All organisms regulate cell cycle progression by coordinating cell division with DNA replication status. In eukaryotes, DNA damage or problems with replication fork progression induce the DNA damage response (DDR), causing cyclin-dependent kinases to remain active, preventing further cell cycle progression until replication and repair are complete.

KEYWORDS: cell cycle, cell division, checkpoint, DNA damage, SOS response

ABSTRACT

All organisms regulate cell cycle progression by coordinating cell division with DNA replication status. In eukaryotes, DNA damage or problems with replication fork progression induce the DNA damage response (DDR), causing cyclin-dependent kinases to remain active, preventing further cell cycle progression until replication and repair are complete. In bacteria, cell division is coordinated with chromosome segregation, preventing cell division ring formation over the nucleoid in a process termed nucleoid occlusion. In addition to nucleoid occlusion, bacteria induce the SOS response after replication forks encounter DNA damage or impediments that slow or block their progression. During SOS induction, Escherichia coli expresses a cytoplasmic protein, SulA, that inhibits cell division by directly binding FtsZ. After the SOS response is turned off, SulA is degraded by Lon protease, allowing for cell division to resume. Recently, it has become clear that SulA is restricted to bacteria closely related to E. coli and that most bacteria enforce the DNA damage checkpoint by expressing a small integral membrane protein. Resumption of cell division is then mediated by membrane-bound proteases that cleave the cell division inhibitor. Further, many bacterial cells have mechanisms to inhibit cell division that are regulated independently from the canonical LexA-mediated SOS response. In this review, we discuss several pathways used by bacteria to prevent cell division from occurring when genome instability is detected or before the chromosome has been fully replicated and segregated.

INTRODUCTION

Even though DNA is a stable macromolecule for storing genetic information, chromosomes must be replicated and segregated properly before cell division can occur (1). Further, DNA can be modified from endogenous or exogenous sources resulting in mutagenesis or DNA damage (2, 3). Sources of DNA damage include endogenous metabolic intermediates, such as reactive oxygen species, as well as exogenous sources, including radiation and chemicals that react directly with DNA, causing several types of lesions (3–5). In addition, many antibiotics produced by plants and bacteria can cause DNA damage to competing organisms as a defense mechanism or to provide a fitness advantage (6). Therefore, DNA damage is a pervasive problem encountered by all organisms regardless of their natural environment.

DNA damage prevents accurate DNA replication, though the exact mechanism differs depending on the type of lesion encountered. For example, Escherichia coli exposure to UV light results in a very rapid decrease in DNA replication due to the production of thymine-thymine dimers and 6-4 photoproducts (7, 8). Replicative DNA polymerases cannot utilize thymine dimers as a template because the active site only accommodates a single templating base during catalysis (9–12). Similarly, alkylating agents, such as methyl methanesulfonate, can methylate DNA bases, preventing accurate base pairing during DNA synthesis (13). Mitomycin C is a distinct type of bifunctional alkylating agent that can react with DNA, resulting in an interstrand cross-link (14). Interstrand DNA cross-links are particularly toxic because the two DNA strands cannot be separated by the replicative helicase or RNA polymerase, preventing DNA replication and transcription (15, 16). Another type of DNA damage is a break in the phosphodiester backbone caused by agents such as ionizing radiation and the naturally produced microbial peptides bleomycin and phleomycin (3). A break is toxic to cells because the DNA replication machinery depends on the integrity of the template for synthesis of the nascent strand (17, 18). For all types of DNA damage, the major impediment is the inability to access and replicate the information stored within the chromosome. DNA damage not only alters the coding information through mutagenesis or loss of information from deletions, but it can also slow chromosomal replication and segregation. Therefore, bacteria have evolved several different methods to detect incomplete chromosome segregation or problems with DNA integrity. Once such a condition is detected, cells halt the progression of cell division, affording the cell time to repair and then fully replicate its chromosome.

DNA DAMAGE ACTIVATES THE SOS RESPONSE IN BACTERIA

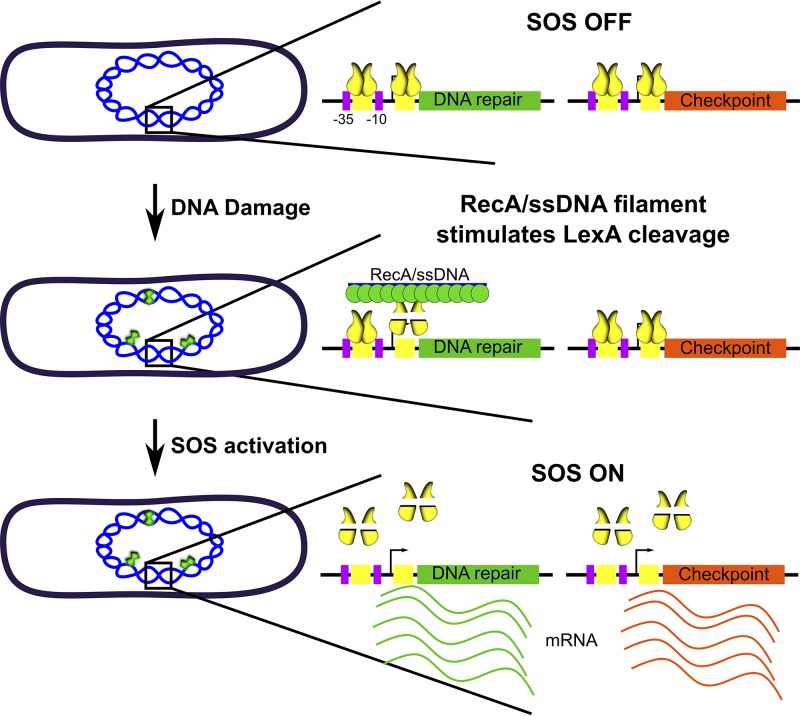

The SOS response is a highly conserved stress response pathway that is activated when bacteria encounter DNA damage (19–22). Activation of the SOS response results in increased transcription of genes important for DNA repair, DNA damage tolerance, and regulation of cell division (23–25). In addition, many mobile genetic elements and pathogenicity islands also sense problems with DNA replication through the SOS response (for a review, see reference 26). The collection of genes controlled by the SOS response is referred to as the SOS regulon. Proximal to the promoters of genes in the SOS regulon are DNA binding sites for the transcriptional repressor LexA (27–30). When bound to LexA binding sites, LexA prevents the transcription of genes under its control (31–34). Thus, activation of the SOS response requires the inactivation of LexA, resulting in activated gene transcription (Fig. 1).

FIG 1.

A model for activation of the bacterial SOS response. Activation of the SOS response begins with accumulation of ssDNA that occurs when high levels of DNA damage are present (green polygons). The ssDNA is subsequently coated with the protein RecA. The resulting RecA/ssDNA nucleoprotein filament stimulates the protease activity of the transcriptional repressor LexA (yellow protein). LexA undergoes autocleavage, resulting in derepression of the LexA regulon. Many of the genes in the LexA regulon are involved in DNA repair, DNA damage tolerance, and regulation of cell division, a process known as a DNA damage checkpoint. Yellow boxes represent LexA binding sites, and purple boxes represent −35 and −10 promoter sequences. This figure is adapted from reference 113.

Early genetic studies demonstrated that RecA is required for SOS activation (35). RecA catalyzes the pairing of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) to the complementary sequence in double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), resulting in the synapsis step of homologous recombination (36, 37). RecA is also required for LexA inactivation in vitro, suggesting that RecA functions as a protease responsible for LexA cleavage (38). Further characterization found that RecA bound to ssDNA acted as a coprotease stimulating the autoproteolytic activity of LexA (39) (Fig. 1). A unique feature of the SOS regulon is that a broad set of DNA lesions or problems with DNA replication evoke the formation of a RecA/ssDNA nucleoprotein filament, relaying a compromise in genome integrity activating the SOS response.

