Abstract

Background

Dysmenorrhoea is a common gynaecological problem consisting of painful cramps accompanying menstruation, which in the absence of any underlying abnormality is known as primary dysmenorrhoea. Research has shown that women with dysmenorrhoea have high levels of prostaglandins, hormones known to cause cramping abdominal pain. Nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are drugs that act by blocking prostaglandin production. They inhibit the action of cyclooxygenase (COX), an enzyme responsible for the formation of prostaglandins. The COX enzyme exists in two forms, COX‐1 and COX‐2. Traditional NSAIDs are considered 'non‐selective' because they inhibit both COX‐1 and COX‐2 enzymes. More selective NSAIDs that solely target COX‐2 enzymes (COX‐2‐specific inhibitors) were launched in 1999 with the aim of reducing side effects commonly reported in association with NSAIDs, such as indigestion, headaches and drowsiness.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness and safety of NSAIDs in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhoea.

Search methods

We searched the following databases in January 2015: Cochrane Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group Specialised Register, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, November 2014 issue), MEDLINE, EMBASE and Web of Science. We also searched clinical trials registers (ClinicalTrials.gov and ICTRP). We checked the abstracts of major scientific meetings and the reference lists of relevant articles.

Selection criteria

All randomised controlled trial (RCT) comparisons of NSAIDs versus placebo, other NSAIDs or paracetamol, when used to treat primary dysmenorrhoea.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected the studies, assessed their risk of bias and extracted data, calculating odds ratios (ORs) for dichotomous outcomes and mean differences for continuous outcomes, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We used inverse variance methods to combine data. We assessed the overall quality of the evidence using GRADE methods.

Main results

We included 80 randomised controlled trials (5820 women). They compared 20 different NSAIDs (18 non‐selective and two COX‐2‐specific) versus placebo, paracetamol or each other.

NSAIDs versus placebo

Among women with primary dysmenorrhoea, NSAIDs were more effective for pain relief than placebo (OR 4.37, 95% CI 3.76 to 5.09; 35 RCTs, I2 = 53%, low quality evidence). This suggests that if 18% of women taking placebo achieve moderate or excellent pain relief, between 45% and 53% taking NSAIDs will do so.

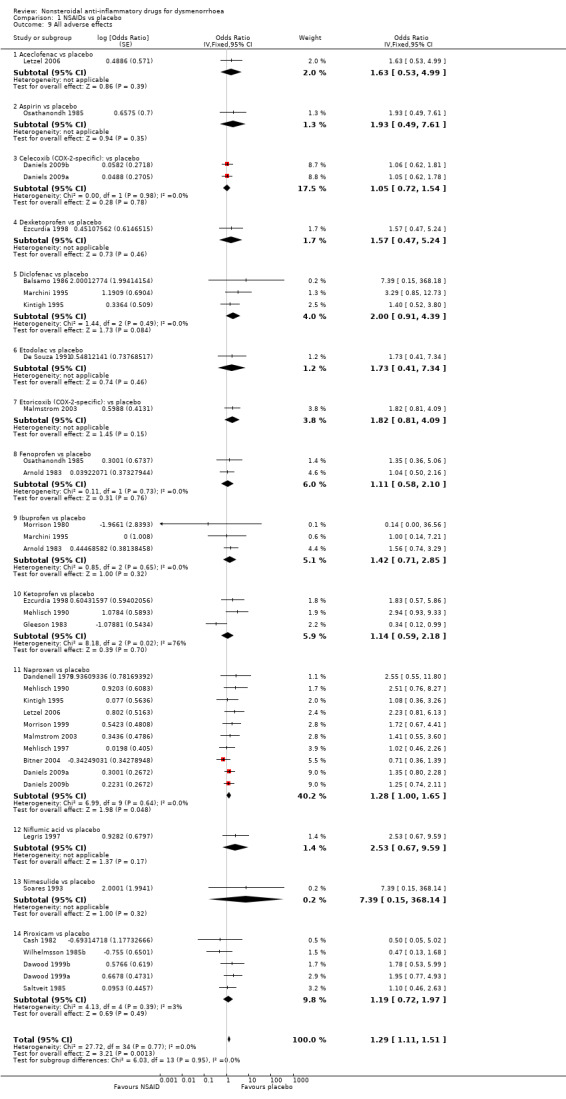

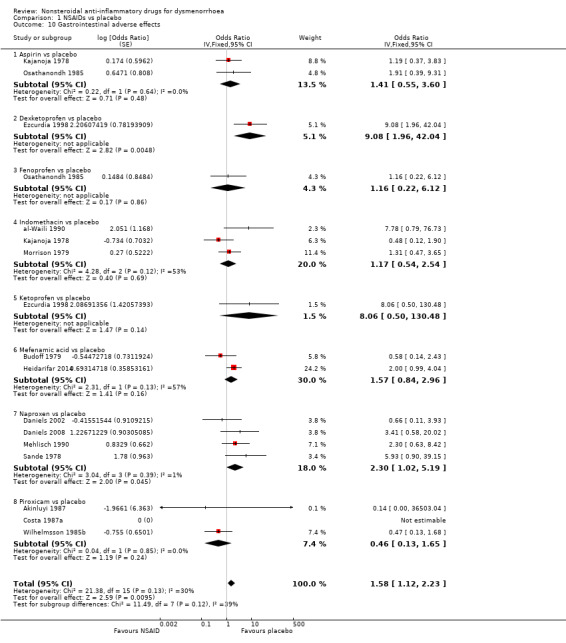

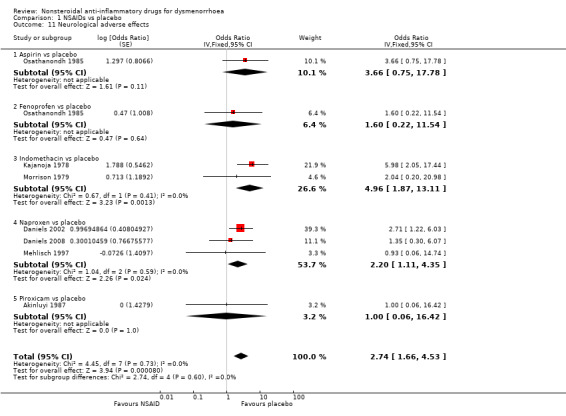

However, NSAIDs were associated with more adverse effects (overall adverse effects: OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.51, 25 RCTs, I2 = 0%, low quality evidence; gastrointestinal adverse effects: OR 1.58, 95% CI 1.12 to 2.23, 14 RCTs, I2 = 30%; neurological adverse effects: OR 2.74, 95% CI 1.66 to 4.53, seven RCTs, I2 = 0%, low quality evidence). The evidence suggests that if 10% of women taking placebo experience side effects, between 11% and 14% of women taking NSAIDs will do so.

NSAIDs versus other NSAIDs

When NSAIDs were compared with each other there was little evidence of the superiority of any individual NSAID for either pain relief or safety. However, the available evidence had little power to detect such differences, as most individual comparisons were based on very few small trials.

Non‐selective NSAIDs versus COX‐2‐specific selectors

Only two of the included studies utilised COX‐2‐specific inhibitors (etoricoxib and celecoxib). There was no evidence that COX‐2‐specific inhibitors were more effective or tolerable for the treatment of dysmenorrhoea than traditional NSAIDs; however data were very scanty.

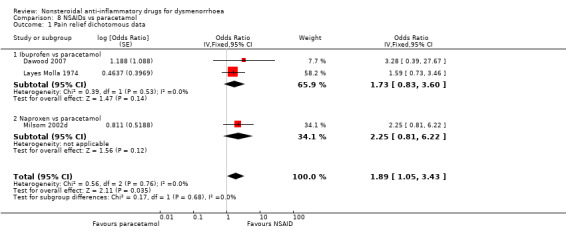

NSAIDs versus paracetamol

NSAIDs appeared to be more effective for pain relief than paracetamol (OR 1.89, 95% CI 1.05 to 3.43, three RCTs, I2 = 0%, low quality evidence). There was no evidence of a difference with regard to adverse effects, though data were very scanty.

Most of the studies were commercially funded (59%); a further 31% failed to state their source of funding.

Authors' conclusions

NSAIDs appear to be a very effective treatment for dysmenorrhoea, though women using them need to be aware of the substantial risk of adverse effects. There is insufficient evidence to determine which (if any) individual NSAID is the safest and most effective for the treatment of dysmenorrhoea. We rated the quality of the evidence as low for most comparisons, mainly due to poor reporting of study methods.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Anti‐Inflammatory Agents, Non‐Steroidal; Anti‐Inflammatory Agents, Non‐Steroidal/adverse effects; Anti‐Inflammatory Agents, Non‐Steroidal/therapeutic use; Cyclooxygenase Inhibitors; Cyclooxygenase Inhibitors/adverse effects; Cyclooxygenase Inhibitors/therapeutic use; Dysmenorrhea; Dysmenorrhea/drug therapy; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs for dysmenorrhoea

Review question

Are nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) safe and effective for relief of period pain (dysmenorrhoea) and how do they compare with each other and with paracetamol?

Background

Nearly three‐quarters of women suffer from period pain or menstrual cramps (dysmenorrhoea). Research has shown that women with severe period pain have high levels of prostaglandins, hormones known to cause cramping abdominal pain. NSAIDs are drugs which act by blocking prostaglandin production. NSAIDs include the common painkillers aspirin, naproxen, ibuprofen and mefenamic acid. Researchers in The Cochrane Collaboration reviewed the evidence about the safety and effectiveness of NSAIDs for period pain. The evidence is current to January 2015.

Study characteristics

We found 80 randomised controlled trials (RCTs), which included a total of 5820 women and compared 20 different types of NSAIDs with placebo (an inactive pill), paracetamol or each other. Most of the studies were commercially funded (59%), and a further 31% did not state their source of funding.

Key results

The review found that NSAIDs appear to be very effective in relieving period pain. The evidence suggests that if 18% of women taking placebo achieve moderate or excellent pain relief, between 45% and 53% taking NSAIDs will do so. NSAIDs appear to work better than paracetamol, but it is unclear whether any one NSAID is safer or more effective than others.

NSAIDs commonly cause adverse effects (side effects), including indigestion, headaches and drowsiness. The evidence suggests that if 10% of women taking placebo experience side effects, between 11% and 14% of women taking NSAIDs will do so.

Based on two studies that made head‐to‐head comparisons, there was no evidence that newer types of NSAID (known as COX‐2‐specific inhibitors) are more effective for the treatment of dysmenorrhoea than traditional NSAIDs (known as non‐selective inhibitors), nor that there is a difference between them with regard to adverse effects.

Quality of the evidence

We rated the quality of the evidence as low for most comparisons, mainly due to poor reporting of study methods.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. NSAIDs compared to placebo for dysmenorrhoea.

| NSAIDs compared to placebo for dysmenorrhoea | ||||||

|

Population: women with primary dysmenorrhoea Setting: Outpatient Intervention: NSAIDs Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of studies | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk4 | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | NSAIDs | |||||

| Pain relief dichotomous data | 180 per 1000 | 490 per 1000 (452 to 528) | OR 4.37 (3.76 to 5.09) | 35 studies | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2,3 | — |

| All adverse effects | 100 per 1000 | 125 per 1000 (110 to 144) | OR 1.29 (1.11 to 1.51) | 25 studies | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | — |

| *The basis for the assumed risk is provided in a footnote. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; NSAID: nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug; OR: odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

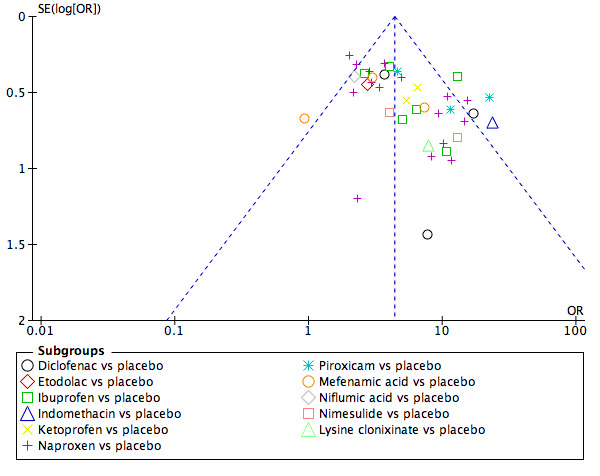

1Very poor reporting of study methods by over 75% of studies; high risk of attrition bias in several studies; over 60% of studies commercially sponsored. 2Substantial heterogeneity (I² = 53%) but direction of effect consistent. 3Some suggestion of publication bias, favouring small studies with positive findings for NSAIDs. 4The control group risks are calculated from median values in 31 studies of pain relief and 19 of adverse effects in a previous version of this review.

