Abstract

Approximately 450 million people, many of whom live in poverty and are from low and middle-income countries (LMICs), experience serious mental health challenges. Children in sub-Saharan Africa comprise half of the total regional population, yet existing mental health services are severely under-equipped to meet their needs and evidence-based practices (EBPs) are scarce. In Uganda, one in five children present mental health challenges, including disruptive behavior disorders. Guided by the Practical, Robust Implementation and Sustainability (PRISM) framework, this paper describes the strategies by which we have engaged community and government partners to invest in a collaborative, longitudinal study in Uganda aimed at improving youth behavioral health outcomes by testing a collaboratively adapted EBP. We emphasize that implementation scientists should be prepared and willing to invest time and effort engaging key stakeholders and sustain relationships through a full range of collaborative activities; ensure that their science meets a felt need among the stakeholders; and translate their research findings rapidly into accessible and actionable policy recommendations. Finally, we highlight that collaboration with global communities and governments plays a critical role in the adaptation, uptake, scalability, and sustainability of EBPs, and that the process of engagement and collaboration can be guided by conceptual frameworks.

Keywords: Child behavioral health, Implementation science, Global health, Community engagement, Sub-Saharan Africa

1. Introduction

Approximately 450 million people, many of whom live in poverty and are from low and middle-income countries (LMICs), experience serious mental health challenges (Roberts et al., 2014). Children in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) comprise half of the total regional population, yet existing mental health services are severely under-equipped to meet their needs (Kieling et al., 2011; Roberts et al., 2014). The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 1 in 5 children in SSA struggle with a serious mental health issue (WHO, 2005). Uganda (one of the poorest countries in SSA) reports that 12 to 29% of children present mental health symptoms when screened in primary care clinics (Nalugya, 2004). Given the large numbers of children in Uganda, child disruptive behavior disorders (DBDs), if untreated, are a particularly serious concern as they commonly persist through adolescence and adulthood with negative outcomes, including academic problems, social impairment, a higher incidence of chronic physical problems, unemployment and legal problems, and substance abuse and violence among adults (Belfer, 2008; Bellis et al., 2013; Burke et al., 2004; Kazdin, 1995; Lendingham, 1999; Loeber et al., 2000a, 2000b; Washburn et al., 2008). Studies have identified specific risk factors for increased incidence of DBDs among children, including poverty, low parental educational attainment, maternal depression, harsh parenting, poor parent-child relationship, stress, and orphanhood (Curley et al., 2016; Nabunya and Ssewamala, 2014; Ssewamala et al., 2015).

Six SSA countries, namely Uganda, Nigeria, South Africa, Ethiopia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Kenya, have reported high DBD prevalence rates ranging from 12% to 33% (Apkan et al., 2010; Ashenafi et al., 2001; Cortina et al., 2012; Liang et al., 2002). Given the serious consequences of failing to intervene as DBDs emerge, it is imperative that effective and scalable solutions are discovered, while simultaneously recognizing the challenges facing these countries in meeting the educational and mental health care needs of their large youth populations. Addressing the unmet disruptive behavioral health challenges is also emerging as a serious policy concern as DBDs may undermine the ability of the “next generation” to contribute to the success of LMIC contexts.

This policy concern is grounded in the fact that in Uganda, the focus of this paper, children make up about half (56%) of the total population (compared to 20% in the US) (UNICEF, 2015), and they most often present with multiple simultaneous physical, mental health, and educational challenges (Population Reference Bureau, 2009; UNICEF, 2015). Ugandan children live in disadvantaged communities with high rates of chronic poverty (38%), domestic violence (30%), physical violence toward children (80%), depression (33 to 39%), malaria (70 to 80%), and HIV or AIDS (6%) (Brownstein et al., 2005; Koenig et al., 2003; Naker, 2005; Ovuga et al., 2005; WHO, 2009). The country also has a significant number of orphans (Belfer, 2008; Ovuga et al., 2005). These prevalence rates translate into staggering numbers of children in need (e.g. 50% of population under 15 in Uganda), with systems not equipped to meet the need (Kieling et al., 2011; Roberts et al., 2014). Hence, for DBDs to be addressed, poverty and family economic capacities, family and community safety, as well as health and mental health co-morbidities must be taken into account in any evidence-based practice (EBP) considered for implementation and scale-up.

Although effective interventions for the treatment of DBDs among youth have been tested in high-poverty and high-stress communities in developed countries, and are potentially applicable for widespread dissemination in LMICs, most of these evidence-based practices (EBPs) have not been utilized in SSA, a region heavily impacted by poverty, diseases including HIV/AIDS, and violence. However, these EBPs cannot be effectively disseminated without paying close attention to the local context. Hence, implementation science has a critical role to play in the process. Since most interventions and implementation strategies are empirically developed and transferred from developed to developing regions, community engagement in the adaptation and implementation of these interventions is a necessity (Baptiste et al., 2006, 2007; Kelly et al., 2000). Guided by PRISM framework (Feldstein and Glasgow, 2008), we describe the strategies by which we have engaged communities and government structures to invest in a collaborative, longitudinal study titled “SMART Africa-Uganda,” aimed at improving youth behavioral health outcomes.

2. Background

2.1. Child mental health policy context in SSA

Child mental health policy and service gaps are wide in SSA (Table 1). However, there is momentum across Africa to meet the mental health needs of children to prevent costly adult psychiatric disorders and reap the economic dividend resulting from an educated, physically and emotionally healthy generation of youth (referred to as the African “youth bulge”). Most recently, the Ugandan government developed a National Development Plan and Vision 2040, which sets as a primary goal the reduction of burden of mental health disorders and the improvement of the quality of life of children and adolescents affected by behavioral health challenges. Communities and families are viewed as important contributors to positive child mental health.

Table 1.