How does DNA damage lead to the accumulation of ssDNA in vivo? Treatment with a double-strand-break-inducing agent, such as bleomycin or ionizing radiation, leads to activation of the SOS response (40–42). The repair of double-stranded breaks occurs through homologous recombination (36, 43, 44), during which ssDNA is generated by the helicase/nuclease complex RecBCD in E. coli (17), AddAB in Bacillus subtilis (45), or AddnAB in Mycobacterium spp. (46). These enzymes bind and process double-stranded ends (45, 47) and generate a free 3′ tail onto which RecA is loaded (48–52). Thus, double-strand breaks result in the generation of a RecA/ssDNA nucleoprotein filament that can activate the SOS response. In B. subtilis, replication is required for the formation of a RecA-GFP focus and DNA damage is not sufficient (53). In E. coli, replication is not required to stimulate LexA cleavage following treatment with bleomycin (41). The generation of ssDNA following treatments that cause other types of DNA lesions, such as pyrimidine dimers from UV light, is less clear, though the process depends on DNA replication (41). One prominent model is that the stalling of the replicative DNA polymerase results in uncoupling of the replicative helicase from the replisome-generating excess ssDNA (54). A second model is that the replication machinery stalls at lesions such as pyrimidine dimers and will skip ahead, leaving a gap of ssDNA that provides a suitable substrate for RecA binding (54). A primer generated from an RNA transcript (55) or by primase (56) can allow DNA polymerase to advance beyond a DNA lesion on the leading strand, or this can occur through template switching (57, 58). The resulting ssDNA gap generated by DNA polymerase skipping ahead on the leading strand can be used as the substrate for loading RecA by the RecFOR complex (59). Indeed, activation of the SOS response following UV exposure is also dependent on the RecFOR proteins (60). Therefore, bacteria make use of a DNA repair intermediate to activate the expression of the genes important for DNA repair and the regulation of cell division (Fig. 1).

DNA replication and cell division are essential processes that must be coordinated to ensure that subsequent generations receive an accurate and complete copy of their genetic material. Under normal conditions, DNA replication and cell division occur at rates that allow replication and segregation of a complete chromosome to each daughter cell. When DNA damage forms and DNA replication is blocked, bacteria make use of multiple mechanisms to ensure that cell division is delayed, providing the cell with enough time for DNA repair to occur. These mechanisms include nucleoid occlusion, SOS-independent regulation of the divisome, and an SOS-dependent DNA damage checkpoint. Below, we discuss each of these mechanisms and how they regulate cytokinesis in bacteria.

SOS-INDEPENDENT REGULATION OF CELL DIVISION

Nucleoid occlusion.

A straightforward mechanism for preventing cell division prior to the completion of DNA replication is nucleoid occlusion (61, 62). We define the nucleoid as the supercoiled and compacted chromosome bound by numerous proteins. Nucleoid occlusion prevents the cell division machinery from operating in the same location as the nucleoid, requiring that chromosomal replication is near complete and chromosomes are segregated before cell division occurs (61, 62). Simply, the nucleoid will occlude the cell division machinery and prevent FtsZ ring assembly and constriction. In E. coli, nucleoid occlusion is accomplished by SlmA (61, 62). SlmA was identified using a genetic screen searching for genes that were important for cell division in the absence of the Min system (63). The Min system, composed of MinCDE, prevents cell division from occurring at the cell poles (64). Therefore, the logic was that mutants defective in both pathways responsible for cell division site selection would not survive. Indeed, mutants in slmA were isolated (63). Interestingly, the deletion of slmA alone did not change the frequency of cell division septum formation over the nucleoid; however, the deletion of both slmA and minCDE resulted in a drastic increase in septa forming over the nucleoid region (63). Importantly, when DNA replication was blocked, the deletion of slmA caused a marked increase in septum formation over nucleoids (63). Therefore, SlmA is required to prevent cell division from occurring at the same location as the nucleoid, thereby providing feedback inhibition to the cell division machinery based on the status of chromosomal replication and segregation.

Green fluorescent protein (GFP)-SlmA was shown to localize to the nucleoid, and if the helix-turn-helix domain was removed GFP-SlmA became diffusely cytosolic (63). SlmA, which belongs to the TetR family of transcriptional regulators, binds specific DNA motifs around the E. coli chromosome (65, 66). In addition to DNA binding activity, SlmA increases FtsZ protofilament breakdown (66). FtsZ is a tubulin homolog that forms a ring structure composed of numerous protofilaments at the site of cell division (67). SlmA bound to DNA is able to interact with the FtsZ C-terminal domain, causing disassembly of the protofilaments (66, 68). Recent experiments have shown that SlmA forms dynamic phase-separated droplets when bound to FtsZ (69). These results suggest that FtsZ-SlmA condensates regulate FtsZ by forming phase-separated droplets in vivo when SlmA is bound to sites on chromosomal DNA (69). By binding distinct chromosomal loci and simultaneously inhibiting FtsZ, SlmA provides a mechanism delaying cell division when replication and segregation of the chromosome are incomplete.

The bacterium B. subtilis also uses nucleoid occlusion to inhibit cell division, though the mechanism differs from the system discovered in E. coli. The nucleoid occlusion gene noc was also identified as a gene required in the absence of the Min system (70). When both Noc and the Min system were absent, FtsZ failed to form a distinct band at midcell (70). Further, when DNA replication was blocked in cells without Noc, division septa formed over the nucleoids, providing evidence that Noc also functions as a nucleoid occlusion factor. (70). Like SlmA, Noc is a sequence-specific DNA binding protein that binds to several distinct chromosomal loci (71). The N terminus of Noc is an amphipathic helix that interacts with the cell membrane (72). Noc binds the B. subtilis chromosome localizing to the inner leaflet of the cell membrane, where it is hypothesized to prevent the assembly of a complex of proteins necessary for cell division called the divisome (72).

Noc is not limited to B. subtilis or other rod-shaped bacteria. Noc has also been shown to inhibit cell division in the spherical Gram-positive bacterium Staphylococcus aureus (73). A synthetic lethal transposon-sequencing (Tn-seq) approach identified two genes that were lethal in a noc deletion (74). Follow-up analysis showed that mutations in the replication initiator dnaA suppressed the synthetic lethality of noc depletion in the double mutants (74). This analysis led to the finding that S. aureus Noc (SaNoc) negatively regulates DNA replication initiation by demonstrating that noc-deleted cells alone overinitiate and mutations in dnaA suppress the overinitiation phenotype (74). Therefore, in B. subtilis and S. aureus, Noc inhibits the divisome, providing a mechanism for the nucleoid to delay division until DNA replication is complete. In S. aureus, Noc has an additional regulatory role in preventing precocious initiation (74). In addition, a Noc-independent form of nucleoid occlusion following the arrest of DNA replication has been observed in B. subtilis (75). The mechanism and cellular factors responsible for this phenomenon are still unclear, requiring further experiments to determine the Noc-independent process (75).

FtsL depletion.

In addition to the nucleoid regulating cell division directly, the status of DNA replication provides feedback inhibition repressing expression of the cell division machinery. Transcriptomic studies of the SOS response in B. subtilis revealed that many genes were regulated by DNA damage independently of the SOS-activating protein RecA (76). Further analysis showed that several operons were regulated by the essential replication initiator protein DnaA and that a series of promoters for >50 genes (about 20 operons) had binding sites for DnaA known as DnaA boxes (76). One of the genes that is repressed following inhibition of DNA replication is ftsL (76). FtsL is an essential protein component of the divisome, and previous studies have shown that FtsL is a highly unstable protein in response to DNA damage (77–79). FtsL protein levels are normally controlled through regulated intramembrane proteolysis (RIP). FtsL contains a cytoplasmic recognition motif that is cleaved by RasP, an intramembrane zinc metalloprotease (79, 80). The DivIC protein stabilizes FtsL, preventing cleavage by RasP (81). Inhibition of DNA replication causes an increase in cell length independent of the SOS-dependent cell division inhibitor (see below); however, overexpression of FtsL resulted in shorter cells on average, indicating that a decrease in FtsL is responsible for delaying cell division in response to a block in DNA replication (76). Thus, it appears that following a block in DNA replication, DnaA inhibits cell division indirectly by repressing the expression of the unstable divisome protein FtsL.

SOS-DEPENDENT DNA DAMAGE CHECKPOINT

E. coli SulA.

Although the above-mentioned processes contribute to the regulation of cell division in response to DNA replication status, a prominent mechanism for cell division control in bacteria is the SOS-dependent DNA damage checkpoint. The bacterial DNA damage checkpoint was originally discovered in E. coli, long before the effects of treatment with UV light on DNA synthesis were understood (8, 82); E. coli cells were found to filament following exposure to UV light (83). More than 3 decades later, the existence of a specific cell division inhibitor was hypothesized (84). The hypothesis was that expression of the gene coding for the cell division inhibitor was normally repressed and that inhibition of DNA replication would result in derepression and accumulation of a protein that could prevent cell division (84). Although the mechanism of action varies between organisms, this hypothesis was upheld following investigation of the DNA damage checkpoint across many diverse bacterial species (a summary is shown in Table 1).

