Abstract

Background

In adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS), the continuous search for effective prognostication of significant curve progression at the initial clinical consultation to inform decision for timely treatment and to avoid unnecessary overtreatment remains a big challenge as evidence of the multifactorial etiopathogenic nature is increasingly reported. This study aimed to formulate a composite model composed of clinical parameters and circulating markers in the prediction of curve progression.

Method

This is a two-phase study consisting of an exploration cohort (120 AIS, mean Cobb angle of 25°± 8.5 at their first clinical visit) and a validation cohort (51 AIS, mean Cobb angle of 23° ± 5.0° at the first visit). Patients with AIS were followed-up for a minimum of six years to formulate a composite model for prediction. At the first visit, clinical parameters were collected from routine clinical practice, and circulating markers were assayed from blood.

Finding

We constructed the composite predictive model for curve progression to severe Cobb angle > 40° with a high HR of 27.9 (95% CI of 6.55 to 119.16). The area under curve of the composite model is higher than that of individual parameters used in current clinical practice. The model was validated by an independent cohort and achieved a sensitivity of 72.7% and a specificity of 90%.

Interpretation

This is the first study proposing and validating a prognostic composite model consisting of clinical and circulating parameters which could quantitatively evaluate the probability of curve progression to a severe curvature in AIS at the initial consultation. Further validation in clinic will facilitate application of composite model in assisting objective clinical decision.

Keywords: Scoliosis, Adolescent, Clinical study, Hong Kong

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Despite there is higher concordance rate in monozygotic twins (73%) than dizygotic twins (36%), the considerable discordance in the pattern, level and severity of curve deformity that exists even in monozygotic twins suggests the presence of other non-genetic factors that could interfere with the clinical presentation in AIS. Clinical parameters or novel prognostic factors (such as miRNAs, DNA methylation value and genetic score) have been proposed to predict curve progression in different studies. No study comparing these independent factors or combining them into a composite model.

Added value of this study

The multifactorial nature of AIS complicates the development of specific and sensitive predictive model. This is due to the involvement of complex signaling pathways. Here, we proposed a composite model consisting of clinical and circulating parameters for predicting curve progression beyond 40° at skeletal maturity. Two cohorts with a minimum of 6 years longitudinal follow-up were employed for establishing and validating the composite model. Our findings demonstrated that it is feasible to predict curve progression to severe curvature at first clinical visit.

Implications of all the available evidence

Various independent factors have been proposed to predict curve progression in AIS, however their predictive value remains to be validated with larger cohort and in different ethnic groups. Our findings suggest that it is worthwhile to formulate some of these factors into a composite model to enhance the predictive sensitivity and specificity for this multifactorial disease. Improved prediction shed light on improving timely clinical decisions for early bracing treatment for the potential progressive group and to avoid overtreatment of the likely non-progressive AIS.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

1. Introduction

Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis (AIS) is a rotational spinal deformity occurring predominantly in 10–13 years old girls with a global prevalence of 1–4% [1]. Severe spinal deformity in AIS is associated with functional morbidities, cardiopulmonary compromise, early spinal degenerative changes and psychosocial disturbance [2]. Owing to unclear aetiology and pathogenesis, bracing, scoliosis-specific exercises [3] and instrumental surgical correction are the only available evidence-based treatment regimes targeting the structural deformity rather than the cause. Cobb angles greater than 40–45° have been considered as threshold for surgical correction [1,4]; and bracing treatment is recommended to patients with AIS with Cobb angles of 20–40° [1]. Currently, younger chronological/skeletal age of patient at presentation, greater initial spine curvature, later onset of menarche are clinical features associated with higher chance of curve progression [5]. Previous systemic review on predictors with pooled prognostic characteristics for curvature progression in AIS indicated limited clinical application and low level of evidence [6]. Therefore, a search for a reliable predictive model for curve progression to severe spinal deformity (Cobb angle of 40°) that would require timely treatment has been an outstanding clinical challenge in the management of AIS.

Since the first genome-wide association studies (GWAS) conducted by Sharma et al. [7], hundreds of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) have been reported in various cohorts comparing AIS and control populations but the majority of them are not replicable in different ethnic groups, and their biological functions in AIS remains unclear [1]. A genetic based prognostic test consisting of a 53-gene panel called ScolioScore has been proposed to identify patients with AIS at low risk of curve progression, but its predictive value is limited [8]. Follow-up replication studies conducted by Tang [9] and Ogura [10] were not able to find the association between the 53 SNPs and curve progression or curve occurrence in French-Canadian and Japanese population, respectively. There is increasing evidence showing heterogeneous curve magnitudes and apical levels in twin studies [11], [12], [13], suggesting the determinant roles of non-genetic factors in curve progression. These observations led to the development of a conceptual complex disease model: a genetic-dependent initiation phase and a progression phase mediated by undefined environmental factors [14].

Emerging evidence shows that abnormal bone quality is closely associated with the progression of AIS. We reported low bone mass, defined as a Z-score of the femoral neck areal bone mineral density less than −1 with reference to an age, gender and ethnic matched population, in over 30% of those with AIS [15]. Later, low bone mass was found to be an independent prognostic factor for predicting curve progression in AIS [16,17]. The root cause of low bone mass in AIS is unclear. Bone histomorphometry studies on bone biopsies from surgical cases indicated abnormally higher bone turnover in AIS [18,19]. It is speculated that an abnormality of bone metabolism in AIS possibly results in the spine being more vulnerable to deformity. Our recent study firstly revealed a causative relationship between aberrant microRNA-145–5p (miR-145) expression and abnormal osteocyte structure and function in AIS [20]. The miR-145 expression inhibited osteocyte dendritic formation and function by disturbing active β-catenin expression and its transcriptional activity [18]. We also reported negative correlation between plasma miR-145 and serum levels of bone metabolic markers [18]. MicroRNA (miRNA) is a class of endogenous short noncoding RNA that regulates diverse gene expression mainly at the post-transcriptional level [21]. Despite the source of circulating miRNAs being generally diverse, their wide spectrum of biological activity and stable measurability in plasma make them potential biomarkers that can mirror systemic changes occurring in multifactorial disorders [22]. Previous attempts at identifying circulating miRNA signatures that could reflect the status of multifactorial bone diseases and predict accurate fracture risk were reported [23]. These evidences from other pathological conditions suggest that the circulating miRNA profile represents a potential biomarker to reflect the abnormal signalling pathways in AIS.

