Abstract

Objective

To gain an understanding of the variation in available resources and clinical practices between neonatal units (NNUs) in the low-income and middle-income country (LMIC) setting to inform the design of an observational study on the burden of unit-level antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

Design

A web-based survey using a REDCap database was circulated to NNUs participating in the Neonatal AMR research network. The survey included questions about NNU funding structure, size, admission rates, access to supportive therapies, empirical antimicrobial guidelines and period prevalence of neonatal blood culture isolates and their resistance patterns.

Setting

39 NNUs from 12 countries.

Patients

Any neonate admitted to one of the participating NNUs.

Interventions

This was an observational cohort study.

Results

The number of live births per unit ranged from 513 to 27 700 over the 12-month study period, with the number of neonatal cots ranging from 12 to 110. The proportion of preterm admissions <32 weeks ranged from 0% to 19%, and the majority of units (26/39, 66%) use Essential Medicines List ‘Access’ antimicrobials as their first-line treatment in neonatal sepsis. Cephalosporin resistance rates in Gram-negative isolates ranged from 26% to 84%, and carbapenem resistance rates ranged from 0% to 81%. Glycopeptide resistance rates among Gram-positive isolates ranged from 0% to 45%.

Conclusion

AMR is already a significant issue in NNUs worldwide. The apparent burden of AMR in a given NNU in the LMIC setting can be influenced by a range of factors which will vary substantially between NNUs. These variations must be considered when designing interventions to improve neonatal mortality globally.

Keywords: antimicrobial resistance, neonatal sepsis

What is already known on this topic?

The majority of neonatal pathogens in the UK setting are susceptible to antimicrobials used as empirical treatment for neonatal sepsis.

The Delhi Neonatal Infection Study demonstrated high levels of resistance of neonatal pathogens to antimicrobials used as empirical treatment for neonatal sepsis in Delhi.

The prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) Gram-negative infections in neonates is increasing worldwide.

What this study adds?

For the first time, this study describes multinational, multicentre variation in empirical antimicrobial choice for neonatal sepsis, with a focus on low-income and middle-income settings.

This study is the first to describe multinational, multicentre rates of antimicrobial resistance in both Gram-negative and Gram-positive isolates from neonatal units.

This study is the first to show high rates of cephalosporin and carbapenem resistance in isolates, particularly those from Bangladesh and South Africa.

Introduction

Between 2000 and 2015 there was a significant decline in global neonatal mortality, from 36 to 19 per 1000 live births (5.1–2.7 million cases annually).1 This was less pronounced than the reduction seen in childhood (<5 years) mortality, highlighting room for improvement. Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) threatens progress towards this goal.

Laxminarayan et al 2 previously estimated the global AMR population-attributable fraction for neonatal mortality. It was assumed that low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) consistently use a combination of a narrow-spectrum penicillin (benzylpenicillin/ampicillin) and aminoglycoside (gentamicin/amikacin) as empirical therapy for neonatal sepsis (in line with the WHO guidelines), and local resistance rates to either antimicrobial drug could be used as a proxy for risk of mortality attributable to AMR. Mortality rates for AMR neonatal infections were taken from the published literature. Their analysis suggested that 214 000 of 690 000 annual neonatal deaths (31%) associated with sepsis are potentially attributable to AMR. Morbidity and mortality due to AMR have since been added to the Global Burden of Disease Study.3

These estimates are likely to represent an overestimate of mortality attributable to AMR, as blood cultures are usually taken in an inpatient setting where infants are more unwell; it is difficult to accurately estimate mortality from AMR sepsis in the community setting. The limited availability of global microbiological data means that national estimates of resistance may be extrapolated from one or two studies only. Resistance patterns are also known to vary widely between units within cities, particularly when prescribing practices differ substantially.4 These factors illustrate the need for detailed multicountry, patient-level data to better characterise the relationship between AMR and mortality.

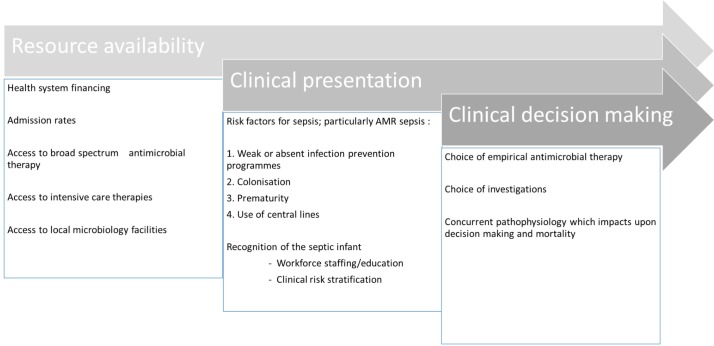

A number of factors may affect the burden of resistant infections in the neonatal setting (figure 1). They can be divided into three broad categories: resource availability, clinical presentation and clinical decision-making.

