Abstract

Background

There may be an association between periodontitis and cardiovascular disease (CVD); however, the evidence so far has been uncertain about whether periodontal therapy can help prevent CVD in people diagnosed with chronic periodontitis. This is the second update of a review originally published in 2014, and first updated in 2017. Although there is a new multidimensional staging and grading system for periodontitis, we have retained the label 'chronic periodontitis' in this version of the review since available studies are based on the previous classification system.

Objectives

To investigate the effects of periodontal therapy for primary or secondary prevention of CVD in people with chronic periodontitis.

Search methods

Cochrane Oral Health's Information Specialist searched the Cochrane Oral Health's Trials Register, CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, and CINAHL, two trials registries, and the grey literature to September 2019. We placed no restrictions on the language or date of publication.

We also searched the Chinese BioMedical Literature Database, the China National Knowledge Infrastructure, the VIP database, and Sciencepaper Online to August 2019.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that compared active periodontal therapy to no periodontal treatment or a different periodontal treatment. We included studies of participants with a diagnosis of chronic periodontitis, either with CVD (secondary prevention studies) or without CVD (primary prevention studies).

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors carried out the study identification, data extraction, and 'Risk of bias' assessment independently and in duplicate. They resolved any discrepancies by discussion, or with a third review author. We adopted a formal pilot‐tested data extraction form, and used the Cochrane tool to assess the risk of bias in the studies. We used GRADE criteria to assess the certainty of the evidence.

Main results

We included two RCTs in the review. One study focused on the primary prevention of CVD, and the other addressed secondary prevention. We evaluated both as being at high risk of bias. Our primary outcomes of interest were death (all‐cause and CVD‐related) and all cardiovascular events, measured at one‐year follow‐up or longer.

For primary prevention of CVD in participants with periodontitis and metabolic syndrome, one study (165 participants) provided very low‐certainty evidence. There was only one death in the study; we were unable to determine whether scaling and root planning plus amoxicillin and metronidazole could reduce incidence of all‐cause death (Peto odds ratio (OR) 7.48, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.15 to 376.98), or all CVD‐related death (Peto OR 7.48, 95% CI 0.15 to 376.98). We could not exclude the possibility that scaling and root planning plus amoxicillin and metronidazole could increase cardiovascular events (Peto OR 7.77, 95% CI 1.07 to 56.1) compared with supragingival scaling measured at 12‐month follow‐up.

For secondary prevention of CVD, one pilot study randomised 303 participants to receive scaling and root planning plus oral hygiene instruction (periodontal treatment) or oral hygiene instruction plus a copy of radiographs and recommendation to follow‐up with a dentist (community care). As cardiovascular events had been measured for different time periods of between 6 and 25 months, and only 37 participants were available with at least one‐year follow‐up, we did not consider the data to be sufficiently robust for inclusion in this review. The study did not evaluate all‐cause death and all CVD‐related death. We are unable to draw any conclusions about the effects of periodontal therapy on secondary prevention of CVD.

Authors' conclusions

For primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in people diagnosed with periodontitis and metabolic syndrome, very low‐certainty evidence was inconclusive about the effects of scaling and root planning plus antibiotics compared to supragingival scaling. There is no reliable evidence available regarding secondary prevention of CVD in people diagnosed with chronic periodontitis and CVD. Further trials are needed to reach conclusions about whether treatment for periodontal disease can help prevent occurrence or recurrence of CVD.

Plain language summary

Treating chronic gum inflammation (periodontitis) to prevent heart and blood vessel (cardiovascular) disease

Review question

The main question addressed by this review was whether treatments for chronic periodontitis (gum inflammation) can prevent or manage cardiovascular (heart and blood vessel) diseases.

Background

Chronic periodontitis causes swollen and painful gums, and loss of the alveolar bone that supports the teeth. 'Chronic' is a label that means the disease has continued for some time without treatment. The term 'chronic periodontitis' is being phased out as there is a new system for categorising different types of gum disease, but we have used this term in our review because the studies we found were based on the old system.

There may be a link between periodontitis and cardiovascular diseases. The treatment for chronic periodontitis gets rid of bacteria and infection, and controls inflammation, and it is thought that this may help prevent the occurrence or recurrence of diseases of the heart and blood vessels. We wanted to find out whether periodontal therapy could help prevent death, or reduce the likelihood of having cardiovascular 'attacks' like a stroke or heart attack.

Study characteristics

We searched for scientific research studies known as 'randomised controlled trials', up to 17 September 2019. In this type of study, participants are assigned in a random way to an experimental or control group. People in the experimental group receive the treatment being tested, and people in the control group usually receive either no treatment, placebo (fake treatment), another type of treatment or routine care.

We found two studies to include in our review. One study assessed 165 participants who did not have cardiovascular diseases, but had metabolic syndrome (a combination of risk factors for cardiovascular disease, such as obesity, high blood pressure, and high blood sugar). The other study started off with 303 participants who had cardiovascular diseases, but after a year, only 37 participants were assessed and so we thought the results were not be reliable enough to be used. Both studies had problems with their design, and we judged them to be at high risk of bias.

Key results

For people who have metabolic syndrome but no cardiovascular diseases, we were unable to determine whether treating chronic periodontitis, by removing the plaque and tartar ('scaling') from the roots of teeth and giving antibiotics, reduced the risk of dying or having cardiovascular attacks when compared with scaling the teeth from above the gumline only.

For people with cardiovascular diseases and chronic periodontitis, we found no reliable evidence about the effects of periodontal treatment.

Certainty of the evidence

We classified the evidence as 'very low certainty'. We are uncertain about the findings because there are only two small studies, at high risk of bias, with very imprecise results. Overall, we cannot draw any reliable conclusions from the findings. Further research is needed.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) covers a wide array of disorders (including diseases of the cardiac muscle and the vascular system supplying the heart, brain and other vital organs), such as coronary heart disease (with narrowing or blockage of the coronary arteries, which can cause angina and myocardial infarction) and stroke (with narrowing, blockage or haemorrhage of the cerebrovascular system), which are the world's largest killers, causing the death of 17.1 million individuals per year (Nabel 2003; Jamison 2006). There are a variety of risk factors involved in the pathogenesis of CVD, such as smoking or passive smoking (Law 1997; He 1999; Kallio 2010), hypertension (Di'Auto 2019), excess sodium intake (Strazzullo 2009), and hyperlipidaemia (Austin 1999). Numerous successful modalities of treatment that are based on these aetiological or risk factors have been developed (Law 2009; Manktelow 2009; Rees 2013). However, in modern society, people are increasingly exposed to such factors, and the aforementioned therapies are still not enough, thus, the incidence of CVD increases year on year (WHO 2007).

Recently, considerable attention has been paid to the aetiological role of acute or chronic infections on CVD; infections that accelerate vascular inflammation and promote thrombosis of vascular vessels (Herzberg 2005; Viles‐Gonzalez 2006), are believed to be a secondary pathogenic pathway (Smeeth 2004; Hansson 2006; Moutsopoulos 2006). Among the infections, periodontitis might be the most common. It is an infectious disease resulting in inflammation within the supporting tissues of teeth, resulting in progressive attachment and alveolar bone loss (Armitage 1999). In the last century, periodontitis was reported to affect 6% to 20% of the population (Oliver 1991; AAP 1999); and the estimate of disease in the USA exceeds 47%. In those over 65 years, 64% have either moderate or severe periodontitis (Eke 2012).

The label 'chronic periodontitis' has not been retained in the new classification for periodontal diseases, which was developed at a World Workshop run by the American Academy of Periodontology (AAP) and the European Federation of Periodontology (EFP) in 2017 (Caton 2018). For this version of the review, we are retaining the descriptor 'chronic', and the new classification will be used in the next review update. The British Society of Periodontology has published a flowchart to assist dental practitioners to implement the new classification (see British Society of Periodontology flowchart).