Considering the involvement of multifactorial pathomechanisms (such as central nervous system dysfunction, abnormal skeletal growth and bone qualities, mechanical disturbance of spinal loading, and aberrant metabolic pathways and endophenotypes), it is more logical to develop a composite model with clinically applicable and interpretable quantitative factors for predicting the probability of progression to severe levels [24]. We hypothesize that a composite model consisting of clinical parameters and serum bone metabolic makers is more appropriate for predicting disease severity in AIS which is characterised as multifactorial pathomechanisms.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patient recruitment

As referred by local population based School Scoliosis Screening Service, participants with AIS with maximal Cobb angle ≥ 20° were referred to our scoliosis special clinic (one of the two referral centres in Hong Kong) [1]. A total of 171 patients with AIS were recruited.

Anthropometric parameters including body height, body weight and arm span were measured with standard protocols [16,17]. The diagnosis of AIS was confirmed clinically by two senior orthopaedic surgeons and radiologically with standing full-spine posteroanterior (PA) X-ray. The Cobb angle of the major curve was measured and recorded within a month before or after blood taking. Patients were asked to report the date of first menarche to the nearest to month. The Risser Sign, indicating skeletal maturity was evaluated from the whole spine PA X-ray film. Risser sign is determined according to the following scheme: Stage 0: no ossification center at the level of the iliac crest apophysis. Stage 1: apophysis under 25% of the iliac crest. Stage 2: apophysis over 25–50% of the iliac crest. Stage 3: apophysis over 50–75% of the iliac crest. Stage 4: apophysis over >75% of the iliac crest. Stage 5: complete ossification and fusion of the iliac crest apophysis [25]. Blood taking and anthropometric measurement were conducted at the first clinical visit. Radiological Cobb angle was assessed at the first visit and at every six months interval.

All the patients were regularly followed, observed and/or treated with bracing or surgical correction according to standard clinical practice [1]. Initial Cobb angle of recruited participants was smaller than or equal to 34 o. Patients with Cobb angle >40° in either one or more follow-up(s) were defined as the severe group, and those with Cobb angle ≤40° in entire 6 years follow-ups were defined as the non-severe group. Participants with congenital deformities, neuromuscular diseases, autoimmune disorders, endocrine disturbances or medical conditions that affecting bone metabolism were excluded.

An exploratory cohort included participants (N = 120) who were recruited between April, 2010 and September, 2012, and had completed six years of follow-up before June 2018. The validation cohort included participants (N = 51) who were recruited between April, 2010 and May, 2012, and had completed their six years of follow-up after June 2018. Ethical approval, in accordance with Declaration of Helsinki, was obtained from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the University and Hospital (CREC No. 2016.657 & CREC 2009.491). Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants and their legal guardians before the examinations and measurements were conducted.

2.2. Measurement of circulating markers

Peripheral venous blood samples (2 mL) were collected from participants’ arm at their first visit in our scoliosis special clinic [20]. Blood was centrifuged at 4 °C, 3,000 x g, 10 min. Serum and plasma was aliquoted to minimize freeze-thaw cycle and stored at −80 °C for further analysis. Serum samples were sent to Chan & Hou Medical Laboratories Ltd (Hong Kong) for assaying the levels of CTX and P1NP with the Elecsys platform (Roche) [26]. Isolation of circulating miRNA from plasma was performed with miRNeasy plasma advanced kit (217204, Qiagen, Venlo, The Netherlands) according to manufacturer's protocol [27]. A cDNA library was constructed and target miRNA expression level were measured with Taqman@ advanced miRNA assay (Life Technologies, California, USA) [28]. The hsa-miR-16 was chosen as an internal reference after evaluating its stability with BestKeeper (http://www.gene-quantification.de/bestkeeper.html/).

2.3. Statistical analysis

The normality of data was tested by Shapiro-Wilk test. Normal data was presented as mean ± SD and otherwise presented as median (minimum, maximum). To compare the parameters between those with severe AIS and with non-severe AIS, an independent sample t test was used for the normal data, the Mann-Whitney U test was used for skewed data, and Chi-square test was used for categorical variable. Partial correlations (Pearson test) with adjustment of age were used to determine the correlation (rpartial) between curve severity and clinical and circulating parameters.

The variables, which were significantly correlated with the latest maximum Cobb angle and able to discriminate severe AIS from non-severe AIS in different tests mentioned above (p<0.05), were selected into the multivariate logistic regression (ENTER). Based on the logistic regression analysis, an equation of risk score to predict Cobb angle > 40° was developed. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to illustrate the predictive ability for severe curve diagnosis of our composite model, and of the individual parameters recruited into the model. The area under curve (AUC) was used to compare whether the model or individual parameters could distinguish patients with severe from AIS patients without progression to severe curvature. Menarche status was dichotomized as follows: 1 = onset of menarche is earlier than the first clinical visit and 0 = premenarche at first clinical visit. To identify the optimal cut-off, we assessed sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood, negative likelihood and accuracy of different cut-offs in logistic regression equation. We used a cut-off of 0.2, i.e., patients with calculated score greater than or equal to 0.2 were at high risk of progression to 40° or above. This cut-off was selected by consulting orthopedic surgeons after 25 weighing potential harm to miss a true positive case and to prescribe over treatment.

