Abstract

Background:

While childhood vaccines are safe and effective, some parents remain hesitant to vaccinate their children, which has led to outbreaks of vaccine preventable diseases. The goal of this systematic review was to identify and summarize the range of beliefs around childhood vaccines elicited using open-ended questions, which are better suited for discovering beliefs compared to closed-ended questions.

Methods:

PubMed, Embase, and PsycINFO were searched using keywords for childhood vaccines, decision makers, beliefs, and attitudes to identify studies that collected primary data using a variety of open-ended questions regarding routine childhood vaccine beliefs in the United States. Study designs, population characteristics, vaccine types, and vaccine beliefs were abstracted. We conducted a qualitative analysis to conceptualize beliefs into themes and generated descriptive statistics.

Results:

Of 1,727 studies identified, 71 were included, focusing largely on parents (including in general, and those who were vaccine hesitant or at risk of hesitancy). Seven themes emerged: Adverse effects was most prominent, followed by mistrust, perceived lack of necessity, pro-vaccine opinions, skepticism about effectiveness, desire for autonomy, and morality concerns. The most commonly described beliefs included that vaccines can cause illnesses; a child’s immune system can be overwhelmed if receiving too many vaccines at once; vaccines contain harmful ingredients; younger children are more susceptible to vaccine adverse events; the purpose of vaccines is profit-making; and naturally developed immunity is better than that acquired from vaccines. Nearly a third of the studies exclusively assessed minority populations, and more than half of the studies examined beliefs only regarding HPV vaccine.

Conclusions:

Few studies used open-ended questions to elicit beliefs about vaccines. Many of the studies that did so, focused on HPV vaccine. Concerns about vaccine safety were the most commonly stated beliefs about childhood vaccines, likely because studies were designed to capture barriers and challenges to vaccination.

Keywords: vaccine beliefs, vaccine hesitancy, childhood vaccines, systematic review

Introduction

Childhood vaccination against a wide range of infectious diseases remains one of the greatest public health achievements of the last century. Yet in spite of overwhelming evidence that vaccines are safe[1] and effective [2], some parents are hesitant to vaccinate their children. While most parents fully vaccinate their children with most vaccines (influenza and HPV vaccine being notable exceptions) [3], there remain pockets of under- or unvaccinated children, which has led to outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases.[4]

In order to effectively address parents’ concerns, clinicians and policymakers must understand the full range of beliefs that parents and the public may have about childhood vaccines. A belief can be defined as a feeling that something exists or is true. Several well-established models of health behavior - including the health-belief model [5], the theory of planned behavior and theory of reasoned action [6], and protection-motivation theory [7] - propose that various types of beliefs motivate behavior, which in this case would be vaccination. In the context of vaccination, these can include beliefs about the risk of acquiring a disease, beliefs about the consequences of vaccinating or not vaccinating, beliefs about the effectiveness of vaccines, beliefs about how others view one’s own vaccination decisions, or beliefs about one’s ability to execute vaccine behavior.

Large-scale national surveys – such as the National Immunization Survey [8]– play a key role in determining the prominence of vaccine beliefs related to concerns about vaccines. Such surveys typically assess vaccine beliefs using closed-ended questions about vaccine safety or, if the survey queries particular vaccine beliefs, through the endorsement of options from a prespecified list. These types of questions pose a minimal respondent burden and make quantitative analyses of beliefs more feasible. While the information gleaned from these types of questions is an important contribution to our understanding of the landscape of vaccine beliefs, eliciting vaccine beliefs in an open-ended fashion allows for the discovery of beliefs that are not considered in closed-ended question batteries. Identifying such beliefs can in turn inform the development and design of closed-ended questions. This is particularly important to do repeatedly over time, given that beliefs about vaccines may be evolving over time.

The literature includes qualitative studies that use focus groups, interviews, and open-ended survey questions to capture vaccine beliefs in an open-ended way. However, systematic reviews of such studies have largely focused on which beliefs exist and have not identified areas that are understudied per se. The objective of this review was to systematically identify and qualitatively analyze the full range of elicited beliefs with regard to childhood vaccines in the published literature. Our study focuses on beliefs independent of actual vaccine behavior, recognizing that people who have negative beliefs towards vaccines may still ultimately decide to vaccinate their children, and vice versa. In addition, we examine which vaccines and populations are better studied, and identify areas that are relatively understudied.

Methods

Search strategy

In designing the review, we adhered to the PRISMA checklist, which is an evidence-based minimum set of items for reporting in systematic reviews and meta-analyses [9]. In November 2017, we searched PubMed, Embase, and PsycINFO using a combination of keywords (Table 1). The search was limited to English language. Studies were included if they were published from 1999 onward. We chose this year as the cut-off to ensure both reasonable scope and up-to-date studies, but also because this was the first full year after Andrew Wakefield published the now-retracted article linking MMR to autism.[10] Studies were eligible for inclusion if they collected primary data about vaccine beliefs using open-ended questions, meaning questions that would be answered by a response more detailed than “yes/no” (e.g., focus groups, interviews, open-ended survey questions). Some studies used questions were open-ended and did not specifically probe about vaccine concerns (such as “Have you heard about a vaccine for HPV? What have you heard?”), others used questions that probed specifically about vaccine concerns and hesitancy ( such as “Some people believe that vaccines are unnatural and that getting the disease is natural. What are your thoughts on this?”) while still others used a mix of both types of questions. Studies also had a focus on routine childhood vaccines that are currently in use in the United States (including influenza vaccine; for the full immunization schedule as of 2017, please see https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/downloads/past/2017-child.pdf) to be eligible for inclusion.[11] Studies were excluded if they: (1) were conducted outside of the U.S.; (2) were non-human studies; (3) used closed-ended questions only; or (4) were commentaries, editorials, case reports or conference proceedings. Our study focused on the United States because the review was designed to inform a future survey of the public in the United States, and beliefs around vaccines can vary by country for historical, structural or cultural reasons. We did not limit studies to those conducted solely with parents, as our objective included understanding the general public’s beliefs about vaccines.

Table 1.

Database Search Terms

| Database | Keywords/MeSH terms |

|---|---|

| PubMed | Decision* OR decision-making OR decision making OR belief* OR attitude* OR uptake OR |

| Embase | hesitancy (OR health knowledge, attitudes, practice)a |

| PsychINFO |

AND child* OR parent* OR mother* OR father* OR grandparent* OR grandmother* OR grandfather* AND vaccin* (OR vaccines OR vaccination OR vaccination refusal)a |

Terms in the parentheses were used in PubMed search only.