Summary of findings 2. NSAIDs compared to paracetamol for dysmenorrhoea.

| NSAIDs compared to paracetamol for dysmenorrhoea | ||||||

|

Population: women with primary dysmenorrhoea Setting: Outpatient Intervention: NSAIDs Comparison: paracetamol | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of studies | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk3 | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Paracetamol | NSAIDs | |||||

| Pain relief dichotomous data | 630 per 1000 | 763 per 1000 (641 to 854) | OR 1.89 (1.05 to 3.43) | 3 studies | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | — |

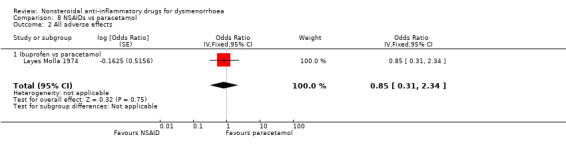

| All adverse effects ‐ ibuprofen versus paracetamol | 130 per 1000 | 113 per 1000 (44 to 259) | OR 0.85 (0.31 to 2.34) | 1 study | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2 | — |

| *The basis for the assumed risk is provided in a footnote. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; NSAID: nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug; OR: odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Poor reporting of study methods in two of the studies; high risk of attrition bias in one study; two of the studies commercially funded. 2One small study, findings compatible with benefit/harm from either intervention, or with no difference between the interventions. 3The control group risk is calculated from the median value in the included studies.

Background

Description of the condition

Dysmenorrhoea refers to the occurrence of painful menstrual cramps of uterine origin, usually developing within hours of the start of menstruation and peaking as the flow becomes heaviest during the first day or two of the cycle. Pain is usually centred in the suprapubic area but may radiate to the back of the legs or lower back, and may be accompanied by other symptoms such as nausea, diarrhoea, headache and lightheadedness (Coco 1999). Dysmenorrhoea is a common gynaecological complaint, though prevalence estimates vary widely. It was reported by 72% of Australian women of reproductive age in a recent nationally representative sample (Pitts 2008), and caused severe pain in 15% of cases. Other representative samples report rates ranging from 17% to 81% (Latthe 2006). In addition to the distress associated with dysmenorrhoea, surveys have shown significant socio‐economic repercussions: over 35% of female high school students report missing school due to menstrual pain (Banikarim 2000; Hillen 1999), and 15% of working Hungarian women of reproductive age reported that painful menstruation limited daily activity (Laszlo 2008).

Dysmenorrhoea is commonly defined within two subcategories. When menstrual pelvic pain is associated with an identifiable pathological condition, such as endometriosis or ovarian cysts, it is termed secondary dysmenorrhoea, while menstrual pain without organic pathology is termed primary dysmenorrhoea (Lichten 1987). The initial onset of primary dysmenorrhoea is usually with the first occurrence of menstruation (menarche), when ovulatory cycles are established, or within the following six to 12 months. The duration of pain is commonly 48 to 72 hours and accompanies menstrual flow or precedes it by only a few hours. In contrast, secondary dysmenorrhoea is more likely to occur years after the onset of menarche and pain can occur both before and during menstruation (Dawood 1984).

The aetiology of primary dysmenorrhoea has been the source of considerable debate. Current understanding is that it is caused by an excessive or imbalanced amount of prostanoids (hormone‐like substances including prostaglandin) released from the endometrium during menstruation. These cause the uterus to contract frequently and dysrhythmically, with reduced local blood flow and hyper sensitisation of the peripheral nerves (Dawood 2006; Dawood 2007). Although most women with dysmenorrhoea have higher levels of prostaglandins F2 alpha and E2 than non‐dysmenorrhoeic women (Pickles 1979), some women with severe dysmenorrhoea and normal laparoscopic findings do not have elevated menstrual prostaglandin to account for the symptoms (Chan 1978). The prevalence of such cases is unknown. It has been suggested that the antidiuretic hormone vasopressin may also be involved in the aetiology of primary dysmenorrhoea, but its role remains controversial (Dawood 2006).

Description of the intervention

Nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are non‐narcotic analgesics. The first drug of this type was aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid), which was introduced in 1899. The term NSAID was first used in the 1950s when phenylbutazone was developed (Hart 1984). Since then NSAIDs have proliferated and many different types are available. NSAIDs inhibit the action of cyclooxygenase (COX), an enzyme responsible for the formation of prostaglandin (and other prostanoids). The COX enzyme exists in two forms, COX‐1 and COX‐2. Traditional NSAIDs are considered 'non‐selective' because they inhibit both COX‐1 and COX‐2 enzymes. The anti‐inflammatory and pain‐relieving effects of NSAIDs are thought to be mainly due to inhibition of COX‐2 enzymes, whereas the side effects (commonly gastrointestinal) appear to be related to the inhibition of COX‐1 enzymes. With the aim of improving the tolerability of NSAIDs, highly selective COX‐2‐specific inhibitors (coxibs) were developed and first launched in 1999. Since then there have been concerns regarding the risk of cardiovascular and/or dermatological adverse events associated with the long‐term use of some coxibs, and some have been withdrawn by manufacturers. There is growing evidence that NSAIDs as a class are associated with some degree of cardiovascular risk when used long‐term, as in the management of chronic pain in the elderly (Shi 2008).

Several other interventions for dysmenorrhoea have been assessed in Cochrane systematic reviews, as follows:

surgical interruption of pelvic nerve pathways (Proctor 2005);

herbal and dietary therapies (Proctor 2001);

spinal manipulation (Proctor 2006);

beta2‐adrenoceptor agonists (Fedorowicz 2012);

Chinese herbal medicine (Zhu 2008);

oral contraceptive pill (Wong 2009);

transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (Proctor 2002);

exercise (Brown 2010);

behavioural interventions (Proctor 2007);

acupuncture (Smith 2011).

How the intervention might work

It is thought that NSAIDs relieve primary dysmenorrhoea mainly by suppressing the production of endometrial prostaglandins, thus alleviating cramps and restoring normal uterine activity. In addition there may be direct analgesic action on the central nervous system (Dawood 2006).

Why it is important to do this review

There is a large body of randomised controlled trials evaluating the short‐term use of NSAIDs for treatment of dysmenorrhoea. A previous systematic review of NSAIDs for dysmenorrhoea considered the four most commonly used types: aspirin, ibuprofen, mefenamic acid and naproxen (Zhang 1998). The purpose of the current review is to compare all nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs used in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhoea with placebo, with paracetamol and with each other to evaluate their effectiveness and safety.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness and safety of NSAIDs in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhoea.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Included

Published and unpublished randomised, controlled, double‐blinded trials using either a parallel‐group or cross‐over design.

Excluded

Trials that failed to include in analysis at least 80% of the women initially randomised, with respect to at least one of the primary outcomes of this review.

Unblinded or single‐blinded trials.

Types of participants

Included

Women of reproductive age with primary dysmenorrhoea.

We included trials where the diagnosis of dysmenorrhoea was not formally assessed with a physical or gynaecological examination provided no clinical indications of pelvic pathology were reported.

Excluded

Studies that reported the inclusion of:

women with secondary dysmenorrhoea (with identified pathology from a physical examination);

women with irregular/infrequent menstrual cycles (outside of the typical range of a 21‐ to 35‐day cycle);

women using an intrauterine contraceptive device (IUCD);

pregnant or breastfeeding women.

Types of interventions

Included comparisons

NSAIDs versus placebo

NSAIDs versus NSAIDs (i.e. comparing one type of NSAID against another type of NSAID)

NSAIDs versus paracetamol

We considered differing doses and routes of administration of NSAIDs (oral and suppository).

We categorised NSAIDs as non‐selective or as COX‐2‐specific inhibitors based on US Food and Drug Administration categories (FDA 2015).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Pain relief ‐ measured with a visual analogue scale (VAS) (i.e. a measure of the amount of pain relief on a 1 to 10 scale) or as dichotomous data (i.e. at least moderate pain relief versus no pain relief).

If other scales or labels were used, we collapsed these (if possible) into dichotomous data, based on the authors' descriptions of the scale, so that women experiencing 'at least moderate' pain relief were reported as having pain relief, whereas women with only mild pain relief were reported as having no pain relief. If pain intensity was reported rather than pain relief we also considered this and recorded it as a separate outcome. We reported continuous data if dichotomous data could not be extracted.

-

Adverse effects:

Total number of adverse effects ('all')

Gastrointestinal adverse effects (for example, nausea, vomiting)

Neurological (nervous system) adverse effects (for example, headache, fatigue, dizziness).

Secondary outcomes

Requirement for additional medication

Interference with daily activities

Absence from work or school

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched for all randomised controlled trials of NSAIDs used to treat dysmenorrhoea, using the search strategy described below and in consultation with the Cochrane Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group (MDSG) Trials Search Co‐ordinator. There was no restriction by language or publication status. It is the intention of the review authors that a new search for RCTs be performed every two years and the review be updated accordingly.

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases, trial registers and websites from inception to 7 January 2015:

Cochrane Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group (MDSG) Specialised Register of controlled trials;

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, November 2014);

MEDLINE;

EMBASE;

PsycINFO;

CINAHL.

We combined the MEDLINE search with the Cochrane highly sensitive search strategy for identifying randomised trials, which appears in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Version 5.1.0 chapter 6, 6.4.11 (Higgins 2011)). We combined the EMBASE, PsycINFO and CINAHL searches with trial filters developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) (http://www.sign.ac.uk/methodology/filters.html#random).

Other electronic sources of trials included:

-

trial registers for ongoing and registered trials:

http://www.clinicaltrials.gov (a service of the US National Institutes of Health);

http://www.who.int/trialsearch/Default.aspx (the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) search portal);

DARE (Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects) in The Cochrane Library at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/cochrane_cldare_articles_fs.html (for reference lists from relevant non‐Cochrane reviews);

Web of Science (another source of trials and conference abstracts) to cross‐link citations of relevant articles;

OpenGrey (http://www.opengrey.eu/) for unpublished literature from Europe;

LILACS database (http://regional.bvsalud.org/php/index.php?lang=en) for trials from the Portuguese and Spanish‐speaking world;

PubMed; and

Google (for recent trials not yet indexed in MEDLINE).

Searching other resources

Wee also searched reference lists of relevant publications, review articles, abstracts of major scientific meetings and included studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

One review author scanned the titles and abstracts of articles retrieved by the search and removed those that were very clearly irrelevant. We retrieved the full text of all potentially eligible studies. Two review authors independently examined the full‐text articles for compliance with the inclusion criteria and selected studies eligible for inclusion in the review. We attempted to contact study investigators as required, to clarify study eligibility (for example, with respect to randomisation). We resolved disagreements as to study eligibility by consensus. We planned to consult a third review author (CF) if there was any ongoing disagreement; however this did not prove necessary.