The outcome variable was the time from presentation to development of a curvature greater than 40°. The time was considered as censored at the last clinical visit whose curvature has not reached 40°. Factor considered in the analysis is the logistic score calculated with initial Cobb angle, Risser sign, menarche status, body weight, plasma miR-145 level and serum P1NP level at first visit. The factor is dichotomised as follows: 1 as logistic score ≥0.2 and 0 as logistic score <0.2. The Hazard Ratio was estimated by fitting Cox proportional-hazards model. P-value < 0.05 (two tailed) indicated statistical significance.

Data collection and analyses were performed by two independent blinded investigators. The investigator who handled the blood sample and assayed serological markers was blinded to information about the participants. A separate investigator was responsible for data analysis and equation construction. Clinicians who completed regular clinic follow-up, and measured the curve severity and clinical parameters were blinded to the blood test result. Analyses were performed using SPSS (version 25; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

3. Result

3.1. Correlation analysis between selected factors and curve severity

Patients with AIS (N = 120) were recruited for a longitudinal study with a mean follow-up of 6.33 ± 0.45 years until reaching skeletal maturity. Anthropometric measurements, skeletal maturity status, serum levels of bone turnover markers (CTX and P1NP), and plasma level of miR-145 at their first clinical visit were measured before the start of any treatment for spinal deformity (Table 1). To identify potential factors associated with the severity of disease, patients with AIS were first divided into severe or non-severe groups according to their Cobb angle of > 40° or ≤ 40° during follow-up, respectively. A cut-off of 40° allowed sufficient sample size per group to indicate the likelihood of requiring aggressive and early treatment. When compared with patients without progression to severe curvature, 27 patients with AIS who progressed to a severe curvature were characterized by a higher initial Cobb angle (p < 0.001, by Mann-Whitney U test), lower body weight (p = 0.009, by Independent sample t-test), delayed menarche (p = 0.008, by Chi-squared test), and lower Risser sign (p = 0.002, by Mann-Whitney U test) at their first visit despite presenting similar chronological age (shown in Table 1). For the circulating markers, patients with AIS progressed to a severe Cobb angle (> 40°) had significantly lower level of plasma miR-145 (p = 0.018, by Independent sample t-test) and higher serum level of P1NP (p = 0.033, by Independent sample t-test) at their first visit (shown in Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of anthropometry, maturity, plasma miR-145 level and serum bone turnover markers at first visit between severe and non-severe AIS (N = 120).

| Cobb angle > 40° (N = 27) | Cobb angle ≤ 40° (N = 93) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) b | 12.48 (12.06, 13.46) | 13.08 (12.12, 13.67) | 0.291 |

| Initial maximum Cobb angle(o) b | 30 (28, 32) | 21 (18, 26) | <0.001 |

| Latest maximum Cobb angle(o) b | 42 (39, 49) | 27 (22, 31) | <0.001 |

| Anthropometry | |||

| Body weight (kg) a | 38.3 ± 5.0 | 41.7 ± 6.1 | 0.009 |

| Body height (cm) a | 152.0 ± 7.2 | 154.0 ± 6.4 | 0.166 |

| Arm span (cm) a | 152.5 ± 7.5 | 153.2 ± 7.4 | 0.660 |

| Maturity | |||

| Year since menarche (years) b | 0.69 (0.23, 1.20) | 0.84 (0.39, 1.19) | 0.490 |

| Menarche before first visit c,d | 12 (44.4%) | 67 (72.0%) | 0.008 |

| Risser sign b,e | 0.002 | ||

| 0 (17) | 0 (26) | ||

| 1 (1) | 1 (14) | ||

| 2 (5) | 2 (15) | ||

| 3 (3) | 3 (16) | ||

| 4 (1) | 4 (22) | ||

| 5 (0) | 5 (0) | ||

| Plasma micro-RNA level | |||

| ln (miR-145) a,f | −5.7 ± 1.23 | −4.95 ± 1.84 | 0.018 |

| Serum bone turnover markers2 | |||

| ln (CTx) a,g | 7.02 ± 0.56 | 6.85 ± 0.55 | 0.179 |

| ln (P1NP) a,g | 6.47 ± 0.52 | 6.19 ± 0.59 | 0.033 |

Latest maximum Cobb angle is measured at latest clinical visit after completing follow-up. Other parameters are measured at patients’ first clinical visit.

Normally distributed data is presented as Mean ± SD and Independent sample t-test was used.

Data are not normally distributed and presented as median (lower quartile, upper quartile) and Mann-Whitney U test is used.

Chi-squared test is used.

Menarche status, 1 = onset of menarche is earlier than the first clinical visit and 0 = premenarche at first clinical visit.

Risser sign is presented as frequency of each level of Risser score.

The value for “the plasma level of miR-145″ is the fold change relative to the level of the housekeeping reference miR-16. A log of the plasma level of miR-145 with the base e is calculated.

The level of CTX P1NP in the serum is represented as µg/L. A log of CTX/P1NP concentration with the base e is calculated and used.

Partial correlations between clinical parameters or the serological markers and the maximum Cobb angle at the latest visit with adjustment of age were reported in Table 2. Years since Menarche (rpartial = −0.195, p = 0.033), plasma miR-145 (rpartial = −0.288, p = 0.002) and serum P1NP level (rpartial = 0.219, p = 0.019) were significantly correlated with the latest maximum Cobb angle (Table 2). Associations between Body weight and Risser Sign with the latest Maximum Cobb angle reached marginal significance. Result of the partial correlation analysis showed that the factors with significant difference in Table 1 were associated with the latest Cobb angle. Therefore, we included Initial Max Cobb, Menarche Status, Body Weight, Risser Sign and level of miR-145 and P1NP in the logistic regression model.

Table 2.

Partial correlations between curve severity at latest visit and clinical or serological parameters at first clinical visit with adjustment of age (N = 120).

| Latest Max Cobb |

||

|---|---|---|

| Correlation | p-value | |

| Initial Max Cobb (°) | 0.697 | <0.001 |

| Body weight (kg) | −0.161 | 0.080 |

| Body height (cm) | −0.080 | 0.384 |

| Arm span (cm) | 0.034 | 0.711 |

| Years since menarche (years) | −0.195 | 0.033 |

| Risser sign | −0.180 | 0.052 |

| ln (miR-145)a | −0.288 | 0.002 |

| ln (CTx)b | 0.155 | 0.099 |

| ln (P1NP)b | 0.219 | 0.019 |

The value for “the plasma level of miR-145″ is the fold change relative to the level of the housekeeping reference miR-16. A log of the plasma level of miR-145 with the base e is calculated.

