Abstract

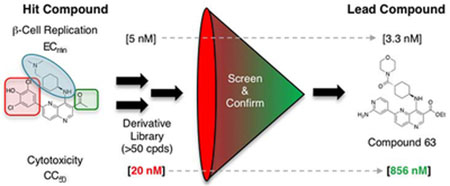

Small molecule stimulation of β-cell regeneration has emerged as a promising therapeutic strategy for diabetes. Although chemical inhibition of dual specificity tyrosine-phosphorylation-regulated kinase 1A (DYRK1A) is sufficient to enhance β-cell replication, current lead compounds have inadequate cellular potency for in vivo application. Herein, we report the clinical stage anti-cancer kinase inhibitor OTS167 as a structurally novel, remarkably potent DYRK1A inhibitor and inducer of human β-cell replication. Unfortunately, OTS167’s target promiscuity and cytotoxicity curtails utility. To tailor kinase selectivity towards DYRK1A and reduce cytotoxicity we designed a library of fifty-one OTS 167 derivatives based upon a modeled structure of the DYRK1A-OTS167 complex. Indeed, derivative characterization yielded several leads with exceptional DYRK1A inhibition and human β-cell replication promoting potencies but substantially reduced cytotoxicity. These compounds are the most potent human β-cell replication-promoting compounds yet described and exemplify the potential to purposefully leverage off-target activities of advanced stage compounds for a desired application.

Keywords: β-cell replication, β-cell regeneration, Dual-specificity tyrosine-regulated kinase 1A (DYRK1A), diabetes, medicinal chemistry

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Diabetes is a disorder of glucose homeostasis characterized by a mismatch between insulin supply and demand.1, 2 In normal physiology, insulin is secreted by pancreatic β-cells in proportional response to elevations in blood glucose; however, diabetes ensues when insulin secretion is insufficient to lower blood glucose, generally in conjunction with reduced β-cell mass.3, 4 In adult animals, new β-cells generated to increase insulin production capacity may arise from a variety of cell types including partially defined facultative progenitor cells, other islet cells and, most convincingly, previously existing β-cells.5–9 Among the variety of strategies for replacing an individual’s β-cell mass, expansion of endogenous β-cells remains paramount.

Although mature human β-cells do not typically exhibit vigorous expansion, human β-cell mass is flexible.7, 10, 11 β-cell number increases through early adulthood and modest compensatory β-cell mass expansion is an adaptive mechanism for avoiding hyperglycemia.6, 12–15 In T1D, up to 88% of individuals have a residual, functional, β-cell mass despite ongoing β-cell destruction.16–18 In pancreata of T1D patients, β-cells exhibit increased replication, suggesting an ongoing regenerative effort that could be pharmacologically supported.16, 17, 19 Importantly, replacement of β-cell mass with islet/pancreas transplantation can restore glucose homeostasis in T1D and T2D patients.20–22 While islet transplantation, whether cadaveric- or stem-cell-derived, may play an increased role in future T1D treatment, the expense and complexity of these procedures will limit widespread use. Consequently, developing a safe regenerative medication to expand residual β-cell mass would be transformative.

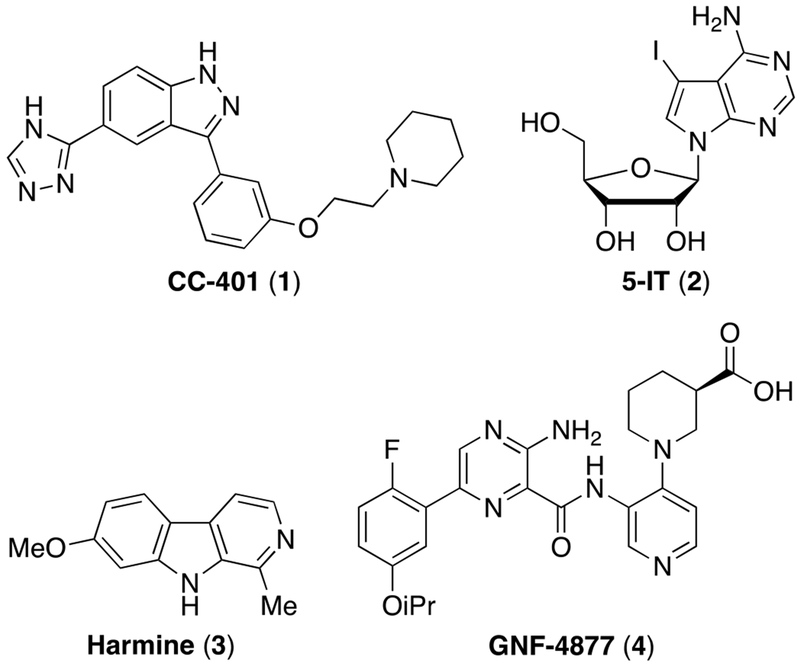

Historically, the major challenge to expanding human β-cell mass was the absence of human β-cell replication-promoting compounds. To address this gap, we developed a high-content primary β-cell replication-screening platform.23–26 Using this platform, we discovered chemically diverse small molecule inducers of β-cell replication including CC-401 1, 5-iodotubercidin (5-IT) 2, and JAK3 inhibitor VI, while others have identified harmine 3 (and derivatives) and aminopyrazines such as GNF-4877 4 (Figure 1).23, 26–31 Critically, most (if not all) compounds that exhibit human β-cell replication-promoting activity inhibit the dual-specificity tyrosine phosphorylation-regulated kinase 1A (DYRK1A), indicating a central role for DYRK1A in controlling human β-cell entry into cell cycle. Mechanistically, DYRK1A inhibition promotes replication via enabling nuclear localization of nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT), 26–29, 32 repression of the cell-cycle inhibitor p27kip1 and destabilization the multi-protein DREAM complex (DP, RBL1, RBL2, E2F4 and the MuvB core), which maintains cellular quiescence through repression of cell-cycle-promoting genes.23, 33, 34 Given the global role of DYRK1A in maintaining cellular quiescence,34 the immediate use of DYRK1A inhibitors in humans to promote β-cell expansion is limited by concerns for off-target growth-promoting activity.

Figure 1.

Representative chemical structures of small molecule inducers of β-cell replication.

To employ DYRK1A inhibitors as a regenerative therapy for diabetes, a strategy for selective delivery to β-cells in situ is necessary. Currently, a variety of β-cell targeting approaches are being explored including peptide- or antibody drug conjugation35–39 and conjugation to small molecules, including zinc chelator drug conjugation that leverages the uniquely high zinc content of β-cells40 and VMAT2 antagonists.41 Primary limitations of β-cell targeting strategies are (a) compound delivery capacity (ligand surface expression level and compound internalization/release kinetics) and (b) β-cell selectivity of compound delivery (off-target ligand expression and/or non-selective uptake/compound release).42 Notably, experience with antibody-drug conjugate systems for targeted delivery has demonstrated that compounds must exhibit exceptional potency in biochemical assays (IC50 in the 10–100 pM range) and cellular assays (<low nM range) to be efficacious.42 Unfortunately, candidate β-cell replication-promoting compounds have insufficient intrinsic DYRK1A inhibition [IC50] and/or human β-cell replication induction-potency [ECmin], respectively: 5-IT 2 (~10 nM; ~100 nM),26, 29 Harmine 3/Harmine-derivatives (~50 nM; ~3,000 nM)28, 30, 43 and GNF-4877 4 (6 nM; ~100 nM).27 Hence, there is a need to develop more potent DYRK1A inhibitors to realize the promise of a regenerative therapy for diabetes.44, 45

2. Results

2.1. Discovery of OTS167 as A Potent Inducer of Human β-Cell Replication

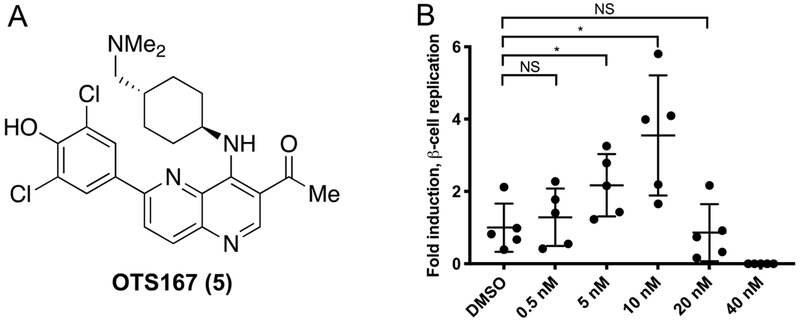

In prior work, we identified CC-401 1 as a DYRK1A inhibitor that promotes human β-cell replication.23 To gain insight into the mechanism of CC-401 1-dependent β-cell replication induction, we performed differential gene expression analysis on fluorescence activated cell-sorted (FACS) vehicle- and CC-401-treated β-cells. Interestingly, expression of the cell-cycle regulator maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase (MELK) was induced (2.6-fold) by CC-401 1.23 Given MELK’s role in activating forkhead box M1 (FOXM1),46 a master regulator of β-cell replication,47, 48 we hypothesized that inhibition of MELK would abrogate CC-401 1-dependent induction of human β-cell replication. Unexpectedly, OTS167 5, a chemotherapeutic MELK-inhibitor (OncoTherapy Science, Inc, Japan)49, 50 induced rather than inhibited human β-cell replication (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Structure and biological activity of OTS167 5. (A) Chemical structure of OTS167 5. (B) Relative human β-cell replication (Ki67+Insulin+ / Insulin+) in OTS167 5-treated wells (n = 5 per condition) compared to the vehicle-treated wells. This experiment was repeated with 3 independent donors with similar results (results from a single donor shown; standard deviation is indicated; *, p<0.05).

Strikingly, OTS167 5 was an exceptionally potent (ECmin = 5 nM) inducer of human β-cell replication, demonstrating efficacy at ~50-fold lower concentration than the most potent known β-cell replication promoting compound (GNF4877 4, ECmin ≈ 100 nM).27 Consistent with OTS167’s 5 clinical application as a cytotoxic agent, β-cell replication only occurred in a narrow dose range (~5–40 nM). Hence, OTS167 5 is a uniquely potent inducer of human β-cell replication with limited utility because of concomitant cytotoxicity. We hypothesized that the β-cell replication-promoting and cytotoxic activities of OTS167 5 resulted from inhibition of distinct (separable) kinase targets.

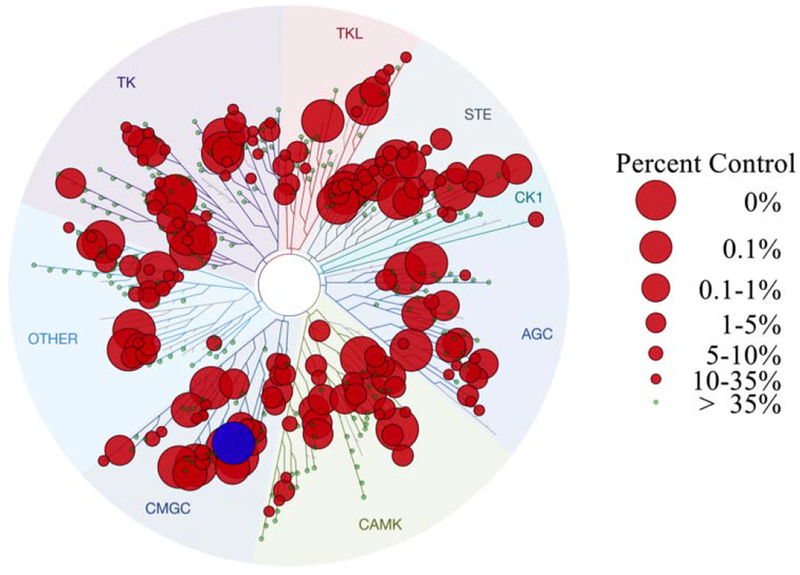

2.2. Evaluation of OTS167 Kinome Inhibition

To investigate our hypothesis that OTS167 5 promoted replication and cytotoxicity via inhibition of distinct kinase targets, we performed a kinome inhibition scan (468 kinases, DiscoverX) (Figure 3; Supporting Information Table 4S). OTS167 5 [100 nM] exhibited remarkable promiscuity, inhibiting 189/403 kinases to less than 35% of baseline activity. More striking, 69/403 of kinases showed <1% residual activity, including DYRK1A. Notably, inhibition of DYRK1A is sufficient to promote human β-cell replication,23, 27–30 indicating this was the likely mechanism of OTS167 5-induced human β-cell replication. By contrast, the basis of OTS167 5 cytotoxicity was less intuitive as it inhibited numerous targets with the potential to confer cytotoxicity (Figure 3). Although OTS167 5 was advanced through clinical trials (Phase I/II), the purported cytotoxic target (MELK) has been challenged.51–54 Indeed, the promiscuity of OTS167 5 indicated cytotoxicity was a consequence of inhibiting multiple pro-survival kinases.

Figure 3.

Kinase selectivity profile of OTS167 5. Kinome scan of 468 kinases with OTS167 5 at 100 nM. Circles indicate percent residual activity for an individual kinase. DYRK1A is highlighted (blue) as it was among the most inhibited kinases.