Article screening and data abstraction

Titles and abstracts that resulted from the search were screened by a senior researcher (CG) with clinical expertise in the area of vaccines and experience in systematic review methodology. This screening step focused solely on whether the article found by keyword searching had collected primary data on vaccine beliefs with open-ended questions. Articles with abstracts that met these criteria were then reviewed in full (again by CG) to confirm that the article included primary data collection with open-ended questions about vaccine beliefs.

Articles deemed relevant upon full-text review then had key study characteristics abstracted by another researcher (CC), supervised by the senior researcher (CG). These characteristics included study design, study population, vaccine types, vaccine beliefs as well as who were the subjects of these vaccine beliefs (typically the vaccine recipients). Vaccine beliefs were abstracted and recorded if they were mentioned anywhere in the article. We were unable to consistently quantify the strength of the belief, or frequency of how often it was mentioned in an article given the qualitative nature of the research reported. References of potentially relevant systematic and non-systematic reviews identified from the full-text screening were manually reviewed and searched (i.e., reference mined) for additional publications.

Analysis

We used an inductive approach to analyze the qualitative abstracted data. As we read through the beliefs abstracted from the articles, we developed categories to index the beliefs, and as new categories emerged, we reread the previously indexed beliefs and updated them when applicable. All the categories generated from this iterative process were then further conceptualized into broader themes. Simple counts for the number of articles in which a belief appeared were obtained and summarized by both theme and belief.

Post hoc analysis

To evaluate whether the included studies are representative of the body of literature examining vaccine beliefs and to better understand how our included studies fit in the larger literature returned from the keyword search, we randomly sampled and analyzed 150 excluded articles. We abstracted and recorded information on why the article was excluded, which vaccine(s) were assessed (if applicable), which questions were asked (if applicable), and whether the article reported results from the National Immunization Survey.

Results

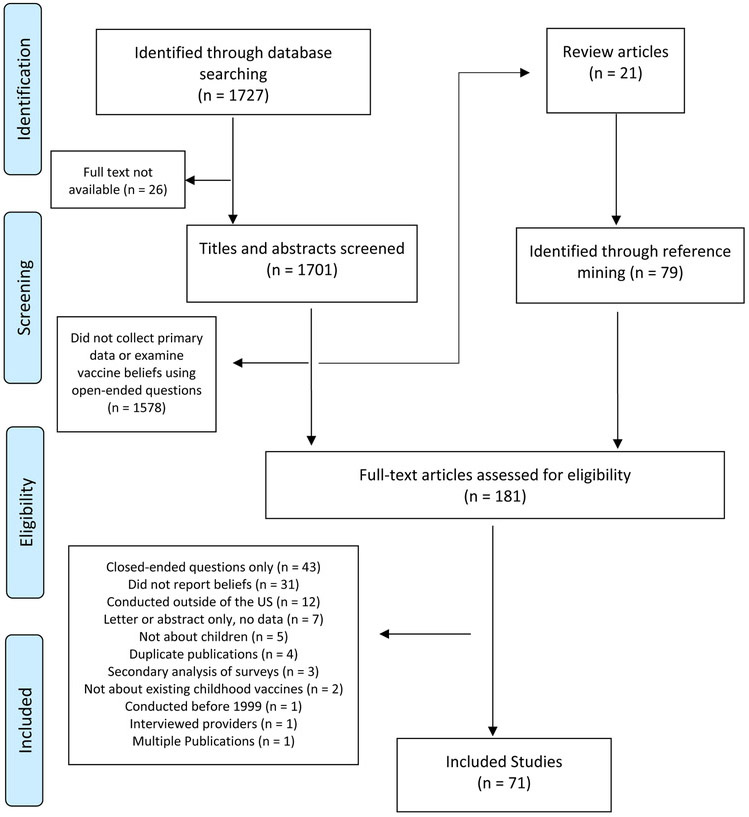

A total of 1,727 titles were identified through database searching (Figure 1). Of these, 26 were not available for further review and a further 1,578 did not collect primary data on vaccine beliefs using open-ended questions based on abstract screening. Of the remaining 123 studies, 21 were identified as review articles and set aside for reference mining. Of the 181 studies (including 79 identified through reference mining of the 21 review articles) that entered the full-text review, 109 were excluded for reasons such as not using open-ended questions, not reporting vaccine beliefs, and/or not being a US study, which ultimately left 71 articles (51 from original database searching; 20 from reference mining) included for data abstraction.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study inclusion

Study characteristics

Methodologies.

The included studies varied in terms of methodology used (Table 2). Most studies (N=26) used semi-structured interviews with total sample sizes ranging from 12-129 subjects (median 33.5). Seventeen studies used focus groups (sample size 12-129, median 52.5), 9 studies used surveys with one or more open-ended questions (sample size 53-2,315, median 287), and three studies used unstructured interviews (sample size 25-124, median 74.5). Thirteen studies employed a mixed approach using one or more of the above designs. The remaining three studies were social media analyses (N=2) and an analysis of audio-taped conversations (N=1).

Table 2.

Summary of study characteristics

| Author, Year |

Study Design | Sample Size | Population | Race/Ethnicity | Vaccine Mentioned |

Subject of Beliefs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexander, 2012 [17] | Semi-structured interview | 42 | Parents and sons | NS | HPV | Adolescent boys |

| Allen, 2012 [18] | Focus group | 64 | Parents | NS | HPV | Adolescent girls |

| Bahta, 2015 [19] | Unstructured interview | NR | Parents | African American | MMR | Children >=1 year old |

| Bair, 2008 [20] | Semi-structured interview | 40 | Mothers | Hispanic or Latino | HPV | Adolescent girls |

| Bardenheier, 2004 [21] | Survey with open-ended question(s) | 2315 | Parents | NS | MCV/MMR; DTP/DTaP; Hep B | Children 19 - 35 months old |

| Benin, 2006 [22] | Semi-structured interview | 33 | Mothers | NS | NS | Children <=6 months old |

| Blaisdell, 2016 [23] | Focus group | 42 | Parents | NS | NS | Children <=8 years old |

| Brawner, 2013 [24] | Survey; semi-structured interview; focus group | 141 | Parents and adolescent girls | NS | HPV | Adolescent girls |

| Brunson, 2015 [25] | Unstructured and semi-structured interviews | 25 | Parents | NS | NS | Children <=18 months |

| Cates, 2012 [26] | Semi-structured interview; focus group | 129 | Parents | African American | HPV | Adolescent boys |

| Constantine, 2007 [27] | Survey with open-ended question(s) | 522 | Parents | NS | HPV | Adolescent girls |

| Dailey, 2017 [28] | Semi-structued interview | 20 | Parents | African American | HPV | Adolescents |