The level of CTX P1NP in the serum is represented as µg/L. A log of CTX/P1NP concentration with the base e is calculated and used.

3.2. Establishing a composite model to predict curve progression

We developed a logistic regression equation to calculate risk score for progression to over 40° with the selected risk factors (Nagelkerke R2 of 0.575).

Risk score of Progression to over 40°=(1 + e8.437 - 0.403 × Initial Max Cobb+0.413 × Menarche+0.150 × Weight+0.283 × Risser Sign+0.070 × ln (miR-145) - 0.427 × ln (P1NP))−1

The sensitivity, specificity, predictive value, likelihood ratios and calculated accuracy at different cut-off levels are summarized in Table 3. A cut-off level of 0.2 had a sensitivity of 91.7% and a relatively high specificity of 79.8%, and was adopted in subsequent evaluation. Risk score > 0.2 indicated a patient at higher progression risk into severe curvature.

Table 3.

Comparison of different cut-offs in logistic regression model. (N = 120).

| Cut-off | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive predictive value | Negative predictive value | Positive likelihood ratio | Negative likelihood ratio | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 95.8 | 69.7 | 46.0 | 98.4 | 3.16 | 0.06 | 75.2 |

| 0.2 | 91.7 | 79.8 | 55.0 | 97.3 | 4.54 | 0.10 | 82.3 |

| 0.3 | 79.2 | 86.5 | 61.3 | 93.9 | 5.87 | 0.24 | 85.0 |

| 0.4 | 75.0 | 89.9 | 66.7 | 93.0 | 7.43 | 0.28 | 86.7 |

| 0.5 | 66.7 | 95.5 | 80.0 | 91.4 | 14.82 | 0.35 | 89.4 |

| 0.6 | 50.0 | 96.6 | 80.0 | 87.8 | 14.71 | 0.52 | 86.7 |

| 0.7 | 33.3 | 97.8 | 80.0 | 84.5 | 15.14 | 0.68 | 84.1 |

| 0.8 | 20.8 | 97.8 | 71.4 | 82.1 | 9.45 | 0.81 | 81.4 |

| 0.9 | 12.5 | 98.9 | 75.0 | 80.7 | 11.36 | 0.88 | 80.5 |

3.3. Assessment of accuracy of the composite model

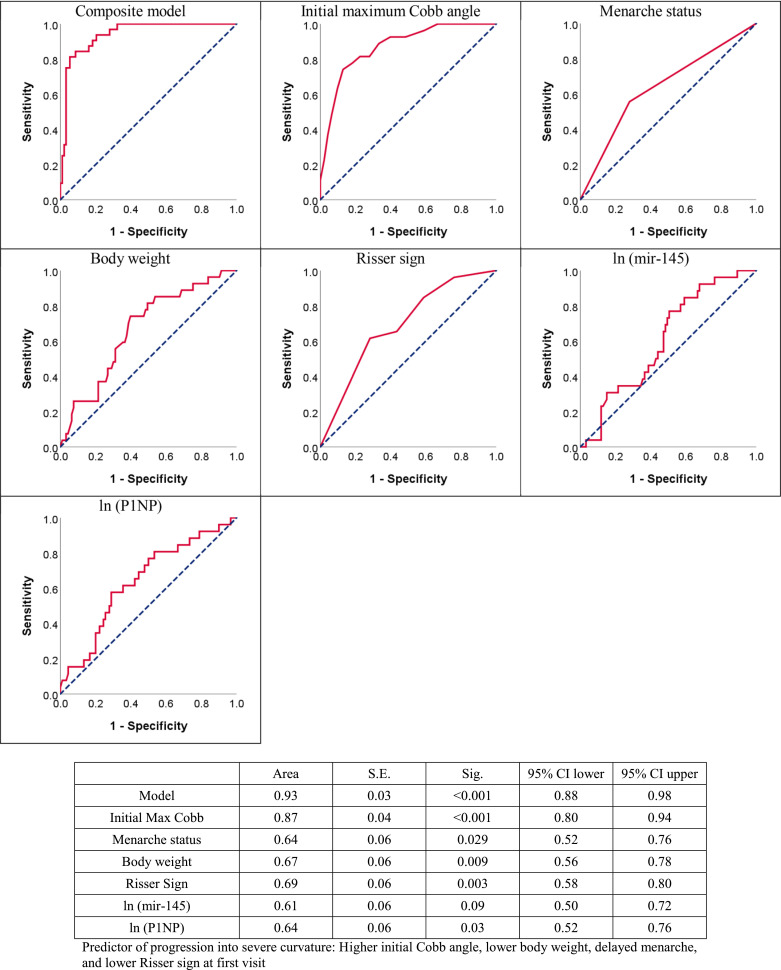

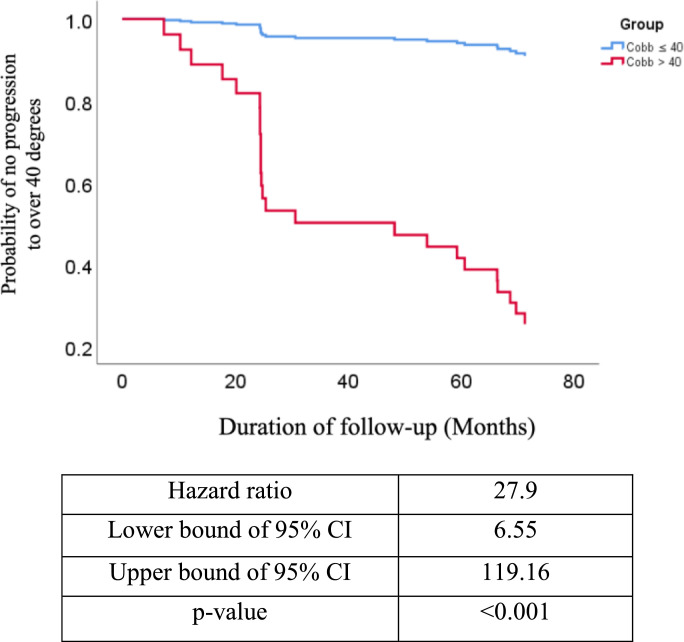

The ROC curve analyzed accuracy of clinical parameters with AUC. Fig. 1 showed menarche status with AUC of 0.64 (95% CI=0.52–0.76), body weight with AUC of 0.67 (95% CI=0.56–0.78) and Risser sign with AUC of 0.69 (95% CI=0.58–0.80). The AUC of serological markers was also calculated. Fig. 1 demonstrated plasma miR-145 level with AUC of 0.61 (95% CI=0.50–0.72) and serum P1NP level with AUC of 0.64 (95% CI=0.52–0.76). Compared to other single factor, initial max Cobb angle had higher value of AUC of 0.87 (95% CI=0.80–0.94). Composite model had highest AUC value of 0.93 (95% CI=0.88–0.98) (Fig. 1), indicating the increased accuracy of the composite model when compared with other individual factors. Data on progression-free survival were available for 120 AIS participants with mean follow-up of 6.33 ± 0.45 years, which showed that composite model offered significant prognositication (p < 0.001, by cox proportional hazard model) with Hazard Ratio of 27.9 (95% CI=6.55–119.16) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of predictive power of composite model and single factors to evaluate risk of severe spinal deformity (Cobb angle > 40°) after reaching skeletal maturity (N = 120): a Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves; b. Area under curve (AUC) values.

Fig. 2.

Assessment of predictive accuracy of composite model by Cox proportional-hazards model. (N = 120).

3.4. Validating the accuracy of predictive model in an independent cohort

