Abstract

Ischemic vascular remodeling occurs in response to stenosis or arterial occlusion leading to a change in blood flow and tissue perfusion. Altered blood flow elicits a cascade of molecular and cellular physiological responses leading to vascular remodeling of the macro- and microcirculation. Although cellular mechanisms of vascular remodeling such as arteriogenesis and angiogenesis have been studied, therapeutic approaches in these areas have had limited success due to the complexity and heterogeneous constellation of molecular signaling events regulating these processes. Understanding central molecular players of vascular remodeling should lead to a deeper understanding of this response and aid in the development of novel therapeutic strategies. Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and nitric oxide (NO) are gaseous signaling molecules that are critically involved in regulating fundamental biochemical and molecular responses necessary for vascular growth and remodeling. This review examines how NO and H2S regulate pathophysiological mechanisms of angiogenesis and arteriogenesis, along with important chemical and experimental considerations revealed thus far. The importance of NO and H2S bioavailability, their synthesis enzymes and cofactors, and genetic variations associated with cardiovascular risk factors suggest that they serve as pivotal regulators of vascular remodeling responses.

Introduction

Everywhere we look, complex magic of nature blazes before our eyes.

— Vincent van Gogh

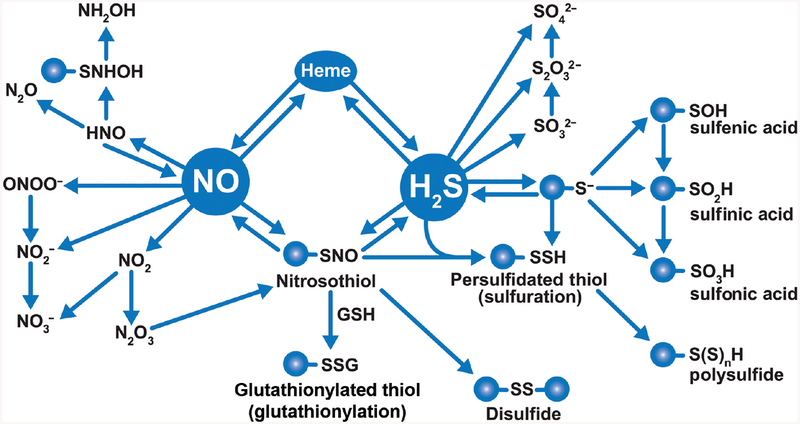

While there are visible complexities to which van Gogh refers, far more complexity exists in the form of cellular signaling and small molecules that are involved in regulating various biological functions. The quote “The art of simplicity is a puzzle of complexity” may hold true with the gaseous signaling molecules otherwise known as “gasotransmitters” – nitric oxide (NO) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S). Nitrogen and sulfur are among the fundamental elements that play an essential part of life on Earth (261). Sulfides and different nitrogen oxides have been studied extensively in environmental, chemical, and various biological processes including their role in the origin of life itself. For quite some time, NO and H2S were simply considered toxic gases and environmental hazards, yet they have emerged as important regulatory signaling molecules for numerous physiological and pathological functions including vasorelaxation, anti-inflammation, antithrombotic effects, central nervous system function, and protection against ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury (166, 167). In this review, we discuss the roles of NO and H2S, and their respective metabolites in relation to vascular remodeling along with molecular signaling mechanisms. Importantly, we also discuss the synthesis, catabolism, chemical interactions, and detection methods associated with these gaseous signaling mediators.

Historical Perspective of NO and H2S—Overview

Nitric oxide (NO)

Joseph Priestley detailed many of his discoveries in his Volume 1: Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air, where the mention of a colorless gas “nitrous air” (nitric oxide) was first observed. However, appreciation of the biological functions of NO was not fully realized until 1980 to 1990. Much before the discovery of NO, in 1847 an Italian chemist Ascanio Sobrero discovered glyceryl trinitrate, popularly called nitroglycerin for its dangerous properties that can cause severe headaches even with minimal exposure. In 1867, Swedish chemist and engineer Alfred Nobel patented his famous dynamite when he stabilized nitroglycerin with kieselguhr (207). Coincidentally, workers at the nitroglycerin factory with angina pectoris had their condition improve when exposed to this compound. However, it was not until 1879 when William Murrell, a British physician, identified the therapeutic effects of nitroglycerin for angina pectoris. Almost a century later, in 1977, Ferid Murad identified the beneficial effects of nitroglycerin to derive NO release in vascular smooth muscle. Seminal works also during the 1980s from Robert F. Furchgott and Louis J. Ignarro identified endothelium-derived relaxing factor (EDRF) as NO with physiological implications in regulating vascular tone (97, 115, 141, 256). Work from Murad further revealed that the nitrovasodilator function is mediated through sGC/cGMP pathway (229). Collectively these works established NO as a key-signaling molecule regulating vascular tone, which was recognized with the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine in 1998. Currently, NO has been associated with many pathophysiological responses such as inflammation, cancer, tissue growth and development, and in the nervous and cardiovascular systems.

NO is enzymatically produced by three nitric oxide synthases (NOSs)—neuronal NOS (nNOS), inducible NOS (iNOS), and endothelial NOS (eNOS) that all use L-arginine as a substrate in conjunction with other cofactors including tetrahydrobiopterin, calcium, oxygen, NADPH, and others. NOS also contributes to the production of other NO metabolites such as nitrite (NO2−) and nitrate (NO3−), which are formed from by oxidation of NO (217). Nitrate and nitrite were originally considered to be inactive metabolic by-products of NO. This notion has changed following a series of publications from many researchers demonstrating that these metabolites have therapeutic potential through their conversion to NO or on their own via other pathways in pathophysiological states (198). The role of NO metabolites such as nitrite is especially emphasized under oxygen-deprived conditions such as hypoxia/ischemia where the NOS isoforms may be dysfunctional. There is increasing literature also identifying nitrate/nitrite as a biomarker and for therapeutic potential against ischemic/reperfusion injury including cardiovascular disease, which has been known since ancient times (157).

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S)

Hydrogen sulfide, a recent addition to the gasotransmitter family, was once known only for its serious health hazards. “Environmental toxin,” “sewer gas,” and “rotten egg gas” have been synonymous with H2S. However, only in the last two decades H2S has been identified for its role in many biological functions. A historical account of H2S has been reviewed recently (350). Identification of H2S as a toxic gas dates back to the observations of Italian physician Bernardino Ramazzini from sewage cleaners during the 1700s (350). In 1863, H2S was identified again for its negative qualities in the formation of sulfhemoglobin, which is responsible for cyanosis even at low levels. Earlier works between 1877 and 1884 identified H2S as a “bacterial product” with its roles in intestinal and periodontal diseases, and more recently in regulating bacterial resistance to antibiotics. It was not until the 1940’s that H2S was identified as an inhibitor of cytochrome c oxidase (169). Only in the last two decades, have positive effects of H2S as a regulator of physiological functions, including the cardiovascular and nervous system, been identified.

Like NO, H2S also regulates key physiological processes including vascular reactivity, inflammation, cardioprotection, and protection against tissue I/R injury (165, 400). Although there is considerable research in these areas, much uncertainty remains with respect to the signaling mechanisms that are involved in H2S chemical biology. For example, how can H2S be both pro- and anti-inflammatory, and both toxic and also cytoprotective? Clearly, concentration dependent responses are likely involved through activation of different signaling pathways, which requires further study to better appreciate its role in health and disease.

Vascular Growth and Remodeling Concepts

The vascular system plays a critical role in both functional and structural changes responsible for organ physiology. Blood vessels are the structures that supply oxygen and nutrients to various tissues that aid in their growth. Vascular remodeling is a dynamic process involving alterations in structural geometry of blood vessels in response to external stimuli, which can be mediated by hemodynamics, pressure changes, or injury. These changes initiated as an adaptive process can turn mal-adaptive long-term and lead to impaired vascular functions. Early development of the embryo occurs through simple diffusion of nutrients and growth factors. At this stage, there is little biological need for a capillary network. However, the circulatory system including the heart, blood, and blood vessels is the first physiological system to be functional, as organism development progresses in complexity. Early cardiovascular system development is essential for distribution of O2 to various developing parts of the embryo, as O2 can no longer simply diffuse. Thus, rapid formation of a complex vascular network occurs with the onset of events in vascular growth called “vascularization.” Vasculogenesis is a process of initiation of endothelial precursor cells eventually forming primitive tubule-like structures expanding to form a vascular network called “angiogenesis.” This process includes the formation of new blood vessels from existing ones, otherwise known as “sprouting,” and division of existing blood vessels termed ‘intussusception’ eventually branch into arterioles and capillaries.

Types of vascular growth

A robust and functional vascular network is fundamental for development, growth, and tissue maintenance. Vascular growth processes continue after birth and are necessary throughout the life of an organism, thus maintaining physiologic homeostasis including organ growth, wound healing, and the menstrual changes of the uterine mucosa (96). Based on the mechanism, occurrence, and result, vascular growth can be distinguished principally as three types (130). Firstly, during vasculogenesis differentiation of precursor cells or angioblasts into endothelial cells occurs eventually leading to the de novo formation of a primitive vascular network. Secondly, in angiogenesis, new capillaries form from pre-existing capillary vessels (288). Thirdly, in arteriogenesis, formerly regarded as a variant of angiogenesis, mature arteries undergo remodeling response affecting luminal diameter and wall thickness, thus distinguishing it from other mechanisms of vascular growth (36, 301). Stimulation of arteriogenesis can occur in response to differential blood flow shear rate via an occlusion in a main conduit artery that disrupts this balance and initiates blood flow from a connecting collateral artery to a downstream reentry zone, thereby stimulating arteriogenesis. The change in hemodynamics experienced by the collateral vessel stimulates outward vascular remodeling to increase lumen diameter and wall thickness (Fig. 1A).