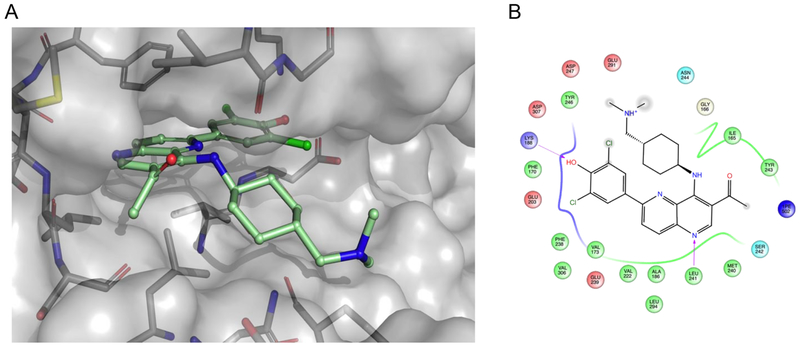

Given the likely role of DYRK1A inhibition in mediating OTS167 5-dependent replication induction, we modeled the OTS167 5-DYRK1A complex (Glide, Schrödinger) to identify key molecular interactions (Figure 4). Among these were H-bonds between the phenoxide (head group) and the side chains of the catalytic triad consisting of Lys188, Glu203, and Asp307, a H-bond between N1 of the 1,5-naphthyridine core and the hinge residue Leu241, and several Van der Waals interactions between the protein and the amino-cyclohexane group (tail group). The binding model revealed two regions of OTS167 5, the 3-position of the 1,5-naphthyridine ring (core group) and the dimethylamino group (tail group), that appeared amenable to non-disruptive modification. A third position, the dichlorophenol (head group) sat tightly within the ATP-binding pocket of DYRK1A and was likely to tolerate only small modifications. However, assuming a similar pose in other kinase targets, head group modifications were anticipated to substantially influence kinase selectivity. Therefore, to reduce cytotoxicity while retaining human β-cell replication-promoting activity (increased DYRK1A selectivity) we designed and synthesized a library of 1,5-naphthyridine analogs with modifications in these three regions. From a library design standpoint, we disregarded MELK as the primary target for cytotoxicity; this approach proved prudent, as cytotoxicity was independent of MELK inhibition activity (see below).

Figure 4.

Computational modeling of OTS167 5. (A) Modeled structure of OTS167 5 docked into the DYRK1A ATP-binding site. (B) Associated ligand interaction diagram between OTS167 5 and predicted key binding residues that are within 4 Å of the ligand. The gray spheres on atoms of OTS167 5 indicate regions that are solvent exposed. Arrows indicate key hydrogen bonds between the protein backbone (Leu241) and side-chain (Lys188) residues and the ligand. Negatively charged residues are indicated in red, positively charged residues are highlighted in blue, polar residues are highlighted in light blue, and hydrophobic residues are highlighted in green. Docking was performed using Schrodinger’s Glide software and PDB code 4MQ2 as the template for DYRK1A.55

2.3. Chemistry

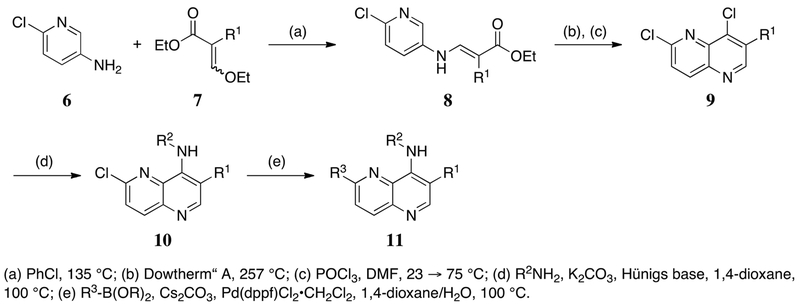

The synthetic route for 1,5-naphthyridine-based DYRK1A inhibitors facilitated generation of diverse compounds from common intermediates (Scheme 1). Construction of the 4, 6-dichloro-1,5-naphthyridine cores (10) was accomplished via the condensation of substituted aminopyridines with the desired 2-ethoxy methylene malonate derivatives, enabling the incorporation of several electron withdrawing groups (CO2Et, CN, C(O)Me) at what will be the 3-position of the naphthyridine systems. Heating of the condensation products in refluxing Dowtherm® A followed by chlorination delivered the desired core fragments. Exposure to a variety of elaborated amines under standard SNAr conditions introduced substituents at the 4-position of the naphthyridine ring. A final Suzuki coupling completed the desired DYRK1A inhibitors. Analogs containing amides at the 3-position (14) were accessed via ester hydrolysis and HATU coupling with the desired amine (Scheme 2).

Scheme 1.

General synthesis of 1,5-naphthyridine based DYRK1A inhibitors.

Scheme 2.

General synthesis of 3-carboxamide-1,5-naphthyridines

2.4. Primary Screen of DYRK1A Inhibition and Cytotoxicity

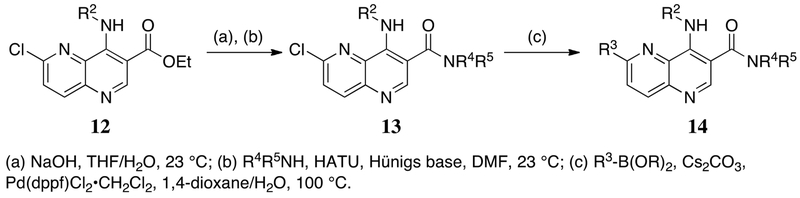

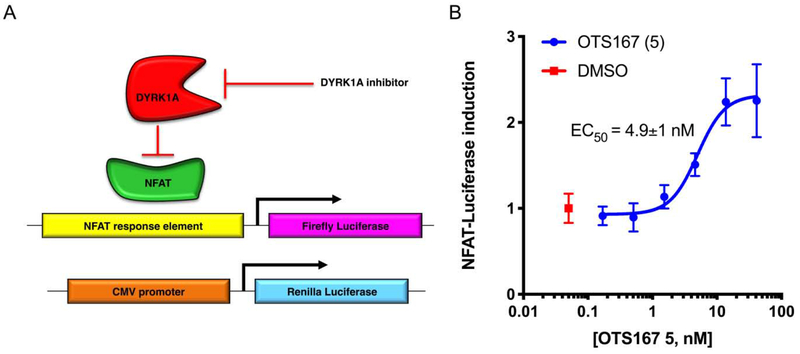

To perform primary screening of the OTS167-derived compound library, we simultaneously assessed cellular DYRK1A inhibition and cytotoxicity using a dual luciferase reporter system (Figure 5).23, 40 Determination of DYRK1A inhibition was based upon de-repression of an NFAT-dependent reporter (DYRK-Luc) activity. In this assay, OTS167 demonstrated potent DYRK1A inhibition (DYRK-Luc EC50 ≈ 5 nM; Table 1). To assess compound toxicity, we determined the concentration at which constitutive Renilla Luciferase (R-Luc) activity dropped by 50% (R-Luc CC50). While R-Luc activity is commonly used to normalize transfection efficiency, we observed a concentration-dependent loss of R-Luc activity in OTS167-treated HEK293T cells (CC50 ≈ 64 nM; Table 1) that was independent of transfection efficiency (the same population of transfected cells were treated with different compound concentrations). Further, the CC50’s based on R-Luc (R-Luc CC50) linearly correlated (R2 = 0.78) with CC50’s obtained by direct assessment of cell number (Supporting Information Figure 1S). Hence, loss of R-Luc served as a useful proxy for compound cytotoxicity (R-Luc CC50; Table 1).

Figure 5.

(A) Schematic representation of the cellular (HEK293) DYRK1A- and cytotoxicity-reporter assays. The potency of DYRK1A inhibitors (DYRK-Luc) was assessed based upon de-repression of the NFAT-dependent luciferase reporter construct which is silenced by DYRK1A kinase activity. Co-transfection of a constitutively active CMV-Renilla expression construct allowed concurrent assessment of cellular viability in response to compound treatment (R-Luc). (B) A representative result for OTS167 5, a dose curve of which was included as a positive control in every assay, with DMSO (n=8) included in every plate as a negative control.