With promising results from the previous investigation, the suitability and accuracy of the composite model was further assessed in a separate cohort with same recruitment criteria described in methodology (Table 4). Clinical features and levels of serological markers (Table 4) of 51 patients with AIS had no significant difference to that of previous cohort (Table 1). Risk score of each participant was calculated with parameters collected at first visit. Table 5 showed that 8 patients with risk score > 0.2 had curve progression > 40°, while 36 out of 39 patients with calculated risk score < 0.2 were not progressed into 40°. Validation analysis showed that the logistic regression model with cut-off of 0.2 had an accuracy of 86.3%, a sensitivity of 72.7% and a specificity of 90%.

Table 4.

Baseline information of validation cohort: anthropometry, maturity, plasma miR-145 level and serum bone turnover markers at first clinical visit (N = 51).

| Mean ± SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 51 | |

| Age (years) | 12.81 ± 0.97 | 10.53 – 14.39 |

| Initial maximum Cobb angle (o) | 23 ± 5 | 14 – 34 |

| Latest maximum Cobb angle(o) | 30 ± 11 | 14 – 59 |

| Anthropometry | ||

| Body weight (kg) | 41.2 ± 5.9 | 29.4 – 52.4 |

| Body height (cm) | 154.2 ± 7.1 | 130.0 – 167.6 |

| Arm span (cm) | 153.3 ± 8.2 | 127.5 – 169.2 |

| Maturity | ||

| Year since menarche (years) | 1.35 ± 0.86 | 0.07 – 3.10 |

| Menarche before first visitc | 33 (65%) | |

| Risser sign d | 0 (18) | 0 – 4 |

| 1 (4) | ||

| 2 (4) | ||

| 3 (7) | ||

| 4 (18) | ||

| Plasma micro-RNA level | −5.96 ± 1.41 | |

| ln (miR-145) a | −11.79 – −2.66 | |

| Serum bone turnover markers | 6.80 ± 0.50 | |

| ln (CTx) b | 6.13 ± 0.68 | 5.61 – 7.82 |

| ln (P1NP) b | 3.81 – 7.12 |

The value for “the plasma level of miR-145″ is the fold change relative to the level of the housekeeping reference miR-16. A log of the plasma level of miR-145 with the base e is calculated.

The level of CTX P1NP in the serum is represented as µg/L. A log of CTX/P1NP concentration with the base e is calculated and used.

Menarche status, 1 = onset of menarche is earlier than the first clinical visit and 0 = premenarche at first clinical visit.

Risser sign is presented as frequency of each level of Risser score.

Table 5.

Validation of accuracy of predictive model in an independent cohort with cut-off of 0.2. Result of risk score from composite model (N = 51).

| Observed |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Grouping | >40 | ≤40 | |

| Predicted | >40 | 8 | 4 |

| ≤40 | 3 | 36 | |

4. Discussion

Our study established a composite model of clinical parameters and circulating markers and proved its validity to predict whether the patient with AIS would progress into curvature over 40° after reaching skeletal maturity at early clinical visit. In our cohort, the percentage of progressing into severe curve is 22.5% (=27/120). Our study proved the possibility of applying a composite model to predict severity of curvature of AIS at early clinical visit. Table 3 showed performance of different cut-offs. Cut-off of 0.2 was chosen in following analysis for demonstration in terms of sensitivity of 91.7%. High sensitivity of predictive model avoids the missing of true severe cases. However, the specificity of 79.8% indicates probability of 20.2% to prescribe false positive cases with overtreatment. Theoretically, a satisfactory predictive model needs sensitivity >95% and specificity > 95%. With the current proof of concept, a refined model will be subjected to larger cohort and involvement of more potential clinical and/or serological markers [4]. We calculated basal hazard ratio (of 27.9) to indicate that the patient with risk score ≥ 0.2 at first visit had 27.9 times higher risk to progress to Cobb angle of above 40° when compared with the patient with risk score < 0.2.

