Abstract

Objective

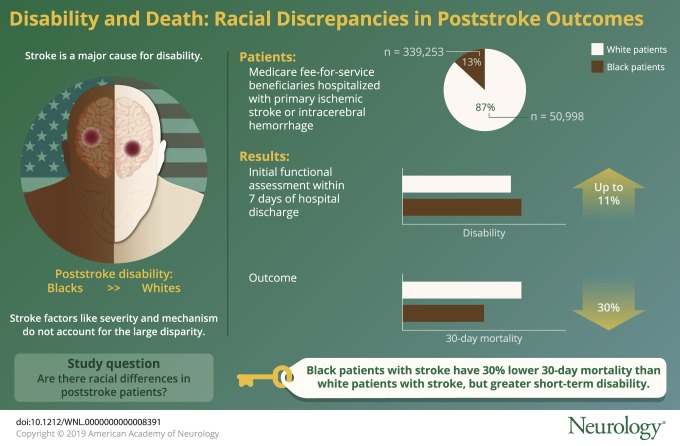

To explore racial differences in disability at the time of first postdischarge disability assessment.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study of all Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries hospitalized with primary ischemic stroke (ICD-9,433.x1, 434.x1, 436) or intracerebral hemorrhage (431) diagnosed from 2011 to 2014. Racial differences in poststroke disability were measured in the initial postacute care setting (inpatient rehabilitation facility, skilled nursing facility, or home health) with the Pseudo-Functional Independence Measure. Given that assignment into postacute care setting may be nonrandom, patient location during the first year after stroke admission was explored.

Results

A total of 390,251 functional outcome assessments (white = 339,253, 87% vs black = 50,998, 13%) were included in the primary analysis. At the initial functional assessment, black patients with stroke had greater disability than white patients with stroke across all 3 postacute care settings. The difference between white and black patients with stroke was largest in skilled nursing facilities (black patients 1.8 points lower than white patients, 11% lower) compared to the other 2 settings. Conversely, 30-day mortality was greater in white patients with stroke compared to black patients with stroke (18.4% vs 12.6% [p < 0.001]) and a 3 percentage point difference in mortality persisted at 1 year. Black patients with stroke were more likely to be in each postacute care setting at 30 days, but only very small differences existed at 1 year.

Conclusions

Black patients with stroke have 30% lower 30-day mortality than white patients with stroke, but greater short-term disability. The reasons for this disconnect are uncertain, but the pattern of reduced mortality coupled with increased disability suggests that racial differences in care preferences may play a role.

Stroke is a leading cause of disability. Substantial racial differences in stroke incidence1,2 and poststroke functioning exist, with black patients experiencing greater levels of poststroke disability than white patients in the United States.3 Yet the reasons for these differences and when they arise are unknown. Ultimately, a better understanding of when racial differences arise may inform the causes of these differences and suggest targeted interventions to improve stroke outcomes, particularly in black patients with stroke.

Numerous factors may contribute to racial differences in stroke outcomes. Given that many putative factors operate on different timescales, determining when differences emerge (i.e., prestroke, during the acute stroke period, poststroke) is a key step in determining which factors are most important. Prestroke racial differences in disability are small or nonexistent and the greatest differences in poststroke disability emerge in the first 2 years after stroke.4,5 However, a more fine-grained temporal understanding is lacking. While the acute stroke period is the most obvious time period for race differences to arise, the small differences among candidate factors—stroke severity, mechanism, or quality of acute care—are too small to account for the large differences in disability.6–9 These findings suggest that the key drivers of poststroke racial differences are either unexplored factors in the acute period or factors operating in the poststroke period, a period where our understanding is incomplete due to survivor bias, single community studies, and coarse temporal resolution.8–10

Our main objective was to determine whether, and to what extent, racial differences in poststroke disability are detectable at the time of the first available rehabilitation assessment. If, for example, marked differences are identified at the time of initial rehabilitation assessment, then it would point to timely access or hospital care as likely contributing factors. Conversely, if no major differences exist, it would suggest that rehabilitation, quality of outpatient care, or factors related to functioning in the home or community are more likely contributors. To explore this objective, we utilized the Pseudo-Functional Independence Measure (Pseudo-FIM) score—an overall assessment of functioning in activities of daily living (ADL) and motor function—with lower scores representing greater disability and increased dependence. In addition, given that stroke survivors are nonrandomly assigned to postacute care settings and that the mechanisms of assignment are uncertain, we also explored racial differences in location (including mortality) in the year after discharge.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries hospitalized after ischemic stroke or intracerebral hemorrhage from 2011 to 2014. Our primary outcome was disability (measured in Medicare functional assessment files). In addition, assessing for differential selection into physical location by time (inferred from Medicare standard analytic files) was explored. For both analyses, our primary question was whether racial differences existed. This study was reviewed by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board and considered exempt.