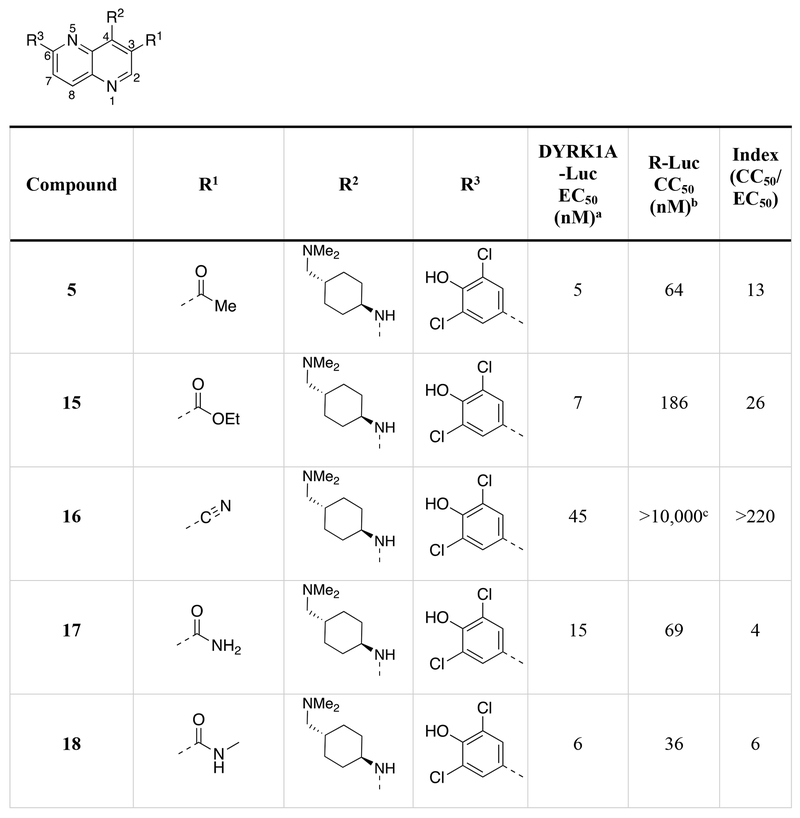

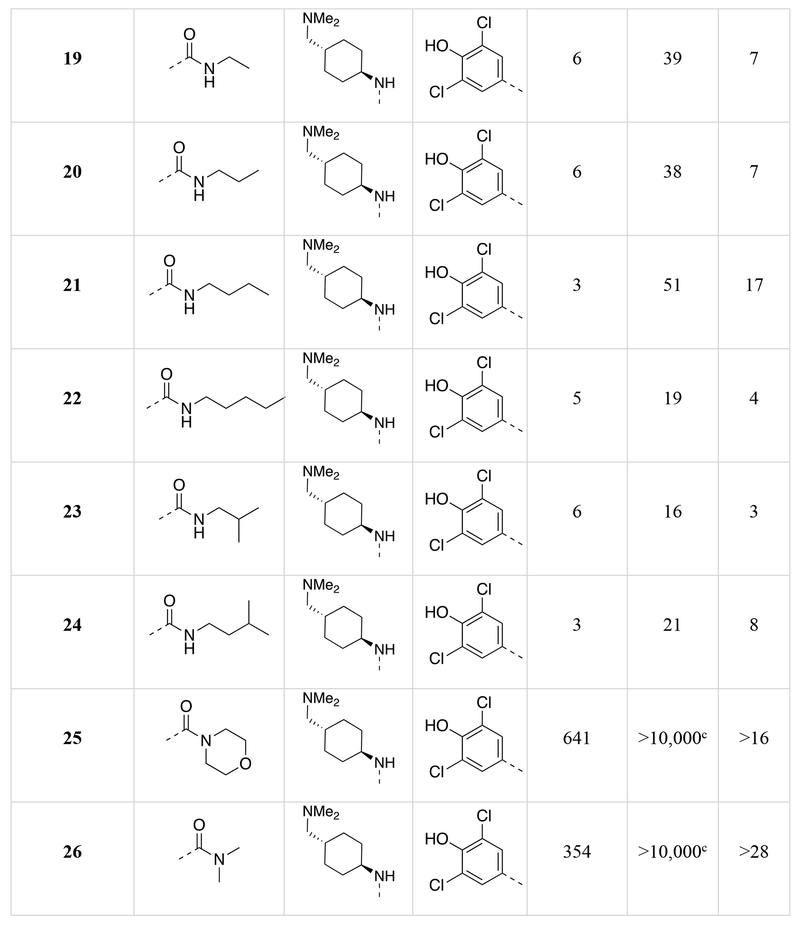

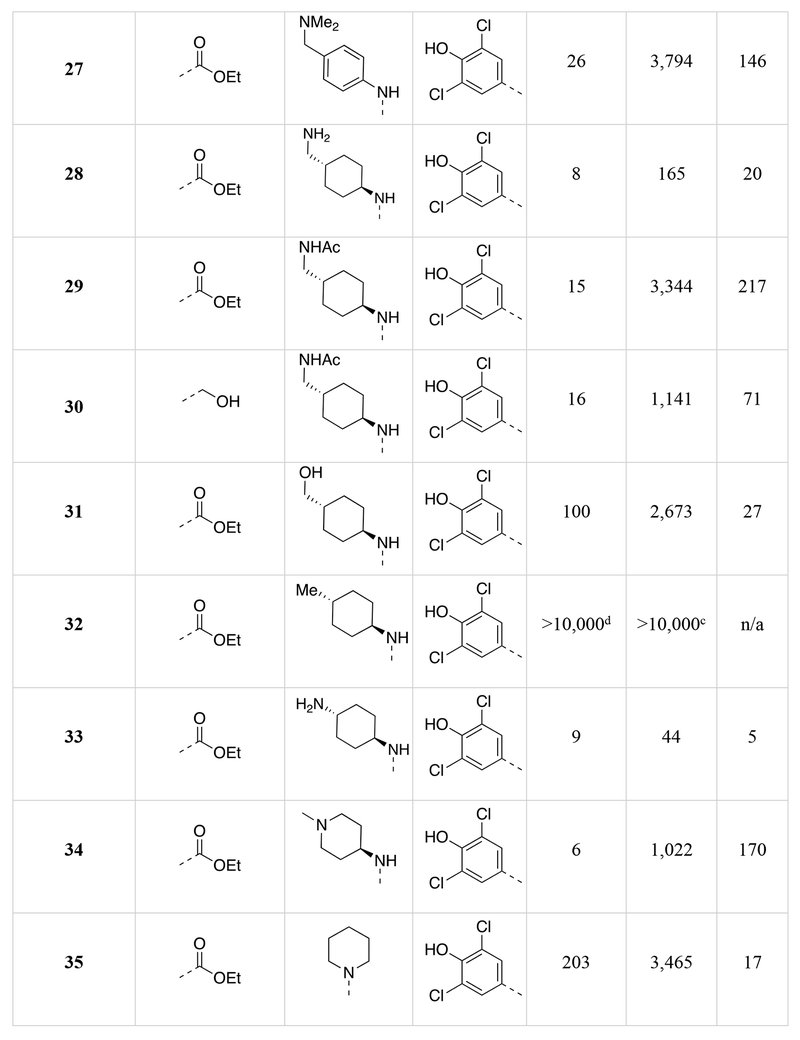

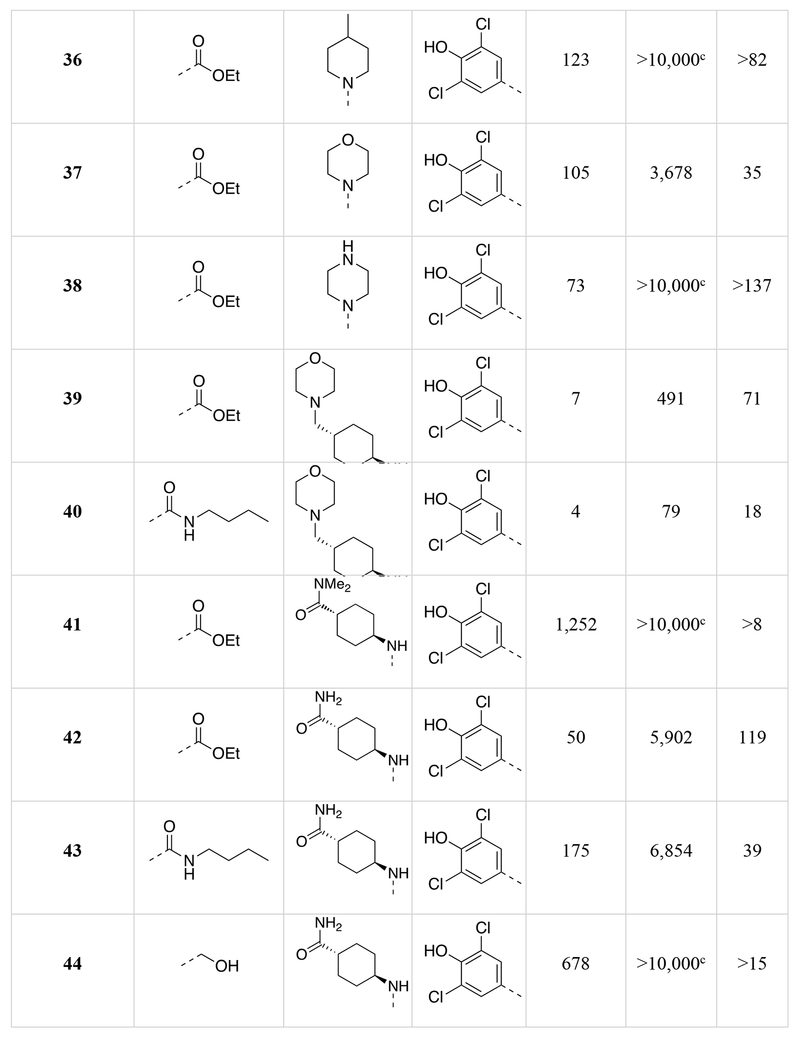

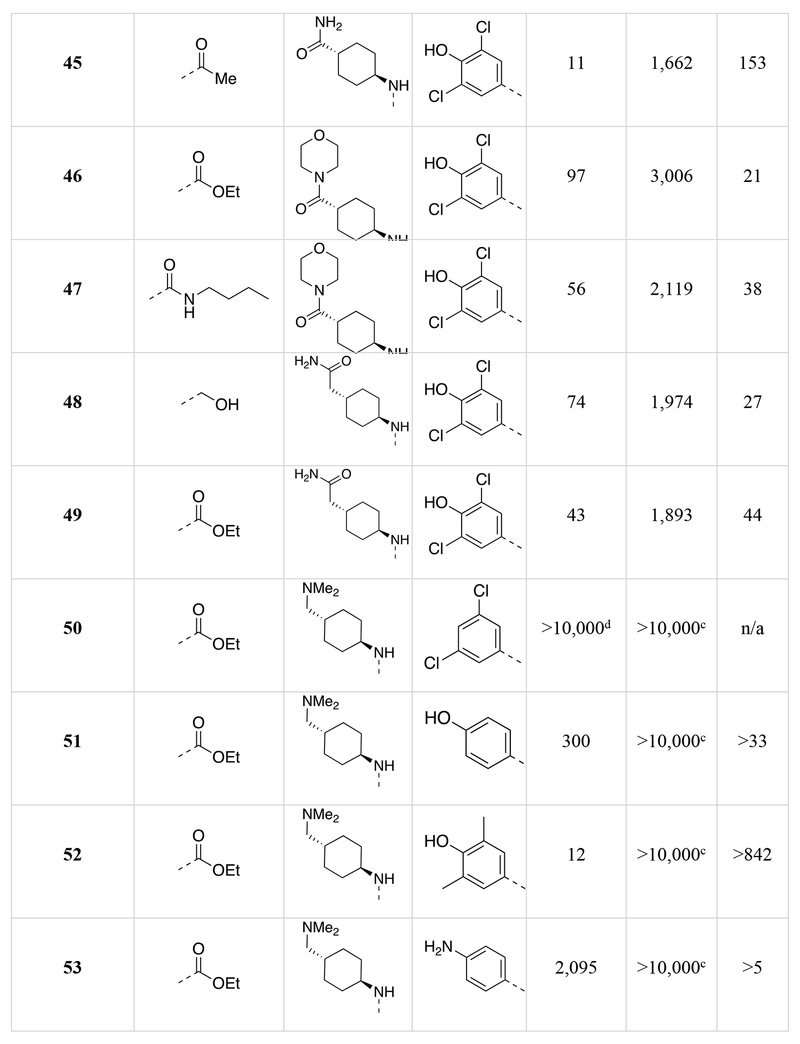

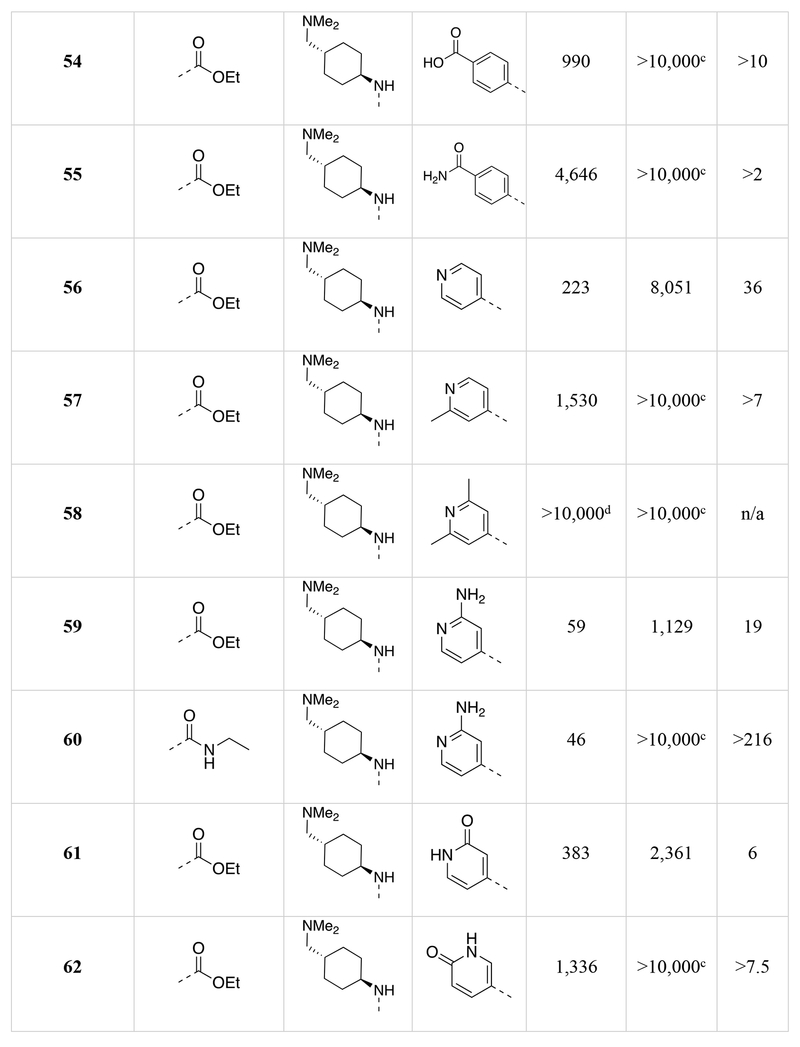

Table 1.

Chemical structures of the 1,5-naphthyridines library with measured DYRK1A inhibition potency (DYRK1A-Luc EC50), cytotoxicity (R-Luc CC50) and calculated cytotoxicity to DYRK1A inhibition ratio (Index) in HEK 293 cells are shown.

Calculated by 4-parameter agonist dose response (Graphpad) of the induction of DYRK1A-responsive firefly luciferase to test compound in a HEK293T reporter cell assay (11-point dose curve, n = 4 per concentration).

Calculated by 4-parameter inhibitor dose response (Graphpad) to test compound of constitutively-active renilla luciferase in a HEK293T reporter cell assay (11-point dose curve, n = 4 per concentration).

Compound did not inhibit renilla luciferase expression by >50% at 10 μM.

Compound did not stimulate firefly luciferase expression at 10 μM.

We determined the DYRK1A inhibition potency and cytotoxicity of fifty-one 1,5-naphthyridine derivatives with structural modifications at three different positions of the naphthyridine scaffold (Table 1). Generally, modifications to the electron-withdrawing group at the 3-position of the 1,5-naphthyridine system (R1; 15-26) resulted in minimal change to DYRK1A inhibition potency or cytotoxicity. However, introduction of an ethyl ester (15) at this position decreased cytotoxicity (~3-fold) compared to OTSS167 (R-Luc CC50 = 186 nM (15) vs. 64 nM (5)) with little effect on DYRK1A inhibition potency [DYRK1A-Luc EC50 = 7 nM (15) vs. 5 nM (5)]. Similarly, R1 substitutions with various carboxamides (17-24) minimally affected cytotoxicity or DYRK1A inhibition, consistent with our OTS167-DYRK1A interaction model. Carboxamides derived from secondary amines, like the morpholino (25) and dimethyl amide (26), exhibited no cytotoxicity (R-Luc CC50 = >10,000 nM, both); however these compounds also showed decreased DYRK1A inhibition (DYRK1A-Luc EC50 = 641 nM (25) and 354 nM (26)). Remarkably, introduction of a cyano-group (16) at the 3-position rendered the compound virtually non-toxic with only a ~9-fold reduction in DYRK1A inhibition potency. Overall the structure-activity relationships exhibited by substitution at the 3-position were flat with respect to DYRK1A inhibition, but in the case of compound 16 revealed significant reductions in toxicity. These results demonstrated the feasibility of separating the DYRK1A inhibition- and cytotoxic-activities of OTS167.

Next we assessed the activities of amine substituents that were introduced at the 4-position (R2; 27-49). Unexpectedly, substitution of an aromatic analog at this position (27) maintained DYRK1A inhibition potency, but reduced cytotoxicity by ~60-fold. The basic dimethyl amino group also played a remarkable role in modulating the toxicity of the compounds. Des-methyl compound 28 had activities (DYRK1A-Luc EC50 = 8 nM, R-Luc CC50 = 165 nM) comparable to the dimethyl analog (15), however the acetylated version (29) exhibited significantly reduced toxicity (R-Luc CC50 = 3,344 nM) while retaining potency against DYRK1A (DYRK1A-Luc EC50 = 15 nM). Notably, reducing the ester of compound 29 to an alcohol (30) maintained the reduced cytotoxicity (R-Luc CC50 = 1,142 nM) and potent DYRK1A inhibition (DYRK1A-Luc EC50 = 16 nM). Exchange of the amino group for a hydroxyl (31) was relatively tolerated; however, removal of a hydrogen bond donor/acceptor group in this position eliminated cellular activity (32). Moving the basic nitrogen atom into the ring in the 4-aminopiperidine analog (34) reduced cytotoxicity ~16-fold (R-Luc CC50 = 1,022 nM) without affecting DYRK1A inhibition potency (DYRK1A-Luc EC50 = 6 nM). Hence, compound 34 demonstrated a dramatic (~13-fold) increase in the Cytotoxicity / Activity Index. Thus, 34 demonstrated the feasibility separating the cytotoxic and DYRK1A-inhibition activities of OTS167 5 through substitutions at the 4-position of the 1,5-naphthyridine ring.

Additionally, we evaluated the activity of several cyclic secondary amines substituted at the 4-position of the 1,5-naphthyridine ring (R2). Piperidine analogs 35 and 36, morpholino analog 37, and piperazine analog 38 all exhibited reduced cytotoxicity while also demonstrating reduced DYRK1A inhibition potency. However, the presence of a basic amine (piperazine) in the R2 position (38) minimized the loss in DYRK1A inhibition potency (DYRK1A-Luc EC50 = 73 nM), while significantly reducing cytotoxicity (R-Luc CC50 = ≥10,000 nM); resulting in a desirable cytotoxicity / Activity Index (Index (CC50/EC50) =137).

Several compound pairs with substitutions at both the 3- and 4-positions produced activities that were divergent from what was observed when only a single position was modified. The 4-(morpholinomethyl)cyclohexanamine analogs 39 and 40 had similar DYRK1A potencies (DYRK1A-Luc EC50 = 7 nM vs 4 nM respectively), yet the ester analog 38 was 7-fold less toxic than its butyl amide counterpart 39 (R-Luc CC50 = 491 nM vs 79 nM). The morpholino amide analogs 46 (R1 = ethyl ester) and 47 (R1 = butyl amide) had similar cellular activities and toxicities. The 4-aminocyclohexane carboxamide derived compounds 42 and 43 had similar toxicities (R-Luc CC50 = 5,912 nM vs 6,854 nM, respectively), yet the ethyl ester 42 was more potent against DYRK1A than the butyl amide 43 (DYRK1A-Luc EC50 = 50 nM vs 175 nM respectively), indicating that substitutions at the 3-position (R1) of the 1,5-naphthyridines that reduce cytotoxicity are context-dependent.