There are two reasons why periodontitis and CVD are believed to be related. First, the levels of systemic inflammation increase when moderate or severe periodontitis is present, and when treating periodontitis, there is a clear reduction in the clinical signs, with a decrease in the levels of systemic inflammatory mediators (Tonetti 2007; Paraskevas 2008). Secondly, the periodontal bacteria may invade the damaged periodontal tissue, enter the bloodstream, and further invade the cardiovascular system. Several periodontal pathogens, such as Porphyromonas gingivalis, Bacteroides forsythus, Prevotella intermedia and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans have been detected in carotid atheromas by polymerase chain reaction (Haraszthy 2000; Padilla 2006). Experimental studies have shown that the presence of these periodontal pathogens and oral bacteria in the atheromas could induce platelet activation and aggregation through collagen‐like platelet aggregation‐associated protein expression. The activated and aggregated platelets could then play an important role in atheromatous formation and thrombosis, and finally lead to cardiovascular events (Herzberg 1983; Herzberg 1996). Besides this, periodontal bacteria may play a role in the formation of coronary atherosclerotic plaques, which is indirectly proven by the presence of bacterial DNA from the oral pathogenic micro‐organisms in coronary atherosclerotic plaques and the special characteristics of the aortic aneurysms in cardiovascular disease patients harbouringP. gingivalis (Mahendra 2010; Nakano 2011). They can induce cell‐specific innate immune inflammatory pathways, causing and maintaining a chronic state of inflammation at sites distant from the periodontitis (Hayashi 2010). An indirect association between the two diseases was identified by investigators, as they share similar risk factors, such as smoking, diabetes mellitus, obesity, and hypertension (Friedewald 2009; Han 2017). The association between periodontitis and CVD was proven by clinical trials, and further confirmed by meta‐analysis (Janket 2003; Scannapieco 2003; Khader 2004). Based on this evidence, some investigators have concluded that there could be a mild to moderate association between periodontitis and CVD (Genco 2002; Hujoel 2002; Hansen 2016).

As a relationship between periodontitis and CVD is evident, it is rational to explore whether CVD can be managed, or its occurrence or recurrence prevented, by treating periodontitis.

Description of the intervention

It is believed that bacterial infection is the main aetiological factor for periodontitis. Other factors, such as occlusal trauma, calculus, and smoking are considered risks for accelerating the progression of periodontitis (Meng 2009). Fortunately, there are several effective ways to control these factors, and further control periodontitis. Supragingival and subgingival scaling and root planing (SRP) could remove the periodontal bacteria or calculus, and create a relatively healthy environment to reduce bacterial regrowth (Eberhard 2015; Lamont 2018). Occlusal adjustment has also been suggested as a means to eliminate the harmful occlusal trauma that induces abnormal stress on the periodontal tissue (Foz 2012). Periodontal surgery, including guided tissue regeneration, replaces the lost or necrotic bone and periodontal tissue (Esposito 2009). All of these therapies play a role in reducing the biofilm, or number of bacteria, and controlling the accelerating factors. Such maintenance and preventive interventions should be adopted for periodontitis sufferers as a life‐long commitment to control periodontal inflammation and disease recurrence.

Periodontal medicine is now a recognised discipline, which aims to treat the systemic diseases that are suspected to be associated with periodontal disease, by applying periodontal therapies. One Cochrane Review found low‐quality evidence that periodontal treatment (scaling and root planing) may help control diabetes mellitus in the short term (Simpson 2015); another found low‐quality evidence that periodontal therapy may reduce low birth weight (less than 2500 g (Iheozor‐Ejiofor 2017)).

How the intervention might work

Periodontal therapy may clean up the infectious sources and control the acceleration of periodontitis. Some studies have already confirmed that high blood pressure can be lowered and serum inflammatory markers, such as interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) and C‐reactive protein (CRP) can be significantly reduced after such treatment (D'Aiuto 2005; Blum 2007; Martin‐Cabezas 2016). Tüter and colleagues indicated that periodontal therapy with a subantimicrobial dose of doxycycline could increase serum levels of apolipoprotein‐A and high‐density lipoprotein, reduce total cholesterol levels, and further decrease the risk of cardiovascular events (D'Aiuto 2005; Tüter 2007). However, as mentioned previously, periodontitis and CVD may have similar risk factors (smoking, obesity, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus), some of which are modifiable and some of which are non‐modifiable. The mechanism of action of periodontal therapy for the management of CVD is still unknown; it may control periodontitis directly, change modifiable risk factors, or both. In addition, there is insufficient evidence to determine the superiority of different protocols or adjunctive strategies to improve tooth maintenance during supportive periodontal therapy for the general population (Manresa 2018). It remains unclear whether adjuvant therapy could facilitate the effects of periodontal therapy in the management of CVD.

Why it is important to do this review

Cochrane Oral Health undertook an extensive prioritisation exercise in 2014 to identify a core portfolio of titles that were the most clinically important ones to maintain on the Cochrane Library (Worthington 2015). This review was identified as a priority title by the periodontal expert panel (Cochrane Oral Health priority review portfolio). This is the second update of a review originally published in 2014 and first updated in 2017 (Li 2014; Li 2017).

Objectives

To investigate the effects of periodontal therapy for primary or secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease in people with chronic periodontitis.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCT) that aimed to test the effects of different periodontal therapies for people diagnosed with chronic periodontitis, with or without cardiovascular disease (CVD), with follow‐up times of at least one year. The studies could be primary prevention studies or secondary prevention studies. In the former, the focus would be on using periodontal treatment to prevent the occurrence of CVD. Participants in the secondary prevention studies would have CVD, or have been previously diagnosed with CVD, so the focus would be on preventing recurrence.

Types of participants

We considered trials with participants who met the following criteria, regardless of age, sex, race, social or economic status.

Diagnosis of at least moderate chronic periodontitis with pocketing greater than or equal to 4 mm.

Absence of any known genetic or congenital heart defects and aggressive periodontitis.

For primary prevention, no existing or previous diagnosis of CVD (including angina, myocardial infarction, stroke); for secondary prevention, an existing or previous diagnosis of CVD.

Absence of other sources of inflammation, such as pulpal infections and active caries.

No periodontal treatment within preceding six months (participants should have active disease and not be in a periodontal maintenance programme).

We did not include participants for whom periodontal therapy was contraindicated (including pregnant or lactating women, people with severe systemic diseases other than CVD), or participants who were unable to complete assessments during the follow‐up period.

Types of interventions

Experimental: periodontal therapy of subgingival scaling and root planing (SRP), or SRP in combination with systemic antibiotic or host modulation, with or without other active remedies.

Control: maintenance therapy (supragingival scaling, antimicrobial rinses), or no periodontal treatment, with or without the same basic remedies as those in the intervention group.

Types of outcome measures

We classified outcomes as primary (the main outcomes we considered when drawing conclusions) and secondary. We considered only long‐term outcomes, i.e. those measured at one year or more.

Primary outcomes

All‐cause and CVD‐related death

All cardiovascular events (angina, myocardial infarction, stroke)

Secondary outcomes

Modifiable cardiovascular risk factors: blood pressure; lipids including cholesterol, triglycerides, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, very low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol

Blood test results, including serum levels of high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein (hs‐CRP), apolipoprotein‐A, apolipoprotein‐B

Heart function parameters (such as ejection fraction)

Revascularisation procedures

Adverse events due to periodontal therapy (e.g. tooth sensitivity, mouth discomfort)

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Cochrane Oral Health’s Information Specialist conducted systematic searches in the following databases for RCTs and controlled clinical trials, with no language, publication year, or publication status restrictions:

Cochrane Oral Health’s Trials Register (searched 17 September 2019; Appendix 1);

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2019, Issue 8) in the Cochrane Library (searched 17 September 2019; Appendix 2);

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to 17 September 2019; Appendix 3);

Embase Ovid (1980 to 17 September 2019; Appendix 4).

CINAHL EBSCO (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; 1937 to 17 September 2019; Appendix 5);

OpenGrey (searched 17 September 2019; Appendix 6).

We modelled subject strategies on the search strategy designed for MEDLINE Ovid. Where appropriate, we combined them with subject strategy adaptations of the highly sensitive search strategy, designed by Cochrane for identifying RCTs and controlled clinical trials, as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Chapter 6 (Lefebvre 2011).

We also searched the following databases:

Chinese BioMedical Literature Database (CBM; 1978 to 29 August 2019);

China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI; 1994 to 29 August 2019);

VIP (1989 to 29 August 2019).

The search attempted to identify all relevant studies, irrespective of language. We translated non‐English papers.

Searching other resources

Cochrane Oral Health's Information Specialist searched the following databases for ongoing trials:

US National Institutes of Health Trials Register (http://clinicaltrials.gov; to 17 September 2019; Appendix 7);

World Health Organization (WHO) Clinical Trials Registry Platform (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/default.aspx; to 17 September 2019; Appendix 8).