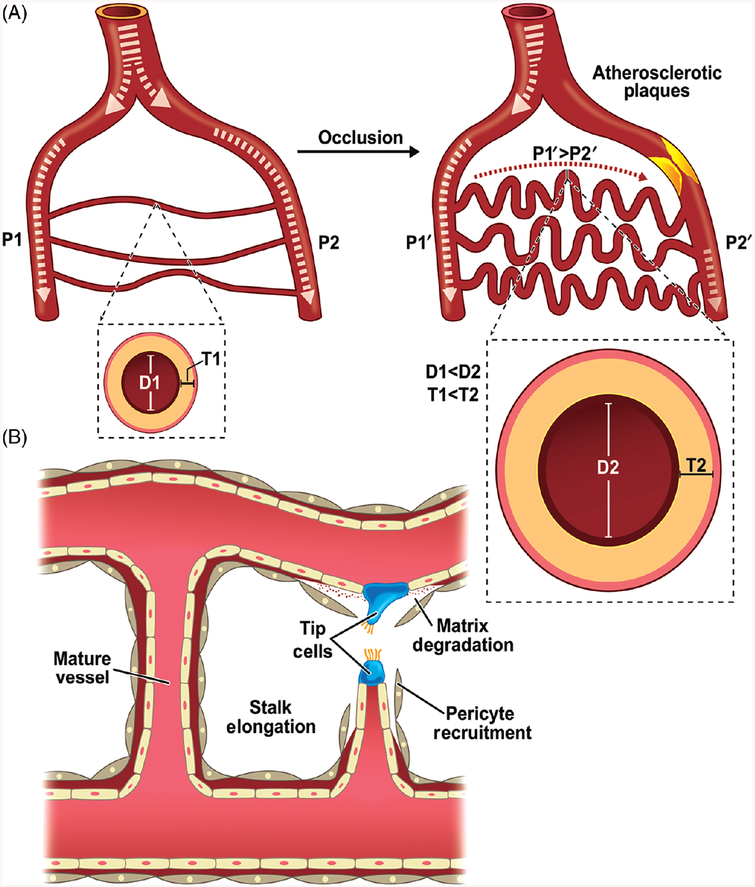

Figure 1.

Vascular remodeling due to arteriogenesis or angiogenesis: remodeling of macro- and microvasculature occurs through arteriogenesis and angiogenesis, respectively. (A) In the absence of occlusion, blood flow across two arterial branches is minimal resulting in equivalent pressure (P1 = P2). Upon arterial occlusion of one branch, fluid shear stress due to altered blood flow causes differential pressure (P1 > P2), resulting in increased luminal diameter (D1 < D2) and vascular wall thickness (T1 < T2). (B) Angiogenesis is a multistep process involving endothelial cell activation and extracellular matrix degradation followed by tip cell sprouting and progressive vessel stalk elongation. Further structural support and vessel stabilization occur by pericyte recruitment.

Angiogenesis: Physiology

Angiogenesis is a fundamental process by which new blood vessels are formed from pre-existing capillaries that includes tip cell sprouting, stalk elongation and vessel maturation (87) (Fig. 1B). It also plays a central role in various physiological processes including embryonic development, wound repair and the menstrual cycle. Further upon angiogenic stimuli, proteolytic enzymes are produced leading to degradation of extracellular matrix thereby allowing endothelial cells (EC’s) to migrate. A fine balance of proteolytic enzymes and their inhibitors exist to prevent pathological angiogenesis. In addition to migration of EC’s, degradation of the extracellular matrix also leads to release of growth factors including VEGF, FGF, and IGF-1 which are otherwise sequestered within the matrix (59).

Angiogenesis is characterized by step-wise progression including: (i) increased endothelial solute permeability, (ii) proliferation and migration of endothelial cells (typically involving pericyte and matrix changes), (iii) assembly of ECs into sprouting vessels, (iv) differentiation of ECs to form new vessels, and (v) maturation of the new vasculature. The first step of this process is altered permeability of the existing vessel. A change in solute permeability may occur in response to several mediators with vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) binding to its receptor in the ECs leading to increased vascular permeability. As a result, movement of endothelial junction proteins occurs away from cell-cell junctions including, platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM-1), vascular endothelial cadherin (VE-cadherin), and occludin (81, 98, 158). Degradation of extracellular matrix facilitates cell migration beneath the basement membrane, involving a prominent role of the actin cytoskeleton (344).

Several potential regulators including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and angiopoietin 1 (Ang-1) regulate EC migration and proliferation. Numerous reports suggest a pronounced angiogenic effect of VEGF and the loss of a single VEGF allele results in early lethality of mouse embryos (39, 84, 184, 240). Although compelling evidence suggests the importance of VEGF throughout the angiogenesis process, homologs of VEGF can provide some functional redundancy. For instance, VEGF-A is responsible for endothelial migration, MMP activity, and permeability. Whereas, PDGF is restricted to embryonic angiogenesis, but is involved during pathological angiogenesis during ischemia, inflammation, and cancer.

Conversely, overexpression of Ang-1 or of Ang-1 in combination with VEGF is characterized by the formation of large vessels. Studies showed that vasculature of mice lacking Ang-1 and Tie-2 remained at a primitive stage of development and failed to undergo further remodeling (76, 297, 349). Signaling through the PDGF-B and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) pathways may provide a link in mediating shear stress and angiogenesis (38). Angiopoietins and their Tie receptors, as well as ephrins and Eph-B receptors or macrophage chemotactic protein-1, are also likely candidates for mediating such cell-cell interactions. Multiple cellular mechanisms and an increasing combination of genes and molecules are involved in building and adapting blood vessels throughout a lifetime. Although endothelial cells are early key players in angiogenesis and remodeling, the interaction of endothelial cells with inflammatory cells such as macrophages, pericytes, and smooth muscle cells is also important for capillary stabilization and large vessel remodeling.

Angiogenesis: Pathophysiology

Although physiological angiogenesis and pathological angiogenesis are different, several mechanisms mediating pathological blood vessel growth resemble those during embryogenesis. In atherosclerosis, an increase in proangiogenic factors and a decrease in antiangiogenic factors stimulate angiogenesis; thus known as the angiogenic switch.

The vasa vasorum, a small network of microvessels penetrating the adventitial and outer medial layers of the vessel wall, run longitudinally along the length of the vessel and form circumferential arches around the lumen. These vessels are responsible for the transport of oxygen and nutrients to the adventitial layer of vascular wall as well as removal of waste products (32–34). During early and late stages of atherosclerosis, vasa vasorum angiogenesis and ectopic neovascularization occurs (35). It is thought to be an adaptive response to hypoxia or endothelial damage as it increases the oxygen and nutrient supply to the arterial wall to prevent ischemia (36). Vasa vasorum may contribute to atherosclerosis and plaque instability through neovessels and the delivery of factors that enhance plaque progression (37), as the density of vasa vasorum is higher in patients with cardiovascular disease compared to patients with no complications of atherosclerosis in the early stages of the disease (36).

During pathological angiogenesis, inflammatory cells such as monocytes/macrophages, platelets, mast cells and other leukocytes are often chemoattracted to the sites of inflammation or wound (364) and arteriogenic factors (VEGF, bFGF, TGF β−1, interleukin-8, PDGF, IGF-1, MCP-1, TNF-α and proteinases) in turn, attract endothelial and smooth muscle cells, fibroblasts, leukocytes or platelets (19, 39). Chronic inflammation and angiogenesis are interrelated processes. Although angiogenesis has a major role in wound healing and tissue repair, it can support the events of inflammation via leukocyte rolling, supply of nutrients, cytokines, and adhesion molecules to the site of injury (52, 337). However, hypoxia can upregulate NO/nitrite and H2S signaling that may significantly decrease inflammatory responses while facilitating vascular growth (22, 24, 166, 262).

Arteriogenesis: Physiology

Arteriogenesis is a process where mature arteries undergo remodeling often from interconnecting collateral arterioles after arterial occlusion, thus distinguishing it from other mechanisms of vascular growth (35,364). Nevertheless, there exists another hypothesis of de novo growth of arteries that requires formation of new arterial conduits via arterialization of the capillary network (200). In the case of remodeling pre-existing arteries, among the various factors that trigger arteriogenesis, hemodynamic forces play a major role in stimulating remodeling responses of collateral arteries (299). Vessels adapt to flow to withstand the shear stress to which they are subjected (Fig. 1A). Studies have shown arterial occlusion can disrupt the balance in blood flow leading to increased flow through collaterals. This increase in blood flow alters shear stress along the collateral network acting as an inductive factor for changes in smooth muscle cell number and function. As a result, blood flows through collateral anastomoses, increasing lumen diameter and wall thickness of the vessel (263, 397). In addition to hemodynamic forces, the collateral vessel wall may also be exposed to circumferential, longitudinal, and radial stress (303). However, the extent of the influence of these forces on the vessel wall remains unclear. The change in mechanical forces including shear stress has been shown to increase MCP-1 (monocyte chemoattractant protein 1) secretion in cultured human endothelial cells, leading to increased monocyte chemotaxis and adhesion (143, 331, 372). Subsequent adhesion of monocytes and their transformation into macrophages leading to the production of various cytokines and growth factors is required for the remodeling of existing arteries. For instance, early growth response protein 1 (EGR-1) was upregulated in the endothelium of growing collateral vessels in mice within the first 12 h after arterial occlusion (294). Additionally, it is reported that VEGFR-1 and multiple VEGF isoforms improved ischemic limb perfusion and mediate collateral growth in ischemic disease by mobilizing leukocytes and recruiting them to the pericollateral space (57, 387, 396).

Arteriogenesis: Pathophysiology

Stimulation of arteriogenesis an attractive treatment target for arterial obstructive disease. Several strategies have been reported to stimulate the process of arteriogenesis including shear stress, MCP-1 expression, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) infusion and use of other growth factors. Although these strategies have shown promise in animal models, more research has to be done in human subjects before arteriogenesis can be brought from bench to bedside.

Studies have shown that collateral arteries continue to remodel even after the end of shear stress, suggesting shear stress may be primarily required only for initiation of arteriogenesis (308). However, collateral vessels may also regress after shear stress ceases. It has been shown that collateral artery remodeling could restore blood flow to approximately 35% of distal perfusion levels, probably because the initially elevated shear stress progressively decreases. To check if this deficiency in blood flow restoration could be increased, artificial fluid shear stress was increased over the preexistent collateral vasculature in a rabbit femoral artery occlusion model (80). An increase in sustained artificial shear stress led to a maximal restoration of flow countering the idea that shear stress may only be important in early arteriogenesis.

