0.851 | |

| 0 | 0.692 | 0.020 | 0.240 | 0.018 | 0.068 | 0.962 | |

In a calcium saturated solution, without [Ru(bpy)3]2+, Fluo-3 displayed a double-exponential intensity decay with T1 = 0.78 ns, T2 = 1.92 ns, α1 = 0.768, α3 = 0.232, f1 = 0.575, and f2 = 0.425, The value for the single-decay time fit for Fluo-3 alone was 18.2. In water, [Ru(bpy)3]2+ displayed a single-exponential decay of 370 ns.

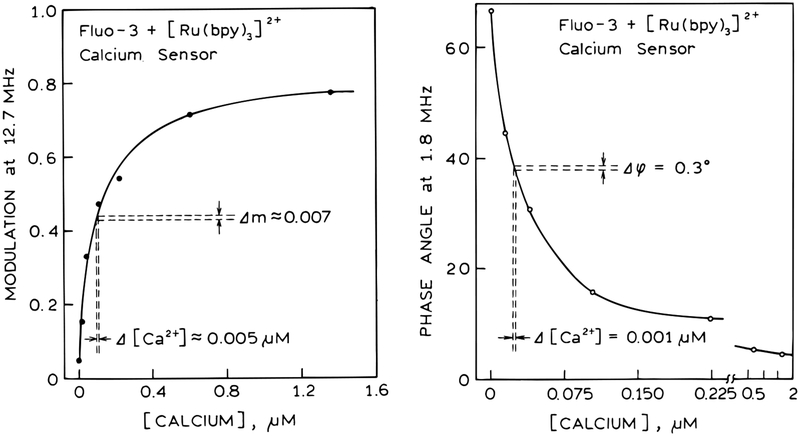

The data in Figure 7 were used to prepare calibration curves for calcium (Figure 8). The modulation values at 12.7 MHz show an apparent calcium dissociation constant (KD) for Fluo-3 near 100 nM, which is lower than but comparable to the known dissociation constant near 400 nM.40–42 Precise agreement between the thermodynamic KD value and the apparent value from time-resolved data is not expected. Depending on the nature of the time-resolved measurements, the apparent KD values can be larger or smaller than the true KD value.8

Figure 8.

Phase and modulation calibration curves of the calcium sensor.

The low-frequency phase data were also used to prepare a calcium calibration curve (Figure 8). In this case, the phase angles are sensitive to lower concentrations of calcium, with an apparent KD near 40 nM. This suggests the combined use of both the phase and modulation data to allow measurement of calcium over an extended range of concentrations or to provide increased accuracy over a critical range of concentrations.

DISCUSSION

What are the advantages of low-frequency modulation sensing? It is now accepted that lifetime-based sensing can be preferable to intensity-based sensing because the lifetimes are mostly independent of changes in probe concentration and/or signal level. Modulation sensing shows many of these advantages. The modulation will be independent of the total signal level. Hence, modulation sensing can be accurate if the overall signal level changes due to flexing in fiber optics or changes in the positioning of the sample. However, it is necessary that the relative proportions of the short-and long-lifetime fluorophores remain the same. If the relative intensities change, in a manner independent of analyte concentration, then the modulation calibration curve will also change. Hence, the calibration curves for a modulation sensor will change if the sensing and reference fluorophores photobleach at different rates.

An advantage of low-frequency modulation sensing is the simple instrumentation. It is now well-known that light-emitting diodes can be easily modulated at frequencies up to 100 MHz.13–16 Also, LEDs are available within a range of output wavelengths, even down to the near-UV at 390 nm.13 Additionally, there has been considerable progress in the design and synthesis of long-lifetime metal-ligand complexes. Ruthenium, osmium, and rhenium complexes have been reported.43–45 The rhenium complexes are particularly useful in that they display high quantum yields and lifetimes up to 3 μs in oxygenated solution.46,47

And finally, the most important advantage of modulation sensing may be the expanded range of analytes. Any sensing fluorophore that changes intensity can be used in this model. A change in probe lifetime is not needed. Hence, modulation sensing can be used with probes such as SBFI and PBFI, which are poor wavelength-ratiometric probes for sodium and potassium.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Dedicated to Professor Ludwig Brand on the occasion of his 65th birthday. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health National Center for Research Resources RR-08119. F.N.C. was supported by a NIH postdoctoral fellowship.

References

- (1).Schulman SG, Ed. Molecular Luminescence Spectroscopy, Methods and Applications: Part 3; John Wiley & Sons: New York, 1993; p 467. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Spichiger-Keller UE Chemical Sensors and Biosensors for Medical and Biological Applications; Wiley-VCH: New York, 1998; p 413. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Wolfbeis OS, Ed. Fiber Optic Chemical Sensors and Biosensors; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 1991; Vol. I, p 413. [Google Scholar]

- (4).Wolfbeis OS, Ed. Fiber Optic Chemical Sensors and Biosensors; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 1991; Vol. II, p 358. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Kunz RE, Ed. Part I: Plenary and Parallel Sessions; Part II: Poster Sessions, Proc. of 3rd European Conference on Optical Chemical Sensors and Biosensors, Europt(R)odeIII. Elsevier Publishers: New York, 1996. (Sens. Actuators B 1996, 38, 1–188). [Google Scholar]

