Abstract

Rationale: Postsepsis care recommendations target specific deficits experienced by sepsis survivors in elements such as optimization of medications, screening for functional impairments, monitoring for common and preventable causes of health deterioration, and consideration of palliative care. However, few data are available regarding the application of these elements in clinical practice.

Objectives: To quantify the delivery of postsepsis care for patients discharged after hospital admission for sepsis and evaluate the association between receipt of postsepsis care elements and reduced mortality and hospital readmission within 90 days.

Methods: We conducted a retrospective chart review of a random sample of patients who were discharged alive after an admission for sepsis (identified from International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision discharge codes) at 10 hospitals during 2017. We used a structured chart abstraction to determine whether four elements of postsepsis care were provided within 90 days of hospital discharge, per expert recommendations. We used multivariable logistic regression to evaluate the association between receipt of care elements and 90-day hospital readmission and mortality, adjusted for age, comorbidity, length of stay, and discharge disposition.

Results: Among 189 sepsis survivors, 117 (62%) had medications optimized, 123 (65%) had screening for functional or mental health impairments, 86 (46%) were monitored for common and preventable causes of health deterioration, and 110 (58%) had care alignment processes documented (i.e., assessed for palliative care or goals of care). Only 20 (11%) received all four care elements within 90 days. Within 90 days of discharge, 66 (35%) patients were readmitted and 33 (17%) died (total patients readmitted or died, n = 82). Receipt of two (odds ratio [OR], 0.26; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.10–0.69) or more (three OR, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.11–0.72; four OR, 0.12; 95% CI, 0.03–0.50) care elements was associated with lower odds of 90-day readmission or 90-day mortality compared with zero or one element documented. Optimization of medications (no medication errors vs. one or more errors; OR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.21–0.92), documented functional or mental health assessments (physical function plus swallowing/mental health assessments vs. no assessments; OR, 0.14; 95% CI, 0.05–0.40), and documented goals of care or palliative care screening (OR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.25–1.05; not statistically significant) were associated with lower odds of 90-day readmission or 90-day mortality.

Conclusions: In this retrospective cohort study of data from a single health system, we found variable delivery of recommended postsepsis care elements that were associated with reduced morbidity and mortality after hospitalization for sepsis. Implementation strategies to efficiently overcome barriers to adopting recommended postsepsis care may help improve outcomes for sepsis survivors.

Keywords: sepsis, survivorship, transitional care, mortality, hospital readmission

Sepsis is a common and life-threatening condition (1). Aggressive, early treatment of sepsis and initiatives such as the Surviving Sepsis Campaign have decreased hospital mortality rates for patients with sepsis over the last two decades (2–4). However, the increasing number of sepsis survivors has created a growing need to address the downstream challenges after sepsis (5, 6). After experiencing an episode of sepsis, as many as 75% of patients develop new functional disabilities and 34% develop severe cognitive impairment (7–14).

Despite a greater awareness of postacute sequelae, management of sepsis survivors remains complex (15). Patients frequently face complications from incomplete resolution of the primary infection, recurrence of the primary infection or new infection, worsening control of existing chronic conditions, and persistent organ dysfunction (16). Sepsis survivors often believe their needs are not being met comprehensively, with 41–63% reporting dissatisfaction with the support received during and after hospitalization (e.g., in-hospital explanation of sepsis, in-hospital physical therapy and psychological counseling, postsepsis education, and post-hospital social services support and psychological counseling) (17). Importantly, the inadequacy of current postsepsis care is reflected by high rates of postdischarge mortality and healthcare use, including a 90-day hospital readmission rate of 40% and over 3 billion dollars in preventable costs (18–25).

In the absence of clinical trial evidence to guide post-hospitalization management in sepsis survivors, best-practice care is based on expert recommendations (16). These recommendations emerged from a comprehensive review of sepsis survivorship and can be conceptualized as a postsepsis bundle of care consisting of 1) optimization of medications; 2) early identification and management of new functional, cognitive, or mental health impairments; 3) close monitoring for exacerbation of comorbid conditions after discharge; and 4) palliative care when appropriate (16, 26–31). However, no studies have examined how frequently these recommendations are applied in practice, or whether these care elements are associated with improved health outcomes for sepsis survivors. Therefore, our objectives in this study were to quantify the delivery of postsepsis care for patients discharged after hospital admission for sepsis, and to evaluate the association between receipt of postsepsis care elements and reduced mortality and hospital readmission within 90 days.