Following occlusion of the main artery, collateral arteries are recruited at the site of occlusion. A decrease in the arterial pressure behind the occlusion, leads to an imbalance in blood flow, leading to redistribution of blood flow in collateral arterioles that balances high pressure with low-pressure regions. This causes an increased flow velocity and shear stress in the preexistent collateral arteries leading to activation of the endothelium and upregulation of MCP-1. A monocyte deficient mouse model clearly demonstrates the importance of monocytes and macrophage accumulation for collateral growth (15). Following arterial occlusion, macrophages derived from monocytes create an inflammatory environment leading to upregulation of TNFα. It has been shown that TNFα is a pivotal regulator of arteriogenesis and that knockout or inhibition of TNFα leads to significant reduction in collateral formation (116, 131). Activated lymphocytes also secrete cytokines and modulate cellular trafficking of monocytes/macrophages, thereby participating in arteriogenesis. Targeted genetic disruption of the T-cell receptor CD4, showed a reduction of blood flow recovery in the mouse hindlimb after femoral occlusion. Moreover, injection of isolated T-cells rescued blood flow recovery and increased macrophage accumulation highlighting an important role of lymphocyte/monocyte/macrophage interactions in arteriogenesis (341).

Lastly, GM-CSF, may also be important for arteriogenesis as a clinical study with patients who were not eligible for coronary artery bypass surgery showed that a short-term local and systemic application protocol augments collateral flow. Furthermore, it has been shown that infusion of GM-CSF following femoral artery occlusion in the rabbit stimulated collateral development (312). Additionally, combinational therapy of MCP-1 and GM-CSF increased blood flow perfusion to 40% after a week of arterial occlusion. The role of these regulators in arteriogenesis is evident, but highly complex. More research is needed to expand our knowledge of these molecules and how they are involved in collateral formation.

Molecular signaling in ischemic vascular remodeling

Ischemia is characterized by a decreased partial oxygen pressure (pO2) in the tissue and reduced tissue perfusion. This leads to conditions insufficient to meet metabolic needs and reduced nutrients to the tissue. The onset of ischemia triggers a cascade of events including molecular, and intra- and extracellular responses in the remodeling of the ischemic tissue (40, 333). This results in compulsory responses of vasodilation followed by new blood vessel formation and remodeling of the pre-existing vascular network. Vascular remodeling is essential for normal growth and development or tissue regeneration under pathological conditions or as a recovery process following an ischemic insult (193).

Many biological mediators, including growth factors, cytokines, matrix components, and hemodynamic changes are involved in effective vascular remodeling under physiological and pathological conditions (40, 333). Although endothelial cells take center-stage in this tightly regulated process, there are important contributions from and interaction with other cell types. Based on the type of the blood vessel, the organ vascular bed, and the cellular composition restructuring responses may vary. Nonetheless, some common molecular mechanisms work to stimulate vascular growth and remodeling.

Hypoxia

Oxygen is a key modulator of various cellular signaling mechanisms. It is a requirement for cellular respiration and survival resulting in tight control of the microenvironment to which cells are exposed. The levels of O2 concentrations can range from 10–20% in “Normoxia” or 1% to 10% under ‘Hypoxia”. Responsiveness to O2 concentrations also depends on the cell type and organ and the environment that prevails (156, 220, 273). Hypoxia typically results from insufficient blood supply to a tissue, which triggers cellular adaptations events including endothelial cell migration and proliferation (397). However, hyperoxia can also be detrimental to cells as it increases reactive oxygen formation leading to cell injury (45).

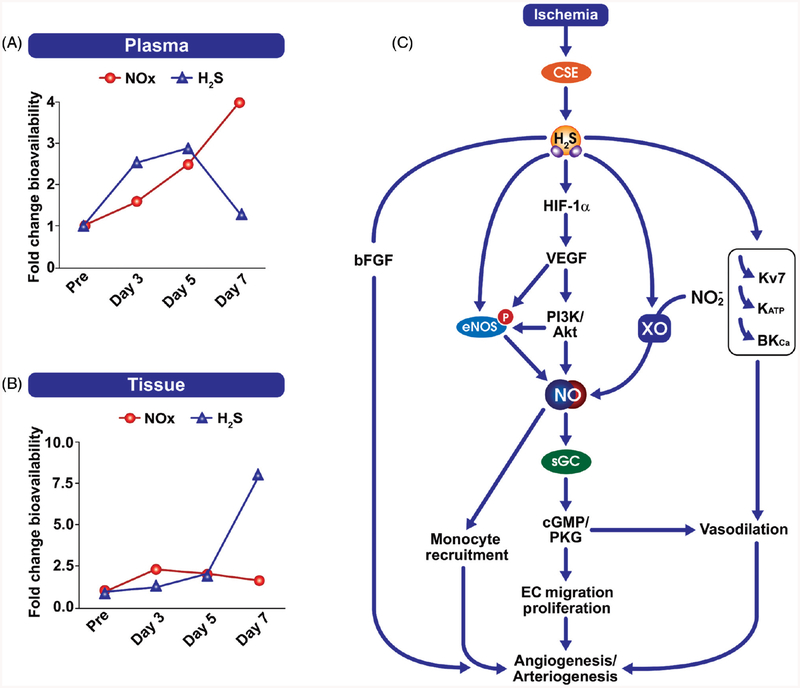

There are certain cellular enzymes that may not effectively function under hypoxia, while others are expressed and uniquely function to mediate compensatory effects in cell systems. NO and H2S are signaling molecules acting as sensors responsible for the acute vascular response to hypoxia (45, 164, 248). Hypoxia can destabilize eNOS by oxidizing its cofactor tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4). However, nitrite can be reduced to form NO, mediated by the enzymes xanthine oxidase (XO), deoxy-hemoglobin (Hb) and myoglobin (Mb). At the cellular level, hypoxia can also trigger CSE/H2S pathway that mediates reduction of nitrite to NO via XO or impacting NOS function (22). Importantly, these observations are not observed under normoxic conditions.

HIF and growth factors

Hypoxia plays a major role in regulating growth factor expression and/or function. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) is a key factor responsible for the cell adaptation during reduced O2 conditions (361). HIFα modulates responses to hypoxia by regulating vascular remodeling via VEGF and its receptor VEGFR, stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1), placental growth factor (PGF), PDGF, angiopoietin 2 (Ang-2) and stem cell factor (SCF) (285). bFGF is implicated in the regulation of both angiogenesis and arteriogenesis; however, it is believed to be induced by the pro-angiogenic monocytes mediating vascular remodeling (120). Importantly, therapeutic angiogenesis requires a combination of growth factors in the formation of stable and mature blood vessels (246). Apart from hypoxia, NO can upregulate the transcriptional activity and expression of HIF-1, but also stabilize it (251). Additionally, H2S has been shown to augment HIF-1 activity, subsequently stimulating ischemic vascular growth (22).

VEGF

The vascular endothelial cell growth factor family of proteins are crucial mediators of angiogenesis and vasculogenesis under pathophysiological conditions. Ischemic insult in the tissues induces VEGF expression in many cell types. HIF-1 regulates the expression of VEGF-A by binding to the hypoxia response element (HREs) in the promoter region of the VEGF gene (172). This in turn allows adaptation of the system to cope with decreased O2 partial pressure (pO2) by increasing vascular density. However, prolonged HIF activation can contribute to major structural alterations and can also lead to cell apoptosis (272).

VEGF-A is a dimeric glycoprotein that binds to both of its receptors VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 on the surface of endothelial and other cell types. Established literature suggests a strong affinity between VEGF-A and VEGFR-2 that increases its tyrosine kinase activity upon binding (371). VEGFR-2 is a crucial regulator of vascular development, and in the formation of the branched vasculature, whereas VEGFR-1 may act as a negative regulator of VEGFR-2 (79). In vitro studies have established that VEGFR-2 regulates endothelial cell proliferation, migration and survival mediated via phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathway (102). Animal studies performed on specific gene knockouts have substantiated the function and physiological relevance of these relationships (293,318). Studies performed in mice deficient in Flk-1/VEGFR-2 have established its crucial role in the development of hematopoietic and endothelial cells. Genetic knockout of VEGFR-2 is embryonically lethal in mice and will not survive beyond 9.5 days postcoitum. Similar studies corroborate these findings suggesting that tyrosine residue 1175 in VEGFR-2/Flk-1 (Y1175, human; 1173 in mouse) is essential for embryogenesis (293), whereas VEGFR-1 has been involved in aberrant angioblast division and excessive proliferation (155).

Studies performed in ischemic animal models have suggested the essential role for endogenous VEGF in post-ischemic angiogenesis and limb perfusion (119, 145). Inhibition of growth factors such as VEGF can have severe implications on vascular tone and hemodynamics necessary for changes in vascular remodeling. Adenoviral inhibition of VEGF performed in a unilateral hindlimb ischemic mouse model showed significantly reduced ischemia-induced angiogenesis and collateral formation along with critically reduced blood flow impairing muscle tissue recovery (145). Endogenous upregulation of VEGF levels has been observed in several studies in models of ischemia. In the hindlimb ischemia model, VEGF levels were upregulated at days 1 and 3 postsurgery, which reflected an increase in the number of capillaries (63). Another study observed increased expression of VEGF in ischemic limbs on day 7, returning to normal after day 14 postsurgery (192). These results clearly demonstrate a correlation between enhanced VEGF levels and ischemic revascularization. Other studies have confirmed induction of VEGF and angiogenesis in animal models of ischemia including mice, rats, and rabbits (119, 199, 353). Defective VEGF ligand/receptor expression leads to impaired angiogenesis after ischemia as observed in a murine model of peripheral arterial disease (PAD) with diabetes mellitus (DM) (24, 119). Additionally, VEGF may lead to changes in vascular integrity leading to dysregulation of the angiogenesis-regulatory network (304). These observations have been confirmed in clinical studies where VEGF is compromised in ischemic vascular diseases, including PAD and diabetes, leading to impaired collateral formation (160, 253, 384). However, other factors along with a balance between pro- and antiangiogenic markers also play a role in pathophysiological regulation of vessel growth (152). Additionally, both NO and H2S signaling have been shown to play a critical role in VEGF-induced ischemic vascular remodeling (22, 92, 163, 396). Moreover, genetic loss of either eNOS or CSE in mice affects VEGF expression, and impairs VEGF-mediated vascular growth and blood flow recovery in ischemic hindlimbs (22, 163, 396).