We also searched Sciencepaper Online (2003 to 29 August 2019).

We checked the reference lists of all eligible trials for additional studies. We contacted the first authors of all included studies by email for any ongoing or unpublished studies examining the efficacy and safety of periodontal therapy for the prevention of CVD.

Handsearching

We handsearched all the Chinese professional journals and some important English journals in the dental and cardiovascular fields from the first issue to May 2011. We handsearched some of the important English journals to May 2019 (see Table 3 and Table 4 for details).

1. Stomatology journals handsearched.

| Journal name | By ZD Shi, et al | By CJ Li, et al | By CJ Li and ZK Lv | By CJ Li, et al |

| Chinese Journal of Stomatology | 1953 to Dec 2000 | Jan 2001 to Dec 2009 | Jan 2010 to May 2011 | |

| Stomatology | 1981 to Dec 2000 | Jan 2001 to Dec 2009 | Jan 2010 to May 2011 | |

| West China Journal of Stomatology | 1983 to Dec 2000 | Jan 2001 to Dec 2009 | Jan 2010 to May 2011 | |

| Journal of Practical Stomatology | 1985 to Dec 2000 | Jan 2001 to Dec 2009 | Jan 2010 to May 2011 | |

| Journal of Clinical Stomatology | 1985 to Dec 2000 | Jan 2001 to Dec 2009 | Jan 2010 to May 2011 | |

| Journal of Comprehensive Stomatology | 1985 to Dec 2000 | Jan 2001 to Dec 2009 | Jan 2010 to May 2011 | |

| Journal of Modern Stomatology | 1987 to Dec 2000 | Jan 2001 to Dec 2009 | Jan 2010 to May 2011 | |

| Chinese Journal of Conservative Dentistry | 1991 to Dec 2000 | Jan 2001 to Dec 2009 | Jan 2010 to May 2011 | |

| Journal of Maxillofacial Surgery | 1991 to Dec 2000 | Jan 2001 to Dec 2009 | Jan 2010 to May 2011 | |

| Shanghai Journal of Stomatology | 1992 to Dec 2000 | Jan 2001 to Dec 2009 | Jan 2010 to May 2011 | |

| Chinese Journal of Dental Material and Devices | 1992 to Dec 2000 | Jan 2001 to Dec 2009 | Jan 2010 to May 2011 | |

| Beijing Journal of Stomatology | 1993 to Dec 2000 | Jan 2001 to Dec 2009 | Jan 2010 to May 2011 | |

| Chinese Journal of Dental Prevention and Treatment | 1993 to Dec 2000 | Jan 2001 to Dec 2009 | Jan 2010 to May 2011 | |

| Chinese Journal of Orthodontics | 1994 to Dec 2000 | Jan 2001 to Dec 2009 | Jan 2010 to May 2011 | |

| Chinese Journal of Implantology | 1996 to Dec 2000 | Jan 2001 to Dec 2009 | Jan 2010 to May 2011 | |

| Journal of International Stomatology | Jan 2001 to Dec 2009 | 1974 to Dec 2000, Jan 2010 to May 2011 | ||

| Chinese Journal of Prosthodontics | Jan 2001 to Dec 2009 | 1999 to Dec 2000, Jan 2010 to May 2011 | ||

| China Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery | 2003 to Dec 2009 | Jan 2010 to May 2011 | ||

| Chinese Journal of Geriatric Dentistry | 2002 to Dec 2009 | Jan 2010 to May 2011 | ||

| International Journal of Oral Science | 2009 to May 2011 | June 2011 to March 2019 | ||

| International Journal of Periodontics & Restorative Dentistry | 1981 to May 2011 | June 2011 to March 2019 | ||

| Journal of Clinical Periodontology | 1974 to May 2011 | June 2011 to March 2019 | ||

| Journal of Periodontal Research | 1966 to May 2011 | June 2011 to March 2019 | ||

| Journal of Periodontology | 1949 to May 2011 | June 2011 to March 2019 | ||

| Periodontology 2000 | 1993 to May 2011 | June 2011 to March 2019 |

2. Cardiovascular disease journals handsearched.

| Journal name | By CJ Li and ZK Lv |

| Journal of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Diseases | 1982 to May 2011 |

| Chinese Journal of Cardiology | 1973 to May 2011 |

| International Journal of Cerebrovascular Diseases | 1993 to May 2011 |

| Prevention and Treatment of Cardio‐Cerebral‐Vascular Disease | 2001 to May 2011 |

| Chinese Journal of Cerebrovascular Diseases | 2004 to May 2011 |

| Chinese Journal of Geriatric Heart Brain and Vessel Diseases | 1999 to May 2011 |

| Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine on Cardio‐/Cerebrovascular Disease | 2003 to May 2011 |

| Practical Journal of Cardiac Cerebral Pneumal and Vascular Disease | 1993 to May 2011 |

| Circulation | 1950 to May 2011 |

| European Heart Journal | 1980 to May 2011 |

| Cardiovascular Research | 1967 to May 2011 |

| Circulation Research | 1953 to May 2011 |

| Cardiology | 1937 to May 2011 |

| Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology | 1981 to May 2011 |

| American Journal of Cardiology | 1958 to May 2011 |

We checked that none of the included studies in this review were retracted due to error or fraud.

We did not perform a separate search for adverse effects of interventions used; we considered adverse effects described in included studies only.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (Wei Liu and Yubin Cao) carried out the study selection in duplicate, according to the selection criteria. We had designed the search to be sensitive, and include controlled clinical trials, which we filtered out early in the selection process if they were not randomised. We initially screened the titles and abstracts from the search results to look for possible eligible studies. We retrieved full texts of these studies, which were independently assessed by both review authors to further assess eligibility. We discussed any disagreements on study inclusion to reach consensus, and when necessary, a third review author arbitrated. We developed a PRISMA flow diagram of the whole process, as recommended (Liberati 2009).

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (Wei Liu and Yubin Cao) carried out the data extraction in duplicate. Disagreements were resolved by discussion, and an arbitrator was involved when the disagreement remained unresolved. We designed a customised data extraction form, using Microsoft Access 2007, in accordance with guidance from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version (Higgins 2011). We pilot‐tested this, using a sample of the studies focusing on this topic, and then applied it to all the included studies. We collected the following data.

Source: study identification (ID), reviewer ID, citation, and contact details.

Eligibility: reasons for inclusion and exclusion.

Methods of the study: centres and their location, duration, design, sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, and statistical methods.

Participants: total number, setting, age and sex, diagnostic criteria for both cardiovascular disease and periodontitis, inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Interventions: number of groups; content details, including periodontal therapy, control treatment, and other active treatment; time, frequency, dose, and usage of drugs administered.

Outcomes: definition of measures and units of the measurements, time points of measurement, sample size calculation, number of participants allocated to each group, numbers lost to follow‐up and the reasons, detailed summary data for each group.

Miscellaneous: funding, key conclusions, whether we required correspondence, and miscellaneous comments from review authors.

For studies that had multiple groups, we had planned to extract data for all groups relevant to this review and record these in the 'Characteristics of included studies' section.

Where there was any missing information, we contacted the original investigators of the included studies for clarification.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We carried out 'Risk of bias' assessments, following the approach described in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version (Higgins 2011). We contacted authors of the included studies by email to obtain or clarify any unreported or unclear information on the risk of bias of the studies. Two review authors (Wei Liu and Yubin Cao) independently assessed the risk of bias according to the published article and the trial authors' responses. They discussed any discrepancies, and a third review author arbitrated when necessary.

Risk of bias assessment of the included studies

We judged the risk of bias in each of the included studies for seven domains (as identified in the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool). For each of the following domains, we assigned a judgment of low, high, or unclear risk of bias.

Random sequence generation: selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate generation of a randomised sequence.

Allocation concealment: selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate concealment of the allocation.

Blinding of participants and personnel: performance bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by participants and personnel during the study.

Blinding of outcome assessment: detection bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by outcome assessors.

Incomplete outcome data: attrition bias due to amount, nature, or handling of incomplete outcome data.

Selective reporting: reporting bias due to selective outcome reporting.

Other bias: bias due to problems not covered elsewhere in the table, such as baseline imbalance, confounding, contamination and co‐interventions, etc.