- (6).Lakowicz JR, Ed. Topics in Fluorescence Spectroscopy, Volume 4: Probe Design and Chemical Sensing; Plenum Press: New York, 1994; p 501. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Thompson RB, Ed. SPIE Proc. 1997, 2980, 582. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Szmacinski H; Lakowicz JR Lifetime-based sensing In Topics in Fluorescence Spectroscopy: Volume 4: Probe Design and Chemical Sensing; Lakowicz JR, Ed.; Plenum Press: New York, 1994; pp 295–334. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Lippitsch ME; Draxler S; Kieslinger D Sens. Actuators B 1997, 38–39, 96–102. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Lippitsch ME; Pusterhofer J; Leiner MJP; Wolfbeis OS Anal. Chim. Acta 1988, 205, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Bambot SB; Rao G; Romauld M; Carter GM; Sipior J; Terpetschnig E; Lakowicz JR Biosens. Bioelectron 1995, 10, 643–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Szmacinski H; Lakowicz JR Sens. Actuators 1996, 30, 207–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Sipior J; Carter GM; Lakowicz JR; Rao G Rev. Sci. Instrum 1997, 68, 2666–2670. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Sipior J; Carter GM; Lakowicz JR; Rao G Rev. Sci. Instrum 1996, 67, 3795–3798. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Lakowicz JR; Koen PA; Szmacinski H; Gryczynski I; Kuśba JJ Fluoresc. 1994, 4, 115–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Randers-Eichhorn L; Albano CR; Sipior J; Bentley WE; Rao G Biotechnol. Bioeng 1997, 55, 921–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Gryczynski I; Kuśba J; Lakowicz JR J. Fluoresc 1997, 7, 167–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Lakowicz JR; Gratton E; Laczko G; Cherek H; Limkeman M Biophys. J 1984, 46, 463–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Gratton E; Lakowicz JR; Maliwal B; Cherek H; Laczko G; Limkeman M Biophys. J 1984, 46, 479–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Lakowicz JR; Gryczynski I Frequency domain fluorescence spectroscopy In Topics in Fluorescence Spectroscopy, Vol. 1: Techniques; Lakowicz JR, Ed.; Plenum Press: New York, 1991; pp 293–331. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Lakowicz JR Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy, 2nd ed.; Plenum Press: New York, in press. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Thomas JA; Buchsbaum RN; Zimniak A; Racker E Biochemistry 1979, 18, 2210–2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Babcock DF J. Biol. Chem 1983, 258, 6380–6389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Klonis N; Clayton AHA; Voss EW; Sawyer WH Photochem. Photobiol 1998, 67, 500–510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Mahutte CK; Holody M; Maxwell TP; Chen PA; Sasse SA Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 1994, 149, 852–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Mahutte CK; Sasse SA; Chen PA; Holody M Am. J. Respir. Med. Care Med 1994, 150, 865–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Shapiro BA; Mahutte CK; Cane RD; Gilmour IJ Crit. Care Med 1993, 21, 487–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Mahutte CK Intensive Care Med. 1994, 20, 85–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Nuccitelli R, Ed. A Practical Guide to the Study of Calcium in Living Cells; Methods in Cell Biology 40; Academic Press: New York, 1994; p 368. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Grynkiewicz G; Poenie M; Tsien RY J. Biol. Chem 1985, 260, 3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Tsien RY; Rink TJ; Poenie M Cell Calcium 1985, 6, 145–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Kao JPY Practical aspects of measuring [Ca2+] with fluorescent indicators In Methods in Cell Biology; Nuccitelli R, Ed.; Academic Press: New York, 1994; Viol. 40, pp 155–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Tsien RY Fluorescent indicators of ion concentrations In Methods in Cell Biology; Lansing Taylor D, Wang Y-L, Eds.; Academic Press: New York, 1989; Vol. 30, pp 127–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Akkaya EU; Lakowicz JR Anal. Biochem 1993, 213, 285–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Lakowicz JR; Szmacinski H; Johnson ML J. Fluoresc 1992, 2, 47–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Hirschfield KM; Toptygin D; Packard BS; Brand L Anal. Biochem 1993, 209, 209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Miyoshi N; Hara K; Kimura S; Nakanishi K; Fukuda M Photochem. Photobiol 1991, 53, 415–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Lakowicz JR; Szmacinski H; Nowaczyk K; Johnson ML Cell Calcium 1992, 13, 131–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Lakowicz JR; Szmacinski H Sens. Actuators B 1992, 11, 133–143. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Minta A; Kao JPY; Tsien RY J. Biol. Chem 1989, 264, 8171–8178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Kao JPY; Harootunian AT; Tsien RY J. Biol. Chem 1989, 264, 8179–8184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Harkins AB; Kurebayashi N; Baylor SM Biophys. J 1993, 65, 865–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Lakowicz JR; Terpetschnig E; Szmacinski H; Malak H SPIE Proc. 1995, 2388, 32–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Terpetschnig E; Szmacinski H; Lakowicz JR Long-lifetime metal-ligand complexes as probes in biophysics and clinical chemistry In Methods in Enzymology; Brand L, Johnson ML, Eds.; Academic Press: New York, 1997; Vol. 278, pp 295–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Castellano FN; Dattelbaum JD; Lakowicz JR Anal. Biochem 1998, 255, 165–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Guo X-Q; Castellano FN; Li L; Lakowicz JR Anal. Chem 1998, 70, 632–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Guo X-G; Castellano FN; Li L; Szmacinski H; Lakowicz JR; Sipior J Anal. Biochem 1997, 254, 179–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]