Abstract

Socioeconomic disadvantage is extremely common among women with depressive symptoms presenting for women’s health care. While social stressors related to socioeconomic disadvantage can contribute to depression, health care tends to focus on patients’ symptoms in isolation of context. Health care providers may be more effective by addressing issues related to socioeconomic disadvantage. It is imperative to identify common challenges related to socioeconomic disadvantage, as well as sources of resilience. In this qualitative study, we interviewed 20 women’s health patients experiencing depressive symptoms and socioeconomic disadvantage about their views of their mental health, the impact of social stressors, and their resources and skills. A Consensual Qualitative Research approach was used to identify domains consisting of challenges and resiliencies. We applied the socioecological model when coding the data and identified cross-cutting themes of chaos and distress, as well as resilience. These findings suggest the importance of incorporating context in the health care of women with depression and socioeconomic disadvantage.

Keywords: women’s health patients, socioeconomic factors, depression, qualitative research

The World Health Organization defines social determinants of health as “the circumstances in which people are born, grow up, live, work and age, and the systems put in place to deal with illness” (Marmot et al., 2008). Examples of social determinants of health include substandard housing, food insecurity, and poor education and employment opportunities (Marmot et al., 2008). Social determinants of health are closely tied to socioeconomic disadvantage, which is linked to higher lifetime and 12-month incidences of disorders such as major depression (Kessler et al., 1994; Messias, Eaton & Grooms, 2011; Muntaner, Eaton, Miech, & O’Campo, 2004). Women of reproductive age are at disproportionate risk for depression and negative social determinants of health such as poverty, single parenthood status, and intimate partner victimization (DeNavas-Walt, Carmen, & Smith, 2012; Goodman, Smyth, Borges, & Singer, 2009; Miranda & Bruce, 2002). Low income, education level, and socioeconomic status have all been found to be risk factors for postpartum depression specifically (Silva, Loureiro, & Cardoso, 2016). Among low income mothers, worries about providing for children—access to food, paying bills (rent, electricity), medical care, and stable housing—are linked to increased depression (Goyal, Gay, & Lee, 2010; Logsdon, Hines-Martin, & Rakestraw, 2009; Heflin & Iceland, 2009).

Many women who are socioeconomically disadvantaged and experiencing depressive symptoms must navigate myriad daily intrapersonal, interpersonal, and structural challenges. These daily challenges can present considerable barriers to engaging in effective depression treatment (Grote, Zuckoff, Swartz, Bledsoe, & Geibel, 2007; Levy & O’Hara, 2010; Myors, Johnson, Cleary, & Schmied, 2015). Given these barriers to depression treatment for women of reproductive age, evidence supports integrating mental health care in ob/gyn settings where women seek care (Poleshuck & Woods, 2014; Melville et al., 2014; Bhat, Reed, & Unützer, 2017). In addition to considering where patients are most likely to present, it is important to consider whether traditional treatment paradigms for women experiencing depression and socioeconomic disadvantage fit their lives. Although evidence-based depression treatments, such as antidepressants and psychotherapy, can be highly effective, they may not match women’s most pressing priorities, for example accessing basic needs or safety concerns, and this mismatch may impede engagement (Grote et al., 2007; Pugach & Goodman, 2015).

Risk factors for depression extend well beyond individual circumstances to include broader society level considerations. Feminist scholarship has shown that disadvantaged women are subject to multiple social and cultural oppressions that are sustained by societal values, policies and systems, which negatively impact their mental well-being (Anderson, 2014; Manne, 2018; Vera-Gray, 2017). There is much at the societal level that contributes not only to women’s depression, but also their experiences of powerlessness and systems mistrust (Goodman, Pugach, Skolnik, & Smith, 2013; Belle & Doucet, 2003; Smith, Chambers, & Bratini, 2009). Such mistrust may extend to the patient/provider relationship, particularly if a patient feels either stigmatized or that their provider does not understand the larger societal and structural oppressions that impact their lived experience. Individuals in positions of greater social power must be explicitly open to hearing about to the experiences of those with less social power to build an authentic relationship and obtain accurate information (Jordan, 2008; Jordan, 2010). The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology now recommends the routine screening and addressing of social determinants of health as part of the delivery of women’s health care (ACOG Committee Opinion 729, 2018), encouraging providers to listen carefully, with authentic interest, to understand relevant information about a patient’s social determinants of health.

To meet patients’ needs, it is critical for health care providers to understand patients’ own priorities and values and to consider the full social context of patients’ lives. Although this is true for all patients, there are also specific reasons to focus on the needs of women with socioeconomic disadvantage who are struggling with depression. Women with depression must overcome the stigma associated with mental health problems (Corrigan, 2004; Goodman, 2009), and women of reproductive age are often responsible for the healthy physical and emotional development of children despite limited financial and emotional resources (Goyal et. al., 2010; Heflin & Iceland, 2009; Logsdon et al., 2009). As already described, women’s voices often are not heard or are invalidated, and those with depression are, by definition, in less of a position to advocate for themselves. Eliciting and incorporating each woman’s priorities into treatment planning is an important way to acknowledge the context of difficulties in their lives, show respect for their values and priorities, and respond to their depression with meaningful care. In addition to assessing and incorporating contextual stressors, research has shown the benefits of identifying sources of resiliency when caring for patients experiencing adversity (Gallo, Penedo, Espinosa de los Monteros, & Arguelles, 2009; Grote, Bledsoe, Larkin, Lemay Jr., & Brown, 2007; Waugh & Koster, 2015). Too often we take a deficit approach. By identifying resiliency and existing resources, providers can be more strength-focused and build on existing skills to empower women to take a larger role in their own health.