Other growth factors

Several other growth factors and cytokines including angiopoietin-1, placental growth factor (PlGF), platelet-derived growth factor, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (GCSF), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), and the FGF family (such as acidic FGF and basic FGF) have beneficial effects on revascularization including angiogenesis and collateral growth response. Monocytes/macrophages and other inflammatory cells can release these growth factors. Furthermore, other factors including fibronectin and proteoglycans will aid in remodeling of the extracellular matrix, which serves as a biological reservoir for growth factor accumulation and action. There are a number of animal studies performed in ischemic models that have demonstrated the role of these factors in improving vessel growth (114, 330). Moreover, these growth factors and cytokines induce, enhance, and mobilize progenitor cells and recruit them to the site of injury, contributing to the process of neovascularization (163,252).

FGFs are potent angiogenic inducers and are involved in stimulating fibroblast maturity. Adenoviral treatments of FGF in a rabbit hindlimb ischemia model have increased collateral growth and muscle perfusion (289). FGF proteins may induce angiogenesis and arteriogenesis, suggesting a therapeutic utility for peripheral vascular disease (PVD), is a systemic disorder that involves the narrowing of peripheral blood vessels (vessels situated away from the heart or the brain) as a result of arteriosclerosis or atherosclerosis (vascular lipid plaque deposition) (154). Clinical studies were performed on patients with angina pectoris and coronary artery disease (CAD) through FGF therapy via gene transfer (112, 113, 125). The Angiogenic Gene Therapy (AGENT) trial targeted FGF delivery as a therapeutic modality for CAD with results in patients of improved regional myocardial perfusion and treadmill times (112, 113). However, it seems that the clinical treatment has gender-specific angiogenic responses with males responding better than females (125). Another study confirmed the role of bFGF role in regulating arteriogenesis. It was observed in a diabetic mouse hindlimb ischemia model that reduced levels of bFGF lead to impaired collateral growth and blood flow (20). However, this impaired collateral circulation in diabetic mouse hindlimbs can be restored by exogenous bFGF therapy. In one of the major randomized clinical trials conducted in patients with intermittent claudication, called the “TRAFFIC study,” patients were treated with bFGF to study its therapeutic potential for angiogenesis (180). Improvements in peak walking time and ankle-brachial pressure index were observed in bFGF treated group compared to the placebo group. However, positive effects of these growth factors were also coupled with increased proteinuria in patients treated with bFGF (179,180). Platelet activation upregulates platelet-derived microparticles (PMP) that induce revascularization following chronic ischemia (32). PMPs mediate upregulation of growth factors including VEGF and PDGF that induce angiogenesis in ischemic myocardium of mice. Another study performed in a diabetic mouse model of ischemia has suggested the role of PDGF-C as a critical regulator and a novel target for the treatment of ischemic cardiovascular diseases in diabetes (225). GCSF is a potent cytokine that influences the function of granulocytes and improves the function of cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells and mobilizes bone marrow-derived progenitor cells to the site of injury and enhances collateral and capillary development (70, 175, 352).

Monocytes

Monocytes play a key role in mediating arteriogenesis. Stimulation of monocyte recruitment has evidenced an increase in responses toward collateral vessel growth under ischemic conditions (90,96). Studies indicate that recruitment and transformation of monocytes into macrophages at the site of injury is crucial during arteriogenesis (90, 96, 307). During early stages of vessel remodeling, signaling factors such as NO stimulate monocyte recruitment through modulation of cytokines and growth factor expression to promote vascular remodeling (181, 385). Additionally, tissue macrophages can stimulate the fusion of endothelial tip cells, leading to the formation of a vascular network (82). Growth factors such as PlGF and VEGF and signaling molecules including NO and H2S play an important role in monocyte recruitment (163, 311). PlGF activates monocytes resulting in the generation of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines via activation of VEGFR-1 (271).

Impairment of monocytes can lead to reduced ischemic vascular remodeling. Several animal studies have confirmed that accumulation of monocytes/macrophages was observed at the site of ischemia leading to the growth of collateral arteries following femoral artery ligation (5, 121, 309). Dysregulation of selectin signaling can impair monocyte recruitment under diabetic settings leading to reduced vascular remodeling (41). Treatment with MCP-1 has reduced P-selectin expression and induced monocyte recruitment to the ischemic site, thereby correcting the post-ischemic vascular deficits in remodeling and blood flow recovery in ischemic limbs (41). Another study performed using isolated human CD14 positive monocytes suggest that these cells can attain endothelial cell properties expressing their markers. The proliferation of these monocyte transformed endothelial cells is mediated by upregulation of VEGF, ICAM-1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) that induce vWF expression (83). A separate study performed in ICAM-1 knockout mice showed that there is a significantly decreased number of monocytes that resulted in delayed arteriogenesis (132). Furthermore, studies performed in osteopetrotic (op/op) mice demonstrated that collateral artery growth is impaired following inhibition of monocyte differentiation by blocking Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor (M-CSF) (15, 174). These studies strongly suggest that monocytes/macrophages play a key role in mediating different growth factors and chemokines and facilitate vessel remodeling through arteriogenesis.

Shear stress

Changes in blood flow stimulate adaptive changes in the vasculature in terms of structure and size of the blood vessels. Mechanical forces such as shear stress trigger a cascade of biochemical signaling that mediates changes in biological events. These external forces also induce morphological and structural adaptations in the endothelium and the vessel wall. Established literature suggests that increased shear stress can demonstrate vasoprotective roles that are mediated via growth factors including VEGF, FGF, and PDGF, and signaling factors such as nitric oxide. Recently, we have revealed that CSE/H2S signaling is altered in response to flow and regulates vascular remodeling mediated by altered shear stress (401).

Shear stress plays a key regulatory role in the process of arteriogenesis. In vitro studies have clearly established the importance of laminar flow in regulating endothelial signaling and functions leading to vessel remodeling (33, 412). Studies performed by increasing the collateral blood flow through increased shear pressures demonstrate a direct role of shear stress in increased vessel growth (80,270). A study performed in a pig model of hindlimb ischemia demonstrated that there was an increased number and size of collateral vessels formed following an abrupt increase in collateral blood flow (270). However, this shear-mediated collateral formation can be completely inhibited by blocking NO/VEGF/Rho signaling pathways (300). Shear stress can upregulate signaling mechanisms that promote monocyte recruitment and factors that facilitate its adhesion to the endothelium including MCP-1, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1 (282, 331). Furthermore, studies performed in multiple animal models have confirmed that MCP-1, VEGF, and ephrinB2 can induce collateral vessel formation through monocyte/macrophage recruitment. Additionally, a few studies have suggested that these monocytes/macrophages can be differentiated into endothelial cells (307, 331).

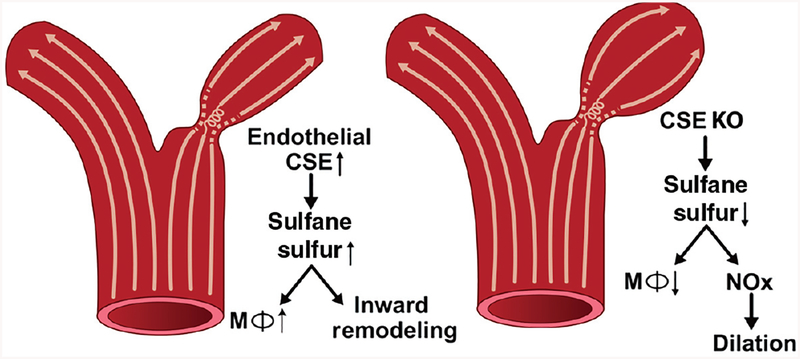

Unidirectional laminar flow is associated with elevated NO bioavailability, reduced oxidative stress, and suppression of proinflammatory genes. However, in disturbed flow regions, there is reduced NO production, increased reactive oxygen species and increased proinflammatory genes (402). Our lab has recently shown that CSE expression is regulated by shear stress (400). We found that oscillatory shear increased CSE protein expression, sulfane sulfur levels, and increased macrophage recruitment in regions of disturbed flow. Using the partial carotid ligation model to study inward vascular remodeling, genetic deficiency of CSE showed reduced medial thickening and a dilated arterial phenotype (Fig. 2). Interestingly, carotid vessel NO levels were increased in CSE knockout mice and that treatment with the NO scavenger cPTIO corrected the reduction in inward vascular remodeling (400). These findings reveal CSE expression to be important in shear dependent responses of atheroprone vascular regions involving both endothelial activation and flow-dependent vascular remodeling through altered NO bioavailability.

Figure 2.

CSE modulates flow induced vascular remodeling: CSE expression and sulfane sulfur production are enhanced by disturbed flow in conduit vessels. The enhanced CSE expression causes increased macrophage recruitment in these areas leading to flow induced vascular remodelling. In case of CSE knockout animals, they showed reduced sulfane sulfur levels following partial carotid artery ligation, defective inward remodeling, and a dilated vascular phenotype. The dilated phenotype is due to elevated NO bioavailability in CSE knockout carotid arteries.

Reactive oxygen species

Oxidative stress is a key player influencing many vascular functions under normal and diseased conditions (89, 110). Reactive oxygen species (ROS), including superoxide, hydrogen peroxide and the nitrogen derivative peroxynitrite, are reactive species that are associated with cardiovascular pathology (21, 71). Increased ROS production may also be associated with inactivation of NOS and reduced NO bioavailability. Sources of ROS formation may vary with studies reporting that NADPH-dependent oxidases (Noxs), superoxide dismutase (SOD), xanthine oxidase (XO), nitric oxide synthases (NOSs), and mitochondrial oxidases as all potent sources of ROS (68).

However, ROS may also serve role as a pro- angiogenic and arteriogenic mediators. Evidence from cardiovascular disease animal models and human studies suggests a significant role of NADPH oxidase activation in vascular remodeling and endothelial dysfunction. The isoforms of Nox including Nox1, Nox2, Nox4, and Nox5 may be expressed in endothelial cells. They vary in their subcellular localization and the type of ROS they produce, and can play important roles in regulating the production of VEGF and subsequent events of ischemic revascularization.