TABLE 1.

DNA damage-inducible cell division inhibitorsa

| Organism | Inhibitor | Inhibitor function | Target | Removal mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | SulA | 169-amino-acid cytoplasmic protein regulated by LexA | FtsZ | Degraded by Lon protease |

| B. subtilis | YneA | 105-amino-acid integral membrane protein, regulated by LexA, contains an N-terminal TM and C-terminal LysM domain | Unknown | Cleaved by CtpA and DdcP |

| S. aureus | SosA | 77-amino-acid integral membrane protein contains an N-terminal TM domain | Unknown | Cleaved by CtpA |

| M. tuberculosis | ChiZ (Rv2719c) | 165-amino-acid integral membrane protein contains a TM domain toward the middle of the protein and LysM domain near the C terminus; expression is regulated by DNA damage | Peptidoglycan hydrolysis and/or interaction with FtsI/Q | Unknown |

| C. glutamicum | DivS | 140-amino-acid integral membrane protein with C-terminal TM domain | Unknown | Unknown |

| C. crescentus | SidA | 29-amino-acid TM protein regulated by LexA | FtsI/N/W | Unknown |

| C. crescentus | DidA | 71-amino-acid integral membrane protein; contains TM domain in the middle portion of the protein; regulated by transcription factor DriD | FtsI/N/W | Unknown |

Cell filamentation characterized by recA mutants (tif) causing SOS induction at elevated temperatures was exacerbated in cells with a lon mutation (85). Suppressors were isolated called sfiA because the mutations suppressed filamentation of an E. coli tif and lon double mutant (85). A subsequent study determined that sfiA mutations mapped to the same gene as sulA, which were so named because they suppressed DNA damage sensitivity of lon mutants (86, 87). To test if sulA was controlled by exogenous DNA damage treatments, a lacZ reporter at the sulA locus was monitored following exposure to several types of DNA damage, which verified that sulA expression was indeed DNA damage inducible (88). The promoter of sulA contains a binding site for the repressor LexA (89), and binding of LexA at the promoter of sulA repressed transcription (90). Thus, activation of the SOS response, and therefore, inactivation of LexA, result in high levels of sulA expression.

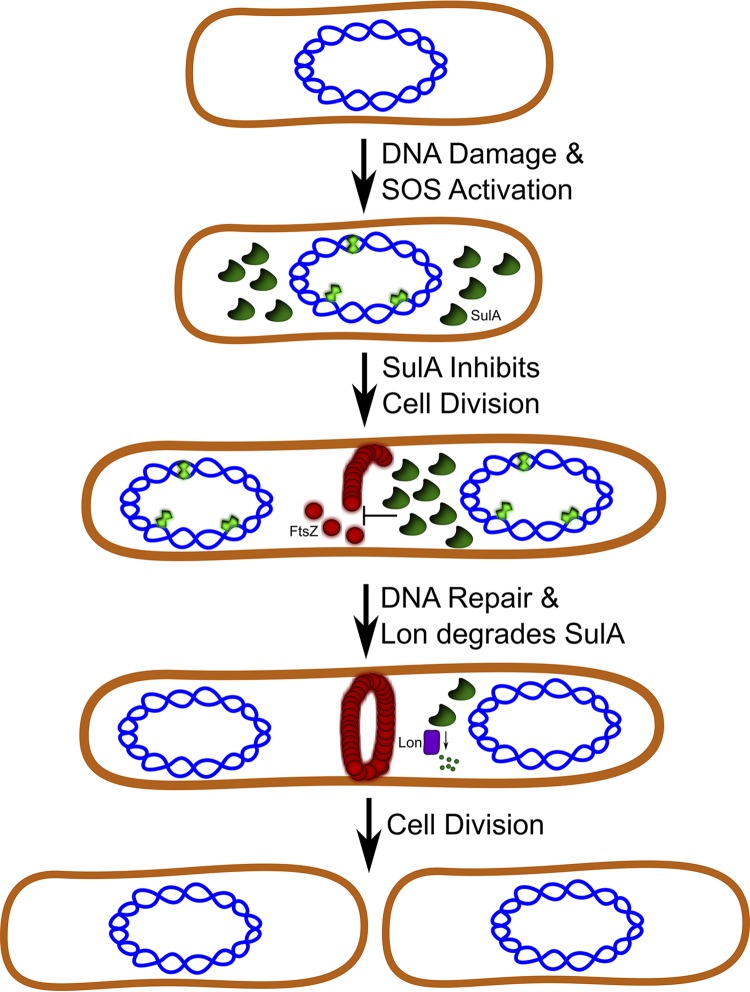

Other methods of increasing SulA protein levels, including overexpression in the absence of DNA damage or deletion of lon, lead to cell filamentation (91–93). One of the early steps in cell division is the assembly of the FtsZ ring at the future division site (67). Overexpression of SulA prevents formation of the FtsZ ring in vivo (94). One of the original mutations that suppressed DNA damage-induced filamentation, sfiB (or sulB), mapped to the ftsZ locus. Further studies demonstrated that mutations in ftsZ could suppress filamentation resulting from SulA accumulation, suggesting that FtsZ could be the direct target of SulA (95, 96). In addition, overexpression of FtsZ rescued the inhibition of cell division following UV treatment in lon mutants, further establishing a link between SulA function and FtsZ (97). An interaction between SulA and FtsZ was detected using a yeast two-hybrid assay (98). Moreover, several mutations in sulA that abolished its ability to inhibit cell division also abolished the interaction with FtsZ, and mutations in ftsZ that are not susceptible to SulA overexpression also abolished their interaction (98). Experiments using an FtsZ polymerization assay in vitro demonstrated that SulA could directly inhibit FtsZ polymerization (96, 99). Mutations in SulA that cannot block cell division failed to inhibit FtsZ polymerization, whereas mutations in FtsZ that are refractory to SulA accumulation were insensitive to SulA in vitro (96, 99). A detailed kinetic analysis of SulA inhibition of FtsZ polymerization revealed that SulA increased the concentration of FtsZ required for polymerization and that SulA interaction with FtsZ functions by sequestering FtsZ monomers (100). Therefore, increased SulA production during SOS results in temporary inhibition of FtsZ ring assembly, thereby delaying cell division until the SOS response is repressed by LexA and SulA is degraded by Lon (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

DNA damage-dependent cell cycle checkpoint in E coli. When E. coli cells encounter DNA damage (green polygons), the SOS response is activated, and the cell division inhibitor SulA is overexpressed (dark green). SulA prevents cell division by inhibiting assembly of the FtsZ ring (red circles). Following DNA repair and SOS termination, SulA is degraded by Lon protease, allowing cell division to proceed. This figure is adapted from reference 113.

The accumulation of SulA is reversed by Lon protease activity. As mentioned above, sulA was originally identified by isolation of a mutation that suppressed DNA damage sensitivity in a lon mutant (86, 87). The Lon protein was later determined to be an ATP-dependent protease (101), leading to the hypothesis that SulA could be a substrate of Lon. Indeed, SulA was found to be highly unstable in wild-type cells; however, in a lon mutant, SulA was stabilized, indicating that SulA stability is regulated by Lon (92). Intriguingly, despite a significant increase in SulA stability in lon mutants, pulse-chase labeling experiments demonstrated that SulA was still susceptible to proteolysis in vivo (92). Subsequent studies identified a second ATP-dependent protease, ClpYQ, that reduces the stability of SulA in vivo and degrades SulA in vitro (102–104). Although the evidence that Lon protease activity regulated SulA stability in vivo was convincing, it was not yet known if SulA was a direct substrate of Lon protease. Studies using purified Lon protease demonstrated that SulA was indeed a direct substrate (105). Thus, Lon protease provides recovery from the DNA damage checkpoint imposed by SulA, thereby allowing for cell division to proceed (Fig. 2).