The last region of 5 we explored was the head group (R3) that makes a key interaction with the catalytic Lys188 of DYRK1A. Although modeling indicated that modifications in this region would affect DYRK1A potency, effects on cytotoxicity were less predictable without knowledge of the relevant kinase target(s). As expected, removal of the 4-hydroxyl (50) abrogated DYRK1A-inhibition, while removal of the Cl-atoms in analog 51 reduced the DYRK1A-Luc EC50 to 300 nM, and rendered the compound nontoxic (R-Luc CC50 = >10,000 nM). Our docking model indicated the two Cl-atoms were filling small hydrophobic pockets adjacent to the catalytic triad residues. Interestingly, similar interactions were maintained by methyl groups (52) (DYRK1A-Luc EC50 = 12 nM) while profoundly reducing cytotoxicity (R-Luc CC50 = >10,000 nM), resulting in the best Index score (>842) of the library. The 4-pyridyl 56 was also relatively tolerated, though this compound’s potency against DYRK1A decreased to 223 nM. Presence of adjacent methyl groups (57 and 58) reduced DYRK1A binding to >10,000 nM while the presence of an amino group adjacent to the pyridine nitrogen (59) retained DYRK1A inhibition potency (DYRK1A-Luc EC50 = 59 nM). Exchange of the ethyl ester in 59 with and ethyl amide 60 maintained good DYRK1A activity, but dramatically reduced cytotoxicity (R-Luc CC50 = >10,000 nM).

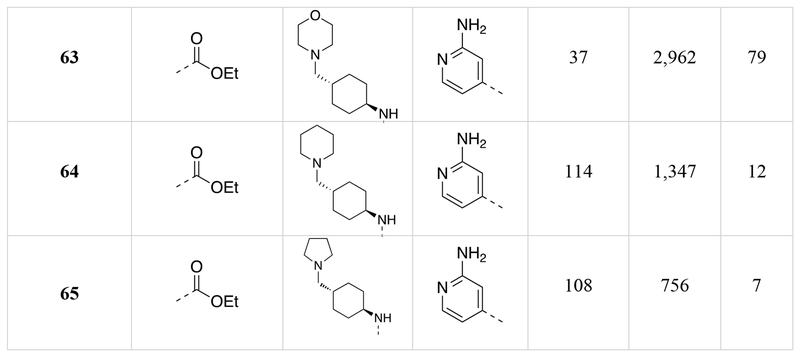

2.5. Characterization of the OTS167 Cytotoxic Mechanism

Although MELK inhibition is the purported mechanism of OTS167 cytotoxicity, several publications have challenged this conclusion.51–54 To assess the contribution of MELK inhibition to cytotoxicity, we evaluated the relationship between MELK binding affinity (MELK Kd) and cellular cytotoxicity (R-Luc CC50) among a small collection of compounds (5, 15, 21, 28 and 42). These compounds were selected based upon a linear relationship between DYRK1A binding affinity (DYRK1A Kd) and cellular DYRK1A inhibition (DYRK1A-Luc EC50) (R2 = 0.98, p-value of slope = 0.0016) (Figure 6) to exclude confounding impacts of cell permeability. As suggested by others, a correlation between MELK binding affinity and cytotoxicity was not observed (R2 = 0.05, p-value of slope=0.71) (Table 2, Figure 6). Although these compounds demonstrated potent MELK binding affinity (Kd ≤15 nM), cytotoxicity (R-Luc CC50) ranged from 51 nM to 5,900 nM. Hence, inhibition of MELK was not sufficient for cytotoxicity.

Figure 6.

DYRK1A binding correlates to DYRK-NFAT EC50 and β-cell replication, while MELK binding does not correlate to cytotoxicity. (A) Selected compounds (5, 15, 21, 28, and 42) for which DYRK-NFAT EC50 was linear with DYRK1A Kd (R2=0.98) plotted as DYRK-NFAT EC50 vs DYRk1A Kd. (B) The same compounds (5, 15, 21, 28, and 42) with R-Luc CC50 plotted versus MELK Kd (R2=0.05). (C) The same compounds (5, 15, 21, 28, and 42) with human β-cell replication ECmin plotted versus DYRK1A Kd (R2=0.99).

Table 2:

Comparisons of DYRK1A Kd vs DYRK1A-Luc EC50 and MELK Kd versus cytotoxicity (R-Luc CC50) for select 1,5-naphthyridines.

| Compound | DYRK1A Kd (nM) | DYRK1A-Luc EC50 (nM) | MELK Kd (nM) | R-Luc CC50 (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 0.12 | 5 | 15 | 64 |

| 15 | 0.16 | 7 | 11 | 186 |

| 21 | 0.075 | 3 | 12 | 51 |

| 28 | 0.22 | 8 | 9 | 165 |

| 42 | 0.6 | 50 | 13 | 5900 |

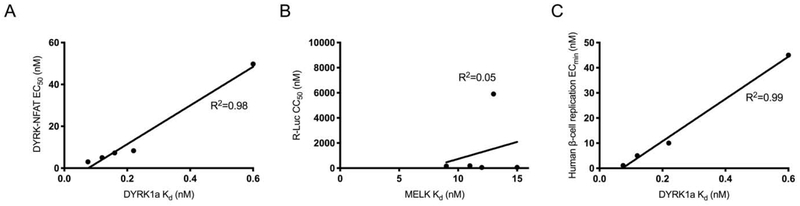

To identify kinase targets relevant to OTS167 5 cytotoxicity, we compared the kinome selectivity of compound (56) (R-Luc CC50 = 8,051 nM) to OTS167 5 (R-Luc CC50 = 64 nM) (Figure 7). Compound 56 was prioritized for further characterization based on <30 nM human beta-cell replication potency and >1000 nM R7T1 toxicity as discussed below. Importantly, these compounds have equivalent MELK binding affinity (MELK Kd = 15 nM). Remarkably, the simple substitution of the dichlorophenol group with a pyridyl resulted in a dramatic improvement in kinase selectivity. By filtering for targets robustly inhibited by OTS167 5 but not inhibited by compound 56, we obtained a narrowed list of potential cytotoxic targets. Of the 468 kinases assayed, 40 were strongly inhibited (<2% residual activity) by OTS167 5 at a concentration of 100 nM but not by compound 56 at a concentration of 500 nM. Although the promiscuity of OTS167 5 indicated toxicity was likely to be multifactorial, we selected five differentially inhibited kinases (AURKA/B, MAP2K1/2, and ABL1) with pro-survival activity for further analysis.56–58

Figure 7.

Kinase selectivity profile for compound 56. (A) Kinome scan with compound 56 at 500 nM. DYRK1A is highlighted (blue). (B) Activity of select kinases (ABL1, DYRK1A, AURKB, AURKA, MAP2K1, MAP2K2, and MELK) with OTS 167 5 (100 nM) or compound 56 (500 nM) as a percent of the control (DMSO-treated) activity.

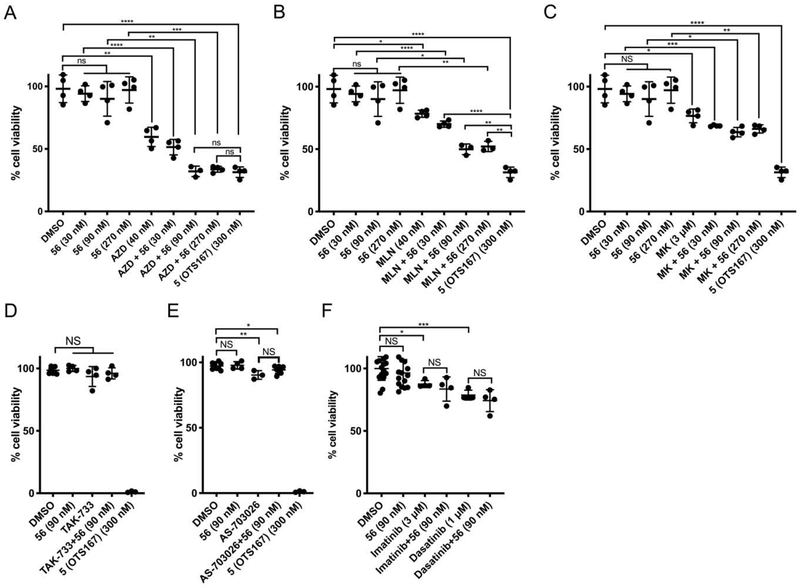

To test our hypothesis that the inhibition of AURKA/B, MAP2K1/2 and/or ABL1 mediated the OTS167 cytotoxicity, we identified relatively selective chemical inhibitors of each of these targets: AURKA (MK-5108; MK), AURKB (AZD-1152-HQPA; AZD), AURKA/B (MLN-8054, MLN), MAP2K1/2 (TAK-733 and AS-703026) and ABL1 (Dasatanib and Imatinib).59–67 We reasoned, for example, that if OTS167 5 inhibition of AURKA/B was responsible for cytotoxicity, then (A) AZD, MK, and/or MLN would be cytotoxic in our model system, and/or (B) the combination of AURKA/B inhibition with compound 56 would recapitulate the cytotoxicity of OTS167 5. Informatively, both results were observed (Figure 8, Supporting Information Figure 2S).

Figure 8.

Combination of 56 with inhibitors of AURKB but not MAP2K1/2 or ABL1 reduces cell viability. HEK293T cells were treated with (A) DMSO, 56 (30 nM, 90 nM, and 270 nM), AZD-1152-HQPA (40 nM) without and with 56, or 5 (300 nM); (B) DMSO, 56 (30 nM, 90 nM, and 270 nM), MLN-8054 (40 nM) without and with 56, or 5 (300 nM); (C) DMSO, 56 (30 nM, 90 nM, and 270 nM), MK-5108 (3 μM) without and with 56, or 5 (300 nM); (D) DMSO, 56 (90 nM), TAK-733 (10 μM) without and with 56, or 5 (300 nM); (E) DMSO, 56 (90 nM), AS-703026 (10 μM) without and with 56, or 5 (300 nM); and (F) DMSO, 56 (90 nM), Imatinib (3 μM) without and with 56, or Dasatinib (1 μM) without and with 56. Cells were treated for 48 hrs, fixed, stained, counted, and cell number plotted as a percentage of untreated wells. Error bars indicate standard deviation (n = 4-16, ****,p<0.0001; ***, 0.0001<p<0.001; **, 0.00<p<0.01; *, 0.01<p<0.05; NS, p>0.05).

AZD (CC50 = 38.9 nM) and MLN (CC50 = 55.1 nM) were highly cytotoxic, while MK was not (CC50 = >10 μM); indicating that AURKB inhibition, but not AURKA, contributed to the cytotoxicity of OTS167 5. Furthermore, combining AURKB inhibitors with 56 enhanced cytotoxicity. Compound 56 exhibited no cytotoxicity at 30 nM, 90 nM or 270 nM while AZD reduced cell number by 41% at 40 nM (p=0.0012). However, combining of AZD (40 nM) with compound 56 [(90 nM] or (270 nM)] resulted in a 67% reduction in cell number (p=2.01x10−4 and p=2.7 × 10−5 vs DMSO; p=0.0026 and p=6.5 × 10−4 vs AZD; Figure 8); similar to treatment with OTS167 5 (300 nM). Likewise, MLN killed only 22% of cells at 40 nM (p=0.013), but was augmented to 50% when combined with compound 56 (90 nM or 270 nM; p=8.9 × 10−4 and p=0.0011 vs DMSO; p=1.2 × 10−4 and p=1.7 × 10−4 vs MLN; Figure 8). These results are consistent with reports that inhibition of AURKB by OTS167 5 is at least partially responsible for its cancer-killing effects.54 The AURKA-selective inhibitor MK [3 μM] alone killed 24% of cells (p=0.013) while supplementation with 56 further reduced cell viability (31%, 36%, and 34%; p=0.0018, p=0.0010, p=0.0014 vs DMSO; p=0.029, p=0.008, p=0.018 vs MK). The relatively poor potency of this compound may indicate that residual AURKB inhibition (200-fold higher IC50 than AURKA),59 rather than its primary effect of AURKA inhibition, is responsible for the cytotoxicity in this case. By contrast, the MAP2K1/2 inhibitor TAK-733 (10 uM) did not exhibit cytotoxicity when tested alone or in combination with 56 (30 nM, 90 nM, or 270 nM). The MAP2K1/2 inhibitor AS-703026 (10 uM) only killed 10% of cells (p=0.006), and combination with 56 (90 nM) killed 6% of cells (p=0.048), which were not significantly different (p=0.071). Similarly, ABL1 inhibition with Dasatinib (1 μM) or Imatinib (3 μM) exhibited some cytotoxicity when tested alone (21% and 12.5%, p=0.019 and p=4.0 × 10−4 versus DMSO), and combination with 56 did not cause additional cell death (p=0.39 and p=0.46). Taken together, OTS167 5 cytotoxicity was mediated in part via inhibition of AURKB but not AURKA, MAP2K1/2 or ABL1. However, the increased cytotoxicity observed with combined AURKB inhibitor and compound 56 treatment indicated cytotoxicity was multifactorial and did not exclude a contributing role of MELK inhibition.