Data sources

Stroke hospitalizations were identified from the Medicare Inpatient file and subsequent claims were identified within that population. For individuals with multiple stroke hospitalizations, only the first hospitalization was used for analysis. Two different groups of Medicare files were used. First, Medicare functional assessment files were used to estimate disability in stroke survivors in different rehabilitation settings. For Medicare beneficiaries admitted to an inpatient rehabilitation facility (IRF) or skilled nursing facility (SNF) or enrolled in home health (home health aide [HHA]), corresponding functional assessments are recorded in functional assessment files: IRF patient assessment, Minimum Data Set (MDS), and outcome and assessment information set (OASIS). While the details of the functional assessments differ somewhat between settings, it is feasible to crosswalk items across settings representing motor function and performance of ADL.

Second, Medicare standard analytic files were used to infer a patient with stroke’s location in the year after stroke. These files include information on whether a stroke patient was in a given setting at a given time. The specific files used were inpatient (which includes visits at short-stay hospitals, IRF, and long-term care hospital [LTCH]), SNF, and HHA. The Medicare Beneficiary Summary file was used to identify mortality.

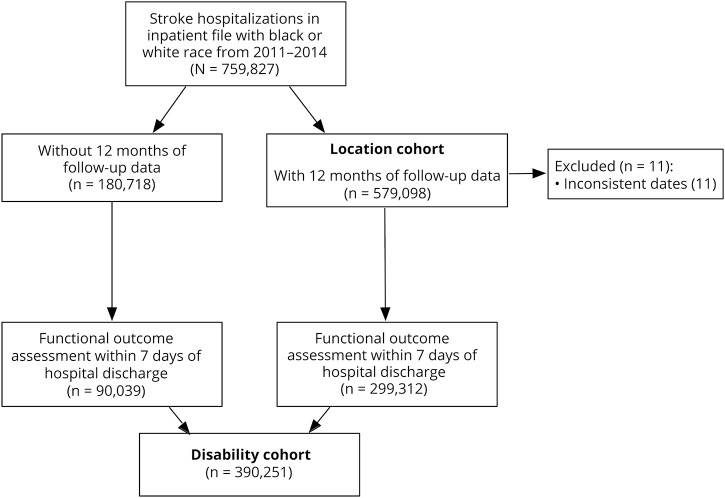

Cohort definition

Stroke survivors were identified if they had an acute ischemic stroke or intracerebral hemorrhage hospitalization with a primary ICD-9 code of 431, 433.x1, 434.x1, or 436.11–14 Two overlapping patient cohorts were used as illustrated in figure 1. First, patients were included in the disability cohort (n = 390,251) if they had a functional assessment performed within 7 days of hospital discharge. Functional assessments were only performed for patients who were discharged to an IRF, SNF, or HHA and no assessments were performed for patients who were discharged home without HHA, died in the hospital, or discharged to hospice or to other less common settings. Missing functional assessments were very rare. Among patients discharged to a setting where functional assessments were performed, assessments were missing in <1% of cases. Second, patients were included in the location cohort if they died or had 12 months of longitudinal follow-up available. Thus, stroke survivors hospitalized in 2014 were excluded. Race was identified using Medicare data, which is, itself, drawn from social security data. Individuals were excluded form analyses if they had a reported race/ethnicity other than white or black.

Figure 1. Patient selection flowchart for the location and disability cohorts.

Outcome: Disability measured by Medicare functional assessments

Medicare mandates that functional assessments are intermittently completed for Medicare patients receiving rehabilitation in any postacute care setting. The requirements for reporting vary across settings, but admission assessments are mandatory in all 3 settings. Three different, but similar, instruments were in use for the 3 primary postacute care settings (IRF, SNF, HHA) to evaluate the functional status of stroke survivors.