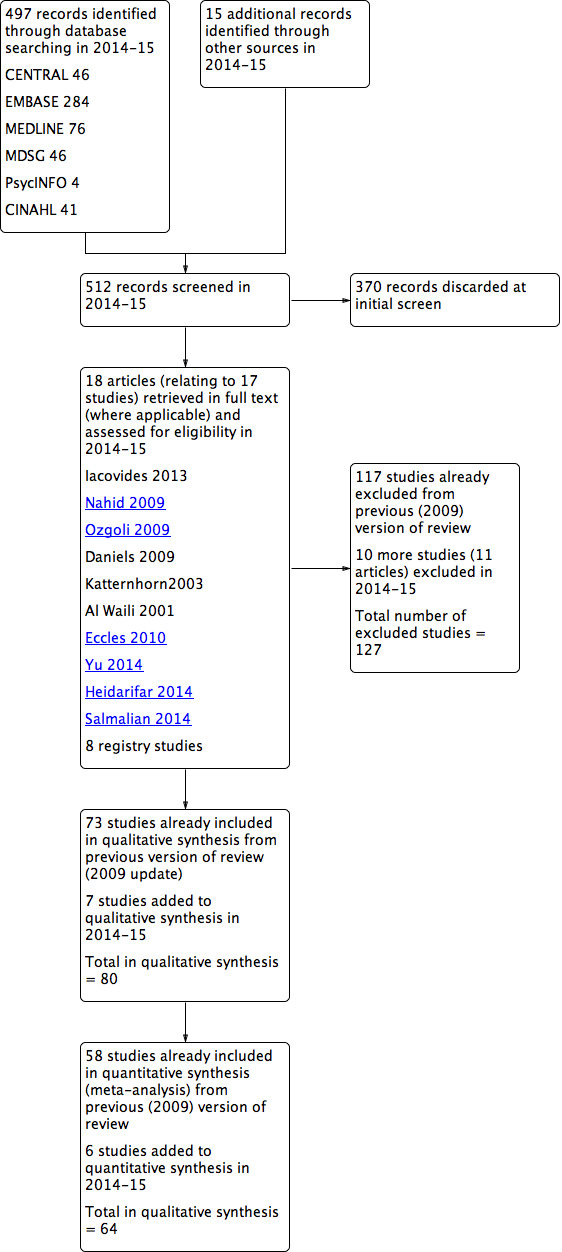

We documented the selection process with a PRISMA flow chart (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

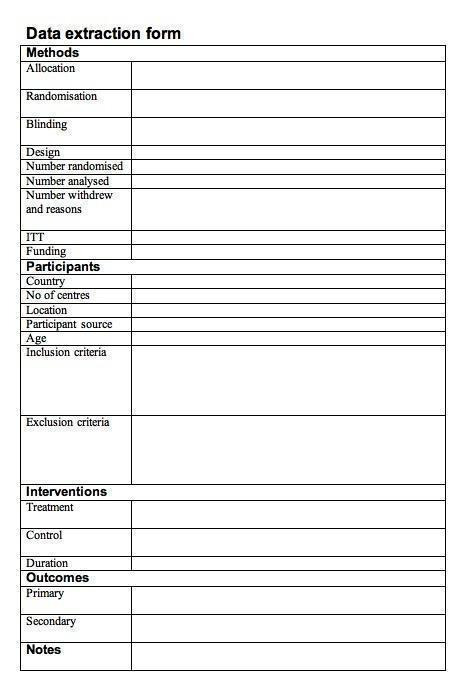

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (JM and either MP or RD) independently extracted data using a standardised form designed by the authors (Figure 2). We resolved discrepancies by discussion. For each study, we extracted data on study design, participants, interventions and outcome measures: these are presented in the Characteristics of included studies table. We also extracted data on study findings: these are presented in the Results and the Data and analyses sections.

2.

Data extraction form

For the first version of this review, we made attempts to contact the authors of 29 trials published since 1985 in order to clarify aspects of methodology or obtain missing data. We received replies from eight authors or co‐authors of these trials. We did not make attempts to contact authors of studies published before 1985 or where no recent address for any of the authors could be found. Where studies had multiple publications, we used the most recent report.

Where studies had multiple publications, we used the main trial report as the reference and derived additional details from secondary papers. The review authors collated multiple reports of the same study, so that each study rather than each report was the unit of interest in the review: such studies are grouped under a single study ID with multiple references.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For this review update, two review authors (CF and JM) independently conducted assessment of risk of bias, using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' assessment tool to evaluate all included studies for the following: adequacy of sequence generation and allocation concealment; adequacy of blinding of women, providers and outcome assessors; completeness of outcome data; risk of selective outcome reporting and risk of other potential sources of bias (Higgins 2011).

Sequence generation

We considered the following methods of random sequence generation adequate:

referring to a random number table;

using a computer random number generator;

coin tossing;

shuffling cards or envelopes;

throwing dice;

drawing of lots.

We deemed the risk of bias low if one of these methods was described. We deemed the risk of bias unclear if the study was described as randomised but the sequence generation method was not described.

Allocation concealment

We considered the following methods of allocation concealment adequate:

central allocation, including telephone, web‐based and pharmacy‐controlled randomisation;

sequentially numbered drug containers of identical appearance;

sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes.

We deemed the risk of bias low if one of these methods was described. We deemed the risk of bias unclear if the study was described as randomised but the method used for allocation concealment was not described.

Blinding

Blinding refers to whether participants and study personnel knew which women were receiving active treatment and which were receiving placebo. We considered blinding adequate if any of the following were described:

blinding of women and (specified) key study personnel, provided it appeared unlikely that the blinding could have been broken;

use of identical placebo;

unblinding of study personnel at the end of the study.

We deemed the risk of bias low if one of these methods was described. We deemed the risk of bias unclear if the study was described as blinded but no further details were reported. As noted above, we excluded studies that were clearly not blinded.

Attrition bias

We considered outcome data as complete if either of the following applied:

all women randomised were analysed;

data were imputed for those missing.

We deemed the risk of bias low if over 95% of randomised women were included in analysis, unclear if 90% to 95% of randomised women were included in analysis and high if less than 90% of randomised women were included in analysis. As noted above, we excluded studies that clearly analysed less than 80% of randomised women for at least one of the primary outcomes.

Selective reporting

We assessed a study as being free of the risk of selective outcome reporting if both the following applied:

the published report included all expected outcomes;

outcomes were reported systematically for all comparison groups, based on prospectively collected data.

We deemed the risk of bias low if both of the criteria were met, unclear if these criteria were not met and high if there was evidence that data had been collected on outcomes of interest but were not reported in the study publication.

Potential bias related to study funding

We assessed a study as being at unclear risk of bias related to study funding if it was commercially sponsored or the source of funding was not reported

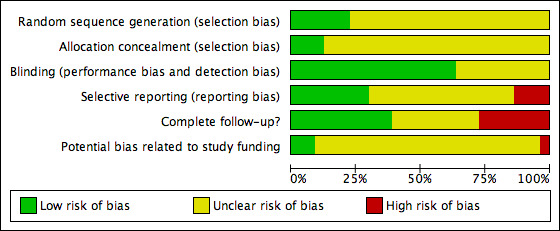

We resolved disagreements by consensus. The results of the assessment of risk of bias are presented in the Characteristics of included studies and in a summary table (Figure 3). We incorporated these results into the interpretation of review findings by means of sensitivity analyses.

3.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous data (e.g. numbers reporting relief of pain), we calculated log odds ratios and their standard errors, and entered these in tables using the generic inverse variance option in RevMan (RevMan 2014), where they were displayed as odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals.

For continuous data (e.g. pain scores), we calculated mean differences and their standard errors and entered these in tables using the generic inverse variance option, where they were displayed as mean differences with 95% confidence intervals.

Unit of analysis issues

Denominator

We only included data reported 'per woman' in meta‐analyses. Where studies reported data only 'per menstrual cycle' we briefly summarised results in an additional table. Where trials compared two NSAIDs against placebo, if possible we evenly divided the placebo group between the two trials to avoid double‐counting in the meta‐analysis. Where the placebo group contained an uneven number of women, we entered the placebo group for both comparisons and performed a sensitivity analysis to examine the effect on pooled findings.

Cross‐over trials

For the 2009 update of this review (and subsequent updates) we made an a priori decision to include data from all phases of cross‐over trials, wherever possible. The strength of a cross‐over design is that variation in repeated responses between women is usually less than that between different women and hence the trials can give more precise results. To exploit this correlation, cross‐over trials should be analysed using a method of analysis specific to paired data. Methods are now available for meta‐analysing cross‐over trials and for combining the summary effect measures of parallel and cross‐over trials. However, to date the reporting of cross‐over trials has been very variable and the data required to include a paired analysis in a meta‐analysis are frequently unreported so that there is insufficient information to apply any one synthesis method consistently (Elbourne 2002).

In this review, where cross‐over trials were analysed using methods suitable for paired data and reported an overall measure of effect and standard error (or where this was calculable), we extracted these data and displayed them alongside data from parallel trials. Where cross‐over trials reported dichotomous data or continuous data analysed using non‐paired methods, we extracted these data as if they derived from parallel trials (i.e. as if they had twice as many women). This method of analysis permits the use of more of the available data but is likely to widen confidence intervals, with the possible consequence of disguising clinically important heterogeneity (differences between the studies). Nevertheless, this incorrect analysis is conservative, in that studies are under‐weighted rather than over‐weighted. We explored the effect of this choice of analysis in sensitivity analyses.

Dealing with missing data

We only included analyses reported in the primary studies that included at least 80% of women in the review.

We analysed data on an intention‐to‐treat basis as far as possible. Where data were missing, we made attempts to obtain them from the original investigators. Where they were unobtainable, we only analysed the available data, based on the numerator and denominator reported in study results or calculable from reported percentages. We explored the effect of excluding studies with more than 10% of data missing in sensitivity analyses.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We considered whether the clinical and methodological characteristics of the included studies were sufficiently similar for meta‐analysis to provide a meaningful summary. Where pooling was conducted, we examined heterogeneity between the results of different studies by inspecting the scatter in the data points and the overlap in their confidence intervals and more formally by checking the results of the Chi2 tests and I2 statistic. We took a P value of less than 0.1 for the Chi2 test to indicate significant heterogeneity and if this was detected, we used the I2 statistic to estimate the percentage of the variability in effect estimates due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error. We took an I2 value greater than 50% to indicate substantial heterogeneity (Higgins 2003; Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

In view of the difficulty in detecting and correcting for publication bias and other reporting biases, we aimed to minimise their potential impact by ensuring a comprehensive search for eligible studies and by being alert for duplication of data. We used a funnel plot to assess the possibility of small study effects (a tendency for estimates of the intervention effect to be more beneficial in smaller studies) for the primary review outcomes. We cautiously considered visible asymmetry in the funnel plot as a possible indication of publication bias.

Data synthesis

We synthesised (combined) the data from primary studies if they were sufficiently homogeneous. We stratified studies by the type of NSAID and comparator used.

For the 2009 update of the review (and subsequent updates including this one in 2015) we made an a priori decision to pool both cross‐over and parallel data using the inverse variance method. We calculated mean differences (MDs) for continuous data and pooled odds ratios for dichotomous data, with 95% confidence intervals. We used both fixed‐effect and random‐effects statistical models. Fixed‐effect models are displayed in the review where data are homogeneous. An increase in the odds of a particular outcome, which may be beneficial (for example, pain relief) or detrimental (for example, an adverse effect), is displayed graphically in the meta‐analyses to the right of the centre‐line and a decrease in the odds of an outcome to the left of the centre‐line.

If it was not possible to extract from a trial report either dichotomous or continuous data suitable for the calculation of ORs or MDs then we reported statistical data in additional tables. Where trial results were presented only as graphs, we described the findings in the text.

We translated the key results into assumed and comparative risks expressed as a percentage. We estimated control group risks for the main comparison from median values in the placebo group in 31 studies of pain relief and 19 of adverse effects in a previous version of this review, and we estimated the corresponding intervention group risk using the formula suggested in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011; Section 11.5.5).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to subgroup studies by the type of NSAID used (non‐selective or COX‐2‐specific inhibitors) if there were sufficient studies in each group that reported the same outcome (for example, three or more studies in each group). However, this was not done as we only included two studies of COX‐2‐selective inhibitors in the review.

Where a visual scan of the forest plots or the results of statistical tests indicated substantial heterogeneity, we explored possible explanations in sensitivity analyses and/or in the text, and we tested the effect of using a random‐effects model.

We planned to conduct subgroup analyses for primary outcomes only.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned sensitivity analyses for the primary review outcomes to determine whether the results were robust to decisions made during the review process.

These analyses excluded the following studies:

studies that did not clearly describe adequate procedures for allocation concealment and blinding;

studies with more than 10% of data missing or imputed for the primary outcomes;

studies with a unit of analysis error (such as those in which cross‐over data were analysed as if they derived from parallel studies);

studies that contributed twice to a pooled analysis: this occurred occasionally where a study contributed more than one comparison to a pooled analysis and either the numerator or the denominator in the placebo group were odd numbers. Where this occurred it was reported in the results for the relevant analysis.

Overall quality of the body of evidence: 'Summary of findings' table

We prepared a 'Summary of findings' table using the Guideline Development Tool software. This table evaluates the overall quality of the body of evidence for the primary review outcomes (pain relief and adverse effects), using GRADE criteria (study limitations (i.e. risk of bias), consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias). We incorporated judgements about evidence quality (high, moderate or low) into the reporting of results for each primary outcome.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The search completed in January 2015 retrieved 497 records, of which we discarded 370 as clearly ineligible. We retrieved 18 articles for further assessment regarding their eligibility, 10 from databases (for which we obtained the full text) and eight from trial registers. JM and RA independently checked these 18 articles for eligibility.