Studies performed in Nox2 deficient mice demonstrated the importance of the ROS mediated role in neovascularization under tissue ischemia (356). Reduction of Nox2-derived ROS production inhibited VEGF-A thereby affecting blood flow recovery and capillary density under ischemic conditions. Nox4 has also been implicated for its cytoprotective role and revascularization. Nox4 is highly expressed in vascular endothelial cells and is constitutively active and produces hydrogen peroxide. Protective roles of Nox4 were also observed by a reduction in oxidative and ER stress signaling. Animal studies performed in Nox4 knockout mice and transgenic overexpression reveal that endogenous Nox4 protects the vasculature during ischemic or inflammatory stress (64, 310). Similarly, upregulation of Nox4 in the cardiomyocytes plays a protective role post-myocardial infarction (MI). Nox4 modulates macrophage polarization toward an M2 phenotype, resulting in improved post-MI vascular remodeling by attenuating MMP-2 activity in cardiomyocytes (223).

Extracellular superoxide dismutase (ecSOD) is another ROS associated enzyme that plays a regulatory role in the maintenance of vascular functions (153). ecSOD is an endothelial expressing enzyme that regulates the NO bioavailability, blood pressure, and vascular O2•− levels. Studies performed in mice lacking ecSOD has demonstrated an impaired post-ischemic revascularization (153). Whereas, restoration of ecSOD in mice upregulates muscle H2O2 levels and accelerates vasculogenesis in ischemic muscles (365). Another study demonstrates that SOD reduces pulmonary hypertension, reduces ischemic injury, and induces vascular remodeling (326). Additionally, depletion of vascular ecSOD augments chronic hypoxic pulmonary hypertension and inhibits hypoxia-induced vascular remodeling (242). However, excessive and prolonged ROS generation inhibits cellular functions and induces apoptosis.

ROS and ER stress: Redox homeostasis in endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is quite important. A simple alteration in ER-regulated protein folding pathways may lead to enhanced ROS production, and enhanced ROS levels have a profound effect on the ER protein folding process, thus affecting cellular homeostasis. ER stress particularly plays an important role in the initial cellular adaptation of ischemia and angiogenesis. Mild ER stress upregulates VEGF expression and mediate appropriate tissue vascular supply under ischemia (103). Insufficient metabolites and oxygen supply and nutrient deprivation especially during the events of hypoxia/ischemia may upregulate ER stress signaling (19, 266). These stressors can be alleviated during neovascularization within the ischemic tissue. ER stress transcription factor, C/EBP homologous protein-10 (CHOP-10) can inhibit eNOS transcription subsequently inhibiting ischemic revascularization, whereas postischemic revascularization has been restored in CHOP-10 knockout mice (103). Accumulation of ROS leads to defective postischemic revascularization in mice models of diabetes and hypercholesterolemic mice (77, 370). It was observed that the inhibited vessel growth in diabetes is associated with an upregulation of ER stress markers under ischemia (53). However, the role of ER stress regulation is a complex and poorly understood phenomenon in relation to endothelial functions and vascular remodeling.

NO and H2S Pathophysiological Functions

Nitric oxide

Synthesis

NO, the first identified gasotransmitter, is generated in a variety of biological tissues and is an important regulator of key functions in the cardiovascular system (222, 417). NO is produced by enzymatic and non-enzymatic sources in and around vasculature. Enzymatic production of NO is primarily mediated by NOS family of proteins. As discussed in the introduction, NOS has three different isoforms namely neuronal NOS (nNOS), inducible NOS (iNOS), endothelial NOS (eNOS). Although these isoforms are genetically different, they all produce NO by catalyzing the oxidation of L-arginine to L-citrulline in the presence of various cofactors. All three NOS isoforms have been reported in the cardiovascular system; however, eNOS is the dominant NOS isoform in vascular endothelium (107).

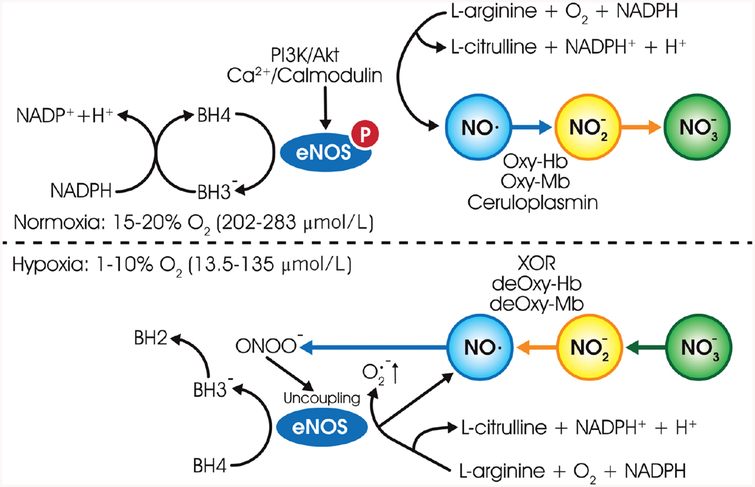

Although eNOS functions as a homodimer, it can be functionally divided into two major domains: a C-terminal reductase domain, and an N-terminal oxygenase domain (190). The dimer is stabilized by the binding of 5, 6, 7, 8-tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) and zinc to the N-terminal oxygenase domain. Electron transfer starts when reduced NADPH binds to the C-terminal of reductase domain of the one of a monomer of NOS dimer. Within this reductase domain, electron transfers from NADPH to FAD followed by flavin mononucleotide (FMN). FMN further shuttles the electron from reductase domain to the heme of oxygenase domain of the NOS dimer. The reduced heme then catalyzes the conversion of L-arginine to L-citrulline with the NO being the by-product under normoxic conditions (Fig. 3). However, under hypoxic conditions, nitrite may be reduced by reductases, including xanthine oxidase, deoxyhemoglobin, deoxymyoglobin to produce NO. Further eNOS uncoupling occurs under hypoxic stress leading to the production of superoxide instead of NO. In addition, BH4 oxidation also occurs further leading to eNOS uncoupling and conversion of BH4 to BH2 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

The nitric oxide synthesis pathway: under normal oxygen parameters (normoxia), in the presence of NAPDH and cofactors such as BH4, FMN, FAD, and eNOS catalyze the conversion of L-arginine to L-citrulline and NO. Further, one electron oxidation of NO catalyzed by ceruloplasmin in plasma and cytochrome c oxidase in tissues yields nitrite, further with relatively faster two-electron oxidation yielding nitrate by heme proteins in blood and tissues. In the absence of oxygen (hypoxia), nitrite is reduced by reductases, including xanthine oxidase, deoxyhemoglobin, deoxymyoglobin to produce NO. Further, oxidative stress leads to BH4 oxidation and eNOS uncoupling leading to superoxide production.

While eNOS is the primary source of NO in the vasculature, enzyme-independent NO generation also occurs. It is reported that dietary nitrate enters the enterocirculatory system and gets absorbed and concentrated in salivary gland where it is readily converted to nitrite by facultative anaerobic bacteria on the surface of the tongue (295). This nitrite is swallowed and may be converted to nitrous acids and nitric oxide under acidic conditions (pH 3) in the lumen of the stomach (13). Nitrite may also re-enter the circulation and be reduced to NO during ischemia or hypoxic conditions, the reactions mediated by xanthine oxidase (XO) (381), deoxyhemoglobin (106), deoxymyoglobin (329), or aldehyde oxidase (AO) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

A schematic diagram of nitrate, nitrite, and nitric oxide (NO) pathway from exogenous (dietary) sources: dietary nitrate taken (1) is absorbed systemically (2) and is concentrated 10-fold in the salivary gland and enters the enterosalivary circulatory system where it is converted to nitrite by bacterial nitrite reductases on the dorsum of the tongue (3). When nitrite reaches the lumen of the stomach, acidic gastric juice converts nitrite to nitrosating species that can further react with ascorbic acid in gastric juice to yield NO (4). It can also reenter the circulation as nitrite and be reduced to NO by xanthine oxidase (XO) and aldehyde oxidase (AO) (4). Nitrite in the arterial circulation may also be reduced to nitric oxide due to hemoglobin deoxygenation causing vasodilation (5).

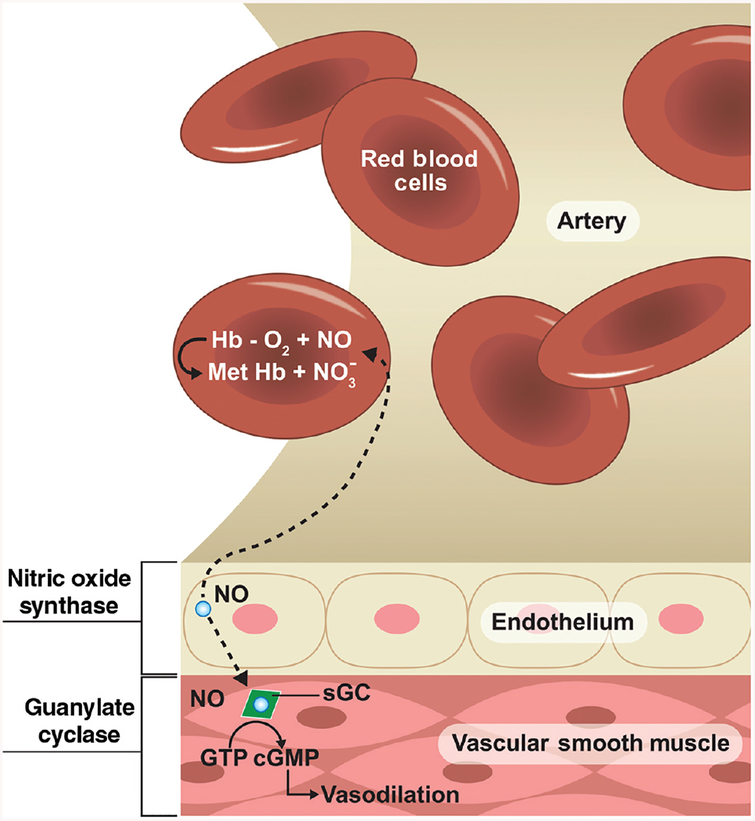

The rapid diffusion of nitric oxide between cells is crucial for understanding its biological activity. Primarily, nitric oxide produced in the endothelium activates soluble guanylate cyclase, which in turn initiates the production of the messenger cGMP (cyclic guanosine monophosphate). cGMP causes the smooth muscle cells in the vessel walls to relax leading to vasodilation. NO also diffuses into red blood cells and quickly reacts with oxyhemoglobin to form methemoglobin and nitrate (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Principal reactions of nitric oxide in tissues: nitric oxide produced in the endothelium diffuses into vascular smooth muscle cells and activates soluble guanylate cyclase, which in turn initiates the production of the messenger cGMP (cyclic guanosine monophosphate). cGMP relaxes smooth muscle cells in the vessel walls leading to vasodilation. NO can also diffuse into red blood cells and react with oxyhemoglobin to form methemoglobin and nitrate.