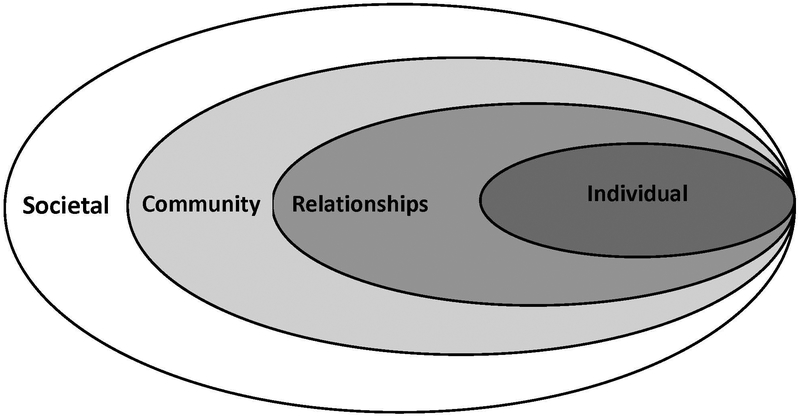

One way to conceptualize the full social context of disadvantaged women’s mental health is to consider their experiences within Urie Bronfenbrenner’s socioecological model, a conceptual model developed to bridge behavioral and anthropological theories of human development (Bronfenbrenner, 1992; Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998). Bronfenbrenner conceived of individuals as immersed in complex environmental contexts represented by concentric rings or levels (see Figure 1). A first micro-level represents the individual’s immediate social environment, including relationships with family, friends, and neighbors. A second meso-level represents the larger community in which the individual and their immediate social environment are embedded; one important part of the community is the health care system and the health providers within this system who can provide screening and intervention. Even more broadly, a third macro-level represents the larger societal environment consisting of shared attitudes and behavioral norms, including stigmatizing ideas about women’s roles, mental health and poverty. Importantly, although the individual is embedded within these intersecting contexts, the individual is an agent who acts upon these environments at the same time that environments shape individual outcomes (Brofenbrenner & Morris, 1998). Because the socioecological model has been used by scholars to understand both risk and protective factors related to depressive symptoms among adolescents (Olson & Goddard, 2010; Smokowski, Evans, Cotter, & Guo, 2014), we believed it could also be a helpful conceptual framework for considering how women’s lives and decisions about health care affect and are affected by depressive symptoms and socioeconomic disadvantage.

Figure 1.

Socioecological Model

Attending to women’s voices is a critical part of feminist research, practice, and advocacy, as well as patient-centered care. Our goal for the current study was to talk with women’s health patients experiencing both elevated depressive symptoms and socioeconomic disadvantage. We sought to understand their views of their mental health, the impact of social determinants of health, and their personal resources and skills in relation to the socioecological model. First-hand understanding of women’s experiences and perspectives in the context of the socioecological model may help health care providers have improved empathy and responsiveness to their patients’ experiences and needs, as well as better inform and tailor more meaningful and responsive approaches to depression care (Smith et al., 2009).

Method

Participants

This qualitative study was embedded in the context of a clinical trial using patient-centered approaches to improve mood and quality of life among obstetrics/gynecology patients with depression (NCT02087956). Women were recruited from three identified women’s health practices that primarily serve patients receiving Medicaid-subsidized health insurance, and randomized to either receiving a personalized resource list and check in calls or prioritization-based support provided by a community health worker. Women’s health patients completed waiting room screenings for depression (PHQ-9; Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001),9 anxiety (GAD-7; Spitzer, Kroenke, & Williams, 2006), alcohol abuse (AUDIT; Bush, Kiviahan, McDonnell, Fihn, & Bradley, 1998), substance abuse (DAST; Skinner, 1982), intimate partner violence (Feldhaus IPV Scale; Feldhaus et al., 1997), and immediate social needs (housing, transportation, etc. consistent with Crosier, Butterworth, & Rodgers, 2007). Those aged > 18 with PHQ-9 scores > 10 were invited to be evaluated for study eligibility and to enroll if they qualified. Exclusion criteria included active suicidal risk, psychosis, current alcohol or other substance abuse, living more than a 20-minute drive from the clinic, and inability to communicate in English. We invited the first twenty women who completed the active treatment phase of the clinical trial to participate in a qualitative interview about their mental health symptoms and experiences with the study interventions; all 20 agreed to complete the interview. The purpose of the interview was to help the research team assess women’s experiences of the trial intervention and to better understand their experiences of depression and their life priorities. Selected excerpts from these interviews are presented in this paper. The University Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures, and women who reported immediate safety concerns were evaluated further and connected with the indicated level of support (e.g., if a woman reported an active suicidal plan she was transferred to the emergency department; if a woman reported current interpersonal violence, she was offered a referral to the local shelter).