| Dela Cruz, 2017 [29] | Semi-structured interview | 20 | Parents | NS | HPV | Adolescents |

| Do, 2009 [30] | Focus group | 37 | Parents | Other | HPV | Adolescent girls - young women |

| Downs, 2008 [31] | Semi-structured interview | 30 | Parents | NS | MMR | Children 18 - 23 months old |

| Faasse, 201 [32] | Social media analysis | 1490 comments | NR | NS | NS | NS |

| Fontenot, 2015 [33] | Focus group | 81 | Parents | NS | HPV9 | Adolescent girls |

| Fredrickson, 2004 [34] | Focus group | NR | Parents | NS | Hep B; Varicella | NS |

| Galbraith-Gyan, 2017 [35] | Semi-structured interview | 62 | Mothers and daughters | African American | HPV | Adolescent girls |

| Garg, 2017 [36] | Survey with open-ended question(s) | 160 | Mothers | NS | NS | Children >=3 years old |

| Gazmararian, 2010 [37] | Focus group | 54 | Mothers | NS | Influenza | Children 5 - 12 years old |

| Getrich, 2014 [38] | Structured and semi-structured interviews | 22 | Mothers and daughters | Hispanic or Latino | HPV | Adolescent girls |

| Goff, 2011 [39] | Analysis of audio-taped conversations | 184 visits | Parents and adolescent girls | NS | HPV | Adolescent girls - young women |

| Gowda, 2012 [40] | Focus group | 65 | Parents and adolescents | NS | NS | Adolescents |

| Griffioen, 2012 [41] | Semi-structured interview | 65 | Mothers and daughters | NS | HPV | Adolescent girls |

| Gullion, 2008 [42] | Semi-structured interview | 25 | Parents | NS | NS | NS |

| Gust, 2007 [43] | Focus group | 129 | Mothers | NS | NS | Children <=5 years old |

| Hansen, 2016 [44] | Semi-structured interview | 45 | Parents | African American; Hispanic or Latino; Other | HPV | Adolescents |

| Herbert, 2013 [45] | Focus group | 85 | Parents and adolescents | NS | Influenza | Adolescents |

| Hughes, 2011 [46] | Semi-structured interview | 40 | Mothers and daughters/sons | NS | HPV | Adolescent girls |

| Hull, 2014 [47] | Semi-structured interview; focus group | 65 | Mothers and daughters | African American | HPV | Adolescent girls |

| Joseph, 2012 [48] | Semi-structured interview | 70 | Mothers | African American; Other | HPV | Adolescent girls |

| Katz, 2009 [49] | Focus group | 19 | Parents | NS | HPV | Adolescent girls |

| Katz, 2016 [50] | Semi-structured interview | 48 | Parents and adolescents | African American; Hispanic or Latino | HPV | Adolescents |

| Luque, 2012 [51] | Focus group | 12 | Parents | Hispanic or Latino | HPV | Adolescent girls |

| Luthy, 2010 [52] | Survey with open-ended question(s) | 61 | Parents | NS | NS | Children 6 months - 17 years old |

| Luthy, 2012 [53] | Survey with open-ended question(s) | 287 | Parents | NS | NS | Children 5 - 18 years old |

| Luthy, 2013 [54] | Survey with open-ended question(s) | 250 | Parents | NS | NS | Children 5 - 18 years old |

| Maertens, 2017 [55] | Focus group | 47 | Parents and young adult women | Hispanic or Latino | HPV | Adolescent girls |

| McCauley, 2012 [56] | Survey with open-ended question(s) | 1500 | Parents | NS | NS | Children 6 -23 months old |

| Meleo-Erwin, 2017 [57] | Social media analysis | 698 comments | Audience of parenting blogs | NS | NS | NS |

| Mendel-Van Alstyne, 2017 [58] | Focus group | 61 | Mothers | NS | NS | Children <=5 years old |

| Middleman, 2012 [59] | Focus group | 37 | Parents | NS | Influenza | Children 5 - 18 years old |

| Miller, 2014 [60] | Survey; focus group | 50 | Adolescents | African American; Other | HPV | Adolescents |

| Morales-Campos, 2013 [61] | Focus group | 52 | Mothers and daughters | Hispanic or Latino | HPV | Adolescent girls |

| Mullins, 2015 [62] | Semi-structured interview | 25 | Adolescent girls | NS | HPV | Adolescent girls |

| Niccolai, 2014 [63] | Semi-structured interview | 38 | Parents | NS | HPV | Adolescents |

| Nodulman, 2015 [64] | Semi-structured interview; focus group | 105 | Parents and adolescents | NS | HPV | Adolescents |

| Olshen, 2005 [65] | Semi-structured interview; focus group | 25 | Parents | NS | HPV | Adolescents |

| Perkins, 2013 [66] | Semi-structured interview | 120 | Parents | African American, Hispanic or Latino, White | HPV | Adolescent boys |

| Perkins, 2014 [67] | Unstructured interview | 124 | Parents | NS | HPV | Adolescent girls |

| Perkins, 2016 [68] | Semi-structured interview | 65 | Parents | NS | HPV | Adolescent girls |

| Reich, 2014 [69] | Unstructured interview | 25 | Mothers | NS | NS | Children 5 - 18 years old |

| Rendle, 2017 [70] | Survey; semi-structured interview | 27 | Parents | NS | HPV | Adolescents |

| Roncancio, 2016 [71] | Semi-structured interview | 34 | Mothers | Hispanic or Latino | HPV | Adolescent girls |

| Roncancio, 2017 [72] | Semi-structured interview | 32 | Mothers | Hispanic or Latino | HPV | Adolescent girls |

| Saada, 2015 [73] | Semi-structured interview | 24 | Parents | NS | HAV; HBV; VZV; Rotavirus; Influenza; MMR | Children 12 - 36 months old |

| Sanders Thompson, 2012 [74] | Semi-structured interview | 30 | Parents | African American | HPV | Adolescent girls |

| Schmidt-Grimminger, 2013 [75] | Survey; focus group | 56 | Mothers, young adult women, adolescent girls | Other | HPV | Adolescents |

| Senier, 2008 [76] | Semi-structured interview | 20 | Parents | NS | NS | Children 18 months - 16 years old |

| Shui, 2005 [77] | Focus group | 53 | Mothers | African American | NS | Children 18 - 35 months old |

| Sobo, 2015 [78] | Semi-structured interview; focus group | 36 | Parents | NS | Varicella; MMR; DTaP; Polio; Hep B | Children 4 - 18 years old |