Functional Independence Measure (FIM) (IRF) to Pseudo-FIM (MDS) crosswalk

Stroke patients in IRFs are assessed with the FIM, an 18-item measure grouped into a motor subset (13 items) consisting of self-care (6 items), mobility (5 items), and bowel/bladder management (2 items) questions and a cognition subscale.15,16 Each item is scored on a scale of 1–7, with higher scores representing greater independence. Patients with stroke in SNFs are assessed with a functional assessment analogous to most FIM items, although on a different scale (most commonly a 5-item scale with lower scores representing greater independence) and recorded in the MDS. Prior work has built a crosswalk between the FIM and the MDS functional assessment, the Pseudo-FIM,17 which is constrained to the items most closely analogous between settings (6 self-care items, 2 bowel/bladder items, and communication/cognitive items). Pseudo-FIM subscores for motor (self-care and bowel/bladder, maximum score of 56), ADL (self-care, maximum score of 49), and cognition have been developed.17 We constrained our analyses to motor and ADL Pseudo-FIM subscores because of frequent missing data on cognitive items in MDS.

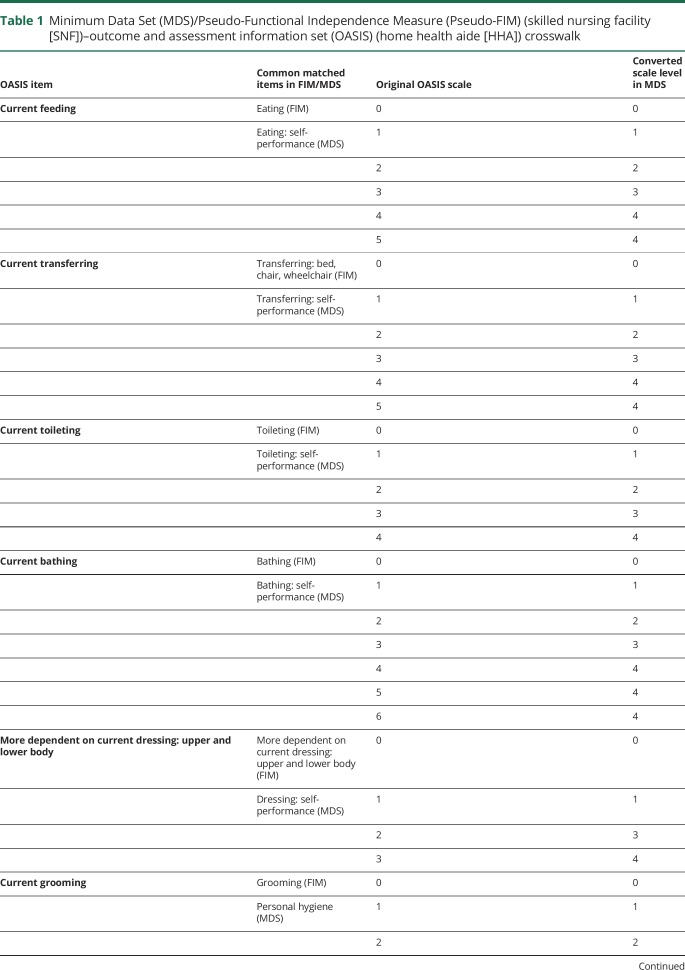

Pseudo-FIM (MDS) to OASIS (HHA) crosswalk

Patients with stroke receiving home health are assessed with a functional assessment measure similar to the Pseudo-FIM (MDS) functional assessment measure, but differ slightly in how items are scaled. Table 1 demonstrates how we crosswalked Pseudo-FIM measures to the OASIS measures obtained in the HHA setting to estimate the Pseudo-FIM (and subscores) in the HHA. In the Pseudo-FIM and crosswalked Pseudo-FIM measure in OASIS, if an item was missing at the admission assessment and reported in a subsequent assessment, we replaced the missing value with the subsequently reported value. Our primary functional outcome, then, is the Pseudo-FIM measure defined across all 3 settings. In the IRF setting, we applied the Pseudo-FIM crosswalk to the FIM instrument to define the Pseudo-FIM. In the SNF setting (recorded in the MDS), we directly calculated the Pseudo-FIM. In the HHA setting (recorded in the OASIS dataset), we applied our Pseudo-FIM to OASIS crosswalk to identify a Pseudo-FIM value for each individual in this setting.

Table 1.