NO chemistry and measurement

Chemical properties

Nitric oxide (NO) has been established as a signaling molecule regulating several pathophysiological processes due to its unique chemical properties. It can easily diffuse across cellular membranes and into tissues with little reactivity (177, 386). It is important to understand the chemical properties of NO, which is a principal determinant of its biological action. NO is relatively unstable (half-life: 2~30 s) due to its unpaired electron, and it can gain or lose one electron to form the ions NO− or NO+ (196). However, nitric oxide is not highly reactive just because it is a free radical. This is due to the fact that the unpaired electron of NO is in the higher energy antibonding Pi orbital that can react only with another unpaired antibonding Pi electron from another free radical. However, most of the physiologically available free radicals do not have a unpaired antiboding Pi electron. Consequently, NO reacts only with a select few free radicals and transition metals like heme iron at a faster rate to have any physiological consequences.

NO has vastly different reaction rates with different molecules as a guide, the biological chemistry of nitric oxide can be simplified by reflecting its biological activity. NO can react with oxygen and water and be converted into nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and nitrous acid (HNO2), respectively. HNO2 is a weak and monobasic acid (pKa: 3.398). NO may also further oxidize to nitrate (NO3−). NO reacts with O2− (superoxide anion) to form peroxynitrite anion (OONO−), the deprotonated form of peroxynitrous acid. Peroxynitrite (ONOO−) is an unstable structural isomer of nitrate, which is generated from the reaction between NO and superoxide. Importantly, peroxynitrite is a not a free radical, but rather a powerful oxidant.

Decomposition of peroxynitrous acid involves the formation of HO and NO2 as intermediate and this accounts for peroxynitrite’s higher oxidizing capacity, as both the intermediates are potent oxidants. Whereas OONO- reacts with unsaturated fatty acids to form lipid peroxide, NO shows the opposite effect of terminating lipid peroxidation chain reaction. Consequently, NO per se is not toxic unless it gives rise to peroxynitrite, which is toxic. NO is involved in activation of guanylate cyclase (sGC), which is responsible for downstream signaling effects to regulate vascular tone. As NO is a small molecule that rapidly diffuses into capillary circulation and is consumed by oxyhemoglobin, its tissue level is determined by its rate of production and latter two factors.

NO also can be reduced to nitroxyl (HNO). Unlike most all other acid-base equilibriums, the chemistry of HNO is complex due to its electronic ground states: the protonated HNO species is a ground state singlet (1HNO) and the deprotonated anion is a ground state triplet (3NO−). Deprotonation of 1HNO or protonation of 3NO− requires a change in the electronic spin state, which make this process slow. Hence, numerous other reactions will occur before they deprotonate or protonate to set up an acid-base equilibrium (317).

Measurement

It is extremely important to specifically measure exact NO levels in biological samples to understand its role in physiological and pathological processes. To date, there are several commonly used methods to measure NO.

Griess assay

Nitrite (NO2−) is one of the primary, stable, and nonvolatile breakdown products of NO. The Griess assay is used to measure nitrite as a surrogate for NO bioavailability. This assay was originally described by Griess in 1879 (269), which uses sulfanilamide and N-1-napthylethylenediamine dihydrochloride (NED) under acidic (phosphoric acid) conditions. Through the years, many modifications to the original reaction have been described. This assay can be used to detect nitrite in a variety of biological and experimental liquid matrices such as plasma, serum, urine, and tissue culture medium. The nitrite sensitivity depends on the matrix. The limit of detection is 2.5 μmol/L nitrite (in ultrapure, deionized distilled water). This method has become one of the most popular assays for determining NO bioavailability. However, there are several issues that must be considered including: (i) this is an indirect assay of NO levels; (ii) the spectrophotometric plate reader-based assay is limited in its detection sensitivity; and (iii) simultaneous measurement of nitrite and nitrate often overestimates the amount of NO produced based on the fact that nitrate metabolism can be independent of NOS activity.

Chemiluminescence detection and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectrometry

Real-time NO analysis can be performed using a GE Sievers Nitric Oxide Analyzer (NOA 280i) or other similar NO analyzers. Using highly sensitive, ozone-chemiluminescence technology, it has unsurpassed versatility for liquid and exhaled breath nitric oxide (NO) measurement. This assay takes advantage of NO reaction with ozone to generate photons within a reaction chamber enabling highly sensitive detection of NO metabolites including nitrite, nitrate, and nitrosothiols in the biological samples. A reaction sparger is coupled to the detector that allows significant experimental flexibility to measure NO levels itself; the amount of NO contained within specific metabolites upon chemical liberation, and rates of NO production from chemical and cell models. Another method of direct NO detection is by using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectrometry, which can be used to detect formed stable NO adduct after endogenous NO reacted with several iron complexes, such as hydrophobic Fe/diethyldithiocarbamide or Fe2+-N-methyl-d-glucaminedithiocarbamate. Low sensitivity and trapping agent selectivity can pose challenges for this approach (126).

For liquid samples, chemiluminescent detection uses different workflow techniques to measure nitrate, nitrite, and nitrosothiols. Nitrate is the major oxidation production of NO in the presence of oxyhemoglobin or superoxide, and chemiluminescence can measure total nitric oxide by converting the nitrate and nitrite to NO using vanadium (III) chloride in hydrochloric acid at 90°C. Nitrite is the major oxidation production of NO in the absence of oxyhemoglobin or superoxide, and can measure nitrite by converting the nitrite to nitric oxide using iodide and acetic acid at room temperature. Measurements of low molecular weight compounds such as S-nitrosoglutathione are made using a Cu(I)/Cysteine reagent. Measurements of higher molecular weight species such as S-nitroso-albumin or hemoglobin are made using iodine, iodide, and acetic acid after chemical or chromatographic removal of nitrite.

Electrochemical detection

The NO electrochemical sensor allows the measurement of NO concentration in the biological samples ranging from subnanomolar to micromolar levels (409). NO can be either electrochemically reduced or oxidized, and the resulting transfer of electrons is measured as a current proportional to the NO concentration. One of the commercially available systems is amiNO, which allows consumers to choose the size, flexibility, durability, sensitivity, and response time for their system with a limit of NO detection (1.0 nmol/L).

Fluorescence probes

Fluorescent NO probes have been developed to facilitate real-time detection of NO. There are various fluorescent probes available for the detection of NO including the well-used diacetate based diaminofluorescein and rhodamine dyes (187,408). Additionally, recent developments have seen a flurry of fluorescent dyes with improved chemical detection, which includes o-diamino aromatic compounds (283, 346), luminescent lanthanide complexes (354), transition-metal complexes (48, 127), quantum dots (65, 379), and carbon nanotube sensors (105, 149). The sensitivity of these probes are <10 μmol/L, but these fluorescent probes may have issues with specificity (detection of other thiols vs. nitrosating species) and autofluorescence based on the biological substances.

Implications for vascular growth and remodeling

As discussed earlier, vascular remodeling is the process during which the vessel wall reorganizes its cellular and extracellular components in response to a chronic stimulus, for instance, arterial occlusion. This arterial occlusion initiates a signaling cascade that leads to ischemic vascular remodeling creating a smaller vascular lumen. This reduction in the artery function leads to changes in blood flow and oxygen tension. Both angiogenesis and arteriogenesis respond differently to these changes. Under pathological conditions, the change in hemodynamic forces acts as a primary stimulator of ischemic vascular remodeling. Previous reports have identified the essential molecules for vasculogenesis, angiogenesis, and remodeling, and that when deleted, cause embryonic lethality due to vascular defects (57, 231, 413). Among these molecules, NO is essential for endogenous collateral development and angiogenesis under ischemia.

Following occlusion of artery, as an initial response to the ischemic environment, NO-mediated vasodilation occurs temporarily leading to increased perfusion of collaterals. An increase in collateral recruitment leads to an increase in wall shear stress, which is a mechanical stimulus that activates eNOS expression and activity. Studies have shown that collateral artery diameter and blood perfusion within the ischemic hindlimb was significantly reduced in eNOS−/− and L-NAME treated mice subjected to femoral artery ligation (FAL) (260). Furthermore, eNOS−/− mice showed reduced VEGF-induced mobilization of endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) and increased mortality after myelosuppression. However, infusion of wild-type progenitor cells, rescued the phenotype in a mouse model of hindlimb ischemia, suggesting the importance of eNOS in the mobilization of progenitor cells for the collateral growth (3). On the contrary, another group has shown that ischemic challenge in eNOS−/− showed defective arteriogenesis, but no impairment in endothelial progenitor cell recruitment. Additionally, they showed that the defects could be rescued by intramuscular delivery of an adenovirus encoding a constitutively active allele of eNOS, eNOS S1179D (395). A study in dogs showed a 6.2-fold increase in eNOS expression in the growing collaterals but not in mature collaterals following chronic occlusion of the left circumflex artery, suggesting the importance of eNOS in the development of collateral vessels (37). However, another study in mice suggested eNOS activity is not required for collateral growth (214). In this study using FAL in various eNOS mutant versus wild-type (WT) mice revealed a similar decrease in collateral-dependent blood flow until day 7, suggesting delayed collateral growth rather than inhibition. No difference in collateral arteries of eNOS mutant versus WT mice was observed at 1 and 3 weeks suggesting impaired recovery of blood flow in eNOS deficient mice may be due to insufficient vasodilation and not inhibition of collateral growth. In summary, eNOS is important for ischemic vascular remodeling and blood flow restoration.