Mental Health System Capacity in Africa (WHO, 2014).

| WHO-AIMS Domain: Policy/ leaislation | African Region | Ghana | Kenya | South Africa | Uganda | ||||

| World bank income classification | NA | Lower middle | Lower middle | Upper-middle | Low income | ||||

| Mental health (MH) policy | 44% | 1996 | (Draft, 2012) | 1997 | (Draft, 2005) | ||||

| Mental health plan | 67% | 2007 | 1994 | 2009 | 2010 | ||||

| Mental health legislation | 44% | 2012 | 1991 | 2002 | (Reviewed 2012) | ||||

| National child & adolescent MH Policy | 6% | No | No | (Guideline only 2002) | (Guideline only 2013) | ||||

| WHO-AIMS: Human Resources | % 1 M (SD) | % 1 M (SD) | % / M (SD) | % / M (SD) | % / M (SD) | ||||

| Gov expenditure on MH (%of health expenditures) | 1.60% | 2.00% | – | – | – | ||||

| Gov expenditures on mental hospitals as a% of total expenditures on mental health | 71% | – | – | – | |||||

| Psychiatrists working in mental health sector * | 0.24 (0.49) | 0.07 | 0.19 | 0.27 | 0.09 | ||||

| Nurses working in mental health sector * | 5.73 (22.81) | 2.47 | – | 9.72 | 0.76 | ||||

| Social workers working in mental health sector * | 0.12 (0.22) | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.39 | – | ||||

| Psychologists working in mental health sector * | 0.39 (0.93) | 0.04 | – | 0.31 | 0.02 | ||||

| WHO-AIMS: MH Services in Primary Care | |||||||||

| Mental health outpatient facilities * | 0.50 (1.27) | 0.16 | 6.85 | 0.08 | |||||

| Mental health day treatment facilities * | 0.07 (0.18) | 0.01 | – | 0.16 | 0 | ||||

| Community residential facilities * | 0.01 (0.03) | 0.01 | – | 0.12 | 0 | ||||

| Mental hospitals * | 0.06 (0.20) | 0.02 | – | 0.12 | 0 | ||||

| Mental Health Professionals in Schools | – | 0% | 0% | Unknown | 0% | ||||

Uganda is one of a few SSA countries which have child and adolescent mental health (CAMH) policy guidelines developed. Ugandan policy recognizes the burden and impact of child mental health disorders on children, their families and communities. There is also a clear recognition that the burden is growing and scaling mental health promotion, prevention and interventions is a high priority.

Guidance documents developed in 2013 and re-released in the National Development Plan and Vision 2040 outline objectives that have guided the development of the proposed scale-up study. The Plan prioritizes the engagement of communities to increase their support for child mental health promoting programs and services with the understanding that policymakers, families, schools and communities need to increase their knowledge regarding the influences of families, schools and communities on child mental health. Next, Uganda CAMH policy prioritizes building capacity of existing human resources across sectors to increase access for children. Two types of settings and associated human resources are natural fits for serving children, specifically community health care settings and schools. Uganda government officials have identified Village Health Teams (VHT) as existing workforce options within the Ministry of Health. VHTs serve as the community’s initial point of contact for health. VHTs are community health outreach workers who are considered an integral part of national health structure. VHT members tend to be stable members of their communities, residing in the same community for many years (Ministry of Health of Uganda, 2012). The Ministry of Education has also organized, trained and supported parent leaders (family peers and family-run councils) as part of each primary school. The task-shifting approach adopted by the SMART Africa team for the EBP delivery capitalizes on the workforce and lay community members that the government has already invested in, by choosing community health workers and parent peers to be trained for the intervention (see Section 2.4.2 for more details). Thus, the first important point here is the need for globally focused implementation scientists to deeply understand the current policy context and future priorities before trying to move a robust research agenda forward. This is an example of the type of information regarding the external environment needed, according to the PRISM framework that can help with successful implementation and potential sustainability.

2.2. Importance of stakeholder engagement

Community engagement is critical in ensuring the success and sustainability of both cultural adaptation and intervention implementation (Baptiste et al., 2007; Kelly et al., 2000). Most interventions and implementation strategies are empirically developed and transferred from developed to developing regions, which makes community engagement in the adaptation of these interventions a necessity (Baptiste et al., 2006). Community engagement leads to a sense of ownership by local stakeholders (Baptiste et al., 2007; Mellins et al., 2014) and increases the acceptability, efficacy, cultural and contextual sensitivity, and capacity for wider scale use (McKay and Paikoff, 2007; Mellins et al., 2014).

Community engagement and partnerships in many studies have been associated with community-based participatory research (CBPR) methods. CBPR is defined as “providing direct benefit to participants either through direct intervention or by using the results to inform action for change” (Israel et al., 1998, p. 175). Moreover, community collaborative research emphasizes the intensive and ongoing participation and influence of community members in building knowledge (Israel et al., 1998). Collaboration between researchers and community members facilitate the identification of concerns and acknowledge the importance of community-level knowledge and resources (Minkler and Wallerstein, 2003; Secrest et al., 2004). McKay et al. (2014) have used CBPR methods to engage the community and stakeholders to identify salient issues related to the target population, their needs, family life, risk factors; and to get feedback on program materials and feasibility concerns. CBPR methods have also been used to refine and adapt an intervention, and to build consensus about intervention goals and curriculum development among community members and stakeholders (Madison et al., 2000; McKay and Paikoff, 2007; Mellins et al., 2014). Thus, using a CBPR approach allows the intervention to be adapted to meet organizational and external environments, recipients’ characteristics and infrastructure outlined by PRISM framework that will promote implementation and sustainability.