| Sobo, 2016 [79, 80] | Survey with open-ended question(s) | 53 | Parents | NS | NS | Children <=5 years old |

| Vercruysse, 2016 [81] | Semi-structured interview | 129 | Parents | NS | HPV | Adolescent girls |

| Wang, 2015 [82] | Semi-structured interview | 23 | Parents | NS | NS | Children 18 months - 6 years old |

| Warner, 2015 [83] | Survey; focus group | 52 | Parents | Hispanic or Latino | HPV | Adolescents |

| Wenger, 2011 [84] | Survey with open-ended question(s) | 360 | Parents | NS | NS | NS |

| Wentzell, 2016 [85] | Structured and semi-structured interviews | 20 | Mothers | Hispanic or Latino | HPV | Adolescent girls |

| Westrick, 2017 [86] | Semi-structured interview | 26 | Parents | NS | HPV | Adolescents |

| Wilson, 2000 [87] | Semi-structured interview | 12 | Mothers | NS | NS | Children <=3 years old |

| Wilson, 2013 [88] | Focus group | 44 | Mothers | African American; Other | HPV | Adolescents - young adults |

Populations.

The majority of the studies focused on parents as the study population (67/71), with some including parents in general and others specifically those that were vaccine-hesitant or were part of a population thought to be at high risk of vaccine hesitancy based on vaccination rates (e.g., Somali immigrants in Minnesota). Of studies focusing on parents, 14 studies involved only mothers, 13 studies also included parents’ adolescent children, and two included young adult women in addition to parents and/or adolescents. Two studies included only adolescents, and two did not specify the study population. Almost a third of the studies assessed exclusively minority populations (24/71). Of these, nine included only Hispanic or Latino participants, seven included only African Americans, two included other minorities, and six included one or more of the above populations.

Vaccines.

More than half of the studies examined beliefs about HPV vaccine (41/71), three studies examined beliefs about influenza vaccines, two studies examined beliefs about MMR, and 21 studies reported beliefs about vaccines in general. The remainder reported beliefs regarding multiple childhood vaccines such as the Hepatitis B, varicella, and Tdap (tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis) vaccines (4/71).

Vaccine beliefs

Overall, the studies we examined appeared to be designed to understand barriers and challenges to vaccination. Participants’ responses were often presented in quotes or, less commonly, summarized in tables. The most frequently cited beliefs included that vaccines can cause illnesses; a child’s immune system can be overwhelmed if receiving too many vaccines at a time; vaccines contain harmful ingredients; younger children are more susceptible to vaccine adverse events; the purpose of vaccines is profit-making; and naturally developed immunity is better than that acquired from vaccines. Seven themes emerged from the abstracted beliefs, including (in order of prevalence from most to least): adverse effects, mistrust, perceived lack of necessity, pro-vaccine opinions, skepticism about effectiveness, desire for autonomy and morality concerns (Table 3). Below we detail beliefs as they relate to each of the themes. Adverse effects. In half of the studies, respondents actively expressed the belief that vaccine can cause illnesses. Aside from autism, vaccines were most frequently perceived to be associated with dysfunction of the immune system, developmental and neurological disorders, behavioral issues, diabetes, liver problems, cancer, and death. There was also concern that vaccines could transmit diseases, including those they intended to prevent such as influenza, and in rare cases, HIV (possibly due to the confusion of HIV and HPV) (Table 4). In addition, respondents in some studies reported the belief that a child’s immune system could be overwhelmed if receiving too many vaccines at a time and that vaccines contain harmful ingredients such as mercury (in the form of thimerosal), aluminum, and others. In 9 out of the 71 studies, respondents also expressed concerns about younger children being more susceptible to vaccine adverse events.

Table 3.

General vaccine beliefs (excluding HPV vaccine), organized by theme

| Theme | Belief | Number of Studies (N = 71) |

|---|---|---|

| Adverse effects | Vaccines cause diseases/illnesses | 36 |

| Taking too many vaccines overloads immune system | 13 | |

| Vaccines contain harmful ingredients | 12 | |

| Younger children are more susceptible to vaccine risks | 9 | |

| Vaccine is too new/not fully studied | 4 | |

| Vaccines do not work for everyone | 3 | |

| Herd immunity increases risks of VPD | 1 | |

| Mistrust | Profit motive | 8 |

| Mistrust of doctors | 3 | |

| Black children are given low quality vaccines | 2 | |

| Mistrust of government/doctors | 2 | |

| Mistrust of government/doctors/pharma | 2 | |

| Mistrust of government/pharma | 2 | |

| Mistrust of pharma | 2 | |

| Lack of necessity | Naturally developed immunity is superior | 6 |

| Natural remedies as substitutes for vaccines | 4 | |

| Environmental control as substitute for vaccines | 3 | |

| VPD is not severe | 2 | |

| Herd immunity works so vaccination is not necessary | 1 | |

| Lifestyle choices as substitutes for vaccines | 1 | |

| Vaccine is unnatural human intervention | 1 | |

| Pro-vaccine opinions | Child deserves protection | 4 |

| Vaccine is therapeutic | 4 | |

| Doctors/public health experts have the public's best interests in mind | 1 | |

| Vaccination protects household economy and social capital | 1 | |

| Vaccine protects reproductive capability at some ages | 1 | |

| Vaccines serve the greater good | 1 | |

| Skepticism about effectiveness | Herd immunity does not work | 2 |

| Vaccine schedule is not related to effectiveness | 2 | |

| Vaccines become ineffective after multiple doses | 1 | |

| Vaccines do not work | 1 | |

| Desire for autonomy | Herd immunity implies herd mentality | 1 |

| Mandate implies importance of a vaccine | 1 | |

| Vaccine decision is a parent's right | 1 | |

| Morality concerns | Some vaccine ingredients are derived from fetuses | 1 |

Table 4.

Illnesses mentioned in studies

| Illness (general) |

| ADHD |

| Allergies |

| Asthma |

| Autism |

| Autoimmune disease |

| Behavioral issues |

| Cancer |

| Death |

| Developmental regression |

| Diabetes |

| Disease that vaccine is protecting against (e.g., influenza illness from influenza vaccine) |

| Guillain-Barre syndrome |

| HIV |

| Immune system compromise |

| Infertility (HPV only) |

| Irregular menses (HPV only) |

| Learning disabilities |

| Liver problems |

| Premature menarche (HPV only) |

| Seizures |

| SIDS |

Mistrust.

In 11 of the studies, at least some participants expressed mistrust in physicians, pharmaceutical companies, and/or the government when it comes to vaccines. Studies most often reported that respondents expressed the belief that vaccines are created and distributed for profit rather than disease prevention (reported in eight of these studies). Some African-American parents in two studies reported the belief that their children received lower quality vaccines than others.