Minimum Data Set (MDS)/Pseudo-Functional Independence Measure (Pseudo-FIM) (skilled nursing facility [SNF])–outcome and assessment information set (OASIS) (home health aide [HHA]) crosswalk

Outcome: Location over time

Prior work has shown that there are no racial differences in the pattern of postacute care utilization among stroke survivors in the Medicare population.18 However, because the process for selection into a given postacute care setting is both complex and poorly understood, we comprehensively assessed patient location in the year after stroke. The primary goal of this analysis was to determine whether, and to what extent, racial differences in selection into different settings may influence our disability analyses. To infer patient location over time, we relied on Medicare standard analytic files: inpatient, SNF, and HHA. Every time a stroke survivor is admitted to one of these settings, a record in the standard analytic file records the date of entering and leaving that setting. Stroke survivors were assigned to one of 6 decreasingly intense locations over time: inpatient, LTCH, IRF, SNF, home with HHA, or home. Separately, we tracked patient mortality using the Medicare Beneficiary Summary File. For survivors, a record of all standard analytic claims throughout the year was assembled. The time entering a given setting was determined with the “claim from date” and the time leaving a given setting with the “claim through date.” IRF, LTCH, and inpatient stays are all reported in the inpatient file and are all differentiated by provider numbers (3025–3099 or TR representing IRF, 0001–0879 representing acute hospitalizations, and 2200–2299 representing LTCH). If a patient was listed in multiple settings on the same date (e.g., discharged from the inpatient setting the same day as being admitted to a SNF), he or she was assigned to the most intense setting. If no claim dates spanned a given date, an individual was assigned to home. For this outcome, our cohort excluded individuals who did not have 12 consecutive months of Medicare fee-for-service claims available (n = 180,718).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize location over time by race. Admission motor and ADL Pseudo-FIMs, across all settings and within settings by race, were also compared using descriptive statistics. To explore whether the use of the Pseudo-FIM influences our inferences across rehabilitation settings, we also described each individual scaled item across settings by race. To explore the extent to which functional assessments were influenced by patient-level factors prior to rehabilitation, we built setting-specific multilevel linear regression models to predict the dependent variable, motor Pseudo-FIM subscore, accounting for patient demographics (age, sex, race), comorbidities (all individual Charlson comorbidities), characteristics of the initial hospitalization (length of stay, receipt of tissue plasminogen activator or mechanical thrombectomy), and the use of life-sustaining treatment (intubation/mechanical ventilation, tracheostomy, gastrostomy, hemodialysis, cardiopulmonary resuscitation).19 To account for facility-level variation in functional outcome assessment, each model included a random facility-level intercept unique to each rehabilitation provider (IRF, SNF, or HHA). Finally, to explore heterogeneity in outcomes by race in subpopulations of patients, we also explored 1-year mortality stratified by quintiles of hospital length of stay (as a crude proxy for stroke severity), age, and whether a gastrostomy tube was placed in the initial hospitalization. Statistical analysis was done using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Data availability

The data underlying these analyses cannot be shared. They were made available to investigators and stored on secured servers at the University of Michigan based on a data use agreement with Medicare that precludes data sharing.

Results

Characteristics of stroke survivors included in the disability analysis

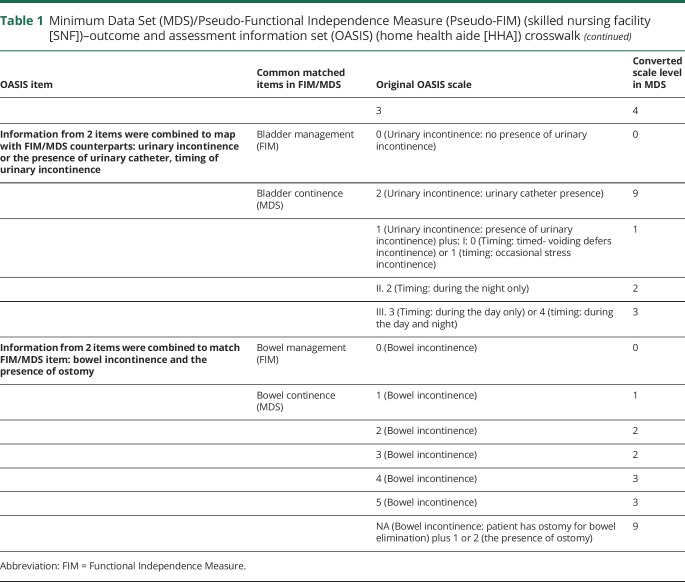

A total of 759,827 stroke hospitalizations occurred among black and white patients with stroke from 2011 to 2014. Of these, 390,251 had a functional outcome assessment in any setting within 7 days of hospital discharge and were included in the disability cohort (figure 1). Black patients with stroke were more likely to be women (63% vs 61%) and younger (mean age 77 vs 81) and had longer length of stay in the hospital (7.3 vs 6.3) and more procedures (gastrostomy tube in 10% vs 6%) than white patients with stroke (table 2). There were no consistent racial patterns across comorbidities. The most striking difference in comorbidities by race was in the proportion of stroke survivors with diabetes (41% in black patients vs 27% in white patients with uncomplicated diabetes and 9% in black patients vs 5% in white patients with complicated diabetes).