SMALL MEMBRANE-BOUND SOS-INDUCED CELL DIVISION INHIBITORS

The identification of a DNA damage checkpoint in bacteria was an important conceptual advance; however, extrapolation of the mechanism beyond E. coli has proven challenging. The cell division inhibitor SulA is not well conserved among bacteria (106, 107). Nonetheless, treatment with DNA-damaging agents does lead to cell filamentation in B. subtilis and many other bacteria (108). The SOS response is conserved in B. subtilis; however, sulA is not (106). Therefore, it was unclear what gene product(s) acted as the inhibitor in B. subtilis and other Gram-positive bacteria. To identify the gene coding for the cell division inhibitor, a microarray was performed using wild-type and lexA mutant cells, reasoning that if there is an SOS-dependent cell division inhibitor, it will be highly transcribed in cells lacking the LexA repressor (109). One of the highly transcribed genes in the lexA mutant was yneA, and Northern blot analysis confirmed that the yneA operon was induced in the absence of functional LexA (109). The yneA operon is located adjacent to lexA in the B. subtilis genome, and inspection of the promoter region of yneA revealed two binding sites for LexA, providing evidence that LexA regulates yneA expression directly (109). Indeed, purified LexA can bind to the yneA promoter region (29).

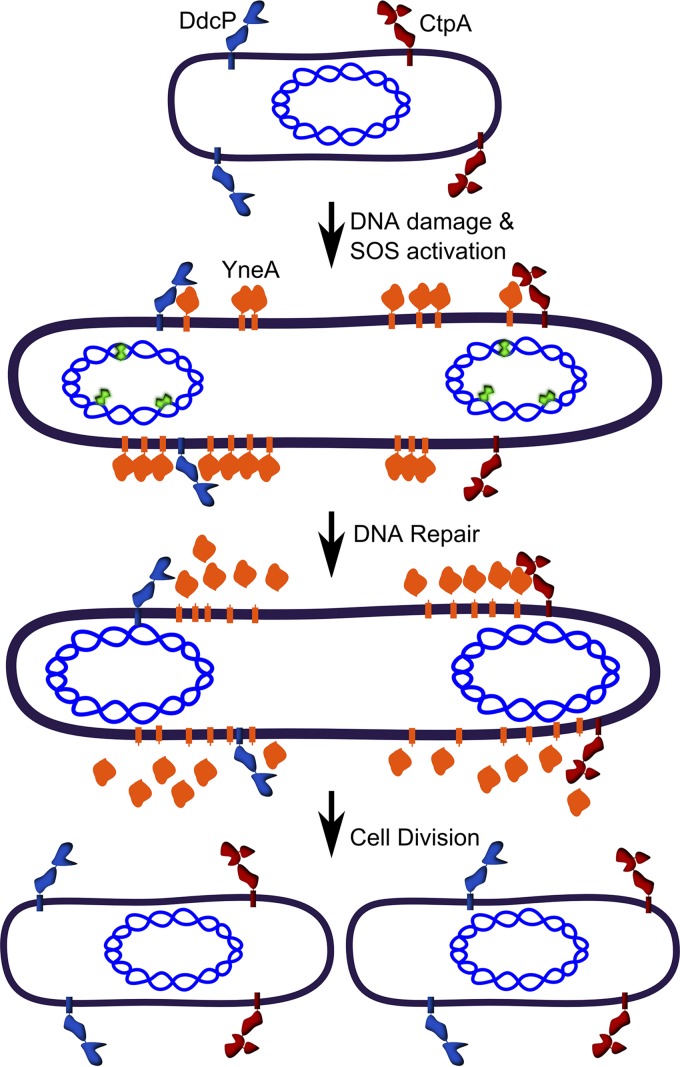

Examination of lexA mutant cells showed that they were significantly longer relative to the wild-type strain, indicating that cell division is inhibited in the lexA mutant (109). Deletion of the yneA operon returned the cell length to normal in the lexA mutant strain, suggesting that yneA is necessary for inhibiting cell division (109). To test if expression of yneA was sufficient for increased cell length, yneA was placed under the control of an isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible promoter, and cells were found to increase in length following the addition of IPTG (109). Cell elongation following DNA damage was mostly dependent on yneA, suggesting that YneA is the SOS-induced cell division inhibitor (109). Thus, yneA expression is induced by DNA damage, and inhibition of cell division is dependent on yneA (Fig. 3).

FIG 3.

DNA damage-dependent cell cycle checkpoint in B. subtilis. When B. subtilis cells encounter DNA damage (green polygons), the SOS response is activated, and the cell division inhibitor YneA is expressed. YneA prevents cell division through an unknown mechanism. CtpA (maroon) and DdcP (blue) cleave YneA, deactivating the DNA damage checkpoint. This figure is adapted from reference 113.

The mechanism of YneA-dependent inhibition of cell division is still not understood. Given that SulA prevents FtsZ ring assembly (94), it was hypothesized that YneA may also inhibit FtsZ (109). Visualization of FtsZ following YneA expression showed that FtsZ rings still form at midcell, suggesting that YneA inhibits a different target (110). YneA is a small protein containing an N-terminal transmembrane domain and a C-terminal LysM domain (109, 110). LysM domains often interact with the peptidoglycan cell wall (111). Expression of YneA causes increased cell length; however, following a shift to a medium that does not induce YneA expression, cells rapidly divide (110). These experiments suggest that YneA reversibly inhibits cell division. Alanine scanning mutagenesis of the alpha-helix transmembrane domain demonstrated that several residues clustering to a single face of the alpha-helix were critical for YneA function in vivo, suggesting that YneA may interact with one of the proteins with a transmembrane domain that functions as part of the divisome or the residues are important for some other function of the transmembrane domain (110). The transmembrane domain is necessary, though not sufficient, for YneA to inhibit cell division (110). Interestingly, Mo and Burkholder found that YneA was cleaved, releasing the YneA C terminus from the transmembrane domain into the culture medium (110). Mutation of the putative signal peptide cleavage site did not appreciably decrease YneA processing, though mutation to a canonical signal peptide cleavage site resulted in increased YneA processing (110). Further, a mutation at the C terminus of YneA was found to increase YneA stability (110). An analysis of cell elongation using these YneA variants demonstrated that YneA was processed more quickly resulting in shorter cells, whereas the stabilizing mutations resulted in increased cell length, suggesting that full-length YneA is the active form of the protein (110). Together, these studies led to a model wherein YneA is the SOS-dependent cell division inhibitor that establishes the DNA damage checkpoint, and degradation of YneA by an unknown protease allows for cells to resume cell division (Fig. 3).

YneA was found to be degraded by two previously uncharacterized proteases in B. subtilis. YlbL, now named DNA damage checkpoint protease (DdcP), and C-terminal processing protease A (CtpA) were identified through a genome-wide Tn-seq screen to render cells sensitive to a broad range of DNA-damaging agents (112). DdcP and CtpA have N-terminal transmembrane domains, followed by Lon and S41 peptidase domains at their C termini, respectively (112). This work showed that expression of YneA caused considerable growth interference in cells lacking ddcP and/or ctpA (112). Genetic experiments showed that ectopic expression of either ddcP or ctpA could complement the loss of the other, including the double mutant, which demonstrates overlapping functions for DdcP and CtpA (112). YneA protein levels accumulate in the single- or double-protease-deletion strains, and CtpA was shown to directly cleave YneA in a purified system (112). Because the proteases are not damage inducible, this work invokes a model where the proteases are constitutively present in the plasma membrane and cleave YneA when it is produced. Under conditions of SOS induction, YneA levels increase and saturate the ability of the proteases to cleave YneA, causing inhibition of cell division. After DNA repair is complete and LexA represses YneA expression, DdcP and CtpA cleave and clear the remaining YneA, allowing cell division to resume (Fig. 3 and Table 1) (112). The same Tn-seq screen that discovered DdcP and CtpA also found a cytoplasmic protein DdcA that negatively regulates YneA helping to set the threshold of YneA necessary to induce the checkpoint (113). The discovery of DdcA strengthens the evidence that bacterial cells have multiple mechanisms to ensure that enough DNA damage must be detected before engaging the checkpoint.

The human pathogen Staphylococcus aureus contains the sosA gene, which, like YneA in B. subtilis, is divergently transcribed from the lexA promoter (114). SosA is composed of 77 amino acids containing an N-terminal transmembrane domain but lacking a LysM domain (114). SosA expression is induced by DNA damage, and SosA is the SOS-induced cell division inhibitor in S. aureus (114). Like YneA, SosA accumulates in cells with a deletion in the protease gene ctpA (114). In S. aureus, SosA appears to be cleaved by a single protease, and a cytoplasmic negative regulator similar to DdcA has not been identified. Collectively, these results indicate that membrane-bound SOS-induced cell division inhibitors are cleaved by membrane-bound proteases in at least two Gram-positive bacteria.