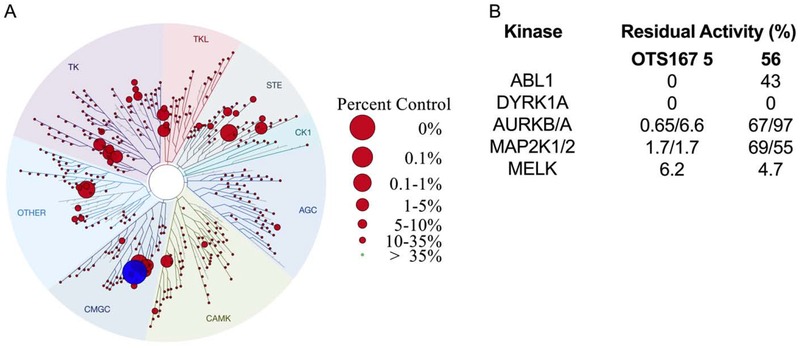

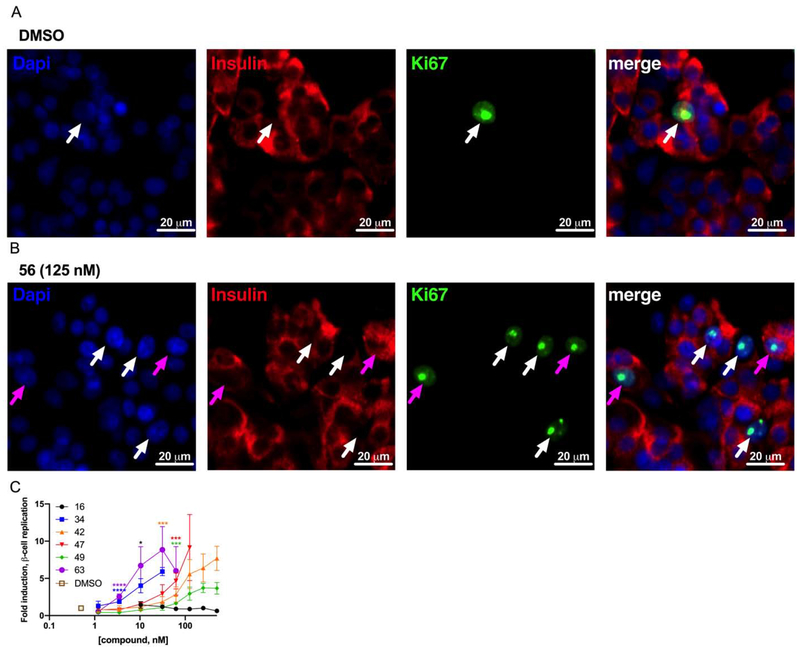

2.6. Secondary Screening for β-Cell Cytotoxicity and Human β-Cell Replication Induction

The objective of the primary screening was to identify 1,5-naphthyridine analogs that retained DYRK1A inhibition potency and reduced cytotoxicity. Accordingly, we selected 18 compounds with a DYRK1A-Luc EC50 ≤100 nM and an R-Luc CC50 ≥500 nM for further characterization, including β-cell cytotoxicity (R7T1 cells) and human β-cell replication-promoting activity (Table 3, Figure 9, Supporting Information Figure 3S, Supporting Information Table 5S, Supporting Information Table 7S).68 As anticipated, R7T1 β-cells were generally more sensitive to compound cytotoxicity than HEK293T cells, with the majority of compounds exhibiting a ~3-fold increase (Tables 1 and 3). Surprisingly, the 3-cyano substituted naphthyridine 16 and the 3-amino-4-pyridyl analog 60 exhibited cytotoxicity towards R7T1 β-cells (CC50 = 160 nM, 300 nM respectively) but not HEK293 cells (R-Luc CC50 = >10,000 nM). Compounds, 34 and 63 exhibited similar human β-cell replication-promoting potency (ECmin = 3.3 nM) to OTS167 5, with a greatly improved toxicity/replication Index (R7T1 CC50/Islet ECmin of 117 and 259, respectively). Interestingly, the human β-cell replication-promoting activity of compounds 30 and 52 was less than anticipated (ECmin = 500 nM and 250 nM respectively) from their DYRK1A-Luc assay potency (EC50 = 16 nM and 12 nM respectively). We also observed a discordance between DYRK1A-Luc and human β-cell replication-promoting activities with compounds 59 and 60. Structurally, these compounds are highly similar, differing only in the naphthyridine ring 3-substitution. While these compounds had comparable activities in the DYRK1A-Luc assay [EC50 = 59 nM (59), EC50 = 46 nM (60)], the ethyl ester 59 was a significantly more potent inducer of β-cell replication (ECmin = 22 nM) than the ethyl amide 60 (ECmin = >500 nM). Although the basis of these discrepancies is unknown, these data indicate that the relationship between DYRK1A inhibition and β-cell replication-promoting potencies are not necessarily direct.

Table 3.

Human β-cell replication and R7T1 β-cell cytotoxicity of selected compounds.

| Compound | Human Islets ECmin (nM) | R7T1 CC50 (nM) | Index, R7T1CC50/Human Islet ECmin (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 (OTS167) | 5 | 20 | 4 |

| 16 | 10 | 160 | 16 |

| 27 | 31 | 226 | 7.3 |

| 29 | 68 | 1,018 | 15 |

| 30 | 500 | 1712 | 3.4 |

| 31 | 250 | 785 | 3.1 |

| 34 | 3.3 | 387 | 117 |

| 38 | 250 | >10,000 | >40 |

| 42 | 31 | 2,814 | 91 |

| 43 | 125 | 1,790 | 14 |

| 45 | 125 | 231 | 1.8 |

| 46 | 250 | 2,080 | 8.3 |

| 47 | 63 | 2,440 | 39 |

| 48 | 500 | 1,080 | 2.2 |

| 49 | 63 | 1,390 | 22 |

| 52 | 250 | >10,000 | >40 |

| 56 | 27 | 3864 | 143 |

| 59 | 22 | 328 | 15 |

| 60 | >500 | 330 | n/a |

| 63 | 3.3 | 856 | 259 |

Figure 9.

Human β-cell replication. Representative images of dispersed human islets treated with (A) DMSO or (B) compound 56 (125 nM) and stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue), anti-insulin (red), and anti-Ki67 (green). Replicating cells not definitively insulin positive (white arrows) and replicating β-cells (magenta arrows) are indicated. Images were processed in parallel and cropped. (C) Relative human β-cell replication (Ki67+Insulin+ / Insulin+) in compound-treated treated wells (n = 3 per condition). Asterisks indicate significance testing compared to vehicle-treated wells. Error bars indicate standard deviation (*, 0.01<p<0.05; **, 0.001<p<0.01; ***, 0.0001<p<0.001; ****,p<0.0001).

Several newly generated compounds exhibited limited R7T1 cytotoxicity and induced human β-cell replication at a lower concentration than GNF-4877 4 (ECmin <100 nM). Consequently, we assessed the compatibility of these compounds with in vivo dosing (Table 4). Surprisingly, ester-containing compounds 34, 42 and 49 showed remarkable stability in mouse and human liver microsomes (MLM and HLM, respectively), while the ester-containing compounds 56 and 63 was readily metabolized in both MLM and HLM. Additionally, the stability of 47 was relatively promising (MLM t1/2 = >159 min, HLM t1/2 = 95 min) with robust Caco-2 permeability (9.1 × 10−6 cm/s). Hence, this work yielded several novel 1,5-naphthyridines with desired activities and drug-like characteristics.

Table 4:

Physicochemical properties and in vitro characterization of select compounds.

| Compound | TPSA (Å2) | cLogP | cLogD7.4 | MLM t1/2 (min) | HLM t1/2 (min) | Caco-2 (1 x 10−6 cm/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 34 | 87.6 | 4.75 | 2.73 | 129 | >159 | 4.6 |

| 42 | 127 | 4.93 | 3.53 | >159 | >159 | 0.12 |

| 47 | 117 | 5.20 | 3.30 | >159 | 95 | 9.1 |

| 49 | 127 | 5.12 | 3.70 | >159 | 28 | 0.01 |

| 56 | 80.2 | 4.03 | 1.49 | 6 | 32 | 4.03 |

| 63 | 116 | 3.58 | 2.73 | 15 | 37 | 2.7 |

3. Conclusions

We have developed a series of 1,5-naphthyridine derivatives from OTS167 5 that exhibit highly potent human β-cell replication-promoting activity and dramatically reduced cytotoxicity. The generation of compounds 34, 42, 47, 49, 56, and 63 demonstrate an important, underappreciated, avenue for lead series development: desirable, highly potent “off-target” activities of advanced lead compounds can be selectively distilled through the tailored use of medicinal chemistry and sequential bioactivity screening. Herein we leveraged this approach to generate highly potent, relatively non-cytotoxic human β-cell replication-promoting compounds from an advanced stage chemotherapeutic, OTS167 5. Further optimization of these compounds for in vivo use and β-cell targeted delivery are the next major challenges to developing a regenerative therapy for diabetes.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Biological and Biochemical Assays

4.1.1. DYRK1A NFAT Luciferase Response Assay

Constructs encoding human NFATc1 (NM_001278669) and human DYRK1A (NM_001396) were previously described.23 The interleukin 2–based pGL3-NFAT luciferase reporter construct was obtained from Addgene (catalog no. 17870; Cambridge, MA). Luciferase assays were performed by transfecting (0.625 mg polyethylenimine/1 mg of DNA) 10-cm tissue culture plates of 90% confluent HEK293T (RRID: CVCL_0063) cells with DYRK1A (7.5 mg), Renilla plasmid (10.5 mg; Promega), PGL3-NFAT luciferase (4.5 mg), and NFATc1 (1.5 mg). The next day, cells were trypsinized and transferred to 96-well plates (50 mL/well, 1/300th of total cell volume). After 6 h, wells were treated with vehicle or compound as indicated (n ≥ 4 per treatment condition) for 48 h before being lysed (catalog no. El500; Promega) for luciferase measurement (Modulus Microplate; Turner Bio- systems/Promega). In every assay, OTS167 5 was run as a positive control, and DMSO was run as a negative control (n=8 per plate). EC50 values were calculated by plotting the ratio of the Firefly/Renilla luciferase readings against the concentration using and fitting to a 4-parameter response curve in Prism (Graphpad). Maximal values were duplicated and the remaining values were excluded in cases where toxicity resulted in response decrement.

4.1.2. DYRK1A Kinase Binding Assay

Kd’s were determined by DiscoverX using an 11-point 3-fold compound dilution series with three DMSO control points as described in their KdElect binding assay. For more information see https://discoverx.com/services/drug-discovery-development-services/kinase-profiling/kinomescan/kdelect.

4.1.3. Kinome Scan Profiles

Select compounds were screened for activity against 468 kinases at either 100 nM or 500 nM using the Kinome SCAN Assay at DiscoverX. See the supporting information (Supporting Information Table 4S) for the complete panel results.

4.1.4. Caco-2 Permeability Assay

Caco-2 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. For transport experiments 5 × 105 cells/well of were seeded on polycarbonate filter inserts and allowed to grow and differentiate for 21 ± 4 days before the cell monolayers were used for experiments. Apparent permeability coefficients were determined for A → B and B → A directions with and without the presence of elacridar as a transporter inhibitor. Up to three test items and reference compounds were dissolved in Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) at pH 7.4 to yield a final concentration of 10 μM. The assays were performed in HBSS containing 25 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) (pH 7.4) at 37 °C. Prior to the study, the monolayers were washed in prewarmed HBSS. At the start of experiments, pre-warmed HBSS containing the test items was added to the donor side of the monolayer and HBSS without test items was added to the receiver side. Aliquots of the receiver side were taken over the 2 h incubation period; aliquots of the donor side were taken at 0 h and 2 h. Aliquots were diluted with an equal volume of methanol/water with 0.1% formic acid containing the internal standard. The mixture was analyzed by LC–MS/MS. The apparent permeability coefficients (Papp) were calculated using the formula: Papp = (dCrec/dt)/(A × C0,donor) × 106 with dCrev/dt being the change in concentration in the receiver compartment with time, C0,donor the concentration in the donor compartment at time 0, and A the area of the compartment with the cells.

4.1.5. Microsome Stability Assays

Human liver microsomes (Coming #452117 lot 38291) or Mouse liver microsomes (Corning #452701, lot# 6328004) were separately combined at a final concentration of 11.25 mg protein/compound with KxPO4 pH 7.4 (100 mM), MgCl2 (10 mM), and test compound (1 μM) and pre-incubated (10 min, 37 °C). Next, NADPH (1 mM) was added to begin reactions (total volume 100 μL). At various time points (0, 10, 20, and 40 mins), reactions were quenched with Clem stop solution (100 μL, 625 ng/mL) (Cyprotex) in Acetonitrile. Samples were centrifuged at 4000g for 20 mins, diluted (75 μL into 75 μL 0.1% formic acid in water), and analyzed by LC-MS/MS.

4.1.6. R7T1 Cytotoxicity

R7T1 β-cells (Efrat et al., 1995) were cultured at 37 °C, 5% CO2, 21% O2 in DMEM/High Glucose media (HyClone) supplemented with Penicillin (100 U/mL)/Streptomycin (100 μg/mL), Fetal Bovine Serum (10%), Glutamax (2 mM), doxycycline (1 g/mL), and sodium pyruvate (1 mM). Before the assay, cells were plated at 50 μL/well in 96-well format at 25,000 cells/well, and treated in quadruplicate 6 h after plating with test compound (0.169–10,000 nM) or DMSO, at a final volume of 100 uL/well. At 48 h post-treatment, cells were fixed for 15 min at room temperature with 2.7-4% paraformaldehyde by adding 8% PFA without removing media. Following fixation, cells were washed three times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), then treated with 4 μM Hoechst 33342 (Thermo) for 20 min, then washed twice with PBS. Cells were visualized with the Cellomics ArrayScan high content imaging system (ThermoFisher) and the nuclei quantified. Cells counts were normalized to the 8 DMSO control wells in each plate and fitted to 4-parameter inhibition curves in Prism (Graphpad) to obtain CC50’s.