Figure 1.

Factors affecting the apparent burden of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in the neonatal setting.

The Neonatal AMR research network (NeoAMR) project was established in September 2017. It aims to ‘develop new, globally applicable, empiric antibiotic regimens and strategies for the treatment of neonatal sepsis in settings with varying prevalence of multidrug-resistant pathogens ’.5 These include establishing a global network of neonatal units (NNUs) to design and conduct studies on the optimal use of off-patent antibiotics and other clinical interventions to reduce AMR infection. NNUs should be a mix of neonatal intensive care and special care beds, depending on local demand and resource availability. To facilitate this, a web-based survey was designed to gain an understanding of how the above three factors varied between different settings.

Methods

The NeoAMR web-based survey collected data from 39 NNUs across 12 countries in four continents, with contact made through existing networks. Participating centres were provided with either a PDF (portable document format) copy of the survey or an online link to the REDCap6 database, with questions focused on issues concerning unit capacity, staffing ratios, availability of services, use of antimicrobial guidelines, choice of empirical antimicrobial regimens, local laboratory facilities and antimicrobial susceptibility rates. NNUs also provided information about the total number of positive blood cultures, species isolated and antimicrobial sensitivity testing performed over 12 months. We did not collect data on the rate of culture collection.

The WHO Essential Medicines List (EML) 2017 was revised to include three new categories for antimicrobials—‘Access’, ‘Watch’ and ‘Reserve’, to denote the order (first-line, second-line or last resort) in which antimicrobials should be used to ensure that the appropriate antibiotics are prescribed for a given infection.7 We analysed our results according to these categories.

The survey covered a timeframe of 12 months, where relevant, and data were collected between June and September 2017. All data were anonymised and hosted on a server at St George’s, University of London. All participating sites agreed to the remote hosting of clinical data.

Results

Resource availability

Of the 39 units, 38 were university or teaching hospitals. Twenty-five were publicly funded, or free at the point of access, eight were funded by a mixture of public/private incomes, and six were private, that is, a fee for service was payable by the patient. The 39 units serve a total of 228 580 live births per year, of whom 84 140 babies were admitted (both inborn and outborn) and 37 500 (45%) were born preterm (<37 weeks). Summary statistics for the 39 centres are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Summary statistics for NeoAMR centres (per year)

| Country | Units (n) | Total number of live births/year (inborn) | Total number of admissions/year (inborn and outborn) | Mean number of cots | Mean admissions: cots | WTE nurse:cot ratio | Mean % admissions <37 weeks | Mean % admissions <32 weeks |

| Bangladesh | 3 | 5764 (945–4819) | 5883 (945–2828) | 33 | 60 | 0.5–0.8 | 35 | 13 |

| Brazil | 3 | 4620 (820–3800) | 986 (290–434) | 20 | 20 | 0.1–1.5 | 43 | 17 |

| Cambodia | 1 | 0* | 437 | 12 | 36 | 1.7 | 16 | 0 |

| China | 6 | 38 228 (11 000–14 328) | 14 248 (1632–3700) | 103 | 30 | 0.4–1.3 | 29 | 14 |

| Colombia | 1 | 2478 | 1127 | 41 | 27 | 0.95 | 72 | 17 |

| Greece | 2 | 1657 (529–1128) | 731 (202–529) | 26 | 15 | 0.1–0.8 | 40 | 14 |

| India | 9 | 80 400 (513–27 717) | 513–5503 | 49 | 50 | 0.5–2.0 | 40 | 14 |

| Nigeria | 1 | 1462 | 808 | 32 | 25 | 0.6 | 40 | 17 |

| South Africa | 4 | 40 838 (7850–19 219) | 10 244 (1195–4806) | 110 | 23 | 0.6–1.2 | 72 | 19 |

| Thailand | 6 | 29 005 (1718–9434) | 11 852 (165–4620) | 66 | 40 | 0.5–2.6 | 21 | 3 |

| Uganda | 1 | 23 174 | 6182 | 52 | 119 | 0.4 | 46 | 0 |

| Vietnam | 1 | 0* | 4200 | 90 | 47 | 1.1 | 29 | 10 |

There was only one site for Cambodia, Columbia, Nigeria, Uganda and Vietnam.