As other investigations identified the DNA damage checkpoints in bacteria, it became clear that the mechanism discovered in E. coli was not representative of other species (107, 109, 114–117). In fact, the use of a small integral membrane-bound protein similar to YneA in B. subtilis appears to be the more widespread mechanism. Identification of additional cell division inhibitors has proved challenging because homology searches have failed to identify homologs in distantly related bacterial species, requiring empirical identification (116). The differences in DNA damage checkpoint mechanisms likely reflect the diversity of bacterial lifestyles, given that the need to delay cell division in response to DNA damage will depend on growth rate, the frequency and severity of DNA damage encountered, and the DNA repair capability of each organism.

The cell division inhibitor Rv2719c was identified by microarray as an SOS-induced gene in Mycobacterium tuberculosis (118, 119). Rv2719c is located adjacent to the LexA gene, providing the same gene structure as that for YneA and SosA (120). Many of the DNA damage-inducible genes in M. tuberculosis are induced independently of RecA through an unknown mechanism (118). Rv2719c is DNA damage inducible, and its regulation is also independent of RecA (119). A mutational analysis identified a promoter upstream of the LexA binding sites that is important for reporter expression, indicating that Rv2719c can be regulated from the upstream promoter, allowing transcription through the LexA binding sites even when LexA is intact (120). Further analysis of Rv2719c expression and cell length demonstrated that increased expression is correlated with increased cell length, and specific overexpression of Rv2719c is sufficient to cause an increase in cell length (115). Increased expression of Rv2719c does not appear to affect FtsZ, which is similar to YneA and SosA (115). The Rv2719c protein contains a transmembrane domain and a LysM domain similar to YneA. Purified Rv2719c was found to possess cell wall hydrolase activity in vitro, and expression of a GFP-Rv2719c fusion showed localization similar to nascent peptidoglycan synthesis, suggesting that inhibitor activity may be exerted on the cell wall (115). Overall, Rv2719c is a DNA damage-inducible cell division inhibitor that may act on the cell wall or cell wall synthesis machinery to establish the DNA damage checkpoint in mycobacteria.

The observation that SOS-induced cell division inhibitors are located adjacent to lexA in the genomes of their respective organisms and that they are transcribed divergently is a common theme that holds true for the cell division inhibitor in Corynebacterium glutamicum (117). The divS gene in C. glutamicum is located adjacent to lexA, and divS expression is dependent on RecA (117). Cell elongation following treatment with DNA-damaging agents is dependent on recA and divS (117). An analysis of the promoter uncovered LexA binding sites, and LexA binds to the promoter region in vitro (121). Overexpression of DivS resulted in increased cell length, indicating that increased DivS expression is sufficient to inhibit cell division (117). The DivS protein has three domains, an N-terminal domain, a transmembrane domain, and a C-terminal domain (Table 1). The N terminus was found to be dispensable for cell division inhibition, whereas nine amino acids at the C terminus were required (117). The sites of nascent peptidoglycan synthesis and formation of FtsZ rings were found to decrease following DNA damage, requiring DivS (117). Overexpression of DivS also resulted in decreased sites of nascent peptidoglycan synthesis, though the exact mechanism by which DivS activates the DNA damage checkpoint and prevents cell division is unclear. It is also unclear how DivS inhibition is relieved, although a proteolysis-dependent mechanism has been shown for all other bacterial systems where the mechanism is known (Table 1) (112, 114).

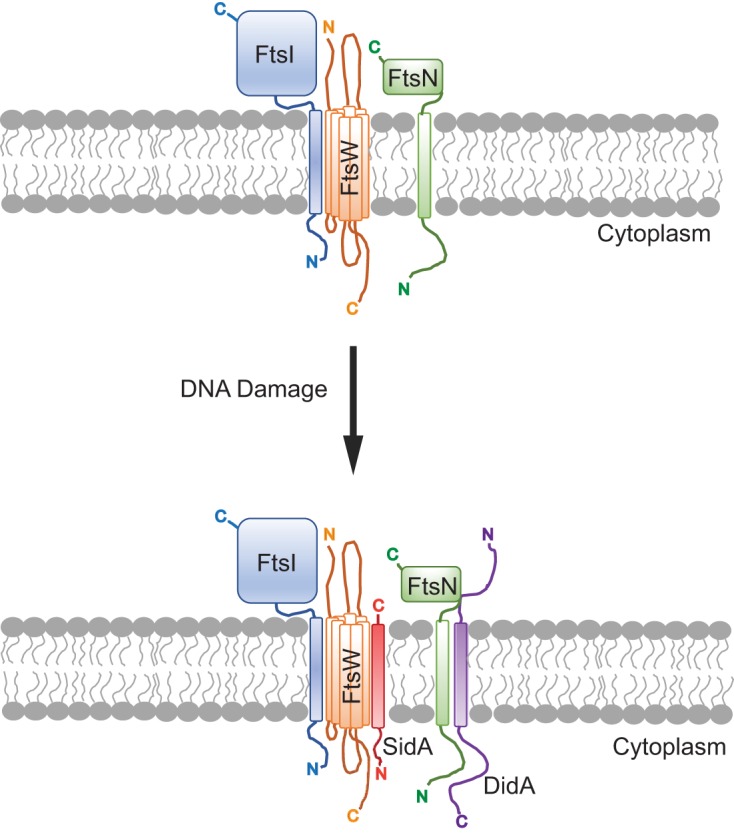

The discovery of an SOS-inducible cell division inhibitor in Caulobacter crescentus required the use of microarrays because the inhibitor is not located near lexA in the genome (107). Expression of the gene encoding the cell division inhibitor, sidA, increased rapidly following mitomycin C (MMC) or UV light, and inspection of the promoter revealed putative LexA binding sites (107). The deletion of lexA resulted in severe cell elongation that could be rescued by the deletion of sidA, and overexpression of sidA resulted in significant cell elongation (107), demonstrating that SidA overexpression is sufficient to inhibit cell division (107). SidA is a 29-amino-acid protein composed of a single transmembrane domain (Fig. 4 and Table 1) (107). A genetic suppressor screen identified mutations in ftsW and ftsI, genes coding for two essential components of the divisome involved in peptidoglycan synthesis at the division septum, which suppress cell division inhibition from overexpressing SidA (107). SidA was found to interact with FtsW in a bacterial two-hybrid assay (107). Evidence was presented suggesting that SidA can form a complex with FtsW and FtsI, indicating that the interaction of SidA with FtsW does not occlude binding of FtsI (107). SidA also did not alter the localization or recruitment of these divisome proteins to midcell, and experiments using fluorescently labeled vancomycin did not find a defect in septal peptidoglycan synthesis following SidA overexpression (107). Together, these data support a model wherein SidA is an SOS-induced cell division inhibitor that inhibits the activity of the divisome to establish the DNA damage checkpoint. We suggest that the membrane-bound SOS-induced cell division inhibitors, including SidA, are likely to be inactivated through a protease-dependent mechanism, as demonstrated for YneA and SosA (112, 114).

FIG 4.

Model for SidA and DidA inhibition of cell division in Caulobacter spp. following DNA damage. SidA is regulated by LexA, and DidA is regulated by the transcription factor DriD. Following DNA damage, SidA (red) and DidA (purple) are expressed and interact with FtsW and FtsN, respectively (116). These interactions are hypothesized to cause the FtsW/I/N complex to assume an inactive state (116). The inhibition of FtsW/I/N prevents cytokinesis. This figure was adapted from PLoS Biology (116). The orientation of integral membrane proteins as well as membrane-spanning regions were predicted using Protter (122). C, C terminus; N, N terminus.

DNA DAMAGE-DEPENDENT SOS-INDEPENDENT TRANSCRIPTIONAL REGULATOR

A subsequent study in C. crescentus identified a second SOS-independent cell division inhibitor, DidA, whose expression is DNA damage inducible, and DidA acts by inhibiting the divisome (116). DidA is also a small protein containing a single transmembrane domain (Fig. 4). The authors identified a new transcription factor, DriD, that positively regulates didA expression. Interestingly, DriD is activated via a DNA damage-dependent mechanism, though it is still unclear how DNA damage activates DriD (116). Therefore, in C. crescentus, there are two cell division inhibitors that interact with the divisome to prevent cell division following DNA damage, establishing the checkpoint. This finding is important because it suggests that other bacteria may use transcriptional activators induced by DNA damage to upregulate the expression of cell division inhibitors. DNA damage-activated transcription factors, like DriD, present an attractive mechanism for bacteria that lack LexA to control the expression of their cognate cell division inhibitor and possibly other genes canonically regulated by LexA. The identification of DriD also presents the possibility that translesion DNA polymerases involved in DNA damage-dependent mutagenesis could be regulated by a DriD-type transcriptional activator in bacteria that lack the classically defined LexA-dependent SOS response. Future experiments could be directed toward understanding how the DNA damage signal is transduced to DriD and if organisms that lack LexA regulate their DDR through activation of a transcription factor such as DriD.