4.1.7. Human Islet Replication

Human islets were obtained at a purity of 85-95% from either the University of Alberta IsletCore or the NIDDK IIDP distribution program as de-identified autopsy tissue and cultured with approval by the Stanford University Administrative Panel on Biosafety. Donor details are presented as supporting information (Supporting Information Table 7S). Upon receipt after 2-8 days in culture, islets were suspended for 12 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2, 21% O2 in sterile untreated petri dishes in DMEM/Low Glucose media (HyClone) supplemented with Penicillin (100 U/mL)/Streptomycin (100 μg/mL), heat-inactivated Fetal Bovine Serum (10%), and exendin-4 (20 nM). Islets were hand-picked and dispersed to single cells using a previously outlined protocol,24, 69 then plated in black 384-well plates that had been coated overnight with conditioned media from 804G bladder carcinoma cells. After 48 h incubation for adherence, media was replaced by gentle serial washing and dispersed islets were treated with compounds or DMSO in a final volume of 60 μL. At 48 h post-treatment, dispersed islets were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and antigen retrieved as described, and analyzed by antibody staining (1:300 anti-insulin, guinea pig (Dako), 1:250 anti-Ki-67, mouse (BD), 1:200 anti-guinea pig Cy5, 1:200 anti-mouse AF488) and Hoechst 33342 (4 μM) on the Cellomics ArrayScan system, β-cells, replication events, and replicating β-cells were assigned based on uniform cutoffs that were set up for each plate.

4.2. Molecular Modeling

4.2.1. Molecular Docking

The flexible binding pose of OTS167 in the DYRK1A active site was generated using Schrödinger’s Glide software (Schrödinger Release 2017-3: Glide, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2017) and the DYRK1A crystal structure PDB: 4MQ2.

4.2.2. Chemical Properties Calculator

The values for total polar surface area (TPSA), cLogP, and cLogD7.4 were calculated using MarvinSketch 16.12.5 software from ChemAxon (https://www.chemaxon.com).

4.3. Chemical Synthesis

Reactions were performed under ambient atmosphere unless otherwise noted. Qualitative TLC analysis was performed on 250 mm thick, 60 Å, glass backed, F254 silica (Silicycle, Quebec City, Canada). Visualization was accomplished with UV light and exposure to p-anisaldehyde or KMnO4 stain solutions followed by heating. All solvents used were ACS grade Sure-Seal, and all other reagents were used as received unless otherwise noted. Pd(dppf)Cl2•CH2Cl2 was purchased from Strem Chemical Company. OTS167 (5) was purchased from Cayman Chemical Company. The synthesis of amines that were not purchased is detailed in the supporting information. Flash chromatography was performed on a Teledyne Isco purification system using silica gel flash cartridges (SiliCycle®, SiliaSep™ 40-63 μm, 60Å). HPLC was performed on an Agilent 1260 Infinity preparative scale purification system using an Agilent PrepHT Zorbax Eclipse XDB-C18 reverse-phase column (21.2 × 250 mm). Structure determination was performed using 1H spectra that were recorded on a Bruker AV-500 spectrometer, and low-resolution mass spectra (ESI-MS) that were collected on a Shimadzu 20-20 ESI LCMS instrument using water with 0.1% formic acid as solvent A and acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid as solvent B. The programmed gradient was as follows 0–100% B (0–4 min), 100% B (4–5 min), 100–0% B (5–6 min). Final compound purity (Supporting Information Figure 6S) was determined using an Agilent 1200 Series HPLC fitted with a Zorbax Bonus RP Rapid Resolution HD 2.1 × 50 mm, 1.8 micron column using 98% water, 2% acetonitrile with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid as solvent A, and 10% water, 90% acetonitrile with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid as solvent B. The programmed gradient was as follows 5% B (0–0.2 min), 5–90% B (0.2–2.2 min), 90–98% B (2.2–2.5 min), 98–5% B (2.5–2.7 min). All final compounds had HPLC purities >95% with the exception of compounds 30 (94.2%) 35 (92.1%), 37 (94.1%), and 50 (94.9%). All final compound 1H spectra were consistent with the expected structures and purity.

4.3.1. Ethyl-6-(3,5-dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-(((trans)-4 ((dimethylamino)methyl) cyclohexyl) amino)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate trifluoroacetic acid salt 15:

Yellow solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 9.06 (s, 1H), 8.44 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 8.32 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 8.14 (s, 2H), 5.74–5.66 (m, 1H), 4.50 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.10 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 2.95 (s, 6H), 2.50–2.43 (comp m, 2H), 2.08–1.99 (comp m, 3H), 1.73–1.62 (comp m, 2H), 1.50–1.38 (comp m, 2H), 1.47 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C26H30Cl2N4O3 + H]+: 517.2 found 517.1.

4.3.2. 6-(3,5-Dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-(((trans)-4-((dimethylamino)methyl)cyclohexyl) amino)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carbonitrile trifluoroacetic acid salt 16:

Yellow solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.56 (s, 1H), 8.91 (s, 1H), 8.42 (s, 1H), 8.29 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 8.23 (s, 2H), 8.07 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 8.06–8.02 (m, 1H), 4.10–4.01 (m, 1H), 2.86–2.80 (comp m, 2H), 2.62 (d, J = 4.3 Hz, 6H), 2.02–1.95 (comp m, 2H), 1.75–1.60 (comp m, 2H), 1.68–1.61 (m, 1H), 1.60–1.50 (comp m, 2H), 1.05–0.94 (comp m, 2H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C24H25Cl2N5O + H]+: 470.1 found 470.1.

4.3.3. 6-(3,5-Dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-(((trans)-4-((dimethylamino)methyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide trifluoroacetic acid salt 17:

Off-white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 8.82 (s, 1H), 8.44 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.27 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.15 (s, 2H), 5.68–5.50 (m, 1H), 3.10 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 2.95 (s, 6H), 2.49–2.40 (comp m, 2H), 2.08–1.97 (comp m, 3H), 1.72–1.60 (comp m, 2H), 1.50–1.38 (comp m, 2H), 1.47–1.36 (comp m, 2H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C24H27Cl2N5O2 + H]+: 488.2 found 488.0.

4.3.4. 6-(3,5-Dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-(((trans)-4-((dimethylamino)methyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-N-methyl-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide trifluoroacetic acid salt 18:

Pale yellow solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 8.70 (br s, 1H), 8.44 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.28 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.16 (br s, 2H), 5.76–5.50 (m, 1H), 3.10 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 2.97 (s, 3H), 2.95 (s, 6H), 2.47–2.36 (comp m, 2H), 2.08–1.97 (comp m, 3H), 1.74–1.62 (comp m, 2H), 1.46–1.33 (comp m, 2H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C25H29Cl2N5O2 + H]+: 502.2 found 502.1.

4.3.5. 6-(3,5-Dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-(((trans)-4-((dimethylamino)methyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-N-ethyl-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide trifluoroacetic acid salt 19:

Pale yellow solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 8.72 (br s, 1H), 8.43 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.28 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.14 (br s, 2H), 5.76–5.47 (m, 1H), 3.45 (q, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 3.08 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 2.94 (s, 6H), 2.47–2.35 (comp m, 2H), 2.06–1.94 (comp m, 3H), 1.74–1.62 (comp m, 2H), 1.46–1.33 (comp m, 2H), 1.28 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M − H+) [C25H29Cl2N5O2 − H+]−: 514.2 found 514.1.

4.3.6. 6-(3,5-Dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-(((trans)-4-((dimethylamino)methyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-N-propyl-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide trifluoroacetic acid salt 20:

Beige solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 8.71 (br s, 1H), 8.42 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.28 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.14 (br s, 2H), 5.71–5.48 (m, 1H), 3.37 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 3.08 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 2.93 (s, 6H), 2.47–2.35 (comp m, 2H), 2.06–1.96 (comp m, 3H), 1.73–1.60 (comp m, 4H), 1.46–1.28 (comp m, 2H), 1.02 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C27H33Cl2N5O2 + H+]+: 530.2 found 530.2.

4.3.7. N-Butyl-6-(3,5-dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-(((trans)-4-((dimethylamino)methyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide trifluoroacetic acid salt 21:

Yellow solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 8.71 (br s, 1H), 8.44 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.28 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.17 (br s, 2H), 5.71–5.40 (m, 1H), 3.43 (t, J = 12 Hz, 2H), 3.10 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 2.95 (s, 6H), 2.47–2.37 (comp m, 2H), 2.07–1.97 (comp m, 3H), 1.74–1.62 (comp m, 4H), 1.52–1.44 (comp m, 2H), 1.44–1.32 (comp m, 2H), 1.02 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M − H+) [C28H35Cl2N5O2 − H+]−: 542.2 found 542.1.

4.3.8. 6-(3,5-Dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-(((trans)-4-((dimethylamino)methyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-N-pentyl-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide trifluoroacetic acid salt 22:

Yellow solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 8.71 (br s, 1H), 8.42 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.28 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.15 (br s, 2H), 5.76–5.40 (m, 1H), 3.41 (t, J = 12 Hz, 2H), 3.08 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 2.93 (s, 6H), 2.44–2.35 (comp m, 2H), 2.05–1.97 (comp m, 3H), 1.72–1.63 (comp m, 4H), 1.46–1.33 (comp m, 6H), 1.44–1.32 (comp m, 2H), 0.96 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C29H37Cl2N5O2 + H+]+: 558.2 found 558.2.

4.3.9. 6-(3,5-Dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-(((trans)-4-((dimethylamino)methyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-N-isobutyl-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide trifluoroacetic acid salt 23:

Beige solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 8.72 (br s, 1H), 8.43 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.28 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.14 (br s, 2H), 5.76–5.44 (m, 1H), 3.24 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 3.08 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 2.93 (s, 6H), 2.44–2.35 (comp m, 2H), 2.05–1.92 (comp m, 4H), 1.72–1.59 (comp m, 2H), 1.45–1.30 (comp m, 2H), 1.44–1.32 (comp m, 2H), 1.01 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 6H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C28H35Cl2N5O2 + H+]+: 544.2 found 544.2.

4.3.10. 6-(3,5-Dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-(((trans)-4-((dimethylamino)methyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-N-isopentyl-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide trifluoroacetic acid salt 24:

Yellow solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 8.70 (br s, 1H), 8.41 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.27 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.13 (br s, 2H), 5.72–5.44 (m, 1H), 3.44 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 3.08 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 2.93 (s, 6H), 2.46–2.32 (comp m, 2H), 2.06–1.95 (comp m, 3H), 1.77–1.59 (comp m, 3H), 1.45–1.28 (comp m, 2H), 1.44–1.32 (comp m, 2H), 0.99 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 6H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C29H37Cl2N5O2 + H+]+: 558.2 found 558.2.

4.3.11. (6-(3,5-Dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-(((trans)-4-((dimethylamino)methyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-1,5-naphthyridin-3-yl)(morpholino)methanone trifluoroacetic acid salt 25:

Off-white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 8.54 (s, 1H), 8.49 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.33 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.31 (s, 2H), 4.01–3.43 (comp m, 8H), 3.10 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 2.94 (s, 6H), 2.34–2.08 (comp m, 2H), 2.07–1.92 (comp m, 3H), 1.90–1.70 (comp m, 2H), 1.30–1.13 (comp m, 2H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C28H33Cl2N5O3 + H+]+: 558.2 found 558.1.

4.3.12. 6-(3,5-Dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-(((trans)-4-((dimethylamino)methyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-N,N-dimethyl-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide trifluoroacetic acid salt 26:

White solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.81 (m, 1H), 9.22 (br s, 1H), 8.59 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.56 (s, 1H), 8.42 (s, 2H), 8.31 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 3.11–2.95 (comp m, 8H), 2.80 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 6H), 2.03–1.95 (comp m, 2H), 1.94–1.85 (comp m, 2H), 1.83–1.66 (comp m, 3H), 1.06–0.95 (comp m, 2H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C26H31Cl2N5O2 + H+]+: 516.2 found 516.0.

4.3.13. Ethyl 6-(3,5-dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-((4-((dimethylamino)methyl)phenyl)amino)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate trifluoroacetic acid salt 27:

Yellow solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 9.12 (s, 1H), 8.42 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.35 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.54 (s, 2H), 7.49 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 4.43 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 4.42 (s, 2H), 2.88 (s, 6H), 1.44 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C26H24Cl2N4O3 + H+]+: 511.1 found 511.0.

4.3.14. Ethyl 4-(((trans)-4-(aminomethyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-6-(3,5-dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate trifluoroacetic acid salt 28:

beige solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 9.05 (s, 1H), 8.44 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.31 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 8.15 (s, 2H), 5.75 (s, 1H), 4.50 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 2.91 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.48–2.41 (comp m, 2H), 2.11–2.04 (comp m, 2H), 1.86–1.76 (m, 1H), 1.67–1.57 (comp m, 2H), 1.47 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 1.46–1.35 (comp m, 2H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C24H26Cl2N4O3 + H+]+: 489.1 found 489.0.

4.3.14. Ethyl 4-(((trans)-4-(acetamidomethyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-6-(3,5-dichloro-4-hydroxy phenyl)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate trifluoroacetic acid salt 29:

Beige solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 9.04 (s, 1H), 8.47 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.31 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.13 (s, 2H), 4.51 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.15 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 2.45–2.36 (comp m, 2H), 2.04– 1.98 (comp m, 2H), 1.97 (s, 3H), 1.63–1.53 (comp m, 2H), 1.48 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 1.40–1.29 (m, 2H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C26H28Cl2N4O4 + H+]+: 531.1 found 531.1.

4.3.15. N-(((Trans)-4-((6-(3,5-ichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-3-(hydroxymethyl)-1,5-naphthyridin-4-yl)amino)cyclohexyl)methyl)acetamide trifluoroacetic acid salt 30:

Yellow solid 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.56 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.50 (s, 1H), 8.30 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.25 (comp m, 2H), 7.87 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 5.84 (s, 1H), 4.69 (s, 2H), 2.95 (t, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H), 2.16–2.06 (comp m, 2H), 1.91–1.82 (comp m, 2H), 1.81 (s, 3H), 1.67–1.55 (comp m, 2H), 1.52–1.42 (comp m, 1H), 1.18–1.07 (comp m, 2H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C24H26Cl2N4O3 + H+]+: 489.1 found 489.2.