We assessed the overall risk of bias for each study as:

low risk of bias, where there was a low risk of bias for all domains, or any plausible bias was unlikely to seriously alter the study results;

unclear risk of bias, where there was an unclear risk of bias for one or more domains, or any plausible bias raised some doubt about the study results; or

high risk of bias, where there was a high risk of bias for one or more domains, or any plausible bias might seriously weaken confidence in the results.

Measures of treatment effect

Our selection of statistical methods was dependent on whether the data were dichotomous, continuous, or presented as time‐to‐event. We treated both primary outcomes as dichotomous data or time‐to‐event data.

For dichotomous data, we calculated risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We used the Peto odds ratio (Peto OR) with 95% CI if the incidence of the events observed was very low.

For continuous data, we calculated mean differences (MD) and 95% CIs for change from baseline or the final values, if they were measured by similar indices. If the data had been measured using different indices, we would have used standardised mean differences (SMD) and 95% CIs.

Unit of analysis issues

We had planned to analyse cluster‐randomised trials and studies with more than two intervention groups differently from RCTs. For cluster‐randomised trials, to avoid any inappropriate analyses in the original studies, we would have adopted approximate analyses‐effective sample sizes, following the guidance of the first edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). For studies with more than two intervention groups, as each meta‐analysis addressed only a single pair‐wise comparison, we would have considered two approaches. The first was to combine groups to create a single pair‐wise comparison; if this first approach failed, we had planned to select the most relevant pair of interventions.

Dealing with missing data

For trials with missing data, we contacted the trial authors for clarification and supplementation of the data. If there was no reply, we planned to adopt the following statistical methods, following guidance in the first edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). If the standard deviation (SD) of the continuous data was not reported, we would calculate it: (i) from the standard error (SE), 95% CIs, P values or t values, ranges or interquartile ranges reported in the article; or (ii) if the SD of change from baseline values was missing, we would calculate it using the correlation coefficient. We planned to conduct Intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis if there were sufficient data. If ITT could not be adopted, we planned to analyse the available data and interpret results with caution

Assessment of heterogeneity

We planned to use the Chi² test for heterogeneity to examine if heterogeneity existed among the included studies. We used the I² statistic to estimate the impact of the heterogeneity:

0% to 40% may indicate slight heterogeneity;

30% to 60% may indicate moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90% may indicate substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100% may indicate very substantial (considerable) heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

To avoid reporting biases, we carried out a comprehensive search that included grey literature and ongoing studies (seeSearch methods for identification of studies). We planned to assess publication bias and other reporting biases with the help of funnel plots, if there were more than 10 trials providing results for one outcome. Asymmetry of the funnel plot could suggest potential publication bias, and would have been further tested by the methods introduced by Egger 1997 (continuous outcomes) and Rücker 2008 (dichotomous outcomes).

Data synthesis

We had planned to pool data if there was more than one study with similar comparisons that reported the same outcome, using a fixed‐effect meta‐analysis model for two or three studies, and random‐effects for four or more.

The method of meta‐analysis for computing different kinds of data varied. We used the Review Manager 5 default fixed‐effect model, Mantel‐Haenszel method, for dichotomous data and calculated MD or SMD for continuous data, unless the data were only in the appropriate form for generic inverse variance for continuous data (Review Manager 2014). In addition, we planned to use the Peto or inverse variance method for time‐to‐event data.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Had there been sufficient studies, we would have investigated any heterogeneity by carrying out subgroup analyses according to the different courses and instruments of periodontal therapy and different adjuvant treatments.

Sensitivity analysis

To test the stability of the conclusions, we had planned to carry out sensitivity analyses based on different assumptions, such as excluding studies with evident biases, using different methods to deal with missing data, different models of meta‐analysis, exclusion of studies causing significant statistical heterogeneity, or ITT analysis. We would have reported the results in detail, and evaluated their impact on the stability of the conclusions, in the discussion section.

Summary of main results

To provide key information on the effects and safety of periodontal therapy for CVD management in a quick and accessible format, we developed a 'Summary of findings' table for each comparison. This shows the certainty of the body of evidence for the primary outcomes (all‐cause death, all CVD‐related death, all cardiovascular events). Our assessment of the body of evidence involved consideration of risk of bias at the outcome level, directness of the evidence, heterogeneity, precision of effect estimates, and risk of publication bias (see Assessment of reporting biases). We used the GRADE system to evaluate the certainty of the evidence for each comparison and outcome, and GRADEpro GDT software (Atkins 2004; Guyatt 2008; Higgins 2011; GRADEpro GDT). We assessed the certainty of the evidence as high, moderate, low, or very low.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

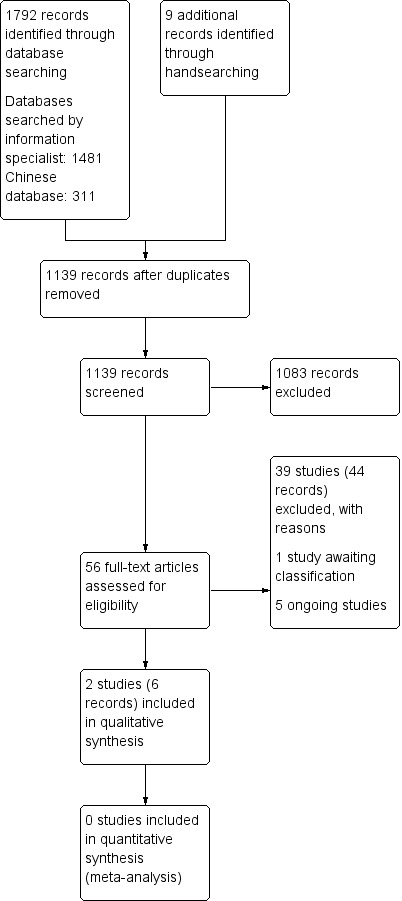

We identified a total of 1801 records from electronic searches and handsearching. After removing duplicates, we screened 1139 records by scanning the titles and abstracts. We considered 56 records to be potentially eligible, and obtained the full texts for further consideration. We excluded 39 published studies, reported in 44 articles. There are five ongoing studies (see Characteristics of ongoing studies). One study is awaiting classification, because the authors have not responded to requests for more information about the eligibility criteria (Zhao 2016; see Characteristics of studies awaiting classification). We included two studies (reported in six articles) in this review (PAVE 2008; Lopez 2012). A flow diagram illustrating the study selection process is shown in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram

Included studies

We included two RCTs in this review (PAVE 2008; Lopez 2012). See the Characteristics of included studies tables for full details.

1. Primary prevention

We included one primary prevention study, which was a parallel‐arm, double‐blind RCT of one‐year duration, in 165 participants with metabolic syndrome and periodontitis (Lopez 2012).

Participants

Participants were eligible if they were aged 35 to 65 years, had periodontitis and metabolic syndrome, and retained ≥ 14 teeth. The diagnostic criteria for periodontitis were the presence of four or more teeth with one or more sites with probing depth (PD) ≥ 4 mm and concomitant clinical attachment loss of ≥ 3 mm. The diagnosis of metabolic syndrome was made when ≥ 3 of the following risk determinants were present: 1) central obesity (> 102 cm in males; > 88 cm in females) or body mass index (BMI) > 30 kg/m²; 2) dyslipidaemia defined by plasmatic triglycerides level > 150 mg/dL; 3) high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) < 40 mg/dL in males or < 50 mg/dL in females; 4) blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg; or 5) fasting glucose ≥ 110 mg/dL.

Intervention

Participants in the experimental treatment group received supragingival and subgingival scaling, crown polishing, and root planing under local anaesthesia using ultrasound and hand instruments, and oral hygiene instruction. In addition, one week before beginning root planning, participants were given metronidazole (250 mg) and amoxicillin (500 mg) tablets, three times daily, for seven days.

Control

Participants in the control treatment group received a treatment consisting of supragingival scaling with ultrasound instruments, crown polishing, and two placebo tablets three times daily, for seven days. The metronidazole, amoxicillin, and placebo tablets were identical in appearance.

Outcomes

Risk factors for cardiovascular disease were recorded; serum lipoprotein cholesterol, glucose, body mass index (BMI), C‐reactive protein (CRP) and fibrinogen concentrations, and clinical periodontal parameters were assessed at baseline and every 3 months until 12 months after therapy. Participants with intercurrent systemic infections during the study period were excluded from the analysis of parameters above after the intercurrent infections were detected. All cardiovascular events, including myocardial infarction and stroke, were recorded.