Methods

Research Design and Study Cohort

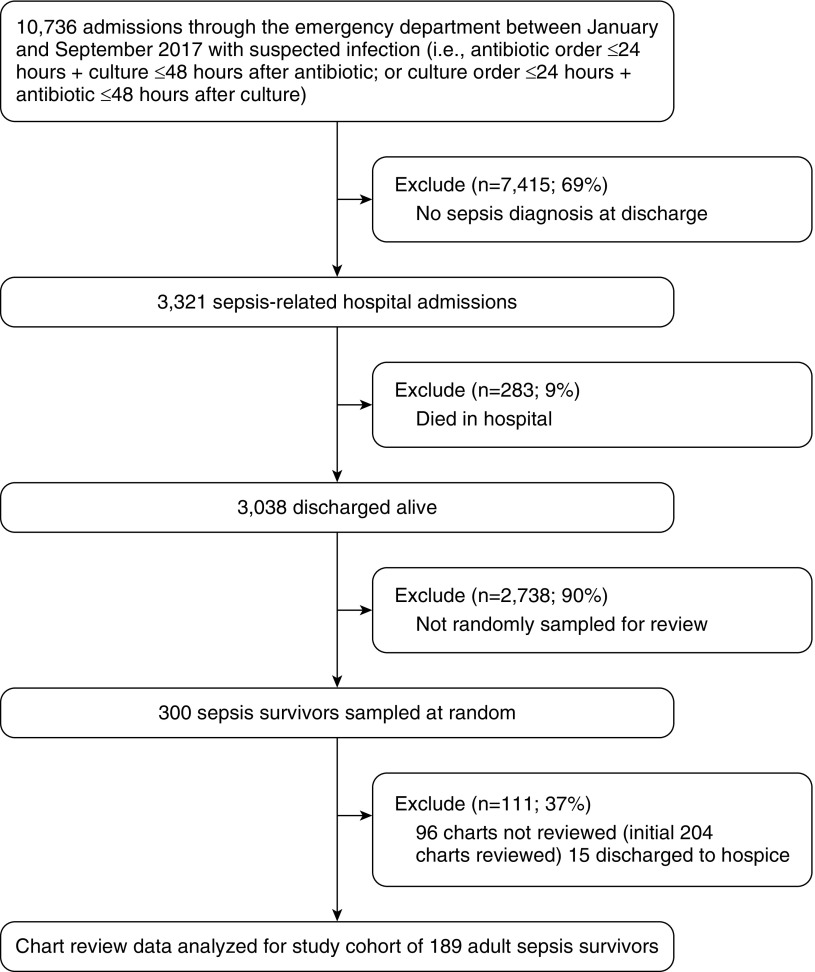

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of adults (>18 years old) who were hospitalized between January and September 2017 at 10 acute hospitals within a single large, integrated health system in the southeastern United States, including two large (>450 beds) tertiary-care teaching hospitals and eight nontertiary-care hospitals in geographically diverse settings (urban, suburban, and rural). We included patients who had both clinically suspected infection at presentation (i.e., first antibiotics and microbiology culture orders initiated within 24 hours of emergency department presentation) and ultimately a diagnosis of sepsis at discharge (International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision [ICD-10] codes A40-41 and R65.2). We excluded patients who died during the index hospitalization. From our initial cohort, we randomly sampled 300 patients (10%) for review, and chart reviewers abstracted data from the electronic health record (EHR) for the first 204 of these patients. We excluded individuals who were discharged to hospice from the final analyses (n = 15) because of potential associations with receipt of postsepsis care and mortality (n = 12 [80%] died within 90 days of hospital discharge). Chart reviews were completed between July 2018 and January 2019. Data elements were collected as part of routine clinical care. A flow diagram of the patient selection process is provided in Figure 1. The Atrium Health Institutional Review Board approved this study with a waiver of informed consent.

Figure 1.

Cohort selection and random sampling.

Measures

Patient characteristics

We extracted patient and clinical data from the Atrium Health electronic data warehouse (EDW), which integrates data on all clinical care delivered across the 10 study hospitals. We obtained demographic information from patient registration data. We used ICD-10 diagnosis codes from healthcare encounters during the previous 12 months to identify comorbidities and calculate weighted Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) scores (32). We collected index hospitalization laboratory and vital sign values from the EDW (mean arterial pressure, creatinine, bilirubin, platelets, lactate, and Glasgow Coma Scale) and applied standard definitions to assess organ dysfunction (33). We used initiation of mechanical ventilation to classify respiratory failure, as described in previous studies (34). Hospital length of stay was calculated as the number of days between hospital admission and discharge dates. Discharge disposition was collected from hospital administrative data and categorized (home, home with health services, skilled nursing facility, long-term care or rehabilitation, and other).

Postsepsis care elements

We created definitions for each of the postsepsis care elements, which allowed for structured data abstraction (Table 1). Using a standardized form (see Table E1 in the online supplement), three internal medicine physicians (S.P.T., M.F.S., and T.P.S.) determined whether and where (inpatient or outpatient setting) the care elements occurred. For each patient, EHR documents were reviewed, including discharge summaries, progress notes, care management notes, therapy documents, follow-up visit notes, medication administration records, and care alignment tools. Data abstraction spanned the period from initial presentation at the index hospitalization through the earliest date of mortality or hospital readmission, or 90 days after hospital discharge. If there was uncertainty about whether the documentation represented delivery of recommended care, the question was resolved by discussion and a majority vote. In 10 patients there were 22 data elements that required discussion, and all ultimate determinations were unanimous.

Table 1.