Table 2.

Patient characteristics in disability cohort by race

Function in initial rehabilitation setting by race

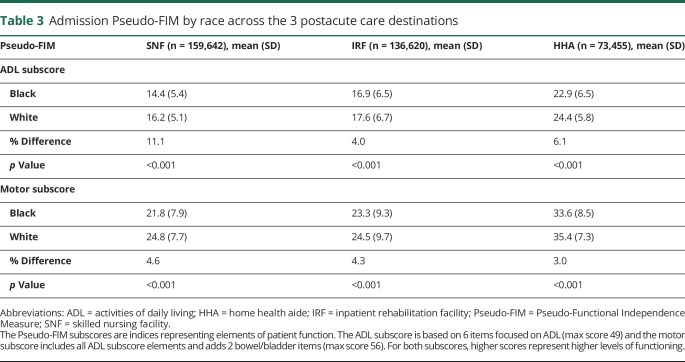

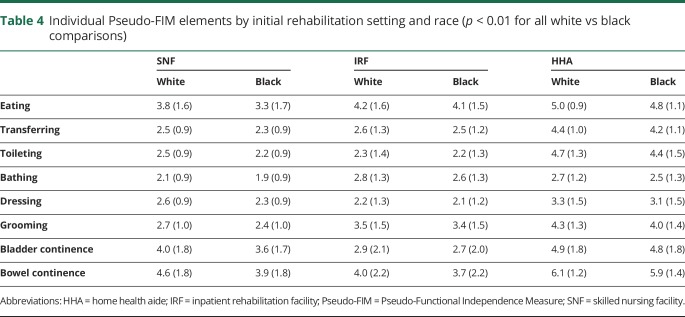

Across all 3 postacute care settings, black patients with stroke had lower Pseudo-FIM scores (greater disability) on admission than white patients with stroke (table 3). The difference in Pseudo-FIM scores between white and black patients with stroke was largest in SNFs (black patients had 1.8 points lower than white patients, 11% lower) compared to the other 2 settings. In each setting, across all items in the motor Pseudo-FIM subscore, black patients with stroke had lower functional ratings (p < 0.001). While the magnitude of the difference was statistically significant for all individual elements, the absolute differences are very small for some elements and likely not of clinical significance when considered individually (table 4). The largest observed racial difference was on the eating subelement (0.5 point lower in black patients than in white patients; 13% lower relatively). There were no major differences in the probability of having an initial functional assessment performed in any given setting, out of the whole sample (SNF 43% white vs 43% black, IRF 37% vs 36%, and HHA 20% vs 21%).

Table 3.

Admission Pseudo-FIM by race across the 3 postacute care destinations

Table 4.

Individual Pseudo-FIM elements by initial rehabilitation setting and race (p < 0.01 for all white vs black comparisons)

Adjusted function by race

In all 3 settings, racial differences in motor Pseudo-FIM persisted in their direction and level of statistical significance after adjustment for demographics, hospitalization characteristics (including the use of life-sustaining treatment), comorbidities, and stroke treatment, although they were generally slightly attenuated. For example, the 1.8-point difference in unadjusted motor Pseudo-FIM in the SNF setting was only minimally altered (1.7 [95% confidence interval 1.6–1.8]) after full covariate adjustment.