2. Secondary prevention

We included one secondary prevention study, which was a multi‐centre, parallel‐group, single‐blind RCT, with 303 participants randomised into a periodontal therapy group or community care group (PAVE 2008).

Participants

Participants had to have ≥ 50% blockage of one coronary artery or have had a coronary event within the preceding three years (but at least three months before selection for study participation). The periodontal inclusion criteria were: the presence of at least six natural teeth, including third molars, with at least three teeth with probing pocket depth (PPD) ≥ 4 mm, at least two teeth with interproximal clinical attachment loss (CAL) ≥ 2 mm, and ≥ 10% of sites having bleeding on probing (BOP).

Intervention

The intervention group (N = 151) received oral hygiene instruction and one regimen of full‐mouth scaling and root planing (SRP) with local anaesthesia (30% of the treatment was completed more than two months after randomisation). Only 92.7% of the participants received the treatment; one participant received SRP outside the study.

Control

Participants in the control group (community care group; N = 152) received oral hygiene instruction and were given a copy of their oral radiographs, with a letter stating the tentative oral findings; investigators recommended they seek the opinion of a dentist (9% of the participants in the control group got SRP outside the study within six months and 11% of them got SRP within the entire follow‐up period).

Outcomes

The participants were observed for between 6 and 25 months. The following outcomes were reported: serious cardiovascular adverse events (all cardiovascular events), serum high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein (hs‐CRP), number of participants who had high hs‐CRP, and adverse events measured as the development of an undesirable medical or dental condition, or the deterioration of a pre‐existing medical or dental condition, following or during exposure to a pharmaceutical product or medical or dental procedure, whether or not investigators considered it was causally related to the intervention. Data on adverse events due to periodontal therapy were analysed in this review.

Excluded studies

We excluded 39 studies (44 articles) for the following reasons: follow‐up was less than one year (14 studies); study was not an RCT (10 studies); there were no CVD patients or CVD outcomes (4 studies); participants in the intervention group did not get any active periodontal therapy (2 studies); participants were pregnant (2 studies); study did not evaluate periodontal therapy (1 study); the same therapy was provided to both groups (1 study); participants did not have periodontitis (1 study); half of participants had aggressive periodontitis (1 study); participants had rheumatoid arthritis (1 study); participants were receiving maintenance therapy (1 study) (see Characteristics of excluded studies tables).

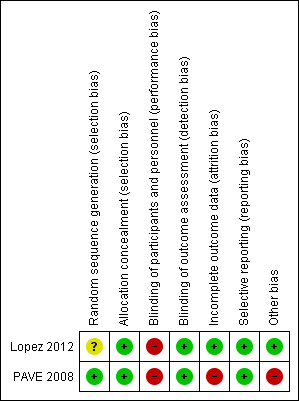

Risk of bias in included studies

We assessed both studies as being at high risk of bias overall. See the Characteristics of included studies tables and Figure 2.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

Allocation

Lopez 2012 used computer‐generated randomisation for the first eight participants enrolled, and the minimisation method for the following participants, then allocated participants using opaque envelopes with cardboard inside so they were impermeable to light. However, the authors did not perform randomisation according to the protocol, but changed the method during the trial. Hence, we assessed it at unclear risk of bias for sequence generation and at low risk for allocation concealment.

PAVE 2008 used a computer‐generated randomised table and used central allocation. We assessed it at low risk bias for both random sequence generation and allocation concealment.

Blinding

Due to the nature of the interventions, it was impossible to achieve blinding of participants and personnel in either study. Therefore, we assessed both studies at high risk of performance bias.

Blinding of outcome assessment was described in both studies, so we considered them at low risk of detection bias.

Incomplete outcome data

Only 3% of participants were lost to follow‐up and excluded from the analysis in Lopez 2012, so we judged it at low risk of bias. Only 37 of the 303 participants received follow‐up at one year, thus we assessed PAVE 2008 at high risk of attrition bias.

Selective reporting

We assessed both studies at low risk of bias because variables were reported as stated.

Other potential sources of bias

We did not identify any other potential sources of bias in Lopez 2012. For PAVE 2008, 92.7% of participants in the treatment group received the treatment. One participant in the intervention group received SRP outside the study. Eleven per cent of participants in the control group had received SRP by the end of the follow‐up period. We assessed this as high risk of bias due to contamination and co‐interventions.

Effects of interventions

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Primary prevention: scaling and root planing (SRP) plus antibiotics versus supragingival scaling for people with periodontitis and metabolic syndrome.

| Primary prevention: scaling and root planing (SRP) plus antibiotics versus supragingival scaling | ||||||

| Population: people with periodontitis and metabolic syndrome Settings: hospitals Intervention: scaling and root planing (SRP) plus antibiotics Comparison: supragingival scaling | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Supragingival scaling | SRP plus antibiotics | |||||

| All‐cause death Follow‐up: 12 months | 12 per 1000 | 71 per 1000 | Peto OR 7.48, 95% CI 0.15 to 376.98 | 165 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b | |

| All CVD‐related death Follow‐up: 12 months | 12 per 1000 | 71 per 1000 | Peto OR 7.48, 95% CI 0.15 to 376.98 | 165 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b | |

| All cardiovascular events Follow‐up: 12 months | 49 per 1000 | 237 per 1000 | Peto OR 7.77, 95% CI 1.07 to 56.1 | 165 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.. | ||||||

aDowngraded two levels due to serious risk of bias (performance bias) bDowngraded two levels due to serious imprecision

Summary of findings 2. Secondary prevention: periodontal treatment (scaling and root planing plus advice) versus community care (advice only) for the management of cardiovascular disease in people with chronic periodontitis.

| Secondary prevention: periodontal treatment versus community care | ||||||

| Population: people with cardiovascular disease and chronic periodontitis Settings: hospitals Intervention: periodontal treatment – scaling and root planing (SRP) plus advice Comparison: community care – advice only | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Community care (advice only) | Periodontal treatment (SRP and advice) | |||||

| All‐cause death | Outcome not reported | |||||

| All CVD‐related death | Outcome not reported | |||||

| All cardiovascular events Follow‐up: 6 to 25 months | One study of 303 participants assessed this outcome; however, we considered data were unreliable as participants were followed up for different lengths of time, and.only just over 10% of participants were evaluated at follow‐up of 1 year or longer. | 1 study | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa | |||

| *The basis for the assumed risk is the control group risk in the one included study. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; CVD: cardiovascular disease; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded to three levels due to risk of bias from high attrition

1. Primary prevention

1.1 Scaling and root planing (SRP) plus antibiotics versus supragingival scaling

One study evaluated this comparison. The experimental group used amoxicillin and metronidazole while the control group used two placebos (Lopez 2012). Both groups received oral hygiene instruction and were provided with toothbrushes and toothpaste.

1.1.1 All‐cause death

It is uncertain whether SRP and antibiotics can prevent death by any cause at 12‐month follow‐up when compared to supragingival scaling. One participant died due to fatal myocardial infarction in the SRP plus amoxicillin and metronidazole group and there were no deaths in the control group (Peto odds ratio (OR) 7.48, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.15 to 376.98; 165 participants; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Primary prevention: SRP plus antibiotics versus supragingival scaling, Outcome 1 All‐cause death (12 months).

1.1.2 All CVD‐related death

As mentioned in the results of all‐cause death, only one participant died. It is uncertain whether SRP plus antibiotics can prevent CVD‐related death at 12‐month follow‐up compared to supragingival scaling (Peto OR 7.48, 95% CI 0.15 to 376.98; 165 participants; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Primary prevention: SRP plus antibiotics versus supragingival scaling, Outcome 2 All CVD‐related death (12 months).

1.1.3 All cardiovascular events

SRP plus antibiotics might lead to an increase in cardiovascular events at 12‐month follow‐up compared to supragingival scaling (Peto OR 7.77, 95% CI 1.07 to 56.1; 165 participants; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.3). In the SRP plus antibiotics group, four participants had cardiovascular events (one participant died due to fatal myocardial infarction; one had an Ischaemic stroke before the last root planing appointment; one had a stroke eight weeks after periodontal therapy; and one had several small cerebral hemorrhagic events seven months after periodontal therapy). No participants had cardiovascular events in the supragingival scaling plus two placebos group.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Primary prevention: SRP plus antibiotics versus supragingival scaling, Outcome 3 All cardiovascular events (12 months).