4.3.16. Ethyl 6-(3,5-dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-(((trans)-4-(hydroxymethyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate trifluoroacetic acid salt 31:

Gray solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 9.03 (s, 1H), 8.46 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 8.31 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 8.12 (s, 2H), 5.73–5.63 (m, 1H), 4.50 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.48 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 2.45–2.36 (comp m, 2H), 2.08–2.00 (comp m, 2H), 1.68–1.52 (comp m, 3H), 1.47 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 1.37–1.24 (comp m, 2H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C24H25Cl2N3O4 + H+]+: 490.1 found 490.1.

4.3.17. Ethyl 6-(3,5-dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-(((trans)-4-methylcyclohexyl)amino)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate 32:

Tan solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.73 (s, 1H), 9.50 (s, 1H), 8.91 (s, 1H), 8.33 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 8.23–8.13 (comp m, 3H), 5.34 (s, 1H), 4.34 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 2.24–2.11 (m, 2H), 1.83–1.72 (comp m, 2H), 1.52–1.40 (m, 1H), 1.40–1.27 (comp m, 5H), 1.28–1.14 (comp m, 2H), 0.94 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 3H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C24H25Cl2N3O3 + H+]+: 474.1 found 474.2.

4.3.18. Ethyl 4-(((trans)-4-aminocyclohexyl)amino)-6-(3,5-dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate trifluoroacetic acid salt 33:

White solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 9.06 (s, 1H), 8.41 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.32 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.08 (s, 2H), 5.44 (s, 1H), 4.49 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.60–2.52 (comp m, 2H), 2.28–2.20 (comp m, 2H), 1.82–1.64 (comp m, 4H), 1.46 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C23H24Cl2N4O3 + H+]+: 475.1 found 475.2.

4.3.19. Ethyl 6-(3,5-dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-((1-methylpiperidin-4-yl)amino)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate trifluoroacetic acid salt 34:

Off-white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 9.12 (s, 1H), 8.45 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.38 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 8.07 (s, 2H), 5.86 (s, 1H), 4.50 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.83–3.73 (comp m, 2H), 3.27–3.19 (m, 1H), 2.98 (s, 3H), 2.71–2.59 (comp m, 2H), 2.48 (m, 1H), 2.14–2.06 (comp m, 2H), 1.46 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M − H+) [C23H24Cl2N4O3 − H+]−: 473.1 found 473.1.

4.3.20. Ethyl 6-(3,5-dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-(piperidin-1-yl)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate trifluoroacetic acid salt 35:

Yellow-orange solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 8.82 (s, 1H), 8.42 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 8.31 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 8.11 (s, 2H), 4.48 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 4.16–4.06 (comp m, 4H), 2.03–1.89 (comp m, 6H), 1.45 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C22H21Cl2N3O3 + H+]+: 446.1 found 446.0.

4.3.21. Ethyl 6-(3,5-dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-(4-methylpiperidin-1-yl)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate trifluoroacetic acid salt 36:

Yellow-orange solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 8.84 (s, 1H), 8.46 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.33 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.17 (s, 2H), 4.72–4.59 (comp m, 2H), 4.48 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.69–3.59 (comp m, 2H), 2.06–1.98 (comp m, 3H), 1.73–1.62 (comp m, 2H), 1.45 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 1.07 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 3H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C23H23Cl2N3O3 + H+]+: 460.1 found 460.2.

4.3.22. Ethyl 6-(3,5-dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-morpholino-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate trifluoroacetic acid salt 37:

Yellow-orange solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 8.91 (s, 1H), 8.47 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.37 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.08 (s, 2H), 4.50 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 4.25–4.17 (comp m, 4H), 4.12–4.02 (comp m, 4H), 1.46 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C21H19Cl2N3O4 + H+]+: 448.1 found 448.0.

4.3.23. Ethyl 6-(3,5-dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-(piperazin-1-yl)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate trifluoroacetic acid salt 38:

Yellow-orange solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 9.01 (s, 1H), 8.41 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.36 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.09 (s, 2H), 4.50 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 4.18–4.08 (comp m, 4H), 3.65–3.57 (comp m, 4H), 1.47 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C21H20Cl2N4O3 + H+]+: 447.1 found 447.0.

4.3.24. Ethyl 6-(3,5-dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-(((trans)-4-(morpholinomethyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate trifluoroacetic acid salt 39:

Yellow solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 9.05 (s, 1H), 8.43 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.32 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.09 (s, 2H), 5.72–5.64 (m, 1H), 4.49 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 4.15–3.75 (comp m, 4H), 3.65–3.45 (comp m, 2H), 3.25–3.15 (comp m, 2H), 3.12 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 2.48–2.38 (comp m, 2H), 2.12–2.02 (comp m, 3H), 1.73–1.60 (comp m, 2H), 1.50–1.36 (comp m, 2H) 1.46 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C28H32Cl2N4O4 + H+]+: 559.2 found 559.1.

4.3.25. N-Butyl-6-(3,5-dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-(((trans)-4-(morpholinomethyl)cyclohexyl) amino)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide trifluoroacetic acid salt 40:

Beige solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 8.71 (s, 1H), 8.44 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.28 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.16 (s, 2H), 5.74–5.69 (m, 1H), 4.15–3.75 (comp m, 4H), 3.60–3.48 (comp m, 2H), 3.42 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 3.25–3.18 (comp m, 2H), 3.13 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 2.46–2.36 (m, 2H), 2.10–2.00 (comp m, 3H), 1.72–1.62 (comp m, 4H), 1.50–1.35 (comp m, 4H), 1.01 (t, J = 1.4 Hz, 3H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C30H37Cl2N5O3 + H+]+: 586.2 found 586.2

4.3.26. Ethyl 4-(((trans)-4-carbamoylcyclohexyl)amino)-6-(3,5-dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate trifluoroacetic acid salt 41:

Beige solid.1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 9.04 (s, 1H), 8.44 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.30 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.08 (s, 2H), 5.55 (s, 1H), 4.51 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 2.52–2.45 (comp m, 2H), 2.40 (ddt, J = 12.0, 7.1, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 2.13–2.05 (comp m, 2H), 1.90–1.79 (comp m, 2H), 1.69–1.58 (comp m, 2H), 1.48 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C24H24Cl2N4O4 + H+]+: 503.1 found 503.0.

4.3.27. Ethyl 6-(3,5-dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-(((trans)-4-(dimethylcarbamoyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate 42:

Yellow solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-ddine-3-carboxylate nJ = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 8.23 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 8.17 (s, 2H), 5.30 (s, 1H), 4.36 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.03 (s, 3H), 2.81 (s, 3H), 2.70 (tt, J = 11.7, 3.5 Hz, 1H), 2.32–2.22 (comp m, 2H), 1.84–1.76 (comp m, 2H), 1.68–1.58 (comp m, 2H), 1.54–1.42 (comp m, 2H), 1.37 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C26H28Cl2N4O4 + H+]+: 531.1 found 531.1.

4.3.28. N-Butyl-4-(((trans)-4-carbamoylcyclohexyl)amino)-6-(3,5-dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide trifluoroacetic acid salt 43:

White solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 8.67 (s, 1H), 8.44 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.25 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.15 (s, 2H), 5.50 (s, 1H), 3.43 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 2.45–2.32 (comp m, 3H), 2.11–2.03 (comp m, 2H), 1.84–1.72 (comp m, 2H), 1.70–1.62 (comp m, 4H), 1.47 (h, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 1.01 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C26H29Cl2N5O3 + H+]+: 530.2 found 530.3.

4.3.29. (Trans)-4-((6-(3,5-dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-3-(hydroxymethyl)-1,5-naphthyridin-4-yl)amino)cyclohexane-1-carboxamide trifluoroacetic acid salt 44:

Yellow solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 8.40 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.36 (s, 1H), 8.26 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.16 (s, 2H), 4.83 (s, 2H), 2.42–2.31 (comp m, 3H), 2.11–2.03 (comp m, 2H), 1.81–1.65 (comp m, 4H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C22H22Cl2N4O3 + H+]+: 461.1 found 461.1.

4.3.30. (Trans)-4-((3-acetyl-6-(3,5-dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-1,5-naphthyridin-4-yl)amino)cyclohexane-1-carboxamide hydrogen chloride salt 45:

White solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.02 (s, 1H), 8.99 (s, 1H), 8.36 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 8.21 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 8.15 (s, 2H), 7.18 (s, 1H), 6.68 (s, 1H), 5.28 (s, 1H), 2.68 (s, 3H), 2.32–2.24 (comp m, 2H), 2.17 (tt, J = 12.0, 3.4 Hz, 1H), 1.94–1.86 (comp m, 2H), 1.66–1.55 (comp m, 2H), 1.41–1.30 (comp m, 2H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C23H22Cl2N4O3 + H+]+: 473.1 found 473.0.

4.3.31. Ethyl 6-(3,5-dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-(((trans)-4-(morpholine-4-carbonyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate 46:

Beige solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 9.03 (s, 1H), 8.44 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.30 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.07 (s, 2H), 5.58-5.52 (m, 1H), 4.50 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.73–3.56 (comp m, 8H), 2.82 (tt, J = 11.6, 3.5 Hz, 1H), 2.50–2.43 (comp m, 2H), 2.02–1.93 (comp m, 2H), 1.92–1.81 (comp m, 2H), 1.75-1.63 (comp m, 2H), 1.47 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C28H30Cl2N4O5 + H+]+: 573.2 found 573.1.

4.3.32. 2-((Trans)-4-((6-(3,5-dichloro-4-hydroxyphenyl)-3-(hydroxymethyl)-1,5-naphthyridin-4-yl)amino)cyclohexyl)acetamide 48:

White solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 8.40 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 8.33 (s, 1H), 8.25 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 8.16 (s, 2H), 5.49 (m, 1H), 4.81 (s, 2H), 2.35–2.24 (comp m, 2H), 2.21 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 2.03–1.94 (comp m, 2H), 1.95–1.85 (m, 1H), 1.75–1.60 (comp m, 2H), 1.42–1.27 (comp m, 2H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C23H24Cl2N4O3 + H+]+: 475.2 found 475.1.

4.3.33. Ethyl 4-(((trans)-4-(2-amino-2-oxoethyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-6-(3,5-dichloro-4-hydroxy phenyl)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate 49:

White solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 9.1 (s, 1H), 8.42 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 8.28 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 8.09 (s, 2H), 5.58 (m, 1H), 4.49 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 2.41–2.34 (comp m, 2H), 2.22 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 2.03–1.94 (comp m, 2H), 1.95–1.86 (m, 1H), 1.66–1.54 (comp m, 2H), 1.46 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 1.42–1.32 (comp m, 2H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C25H26Cl2N4O4 + H]+: 517.1 found 517.1.

4.3.34. Ethyl 6-(3,5-dichlorophenyl)-4-(((trans)-4-((dimethylamino)methyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate trifluoroacetic acid salt 50:

White solid. ‘HNMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 9.10 (s, 1H), 8.53 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 8.41 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 8.14 (s, 2H), 7.69 (s, 1H), 5.74–5.62 (m, 1H), 4.51 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 3.08 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H), 2.94 (s, 6H), 2.50–2.41 (comp m, 2H), 2.09–1.99 (comp m, 3H), 1.74–1.64 (comp m, 2H), 1.47 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 1.45–1.35 (comp m, 2H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C26H30Cl2N4O2 + H]+: 501.2, found 501.3.

4.3.35. Ethyl 4-(((trans)-4-((dimethylamino)methyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-6-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate trifluoroacetic acid salt 51:

Yellow-orange solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 9.02 (s, 1H), 8.41 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.27 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.00 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 7.00 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 5.73–5.64 (m, 1H), 4.49 (q, J= 12 Hz, 2H), 3.11 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 2.52–2.44 (comp m, 2H), 2.06–1.96 (comp m, 3H), 1.72–1.62 (comp m, 2H), 1.46 (t, J= 7.2 Hz, 3H), 1.41–1.29 (comp m, 2H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C26H32N4O3 + H]+: 449.2, found 449.3.

4.3.36. Ethyl 4-(((trans)-4-((dimethylamino)methyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-6-(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethyl phenyl)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate trifluoroacetic acid salt 52:

Yellow solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 9.01 (s, 1H), 8.39 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.25 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 7.73 (s, 2H), 5.82–5.73 (m, 1H), 4.49 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.07 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 2.94 (s, 6H), 2.51–2.44 (comp m, 2H), 2.36 (s, 6H), 2.06–1.98 (comp m, 3H), 1.71–1.60 (comp m, 2H), 1.46 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 1.40–1.30 (comp m, 2H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C28H36N4O3 + H]+: 477.3, found 477.4.

4.3.37. Ethyl 6-(4-aminophenyl)-4-(((trans)-4-((dimethylamino)methyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate trifluoroacetic acid salt 53:

Orange solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 8.93 (s, 1H), 8.36 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H), 8.20 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H) 7.91 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 6.85 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 2H), 5.78–5.68 (m, 1H), 4.48 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 3.11 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H), 2.94 (s, 6H), 2.50–2.43 (comp m, 2H), 2.06–1.98 (comp m, 3H), 1.70–1.61 (comp m, 2H), 1. 44 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 1.40–1.31 (comp m, 2H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C26H33N5O2 + H]+: 448.3, found 448.3.

4.3.38. 4-(8-(((Trans)-4-((dimethylamino)methyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-7-(ethoxycarbonyl)-1,5-naphthyridin-2-yl)benzoic acid trifluoroacetic acid salt 54:

White solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 9.09 (s, 1H), 8.56 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 8.39 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H) 8.30–8.18 (comp m, 4H), 5.66–5.58 (m, 1H), 4.50 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 3.12 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 2.94 (s, 6H), 2.54–2.46 (comp m, 2H), 2.05–1.96 (comp m, 3H), 1.74–1.63 (comp m, 2H), 1.47 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 1.40–1.28 (comp m, 2H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C27H32N4O4 + H]+: 477.2, found 477.2.