The 20 patients who completed the interviews had a mean age of 31.1 years (SD = 8.7); 5 were pregnant. The majority described themselves as African American/Black (n = 13, 65%); 4 (20%) were White; 1 (5%) Hispanic/Latina; 1 (5%) biracial, and 1 (5%) Native American. Twelve (60%) were single, divorced or widowed, and 8 (40%) were married or living with a partner. The women generally were poor, with half reporting a household income of less than US$10,000/year, although one outlier reported an income of US 40-$49,999/year. The women reported a broad range of unmet social needs in response to the following items by indicating that each was “not at all true” “slightly true” or “somewhat true:” “I have enough food in the house,” (n = 9, 45%); “I have transportation to get to and from my medical appointments,” (n = 8; 40%) “I have appropriate clothing,” (n = 5, 25%); “My housing is safe,” (n = 3; 15%); “My housing is stable,” (n = 5; 25%); “I have access to a working phone” (n = 1; 5%). In addition, three people (15%) reported “slightly true,” “somewhat true” or “very true” in response to the item, “I currently have legal needs.” The women presented with a mean PHQ-9 depression score of 12.7 (2.5) and mean GAD-7 anxiety score of 10.2 (5.7), suggesting clinically elevated levels of depression and anxiety in the moderate range. Three (15%) screened positive for experiencing intimate partner violence in the last year. Three (15%) also screened positive for use of illegal drugs, and the average AUDIT-C score was a 1.05 (1.7).

Procedure

Interview.

The investigators developed a semi-structured interview guide aiming to understand: 1) women’s views of themselves, their mental health symptoms, and their coping; and 2) perspectives about participating in the research study and the study interventions. For this study, the first content area was the primary focus. Two research assistants were trained to conduct the qualitative interviews. The interviews were on average 15 minutes in length, occurred over a span of 3 months, and were audiotaped and later transcribed.

Analytic Strategy.

Qualitative analyses were based on the Consensual Qualitative Research (CQR) approach using thematic content analysis with a group consensus process (Hill, Thompson, & Williams 1997; Hill et al. 2005). CQR consists of the following: (1) data collection with semi-structured interviews; (2) analysis of the interviews by a team of raters with diverse experiences and perspectives; (3) obtaining consensus on interpretation among the raters; (4) determining domains and core ideas; and (5) employing an auditor outside of the primary team to check the work.

We included 6 members on our primary analysis team: This diverse group offered physician, psychologist, lawyer, researcher, community advocate, and patient perspectives. A community advocate served as our auditor, reviewing and providing feedback on the results of the primary analysis team. Finally, we added an additional step to the traditional CQR approach by sharing the final results with our community advisory board, consisting of stakeholders representing women with depression and IPV experience and health care professionals, and asked them for verification of the findings.

The primary analysis team identified domains for coding and developed core ideas over the course of three meetings after review of 8 randomly selected transcripts. We identified assumptions/potential biases held by the team members prior to beginning data analysis: women would be able to report accurately about their experiences of the interventions; it is reasonable to accept the women’s reports as truthful; and bringing different perspectives and experiences to the analysis would be valuable. We also noted that although some team members previously experienced significant challenges and needs, at the time of the analysis, all had access to resources, such as safe housing, differentiating our daily experiences from those of many of the study participants.

The analysis team began initial discussions with a “start list” of domains derived from the interview questions. We determined core ideas or summaries of what was learned about each domain from each case; we did this in order to briefly capture the “essence” of what the participant said in regard to the domain. First, we read the transcripts independently. Then together, we expanded, modified, and refined these domains and agreed on core ideas via an iterative, consensus-driven process to better represent what we learned from the 8 transcripts. We agreed that we reached saturation when new domains and ideas were no longer emerging. The remaining 12 transcripts were distributed to the 6 members of the analysis team. We divided into groups of 2, and each group analyzed 4 additional transcripts, 2 from each treatment arm. The groups met until consensus was obtained between the two partners and then results were shared with the entire team. The team reviewed and edited each transcript’s results until we reached consensus.

Next, the auditor reviewed 4 transcripts and the findings to give feedback and determine if important information was missed. Her feedback was incorporated by the primary research team to finalize the domains and the illustrative quotes selected as representative of those domains. Last, we confirmed our findings at a community advisory board meeting.

Results

As the team worked through the transcripts toward obtaining consensus, several domains and core ideas emerged. We describe them briefly below, and then expand upon each one illustrated by quotations from individual women.

Challenges with life chaos, including competing and organizational daily life demands, health issues, and living with poverty.

A lack of stable, positive, social support partnered with the common experiences of grief and loss.

Significant emotional distress, regardless of whether the woman self-identified as having difficulties with depression specifically.

An empowered and resilient sense of self with confidence in capacity for self-growth.

An expansive repertoire of coping and self-care strategies.

Chaos.

It was common for women interviewed to identify lives filled with chaos. Typical challenges included difficulties accessing resources such as transportation, caregiving needs for their children or other family members, not having enough money, and coping with multiple health conditions. These chronic and daily challenges were reported to affect their lives in various ways, including but not limited to stress and managing their complex, competing needs.