Besides eNOS, NO from other sources also plays a crucial role in ischemic vascular remodeling. Studies have shown that rabbits subjected to unilateral hindlimb ischemia showed defective collateral formation when treated with L-NAME thus interrupting NO production (34). In another study, targeted deletion of eNOS delayed collateral formation but finally, normal development was observed following FAL. However, iNOS deletion blunted collateral vessels formation but with only a mild reduction of blood flow following FAL. When they combined the inhibition of both isoforms of NOS, it completely abrogated arteriogenesis suggesting the importance of NO from different enzymatic sources in collateral formation with important roles of both iNOS and eNOS (357). In addition to NOS mediated NO production, bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells, especially monocytes produce NO as a result of increased shear stress following arterial occlusion facilitating collateral formation (305, 357).

Work from our group has demonstrated that exogenous nitrite therapy is an effective therapeutic intervention stimulating collateral formation by producing NO specifically at the site of ischemia. Chronic sodium nitrite therapy restored blood flow, vascular density, and endothelial cell proliferation at the ischemic site in a NO-dependent manner following FAL (176). Another study in humans showed dilation of arteries under hypoxia that is subjected to sodium nitrite infusion suggesting hypoxic augmentation of nitrite-mediated vasodilation in vivo (203). A similar study in humans also showed nitrite-induced vasodilation is associated with a reduction of nitrite to NO and showed that hemoglobin acts as a nitrite reductase, causing hypoxic vasodilation (61). Furthermore, in a canine study, collateral growth was induced by brief (2 min), repetitive episodes of myocardial ischemia. In this study, collateral blood flow was significantly hampered in L-NAME-treated animals compared to controls suggesting that the induction of coronary collateralization requires the production of NO (211).

In addition to exogenous addition of NO donors and NO metabolites, shear stress may act as a potential trigger for NO release during ischemic stress. As discussed above, shear stress, which is already highest at the arteriolar level, further increases following arterial occlusion. Studies have shown that endothelium-dependent relaxing factors, including NO, can increase as a result of shear stress (215). Hence, this could result in the local release of NO primarily at the site of ischemia to induce collateral development. Supporting this hypothesis, studies have shown that rabbits subjected to chronic elevation of shear stress by placing an arteriovenous shunt between the common carotid artery and the external jugular vein in the carotid arteries showed increased NO production. However, inhibition of NO synthesis by L-NAME inhibits adaptive shear stress regulation in vessels subjected to chronically increased blood flow (358).

Hydrogen sulfide

Synthesis

Hydrogen sulfide is the third gasotransmitter to be discovered alongside NO and CO. H2S is primarily produced from L-cysteine and homocysteine catalyzed by two pyridoxal-5′-phosphate (PLP)-dependent enzymes namely cystathionine β synthase (CBS) and cystathionine γ lyase (CSE) in the transsulfuration pathway (135, 235). CBS catalyzes the condensation of homocysteine with cysteine to yield cystathionine liberating H2S. This reaction is closely related to the canonical reaction catalyzed by CBS involving the condensation of homocysteine with serine liberating H2O (197). Although CBS has been identified in tissues throughout the body (275) it is predominantly present in the central nervous system and liver (1, 108). CSE catalyzes the conversion of cystathionine to L-cysteine and α-ketobutyrate (Fig. 6). Further, it catalyzes the conversion of L-cysteine to form thiocysteine, pyruvate, and ammonia. Thiocysteine in turn may nonenzymatically breakdown to form pyruvate and H2S (137, 197, 247). CSE has predominantly located within the vasculature (378). Besides CBS and CSE, 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (MPST), primarily located in the mitochondria, also enzymatically produces H2S. Cysteine aminotransferase (CAT) converts cysteine to 3-mercaptopyruvate, from which H2S is generated by MPST (235, 275, 399) (Fig. 7).

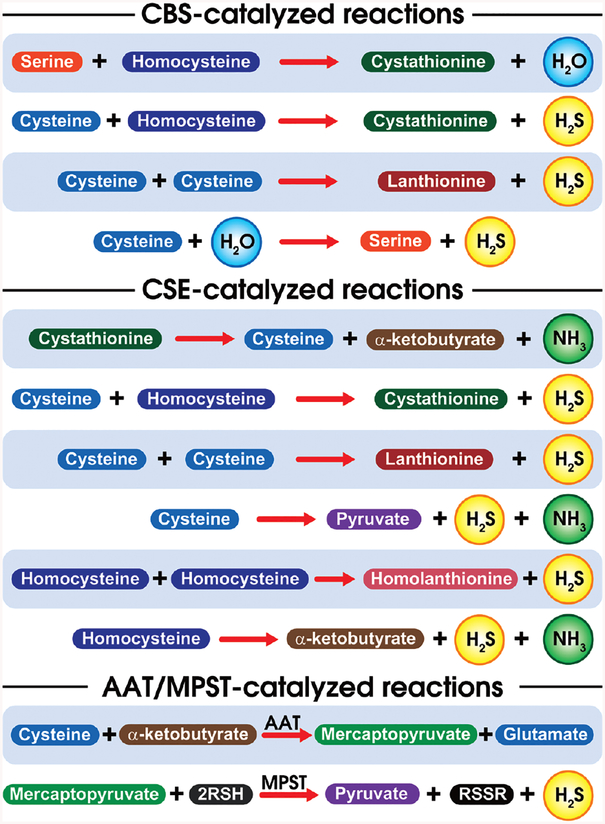

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of H2S generating reactions: this figure is a schematic representation of H2S generating reactions of CBS, CSE, and MPST. CBS and CSE, catalyze elimination/addition reactions at the β- and γ-positions of sulfur-containing amino acids, respectively.

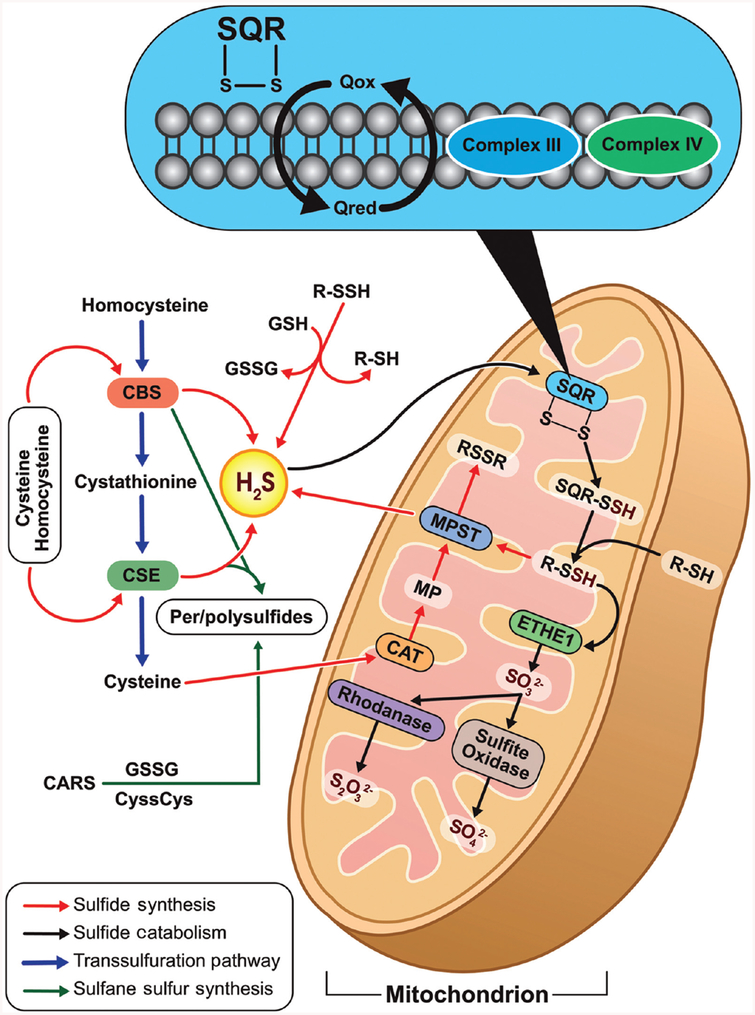

Figure 7.

Regulation of H2S production: L-Cysteine can be converted to H2S via cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) or cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE), both of which require pyroxidal-5-phosphate for their activity. L-Cysteine can also be converted to 3-mercaptopyruvate via cysteine aminotransferase (CAT), which can, in turn, be metabolized by 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (MPST) to generate H2S. Further H2S is oxidized by sulfide quinone oxidoreductase (SQR) in mitochondria to produce SQR-persulfide. Sulfur dioxygenase oxidizes persulfide to sulfite (H2SO3), which is metabolized by rhodanese to produce thiosulfate (H2S2O3). The balance between H2S synthesis and catabolism determines its cellular concentration.

Intracellular H2S exists in various biochemical forms including free sulfide, acid labile sulfide, and bound sulfane sulfur. These sulfide pools are important in regulating the amount of bioavailable of sulfur, with the most relevant being acid labile and bound sulfane sulfur (281, 325). Acid-labile sulfur releases H2S in an acidic microenvironment (pH ~ 6.0 or less). This pool consists of sulfur present in iron-sulfur clusters such as rubredoxins and ferredoxins. Due to its highly unstable nature, H2S may be released when needed to regulate cellular functions. Bound sulfane sulfur containing divalent sulfur bond can release H2S in basic condition (pH 8.4) or be reduced by catalase generating H2S suggesting the cellular redox state is important in regulating sulfane sulfur bioavailability (235, 250, 281, 325).

H2S is also generated by enterobacteric microflora, mainly by colonic sulfate-reducing bacteria (321). In the gut, H2S regulates functions such as inflammation and ischemia/reperfusion injury. Its bioavailability is associated with gastrointestinal disorders such as ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, and irritable bowel syndrome (336).