Perceived lack of necessity.

The theme of necessity primarily emerged as a lack of necessity for vaccines. In six studies, participants believed that “naturally” acquired immunity (i.e. from actual infection with a pathogen) is better than immunity acquired in response to vaccines. Others believed that the health effects of vaccines could instead be achieved by other means such as natural remedies (reported in four studies), control of environmental exposures (reported in three studies) or lifestyle choices (reported in one study).

Pro-vaccine opinions.

Participants in four of the studies expressed the belief that vaccines protect children from illnesses, although some appeared to erroneously believe that vaccines treat diseases or promote health beyond their purposes.

Skepticism about effectiveness, desire for autonomy, morality concerns.

In some studies, respondents expressed skepticism about the validity of herd immunity, either from the scientific perspective (two studies) or from the perspective of individual liberty (one study). For instances, some respondents reported the belief that diseases come and go in cycles that are not correlated with herd immunity, and others related herd immunity with “herd mentality”. Lastly, a small number of the participants in one study were concerned that some vaccines or their ingredients are derived from aborted fetal tissue.

HPV-specific beliefs.

Of the HPV-specific beliefs (Table 5), adverse effects again was the most prominent theme, followed by lack of necessity, pro-vaccine opinions, morality, and skepticism about effectiveness. In particular, participants in 21 out of 41 HPV-related studies reported believing that HPV vaccine can lead to promiscuity or risky sexual behaviors. In 11 studies, participants shared concerns that HPV vaccine is too new and not fully tested. Participants in seven studies believed that HPV vaccine can cause mortality and morbidity related to the reproductive system and behavioral changes. Finally, many participants also believed that HPV vaccine are not necessary if their children are not sexually active (expressed in 17 studies).

Table 5.

List of HPV-specific beliefs, organized by theme

| Theme | Belief | Number of Studies (N = 41 ) |

|---|---|---|

| Adverse effects | HPV vaccine promotes sexual activity | 21 |

| HPV vaccine is too new/not fully studied | 11 | |

| HPV vaccine causes diseases/illnesses | 7 | |

| Perceived lack of necessity | HPV vaccine is not necessary if child is not sexually active | 17 |

| Pro-vaccine opinions | HPV vaccine would not influence sexual behavior | 4 |

| HPV vaccine also prevents other STIs | 2 | |

| HPV vaccine will be effective for life | 1 | |

| Morality concerns | HPV vaccine stigmatizes recipients by implying sexual activeness or promiscuity | 3 |

| Skepticism about effectiveness | HPV vaccine is ineffective like influenza vaccine | 2 |

We found that, compared to HPV vaccine, older vaccines were less well studied. For example, the MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) and influenza vaccines were specifically included in only five and four studies, respectively. In addition, of the 24 studies that exclusively included minority populations, only two studies specifically examined minority populations other than African-Americans or Latinos (Native Americans and Cambodian-Americans).

Post hoc analysis

Of the 150 article sample we read of the excluded articles, 66.7% of them were not about vaccine beliefs in the general population. These studies either did not examine a vaccine or population of interest or, if they did, assessed vaccine coverage, vaccine efficacy, epidemiology of vaccine preventable diseases, intervention effects, vaccination practices and policies, and other issues that were related to vaccines but not beliefs. Of the remaining one third (N=50) that were about vaccine beliefs, 62% used closed-ended vaccine questions while only 10% used open-ended question; two (4%) reported from the National Immunization Study; 32% were about HPV vaccine, 26% about childhood vaccines generally, 14% about influenza vaccine, and 2% each about MMR, polio and hepatitis A vaccines. Of the studies that used closed-ended questions (N=31), 48% were about HPV vaccine, 32% about general childhood vaccines, 16% about influenza vaccines and 3% about the individual vaccine respectively.

Discussion

Our study is the first to review and summarize the public’s beliefs about childhood vaccines in the United States based on their responses to open-ended questions. Our findings provide not only a comprehensive list of beliefs about vaccines, as volunteered in response to open-ended questions, but further suggest that such beliefs can be conceptualized into seven main themes: adverse effects, skepticism about effectiveness, perceived lack of necessity, mistrust, pro-vaccine opinions, desire for autonomy, and morality concerns. However, while beliefs regarding adverse effects of vaccines were common across early childhood vaccines and the HPV vaccine, discussions of morality (sexuality and the perceived associated risks) were also common with the latter.

Our review focused on synthesizing vaccine beliefs elicited directly from respondents using open-ended questions, but relatively few studies proactively elicited vaccine beliefs in this way as compared to the full set of articles returned by the keywords. While studies that use closed-ended questions may have used qualitative work to inform the questions, such work was often not reported or was not easily searchable or identifiable in the literature. Fielding open-ended questions and publishing the results are important, as such findings are invaluable to discovering the full range of vaccine beliefs, including gaps to consider in developing closed-ended survey instruments. For example, one prominent theme we identified was mistrust, including of the medical profession, pharmaceutical industry and government. However, large national surveys such as NIS do not contain questions about trust beyond asking whether the child's health provider is the most trusted source of vaccine information. Conversely, some of the pro-vaccine beliefs reported in the studies pertain to anti-conspiracy or pro-establishment type of thinking that could benefit from probing within a survey such as the NIS. For example, some respondents believed doctors and the public health experts have the public’s best interest in mind, and that vaccines serve the greater good in the society. In addition to uncovering the current range of vaccine beliefs, given the potential for emergence and spread of new vaccine beliefs over time – particularly in the age of social media – an ongoing mechanism to understand what new beliefs may be arising is important for successful, targeted communication about vaccines and vaccine safety.

Overall, most vaccine beliefs that were reported were negative towards vaccines. There are a variety of possible reasons for this finding. First, the studies were typically designed specifically to assess barriers and challenges to vaccination, and thus more likely to both gather and report on negative beliefs to vaccines. This finding may also be a function of the populations chosen to participate, as vaccine-hesitant parents may either have been the target study population and/or more likely to participate in a study about vaccines. Once part of a study, respondents who feel positively about vaccines are less likely to express supportive beliefs (particularly in the context of a study designed to elicit barriers and challenges), whereas respondents who feel negatively about vaccines are more likely to be vocal about such beliefs. Finally, studies that report concerns about vaccines may also be more likely to be written up and/or published. Such potential for both recruitment and publication bias, and the qualitative nature of these studies, means that our findings cannot be taken to proportionally represent the general population’s vaccine beliefs, but rather the range of possible beliefs around vaccines with the goal of informing future research, including close-ended survey questions.