Out of these 18 articles, we newly included seven studies in the current (2015) update and we newly excluded 10 studies (11 articles). This gives a total of 80 included studies (seven newly included in 2015, plus 73 from the previous version of the review) and 127 excluded (10 newly excluded in 2015, plus 117 from the previous version of the review). See Figure 1.

Included studies

Trial design and setting

The review includes 80 RCTs, 24 of parallel design and 56 of cross‐over design. They randomised a total of 5820 women, 2372 in parallel studies and 3448 in cross‐over studies. Sample size in the parallel trials ranged from 17 to 410; seven randomised over 100 women. Sample size in the cross‐over trials ranged from 11 to 198.

The studies were conducted in the USA (n = 26 trials), Sweden (n = 9), Italy (n = 6), the UK (n = 5), Brazil, Finland, Mexico (n = 4 each), Iran, Norway, South Africa (n = 3 each), Canada, Nigeria, Spain (n = 2 each), Argentina, China, Colombia, Denmark, France, Germany and Iraq (n = 1 each). The majority were published in English, although five were in Spanish, four in Portuguese and one each in French, Italian and Norwegian. Trials were translated as required by members of The Cochrane Collaboration.

Participants

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the majority of included studies were quite explicit. All but three of the trials stated clearly either that they included only women with primary dysmenorrhoea, or that women with secondary dysmenorrhoea were excluded. The other three studies had less specific inclusion criteria that did not define dysmenorrhoea (Akerlund 1989; Pauls 1978), or included both primary and secondary dysmenorrhoea but reported results separately (Sahin 2003). The diagnosis of primary dysmenorrhoea was confirmed by a physical or gynaecological examination in 40 of the included studies. Oral contraceptive use was an exclusion criterion in most of the studies, and other common exclusion criteria were pelvic disease, intrauterine device (IUD) use, irregular menstrual cycles, renal or hepatic disorders, contraindications to nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs, pregnancy, planned pregnancy and use of hormonal preparations, analgesics or other medications that could interfere with the proposed comparisons.

Most studies detailed the demographic characteristics of the women. Their mean age ranged from 15.8 to 32.2 years (where stated).

Interventions

Included comparisons eligible for the review were as follows:

NSAID versus placebo: 56 trials;

NSAID versus NSAID: 17 trials;

NSAID versus NSAID versus placebo: four trials;

NSAID versus paracetamol: one trial;

NSAID versus paracetamol versus placebo: two trials.

Eighteen different types of non‐selective NSAIDs were evaluated in the included studies: aceclofenac, aspirin, dexketoprofen, diclofenac, etodolac, fenoprofen, flufenamic acid, flurbiprofen, ibuprofen, indomethacin, ketoprofen, lysine clonixinate, mefenamic acid, meloxicam, naproxen, niflumic acid, nimesulide and piroxicam.

Only two types of COX‐2‐specific NSAIDs were evaluated: celecoxib and etoricoxib. Several of the included studies reported data on comparison arms receiving interventions not relevant to this review (e.g. NSAIDs that have been withdrawn by the manufacturers, mild opiate analgesics as a comparison, herbal interventions); we excluded such data from analysis.

Doses of NSAIDs varied, but fell within commonly recommended parameters. Average doses for non‐selective NSAIDs were as follows: aceclofenac (100 mg daily), aspirin (650 mg; four‐hourly), dexketoprofen (12.5 mg to 25 mg; six‐hourly), diclofenac (up to 200 mg daily in divided doses, orally or by suppository), etodolac (200 mg to 300 mg twice daily), fenoprofen (100 mg to 200 mg; four‐hourly), fentiazac (100 mg; twice daily), flufenamic acid (200 mg; eight‐hourly), flurbiprofen (100 mg; twice daily), ibuprofen (400 mg; three, four or six times daily), indomethacin (25 mg tablets or 100 mg suppositories; three times daily), ketoprofen (25 mg to 50 mg; six‐hourly, with or without a loading dose of 25 mg to 70 mg), lysine clonixinate (125 mg; six‐hourly); meclofenamate sodium (100 mg; eight‐hourly), mefenamic acid (250 mg; eight‐hourly), meloxicam (7.5 mg to 15 mg; daily), daily naproxen/naproxen sodium (250 mg to 275 mg; four to eight‐hourly, sometimes with a loading dose of 500 mg to 550 mg), niflumic acid (250 mg; three times daily), nimesulide (50 mg to 100 mg twice daily), piroxicam (20 to 40 mg daily, by tablet or suppository) and tolfenamic acid (200 mg; eight‐hourly). Doses of COX‐2‐specific inhibitors used were: celecoxib: 400 mg then 200 mg 12‐hourly and etoricoxib 120 mg daily.

The duration of treatment in the included studies varied from one cycle (per treatment) to five. For details of the drug regimes used in individual studies, see the Characteristics of included studies table.

Outcomes

Outcomes measures varied. Most studies measured pain relief by asking women to keep a daily record during their menstrual period, rating their degree of pain relief on an ordinal scale, either categorical (e.g. from poor to excellent) or numerical (e.g. 1 to 5), while others used a dichotomous measure (e.g. complete relief/ongoing pain). Some women were asked to rate their pain intensity on various types of continuous numerical scale: few studies used a visual analogue scale. In most cases pain relief was reported as the proportion of women experiencing relief, though some trials instead used the number of menstrual cycles as the denominator. Interference with daily activities and absence from work/school were generally measured as the proportion of women reporting any degree of interference with their normal routine or any need for days off. About a quarter of the trials clearly reported that they measured adverse effects by prospective self report, using a questionnaire, record card or diary in which the women noted any symptoms daily during their menstrual period. Others assessed this outcome retrospectively at follow‐up appointments, by either specific or non‐specific questioning or simply by recording information volunteered by the participant. Many trials did not specify how they measured adverse effects.

Excluded studies

In total we excluded 127 trials from the review, for the following reasons:

35 trials did not mention randomisation, included non‐randomised women in analysis, or their design was unclear and attempts to contact authors for clarification were unsuccessful;

14 trials were randomised but had only single blinding or no blinding at all;

12 trials included NSAIDs that are currently discontinued (for the treatment of dysmenorrhoea) and did not report data on any other relevant comparison;

19 trials included women who had secondary dysmenorrhoea (including IUCD‐related dysmenorrhoea), menorrhagia or eumenorrhoea;

three trials measured uterine pressure or contractibility rather than pain relief;

13 trials did not include a comparison of interest;

five trials were dose‐finding trials of a single NSAID;

26 trials had participant withdrawal rates of 20% or more.

See Characteristics of excluded studies for more information.

Risk of bias in included studies

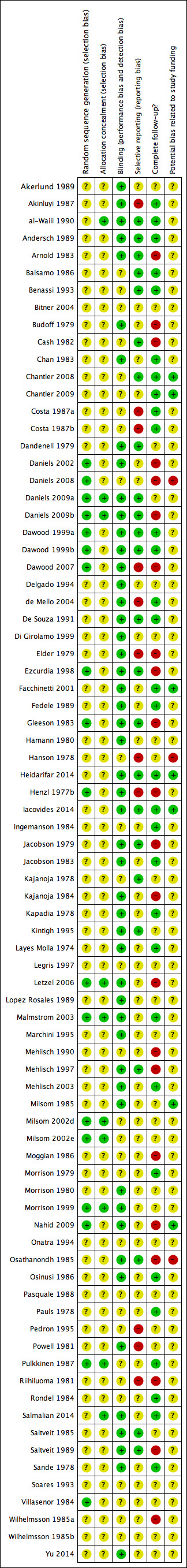

The quality of the included studies is summarised in Figure 4.

4.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Allocation

All studies stated that they were randomised, but only 23% (18/80) described in detail their method of generating a random allocation sequence. We rated these studies as at low risk of bias, while we rated all the other studies as at unclear risk.

Less than 12% of studies (9/80) described an adequate method of allocation concealment. We rated these studies as at low risk of bias, while we rated all the other studies as at unclear risk.

Blinding

All studies were described as double‐blinded, and 50 studies (50/80: 63%) provided details of who was blinded or stated explicitly that the placebo was identical to the active treatment. Given the subjective nature of the pain‐related outcomes assessed in this review, inadequate blinding has a high potential to bias results. We rated the other 30 studies as at unclear risk of bias.

Incomplete outcome data

None of the included studies clearly analysed fewer than 80% of women randomised.

Thirty‐one of the studies (39%) included over 95% of women randomised in analysis for one of our primary outcomes. We rated these as at low risk of attrition bias. Twenty‐seven studies (34%) included 90% to 95% of women in analysis and we rated them as at unclear risk of bias, while the other 22 studies included fewer than 90% of women in analysis, and we rated them as at high risk of bias.

The main reasons for incomplete outcome data (where stated) were as follows: failure to attend follow‐up appointments, poor compliance with the study criteria, and withdrawal from treatment due to adverse effects, pregnancy, lack of efficacy, or wish to use contraceptives such as the oral contraceptive pill (OCP) or IUCD that were excluded by the trial criteria. Losses to follow‐up are likely to be associated with treatment inefficacy or adverse effects, and so have a high potential to bias results.

Selective reporting

Only 24/80 studies (30%) clearly appeared to be free of selective reporting. In most studies (44/80; 55%) it was unclear whether data on adverse effects were collected prospectively. We rated nine studies as at high risk of selective reporting bias because adverse events were not reported as an outcome or it was clear that they were reported selectively. The impact of selective reporting of harms on the pooled result is not obvious, as selective emphasis of those adverse events where analyses were statistically significant might overstate those harms, and selective omission might attenuate the estimated effect (see Characteristics of included studies).

Potential bias related to study funding

Seven studies (7/80; 9%) reported a non‐commercial source of funding and we rated them as at low risk of potential bias related to study funding. We rated the other studies as at unclear risk of such bias: 47/80 studies (59%) were co‐authored or funded by pharmaceutical companies and 25/80(31%) did not mention their source of funding.

Glossary

Please refer to the Cochrane glossary for explanation of unfamiliar terms: http://community.cochrane.org/glossary.

Effects of interventions

Pain relief

1) Nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) versus placebo

There were 47 trials comparing NSAIDs versus placebo from which data on pain relief could be extracted, which were suitable for meta‐analysis. They compared the following NSAIDs versus placebo: aspirin (one study), celecoxib (two studies), diclofenac (three studies), etodolac (one study), etoricoxib (one study), fenoprofen (two studies), flufenamic acid (one study), ibuprofen (six studies), indomethacin (three studies), ketoprofen (two studies), lysine clonixinate (one study), mefenamic acid (four studies), meloxicam (one study), naproxen (21 studies), niflumic acid (one study) and nimesulide (two studies); some trials included more than one comparison. The studies analysed a total of 2602 women, 2006 women in cross‐over trials and 596 women in parallel trials.