2.3. Using the practical, robust implementation and sustainability model (PRISM) to understand contextual influences on implementation and scale-up

Serious consideration should be given to context-specific influences within SSA, such as high levels of stigma associated with mental illness (Kleintjes et al., 2010; Roberts et al., 2014), skepticism of professionalized responses in contrast to community or religious solutions (e.g. mental health advice sought from prayer camps, religious leaders or healers) (Laugharne et al., 2009; Roberts et al., 2014; Sorsdahl et al., al.,2009), the large number of youth orphaned by HIV and other health epidemics (Belsey and Sherr, 2011), the lack of economic opportunities for African youth (Curley et al., 2016; Nabunya and Ssewamala, 2014; Ssewamala et al., 2008; Ssewamala and Ismayilova, 2009; Ssewamala et al., al.,2012; Ssewamala et al., 2015), as well as the current policy landscape. Hence, adapting child mental health EBPs for implementation in SSA countries requires thoughtful consideration of individual- and system-level factors (Hirschhorn et al., 2007; Kisia et al., 2012; Schackman, 2010; Wittkowski et al., 2014). Interventions developed in academic isolation too often fail to address the real-world constraints of settings in which they will be used – insufficient resources, limited workforce capacity, and failure to partner with funders and policymakers (McKay and Paikoff, 2007).

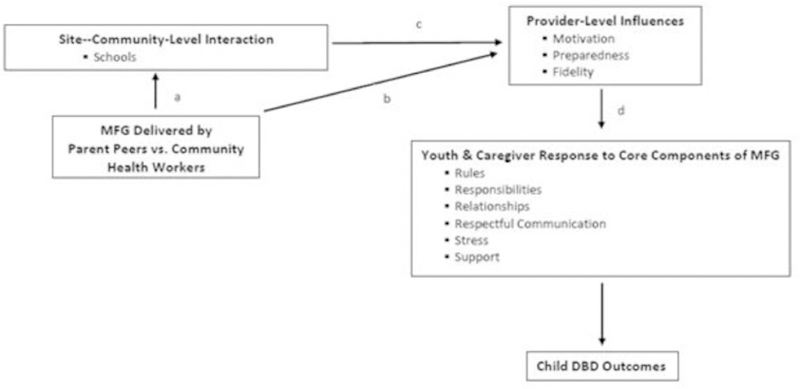

We draw upon PRISM, which is a practical and comprehensive implementation framework that integrates aspects of diffusion of innovation and models for quality improvement (Feldstein and Glasgow, 2008). PRISM emphasizes: (a) organizational perspectives on an intervention (e.g., feasibility, adaptability, barriers from the perspective of schools); (b) external environment (e.g., community resources, policy context); (c) recipients’ characteristics (intervention facilitator and caregiver responses); and (d) implementation and sustainability infrastructure (training and supervision supports for intervention facilitators). PRISM provides a framework to study the interaction of interventions with the characteristics of multi-level contexts and factors that may influence uptake, implementation, integration and youth outcomes (youth and adult caregiver response, provider preparedness, motivation and fidelity, community level support) as illustrated in the figure below for our work testing an EBP in Uganda.

2.4. How to engage community stakeholders and policymakers for sustainable and impactful child mental health research in SSA context: Uganda as a case example

In this paper, we use our scale-up study in Uganda that is part of our NIMH-funded SMART Africa (Strengthening Mental health And Research Training in sub-Saharan Africa) Center (U19MH110001) to illustrate how community stakeholders and policymakers can be extensively involved throughout the process of conducting a child mental health focused research study. The scale-up longitudinal experimental study, referred to as SMART Africa-Uganda, uses the multiple family group (MFG) intervention, an evidence-based manualized intervention for families of children with disruptive behaviors. Also listed in the National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices (NREPP), the 16-session intervention was developed in intensive collaboration with parents and service providers in the U.S. (Chacko et al., 2015; Gopalan et al., 2014a, 2014b; McKay et al., 2011).

MFG is a hybrid of group and family interventions, rooted in several theories including family systems theory, structural family theory and social learning theory with elements of psychoeducation and social group work (McKay et al., 2011). It involves 6 to 8 families in the U.S., with at least two generations of a family present in each session. Content and practice activities foster learning and interaction both within and between families (McKay et al., 2011). The intervention tested in randomized control trials, has been found to significantly reduce child behavior problems and improve family functioning (Chacko et al., 2015; Gopalan et al., 2014a, 2014b; McKay et al., 2011).

The study uses a mixed methods hybrid type II effectiveness implementation design that allows to concurrently test effectiveness and examine implementation (Curran et al., 2012; Landes and Curran, 2019). In the SMART Africa-Uganda study, this design is used to test the effectiveness of MFG, a family strengthening EBP, aimed at improving child disruptive behavioral challenges in Uganda while concurrently examining implementation. The study objectives are:

To examine short-term and longitudinal outcomes associated with the MFG

To compare the uptake and implementation of MFGs by trained parent peers versus CHWs

To elucidate multi-level factors that influences uptake, implementation and youth outcomes

Schools (n = 30) are randomly assigned to 3 study conditions: 1) MFG delivered by trained parent peers (n = 10 schools); 2) MFG delivered by CHWs (n = 10 schools); or, 3) Comparison: Mental health materials (n = 10 schools). Data will be collected at baseline, 8 and 16 weeks, and 6-month follow-up. The effectiveness outcomes include child disruptive behaviors, family functioning and support, parenting stress, and child mental health. Data are collected from children and caregivers. Implementation outcomes include facilitator knowledge and skills, intervention fidelity, perceptions on sustainability, barriers and facilitators to implementation and feasibility. Data are collected from facilitators, caregivers, and school head teachers (see Ssewamala et al., 2018 for further details on the study design). Implementation strategies tested centered on the choice of deliverers (health workers relative to parent peers).

So far, the study team has completed intervention delivery in four out of the 20 primary schools. In two of these schools, the intervention was delivered by CHWs and in the other two by parent peers. The team has recently rolled out the intervention in a new set of four schools.

Simultaneously, the study also aims at informing policy, acknowledging government structures as key stakeholders who need to be engaged early on in the process to promote system-level changes. For this purpose, the project uses three key strategies that elicited information to align the adapted EBP with the cultural context and convey this learning to collaboration stakeholders. The structure of these strategies and the information sought was guided by PRISM.