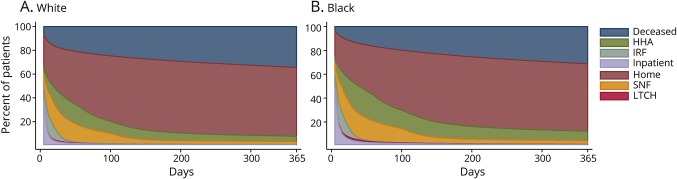

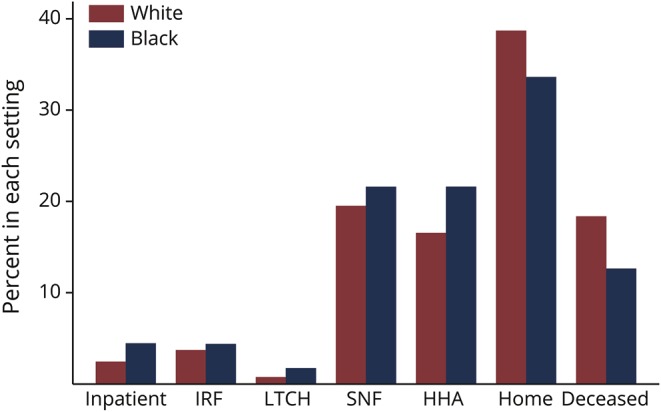

Stroke survivor location by race in the year after stroke discharge

Complete claims follow-up (or mortality data) was available for 579,098 unique patients discharged after a stroke hospitalization (white = 509,503, 88% vs black = 69,595, 12%) for inclusion in the location cohort. Stroke patient location across all settings by race in the year after stroke is illustrated in figure 2. While the general pattern of change in location over time was similar by race, there were differences in location, particularly shortly after discharge from the hospital (figure 3). Thirty-day mortality was greater in white patients with stroke compared to black patients with stroke (18.4% vs 12.6%, p < 0.001). Overall, hospital mortality was somewhat higher in white patients than in black patients with stroke (7.7% vs 6.2%, p < 0.001), while hospice utilization was considerably greater (6.8% vs 4.0%, p < 0.001). Mortality remained higher in white than in black patients with stroke over the subsequent year, although the magnitude of the difference attenuated: 34.2% vs 31.1% (p < 0.001). An inverse pattern was observed in the likelihood of living at home: 38.7% of white patients with stroke vs 33.6% of black patients with stroke were living at home at 30 days (p < 0.001), although this difference only modestly persisted 1 year poststroke (58.0% vs 56.5%) (p < 0.001). White patients were slightly less likely than black patients to be in each institutional setting 30 days after a stroke discharge (LTCH: 0.8% vs 1.7%, p < 0.001; SNF: 19.5% vs 21.6%, p < 0.001; IRF: 3.7% vs 4.4%, p < 0.001; HHA: 16.5% vs 21.6, p < 0.001) and only very small differences existed at 1 year. Qualitatively, Kaplan-Meier curves stratified by initial hospital length of stay, age, and gastrostomy tube placement were similar by race.

Figure 2. Distribution of locations of patients with stroke in the first year following a stroke admission by race.

(A) White patients (n = 509,503). (B) Black patients (n = 69,595). HHA = home health aide; IRF = inpatient rehabilitation facility; LTCH = long-term care hospital; SNF = skilled nursing facility.

Figure 3. Location of white and black stroke patients at 30 days.

HHA = home health aide; IRF = inpatient rehabilitation facility; LTCH = long-term care hospital; SNF = skilled nursing facility.

Discussion

In this large cohort of Medicare patients with stroke, we found that black patients are more than 30% less likely to die than white patients within 30 days, but, this mortality benefit is at least partially offset by greater poststroke disability. The magnitude of the racial difference in short-term mortality is large—more than double the magnitude of the effect of thrombectomy on survival in patients with stroke with large vessel occlusion.20 To understand the factors giving rise to these short-term outcome differences, a nuanced explanation is needed as most simple explanations (i.e., racial differences in stroke severity or consistently higher or lower quality of care by race) lead to both greater mortality and disability. Thus, the explanation for the observed mortality–disability divergence requires either multiple independent factors converging or a unifying factor that could result in a trade-off between disability and mortality.

One possible unifying theory that may explain the divergence between mortality and disability are patient preferences for life-sustaining treatment. Black patients generally have more aggressive preferences for care in the face of survival with severe disability21 and receive more life-sustaining treatment after stroke,22 a finding replicated in our data. To the extent that acute stroke care necessitates trade-offs between survival with severe disability and death, differences in preferences for care could explain the divergence between disability and mortality. If, for example, a white patient with stroke is more likely to opt for comfort measures when faced with severe persistent dysphagia and a black stroke patient with similar clinical deficits is more likely to opt for placement of a gastrostomy tube, lower mortality but higher disability would be expected. The findings that, compared to white patients, black patients with stroke had longer hospitalizations and were more likely to receive life-sustaining treatment, be discharged to long-term care hospitals, and were less likely to be discharged to hospice support the preferences hypothesis. Future work to measure racial differences in care delivery, particularly among severe stroke survivors, with a focus on decisions regarding de-escalation of care in the inpatient setting and transitions between inpatient and postacute care settings is needed. A related hypothesis is that black patients with stroke may be more likely than white patients with stroke to receive care in hospitals with stronger preferences for life-sustaining treatment (for which there is limited evidence),23,24 or decreased use of palliative care or other limitations of care, for which there is more evidence.25 Differentiating between patient and hospital-level hypotheses is challenging, though. At a minimum, it requires understanding the relationship between an individual's preferences for life-sustaining treatment (optimally, measured before the stroke hospitalization) while accounting for the numerous other factors that may correlate with both preferences and disability (e.g., age, disease severity, hospital practice patterns). Given that it is difficult to predict who will subsequently have a stroke, this likely requires measuring preferences for life-sustaining treatment in a large sample of older adults.