1.1.4 Blood test results

Based on the mixed‐effects linear regression analysis, it is uncertain whether SRP plus antibiotics lead to a difference in C‐reactive protein (β coefficient ‐0.002, 95% CI ‐0.19 to 0.20), or fibrinogen (β coefficient 10.9, 95% CI ‐12.0 to 33.8) levels between two treatment groups (very‐low certainty evidence).

1.1.5 Adverse events related to periodontal therapy

It is uncertain whether SRP plus antibiotics lead to a difference in adverse events at 12‐month follow‐up when compared with supragingival scaling (Peto OR 0.14, 95% CI 0.00 to 6.90; 165 participants; very‐low certainty evidence; Analysis 1.4). One participant in the supragingival scaling plus two placebos group showed progression of periodontitis. One participant had a severe allergic reaction to an environmental chemical, but it was not attributed to periodontal therapy.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Primary prevention: SRP plus antibiotics versus supragingival scaling, Outcome 4 Adverse events (12 months).

2. Secondary prevention

2.1 Periodontal treatment versus community care

Participants in the periodontal treatment group, who received scaling and root planing (SRP) and oral hygiene instruction (OHI), were compared with those in the community care group, who received OHI, radiographs of their mouths, and a letter about the findings, along with advice to contact a dentist (PAVE 2008).

2.1.1 All‐cause death

Not reported.

2.1.2 All CVD‐related death

Not reported.

2.1.3 All cardiovascular events

Because of variable follow‐up periods (6 to 25 months) and the loss to follow‐up by one year being almost 90%, we did not consider the results from this study to be useful for analysis. It is therefore impossible to ascertain whether periodontal treatment leads to a difference in cardiovascular events when compared with community care.

2.1.4 Blood test results

Serum high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein (hs‐CRP) was tested at one year. As the loss to follow‐up was almost 90%, we did not consider the data to be useful for analysis.

2.1.5 Adverse events related to periodontal therapy

Because of variable follow‐up periods (6 to 25 months) and the loss to follow‐up by one year being almost 90%, we did not consider the results from this study to be useful for analysis. It is therefore uncertain whether adverse events are more likely with either of the interventions.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The aim of the review was to evaluate the effect of periodontal treatment in the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease for people with chronic periodontitis. We included two randomised controlled trials (RCT) in the review.

For primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in people with periodontitis and metabolic syndrome, it was not possible to establish the effects of scaling and root planing (SRP) plus antibiotics compared to supragingival scaling on all‐cause mortality, all CVD‐related death, all cardiovascular events, levels of C‐reactive protein (CRP) and fibrinogen, or adverse events due to periodontal therapy (very low‐certainty evidence).

For secondary prevention, death was not an outcome in the one relevant study; the variable follow‐up periods and extremely high loss to follow‐up meant we could not draw any conclusions about the effect of periodontal treatment compared with community care on all cardiovascular events, levels of CRP, or adverse events due to periodontal therapy (very low‐certainty evidence).

Because there were only two included studies, providing very low‐certainty evidence, we should treat the results cautiously.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The review aimed to include both primary and secondary prevention studies assessing periodontal therapy in people with chronic periodontitis. The evidence from this review can be applied to adults in most age groups, except those over the age of 75 years. The following outcomes are not covered in this review: modifiable cardiovascular risk factors, heart function parameters, and revascularisation procedures. For primary prevention, we must emphasise that all participants were diagnosed with metabolic syndrome, and it was unclear whether the results could be applied to other populations. For secondary prevention, although the investigators reported on adverse events and serious adverse events, there is no indication that death (all‐cause or CVD‐related) was an outcome of the trial. Therefore, this review does not provide any understanding about the effect of periodontal therapy on risk of death for people with cardiovascular disease.

Clinicians should also understand that we only assessed the effect of periodontal therapy for the management of CVD. Timing of periodontal therapy was not assessed. For people with CVD, it is not safe to give active periodontal therapy to those have had a stroke within six months, or who have systolic blood pressure > 180 mmHg/diastolic blood pressure > 110 mmHg, fasting blood glucose > 7.0 mmol/L/HbA1c > 7.5%, platelet count < 60×10⁹/L, or international normalised ratio ≥ 1.5 to 2.0 (Renvert 2016; SP, CSA 2017). The results of this systematic review cannot be applied to these individuals.

It is unclear to what level of periodontitis severity the results apply. Lopez 2012 included participants who had least four sites with PD ≥ 4 mm. This could mean, for instance, that most participants had only four sites that were 4 mm deep, in which case, the potential for treatment to make a difference to local and systemic inflammation was limited, which might reduce the potential to see differences in CVD outcomes. Clinicians may be more interested in the effects of controlling severe periodontal inflammation on the systemic CVD outcomes.

Effectiveness and intensity of the intervention were not clearly described, which made it more difficult to assess the applicability of the evidence. The authors did not give detailed periodontal therapy protocols for the participants. Lopez 2012 mentioned that participants received periodontal treatment during the one‐year maintenance period, but the intensity was not specified.

The long‐term control of periodontal inflammation also remained unclear. Lopez 2012 reported a significant improvement (i.e. lower score) of all the periodontal parameters compared to baseline in the intervention and control groups three months after therapy. However, they described equivocally that "their values remained lower than at baseline, up to 12 months in both groups", from which we could speculate that the periodontal inflammation may not be well controlled at 12 months. PAVE 2008 did not report clinical periodontal parameters during one‐year follow‐up. Long‐term control of periodontal inflammation may require surgical or further active non‐surgical therapy to reach clinical endpoints of periodontal therapy and periodontal health. Without identified inflammatory control, the ability to discern the contribution of oral inflammation to the risk of cardiovascular and peripheral artery disease will remain unknown. One year following non‐surgical treatment, there could be participants with disease recurrence or re‐established periodontal plaque‐induced inflammation, confounding treatment outcomes in these RCTs. If the periodontal therapy does not alleviate the periodontitis effectively, it may be impossible to prove that the effects on CVD outcomes are caused by the periodontal therapy. Further studies addressing these flaws may improve methodological rigor and our ability to reach credible conclusions.

Quality of the evidence

Both Lopez 2012 and PAVE 2008 were assessed at high risk of bias (Figure 2). Data from PAVE 2008 were unusable due to particularly high attrition bias. Therefore, all the evidence was downgraded due to serious risk of bias.

Each analysis included only one study, thus none of the evidence was downgraded for inconsistency.

The number of events was mostly insufficient, reflected in the wide confidence intervals, thus all the evidence was downgraded for imprecision.

None of the evidence was downgraded for indirectness.

Due to the limited number of included studies, we did not generate a funnel plot to examine publication bias across studies, thus none of the evidence was downgraded for this.

Overall, all the evidence was graded as very low‐certainty, due to serious limitations of the two studies and the very imprecise results (Table 1; Table 2).

Potential biases in the review process

The protocol for this review underwent some minor changes (Differences between protocol and review). Some of the changes include a change in the definition of chronic periodontitis, to include people with a pocket depth of 4 mm or more. The follow‐up period was also changed to at least one year, and heart function parameters were included in the protocol as a secondary outcome. These changes may be justified, but could still be a source of bias in the review process.

Treatment for CVD might influence periodontal health. Current research has indicated the antimicrobial effect of statins to Porphyromonas gingivalis and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (Emani 2014). Magán‐Fernández 2014 concluded that intake of simvastatin is associated with increasing serum osteoprotegerin concentrations, and this could have a protective effect against bone breakdown and periodontal attachment loss. During the trial, investigators could not control the use of CVD drugs, which could influence final periodontal health in every group, and cause contamination.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Other reviews focusing on the preventive or treatment effects of periodontal therapy and oral health promotion for the management of cardiovascular disease have been published, which show inconsistent results for the effect of periodontal therapy on systemic markers (Ioannidou 2006; Lam 2010; Roca‐Millan 2018). The reviews are largely not comparable with this present review because of the inadequate follow‐up period.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is very limited evidence assessing the impact of periodontal therapy on the prevention of cardiovascular disease, and it is insufficient to generate any implications for practice. Further trials are needed before reliable conclusions can be drawn.