*0 denotes circumstances where the neonatal unit was not affiliated with an onsite labour ward and there were no live births on site.

NeoAMR, Neonatal AMR research network; WTE, whole-time equivalent.

Of the 39 units, 35 provided intubation and ventilation routinely (1 provided intubation and ventilation on a non-routine basis, 3 could provide non-invasive ventilation, of which 1 provided non-invasive ventilation on a non-routine basis). Thirty-six centres were capable of providing inotropic support, and 34 had the facilities to provide total parenteral nutrition. Thirty-three centres had routine support from a paediatric surgical team, three centres had non-routine support from a surgical team, and three centres had no access to a paediatric surgical team. Seven units were not associated with a maternity unit on site; the average percentage of preterm admissions <37 weeks was 26%. On this basis, the majority of units would be categorised as level 3 units, as defined by the American Academy of Pediatrics or the British Association of Perinatal Medicine (BAPM).8 On average, each unit had 38 admissions per cot per annum (IQR 22–50); however, the unit in Uganda was an outlier with 119 admissions per cot.

Access to laboratory facilities was good across the network, with blood culturing taking place at all sites apart from Uganda. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was taking place at 31 of 39 sites.

Clinical presentation

The ratio of nurses to cots, as well as the proportion of preterm admissions, determines the workload and influences the ability of medical staff to recognise unwell infants. Table 1 demonstrates that there does not appear to be an association between units with higher nurse to cot ratios and those with higher proportions of preterm admissions. Although we do not have data on the intensity of bed usage (ie, whether they are used in a high-dependency or special care capacity), our data suggest that on average there is approximately one whole-time equivalent nurse employed per cot for the participating units. On average, participating units had on average 0.78 (IQR 0.52–1.25) full-time nurses per cot, and as our data included both intensive care and low dependency beds this would suggest that the 1:1 ratio for intensive care beds recommended by the BAPM8 is being met.

Clinical decision-making

Local or national guidelines for empirical antibiotic use in early-onset sepsis (EOS) or late-onset sepsis (LOS) were available in the majority of centres (29 of 38). Fewer guidelines were available for neonatal meningitis (22 of 38). Of 38 centres, 24 used the WHO-recommended combination of a broad-spectrum penicillin with aminoglycoside (benzylpenicillin/ampicillin with gentamicin/amikacin) as first-line therapy in EOS. Table 2 shows the empirical antibiotic regimens grouped according to the three EML categories. Choice of antimicrobials tended to cluster by geographical region; there was less compliance with WHO guidance overall in Bangladesh, China and India. There was no clear association between the level of preterm admissions and choice of antimicrobial regimen. Seventeen NeoAMR centres listed WHO ‘Reserve’ antibiotics as a choice on their empirical antimicrobial guidelines (for either EOS, LOS or meningitis). This suggests that use of ‘Reserve’ antibiotics is already established in NNUs as empirical therapy. A full list of empirical antibiotic regimens for NeoAMR centres can be found in online supplementary appendix 1.

Table 2.

Empirical antimicrobial regimens, categorised by EML-C group

| Country | EOS | LOS | Meningitis | ||||||

| A | W | R | A | W | R | A | W | R | |

| Bangladesh | 3/3 | 3/3 | 3/3 | ||||||

| Brazil | 3/3 | 3/3 | 1/3 | 2/3 | |||||

| Cambodia | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | ||||||

| China | 5/6 | 1/6 | 3/6 | 3/6 | 4/6 | 2/6 | |||

| Colombia | 1/1 | 100 | 100 | ||||||

| Greece | 2/2 | 2/2 | 1/2 | 1/2 | |||||

| India | 6/9 | 3/9 | 5/9 | 3/9 | 1/9 | 3/9 | 6/9 | ||

| Nigeria | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | ||||||

| South Africa | 4/4 | 2/4 | 2/4 | 3/4 | 1/4 | ||||

| Thailand | 6/6 | 1/6 | 4/6 | 1/6 | 1/6 | 4/6 | 1/6 | ||

| Uganda | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | ||||||

| Vietnam | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | ||||||

A, Access; EML-C, Essential Medicines List for Children; EOS, early-onset sepsis; LOS, late-onset sepsis; R, Reserve; W, Watch.

archdischild-2019-316816supp001.pdf (23KB, pdf)

The majority of centres reserved the use of broader spectrum antibiotics for LOS and meningitis. However, there was significant variation in the use of ‘Watch’ antibiotics in particular. Overall, 43% of empirical antimicrobial regimens consist of ‘Access’ antibiotics, 37% of ‘Watch’ antibiotics and 20% consist of ‘Reserve’ antibiotics. Of intended ‘Reserve’ antibiotic usage, 4% was in EOS, 48% in LOS and 48% in meningitis. The use of Reserve antibiotics in the management of neonatal meningitis was particularly notable in India.