My two older kids they have learning, severe learning disabilities, and severe health problems . . .it’s hard when two of them have severe learning disabilities and then it’s hard when you have two boys that have to go through surgery. . . I had to fight [for] the evaluation for my daughter. I wrote a letter, the doctor wrote a letter when she was in kindergarten for her to be evaluated for ADHD. . . . and so finally this year they finally evaluated her, they know she has ADHD. . . . she still also needed medication because she has [a] short attention span and she also has memory loss. (3013, 23 years, Latina)

I was going through a [pregnancy] termination. I was working full time and in school full time and I’m a single mother. So, that was a lot. That was wearing on me. (3000, 24 years, African American)

Women often identified that chaos directly contributed to barriers with health care engagement. Coping with the daily challenges often interfered with attending appointments and with following health and other recommendations. Managing the many factors involved with attending appointments (e.g. transportation, childcare) partnered with the complexities caused by having multiple competing appointments (e.g. court, children’s school, department of social services) often resulted in missed or cancelled health care appointments.

Public transportation doesn’t work for me. It’s too many of us and it actually becomes dangerous at some point when I have three little ones running around and I can’t tether them all to me. . . and then even when you get on the bus . . there’s usually no seats . . I’ve sat my kids in people’s lap. like. you don’t got to move, just hold this baby. So we can get where we got to go. (3004, 31 years, African American)

Me being pregnant - it’s so hard for me to get this stroller on the bus and get it folded up and put it in the right spot and get [my toddler] sit sat down. It’s just really complicated plus the bus ride out here, the bus is always packed. (3007, 22 years, White)

Lack of Social Support.

A lack of positive social support was identified as a domain, often with women reporting feeling isolated, angry, and sad. Women described feeling that they lacked a voice in their interactions with others, and were uncared for, dismissed, or misunderstood by others, Contributors to these feelings included experiencing significant loss, ongoing interpersonal conflict, or trauma.

Say if my husband like if he’s not understanding me or listening to me, I’m gonna tear this place up. . . so yeah, I just broke up all the TV’s in the household . (3014, 33 years, African American)

I’ve lost a total of six people in the last four months. One was my best friend, 35 years old and she stuck it out with me, the cries, the tears, the wiping the noses. (3001, 45 years, African American)

I was just conforming to what everybody wanted me to do. If they felt like I needed to be on pills I’d just take ‘em. They felt I needed to go to therapy I just do it because I just did not want to hear anybody negativity toward if I didn’t do it . . . (3015, 34 years, African American)

Emotional Distress.

All women met criteria for clinically elevated depressive symptoms on the PHQ-9. Yet we did not require them to identify themselves as depressed, nor did we evaluate whether their symptoms met criteria for a diagnosis of major depressive disorder (or any other diagnosis). Throughout the interviews, there was variability as to whether women identified themselves as having a problem with depression. Regardless, they described emotional distress as simply a part of their life experiences related to their life chaos, rather than a treatable diagnosis. Chronic distress seemed like an understandable and even normative response to experiencing constant, unrelenting negative social determinants of health, both in their own lives and in the lives of their friends and family

I’ve been dealing with it for a long time, I guess since a teenage years. It’s been like a rough journey but it’s like it’s no cure overnight. (3014, 33, African American)

I honestly don’t know. It’s just a lot in my life that is that was going on and it just dragged me down. (3003, 37, White)

Yeah depression an issue for a long time…It’s like up and down, a roller coaster, good days, bad days. (3011, 38, African American)

Women reported struggles with many symptoms in addition to depression, including anxiety, impulsivity, irritability and anger.

I get anxious. I’m always anxious number one but I get anxious and it’s just like I don’t have the solution right then and there and so it’s just like if I’m not being heard that anxiety turns to like anger and rage. (3014, 33 years, African American)

I just let it [stress] sit there; I don’t even want to, I just let it sit in my mind. So all the stress just sit there and I just let it build and build ‘til I have a mental attack. (3002, 39 years, African American)

Empowered sense of self.

Many women viewed themselves as resilient, empowered women with the capability to create the positive changes they need in their lives despite the stress and strains of their lives. They described an intrinsic sense of autonomy and agency to create meaningful growth in their lives. They identified goals, and expressed confidence and capacity to invest in themselves to make progress toward their goals.

No matter my circumstances, no matter my progress, I’m still determined to make it in life no matter if I have to do it by myself or if there’s support out there. I’m gonna do it. (3002, 39 years, African American)

I need to start taking more control over my life and stop letting other people kind of tell ‘em what to do and start saying, “I need this for myself”. . . . when I’m doing what other people want me to do it’s just making me just worse inside . . . I have to start thinking about myself and my happiness especially for my kids. (3015, 34 years, African American)

I wasn’t about to stay with it too long . . . I’m allergic to being abused. . . . I went through enough of that as a kid I’m not gonna go through that as an adult. I got a choice now and I choose not to go through it so I’m okay. (3004, 31 years, African American)

Coping.

Women shared many active approaches to coping with their difficulties. They identified skills, strategies, and resources that they use to address their chaos and distress. Some were active coping strategies, whereas other strategies involved engaging support, cognitive restructuring, or traditional mental health care.