Implications for research.

There is a need for more randomised controlled trials (RCT) examining effects of periodontal therapy on both the primary and secondary prevention of CVD. We hope future studies will consider the following issues.

Participants: the target population of primary prevention could extend to patients with high blood pressure, diabetes, and hyperlipaemia etc.; in addition, it is important to stratify study participants according to the severity of the periodontitis and the number of remaining teeth. Again, confounding factors, such as acute inflammation, smoking, and diabetes should be carefully considered and controlled for.

Intervention and comparison: periodontal therapy can be a single‐ or multi‐regimen of scaling and root planing (SRP). Since the included studies only offered a single regimen, new studies could focus on the effect of multi‐regimen SRP in controlling periodontitis. Intensity of interventions should be clearly specified, including the plan for the maintenance therapy. The CONSORT non‐pharmacological intervention extension would be helpful here to guide authors in being explicit (Boutron 2017). In addition, multiple kinds of host modulation drugs could be chosen.

Outcomes: there is need for more studies reporting on all‐cause or cardiovascular‐related deaths and cardiovascular events observed after long‐term follow‐up of one year or more. Most of the studies identified with our search strategy were excluded on the basis of inadequate follow‐up period. As we mentioned in Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews, we found that the results might be different if short‐term results were incorporated into long‐term data. In addition, clinical periodontal data should be presented in order to allow judgement about whether the periodontal therapy would effectively control participants' chronic periodontitis.

Risk of bias: lack of compliance with study protocol and incomplete follow‐up of participants can be reduced, as suggested by PAVE 2008, if participants are followed up by a cardiologist. Although blinding of the participants and personnel is difficult to achieve in most periodontal RCTs, blinded outcome assessment should be achievable. Offering supragingival scaling to the control group might be useful for blinding participants.

Method of analysis: intention‐to‐treat analyses are encouraged when loss to follow‐up cannot be avoided.

PAVE 2008 is described as a 'pilot' study, and it would be helpful to extend this, since a pilot would not be expected to show a definitive desired outcome. We hope the research team will further explore effective methods to reduce the risk of bias, improve participant compliance, and decrease the loss to follow‐up.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 6 April 2020 | Amended | Minor edit to description of GRADE in 'Summary of findings' tables |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 7, 2011 Review first published: Issue 8, 2014

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 28 December 2019 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | One new study included, which provides very low‐certainty evidence relating to primary prevention. |

| 17 September 2019 | New search has been performed | Search updated. One new study identified for inclusion and one awaiting classification. Title changed. Author order on byline changed and new authors added. |

| 26 September 2017 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Conclusions remain the same as we did not identify any new studies for inclusion. |

| 23 September 2017 | New search has been performed | Search updated. No new studies included. New information added in background and discussion. |

Acknowledgements

For this update, we acknowledge Professor Helen Worthington, Laura MacDonald, and Anne Littlewood from the Cochrane Oral Health editorial base, Cochrane Oral Health editors Professor Ian Needleman and Professor Marco Esposito, peer reviewer Dr Mary Aichelmann‐Reidy, and copy editor Victoria Pennick.

We also thank Sichuan University and Luzhou government (2018 Sichuan University‐Luzhou Municipal Government Strategic Cooperation Research (2018CDLZ‐12)).

For previous versions of this review, the review authors would like to thank:

Cochrane Oral Health Information Specialist, Anne Littlewood, and Jane Ronson for designing the search strategies.

Professor Helen Worthington (Co‐ordinating Editor, Cochrane Oral Health), Laura MacDonald (Managing Editor), Luisa Fernandez Mauleffinch (Managing Editor), and Philip Riley (Methodologist) for assistance in the editorial process.

Professor Hongde Hu for helping with the title registration.

Professor Jing Li from the Chinese Cochrane Center, Prof Philip J Wiffen, Dr Marialena Trivella, and Dr Sally Hopewell from the UK Cochrane Centre, and Mrs Susan Furness from Cochrane Oral Health for their assistance and guidance in the conduct of the review.

Dr Yan Wang and Xiangyu Ma from West China College of Stomatology for their help with the revision of the review.

Dr Feng Li, Dr Qiushi Wang, Dr Chenyang Xiang, Dr Zhaoyang Ban, and Dr Wenhang Dong for their help with handsearching.

Professor Aubrey Sheiham for the Aubrey Sheiham Public Health & Primary Care Scholarship (2011) for supporting the review.

Dr Beck and Dr Couper (PAVE 2008) and Dr Ide (Ide 2003) who provided valuable information about the included study.

We would also thank Professor Zongdao Shi and Professor Longjiang Li for their special contribution to the first version of this Cochrane Review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Cochrane Oral Health's Trials Register search strategy

From July 2013, searches of the Cochrane Oral Health Group's Trials Register were undertaken using the Cochrane Register of Studies and the search strategy below:

#1 ((cardiovascular or myocardial or heart* or coronar* or "artery disease*" or angina or "transient ischaemic attack*" or atherosclerosis or arteriosclerosis or "peripheral arterial disease*" or cerebrovascular or stroke* or ischemia or "intercranial hemorrhage" or "intercranial haemorrhage" or thrombosis or thromboses or aneurysm* or embolism* or DVT):ti,ab) AND (INREGISTER) #2 ((periodont* or gingivitis or gingiva* or paradont*):ti,ab) AND (INREGISTER) #3 (#1 and #2) AND (INREGISTER)

Previous searches were undertaken using the Procite software and the search strategy below:

((cardiovascular or myocardial or heart* or coronar* or "artery disease*" or angina or "transient ischaemic attack*" or atherosclerosis or arteriosclerosis or "peripheral arterial disease*" or cerebrovascular or stroke* or ischemia or "intercranial hemorrhage" or "intercranial haemorrhage" or thrombosis or thromboses or aneurysm* or embolism* or DVT) AND (periodont* or gingivitis or gingiva* or paradont*))

Cochrane Oral Health’s Trials Register is available via the Cochrane Register of Studies. For information on how the register is compiled, see https://oralhealth.cochrane.org/trials

Appendix 2. Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) search strategy

#1. Exp CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASES #2. (myocardial or heart*) NEAR infarc* #3. heart NEAR (disease* or attack*) #4. (coronary NEAR (artery disease* or syndrome*)) #5. (angina pectoris OR "transient ischaemic attack*") #6. exp ATHEROSCLEROSIS #7. (atherosclerosis OR arteriosclerosis) #8. "peripheral arterial disease" #9. exp CEREBROVASCULAR DISORDERS #10. (stroke* or (ischemia NEAR brain*) OR (infarc* NEAR brain*) OR "intercranial haemorrhage*" or "intercranial hemorrhage*") #11. exp THROMBOSIS #12. (thrombosis or occlusion* or thromboses or aneurysm* or embolism*) #13. (DVT):ti,ab #14. ("atheromatous plaque" or atheromata*) #15. #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 #16. exp PERIODONTAL DISEASES #17. periodont* #18. (gingivitis or gingival*) #19. paradont* #20. #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 #21. exp PREVENTIVE DENTISTRY #22. Dental Care for Chronically Ill #23. exp PERIODONTICS #24. (scal* NEAR polish*) #25. (root* NEAR plan*) #26. (tooth NEAR scal*) OR (teeth NEAR scal*) OR (dental NEAR scal*) #27. (oral AND dental AND prophylaxis) #28. (gingivectomy OR gingivoplasty OR "subgingival curretage" OR subgingival curettage" OR "guided tissue regeneration") #29. Surgical flaps #30. "surgical flap*" #31. ((#29 OR #30) AND periodont*) #32. (periodont* NEAR (therap* OR treat* OR surger*)) #33. Oral Health #34. exp ORAL HYGIENE #35. (mouthrinse* OR mouth‐rinse* OR "mouth rinse*" OR mouthwash* OR mouth‐wash* OR "mouth wash*" OR toothbrush* OR "tooth brush*" OR tooth‐brush* OR floss*) #36. exp DENTIFRICES #37. (dentifrice* OR toothpaste* OR tooth‐paste* OR "tooth paste*") #38. Chlorhexidine #39. (chlorhexidine OR eludril OR chlorohex* or corsodyl) #40. exp ANTI‐BACTERIAL AGENTS #41. (antibiotic* or anti‐biotic* or antibacterial* or anti‐bacterial*) #42. exp TETRACYCLINES #43. (tetracycline* OR doxycycline* OR minocycline* OR roxithromycin* OR moxifloxacin* OR ciprofloxacin* OR metronidazole*) #44. (Periostat OR Atridox OR Elyzol OR PerioChip OR Arestin OR Actisite) #45. #21 OR #22 OR #23 OR #24 OR #25 OR #26 OR #27 OR #28 OR #31 OR #32 OR #33 OR #34 OR #35 OR #36 OR #37 OR #38 OR #39 OR #40 OR 41 OR #42 OR #43 OR #44 #46. #15 AND #20 AND #45