While we found that black patients with stroke have more disability than white patients at their initial discharge assessment, the magnitude of this difference is smaller than has been observed in cross-sectional studies. We found that initial posthospital disability was between 5% and 10% higher in black than in white patients with stroke, but cross-sectional studies have typically found larger differences in functional outcomes. For example, in a cross-sectional analysis of the National Health Aging and Trends Study (NHATS), we previously found 25%–60% more disability in black stroke survivors than white stroke survivors,3 a finding consistent with analyses in other samples.26,27 A possible interpretation is that the prior cross-sectional studies may have overestimated racial differences in disability due to selection bias. For example, our prior NHATS analysis was limited to community-dwelling stroke survivors. If white patients with stroke with severe disability are more likely to live in nursing homes than black patients with comparable levels of disability, it is possible that such selection bias may have led to overestimation of racial differences in disability in community-based samples. Similarly, it is possible that our current analysis understates the magnitude of the true racial differences in function because black patients with stroke were more likely to be discharged to LTCHs, where it is likely that stroke survivors have severe disability and are less likely to be discharged home, where disability is least. So, while its difficult to make clear inferences given differences in the measures and selection strategies, taken at face value, our findings suggest that while disability differences emerge early after stroke, and these difference may be amplified over subsequent years.

This study has important limitations. Clinical features during the initial stroke hospitalization (i.e., stroke severity) are not measured in administrative claims data. While this limits inferences at the individual level, it is unlikely to influence conclusions about racial differences as stroke severity has consistently been shown to differ minimally by race.28 The other key limitation is that while the FIM instrument has been validated against gold standards, the crosswalked Medicare functional assessments have not been validated across all 3 postacute care settings and have not been previously validated against independent measures of functioning. While they have reasonable face validity, and measures have been shown to strongly correlate with each other, it is possible that measurement error may lead to misestimation of racial differences, most likely by biasing our findings to the null. In addition, as these data are limited to the Medicare stroke population, whether racial differences in disability and mortality hold in younger adults is uncertain. Similarly, no measures of postdischarge physical functioning are available in the subset of patients discharged home. If racial differences in function exist in this population, it may obscure our inferences about overall racial differences. However, this is relatively unlikely to be a major source of bias as there are no major racial differences in the proportion of patients discharged home.18 Finally, regional characteristics were not accounted for in our model.25 The key strengths of this study include its large, representative sample and capture of functional data across multiple rehabilitation settings.

Glossary

- ADL

activities of daily living

- FIM

Functional Independence Measure

- HHA

home health aide

- ICD-9

International Classification of Diseases–9

- IRF

inpatient rehabilitation facility

- LTCH

long-term care hospital

- MDS

Minimum Data Set

- NHATS

National Health Aging and Trends Study

- OASIS

outcome and assessment information set

- Pseudo-FIM

Pseudo-Functional Independence Measure

- SNF

skilled nursing facility

Appendix. Authors

Footnotes

Editorial, page 773

CME Course: NPub.org/cmelist

Study funding

This work was supported by NIMHD grant R01 MD008879. J. Burke is funded by NIH grants NINDS K08 NS082597 and NIMHD R01 MD008879. L. Skolarus is funded by NIMHD R01 MD008879, U01 MD010579, and R01 MD011516.