Make sure you stay positive. You put, you don’t always look at the negative side just always try to stay positive. Whether it hurts you or makes you cry, makes you feel depressed you can still overcome that obstacle because you’re very strong and it takes a strong person to overcome obstacles. Especially if they were terrible or horror or whatever it is but you always gotta stand strong especially when you have a family of your own you’re raising. (3013, 23 years, Latina)

Just letting the days go by and that it’s going to be okay the next day not dwelling on things. (3005, 23 years, African American)

I journal and I have people to talk to. (3003, 37 years, White)

I’m on antidepressant pills, so those kind of help and I have my cat’s help. I have a lot of friends and I have my dad and my stepmom, so I’m not as depressed as I once was. So, I’m doing better with it. (3003, 37 years, White)

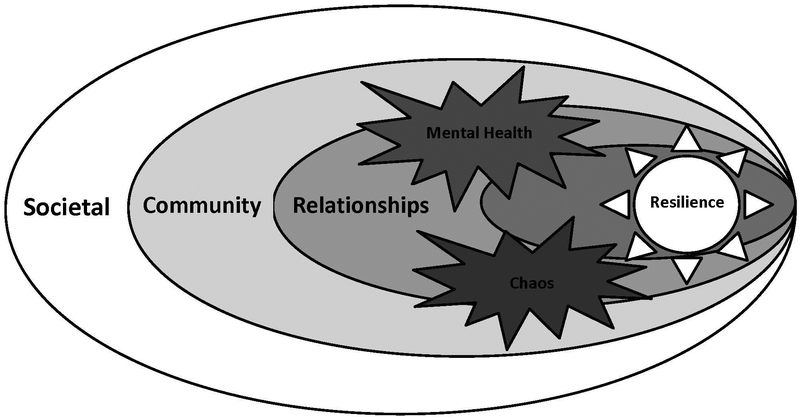

Our next step was to contextualize our findings into a broader framework for understanding the interplay of these multidimensional levels specifically for women living with depressive symptoms and socioeconomic disadvantage. Thus, we applied and refined Bronfenbrenner’s socioecological model to reflect that mental health symptoms and chaos related to socioeconomic disadvantage profoundly affected intrapersonal, interpersonal, and structural aspects of their lives. To graphically depict these cross-cutting effects, we inserted images of bursts where mental health and chaos overlap and touch individual, relationship and community levels of experience (see Figure 2). A burst, which is an uncontrolled eruption of internal pressure, symbolizes women’s negative mood states, the conflicts and losses that women experienced within their close relationships as well as barriers in navigating community systems offering resources such as health care and transportation. Furthermore, we refined the image to also reflect women’s resilience. To graphically depict women’s sense of feeling empowered, optimistic and hopeful, we inserted an image of a sun that touches the individual and relationship context. The comments provided here suggest that both inner resources and supportive interpersonal relationships were important sources of resilience for women. When the results and a draft of the adapted figure were shared with our community advisory board for respondent verification, they strongly resonated with members. In fact, one typically reserved woman who serves as a patient partner spontaneously shouted out, “That is my life!” and proceeded to explain how this figure represented her experience.

Figure 2.

Refined Socioecological Model

Discussion

The team’s review of the data confirmed that life context matters among this group of women seeking women’s health care. The women we interviewed identified diverse and critical social factors that contribute to their mood, ability to function, health, and health care engagement. Consistent with other studies focused on women’s health and barriers to engagement among primarily low income populations (Grote et al., 2007; Myors et al., 2015; Pugach & Goodman, 2015), participants described that stress was important to consider at multiple levels, from the individual level (e.g., depression symptoms) to the community level (e.g., cumbersome transportation system). The women did not discuss societal issues such as policy or culture, thus not addressing the societal level of the model. Nonetheless, our data provide further support for the utility of the socioecological model in conceptualizing depression and related mental health symptoms even beyond what has already been demonstrated in adolescence (Olson & Goddard, 2010; Smokowski et al., 2014). As in this past work, both risk and protective factors were identified. That is, chaos and mental health difficulties were pervasive themes mapping across women’s lives, and yet, women described skills, resiliency, and hope as helping them to keep pushing forward in the context of chaos and mental health difficulties.

Applying the socioecological model to the population of women described in this study highlights the pervasiveness of mental health concerns and the universal experience of chaos among women living with socioeconomic disadvantage. Living daily with mental health symptoms affects women’s capacity to thrive across all levels of their lives, as individuals and for those with children, as mothers (Goyal et al., 2010; Heflin & Iceland, 2009; Logsdon et al., 2009). Impaired mental health compromises women’s abilities to cope effectively, consequently impacting their capacity to engage in using support, resources, and health care to improve their situations and health. Chaos related to socioeconomic disadvantage means constant daily struggles with a chronic scarcity of resources with impossible trade-offs. For example, if a woman attends her health care appointment to obtain health screenings and contraception, she misses time at her job, consequently losing income and risking job security. A woman’s rent and utility bills may be past due, but unless she spends her limited resources on fixing her car, she cannot travel to a grocery store with fresh produce to feed herself and her family. This recapitulating cycle results in women’s “whack-a-mole” experience of trying to address the most critical current issue, not knowing what else will pop up next but knowing something will, resulting in a chronic and pervasive sense of chaos.