Our review identified a disproportionate number of studies focusing on HPV vaccine (57.7%) compared to other vaccines among the included articles. We observed the same pattern in the articles with closed-ended questions from among the random sample of 150 excluded articles (48% were about HPV). The predominance of studies examining HPV vaccine beliefs may explain why the majority of the studies we analyzed (about 75%) were concentrated in the more recent past between 2012 and 2017. The first HPV vaccine was released in 2006 and studies would take another few years to be funded and completed.

The reasons for the predominance of HPV research are likely to be multifactorial. First, the HPV vaccine is relatively new and as a consequence may have more implementation research funding available. However, the relatively recent introduction doesn’t fully explain why HPV vaccine is especially heavily studied, as several other new vaccines were introduced to the routine childhood immunization schedule during our study period, including rotavirus vaccine, pneumococcal vaccine, influenza vaccine (for all children as opposed to high-risk), and meningococcal vaccines for adolescents. [12] We do note that compared to other childhood and adolescent vaccines (except for seasonal influenza vaccine), HPV vaccination rates remain low at 53% for girls and 44% for boys for vaccination with the full series. [13] Second, there has been significant controversy surrounding the HPV vaccine primarily related to whether a vaccine for sexually-transmitted infections should be administered during the early adolescent years.[14] There has also been significant political debate about the role of mandatory vaccination for HPV.[15] These concerns, which often invoke moral arguments, may have contributed to the relatively lower HPV vaccine coverage compared to other childhood vaccines and thus attracted more attention in researching HPV vaccine beliefs. Finally, efforts to study vaccine beliefs may have been spurred by the perception that parents have a higher level of concern about the adverse effects of HPV vaccine, though this is purely speculative.

In addition, nearly a third of the studies exclusively examined minority populations, particularly Latinos and African Americans. This focus makes sense given that such populations are at higher risk for HPV-associated cervical cancer, likely because of decreased access to screening and follow-up treatments [16]. Nonetheless, although such populations often suffer health-related disparities related to HPV, black and Hispanic adolescents actually have higher up-to-date vaccination rates compared to their white counterparts, at 50.2% and 56.4% respectively compared to 44.7% in 2017 [13]. Thus, for these particular populations, the proportion of studies about HPV vaccine may not align with current epidemiology of vaccination and efforts could be turned elsewhere. Other minority populations remained relatively understudied. Only two studies specifically included populations that are not African Americans or Latinos. It is possible that these populations experience similar disparities in terms of risk of disease and access to care, and their uptake of various vaccines and beliefs around vaccines may warrant further study. In addition, adolescents living in rural areas are less likely than those living in urban areas to be vaccinated for HPV (even after controlling for poverty levels). Undervaccination for HPV may occur for a variety of possible reasons, including lower knowledge of HPV, shortage of pediatric providers, and/or access to providers with less understanding of the importance of HPV vaccine. [13] One limitation of our study is that we did not abstract socioeconomic characteristics of respondents, nor rurality, and this represents an area for future study. Understanding the reasons for undervaccination across all populations remains important, as the reason for un- or under-vaccination may vary based on demographic characteristics.

This review has some limitations. First, as mentioned above, the studies we examined tended to focus on assessing barriers and challenges to vaccinations; therefore, the findings are likely to be biased toward negative beliefs about vaccines. However, for the purposes of overcoming barriers to vaccination, understanding negative beliefs about vaccines is important to inform effective communication and interventions. In addition, the qualitative nature of these studies makes it difficult to synthesize results quantitatively. We reported a simple count of beliefs by the number of studies in which they were mentioned at all by the authors in an attempt to identify which beliefs were most common across studies. It was not possible to quantify the strength of beliefs in terms of the number of subjects holding these beliefs. As noted above, the nature of our review and of qualitative study design means that we cannot draw conclusions about the actual prevalence of the beliefs identified in the general population, particularly for pro-vaccine beliefs.

Conclusion

This systematic review synthesizes published studies about beliefs related to childhood vaccines in the United States. The majority (57%) of studies examined vaccine beliefs around HPV vaccine, possibly due to it being one of the most recently introduced vaccines and/or because it has the lowest vaccination rate of all adolescent vaccines. We found that concerns about vaccine adverse effects remain the most commonly documented type of belief. In addition, mistrust in medical professions, pharmaceutical industry and the government as another common theme may exacerbate the public’s vaccine hesitancy. However, the latter has received less attention compared to other factors that influence vaccine confidence. As a result, in addition to devising messages that address individual parents’ concerns, further research to understand the causes of mistrust and its mediating effects in vaccine decision-making would be helpful.

Highlights.

Few studies elicited the public’s vaccine beliefs using open-ended questions

Concerns about vaccine safety are the most commonly stated beliefs

Mistrust in physicians, pharma, and the government may exacerbate hesitancy

The majority of studies (57%) focused on HPV vaccines

Nearly a third of the studies exclusively examined Latinos and African Americans

Acknowledgements

We thank Jody Larkin, Research Librarian, RAND Corporation, for the assistance with the design and implementation of literature searches.

Funding source: This research was supported by NIH/NICHD grant R21HD087749.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Maglione MA, et al. , Safety of vaccines used for routine immunization of U.S. children: a systematic review. Pediatrics, 2014. 134(2): p. 325–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitney CG, et al. , Benefits from immunization during the vaccines for children program era - United States, 1994-2013. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 2014. 63(16): p. 352–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Center for Health Statistics, Health, United States, 2016: with chartbook on long-term trends in health. 2017. [PubMed]

- 4.Salmon DA, et al. , Vaccine hesitancy: Causes, consequences, and a call to action. Vaccine, 2015. 33 Suppl 4: p. D66–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janz NK and Becker MH, The Health Belief Model: a decade later. Health Educ Q, 1984. 11(1): p. 1–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fishbein M and Ajzen I, Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach. 2011: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rogers RW, A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change1. The journal of psychology, 1975. 91(1): p. 93–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zell ER, et al. , National Immunization Survey: the methodology of a vaccination surveillance system. Public Health Reports, 2000. 115(1): p. 65–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moher D, et al. , Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of internal medicine, 2009. 151(4): p. 264–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wakefield AJ, et al. , RETRACTED: Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children. 1998, Elsevier. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended Immunization Schedule for Children and Adolescents Aged 18 Years or Younger, UNITED STATES, 2017. 2017. [cited 2019 May 8]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/downloads/past/2017-child.pdf.

- 12.Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Vaccine History: Vaccine Availability Timeline. 2014. June 28, 2016 [cited 2018 July 12]; Available from: https://www.chop.edu/centers-programs/vaccine-education-center/vaccine-history/vaccine-availability-timeline.