Although we do not have information about the blood culturing rate (ie, we do not know the positivity rate or the yield of pathogens), the ratio of positive blood cultures to admissions ranged from 0.2% (Bangladesh) to 40% (South Africa).

Of the 39 centres, 31 provided results of antimicrobial sensitivity testing for their positive blood cultures. Cephalosporin resistance is found in the majority of Gram-negative isolates, with Bangladeshi and South African centres having the highest rates of carbapenem resistance (table 3). Glycopeptide resistance among Gram-positive isolates is a particular problem in Brazilian and Nigerian centres. Choice of ‘Reserve’ antibiotics for a local empirical antimicrobial guideline was associated with a higher total number of positive blood cultures per admission, suggesting that use of Reserve antibiotics may be guided by local microbiology results rather than as broad-spectrum empirical therapy.

Table 3.

Antimicrobial resistance patterns in the NeoAMR network

| Gram-negative cultures resistant to at least one third-generation cephalosporin, n (%) | Gram-negative cultures resistant to a carbapenem, n (%) | % of Gram-positive cultures resistant to a glycopeptide | |

| Bangladesh | 49/58 (84) | 47/58 (81) | 0/1 (0) |

| Brazil | 17/57 (30) | 5/57 (9) | 0/12 (0) |

| Cambodia | 6/9 (67) | 0/9 (0) | 0/2 (0) |

| China | 78/185 (42) | 13/185 (7) | 0/84 (0) |

| Colombia | 25/42 (60) | 1/42 (2) | 0/50 (0) |

| Greece | 8/13 (62) | 0/13 (0) | 0/1 (0) |

| India | 286/562 (51) | 154/562 (27) | 35/265 (13) |

| Nigeria | 26/36 (72) | 7/36 (19) | 5/11 (45) |

| South Africa | 427/627 (68) | 245/627 (39) | 0/394 (0) |

| Thailand | 12/46 (26) | 10/46 (22) | 0/11 (0) |

NeoAMR, Neonatal AMR research network.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to quantify differences in NNU resource allocation and choice of empirical antimicrobial therapy primarily in LMICs on a global scale, accompanied by AMR patterns of local isolates. There is significant variation in factors affecting neonatal care which will impact on the design of future neonatal sepsis trials, including the ratio of live births to the number of cots available locally, the level of staffing on site, the proportion of preterm admissions, access to a choice of empirical antimicrobial therapies, local blood culture rates and availability of antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

We divided these factors into three categories (figure 1). In the first category, accurate estimation of the admission rate relative to the local birth rate is needed to estimate the incidence of AMR sepsis and ease of access to intensive care support. Choice of empirical antimicrobial regimen may be a reflection of wider access to medicines at a country level. Gestational age is recognised as a particularly significant variable as preterm infants are more vulnerable to infection than term infants.9 Additionally, the unique pharmacokinetic profile of antimicrobials in this population10 may increase the risk of treatment failure. Colonisation by resistant bacteria and previous use of antibiotics are two factors which are used in clinical prediction scores, for example, for vancomycin-resistant enterococcus infection in an adult intensive care unit setting.11

Our data demonstrate the challenges faced when attempting global multicentre neonatal sepsis studies in settings with varied resource availability. Our study did not collect data on the acuity of bed usage, which is a key factor in the relationship between NNU staffing and mortality. There is currently no international standard for neonatal nursing training, although the Council of International Neonatal Nurses is increasingly playing a role in this area. There are also no published international data comparing neonatal nursing staffing ratios in different LMIC settings. The BAPM8 recommends staffing ratios of 1:1 for intensive care beds, 1:2 for high dependency beds and 1:4 for special care baby unit admissions. While a recent systematic review12 found that three of four studies reported correlation between lower neonatal staffing to patient ratios and higher mortality, and a reduction in staffing ratios for intensive care beds has been shown to correlate with increased mortality in a UK setting,13 differences in the definition of staffing and a lack of evidence from an LMIC setting prevent the design of an optimal staffing approach.