Importantly, in addition to reporting struggles with chaos and mental health, the women interviewed also expressed hope and confidence they could improve the challenges in their lives. They recognized their unique strengths and abilities, and believed in themselves to make positive change. They also explicitly acknowledged the beneficial role of supportive interpersonal relationships in their lives. Such findings imply that supportive relationships with health care providers might also promote greater resilience. Respecting and leveraging women’s competence, confidence, and resiliencies in working towards realistic, personalized goals may promote a more positive patient and provider relationship. In this type of relationship, the woman feels understood by her provider and experiences a greater sense of agency and self-efficacy, leading to better engagement with patient-centered recommendations. In fact, Pugach and Goodman (2015) reached similar conclusions from their qualitative research; participants were more engaged with therapy when therapists were aware of the client’s experiences of socioeconomic disadvantage and associated stressors, showed flexibility, and emphasized building on strengths.

Health care providers cannot heal many of the challenges related to socioeconomic disadvantage despite their profound impact on health. This reality can be discouraging (Thompson, Nitzarim, Cole, Frost, Ramirez Stege, & Vue, 2015). Yet we can incorporate recognition of these struggles and capitalize on the resiliencies in the delivery of our care. A first step is to elicit and validate women’s experiences and perspectives, as best as we are able to from the vantage point of one’s own life experiences. Seeking to understand and respect each woman’s life context, values, and priorities creates space for genuine empathy and human connection (Jordan, 2008; Jordan, 2010). Fostering supportive relationships based on authentic understanding of their challenges and hopes may enhance the quality of the relationship while also helping providers obtain accurate information to help them plan effective care. It is important to be aware of contextual factors that may impact patients’ health care conversations, and to explore the relative fit and suitability of a recommended intervention for an individual woman. Only then can the provider and patient develop a realistic plan that better capitalizes on her skills, responds to her unique challenges, and meets her prioritized needs. For example, for some women without positive social support and with a strong faith, joining the church choir may lead to greater benefit than starting an anti-depressant; or for some women without reliable transportation, long-acting reversible contraception may be more practical than taking daily oral contraceptives when she is challenged to get to a pharmacy.

Increasingly, health care education is calling for providers to think about how gender, socioeconomic disadvantage, and other social determinants of health affect interactions with patients (Metzl & Hansen, 2014). Non-judgmental and systematic screening of social determinants of health via electronic health records can increase providers’ awareness of their patients’ contexts and allow them to factor these needs in their treatment recommendations (Adler & Stead, 2015; Fiscella, Tancredi, & Franks, 2009). There is increasing support for incorporating interventions addressing social determinants of health within health care settings, such as medical legal partnerships, which address legal needs within health care settings (Regenstein, Trott, Williamson, & Theiss, 2018); additionally, one study found that use of the Health Leads program, which connects low-income patients with the basic resources they need to be healthy, in three primary care practices was associated with improvement for hypertension (blood pressure and LDL-C levels) (Berkowitz, Hulberg, Standish, Reznor, & Atlas, 2017). Partnering women with community health workers is another promising approach to addressing contextual concerns related to health and health care engagement in a de-stigmatizing way (Carroll, Humiston, Meldrum et al., 2010; Dohan & Schrag, 2005; Ell, Katon, Xie et al., 2010; Fischer, Sauaia, & Kutner, 2007; Griswold, Homish, Pastore, & Leonard, 2010).

Community health workers, who are trained lay people from communities similar to the target population, work with patients to improve health care engagement. Community health workers are in a unique position to understand the full context of women’s lives, and are community-based, meaning they can meet women outside of the confines of a medical office, increasing access and comfort. Conducting a structured prioritization process with a decision aid to determine what problems are most important to each woman is another recommendation to consider for women’s health patients with social determinants of health and depression. This process might empower women’s sense of competence and autonomy in the context of a supportive relationship. This process may provide women with the capacity to develop and implement a plan that is meaningful to them to improve their health.

It is notable that the women in our study did not explicitly identify societal level issues as contributing to their depression or life experiences. The patient-level approaches such as those outlined here may help providers and patients address some unmet needs and increase patients’ ability to access depression treatments like psychotherapy and anti-depressants. Yet, patient level interventions will almost certainly fall short on their own given the problematic societal contexts that situate individual women’s experiences. This may be especially true for women with socioeconomic disadvantage who experience additional forms of oppression related to their age, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, religion, immigrant status, or other identities (Anderson, 2014; Logsdon et al., 2009; Manne, 2018; Smith et al., 2009) as well as intimate partner violence (Goodman et al., 2009). Furthermore, sociopolitical factors, such as wage inequities, lack of paid maternity leave, and societal tolerance of sexual harassment and abuse must be addressed to improve the circumstances of women living with depression and socioeconomic disadvantage. Although these types of advocacy work lie beyond the scope of most health care practice, health care providers must, at a minimum, recognize the need for intervention and advocacy across all levels of the socioecological model.

As with all studies, there are limitations that must be considered. The interview was highly structured and may have elicited specific responses, particularly those in micro and meso but not macro levels of the socioecological model, while not encouraging reflections about how experiences are affected by broader structural or social level contexts. The research team brought preconceived ideas and biases to the data analysis. Although the majority of the study participants were African-American, we did not have any African-American members on our team. The identified themes may have been a result of women’s study participation. Generalizability of the findings to others not interviewed is unknown; it is important to recall that while all participants had elevated depressive symptoms, they were not evaluated for a diagnosis of depression. However, that was not the goal of this exploratory analysis, which aimed to understand women’s needs with self-reported distress rather than consequences of a depression diagnosis.