Collaborative process with community stakeholders

Training of key players (task-shifting)

Policymaker engagement

More specifically, meeting activities and agendas tapped knowledge related to: (a) organizational perspectives on the adapted EBP; (b) alignment with community resources and policy context in the external environment; (c) characteristics of MFG facilitators and caregivers; and (d) available infrastructure for implementation and sustainability (Fig. 1). More specifically, within the collaborative process, the content and delivery processes were altered to align with potential facilitators (implementers) of the program. Further, policy-level engagement and collaboration across all phases of the study was seen as a means to potentially influence able support for sustaining the EBP via new mental health legislation and government investments.

Fig. 1.

Multi-level influences on Multiple Family Group (MFG) implementation and child outcomes.

2.4.1. Collaborative process with community stakeholders

The research team organized a set of meetings with head teachers (the equivalent of school director in Uganda), teachers, religious leaders, parent-teacher association (PTA) members, parent peers and community health workers since the onset of the study.

2.4.1.1. Initial meetings with key stakeholders.

Meetings were held with head teachers (n = 29) to introduce the study and the main concepts of the MFG intervention, including the transferability of the intervention’s key components. The two principle investigators led discussions around what “behavioral challenges” meant to teachers and how they were handled in the school context. Some of the questions asked included: “If a child is not behaving well in school, or not behaving as well as they should, how do you help them?”; “What do you do if a child is in trouble in school?”; “How many children with disruptive behaviors would you say you have in a class?”; and “At what age/class do they mostly like to manifest?” Moreover, the six core practice constructs of the MFG intervention (rules, responsibilities, respectful communication, relationships, stress, social support) were presented to the head teachers and they were encouraged to discuss how relevant each of these concepts were to families in the Ugandan context. The follow-up meeting occurred a few months later with 27 head teachers, 60 teachers, and two district education officers (DEOs) to further discuss other study related topics, including the age group to be targeted and appropriate incentives to be offered. These meetings were critical in gaining information related to characteristics of potential implementers of the adapted EBP, as well as school organizational perspectives on the MFG intervention.

2.4.1.2. Follow-up meeting with community stakeholders.

Two consecutive meetings, one with head teachers and teachers, and the other with PTA caregivers from 30 primary schools (n = 90) were scheduled in order for the team to receive further feedback on the intervention adapted with the input from the stakeholders during the initial meetings. During the meeting with PTA members, the research team introduced the overall goal and design of the research study. The team also asked for their feedback on the age group targeted, when the intervention should be delivered, and their thoughts about the delivery of the intervention by community health workers and parent peers. In both meetings, the attendees engaged in a guided discussion of all the suggested sessions and topics as well as all the activities/exercises that were developed by the research team. The attendees also helped the research team think through potential barriers to participation. Again, guided by the PRISM framework, information from potential implementers (who could be trained as parent peers), as well as recipients (caregivers who could participate in the study) was systematically gathered.

2.4.1.3. Stakeholder accountability meeting.

The research team facilitated a stakeholder accountability meeting during the Center’s 3rd Annual Conference on Child Behavioral Health in SSA. Head teachers and teachers from the thirty schools participating in the study, as well as community health workers and parent peers recruited for the study to deliver the MFG intervention were invited to participate in the meeting. The purpose of the meeting was to report on study progress as the project entered its third year. The team also reported findings from the study’s baseline data on the prevalence of behavioral challenges among children participating in the study. After the team shared the next steps, stakeholders had the opportunity to ask questions and give feedback. As per PRISM recommendations, the team solicited continuous feedback from organizations and individuals, as well as additional checks on study alignment with external resources and infrastructure.

2.4.2. Training of key players (task-shifting)

The global recommendations propose task shifting as a method of “strengthening and expanding the health workforce to rapidly increase access to HIV and other health services.” (WHO, 2008). Task shifting is defined as the process whereby tasks are moved from specialized or well-trained providers to health workers or a new cadre of workers with shorter training and fewer qualifications. The goal of such re-organization of the workforce is to make more efficient use of existing human resources and ease bottlenecks in service delivery (WHO, 2008). The task-shifting approach is promising as a cost-efficient and feasible model for SSA countries since it provides support for lay workers and peers that already exist in health and education systems, and utilizes them to implement the intervention for parents and their children. This study tests two task-shifting approaches (task-shifting intervention skills to community health workers and parent peers). It is possible that testing a task-shifting large-scale implementation strategy in low-resource SSA settings can facilitate “reverse innovation” (Bhatti et al., 2017). In other words, effective services and implementation strategies identified in developing countries may facilitate new innovations to address similar CAMH disparities in US populations or in other developed countries.

For this study, we have drawn upon a family-focused, community- based and task-shifting implementation approach of EBP delivery (MFG intervention) that has been tested in the US, South Africa and Uganda for youth evidencing DBDs. This scale-up study focuses on child mental health service development for school-age children (8–13 years old) in schools through two approaches to workforce development (i.e., task-shifting the EBP implementation skills to community health workers and parent peers that are current parts of the National Health and primary school structures). These decisions were informed by prior stakeholder meetings and information gained that was guided by PRISM.

For the purpose of the study, 60% peers and 60 community health workers have been recruited. Training for parent peers and community outreach health workers are conducted separately. Training focuses on strategies to enhance engagement and motivation, group facilitation skills and processes specific to MFGs. At the end of the MFG training, a knowledge and skills assessment test (KSAT) is administered to assess mastery of the content (live competence demonstrations and knowledge questions read aloud to facilitators). The criteria of mastery for the KSAT is set at 80%. During the MFG implementation period, facilitators receive ongoing supervision while the MFGs are in progress. Given that the study is rolled out in phases, 48 facilitators (24 CHWs and 24% peers) have been trained so far to deliver the intervention in eight schools.