Appendix 3. MEDLINE Ovid search strategy

1. exp Cardiovascular diseases/ 2. ((myocardial or heart$) adj5 infarc$).mp. 3. (heart adj6 (disease$ or attack$)).mp. 4. (coronary adj6 (disease$ or syndrome$)).mp. 5. (angina or "transient ischaemic attack$").mp. 6. exp Atherosclerosis/ 7. (atherosclerosis or arteriosclerosis).mp. 8. "peripheral arterial disease".mp. 9. exp Cerebrovascular Disorders/ 10. (stroke$ or (ischemia adj3 brain$) or (infarc$ adj3 brain$) or "intercranial haemorrhage$" or "intercranial hemorrhage$").mp. 11. exp Thrombosis/ 12. (thrombosis or occulsion$ or thromboses or aneurysm$ or embolism$).mp. 13. DVT.ti,ab. 14. ("atheromatous plaque" or atheromata$).mp. 15. or/1‐14 16. exp Periodontal Diseases/ 17. periodont$.mp. 18. (gingivitis or gingiva$).mp. 19. paradont$.mp. 20. or/16‐19 21. exp Preventive Dentistry/ 22. Dental Care for Chronically Ill/ 23. exp Periodontics/ 24. (scal$ adj4 polish$).mp. 25. (root$ adj4 plan$).mp. 26. ((tooth adj6 scal$) or (teeth adj6 scal$) or (dental adj6 scal$)).mp. 27. (oral and dental and prophylaxis).mp. 28. (gingivectomy or gingivoplasty or "subgingival curretage" or "guided tissue regeneration").mp. 29. Surgical flaps/ 30. "surgical flap$".mp. 31. ((29 or 30) and periodont$).mp. 32. (periodont$ adj3 (therap$ or treat$ or surger$)).mp. 33. Oral Health/ 34. exp Oral Hygiene/ 35. (mouthrinse$ or mouth‐rinse$ or "mouth rinse$" or mouthwash$ or mouth‐wash$ or "mouth wash$" or toothbrush$ or "tooth brush$" or tooth‐brush$ or floss$).mp. 36. exp Dentifrices/ 37. (dentifrice$ or toothpaste$ or tooth‐paste$ or "tooth paste$").mp. [mp=title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word, unique identifier] 38. Chlorhexidine/ 39. (chlorhexidine or eludril or chlorohex$ or corsodyl).mp. 40. exp Anti‐bacterial agents/ 41. (antibiotic$ or anti‐biotic$ or antibacterial$ or anti‐bacterial$).mp. 42. exp Tetracyclines/ 43. (tetracycline$ or doxycycline$ or minocycline$ or roxithromycin$ or moxifloxacin$ or ciprofloxacin$ or metronidazole$).mp. 44. (Periostat or Atridox or Elyzol or PerioChip or Arestin or Actisite).mp. 45. 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 or 36 or 37 or 38 or 39 or 40 or 41 or 42 or 43 or 44 46. 15 and 20 and 45

This subject search was linked to the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy (CHSSS) for identifying randomised trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity‐maximising version (2008 revision) as referenced in Chapter 6.4.11.1 and detailed in box 6.4.c of The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011] (Lefebvre 2011).

1. randomized controlled trial.pt. 2. controlled clinical trial.pt. 3. randomized.ab. 4. placebo.ab. 5. drug therapy.fs. 6. randomly.ab. 7. trial.ab. 8. groups.ab. 9. or/1‐8 10. exp animals/ not humans.sh. 11. 9 not 10

Appendix 4. Embase Ovid search strategy

1. exp Cardiovascular diseases/ 2. ((myocardial or heart$) adj5 infarc$).mp. 3. (heart adj6 (disease$ or attack$)).mp. 4. (coronary adj6 (artery disease$ or heart muscle ischemia)).mp. 5. (angina pectoris or "transient ischaemic attack$").mp. 6. exp Atherosclerosis/ 7. (atherosclerosis or arteriosclerosis).mp. 8. "peripheral arterial disease".mp. 9. exp Cerebrovascular Disorders/ 10. (stroke$ or (ischemia adj3 brain$) or (infarc$ adj3 brain$) or "inter cranial haemorrhage$" or "inter cranial hemorrhage$").mp. 11. exp Thrombosis/ 12. (thrombosis or occlusion$ or "occlusive cerebrovascular disease" or aneurysm$ or embolism$).mp. 13. DVT.ti,ab. 14. ("atherosclerotic plaque" or atheroma$).mp. 15. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 16. exp Periodontal Diseases/ 17. periodont$.mp. 18. (gingivitis or gingiva$).mp. 19. paradont$.mp. 20. 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 21. exp Preventive Dentistry/ 22. Dental Care for Chronically Ill/ 23. exp Periodontics/ 24. (scal$ adj4 polish$).mp. 25. (root$ adj4 plan$).mp. 26. ((tooth adj6 scal$) or (teeth adj6 scal$) or (dental adj6 scal$)).mp. 27. (oral and dental and prophylaxis).mp. 28. (gingivectomy or gingivoplasty or "subgingival curretage" or "subgingival curettage" or "guided tissue regeneration").mp. 29. Surgical flaps/ 30. "surgical flap$".mp. 31. (29 or 30) and periodont$.mp. 32. (periodont$ adj3 (therap$ or treat$ or surger$)).mp. 33. Oral Health/ 34. exp Oral Hygiene/ 35. (mouthrinse$ or mouth‐rinse$ or "mouth rinse$" or mouthwash$ or mouth‐wash$ or "mouth wash$" or toothbrush$ or "tooth brush$" or tooth‐brush$ or floss$).mp. 36. exp Dentifrices/ 37. (dentifrice$ or toothpaste$ or tooth‐paste$ or "tooth paste$").mp. 38. Chlorhexidine/ 39. (chlorhexidine or eludril or chlorohex$ or corsodyl).mp. 40. exp Anti‐bacterial agents/ 41. (antibiotic$ or anti‐biotic$ or antibacterial$ or anti‐bacterial$).mp. 42. exp Tetracyclines/ 43. (tetracycline$ or doxycycline$ or minocycline$ or roxithromycin$ or moxifloxacin$ or ciprofloxacin$ or metronidazole$).mp. 44. (Periostat or Atridox or Elyzol or PerioChip or Arestin or Actisite).mp. 45. 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 or 36 or 37 or 38 or 39. or 40 or 41 or 42 or 43 or 44 46. 15 and 20 and 45

The above subject search was linked to adapted version of the Cochrane Embase Project filter for identifying RCTs in Embase Ovid (see http://www.cochranelibrary.com/help/central‐creation‐details.html for information):

1. Randomized controlled trial/ 2. Controlled clinical study/ 3. Random$.ti,ab. 4. randomization/ 5. intermethod comparison/ 6. placebo.ti,ab. 7. (compare or compared or comparison).ti. 8. ((evaluated or evaluate or evaluating or assessed or assess) and (compare or compared or comparing or comparison)).ab. 9. (open adj label).ti,ab. 10. ((double or single or doubly or singly) adj (blind or blinded or blindly)).ti,ab. 11. double blind procedure/ 12. parallel group$1.ti,ab. 13. (crossover or cross over).ti,ab. 14. ((assign$ or match or matched or allocation) adj5 (alternate or group$1 or intervention$1 or patient$1 or subject$1 or participant$1)).ti,ab. 15. (assigned or allocated).ti,ab. 16. (controlled adj7 (study or design or trial)).ti,ab. 17. (volunteer or volunteers).ti,ab. 18. trial.ti. 19. or/1‐18 20. (exp animal/ or animal.hw. or nonhuman/) not (exp human/ or human cell/ or (human or humans).ti.) 21. 19 not 20

Appendix 5. CINAHL EBSCO search strategy