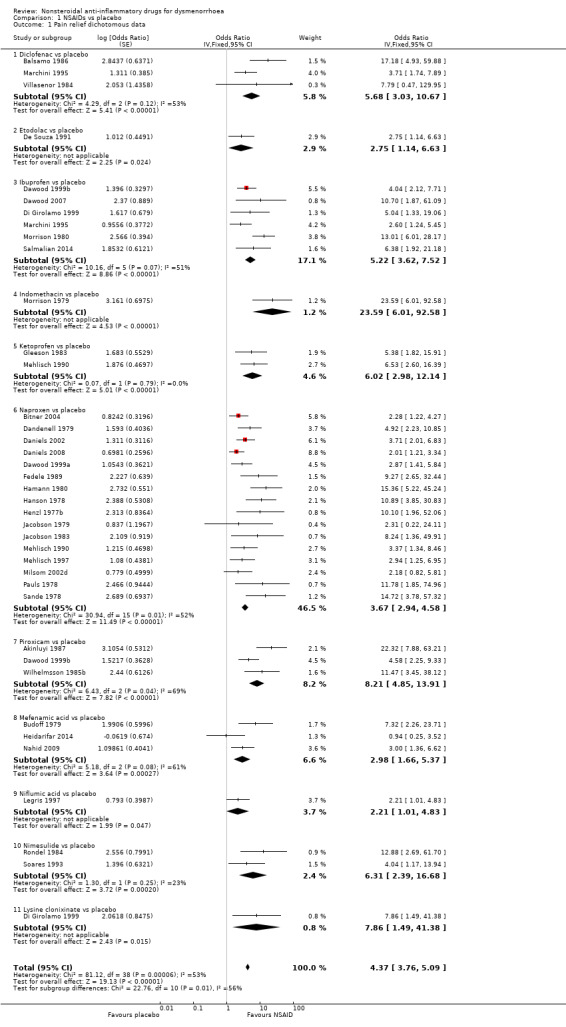

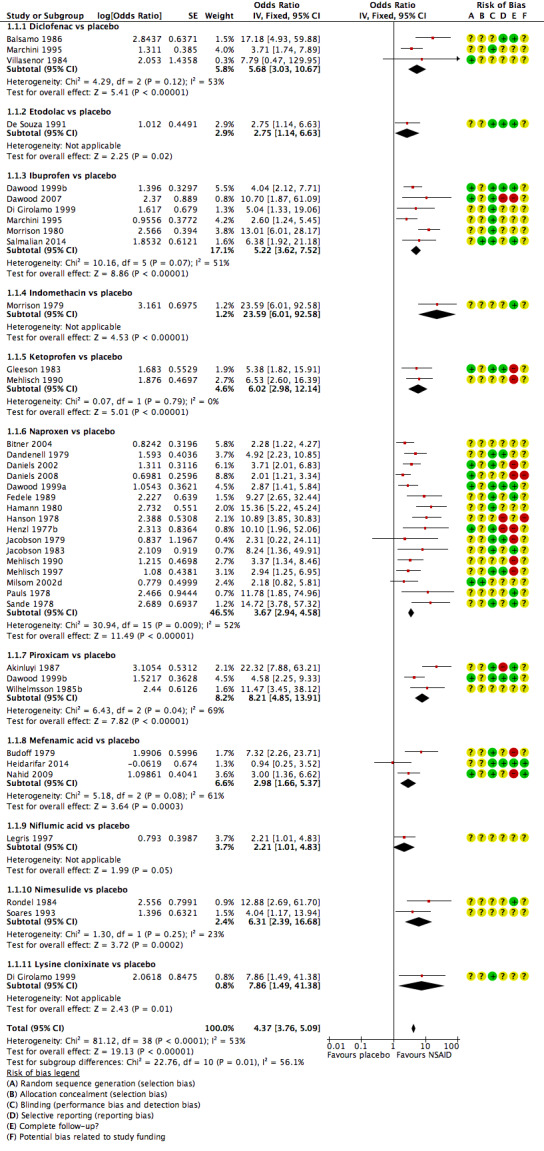

When we pooled dichotomous data from 35 studies comparing all NSAIDs versus placebo, NSAIDs were more effective than placebo at producing moderate or excellent pain relief (odds ratio (OR) 4.37, 95% confidence interval (CI) 3.76 to 5.09; I2 = 53%) (Analysis 1.1; Figure 5). Effect sizes varied, with few studies and wide confidence intervals for most comparisons. The most precise finding was for naproxen (OR 3.67, 95% CI 2.94 to 4.58; 16 studies, I2 = 52%). The placebo groups in three studies contributed twice to the pooled analysis of all NSAIDs, but sensitivity analyses excluding these studies did not materially affect the results (Di Girolamo 1999; Marchini 1995; Mehlisch 1990). Heterogeneity in these analyses is discussed below.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs vs placebo, Outcome 1 Pain relief dichotomous data.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 NSAIDs vs placebo, outcome: 1.1 Pain relief dichotomous data.

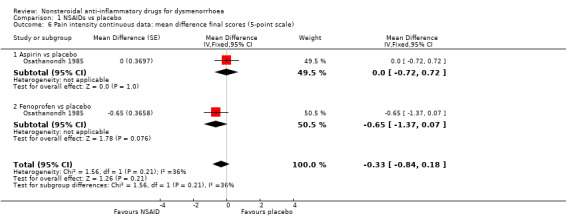

Among 12 studies reporting continuous data for this outcome, only two used visual analogue scales (VAS). The other 10 studies compared seven different NSAIDs versus placebo, using five different pain scales. We combined the studies that used common scales, as an attempt to pool scales (and calculate the standardised mean difference (SMD)) resulted in high levels of heterogeneity. In most analyses NSAIDs were more effective than placebo in producing moderate/excellent pain relief and/or in reducing pain scores. The only NSAIDs without clear indication of benefit were aspirin and fenoprofen, which were tested in a single study each (Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs vs placebo, Outcome 6 Pain intensity continuous data: mean difference final scores (5‐point scale).

Effect estimates for continuous outcomes of effectiveness were as follows:

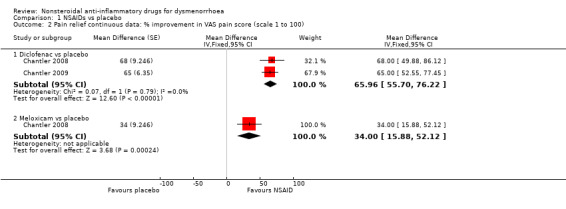

Diclofenac versus placebo (difference in improvement on a 0 to 100 VAS): mean difference (MD) 65.96, 95% CI 55.70 to 76.22, two studies, I2 = 0% (Analysis 1.2).

Meloxicam versus placebo (difference in improvement on a 0 to 100 VAS): MD 34, 95% CI 15.88 to 52.12, one study (Analysis 1.2).

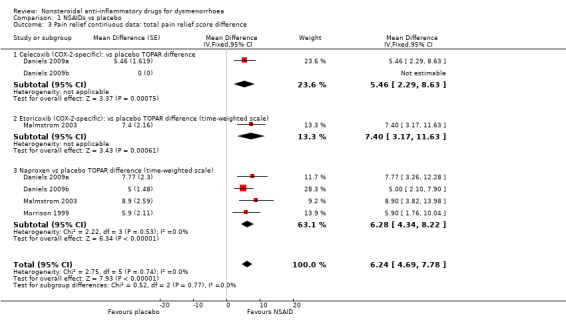

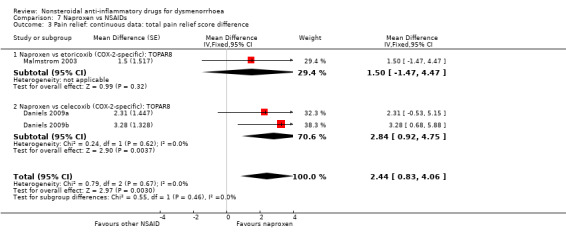

Celecoxib, etoricoxib or naproxen versus placebo (mean difference in total pain relief using a time‐weighted scale (TOPAR)): MD 6.24, 95% CI 4.69 to 7.78, four studies, I2 = 0% (Analysis 1.3).

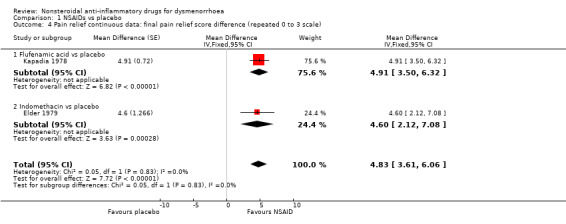

Flufenamic acid or indomethacin versus placebo (difference in final score on a repeated 0 to 3 scale): MD 4.83, 95% CI 3.61 to 6.06, two studies, I2 = 0% (Analysis 1.4).

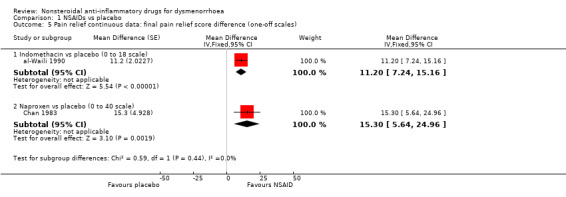

Indomethacin versus placebo (difference in final score on a 0 to 18 scale): MD 11.20, 95% CI 7.24 to 15.16, one study (Analysis 1.5).

Naproxen versus placebo (difference in final score on a 0 to 40 scale): MD 15.30, 95% CI 5.64 to 24.96, one study (Analysis 1.5).

Aspirin or fenoprofen versus placebo (difference in pain intensity on a 0 to 4‐point scale): MD ‐0.33, 95% CI ‐0.84 to 0.18, two studies, I2 = 36% (Analysis 1.6).

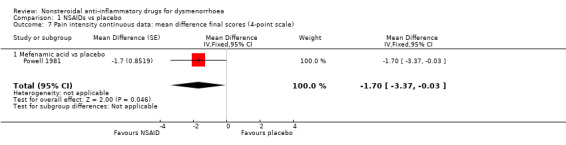

Mefenamic acid versus placebo (difference in pain intensity on a 1 to 4 scale): MD ‐1.70, 95% CI ‐3.37 to ‐0.03 (Analysis 1.7).

Naproxen versus placebo (difference in final score on a 0 to 40 scale): MD 15.30, 95% CI 5.64 to 24.96, one study (Analysis 1.5).

Aspirin or fenoprofen versus placebo (difference in pain intensity on a 0 to 4‐point scale): MD ‐0.33, 95% CI ‐0.84 to 0.18, two studies, I2 = 36% (Analysis 1.6).

Mefenamic acid versus placebo (difference in pain intensity on a 1 to 4 scale): MD ‐1.70, 95% CI ‐3.37 to ‐0.03 (Analysis 1.7).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs vs placebo, Outcome 2 Pain relief continuous data: % improvement in VAS pain score (scale 1 to 100).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs vs placebo, Outcome 3 Pain relief continuous data: total pain relief score difference.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs vs placebo, Outcome 4 Pain relief continuous data: final pain relief score difference (repeated 0 to 3 scale).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs vs placebo, Outcome 5 Pain relief continuous data: final pain relief score difference (one‐off scales).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs vs placebo, Outcome 7 Pain intensity continuous data: mean difference final scores (4‐point scale).

A further 16 trials reported results on this outcome in a form from which no data suitable for meta‐analysis could be extracted, such as graphs (Arnold 1983; Cash 1982; Costa 1987a; Iacovides 2014; Kintigh 1995; Letzel 2006), as continuous data without standard deviations (Moggian 1986; Pasquale 1988; Saltveit 1985), without denominators for each group (Ezcurdia 1998; Osinusi 1986), or as per‐cycle data (Kajanoja 1978; Mehlisch 2003; Pulkkinen 1987; Riihiluoma 1981; see Table 3) or as medians (Nahid 2009; see Table 4). They compared the following NSAIDs versus placebo: aspirin, diclofenac, fenoprofen, ibuprofen, indomethacin, mefenamic acid, naproxen, nimesulide and piroxicam. All NSAIDs were more effective than placebo, apart from aspirin, for which there was no evidence of a difference from placebo (Kajanoja 1978).

1. Pain relief: NSAIDs versus placebo (per cycle data).

| Comparison | Study ID | No of women | Outcome measure | NSAID | Placebo | Significance |

| Aspirin versus placebo | Kajanoja 1978 | 47 | No of cycles where treatment gave moderate/good relief | 13/89 | 9/90 | Not statistically significant |

| Indomethacin versus placebo | Kajanoja 1978 | 37 | No of cycles when women reported moderate/good relief | 42/90 | 9/90 | P value < 0.001 |

| Nimesulide versus placebo | Pulkkinen 1987 | 14 | No of cycles where women rated therapy good/very effective | 22/28 | 9/27 | P value < 0.01 |

| Diclofenac versus placebo | Riihiluoma 1981 | 35 | No of cycles when pain much improved | 14/58 | 3/57 | P value < 0.05 |

NSAID = nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug

2. Pain relief: NSAIDs versus placebo: median data.

| Comparison | Study | No of women | Outcome measure | NSAID group | Placebo group | P value | Finding |

| Mefenamic acid versus placebo | Nahid 2009 | 120 (106 analysed) | Pain score: median (range) on 1 to 10 VAS |

n = 55 At 2 months: 3.6 (2 to 6) At 3 months: 2.4 (1 to 5) |

n = 51 At 2 months: 5 (2 to 6) At 3 months: 6 (4 to 7) |

P value < 0.1) | Favours NSAID |

NSAID = nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug

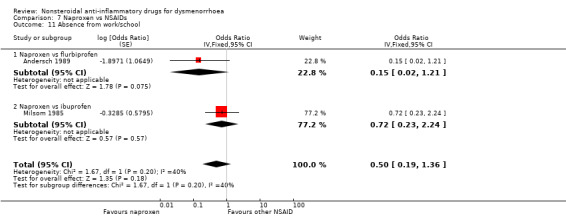

2) NSAIDs versus NSAIDs

There were 18 studies comparing NSAIDs head‐to‐head from which data suitable for meta‐analysis could be extracted, only two of which compared the same two NSAIDs (Daniels 2009a; Daniels 2009b). They made the following comparisons: aspirin versus fenoprofen (Analysis 2.1); diclofenac versus the following: meloxicam (Analysis 6.2), ibuprofen and nimesulide (Analysis 6.1); ibuprofen versus the following: piroxicam, etoricoxib and lysine clonixinate (Analysis 4.1), mefenamic acid versus the following: meloxicam (Analysis 5.1) and tolfenamic acid; and naproxen versus the following: celecoxib (two studies), diclofenac, ketoprofen, etoricoxib, flurbiprofen, ibuprofen and piroxicam (Analysis 7.1 to Analysis 7.5).