2.4.3. Policymaker engagement

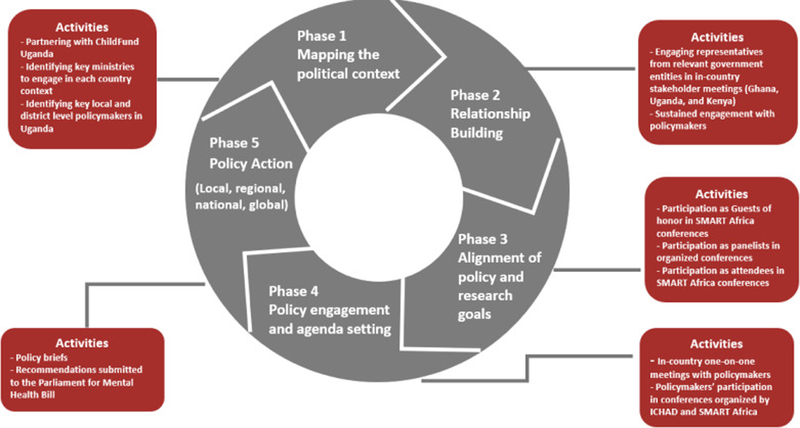

Since the launch of the SMART Africa Center in May 2016, the team has widely engaged policymakers at local and national levels in Uganda (See Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

SMART Africa Approach to Policy Impact.

2.4.3.1. Mapping the policy context.

As a first step, we partnered with two in-country organizations already engaged with policymakers in their respective roles, ChildFund International in Uganda (ChildFund) and Reach the Youth Uganda (RTY). ChildFund has engaged in policy work at the national level with different government ministries concerning child and adolescent wellbeing. RTY has worked closely with district and regional level policymakers as well as different government ministries. The SMART Africa team had a series of meetings with both partners to identify existing connections to the policymakers and identify key ministries that would be critical to engage. These meetings were critically important to situate potential findings within the needs and constraints of the external policy environment, identified as critical within the PRISM framework.

2.4.3.2. Relationship building.

The First Lady and Minister of Education and Sports officiated the 1st Annual Conference on Child Behavioral Health in Sub-Saharan Africa on July 12, 2016 held by the SMART Africa team to contribute to its capacity building efforts. During her keynote speech, she emphasized the importance of addressing CAMH in health programming and voiced the government’s commitment to developing a solid policy framework for the betterment of Ugandan children, working in tandem with colleagues across the African continent. In addition, the SMART Africa team, along with the Program Chief at NIMH, facilitated high-level discussions with the Minister for Health in Kampala, Uganda. During the meeting, the team shared findings from previous research on CAMH in SSA. The Minister presented government initiatives focused on addressing needs and emphasized the desire to use scientific evidence to formulate and guide mental health services. This information proved critical as the team considered existing infrastructure to support implementation and ultimately sustainability of the MFG, if findings warrant.

2.4.3.3. Alignment of policy and research goals.

As part of the continuous efforts to engage policymakers, the SMART Africa team invited the Deputy Speaker of Parliament to officiate the 2nd Annual Conference on Child Behavioral Health in Sub-Saharan Africa on August 1, 2017. In his keynote speech, he underscored the importance of using scientific evidence to inform policies and the dire need for generating evidence-based programming to address CAMH in Uganda. At the end of the 2nd Annual Conference, the SMART Africa team was joined by NIMH representatives as well as ChildFund International to meet with the Speaker of Ugandan Parliament and over 20 Members of Parliament representing several parliamentary committees such as health, education, gender, social welfare, children and youth. The meeting participants discussed the possibility of the SMART Africa team working with the Parliament of Uganda to design a CAMH Policy for the country and to collaborate on other health and education related issues. This meeting resulted in follow-up meetings with the Chairperson of the Uganda Parliamentary Forum for Children as well as an invitation by the Parliament for the SMART Africa team to contribute to the Mental Health Care Bill. This is an example of how study findings may potentially influence the external resource environment, a pillar of the PRISM framework.

The 3rd year’s conference hosted the State Minister for Higher Education and the State Minister for Gender, Labor and Social Development (Youth and Children Affairs). In his speech, the State Minister for Higher Education emphasized the importance of investing in young people, their education, and their wellbeing. The State Minister for Gender, Labor, and Social Development called upon local governments in the region, NGOs, researchers and academicians to invest in children and youth programs and policies, including ones explicitly focused on behavioral health to ensure healthy development of young people, and their contribution to the demographic dividend and overall economic growth and development.

2.4.3.4. Policy engagement and agenda setting.

SMART Africa and ICHAD hosted a meeting in St. Louis to discuss amending the Uganda Mental Health Bill. The meeting was attended by Ugandan officials including the Chairman of the Health Care Committee (Parliament of Uganda), and local leaders from Masaka district including the Mayor of Masaka Municipality and the Masaka District Local Council (LCV) Chairman. The meeting focused on efforts to amend the Uganda Parliament’s current mental health bill to encompass more evidence- based strategies, and ultimately impact future in-country practices surrounding mental health care.

The 3rd Annual Conference on Child Behavioral Health in Sub-Saharan African in Masaka, Uganda (July 30th–August 1st, 2018), presented another opportunity for policy engagement. The Masaka District Mayor and the LCV Chairman of the Masaka District attended the conference, contributing to discussions from a policymaker perspective. This conference allowed for the enhancement of the external environment to make maximum use of the study findings.