4.3.39. Ethyl 6-(4-carbamoylphenyl)-4-(((trans)-4-((dimethylamino)methyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate trifluoroacetic acid salt 55:

White solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 9.09 (s, 1H), 8.56 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 8.39 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H) 8.23 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 8.12 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H ), 5.69–5.61 (m, 1H), 4.51 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 3.12 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 2.94 (s, 6H), 2.53–2.45 (comp m, 2H), 2.5–1.96 (comp m, 3H), 1.74–1.63 (comp m, 2H), 1.47 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 1.40–1.28 (comp m, 2H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C27H33N5O3 + H]+: 476.3 found 476.2.

4.3.40. Ethyl 4-(((trans)-4-((dimethylamino)methyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-6-(pyridin-4-yl)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate trifluoroacetic acid salt 56:

White solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 9.12 (s, 1H), 8.98–8.95 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H), 8.67 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 8.50 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 8.40 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H), 5.54–5.48 (m, 1H), 4.48 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 3.10 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H), 2.91 (s, 6H), 2.47–2.41 (comp m, 2H), 2.03–1.95 (comp m, 3H), 1.73–1.62 (comp m, 2H) 1.44 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 1.35–1.25 (comp m, 2H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C25H31N5O2 + H]+: 434.5 found 434.1.

4.3.41. Ethyl 4-(((trans)-4-((dimethylamino)methyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-6-(2-methylpyridin-4-yl)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate trifluoroacetic acid salt 57:

Amber solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 9.12 (s, 1H), 8.87–8.83 (m, 1H), 8.66 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 8.49 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 8.33 (s, 1H), 8.28–8.22 (m, 1H), 5.57–5.47 (m, 1H), 4.48 (q, J = 12 Hz, 2H), 3.08 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 2.91 (s, 6H), 2.84 (s, 3H), 2.49–2.41 (comp m, 2H), 2.05–1.95 (comp m, 3H), 1.73–1.62 (comp m, 2H) 1.45 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 1.35–1.25 (comp m, 2H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C26H33N5O2 + H]+: 448.3 found 448.3.

4.3.42. Ethyl 4-(((trans)-4-((dimethylamino)methyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-6-(2,6-dimethylpyridin-4-yl)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate trifluoroacetic acid salt 58:

Orange solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 9.12 (s, 1H), 8.66 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 8.51 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 8.29 (s, 2H), 5.53–5.44 (m, 1H), 4.48 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.05 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 2.90 (s, 6H), 2.87 (s, 6H), 2.47–2.40 (comp m, 2H), 2.05–1.95 (comp m, 3H), 1.73–1.62 (comp m, 2H) 1.44 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 1.30–1.18 (comp m, 2H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C27H35N5O2 + H]+: 462.3 found 462.3.

4.3.43. Ethyl 6-(2-aminopyridin-4-yl)-4-(((trans)-4-((dimethylamino)methyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate trifluoroacetic acid salt 59:

Off-white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 9.13 (s, 1H), 8.50 (ab q, JAB = 8.9 Hz, vAB = 4.2 Hz, 2H), 8.13 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (s, 1H), 7.50 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 5.50–5.40 (m, 1H), 4.50 (q, J = 12 Hz, 2H), 3.09 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 2.93 (s, 6H), 2.47–2.40 (comp m, 2H), 2.04–1.95 (comp m, 3H), 1.74–1.61 (comp m, 2H), 1.47 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 1.35–1.23 (comp m, 2H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C25H32N6O2 + H]+: 449.3, found 449.2.

4.3.44. 6-(2-Aminopyridin-4-yl)-4-(((trans)-4-((dimethylamino)methyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-N-ethyl-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxamide 60:

yellow solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4, probe heated to 55 °C to resolve rotamers) δ 8.93 (s, 1H), 8.75–8.64 (comp m, 2H), 8.29 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H), 7.95–7.74 (comp m, 2H), 3.67 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 3.29 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 3.13 (s, 6H), 2.62–2.48 (comp m, 2H), 2.26–2.13 (comp m, 3H), 1.95–1.83 (comp m, 2H), 1.53–1.42 (comp m, 5H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C25H33N7O - H+]−: 446.3 found 446.2.

4.3.45. Ethyl 4-(((trans)-4-((dimethylamino)methyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-6-(2-hydroxypyridin-4-yl)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate trifluoroacetic acid salt 61:

White solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 9.11 (s, 1H), 8.46 (ab q, JAB = 8.9 Hz, vAB = 31.4Hz, 2H), 7.70 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 7.26 (s, 1H), 7.06 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 5.58–5.49 (m, 1H), 4.50 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.11 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 2.94 (s, 6H), 2.48–2.40 (comp m, 2H), 2.05–1.94 (comp m, 3H), 1.72–1.62 (comp m, 2H), 1.46 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 1.43–1.32 (comp m, 2H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C25H31N5O3 + H]+: 450.2, found 450.2.

4.3.46. Ethyl 4-(((trans)-4-((dimethylamino)methyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-6-(6-hydroxypyridin-3-yl)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate trifluoroacetic acid salt 62:

yellow solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 9.05 (s, 1H), 8.38–8.30 (comp m, 4H), 6.76 (d, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H), 5.58–5.50 (m, 1H), 4.49 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.12 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H), 2.94 (s, 6H), 2.48–2.41 (comp m, 2H), 2.06–1.97 (comp m, 2H), 1.72–1.61 (comp m, 2H), 1.46 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 1.38–1.27 (comp m, 2H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C25H31N5O3 + H]+: 450.2, found 450.3.

4.3.47. Ethyl 6-(2-aminopyridin-4-yl)-4-(((trans)-4-(morpholinomethyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate trifluoroacetic acid salt 63:

Off-white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 9.12 (s, 1H), 8.51–8.43 (comp m, 2H), 8.13 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 7.58 (s, 1H), 7.54–7.48 (m, 1H), 5.46 (s, 1H), 4.50 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 4.16–3.76 (comp m, 4H), 3.60–3.48 (comp m, 2H), 3.14 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 2.47–2.38 (comp m, 2H), 2.10–2.00 (comp m, 3H), 1.70–1.59 (comp m, 2H), 1.47 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 1.38–1.27 (comp m, 2H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C27H34N6O3 + H+]+: 491.2 found 491.2.

4.3.48. Ethyl 6-(2-aminopyridin-4-yl)-4-(((trans)-4-(piperidin-1-ylmethyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate trifluoroacetic acid salt 64:

Off-white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 9.12 (s, 1H), 8.48 (q, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 8.13 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (s, 1H), 7.51 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 5.45 (s, 1H), 4.50 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.59 (d, J = 12.3 Hz, 2H), 3.06 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H), 3.01–2.90 (comp m, 2H), 2.47–2.39 (comp m, 2H), 2.07–1.91 (comp m, 5H), 1.90–1.80 (comp m, 3H), 1.72–1.61 (comp m, 2H), 1.59–1.52 (m, 1H), 1.47 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H), 1.37–1.25 (comp m, 2H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C28H36N6O2 + H+]+: 489.3 found 489.2.

4.3.49. Ethyl 6-(2-aminopyridin-4-yl)-4-(((trans)-4-(pyrrolidin-1-ylmethyl)cyclohexyl)amino)-1,5-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate trifluoroacetic acid salt 65:

Off-white solid. 1H NMR (500 MHz, Methanol-d4) δ 9.13 (s, 1H), 8.49 (q, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 8.13 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (s, 1H), 7.50 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 5.45 (s, 1H), 4.50 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 3.77–3.68 (comp m, 2H), 3.17 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.15–3.07 (comp m, 2H), 2.48–2.39 (comp m, 2H), 2.24–2.12 (comp m, 2H), 2.11–2.01 (comp m, 4H), 2.00–1.92 (m, 1H), 1.72–1.60 (comp m, 2H), 1.47 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 1.37–1.24 (comp m, 2H); LRMS m/z calc’d for (M + H+) [C27H34N6O2 + H+]+: 475.3 found 475.2.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Justin DuBois (Stanford University) for the generous use of his laboratory space, chemical supplies and equipment.

Funding Sources

PAA, TMH, YA, HPM, BY, MC, GM and JPA were supported by NIH Grant NIDDK R01DK101530. PAA was supported by the Endocrinology Training grant (T32DK007217). TMH was supported by the Stanford ChEM-H Chemistry/Biology interface Predoctoral Training Program (T32GM120007) and Stanford Bio-X Interdisciplinary Graduate Fellowship (GM120007). YA was supported by the Child Health Research Institute at Stanford (UL1TR001085). HPM was supported by the Molecular Pharmacology Training Grant (T32GM113854). BY was supported by the Bio-X summer research program. MC was supported by the ChEM-H Undergraduate Scholars Program. GM was supported by the NIH STEP-UP program (NIDDK R25DK07838). MS was supported by Stanford ChEM-H. Execution of this work was supported by the Stanford Diabetes Center Islet Core (P30DK116074), Friedenrich Diabetes Fund, and SPARK Translational Research Program (UL1TR001085, JPA).

ABBREVIATIONS

- Abl1

Ableson murine leukemia viral oncogene homolog 1

- AURKA

aurora kinase A

- AURKB

aurora kinase B

- BUB1

Mitotic checkpoint serine/threonine-protein kinase BUB1

- CDK7

Cyclin-dependent kinase 7

- CHEK2

checkpoint kinase 2

- EC50

Half-maximal effective concentration

- ECmin

minimal effective concentration

- IC50

Half-maximal inhibitory concentration

- HPLC

High-performance liquid chromatography

- Kd

Dissociation constant

- KIT

KIT proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase

- MAP2K1/MEK1

Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1

- MAP2K2/MEK2

Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 2

- MAP3K3

mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 3

- MAST1

microtubule-associated serine/threonine kinase 1

- PDGFRB/A

platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta/alpha

- PIM1/2/3

Pim-1/2/3 Proto-Oncogene, Serine/Threonine Kinase

- PLK4

Serine/threonine-protein kinase PLK4, polo-like kinase 4

- RET

RET receptor tyrosine kinase

- T1D

type 1 diabetes

- T2D

type 2 diabetes

- TLC

thin layer chromatography

- UV

ultraviolet

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supporting Information.

The following files are available free of charge.

Linear Correlation for R-Luc CC50 vs CC50, Compound 56 Combination Toxicity dose curves, Human β-cell replication dose curves, Kinome Profile for OTS167 5 & Compound 56, R7T1 Toxicity data, Materials and Methods (Synthesis), Compound Synthesis, 1H NMR Spectra (PDF)

Human Islet donor information (xlxs)

Molecular Formula Strings (CSV)

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.DiMeglio LA; Evans-Molina C; Oram RA Type 1 diabetes. Lancet 2018, 391, 2449–2462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chatterjee S; Khunti K; Davies MJ Type 2 diabetes. Lancet 2017, 389, 2239–2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Damond N; Engler S; Zanotelli VRT; Schapiro D; Wasserfall CH; Kusmartseva I; Nick HS; Thorel F; Herrera PL; Atkinson MA; Bodenmiller B A Map of Human Type 1 Diabetes Progression by Imaging Mass Cytometry. Cell metabolism 2019, 29, 755–768.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alejandro EU; Gregg B; Blandino-Rosano M; Cras-Meneur C; Bernal-Mizrachi E Natural history of beta-cell adaptation and failure in type 2 diabetes. Molecular aspects of medicine 2015, 42, 19–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dor Y; Brown J; Martinez OI; Melton DA Adult pancreatic beta-cells are formed by self-duplication rather than stem-cell differentiation. Nature 2004, 429, 41–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meier JJ; Butler AE; Saisho Y; Monchamp T; Galasso R; Bhushan A; Rizza RA; Butler PC Beta-cell replication is the primary mechanism subserving the postnatal expansion of beta-cell mass in humans. Diabetes 2008, 57, 1584–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saisho Y; Butler AE; Manesso E; Elashoff D; Rizza RA; Butler PC beta-cell mass and turnover in humans: effects of obesity and aging. Diabetes care 2013, 36, 111–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chera S; Baronnier D; Ghila L; Cigliola V; Jensen JN; Gu G; Furuyama K; Thorel F; Gribble FM; Reimann F; Herrera PL Diabetes recovery by age-dependent conversion of pancreatic delta-cells into insulin producers. Nature 2014, 514, 503–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lam CJ; Cox AR; Jacobson DR; Rankin MM; Kushner JA Highly Proliferative Alpha-Cell Related Islet Endocrine Cells in Human Pancreata. Diabetes 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Butler AE; Dhawan S; Hoang J; Cory M; Zeng K; Fritsch H; Meier JJ; Rizza RA; Butler PC Beta-cell deficit in Obese Type 2 Diabetes, a Minor Role of Beta-cell Dedifferentiation and Degranulation. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 2015, jc20153566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butler AE; Cao-Minh L; Galasso R; Rizza RA; Corradin A; Cobelli C; Butler PC Adaptive changes in pancreatic beta cell fractional area and beta cell turnover in human pregnancy. Diabetologia 2010, 53, 2167–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nichols RJ; New C; Annes JP Adult tissue sources for new beta cells. Translational research : the journal of laboratory and clinical medicine 2014, 163, 418–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Assche FA; Aerts L; De Prins F A morphological study of the endocrine pancreas in human pregnancy. British journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 1978, 85, 818–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ritzel RA; Butler AE; Rizza RA; Veldhuis JD; Butler PC Relationship between beta-cell mass and fasting blood glucose concentration in humans. Diabetes care 2006, 29, 717–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Navarro G; Abdolazimi Y; Zhao Z; Xu H; Lee S; Armstrong NA; Annes JP Genetic Disruption of Adenosine Kinase in Mouse Pancreatic beta-Cells Protects Against High-Fat Diet-Induced Glucose Intolerance. Diabetes 2017, 66, 1928–1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]