Postsepsis care elements

| Core Element | Recommendations (16) |

|---|---|

| Optimize medications | |

| Medication management errors |

|

| Screen for common impairments after sepsis | |

| Functional disability |

|

| Swallowing impairment |

|

| Mental health impairment |

|

| Anticipate and monitor for common and preventable causes of deterioration | |

| Infection |

|

| Heart failure exacerbation | Ambulatory follow-up within 2 wk for disease-specific monitoring. |

| Acute renal failure | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation | |

| Align treatment with patient preferences | Palliative care consultation with appropriate patients.* |

| Goals of care. Educate about disease progression and terminal illness. |

Patients with end-stage illness or multiple hospitalizations.

After data collection was completed, we created categorical variables for receipt of each of four care elements. First, “optimization of medications” was coded as 0 if medication management errors were identified, and as 1 if appropriate use of antibiotics (selection, dose, and duration [based on Infectious Disease Society of America practice guidelines] [35]) and management of medications (discontinue hospital medications no longer indicated [e.g., proton-pump inhibitors, antipsychotics, and antiemetics] [26, 27, 36], restart any necessary long-term medications [e.g., statins, β-adrenergic blocking agents, and corticosteroids], and adjust doses appropriately [if needed based on a change in creatinine clearance or body weight]) occurred. Second, “screening for common impairments after sepsis” was coded as 0 if no assessments were completed/documented, as 1 if only a physical assessment was completed (e.g., a physician-documented subjective assessment such as “no difficulty with ambulation” or physical therapist evaluation), and as 2 if a physical assessment plus a swallowing (physician-documented symptoms or speech therapist evaluation) or mental health (physician-documented symptoms or validated scale [e.g., Patient Health Questionnaire 2]) assessment was completed. Categorization for this element was informed by the observed distribution of data elements (i.e., there were no documented swallowing or mental health assessments without a completed physical assessment). Third, “anticipate and monitor for common and preventable causes of health deterioration” was coded as 0 if either discharge education or timely ambulatory follow-up was not completed, and as 1 if documented discharge education about symptoms of sepsis and signs of recurrence and ambulatory follow-up were both completed within 2 weeks of hospital discharge. Fourth, “treatment aligned with patient preferences” was coded as 0 if the goals of care were not documented or palliative care consultation was not provided to the appropriate patients (i.e., patients with an end-stage illness such as cirrhosis, heart failure, or malignancy, or with more than two hospitalizations within the prior 90 days [37]), and as 1 if the goals of care were documented or palliative care consultation was provided to the appropriate patients.

We counted the number of care elements (0–4) documented for each patient (i.e., optimization of medications = appropriate medication management; screening for common impairments after sepsis = physical assessment plus a swallowing or mental health assessment; anticipate and monitor for common and preventable causes of health deterioration = documented discharge education and ambulatory follow-up, both completed within 2 weeks of hospital discharge; and treatment aligned with patient preferences = goals of care documented or palliative care consultation provided to appropriate patients). Few observations with zero elements were documented. Thus, we analyzed receipt of zero or one care element as a combined group.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was the composite, dichotomous endpoint of all-cause mortality or unplanned hospital readmission, both assessed 90 days after the index hospital discharge. Mortality was ascertained via Social Security Administration Limited Access Death Master File data linked to existing patient records in the EDW. Hospital readmissions were captured from healthcare use data in the EDW. The definition of “readmission” included both inpatient status and observation status, as both represent an adverse event that is important for patients and healthcare systems (38). Because mortality may not be a modifiable outcome in this population, we also evaluated 90-day hospital readmission as a separate secondary outcome (39).

Statistical Analyses

We calculated descriptive statistics (i.e., medians and interquartile range for continuous variables, and counts and percentages for categorical variables) to describe the characteristics of the study sample, the proportion of patients who received postsepsis care in compliance with each recommended element, and the combination of all recommended elements. We constructed multivariable logistic regression models to evaluate associations between completion of recommended care elements and 90-day mortality and hospital readmission outcomes, adjusted for age, CCI, hospital length of stay, and discharge disposition. First, we examined the association between the number of care elements received and composite 90-day mortality and hospital readmission. We then examined the association between individual care elements (optimization of medications, screening for common impairments after sepsis, anticipating and monitoring for common and preventable causes of health deterioration, and treatment aligned with patient preferences) and a composite of 90-day mortality and hospital readmission. Separately, we repeated the logistic regression analyses to assess associations between the number and types of care elements received and 90-day hospital readmission. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide v7.1. Statistical tests were two-tailed and P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics are provided in Table 2. The median age was 62 years. A majority of patients had Medicare insurance (64%) and a high comorbidity burden (median CCI = 6). Nearly all of the patients (93%) presented with at least one sign of organ dysfunction, and 41% were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) on presentation. Patients experienced a median hospital length of stay of 6 days, and 7% were treated in the ICU for at least 72 hours during their hospitalization. More than half of the patients (57%) were discharged home without postacute services, 16% were discharged with home health, and 21% were discharged to skilled nursing facilities. Within 90 days of discharge, 66 (32%) of the patients were readmitted and 33 (17%) died.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of sepsis survivors