2.4.3.5. Policy action.

As a result of their intensive and sustained engagement with policymakers, the SMART Africa Center and ICHAD were invited to contribute to the Mental Health Care Bill. Relatedly, the team also published a 3-series policy brief (https://sites.wustl.edu/smartafrica/pub/).

a. Invitation to make recommendations to the Mental Health Bill:

The bill, assigned to the Health Care Committee, was formulated in 2014 when Uganda government officials decided that it was necessary to revise the outdated Mental Health Act passed in 1964. Contributing to the bill has provided an incredible opportunity for SMART Africa study to influence policy at the national level. The team proposed three main amendments to the bill: 1) include specific interventions and preventative measures to address mental health issues among youth and adolescents; 2) outline how mental health care could be further integrated into already-existing health care systems to increase access; and 3) include poverty prevention supports such as Child Savings Accounts since it is evident that poverty significantly contributes to mental health challenges. In addition to recommending amendments to the bill, the meeting provided the St. Louis and Uganda SMART Africa and ICHAD teams with the opportunity to learn more about the process of developing and amending a bill.

b. Policy briefs:

The SMART Africa team, in collaboration with the International Center for Child Health and Development (ICHAD), ChildFund International and the Clark Fox Policy Institute at the Brown School at Washington University in St. Louis generated three-part policy briefs regarding the importance of CAMH care in Uganda. The policy briefs explicitly outline policy recommendations and the evidence-based rationales behind those recommendations. The briefs were distributed to members of the Uganda Parliament during the Mental Health Bill Parliamentary Meeting in March 2018.

c. Mental Health Bill parliamentary meeting:

In March 2018, the Lead Principal Investigator (PI) of the study appealed to the Uganda Parliament in an effort to generate more child-specific laws within the Mental Health Bill of 2014. This was a particularly important pursuit, since 56% of the population is comprised of youth and adolescents experiencing several stressors associated with poor mental health such as chronic poverty, witnessing domestic violence, physical violence, depression, malaria and HIV/AIDS. The Lead PI met with the Speaker of Parliament in her office regarding the Bill along with the Chairperson of the Health Committee of Parliament, County Director of ChildFund International and the Executive Director of Reach the Youth Uganda. The team also submitted a formal proposal to parliament to guide the amendment process and detail scientific evidence on effective interventions.

4. Discussion

In this paper, we described the process by which the research team engaged in systematic and collaborative engagement with communities and government structures, using our ongoing longitudinal SMART Africa study in Uganda as a case example. We laid out three strategies that the study has used to facilitate the process, namely collaborative process with community stakeholders, training of key players (task-shifting), and policymaker engagement.

Intensive engagement increases the likelihood of success and sustainability of both cultural adaptation and intervention implementation (Baptiste et al., 2007; Kelly et al., 2000). Most interventions and implementation strategies are empirically developed and transferred from developed to developing contexts, which makes local stakeholder engagement in the adaptation of these interventions a necessity (Baptiste et al., 2006). Collaboration increases a sense of ownership by local stakeholders (Baptiste et al., 2007; Mellins et al., 2014) and improves the potential for acceptability, efficacy, cultural and contextual sensitivity as well as uptake and scalability (McKay and Paikoff, 2007; Mellins et al., 2014).

This case example illustrates the level of time and effort that community and policy engagement requires. The current study has built upon the existing infrastructure and partnerships that have been created on the ground over the last fifteen years by one of the study Principal Investigators through his research center (ICHAD). The research team leveraged these connections to expand further its reach and systematically engaged teachers, families, religious leaders, PTA members, and community members. The team has also systematically engaged local and national-level policymakers. Stakeholder engagement and participation need sustained nurturing through investing in relationships, maintaining trust, constantly working with the formal and informal leadership, and renewing commitment from community organizations and leaders to create processes for mobilizing the community (Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium, 2011; McKay and Paikoff, 2007; Mellins et al., 2014). Hence, implementation scientists should be prepared and willing to invest time and effort engaging key stakeholders (communities and governments) and sustain relationships through a full range of collaborative activities. Activities include organizing scientific conferences to communicate scientific evidence and increase capacity building, writing and disseminating reports, and holding regular meetings with stakeholders and local/national policymakers (Fig. 2) both to get their input but also to regularly report on study progress and findings.

Collaboration with stakeholders and policymakers also requires engagement in science that meets a felt need, in this case the health and wellbeing of the next generation. When communities and government officials feel that the research aligns with their priorities and needs, they are more likely to endorse and remain engaged in the process (McKay and Paikoff, 2007), and utilize research findings to inform policies and programming. This alignment can be best communicated through relationship building and opportunities for interaction over time (e.g. conferences). Building these long-term partnerships are especially critical because they have the greatest capacity for making a difference in the health of the population (Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium, 2011). Equally important is the implementation scientists’ ability to translate their research findings into accessible and actionable language for policymakers, communities, and implementers to inform policies and programs. It is with that intention in mind that the SMART Africa team collaborated with in-country partners to write and distribute policy briefs (see Fig. 2).

Finally, the process of engagement and collaboration needs to be guided by frameworks which allow for systematic approaches, as well as increases likelihood for successful implementation, sustainability and replication. These frameworks provide the road map for implementation scientists to adapt or create an EBP that is capable of being implemented and scaled within a LMICs. Frameworks, such as PRISM (described above) emphasize multi-level alignment and contextual influences that have challenged many attempts to meet the serious mental health needs of children in resource scarce country contexts.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Mwebembezi at Reach the Youth Uganda; Apollo Kivumbi, Phionah Namatovu, and Joshua Kiyingi at the International Center for Child Health and Development (ICHAD) who are key members of the research and implementation in Uganda. We would like to thank the 30 primary schools that have agreed to participate in the study. We are also grateful to the parents and teachers who have contributed to the adaptation of the MFG content and delivery to the Uganda context.

Funding

This study is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) under Award Number U19 MH110001 (MPIs: Fred Ssewamala, PhD; Mary McKay, PhD; Kimberly Hoagwood, PhD). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIMH or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112585.