When combined with results taken from the Global Antimicrobial Resistance, Prescribing, and Efficacy Among Neonates and Children (GARPEC) database,14 our data confirm that variation in choice of empirical antimicrobial regimens exists, despite the existence of global guidelines. One study of paediatric Gram-negative blood stream infection (BSI) in the Pacific region found that for 309 episodes of BSI, 95 different empirical regimens were prescribed (European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 2018, abstract O0055). Future guidance emerging from a neonatal sepsis study to reduce global mortality from AMR-related sepsis is likely to be regional.

Our data show a worryingly high level of AMR, particularly in Gram-negative species. The findings suggest that particularly in Bangladesh and South Africa, choice of second-line antimicrobial therapy is increasingly limited. The WHO Access, Watch and Reserve (AWaRe) classification system of antimicrobials may be a useful guide to monitor usage of broad-spectrum antimicrobials; however, it is beyond the scope of our study to determine whether use of empirical antimicrobial regimens in particular categories is correlated with local AMR rates.

The total number of blood cultures taken at each site was not known, but the total number of positive cultures was assumed to be a proxy of blood culturing rates. Due to anonymisation of clinical data, we could not differentiate between positive cultures from the same patient or the same clinical episode. The relationship between blood culturing rates, contamination rate and BSI is unclear.15 Use of blood culture positivity with a resistant pathogen as a metric of exposure to AMR presents challenges, as blood culture positivity in neonates is low, even when a serious bacterial infection may be present.16 Underdetection of serious bacterial infection will result in novel interventions to reduce mortality being perceived as less effective in reducing neonatal mortality from AMR sepsis.

Neonatal colonisation status is affected by several factors, including maternal colonisation profile and immune function,17 and is associated with invasive infection by colonising species.18 Colonisation status may change during an inpatient stay on an NNU,19 and the precise relationship between colonisation and serious bacterial infection is not clearly understood, particularly in LMIC settings. The use of mortality as the endpoint in future trials of neonatal sepsis poses diagnostic challenges, as multiple pathologies are common in neonates and the differentiation of deaths with sepsis as opposed to attributable to sepsis will need to be considered. An emphasis on clinical presentations or physiological observations which have a high positive predictive value for blood culture-positive sepsis4 is needed, as well as ensuring that the most common causes of death in the NNU population (eg, respiratory failure, intraventricular haemorrhage, massive pulmonary haemorrhage) are captured in future studies.20 Mortality is also not the only outcome which should be considered. Neurodisability is a potentially preventable consequence of severe sepsis but much more difficult to assess because of the difficulties associated with long-term follow-up.21

Conclusion

Our data provide an important snapshot of how differences in NNU organisation and empirical antibiotic regimens may contribute to different clinical outcomes from AMR sepsis in different country settings. Further work is now required to understand how these differences can be captured in a future observational study designed to clarify how AMR influences neonatal mortality and, ultimately, how its impact can be reduced or prevented.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the following contributors: Professor Bhadresh Vyas (Hospital MP Shah Government Medical College and GG Hospital, Jamnagar, Gujarat), Eyinade Olateju (University of Abuja Teaching Hospital, Gwagwalada), Jolly Nankunda (Mulago Hospital, Kampala), Siriporn Rachakhom (Siriraj Hospital, Thailand), Professor Suely Dornellas do Nascimento (Universidade Federal de São Paulo), Professor Yonghong Yang, Dr Shufeng Tian and Dr Ruizhen Zhao (Shenzhen Children’s Hospital, Shenzhen), Dr Dan Wang and Dr Ying Zhang (Tianjin Children’s Hospital, Tianjin), Dr Ping Wang and Dr Jing Liu (Beijing Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital, Beijing), Dr Ping Zhou and Dr Lijuan Wu (Bao'an Maternal and Child Health Hospital, Jinan University, Shenzhen), Dr Changan Zhao and Dr Xiaoping Mu (Guangdong Women and Children’s Hospital, Guangdong), and Dr Yajuan Wang and Dr Fang Dong (Beijing Children’s Hospital, Beijing).