Chemistry and measurement of hydrogen sulfide

Chemistry of H2S

H2S is a colorless gas with the odor of rotten eggs, and is slightly soluble in water, resulting in the formation of a weak acid with an acid dissociation constant (pKa1) of 7.04 and pKa2 of 19 at 37°C (324). According to the acid dissociation constant, at physiological pH and 37°C, ~20% of sulfide is present as an H2S gas, whereas at physiological pH and 25°C, ~40% of sulfide is present as an H2S gas. Anionic deprotonation products of H2S are HS− and S2−. In vivo, pH favors sulfide existence primarily as H2S gas and its highly reactive anion, HS− (138, 324). Sulfur of H2S is in −2 oxidation state and can be readily oxidized. In fact, H2S gas does not react readily with oxygen, but in aqueous solutions H2S can readily undergo oxidation. Oxidation products include many sulfur compounds, such as polysulfide, polythionates, elemental sulfur, thiosulfate, sulfite, sulfate, sulfide radical, and disulfide. In addition, under neutral pH, sulfide can also form complexes with divalent metals and protein with metal center (i.e., heme) (93, 189).

The terms thiol, sulfhydryl, and mercaptan are all used interchangeably to mean the same functional group (−SH). When two sulfur atoms form a single bond with each other, it is called disulfide (−S−S−). Depending upon the nonsulfur moieties attached to either sulfur atoms of a disulfide group, it can be named differently such as disulfide or dialkyl disulfide (RSSR), persulfide or alkyl hydrodisulfide (RSSH). The free radical form of persulfide or disulfide is called perthiyl (RSS·). If the R group in persulfide is a cysteine residue in a peptide (i.e., if persulfide was formed by transfer of a thiol to an existing thiol on a cysteine), the protein is considered to have undergone sulfuration (94). RSnH is similarly called (alkyl)hydropolysulfide and RSnR (alkyl)polysulfide (Fig. 8). Importantly, given the low Km of H2S reaction with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (0.73 M−1s−1) compared to superoxide (2.0 × 102 M−1s−1), it is likely that reactive oxygen species may be a major pathway for hydroper- and hydropolysulfide formation.

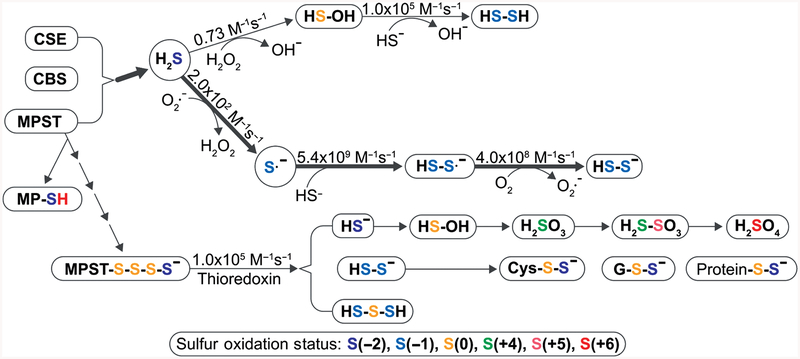

Figure 8.

Reactivity of H2S and H2Sn: H2S is generated by CSE, CBS, and MPST. H2S can undergo one-electron oxidation or two-electron oxidation to form HSOH or form S·-, respectively. Both of them can be oxidized to persulfide. According to the bimolecular rate constants for reaction of H2S oxidation, H2S is oxidized slower by H2O2 than that of superoxide. MPST receive sulfur from 3MP to generate MPST polysulfide chain, which can be reduced by thioredoxin (Trx) to release H2Sn, such as H2S, H2S2, H2S3, etc. Once H2S is produced, it can be oxidized to hydrogen thioperoxide (HSOH), sulfurous acid (H2SO3), thiosulfuric acid (H2S2O3), sulfuric acid (H2SO4), etc. In addition, it also reacts with intracellular thiols (cysteine, glutathione, and protein cysteine residue) to form their persulfide forms.

Measurement of hydrogen sulfide

Lack of understanding of the physiological concentrations of sulfide can be attributed to inaccurate and less-sensitive measurements. It is important to accurately measure biological concentrations of sulfide due to toxicity at higher concentrations. This problem has been overcome with recent developments in the detection of sulfide and its various pools with specific and sensitive techniques.

Many detection techniques have been developed, including colorimetric measurements, electrochemical assays, gas chromatography, etc. However, inconsistent results have been reported with these techniques due to sulfide volatilization, harsh treatment conditions, and high background activity (165). To address the physiological and pathological role of sulfide, accurate detection in biological samples remains an important consideration. Below we discuss commonly used techniques to measure H2S and associated considerations.

Methylene blue assay

The methylene blue assay was first described by Fisher in 1883 to measure hydrogen sulfide in natural waters. This assay is a simple spectrophotometric-based assay that employs zinc acetate to “trap” sulfide that is subsequently reacted with N, N-dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine under acidic conditions causing the formation of methylene blue. However, several issues have been noted by investigators including insensitive nature, harsh chemical treatments, and inability to obey Beer’s law contributing to high variability and often inaccurate measurements of biological sulfide (249, 324). Thus, use of the methylene blue assay to accurately measure biological sulfide levels may not be robust or reliable.

Electrode detection

There are many electrodes that have been developed to detect biological levels of H2S. A typical electrode consists of a sensing electrode (working electrode) and a reference electrode separated by an electrolyte, such as sulfide ion selective electrode (284, 367), gold electrodes (292), glassy carbon electrode (GCE) (319), inkjet-printed sulfide-selective electrode (IPSSE) (274) etc. Most electrode approaches have a detection range of 1~10 μmol/L. However, recent use of nanomaterials (such as carbon nanotubes and graphene) increase the sensitivity of H2S measurement, but its application to biological samples remains poorly understood due to strong chemical pretreatment.

Gas chromatographic analysis

Gas chromatographic analysis of H2S may be performed after its derivatization to bis (pentafluorobenzyl) sulfide (95), which is extracted into organic solvents followed by GC analysis. Measurement of H2S can also be performed by direct analysis of the headspace H2S gas (without derivatization) and subsequently analyzed through gas chromatography with a different detector, such as flame photometric detector (FPD) (230, 362), pulsed flame photometric detector (PFPD) (258), or mass spectrometery (MS) (129). These approaches are clearly sensitive and specific for gas H2S samples.

Fluorescent probes

In the past decade, a number of reaction-based fluorescent probes for sulfide have been developed, including Quantum Dot (QDs), dansylazide (DNS-Az), 7-azido-4-methylcoumarin (C-7Az), a dual-reacting probe based on 1,8-naphthalimide as fluorophore, and WSP1–5 7-glycidyloxy-9-(2-glycidyloxycarbonylphenyl)-2-xanthone (FEPO) (46, 227, 264, 265, 296, 375, 404). However, most of these probes exhibit some limitations such as slow response time, detection limit sensitivity, and interference from other biological thiols. Additionally, some of these fluorescent probes have excitation-emission wavelength (490–700 nm) near tissue autofluorescence wavelength and are affected by H2S levels that can be quickly scavenged by proteins or small molecular weight thiols (324). Fluorescent probes, such as SSP2 and SSP4, have been developed for sulfane sulfurs including persulfides, hydrogen persulfide, polysulfides, and protein-bound elemental sulfur. These probes work effectively under neutral to weak basic pH by releasing strong fluorescent molecules via fast intramolecular cyclization and are useful for measuring overall total sulfane bioavailability (17, 47).

Chemiluminescent detection

A unique method has been developed based on masking of fluorophores by azide. Upon exposure to H2S environment, the fluorophore gets reduced to release fluorescence. Ideally, azide-masked fluorophores function as selective probes for H2S detection. However, the inherent photosensitive azide functional group may reduce the accuracy to detect H2S and limit its application. To address the limitation of H2S-mediated azide probe, a chemiluminescent scaffold was developed to avoid unwanted photoactivation, such as azide-masked luminol compounds CLSS-1 and CLSS-2(340). Unmasking of the azide to release the free amine liberates luminol (for CLSS-1) or Isoluminol (for CLSS-2). Both of them can irreversibly react with sulfide to generate the luminescent signal. The limits of detection of CLSS-1 and CLSS-2 for H2S measurement are 0.7 and 4.6 μmol/L, respectively (7). CLSS-1 and CLSS-2 are not sufficiently soluble in neutral pH buffer, but another group has developed a water-soluble Mn-doped ZnS quantum dots (QDs) for chemiluminometric H2S measurement with a limit of detection of 0.1 nmol/L (6). These chemiluminescent detections of biological sulfide are highly specific and sensitive but do not resolve other sulfide metabolites.

Monobromobimane detection

Significant progress and improvements have been made regarding accurate hydrogen sulfide detection using monobromobimane (MBB) in biological samples. MBB can react with free hydrogen sulfide generating sulfide dibimane (SDB), which is quantified using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with fluorescence detection or mass spectrometry. MBB/HPLC assay is a much more sensitive and selective method than that of the methylene blue method (324). In addition, the MBB LC-MS/MS assay has been shown to both improve the assay’s sensitivity and also verifies the validity of the MBB/HPLC method (322). On this basis, our group developed novel workflow methods to measure acid-labile sulfide and bound sulfane sulfur by using an acidic releasing buffer (pH 2.6) containing Tris(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP) followed by MBB/HPLC detection (323, 325). In this way, MBB-labeling protocols can be used to measure hydropersulfide/polysulfides and other small molecular weight sulfane sulfurs bound with significant precision and accuracy (140). However, given the progressive alkylation activity of MBB, it is important to be aware of reaction incubation times (27). Thus far, these analytical approaches have provided useful, accurate, and reliable ways to measure biological hydrogen sulfide across different studies (163, 268, 281).

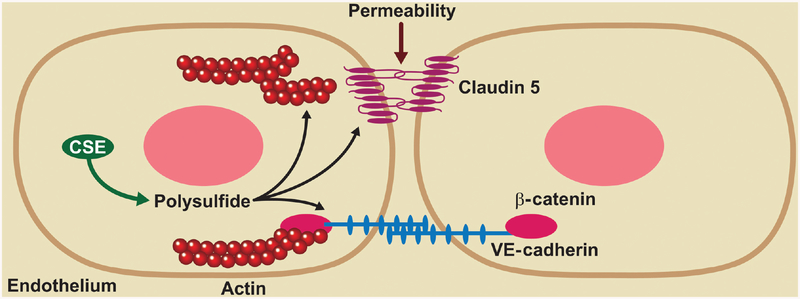

Implications for vascular growth and remodeling