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age, yr, median (IQR) | 62 (50–74) |

| Female | 96 (51) |

| Race | |

| White | 131 (69) |

| Black | 43 (23) |

| Other | 15 (8) |

| Insurance status | |

| Medicare | 121 (64) |

| Commercial | 35 (19) |

| Medicaid/self-pay | 31 (16) |

| Other | 2 (1) |

| Discharge disposition | |

| Home | 108 (57) |

| Home with health services | 31 (16) |

| Skilled nursing facility | 39 (21) |

| Long-term care/rehabilitation | 8 (4) |

| Other | 3 (2) |

| Charlson comorbidity index, median (IQR) | 6 (3–9) |

| Chronic lung disease | 67 (35) |

| Chronic renal disease | 41 (22) |

| Heart failure | 28 (15) |

| Organ dysfunction at presentation* | |

| Evidence of any organ dysfunction type | 176 (93) |

| Mean arterial pressure <70 mm Hg | 130 (69) |

| Creatinine >1.2 mg/dl | 105 (56) |

| Bilirubin >1.2 mg/dl | 49 (26) |

| Platelets <150 cells/μl | 54 (29) |

| Lactate ≥2.0 mmol/L | 85 (45) |

| Glasgow Coma Scale <15 | 72 (38) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 17 (9) |

| Clinical outcomes | |

| Length of stay, median days (IQR) | 6 (4–9) |

| Direct admission to ICU | 78 (41) |

| ICU length of stay >72 h | 14 (7) |

| 90-d mortality | 33 (17) |

| 90-d hospital readmission | 66 (35) |

| 90-d mortality or readmission | 82 (43) |

Definition of abbreviations: ICU = intensive care unit; IQR = interquartile range.

Defined by maximum or minimum values for laboratory, physiologic, and mechanical ventilation measurements assessed within 24 hours of emergency department presentation.

Table 3 describes the postsepsis care received during inpatient and outpatient visits during and 90 days after the index hospitalization. Only 20 patients (11%) had documented receipt of all four recommended care elements. Performance on each care element ranged from 14% (mental health assessment) to 84% (appropriate antibiotic treatment). Each component of the optimization of medication care element was achieved in >75% of the patients. Performance of swallowing (14%) and mental health (24%) assessments was the lowest. Physical assessment was more frequently performed by a physical therapist (71%), but swallowing (58%) and mental health (96%) assessments were more commonly assessed subjectively and documented by a physician. When they were completed, nearly all care elements were performed as part of inpatient care during the index hospitalization. However, 10% of the patients (n = 22) had screening for common physical, functional, or mental health impairments documented during outpatient visits after hospital discharge.

Table 3.

Application of recommended postsepsis care elements

| Postsepsis Care Elements | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Optimize medications | |

| Appropriate medication management at discharge (discontinue/restart meds as needed) | 143 (76) |

| Adjust medication doses when needed (based on creatinine or body weight changes) | 154 (81) |

| Appropriate antibiotic selection, dose, and duration | 158 (84) |

| Element fulfilled: no medication management errors | 117 (62) |

| Screen for common deficits after sepsis | |

| Physical assessment | 123 (65)* |

| Swallowing assessment | 45 (24)† |

| Mental health assessment | 26 (14)‡ |

| Element fulfilled: physical plus swallowing and/or mental health assessment completed | 52 (28) |

| Anticipate and monitor for common and preventable causes of health deterioration | |

| Patient education about symptoms of sepsis and signs of recurrence | 119 (63) |

| Two-week follow-up completed | 102 (54) |

| Element fulfilled: both discharge education and timely follow-up completed | 86 (46) |

| Align treatment with patient preferences | |

| Document goals-of-care discussion | 71 (38) |

| Palliative care screen/consult | 75 (40) |

| Element fulfilled: palliative care screen or goals of care documented | 110 (58) |

| Number of recommended care elements documented | |

| None | 12 (6) |

| One | 28 (15) |

| Two | 59 (31) |

| Three | 70 (37) |

| Four | 20 (11) |

Physical assessment completed by physical therapist (87/123, 71%), otherwise physician-documented subjective assessment (36/123, 29%).

Swallowing assessment completed by speech therapist (19/45, 42%), otherwise physician-documented subjective assessment (26/45, 58%).

Mental health assessment completed using validated tool (e.g., Patient Health Questionnaire 2; 1/26, 4%), otherwise physician-documented subjective assessment (25/26, 96%).

Documented receipt of at least two of the postsepsis care elements was associated with lower odds of 90-day mortality or hospital readmission compared with no or one element documented (two: odds ratio [OR], 0.26, 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.10–0.69; three: OR, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.11–0.72; four: OR, 0.12; 95% CI, 0.03–0.50; Table 4). Patients whose medications were optimized experienced lower odds of 90-day mortality or readmission than those with medication errors (OR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.21–0.92). Patients with a documented physical assessment (OR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.17–1.04) and patients with a documented physical assessment plus a swallowing or mental health evaluation (OR, 0.14; 95% CI, 0.05–0.40) had lower odds of 90-day mortality or readmission than those without any documented assessments. Adherence to discharge education and timely follow-up was associated with a not statistically significant increase in the odds of the composite outcome (OR, 1.41; 95% CI, 0.68–2.95), and palliative-care screening or goals-of-care documentation was associated with a not statistically significant decrease in the odds of the composite outcome (OR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.25–1.05).