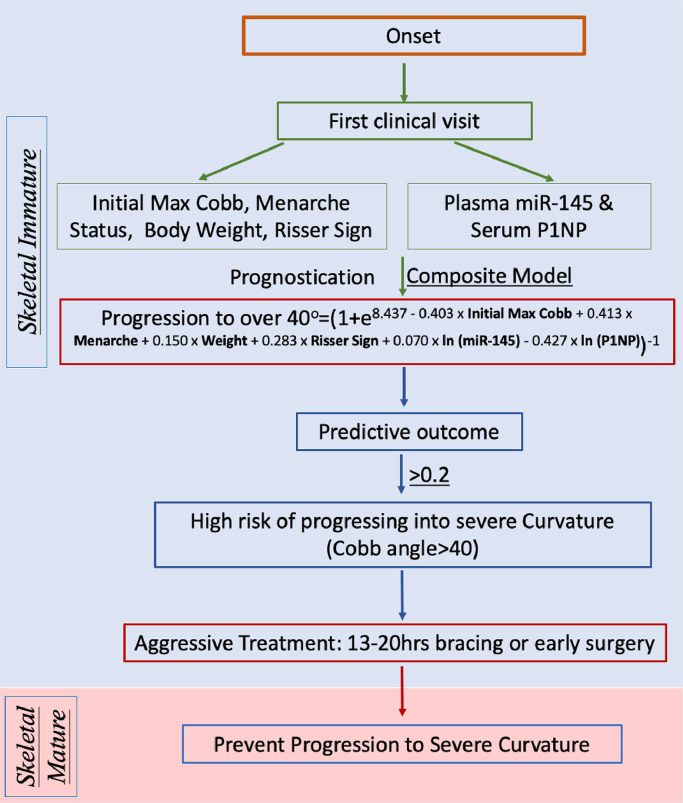

Fig. 3 proposed a schematic flow chart of how the composite model could be implemented and beneficial to clinical practice. Information is collected from routine clinical practice at their first clinical visit, including initial maximum Cobb angle, menarche status, weight, and Risser sign. Circulating markers at baseline will be assayed for serum P1NP and plasma miR-145 levels accordingly. The collected information can be used to calculate the risk score with the composite model. Based on the experience in our special scoliosis centre in Hong Kong which belongs to public hospital system, additionally 10 min is required for blood taking. For the assay, the whole procedure for miRNA measurement can be completed in 4 h; and 1 day for P1NP measurement as it is done by third part in our study. Also, the cost for miRNA-145 and P1NP measurements is USD 60 in our current practice. We believed that the time and cost can be reduced if the whole procedure can be streamlined further. It is expected to have the predictive result presented to patients and allow clinician making decision of treatment on time without extra burden of economy and time. Using a cut-off level of 0.2, AIS would be at higher risk of progression into Cobb angle > 40° if risk score> or =0.2. Clinician are able to decide necessary management such as long bracing wearing (e.g. full time bracing wearing) per day, early surgery intervention, or aggressive treatment to patient with Cobb angle less than 25° instead of traditional observation. However, current study did not provide information on effect of treatment to outcome of disease severity. To support the application of composite model in clinical practice, two research question need to be further addressed: 1) What is the best cut-off of the composite model? 2) How is the treatment effect of aggressive treatment prevent patient at predictive high risk? With further validation in larger cohort, the risk score is expected to provide quantitative reference to clinician to make decision on disease management and to minimize unnecessary overtreatment to patient with AIS, with the primary good wish to provide them a better quality of life and less burden.

Fig. 3.

Schematic diagram.

To be noted, the uniqueness of proposed model is the first time to combine clinical parameters and circulating markers in predictive model for AIS. In current clinic practice, the prediction of curve progression of these patients is mainly empirical, based on initial Cobb angle, age and menarche status. Our findings suggested that maximum Cobb angle, menarche status, body weight and Risser sign measured at the first clinical visit were closely associated with disease severity of AIS. Therefore, in the composite model, chronological age was replaced with Risser sign and menarche status to better reflect skeletal age and maturity during curve progression [1]. Result of Fig. 1 indicated maximum Cobb angle, as a single risk factor, showed a promising accuracy compared to other single risk factors. Publication on genetic factors, circulating miRNA levels and DNA methylation level proved the concept of using circulating markers to predict disease progression of AIS [6,8]. The clinical application of these reported markers are limited by poor reproducibility, knowledge gap in mechanistic evidence, and unclear association to curve progression [6].

Previously clinical studies on the lower bone mass in AIS have laid the foundation for the possible link between curve progression and abnormal bone metabolism, as well as the selection of bone metabolism markers in the present study. In vitro studies have revealed abnormal cellular activities of primary osteoblasts in response to melatonin, leptin and estrogen in AIS [29], [30], [31]. Serum bone turnover markers, such as bone specific alkaline phosphatase (bALP) and soluble receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand (RANKL) are associated with curve severity [32,33], but none of them are validated predictive factor for curve progression [6]. miR-145 regulated osteocyte differentiation and activities has been reported in our previous study [20]. It is interesting to note that miR-145 could also modulate the proliferation and differentiation of muscle cells by inducing reprogramming of fibroblast into smooth muscle cell, and differentiation of neural crest stem cells into vascular smooth muscle during muscle development [34]. Incidentally, higher muscle activity with larger muscle mass, more type I muscle fibers, less fibrosis and fatty involution has been reported on the convex side of the apical vertebra in AIS [35,36]. It is speculated that imbalanced muscle activities between convex and concave side could be associated with spinal deformity of AIS given that muscle changes could be a reaction to the bio-mechanic demands of the convexity [1]. We speculate that the changing level of circulating miR-145 in AIS could be associated with phenotypic changes in bone and muscle in AIS and could serve as an important prognostic biomarker. Our findings indicate that serum P1NP and plasma miR-145 are closely associated with potential of curve progression and disease severity in AIS (Tables 1 and 2). The inclusion of these two circulating markers in the composite model is believed to reflect part of the complex pathological condition underlying abnormal bone metabolism in AIS.