References

- Akpan MU, Ojinnaka NC, Ekanem E, 2010. Behavioural problems among school-children in Nigeria. S. Afr. J. Psychiatry 16, 6 10.4102/sajpsychiatry.v16i2.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashenafi Y, Kebede D, Desta M, Alem A, 2001. Prevalence of mental and behavioral disorders in children in Ethiopia. East Afr. Med. J 78, 308–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Community collaborative youth-focused HIV/AIDS prevention in South Africa and Trinidad: preliminary findings. J. Pediatr. Psychol 31, 905–916. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baptiste D, Blachman D, Cappella E, Dew D, Dixon K, Bell CC, … McKay MM, 2007. Transferring a university-led HIV/AIDS prevention initiative to a community agency. Soc. Work Ment. Health 5, 269–293. 10.1300/j200v05n03_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bellis MA, Lowey H, Leckenby N, Hughes K, Harrison D, 2013. Adverse childhood experiences: retrospective study to determine their impact on adult health behaviours and health outcomes in a UK population. J. Public Health 36, 81–91. 10.1093/pubmed/fdt038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belfer ML, 2008. Child and adolescent mental disorders: the magnitude of the problem across the globe. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 49, 226–236. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsey MA, Sherr L, 2011. The definition of true orphan prevalence: trends, contexts and implications for policies and programmes. Vulner. Child Youth Stud 6, 185–200. 10.1080/17450128.2011.587552. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatti Y, Taylor A, Harris M, Wadge H, Escobar E, Prime M, Patel H, Carter AW, Parston G, Darzi AW, et al. , 2017. Global lessons in frugal innovation to improve health care delivery in the United States. Health Aff 36, 1912–1919. 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownstein JN, Bone LR, Dennison CR, Hill MN, Kim MT, Levine DM, 2005. Community health workers as interventionists in the prevention and control of heart disease and stroke. Am. J. Prev. Med 29, 128–133. 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.07.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JD, Loeber R, Birmaher B, 2004. Oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder: a review of the past 10 years, part II. Focus 41, 1275–1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacko A, Gopalan G, Franco L, Dean-Assael K, Jackson J, Marcus S, et al. , 2015. Multiple family group service model for children with disruptive behavior disorders: child outcomes at post-treatment. J. Emot. Behav. Disord 23, 67–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement, 2011. Principles of Community Engagement, second ed. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pdf/pce_report_508_final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Cortina MA, Sodha A, Fazel M, Ramchandani PG, 2012. Prevalence of child mental health problems in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med 166, 276–281. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curley J, Ssewamala FM, Nabunya P, Ilic V, Keun HC, 2016. Child development accounts (CDAs): an asset-building strategy to empower girls in Uganda. Int. Soc. Work 59, 18–31. 10.1177/0020872813508569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C, 2012. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med. Care 50, 217 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812.Curran. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein AC, Glasgow RE, 2008. A practical, robust implementation and sustainability model (PRISM) for integrating research findings into practice. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf 34, 228–243. 10.1016/S1553-7250(08)34030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalan G, Franco L, Dean-Assael K, McGuire-Schwartz M, Chacko A, McKay M, 2014a. Statewide implementation of the 4Rs and Ss for strengthening families. J. Evid. Based Soc. Work 11, 84–96. 10.1080/15433714.2013.842440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalan G, Chacko A, Franco L, Dean-Assael K, Rotko L, Marcus S, et al. , 2014b. Multiple family group service delivery model for youth with disruptive behaviors: child outcomes at 6 month follow-up. J. Child Fam. Stud 24, 2721–2733. 10.1007/s10826-014-0074-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschhorn LR, Ojikutu B, Rodriguez W, 2007. Research for change: using implementation research to strengthen HIV care and treatment scale-up in resource-limited settings. J. Infect. Dis 196, S516–S522. 10.1086/521120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB, 1998. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 19, 173–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, 1995. Conduct Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence Vol. 9 Sage Publications, New Haven. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly KA, Heckman TG, Stevenson LY, Williams PN, et al. , 2000. Transfer of research-based HIV prevention interventions to community service providers: fidelity and adaptation. AIDS Educ. Prev 12, 87–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieling C, Baker-Henningham H, Belfer M, Conti G, Ertem I, Omigbodun O, et al. , 2011. Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action. Lancet North Am. Ed 378, 1515–1525. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60827-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisia J, Nelima F, Otieno DO, Kiilu K, Emmanuel W, Sohani S, et al. , 2012. Factors associated with utilization of community health workers in improving access to malaria treatment among children in Kenya. Malar. J 11, 248 10.1186/1475-2875-11-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleintjes S, Lund C, Flisher AJ, 2010. A situational analysis of child and adolescent mental health services in Ghana, Uganda, South Africa and Zambia. Afr. J. Psychiatry 13, 132–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig MA, Lutalo T, Zhao F, Nalugoda F, Wabwire-Mangen F, Kiwanuka N, et al. , 2003. Domestic violence in rural Uganda: evidence from a community-based study. Bull. World Health Organ 81, 53–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landes SJ, Curran GM, 2019. An introduction to effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs. Psych. Res 280, 112513. 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laugharne R, Appiah-Poku J, Laugharne J, Shankar R, 2009. Attitudes toward psychiatry among final-year medical students in Kumasi, Ghana. Acad. Psychiatry 33, 71–75. 10.1176/appi.ap.33.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lendingham JE, 1999. Children and adolescents with oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder in the community: experiences at school and with peer In: Quay HE, Hogan AE (Eds.), Handbook of Disruptive Behavior Disorders Plenum Press, New York, pp. 353–370. [Google Scholar]