Table 4.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis to determine the independent associations between receipt of recommended postsepsis care elements and reduced 90-day hospital readmission and mortality

| Postsepsis Care Measures | Events/n | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of care elements documented | ||

| Zero or one (reference) | 26/40 | — |

| Two | 22/59 | 0.26 (0.10–0.69) |

| Three | 29/70 | 0.28 (0.11–0.72) |

| Four | 5/20 | 0.12 (0.03–0.50) |

| Individual care elements | ||

| Review and adjust medications | ||

| One or more medication management errors (reference) | 40/72 | — |

| No medication management errors | 42/117 | 0.44 (0.21–0.92) |

| Screen for common functional deficits after sepsis | ||

| No assessments documented (reference) | 32/66 | — |

| Physical assessment alone | 36/71 | 0.42 (0.17–1.04) |

| Physical plus swallowing and/or mental health assessment | 14/52 | 0.14 (0.05–0.40) |

| Monitor for common and preventable causes of health deterioration | ||

| Discharge education or timely follow-up not completed (reference) | 46/103 | — |

| Both discharge education and timely follow-up completed | 36/86 | 1.41 (0.68–2.95) |

| Align treatment with patient preferences | ||

| No care alignment process documented (reference) | 43/79 | — |

| Palliative care screen or goals of care documented | 39/110 | 0.52 (0.25–1.05) |

A separate analysis of hospital readmissions revealed that documented receipt of at least two of the recommended care elements was also associated with lower odds of 90-day readmission compared with no or one element documented (two: OR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.15–0.94; three: OR, 0.32; 95% CI, 0.13–0.77; four: OR, 0.10; 95% CI, 0.02–0.49; Table 5), and the results for each individual element were qualitatively similar to those obtained in the primary analysis.

Table 5.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis to determine the independent associations between receipt of recommended postsepsis care elements and reduced 90-d hospital readmission

| Postsepsis Care Measures | Events/n | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval)* |

|---|---|---|

| Number of care elements documented | ||

| Zero or one (reference) | 22/40 | — |

| Two | 19/59 | 0.38 (0.15–0.94) |

| Three | 22/70 | 0.32 (0.13–0.77) |

| Four | 3/20 | 0.10 (0.02–0.49) |

| Individual care elements | ||

| Review and adjust medications | ||

| One or more medication management errors (reference) | 32/72 | — |

| No medication management errors | 34/117 | 0.55 (0.27–1.15) |

| Screen for common functional deficits after sepsis | ||

| No assessments documented (reference) | 29/66 | — |

| Physical assessment alone | 25/71 | 0.30 (0.12–0.75) |

| Physical plus swallowing and/or mental health assessment | 12/52 | 0.19 (0.07–0.52) |

| Monitor for common and preventable causes of health deterioration | ||

| Discharge education or timely follow-up not completed (reference) | 38/103 | — |

| Both discharge education and timely follow-up completed | 28/86 | 1.16 (0.56–2.39) |

| Align treatment with patient preferences | ||

| No care alignment process documented (reference) | 36/79 | — |

| Palliative care screen or goals of care documented | 30/110 | 0.48 (0.24–0.96) |

Adjusted for age, comorbidity burden, length of stay, and discharge disposition.

Discussion

In this retrospective cohort study of data from a single health system, we found that application of postsepsis care elements for survivors was low, and that considerable variability in application existed across each measure (ranging from 17% to 85%). Patients were most likely to receive the optimization of medications care element, likely because medication reconciliation is currently a focus of institution-wide quality improvement efforts (40). This element is critically important, as medication errors and risky medication use are common in high-risk ICU survivors (41, 42). Employment of dedicated critical care pharmacists in an ICU recovery clinic has been shown to be a successful strategy for effectively addressing medication optimization in survivors of a general critical illness (42).

Conversely, rates of screening for new physical, functional, or mental health deficits were low, perhaps because of a lack of awareness of the downstream consequences of cognitive, physical, and psychological challenges in patients discharged after sepsis (11–14, 16). Despite low application, screening for functional, swallowing, and/or mental health impairments was associated with reductions in 90-day mortality and readmissions, suggesting the potential benefit of renewed attention to this element. Unfortunately, we were not able to assess what interventions occurred in response to the screening, and which of these interventions may have been associated with improved outcomes.

Although the results were not statistically significant, patients with timely follow-up had higher rates of 90-day mortality and readmission. Given that over 40% of sepsis readmissions are reported to be due to ambulatory-sensitive conditions, we would expect early identification and treatment of these conditions to lower hospitalization rates (25). However, the ultimate preventability of readmissions due to these conditions is controversial (43). Because sepsis survivors are at risk for serious complications, including recurrent sepsis, rehospitalization may be an appropriate and necessary action taken by an outpatient provider. Our analysis did not include a detailed evaluation of follow-up visits to make this determination.