Disclosure

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Howard VJ, Kleindorfer DO, Judd SE, et al. Disparities in stroke incidence contributing to disparities in stroke mortality. Ann Neurol 2011;69:619–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kleindorfer DO, Khoury J, Moomaw CJ, et al. Stroke incidence is decreasing in whites but not in blacks: a population-based estimate of temporal trends in stroke incidence from the Greater Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky Stroke study. Stroke 2010;41:1326–1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burke JF, Freedman VA, Lisabeth LD, Brown DL, Haggins A, Skolarus LE. Racial differences in disability after stroke: results from a nationwide study. Neurology 2014;83:390–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burke JF, Skolarus LE, Freedman VA. Racial disparities in poststroke activity limitations are not due to differences in prestroke activity limitation. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2015;24:1636–1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Capistrant BD, Mejia NI, Liu SY, Wang Q, Glymour MM. The disability burden associated with stroke emerges before stroke onset and differentially affects blacks: results from the health and retirement study cohort. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2014;69:860–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kleindorfer D, Lindsell C, Alwell KA, et al. Patients living in impoverished areas have more severe ischemic strokes. Stroke 2012;43:2055–2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qian F, Fonarow GC, Smith EE, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in outcomes in older patients with acute ischemic stroke. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2013;6:284–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.White H, Boden-Albala B, Wang C, et al. Ischemic stroke subtype incidence among whites, blacks, and Hispanics: the Northern Manhattan Study. Circulation 2005;111:1327–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwamm LH, Reeves MJ, Pan W, et al. Race/ethnicity, quality of care, and outcomes in ischemic stroke. Circ Am Heart Assoc 2010;121:1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kissela B, Lindsell CJ, Kleindorfer D, et al. Clinical prediction of functional outcome after ischemic stroke: the surprising importance of periventricular white matter disease and race. Stroke 2009;40:530–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tirschwell DL, Longstreth WT. Validating administrative data in stroke research. Stroke 2002;33:2465–2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldstein LB. Accuracy of ICD-9-CM coding for the identification of patients with acute ischemic stroke: effect of modifier codes. Stroke 1998;29:1602–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lakshminarayan K, Larson JC, Virnig B, et al. Comparison of Medicare claims versus physician adjudication for identifying stroke outcomes in the women's health initiative. Stroke 2014;45:815–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones SA, Gottesman RF, Shahar E, Wruck L, Rosamond WD. Validity of hospital discharge diagnosis codes for stroke: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Stroke 2014;45:3219–3225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ottenbacher KJ, Hsu Y, Granger CV, Fiedler RC. The reliability of the Functional Independence Measure: a quantitative review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1996;77:1226–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Linacre JM, Heinemann AW, Wright BD, Granger CV, Hamilton BB. The structure and stability of the Functional Independence Measure. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1994;75:127–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams BC, Li Y, Fries BE, Warren RL. Predicting patient scores between the Functional Independence Measure and the Minimum Data Set: development and performance of a FIM-MDS “crosswalk.” Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1997;78:48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skolarus LE, Feng C, Burke JF. No racial difference in rehabilitation therapy across all post-acute care settings in the year following a stroke. Stroke 2017;48:3329–3335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barnato AE, Farrell MH, Chang CCH, Lave JR, Roberts MS, Angus DC. Development and validation of hospital “end-of-life” treatment intensity measures. Med Care 2009;47:1098–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Badhiwala JH, Nassiri F, Alhazzani W, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2015;314:1832–1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barnato AE, Anthony DL, Skinner J, Gallagher PM, Fisher ES. Racial and ethnic differences in preferences for end-of-life treatment. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24:695–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meisel K, Arnold RM, Stijacic Cenzer I, Boscardin J, Smith AK. Survival, functional status, and eating ability after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement for acute stroke. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017;65:1848–1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barnato AE, Herndon MB, Anthony DL, et al. Are regional variations in end-of-life care intensity explained by patient preferences? A study of the US Medicare population. Med Care 2007;45:386–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anthony DL, Herndon MB, Gallagher PM, et al. How much do patients' preferences contribute to resource use? Health Aff 2009;28:864–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Faigle R, Ziai WC, Urrutia VC, Cooper LA, Gottesman RF. Racial differences in palliative care use after stroke in majority-white, minority-serving, and racially integrated U.S. hospitals. Crit Care Med 2017;45:2046–2054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Differences in disability among black and white stroke survivors: United States, 2000–2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2005;54:3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roth DL, Haley WE, Clay OJ, et al. Race and gender differences in 1-year outcomes for community-dwelling stroke survivors with family caregivers. Stroke 2011;42:626–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hartmann A, Rundek T, Mast H, Paik M, Boden B. Mortality and causes of death after first ischemic stroke: the Northern Manhattan Stroke Study. Neurology 2001;57:2000–2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying these analyses cannot be shared. They were made available to investigators and stored on secured servers at the University of Michigan based on a data use agreement with Medicare that precludes data sharing.