- 13.Walker TY, et al. , National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years—United States, 2017. MMMR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 2018. 67(33): p. 909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White MD, Pros, cons, and ethics of HPV vaccine in teens—Why such controversy? Translational Andrology and Urology, 2014. 3(4): p. 429–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gostin LO, Mandatory HPV vaccination and political debate. Jama, 2011. 306(15): p. 1699–1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Viens LJ, Human papillomavirus–associated cancers—United States, 2008–2012. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 2016. 65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alexander AB, et al. , Parent-son decision-making about human papillomavirus vaccination: a qualitative analysis. BMC Pediatr, 2012. 12: p. 192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allen JD, et al. , Decision-Making about the HPV Vaccine among Ethnically Diverse Parents: Implications for Health Communications. J Oncol, 2012. 2012: p. 401979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bahta L and Ashkir A, Addressing MMR Vaccine Resistance in Minnesota's Somali Community. Minn Med, 2015. 98(10): p. 33–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bair RM, et al. , Acceptability of the human papillomavirus vaccine among Latina mothers. Journal of pediatric and adolescent gynecology, 2008. 21(6): p. 329–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bardenheier B, et al. , Are parental vaccine safety concerns associated with receipt of measles-mumps-rubella, diphtheria and tetanus toxoids with acellular pertussis, or hepatitis B vaccines by children? Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine, 2004. 158(6): p. 569–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benin AL, et al. , Qualitative analysis of mothers' decision-making about vaccines for infants: the importance of trust. Pediatrics, 2006. 117(5): p. 1532–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blaisdell LL, et al. , Unknown Risks: Parental Hesitation about Vaccination. Med Decis Making, 2016. 36(4): p. 479–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brawner BM, et al. , The development of a culturally relevant, theoretically driven HPV prevention intervention for urban adolescent females and their parents/guardians. Health Promot Pract, 2013. 14(4): p. 624–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brunson EK, Identifying Parents Who Are Amenable to Pro-Vaccination Conversations. Glob Pediatr Health, 2015. 2: p. 2333794×15616332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cates JR, et al. , Designing messages to motivate parents to get their preteenage sons vaccinated against human papillomavirus. Perspect Sex Reprod Health, 2012. 44(1): p. 39–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Constantine NA and Jerman P, Acceptance of human papillomavirus vaccination among Californian parents of daughters: a representative statewide analysis. Journal of Adolescent Health, 2007. 40(2): p. 108–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dailey PM and Krieger JL, Communication and US-Somali Immigrant Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccine Decision-Making. J Cancer Educ, 2017. 32(3): p. 516–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dela Cruz MRI, et al. , Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccination Motivators, Barriers, and Brochure Preferences Among Parents in Multicultural Hawai'i: a Qualitative Study. J Cancer Educ, 2017. 32(3): p. 613–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Do H, et al. , HPV vaccine knowledge and beliefs among Cambodian American parents and community leaders. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP, 2009. 10(3): p. 339. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Downs JS, de Bruin WB, and Fischhoff B, Parents' vaccination comprehension and decisions. Vaccine, 2008. 26(12): p. 1595–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faasse K, Chatman CJ, and Martin LR, A comparison of language use in pro- and anti-vaccination comments in response to a high profile Facebook post. Vaccine, 2016. 34(47): p. 5808–5814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fontenot HB, Domush V, and Zimet GD, Parental Attitudes and Beliefs Regarding the Nine-Valent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine. J Adolesc Health, 2015. 57(6): p. 595–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fredrickson DD, et al. , Childhood immunization refusal: provider and parent perceptions. FAMILY MEDICINE-KANSAS CITY-, 2004. 36: p. 431–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Galbraith-Gyan KV, et al. , HPV vaccine acceptance among African-American mothers and their daughters: an inquiry grounded in culture. Ethn Health, 2017: p. 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garg R, et al. , Illness Representations of Pertussis and Predictors of Child Vaccination Among Mothers in a Strict Vaccination Exemption State. Matern Child Health J, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gazmararian JA, et al. , Maternal knowledge and attitudes toward influenza vaccination: a focus group study in metropolitan Atlanta. Clin Pediatr (Phila), 2010. 49(11): p. 1018–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Getrich CM, et al. , Different models of HPV vaccine decision-making among adolescent girls, parents, and health-care clinicians in New Mexico. Ethn Health, 2014. 19(1): p. 47–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goff SL, et al. , Vaccine counseling: A content analysis of patient–physician discussions regarding human papilloma virus vaccine. Vaccine, 2011. 29(43): p. 7343–7349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gowda C, et al. , Understanding attitudes toward adolescent vaccination and the decision-making dynamic among adolescents, parents and providers. BMC Public Health, 2012. 12: p. 509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Griffioen AM, et al. , Perspectives on decision making about human papillomavirus vaccination among 11- to 12-year-old girls and their mothers. Clin Pediatr (Phila), 2012. 51(6): p. 560–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gullion JS, Henry L, and Gullion G, Deciding to opt out of childhood vaccination mandates. Public Health Nursing, 2008. 25(5): p. 401–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gust DA, et al. , Developing tailored immunization materials for concerned mothers. Health education research, 2007. 23(3): p. 499–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hansen CE, et al. , "It All Depends": A Qualitative Study of Parents' Views of Human Papillomavirus Vaccine for their Adolescents at Ages 11-12 years. J Cancer Educ, 2016. 31(1): p. 147–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Herbert NL, et al. , Understanding reasons for participating in a school-based influenza vaccination program and decision-making dynamics among adolescents and parents. Health Educ Res, 2013. 28(4): p. 663–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hughes CC, et al. , HPV vaccine decision making in pediatric primary care: a semi-structured interview study. BMC Pediatr, 2011. 11: p. 74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hull PC, et al. , HPV vaccine use among African American girls: qualitative formative research using a participatory social marketing approach. Gynecol Oncol, 2014. 132 Suppl 1: p. S13–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Joseph NP, et al. , Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs regarding HPV vaccination: Ethnic and cultural differences between African-American and Haitian immigrant women. Women's Health Issues, 2012. 22(6): p. e571–e579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Katz M et al. , Acceptance of the HPV vaccine among women, parents, community leaders, and healthcare providers in Ohio Appalachia. Vaccine, 2009. 27(30): p. 3945–3952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Katz IT, et al. , Barriers to HPV immunization among blacks and latinos: a qualitative analysis of caregivers, adolescents, and providers. BMC Public Health, 2016. 