Our study adds to the literature that supports a role for palliative care in a subset of sepsis survivors. Because sepsis often occurs in the setting of worsening health and multiple chronic conditions, a hospitalization for sepsis may serve as an important trigger for assessing the patient’s treatment goals (44–46). We found that a palliative care consultation or documented goals-of-care discussion with the appropriate patients was associated with a reduced likelihood of readmission within 90 days, representing an important goal of patient-centered care (47). Unfortunately, we observed that palliative care consultations or documented goals-of-care discussions occurred in fewer than half of the appropriate patients with sepsis. In a time of strained specialty palliative care resources (48), investigators should seek to determine effective and efficient strategies for providing quality palliative care to appropriate sepsis survivors.

Our results showing variable application of postsepsis care elements and associations with improved outcomes highlight the need to develop and empirically test implementation strategies for delivering recommended postsepsis care. At the forefront of this challenge is the development of reliable predictive models to select patients who would be most likely to benefit from targeted recovery programs (49). Outpatient ICU follow-up clinics with or without a specific focus on sepsis have been gaining attention worldwide as a means of improving postdischarge outcomes for survivors of serious illnesses (50, 51). However, although some qualitative, intermediate outcomes have been improved, the current model of outpatient clinic follow-up after ICU discharge does not seem to provide significant benefits to patients and likely is not cost-effective (52). Haines and colleagues have identified several barriers that limit the widespread implementation of strategies such as ICU follow-up clinics and post–critical illness peer support programs, including lack of access to clinics and inadequate funding (53). An alternative, high-value model may involve the delivery of effective elements of postsepsis care through a centralized telephone-based or telemedicine program. A randomized clinical trial is currently underway to test the effectiveness of this approach (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03865602).

Our study has several strengths. The meticulous manual chart review provided information about provided care that could not be electronically extracted from EHR data. This study addressed an important yet understudied issue, and it is hoped that the results will provide a foundation for future efforts to improve outcomes for sepsis survivors.

We note several limitations to our study. First, we acknowledge that the postsepsis care elements we studied were drawn from expert opinion, not evidence-based guidelines. Second, our small sample size limited the complexity of the models we used to predict 90-day mortality and readmissions. Third, we did not measure interrater reliability for the abstracted care elements, although the rate of uncertainty was low. Fourth, our approach technically suggests an association between documentation of recommended care and improved outcomes, not necessarily an association between actual care delivered and outcomes. For example, providers may have performed a recommended assessment or intervention without documenting it in the EHR. Fifth, we could not identify a standardized method to assess whether a cognitive evaluation was performed, so we did not address that important factor in this study. Sixth, immortal time bias could have affected our results; however, this concern is mitigated by the high proportion of patients who received care elements in the inpatient setting before discharge. Seventh, we were only able to capture outpatient follow-up and readmission data that occurred within our own healthcare system (although our healthcare system has a large market share in the areas studied). Finally, there are many complex and uncertain factors in the pathway between these care practices and outcomes such as mortality and readmissions, which makes a true assessment of causal inference problematic. Thus, the associations we report between adherence to care processes and improved outcomes for sepsis survivors can be interpreted as hypothesis generating.