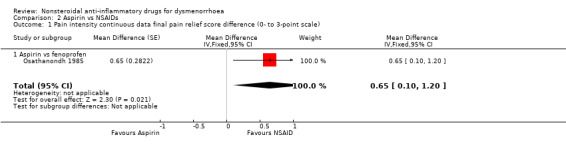

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Aspirin vs NSAIDs, Outcome 1 Pain intensity continuous data final pain relief score difference (0‐ to 3‐point scale).

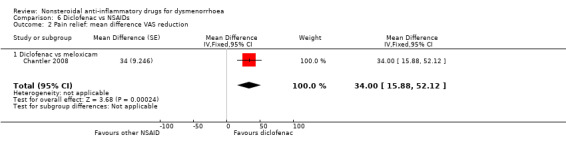

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Diclofenac vs NSAIDs, Outcome 2 Pain relief: mean difference VAS reduction.

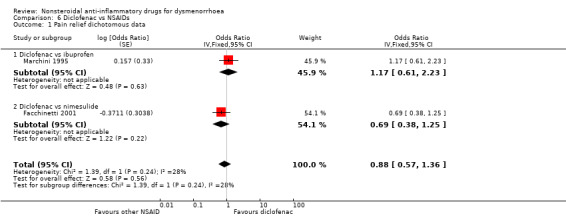

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Diclofenac vs NSAIDs, Outcome 1 Pain relief dichotomous data.

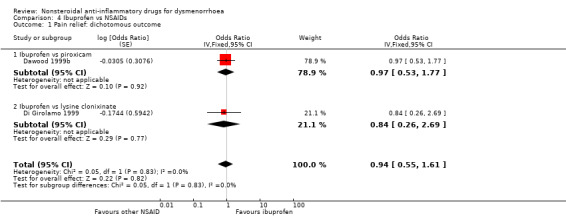

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Ibuprofen vs NSAIDs, Outcome 1 Pain relief: dichotomous outcome.

5.1. Analysis.

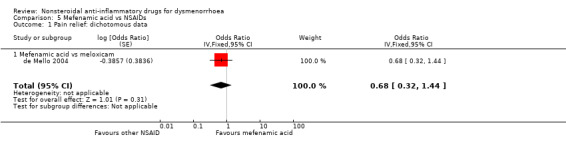

Comparison 5 Mefenamic acid vs NSAIDs, Outcome 1 Pain relief: dichotomous data.

7.1. Analysis.

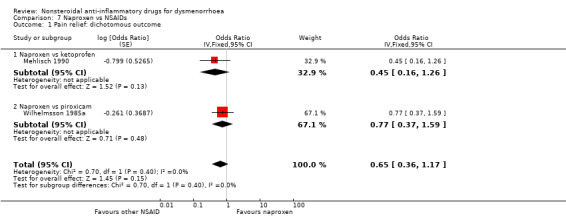

Comparison 7 Naproxen vs NSAIDs, Outcome 1 Pain relief: dichotomous outcome.

7.5. Analysis.

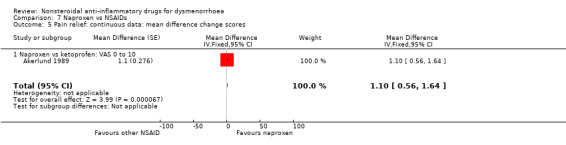

Comparison 7 Naproxen vs NSAIDs, Outcome 5 Pain relief: continuous data: mean difference change scores.

In single studies, diclofenac reduced pain on a visual analogue 100‐point scale more than meloxicam (Analysis 6.2), fenoprofen reduced pain intensity more than aspirin (Analysis 2.1) and etoricoxib was more likely to achieve pain relief than ibuprofen (Analysis 4.2). Naproxen reduced pain scores more than ibuprofen or celecoxib (Analysis 7.3) and was more likely to achieve effective pain relief than ketoprofen (Analysis 7.5). Other head‐to‐head comparisons between NSAIDs showed no evidence of a difference between them.

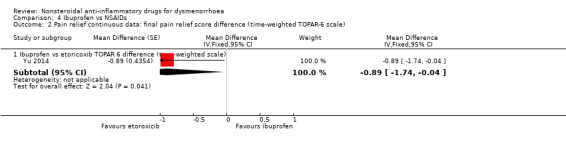

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Ibuprofen vs NSAIDs, Outcome 2 Pain relief continuous data: final pain relief score difference (time‐weighted TOPAR‐6 scale).

7.3. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Naproxen vs NSAIDs, Outcome 3 Pain relief: continuous data: total pain relief score difference.

Effect estimates for all these comparisons were as follows:

Aspirin versus fenoprofen (difference in pain intensity on a 0 to 3‐point scale): MD 0.65, 95% CI 0.10 to 1.20, one study (Analysis 2.1).

Ibuprofen versus piroxicam or lysine clonixinate (rate of pain relief): OR 0.94, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.61 (Analysis 4.1).

Ibuprofen versus etoricoxib (TOPAR 6): MD ‐0.89, 95% CI ‐1.74 to ‐0.04, one study (Analysis 4.2).

Mefenamic acid versus meloxicam (rate of pain relief): OR 0.68, 95% CI 0.32 to 1.44, one study (Analysis 5.1).

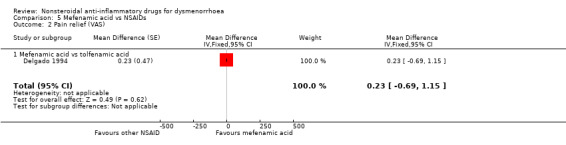

Mefenamic acid versus tolfenamic acid (10‐point VAS): MD 0.23, 95% CI ‐0.69 to 1.15, one study (Analysis 5.2).

Diclofenac versus ibuprofen or nimesulide (rate of pain relief): OR 0.88, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.36, two studies, I2 = 28% (Analysis 6.1).

Diclofenac versus meloxicam (reduction on 100‐point VAS): MD 34, 95% CI 15.88 to 52.12 (Analysis 6.2).

Naproxen versus ketoprofen or piroxicam (rate of pain relief): OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.17, two studies, I2 = 0% (Analysis 7.1).

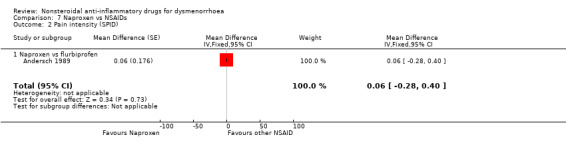

Naproxen versus flurbiprofen (sum of pain intensity difference over time: SPID): MD 0.06, 95% CI ‐0.28 to 0.40, one study (Analysis 7.2).

Naproxen versus etoricoxib or celecoxib (mean difference on total pain relief using a time‐weighted scale (TOPAR8)): MD 2.44, 95% CI 0.83 to 4.06, two studies, I2 = 0% (Analysis 7.3).

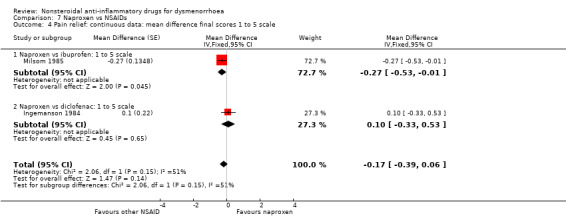

Naproxen versus ibuprofen or diclofenac (mean difference final score on a 1 to 5 scale): MD ‐0.17, 95% CI ‐0.39 to 0.06, two studies, I2 = 51% (Analysis 7.4).

Naproxen versus ketoprofen (difference in change scores on a 10‐point VAS): MD 1.10, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.64, one study (Analysis 7.5).

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Mefenamic acid vs NSAIDs, Outcome 2 Pain relief (VAS).

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Naproxen vs NSAIDs, Outcome 2 Pain intensity (SPID).

7.4. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Naproxen vs NSAIDs, Outcome 4 Pain relief: continuous data: mean difference final scores 1 to 5 scale.

Two additional studies reported only per‐cycle data. One found indomethacin more effective than aspirin (Kajanoja 1978), and one found no evidence of a difference between naproxen and diflunisal (Kajanoja 1984) (Table 5). Twelve trials reported results on this outcome in such a way that no numerical data could be extracted. Some presented graphs (Arnold 1983; Benassi 1993; Costa 1987a; Costa 1987b; Kintigh 1995; Pedron 1995), or continuous data without standard deviations (Pasquale 1988; Saltveit 1989), while one did not provide denominators for each group (Onatra 1994). Only three of these trials reported differences between different NSAIDs: one trial found meclofenamate sodium more effective than naproxen (Benassi 1993), and two trials found piroxicam more effective than naproxen (Costa 1987a; Costa 1987b). However, these trials were very small (with 30, 12 and 14 women respectively) and much larger studies comparing piroxicam with naproxen found no evidence of a difference between them (Saltveit 1989; Wilhelmsson 1985a).

3. Pain relief: NSAIDs versus NSAIDs (per cycle data).

| NSAID 1 | NSAID 2 | Study ID | No of women | Outcome measure | NSAID 1 | NSAID 2 | Significance |

| Aspirin | Indomethacin | Kajanoja 1978 | 47 | No of cycles where treatment gave moderate/good relief | 13/89 | 42/90 | P value < 0.001 |

| Naproxen | Diflunisal | Kajanoja 1984 | 22 (19 analysed) | No of cycles where treatment achieved moderate/good relief | 34/38 | 28/38 cycles | Not statistically significant |

NSAID = nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug

3) NSAIDs versus paracetamol

Two studies compared ibuprofen versus paracetamol and one compared naproxen versus paracetamol. Pooling of these three studies resulted in a difference in the proportion of women reporting good, excellent or complete pain relief, favouring NSAIDs over paracetamol (OR 1.89, 95% CI 1.05 to 3.43) (Analysis 8.1).

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 NSAIDs vs paracetamol, Outcome 1 Pain relief dichotomous data.

Adverse effects

1) NSAIDs versus placebo

All adverse effects

Twenty‐five studies were suitable for meta‐analysis for this outcome. They analysed 2133 women, 1272 in cross‐over studies and 861 in parallel‐group studies. They compared the following NSAIDs versus placebo: naproxen (10 studies), piroxicam (five studies), diclofenac, ibuprofen, ketoprofen (three studies each), celecoxib, fenoprofen (two studies each), aceclofenac, aspirin, dexketoprofen, etodolac, etoricoxib and niflumic acid and nimesulide (one study each).

Although there was no evidence of a difference between any individual NSAID and placebo for this outcome, when we pooled results NSAIDs overall were more likely to cause an adverse effect of any kind than placebo (OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.51, 25 studies, I2 = 0%) (Analysis 1.9). The most commonly reported adverse effects were mild neurological and gastrointestinal symptoms. The placebo groups in two studies contributed twice to the pooled analysis of all NSAIDs, but exclusion of these studies did not materially affect the results (Daniels 2009a; Daniels 2009b).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs vs placebo, Outcome 9 All adverse effects.

Two additional cross‐over studies measured this outcome. One stated that no adverse events were reported in association with either diclofenac or placebo (Iacovides 2014); the other reported that no serious side effects occurred in association with either piroxicam or placebo (Osinusi 1986).