About 80% of patients with AIS are prescribed with bracing or other treatment to prevent progression [37]. Bracing is the most recognized non-surgical treatment for skeletally immature patients with Cobb angle between 20° and 40°(1). The success rate of bracing is 70–75% subjected to initial brace correction quality, brace design, treatment compliance, adequate duration as well as clinical monitoring of X-ray at each clinical visit [37]. Given the physical and psychological burden, it is a critical clinical need to explore a method of distinguishing patients with AIS whose curvature are at high risk to reach 40° during pubertal growth period. The risk factors were selected because of significant difference between progression AIS with non-progression AIS, which suggested that selected candidates were potentially associated with severity of curvature in AIS.

There are several limitations of this study. 1) The sample size in the longitudinal cohort is not sufficient and solely based on Chinese AIS girls which may lead to overlooking or overwhelming the importance of the selected indicators. A blinded multi-centers and multi-ethnic groups or identical twin study are warranted to validate the flexibility and plausibility of the proposed model in assisting scoliosis treatment. 2) Due to the complex nature of AIS, the selected circulating markers may not be able to reflect the whole spectra of pathological condition in all patients with AIS. Future study is warranted to identify more promising predictive factors which could be included in this kind of composite model to increase the prediction power and to extend the potential application on predicting time of progression.

In summary, we herein propose a clinically accessible and interpretable predictive model for predicting the risk of disease severity which have the potential to facilitate the planning of appropriate timely treatment, and to avoid over-treatment during early clinical visit. Our longitudinal cohort with six years follow-up demonstrated the abnormal baseline plasma miR-145, serum P1NP level and certain clinical parameters in the progressive AIS group. We validated a logistic regression equation not only with power of prediction in curve severity, but also provided a new quantitative system to clinic with a clear cut-off reference. Subjected to further longitudinal multi-centre validation with the younger patients with AIS from different ethnic groups to prove an optimized cut-off with acceptable sensitivity and specificity, the composite model could help to inform timely clinical decisions on bracing treatment for the potential progressive group and to avoid over-treatment of the likely non-progressive AIS.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Dr Lam, Dr Sit, Dr Lee, Dr Qiu and Dr J. Cheng report grants from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong, during the conduct of the study. In addition, Dr Lam, Dr Zhang, Dr Cheuk, Dr Lee, Dr Qiu and Dr J. Cheng have a patent US provisional application, no. 62/923,748 pending. Dr J. Cheng also reports grants from Health and Medical Research Fund, grants from NSFC/RGC Joint Research Scheme sponsored by the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China and the National Natural Science Foundation of China, during the conduct of the study. Dr Moreau reports grants from Cotrel Foundation, during the conduct of the study. All other authors claim no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong S.A.R., China (Project 14163517 and 14135016 to JCY Cheng; 14120818 to WYW Lee; 14130216 to TP Lam, 14317716 and 14301618 to T Sit), the Health and Medical Research Fund (04152176 to JCY Cheng), the NSFC/RGC Joint Research Scheme sponsored by the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project Number. N_CUHK416/16 and 8161101087 to JCY Cheng and Y Qiu), and the research funding by Cotrel Foundation (to A Moreau). Funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation and writing of the report.

Author Contribution

WYW Lee, JCY Cheng, Y Qiu and A Moreau conceived the study and design; J. Zhang, KY Cheuk and Y Wang performed experiments and data analysis; J. Zhang, KY Cheuk and W. Y. W. Lee drafted the manuscript; T Sit provided statistical consultation; L Xu, Z Feng, TP Lam, ALH Hung, E Nepotchatykh assisted in samples collection and clinical data acquisition; and JCY Cheng, A Moreau, QY Qiu and WYW Lee performed critical revision of the manuscript. J Zhang and KY Cheuk contributed equally to this study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding: Refer to the acknowledgements.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.12.006.

Contributor Information

Jack C.Y. Cheng, Email: jackcheng@cuhk.edu.hk.

Yong Qiu, Email: scoliosis2002@sina.com.