Conclusions

In this study of patients who were discharged after an episode of sepsis, we found that adherence to recommended postsepsis care practices was associated with a reduced likelihood of composite mortality or readmission within 90 days. However, current adherence to practice recommendations was variable. These results highlight the need to develop and empirically test implementation strategies for delivering recommended postsepsis care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the multidisciplinary collaboration of the Atrium Health Acute Care Outcomes Research Network Investigators listed here (in alphabetical order): Ryan Brown, M.D.; Larry Burke, M.D.; Shih-Hsiung Chou, Ph.D.; Kyle Cunningham, M.D.; Susan L. Evans, M.D.; Scott Furney, M.D.; Michael Gibbs, M.D.; Alan Heffner, M.D.; Timothy Hetherington, M.S.; Daniel Howard, M.D.; Marc Kowalkowski, Ph.D.; Scott Lindblom, M.D.; Andrea McCall; Lewis McCurdy, M.D.; Andrew McWilliams, M.D., M.P.H.; Stephanie Murphy, D.O.; Alfred Papali, M.D.; Christopher Polk, M.D.; Whitney Rossman, M.S.; Michael Runyon, M.D.; Mark Russo, M.D.; Melanie Spencer, Ph.D.; Brice Taylor, M.D.; and Stephanie Taylor, M.D., M.S.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Study concept and design: S.P.T. and M.A.K. Acquisition of data: S.P.T., M.F.S., and T.P.S. Data analysis: M.A.K. Interpretation of data: all authors. Drafting of the manuscript: S.P.T. and M.A.K. Critical revision of manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. S.P.T. and M.A.K. had full access to the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis, and are the guarantors of the content of this manuscript.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Fleischmann C, Scherag A, Adhikari NK, Hartog CS, Tsaganos T, Schlattmann P, et al. International Forum of Acute Care Trialists. Assessment of global incidence and mortality of hospital-treated sepsis. current estimates and limitations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:259–272. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201504-0781OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, Levy MM, Antonelli M, Ferrer R, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:304–377. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4683-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaukonen KM, Bailey M, Suzuki S, Pilcher D, Bellomo R. Mortality related to severe sepsis and septic shock among critically ill patients in Australia and New Zealand, 2000-2012. JAMA. 2014;311:1308–1316. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyer N, Harhay MO, Small DS, Prescott HC, Bowles KH, Gaieski DF, et al. Temporal trends in incidence, sepsis-related mortality, and hospital-based acute care after sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:354–360. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iwashyna TJ, Cooke CR, Wunsch H, Kahn JM. Population burden of long-term survivorship after severe sepsis in older Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:1070–1077. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03989.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iwashyna TJ. Survivorship will be the defining challenge of critical care in the 21st century. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:204–205. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-3-201008030-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iwashyna TJ, Netzer G, Langa KM, Cigolle C. Spurious inferences about long-term outcomes: the case of severe sepsis and geriatric conditions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:835–841. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201109-1660OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehlenbach WJ, Gilmore-Bykovskyi A, Repplinger MD, Westergaard RP, Jacobs EA, Kind AJH, et al. Sepsis survivors admitted to skilled nursing facilities: cognitive impairment, activities of daily living dependence, and survival. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:37–44. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davydow DS, Hough CL, Langa KM, Iwashyna TJ. Symptoms of depression in survivors of severe sepsis: a prospective cohort study of older Americans. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21:887–897. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Battle CE, James K, Bromfield T, Temblett P. Predictors of post-traumatic stress disorder following critical illness: a mixed methods study. J Intensive Care Soc. 2017;18:289–293. doi: 10.1177/1751143717713853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borges RC, Carvalho CR, Colombo AS, da Silva Borges MP, Soriano FG. Physical activity, muscle strength, and exercise capacity 3 months after severe sepsis and septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41:1433–1444. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-3914-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Annane D, Sharshar T. Cognitive decline after sepsis. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3:61–69. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70246-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwashyna TJ, Ely EW, Smith DM, Langa KM. Long-term cognitive impairment and functional disability among survivors of severe sepsis. JAMA. 2010;304:1787–1794. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hensley MK, Prescott HC. Bad brains, bad outcomes: acute neurologic dysfunction and late death after sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:1001–1002. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prescott HC, Iwashyna TJ, Blackwood B, Calandra T, Chlan LL, Choong K, et al. Understanding and enhancing sepsis survivorship. Priorities for research and practice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200:972–981. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201812-2383CP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prescott HC, Angus DC. Enhancing recovery from sepsis: a review. JAMA. 2018;319:62–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.17687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang CY, Daniels R, Lembo A, Hartog C, O’Brien J, Heymann T, et al. Sepsis Survivors Engagement Project (SSEP) Life after sepsis: an international survey of survivors to understand the post-sepsis syndrome. Int J Qual Health Care. 2019;31:191–198. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzy137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodwin AJ, Rice DA, Simpson KN, Ford DW. Frequency, cost, and risk factors of readmissions among severe sepsis survivors. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:738–746. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Winters BD, Eberlein M, Leung J, Needham DM, Pronovost PJ, Sevransky JE. Long-term mortality and quality of life in sepsis: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:1276–1283. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181d8cc1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nesseler N, Defontaine A, Launey Y, Morcet J, Mallédant Y, Seguin P. Long-term mortality and quality of life after septic shock: a follow-up observational study. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:881–888. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-2815-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prescott HC, Osterholzer JJ, Langa KM, Angus DC, Iwashyna TJ. Late mortality after sepsis: propensity matched cohort study. BMJ. 2016;353:i2375. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prescott HC, Langa KM, Liu V, Escobar GJ, Iwashyna TJ. Increased 1-year healthcare use in survivors of severe sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:62–69. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201403-0471OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu V, Lei X, Prescott HC, Kipnis P, Iwashyna TJ, Escobar GJ. Hospital readmission and healthcare utilization following sepsis in community settings. J Hosp Med. 2014;9:502–507. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones TK, Fuchs BD, Small DS, Halpern SD, Hanish A, Umscheid CA, et al. Post-acute care use and hospital readmission after sepsis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:904–913. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201411-504OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prescott HC, Langa KM, Iwashyna TJ. Readmission diagnoses after hospitalization for severe sepsis and other acute medical conditions. JAMA. 2015;313:1055–1057. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bell CM, Brener SS, Gunraj N, Huo C, Bierman AS, Scales DC, et al. Association of ICU or hospital admission with unintentional discontinuation of medications for chronic diseases. JAMA. 2011;306:840–847. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scales DC, Fischer HD, Li P, Bierman AS, Fernandes O, Mamdani M, et al. Unintentional continuation of medications intended for acute illness after hospital discharge: a population-based cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31:196–202. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3501-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Connolly B, O’Neill B, Salisbury L, Blackwood B Enhanced Recovery After Critical Illness Programme Group. Physical rehabilitation interventions for adult patients during critical illness: an overview of systematic reviews. Thorax. 2016;71:881–890. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-208273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Major ME, Kwakman R, Kho ME, Connolly B, McWilliams D, Denehy L, et al. Surviving critical illness: what is next? An expert consensus statement on physical rehabilitation after hospital discharge. Crit Care. 2016;20:354. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1508-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones C, Bäckman C, Capuzzo M, Egerod I, Flaatten H, Granja C, et al. RACHEL group. Intensive care diaries reduce new onset post traumatic stress disorder following critical illness: a randomised, controlled trial. Crit Care. 2010;14:R168. doi: 10.1186/cc9260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mikkelsen ME, Jackson JC, Hopkins RO, Thompson C, Andrews A, Netzer G, et al. Peer support as a novel strategy to mitigate post-intensive care syndrome. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2016;27:221–229. doi: 10.4037/aacnacc2016667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, De Mendonça A, Bruining H, et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22:707–710. doi: 10.1007/BF01709751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rhee C, Zhang Z, Kadri SS, Murphy DJ, Martin GS, Overton E, et al. CDC Prevention Epicenters Program. Sepsis surveillance using adult sepsis events simplified eSOFA criteria versus Sepsis-3 sequential organ failure assessment criteria. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:307–314. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Infectious Diseases Society of America. IDSA practice guidelines [accessed 2019 Jul 7]. Available from: https://www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/practice-guidelines.