- Liang H, Flisher AJ, Chalton DO, 2002. Mental and physical health of out of school children in a South African township. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 11, 257–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Burke JD, Lahey BB, Winters A, Zera M, 2000a. Oppositional defiant and conduct disorder: a review of the past 10 years, part I. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 39, 1468–1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Green SM, Lahey BB, Frick PJ, McBurnett K, 2000b. Findings on disruptive behavior disorders from the first decade of the developmental trends study. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev 3, 37–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madison SM, McKay MM, Paikoff R, Bell CC, 2000. Basic research and community collaboration: necessary ingredients for the development of a family-based hiv prevention program. AIDS Educ. Prev 12, 281–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Alicea S, Elwyn L, McClain ZR, Parker G, Small LA, Mellins CA, 2014. The development and implementation of theory-driven programs capable of addressing poverty-impacted children’s health, mental health, and prevention needs: CHAMP and CHAMP+, evidence-informed, family-based interventions to address hiv risk and care. J. Clin. Child. Adolesc. Psychol 43, 428–441. 10.1080/15374416.2014.893519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Gopalan G, Franco L, Dean-Assael K, Chacko A, Jackson J, Fuss A, 2011. A collaboratively designed child mental health service model: multiple family groups for urban children with conduct difficulties. Res. Soc. Work Pract 21, 664–674. 10.1177/1049731511406740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay M, Paikoff R, 2007. Community Collaborative partnerships: the Foundation For HIV Prevention Research Efforts in the United States and Internationally. Haworth Press, West Hazleton. [Google Scholar]

- Mellins CA, Nestadt D, Bhana A, Petersen I, Abrams EJ, Alicea S, … McKay M, 2014. Adapting evidence-based interventions to meet the needs of adolescents growing up with HIV in South Africa: the VUKA case example. Global Soc. Welf 1, 97–110. 10.1007/s40609-014-0023-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health of Uganda, Health Systems 20/20, Makerere University School of Public Health, 2012. Uganda Health System; Assessment. 2011. Retrieved from http://health.go.ug/docs/hsa.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N, 2003. Community Based Participatory Research for Health. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco. [Google Scholar]

- Nabunya P, Ssewamala FM, 2014. The effects of parental loss on the psychosocial wellbeing of AIDS-orphaned children living in AIDS-impacted communities: does gender matter? Child Youth Serv. Rev 43, 131–137. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naker D, 2005. Violence Against children: the Voices of Uganda Children and Adults. Raising Voices and Save the Children in Uganda, Kampala. [Google Scholar]

- Nalugya J, 2004. Depression Amongst Secondary School Adolescents In Mukono District, Uganda. Makerere University, Kampala. [Google Scholar]

- Ovuga E, Boardman J, Wasserman D, 2005. The prevalence of depression in two districts of Uganda. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol 40, 439–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Population Reference Bureau, 2009. World population data sheet. http://www.prb.org/pdf09/09wpds_eng.pdf. Accessed 15 July 2015.

- Roberts M, Mogan C, Asare JB, 2014. An overview of Ghana’s mental health system: results from an assessment using the World Health Organization’s assessment instrument for mental health systems (WHO-AIMS). Int. J. Ment. Health Syst 8, 1–13. 10.1186/1752-4458-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schackman BR, 2010. Implementation science for the prevention and treatment of HIV/AIDS. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr 55, S27 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181f9c1da. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secrest LA, Lassiter SL, Armistead LP, Wyckoff SC, Johnson J, Williams WB, Kotchick BA, 2004. The parents matter! program: building a successful investigator-community partnership. J. Child Fam. Stud 13, 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ssewamala FM, Alicea S, Bannon WM, Ismayilova L, 2008. A novel economic intervention to reduce HIV risks among school-going AIDS orphans in rural Uganda. J. Adolesc. Health 42, 102–104. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ssewamala FM, Ismayilova L, 2009. Integrating children’s savings accounts in the care and support of orphaned adolescents in rural Uganda. Soc. Serv. Rev 83, 453–472. 10.1086/605941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ssewamala FM, Nabunya P, Ilic V, Mukasa MN, Damulira C, 2015. Relationship between family economic resources, psychosocial well-being, and educational preferences of AIDS-orphaned children in southern Uganda: baseline findings. Glob. Soc. Welf 2, 75–86. 10.1007/s40609-015-0027-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ssewamala FM, Neilands TB, Waldfogel J, Ismayilova L, 2012. The impact of a comprehensive microfinance intervention on depression levels of AIDS-orphaned children in Uganda. J. Adolesc. Health 50, 346–352. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ssewamala FM, Sensoy Bahar O, McKay MM, Hoagwood K, Huang KY, Pringle P, 2018. Strengthening mental health and research training in Sub-Saharan Africa (SMART Africa): Uganda study protocol. BMC Trials. 19 10.1186/s13063-018-2751-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorsdahl K, Stein DJ, Grimsrud A, Seedat S, Flisher A, Williams DR, Myer L, 2009. Traditional healers in the treatment of common mental disorders in South Africa. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis 197, 434–441. 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181a61dbc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF, 2015. State of the world’s children 2015 country statistical tables: Uganda statistics; http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/uganda_statistics.html. Accessed 15 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Washburn JJ, Teplin LA, Voss LS, Simon CD, Abram KM, McClelland GM, 2008. Psychiatric disorders among detained youths: a comparison of youths processed in juvenile court and adult criminal court. Psychiatr. Serv 59, 965–973. 10.1176/appi.ps.59.9.965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittkowski A, Gardner PL, Bunton P, Edge D, 2014. Culturally determined risk factors for postnatal depression in Sub-Saharan Africa: a mixed method systematic review. J. Affect. Disord 163, 115–124. 10.1016/j.jad.2013.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. 2008. Task shifting: global recommendations and guidelines https://www.who.int/workforcealliance/knowledge/resources/taskshifting_guidelines/en/.

- World Health Organization. 2009. Country profile of environmental burden of disease: Uganda http://www.who.int/quantifying_ehimpacts/national/countryprofile/uganda.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 2 July 2015.

- World Health Organization, 2005. World psychiatric association, international association for child, adolescent psychiatry, allied professions Atlas: Child and Adolescent Mental Health Resources, Global Concerns, Implications for the Future. World Health Organization, Geneva. [Google Scholar]