Wayne Y.W. Lee, Email: waynelee@cuhk.edu.hk.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Cheng JC, Castelein RM, Chu WC, Danielsson AJ, Dobbs MB, Grivas TB. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2015;1:15030. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinstein SL. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: prevalence and natural history. Instr Course Lect. 1989;38:115–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Day JM, Fletcher J, Coghlan M, Ravine T. Review of scoliosis-specific exercise methods used to correct adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Arch Physiother. 2019;9:8. doi: 10.1186/s40945-019-0060-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meng Y, Lin T, Liang S, Gao R, Jiang H, Shao W. Value of DNA methylation in predicting curve progression in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. EBioMedicine. 2018;36:489–496. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soucacos PN, Zacharis K, Soultanis K, Gelalis J, Xenakis T, Beris AE. Risk factors for idiopathic scoliosis: review of a 6-year prospective study. Orthopedics. 2000;23(8):833–838. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20000801-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noshchenko A, Hoffecker L, Lindley EM, Burger EL, Cain CM, Patel VV. Predictors of spine deformity progression in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a systematic review with meta-analysis. World J Orthop. 2015;6(7):537–558. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v6.i7.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma S, Gao X, Londono D, Devroy SE, Mauldin KN, Frankel JT. Genome-wide association studies of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis suggest candidate susceptibility genes. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20(7):1456–1466. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roye BD, Wright ML, Williams BA, Matsumoto H, Corona J, Hyman JE. Does ScoliScore provide more information than traditional clinical estimates of curve progression? Spine. 2012;37(25):2099–2103. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31825eb605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang QL, Julien C, Eveleigh R, Bourque G, Franco A, Labelle H. A replication study for association of 53 single nucleotide polymorphisms in ScoliScore test with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in French-Canadian population. Spine. 2015;40(8):537–543. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogura Y, Takahashi Y, Kou I, Nakajima M, Kono K, Kawakami N. A replication study for association of 53 single nucleotide polymorphisms in a scoliosis prognostic test with progression of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in Japanese. Spine. 2013;38(16):1375–1379. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182947d21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kesling KL, Reinker KA. Scoliosis in twins. A meta-analysis of the literature and report of six cases. Spine. 1997;22(17):2009–2014. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199709010-00014. discussion 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smyrnis T, Antoniou D, Valavanis J, Zachariou C. Idiopathic scoliosis: characteristics and epidemiology. Orthopedics. 1987;10(6):921–926. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19870601-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Rhijn LW, Jansen EJ, Plasmans CM, Veraart BE. Curve characteristics in monozygotic twins with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: 3 new twin pairs and a review of the literature. Acta Orthop Scand. 2001;72(6):621–625. doi: 10.1080/000164701317269058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng JC, Tang NL, Yeung HY, Miller N. Genetic association of complex traits: using idiopathic scoliosis as an example. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;462:38–44. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e3180d09dcc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng JC, Hung VW, Lee WT, Yeung HY, Lam TP, Ng BK. Persistent osteopenia in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis–longitudinal monitoring of bone mineral density until skeletal maturity. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2006;123:47–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hung VW, Qin L, Cheung CS, Lam TP, Ng BK, Tse YK. Osteopenia: a new prognostic factor of curve progression in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am Vol. 2005;87(12):2709–2716. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yip BH, Yu FW, Wang Z, Hung VW, Lam TP, Ng BK. Prognostic value of bone mineral density on curve progression: a longitudinal cohort study of 513 girls with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:39220. doi: 10.1038/srep39220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Z, Chen H, Yu YE, Zhang J, Cheuk K-Y, Ng BKW. Unique local bone tissue characteristics in iliac crest bone biopsy from adolescent idiopathic scoliosis with severe spinal deformity. Sci Rep. 2017;7:40265. doi: 10.1038/srep40265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanabe H, Aota Y, Yamaguchi Y, Kaneko K, Imai S, Takahashi M. Minodronate treatment improves low bone mass and reduces progressive thoracic scoliosis in a mouse model of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang J, Chen H, Leung RKK, Choy KW, Lam TP, Ng BKW. Aberrant miR-145-5p/beta-catenin signal impairs osteocyte function in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. FASEB J Offic Pub Feder Am Soc Exp Biol. 2018 doi: 10.1096/fj.201800281. fj201800281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu M, Li G, Lee WW, Yuan M, Cui D, Weyand CM. Signal inhibition by the dual-specific phosphatase 4 impairs T cell-dependent B-cell responses with age. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(15):E879–E888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109797109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weber JA, Baxter DH, Zhang S, Huang DY, Huang KH, Lee MJ. The microRNA spectrum in 12 body fluids. Clin Chem. 2010;56(11):1733–1741. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.147405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heilmeier U, Hackl M, Skalicky S, Weilner S, Schroeder F, Vierlinger K. Serum miRNA signatures are indicative of skeletal fractures in postmenopausal women with and without type 2 diabetes and influence osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. J Bone Miner Res Offic J Am Soc Bone Miner Res. 2016;31(12):2173–2192. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deng L., Hu Y., Cheung J.P.Y., Luk K.D.K. A data-driven decision support system for scoliosis prognosis. IEEE Access. 2017;5:7874–7884. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hacquebord JH, Leopold SS. In brief: the Risser classification: a classic tool for the clinician treating adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(8):2335–2338. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2371-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Claudon A, Vergnaud P, Valverde C, Mayr A, Klause U, Garnero P. New automated multiplex assay for bone turnover markers in osteoporosis. Clin Chem. 2008;54(9):1554–1563. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.105866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng HH, Mitchell PS, Kroh EM, Dowell AE, Chery L, Siddiqui J. Circulating microRNA profiling identifies a subset of metastatic prostate cancer patients with evidence of cancer-associated hypoxia. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(7):e69239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sessa F, Maglietta F, Bertozzi G, Salerno M, Di Mizio G, Messina G. Human brain injury and miRNAs: an experimental study. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(7) doi: 10.3390/ijms20071546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tam EM, Yu FW, Hung VW, Liu Z, Liu KL, Ng BK. Are volumetric bone mineral density and bone micro-architecture associated with leptin and soluble leptin receptor levels in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis?–A case-control study. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2):e87939. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Man GC, Wang WW, Yeung BH, Lee SK, Ng BK, Hung WY. Abnormal proliferation and differentiation of osteoblasts from girls with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis to melatonin. J Pineal Res. 2010;49(1):69–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2010.00768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moreau A, Wang DS, Forget S, Azeddine B, Angeloni D, Fraschini F. Melatonin signaling dysfunction in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 2004;29(16):1772–1781. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000134567.52303.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheung CS, Lee WT, Tse YK, Lee KM, Guo X, Qin L. Generalized osteopenia in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis–association with abnormal pubertal growth, bone turnover, and calcium intake? Spine. 2006;31(3):330–338. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000197410.92525.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suh KT, Lee SS, Hwang SH, Kim SJ, Lee JS. Elevated soluble receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand and reduced bone mineral density in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Eur Spine J. 2007;16(10):1563–1569. doi: 10.1007/s00586-007-0390-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cordes KR, Sheehy NT, White MP, Berry EC, Morton SU, Muth AN. miR-145 and miR-143 regulate smooth muscle cell fate and plasticity. Nature. 2009;460(7256):705–710. doi: 10.1038/nature08195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shimode M, Ryouji A, Kozo N. Asymmetry of premotor time in the back muscles of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 2003;28(22):2535–2539. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000092375.61922.D1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wajchenberg M, Martins DE, Luciano Rde P, Puertas EB, Del Curto D, Schmidt B. Histochemical analysis of paraspinal rotator muscles from patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a cross-sectional study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94(8):e598. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weinstein S.L., Dolan L.A., Wright J.G., Dobbs M.B. Effects of bracing in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(16):1512–1521. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1307337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.