Gastrointestinal adverse effects

Fourteen studies were suitable for meta‐analysis for this outcome, which included adverse effects such as nausea and indigestion. They analysed a total of 702 women, 548 in cross‐over studies and 154 in parallel‐group studies, and compared the following NSAIDs versus placebo: naproxen (four studies), indomethacin, piroxicam (three studies), aspirin, mefenamic acid (two studies each), dexketoprofen, fenoprofen and ketoprofen (one study each). When we pooled all studies, gastrointestinal events were more common in the NSAIDs group (OR 1.58, 95% CI 1.12 to 2.23) (Analysis 1.10). A higher incidence of gastrointestinal side effects was associated with two individual NSAIDs: naproxen (OR 2.30, 95% CI 1.02 to 5.19, four studies, I2 = 1%) and dexketoprofen (OR 8.06, 95% CI 0.50 to 130.48). One additional study reported no events in either the piroxicam or the placebo arm (Costa 1987a).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs vs placebo, Outcome 10 Gastrointestinal adverse effects.

Neurological adverse effects

Seven studies were suitable for meta‐analysis for this outcome, which included adverse effects such as headache, drowsiness, dizziness and dryness of the mouth. They analysed a total of 498 women, 381 in cross‐over studies and 117 in parallel‐group studies, and compared the following NSAIDs versus placebo: naproxen (three studies), indomethacin (two studies) aspirin and fenoprofen (one study each). When we pooled studies NSAIDs were more likely than placebo to cause neurological adverse effects (OR 2.74, 95% CI 1.66 to 4.53, seven studies, I2 = 0%) (Analysis 1.11). Two individual NSAIDs were associated with a higher incidence of events than placebo: naproxen (OR 2.20, 95% CI 1.11 to 4.35, three studies, I2 = 0%) and indomethacin (4.96, 95% CI 1.87 to 13.11, two studies, I2 = 0%).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs vs placebo, Outcome 11 Neurological adverse effects.

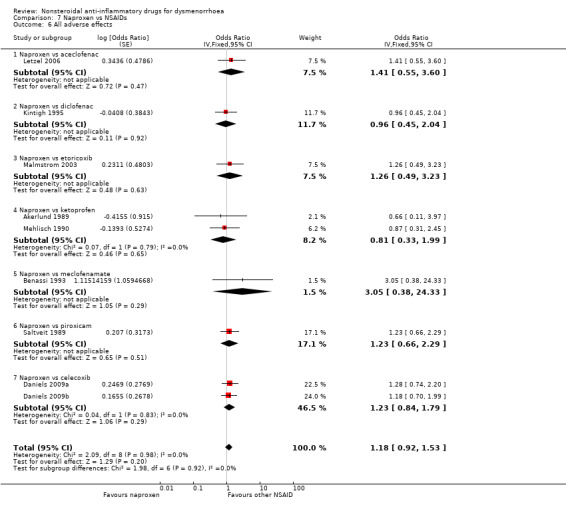

2) NSAIDs versus NSAIDs

All adverse effects

Fifteen studies reported data suitable for meta‐analysis comparing NSAIDs head‐to‐head for this outcome. Only two compared the same two NSAIDs (Daniels 2009a; Daniels 2009b). They analysed data for 1762 women, 959 in cross‐over studies and 803 in parallel studies. They made the following comparisons: aspirin versus fenoprofen, diclofenac versus ibuprofen, etodolac versus piroxicam, ibuprofen versus fenoprofen, ibuprofen versus etoricoxib, mefenamic acid versus tolfenamic acid, and naproxen versus the following: aceclofenac, celecoxib (two studies), diclofenac, etoricoxib, ketoprofen, meclofenamate and piroxicam. When we pooled data for the six studies comparing naproxen versus other NSAIDs we found no evidence of a difference between the groups (Analysis 7.6). Nor did we find any evidence of a difference between the groups in any individual study comparing any NSAIDs head‐to‐head. Two studies not included in meta‐analysis also reported this outcome: one found no evidence of a difference between naproxen and flurbiprofen for the incidence of any adverse effect. The second, comparing diclofenac versus meloxicam, reported no adverse effects in either group (Chantler 2008).

7.6. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Naproxen vs NSAIDs, Outcome 6 All adverse effects.

Effect estimates were as follows

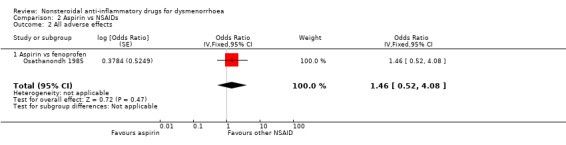

Aspirin versus fenoprofen: OR 1.46, 95% CI 0.52 to 4.08, one study (Analysis 2.2).

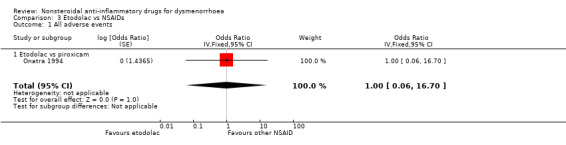

Etodolac versus piroxicam: OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.06 to 16.70, one study (Analysis 3.1).

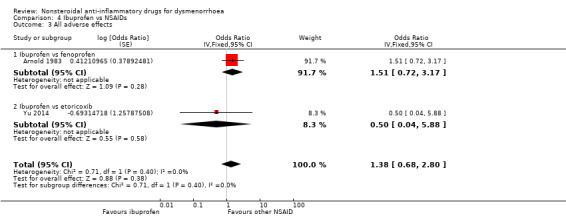

Ibuprofen versus fenoprofen or etoricoxib: OR 1.38, 95% CI 0.68 to 2.80, two studies, I2 = 0% (Analysis 4.3).

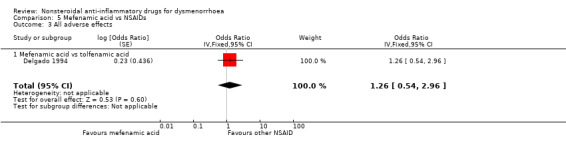

Mefenamic acid versus tolfenamic acid: OR 1.26, 95% CI 0.54 to 2.96, one study (Analysis 5.3).

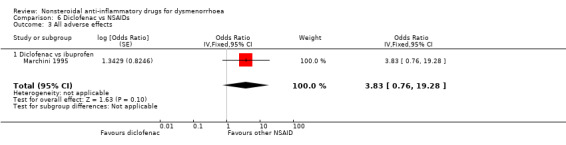

Diclofenac versus ibuprofen: OR 3.83, 95% CI 0.76 to 19.28, one study (Analysis 6.3).

Naproxen versus aceclofenac, diclofenac, etoricoxib, ketoprofen, meclofenamate, piroxicam or celecoxib: OR 1.18, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.53, nine studies, I2 = 0% (Analysis 7.6).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Aspirin vs NSAIDs, Outcome 2 All adverse effects.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Etodolac vs NSAIDs, Outcome 1 All adverse events.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Ibuprofen vs NSAIDs, Outcome 3 All adverse effects.

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Mefenamic acid vs NSAIDs, Outcome 3 All adverse effects.

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Diclofenac vs NSAIDs, Outcome 3 All adverse effects.

Gastrointestinal adverse effects

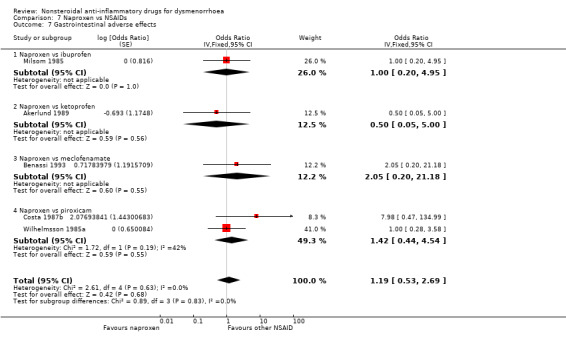

Eight studies reported data suitable for meta‐analysis comparing NSAIDs head‐to‐head for gastrointestinal adverse effects such as nausea and indigestion. Two studies compared the same two NSAIDs but the rest compared different NSAIDs. These studies analysed data for 595 women, 176 in cross‐over studies and 419 in parallel‐group studies. They made the following comparisons: aspirin versus fenoprofen, diclofenac versus nimesulide, and naproxen versus the following: ibuprofen, ketoprofen, meclofenamate (each one study) and piroxicam (two studies). When we pooled data for the four studies comparing naproxen with other NSAIDs there was no evidence of a difference between the groups (Analysis 7.7). Nor did any individual study comparing any NSAIDs head‐to‐head find evidence of a difference between the groups for this outcome.

7.7. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Naproxen vs NSAIDs, Outcome 7 Gastrointestinal adverse effects.

Effect estimates were as follows:

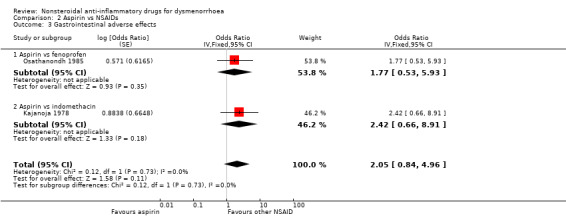

Aspirin versus fenoprofen: OR 2.05, 95% CI 0.84 to 4.96, one study (Analysis 2.3).

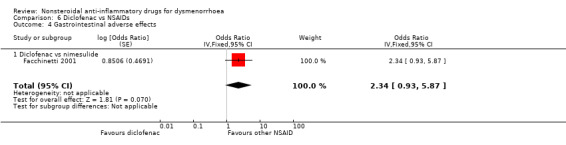

Diclofenac versus nimesulide: OR 2.34, 95% CI 0.93 to 5.87, one study (Analysis 6.4).

Naproxen versus ibuprofen, ketoprofen, meclofenamate or piroxicam: OR 1.19, 95% CI 0.53 to 2.69, five studies, I2 = 0% (Analysis 7.7).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Aspirin vs NSAIDs, Outcome 3 Gastrointestinal adverse effects.

6.4. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Diclofenac vs NSAIDs, Outcome 4 Gastrointestinal adverse effects.

Neurological adverse effects

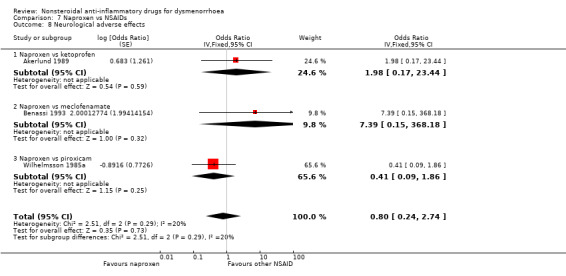

Five studies reported data suitable for meta‐analysis comparing NSAIDs head‐to‐head for neurological adverse effects such as headache, drowsiness and dizziness. No studies compared the same two NSAIDs. These studies analysed data for 527 women, 108 in cross‐over studies and 419 in parallel‐group studies. They made the following comparisons: aspirin versus fenoprofen, diclofenac versus nimesulide, and naproxen versus ketoprofen, meclofenamate and piroxicam. When we pooled data for the three studies comparing naproxen versus other NSAIDs there was no evidence of a difference between the groups (Analysis 7.8). Nor did any individual study comparing any NSAIDs head‐to‐head find evidence of a difference between the groups for this outcome.

7.8. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Naproxen vs NSAIDs, Outcome 8 Neurological adverse effects.

Effect estimates were as follows:

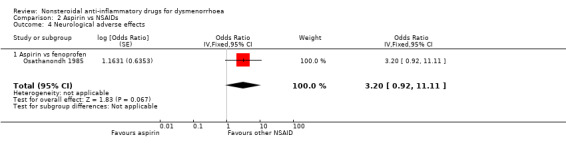

Aspirin versus fenoprofen: OR 3.20, 95% CI 0.92 to 11.11, one study (Analysis 2.4).

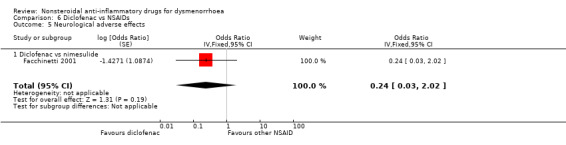

Diclofenac versus nimesulide: OR 0.24, 95% CI 0.03 to 2.02, one study (Analysis 6.5).

Naproxen versus ketoprofen, meclofenamate or piroxicam: OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.24 to 2.74, three studies, I2 = 20% (Analysis 7.8).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Aspirin vs NSAIDs, Outcome 4 Neurological adverse effects.

6.5. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Diclofenac vs NSAIDs, Outcome 5 Neurological adverse effects.