16(1): p. 874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Luque JS, Raychowdhury S, and Weaver M, Health care provider challenges for reaching Hispanic immigrants with HPV vaccination in rural Georgia. Rural Remote Health, 2012. 12(2): p. 1975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Luthy KE, Beckstrand RL, and Callister LC, Parental hesitation in immunizing children in Utah. Public Health Nursing, 2010. 27(1): p. 25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Luthy KE, et al. , Reasons parents exempt children from receiving immunizations. The journal of school nursing, 2012. 28(2): p. 153–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Luthy KE, Beckstrand RL, and Meyers CJ, Common perceptions of parents requesting personal exemption from vaccination. The Journal of School Nursing, 2013. 29(2): p. 95–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maertens JA, et al. , Using Community Engagement to Develop a Web-Based Intervention for Latinos about the HPV Vaccine. J Health Commun, 2017. 22(4): p. 285–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McCauley MM, et al. , Exploring the choice to refuse or delay vaccines: a national survey of parents of 6-through 23-month-olds. Academic pediatrics, 2012. 12(5): p. 375–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meleo-Erwin Z, et al. , "To each his own": Discussions of vaccine decision-making in top parenting blogs. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 2017. 13(8): p. 1895–1901.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mendel-Van Alstyne JA, Nowak GJ, and Aikin AL, What is 'confidence' and what could affect it?: A qualitative study of mothers who are hesitant about vaccines. Vaccine, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Middleman AB, Short MB, and Doak JS, Focusing on flu: parent perspectives on school-located immunization programs for influenza vaccine. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics, 2012. 8(10): p. 1395–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miller MK, et al. , Views on human papillomavirus vaccination: a mixed-methods study of urban youth. J Community Health, 2014. 39(5): p. 835–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morales-Campos DY, et al. , Hispanic mothers' and high school girls' perceptions of cervical cancer, human papilloma virus, and the human papilloma virus vaccine. Journal of Adolescent Health, 2013. 52(5, Suppl): p. S69–S75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mullins TL, et al. , Risk perceptions, sexual attitudes, and sexual behavior after HPV vaccination in 11-12 year-old girls. Vaccine, 2015. 33(32): p. 3907–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Niccolai LM, et al. , Parents' views on human papillomavirus vaccination for sexually transmissible infection prevention: a qualitative study. Sex Health, 2014. 11(3): p. 274–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nodulman JA, et al. , Investigating stakeholder attitudes and opinions on school-based human papillomavirus vaccination programs. J Sch Health, 2015. 85(5): p. 289–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Olshen E, et al. , Parental acceptance of the human papillomavirus vaccine. J Adolesc Health 2005. 37(3): p. 248–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Perkins RB, et al. , Attitudes toward HPV vaccination among low-income and minority parents of sons: a qualitative analysis. Clin Pediatr (Phila), 2013. 52(3): p. 231–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Perkins RB, et al. , Missed opportunities for HPV vaccination in adolescent girls: a qualitative study. Pediatrics, 2014. 134(3): p. e666–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Perkins RB, et al. , Why don't adolescents finish the HPV vaccine series? A qualitative study of parents and providers. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 2016. 12(6): p. 1528–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reich JA, Neoliberal mothering and vaccine refusal: imagined gated communities and the privilege of choice. Gender & Society, 2014. 28(5): p. 679–704. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rendle KA and Leskinen EA, Timing Is Everything: Exploring Parental Decisions to Delay HPV Vaccination. Qual Health Res, 2017. 27(9): p. 1380–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Roncancio AM, et al. , Identifying Hispanic mothers' salient beliefs about human papillomavirus vaccine initiation in their adolescent daughters. J Health Psychol, 2019. 24(4): p. 453–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Roncancio AM, et al. , Hispanic mothers' beliefs regarding HPV vaccine series completion in their adolescent daughters. Health Educ Res, 2017. 32(1): p. 96–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Saada A, et al. , Parents' choices and rationales for alternative vaccination schedules: a qualitative study. Clin Pediatr (Phila), 2015. 54(3): p. 236–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sanders Thompson VL, Arnold LD, and Notaro SR, African American parents' HPV vaccination intent and concerns. J Health Care Poor Underserved, 2012. 23(1): p. 290–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schmidt-Grimminger D, et al. , HPV knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs among Northern Plains American Indian adolescents, parents, young adults, and health professionals. J Cancer Educ, 2013. 28(2): p. 357–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Senier L, “It's Your Most Precious Thing ” : Worst - Case Thinking, Trust, and Parental Decision Making about Vaccinations. Sociological Inquiry, 2008. 78(2): p. 207–229. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shui I, et al. , Factors influencing African-American mothers' concerns about immunization safety: a summary of focus group findings. Journal of the National Medical Association, 2005. 97(5): p. 657. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sobo EJ, Social cultivation of vaccine refusal and delay among Waldorf (Steiner) school parents. Medical anthropology quarterly, 2015. 29(3): p. 381–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sobo EJ, et al. , Information Curation among Vaccine Cautious Parents: Web 2.0, Pinterest Thinking, and Pediatric Vaccination Choice. Med Anthropol, 2016. 35(6): p. 529–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sobo EJ, What is herd immunity, and how does it relate to pediatric vaccination uptake? US parent perspectives. Soc Sci Med, 2016. 165: p. 187–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vercruysse J, et al. , Parents' and providers' attitudes toward school-located provision and school-entry requirements for HPV vaccines. Hum Vaccin Immunother, 2016. 12(6): p. 1606–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang E, Baras Y, and Buttenheim AM, "Everybody just wants to do what's best for their child": Understanding how pro-vaccine parents can support a culture of vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine, 2015. 33(48): p. 6703–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Warner EL, et al. , Latino Parents' Perceptions of the HPV Vaccine for Sons and Daughters. J Community Health, 2015. 40(3): p. 387–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wenger OK, et al. , Underimmunization in Ohio's Amish: parental fears are a greater obstacle than access to care. Pediatrics, 2011. 128(1): p. 79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wentzell E, et al. , Factors influencing Mexican women's decisions to vaccinate daughters against HPV in the United States and Mexico. Family & Community Health: The Journal of Health Promotion & Maintenance, 2016. 39(4): p. 310–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Westrick SC, et al. , Parental acceptance of human papillomavirus vaccinations and community pharmacies as vaccination settings: A qualitative study in Alabama. Papillomavirus Res, 2017. 3: p. 24–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wilson T, Factors influencing the immunization status of children in a rural setting. J Pediatr Health Care, 2000. 14(3): p. 117–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wilson R, et al. , Knowledge and acceptability of the HPV vaccine among ethnically diverse black women. Journal of immigrant and minority health, 2013. 15(4): p. 747–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]