CONCLUSIONS

Bacterial cells have evolved several methods to prevent cell division when chromosome replication is incomplete or genome instability occurs. Although inhibition of FtsZ by the cytoplasmic SulA protein of E. coli has served as the prototypical DNA damage-inducible cell division inhibitor, we now know that most bacteria employ integral membrane-bound proteins to enforce the DNA damage checkpoint (107, 109, 114–117). Despite recent advances, the mechanism(s) of establishing the DNA damage checkpoint by membrane-bound cell division inhibitors remains unclear. Future work will be necessary to identify the targets for most of the inhibitors, as well as the mechanism of inhibition exerted by SidA and DidA on FtsW/I/N. Nonetheless, it is notable that regardless of the type of inhibitor used, deactivation of the checkpoint involves proteolysis of the inhibitor. This suggests that even though bacterial species have evolved different mechanisms for checkpoint enforcement, they arrived at a common mechanism for checkpoint deactivation, ensuring rapid recovery and completion of cell division.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the anonymous referees and the editor for comments on our manuscript.

Research in the laboratory of L.A.S. is currently supported by National Institutes of Health grant R35 GM131772. P.E.B. was supported by a predoctoral fellowship from the National Science Foundation (grant DGE1256260) and a fellowship from the Rackham Graduate School at the University of Michigan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang JD, Levin PA. 2009. Metabolism, cell growth and the bacterial cell cycle. Nat Rev Microbiol 7:822–827. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedberg EC, Walker GC, Siede W, Wood RD, Schultz RA, Ellenberger T. 2006. DNA repair and mutagenesis, 2nd ed. ASM Press, Washington, DC, p 463–497. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chatterjee N, Walker GC. 2017. Mechanisms of DNA damage, repair, and mutagenesis. Environ Mol Mutagen 58:235–263. doi: 10.1002/em.22087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ciccia A, Elledge SJ. 2010. The DNA damage response: making it safe to play with knives. Mol Cell 40:179–204. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanpain C, Mohrin M, Sotiropoulou PA, Passegue E. 2011. DNA-damage response in tissue-specific and cancer stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 8:16–29. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demain AL, Vaishnav P. 2011. Natural products for cancer chemotherapy. Microb Biotechnol 4:687–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2010.00221.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beukers R, Berends W. 1960. Isolation and identification of the irradiation product of thymine. Biochim Biophys Acta 41:550–551. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(60)90063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Setlow RB, Swenson PA, Carrier WL. 1963. Thymine dimers and inhibition of DNA synthesis by ultraviolet irradiation of cells. Science 142:1464–1466. doi: 10.1126/science.142.3598.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ling H, Boudsocq F, Plosky BS, Woodgate R, Yang W. 2003. Replication of a cis-syn thymine dimer at atomic resolution. Nature 424:1083–1087. doi: 10.1038/nature01919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doublie S, Tabor S, Long AM, Richardson CC, Ellenberger T. 1998. Crystal structure of a bacteriophage T7 DNA replication complex at 2.2 Å resolution. Nature 391:251–258. doi: 10.1038/34593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiefer JR, Mao C, Braman JC, Beese LS. 1998. Visualizing DNA replication in a catalytically active Bacillus DNA polymerase crystal. Nature 391:304–307. doi: 10.1038/34693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson RE, Prakash L, Prakash S. 2005. Distinct mechanisms of cis-syn thymine dimer bypass by Dpo4 and DNA polymerase eta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:12359–12364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504380102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sedgwick B. 2004. Repairing DNA-methylation damage. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5:148–157. doi: 10.1038/nrm1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iyer VN, Szybalski W. 1963. A molecular mechanism of mitomycin action: linking of complementary DNA strands. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 50:355–362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.50.2.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noll DM, Mason TM, Miller PS. 2006. Formation and repair of interstrand cross-links in DNA. Chem Rev 106:277–301. doi: 10.1021/cr040478b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dronkert ML, Kanaar R. 2001. Repair of DNA interstrand cross-links. Mutat Res 486:217–247. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(01)00092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dillingham MS, Kowalczykowski SC. 2008. RecBCD enzyme and the repair of double-stranded DNA breaks. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 72:642–671, table of contents. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00020-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michel B, Sinha AK, Leach D. 2018. Replication fork breakage and restart in Escherichia coli. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 82:e00013-18. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00013-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erill I, Campoy S, Barbe J. 2007. Aeons of distress: an evolutionary perspective on the bacterial SOS response. FEMS Microbiol Rev 31:637–656. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kreuzer KN. 2013. DNA damage responses in prokaryotes: regulating gene expression, modulating growth patterns, and manipulating replication forks. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 5:a012674. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Little JW, Mount DW. 1982. The SOS regulatory system of Escherichia coli. Cell 29:11–22. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simmons LA, Foti JJ, Cohen SE, Walker GC. 2008. The SOS regulatory network. EcoSal Plus 2008. doi: 10.1128/ecosalplus.5.4.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kenyon CJ, Walker GC. 1980. DNA-damaging agents stimulate gene expression at specific loci in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 77:2819–2823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.5.2819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kenyon CJ, Walker GC. 1981. Expression of the E. coli uvrA gene is inducible. Nature 289:808–810. doi: 10.1038/289808a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Courcelle J, Khodursky A, Peter B, Brown PO, Hanawalt PC. 2001. Comparative gene expression profiles following UV exposure in wild-type and SOS-deficient Escherichia coli. Genetics 158:41–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fornelos N, Browning DF, Butala M. 2016. The use and abuse of LexA by mobile genetic elements. Trends Microbiol 24:391–401. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schnarr M, Oertel-Buchheit P, Kazmaier M, Granger-Schnarr M. 1991. DNA binding properties of the LexA repressor. Biochimie 73:423–431. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(91)90109-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wade JT, Reppas NB, Church GM, Struhl K. 2005. Genomic analysis of LexA binding reveals the permissive nature of the Escherichia coli genome and identifies unconventional target sites. Genes Dev 19:2619–2630. doi: 10.1101/gad.1355605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Au N, Kuester-Schoeck E, Mandava V, Bothwell LE, Canny SP, Chachu K, Colavito SA, Fuller SN, Groban ES, Hensley LA, O'Brien TC, Shah A, Tierney JT, Tomm LL, O'Gara TM, Goranov AI, Grossman AD, Lovett CM. 2005. Genetic composition of the Bacillus subtilis SOS system. J Bacteriol 187:7655–7666. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.22.7655-7666.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewis LK, Harlow GR, Gregg-Jolly LA, Mount DW. 1994. Identification of high affinity binding sites for LexA which define new DNA damage-inducible genes in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol 241:507–523. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brent R, Ptashne M. 1981. Mechanism of action of the lexA gene product. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 78:4204–4208. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.7.4204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brent R, Ptashne M. 1980. The lexA gene product represses its own promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 77:1932–1936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.4.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Little JW, Mount DW, Yanisch-Perron CR. 1981. Purified lexA protein is a repressor of the recA and lexA genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 78:4199–4203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.7.4199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sancar A, Sancar GB, Rupp WD, Little JW, Mount DW. 1982. LexA protein inhibits transcription of the E. coli uvrA gene in vitro. Nature 298:96–98. doi: 10.1038/298096a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Witkin EM. 1991. RecA protein in the SOS response: milestones and mysteries. Biochimie 73:133–141. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(91)90196-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bell JC, Kowalczykowski SC. 2016. RecA: regulation and mechanism of a molecular search engine. Trends Biochem Sci 41:491–507. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moreau PL. 1985. Role of Escherichia coli RecA protein in SOS induction and post-replication repair. Biochimie 67:353–356. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(85)80079-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Little JW, Edmiston SH, Pacelli LZ, Mount DW. 1980. Cleavage of the Escherichia coli lexA protein by the recA protease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 77:3225–3229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.6.3225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Little JW. 1984. Autodigestion of lexA and phage lambda repressors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 81:1375–1379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.5.1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simmons LA, Goranov AI, Kobayashi H, Davies BW, Yuan DS, Grossman AD, Walker GC. 2009. Comparison of responses to double-strand breaks between Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis reveals different requirements for SOS induction. J Bacteriol 191:1152–1161. doi: 10.1128/JB.01292-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sassanfar M, Roberts JW. 1990. Nature of the SOS-inducing signal in Escherichia coli. The involvement of DNA replication. J Mol Biol 212:79–96. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90306-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goranov AI, Kuester-Schoeck E, Wang JD, Grossman AD. 2006. Characterization of the global transcriptional responses to different types of DNA damage and disruption of replication in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 188:5595–5605. doi: 10.1128/JB.00342-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ayora S, Carrasco B, Cardenas PP, Cesar CE, Canas C, Yadav T, Marchisone C, Alonso JC. 2011. Double-strand break repair in bacteria: a view from Bacillus subtilis. FEMS Microbiol Rev 35:1055–1081. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bell JC, Kowalczykowski SC. 2016. Mechanics and single-molecule interrogation of DNA recombination. Annu Rev Biochem 85:193–226. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-034352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chédin F, Ehrlich SD, Kowalczykowski SC. 2000. The Bacillus subtilis AddAB helicase/nuclease is regulated by its cognate Chi sequence in vitro. J Mol Biol 298:7–20. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gupta R, Barkan D, Redelman-Sidi G, Shuman S, Glickman MS. 2011. Mycobacteria exploit three genetically distinct DNA double-strand break repair pathways. Mol Microbiol 79:316–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07463.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taylor AF, Smith GR. 1985. Substrate specificity of the DNA unwinding activity of the RecBC enzyme of Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol 185:431–443. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90414-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anderson DG, Kowalczykowski SC. 1997. The translocating RecBCD enzyme stimulates recombination by directing RecA protein onto ssDNA in a chi-regulated manner. Cell 90:77–86. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80315-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Churchill JJ, Anderson DG, Kowalczykowski SC. 1999. The RecBC enzyme loads RecA protein onto ssDNA asymmetrically and independently of chi, resulting in constitutive recombination activation. Genes Dev 13:901–911. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.7.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Churchill JJ, Kowalczykowski SC. 2000. Identification of the RecA protein-loading domain of RecBCD enzyme. J Mol Biol 297:537–542. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dixon DA, Kowalczykowski SC. 1993. The recombination hotspot χ is a regulatory sequence that acts by attenuating the nuclease activity of the E. coli RecBCD enzyme. Cell 73:87–96. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90162-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taylor AF, Schultz DW, Ponticelli AS, Smith GR. 1985. RecBC enzyme nicking at Chi sites during DNA unwinding: location and orientation-dependence of the cutting. Cell 41:153–163. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Simmons LA, Grossman AD, Walker GC. 2007. Replication is required for the RecA localization response to DNA damage in Bacillus subtilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:1360–1365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607123104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Indiani C, O’Donnell M. 2013. A proposal: source of single strand DNA that elicits the SOS response. Front Biosci 18:312–323. doi: 10.2741/4102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pomerantz RT, O'Donnell M. 2008. The replisome uses mRNA as a primer after colliding with RNA polymerase. Nature 456:762–766. doi: 10.1038/nature07527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Heller RC, Marians KJ. 2006. Replication fork reactivation downstream of a blocked nascent leading strand. Nature 439:557–562. doi: 10.1038/nature04329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dutra BE, Lovett ST. 2006. Cis and trans-acting effects on a mutational hotspot involving a replication template switch. J Mol Biol 356:300–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Laranjo LT, Klaric JA, Pearlman LR, Lovett ST. 2018. Stimulation of replication template-switching by DNA-protein crosslinks. Genes (Basel) 10:E14. doi: 10.3390/genes10010014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Morimatsu K, Kowalczykowski SC. 2003. RecFOR proteins load RecA protein onto gapped DNA to accelerate DNA strand exchange: a universal step of recombinational repair. Mol Cell 11:1337–1347. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00188-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ivancic-Bace I, Vlasic I, Salaj-Smic E, Brcic-Kostic K. 2006. Genetic evidence for the requirement of RecA loading activity in SOS induction after UV irradiation in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 188:5024–5032. doi: 10.1128/JB.00130-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Adams DW, Wu LJ, Errington J. 2014. Cell cycle regulation by the bacterial nucleoid. Curr Opin Microbiol 22:94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2014.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wu LJ, Errington J. 2011. Nucleoid occlusion and bacterial cell division. Nat Rev Microbiol 10:8–12. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bernhardt TG, de Boer PA. 2005. SlmA, a nucleoid-associated, FtsZ binding protein required for blocking septal ring assembly over Chromosomes in E. coli. Mol Cell 18:555–564. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rowlett VW, Margolin W. 2013. The bacterial Min system. Curr Biol 23:R553–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tonthat NK, Arold ST, Pickering BF, Van Dyke MW, Liang S, Lu Y, Beuria TK, Margolin W, Schumacher MA. 2011. Molecular mechanism by which the nucleoid occlusion factor, SlmA, keeps cytokinesis in check. EMBO J 30:154–164. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cho H, McManus HR, Dove SL, Bernhardt TG. 2011. Nucleoid occlusion factor SlmA is a DNA-activated FtsZ polymerization antagonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:3773–3778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018674108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Adams DW, Errington J. 2009. Bacterial cell division: assembly, maintenance and disassembly of the Z ring. Nat Rev Microbiol 7:642–653. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schumacher MA, Zeng W. 2016. Structures of the nucleoid occlusion protein SlmA bound to DNA and the C-terminal domain of the cytoskeletal protein FtsZ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:4988–4993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1602327113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Monterroso B, Zorrilla S, Sobrinos‐Sanguino M, Robles‐Ramos MA, López‐Álvarez M, Margolin W, Keating CD, Rivas G. 2019. Bacterial FtsZ protein forms phase-separated condensates with its nucleoid-associated inhibitor SlmA. EMBO Rep 20:e45946. doi: 10.15252/embr.201845946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wu LJ, Errington J. 2004. Coordination of cell division and chromosome segregation by a nucleoid occlusion protein in Bacillus subtilis. Cell 117:915–925. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu LJ, Ishikawa S, Kawai Y, Oshima T, Ogasawara N, Errington J. 2009. Noc protein binds to specific DNA sequences to coordinate cell division with chromosome segregation. EMBO J 28:1940–1952. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Adams DW, Wu LJ, Errington J. 2015. Nucleoid occlusion protein Noc recruits DNA to the bacterial cell membrane. EMBO J 34:491–501. doi: 10.15252/embj.201490177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Veiga H, Jorge AM, Pinho MG. 2011. Absence of nucleoid occlusion effector Noc impairs formation of orthogonal FtsZ rings during Staphylococcus aureus cell division. Mol Microbiol 80:1366–1380. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pang T, Wang X, Lim HC, Bernhardt TG, Rudner DZ. 2017. The nucleoid occlusion factor Noc controls DNA replication initiation in Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS Genet 13:e1006908. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bernard R, Marquis KA, Rudner DZ. 2010. Nucleoid occlusion prevents cell division during replication fork arrest in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol 78:866–882. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07369.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Goranov AI, Katz L, Breier AM, Burge CB, Grossman AD. 2005. A transcriptional response to replication status mediated by the conserved bacterial replication protein DnaA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:12932–12937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506174102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Robson SA, Michie KA, Mackay JP, Harry E, King GF. 2002. The Bacillus subtilis cell division proteins FtsL and DivIC are intrinsically unstable and do not interact with one another in the absence of other septasomal components. Mol Microbiol 44:663–674. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Daniel RA, Errington J. 2000. Intrinsic instability of the essential cell division protein FtsL of Bacillus subtilis and a role for DivIB protein in FtsL turnover. Mol Microbiol 36:278–289. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bramkamp M, Weston L, Daniel RA, Errington J. 2006. Regulated intramembrane proteolysis of FtsL protein and the control of cell division in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol 62:580–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Parrell D, Zhang Y, Olenic S, Kroos L. 2017. Bacillus subtilis intramembrane protease RasP activity in Escherichia coli and in vitro. J Bacteriol 199:e00381-17. doi: 10.1128/JB.00381-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wadenpohl I, Bramkamp M. 2010. DivIC stabilizes FtsL against RasP cleavage. J Bacteriol 192:5260–5263. doi: 10.1128/JB.00287-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hanawalt P, Setlow R. 1960. Effect of monochromatic ultraviolet light on macromolecular synthesis in Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Acta 41:283–294. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(60)90011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gates FL. 1933. The reaction of individual bacteria to irradiation with ultraviolet light. Science 77:350. doi: 10.1126/science.77.1997.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Witkin EM. 1967. The radiation sensitivity of Escherichia coli B: a hypothesis relating filament formation and prophage induction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 57:1275–1279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.57.5.1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.George J, Castellazzi M, Buttin G. 1975. Prophage induction and cell division in E. coli. III. Mutations sfiA and sfiB restore division in tif and lon strains and permit the expression of mutator properties of tif. Mol Gen Genet 140:309–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gayda RC, Yamamoto LT, Markovitz A. 1976. Second-site mutations in capR (lon) strains of Escherichia coli K-12 that prevent radiation sensitivity and allow bacteriophage lambda to lysogenize. J Bacteriol 127:1208–1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Huisman O, D'Ari R, George J. 1980. Further characterization of sfiA and sfiB mutations in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 144:185–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Huisman O, D'Ari R. 1981. An inducible DNA replication-cell division coupling mechanism in E. coli. Nature 290:797–799. doi: 10.1038/290797a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cole ST. 1983. Characterisation of the promoter for the LexA regulated sulA gene of Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet 189:400–404. doi: 10.1007/bf00325901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mizusawa S, Court D, Gottesman S. 1983. Transcription of the sulA gene and repression by LexA. J Mol Biol 171:337–343. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(83)90097-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Huisman O, D'Ari R, Gottesman S. 1984. Cell-division control in Escherichia coli: specific induction of the SOS function SfiA protein is sufficient to block septation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 81:4490–4494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.14.4490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mizusawa S, Gottesman S. 1983. Protein degradation in Escherichia coli: the lon gene controls the stability of sulA protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 80:358–362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.2.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Schoemaker JM, Gayda RC, Markovitz A. 1984. Regulation of cell division in Escherichia coli: SOS induction and cellular location of the sulA protein, a key to lon-associated filamentation and death. J Bacteriol 158:551–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bi E, Lutkenhaus J. 1993. Cell division inhibitors SulA and MinCD prevent formation of the FtsZ ring. J Bacteriol 175:1118–1125. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.4.1118-1125.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bi E, Lutkenhaus J. 1990. Analysis of ftsZ mutations that confer resistance to the cell division inhibitor SulA (SfiA). J Bacteriol 172:5602–5609. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.10.5602-5609.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mukherjee A, Cao C, Lutkenhaus J. 1998. Inhibition of FtsZ polymerization by SulA, an inhibitor of septation in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:2885–2890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lutkenhaus J, Sanjanwala B, Lowe M. 1986. Overproduction of FtsZ suppresses sensitivity of lon mutants to division inhibition. J Bacteriol 166:756–762. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.3.756-762.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Huang J, Cao C, Lutkenhaus J. 1996. Interaction between FtsZ and inhibitors of cell division. J Bacteriol 178:5080–5085. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.17.5080-5085.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Trusca D, Scott S, Thompson C, Bramhill D. 1998. Bacterial SOS checkpoint protein SulA inhibits polymerization of purified FtsZ cell division protein. J Bacteriol 180:3946–3953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Chen Y, Milam SL, Erickson HP. 2012. SulA inhibits assembly of FtsZ by a simple sequestration mechanism. Biochemistry 51:3100–3109. doi: 10.1021/bi201669d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chung CH, Goldberg AL. 1981. The product of the lon (capR) gene in Escherichia coli is the ATP-dependent protease, protease La. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 78:4931–4935. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.8.4931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kanemori M, Yanagi H, Yura T. 1999. The ATP-dependent HslVU/ClpQY protease participates in turnover of cell division inhibitor SulA in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 181:3674–3680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wu WF, Zhou Y, Gottesman S. 1999. Redundant in vivo proteolytic activities of Escherichia coli Lon and the ClpYQ (HslUV) protease. J Bacteriol 181:3681–3687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Seong IS, Oh JY, Yoo SJ, Seol JH, Chung CH. 1999. ATP-dependent degradation of SulA, a cell division inhibitor, by the HslVU protease in Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett 456:211–214. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00935-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sonezaki S, Ishii Y, Okita K, Sugino T, Kondo A, Kato Y. 1995. Overproduction and purification of SulA fusion protein in Escherichia coli and its degradation by Lon protease in vitro. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 43:304–309. doi: 10.1007/bf00172829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Yasbin RE, Cheo D, Bayles KW. 1991. The SOB system of Bacillus subtilis: a global regulon involved in DNA repair and differentiation. Res Microbiol 142:885–892. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(91)90069-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Modell JW, Hopkins AC, Laub MT. 2011. A DNA damage checkpoint in Caulobacter crescentus inhibits cell division through a direct interaction with FtsW. Genes Dev 25:1328–1343. doi: 10.1101/gad.2038911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Love PE, Yasbin RE. 1984. Genetic characterization of the inducible SOS-like system of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 160:910–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kawai Y, Moriya S, Ogasawara N. 2003. Identification of a protein, YneA, responsible for cell division suppression during the SOS response in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol 47:1113–1122. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Mo AH, Burkholder WF. 2010. YneA, an SOS-induced inhibitor of cell division in Bacillus subtilis, is regulated posttranslationally and requires the transmembrane region for activity. J Bacteriol 192:3159–3173. doi: 10.1128/JB.00027-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Buist G, Steen A, Kok J, Kuipers OP. 2008. LysM, a widely distributed protein motif for binding to (peptido)glycans. Mol Microbiol 68:838–847. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Burby PE, Simmons ZW, Schroeder JW, Simmons LA. 2018. Discovery of a dual protease mechanism that promotes DNA damage checkpoint recovery. PLoS Genet 14:e1007512. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Burby PE, Simmons ZW, Simmons LA. 2019. DdcA antagonizes a bacterial DNA damage checkpoint. Mol Microbiol 111:237–253. doi: 10.1111/mmi.14151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Bojer MS, Wacnik K, Kjelgaard P, Gallay C, Bottomley AL, Cohn MT, Lindahl G, Frees D, Veening JW, Foster SJ, Ingmer H. 2019. SosA inhibits cell division in Staphylococcus aureus in response to DNA damage. Mol Microbiol 112:1116–1130. doi: 10.1111/mmi.14350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Chauhan A, Lofton H, Maloney E, Moore J, Fol M, Madiraju MV, Rajagopalan M. 2006. Interference of Mycobacterium tuberculosis cell division by Rv2719c, a cell wall hydrolase. Mol Microbiol 62:132–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Modell JW, Kambara TK, Perchuk BS, Laub MT. 2014. A DNA damage-induced, SOS-independent checkpoint regulates cell division in Caulobacter crescentus. PLoS Biol 12:e1001977. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Ogino H, Teramoto H, Inui M, Yukawa H. 2008. DivS, a novel SOS-inducible cell-division suppressor in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Mol Microbiol 67:597–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Rand L, Hinds J, Springer B, Sander P, Buxton RS, Davis EO. 2003. The majority of inducible DNA repair genes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis are induced independently of RecA. Mol Microbiol 50:1031–1042. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Brooks PC, Dawson LF, Rand L, Davis EO. 2006. The Mycobacterium-specific gene Rv2719c is DNA damage inducible independently of RecA. J Bacteriol 188:6034–6038. doi: 10.1128/JB.00340-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Dullaghan EM, Brooks PC, Davis EO. 2002. The role of multiple SOS boxes upstream of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis lexA gene—identification of a novel DNA-damage-inducible gene. Microbiology 148:3609–3615. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-11-3609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Jochmann N, Kurze AK, Czaja LF, Brinkrolf K, Brune I, Huser AT, Hansmeier N, Puhler A, Borovok I, Tauch A. 2009. Genetic makeup of the Corynebacterium glutamicum LexA regulon deduced from comparative transcriptomics and in vitro DNA band shift assays. Microbiology 155:1459–1477. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.025841-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Omasits U, Ahrens CH, Muller S, Wollscheid B. 2014. Protter: interactive protein feature visualization and integration with experimental proteomic data. Bioinformatics 30:884–886. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]