- 36.Morandi A, Vasilevskis E, Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Solberg LM, Neal EB, et al. Inappropriate medication prescriptions in elderly adults surviving an intensive care unit hospitalization. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:1128–1134. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weissman DE, Meier DE. Identifying patients in need of a palliative care assessment in the hospital setting: a consensus report from the Center to Advance Palliative Care. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:17–23. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sabbatini AK, Wright B. Excluding observation stays from readmission rates—what quality measures are missing. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2062–2065. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1800732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rhee C, Jones TM, Hamad Y, Pande A, Varon J, O’Brien C, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Prevention Epicenters Program. Prevalence, underlying causes, and preventability of sepsis-associated mortality in US acute care hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e187571. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.7571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Redmond P, Grimes TC, McDonnell R, Boland F, Hughes C, Fahey T. Impact of medication reconciliation for improving transitions of care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;8:CD010791. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010791.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stollings JL, Bloom SL, Huggins EL, Grayson SL, Jackson JC, Sevin CM. Medication management to ameliorate post-intensive care syndrome. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2016;27:133–140. doi: 10.4037/aacnacc2016931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stollings JL, Bloom SL, Wang L, Ely EW, Jackson JC, Sevin CM. Critical care pharmacists and medication management in an ICU recovery center. Ann Pharmacother. 2018;52:713–723. doi: 10.1177/1060028018759343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Purdy S, Griffin T, Salisbury C, Sharp D. Ambulatory care sensitive conditions: terminology and disease coding need to be more specific to aid policy makers and clinicians. Public Health. 2009;123:169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nasa P, Juneja D, Singh O. Severe sepsis and septic shock in the elderly: an overview. World J Crit Care Med. 2012;1:23–30. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v1.i1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rowe TA, McKoy JM. Sepsis in older adults. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2017;31:731–742. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2017.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kadri SS, Rhee C, Strich JR, Morales MK, Hohmann S, Menchaca J, et al. Estimating ten-year trends in septic shock incidence and mortality in United States academic medical centers using clinical data. Chest. 2017;151:278–285. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Teno JM, Fisher ES, Hamel MB, Coppola K, Dawson NV. Medical care inconsistent with patients’ treatment goals: association with 1-year Medicare resource use and survival. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:496–500. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kamal AH, Maguire JM, Meier DE. Evolving the palliative care workforce to provide responsive, serious illness care. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:637–638. doi: 10.7326/M15-0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brown SM, Bose S, Banner-Goodspeed V, Beesley SJ, Dinglas VD, Hopkins RO, et al. Addressing Post Intensive Care Syndrome 01 (APICS-01) study team. Approaches to addressing post-intensive care syndrome among intensive care unit survivors. A narrative review. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019;16:947–956. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201812-913FR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lasiter S, Oles SK, Mundell J, London S, Khan B. Critical care follow-up clinics: a scoping review of interventions and outcomes. Clin Nurse Spec. 2016;30:227–237. doi: 10.1097/NUR.0000000000000219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Modrykamien AM. The ICU follow-up clinic: a new paradigm for intensivists. Respir Care. 2012;57:764–772. doi: 10.4187/respcare.01461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schmidt K, Worrack S, Von Korff M, Davydow D, Brunkhorst F, Ehlert U, et al. SMOOTH Study Group. Effect of a primary care management intervention on mental health-related quality of life among survivors of sepsis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315:2703–2711. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.7207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Haines KJ, McPeake J, Hibbert E, Boehm LM, Aparanji K, Bakhru RN, et al. Enablers and barriers to implementing ICU follow-up clinics and peer support groups following critical illness: the Thrive Collaboratives. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:1194–1200. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.