Footnotes

Contributors: MS and PTH conceived this work. JB designed the survey. JB and GL analysed and interpreted the data. GL wrote a first draft. All other authors contributed equally to collection of data. All authors contributed to critical review of drafts and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership, Geneva.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This was an observational study. No unique patient identifiers were collected, no patient samples were collected and no interventions were performed.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000-15: an updated systematic analysis with implications for the sustainable development goals. Lancet 2016;388:3027–35. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31593-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Laxminarayan R, Matsoso P, Pant S, et al. Access to effective antimicrobials: a worldwide challenge. Lancet 2016;387:168–75. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00474-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hay SI, Rao PC, Dolecek C, et al. Measuring and mapping the global burden of antimicrobial resistance. BMC Med 2018;16:78 10.1186/s12916-018-1073-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Investigators of the Delhi Neonatal Infection Study (DeNIS) collaboration Characterisation and antimicrobial resistance of sepsis pathogens in neonates born in tertiary care centres in Delhi, India: a cohort study. Lancet Glob Health 2016;4:e752–60. 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30148-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. GARDP.org (internet) Global antibiotic research and development partnership, 2018. Available: www.gardp.org/programmes/neonatal-sepsis/ [Accessed 18 Sep 2018].

- 6. REDCap.org (internet) Research electronic data capture, 2018. Available: www.projectredcap.org/about/ [Accessed 18 Sep 2018].

- 7. World Health Organisation 20th essential medicines list (Internet), 2017. Available: www.who.int/medicines/news/2017/20th_essential_med-list/en/ [Accessed 18 Sep 2018].

- 8. British Association of Perinatal Medicine Optimal arrangements for neonatal intensive care units in the UK including guidance on their medical staffing, 2014. Available: www.bapm.org/sites/default/files/files/Optimal%20size%20of%20NICUs%20final%20June%202014.pdf [Accessed 18 Sep 2018].

- 9. Collins A, Weitkamp J-H, Wynn JL. Why are preterm newborns at increased risk of infection? Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2018;103:F391–4. 10.1136/archdischild-2017-313595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fuchs A, Li G, Anker JNvanden, et al. Optimising β -lactam dosing in neonates: a review of pharmacokinetics, drug exposure and pathogens. Curr Pharm Des 2018;23:5805–38. 10.2174/1381612823666170925162143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tacconelli E, Karchmer AW, Yokoe D, et al. Preventing the influx of vancomycin-resistant enterococci into health care institutions, by use of a simple validated prediction rule. Clin Infect Dis 2004;39:964–70. 10.1086/423961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sherenian M, Profit J, Schmidt B, et al. Nurse-to-patient ratios and neonatal outcomes: a brief systematic review. Neonatology 2013;104:179–83. 10.1159/000353458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Watson SI, Arulampalam W, Petrou S, et al. The effects of designation and volume of neonatal care on mortality and morbidity outcomes of very preterm infants in England: retrospective population-based cohort study. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004856 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-004856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gandra S, Mojica N, Klein EY, et al. Trends in antibiotic resistance among major bacterial pathogens isolated from blood cultures tested at a large private laboratory network in India, 2008-2014. Int J Infect Dis 2016;50:75–82. 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Laupland KB, Niven DJ, Pasquill K, et al. Culturing rate and the surveillance of bloodstream infections: a population-based assessment. Clin Microbiol Infect 2018;24:910.e1 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fischer JE. Physicians' ability to diagnose sepsis in newborns and critically ill children. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2005;6(3 Suppl):S120–5. 10.1097/01.PCC.0000161583.34305.A0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Le Doare K, Bellis K, Faal A, et al. SIgA, TGF-β1, IL-10, and TNFα in colostrum are associated with infant group B Streptococcus Colonization. Front Immunol 2017;8:1269 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Russell NJ, Seale AC, O’Sullivan C, et al. Risk of early-onset neonatal group B streptococcal disease with maternal colonization worldwide: systematic review and meta-analyses. Clin Infect Dis 2017;65(suppl_2):S152–S159. 10.1093/cid/cix655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Azarian T, Maraqa NF, Cook RL, et al. Genomic epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a neonatal intensive care unit. PLoS One 2016;11:e0164397 10.1371/journal.pone.0164397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Battin MR, Knight DB, Kuschel CA, et al. Improvement in mortality of very low birthweight infants and the changing pattern of neonatal mortality: the 50-year experience of one perinatal centre. J Paediatr Child Health 2012;48:596–9. 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2012.02425.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kohli-Lynch M, Russell NJ, Seale AC, et al. Neurodevelopmental impairment in children after group B streptococcal disease worldwide: systematic review and meta-analyses. Clin Infect Dis 2017;65(suppl_2):S190–S199. 10.1093/cid/cix663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

archdischild-2019-316816supp001.pdf (23KB, pdf)