We believe our findings and application of the socioecological model to understand them will help shift the way in which we approach our conceptualization of women’s needs and help us be more responsive (see also Smith et al., 2009). Future research will allow us to determine if these findings are unique to women’s health patients, or generalizable to other individuals living with socioeconomic disadvantage and depression. The themes identified here represent voices of this group of women and allowed us to identify possible contributing factors to the dynamic process of seeking help and accessing resources. This study serves to highlight the importance of understanding women’s full experiences and of providing women-centered intervention options that are supportive, shaped by self-identified priorities, and capitalize on women’s existing resiliencies and skills.

Acknowledgements:

This research was supported by Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute award number AD-12–4261.

This research was also supported by the University of Rochester CTSA award number UL1 TR000042 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute nor the National Institutes of Health. Study data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Rochester Medical Center. REDCap is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies, providing 1) an intuitive interface for validated data entry; 2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; 3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and 4) procedures for importing data from external sources. The study is registered in clinicaltrials.gov (NCT20879956). The Institutional Review Board at the University of Rochester approved the study protocol on 8/1/2013.

We would like to thank the following individuals for their hard work, dedication, and essential contributions to this paper: Jenna Chaudari, BS; Sarah Danzo, B.A.; Shaya Greathouse, BA; Nikki Haynesworth, M.S., MHC; Shirley Pope; and Cassandra Uthman, B.A.

References

- ACOG Committee Opinion 729. (2018). Importance of social determinants of health and cultural awareness in the delivery of reproductive health care. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 131 (1), e43–e48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler NE, & Stead WW (2015). Patients in context—EHR capture of social and behavioral determinants of health. New England Journal of Medicine, 372(8), 698–701. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1413945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KJ (2014). Modern misogyny: Anti-feminism in a post-feminist era. Oxford: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Belle D, & Doucet J (2003). Poverty, inequality, and discrimination as sources of depression among US women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 27(2), 101–113. doi: 10.1111/1471-6402.00090 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz SA, Hulberg AC, Standish S, Reznor G, & Atlas SJ (2017). Addressing unmet basic resource needs as part of chronic cardiometabolic disease management. JAMA Internal Medicine, 177(2), 244–252. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat A, Reed SD, & Unützer J (2017). The obstetrician–gynecologist’s role in detecting, preventing, and treating depression. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 129(1), 157–163. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U (1992). Ecological systems theory Six theories of child development: Revised formulations and current issues (pp.187–249). London, England: Jessica Kingsley Publishers [Google Scholar]

- Brofenbrenner U, & Morris PA (1998).The ecology of developmental processes In Lerner RM (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology (pp. 993–1128). New York: Wiley [Google Scholar]

- Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, & Bradley KA (1998). The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): An effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Archives of Internal Medicine, 158, 1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JK, Humiston SG, Meldrum SC, Salamone CM, Jean-Pierre P, Epstein RM, & Fiscella K (2010). Patients’ experiences with navigation for cancer care. Patient Education and Counseling, 80, 241–247. 10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P (2004). How stigma interferes with mental health care. American Psychologist, 59(7), 614–625. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosier T, Butterworth P, & Rodgers B (2007). Mental health problems among single and partnered mothers: The role of financial hardship and social support. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 42, 6–13. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0125-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNavas-Walt C, Bernadette D, Proctor BD, & Smith JC (2012). U.S. census bureau, current population reports, P60–243, Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2011, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Dohan D, & Schrag D (2005). Using navigators to improve care of underserved patients: current practices and approaches. Cancer, 104, 848–855. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ell K, Katon W, Xie B, Lee P-J, Kapetanovic S, Guterman J, & Chou C-P (2010). Collaborative care management of major depression among low-income, predominantly Hispanic subjects with diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care, 33, 706–713. 10.2337/dc09-1711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldhaus KM, Koziol-McLain J, Amsbury HL, Norton IM, Lowenstein SR, & Abbott JT (1997). Accuracy of 3 brief screening questions for detecting partner violence in the emergency department. JAMA, 277, 1357–1361. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03540410035027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiscella K, Tancredi D, & Franks P (2009). Adding socioeconomic status to Framingham scoring to reduce disparities in coronary risk assessment. American Heart Journal, 157(6), 988–994. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer SM, Sauaia A, & Kutner JS (2007). Patient navigation: a culturally competent strategy to address disparities in palliative care. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 10, 1023–1028. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo LC, Penedo FJ, Espinosa de los Monteros K, & Arguelles W (2009). Resiliency in the face of disadvantage: Do Hispanic cultural characteristics protect health outcomes? Journal of Personality, 77(6), 1707–1746. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00598.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman JH (2009). Women’s attitudes, preferences, and perceived barriers to treatment for perinatal depression. Birth, 36(1), 60–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2008.00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman LA, Pugach M, Skolnik A, & Smith L (2013). Poverty and mental health practice: Within and beyond the 50‐minute hour. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(2), 182–190. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman LA, Smyth KF, Borges AM, & Singer R (2009). When crises collide: How intimate partner violence and poverty intersect to shape women’s mental health and coping. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 10(4), 306–329. doi: 10.1177/1524838009339754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal D, Gay C, & Lee KA (2010). How much does low socioeconomic status increase the risk of prenatal and postpartum depressive symptoms in first-time mothers? Women’s Health Issues, 20(2), 96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griswold KS, Homish GG, Pastore PA, & Leonard KE (2010). A randomized trial: Are care navigators effective in connecting patients to primary care after psychiatric crisis? Community Mental Health Journal, 46, 398–402. doi: 10.1007/s10597-010-9300-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grote NK, Bledsoe SE, Larkin J, Lemay EP Jr, & Brown C (2007). Stress exposure and depression in disadvantaged women: The protective effects of optimism and perceived control. Social Work Research, 31(1), 19–33. doi: 10.1093/swr/31.1.19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grote NK, Zuckoff A, Swartz H, Bledsoe SE, & Geibel S (2007). Engaging women who are depressed and economically disadvantaged in mental health treatment. Social Work, 52, 295–308. doi 10.1093/sw/52.4.295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heflin CM, & Iceland J (2009). Poverty, material hardship, and depression. Social Science Quarterly, 90, 1051–1071. doi 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2009.00645.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill CE, Thompson BJ, & Williams EN (1997). A guide to conducting consensual qualitative research. The Counseling Psychologist, 25, 517–572. doi: 10.1177/0011000097254001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill CE, Knox S Thompson BJ, Williams EN, Hess SA, & Ladany N (2005). Consensual qualitative research: An update. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52, 196–205. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.196 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan JV (2008). Recent developments in relational-cultural theory. Women in Therapy, 31, 1–4, doi: 10.1080/02703140802145540 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan JV (2010). Relational-cultural therapy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, & Williams JBW (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16, 606–613. doi 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, . . . Kendler KS (1994). Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United State: Results from the national comorbidity study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 51, 8–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy LB, & O’Hara MW (2010). Psychotherapeutic interventions for depressed, low-income women: A review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 934–950. doi 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logsdon MC, Hines-Martin V, & Rakestraw V (2009). Barriers to depression treatment in low-income, unmarried, adolescent mothers in a southern, urban area of the United States. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 30(7), 451–455. doi: 10.1080/01612840902722187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne K (2018). Down girl: The logic of misogyny. NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, Houweling TA, Taylor S, & Commission on Social Determinants of Health. (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. The Lancet, 372(9650), 1661–1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melville JL, Reed SD, Russo J, Croicu CA, Ludman E, LaRocco-Cockburn A, & Katon W (2014). Improving care for depression in obstetrics and gynecology: A randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 123(6), 1237–1246. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messias E, Eaton WW, & Grooms AN (2011). Economic grand rounds: Income inequality and depression prevalence across the United States: An ecological study. Psychiatric Services, 62(7), 710–712. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.7.pss6207_0710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzl JM, & Hansen H (2014). Structural competency: Theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality. Social Science & Medicine, 103, 126–133. doi:10.1016%2Fj.socscimed.2013.06.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, & Bruce ML (2002). Gender issues and socially disadvantaged women. Mental Health Services Research, 4, 249–253. doi 10.1023/A:1020976918433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muntaner C, Eaton WW, Miech R, & O’Campo P (2004). Socioeconomic position and major mental disorders. Epidemiologic Review, 26, 53–62. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxh001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myors KA, Johnson M, Cleary M, & Schmied V (2015). Engaging women at risk for poor perinatal mental health outcomes: A mixed-methods study. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 24, 241–252. doi: 10.1111/inm.12109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson J, & Goddard HW (2010). An ecological risk/protective factor approach to understanding depressive symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Extension, 48, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Poleshuck EL, & Woods J (2014). Psychologists partnering with obstetricians and gynecologists: Meeting the need for patient-centered models of women’s health care delivery. American Psychologist, 69(4), 344–354. doi: 10.1037/a0036044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugach MR, & Goodman LA (2015). Low-income women’s experiences in outpatient psychotherapy: A qualitative descriptive analysis. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 28, 403–426. doi 10.1080/09515070.2015.1053434 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Regenstein M, Trott J, Williamson A, & Theiss J (2018). Addressing Social Determinants of Health Through Medical-Legal Partnerships. Health Affairs, 37(3), 378–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva M, Loureiro A, & Cardoso G (2016). Social determinants of mental health: A review of the evidence. The European Journal of Psychiatry, 30(4), 259–292. [Google Scholar]

- Smith L, Chambers DA, & Bratini L (2009). When oppression is the pathogen: The participatory development of socially just mental health practice. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 79(2), 159–168. doi: 10.1037/a0015353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smokowski PR, Evans CBR, Cotter KL, & Guo S (2014). Ecological correlates of depression and self-esteem in rural youth. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 45, 500–518. doi: 10.1007/s10578-013-0420-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA (1982). The drug abuse screening test. Addictive Behavior, 7, 363–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, & Lowe B (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166, 1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson MN, Nitzarim RS, Cole OD, Frost ND, Ramirez Stege A, & Vue PT (2015). Clinical experiences with clients who are low-income: Mental health practitioners’ perspectives. Qualitative Health Research, 25, 1675–1688. doi: 10.1177/1049732314566327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vera-Gray F (2017). Men’s intrusion, women’s embodiment: A critical analysis of street harassment. Abingdon, Oxon, Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Waugh CE, & Koster EH (2015). A resilience framework for promoting stable remission from depression. Clinical Psychology Review, 41, 49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]