3) NSAIDs versus paracetamol

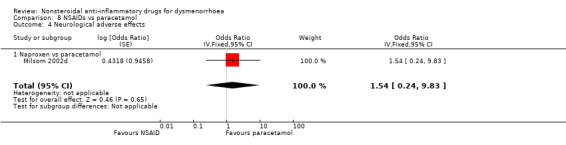

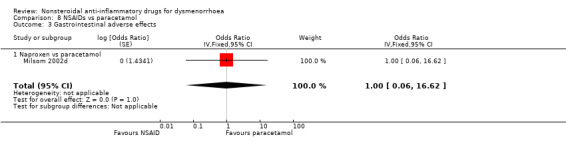

Only three studies reported data suitable for meta‐analysis for this outcome (Analysis 8.2 to Analysis 8.4). No evidence of a difference was found between NSAIDs versus paracetamol in the risk of all adverse effects, or gastrointestinal or neurological adverse effects. However, there was only one study for each comparison.

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 NSAIDs vs paracetamol, Outcome 2 All adverse effects.

8.4. Analysis.

Comparison 8 NSAIDs vs paracetamol, Outcome 4 Neurological adverse effects.

Effect estimates were as follows:

All adverse effects: ibuprofen versus paracetamol: OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.31 to 2.34, one study (Analysis 8.2).

Gastrointestinal adverse effects: naproxen versus paracetamol: OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.06 to 16.62, one study (Analysis 8.3).

Neurological adverse effects: naproxen versus paracetamol: OR 1.54, 95% CI 0.24 to 9.83, one study (Analysis 8.4).

8.3. Analysis.

Comparison 8 NSAIDs vs paracetamol, Outcome 3 Gastrointestinal adverse effects.

Requirement for additional medication

1. NSAIDs versus placebo

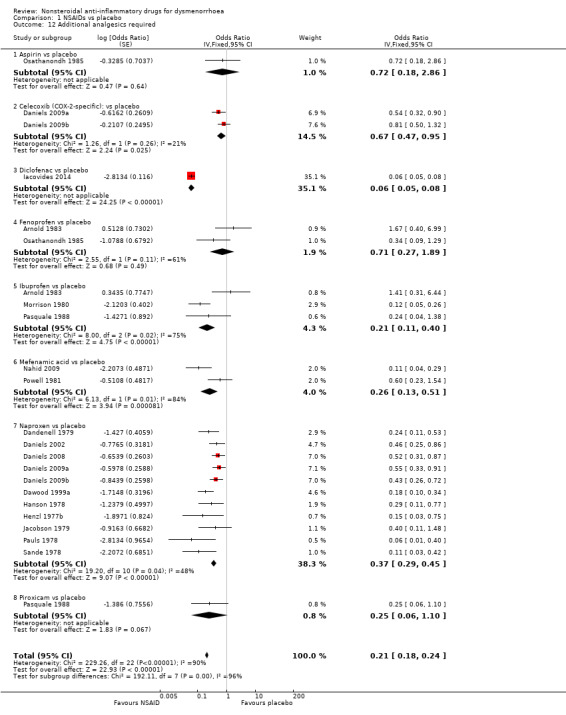

Eighteen studies were suitable for meta‐analysis for this outcome. These studies analysed data for 1283 women, 702 in cross‐over studies and 581 in parallel‐group studies.They compared the following NSAIDs versus placebo: naproxen (11 studies), ibuprofen (three studies), fenoprofen, celecoxib (two studies each), aspirin, diclofenac, piroxicam and mefenamic acid (one study each). Among individual NSAIDs, there was evidence (versus placebo) favouring naproxen (OR 0.37, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.45, 11 studies, I2 = 48%,), ibuprofen (OR 0.21, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.40, three studies, I2 = 75%), celecoxib (OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.95, two studies, I2 = 21%), mefenamic acid (OR 0.48, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.92, two studies, I2 = 0%) and diclofenac (OR 0.06, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.08, one study, 24 women) (Analysis 1.12). There was no evidence of a difference between other individual NSAIDs and placebo.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs vs placebo, Outcome 12 Additional analgesics required.

When we pooled data for this outcome, there was high heterogeneity (I2 = 98%). This appeared to relate mainly to a small study in which there were no events in the NSAID (diclofenac) arm (Iacovides 2014). When we omitted this study from analysis, pooling of the data showed a lower rate of requirement for additional medication in the women in the NSAIDs group, and heterogeneity was reduced (OR 0.42, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.50, 17 studies, I2 = 55%). The placebo groups in two cross‐over studies contributed twice to the pooled analysis but exclusion of these studies did not materially affect the results (Daniels 2009a; Daniels 2009b).

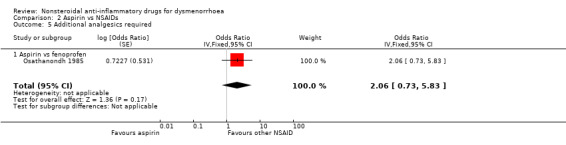

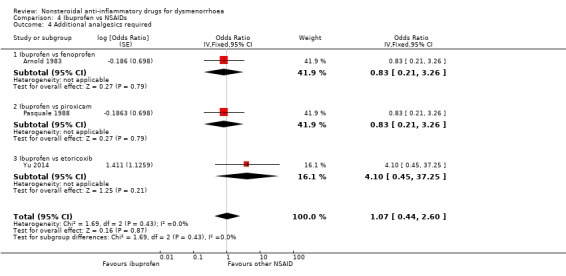

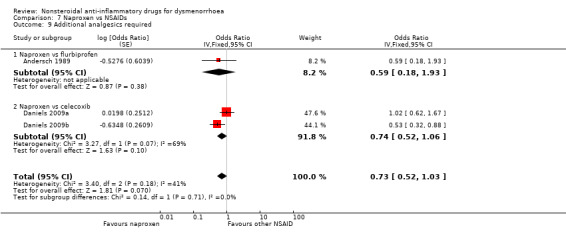

2) NSAIDs versus NSAIDs

Seven studies reported data suitable for meta‐analysis for this outcome. Only two compared the same two NSAIDs (Daniels 2009a; Daniels 2009b). They analysed data for 805 women, 458 in cross‐over studies and 347 in parallel‐group studies. They made the following comparisons: aspirin versus fenoprofen, ibuprofen versus piroxicam, ibuprofen versus fenoprofen, ibuprofen verus etoricoxib, naproxen versus celecoxib (two studies) and naproxen versus flurbiprofen. There was no evidence of a difference between any of the NSAIDs compared (Analysis 2.5; Analysis 4.4; Analysis 7.9).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Aspirin vs NSAIDs, Outcome 5 Additional analgesics required.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Ibuprofen vs NSAIDs, Outcome 4 Additional analgesics required.

7.9. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Naproxen vs NSAIDs, Outcome 9 Additional analgesics required.

3) NSAIDs versus paracetamol

No data were available.

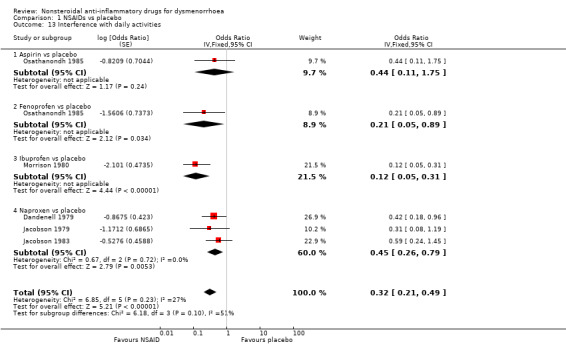

Interference with daily activities

1) NSAIDs versus placebo

Five studies were suitable for meta‐analysis for this outcome. These studies analysed data for 306 women, 90 in cross‐over studies and 216 in parallel‐group studies. They compared the following NSAIDs versus placebo: naproxen (three studies), aspirin, fenoprofen and ibuprofen (one study each). Among individual NSAIDs, there was a difference favouring the following NSAIDs over placebo: naproxen (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.79, three studies, I2 = 0%), fenoprofen (OR 0.21, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.90) and ibuprofen (OR 0.13, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.32). No evidence of a difference was found between aspirin and placebo. When we pooled all data women in the NSAIDs group were less likely to report interference with daily activities than women in the placebo group (OR 0.32, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.49, five studies, I2 = 27%) (Analysis 1.13).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs vs placebo, Outcome 13 Interference with daily activities.

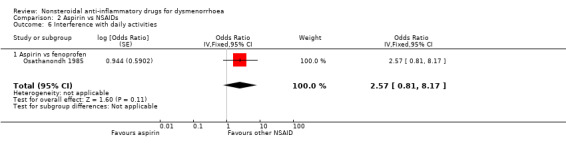

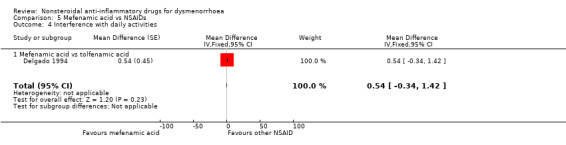

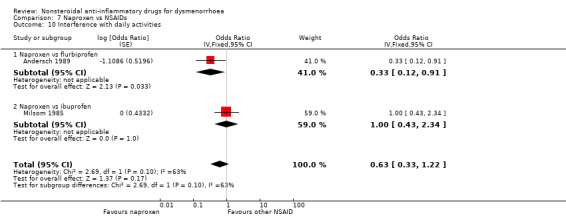

2) NSAIDs versus NSAIDs

Four studies were suitable for meta‐analysis for this outcome. These studies analysed data for 272 women, 187 in cross‐over studies and 85 in parallel‐group studies. They compared the following NSAIDs: naproxen versus flurbiprofen and ibuprofen, aspirin versus fenoprofen, and mefenamic acid versus tolfenamic acid. Women were less likely to report interference with daily activities when taking naproxen than when taking flurbiprofen (OR 0.33, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.91). No evidence of a difference was found between other individual NSAIDs for this outcome. (Analysis 2.6; Analysis 5.4; Analysis 7.10)

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Aspirin vs NSAIDs, Outcome 6 Interference with daily activities.

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Mefenamic acid vs NSAIDs, Outcome 4 Interference with daily activities.

7.10. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Naproxen vs NSAIDs, Outcome 10 Interference with daily activities.

3) NSAIDs versus paracetamol

No data were available for this comparison.

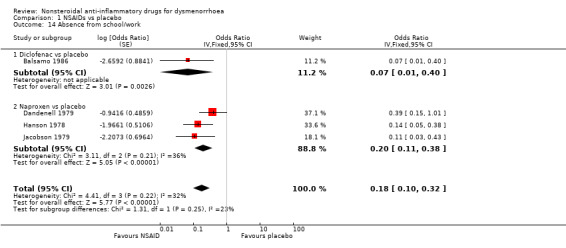

Absence from work or school

1) NSAIDs versus placebo (five studies)

Four studies, all parallel‐group, were suitable for meta‐analysis for this outcome. These studies analysed data for 235 women. One compared diclofenac versus placebo and the other three compared naproxen versus placebo. There was less absenteeism from work or school among women were taking diclofenac (OR 0.07, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.40) or naproxen (OR 0.20, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.38, three studies, I2 = 36%) than in the placebo groups. When we pooled the results for the two comparisons, absenteeism was less likely in the NSAIDs group (OR 0.18, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.32, four studies, I2 = 32%) (Analysis 1.14). One cross‐over trial provided data on this outcome, comparing indomethacin versus placebo. The results favoured indomethacin, but the statistical significance of this finding was not reported (see Table 6).

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 NSAIDs vs placebo, Outcome 14 Absence from school/work.

4. Absence from work/school: NSAIDs versus placebo (per cycle data).

| Comparison | Study ID | No of women | Outcome measure | NSAID | Placebo | Significance |

| Piroxicam versus placebo | Akinluyi 1987 | 60 | No of cycles in which women needed days off work | 6/80 | 54/80 | Not reported |

NSAID = nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug

2) NSAIDs versus NSAIDs (two studies)

Two studies, both cross‐over, were suitable for meta‐analysis for this outcome. These studies analysed data for 114 women. They compared naproxen versus flurbiprofen and versus ibuprofen. No evidence of a difference was found between naproxen and individual NSAIDs for this outcome, nor was there any evidence of a difference between naproxen versus the other NSAIDs when we pooled the data. (Analysis 7.11)

7.11. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Naproxen vs NSAIDs, Outcome 11 Absence from work/school.

3) NSAIDs versus paracetamol

No data were available for this comparison.

Heterogeneity